Text

summer belongs more to yesterday than now. in its light, first love sleeps in sorrow.

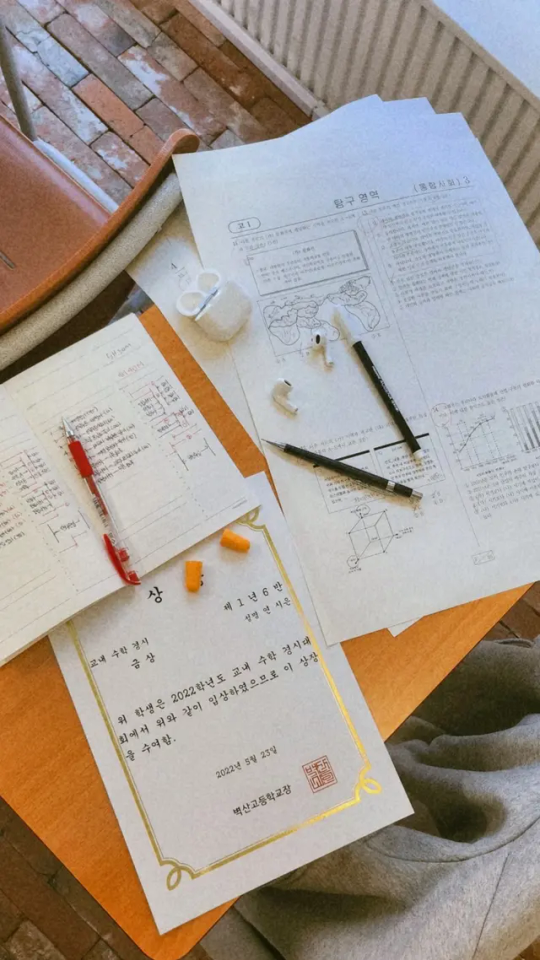

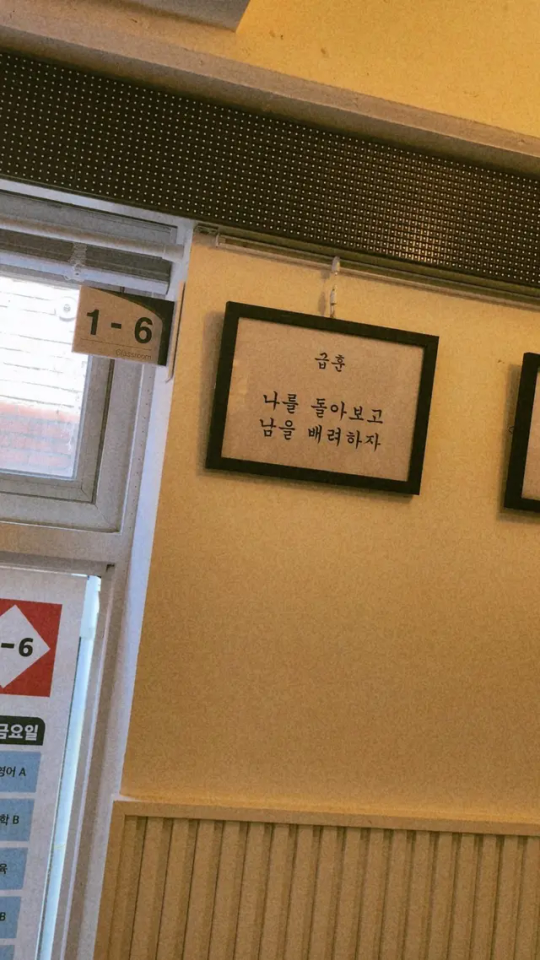

[pictures were taken at 2025 Weak Hero Class Cafe Event <First Love Counter Attack>]

#feel free to use the pictures for yourself if you'd like but kindly don't repost.#there is something else i want to post but... perhaps later.#oh and the terrible two lines in the description are from my old even more terrible poem...#just had to replace spring with summerㅋㅎ#weak hero class#whc#whc1#whc2#weak hero class 1#weak hero class 2#weak hero webtoon#yeon sieun#ahn suho#shse#suho x sieun#weak hero class one#weak hero class two

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suho asks Sieun, “Have you been living well?” Those words, once a last greeting, became a greeting of the beginning again. – from 『Next Actor Choi Hyunwook』

U: Sitting in a wheelchair, he only says three lines. Though short, I thought they were so inherently Suho.

