Text

If I had a nickel for every time a mortal rejected a god, I'd be richer than Midas. Which isn't a lot, but it's weird that it happened a lot.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doing feminist retelling on Phaedra because of the SA theme is a double edge sword.

Stay accurate to the source material means you are boringly following the play and not adding anything new.

Changing the story by omitting Phaedra’s actions means you are avoiding the challenge to think critically about SA and abuse toward male victims.

#tagamemnon#greek myth#greek mythology#phaedra#hippolyta#the fact that versions of Phaedra being genuinely complex exists but never shows up in retelling#clearly shows the authors didn’t do a lot of research

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

If we take dicitur[allusion] at face value, then, this ‘footnote’ could in all probability refer back to a Hellenistic source, a period where it is typical to encounter metamorphosis myths that function as aitia. In this vein, Ovid had already adopted similar ‘maiden-to-monster’ metamorphosis tales from literary precedents, so that his Scylla metamorphosis story is already found in an early Hellenistic elegiac poem that portrayed Scylla as a nymph that would only later transform into a sea monster. Likewise, the metamorphosis of the Sirens in Ovid is already to be found in the Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodes; they are introduced as formerly the young friends and custodians of Persephone, who would turn into anthropomorphic birds after her disappearance into Hades. An ur-source in this same era would make sense, where there was evidently an appetite for the grotesque.

Didn't have waifufication of monster girls on my bingo cards.

Oh hey a legit study on this.

Despite the obvious answer which the author quickly noted that Medusa was never said to be a priestess in the Metamorphoses, the author decided to explore why this peculiar part was a thing to begin with alongside the "yassification" of Medusa, and questions like why was she at Athena's temple to begin with.

#hellenistic and roman writers were monsterfuckers confirmed#interesting that it's also pointed that ovid didn't have io and hero as a priestess in his versions

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh hey a legit study on this.

Despite the obvious answer which the author quickly noted that Medusa was never said to be a priestess in the Metamorphoses, the author decided to explore why this peculiar part was a thing to begin with alongside the "yassification" of Medusa, and questions like why was she at Athena's temple to begin with.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh I'm aware, and the author has pulled Gnostic stuff with Mary Magdalene.

The problem here is more to do with the book say Yahweh and men are responsible for capitalism, violence, and his destructions are seen negative. But Asherah's flooding of the world was seen positive and was never questioned.

But more so is that Lilith and Jezebel team up to spread Asherah aka the Great Mother Goddess worship stemming out Yah's priests is also never questioned, despite doing the same thing Yah and his followers were doing. There's one instance of Lilith wanting to imprison a man and starve him for not wanting to bow before Jezebel and her husband (and this too is never questioned).

Someone in a discord server I’m in is going over the Lilith retelling book in the “read this so you don’t have to”.

And holy shit this is so much worse than I expected.

My expectations is zero to none, but did not expected this level of no awareness just by how misogynistic the book is despite championing feminism.

Some highlights:

Lilith turned into a serpent and has Eve eat the fruit to gain consciousness on the patriarchy. She does so and gain an attitude. Eve tries to get Adam to eat the fruit (cause it contained the mysteriesTM). Adam eats it and he doesn't inherited the p o w e r.

Lilith blaming Eve for not escaping the patriarchy

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

My god this has the worst heroine I ever seen in a retelling book. Lilith is suppose to be this “great feminist hero” who championed female rights and fight patriarchy.

But she:

Shit talked Eve and blames her for not escaping the abuse by Adam

Compare Noah’s daughters and daughter in laws suffer in labour to her own, saying they have it more painful cause they worshipped the wrong god (aka Yahweh and not the mother goddess Asherah)

Sad about men abusing women, but did nothing to stop it to Eve, Noah’s daughters, etc

Defend Asherah’s actions of flooding the world saying she’s doing it for greater good while Yahweh’s actions are bad????

Completely stupid and idiot through the book (she friend with Jezebel for 16 years and didn’t know she doesn’t have the mark of Asherah despite working as her bath attendant)

Again say Asherah would never ask for blood sacrifice and demands, ignoring flooding the world one time????

any marginal changes to her character (which is little to none tbh) are because of a man - her angel lover Samael and her son.

If any of you wondering if she does anything demonic or kill children of the sort, quick spoiler: no. Because those stories about her were slanders by mEn.

(not mine)

Someone in a discord server I’m in is going over the Lilith retelling book in the “read this so you don’t have to”.

And holy shit this is so much worse than I expected.

My expectations is zero to none, but did not expected this level of no awareness just by how misogynistic the book is despite championing feminism.

Some highlights:

Lilith turned into a serpent and has Eve eat the fruit to gain consciousness on the patriarchy. She does so and gain an attitude. Eve tries to get Adam to eat the fruit (cause it contained the mysteriesTM). Adam eats it and he doesn't inherited the p o w e r.

