Text

The law in question, which was signed by governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders on March 31 and is set to take effect on August 1, removes an exemption from prosecution for school and public libraries and would empower virtually anyone to challenge the appropriateness of library materials in Arkansas. Library staff found to have “knowingly” distributed or facilitating the distribution of allegedly obscene material to a minor—defined as anyone under 18—would be open to a potential felony charge.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

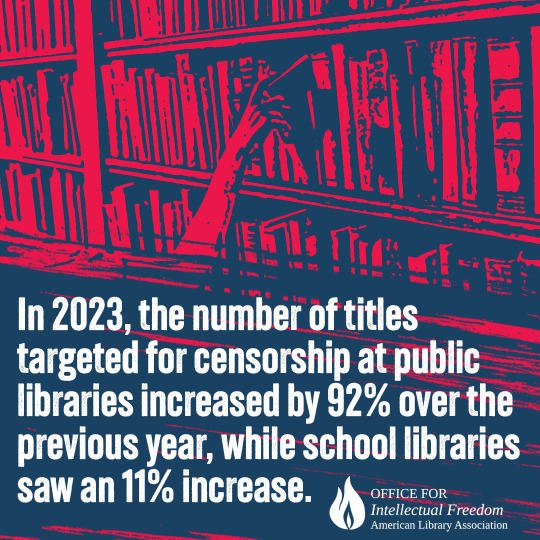

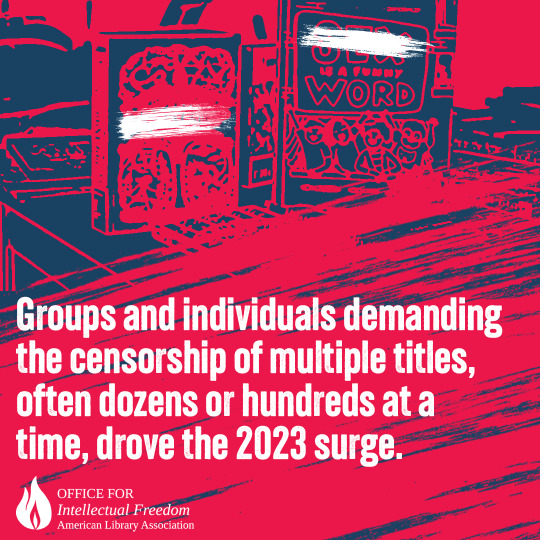

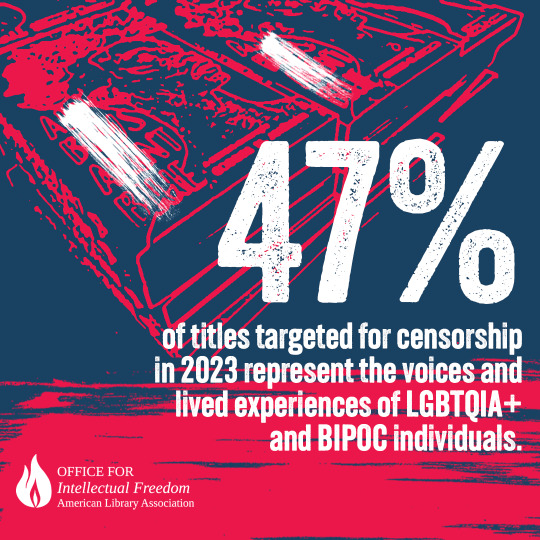

The ALA's State of America's Libraries Report for 2024 is out now.

