Making Meaning is where we share approaches to teaching English and history. Our goal is to help students think critically and creatively where close reading meets modern learning. Benjamin Gregg is a cellist and inventor and is Director of Studies at Walnut Hill School for the Arts. Jason Stumpf is Head of the Humanities Department at Walnut Hill and is the author of A Cloud of Witnesses, a book of poems. He tweets at @theJasonStumpf

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Thinking About Thinking

by Jason Stumpf

"Metacognition is, put simply, thinking about one’s thinking. More precisely, it refers to the processes used to plan, monitor, and assess one’s understanding and performance. Metacognition includes a critical awareness of a) one’s thinking and learning and b) oneself as a thinker and learner."

– Nancy Chick, Vanderbilt Center for Teaching

There is an old story, probably apocryphal, about a minister who describes his approach saying, “I divide my sermon into three parts. In the first part I tell ’em what I am going to tell ’em; in the second part—well, I tell ’em; in the third part I tell ’em what I’ve told ’em.” If we imagine that this minister is, instead, a teacher and his sermon is a lesson plan, what would we say about this approach?

The act of naming what one is learning is so important to building understanding. So important, in fact, that teachers can be afraid to leave this work to students. I see this tendency in my own work to identify what's being learned on my students' behalf with the insecure hope that my saying it will make it so. I've been trying to make more space for students' metacognition. Done well, metacognitive practices not only help students author their learning, they also offer real-time feedback to teachers. Here are a few I've been experimenting with.

Make a Commonplace Book

Collage excerpts from your notebook (in-class writings, drafts, quotations you've gathered from our reading) in order to demonstrate how you're thinking about a theme or topic we've been exploring.I have students do this every two weeks as an in-class activity.

Tracking Takeaways

How has this essay changed (or affirmed) your thinking about about a theme or topic we've been exploring?

What have you learned as writer from this example?

The Goal Grid

The Goal Grid was inspired by a page from Lynda Barry’s book What It Is. This is a tool for goal-setting and reflection.

0 notes

Text

The Dawn of (stitching together almost) Everything

by Benjamin Gregg

Meet The Dawn of Everything by Davids Graeber and Wengrow. Launching into it last month I didn’t realize how popular it would become - not everyday that a history book this huge and this general becomes such a hit!

The authors propose a revolutionary revision of the master narrative of civilization - the framework belief that they see as behind so much of our understanding of the past. This old master narrative, they posit, sees human societies as having evolved from simple to complex, from rural to urban, from mystical and superstitious to rational and logical. In this old framework, civilization has brought technology, wealth, population growth, urbanization, bureaucracy but it has also brought sophistication, complexity of social organization, democratic and liberal principles.

This linear and sequential view of human societal development is the foundation for almost all of our historical consciousness and, in their view, it is dangerous bunk. It is bunk because it is demonstrably false, and it is dangerous because it acts as a powerful lens whose distorting effect has skewed whole areas of our knowledge and made objective study of the past almost impossible.

Graeber and Wengrow propose that we shatter our historical model and then flatten the pieces. History for them is not one gradually accumulating complexity but many separate complex stories, each with their own genius and each resistant to comparison with others. They offer example after example of past societies whose size and complexity challenge the mainstream evolutionary model.

• The Thlaxcalans made the decision to side with Cortez against the Aztecs through a governance model that was decentralized and deliberative - more Athens even than Athens. Complex deliberative governance was not an outgrowth of industry.

• Agriculture was actually rejected by most of the early cultures who tried it in favor of hunting and gathering. Agriculture was not a revolution.

• Kings only ruled in Mesopotamia millennia after agriculture was established there. Monarchy was not an inevitable product of agriculture.

My question about this book is this - have Graeber and Wengrow made an original argument? Or have they collected the arguments of many others into a really rich compendium?

Marshall Sahlins is here - the author most famously of The Original Affluent Society. Sahlins made something of the same revisionist argument about hunters and gatherers and he made it in 1966.

Alfred Crosby is here - the author most famously of Ecological Imperialism. Crosby proposes that the hunting societies of North America did not live Rousseau-like lives, beautifully in tune with the land. They altered their environments and the landscape in profound and permanent ways. And he wrote this in 1986.

And of course, Jared Diamond is here - author of Guns, Germs, and Steel. Diamond’s famous work links production and the cultures that stem from production to environmental and resource factors. His argument implies huge variation across human societies and acknowledges the equal sophistication of human ingenuity everywhere. For Diamond, the resources available tell the story of a culture, not a chain of evolutionary advancement. He wrote this book in 1997.

I have huge admiration for this book, but I am torn as to its ultimate originality. Sahlins, Crosby, Diamond and many others have been outlining this new historical paradigm for decades. Perhaps Graeber and Wengrow’s genius here is that their book draws all of these revolutionary historians together so we can see them all in one book, albeit a very long one!

0 notes

Text

In Search of Deeper Learning: An Appreciation

by Jason Stumpf

Over the course of six years, Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine visited 30 US high schools "recommended as offering deeper learning, 'twenty-first century skills,' or particularly rigorous traditional learning." In their book, In Search of Deeper Learning, Mehta and Fine describe deep learning as characterized by mastery, identity, and creativity and position their analysis in the context of thinking in the field of education. They share findings from their observations and offer extended profiles of three of the schools they observed (which they refer to as Dewey High, No Excuses High, and IB High). The authors were surprised by how few examples of deeper learning they found. As they say in the introduction, "This was not the book we set out to write."

I read In Search of Deeper Learning expecting to find inspiring accounts and models of best practices. Instead, the book posed a more complex – and ultimately more engaging – way forward. Mehta and Fine offer a thoughtful and thorough exploration of the schools they profile and of the state of secondary education. I heard echoes of my own school in their descriptions of engaged students and also in the competing values within a school culture. For weeks after reading it, I talked about the book – and the puzzles the book posed – with anyone who would listen. Mehta and Fine set the stage for a crucial conversation about the future of schools and the nature of school transformation. Their work, rooted in a deep understanding of the history and philosophy of secondary education, is the most patient consideration of the goals and reality of secondary schools.

