Text

Hi Alex, I really enjoyed reading your post! Your discussion on a "sense of place" resonated with me, as my own connection to nature was shaped by my childhood experiences. Like you, I spent a lot of time outdoors with my family—hiking, camping, and exploring—which instilled a deep appreciation for nature from an early age. Your reflection on how the experiences we’ve had with nature since childhood shape our environmental values, as our textbook has mentioned (Beck et al., 2018, p. 144).

I also really appreciate your emphasis on inclusivity in nature interpretation. While fostering a love for nature is important, not everyone has equal access to outdoor spaces (Beck et al., 2018, pp. 132-134). You mentioned using simple language, treating all visitors equally, and considering different learning styles—these are great approaches! Another idea could be partnering with schools or community organizations to bring nature interpretation to urban areas where access to green spaces may be limited. Virtual experiences, like live-streamed nature walks or interactive online activities, could also help bridge this gap (Beck et al., 2018, p. 172). What are your thoughts on how technology could enhance inclusivity in nature interpretation?

Additionally, I love your point about storytelling being a powerful tool in interpretation. Our textbook highlights its benefits, particularly in capturing the attention of large audiences and engaging children (Beck et al., 2018, p. 222). From my experience working with kids, I’ve found that storytelling makes complex environmental issues more accessible and engaging. For example, when I volunteered at an elementary school, I often explained scientific concepts by relating them to the children’s own experiences and framing them as stories. This approach helped them grasp difficult topics more easily. Have you ever had a personal experience where storytelling helped someone connect with nature in a meaningful way?

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

Blog 10: My Personal Ethic

Introduction

Throughout the Nature Interpretation course, I have learned valuable principles that help people connect with and appreciate nature. As I develop into a nature interpreter, my personal ethics consist of the passion for informing others, appreciation for nature, inclusivity, and curiosity.

In the first week of the course, I learned about the concept of a “sense of place”, which is the connection people feel to the surrounding environment (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, Chapter 1, p. 10). This allowed me to reflect on how I got my own sense of place, which came from my dad who would observe and ponder nature's beauty at our family's cottage with me. Thinking about these experiences helped me realize how my appreciation for nature has evolved over time. Nature’s amenities bring me comfort and peace of mind, making me even more passionate about helping others discover, experience, and appreciate nature and culture in their own unique ways (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, Chapter 1, p. 14).

My family's cottage, where I developed a "sense of place".

My Beliefs

I firmly believe that everything in nature plays a role in maintaining its ecosystem. Regardless of size, each component is necessary for the environment to thrive. However, understanding nature’s significance can be challenging, which is why I strive to bridge the gap between science and the natural world. By combining the two, I hope to effectively address critical issues like climate change while simplifying complex ideas (Wals, Brody, Dillon, & Stevenson, 2014). Interpretation requires much more than scientific knowledge; it requires enthusiasm to make its beauty clear. To make a lasting impact, I believe I must share information in stimulating ways.

Another belief I have is that viewing nature from several perspectives is essential to enhance the way we perceive the environment. This can be completed through real-life experience, indigenous knowledge, art, museums, and narratives (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, Chapter 5, p. 100). Engaging the senses, including seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting further ensures that nature’s true effect is being felt (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, Chapter 5, p. 100).

Finally, arguably the most meaningful lesson I’ve learned is that people protect what they love. This idea greatly influenced me to create experiences that allow individuals to form genuine connections with the natural world. Fostering this connection will inspire a stronger interest in preservation, which is especially crucial today (Rodenburg, 2019). Recent reports mention that as of January 2025, global temperatures have reached record-breaking levels, posing a major threat to wildlife and weather patterns (Nature Geoscience, 2025).

My Responsibilities as a Nature Interpreter

My responsibilities as a nature interpreter are shaped by my beliefs. These duties enable me to succeed in my role by sharing information and forming deep relationships between humans and the natural world. I strive to educate others about sustainability and the glory of the environment while promoting inclusivity and evoking curiosity to ensure everyone is properly informed and included.

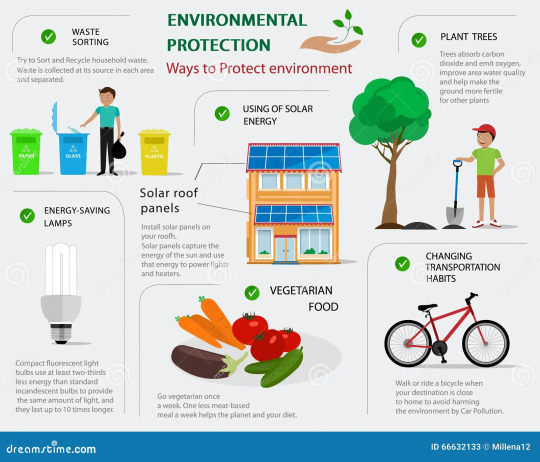

As mentioned, I accept that it is my purpose to educate others about the importance of sustaining the environment (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, Chapter 5, p. 96). I aim to inspire people to make minor yet meaningful changes to their everyday routines, such as conserving water and energy, recycling, using environmentally friendly transportation, planting trees and respecting wildlife (NDEP, 2024). Integrating these simple practices can slow down the rapidly changing climate while preserving clean spaces for the activities we cherish, like relaxing, gathering with loved ones, or engaging in physical activity (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, Chapter 3, p. 49).

Additionally, I aspire to promote inclusivity, as everyone should have the equal opportunity to enjoy nature, regardless of their background, skills, or experiences. By using simple language, treating all visitors equally, considering different learning styles, and acknowledging the cultural significance of various natural areas, I hope to create a welcoming environment where economic, cultural, and communication barriers, as well as, fear, are minimized for all (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, Chapter 7, p. 131-135).

Lastly, a nature interpreter is expected to evoke curiosity in their audience. Therefore, I encourage my visitors to explore nature themselves, to form personal experiences and to perceive nature in their own way. Discovering new things motivates individuals to continue learning about the mysteries and glory of the environment around us. Curiosity and self-discovery can spark a lifetime appreciation for the environment, as discovery leads to a closer bond with nature (Rodenburg, 2019).

Sustainable practices that can help protect the environment. (https://www.dreamstime.com/stock-illustration-environmental-protection-infographic-flat-concept-ways-to-protect-environment-ecology-infographic-vector-illustration-image66632133)

Most Suitable Approaches

Everyone has their own learning styles, emphasizing the importance of interpreting in a way that appeals to a broad audience. I believe the most suitable approaches include hands-on learning, storytelling, visuals, and asking questions.

Aldo Leopold stresses the importance of providing first-hand experience, which uses all five senses (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, Chapter 5, p. 100). People learn best when they experience something for themselves; therefore, designing activities that motivate visitors to physically engage with nature would allow them to develop meaningful connections (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, Chapter 5, p. 88). For example, organizing a scavenger hunt to find animal tracks or specific species, would not only evoke curiosity but also demonstrate nature’s interconnectedness and beauty.

Bluntly stating facts can fail to engage the public, highlighting the importance of effectively delivering information. Storytelling is a powerful method to bring nature to life, especially for those who do not have the assets to travel and experience diverse ecosystems. For instance, the story of the Boys & Girls Club illustrates how some people lack the privilege to view nature in the same way as others (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, Chapter 7, p. 127). Through narratives, interpreters can paint a realistic picture, helping audiences feel as if they are experiencing a scenario themselves. Furthermore, storytelling is effective for educating children (Rodenburg, 2019).