Lilith blaming Eve for not escaping the patriarchy

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sisterhood in context: a reassessment of Inanna's Descent

Unless either ancient aliens or creationism are involved, the general public has an at best limited interest in the literature of ancient Mesopotamia. It is thus quite surprising to see how commonly two specific passages from Inanna’s Descent - those in which Ereshkigal is addressed as the eponymous figure’s sister - seem to be repeated out of context in the least expected places. Elaborate explanations that the two were not only sisters, but in fact deities so closely related they are basically mirror images of each other, or perhaps even two parts of a greater whole, permeate the internet, and the world of Jungian literature. Arguably the most famous and commercially successful portrayal of both of them in modern fiction is based on this idea, too. Were Inanna and Ereshkigal really sisters in the first place, though? In one of my recent articles, I brought up that Alhena Gadotti expressed doubts over whether this statement can be taken literally. In this article I will try to demonstrate why she might be correct, and what that would mean for the interpretation of Inanna's Descent. I will investigate what the primary sources actually have to say about Ereshkigal’s family (or lack of it), and what circumstances could lead to someone being called a sibling c. 1800 BCE without actually being one. In order to demonstrate how the metaphorical use of kinship terms functioned, I’ll briefly summarize a case in which a nephew managed to legally oblige his maternal uncle to call him father, rather than brother.

The reception of Inanna’s Descent, from the 1800s BCE to the 2000s CE

As I already pointed out in the intro, Inanna’s Descent is probably one of the best known Mesopotamian myths. It was evidently reasonably popular when it was initially composed in the early second millennium BCE, too (Maurizio Viano, The Reception of Sumerian Literature in the Western Periphery, p. 79). The most recent survey I am aware of indicates that fifty-eight Old Babylonian (c. 2000 BCE - 1600 BCE) copies are known, most from Nippur and Ur. Furthermore, there is a single unusual Middle Babylonian (late second millennium BCE) copy, also from Nippur. It significantly postdates all of the other examples. It’s only an excerpt, though (specifically lines 26-35 - Inanna’s instructions for Ninshubur). The other side of the same tablet is instead inscribed with part of the god list An = Anum (The Reception…, p. 42-43).

In the first millennium BCE and Akkadian version arose. It is only known from three copies, with two coming from Assurbanipal’s library and one, slightly older, from Assur (Benjamin R. Foster, Before the Muses. An Anthology of Akkadian Literature, p. 498). It’s not a direct translation, and alters the plot to a significant degree (Dina Katz, The Image of The Nether World in Sumerian Sources, p. 260). It has been suggested that extracts such as the one discussed above had a role in its composition, though no copies of Inanna’s Descent actually date to the first millennium BCE (The Reception…, p. 43).

Inanna refers to Ereshkigal once as her “sister” (nin) and once as “older sister” (nin gal) at two different points early on in the narrative (Anna Jordanova, Untersuchungen zur Gestalt einer Unterweltsgöttin: Ereškigal nach den sumerischen und akkadischen Quellentexten, p. 40):

Ereshkigal is then technically addressed as Inanna’s sister once more by the doorman quoting her words afterwards.

These two specific lines are one of the main reasons why today Inanna’s Descent holds the questionable distinction of being regularly tormented with questionable interpretations more than the overwhelming majority of widely available Mesopotamian literary texts. The most notable contributors to this state of affairs were undeniably the devotees of Carl Jung. All the way back in 1949 Jungian par excellence, Joseph Campbell, boldly proclaimed in The Hero with a Thousand Faces that “Inanna and Ereshkigal, the two sisters, light and dark respectively, together represent, according to the antique manner of symbolization, the one goddess in two aspects” (p. 89). Note that Samuel N. Kramer’s original translation of Inanna’s Descent - Inanna’s Descent to the Nether World. The Sumerian Version of Ištar’s Descent from 1937 (followed up with Ishtar in the Nether World According to a New Sumerian Text in 1940) - was still pretty recent back then. The myth thus was besieged by questionable interpretations almost right from the start.

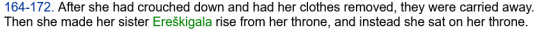

By the 1980s, the Jungian (mis)interpretation of the myth was well established enough to be the topic of entire books on its own. The most notable example is Sylvia Brinton Perera’s Descent to the Goddess: A Way of Initiation for Women. I feel obliged to point out right away that the photo on the cover isn’t Inanna; in fact, it’s not a Mesopotamian work of art at all, but rather a votive figurine from Susa in Elam (the southwest of modern Iran), specifically SB 7799 from the Louvre’s collection. The proportions are usually less exaggerated, as you can see on this example from the MET’s collection.