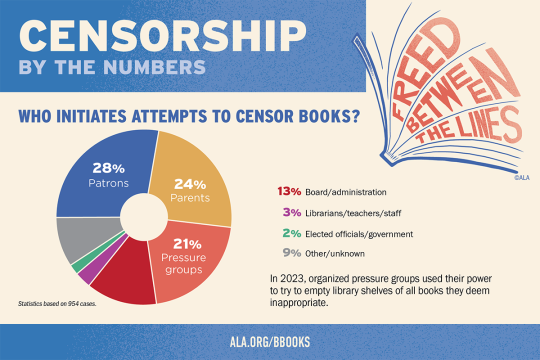

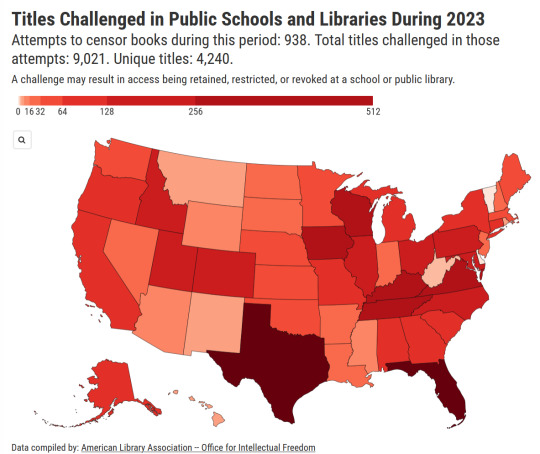

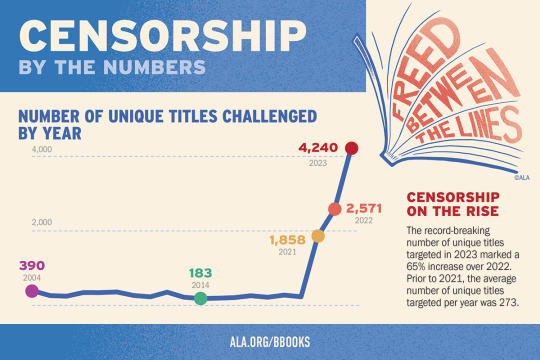

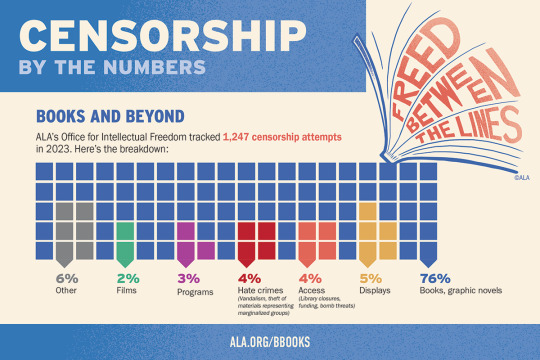

2023 had the highest number of challenged book titles ever documented by the ALA.

You can view the full PDF of the report here. Book ban/challenge data broken down by state can be found here.

If you can, try to keep an eye on your local libraries, especially school and public libraries. If book/program challenges or attacks on library staff are happening in your area, make your voice heard -- show up at school board meetings, county commissioner meetings, town halls, etc. Counterprotest. Write messages of support on social media or in your local papers. Show support for staff in-person. Tell others about the value of libraries.

Get a library card if you haven't yet -- if you're not a regular user, chances are you might not know what all your library offers. I'm talking video games, makerspaces (3D printers, digital art software, recording equipment, VR, etc.), streaming services, meeting spaces, free demonstrations and programs (often with any necessary materials provided at no cost!), mobile WiFi hotspots, Library of Things collections, database subscriptions, genealogy resources, and so on. A lot of electronic resources like ebooks, databases, and streaming services you can access off-site as long as you have a (again: free!!!) library card. There may even be services like homebound delivery for people who can't physically come to the library.

Also try to stay up to date on pending legislation in your state -- right now there's a ton of proposed legislation that will harm libraries, but there are also bills that aim to protect libraries, librarians, teachers, and intellectual freedom. It's just as important to let your representatives know that you support pro-library/anti-censorship legislation as it is to let them know that you oppose anti-library/pro-censorship legislation.

Unfortunately, someone being a library user or seeing value in the work that libraries do does not guarantee that they will support libraries at the ballot. One of the biggest predictors for whether libraries stay funded is not the quantity or quality of the services, programs, and materials it offers, but voter support. Make sure your representatives and local politicians know your stance and that their actions toward libraries will affect your vote.

Here are some resources for staying updated:

If you're interested in library advocacy and staying up to date with the challenges libraries are facing in the U.S., check out EveryLibrary, which focuses on building voter support for libraries.

Book Riot has regular articles on censorship attempts taking place throughout the nation, which can be found here, as well as a Literary Activism Newsletter.

The American Library Association's Office for Intellectual Freedom focuses on the intellectual freedom component of the Library Bill of Rights, tracks censorship attempts throughout each year, and provides training, support, and education about intellectual freedom to library staff and the public.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation focuses on intellectual freedom in the digital world, including fighting online censorship and illegal surveillance.

I know this post is long, but please spread the word. Libraries need your support now more than ever.

163 notes

·

View notes

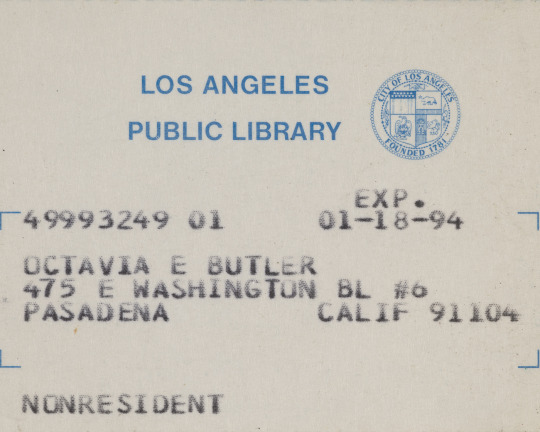

Photo

Octavia E. Butler’s library card for the Los Angeles Public Library, Los Angeles, CA [from the Octavia E. Butler Papers], in Aida Ylanan and Casey Miller, The literary life of Octavia E. Butler. How local libraries shaped a sci-fi legend, «Los Angeles Times», November 18, 2020 [The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CA. © Estate of Octavia E. Butler]

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally, it is necessary to reconsider the use of the MLS as a gatekeeper to the profession as it works to suppress BIPOC availability to serve in libraries. We want to diversify our ranks, but we cannot MLS our way out of our diversity problems. There are conflicting priorities—the need to diversify our libraries and our seeming inability to accept anything other than the MLS degree as the entry point for the rewards and riches of a fully realized career working in a library.