Many people, including myself, learn better through visuals due to a short attention span (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, Chapter 8, p. 166). Utilizing resources like photos, diagrams, and videos, can make people feel more invested in the material presented. Since nature interpretation serves a wide audience, including children, incorporating visuals makes the information accessible and engaging for most learners (Rodenburg, 2019).

Finally, asking questions is an effective way to encourage people to reflect on their experiences and think about nature from different perspectives. Additionally, it forces individuals to pay closer attention to details. For example, asking “Why do you think this flower is by itself in the field?” encourages visitors to consider how species interact with one another, demonstrating nature’s glory.

youtube

I've included a video on how to engage an audience when presenting, which is helpful in interpretation.

Conclusion

My personal ethic will continue to evolve as I gain more experience as a nature interpreter. However, I will always carry my values including, informing others, inspiring appreciation for nature, encouraging inclusiveness, and generating curiosity, as these principles are crucial. Furthermore, I want to foster a lifelong love for the environment through interactive exercises, storytelling, and asking questions. I aim to Increase the number of people who feel a deep sense of responsibility and connection to the natural world (Beck, Cable, & Knudson, 2018, p. 182).

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

Nature Geoscience. (2025). Temperature rising. Nature Geoscience, 18, 199. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01663-x

NDEP. (2024, December 11). Protecting the environment: Key strategies and solutions. Retrieved from https://ndep.org/protecting-the-environment-key-strategies-and-solutions/

Rodenburg, J. (2019, June 17). Why environmental educators shouldn’t give up hope. Environmental Literacy. Retrieved from https://clearingmagazine.org/archives/15637

Wals, A. E. J., Brody, M., Dillon, J., & Stevenson, R. B. (2014). Convergence between science and environmental education. Science, 344(6184), 583-584. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1250515

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Annie! I really enjoyed reading your discussion post—I appreciate how much thought you put into welcoming children into the world of nature interpretation! I especially liked your point about fostering a connection with nature before introducing environmental issues. I’ve seen the impact of this firsthand in my own life.

Growing up, my parents took my sister and me hiking, camping, swimming, and on countless picnics in nature. Even at a young age, I developed a deep connection with the natural world and the living things we share it with. So when I first learned about climate change at six or seven—and realized that the animals I loved were at risk—I became incredibly invested in environmental issues. My mom still tells a story about how, in first grade, my teacher mentioned that some local species were endangered, and I burst into tears in class! While most of my classmates were sad but largely unaffected, I was devastated because my beloved animal and plant friends were in trouble. Now, over a decade later, I’m still passionate about these issues and determined to make a difference.

That’s why I agree that children are such an important audience for nature interpretation. They are the future stewards of our world, and fostering a love for nature early on can inspire a lifelong dedication to environmental justice (Beck et al., 2018, p. 144). I’d love to hear your thoughts on a question related to your post: You highlight the importance of frequent outdoor experiences for children, which I completely agree with. However, many children face barriers—such as socioeconomic factors or limited access to green spaces—that make these experiences difficult (Beck et al., 2018, pp. 133-134). How do you think nature interpreters can help bridge this gap and make nature more accessible for all children?

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

Blog 10: Discovering my Personal Ethics on my Interpreter Journey

As I consider my journey as a nature interpreter, I see how my ethics greatly influence how I portray the natural world's significance, beauty, and complexity. This ethic stems from my views on the environment, my duties as an interpreter, and the methods that work best for my character and strong points. In an era where environmental challenges seem overwhelming, I am committed to fostering a sense of connection, wonder, and responsibility in those I engage with, particularly children, who are the stewards of our future.

My ethics are based on a profound admiration for the natural world and an understanding that all living things are valuable. Instead of portraying the environment as something outside that has to be preserved, my method of interpretation views it as something we are obligated to protect as responsible members of the global community. However, as an environmental interpreter in the modern world, I quickly feel discouraged. It can seem impossible to overcome the scale of problems such as climate change, habitat destruction, plastic pollution, and species extinction. However, despite these obstacles, the core of environmental education should be empowerment and hope.

A beautiful view of our environment, and that we need to protect it.

Before being burdened with the problems of the natural world, children require the chance to develop strong bonds with nature. Young children are not emotionally or cognitively prepared to comprehend problems like pollution and global warming. While educating students about the potential and strength of reclaiming nature in their parks and schoolyards, we should also help them discover their magical places, stories, and places within them (Rodenburg, 2019). Instead, they should be allowed to develop a strong relationship with the natural world. They will only be inspired to defend it by love and a personal bond as they grow up.

Recognizing my responsibilities as a nature interpreter is essential to understanding my role. These obligations go beyond merely disseminating knowledge; they also entail encouraging a mental and emotional bond with nature. My primary duties consist of:

1. Facilitating Connection and Wonder

2. Providing Age-Appropriate Education

3. Inspiring Stewardship and Action

All three of these duties involve educating children on the different aspects of an important relationship with nature. Lack of opportunities causes children to become disconnected from nature, as school systems limit outdoor exploration because of liability concerns. Our nature interpreters are responsible for providing both adults and children with safe experiences. While older individuals can better comprehend environmental challenges, my role is to accommodate people's cognitive and emotional readiness by focusing on storytelling and personal nature experiences for younger children. Frequent outdoor experiences give kids a strong sense of community, a profound respect for the natural world, and a basis for future conservation initiatives (Beck, 2018, p.186).

As I develop my skills as a nature interpreter, specific approaches resonate more strongly with my personality and teaching style. These methods include storytelling, hands-on activities, teaching children about “magic places,” and encouraging reflection and mindfulness.

Stories make information meaningful and memorable. They evoke strong emotions, whether they are about a local animal overcoming adversity, a migrating butterfly's journey, or a tree's survival techniques. By telling simple stories about their interactions with wildlife, students can be converted from passive learners into fervent protectors.

Direct interaction with nature is the most effective way for adults and children to connect with it. Nature journaling, wildlife tracking, pond-dipping, and guided hikes are all effective ways to promote participation. Children should be able to enjoy the delight of learning about the diversity, complexity, and richness of life. I can assist participants in developing enduring relationships with the natural world by designing immersive, hands-on experiences.

When children are encouraged to visit the same outdoor areas regularly, they can grow up to care for a particular place and feel a sense of belonging. This lasting bond nurtures a profound respect for the natural world and is a basis for subsequent conservation initiatives.

One of the most important aspects of promoting environmental awareness is teaching people to slow down and pay attention to their surroundings. Silent seats, sensory walks, and creative writing inspired by nature are some activities that help participants go beyond casual observations and develop a deeper understanding of the environment (Rodenburg, 2019).

It has been a journey of reflection and experience to develop my ethics as a nature interpreter. My role is to inspire as much as to inform. It is my job to make it possible for people to have joyful, approachable, and personally fulfilling connections with nature. To counteract a lack of interest in the environment, I try to inspire awe, cultivate a sense of duty, and offer an optimistic, action-oriented education.

I want to ensure that everyone I interact with has the chance to develop a strong and enduring connection with nature, whether that is through storytelling, practical experiences, or personal relationships with it.

My dedication to connection—connection to place, stories, hope, and ultimately to action—defines my ethics as a nature interpreter. Although many obstacles exist to overcome, cultivating a love of nature has even more power.