The author describes Inanna’s Descent as a work from “an age when the Great Goddess was still vital” (Descent to the Goddess…, p. 10). She promptly declares that since Ereshkigal is addressed as Inanna’s sister, “she is her shadow, or complement: together the two goddesses make the bipolar wholeness pattern of the archetypal feminine mother-daughter biunity of the Great Goddess” (Descent to the Goddess…, p. 43-44). She also claims Ereshkigal was originally a grain goddess and that she is identical with Ninlil (Descent to the Goddess…, p. 21) and inexplicably compares her with Kali and Medusa (Descent to the Goddess…, p. 33). While this is beyond the scope of this article, she also delivers probably the worst, most uninformed take on Ninshubur I’ve ever seen (Descent to the Goddess…, p. 63-64), discussing which however is beyond the scope of this article. I suppose some books can in fact be judged by their covers. Regrettably, another book from the 1980s which propagated similar ideas attaches them to probably the single most popular edition of Inanna’s Descent. In Samuel N. Kramer’s and Diane Wolkstein’s Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: her Stories and Hymns from Sumer one can learn that Ereshkigal is “the other, neglected side of Inanna” (Inanna, Queen…, p. 158). Note that Kramer cannot be blamed for that baffling statement. It’s entirely on Wolkstein, who was not an Assyriologist and by own admission was convinced Inanna is a moon goddess (Inanna, Queen…, p. XV). While there are individual aspects of Kramer’s scholarship I take issue with, it needs to be stressed that, by his own admission, his interpretations of the texts he studied were rudimentary and tentative (to be fair, in part because there genuinely wasn’t much to fall back on when he started), and he hoped other authors will elaborate upon them or provide better proposals outright (Jerrold S. Cooper, Was Uruk the First Sumerian City?, p. 53). I used to be very critical of him for a time, but it is clear to me now that he was well aware of own shortcomings. It’s also hard to deny that he had a unique talent at making the general public aware of his findings. It’s just that in this specific case it apparently backfired on him, and his honest work was used to promote ideas of dubious validity at best.

Jungian ideas also found their way into a tome which my regular audience probably needs no introduction to, Barbara G. Walker’s The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets, which refers to Ereshkigal both as an “Underworld counterpart” (p. 282), “dark alter ego” (p. 698) and “twin” (p. 452) of Ishtar (and for good measure treats them as analogs of Kore and Persephone, somehow; p. 8). Even if you aren’t familiar with this book, multiple game developers evidently are (for instance Fate’s “occult consultant” Kiyomune Miwa; see here for an example of a Walker-fueled rampage, and here for a translation), and eagerly make use of it.

Jungian authors, and probably Walker in particular, are thus quite likely why arguably the most popular modern takes on both Ishtar and Ereshkigal are palette swaps of each other from a gacha game:

Supplementary materials assert that they are “a divinity with the same attributes split into two”, “two alternate yet inseparable sides” (sic).

On a more lofty note, Jungian interpretations also influenced a novel by the Nobel Prize in Literature laureate Olga Tokarczuk, Anna In w Grobowcach Świata (“Anna In in the Catacombs of the World”; as you can imagine, the name of the protagonist is a pun on Inanna). In particular, the plot, at least to me, seems to echo Sylvia Brinton Perera’s bizarre lament about Ninhursag’s absence from the myth (Descent to the Goddess…, p. 64; unclear to me why she’s not lamenting the absence of, say, Dagan or Ishtaran or Belet Nagar). The novel is not translated into English, but I honestly don’t think the international audience is missing out. While the acclaim the author enjoys is warranted (The Books of Jacob in particular is excellent, if you are willing to commit to a 900 pages long tome), this is not her finest work, to put it lightly (which pains me to say since it’s also the only modern adaptation which indicates some genuine familiarity with Ninshubur).

However, Jungians are hardly the only group to develop questionable ideas based on two lines from a single text and its loose adaptation. Authors associated with the Helsinki school of Assyriology seems to present them not only as fundamentally two hypostases of the same goddess, but also as a representation of duality between a “sinful soul” and “purified soul”, with the controversial and not particularly representative Burney Relief held to be a depiction of them both at once, somehow (Pirjo Lapinkivi, The Neo-Assyrian Myth of Ištar’s Descent and Resurrection, p. 48-49; stay tuned for a separate article explaining why the Burney Relief should be treated as a curiosity at best). And they’re somehow gnostic Sophia in the end ( The Neo-Assyrian…, p. 77; part of this page appears to be straight up copy pasted from p. 49-49).

It needs to be stressed this is considered a controversial product of flawed methodology at the absolute best (Alhena Gadotti, ‘Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld’ and the Sumerian Gilgamesh Cycle, p. 13; Wiebke Meinhold, Pirjo Lapinkivi, The Neo-Assyrian Myth of Ištar’s Descent and Resurrection (review), p. 118-119, with references to earlier literature; note in particular the criticism of the Burney Relief interpretation). All of this effectively goes back to efforts to validate the personal faux-gnostic, faux-tantric beliefs of a single author, Simo Parpola (see Jerrold Cooper, Assyrian Prophecies, the Assyrian Tree, and the Mesopotamian Origins of Jewish Monotheism, Greek Philosophy, Christian Theology, Gnosticism, and Much More). The subject of such inquiries has been mockingly described as a fabricated “Ishtar of Helsinki” detached from actual study of primary sources and their reception (Julia M. Assante, Bad Girls and Kinky Boys? The Modern Prostituting of Ishtar, Her Clergy and Her Cults, p. 49; see here under “Sexualization of lamenting” for my reservations about other aspects of this article, though, and note Assante herself became a promoter of fringe spiritual ideas later and it seems her only notable recent accomplishment is getting a page on RationalWiki, which indicates she believes in ectoplasm).

Even credible authors take the supposed sisterhood, and its alleged centrality to Mesopotamian thought, for granted quite often. To use just two examples: Julia Krul sees the presence of Ereshkigal in the pantheon of Uruk in the Seleucid period as a reflection of this connection (“Prayers from Him Who Is Unable to Make Offerings”: The Cult of Bēlet-ṣēri at Late Babylonian Uruk, p. 75)... However, Ereshkigal was actually worshiped there first in association with Nergal, as documented in Neo-Babylonian sources (Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period, p. 297) and then Belet-seri, as Krul points out herself (Prayers from Him…, p. 62-63).