Curtis Kendrick

References

Kendrick, C. (2023). Changing the racial demographics of librarians. Ithaka S+R. https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.318717

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Separate But Equal: Discussions on the Graduate Level Library Science Degree

As someone who is currently enrolled in an ALA-accredited Library Science and Information program, I can say with full confidence that if the degree was not required in order for me to become a librarian, I would not be here.

A little information about me: I’ve worked in a public library for almost four years, I have an undergraduate degree in Book Studies & Multicultural Literature, and within the last few weeks I have not only been automatically disqualified for a Librarian I position because I didn’t have the library specific degree—I have also been told by both my Circulation Services Manager AND my Library Director that they feel I am qualified to be a Librarian or Library Specialist.

You might be asking then, why I would bother with the degree if I’ve been told by the powers that be that I am qualified and well, it’s because qualified or not due to how the classifications are written, I would either need sixyears of work experience in a library setting or the degree…with no experience required at all.

Personally, it’s quite a frustrating predicament to be in but objectively, I think that it highlights the innate inequity and inaccessibility that the requirement of a graduate degree creates, specifically for people of color like myself.

Cheryl Knott, author of Not Free, Not For All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow, argued that requiring advanced degrees or certifications as an entry point to librarianship is a direct consequence of racist policies that were in play when public libraries were being established at a national level. Noting that due to this requirement (as well as other laws at the time) aspiring Black library professionals who were either not allowed to participate in or simply have access to any level of education, would automatically be considered less capable of performing in their role and therefore relegated to positions in the library that weren’t patron-facing and didn’t allow any meaningful authority. Conversely, she also noted that when aspiring Black professionals would push back against such policies and attempt to gain hands-on experience they were still considered to be less qualified.

Melanie Higgins, Executive Director of the Richland Libraries, stated that removing the M.L.S. / M.L.I.S. requirement was one of the best decisions she ever made, arguing that, “Having an MLIS degree or even prior public library experience doesn’t automatically ensure [having the knowledge to manage a library].” Additionally, when this requirement was removed, the Richland Libraries went from having one branch manager of color to seven—and while there may be a lot of varying and competing factors for why this might have been, it cannot be denied that it might have been a natural consequence of requiring an advanced degree as an entry-level point to the profession when an overwhelming percentage of those holding the degree are white. (Huggins, 2022)

Again, speaking personally, not only have I been told by my Circulation Services Manager and Library Director that I’m qualified to be a Specialist or Librarian; I have also been actively discouraged by people within my library system from getting the degree because the perception is that it is a “waste.” Waste of money and waste of time, because—as I’m always told—“you can just work your way up and chose to either be a S.L.A. (Supervising Library Assistant) or a Specialist and make the same amount of money.” Which is another piece of the library profession puzzle that is often ignored—in a society that is rapidly demanding more and more education from potential job candidates, the library has a very wide entry point.

I cannot speak to libraries in different locations, but within the San Francisco-Bay Area, almost every library system offers the opportunity to a) join employee-protected, union-backed work and b) climb a clearly defined career ladder. While the position titles may change depending on where you are, every library has the equivalent to a Page or an Aide where the only skills you need to be successful is the ability to count and know your alphabet. Everything else—sorting, shifting, shelving, the computer systems—can be taught on the job. It is only for the classification and specific job title of “Librarian” that the degree becomes a factor, which in my opinion constitutes institutional and organizational gatekeeping. Moreover, there is a lot of evidence that points to the M.L.S. / M.L.I.S. requirement being a holdover from Jim Crow era policies that were designed to keep libraries open to some and not to all.

References

Knott, C. (2015). Not free, not for all: Public libraries in the age of Jim Crow. University of Massachusetts Press.

Huggins, M. (2022). MLIS required? rethinking the skills and knowledge necessary for managing in a public library. Journal of Library Administration, 62(6), 840–846. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2022.2102384

#information professions#public library#library#libraries#library science#library information and science#graduate school#mlis#mls

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Libraries That Made Me | Diamond Branch Library

As an elementary school child, I can count the amount of times that I went to the Diamond Branch Library on my hand. It was a little out of the way, it had a very small parking lot, and frankly, I don’t think there was any perceived reason to go to this particular branch when Eastmont was in walking distance.

Whatever the case, what few times I went to Diamond certainly stuck with me because as I entered my teenage years, I would often catch the bus just to come and sit and read for a couple of hours. In all honesty, I might have just liked the branch because going so far away made me feel more “independent”—of this, I can never be sure—however, what I do know is that because I had to get to this branch of my own accord, it became sort of like a dock for all my teenage activities. Diamond Library is up the street from Diamond Park, so when I would go on dates at the time I would stop by the library to check out books and then we’d sit on the grass and read together. Eventually, when we had a child, we’d take our son to this branch and do the very same thing—check out books, walk up the street to the park, sit on the grass and read. This was even the place where my son eagerly got his first library card.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Not Free, Not For All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow

Not Free, Not For All, was a book I elected to read as an aspiring information professional who just happens to be a Black woman. I knew that I needed a reality check and I wanted to challenge myself.