I keep reminding myself as I go along those relationships, like our relationships with nature, our communities, and ourselves—are what bring about change. Every discussion fuels a broader movement of environmental awareness and care, every moment of shared wonder, and every seed of curiosity sown in a child's mind. Even though I might never see the results of my efforts in their entirety, I have faith in inspiration's cascading effect because I know that even the smallest moments of connection can result in significant and long-lasting change.

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing

Rodenburg, J. (2019, June 17). Why environmental educators shouldn’t give up hope. CLEARING. https://clearingmagazine.org/archives/14300

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prompt 10: Describe your personal ethic as you develop as a nature interpreter. What beliefs do you bring? What responsibilities do you have? What approaches are most suitable for you as an individual?

Nature is something I deeply value in my life. As a zoology major with a minor in ecology, and someone who aspires to pursue a career in these fields, the natural world drives my goals, passions, and ambitions. Because of this, nature interpretation is something I take seriously. If I am passionate about nature, then the people who listen to me talk about it will feel passionate as well (Beck et al., 2018, p. 83). That is also why I believe having a personal ethic—guiding principles and values that shape the way I present nature to others—is essential. Nature interpretation plays a crucial role in environmental protection, as it allows people to gain a deeper understanding of the world around them and, in turn, inspires them to work harder to protect the land (Beck et al., 2018, p. 475). This belief is central to my identity, both as a nature interpreter and as an individual. I strongly believe that nature is valuable not just in its usefulness to humans, but beyond that, in its role for all living organisms. Because this is one of my core beliefs, I feel it is my responsibility as a nature interpreter to convey this perspective to others in a way that fosters positive change (Beck et al., 2018, p. 99).

Another key belief I bring to my role as a nature interpreter is that interpretation should always be evidence-based. As someone planning to pursue a career in academia, I have a responsibility to present scientific information accurately. It is easy for misleading or oversimplified messages to slip into conversations, but as interpreters, we must ensure the information we share is factual and reliable. However, nature interpretation is not just about presenting facts—it is about making them engaging and memorable for the audience (Beck et al., 2018, p. 83). As our textbook emphasizes, interpreters must be able to connect with a diverse audience, as interpretation is meant for everyone, not just those with a scientific background (Beck et al., 2018, p. 93). This means making information accessible and interesting, even for those who may not have studied science in years. It also requires recognizing and addressing the diverse perspectives and cultural backgrounds of our audience, ensuring that interpretation is inclusive and meaningful to all (Beck et al., 2018, pp. 131-132). It is my responsibility, as well as that of all nature interpreters, to recognize the barriers that minorities may face in the field of nature interpretation, including economic, cultural, communication, and educational challenges (Beck et al., 2018, pp. 133-134). By breaking down these barriers and making interpretation more accessible, we can effectively communicate our messages and inspire positive change in a wider audience.

One way I can make my interpretation more accessible is through storytelling and poetry. Our textbook highlights the value of incorporating various art forms into interpretation (Beck et al., 2018, p. 216), and for me, storytelling and poetry are the most effective forms of artistic expression. Stories are powerful tools for engaging audiences, particularly when interpreting for children who may find narratives more relatable and digestible than straightforward explanations (Beck et al., 2018, p. 222). I have linked a video below that provides an example of how storytelling can be used to teach children about environmental protection—notice how characters, dialogue, and plot structure help convey an important message in an engaging way. Poetry, on the other hand, can evoke emotional responses while still communicating a message (Beck et al., 2018, p. 225). I have previously used both of these art forms in my blog posts, such as telling a story about raccoons in Unit 9 to engage readers and writing a short poem about the Arboretum in Unit 4. In both cases, these creative approaches allowed me to communicate key ideas without directly stating them, making the message feel more natural and immersive. Storytelling and poetry have been used across cultures for generations to convey important lessons (Beck et al., 2018, p. 223), so I believe they are valuable tools for nature interpretation as well.

youtube

Another approach that I find effective is using interactive and hands-on learning techniques. In Unit 2, I learned that I am primarily a bodily-kinesthetic learner, meaning I learn best through movement and active engagement (Beck et al., 2018, p. 110). Additionally, I discovered that I am a naturalistic learner, meaning I enjoy learning about and in nature, and a logical-mathematical learner, meaning I am drawn to problem-solving (Beck et al., 2018, pp. 111-112). Given these strengths, I believe an effective approach to nature interpretation for me would involve engaging audiences through hands-on activities that foster curiosity and problem-solving. For example, I might take participants out into nature, allowing them to experience firsthand what we are striving to understand and protect, while encouraging them to ask questions and engage in active thinking. While it is important to make interpretation accessible to individuals with various learning styles, I also believe there is value in playing to my strengths as an interpreter to create the most impactful experience for my audience.

Beyond engaging others, I believe it is my responsibility to continually develop and refine my own skills as a nature interpreter. Growth in this field is essential for creating experiences that not only draw people into nature but also affect them emotionally and intellectually (Beck et al., 2018, p. 419). One way to achieve this is through self-evaluation—reflecting on my own methods and identifying areas for improvement (Beck et al., 2018, p. 423). Additionally, feedback from supervisors or peers can provide valuable insights into how my interpretation techniques are received and where they might be enhanced (Beck et al., 2018, pp. 421-423). Ongoing learning is also crucial (Beck et al., 2018, p. 461), whether through attending workshops, taking courses, or seeking mentorship from experienced professionals. As someone who hopes to become a professor in zoology and ecology, my interpretation skills will be invaluable in my future career, both in research and in teaching. This course has provided me with an incredible opportunity to explore the art and science of interpretation, and I am grateful for the knowledge and skills I have gained.

Thank you to everyone following my blog—I have had so much fun throughout this journey!

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Chayse! It’s fantastic that you’re so active on iNaturalist! I’ve also been using it more lately, and I’m always blown away by how such a simple tool can connect us with the natural world. As our textbook discusses, technology can be a powerful facilitator for nature interpretation when used effectively (Beck et al., 2018, p. 122). It can help engage people who may not typically be involved in science, encouraging them to participate and develop a deeper connection to nature. I’ve included an image of a brown marmorated stinkbug that I also spotted in the Arboretum and shared on iNaturalist. Along with iNaturalist, I’ve also used other apps like Merlin Bird ID and Seek (which is actually another app by iNaturalist). I particularly enjoy Seek because it includes challenges and achievements that make identifying species feel like a fun game!

Holding what I suspect to be a brown marmorated stink bug, found during one of my visits to the Arboretum.

Do you think platforms like iNaturalist and Seek could eventually play a larger role in scientific research? For example, could they help in identifying new species or tracking biodiversity trends over time? This brings up the idea of citizen science, which I believe is often underappreciated in the scientific community. Not only are these platforms useful for research, but they also encourage everyday citizens to get involved in the scientific process. I think this is especially helpful for people with body-kinesthetic or naturalistic learning styles, who may learn and understand science better when they have the opportunity to physically engage with it and contribute to data collection (Beck et al., 2018, pp. 110-112). To explore more opportunities to get involved in citizen science, I’ve linked a portal from the Canadian government’s website below—it even includes a project that uses the iNaturalist app!

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

Unit 9 Blog Post - Interpreting my Favorite Insect Identifications!

When I read this blog prompt, I instantly knew I wanted to use this post to share some of my favourite observations on iNaturalist and use that as my way of bringing the field to you! Most of the most amazing things I know about nature about bugs, so I will interpret this to you all through photos! I also think this fits well with our unit content, as this week’s textbook reading discussed iNaturalist and other, similar, citizen science initiatives (Beck et al., 2018). I am quite active on iNaturalist because I feel like I have an insatiable thirst for knowledge, so when I see an animal that I can’t identify off the top of my head, I NEED to know what it is- and iNaturalist is perfect for that!