Aleksandra Kubiak-Schneider inexplicably refers to Ereshkigal as a sister of Shamash (Hatra of Shamash. How to Assign the City Under the Divine Power?, p. 799), which can only be explained as a syllogism based on his well documented status as a brother of Ishtar… and the isolated reference to the latter being a sister of Ereshkigal. Note Ereshkigal is actually not mentioned in the source given by Kubiak-Schneider (Marco Moriggi, A Corpus of Syriac Incantation Bowls. Syriac Magical Texts from Late-Antique Mesopotamia)… Note that my goal wasn’t to claim Krul or Kubiak-Schneider are unreliable - if you keep track of my wikipedia endeavors, the former in particular is basically one of my to-go sources on Uruk. I merely want to illustrate how firmly entrenched this idea is in scholarship.

Skepticism is not entirely unheard of, though. As I already said, this article was directly inspired by Alhena Gadotti’s offhand comment: “[Inanna’s Descent] indicates that she [Ereshkigal] was Inana’s sister, but whether this is merely a title or a kinship term is unclear” (Gilgamesh, Enkidu…, p. 13). At first, I was worried that this might be an entirely isolated view. However, a survey of relevant publications revealed that Gadotti is actually not alone in her doubts. Essentially the same conclusion was reached by Anna Jordanova, who depended on an earlier study by Erica Reiner (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 418).

Reiner, as far as I can tell, was the first person who suggested that the use of the term “sister” might not be literal, but rather reflect the use of kinship terms in diplomacy - to call someone a “brother” or “sister” in this context was to call them an equal (Your Thwarts in Pieces, Your Mooring Rope Cut. Poetry from Babylonia and Assyria, p. 37). While she depended on the late Akkadian adaptation of Inanna’s Descent, as opposed to the text this article focuses on, Jordanova notes that the point is applicable to the original too (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 40-41). The objective of the rest of this article will be to evaluate how likely it is that Reiner, and the few authors who followed in her footsteps, are correct. As I promised, to that end I’ll investigate what primary sources have to say about Ereshkigal’s genealogy, how common the use of kinship terms as titles was, in particular in the time period when Inanna’s Descent came to be, and finally if it is attested in the case of deities, and Inanna and Ereshkigal in particular.

Finally, I will offer my own proposal for a reassessment of this section of the myth. Not a retranslation let alone new restoration, mind you - that, as far as I am aware, is not necessary.

Ereshkigal and her peers

Since I wrote a few paragraphs about the history of Ereshkigal in another article earlier this year, I won’t repeat myself here for the most part, and will move straight to the point. If by some miracle you are reading one of my Mesopotamia articles and don’t recognize her, you can find the basics here, under A crash course in Ereshkigal’s career, from Early Dynastic Lagash to Seleucid Uruk, with sources provided. Ereshkigal’s genealogy is unclear at best. No source actually addresses her directly as a daughter of another deity (Alhena Gadotti, Never Truly Hers: Ereškigal’s Dowry and the Rulership of the Netherworld, p. 15).

In contrast, Inanna’s parentage is remarkably standardized - she is consistently recognized as a daughter of Sin (Nanna) and Ningal, regardless of the language of the text and time period (The Pantheon…, p. 111; Julia M. Asher-Greve, Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, p. 230). As a matter of fact, she is directly referred to as “Sin’s daughter” even in the Akkadian adaptation of the discussed myth basically right off the bat, in line 2 (Your Thwarts…, p. 34). The most extensive monograph on Sin currently available, Aino Hätinen’s The Moon God Sîn in Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian Times doesn’t mention Ereshkigal at all in the section The Family and Household of Sîn (p. 289-329) - or anywhere, else, for that matter, she’s not even in the index (p. 613-620), which indicates there’s no meaningful connection between them to speak of. A quick survey of Mark G. Hall’s earlier A Study of the Sumerian Moon God, Nanna/Suen also reveals no traces of Ereshkigal in a similar chapter (The Relationship of Nanna/Suen to Other Deities in the Pantheon: Genealogy and Cultic Ties, p. 721-754).

There’s thus no reason to undermine one of the points Jordanova makes: no indication of any familial connection between Inanna and Ereshkigal exists outside of the isolated lines from Inanna’s Descent and its later adaptation (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 40).

While Ereshkigal’s genealogy remains undefined, multiple literary texts preserve references to marital relations between her and other deities (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 506). Gugalanna, who plays the role of her husband in Inanna’s Descent, will be discussed later in his own section.

Nergal on a cylinder seal from the early second millennium BCE (wikimedia commons)

As documented in the relatively well known myth Nergal and Ereshkigal, Ereshkigal could be paired with Nergal. However, this was a relatively late tradition. It probably developed at some point between the late Old Babylonian period and the Middle Babylonian period (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 287). Furthermore, they were not recognized as husband and wife consistently. Ereshkigal wasn’t even the goddess most commonly regarded as Nergal’s wife. That distinction instead belongs to Laṣ (Frans A. M. Wiggermann, Nergal A. Philological in RlA vol. 9, p. 219-220).

