home to all my writing that didn't find a different home. @urzashottub on twitter

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

You Can’t Go Home Again: An Analysis of Resident Evil VII

I'm comin' home, I've done my time Now I've got to know what is and isn't mine If you received my letter telling you I'd soon be free Then you'll know just what to do If you still want me

Introduction

Resident Evil VII is deceptive. Resident Evil, as a series, is deceptive. Numerous spinoffs and unnumbered entries turned the franchise into a tangled mess of intersecting characters, monsters, and conspiracies.

From the original trek through the Spencer mansion to the bombastic high-stakes setpiece-fest that is RE6, Resident Evil, after three console generations, had descended into itself, becoming bloated and seemingly incorrigible, impossible to nail down and define.

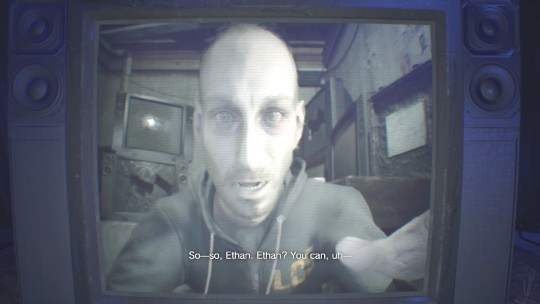

REVII was positioned as a return to form. Like the original Resident Evil, it is a straightforward story set in a spooky house, starring an inexperienced protagonist, Ethan, there with a simple but sympathetic and relatable mission: Rescue his girlfriend and get out. But REVII can’t help but dip into massive conspiracy as it navigates through what should be a relatively easy-to-digest story.

As Ethan searches for the missing Mia, who was away on a, get this, babysitting job, he encounters the deranged and inhuman Baker family, who have been granted a twisted immortality. There’s a pervasive black goo simply referred to as the Mold that seems to be infecting the family and their estate, spawning undead creatures and giving the Bakers supernatural powers. It’s not long before Ethan himself is infected, too.

The game then becomes a series of fetch-quests and races to various Macguffins as Ethan hurries to assemble a cure for himself, Mia, and their newfound ally, the Bakers’ daughter Zoe.

Resident Evil VII is a game running from its own past. As a linear narrative, it works fine, but it works better as a mood piece, a love letter to American horror films. It is meant to emulate a series of tropes and conventions. It's the product of two cultures—East and West— colliding head-on, and as a result it feels disjointed, dissonant, and yet wholly unique, fascinating, and, ultimately, compelling.

Resident Evil VII is an allegory for itself. It is a battle for the series’ soul.

Aesthetics

Let’s get one thing out of the way first: Resident Evil 7 is not concerned with realism. It’s about simulating a horror movie; recreating their grit, visuals, and mood. In this way, it is a simulation of a simulation, and it leans heavily on the history and conventions of the American horror film without ever fully understanding them. You see this in direct, 1-for-1 tributes, such as the chainsaw fight with Jack that evokes Evil Dead 2, or the Saw-like machinations of Lucas Baker’s deathtraps, or the body found in the basement corner in the Derelict House Footage tape, positioned just like the victim in Blair Witch Project. And practically the entire front-half of Resident Evil 7 is pulled straight from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

This is par for the course for the Resident Evil series. The first game was a pretty standard take on haunted mansion horror, with some limited ventures into ‘80s action films, casting STARS as the badass special forces team in way over their heads a la Predator or even Aliens.

Resident Evil has always been about taking American horror and action tropes and sort of sifting them through Japanese culture. It is a imitation of American conventions, and it works precisely because it is so imperfect. Its dissonance happens to work perfectly for the mood of the genre. There’s something unsettling about how the details are just off; Louisiana looks like a still frame from an episode of True Detective, but it’s still evocative of how Americans perceive the swampland. Little mistakes regarding the area’s history and culture—the strange references to football, the inaccurate Civil War uniform—make things uncomfortable and strange. It’s like taking an English sentence, running it through Google translate into Japanese, and then translating it back into English again. Some general meanings are there and you may even be able to gleam some sense out of it, but it has lost all context and syntax and turned into something that isn’t quite English and isn’t quite Japanese—something that occupies the space between, something that has become a totally unique method of communication, with its own new signifiers and meaning. That’s Resident Evil. And that may explain a bit of the franchise’s ongoing identity crisis, too.

On a more surface-level reading, the aesthetics of REVII are vastly different from those of its predecessors, an approach to horror that’s a bit brighter but no less terrifying than previous entries. Remember, VII tells us, sunlight casts deeper shadows than darkness. This approach to horror is largely possible due to the wonderful lighting and particle effects at Capcom’s disposal, and though their tech struggles with faces, the uncanny valley works in their favor for this particular title, elevating that otherworldly feeling of imperfect simulation.

The Baker mansion and its surrounding area are dirty, grimy, grotesque. It’s southern gothic. The word “squalor” comes to mind. They choose to live in filth. Is there something ableist and maybe even contempful towards poverty about this dehumanizing of the Bakers? Maybe, but any sort of prejudice that the designers might be preying on here comes from a degree of separation, in that their only knowledge of that context, as mentioned before, is through American horror films, through simulacra. It is seperated by multiple layers, and so I find it hard to condemn their visions of the impoverished American South as anything but pulpy horror. Whatever the case, the true antagonists of the story betray any idea of prejudice against the lower class.

Perspective

Resident Evil 7’s protagonist is a camera. The series shifts to a first-person perspective for the first time, placing the player behind the eyes and within the mind of the game’s lead, Ethan. Despite this, the game has no qualms separating the avatar from the controller; there’s a sense that Ethan is his own character, with his own motivations not necessarily in line with the player’s.

I’ve heard the argument that what Ethan sees within the first half hour of the game would be enough to make anyone turn back. Why does he choose to go in alone? Why doesn’t he get help, or at least arm himself before he starts literally wading through corpses? No justifiable motivation could explain that.

Ethan is ostensibly motivated to look for his lost love, Mia. We’ll talk more about Mia later, but first I want to challenge the idea that this surface motivation is all that is propelling Ethan forward. Of course, you and I, and the developers, know that Ethan’s true motivation has nothing to do with Mia, and in fact nothing to do with Ethan himself, as he has no autonomy in the story. No, the motivating action propelling Resident Evil VII forward lies in the hands of the player. In a horror movie, the sort of films REVII is explicitly invoking, we can feel smarter than the protagonists. We know not to take a shower, we know not to look behind the curtain. In a horror game, we must specifically put ourselves in dangerous situations, and we do it because it’s fun. Without doing that, we can’t participate in the game. In REVII, since there is a degree of separation between player and avatar, our attention is specifically brought to Ethan’s flimsy-seeming motivation. In fact he moves forward because we push him forward, we keep him fighting. There’s a sadistic, manipulative relationship between Ethan and the player, but it’s also more complicated than that.

We sympathize with Ethan because of his love for Mia. Still, in some of Ethan’s barks and challenges to the Bakers, he expresses confusion, true ingenuity, sincerity, and a surprising and inspiring amount of courage and mettle. These motivations are enough for us to bind with Ethan, more so than in any other game in the series. Ethan is dumb, and we love him for that.

Mechanically speaking, first-person allows for some admittedly cheap but still fun jump scares, but it more importantly creates room for and necessitates an extreme amount of detail. Players can inspect drawers, cabinets, and cracks in the floorboards, unlike ever before. Monsters have a more threatening sense of scale, and so Resident Evil VII frequently plays with perspective and height, making its signature footsoldiers, the Molded, lumbering, giant masses of black knots, while also making its primary villain surprisingly pint-sized.

The first-person perspective also gives way to an effective new move, the block, crucial on the higher difficulties. The block gives Ethan a defensive verb and sort of grants the player a satisfying “cower” button. It doesn’t always make sense (how could an arm block a chainsaw?) but it paces out the game quite well against melee enemies, and it lends a visceral clutter to an already elegantly messy game screen.