The first insect that I want to share with you are Woolly aphids, specifically beech blight aphids (Grylloprociphilus imbricator), which are shown in the video above! Last semester while doing field work in an arboretum pond for my limnology class, I saw a branch on a tree that seemed to be moving and fuzzy… upon closer inspection I realized that my eyes weren’t playing tricks on me… the branch really WAS moving AND fuzzy. This was my first time seeing a woolly aphid, so I honestly was having a difficult time comprehending exactly what I was looking at, nevertheless I immediately started taking a video and trying to identify the thing I was seeing. Through zooming in I could see a little amber ball on each of these moving things, instantly I knew this was some type of aphid, or at least a hemipteran. Hemipterans are ‘true bugs’, an order of insects with piercing-sucking mouthparts and two pairs of wings. The little amber ball that you see on the back of each aphid is called “honeydew”- this is a sugar-rich secretion that is produced by phloem-feeding hemipterans, such as aphids. Honeydew is a resource that is often preyed upon by other insects, especially ants. Ants use aphids as a form of livestock, carrying aphids to different plants through their lifecycle and defending them in order to use the honeydew (McVean, 2017)!

The next insect that I am going to share with you is a green-striped grasshopper! This is a photo that I took last summer in preservation park while trail running- I nearly tripped while trying to stop and take a photo of this guy when I spotted it! I run a lot on trails in the summer so that’s when I find I get the most identification done. I definitely slow myself down doing this… and miss a lot of bugs because I’m running… but it combines two things I love into one, so I don’t mind! Now, I’m sure grasshoppers are not a new thing to anybody reading this, but seeing this photo of a grasshopper made me think of a cool fact that I wanted to share!

Pink grasshopper pic is from Michelle W., @pufferchung on iNaturalist

No, this photo of a pink grasshopper is NOT photoshop, pink grasshopper morphs are real and do exist in nature! The pink colour is caused by a rare genetic mutation known as erythrism- this is a recessive gene like the one that causes some animals to be albino (Griffiths, 2023). Naturally, this makes it very difficult for the individual to properly camouflage, therefore it is generally selected against making these very rare to find.

The third insect that I am going to talk about is another hemipteran that had a very big year last year… The cicada! The cicada that is pictured above is a dog day cicada, they emerge in August, the ‘dogdays’ of summer. However, last year there was a huge cicada event that happened south of the border, featuring a different type of cicada, which I’m sure many of you have already heard of. There was a double periodical cicada emergence of brood XIII and XIX throughout some parts of the USA (Sherriff, 2024). But what does this mean? Periodical cicadas are any of the seven species from the genus Magicicada, these cicadas breed on either a 13- or 17- year cycle, where they breed, die, and their larvae go dormant underground for years before emerging and beginning the cycle again. In 2024, both the 13- and 17- year broods emerged at the same time, causing a massive and rare explosion of cicadas (Sherriff, 2024). This was a dream for insect lovers, and a nightmare for insect haters. I wished I could have been able to make it to the states to see/hear it myself, however this dog day cicada was the only one I got to see.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing

Griffiths, E. (2023, July 3). Rare pink grasshopper spotted in garden. BBC Wales News. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/czknv1233dko

McVean, A. (2017, August 16). Farmer ants and their aphid herds. McGill Office for Science and Society. https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/did-you-know/farmer-ants-and-their-aphid-herds#:~:text=Several%20species%20of%20ants%20have,ants%20as%20a%20food%20source.

Sherriff, L. (2024, May 6). Cicada dual emergence brings chaos to the food chain. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240501-cicada-dual-emergence-brings-chaos-to-the-food-chain

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prompt 9: Interpret (through this blog) the most amazing thing you know about nature – get us excited. This is your blog – your audience isn’t out in the field with you so bring the field to your armchair reader.

Our textbook states that one of the challenges interpreters face is capturing and maintaining the audience’s attention (Beck et al., 2018, p. 166). Later, it also highlights that one of the most effective ways to engage large audiences is through storytelling (Beck et al., 2018, p. 222). So, let me tell you a story.

Imagine it’s a quiet Tuesday morning. You’re at the bank, using the ATM before heading to work. The bank hasn’t even opened yet, and you’re the only person there. Suddenly, you hear a noise—a rustling sound from inside. Then, a loud crash! You glance through the window and see two masked figures. Heart pounding, you grab your phone, ready to call… animal control?

As it turns out, these robbers weren’t after money. They were after a tin of almond cookies! That’s because they weren’t people at all—they were raccoons! (I’ve linked two news articles below in case you need proof!) This story is one of my favorites because it challenges the idea that raccoons are just unintelligent pests. In reality, they’re incredibly resourceful problem-solvers, capable of navigating complex situations—like breaking into a bank for a snack.

Raccoons aren’t the only animals that demonstrate remarkable intelligence. One of the most fascinating examples in nature comes from the octopus. Often called escape artists, these cephalopods have stunned aquarium staff worldwide with their ability to sneak out of enclosures, open jars, and even steal food from neighboring tanks (Hunt, 2017). Some have learned to turn off lights and short-circuit power supplies, while others have demonstrated the ability to solve intricate puzzles when properly motivated (Hunt, 2017). If you have a few minutes, I highly recommend watching this video by YouTuber Mark Rober, where an octopus solves a complex underwater puzzle! (Bonus: He has other great videos showcasing animal intelligence, like obstacle courses for squirrels and testing a highly intelligent crow.)

youtube

What amazes me most about nature is how intelligence isn’t limited to just humans. A wide variety of animals, from primates to birds to invertebrates, have demonstrated cognitive abilities that challenge traditional views of intelligence (Bitterman, 1965). What’s even more fascinating is that, like humans, different species have different learning styles (Bitterman, 1965). But why has intelligence evolved in so many species? The answer lies in survival. Problem-solving skills help animals find food, avoid predators, and adapt to changing environments—giving them a distinct evolutionary advantage (Bitterman, 1965). Intelligence isn’t just a human trait; it’s a key part of life across the animal kingdom.

Have you ever witnessed an animal doing something unexpectedly smart? Maybe your pet learned a behavior you never intended to teach them, or you encountered a wild animal that seemed to know exactly what it was doing. Or perhaps you’ve just heard an incredible story about animal intelligence. I’d love to hear about it—share your experiences in the replies!

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

Bitterman, M. E. (1965). The evolution of intelligence. Scientific American, 212(1), 92–101. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24931751

Hunt, E. (2017, March 28). Alien intelligence: the extraordinary minds of octopuses and other cephalopods. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/mar/28/alien-intelligence-the-extraordinary-minds-of-octopuses-and-other-cephalopods

Larthridge, R. (2020, October 25). How a pair of raccoons (probably) broke into a bank. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/10/25/us/raccoon-bank-intruders-trnd/index.html

Sullivan, H. (2020, October 22). Hand over the trash: raccoons break into California bank. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/oct/22/give-me-all-your-trash-raccoons-break-into-california-bank

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Ashley! I love that you brought up how Indigenous people use music to connect with nature. Your experience at the Akwesasne Powwow sounds incredible! It makes sense that you felt such a deep connection to nature and history during that experience—music and dance have a powerful way of evoking emotions, which is why they are such valuable tools for interpretation (Beck et al., 2018, p. 226). I recently read that traditional drumming isn’t just music—it’s also a form of storytelling and spiritual connection. Did you get a chance to learn about the meaning behind any of the songs performed at the powwow?