Ninazu could be inconsistently described as either the son of Ereshkigal or, in incantations, as her husband (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 226). Jordanova argues that in a single first millennium BCE formula he might be implicitly understood as the son of Nergal and Ereshkigal (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 231). It’s possible that Ereshkigal was initially basically a replacement for him as the deity of the underworld, though (Goddesses in Context…, p. 19). Furthermore, a distinct tradition provided him with a completely different parentage, rendering him entirely unrelated to Ereshkigal (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 229-230). Furthermore, starting in the Ur III period, and especially from the Old Babylonian period onwards, Ninazu was usually paired with Ningirida, as documented in multiple genres of texts (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 232).

Nungal, the goddess of prisons, is described as Ereshkigal’s daughter in the hymn Nungal A, with Anu addressed as her father (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 374-375).

Ereshkigal’s court is elaborated upon in multiple sources, too. Her arguably most commonly mentioned servant was Namtar (ironically missing from Inanna’s Descent, though present in a major role in the Akkadian adaptation). He’s consistently designated as her “vizier” (sukkal). His entire family seems to be in Ereshkigal’s employ, too. In the god list An = Anum, his mother Mardula’anki is listed as Ereshkigal’s advisor (with an additional note describing her as a “rodent”); his wife Hushbisha and daughter Hedimmeku are there too (Wilfred G. Lambert, Ryan D. Winters, An = Anum and Related Lists, p. 196). A single source - the incantation series Utukkū Lemnūtu - makes Namtar a son of Ereshkigal and Enlil (sic) instead of a servant (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 260-262). Next to Namtar, the deity with arguably the strongest claim to a “professional” bond with Ereshkigal is Belet-seri. Probably the most famous passage involving her can be found on tablet XII of the Standard Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh (Prayers from Him…, p. 52; I really like a-gnosis’ illustration of this passage):

It’s possible that her portrayal in literary texts reflects a role analogous to that of a king’s personal secretary (ṭupšar ekalli; Prayers from Him…, p. 51-52). Furthermore, the fact Ereshkigal is aided by a female scribe (instead of just making Namtar do overtime) might be a reflection of historical reality in its own right, as evidence from Old Babylonian Mari and Sippar and Neo-Assyrian Nineveh and Kalhu seems to indicate it was customary for high-ranking women to employ female clerks (Andrew R. George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts, p. 483). Julia Krul suggests that by the Seleucid period Belet-seri might have started to be perceived as Ereshkigal’s “vizier” (thus effectively replacing Namtar), though there is no direct evidence for this. On the other hand, it does seem that she was portrayed in an intercessory role (Prayers from Him…, p. 76), as far as I can tell in contrast with Namtar, in spite of his title which in theory did have similar implications. A few other attested servants of Ereshkigal include Mutu (“death”), designated as an advisor (An = Anum…, p. 196); Bitu, the doorkeeper from Inanna’s Descent and other literary texts (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 266-267); and the cleaners Qāssu-tābat und Ninšuluḫa (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 342).

A peculiar inclusion in An = Anum’s Ereshkigal section is Allatum. She is explained simply as an alternate name of Ereshkigal herself - only one of multiple, at that (An = Anum…, p. 23-24). However, she originated as a distinct goddess, Allani (“the lady”), who fulfilled an analogous function to Ereshkigal in the Hurrian pantheon. She was first introduced to lower Mesopotamia in the Ur III period (c. 2100 BCE), possibly from the Diyala area (Tonia Sharlach, Foreign Influences on the Religion of the Ur III Court. p. 99). She was still worshiped as a distinct deity in Old Babylonian Nippur (Foreign Influences…, p. 100).

Can the real Gugalanna please stand up?

Gugalanna requires a separate section, in part because of an oddly persistent misconception which I feel obliged to clear up, in part because he’s relevant for the passage this article revolves around.

I’ll start with the misconception: the idea that Gugalanna is one and the same as the Bull of Heaven is oddly widespread online, seemingly just because of the meaning of his name (“great bull of heaven”). It’s repeated on most of the shoddy pop-history resources such as World History Encyclopedia, for instance. Various new age, neopagan and fringe christian websites do so too; here is just one example, labeled as an “apocryphal myth” in order to give it unwarranted legitimacy (whenever i post something particularly incomprehensible like "the easiest solution to the Birtum gender conundrum is that we're dealing with world's first he/him lesbian" know it is actually an "apocryphal myth"). Outside of Inanna’s Descent, Gugalanna is attested only in the god list An = Anum (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 366). He appears immediately after Ereshkigal herself (tablet V, line 199), though he’s absent from the Old Babylonian forerunner (An = Anum…, p. 24). It should be noted that going by this source Gugalanna’s supposed bovine credentials are up for debate - in contrast with Inanna’s Descent the spelling of his name there doesn’t use the sign gu, “bull”, but rather one of its homophones. The compound gugal would thus mean not “great bull”, but rather “canal inspector”, making him “the canal inspector of heaven” (or “of the god Anu”). It’s entirely possible that the “bovine” variant “great bull of heaven” was only a folk etymology (Dietz Otto Edzard, Gugalʾana in RlA vol. 3, p. 694).