Speaking of visceral—the new perspective’s greatest strength is probably the way it facilitates body horror. In RE7, you’ll have limbs chopped off, knives driven into your ribcage, and horrible masses of crawling grubs shoved down your throat. It’s a very personal, intimate horror, one that wants to gross you out while it makes your controller shudder and vibrate in resistance. It brings the player deeper into the shell of Ethan, and it creates a atmosphere of trapped, hopeless dread.

In a way, Resident Evil has been grasping at this perspective since its inception; think of the first encounter with a zombie in the first title, how the game shifts to Jill or Chris’s eyes, how the undead slowly turns to face you, its rotted mouth stuffed with human brain. This moment of body horror was essentially our introduction to Resident Evil’s mood. The perspective in Resident Evil VII, and our mouth being stuffed full of rotten flesh as we watch on, helplessly, brings the whole thing to a complete circle.

Kinetics

The movement in Resident Evil VII is deliberately slow, almost plodding. There’s a sense of weight to Ethan and his actions, necessitating such things as the aforementioned block button as well as a dedicated turn, a verb that is becoming more and more common in triple-A games, it seems. There is a sprint button, but there’s no real way to get Ethan to break out into an actual full-on run, ironic considering the urgency of the situation he’s in.

You could hand-wave away his plodding speed by saying it has something to do with his recent infection, but the Resident Evil series has always inhibited its protagonists in order to simulate the physical ramifications that fear has on the body. Despite arming the player to their proviberial teeth, early RE games aren’t about player empowerment; they still want to be a struggle to survive. So the series balances its arsenal of weapons by inhibiting the avatar’s movement. This is of course subverted in Resident Evil 4, further dismantled in 5, and completely out the window by the time 6 rolls around, but 7 is, again, intended as a return to form, and so we see a slower pace to all of Ethan’s movement. It makes up for the increased precision in aiming that the first person perspective allows.

REVII’s movement and control schemes are nowhere near as innovative and revolutionary as RE4’s over-the-shoulder controls or even RE1’s tank controls. But they still work remarkably well, and this is largely due to how the environments are designed to accommodate them. RE7 is filled with little nooks and crannies that demand careful consideration. Most of the time, they’re empty, but they are so discomforting they feel like intrusive negative space. A quick-turn button means that you always have a way to quickly glance over your shoulder. It creates a paralyzing set of blindspots to the player’s immediate left and immediate right.

Some of the guns in RE7 feel flimsy to fire, unsatisfying and cardboard-thin. The pistol has little weight or feedback, and despite the fact that the submachine gun is one of the most effective weapon in the game, it never really feels great to pull the trigger. It’s all just a bit too high-tech and light, and it clashes with the game’s mood. The shotgun, on the other hand, is incredibly satisfying, with a wonderful kick and a beautiful cascade of gore and blood to compliment each round. Meanwhile, swipes with the knife feel weak and desperate, appropriate as the knife will be little more than a box-breaker or last-ditch effort for the player.

I want to note how well the sound design compliments the movement in Resi 7. Each creek of the floorboard that comes with each step enhances the mood. Everything works harmoniously towards a feeling and an atmosphere, even if it isn’t, by the strictest definition, realistic. Remember, Resident Evil VII doesn’t strive for realism. It strives for a different sort of immersion, one that engulfs the player in familiar iconography rather than relatable and recognizable situations.

The puzzles in Resident Evil VII include the lock-key affairs that are synonymous with the series, though some of them work in interesting or subversive ways. Take the shadow puppet puzzles, that ask the player to rotate a certain key until it casts a shadow that fits into a mold or image. It’s clever to ask the player to think about the game’s lighting; it weaves together the environment and the objective. It draws attention to light and shadow, it takes time and manipulation. What it doesn’t quite take is the lateral thinking necessary for most of what you’d call puzzles. No, the puzzles in REVII are slave to the game’s pace, not its challenge. They give you tasks to do, things to fetch, and moments of quiet discomfort to break up the sometimes bombastic noise of gameplay.

Doors

Doors play a significant role in the Resident Evil series. In the first title, they masked loading screens and acted as gateways for player progression—a lot of that game’s pacing is defined by finding and using keys. In REmake, some doors will shake and slam as you walk past them, implying that enemies are waiting for you on the other side.

But doors are also important tools for survival; each door in Resident Evil is a barrier to keep enemies at bay, because each room is treated as its own discrete environment. Zombies (mostly) can’t get through doors. If you can’t deal with an enemy or enemies, you flee towards the door and use it to place a divide between you and them. Doors are powerful mechanically and thematically in Resident Evil and REmake.

In RE7, they work in a different way. You press a button to initially crack them open, but the game makes you physically push them open as a separate action. In this way you must commit actual movement to the action of entering a room to open a door. You need to make a serious mental and physical investment in order to progress.

This is nothing short of brilliant. You can’t back away from a room after opening the door and survey it for safety before plunging in. You have to go in headfirst, and this gives the game control over moment-to-moment player progression. The doors in Resident Evil VII area synecdoche for the game’s entire design; a mindfulness in mood, movement and control that services a feeling rather than a sense of realism or accuracy.

Videotapes

Resident Evil 7’s obsession with horror films extends beyond the game’s aesthetics and into its mechanics. It is fascinated with the concept of video tapes, beyond simply using these tapes as a way to evoke the mood of found footage horror. Rather, it finds a mechanical purpose for the tapes, turning them into puzzle pieces that help Ethan escape.

When we are first introduced to the videotape mechanic, it’s in the initial shack area, part of the demo that was released before the full game. The tape belongs to an unlucky film crew, working for some imaginary (but wholly believable) reality show about plumbing the depths of abandoned houses. In what is RE7’s most obvious expression of its main purpose—placing the player in a horror movie—the player takes control of the cameraman, and indeed the camera itself, and by proxy—through the method by which Ethan diegetically experiences this scene—the tape. We are the footage, and though it supposedly happened in the past, we are now controlling it in real time.

Disturbingly, the crew goes through almost exactly the same paces that Ethan went through just moments ago, and since we see how it ended up for them, it suggests that he is probably in a great deal of danger.

But the tape shows that there is a secret passage in the fireplace, one that the player could have totally missed without its aid. This establishes a pattern; the player will encounter three more tapes during their journey, and each one will convey a little more information and context to not only the player, but to their avatar, Ethan, as well. Not all of the tapes are mandatory for progression, but they are a wonderful way to present missing pieces of the puzzle to the player, through methods that are thematically appropriate and never wrestle control away from the protagonist. The tapes are essentially keys, but they are infinitely more interesting than a simple progression lock.

The most effective and interesting tape is perhaps the most well-hidden one. “Happy Birthday��� is buried in a cupboard in the attic, and it is disturbing footage kept safe and secret by the Bakers’ son, Lucas.

The footage is of an elaborate deathtrap set up by Lucas, who’s positioned as a sort of genius psychopath as an in-universe explanation for some of the game’s puzzles. Lucas has captured one of the poor erstwhile documentarians, and the player takes on this victim’s perspective. Interestingly, all semblance of artifice—a camera recording the footage—drips away in favor of this perspective. Through the magic of movies, we become this character, one-step removed from our hero Ethan, yet still somehow viewing it through his eyes. If the intro tape had us jump back in time to where Ethan has been, this tape foreshadows where he will go.

Since we already know that the victim of the trap doesn’t survive, it’s not a failure to participate in Lucas’s machinations. Instead, it’s presented as the scripted, linear path that we must follow. The lethal puzzle culminates with a task that requires the victim to uncork a barrel of oil, leading to the explosion that ultimately kills the victim in the tape. But the action that springs this trap just yields a password. If one were to go into the trap with some prior knowledge of that password, one would be fine. And that’s exactly the position the tape leaves Ethan in. Since he, by way of the player and the tape, already knows the password, he’s able to escape Lucas’s trap unharmed.

This means the tape isn’t necessary for success. If the player somehow fails to find the tape, they just have to play the death trap twice. Once they continue the game and run through the puzzle a second time, they’ll realize they can just skip over the deathtrap, since they already know the password. It’s a puzzle that is proofed against stumping a stumbling player.