I also love The Lumineers! Stubborn Love is one of my favorite songs by them. It’s so interesting how different genres of music evoke different emotions, just like you mentioned. Research has shown that even children as young as three can recognize emotions in music (Peretz, 2006), which suggests that our responses to music are deeply ingrained. Your post made me curious about why music affects us in such powerful ways, so I found this fascinating blog post that explains how different types of music activate different parts of the brain.

Additionally, lyrics play a key role in shaping how we interpret music. This makes music an especially effective interpretive tool (Beck et al., 2018, p. 225-226), since both the genre and lyrics can reinforce a message—whether that message is simply to pause and appreciate the beauty of nature or to call attention to pressing environmental issues. One song that does the latter is Feels Like Summer by Childish Gambino. At first listen, it feels like a laid-back summer song, but the lyrics actually highlight serious issues like pollution, declining bee populations, and water scarcity. It’s a great example of how music can not only reflect nature but also advocate for its protection.

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

Peretz, I. (2006). The nature of music from a biological perspective. Cognition, 100(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2005.11.004

Blog 7: Nature and Music

My first thought seeing the topic this week as nature and music before even reading through this week’s material, was “What a Wonderful World” by Louis Armstrong. I could quote the entire song for its lyrics about the beauty of nature, however, my favourite is “I see skies of blue, and clouds of white, the bright blessed day, the dark sacred night.” This verse makes me want to wake up early, watch the sunrise, and listen to birds chirp on a hot summer morning. I think we can all agree that the song makes you feel something and it’s usually a good feeling.

After reading through the course material, I realized I got ahead of myself and did the post backward, however, I am going to stick with it. I started thinking about how natural sounds within nature make their song and that importance in Indigenous culture that is discussed in this week’s material. Music is used to reflect their relationship with nature and communicate with the fallen. Their music consists of both natural sounds wind, water, and animals, along with sounds from their traditional musical instruments like flutes and drums.

I am from Cornwall, Ontario, which is on traditional Mohawk land with a reservation. In high school, our history teacher took us to the reserve to witness a pow-wow as our current topic in class was Indigenous schools and Canadian Indigenous history. The day consisted of watching dances, listening to traditional songs being sung, and touring the tables of information and cultural gifts. I can’t thank my teacher enough for the field trip because it really took history off the paper for me. The motto of the Akwesasne Powwow is “Where the best drummers, dancers and artisans of the region come together”, and that really was the truth.

Recognizing the value of Indigenous perspectives as interpreters helps us expand our understand traditional knowledge, rather than what we already know. We should be embracing storytelling, music, and Indigenous learning to make environmental education more immersive and meaningful rather than seeing nature as something to study from a distance.

In terms of nature in music, I can definitely agree with the prompt that music is associated with hot summer days around a campfire or on a road trip. My favourite music to listen to while hiking, camping, or just sitting outside watching the currents on the lake, is “The Lumineers”. Pretty much any of their songs from “The Lumineers” and “Cleopatra” album are on repeat in the summer! Their folky-rock vibe with the guitar and piano sound really just makes me think of walking through a forest with a huge backpack while wearing ugly hiking shoes. This post is really making me miss summer and I would love to hear how you guys connect nature and music!

Nature is full of natural sounds like crunching leaves, waves crashing onto rocks, birds chirping in the morning, and crickets chirping at night. It is so fascinating to me how different areas and landscapes have their own soundtrack. I’m sure sometimes we don’t even realize but no matter where you are, nature is playing a song designed perfectly for what you are looking at. Really makes me want to stop and look around more often.

Here is a link to the Lumineers Spotify {I'm sure you already listen to them (: https://open.spotify.com/artist/16oZKvXb6WkQlVAjwo2Wbg?si=PEtgG8EkRnSTbnEGz_a3Kg

The link for the Akwesasne Mohawk Powwow

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prompt 7: Where is music in nature? Where is nature in music? As a follow-up (focus on the previous two before you tackle this one), what song takes you immediately back to a natural landscape? What is the context? Share it with us – I would imagine many of these ideas may have similar underpinnings of a campfire, roadtrip, backpacking journey, etc.!

Music is often considered a universal human trait, as nearly every culture throughout history has participated in some form of musical expression (Peretz, 2006). Some researchers even argue that certain aspects of music are ingrained in our genetics (Peretz, 2006). Because music is so deeply connected to the human experience, it can be an incredibly effective tool in nature interpretation. Studies have shown that even children as young as three years old can recognize emotions in music (Peretz, 2006). Our textbook notes that one of the challenges interpreters face is capturing and maintaining the audience’s attention despite competing distractions (Beck et al., 2018, p. 166). Music can help with this, as it naturally draws people in and enhances memory retention of key messages (Beck et al., 2018, p. 225).

Clearly, there is something inherently natural about making and enjoying music. This is why, when we take a moment to truly listen to nature, we can hear its own form of music. Birds chirp, whales sing, frogs croak, and crickets chirp—these are just a few examples of how animals communicate with one another, much like humans do through music. The ability to communicate with members of one’s species provides many advantages, which may explain why music-like sounds are so prevalent in the natural world. These beautiful sounds are nature’s way of fostering connection!

Beyond vocalizations, nature also creates more abstract forms of music, such as the sound of a river running, the wind blowing, or leaves rustling. While these sounds may not be intentionally produced, they still evoke emotional responses in humans—often a sense of calm or relaxation. This natural connection may explain why nature sounds are frequently incorporated into human music. Many people use nature soundscapes for meditation or sleep due to their soothing effects. Personally, I have a playlist of natural soundscapes, some of which are blended with soft instrumental music, that I listen to when I need a calming backdrop. I’ve linked it below! These tracks help transport me back to a natural setting, which is especially valuable during the winter months when I’m unable to spend as much time outdoors as I’d like.

Nature’s influence on music isn’t limited to soundscapes—many songs incorporate nature sounds as part of their composition. One of my favorite examples is Wildflower and Barley by Hozier featuring Allison Russell. At the beginning of the song, faint bird chirping can be heard, immediately evoking the imagery of a natural landscape. The song’s poetic lyrics, paired with its gentle melody, create an immersive experience that makes me feel as though I’ve been transported to a field of wildflowers and barley.

Finally, I want to highlight the incredible diversity of music in both nature and human culture. Every bird sings a unique song, every forest has its own distinct whispers, and every person resonates with different sounds. With thousands of music genres out there—many of which I’ve never even heard of—there’s always something new to discover, and each genre speaks to someone in a special way. With that in mind, I’d love to hear your thoughts: which genre makes you feel most connected to nature, and why? If you have any specific artists or songs that capture that feeling, please share—I’m always looking for new music!

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

Peretz, I. (2006). The nature of music from a biological perspective. Cognition, 100(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2005.11.004

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Chayse! I really enjoyed reading your post—I appreciated how you used your own experiences to analyze and connect with this quote. The way you described the Lower Fort Garry National Historic Site sounds like an incredible experience, and it makes me wish I had the opportunity to engage in first-person interpretation. While I haven’t had an experience quite like that, I do enjoy going to museums and simply sitting silently, imagining myself in different eras. Seeing ancient artifacts and historical scenes helps me feel more connected to the past.