Speaking personally now, I’ve gone the entirety of my life knowing to some extent about the history of segregation, slavery, and racism; I also knew that I, as a Black person, was at one point now allowed in certain places. As you might be able to imagine, once it clicked in my head that the library was also a place that would have denied my entry because I was Black was a devastating blow. In fact it was almost enough to make me give up the dream of working in the library profession all together, because it almost felt like I had been lied to about this place I loved so much.

Going back to the book, I recommend it as essential reading for all aspiring information professionals because it helps to redefine what an individual’s understanding of “access” is within the context of racism. Beginning with the dissection of the given history of the library, the author quickly goes into the history that is more hidden from view, laying the foundation for the argument that “free access” was never about open shelf policies, but rather the historical policy and practice of allowing open access to some patrons and actively and explicitly restricting the access of others.

In reviewing this text, I realize that there is far too much material for me to analyze here, but I would be remiss if I didn’t run down a short list of topics she covered, which includes:

Policies that forced Black communities to create their own libraries with very little funding.

Policies that kept Black readers out of libraries and Black professionals out of positions of power within libraries.

Policies that turned intellectual freedom into a white privilege.

Contradicting uses for the library, which meant intellectual spaces cultivated by white women and social welfare and educational spaces created by Black women.

How white women feminized the library space and profession (this is more linked to low literacy rates in Black men as opposed to librarianship)

Censorship of culturally relevant materials to Black patrons by white library professionals.

In summary, this book truly attempts to tackle the issue of how white supremacy and racist policies played a role in the development of libraries and is essential to understanding how the library has the power to either transform or hinder the communities that they are placed in, because it’s not enough for a library collection to be representative—there is the additional issue of the community who is being represented having access to that representation. (From this book I learned that W.E.B. Du Bois was not allowed to step into a library that had books he had written himself in its collection.)

Quotes to chew on:

“As ‘universities of the people,’ public libraries helped create an African American identity, asserting individual's’ capacity for intellectual labor in an era when the value of a liberal education for blacks remained a topic for debate. Libraries provided access points for black literacy and intellectualism, confirmation that African Americans were reading, reflecting , striving human beings.”

“‘Experience seems to show that [an] adult Negro waits for tangible proofs of the library’s willingness to extend full privileges to him before he takes advantage of it’s service, then he responds to the library service and needs more of it than the library can give….Time is ripe for development of library services for Negroes, but it must not be patronizing or partially informed.’”

“Public libraries designated for the exclusive use of African Americans clearly participated in the construction of blackness. Less obviously, public libraries in general helped define whiteness. On one hand was the public library, with it unannounced restriction on access; on the other was the Negro library, with it’s label of difference sometimes carved into its facade.”

“The U.S. public library was one of many institutions upholding the systemic racism that enabled white supremacy...it is fantasy to believe that the public library was one of the few institutions not implicated in a system of racism or that separated public libraries for African Americans were just an unfortunate exception to the public library’s true democratic nature.”

“More significantly, literary societies gave African Americans an opportunity to position themselves as participants in rather than victims of a democratic experiment whose founding documents revered liberty but whose national economy increasingly depended on slavery.”

“Unlike the white General Federation of Women’s Clubs, the Nation Association of Colored Women did not declare the creation of public libraries a priority. Instead, clubs wove a commitment to books and reading into their social welfare programs and services. Most black clubwomen pursued self-improvement through reading and writing as well as community improvement in a variety of charitable events.”

“The racially restrictive admission policies of southern public libraries ensured that the new public spaces would not challenge white women’s sense of superiority and entitlement nor the white man's sense that white women needed protecting from a threat manufactured by white men themselves.”

“...he did not give away manhood so much as redefine it. Black manhood meant accepting a hard lot in life and making the best of it. In compensation, whites were to recognize what such men had given up and accept the conciliation it represented. Black men’s power lay in their capacity for work, not in their ability to organize and agitate.”

“For the most part, the new southern public libraries were free to all whites. Inequitable access did not disappear with the transformation of libraries from private to public; it merely shifted from an economics basis to a racial one. Inability to pay membership and use fees no longer precluded access to library collections and service. Race did instead.”

“Elizabeth McHenry’s interpretation of the benefits that accrued to members of black literary societies applies equally well to the users of black libraries. ‘The growing number of educated black men and women considered reading and other literary work as essentially to the project of refashioning the personal identity and reconstructing the public image of African Americans...although black women’s clubs were not exclusively literary in nature…a primary impact of the black women’s club movement was the increased production, circulation, and readership of printed texts.’”