S: As an actor, it’s been three years since he played Ahn Suho. Maybe that’s why he came to the set with much more pressure and worry than I expected. The script, too, had only three lines, but the actual dialogue was different. In the script, it was written as “Have you been well(잘 지냈냐)?” but Hyunwook changed it to “Have you been living well(잘 살았냐)?”. I only noticed the difference during editing. That was Suho’s first line during the last time he went to Sieun’s house in Class 1, and I realized the actor changed it to reflect that connection.

The middle line, “Who are those people in the back(저기 뒤에 분들은 누구셔)?” stayed the same. But Hyunwook said that line didn’t feel right in his mouth, so after a couple of takes, we cut it on set. However, we wanted to keep the intention, so we ended up restoring it during editing. To be honest, in Suho’s eyes, he probably couldn’t even see who was in the back. He was only looking at Yeon Sieun. Maybe Hyunwook wanted to cut that line because suddenly shifting his gaze away from Sieun to someone else felt too difficult?

The next line was, “Our Sieun has grown up, made friends too(우리 시은이 다 컸네, 친구도 생기고),” but Hyunwook condensed it into “It is good to see(보기 좋네).” Looking back, if we’d kept the original, it would’ve felt too contrived and overly explanatory of the director’s intent. So, Choi Hyunwook… he’s really something, isn’t he?

They fall into the same sleep. During the seasons when the Catcher* was gone, the children fell, got hurt, and rose again. Sieun, now the Catcher of the new friends, comes to find an old friend who has finally awakened from sleep. Suho asks Sieun, “Have you been living well?” Those words, once a last greeting, became a greeting of the beginning again.

*translating 파수꾼 (Watchman, Guardian, Sentinel) as the Catcher to keep the reference to The Catcher in the Rye in tact.

#ha.............................................................#i am truly glad the director allowed the actors such freedom of expression....#also i have never seen whc in english and i am not sure these is how the lines were translated into english but i translated them in a way.#that would show the subtle differences/nuances the actor has woven into them...#and.... we need more of such commentary please.......................#let us look into the hearts of these characters as much as possible please...#weak hero class#whc#weak hero class 1#weak hero class 2#weak hero class one#weak hero class two#ahn suho#yeon sieun#shsn#suho x sieun#t: weak hero#choi hyun wook#choi hyunwook

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gojo before his enrollment in Jujutsu Technical College The coming-of-age ceremony for Gojo Satoru, held by the Gojo clan: Gojo Satoru, somewhat forcefully, decided to leave the Gojo clan to attend the Jujutsu Technical College. At that time, to ensure that (at least) the Zenin clan, the Kamo clan, and the Jujutsu Headquarters would not misunderstand the Gojo clan and Gojo Satoru as being in conflict, the clan set the condition that he undergo the coming-of-age ceremony before enrolling, and he accepted.

Akutami Gege gave us a deeper look into the dynamics within the Gojo clan, as well as the political and social dynamics of the influential groups within the Jujutsu world, with a single sketch, so here is a bit of my (unorganized) thoughts.

The main purpose of holding Genpuku (元服: a traditional coming-of-age ritual, marking a person’s transition from childhood to adulthood and their formal assumption of responsibilities within their family or social role) was to publicly affirm Satoru’s allegiance to the clan before he entered the Jujutsu Technical College, where he would have to directly interact with other clans and the Jujutsu Headquarters. The clan was sending a political signal that, despite leaving for the college, it was not an act of rebellion but a sanctioned move, and that Satoru remained tied to the Gojo clan’s values and authority.

At the same time, it was the clan utilizing his status (being feared and perceived as powerful even at a young age). The Genpuku ceremony served to formally establish his status as an adult and a key figure within the Gojo clan before he fully entered the Jujutsu society. This move would ensure that other clans or the Jujutsu Headquarters viewed him as a representative of the Gojo clan rather than an independent actor.