As you pointed out, it’s easy to forget that history actually happened—it’s not just something we read about in textbooks. The best way to remind ourselves of this is by engaging with first-hand accounts, such as diaries, which you mentioned in your post. It’s especially important to amplify the voices of those whose stories have historically been stifled. I touched on this in my own post, but our education systems often present history in ways that favour certain groups while downplaying or erasing the experiences of others. For example, we learned about residential schools in high school history classes, but how deeply did we truly explore the atrocities committed against Indigenous children? I would argue that we did not go nearly deep enough.

To expand on this, I’d like to share a CBC article written by a residential school survivor. Fair warning—it is difficult to read, but I believe confronting this discomfort is necessary. Without a proper understanding of our history, we risk repeating the same injustices.

Blog post 6: Quote response

To me, this quote and the content of this unit both outline the importance of continuously remembering history, if we don’t remind ourselves of what happened in the past, we are doomed to repeat our mistakes. Interpretation is one of the keys to ensuring the past continues to be remembered in a nuanced way; it is important for there to be people that are knowledgeable about historical events and the nuances around them to share this knowledge with the public in an interesting and condensed way. In the textbook this week, one of the topics that stuck out was the discussion of first-person interpretation (Beck et al., 2018). This is a type of interpretive experience that I have actually been a part of; when I was a kid I lived in Manitoba and went to a summer camp at the Lower Fort Garry National Historic Site. This is a former trading post that was a part of the Hudson Bay Company which now serves as a historic site. The cast members here dress and act like they would have when the Fort was in function, and as a camper we also got to dress up and live as a pioneer for the week! This was an amazing interpretive experience for me, as I find that the more immersive an experience is, the more I remember it. This type of experience truly makes you feel like ‘the train station you passed through still exists’ as Hyams states, an immersive interpretive experience makes the information you are learning feel more real, there were actual people living like this, doing these things in the place I am many years ago.

This is how everybody dressed at Fort Garry, including all the campers!

Interpretive writing is also essential to the preservation of history. The textbook discusses the importance of journaling and in my opinion, this is one of the most important type of interpretive writing for the preservation of history (Beck et al. 2018). History can be preserved through things like news or documents, though these will often all be biased in a similar way. The best way to understand different historical perspectives, especially those from groups that have been oppressed, is through analyzing journals. Journals themselves are firsthand accounts of things that have happened, and include personal anecdotes and feelings that add depth to the story being told. A good example of this is The Diary of Anne Frank, I read this book in high school before travelling to Amsterdam and visited the Anne Frank house; this humanized a person from history in a unique way for me. To read about her crushes, going to school, her friends and silly normal kid thoughts made me feel connected to a historical time in a similar way to the way I felt at Fort Gary. This was a kid just like me, and she had so many of the same universal ‘kid’ experiences that we all have had.

Though these anecdotes both refer to specifically historical interpretation, though these are still relevant to effective nature interpretation. Nature interpretation through writing can serve as an important historical documentation, creating a narrative about what was going on in the environment at a certain time. An excellent example of this is Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. This is a book that documents the harmful effects of the pesticide DDT that was used in abundance at the time. This book is personal and poetic, giving a present-day reader a deep understanding of how dire the situation in the environment was at the time, and how important it is that we don’t let something like that happen again. I think the blog prompt this week is very relevant to this idea. If we have the mindset that the train station that we’ve already passed through has disappeared we are doomed to repeat it again. I think in a social and political climate like we are living in today, it is extremely important to understand this and to actively seek out information about past events to prevent history from repeating itself.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

Photo: Steiner, B. (2020). [Digital |Image]. Journeys with Johnbo. https://photobyjohnbo.com/2020/01/07/lower-fort-garry/

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prompt 6: Unpack the following quote...

There is no peculiar merit in ancient things, but there is merit in integrity, and integrity entails the keeping together of the parts of any whole, and if these parts are scattered throughout time, then the maintenance of integrity entails a knowledge, a memory, of ancient things. …. To think, feel or act as though the past is done with, is equivalent to believing that a railway station through which our train has just passed, only existed for as long as our train was in it. — Edward Hyams, Chapter 7, The Gifts of Interpretation

The first sentence of this quote suggests that integrity means keeping things whole and that we should preserve the integrity of ancient things. This includes maintaining a connection with our past. One way to achieve this is by utilizing our knowledge of heritage, as it serves as the bridge connecting the past, present, and future (Beck et al., 2018). If we wish to uphold the integrity that Hyams encourages, we must actively engage with history—by discussing it, documenting it, and continuously learning from it. Our past serves as a window into our future (Beck et al., 2018), and in order to shape that future for the better, we must first understand where we have been.

When applying this idea to nature interpretation, one crucial way to connect with the past is by studying how ecosystems evolve over time. Understanding the history of a species, landscape, or ecosystem is key to developing effective conservation efforts. By analyzing past environmental changes, human impacts, and species adaptations, we can make informed decisions to protect biodiversity and ecological integrity.

I’ve emphasized the importance of learning history, but how can we actively do so? One great way is by visiting museums! One of my favourite museums is the Royal Ontario Museum, which features sections on natural history, art, and culture. A bonus for students—on Tuesdays, full-time college and university students receive free admission! Other ways to engage with history include enrolling in history courses, reading historical accounts or books, watching informative programs on TV or YouTube, and exploring history-related blog posts (as long as the sources are reliable!).

Hyams’ quote also highlights the importance of keeping history "whole." This is crucial because, too often, history is presented in a fragmented or biased manner, particularly in formal education systems. There is a tendency to frame historical narratives in ways that favour certain groups while downplaying or erasing the experiences of others. As Winston Churchill famously said, “History is written by the victors.” A clear example of this is how the historical (and ongoing) mistreatment of Indigenous Peoples by the Canadian government is frequently minimized or overlooked. Many people find it uncomfortable to confront these realities, especially when they reveal past atrocities.

This ties into the second part of Hyams’ quote, which uses the metaphor of a train station to illustrate that just because we have moved on, it does not mean the past ceases to exist. Some argue that history is irrelevant—that the past is the past, and learning about it now is unnecessary. To that, I reference another quote by Churchill: “Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” Historically marginalized communities are often told to forget their oppression and to “move on.” However, moving on without acknowledgment and accountability only creates an opportunity for these injustices to be repeated. If we truly wish to build a better future, we must first be willing to learn from and reckon with our past.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Nadine! I really enjoyed reading your post—you chose an excellent topic. I particularly appreciate how you highlighted that the unnecessary use of scientific language and jargon can sometimes hinder our ability to communicate effectively rather than enhance it. As university students, especially those in STEM, we are constantly surrounded by academics and aspiring academics. It’s easy to forget that the majority of the population doesn’t share the same academic environment or opportunities we do.

For example, less than a third of Canadian adults hold a bachelor’s degree, and when we consider the global population, that percentage drops significantly (Statistics Canada, 2022). The privilege of pursuing higher education is one that many people don’t have access to. With this in mind, relying on complicated studies or excessive scientific jargon to convey our points may not always be the most effective approach.

As you mentioned, many people respond better to establishing an emotional connection with nature. This could involve sharing a funny fact about a species (PS: did you know that rats enjoy dancing?) or incorporating tools like art, which we discussed last week, to convey our message. It’s not about “dumbing it down”, as you pointed out, it’s crucial that we avoid talking down to the people we’re trying to inform. Rather, it’s about tailoring our communication to what works best for each individual.

People understand and connect to ideas in different ways, and instead of resisting those differences, we can embrace them to make our communication more inclusive and impactful. Great job bringing attention to this topic!