But my experience of the book was changed even more as COVID spread throughout the world. I read In Search of Deeper Learning during the early days of 2020. The US was enjoying its pre-COVID state of innocence and I was thinking longterm about what teaching and learning could look like. Shortly after finishing the book, my focus and the nature of my work changed dramatically. Throughout the pandemic – as our school went remote, then hyflex, then came back together – I kept thinking about the book. Where is deeper learning now? With each change to the schedule or classroom environment, I wondered: what is this doing to our hopes for deeper learning? With so much competing for our attention, the concept of "deep learning" sometimes seemed like a luxury that required resources we lacked. But over time, it began to feel like a necessity. Our learning communities suffered from a lack of it. As we see a mental health crisis among teens and come reckon with systemic racism in our institutions, the need for this combination feels all the more necessary. COVID exposed how much we need to center schools around mastery, identity, and creativity. Mehta and Fine offer essential framework for the necessary conversations ahead.

0 notes

Text

Models to Make and Break

by Benjamin Gregg

Visual historical models oversimplify. It’s what they do. This limits them, but it’s also why we like them - they help us manage, sort, and make meaning out of what is essentially an infinitely complicated past.

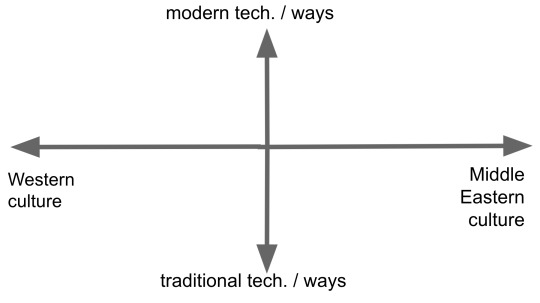

Here is a model I use in class to sort six different ways that people in the Middle East responded to 19th century industrialization and European colonial pressure.

In this activity students read a section of Cleveland and Bunton’s A History of the Modern Middle East describing the actions and approaches of a number of different 19th century leaders and reformers from Egypt and the Ottoman Empire. In class I hit them with this model and ask them to take the elements from the reading and, in groups, figure out where they might go in this model. There are some that are pretty simple for them - pretty quickly the models look something like this.

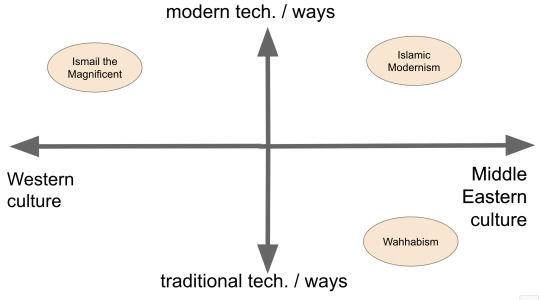

Ismail pushed industrialization in Egypt and imported along with it a lot of Western cultural stuff. The Wahhabi movement did the opposite; they rejected economic and technological change, hated all things culturally Western, and even saw mainstream Islam as corrupted by a millennium of ill conceived efforts at reform. Islamic Modernism is harder for students but it is kind of right there in the name; this movement believed that a more rigorous and complete dedication to Islamic traditions and forms would return the Islamic world to the vanguard of intellectual and economic innovation.

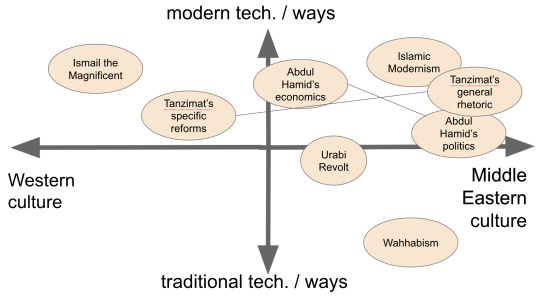

Then there are a few pieces of the reading that don’t easily fit this model (Sultan Abdul Hamid, the Urabi Revolt in Egypt, the Tanzimat reforms). Sometimes students break these into their component parts - putting the Sultan’s political stance in one quadrant and his economic reforms in another. This works to a certain degree, but the Urabi Revolt and the Tanzimat are harder to fit. This starts to look a lot less elegant...

So does this mean the model is problematic? I say yes, and no.

The model is problematic in that it suggests that these are the only dimensions of response and that everything should fit. We can squeeze things in if we twist ourselves in knots but in the end, if the visual is a mess, has it’s lost its value?

The model’s limits can actually be useful. After some time working on this exercise, I can encourage the students to find a better way to sort the movements. Do we need different labels? A third axis? An entirely different model? Essentially, this model acts to engage students in an orderly sorting of what they read. Then, as they get a clearer picture of how these responses are different, they bump up against the model’s limits. No problem, because now, with some encouragement, they can be invited to break or redo the model itself.

Using visualized models of historical content can be scaffolded up and down:

SIMPLEST - Show students a model that is already built and filled in with content. Here the model is a visual aid, not really an activity. It can help explain or reinforce a pattern, question, or lesson. “Here’s a way of looking at this content…” It could also invite critique of the model if students are ready for that.

MORE ENGAGEMENT - Give students a blank or partial model that they have to fill in or complete. Here students participate in creating the model but don’t have to invent it. “Here’s a way of sorting or shaping content - how can we fit the content in here?” The example above about the Middle East is sort of like this.

VARSITY - Ask students to invent their own way of visually modeling the content. Here the students need to search for the patterns or categories themselves, invent a useful way of representing these visually, and then test and revise their model. “Here’s some complicated content. How can we sort or shape this story to reveal something true about it or to understand it better?”

0 notes

Text

To Look Again, To See Anew

by Jason Stumpf

"The revision for me is the exciting part; it's the part that I can't wait for."

-Toni Morrison

Revision can seem cordoned off -- an activity separate from writing. The student writer composes a piece. The parameters of the assignment (or the due date) indicate if and when it is "finished." Then, the student revises only if directed and as directed by a teacher.