It also extends the horror movie motif pulsing at the heart of Resident Evil VII. It’s an attempt at creating something that the series has sometimes dabbled with, but never fully explored–the idea of elaborate, claustrophobic death traps. You’ll see spiked walls and bottomless pits in other Resi games, but never something quite so sinister and unique, not to mention devoid of enemies or threats beyond the traps themselves. It is a quiet, challenging horror, one that pits the player against themselves, and I think it’s more than strong enough to stand on its own as a full game.

The video tapes in Resident Evil VII stand hand-in-hand with the tape recorder save points and evoke a certain era of technology, a halted progress that crystallizes the Baker mansion at a moment in time, and suggests that they’ve paused their evolution. It also subtly reminds players of a time and a place, the same crucible of factors that led to the creation of the horror films that inspired Resident Evil VII. It’s a horror born out of grime and dust rather than shadows and moonlight.

Jack

Jack is the first member of the family you encounter; you catch a glimpse of his form plodding through the woods, and he eventually kidnaps you and brings you to the centerpiece of REVII’s introduction, the family dinner, where he makes himself known as an intimidating and controlling presence.

After Jack’s pulled away by the arrival of a deputy, you escape from your binds and start to move through the mansion, but of course he quickly catches on to your plan. What follows is the most compelling, proof-of-concept sequence in all of RE7; a game of cat-and-mouse through a tightly wound series of narrow corridors, with the slow-moving but ultra-powerful Jack following you close behind.

The wing of the house that Jack chases you through is a well-thought out arena, with a few hidden escape hatches and multiple ways to double-back. It makes movement and navigation feel clever and fun, while still keeping a sense of looming dread. You’ll double-back multiple times, and you’ll always have the plan b of escaping back into the safe room on the opposite end of the hallway, as far from your objective as possible.

This scene is marked, most notably, by a few scripted scenarios designed to catch the player off-guard; one, Jack can burst through a wall and surprise the player, but only if both characters are positioned just right—some players will never even see this sequence.

It takes courage to develop entire sequences that some players will never see. It’s difficult and resource-intensive to design and place such moments in a game. But it pays off in REVII; these moments are some of the most memorable in the entire game, and you can tell a lot of care and time went into making Jack’s sequence pitch-perfect. It’s truly the highlight of the game and a Capcom more willing to take a huge gamble might have used it as the entire framework for the game. As it is, it’s the stand-out chapter in the game.

After a bit of exploration and a few confrontations, you’ll encounter the now most certainly undead Jack Baker, during an otherwise slow-paced hunt for a few statues. He catches you off-guard and the game challenges you to once again play cat-and-mouse. As a result, the entire Jack encounter sort of plays like a three-act structure in its own right; you encounter him once, run away, quiet exploration, encounter him again, more puzzles and exploration, and a final, bombastic, Evil-Dead-as-hell encounter in an enclosed space.

The fight challenges how well players have learned to navigate tight corners and small spaces while evading a slow-moving Jack. Perhaps it would have been more appropriate to present them with a cat-and-mouse challenge, one that added new wrinkles in order to act as a sort of final exam for the Jack chapter. But it’s hard to argue that this fight isn’t a trippy power fantasy for the player, and the way it flips the player’s relationship with Jack works.

Ethan has now escaped the mansion, but finds himself in the Baker grounds writ-large. The game doesn’t open up or become less linear, but it does explore some novel new locations. Unfortunately, that variance comes at the cost of some consistency. Before moving on to the next location, the player encounters a trailer belonging to Zoe, who ostensibly sets herself up as a mysterious ally. We first encountered Zoe through a phone call in the Baker house, where she warned us we were in grave danger. Zoe is not that interesting as a character, and mainly serves to complicate the game’s narrative, which starts out simply and becomes more and more complicated, to its weakness. Zoe is an element of that. She’s not well fleshed-out in the main game, and she’ll later be part of an arbitrary and superfluous player choice that feels tacked on. Here, however, she’ll play the role of mysterious sherpa for a while.

After a short break to resupply and catch their bearings, the player will soon enter the second house, the old house, and the domain of Mrs. Marguerite Baker.

Marguerite

Pacing-wise, Marguerite’s domain is when RE7 really starts to slip in its footing. It’s not exactly bad gameplay, but it does sag a bit, and a few fetch-quests lead to the previously mentioned flamethrower and a pretty frightening if rhetorically uninteresting tape starring Mia.

Marguerite’s gimmick is insects, cockroach-like bugs that swarm Ethan, fly around the damp wooden shack, and build nests that the player must flush out using the burner. The bugs create some variance in the enemies that RE7 will throw at the player, but they aren’t terribly fun to fight. What’s more, the old house doesn’t feel quite as well-thought-out as the larger Baker Mansion, and though it also follows a somewhat circular layout, its hallways and doors are less distinct, and its rooms are less geometrically interesting.

Jack is horrifying because he feels threatening and powerful. Marguerite is horrifying because she’s unpleasant to see or hear. It’s a skin-deep horror that relies on physical reactions rather than mental ones. Marguerite is repulsive, not necessarily terrifying.

Perhaps most disappointingly, we don’t learn very much about Marguerite at all, before or after her infection. Jack gets a moment of redemption later in the game, and Lucas and Zoe are fleshed out in conversation and flavor text around the Baker estate. Marguerite, on the other hand, only gets bits and pieces of story—she’s really more about an image than a fleshed-out idea. The DLC supposedly characterizes her out a little better, and gives hints to what she was like pre-infection. There are glimpses here and there that suggest she had an affinity for religious iconography; she has a habit of creating small shrines to Eve’s “gift.” This was a potentially rich vein that Capcom could have explored in more detail to make Marguerite feel like more than just a wife and mother.

The highlight of Marguerite’s section, by far, is her boss encounter. Set in a small two-story greenhouse, the boss fight begins when she startles you by popping through a window and grabbing your legs. At this point, she has mutated into a Junji Ito-style horror, with long arms mimicking spider limbs.

Her boss arena is a work of art. While Jack’s pit is somewhat simplistic, Marguerite’s stage has a layout simple enough to grok but complicated enough to provide ambush points and blind spots. There are doors that are blocked from one side, but give the player a route to double-back. There are ceilings and walls and windows for Marguerite to crawl on and climb through. There’s ammo hidden in cabinets, but there’s a risk-reward of wasting burner ammo to open these cabinets—though the burner is the most effective weapon against the matriarch. And, echoing the gameplay in her larger domain, the boss fight is dampened by moments of quiet stalking, though here the line is blurred between cat and mouse; you’re fighting back, and if you can control the tempo of the fight you’re frequently on the offense.

There is some sexual imagery to Marguerite’s final transformation, as her weak point is a hive-womb, and she crawls around on all fours while stalking you. It’s RE taking a page out of Silent Hill’s book, and it might feel a little cheap and grotesque if it wasn’t executed with the grimy style of a western grindhouse horror flick. No, REVII has little reservations about what it is by this point; it fully accepts that it is campy gross-out horror, but never to the level of shtick. It still takes its scares seriously, and this level of sincerity lends it a lot of heart. It makes no apologies for being disgusting, and in that way it’s lovable, just like the shlock it’s based on.

After a grueling fight, Marguerite calcifies and crumbles to dust, leaving behind a lantern for Ethan, who is free to move on to the next chapter of the game.

Eveline (Part 1)

But before Ethan moves on, he makes a detour to the attic and the kid’s bedroom.. Demonic children are nothing new, horror-wise, but REVII sows the seeds of its main antagonist achingly slowly, placing her quite literally right under the player’s nose while still breadcrumbing morbid story details to keep the hook. It’s not a deep story, or even all that unpredictable, but it is compelling enough to push Ethan forward.

You’ll notice I’m not paying much mind to the grand details of the plot, and that’s precisely because the story is secondary to a mood. This is why so many of its characters are so tropey. They don’t need to be real people, they need to serve a purpose.

If this is all sounding a bit harsh, let me assure you; I fully believe anything other than REVII’s broad strokes narrative would probably feel a little too fiddly and intrusive to serve what the game is trying to be. There’s just enough dressings of a compelling story to keep players interested in what’s going on, and that’s exactly the way it should be.