Statistics Canada. (2022). Growth in the share of Canadians with a bachelor's degree or higher accelerates [Infographic]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221130/g-a001-eng.htm

Interpretive Blog #5

Since we are free to write whatever we want this week, I base this blog on the most interesting thing I have learned thus far about nature interpretation.

One of the most intriguing things I’ve learned about nature interpretation is how storytelling can bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and emotional connection. Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage emphasizes that successful interpretation presents facts and connects those facts to visitors’ values, emotions, and personal experiences. This realization made me rethink how I approach sharing knowledge about nature, especially when interacting with people who may not have a scientific background. I have genuinely felt connected with this course and readings since my major stems from Environmental Management. I learned how environmental science affects our everyday lives and how it is integrated into business.

I used to believe that providing detailed information, such as the scientific names of species or their ecological roles, was the key to practical nature interpretation. While I found this fascinating as an environmental science student, I quickly realized through personal experience that others didn’t always feel the same way. One example that comes to mind is during a field trip in my previous class, Intro to the Biophysical Environment (GEOG 1300). During the journey, I vividly remember pointing out a native plant species and explaining its taxonomy. However, my group seemed disengaged; they were more interested in how the plant related to local wildlife or indigenous cultural practices.

Reflecting on this moment and guided by the textbook, I realized that interpretation needs to be more than just scientific accuracy. The book highlights the idea of "meaning-making," where interpreters help audiences create personal connections to what they are learning. This inspired me to shift my approach from providing pure information to crafting experiences that stimulate curiosity and emotion.

Another example that comes to mind is during my first-year Biodiversity course, where we were responsible for tracking the presence of squirrels around campus, including their colour and physical features. I remember discussing this assignment with my peer and feeling very passionate and engaged with doing it. I shared a story about the red oak tree's role in local history and how its acorns once provided a food source for Indigenous communities. I also talked about how squirrels gather and bury the acorns, which reminded my friend of the animated character Scrat from Ice Age. That small, relatable detail sparked a conversation, and my friend became more engaged. The author's emphasis on using stories to relate natural phenomena to human experiences came to life at that moment, and it was rewarding to see us connect with nature on a deeper level.

The textbook also emphasizes the need for inclusive interpretation, considering audience diversity and learning styles. I've learnt to consider accessibility, whether that means explaining complicated scientific words, utilizing analogies, or even combining podcasts and blog postings to reach those who prefer online platforms. Furthermore, what excites me most is that nature interpretation is constantly evolving. This course and insights from Beck’s textbook have shown me that interpretation is not about “dumbing down” science but about making it meaningful.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage : for a better world. Sagamore Venture.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prompt 5: No prompt this week – free write on what you are thinking about!

With midterms in full swing, I’m sure everyone is feeling the weight of stress, so I decided to write about how nature can help us find relief. Back in our first blog post, I mentioned that I enjoy outdoor meditation, and that continues to be true. One of my favourite ways to destress is to walk to the Arboretum, sit on the grass, and simply observe the ecosystem thriving around me. It’s a wonderful way to recharge without staring at a phone or sitting behind a laptop. Now that it’s winter, I don’t visit as often, but on occasion, I still venture outside into the snowy scene. I love watching the snow fall, and even though I rarely see animals, it still feels like life is gently seeping through beneath the blanket of snow.

Another great way to destress using nature is by taking a hike. This is more active than meditating, but exercise is also an excellent way to reduce stress. During these hikes, you can add an extra layer of engagement by identifying the animals and plants you encounter. Two apps I highly recommend are the Merlin Bird ID app for identifying birds and the Seek by iNaturalist app for other animals and plants. I’ve linked them below! Although winter may not bring as much wildlife as summer or spring, there’s still plenty to discover if you keep your eyes open.

It’s important to stay safe while hiking, though. Be sure to wear appropriate gear—snow boots are a must in weather like this!—stay on designated paths, avoid interacting with wild animals, and consider inviting friends to join you. Exploring nature is always more fun and safer with company.

If venturing outdoors in winter isn’t your thing, don’t worry! There are plenty of other ways to connect with nature. For example, you can watch nature videos or look at photos of natural landscapes. You can also read blogs about nature interpretation—like this one! When I’m unable to access a natural space, I love playing nature sounds. There are countless YouTube videos and Spotify playlists featuring natural soundscapes, some even mixed with calming music. I’ve linked one of my favourite playlists below! These can be especially helpful when studying or trying to focus. I also use them at night to help me sleep!

In conclusion, if you’re feeling stressed, consider tapping into the calming power of nature—whether outdoors or virtually. Good luck on your midterms, everyone!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Sara! I really enjoyed reading your post, and your painting is absolutely beautiful! I love how you incorporated the oranges, yellows, and pinks from the sun throughout the background—it creates a sense of warmth that contrasts so beautifully with the cold winter scene. Your art is a wonderful example of how art can interpret nature in ways that go beyond simple description. While your painting includes some abstract elements, it feels even more “real” in a sense, as it conveys emotion and atmosphere more deeply than a one-to-one representation might. I can also tell how much time and effort you put into the details, which shows how art encourages us to slow down and truly observe and appreciate nature, rather than rushing through it.

I really appreciated your point about how we all bring our own perspectives to interpreting nature and creating art. In my own post, I mentioned that art is often like a “universal language” because it transcends differences in language and culture, making interpretation accessible to a wider audience. Sharing art allows us to share our unique perspectives on nature, and this exchange of viewpoints can broaden our understanding and inspire new ideas. It’s clear that art is an invaluable tool for nature interpretation, one that we should definitely explore and utilize more often.

Unit 4- The Art of Interpretation

Who am I to interpret nature through art? It’s a question that both humbles and motivates me. It humbles me because nature is vast, complex, and beyond any one person’s full understanding. But it also pushes me to contribute my own perspective, to engage with the landscape in a way that feels personal and meaningful.

Beauty is subjective, but how we interpret it matters. Rita Cantu once wrote, “If the songs are not sung and the stories are not told, danced, painted, or acted, our spirits will die as well.” This idea resonates with me—without creative expression, our connection to nature can fade into the background of daily life. Art, in any form, keeps that connection alive.

The Group of Seven captured this idea well, painting Canada’s landscapes with an energy that made them feel alive. Their work inspires me in my own occasional painting practice. For me, painting is more than just an artistic exercise—it’s a way to slow down and pay attention. It allows me to see nature differently, to engage with it rather than just pass through it.

I’ve always been drawn to trees, particularly how they change through the seasons. A bare winter tree standing against a blizzard isn’t just a cold, skeletal form—it’s a symbol of resilience. In spring, that same tree bursts with life, a reminder of renewal. Each season tells a different story, and painting those transformations helps me understand and appreciate them more deeply.

At its core, interpretation isn’t just about depicting beauty—it’s about helping others see it too. Whether through painting, writing, or simply noticing, we all have the ability to share our perspective and, in doing so, foster a deeper appreciation for the natural world.

So, who am I to interpret nature? I’m someone who takes the time to look, to listen, and to express what I see in my own way. And that’s all any of us can do. No single interpretation will ever capture the full essence of nature, but each perspective adds to the larger conversation.

Interpreting nature through art isn’t about getting it “right.” It’s about engaging with the world in a way that feels meaningful. Painting reminds me to pay attention, to notice the small details, and to appreciate the beauty that surrounds me. And if that appreciation inspires someone else to do the same, then the interpretation has done its job.