Revision's lofty but literal meaning is "to see again" or "to see anew." To revise, therefore, is to evolve your understanding of a text or topic. Professional writers often refer to revision as a place for ownership and powerful discovery. For example, in an appreciation of the YA writer Esther Forbes, George Saunders writes:

"Forbes had fully invested herself in her sentences. She had made them her own, agreed to live or die by them, taken total responsibility for them. How had she done this? I didn't know. But I do now: she'd revised them [....] With enough attention, a sentence could peel away from its fellows and be, not only from you, but you."

In the language of school, though, "revise" often has a more narrow sense of "to correct" and essays are static finished pieces rather than fluid attempts. As teachers, we may lament this emphasis but we also reinforce it. The rewards for being done are often more apparent than the incentives for ambitious experiment. As a conventional due date nears, there's an incentive for students to decrease possibilities and discoveries.

I can lament too but I'm short on solutions. It's not an easy fix. The change I'm after is part of larger change I'm after in which schools shape their structures around the wonder of each discipline, not the other way around. It's a change in the way we talk about and structure the work of writing. I'm most interested in exploring moves that bring revision into the process earlier and less formally -- that make it less about a chance for grade redemption (grades being a type of outcome, a product) and more about process.

Process Runs Throughout & Revision Starts Early

In writing-based teaching, students compose informal responses to grapple with the texts and topics they study. The writing process begins as students form their first ideas about a piece (sometimes before with pre-writing). The pieces students accumulate in their notes reflect their thoughts and the changes in their thoughts. This allows revision to become a normal part that happens throughout the process. Everything after the first impression is revision. Naming this -- and normalizing it -- keeps revision from becoming a separate sphere. When students draw from this work to produce a first typed draft, it is a revision. Calling it this reframes the work and -- I think -- makes the writing process less daunting.

Change the Medium

In Carley Moore’s contribution to the collection Writing-Based Teaching, she invites writers to identify claims, concepts, or questions in a draft and then "Write a six- to eight-line poem that demonstrates how these claims are related to one another." There is tremendous value in changing the medium in which we engage with ideas. I sometimes have students make informal presentations of their ideas. This often means a screencast in which they annotate a text as they talk through the ideas they're developing. They are allowed to refer to their writing but cannot read it verbatim. In doing so, they present thinking as speech rather than writing, they frame their text in a different -- and hopefully purposeful -- way, and, because it's a recording, the student can become an audience for their own thoughts. Doing this at various stages throughout the process -- not at the end -- means that presentation can be low-stakes and need not be a stiff regurgitation of a finished paper.

I’m curious to keep iterating and revising my approaches.

0 notes

Text

Starting with Symmetry

by Benjamin Gregg

Symmetry is a pretty concrete concept to see and confirmation of it tends to be right there in front of the viewer - an easy thing for students to identify. Of course, figuring out what symmetry is doing to the meaning of the work is the ultimate goal, but first we need to really get close to the specific nature of the symmetry in the image.

Here is an image I used in class this year that I’m interested in working with more in the future.

SOME QUESTIONS TO ASK: 1 - List the elements that create the symmetry. List the elements that break the symmetry. Compare and contrast these lists for categories and patterns - what are the things that are actually creating and breaking the symmetry? Here, for example, the symmetry is created by the arch and columns, the seat, the red fields of the background, and the crown, but also by the natural symmetry of a human form facing forward. The asymmetry includes the different arm postures, the cloak, and the feet but mainly by the sword and the shield. What does the strong symmetry of the architecture imply or reveal? With that strong symmetry established, what does the prominent asymmetry of the sword and the shield suggest?

2 - List elements that create the symmetry that are inherently symmetrical, like a face, a flower, or the horizon, and those that are not inherently symmetrical but that have been arranged symmetrically. The arch and columns are not natural elements per se, but arches are necessarily symmetrical because arches require that shape to be strong and stable. Does a consideration of what arches are, what they do, and where they appear, lend any meaning to the image? The human form, on the other hand, is inherently symmetrical but only in the posture of facing directly forward. Does this posture, which creates more symmetry in the image, lend any meaning to the image? What might it mean if we place that human form symmetrically within that arch form?

3 - List or describe what is at the center of the symmetry vs. those elements on the edges of the symmetry. Here the architecture and background create strong symmetry but they are on the edges. The king is both symmetrical himself and in the center of the symmetry of the whole. Specifically, his face, crown, and body are central. What is the effect of this placement?

4 - Identify if there is one overall symmetry and/or if there are areas of symmetry in the work. Here there is really only one area of symmetry, unless we determine the shield’s symmetrical shape is significant (though the 3 lions are not symmetrical).

5 - Ask about the difference between balance and symmetry. Are there elements that are not symmetrical but are balanced? Here, for example, the sword and shield are not symmetrical but there are ways in which they could be described as balanced. The cloak and arms likewise could be described as asymmetrical but balanced. What might be particular about the meaning of true symmetry vs. balance?

MANIPULATIONS HELP US TO SEE

Experimenting with manipulations of the image can help us see these patterns. Plus, it’s fun. Make these yourself or have students do this on the computer or, even better, with scissors!

What do we see if we observe the image in quadrants?

Or even more dramatic might be to see the quadrants in different combinations. You could give them these separately before you even give them the whole image, making it possible for them to play with combining them in different ways.

For example, it might be interesting to have them look at the diagonal quadrants separated like this:

This might help students see that the sword and the shield are asymmetrical both horizontally and vertically. What is the effect of this composition? How does this change the way we see these items? We might also determine the degree to which the asymmetry of the clothing and the feet matter to our understanding of the image.

Have more fun - what do we see if we create mirror images of the left half and right half of the image?

These two weird versions may help to underline the way the sword and the shield stand out as the main asymmetrical elements and also how they are asymmetrical. Plus they are kind of awesome.

IN THE END We want students to build an argument about meaning. Here, for example, we could ask about the nature and origin of authority in Medieval Europe. In images like this, a consideration of how the composition establishes and breaks symmetry can be a great concrete starting place, a weird and fun way to explore an image, and ultimately a door into some juicy ideas.