For Satoru on the other hand, his compliance with the ceremony shows both his desire for independence and his understanding of the political necessity of maintaining appearances within the Jujutsu order. Being tied to the influence and power held by the Gojo clan would allow him to create freedom for himself within the system that he otherwise would not have if he were to outright reject the clan. In this sense, his enrollment was a step toward establishing his own identity, separate from but still connected to his family name. It would allow him to grow on his own terms. His willingness to meet the clan’s condition was not a sign of submission but of strategy. He accepted the ceremonial obligation in order to secure the freedom to operate in a larger sphere of independence.

#(ignoring nayoa there.....)#(forcefully is not really the right word but could not think of a better english language match. it is 억지로 in korean...)#ha............ of course i never know if i am making any sense...#and it has been ages since i have given my thoughts on anything here but this is me trying to step back into the fandom spaces.#hope someone finds an interesting bit and expands on it better than me.#jjk#jujutsu kaisen#gojo satoru#satoru gojo#jjk satoru#gojo clan

777 notes

·

View notes

Text

satoru: can i take it for a spin? suguru: do you have a license? satoru: no, but it should be fine if it’s on private property. shoko: that’s fake information.

bit late but… a little on whether it’s okay to drive without a license on private property. according to japanese traffic law, driving without a license is prohibited even on private property, if there’s a basis to consider it a road or if people and vehicles objectively and repeatedly use it. because of this definition, places such as apartment parking lots are not allowed, but fields or farmlands are generally considered okay.

#he was probably used to doing whatever he wanted on the clan property.#i am back with sharing useless informationㅋㅎ#jjk#gojo satoru#geto suguru#shoko ieiri#jujutsu kaisen

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

awakening (camellia petals upon dream-beaten bones)

alternatively, Weak Hero (약한영웅) meets Light Shop (조명가게) meets Buddhist Mythology.

#t: awakening (camellia petals upon dream-beaten bones)#i was not planning onto writing a whc fic but... watched the new season and then rewatched season 1 over the public holidays...#and well... let's say it was a journey down to the high school memory lane.#still unsure if my writing style is the right fit for these characters but... i shall try to make it work.#weak hero class 1#weak hero class 2#weak hero webtoon#whc1#whc2#weak hero class#yeon sieun#ahn suho#suho x sieun#sieun x suho#shse#shse fic#why are there always so many tags......... and how can one know which one is actually used............

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

WEAK HERO CLASS 2 Episode 1

354 notes

·

View notes

Text

[포기 안 해!!!]

[タケミっち...?]

#stood there for a good thirty minutes.............................#someone needs to convince the production to sell these after the exhibition.......................................

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

[タケミっち...?]

#ha......................................................#guess who finally went to the tokyo revengers exhibition today...#i have had the ticket booked since march and the exhibition is not even far from my place but...#things have been [something] since last september...#but finally taking a break these public holidays...#i shall be catching up with everything i missed.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Foolish my heart,” Suguru wondered upon the lantern light, “Have you not learned not to equate a man to Deity?”

prologue of beneath the moon, before the temple steps is here.

alternatively: how the threads of a child’s fate weave the paths of the shaman and the clan heir together again.

#t: beneath the moon / before the temple steps.#i am writing again.#it feels a bit awkward to write in english after so long but...#i hope i will slowly get used to it.#jjk#jjk fic#gojo satoru#geto suguru#getou suguru#stsg#sgst#satosugu#sugusato#fushiguro megumi#satoru gojo#suguru geto#megumi fushiguro#stsg fic#how does one know which tag is actually usedㅜㅜ

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In dreams, awakened from dreams, captured by the thoughts of the same bird.

“I have already accepted my Deity,” he found himself murmuring into the wind, musing gaze parting from the bed of flowers to observe the night. “So, why do you insist on haunting me?””

a glimpse into beneath the moon, before the temple steps.

alternatively: how the threads of a child’s fate weave the paths of the shaman and the clan heir together again.