“The library was organized around the needs and desires of individual readers. Once the librarian issued them borrowing cards...readers followed their own literary tastes, reading paces, and borrowing patterns. In contrast, literary societies were organized around regular meetings, often opened to non-members as well as members, which featured the public presentation of a paper written before the meeting and discussed during the session and even afterwards. Reading, writing, thinking, and talking were social activities with the potential for political outcomes.”

“A person ventured into the literary society meeting in search of spoken words but traveled to the library in search of printed words. The result at both venues could be a meeting of the minds, but at the library, that meeting was silent and invisible, occurring solely between reader and author.”

“Henry Gaill of New Orleans indicated that his library could not afford to send staff to a library school and their low salaries meant that they would not be able to afford such training themselves. Some respondents said that black librarians and assistant librarians had received training in the main library, apparently alongside whites, who were receiving apprenticeship-style practical instruction instead of attending library school.”

“Several of the librarians asserted that a library school for African Americans was need...If one of the functions of professional education was to socialize students into the customs and practices of the profession, then a southern library school for blacks would need to manage the expectations of students who, as public librarians, could expect to work part time at low pay with little support for collection building or outreach.”

“For the most part, African American library buildings were small, with inadequate collections and funding. Nevertheless, they were significant, both as physical places in the urban landscape and as symbolic spaces in the lives of local black communities.”

“The New South included racial segregation and gender-specific roles designed to create appropriate places for black men, black women, white women, and to keep those places separate from and subordinate to the place of white men.”

“The injection of Carnegie funds and the requisite annual city appropriation for maintenance might have fed into the black economy, providing design and construction projects for African American architects, engineers, contractors, and trades workers. Instead, local black professionals and skilled workers received little or no benefit from these important building projects in their neighborhoods.”

“Librarians generally seemed to think that they had a responsibility to help children develop the habit of reading, as long as it did not become an obsession, and the duty to lead children from the more sensational and unrealistic to the more refined...they also seemed to understand the need to nurture not only children’s intellectual development but also their emotional life and imagination.”

“African American readers were better served by library staff members who looked like them and who exuded helpfulness rather than hostility. Black librarians would create ‘an atmosphere where welcome and freedom are the predominant elements,’ Harris suggested, implying that white librarians were creating quite a different atmosphere when African Americans entered the building.”

“The library’s annual report for 1953 noted that, with one exception, all of the African American borrowers returned their books on time. Perhaps the librarian included this information because some white staff members had assumed that black readers would be irresponsible.”

“Bullock was exactly what late nineteenth-century opponents of education for African Americans had feared: a black person who was willing to speak out when treated unfairly, willing to demand the rights due to him as a citizen, a taxpayer, and a human being. He also represented what supporters of education and libraries claimed would happened when blacks were given the same opportunities as whites. They would form a class of hardworking, responsible citizens who paid their taxes and a market of consumers who would contribute to overall economic growth.”

References

Knott, C. (2015). Not free, not for all: Public libraries in the age of Jim Crow. University of Massachusetts Press.

#information professions#public library#libraries#library#public libraries#racism#jim crow#black librarians

0 notes

Text

The Underrepresented Native American Student: Diversity in Library Science

This is another article I discovered through the American Library Association and their “Diversity in the Workplace” page and it is also very short in length. Despite this, I have no choice but to recommend it to aspiring information professionals because it is one of the only pieces I was able to find in relation to Native Americans and libraries which says a lot about the issues of diversity and representation within the library profession. (Side note: from this article, I did learn the term “tribal libraries.” If you are interested in learning more about Native American libraries and librarianship, it’s likely a good search term to start with).

Something to note about this article however, is that unlike a lot of articles about the state of diversity in libraries, this one is solely focused on the failures of libraries—as a profession, organization, and institution—in addressing and serving the needs of Native Americans, and how their unique community experience sets them apart from other minority/ethnic groups.

Essentially, the author argues that as a direct result of European colonialism, larger percentages of Native Americans are trapped in cycles of poverty that inevitably effect their ability to be eligible to become librarians (that is, being in a cycle of poverty means that they have less access to resources that could help nurture and support academic development) and that the lack of Native American librarians strains the relationship between Native peoples and public libraries.

Tragically, Llyod points out that unlike with other underrepresented groups, few attempts have been made to make libraries culturally relevant to them—although I would like to offer that in recent years, much more effort has been put forth on the part of library organizations and professionals to develop programs, services, and collections that represent the Native/Indigenous community as well as acknowledging that such organizations exist on Native land and continue to benefit from colonialism and white supremacy.

Some quotes to chew on:

“There is a comfort in approaching someone who is of one’s own heritage when seeking services and that includes libraries. When people of color do not see themselves represented in libraries they may not approach the librarians. They may not even approach the library.”

“The library loses relevance for citizens who do not see themselves reflected, who do not perceive their heritage and values recognized and valued or their lifestyle understood by those on the other side of the desk.”

References

Llyod, M. (2007, February). The underrepresented native american student: diversity in library science. Library Student Journal, 2(1).