0 notes

Text

Teaching Writing: A Hybrid Approach Through Craft

by Jason Stumpf

Last summer's New York Times article, entitled “Why Kids Can’t Write,” describes the two predominant approaches to teaching grammar. The first is a rules-based approach that consists of worksheets and exercises. It proposes that clarity arises from the knowledge and practice of conventions. The second is approach is experiential and holds that students learn to write through an immersion in models, practice, and mistakes. This approach emphasizes expression and holds that students will take greater ownership of their writing if their primary experience of writing isn't about prohibitions. Any current or former high school student is likely to have experienced one (or both) of these approaches. But the way each conceives of writing is problematic and the division between them is false. Writing is not purely bound by rules. And clear writing cannot be freed from them.

Instead, writing is a craft. It can be both technical and artful. We acknowledge its conventions (the way best practices are handed down from prior practitioners) as well as its opportunities for invention (individual practitioners make the practice their own). Craft is learned through a combination of instruction and experience. A skilled craftsperson can cite rules but also opt for pragmatic, or even artful, deviations.

The Times article doesn’t talk about things this way because teachers rarely do. Unless, that is, they’re telling the story of the way they learned to write. The story of taking ownership over one’s writing is most often a two-part story of finding language’s power to express truth and also of abiding with one’s words long enough to make them clear. Learning a craft is a hybrid involving both rules and experience.

The questions that emerge are how we foster students’ curiosity about the customs of expression. And how do we foster their ownership and creativity? Below are starting points for what this might look like in the classroom.

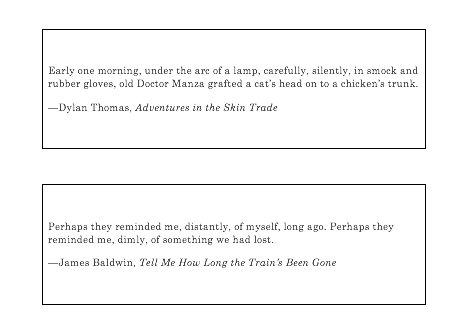

OBSERVING SENTENCES

5-10 Minutes | Classroom Routine

Learning a craft is about training one's attention to notice the intricacies and effects of small differences. The sentence — as the primary unit of composition — is where attention should be paid. As Verlyn Klinkenborg writes in Several Short Sentences About Writing, "The only link between you and your reader is the sentence you’re making. There’s no sign of your intention apart from the sentences themselves.” This exercise consists of asking students to observe sentences and short passages. It’s close reading divorced from context so students can make “non-content” observations about the composition of the piece. I regularly start class by taking a few minutes to have students observe a piece of writing, keeping in mind that an observation is a humble thing. After a few weeks of this, we move on to consider not only observations but also their possible effects. One of my colleagues, sometimes has students write their own sentences modeled on the example.

TWO EXAMPLES

—

READING ALOUD

Time varies | Classroom Routine

It can be difficult to get students to hunger for clarity when they don’t have a strong concept that there is an audience for their work. Having an evaluator (the teacher) is not the same as having an audience they wish to influence, connect with, or impress. Reading their work — even portions of it — aloud makes the audience real. This practice takes time and positive norms around how the work is presented (no apologies or disclaimers) and how it is received (my classes give appreciative snaps and sometimes take a moment to have listeners say back moments they appreciated).

—

RETURN TO RECENT WORK

10-15 Minutes | Classroom Routine

What does an artist do, mostly? She tweaks that which she’s already done. There are those moments when we sit before a blank page, but mostly we’re adjusting that which is already there. The writer revises, the painter touches up, the director edits, the musician overdubs.

— George Saunders

Editing is often easier when it’s separate from the invention of a text. For this practice, the teacher selects excerpts of student writing from recent assignments: maybe three or four that represent issues that are common to students in the class and that are developmentally appropriate to remedy. These are presented to students anonymously on slides (or on a handout) as moments that could benefit from further attention. Students take a moment to formulate suggestions and to share them.

—

EDITING BY EAR

Time Varies | Homework Assignment

“Grammar is a piano I play by ear”

—Joan Didion

It can be difficult to recognize grammar issues and awkward phrasing in your own writing. Listening to your own writing puts you in the position of the reader, the audience for your work, making you better able to identify trouble spots. Often grammatical errors and awkward writing interfere with fluent, clear writing.

OPTION A

Record yourself reading your essay aloud. Don’t rush. As you read, listen for any sentences that are awkward to read, for distracting repetitions, or for things that are not clear.Then, listen to the recording while you follow along with the text. Mark anything that stands out as rough or troublesome. Try to resolve these moments. Ask if you need help.

OPTION B

Ask a friend who is not in this class to read your essay aloud to you. Follow along as they read, marking any places they stumble—anything that sounds awkward. Thank them.Before you dismiss these stumbles as simple accidents (which they could be) look over the places you marked to see if you identify any problem areas and any possible solutions.

0 notes

Text

Cultivate a Learning Practice: Risk Failure

by Jason Stumpf | @theJasonStumpf

Think of a time you learned to do something.

It could be anything. Maybe it took an hour or maybe months or years.

Now think: What does this story say about the ways people learn?

This is the start of conversation I regularly have with students. One student might tell the story of a frustrated afternoon spent sitting on the steps of their house, while their father patiently demonstrated the correct way to tie shoelaces. Another might tell their story of learning Spanish well enough to finally speak to their next-door neighbor. For some, the teacher is a kindly adult in a classroom who really saw them. For others, the teacher is the internet or maybe it's themselves.

Such stories of learning are fascinating and so are what they say about the ways we learn. Our stories of learning teach that learning takes practice, that there are setback along the way and that those are instructive as well. Our stories teach that learning benefits from curiosity, a real passion for the subject. They show that learning means taking risks — even risking failure. I always end this conversation heartened and inspired by what the students discover and share.

But, at the same time, this conversation often makes me feel like a fraud. As a teacher, I urge students to take risks and find their “edge.” I talk about the value of risk but I rarely put myself in a situation where failure is a possibility. Being an adult often means having the luxury to set unmonitored goals and to change them when things aren’t going as we’d hoped.

*

Last year, I set a goal of running the Lehigh Valley Marathon in September with a time good enough to qualify for a spot in the Boston Marathon. I increased my mileage throughout the spring, building to 195 miles in August: tempo runs and long runs, track workouts and hills. Everything was going according to my plan. But I never made it to the starting line. Weeks before the race, I started having muscle spams during runs. With a week left until the race, I could barely walk.