The Baker’s son, Lucas, plans to make you work hard to reach his lair, and as a result there’s a quick and gruesome return to the main mansion to fetch a key out of a corpse and battle some extra molded. This largely feels like filler and fluff, but it goes a long way to building Lucas up as a bit different from his parents. He’s more sinister, more cunning, more self-aware and human. You’ll also encounter Grandma a few more times, placed within the critical path, always watching and always silent.

RE has always been noteworthy for its clockwork puzzles, and the series has frequently lampshaded these puzzles in cute if unbelievable and ultimately unnecessary ways. The police station in RE2, for example, was supposedly a decommissioned art museum, as if that makes any sense.

In REVII, though, it’s the machinations of a character, the inventive, sociopathic Lucas, who, as it turns out, is a major antagonistic force behind the game’s entire plot. His reveal as the true antagonist of the game is brought on with little fanfare. It’s mostly revealed in DLC and notes. But it’s similar to Wesker’s heel-turn in RE1. It doesn’t purporte him to be the main villain of the game, but it sets him up as a possible series-wide antagonist.

Your mileage may vary out of this twist. Some might like having a face to the horror, and the stories of Lucas as a child, spying on his sister and setting traps for neighborhood bullies, are chilling in a lasting way. But the game doesn’t do a great job of selling Lucas as a planner, and the whole thing feels a bit contrived in the face of REVII’s greater narrative.

Lucas

In the Videotape section, I discussed the happy birthday tape and how it uses the conventions and structure of a video game to set up REVII’s most interesting puzzle. I briefly glossed over how the tape and Lucas as a character invokes the found footage aesthetic so important to Resident Evil VII’s style, but in the Happy Birthday puzzle—and through the rest of Lucas’s death traps—we see another piece of horror movie inspiration come to life; the complicated, convoluted deathtraps of films like Saw and Cube.

This sort of claustrophobic psycho-horror came about out of budget constraints. The first Saw was hugely influential because it allowed for an inexpensive yet wholly effective reworking of the slasher flick. It was successful commercially, and it was appealing to producers because it had the built-in simplicity of a few simple sets and some inexpensive practical effects. It was a streamlined reworking of the genre for the 21st century.

If Jack stands in for the ‘70s-era slash-fests like Texas Chainsaw, and Marguerite is a melding of ‘80s and ‘90s body horror from the West and the East, then it’s temporally appropriate that Lucas is the representative for 21st century gore flicks. In a way, REVII is a tour of the genre’s modern history, an exploration of its tropes as they evolved. It’s a love letter to three eras of horror.

Mechanically, Lucas challenges the player to stop, move slowly and deliberately, and fully assess the environment. There are tripwire bombs and spike traps littering the hallways of his home, and though you will still fight standard molded, they’re sort of a trivial threat by this point. No, Lucas demands that you think about the game’s environment as hostile and unforgiving. This is something of a change when compared to the circular, narrow hallways in the Baker Mansion and the Old house, where the game’s architecture and hidden pathways were one of your only weapons against your pursers. Here, Lucas isn’t following you, but he’s attempting to anticipate your movement. You’re not being chased, you’re being funneled.

Lucas leads you into the Baker barn, which he’s set up like a gladiatorial arena. If you needed any further evidence that the game is now fully banking on Saw homages, the hanging pig-corpses should be proof enough. This environment is incredibly quiet at first, but its architecture betrays its true nature; the intersecting, stacked hallways are layed out too perfectly for it to not be some sort of combat arena. In most games, this discord can be laughable; in Resi VII, it builds tension and suspense, and therefore works a little better than it might in, say, a pure action game or a shooter.

Depending on your difficulty, you’ll face some number of a new type of enemy, the fat Molded. These are bulky, powerful enemies who spew bile, one of the few projectile attacks in the game. Overall, they’re more intimidating than actually threatening. By this point, you’re armed to the teeth, and the barn’s layout gives you plenty of ways to obscure line of sight and take cover. But this boss encounter most vitally introduces the fat molded into the ranks of foes you’ll encounter. Resident Evil has a history of introducing powerful minions with such fanfare; they bring around a new, tough enemy type, build them up as an intimidating, powerful force, and then later seed them into the ranks once the player is more capable. It’s a way of ramping up combat challenges and creating an interesting endgame.

Next up is the happy birthday puzzle. Once you beat Lucas’s escape room, he gets angry and tosses a bomb into the room, which you can use to blast the wall and escape. By the time you make it to his control room, Lucas has already fled. There’s a short trek to the boathouse, and a fully-loaded safe room is a pretty good indicator that a big fight is about to go down. There’s a sense of finality to the proceedings, considering that you’ve now worked your way through the main Baker family. Still, there’s something like a quarter of the game left, and it’s when most people say REVII really goes off the rails. The pace and mood of the game is about to undergo a major shift. But first, it’s the final battle with Jack.

Jack’s Return

Ethan’s final encounter in the Baker residence brings his time with the family full-circle. Jack has come back from the dead yet again, and he’s mutated beyond any recognition. This is the beginning of REVII’s slide fully into the conventions of the series, away from the new-age slasher flick pastiche and into the gamey, japanese bio-horror that defines the series.

The fight with Jack is a fairly standard boss battle that asks you to shoot the glowy parts when they start getting glowy. There’s a smart sense of player-enemy placement and blocking and a clever use of levels that keep the fight from feeling dull.

The barn burns over the course of the fight, and eventually it’s all but completely destroyed. Once the fight wraps up, Jack will grab you as a final deathrattle, and you’ll be forced to inject him with one of the two cures you’ve cooked up. This means you only have enough serum to cure one other person, and the game is going to make you choose—do you fulfill your promise to Zoe, or do you stay loyal to your original mission, and rescue Mia? It’s a dull, binary, choice that simply determines the ending of the game, as well as what amounts to an optional boss fight. It’s set up to either reward or punish the player, rather than challenging their conceptions of the game’s world and Ethan’s place in it. Put simply, there’s a right answer and a wrong answer, which makes it fundamentally uninteresting.

Whoever the player chooses, the pair will then make their escape down the river.

Mia and the Tanker

The boat crashes, and REVII plays its final third-act twist; a shift in perspective, moving the action behind the eyes of Mia, who is all-too-familiar with the washed-up tanker. The twist is that Mia is much more than she seemed and was hiding a few secrets from Ethan. She’s a mercenary, hired to escort a bioweapon on a commercial tanker in a covert operation. That weapon is Eveline, the main antagonist and the driving force behind the sentient Molded force that both corrupted the Bakers and created the monsters the player has battled this entire game.

This twist is nothing short of baffling. It is unexpected, but it is not a subversion of any player expectations; it’s a twist that devalues the previous rising action rather than usurping it, and it inflates the scale of the game’s conflict beyond ‘creepy house’ and into ‘international high-stakes bioterrorism.’ It’s disingenuous and exhausting, as Ethan is now relegated to a bit player in a bigger conspiracy.

All that being said—it’s Resident Evil sinking back into its traditional mold. Wesker’s heel-turn and the Umbrella conspiracy elevated the first game’s spooky mansion into a secret megascience lab. That twist set the pace for the series as a whole; a convoluted narrative rooted in a distinctly Japanese anxiety over superweapons.

Here’s the thing; I don’t think the twist is all bad, actually. I think there’s something charming about how RE feels it is so vital to create a wide, entangling conspiracy to tell such a tight and quick narrative. It’s an impulse that the series truly cannot escape, for whatever reason. It is never content to tell a story about horror on a small-scale. It needs to dip into some kind of worldwide threat in order to tie all its narrative strings together. Would REVII be stronger without the tanker chapters and the larger ramifications of its effect on the narrative? Probably. Would it really be Resident Evil without such a grand mega-conspiracy at its heart? I’m not so sure.

It’s a complicated issue, because it begs the question; how much can you mess with a series’ DNA before you have an entirely new product? Is a mood enough to connect a series, or does there need to be an underlying thread that connects all the titles to its past? Is there simply too much baggage attached to such a massive beast of a franchise for it to ever escape its own legacy?

Ostensibly, the theme of Resident Evil VII is family. It’s the driving force that causes Eveline to throw off her controllers and drive the game’s plot forward. It’s the bond that causes Ethan to go after Mia, and it's the question that Zoe struggles with as she turns against her mutated clan.