#information professions#public library#libraries#library#library advocacy#native americans#native american#diversity#librarianship

0 notes

Text

Chicano Librarianship

I discovered this article in the bibliography of another article called, “Diversity in the workplace,” that I was reading on the American Library Association’s website and the reason I chose to read it is because I realized that this was as close to “multiculturalism” as I was going to get. Unfortunately, due to the history of chattel slavery in the United States, issues of diversity can sometimes come down to Black and white (literally), which is why I wanted to ensure I included a text that showed a different perspective.

Though short in length, this article tackled issues of diversity, accessibility, and representation by speaking (from personal experience) about something called, “The Way Out Project,” wherein a federal grant was provided in order to create four Mexican American/Chicano libraries and seven African American libraries.

(Side note, after reading this article I could find little to no information about “The Way Out Project,” the closest I got was a book called Still Struggling for Equality: American Public Library Services with Minorities, published in 2004. This article was written in 2010 and Martinez ends by saying that she wished that more of the people involved had recorded their experiences with the project because it’s like it never existed to begin with. Which in my opinion is another whitewashing of library history.)

Being that it is about the author’s personal experiences, it is inherently less factual and data-driven in nature, however given how little information there seems to be about “The Way Out Project,” this testimony (I feel) is crucial to aspiring information professionals, looking to learn more about the history of public libraries as it pertains to people and communities of color. Martinez writes about how the grants enabled libraries to hire more Black and Chicano librarians as well as restock their collections with materials that these new librarians’ thought were beneficial to their patrons. She says that this was met with heavy opposition, disrespect, and outright disrespect which is unfortunately to be expected, however, what I’d like to call attention to is Martinez’s arguments and observations on how these librarians of color were using their newfound positions of power in order to transform their communities and change the perception of what librarians could and were allowed to be.

By Martinez’s account, these new librarians set out to be socially active—putting forth the idea of the library profession, building, and professionals not relegating themselves to being hoarders of information but agents of local culture and servers of their communities. Which isn’t to say that these librarians didn’t love books or intellectual endeavors; they just seemed to understand the underlying prejudices that were ingrained into the library as an organization and fought against it in order to be more accessible and inclusive. (Although as another side note, it is wild to me that even as they were attempting to make libraries more diverse and accessible to underrepresented communities, Mexican and Chicano librarians and patrons were forbidden from speaking Spanish within the library, which would make the library inaccessible to a number of patrons).

Some quotes to chew on:

“Our project consisted of a group of librarians from varied backgrounds, and we became advocates for the recruitment of Spanish-speaking, Mexican-American, and African-American librarians, as well as the addition of ethnic resources and collections, community-based programs, and ethnic library decor to establish presence and a welcoming environment for the community.”

“During the three years of ‘The Way Out Project,’ we consistently encountered opposition from library employees, were reprimanded for our decisions by administrators, or were ignored by colleagues for our activist librarian ways. The motivations for our decisions, the books we purchased, the programs we developed, and the meetings we attended were routinely scrutinized, questioned, and opposed by the majority of librarians.”

References

Martinez, E. (2010, November 1). Chicano librarianship. American Libraries Magazine, 41(November/December 2010), 40–43. Retrieved May 10, 2024, from https://web-p-ebscohost-com.libaccess.sjlibrary.org/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=bba370c6-536d-438a-a1d8-df92f8fa2d93%40redis.

#information professions#public library#libraries#library advocacy#public libraries#library#chicano#mexican#diversity

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Interlude

As a brief note here, there is another chapter in the book I just mentioned, titled, “‘An Association of Kindred Spirits’ : Black Readers and Their Reading Rooms," which I also highly recommend.

In this chapter, the contributions of Black librarians—whether they were recognized as such or not—are highlighted and painted as instrumental to ensuring that libraries are accessible, to preserving the histories—literary and otherwise—of minority groups, to becoming information anchors in their communities, and ensuring that the needs of their patrons were met.

It is so fascinating, however, I want to ensure I don’t just analyze one text, but there is my recommendation.

#information professions#public library#libraries#public libraries#black librarians#racism#black history

0 notes

Text

Institutions of Reading: the Social Life of Libraries in the United States (2007)

The chapter I’ve chosen to highlight from this book is titled, “The Library as a Place, Collection, or Service: Promoting Book Circulation in Durham, North Carolina, and the Book-of-the-Month Club, 1925 – 1945,” and was written by Janice Radway.

In it, Radway examines a twenty year period at a library system in Durham, North Carolina and how the information professionals in power at the organization, hadn’t considered (or cared, quite frankly) about the needs of patrons of color or their “colored” libraries.

I’d recommend this book, and this chapter in particular, to any aspiring information professional to challenge their current understanding of what the function of the library (or any information organization) is. Moreover, this author does a phenomenal job of questioning the authority of librarians, allowing readers to ponder—if the library is truly free (no cost) and accessible (no censorship as well as being physically present in communities) then what needs to be done to ensure that the professionals within that library (as individuals, not necessarily instruments of the government) are upholding those values?