Failing caused me to analyze what I did wrong. It led me to seek help. I identified that I was working too hard and at the wrong job. I should have put on fewer miles and put in more time in the gym. Failing led me to be a stronger, smarter runner.

I still haven’t reached my goal of qualifying for the Boston Marathon but I still run to reach the edge of my capabilities. Earlier this month, I ran the TARC Fall Classic 50K (31 miles) because I wasn’t sure that I could do it. I had never run more than a marathon. I was confident, though, that I would learn no matter the outcome.

*

The longer I teach, the more important I believe it is for teachers to cultivate a learning practice for themselves — both in the classroom and beyond it. Whatever form it takes, it’s important that teachers actively engage in the process of extending their talents so we are better able to connect with our students experiences. Being a learner makes you a more empathetic and engaged teacher. Risk is just one aspect of this practice. It can be easy to find but difficult to undertake.

0 notes

Text

Recent & Recommended

by Jason Stumpf | @theJasonStumpf

This fall, I return to the blog with some recent reading and listening that has stayed on my mind in recent weeks.

"James Baldwin’s Lesson for Teachers in a Time of Turmoil” by Clint Smith in The New Yorker

As stirring as Baldwin’s 1963 call for teachers to "make a more honest reckoning with history" is Clint Smith’s placement of Baldwin’s ideas in the context of our times. Both Baldwin and Smith argue that social and historical context is central to students’ experience of their lives and is, therefore, central to the ways they experience education. Yet they are rarely acknowledged by adults in schools. Like Smith, I’m left ruminating on Baldwin’s idea that, “The paradox of education is precisely this—that as one begins to become conscious one begins to examine the society in which he is being educated.”

Loving Learning: How Progressive Education Can Save America's Schools by Tom Little & Katherine Ellison

I don’t remember how I stumbled upon this book but I’m glad I did. Loving Learning is both a history of progressive education and a memoir of the late Tom Little’s experience as Head of the Park Day School in Oakland, California. Little and Ellison's presentation of history is highly readable and their evident passion for the principles of progression education is inspiring.

Modern Learners Podcast by Will Richardson and Bruce Dixon

Will Richardson’s work is thought-provoking and, at times, downright provocative. Since his book Why School?, I’ve followed his work in his blog posts and talks. In Modern Learners, Richardson and Bruce Dixon don’t only present their own thinking but they also interview others who are reshaping education for the 21st century.

Several Short Sentences About Writing by Verlyn Klinkenborg

In his Prologue, Klinkenborg writes, “Part of the struggle of learning to write is learning to ignore what isn’t useful to you and pay attention to what is. If that means arguing with me as you read this book, so be it.” This peculiar book of “first steps” tests conventional wisdom about writing. There’s plenty to agree with here and to resist. The book’s motive, however, is clear: to get its readers to take ownership of their writing, to discard the confines of received wisdom in order to discover what works for them. I owe thanks to my colleague Kate Westhaver for introducing this book to me.

0 notes

Text

Three Keys: Content, Skills & Competencies

by Jason Stumpf | @theJasonStumpf

Asked what they’re teaching, an educator might say “American history,” or “Confucianism,“ or "The Great Gatsby.” These content-centered answers (nouns) satisfy the question in most situations.

Or they might answer that they are teaching students to make objective observations or to draw inferences about character. While these answers may be less relatable to non-educators, they reflect an essential recognition that education trains students students to do the real work of the discipline (note the way each item in this list begins with a verb), not just to understand its findings.

But what if a teacher responds that they are teaching students to disagree with one another with purpose and respect, to have discussions across differences of identity, or to recognize their own biases and assumptions? Verbs again but these are different: not just acts of intellect but of empathy and reflection. This teacher is focused on some of the key competencies that make process and growth possible. In such work, we realize the promise of schools — why teaching students in groups is not only more efficient but more dynamic.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about Key Competencies as a lens on curriculum. Related to “21st Century Skills,” these are what allows learning to take place.

Competencies in Action 1. Students collaborating to create a character sketch for Daisy Buchanan are first being asked to listen to one another, to try on different roles (who will record? who will moderate?), to reconcile differences of vocabulary.

2. Asked to write an essay, a student not only follows directions but also persists even while uncertain that her approach will pay off or that her ideas are valid. She may restart portions of the process after recognizing more promising discoveries.

Competencies are often taught through modeling. It’s heartening that — even if they’re not explicitly discussed — they haven’t disappeared. It’s also disheartening how much classroom time can be spent without explicit recognition of these essential acts of challenge, growth, and engagement. Supporting students starts with asking what skills, content, and competencies a unit or project or course engages.

THE THREE KEYS (Beyond the three Rs) KEY CONTENT is the object of our shared attention. (Noun)

- Texts - Historical Periods - Mathematical or scientific principles (e.g. division or mitosis) or objects for study (e.g. triangles or fetal pigs)

Revealing Question: What is the object at the center of our shared attention?

KEY SKILLS culminate in demonstrations of mastery. In the academic classroom these are assignments and projects. (Verbs)

- Observing Objectively - Drawing Inferences - Recognizing bias in an article

Revealing Question: How do we engage with object?

KEY COMPETENCIES foster a group dynamic that has a place for every voice and is likely to be useful to all. They challenge individuals to grapple with assumptions and to seek nuance. They reflect core values. (Verbs)

- Listening to understand - Agreeing/Disagreeing with purpose and respect - Asking questions - Having discussions across identity differences - Recognizing your own biases and assumptions - Reconciling differences in vocabulary or differences of emphasis - Trying on different roles within a group (moderator, recorder, listener)

Revealing Question: How do we engage with each other, ourselves, and our work in to move our learning forward?

0 notes

Text

Visualizing Texts: Counting

by Jason Stumpf | @thejasonstumpf

ON VISUAL DESCRIPTION

Some part of understanding a thing is having the ability to describe it. To understand that a pie is sour or sweet is, in some small but important way, to understand what that pie is.