Conversely, then, it is appropriate that Resident Evil VII struggles against its predecessors and the legacy they have created. Like Zoe, it is fighting for its own identity while still maintaining a certain loyalty to its origins.

Eveline (Part 2)

The last location in the game is the salt mines, which act as a sort of final combat dungeon, overrun with Molded. Unlike the tanker, however, the salt mines afford the player a ton of firepower and ammunition. It’s all about player empowerment now, as the scales have been tipped in Ethan’s favor. Fighting the molded is now trivial.

The mine is also set up as a sort of ground zero for the Molded. There are secret labs and documents filled with research on the molded dotting offshoots and chambers.

There’s a thrilling race up a spiraling column and a few more fights with the fat Molded between Ethan and Eveline. She’s in the guest house, and this final confrontation acts as more of a cathartic emotional highpoint than a final gameplay challenge. The mines were the real final test, and though there are some small challenges to the encounter with Eveline, it’s more in position to wrap up REVII’s mood and story.

The player is now up against Eveline’s psychic powers, and it’s about as hokey as it sounds. However, the audiovisual presentation is strong enough to suck the player in, and it still feels emotionally resonant and threatening, even when dipping into the absurd.

After the player figures out how to guard against Eve’s blasts, they reach her decaying body. Like Lisa trevor in REmake, Eve is positioned as a victim of larger, sinister forces, a capitalist war machine that took a little girl and turned her into a weapon. This sympathy for the devil ultimately induces genuine pity for Eveline, and it, again, shifts the focus of the story onto a more worldwide conspiracy and less on its play actors.

Eve’s final form is massive and grotesque, but most poignantly, it is part of the house itself. The Baker estate has been Ethan’s sometimes-ally, sometimes-enemy, and it’s only appropriate that it takes a leading role for the final moments of REVII. The final set piece is one of a massive scale, and it brings attention to the sky above, where dawn is beginning to break through what has been a seemingly endless night. Evenline mutilates Ethan one more time as choppers begin to fly in overhead, and finally, a deus ex machina in the form of a massive handcannon lands next to Ethan’s head. He fires a few rounds and Eve crumbles to dust with a final deathknell.

Ethan is rescued by a man introducing himself as Redfield and working for the series’ signature villians, the Umbrella corporation, and REVII, despite itself, insists on teasing its place in the series’ overarching, complicated mythology. A brief epilogue showcases some more lovely, True detective-esque air shots of Louisiana over narration from an exhausted Ethan, before fading to credits.

Resident Evil 7 is a revisioning of the series that coined the term survival horror. It’s an invocation of a mood and aesthetic, brought into interactivity. It is a product of its technology and time, as such a detailed and intimate horror wasn’t possible even in the last console generation.

At the same time, it’s also a troubling return to form. Resident Evil can’t seem to escape the baggage of its prequels or the conventions of massive conspiracy that provides the framework for its otherwise small-scale horror. It is an antithesis to itself, as it attempts to invoke personal intimate horror through large-scale conflicts between massive capitalistic and militaristic conglomerates. A Resident Evil game will inevitably go off the rails at some point, but its mood and method determines if the player will be along for the ride. RE4 went from moody creepout to action-packed campfest, and it never missed a step. REVII stumbles a bit more, but it promises a strong return to what made RE great, especially after a few strange forays into action in RE5 and 6.

Yet REVII didn’t enjoy the commercial success of those two titles, though it did see a fair bit more critical acclaim. It’s a bold move to shift a tentpole franchise as dramatically as capcom did between RE6 and REVII, but the game is clearly a love letter to its inspirations. REVII is a celebration of Western conventions seen through a Japanese lens, It is a product of dissonance, and that’s what makes it so compelling.

Despite its flaws, Resident Evil VII is one of the best horror games of the latest generation. It provides genuine moments of horror and a piercing, inescapable atmosphere of tension and horror. It is cathartic and wild, moody and visionary, and awe-inspiring in its execution.

Maybe the next entry will lean further into the horror aspect of survival horror, and will have the courage to shake off a messy legacy of legions of the undead.

#resident evil#resident evil vii#criticism#games writing#games criticism#capcom#horror#horror games#survival horror

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blade Runner 2049 Critique

A few days ago I noticed a throbbing pain on my forehead.

It was at work when I first felt it—or rather, it first dawned on me that what I was feeling was discomfort. Not just a headache from staring at a screen all day, but a more epidermal pain, like a pain in the face rather than the head.

When I got home, I looked in the mirror and realized why; there was a whitehead looming under my left eyebrow, standing at attention like a soldier, driving a red throbbing pain down under my skin and toward my skull.

I examined the blemish in my bathroom mirror, inspecting a region of my body that I had never really looked at that closely ever before. It forced me to see myself in a novel way. I took inventory of every individual hair making up my brows. I counted the thin bristles bridging the gap between the two thicker, prominent bushes of hair above my eyes. For the first time in my life, I counted each hair and examined these features closely, all in service of combating this new and unwanted blemish above my eye, a blemish that caused me great discomfort and pain, and not just out of a sense of vanity.

Blade Runner 2049 implores its audience to examine their flesh critically, the same way that a blemish might. It is a soft reboot of Ridley Scott’s 1982 film about androids and the humans who hunt them, but unlike that film it does not concern itself with the dichotomy of man vs. machine. Instead, it is a story of populated almost exclusively by automatons.

There are machines who are more ‘real’ than others, because they are made of synthetic flesh instead of columns of light, and we are forced to consider how appropriate it is to make this distinction. This eventually evolves into a subplot that will remind audiences of Spike Jonze’s Her, a subplot that ultimately feels somewhat idiosyncratic with the rest of the film. The protagonist, a Blade Runner named K (and later Joe) is in love with his household hologram assistant, an AI that lives in a handheld device and chirps out the opening stanza of “Peter and the Wolf” every time it is booted up.

This subplot feels like a critique of smartphones and how they’ve paradoxically isolated us from one another while building a false sense of community. Some critics have interpreted it as a critique of the male gaze as well, but of course, like most cinematic critiques of the male gaze, it still indulges in the pleasures of that same gaze, leading its audience to wonder if it is truly saying anything novel about the topic at all.

There are a few humans in the film. Most of them die. The human who survives is the creator of these machines. As a viewer, I would have been happier if he had died to the machines, because he is a cruel and despicable man. Though he’s made of flesh and blood like I am, I feel far more connected to the machines than him. Ultimately, that’s the greatest triumph of the film—Villeneuve successfully creates empathetic characters who we know are not human.

Sympathy for the synthetic man in fiction generally comes with some caveat—Satan is cast out of paradise for his arrogance, Frankenstein’s Monster is a murderous sociopath, the parts of Darth Vader that remain human are weak and pale, et cetera. Even the original Blade Runner looked down at the enslaved and subhuman Replicants.

But Blade Runner 2049 loves its Replicants. They have consciousness, thoughts, feelings, desires. They like and dislike. They love and hate. We’re not told this, but we see it. Just like Her, 2049 passes no judgements on its subjugated artificial class. This too, is a triumph.

Finally, it’s daring that Blade Runner 2049 hinges its entire plot on the ambiguous final note of its predecessor, but it’s worthy of praise; like The Force Awakens, it's clearly a film made by a fan, because it poke and prods at the corners of its predecessors’ vision, instead of diving deeper toward the original’s focus. Villeneuve realized that the Replicants were always infinitely more interesting and relatable than the humans in Blade Runner, and so he goes all in on building them as sympathetic outsiders.

At the same time, he capitalizes on their intimidating strength to create a compelling, terrifying villain. The difference between this villain and the sympathetic Replicants is that she is fiercely loyal to her human creator instead of her own kind. A loyalty to a corrupt system of power is the only trait separating her from the heroes. The villain is a traitor who strives to be great in the eyes of the Other, in this case her creator, instead of sympathetic toward her peers.