#did not think i would be writing about these three again (or writing at all) but...#i could not not write a shaman suguru fic in the end.#and there is so long i could go without weaving poems in satoru's name it turns out...#and megumi... megumi is always the dearest part of my stories and this one is no different.#stsg#geto suguru#gojo satoru#jjk fanfic#stsg fanfic#suguru geto#satoru gojo#sgst

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there! I just wanted to say how much I treasure your fics. I’ve been reading them since early 2024 and they haven’t left my mind or my heart since :) I find myself returning to them frequently, and every time I reread I discover something new to adore about them. they are very precious to me, and I would like you to know how wonderful your writing is and how much I utterly treasure it! You are a fantastic writer. I hope your days are filled with joy and light. Thank you for writing ❤️

i have just realised that this kind message has been in my inbox since february.

i do not know if the author will see the reponse this late, but i apologise for taking this long to reply, and i want to thank you for giving time to my writing.

today was the first time i actually felt confident enough to think about posting another fic, and finding this message felt like the reassurance i needed to finish the prologue i have been putting off for months.

i cannot know what is it that made my fics precious to you, but it means a lot to me as a writer to know something about them stayed with another person enough to make them revisit those brief journeys. i hope you were able to take some comfort away from them.

thank you so much for reading my fics, and for your kind words. i will hold them dear.

and i, too, hope your days are filled with kindness and peace.

#it is a precious feeling to know my stories are loved.#thank you for reminding me of that.#today another person also left comments on the moonlight and... it made me realise how much i have missed writing.#i might post a new fic tomorrow... the idea has been with me for so long and i finally found the courage today.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Itafushi, or from darkness to light:

[continued from this post]

Megumi’s birthday is on Winter Solstice (usually December 21 or 22), the darkest day of the year. It is a day associated with 사유(死有) in Buddhism, which is the moment of death. Since Buddhists recognise that there is a continuous cycle of life, death and rebirth, in the moment of death, after the last breath is taken the individual is in an intermediate state between their previous life and their new life. Winter Solstice is seen as the message of the darkness, but it is also perceived as a messenger of Enlightenment, or to put it in another way, the promise of the return of the light as it is when things are at their darkest that the light is about to return.

On the other hand, Spring Equinox (usually March 21) represents new light and life and can be associated with 생유(生有) in Buddhism, which is the moment of birth. In Japan, Buddhist Temples perform the Higan-e Ceremony on this day. The word ‘higan’ is a translation of the Sanskrit word ‘paramita’ and it means ‘arriving on the other shore’. It signifies ‘getting across’. Buddhism teaches that the world in which we live, called the impure world (literally: ‘realm of endurance’), is a place of suffering. In this schema, the impure world is located on this side of the shore. The source of all suffering (the three paths of earthly desires, karma and suffering) is likened to a great river and the life condition of Enlightenment is likened to the other shore. We must cross the river to reach the pure land on that side of the shore.

From this perspective, Megumi and Yuuji are the end and the beginning of this continuous cycle.

#and we have ‘arrived on the other shore’...#happy birthday‚ spring’s first sunlight!#(unfortunately i do not have anything special to share on yuuji’s birthday either)#(i was sort of not expecting to make it three months into 2025ㅋㅎ)

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

➠ Symbolism of Yuuji’s childhood memories in Chapter 265 and how it connects to his conversation with Sukuna:

I was rereading the latest chapter and ended up dwelling on how the order in which certain things appear along the path Yuuji and Sukuna are walking connects with the progression of their conversation and the outcome of it, so I want to point out a few of such details in case someone else finds it interesting.

First, I will start with Morning Glory (asagao, 朝顔, lit. morning face) Yuuji mistakes Ajisai for. Asagao was brought to Japan with the advent of Buddhism and came to represent Enlightenment. When one thinks of the flower, an old line often comes to mind: [Asagao blossoms and fades quickly to prepare for tomorrow’s glory]. It is the theme of one of the oldest songs on the morning glory, written by the Chinese priest at the temple of Obaku near Uji, who is said to have been the first person to introduce the flower to Japan. Since its arrival, it has been a frequent theme in Japanese Buddhist poetry, particularly when writing on the fleeting condition of human lives, as the poets found a congenial subject in the morning glory, for they considered no flower has a briefer life and beauty, and the buds of yesterday are flowers to-day, but only for a few short hours, and then nothing will be left but ruin and decay; though how quickly fresh buds will appear and fresh flowers open to be the tomorrow’s ‘morning glory’. Therefore, in Japanese culture, asagao is a symbol of new beginnings. The flowers open in the morning, representing the dawn of a new day, and close in the evening, symbolising the end of the day and the passing of time.