Descriptions of a text most often take the form of sentences and paragraphs that tell what it is and what it means (interpretation, different from description, tells how something means). But sentences are not the only way to describe something. Visually rendering texts can (1) help us focus on observing without leaping to interpretive conclusions, (2) lead us to notice meaningful compositional features, (3) give us a way to describe these elements.

Visual rendering has the added advantage that it allows students to momentarily set aside the work of crafting sentences in order to observe. Conversely, there’s often rich challenge in translating observations from the visual rendering into language at a later stage.

COUNTING

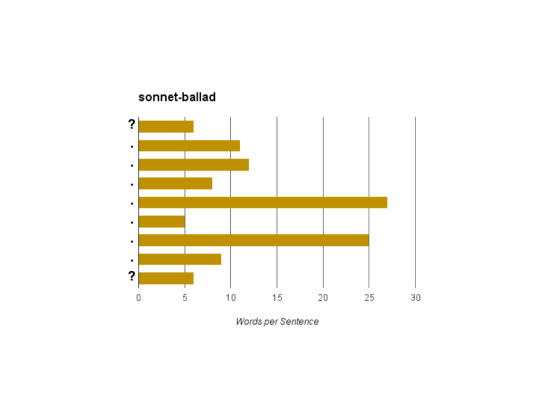

In this post, I’d like to focus on one way to observe and render a text: counting. To observe a photograph of a family, for example, we might count how many people appear. Likewise, to observe sentences we might count how many words long each sentence is. It’s a crude measurement but it can be revealing. Doing this with Gwendolyn Brooks’ poem “sonnet-ballad,” for example, raises the question of what we make of the two longest sentences — each twice as long as the other seven. We might ask what kind of content — or what lyric impulse — coincides with this extension of syntax. And also, we could wonder what is going on in those shorter sentences surrounding them. This, it turns out, is a promising entry point into thinking about the poem.

Counting the number of words in a sentence starts out simply but it doesn’t always stay that way. (Poetry can be a tricky business). Take, for example, the opening of Jack Gilbert’s poem “A Brief for the Defense”:

Sorrow everywhere. Slaughter everywhere. If babies are not starving someplace, they are starving somewhere else. With flies in their nostrils. But we enjoy our lives because that’s what God wants. Otherwise the mornings before summer dawn would not be made so fine.

If the job is to count words per sentence, what do we do with these five fragments, which, together, form one grammatically complete unit? Do we count them as one sentence or five? While my simple answer is to count final punctuation and graph five syntactic units, by asking this question, something more important has happened: the simple task of counting words has revealed something complex about the poem. Even before we dig into the content of these opening lines, we are noticing their construction — the ways these five fragments relate, how they don’t fit within the bounds of normative syntax. Why are they fragments and not one, thirty word sentence? As a single unit, how does it compare with other 30+ word sentences in the piece? How do the parts compare with other short sentences in the poem?

Here, the task of graphing proved too simple for the oddity of the poem. I am here to tell you, though, that the the activity didn’t fail. Instead, it revealed features of the text that are not easily explained and so are worthy of further attention.

In addition to what you can learn from the inadequacy of a protocol, here are some other things to look out for in order to identify meaningful composition:

What’s the relationship between form and content? In other does the text use certain types of sentences to convey a particular subject, imagery, or tone?

Patterns, outliers, and shifts. Do you notice similarity (e.g. sentences of similar length), development (e.g. sentences gradually increasing or decreasing in length), or outliers (abrupt shifts)? Look to consider whether the content is also changing in similar ways.

Note: This post is indebted to Adam J. Calhoun’s study of punctuation in novels which is not only visually beautiful but also suggests more ways of rendering texts in order to analyze them.

0 notes

Text

How flexible is their learning?

by Benjamin Gregg

A TEACHER GETS SCHOOLED My son came home one day talking about a lesson from his 5th grade classroom. The topic was fashion. Always a bit of a skeptic, I asked him the most basic of questions about his learning, “What is fashion?” To my surprise, he responded with a pretty good definition. “Fashion,” he replied, “Is when you wear things because of how they look - you think they look good - not because you need to wear them.” Wow! I was proud - of him because it was a pretty good thought he had expressed and he had defined it clearly - and I was proud of myself because here was evidence that I was raising a kid who stood a chance of operating on his own standard rather than falling victim to peer pressure - a kid who could self-actualize - a kid who could chart his own course in this complex world. What a dad! Then I pushed my luck. “So those socks that you always wear are an example of fashion, right?” “Which socks do you mean?” “The socks you always wear with the thick stripes up the back - your wearing those are an example of fashion, right?” He looked at me sadly because clearly I was an idiot. “No dad, those aren’t fashion, those are cool.”

FORMULAIC OR FLEXIBLE? A thoughtful teacher will recognize this problem right away. Here is an example of a lesson that hasn’t transcended its specific context. Jonathan’s critical eye to the difference between fashion and function did not extend to his own experience - to things too close to himself or perhaps too distant from the specific examples that had been part of his lesson. How do we teach for flexible learning? How do we test how flexible learning is? How do we teach students to apply our lessons to things far from the classroom or very close to themselves? I think we should always be thinking about this problem. Always, always, always. If your lesson doesn’t have application outside of the specific context of your classroom and if it doesn’t help students better understand themselves and their world, why are you doing it? Kids don’t need more work, they need more tools. I also think we should assess students by giving them problems they’ve never seen before. Don’t reward formulaic or highly context specific demonstrations of knowledge. Don’t reward knowledge, reward the application or use of knowledge to approach or manage do some novel task. Without a specific plan to make learning flexibie and applicable, it can feel flat and rote. I still have faith that my son will be self-actualizing, but I also recognize that we still have a lot of work to do.

0 notes

Text

I Heart Process Talk

by Jason Stumpf | @thejasonstumpf

My sons have started watching Barbecue University in place of Saturday morning cartoons and I couldn’t be happier. I eat a mostly vegan diet so you won’t find me roasting a whole hog on a spit (episode 108). Even so, I enjoy knowing that there is something called "live fire cooking.” In fact, there are five types of it (episode 213). What I love about Barbecue University – along with some other cooking shows and how-to shows – is the way it models process talk. I am taken in by seeing a process described and demystified. I love it when practitioners of a craft share the wisdom of their experience. And best of all is the moment when someone makes a mistake or talks about failure. If you haven’t seen it, take a moment to watch Julia Child talk about failure in the kitchen.