Additionally, this chapter provides context on what caused the initial pivot in the public library’s positioning; as much like with children’s publishing and literature, libraries used to simply serve as collections of information rather than a service to the community. Which is to say, that very dated image of the library that lives on in the public conscious—the one where libraries are only for formal, educational, or informational purposes only—was at one point a reality and the reason we are where we are (with open access to whatever nonsensical, silly, fictional tales we want) is on part, due to the intervention of publishers.

Some quotes to chew on:

“When Harry Scherman set out to sell books by mail, he contested certain common assumptions of the publishing industry as well as the library profession about the nature of books and reading. At the same time, he challenged some of his culture’s most cherished assumptions about the special, transcendent qualities of literature and art. In doing both together, he threw together the weight of his organization behind the cause of the circulating book, that is, the desire to get more and different books to more and varied readers.”

“Even when librarians agreed that they had a duty to make books available to a larger and more diverse audience, they could not agree among themselves about what constituted ‘the best reading’ or who should determine its character. Although ALA members debated among themselves about what experts should be consulted, few thoughts patrons themselves should be left to pursue their own tastes or interests.”

“The fiction debates raged within the ALA for years because librarians worried that they were bringing patrons into their libraries who wanted only to read the most melodramatic and salacious fiction. They hoped that restrictive fiction circulation policies would prompt library-goers to turn to more serious reading material. At the turn of the century, though, even as the ALA recommended that only 15 percent of library’s collection should be devoted to fiction, most public libraries found that ‘fiction—especially popular fiction—averaged 75 percent of circulation.’ Library patrons apparently had their own ideas about what libraries were useful for and their own opinions about what books were pleasurable to read.”

References

Radway, J. (2007). The Library as a Place, Collection, or Service: Promoting Book Circulation in Durham, North Carolina, and the Book-of-the-Month Club, 1925 - 1945. In Institutions of Reading: the Social Life of Libraries in the United States (pp. 231–263). essay, University of Massachusetts Press.

#information professions#public library#library#libraries#books & libraries#books#publishing#diversity#jim crow#book of the month

0 notes

Text

Not Free, Not For All: A Retrospective on the Public Library’s Complicated History With Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Something that I feel is talked about—though not loud or often enough—is the complicated relationship between people of color who aspire to be librarians and the institution of the library itself; because while the library—as a concept, within the global public conscious, and as stated by in most mission/value statements—is an information organization that has always existed in order to make knowledge free and accessible, it is still—in many ways—an institution. And like most institutions that are supposed to provide a public service, it has also been utilized as a tool of the government to systematically deny and disenfranchise underrepresented, low-income, and minority communities.

This of course is a consequence of European colonialism and chattel slavery of Africans in the United States—a topic far too vast to cover here—but due to the fact that there were actually laws written denying enslaved people the right to learn how to read and write, in the development and funding of public libraries that took place at the start of the twentieth century, not only did libraries have an issue with representation and diversity in their available materials and collection policies, most people don’t realize (or remember) that for a very long time, in a lot of different places (not just the South) people of color weren’t even allowed to enter libraries or acquire a library card. (Pawley, 2022)

Now as a person of color—a Black woman—who has always loved reading, writing, and being in the library; when I learned that libraries were also used as instruments to uphold white supremacy I was incredibly distraught. Here I am, wanting to be a librarian—a qualified information professional serving my community in an information organization—and I have to shoulder the knowledge that at one point in history—not even that long ago (my mother was born the year Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and my grandmother was one of the millions of Black people who left the South during the Great Migration in hopes of finding more opportunity in California)—I not only couldn’t have been a librarian, I wouldn’t have been allowed in the building and I possibly wouldn’t have known how to read. Even more distressing? Just last year I discovered that in my own library system in my own progressive, Californian, Bay Area town, the first Black librarian wasn’t hired until the late 1960s. Which is insane.

This is about the time where one might wonder, well, if the library has a history of aiding the goals of racism and white supremacy, why would I—the self-proclaimed Black woman—still want to become a librarian (or information professional in general) at all?

And to that I say, being enslaved didn’t stop Frederick Douglass from wanting to read. It didn’t stop Benjamin Banneker from wanting to study and understand the stars. Sojourner Truth, W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Booker T. Washington, Carter G. Woodson—racism, discrimination, and for some of them, slavery, did not hinder the human desire to learn and grow intellectually. Moreover, the way I tend to look at it is that they, my mother, my grandmother, my great-grandmother and father didn’t face all that discrimination, or partake in all of those protests for me not to love literature, read every book I can, and desire to be a librarian. They lived, fought, and died so I could have these dreams—and because of that, as an aspiring librarian, I believe the best way to address the historical issues with the library as an organization and ensure that no person will ever have to endure those injustices again, is to both enter the profession myself and use my power within the profession to educate people on that history.

*Takes a big breath*

All of that context laid bare, the next few posts will feature brief annotations of books that can better help to shine light on the darker side of the public library’s history and to close out the discussion of diversity, equity, and inclusion we’ll double back to examine what some consider to be the last barrier to free and accessible librarianship—the M.L.I.S.