Impression of a Middle Assyrian (c. 1200 BCE) seal with a winged bull (wikimedia commons)

The bull of heaven (GU.AN.NA = alû), meanwhile, has plenty of attestations. However, this name does not refer to a god in the first place, but merely to a constellation - the forerunner of Taurus (Andrew R. George, Manfred Krebernik, Two Remarkable Vocabularies: Amorite-Akkadian Bilinguals!, p. 119). Or at least of a part of Taurus, since the northern stars counted as a part of it formed a separate constellations in Mesopotamian astronomy, the Chariot (Hermann Hunger, David Pingree, Astral Sciences in Mesopotamia, p. 271). The perception of the Bull of Heaven as a constellation is directly reflected in the standalone Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven already, as evident especially in the passage describing the creature grazing in the sky (Andrew R. George, The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts, p. 11).

Andrew R. George’s seminal monograph on the Epic of Gilgamesh doesn’t even feature Gugalanna in the index (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 951-961; I went through every single page mentioned under “Bull of Heaven” to confirm Gugalanna isn’t hiding somewhere in there). As far as I am aware, neither does Sophus Helle’s more recent but less extensive commentary on the same classic. It’s not exactly hard to find articles where the two are discussed as entirely separate figures, too (ex. Uri Gabbay, Drums, Hearts, Bulls, and Dead Gods: The Theology of the Ancient Mesopotamian Kettledrum, p. 34). The only relatively recent publication to present Gugalanna and the Bull of Heaven as one and the same - without full conviction, to be entirely fair - appears to be Louise M. Pryke’s 2017 pop-history book Ishtar (p. 107). There are no sources provided; the fact that on the very same page Pryke appears to be unaware Neti is a misreading, and that Ereshkigal’s doorkeeper is actually named Bitu (as first suggested in the early 1980s; Michael P. Streck, Divine door-keepers A. In Mesopotamia in RlA vol. 14, p. 163), doesn’t exactly fill one with optimism. It would be fine for a layperson to be mistaken, especially since ETCSL still has “Neti” in Inanna’s Descent due to the site’s age, but the author isn’t a layperson in this case.

I had to go back to the late 1990s to find another claim that Gugalanna was one and the same as the bull of heaven in an academic publication. Nicolas Wyatt outright referred to the creature defeated by Gilgamesh as Gugalanna and as husband of Ereshkigal, without providing a source for this claim (Calf in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, p. 181). This might simply be a mistake based on the phonetic similarity between the names - Wyatt specializes in Ugarit, not Mesopotamia, and the editors of the dictionary this entry was published in aren’t Assyriologists either.

Perhaps the most perplexing paper supporting equating Gugalanna and the Bull of Heaven has been written in 1986 by Tzvi Abusch (you might remember him from my article about Inanna and gender; check under Maternal obsessions: do deities even follow gender roles?) who, to put it bluntly, appears to fantasize about carnal relations between the Bull of Heaven and both Ereshkigal and Inanna. In the same passage he also boldly declares not only Ereshkigal AND Inanna, but also Circe and Calypso (sic) were “death goddesses”, to give you an idea what sort of paper we are dealing with (Ishtar's Proposal and Gilgamesh's Refusal: An Interpretation of "The Gilgamesh Epic", Tablet 6, Lines 1-79, p. 161). However, Abusch’s ideas about the Epic of Gilgamesh, in contrast with his studies on Maqlu (which are perfectly fine, though I prefer Daniel Schwemer and Markham J. Geller when it comes to exorcistic literature) are not exactly taken seriously by other Assyriologists (Gary Beckman, Male and Female in the Epic of Gilgamesh: Encounters, Literary History, and Interpretation by Tzvi Abusch [review], p. 902; The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 471 for a criticism of the passage under discussion). The only positive evaluation from within the past 20 years I’m aware of comes from Pirjo Lapinkivi (The Neo-Assyrian Myth…, p. 48), whose work is itself at best controversial (see Meinhold’s review linked earlier).

Given the nature of the majority of publications equating Gugalanna with the Bull of Heaven, I think it is safe to conclude that there is no merit in this claim. However, the inquiry cannot stop here. The idea that Gugalanna is not a distinct god, but merely a title of some other deity, is fairly widespread (ex. The Image of The Nether World…, p. 440). A contributing factor is the fact that in Inanna’s Descent the name is written without the determinative used to designate names of deities, which makes it appear more like a title than a proper name (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 276). Accordingly, numerous possible identities have been proposed.

Surprisingly, I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone online citing the only proposal Jeremy Black and Anthony Green opted to include in Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. An Illustrated Dictionary, even though it’s an accessible work aimed at general audiences. They suggest that Gugalanna might have been identical with the minor god Ennugi, following the assumption that the “canal inspector” version of the name was the original, and thus the best indicator of his character (p. 77).

Ennugi certainly is an interesting option, as he was an underworld deity himself, as indicated by the meaning of his name, “lord of no return”. On top of that, he appears in association with Ereshkigal (though as a servant - specifically a doorkeeper - not spouse) in Nergal and Ereshkigal and, under the variant name Ennugigi, in An = Anum (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 335). However, his canal-inspecting qualifications, on which the identification with Gugalanna ultimately rests in his case, are up for debate. The key passage supposedly attesting to them, which originates in Atrahasis but is best known from its partial adaptation from the Standard Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, might be the result of textual corruption, with gallu, a designation of an (underworld) constable, accidentally turned into gugallu, ie. “canal inspector” (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 879).