The original Blade Runner is a juggernaut of mood and atmosphere, a bloated and beautiful tribute to the techno-paranoia of the 1980s. It’s home to some incredible world-building, which is one of the great strengths of science fiction as a genre. I’m reminded of the William Gibson quote regarding Escape from New York and how it influenced Neuromancer:

"[I was]....intrigued by the exchange in one of the opening scenes where the Warden says to Snake, 'You flew the Gullfire over Leningrad, didn't you?' It turns out to be just a throwaway line, but for a moment it worked like the best science fiction, where a casual reference can imply a lot."

But Blade Runner is a very slow movie and its entire plot could be summed up in a single sentence: A man kills robots, but he might be a robot himself.

Blade Runner 2049 is not a slow movie, though it is exceptionally long. Its plot is a gordian knot of twists and turns and complications, all culminating in an action scene with, imagine this, quiet power and dignity. The final confrontation in the film feels like high-budget Hollywood fisticuffs shot on an abandoned set from Ugetsu.

The original Blade Runner’s final confrontation happens on a rain-slick rooftop. There is a diluvian connection between the two films’ conclusions, and any film student would tell you that rainfall in cinema frequently signifies a rebirth. This surface-level interpretation of Blade Runner 2049’s ending is a serviceable explanation, but I don’t buy it; I think the film’s conclusion happens where it does and how it does because it is clean and satisfying, unlike the world in which the film is set. Things are wrapped up quite nicely, but enough is left ambiguous for the audience to imagine their own version of a happy ending. There are open doors, but not necessarily the echoes of franchising. Combine that with 2049’s failure at the box office, and a sequel seems fairly unlikely.

Blade Runner 2049 rose from the swamp of Hollywood’s nostalgia-rush, of course, made to capitalize on a beloved property. Despite its critical success, it’s been unable to stand toe-to-toe financially with Star Wars or Marvel. Anyone could have told you that would happen.

It would be futile to compare this film with either of those franchises, because it tries to accomplish something else entirely. But I will say this: Marvel’s Tony Stark puts on a suit of armor to look like a robot so he can stand among gods. Blade Runner’s K puts on a suit of artificial skin so he can stand among humans. In the end, the latter is more compelling than the former can ever be.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On ‘Kate’

Ben Folds Five’s brand of piano-based soft rock is wholly agreeable and wholly pedestrian. They play it safe and inclusive, never really branching away from the sound they first established with their self-titled debut and later extrapolated on with 1998’s touchingly personal The Unauthorized Autobiography of Reinhold Messner. Between that time, the band released what might be their most fondly remembered album, Whatever and Ever Amen.

Whatever drips with the classic BFF sound, though it still manages to play a wide range of emotional notes. From the revenge-ballad of “One Angry Dwarf and 200 Solemn Faces” to the heartstring tug-a-thon that defined the sound of an era, “Brick,” Whatever and Ever Amen is a classic. Not a masterpiece, mind you, but a collection of toe-tapping almost-alt singles that capture a time and a place, namely the prosperous-yet-angsty mid ‘90s. Despite this range, BFF maintains a consistent sound across the album; always safe-for-work, yet still daring to be different. Always melodious, yet still idiosyncratic, still fun, still weird.

“Kate,” the second single from Whatever and Ever Amen, is the story of a man in love with not a girl, but with an idea. The titular Kate is a bohemian, appealing because she, unlike the narrator and indeed the band themselves, is willing to be different, willing to break the mold in ways that may not be so safe. The narrator’s admiration doesn’t stem from sexual desire as much as it does from emotional envy. She’s free in ways that he is not. She smokes weed. She doesn’t change her clothes. She spends her days handing out texts from the Eastern philosophy she’s cultivated.

This is the story the narrator tells us based Kate’s appearance, having never actually spoken to her. She leaves him speechless, after all; he can’t even fathom her as a tangible, touchable person. Or rather, maybe, he doesn’t want to touch her. Meeting Kate would shatter this image of her as a perfect, free spirit, another from a world separate from his own. To have Kate, to know her, would snap that fantasy in half.

Instead he admires Kate from a distance, turning her into an object of desire in the process, removed entirely from the reality of who she is. It’s not affection or admiration that drives his desire. It’s envy. Admitting that would take an immense amount of courage. Instead of taking that leap into introspection, he channels this envy into romantic desire towards a stranger, turns his emotions outward instead of inward. “Kate” is about the complex feeling that makes us think we’re in love with the barista.

Appropriately, this story comes packaged in a pop-rock jam that can’t seem to muster up the courage to break from convention. It opens with a botched riff and a quick restart that sounds like a sweaty supermarket patron fumbling for exact change. The melody dares to flourish when it paints an image of Kate surrounded by woodland creatures like a Disney princess, but the second the song suggests the narrator speaking to her--

“Oh I….”

Have you got nothing to say?

--It falls back into the simple, agreeable, inoffensive sound that defines the Ben Folds Five.

In this, Kate is also a self-reflective statement from a band that has always admired daring to be different while never ceasing to play it safe. It’s the same notion that drives bookish teenagers to denim-drenched punk shows in dingy basements, and appropriately we see that idea surface its head in an earlier Ben Folds Five single, “Underground,” off their self-titled album. It’s also the same push-pull between conformity and individuality that fuels the autobiographical single “Army” that would follow Kate two years later, off Reinhold Messner.

Ironically, this desire is reversed in the concept of the solo Ben Folds album Way to Normal, a work obsessed with dodging fame to return to the stabilizing normality of middle-class suburbia. In that album, Folds wants to conform to escape the pressure that comes along with standing out, brought on by years of fame and success in the music industry.

Being different has not made him happy, and in reflection, it’s very likely Kate was just as unhappy with it, too. By its very nature desire can only be directed towards what we can’t have.

0 notes

Text

Peep Show is a Welcome Reminder That Everyone Else is Just As Crazy As You

I’m sitting and typing this review at a small café, seated at a table adjacent to the barista’s counter. To my right, just in my peripheral, there’s a middle-aged woman sitting with her preteen daughter, and though we’ve only matched eyes once I can feel that this middle-aged woman is just unabashedly staring at me.

It fills me with a sense of dread, guilt and anxiety, as if she knows that I spent the majority of my day watching old YouTube clips instead of getting work done the way I’d promised myself that I would. It feels like she knows that I ordered a $2.99 side of mozzarella sticks with my already unhealthy turkey bacon wrap for lunch. Like she knows that I skipped my daily workout this morning, for the fourth time this week.

She doesn’t know any of that, of course. This is all my own self-produced anxiety being channeled and funneled through the virtual only human contact I’ve had all day, because it’s easier to feel victimized than it is to feel self-loathing. Isolation is the real enemy here; I’ve been trapped alone with my thoughts this entire morning, and now they’re starting to betray me, and to make the whole experience a bit easier to digest I’ve started to interpret this middle-aged woman as some sort of specter of self-doubt when in actuality she’s just trying to enjoy her cup of coffee. There’s no way I could ever glimpse inside what this woman is thinking while she stares at me, and if there’s any real anxiety to be had, it’s over that fact.

That’s what makes Peep Show such a compelling comedic product. The brainchild of Jesse Armstrong and Sam Bain, Peep Show starts comedy duo Mitchell and Webb, two British comedians who met one another at University and had a short-lived (though successful) sketch show together, as was the bread and butter of young alt-comedians in the 90s. It’s a repurposed Odd Couple for the modern era, starring two flatmates, Jeremy and Mark, who act as antitheses for the other’s anxieties and hang-ups. Mark is an impotent armchair intellectual who’s afraid to venture even to the corner store lest he be confronted by actual human interaction, and Jeremy is a narcissistic wannabe musician who bases all his moral and ethical decisions on whatever sort of primal physical impulse he feels at that very moment.

It’s a typical set-up on paper, but Peep Show’s interesting hook is that it’s entirely shot from a POV perspective. Every camera angle is taken from someone’s sightline, and the entire show is underwritten by narration from our two witless protagonists. Often the humor comes out when their narration or interpretation doesn’t quite match up with the picture we see on screen.

Do you ever get the feeling that you’re just a little bit crazier than everyone else? That everyone around you seems to know what to do, even as you’re baffled by something as simple as mailing a letter or properly ordering the right sandwich at Subway? That there’s some big joke everyone else knows, and you just might be the punchline?