Without process talk, craft is mysterious, mistakes are catastrophic, and mastery seems unattainable. I include process talk in my classes in the form of artists and authors writing about their work. More than once — and this is embarrassing — I have been moved to tears while reading George Saunders’ advice to young writers about revising their sentences. I find Ron Carlson Writes a Story to be as riveting as a mystery. A page-turner is the book of interviews 50 Contemporary Poets: The Creative Process. I love when each writer is asked how his or her poem changed from the first draft to the last.

Reading this talk of process doesn’t take the place of close reading but it reinforces the ideas that art-making is a process that includes conventions and innovations and that choices make meaning.

Reflection is another kind of process talk. Have students describe their goals, discoveries, and frustrations with their writing. Later, ask them to reflect on feedback they’ve received. We can model this ourselves. As teachers, we introduce students to processes of reading, writing, and analysis. We regularly model the wisdom of our experience but how often do we model our own struggles and mistakes?

0 notes

Text

Labels are not Meaning

By Benjamin Gregg

Sometimes very young kids teach us important things about our assumptions. Their perspectives can be wise, not in the sense that they are learned, but in the sense that they have much less to unlearn and so often don’t miss meanings to which their elders have grown blind.

My wife was screening some kindergarten kids and her protocol asked her to present the following question to her students:

Which of these numbers is bigger?

2 7

Presented with this question, one of her students looked at her and said, with some scorn for how silly the question was, “They are same size of course.”

A lifetime of using numbers as stand-ins for quantities makes us blind to the alternative meaning of “bigger” here. The kid is correct in the sense that these numbers are literally the same size.

So one challenge in teaching is to alert students to the ways that our quick, habitual use of words, which is generally so necessary to functioning in our daily lives, can mask or obscure what is really in front of us. In past posts I’ve talked about the blurry words that obscure good observations in my class, words like “hold,” “stand,” or “look.” These words need to be unpacked.

In a recent assignment I ran into another set of these assumptions in the form of what I think of as essentially empty labels. In writing about a figure from Mesopotamia, a number of students set up their claim as something like “This figure is a god.” Or “This figure is a king.” I believe that, in setting these labels up as claims they were doing something similar to what we do when we see 7 as “bigger” than 2. They were assuming a host of meanings behind the words “god” or “king” but they weren’t unpacking them.

A thought experiment - kind of modernist, but here goes: here are four chairs:

If these all fit under the word “chair,” what are the values and limits of that label “chair?” Can we usefully say which of these is more “chair?”

In the same sense, can we really find value in labeling without a much richer unpacking of those labels? To say “god” or “king” or “chair” or “bigger” isn’t bad, it’s just insufficient. It also reveals the assumptions that we’re carrying around that mask real seeing and real analysis.

In his 1903 Programme architect Henry Van De Velde articulated this very challenge as at the heart of the modern movement and the modern perspective, saying:

It is not easy nowadays to find the exact meaning and the exact form for the simplest things. It will take us a long time to recognize the exact form of a table, a chair, a house. Religious, arbitrary, sentimental flights of fancy are parasitic plants.

(quoted in Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-century Architecture by Ulrich Conrads, 1970, MIT Press)

Getting past these powerful labels and the assumptions behind them is, for me, a primary role of my teaching. I don’t want to convince kids that 2 is, in fact, larger than 7, but I do want them to recognize the complexity of language and to be able to explore it and control how they use it.

0 notes

Text

How do we promote intellectual risk-taking?

by Jason Stumpf | @thejasonstumpf

“I love a good mistake!”

—my son’s fourth grade teacher

The humanities can feel loaded with risk. When practiced at their highest level the humanities, like the arts, involve an open-ended process that can yield unpredicted products. Historians don’t simply memorize dates; literary thinkers don’t just retell the plots they read. To interpret is to formulate your own ideas in your own voice. This feels risky. And sometimes, the results fall short.

David Gold, writing in the Modern Language Association's Profession, describes how students in college freshmen writing courses are "are commonly asked to write original, research-based arguments that synthesize and respond to multiple points of view, incorporate a variety of textual evidence, and seek to persuade a specific audience in a specific rhetorical context, in addition to following the conventions of edited English.” Gold argues that laments about declines in the quality of students’ writing are unfounded and misguided. There aren’t many more mistakes and we are asking students to do so much more than we did generations ago. As proof, he points to examples of student writing from the first half of the twentieth century when freshmen writing courses emphasized "error-free prose," “form and correctness", and writing “simple narratives or descriptive sketches.” In short, his argument is that (1) while students are writing differently, the quality of their writing is not worse than it was a century ago, (2) freshmen composition courses do not (and should not) make students into the rigid, generic writers and (3) that educators should recognize the versatility and complexity we’re asking of students.

This change in standards is a positive sign that schools and colleges are inviting students into the real work of the discipline and promoting intellectual independence. With this change in standards, however, the level of intellectual risk has gone up.

This, in turn, raises the question of whether the ways we teach writing have changed in the last century. If we’re asking students to engage with a complex intellectual project, then how do invite them to explore? How do we honor and encourage intellectual risk-taking? For some students, a good grade may be a goal but it’s not necessarily an incentive to exploration, experimentation, and risk-taking.

These questions could potentially open conversations about classroom norms and school culture; they could also lead us to consider what modes of writing are most relevant for students in high school and in the first years of college. For now, though, I’d like to take this into the classroom to share two strategies for structuring assignments that give students some opportunity to explore ideas without penalty.