References

Pawley, C. (2022). History of Libraries, Information, and Communities. In Information services today : an introduction (Third edition., pp. 15–27). essay, Rowman & Littlefield.

0 notes

Text

youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Libraries That Made Me | Margaret K. Troke Branch Library

While the Troke Library isn’t the first library I ever stepped foot in, it was the first library I truly felt was my own. It was a library that I, like Matilda, grew up in. I remember being dropped off in younger elementary school (say third and fourth grade) and I would spend hours on the bright-colored carpet reading Powerpuff Girl and Scooby Doo chapter books; eventually I would be brave enough to venture into the adult and teen sections and discover authors like Sarah Mlyknowski, Meg Cabot, Melissa de la Cruz, and Terry McMillian.

I know many people wouldn’t think of the library as a place to blossom into tweenhood, but to me, the freedom I was offered by a library card—that freedom that allowed me to check out picture books, chapter books, romance novels, manga—whatever I wanted.

It was at this library that I truly learned what it meant to be an uncensored patron with access to the world.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fred Rogers Speech to the US Senate on Funding for PBS

[Senator Pastore]: Alright Rogers, you've got the floor.

[Mr. Rogers]: Senator Pastore, this is a philosophical statement and would take about ten minutes to read, so I'll not do that. One of the first things that a child learns in a healthy family is trust, and I trust what you have said that you will read this. It's very important to me. I care deeply about children.

[Senator Pastore]: Will it make you happy if you read it?

[Mr. Rogers]: I'd just like to talk about it, if it's alright. My first children's program was on WQED fifteen years ago, and its budget was $30. Now, with the help of the Sears-Roebuck Foundation and National Educational Television, as well as all of the affiliated stations -- each station pays to show our program. It's a unique kind of funding in educational television. With this help, now our program has a budget of $6000. It may sound like quite a difference, but $6000 pays for less than two minutes of cartoons. Two minutes of animated, what I sometimes say, bombardment. I'm very much concerned, as I know you are, about what's being delivered to our children in this country. And I've worked in the field of child development for six years now, trying to understand the inner needs of children. We deal with such things as -- as the inner drama of childhood. We don't have to bop somebody over the head to...make drama on the screen. We deal with such things as getting a haircut, or the feelings about brothers and sisters, and the kind of anger that arises in simple family situations. And we speak to it constructively.

[Senator Pastore]: How long of a program is it?

[Mr. Rogers]: It's a half hour every day. Most channels schedule it in the noontime as well as in the evening. WETA here has scheduled it in the late afternoon.

[Senator Pastore]: Could we get a copy of this so that we can see it? Maybe not today, but I'd like to see the program.

[Mr. Rogers]: I'd like very much for you to see it.

[Senator Pastore]: I'd like to see the program itself, or any one of them.

[Mr. Rogers]: We made a hundred programs for EEN, the Eastern Educational Network, and then when the money ran out, people in Boston and Pittsburgh and Chicago all came to the fore and said we've got to have more of this neighborhood expression of care. And this is what -- This is what I give. I give an expression of care every day to each child, to help him realize that he is unique. I end the program by saying

"You've made this day a special day By just your being you There's no person in the whole world like you And I like you, just the way you are"

And I feel that if we in public television can only make it clear that feelings are mentionable and manageable, we will have done a great service for mental health. I think that it's much more dramatic that two men could be working out their feelings of anger -- much more dramatic than showing something of gunfire. I'm constantly concerned about what our children are seeing, and for 15 years I have tried in this country and Canada, to present what I feel is a meaningful expression of care.

[Senator Pastore]: Do you narrate it?

[Mr. Rogers]: I'm the host, yes. And I do all the puppets and I write all the music, and I write all the scripts --

[Senator Pastore]: Well, I'm supposed to be a pretty tough guy, and this is the first time I've had goose bumps for the last two days.

[Mr. Rogers]: Well, I'm grateful, not only for your goose bumps, but for your interest in -- in our kind of communication. Could I tell you the words of one of the songs, which I feel is very important?

[Senator Pastore]: Yes.

[Mr. Rogers]: This has to do with that good feeling of control which I feel that children need to know is there. And it starts out, "What do you do with the mad that you feel?" And that first line came straight from a child. I work with children doing puppets in -- in very personal communication in small groups.

"What do you do with the mad that you feel When you feel so mad you could bite When the whole wide world seems oh so wrong And nothing you do seems very right What do you do, do you punch a bag Do you pound some clay or some dough Do you round up friends for a game of tag Or see how fast you go It's great to be able to stop When you've planned the thing that's wrong And be able to do something else instead And think this song I can stop when I want to Can stop when I wish Can stop, stop, stop anytime And what a good feeling to feel like this And know that the feeling is really mine Know that there's something deep inside that helps us become what we can For a girl can be someday a lady And a boy can be someday a man"

[Senator Pastore]: I think it's wonderful. I think it's wonderful. Looks like you just earned the 20 million dollars.

3 notes

·

View notes