A recent painting of mine captures a tree in a blizzard, inspired by the current winter weather!

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prompt 4: Who are you to interpret nature through art? How do you interpret “the gift of beauty”? (Your readings – specifically Chapter 5 of the textbook – will be helpful for this!)

I don’t typically consider myself an artist. I’ve never been particularly skilled at drawing, painting, or other traditional visual art forms. However, we don’t need to be artists to appreciate and interpret art. Art is meant to evoke emotion in the viewer, spark discussion, and maintain interest. This makes it a powerful tool for interpreting nature. Nature-inspired art can help viewers feel more connected to the natural world by sparking emotional responses. Additionally, art can serve as an educational tool. For instance, a painting depicting countless tree stumps could effectively illustrate the devastating impact of mass deforestation. As a visual learner, I find that this approach is especially impactful for individuals like me.

Art is often called a “universal language,” one that transcends the barriers of spoken and written words. Beck et al. (2018) emphasize that cultural and language barriers can sometimes prevent minorities from fully accessing nature interpretation. Last week, we reflected on this and I realized that as a native English speaker, I have the privilege of easily understanding and accessing most forms of nature interpretation. However, I’ve also experienced moments when art, which transcends language, resonates with me more deeply than spoken descriptions.

It’s not enough to merely describe nature’s “gift of beauty.” The gift of beauty must be experienced—it must be felt (Beck et al., 2018). Art facilitates this by sparking emotion and offering a window into aspects of nature that we might not otherwise encounter. For example, while it may be unrealistic for someone to travel across the globe to witness a distant ecosystem, they could still experience its beauty through photographs or paintings. This accessibility is especially important for individuals with financial constraints, as it allows them to engage with the "gift of beauty" without the need for costly travel.

Earlier, I mentioned that I don’t typically consider myself an artist. I’d like to amend that statement. While it’s true that I don’t usually express my creativity through visual arts, there are many artistic ways to interpret nature beyond drawing or painting. Beck et al. (2018) highlight various art forms that can be used in interpretation, including theatre, music, dance, storytelling, and poetry. These forms can even be combined to create multimedia experiences (Beck et al., 2018). Though I may not use visual arts to express myself, I have certainly employed poetry and storytelling to share my emotions and perspectives.

So, who am I to interpret nature through art? I am a poet. To illustrate this, I’ve written a quick poem dedicated to the “gift of beauty” I have experienced in the Arboretum.

Through the quiet rustling of the leaves, Shaking contentedly in the wind, Lies a sanctuary of life and wonder, A heart of biodiversity. Can you hear it beating, As the crickets chirp for companionship? Can you see its warm glow shining, Through sunlit paths that stretch so long? Can you appreciate its gift of beauty? It’s waiting for you. — The Arboretum by Michelle Masood

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Rachel! I really enjoyed reading your post and appreciated how you incorporated your personal experiences with privilege and bias into the discussion. As a Zoology major, I can confirm that there’s often a strong emphasis on research that follows a Western perspective, both in how it’s conducted and published. While there are clear benefits to using peer-reviewed scientific studies, we need to recognize that these studies are often inaccessible—not only to readers but also to those attempting to publish. I recently came across an article in Nature (Heidt, 2023) that highlights how racial minorities frequently face discrimination and inequality in the publishing process, which I’ve linked below.

I also loved the example you shared about the Enji naagdowing Anishinaabe waadiziwin trail at the Royal Botanical Gardens. The quote from Joseph Pitawanakwat about how plants “speak to us” is incredibly profound. This proves the importance of embracing different approaches to nature interpretation, rather than defaulting to the familiar ones. Bias often stems from a lack of understanding, which is why learning about diverse perspectives is essential to breaking down prejudice.

In response to your question, our textbook offers several suggestions for making nature interpretation more inclusive. For example, interpreters can use multiple languages, including sign language, to improve accessibility (Beck et al., 2018). A more diverse staff can also help all visitors feel welcomed and represented (Beck et al., 2018). Reducing economic barriers whenever possible to encourage participation from a broader range of people is also recommended (Beck et al., 2018). Most importantly, we must strive to be welcoming, approachable, and well-informed when interacting with visitors, ensuring everyone feels valued and included.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore Publishing.

Heidt, A. (2023, April 28). Racial inequalities in journals highlighted in giant study. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-01457-4

Blog 3: Privilege in Nature Interpretation

After reading the content in unit 3, I think of privilege as the advantages or benefits afforded to individuals or groups based on characteristics such as race, gender, or socioeconomic status. These advantages often shape one’s experiences and opportunities, not from their abilities, competencies, decisions, or actions but rather from their position or social identity. In the context of nature interpretation, privilege may impact who has access to natural spaces and education, whose stories are told, and how these stories are framed.

Nature interpreters often reflect the dominant culture’s perspectives, privileging certain voices over others. For example, Indigenous peoples often find their knowledge overshadowed by Western scientific narratives. Privilege influences which stories are amplified, and this may result in a misrepresented interpretation of historic and cultural relationships with nature.

I have experienced this firsthand as a Wildlife Biology and Conservation major, where most classes focus solely on technical aspects and new research. While these are important, they often fail to incorporate Indigenous perspectives and knowledge. Why would this be important? I think incorporating Indigenous knowledge is essential for fostering a more holistic understanding of ecosystems, ensuring that our education is inclusive, teaches us about the history of our land, and is respectful of traditional ecological wisdom.

I worked at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Burlington, Ontario for two summers as a visitor experience representative. I had the privilege of having access to all the gardens, trails and visitor centres within the property. One of my favourite trails is called “Enji naagdowing Anishinaabe waadiziwin”, which translates to “The Journey to Anishinaabe Knowledge”. This trail, developed in partnership with the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, invites hikers to explore the connections between plants and Anishinaabe culture. Informative signs placed along the trail provide insight into how the Anishinaabe people traditionally used various plants for medicine, food, and cultural practices.

I admire the RBG’s commitment to incorporating Indigenous history, stories and ways of living into their interpretation. This approach goes beyond simply showcasing the beauty of the area, it helps to give a voice to the often overshadowed Indigenous peoples, and a meaningful platform for their important stories to be told.

The RBG website captures this idea by sharing the words of Joseph Pitawanakwat, a plant educator from Wikwemikong Unceded Nation:

“In my Anishinaabe culture and tradition, we teach that every plant is telling you a story, and in that story, the plant is teaching why it is here, its purpose — all we have to do is listen... Scientists are also testing Indigenous medicine plants and discovering active compounds that legitimize their use. As you walk this trail, you’ll see examples of how this works, some easy to spot, and some hidden in the plants.”

This quote highlights the importance of listening to not only plants, but also the wisdom of Indigenous communities, in order to deepen our understanding of the natural world and progress modern science.

Recognizing privilege in nature interpretation is important for ensuring equitable and accessible education for all. I encourage readers to reflect and answer the question: How can you actively work to dismantle privilege and ensure an equal platform for all in your nature interpretation career?

Royal Botanical Gardens. (n.d.). Indigenous plant medicines trail. Retrieved January 21, 2025, from https://www.rbg.ca/gardens-trails/by-attraction/trails/indigenous-trail/

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prompt 3: What role does “privilege” play in nature interpretation? Please include your working definition of privilege.

Close-up of a 'Check Your Privilege' sign at a Black Lives Matter rally in Austria. Photo by Ivan Radic, licensed under CC BY 2.0.