Peep Show is a welcome reminder that those feelings are common, and the only way you’d be abnormal is if you didn’t experience them at all. It’s a gentle nudge that assures you adjusting to the real world is understandably difficult, and that really you’re not any crazier than the typical person on the street—you’re just constantly trapped with yourself, forced to listen to every inane and insane little thought you think, and at the heart of that overthinking and self-reflection lies madness, self-loathing, and anxiety. It’s partially a product of the modern era, but it’s hard to say that it’s just a fleeting problem with a single generation. After all, Peep Show ran from 2003 to 2015, and even beyond that many of its plots and story structures will look familiar to fans of other British sitcoms like Fawlty Towers.

Typically in a sitcom, characters undergo a process commonly called Flanderization, wherein they become so ridiculous they cease to be believable people and devolve into strange caricatures. The term comes from Homer Simpson’s neighbor Flanders, who went from a nice-guy neighbor into a militant Christian and a hapless optimist over the course of the series’ twenty-something seasons.

Flanderization happens because characters in sitcoms have to be constantly raising the stakes, somehow, and this is typically done by externalizing their strange behaviors and allowing the viewer some sort of insight into their once impossible-to-breach motivations. In other words, they start to behave wackier and wackier, because we can’t hear what they’re thinking.

Peep Show doesn’t suffer from Flanderization because Jeremy and Mark never externalize their motivations. Instead, the comedy comes from their behavior clashing with their anxieties as they attempt to dress their failures up as roaring successes—both in the eyes of those around them and in their own twisted perceptions.

That’s not to say things don’t get crazy. Often, the fun in Peep Show is watching these two loathsome idiots reach a new low, like when Jeremy ends up cooking and eating a dog belonging to a woman he’s trying to seduce. It sounds insane, because it is. It sounds gruesome and gory, but it somehow doesn’t play that way; Jeremy isn’t doing this out of some sick twisted cruelty, but because he is so woefully dishonest with himself that he ends up backing himself into these dark corners of his own morality just so he can keep up his own delusional façade. It’s a dishonesty that many of us share, and in that way we can still relate to Jeremy while simultaneously despising him for his narcissism.

We’ve all been Mark and Jeremy, and that’s why Peep Show succeeds. It has no illusions about its characters being more charming, witty, funny or handsome than its viewers. Like Mark and Jeremy, we’re all damaged, we’re all anxious and we’re all less than we pretend to be on the surface, but in that mutual deficiency we find comfort, knowing that we all must be capable of much, much more than the sum of our own anxieties and self-doubts. Learning to overcome the seemingly inescapable anxieties that come with being a functioning member of society is the first step towards liberation and satisfaction, and though Mark and Jeremy may never find either of those things, they stand as reminders that it’s perfectly normal to be entirely abnormal.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mad Men: The Finale, One Year Later

A year ago, Mad Men ended, wrapping each of its branching storylines up with a neat little bow in stories that varied from triumphantly subdued (Joan’s humble but proud financial independence) to woefully shoehorned and misguided (Peggy’s sudden and inexplicable love interest). But the conclusion of Mad Men’s central narrative—the character arc of the once and future Dick Whitman—stood as a cryptic and, some have argued, deflated ending of what was intended as an epic spanning one of the most tumultuous decades in American history. Don sits on a cliff, content, guided in meditation. A gentle breeze grazes his face. The image is painted by organic colors; green grass, blue sky, blue sea, grey cliff, white shirt. A chime. A smile creeps across Don’s face. Music: It’s the song from Coca-Cola’s famous “I’d like to buy the world a Coke” ad. The image cuts to footage of the commercial. A diverse cast sings about harmony found through consumerism, peace found through drinking “The Real Thing.” Roll credits.

Mad Men can be a difficult show to digest and discuss because it’s largely about the power of ideology through imagery, even as it uses images to discuss its own ideology. The medium is the message and vice versa. I’m not just talking about the various campaigns the agency takes on over the course of eight seasons, either; the characters themselves are each on their own paths of personal discovery through crafting their own self-images, either in a desire to conform and fit in or in rebellion to the rhetoric and traditions that’s been stuffed down their throats their whole lives. They’re successful people on paper, with cushy jobs on Madison Ave., apartments dotting the skyline of Manhattan and beautiful rustic old boarding schools where they can dump their children reliably around age 12.

But under this thin membrane of success a slew of emotional problems and psychological hang-ups remain lurking. Don’s the most obvious example. Even his identity is a fraud, a construct created to carry him out of the hell of war where he was expected to proudly and courageously serve his country. Even after escaping Korea, he clutches on to the mask of Don Draper, not out of loyalty to the man that he accidentally slaughtered, but because it absolves him of his poverty and his place in the class system. He can become something because he is now a blank slate.

To say Don is a blank slate is a bit inaccurate. He’s still a handsome white man, and in America in the 1950s, that’s not exactly insignificant. What Don fails to realize is that his image, his identity, continually propels him to the height of success, despite the fact that he is perpetually running from who he is inside. He’s not a blank slate. He’s a billboard, propped on the side of a highway, ready to be painted with whatever idea or ideology is the highest bidder that month. He’s front and center, ready and willing to be seen, but he carries no substance with him, no backstory, no memories unrepressed. Or so he believes.

This image cracks the moment he confesses his history to the men at Hershey’s. He breaks down and is unable to finish his Opie Taylor-esque story describing how he’d be awarded a candy bar for loyalty to his father and he confesses his history in a whorehouse. He’s emotionally invested in the product he’s selling, and it’s here that we first realize, as an audience, that it might be Dick Whitman who has a knack for advertising, not Don Draper.

Imagery, like identity, is flexible, malleable, and that’s where its power lies. Don, or rather Dick, has been drawing on his trauma his whole career in order to create the miraculous work (or so the show implies) he’s famous for. With the Kodak Carousel, he sells us the family he never had. With Chevrolet, he sells us the wealth he had but never understood how to use. With Lucky Strike, he sells us the masculinity he feels he abandoned by running from the war. His identity has been imprinted on these products and their ad campaigns for more than 10 years.

The Coca-Cola ad is no different. It’s still Don drawing on the trauma of being Dick to produce an advertisement. It’s not some crowning moment of redemption or some sort of Coda that absolves him of his sin of constantly running from himself. Rather, it’s a moment of self-realization. He doesn’t find love. He doesn’t go back to his family. He finds himself. He finds motivation in his love for work.

If that sounds a bit mercantile and selfish, it is. Don’s not a hero. He’s not an icon, or a role model, or even a particularly likable guy. Remember when Cooper handed Don a copy of Atlas Shrugged and told him that they weren’t like everybody else? There’s some messy ideology about neoliberalism, objectivism and labor at work here, but Mad Men is a messy show about a messy world and a very messy era. What’s important here is that Don has found some sort of center, and whatever that is, it’s to be celebrated that he got there. Whether or not we’re satisfied with his story, at least now he can rest knowing he’s no longer a scared little boy hiding in the shell of a successful adult man, but a man that has grown because of the struggles that came from being a scared little boy.

#MadMen finale - a reminder 20th Century was great, but it's over & it isn't coming back. It's time for New American Century. #TheEndOfAnEra (https://twitter.com/marcorubio/status/600116092946685952)

That’s a Tweet from Marco Rubio dated exactly a year ago, in response to Mad Men’s conclusion. I’m not including it here as a criticism of his interpretation, but as an example of the power and malleability of imagery; in the same way that Don molds his identity to create advertisements, Rubio has taken the ending of Mad Men and used it to further his political means. That sounds sinister, but I don’t think it’s manipulative nor is it propaganda or anything else. It’s a critical process that we all engage in every moment of every day. We see images for what they are to us, but no two interpretations are ever exactly the same. Instead, we are staring at a warped reflection that asks us to build an identity we can comfortably live in. But in that process, we sometimes lose sight of who we are: Our histories, our privileges, our struggles and our desires. An identity is an image you sell to yourself. Don is finally ready to buy his own product.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The McDonald Christmas Review, Part 20

youtube

“Merry Christmas Baby,” India Arie and Joe Sample feat. Michael McDonald “Christmas with Friends”

I’m almost sure that I’ve run out of actual Michael McDonald Christmas songs, which was something that made me incredibly excited at first, because I thought I was free of this hellscape. But it turns out that Michael McDonald isn’t the only one doing shit like this, and a lot of the time his friends invite him to get in on the hot Christmas action. And it’s terrible. And it’s despicable. I mean, I realize I built this prison myself, but at some point crushing my dreams of any escape is just as deep a sin.