Fail Better

In my course for high school seniors, we work with a different short text for each of the first three weeks. Each week, students write a short sketch -- I sometimes refer to it as a “proposal” -- for an essay on the that week’s text. The goal is zoom in and say a lot about a little. They receive feedback on each of these writings but no grade. In the fourth week, they are allowed to choose one of these projects to develop into a longer exploration of the text. Noah Rachlin at Andover’s Tang Institute describes a similar structure for having students try out ideas before developing one more fully (plus several other good strategies for promoting a growth mindset in the classroom). Shoot the Moon

Another option is to give students a chance to “shoot them moon” on one essay during a semester by trying a radically different approach -- an ambitious idea, even one that may not pan out. This doesn’t mean they drop the lowest grade but rather that they choose one project in which to boldly prioritize originality over adherence to assignment guidelines. Students must commit to this approach in process (before the assignment is due) and must write a coversheet that describes their goals, process, what worked and what didn’t.��

The more that we challenge student work to mirror that of professionals, the more we should allow students’ process to reflect the openness of professional process.

0 notes

Text

Assumptions and Speculations - Call Them Out

by Benjamin Gregg

A main goal of my World History course is to teach students to appreciate the power and depth of human systems of belief. How do these systems evolve? What influences their development? How do they shape perception and action? It helps that we study cultures very far removed in time and in schematic belief from our own because, in the end, my goal is to help students get some modicum of perspective on their own beliefs and this is, to my mind, one of the most difficult things of all for anyone to do. Studying the very ancient cultures that we study gives them some chance of having critical distance on these cultures and thereby learning what it feels like to exercise critical distance in the first place.

I find that two of the main conceptual challenges to our work have very concrete symptoms - “obviously” signaling an unfounded assumption and “maybe” signaling an unexplored speculation.

“OBVIOUSLY” Lots of people have talked about this word and its problems as it is often employed in discussions and arguments, so I just want to add my two cents as a teacher of 9th graders. Kids love this word. I don’t blame them for loving this word, but it is almost always a cover for an assumption that is masking exactly the issue that I want to unmask.

• “Obviously agricultural civilizations had much more knowledge...” • “The ancient people’s obviously didn’t know about democracy...” • “Obviously they didn’t understand disease yet, so...”

These ahistorical statements feel certain but are perfectly blinding the speaker to the interesting questions about what the ancients knew and believed.

• Because you have agriculture that produces more surplus, does that mean you have more knowledge? • Because democracy is common in contemporary societies does that mean its absence in the ancient world was due to a lack of knowledge? • Did the ancient people’s not know about disease? Or did they know something different about disease than we know?

We have found this word so consistently problematic that some of us have banned it, or have taken to making it a classroom buzz word. It’s true that arguments using “obviously” can always be unpacked to avoid the word and the assumptions it makes and that this unpacking is almost always a very healthy thing to do.

Kids feel like my dislike of “obviously” is akin to many people’s dislike of their repeated us of “like,” but I don’t find “like” nearly as problematic from a conceptual point of view. “Like” may suggest a habitual passivity or indirect form of argument, but “obviously” actively hides important truths.

“MAYBE” Many assignments we give ask students to explore meaning based on objective evidence. This often leads students down paths of meaning that they feel may not be supportable, and therefor, in an effort to hedge their bets, they put “maybe” in front of their statements of inference or interpretation. There’s nothing really wrong with a speculation per se, but wherever there’s a “maybe” I insist that there be a “maybe not.”

• “Maybe the Venus of Willendorf has been overeating” • “Maybe Hammurabi was just pretending to be a shepherd of Marduk.” • “Maybe Caesar knew of the plot against his life.”

Assuming a statement isn’t clearly false against the evidence, speculations can be useful, but only if you follow the alternative paths that are inherent to the business of speculations. If a student gives me a “maybe,” I’m likely to then ask them for at least one “or maybe...”

Students find my persnicketiness about “obviously” and “maybe” to be at times amusing, at times aggravating, but these are great examples of very concrete words and structures that reveal underlying patterns of thinking.

0 notes

Text

Be Yourself ... for Others

by Jason Stumpf | @thejasonstumpf Our blog posts often center on a lesson plan or a principle of pedagogy. While I firmly believe that these principles constitute good teaching, I know that their practice alone does not create a transformational teacher. That requires individuals who dedicate themselves to a discipline and to their students with energy and creativity. These characteristics are not easily defined and, when encountered, are not easily forgotten.

A couple years ago, during a professional development session, we were invited to whisper to the person next to us the the name of a teacher who changed the way we saw the world. I whispered “John Wolfe.”

John was not my teacher in an official, classroom sense; he was my camp counselor. But if not for him I would probably not have gravitated toward books the way I did. John made books cool. He made curiosity cool. While my young-teen self was concerned with categories (school or fun? rock or pop?) he was interested in everything that interested him: books for pleasure and books for school; philosophy and Stephen King; rock and punk and soul. Everything for John was fair game. What mattered were the ideas a book — or song or film or joke — could lead you to consider.

At fourteen, while I was slogging through my first summer of high school summer reading, he handed me A Prayer for Owen Meany. At 640 pages, it dwarfed any book I had read before. Aspiring to be like John, I read it and I loved it.

John has everything to do with why I am a teacher and, apart from teaching, he has plenty to do with who I consider myself to be. While other cabins lip synched the hits of the day, our cabin performed “Special Feel," the promotional single cassette that came free with his mother's Oldsmobile. He introduced me to the music of Black Flag, Van Morrison, and Steve Earle. He talked to me about books and about writing. He was a writer and, with his example, let me know that writing was something to pursue. He named the mouse who lived in our cabin and made up an elaborate inner life for him. He made moments into opportunities.

John died this past February. I miss him and I will miss knowing that he is a force for good in the world. I’m writing this to pay tribute to him and to an idea he embodied: be yourself for others. The best of yourself is all that is required to transform a moment, a day, and maybe a life. And that’s all. And that’s a lot.

The ability to be yourself for others has a lot to do with what makes a great teacher.

John Wolfe was a teacher and not just in the unofficial sense that I describe. He graduated from Loyola of Chicago and taught English and Creative Writing at the Punahou School for fifteen years. He later attended the University of New Orleans Master's Program in American Literature. He will be missed by his family, friends, and former students.

#teaching#engchat#oldsmobile#black flag#steve earle#van morrison#stephen king#pop music#punk rock#generosity#john irving

3 notes

·

View notes