Next comes Ajisai (紫陽花), the Japanese hydrangea. The flower has both positive and negative connotations in Japanese tradition, symbolising both deep or heartfelt emotion and also a fickle or changeable heart. However, I mentioned in this post that the blue hydrangea (I am assuming blue, because Yuuji mistook it for asagao) can mean sincerity, forgiveness, remorse and spirituality. Ajisai are also an important part of the ceremony in celebration of Buddha’s birthday (Kambutsue), where his statue is washed with sweet hydrangea tea by the visitors of the temples. As such they are often found at shrines and temples.

After that, Yuuji and Sukuna catch Crayfish. Interestingly, Buddhist philosophy references the crayfish when speaking about the temporary nature of existence. All that seems solid and permanent, like the crayfish shell, eventually disappears. There is a famous painting of Priest Xianzi (Japanese: Kensu) by Unkoku Tōgan from the Momoyama period. It depicts a seated figure of a Buddhist monk who appears to be contemplating the large crayfish (or shrimp). Kensu or Xianzi is a semi-legendary eccentric priest of the Tang dynasty, who spent much of his time wandering along riverbanks, eating crayfish and clams. He allegedly achieved Enlightenment while catching a crayfish.

Later they come across Horses, which hold a special place in Buddhism, embodying spiritual virtues and the timeless quest for Enlightenment. The story of Siddharta Gautama Buddha’s renunciation and his separation from his beloved horse, Kanthaka, is a significant story in Buddhism. As Siddharta decided to leave behind his life of luxury and embark on a spiritual journey, he faced the task of saying goodbye to his beloved horse. The separation from Kanthaka symbolises the profound sacrifice he took when he renounced worldly attachments in the pursuit of Enlightenment. Additionally, in the Shamanistic tradition of East Asia and Central Asia, there is a concept of the Wind Horse, a flying horse that is the symbol of the human soul. In Tibetan Buddhism, it was included as the pivotal element in the centre of the four animals symbolising the cardinal directions.

After the horses, we see them engage in Archery. As a Buddhist symbol, the bow and arrow are found throughout the art, mythology and theology; held by gods, part of vivid legends, lauded in sacred texts and painted on the walls of the temple fortresses. They are symbols of the wisdom and compassion of the Buddha. Just as the arrow flies straight to its target, so too must the mind of the archer be focused and free from distractions.

And lastly, Snow. As a symbol of purity, it is taken as representative of naive innocence behind heroic undertakings. In this regard, it is also a subject of paintings in special combination with cherry blossoms as a symbol of what is ephemeral and transitional as is the life of the hero. However, snow is often associated in the Japanese short poetry with the Zen notion of Emptiness. This is because, to quote the poet Naitō Jōsō, snow covers and clears everything: [fields and mountains / all taken by snow / nothing remains]. From the lens of Buddhism, as the defilements—greed, hatred, and delusion—melt away like snow, the process of purification speeds up our relinquishment of impurity. To do this, one needs to be able to feel their humanity from within, where the invisible factors of mindfulness, clarity, faith, energy, concentration, and wisdom can dismantle and dissolve years of deluded ways of perception, of relating to life. Only then will the ground of awakening begin to appear.

I find Yuuji’s conversation with Sukuna to be rich in symbolism, each element along their path reflecting deeper themes of compassion and Enlightenment. Their journey begins with the morning glory, symbolising a new beginning and Yuuji’s offer of redemption to Sukuna. The hydrangeas, mistakenly identified as morning glories by him, signify Yuuji’s readiness and offer of remorse as he sincerely reminisces on his childhood with him. The appearance of the crayfish continues this theme, highlighting that this conversation is a chance for Sukuna to contemplate the temporary nature of existence and the path he wants to continue leading from there on. The horses, embodying spiritual virtues and the timeless quest for Enlightenment, appear as Yuuji’s way of asking him to renounce his old ways in pursuit of Enlightenment, followed by Archery right after, emphasising his readiness for compassion despite all Sukuna has done to him, mirroring the Buddhist ideal of a concentrated, undistracted mind. And lastly, comes snow as a symbol of purity and the potential for redemption, evoking the Zen notion of emptiness and the purification of defilements. Yuuji, by invoking these symbols, offers Sukuna the last chance at redemption and Enlightenment. He shows Sukuna the final act of compassion if Sukuna shows remorse, which Sukuna refuses.