The best thing I can say about this song is that I really enjoy that India Arie, whoever she is, kindly decides to warn us when McDonald’s about to enter the song by singing his name in her dulcet, soft soprano. I appreciate having time to prepare.

Still sounds like McDonald’s trying to fuck me. Now I just think his friends are watching.

“Merry Christmas Baby:” 4/10

1 note

·

View note

Text

The McDonald Christmas Review Part 19

youtube

“World Out of a Dream” In The Spirit: A Christmas Album (2001)

A professor of Art History whom I respected a great deal once told me, adjusting his tie in a huff, that psychology was something of a futile practice.

“People have been studying the way the mind works for thousands of years,” He scoffed. “It’s called art.”

This is a pretty typical thing for an Art History professor to say, I’d imagine, and it’s the sort of statement you can bring home to the dinner table at Thanksgiving if you want to scare the shit out of your parents Re: Your new found passion for the Liberal Arts.

But it’s a statement I’ve thought about quite a bit, and it always brings me back to a quote from the playwright David Mamet on the role of artists that I once read online:

“Artists don’t wonder, ‘what is it good for?’ They aren’t driven to ‘create art’ or ‘help people’ or to ‘make money.’ They are driven to lessen the burden of the unbearable disparity between their conscious and unconscious minds, and so to achieve peace.”

Now you have something to scare the Folks at Christmas, too. You’re welcome.

There’s some truth in that statement, but there’s also some grade-A bullshit, because not all artists are the same. What I’m getting at here is that both of these very smart, very admirable men made two statements, and their statements were at once very much useful and very much bullshit, and it wasn’t until I heard them that those two ideas were brought together. I am the first and until now only person to have gathered both of these statements together, and to synthesize them into a new idea. I know this because the first statement was made in a private conversation, and even if that professor had presented the general idea behind the statement before, he hadn’t presented it in the same way, or capacity, because no two situations are identical. So I am the first to have brought these two thoughts together, and I have made them into a new thought, and that process is, in my opinion, the purpose of art. I hope you take this idea, dissect it, pull from your own experiences and turn it into something greater than what it is now.

That’s not why I’m writing about Michael McDonald. This is not art.

“World Out of a Dream:” 6/10

1 note

·

View note

Text

The McDonald Christmas Review, Part 18

youtube

“One Gift,” In The Spirit: A Christmas Album (2001)

Some say Christmas has its origins in the hedonistic feast of Dionysus, the god of wine, a holiday that the Greeks celebrated around the Winter solstice. There’s a lot of evidence to suggest that Jesus--that is, the historical figure of Jesus of Nazareth--wasn’t born during the winter (freezing shepherds, age disputes, etc.) and the Greeks, when adapting to Christianity, sort of felt compelled to keep all the fun parts of the old world order, including their incredibly icky wine orgies.

Additionally, some Christmas traditions, most notably the weird process of taking a tree and putting it inside, comes from pagan celebrations, something that people with a lot of time on their hands absolutely love to point out.

I guess I’m saying all this because while all that is true, it doesn’t make it any less of a steaming pile of bullshit, based on the general intention and goodwill of the holiday season.

Say what you will about consumerism. Say what you will about Black Friday and doorbusters and materialism and whatever. It doesn’t change the fact that the Christmas season has absolutely shaped our perceptions of family, responsibility and good character.

I don’t understand the people who are compelled to point out the negativity in something like Christmas. Why can’t people channel their criticisms to more constructive, more important applications? Think of everything that could get done with all that negative energy.

This song blows chunks, and Michael McDonald can kiss my festive ass.

“One Gift:” 5/10

0 notes

Text

The McDonald Christmas Review, Part 17

youtube

“Angels We Have Heard on High” In the Spirit: A Christmas Album (2001)

Look, man. I have a final tomorrow. My roommate’s never seen Star Wars so we’re showing him the Holiday Special and saying it’s Empire Strikes Back. I have no time to spend on Michael McDonald tonight. I guess,..I guess I could make a joke, like “Angels We have heard while high?” I don’t know. Fuck off.

“Angels We Have Heard on High:” ????/10

0 notes

Text

The McDonald Christmas Review, Part 16

youtube

“House Full of Love” In the Spirit: A Christmas Album (2001)

Identity is a funny thing, because it’s impossible to define in an unbiased way. The minute you see it is the minute it dissipates into ego. You cannot analyze yourself responsibly, so the best way to understand who you are is through your responses to stimuli like art and conversation and difficult situations.

I used to think that people were defined by the things they make, and that’s true to some extent, but it’s not the entirety of existence. You are more than what you give back to the collective, because you are an individual, a collection of thoughts and experiences that make up a whole together, for the first time, in you.

Basically, I am more than my reviews of Michael McDonald. And that’s a good thing.

This is not a Christmas song. It’s a nice sentiment, fine, but there’s nothing Christmas about it. He says Christmas, like, once and then spends the rest of the time yelling about how much he wants to bang his house. It’s like if the character of Danny Tanner magically came to life on Christmas, heard the Full House theme song, decided it wasn’t cheesy enough and wrote a new one.

It’s pretty catchy before the bridge, though.

“House Full of Love:” 6/10

0 notes

Text

The McDonald Christmas Review, Part 15

youtube

“It Takes a Miracle” In the Spirit (2001)

You know, I actually really like Steely Dan. This isn’t some confessional, explaining why I adopted this whale of a project, it’s just a true thing about me. I think Gaucho is my favorite album of all time. I’m honestly, genuinely surprised by how little I like the stuff I’ve heard over the past 15 days.

This is the first time during this whole damn process I’ve heard anything that even remotely reminds me of Steely Dan, and as you might imagine, I actually like it. It’s still inane, repetitive, and tortuously dragged out, but I’m not asking for a miracle here.

heh.

Look, if you find yourself in a bizarre situation where you need to listen to a single Michael McDonald Christmas song in order to survive some madman’s death trap you could do worse than 2001′s It Takes a Miracle. I can’t imagine such a situation, but honestly now that I’m thinking about it it’s probably the most logical way you might stumble upon this blog in the first place. If you are in some sort of McDonald-themed murder machine, I’d love to help in some way. Maybe comment down at the bottom of this post? Something like “help?” I don’t know. Whatever works.

“It Takes a Miracle:” 8/10

0 notes

Text

The McDonald Christmas Review, Part 14

youtube

“Wexford Carol,” This Christmas (2009)

Folks, I’ll be honest with you. I’m getting a little worried about this whole thing. The well’s starting to dry up. My well, and McDonald’s.

For one, I’m running out of ways to say that Michael McDonald sucks ass, and I have to imagine you’re sick of hearing how much ass he’s managed to suck over the 20 plus years of his illustrious career.

And furthermore, McDonald’s running out of material, and now I’m reviewing some shit called “Wexford Carol.” I mean...this seems like he made it up. Not like, that he wrote it, but that he actually sneezed or something and decided that sound was good enough for a title.

It sounds like a Christmas carol from something like The Dark Crystal or Labyrinth, and I know that sounds sort of rad on paper, but please believe me when I say it isn’t.

Look, the fiddle is a delicate instrument, and it demands a certain amount of respect when you’re bold enough to try and implement it in your music. You can’t just run around, willy-nilly, fiddling away like it’s nobody’s business. You have to earn the right to fiddle, or else it sounds like Mr. Grasshopper’s Wild Barn Dance, a concept that I think I just made up based on the sound of this song.

We’re at the middle, McDonald. Seventh inning stretch. Which one of us will give out first?

“Wexford Carol:” 4/10

0 notes

Text

The McDonald Christmas Review, Part 13

youtube

“On This Night” This Christmas (2009)

I’m gonna be brief with this today. I have a lot of things to get done today and none of them involve Michael McDonald and his dulcet tones.