This uncertainty probably explains why the possibility of Ennugi being Gugalanna is not addressed in most of the few subsequent studies dealing with one or both of them. Jordanova’s is an exception (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 277). However, ultimately she only accepts the assumption that “canal inspector of heaven” was likely the original meaning of Gugalanna’s name, and that his identity is to be sought among weather and irrigation deities (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 366). She also notes an apparent connection between Ishkur (the original weather god par excellence) and the underworld can be found in an Early Dynastic myth (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 369), but that’s beyond the scope of this article. I might return to this point in the future, though.

An alternate proposal is that Gugalanna might have been a title of Tishpak, the tutelary god of Eshnunna, though the evidence is pretty weak. In the Old Babylonian predecessor of An = Anum, Tishpak follows Ereshkigal and Allatum and precedes Namtar’s family. He is thus placed roughly where Gugalanna is in the later revised and expanded edition of the list. However, he isn’t particularly closely linked with Ereshkigal anywhere else (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 92). Furthermore, as per the most recent edition of the text, it seems he is actually followed by his usual wife anyway (An = Anum…, p. 50).

A further proposed identification has been rendered entirely implausible by the 2000s, but is worth bringing up here for historical reasons and to further stress there was never really a widespread Assyriological consensus that Gugalanna is literally a bull, let alone the Bull of Heaven. In the 1980s Wilfred G. Lambert suggested that he was identical with the minor underworld god Alla. He based this hypothesis on the assumption that Allatum was only ever an alternate name of Ereshkigal. At the time this was a relatively sound proposal - Allatum’s name does look like Alla with an Akkadian feminine ending added (something like “Mrs. Alla”), and couples of deities with matching names are not unparalleled (cf. Wer and Wertum). Furthermore, Alla is one of the few gods regularly portrayed as dying (specifically as the source of raw materials for the creation of mankind), which Lambert assumed could be what’s being referenced in Inanna’s Descent (Theology of Death, p. 63-64). However, as I already noted before, it is now certain that Allatum was a distinct goddess in origin - and in particular that she had nothing to do with Alla (Tonia Sharlach, An Ox of One's Own: Royal Wives and Religion at the Court of the Third Dynasty of Ur, p. 264). Alhena Gadotti quite boldly suggests interpreting Gugalanna as one of the multiple bovine epithets of Nergal. She points out that he was already called Guanungia, “bull whose might cannot be opposed”, in the Early Dynastic period, and that the earliest written form of his name used the early cuneiform sign ZATU 219 - a schematic representation of the head of a bull (Never Truly Hers…, p. 15).

However, in an earlier assessment of the discussed passage of Inanna’s Descent Manfred Hutter concluded that nothing not only in the myth itself, but in Old Babylonian literature in general, indicates that a connection between Ereshkigal and Nergal already existed in the early second millennium BCE (Altorientalische Vorstellungen von der Unterwelt: Literar- und religionsgeschichtliche Überlegungen zu “Nergal und Ereškigal”, p. 56). Dina Katz has also rejected the interpretation of Gugalanna as Nergal, though entirely based on the mistaken assumption that he wasn’t perceived as a god associated with the underworld yet in the second millennium BCE (Inanna’s Descent and Undressing the Dead as a Divine Law, p. 230). In reality, the Zame Hymns from the third millennium BCE already assign this role to him and refer to his cult center Kutha as the “residence of the netherworld’s god” (Manfred Krebernik, Jan J. W. Lisman, The Sumerian Zame Hymns from Tell Abū Ṣalābīḫ With an Appendix on the Early Dynastic Colophons, p. 107).

Still, even if the identification with Nergal is unsustainable, Gadotti raises a second interesting point - nothing in the passage indicates that Inanna is necessarily saying the truth. In other words, in the context of this specific myth, Ereshkigal might very well not have a husband named Gugalanna, let alone a dead husband named so; at the absolute minimum, there’s definitely no funeral happening (Never Truly Hers…, p. 15). Similar observations have been made by Anna Jordanova. She points out that only Inanna mentions Gugalanna, Ereshkigal does not. Furthermore, while the myth later does affirm that she is experiencing great sadness, nothing she says indicates it has anything to do with a deceased husband (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 275).

Kinship terms in diplomatic language and beyond, or how to become a sibling

With Ereshkigal’s family connections now fully explained, it’s time to move on to the second major topic which will require some explanation. As I already mentioned, Erica Reiner was seemingly the first author to suggest that she is only designated as a “sister” metaphorically. Some historical context will be necessary to explain where this idea even came from.

As early as in the third millennium BCE, kinship terms could be applied metaphorically. Through their use the idealized image of a family was wishfully projected onto other relationships (Amanda H. Podany, Brotherhood of Kings. How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East, p. 29).