In the end, Yuuji and Sukuna walk the same path, but their choices lead them in opposite directions. Yuuji embraces the symbols of Enlightenment, striving for a higher understanding and compassion, whereas Sukuna rejects these ideals, choosing instead to renounce the path to Enlightenment.

#how beautiful that it snowed in kitakami on yuuji’s birthday.#reminded me of chapter 265 that took place in kitakami as well.

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

it is december,

misted with the memory of loss.

sleeves still wet with your name,

i go hunting bluebirds in the snow.

since i was translating my old poem for the next chapter of turning pages (the narrow road to the deep north).

#coming by to share at least a few bad lines to mark the date.#why bluebirds?#in japanese folklore they are harbingers of joy and fulfilment but in Chinese culture they are a symbol of love and fidelity.#and in korean culture they are considered the harbingers of hopeful news especially those of a beloved.#additionally they are associated with yearning lovers and seeing a bluebird is considered a sign that someone you love is thinking of you.#so the bluebird can be interpreted in many different ways.#those who have read my satosugu fic 'bluebird spread your wings' would probably remember.#i miss writing...................#but duties call first...........#perhaps... if i live long enough to see the springtime...............

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Teaser visual for Jujutsu Kaisen: Culling Game anime.

I can no longer stay with everyone.

#t: a parting word? the sun in winter is fleeting.#(where is the golden dream of youth?)#t: yuuji#this visual dragged me out of the darkness.........

615 notes

·

View notes

Text

since i do not have anything special to share for megumi’s birthday, here is this bit from chapter three of turning pages (the narrow road to the deep north).

Itafushi, or from darkness to light:

[continued from this post]

Megumi’s birthday is on Winter Solstice (usually December 21 or 22), the darkest day of the year. It is a day associated with 사유(死有) in Buddhism, which is the moment of death. Since Buddhists recognise that there is a continuous cycle of life, death and rebirth, in the moment of death, after the last breath is taken the individual is in an intermediate state between their previous life and their new life. Winter Solstice is seen as the message of the darkness, but it is also perceived as a messenger of Enlightenment, or to put it in another way, the promise of the return of the light as it is when things are at their darkest that the light is about to return.

On the other hand, Spring Equinox (usually March 21) represents new light and life and can be associated with 생유(生有) in Buddhism, which is the moment of birth. In Japan, Buddhist Temples perform the Higan-e Ceremony on this day. The word ‘higan’ is a translation of the Sanskrit word ‘paramita’ and it means ‘arriving on the other shore’. It signifies ‘getting across’. Buddhism teaches that the world in which we live, called the impure world (literally: ‘realm of endurance’), is a place of suffering. In this schema, the impure world is located on this side of the shore. The source of all suffering (the three paths of earthly desires, karma and suffering) is likened to a great river and the life condition of Enlightenment is likened to the other shore. We must cross the river to reach the pure land on that side of the shore.

From this perspective, Megumi and Yuuji are the end and the beginning of this continuous cycle.

#crawling out of the darkness after months to leave a little happy birthday note for the little rising moon(light)...#also to say that i have heard the jjk news and i want to ask...#who reminded akutami gege about ozawa?ㅋㅎ#ozawa of all people...................#but at least we will be getting something new on uraume... so there is that...#t: turning pages (the narrow road to the deep north)#ah... i do miss writing... it has been months since i have written something........................#perhaps soon...#i do have a few stories outlined but...#hi~ if someone actually makes it to here.#i am pleasantly surprised there are still people following me.#and i hope everyone has had better past few months than me.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

chapter 9 of turning pages (the narrow road to the deep north) is now here.

a line to commemorate bluebird, spread your wings (here’s a piece of the broken dream) reaching 500 kudos and turning pages (the narrow road to the deep north) ending on sept. 30.

#only the epilogue left now.#which will be posted on the day of jjk's ending.#it has been a journey and i hope everyone who joined it along the way enjoyed it.#t: turning pages (the narrow road to the deep north)

87 notes

·

View notes