A damaged statue of an unidentified Eblaite ruler (wikimedia commons) The very first diplomatic letter presently known, sent by a certain Ibubu, an official in the court of Irkab-Damu of Ebla, to an envoy of Hamazi, a kingdom most likely located in the northeast of Mesopotamia, already uses formulas evoking this idea: “I am (your) brother and you are (my) brother”, he reassures the other party. However, in all due likeness it was not the oldest letter ever sent - Ibubu was relying on a convention which must have been known to both his fellow Eblaites and to people of Hamazi (Brotherhood of Kings…, p. 27). Presumably a similar sentiment is expressed in inscriptions of Enmetena of Lagash in which a non-aggression pact of sorts between him and his neighbor Lugalkiginedudu of Uruk is referred to as “brotherhood” (Brotherhood of Kings…, p. 33).

A fresco depicting Zimri-Lim in the company of deities during his investiture (wikimedia commons) While the earliest evidence is ultimately incredibly fragmentary, the Old Babylonian period offers much more numerous and better preserved sources (Brotherhood of Kings…, p. 71). A treasure trove of evidence for how diplomacy was conducted, and what terminology was employed to that end, can be found in texts from the archive discovered in the palace of Zimri-Lim of Mari (Brotherhood of Kings…, p. 69-70). The core principle known from earlier sources was still intact: an equal could be referred to as a brother. Furthermore, a ruler of a superior status was referred to as father, one of inferior status as a son (Brotherhood of Kings…, p. 70). While uncommon, cases where the ruler of one kingdom would recognize multiple other ones as fathers are attested for example in Emar and Carchemish (Nathan Wasserman, Yigal Bloch, The Amorites. A Political History of Mesopotamia in the Early Second Millennium BCE, p. 391). The term used to designate a head of state could also change due to the loss of prestige of a kingdom. For instance, Aplaḫanda of Carchemish and Zimri-Lim referred to each other as brothers. However, Aplaḫanda’s successor Yatar-Ammī was only recognized by the king of Mari as a son - a king of inferior status. This reflected the loss of influence of the kingdom (The Amorites…, p. 391).

Old Babylonian texts from Mari indicate the existence of specific ceremonial ways to establish a bond of political “brotherhood” (atḫūtum) or “blood relation” (dāmum), such as sacrificing a donkey foal (The Amorites..., p. 58). Swearing an oath with gods acting as witnesses was an option too, as evident in a letter sent to the most famous Old Babylonian king of Mari, Zimri-Lim, by his ally from Niḫriya, a kingdom located on the Balikh River (The Amorites…, p. 71).

Note that establishing bonds of brotherhood with one political entity didn’t automatically mean all of its own bonds were transferred as well. For instance, two Amorite confederations inhabiting the Sinjar Mountains in the times of Zimri-Lim, Numḫā and Yamutbal, established such a bond with Simʾalites (the confederation Zimri-Lim’s family originated in) - but simultaneously considered each other bitter enemies, not brothers (The Amorites…, p. 69-70).

There are also cases where a ruler could claim to be another’s brother without actually establishing a bond with him. This was considered a grave insult. For instance, at one point Zimri-Lim petitioned Yarim-Lin I of Yamhad to do something about one of his subordinates, Dādī-ḫadun, who started calling himself and Zimri-Lim brothers, despite evidently not being his equal. Yarim-Lin I agreed with Zimri-Lim, and instructed Dādī-ḫadun to refer to him as father rather than brother, in accordance with their respective status. Interestingly, it was seemingly entirely irrelevant in this context that Dādī-ḫadun was Zimri-Lim’s maternal uncle - hard to think of a better indication how the diplomatic bonds, despite borrowing kinship terminology, were ultimately distinct (The Amorites…, p. 382-383).

While I focused on kinship terminology in a diplomatic context, it should be stressed that it was applied metaphorically to many aspects of life. A respected expert in a given field was referred to as “father” by other members of the same profession, for instance. Business partners could call each other “brothers” in order to assure each other they are reliable. A trusted friend could be a metaphorical brother, too (Brotherhood of Kings…, p. 29).

There are even examples of love poetry where kinship terminology is applied metaphorically (Frans Wiggermann, Sexuality A. In Mesopotamia in RlA vol. 12, p. 416). Despite the implications such statements might have from a modern perspective, actual incest was a strong taboo - to the point even divine genealogy was sometimes subject of scrutiny to avoid implications of it. That might have been the original purpose behind providing some gods - especially Enlil - with ridiculously extensive family trees (Wilfred G. Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 389). The most extensive example furnishes him with 21(!) generations of ancestors (Babylonian Creation…, p. 409). Of course, demonstrating how widespread the metaphorical use of kinship terms was among the historical inhabitants of Mesopotamia doesn’t automatically prove that the same applies to gods. Even though the earliest religious sources already reflect a pantheon which is “hierarchical, well organized and geographically inclusive” (Jerrold S. Cooper, Enki and the World Order. A Sumerian Myth, p. 3) and it is certain that gods were supposed to be bound by similar familial connections as humans (Brotherhood of Kings…, p. 28-29), they were not necessarily expected to follow social conventions, as well documented for the case of gender roles (Ilona Zsolnay, Do Divine Structures of Gender Mirror Mortal Structures of Gender?, p. 116).

Luckily, the evidence for metaphorical use of kinship terms in regards to gods is abundant too. Both “father” and “mother” are attested as epithets of deities - either as a designation of their status as a major member of the pantheon, or as a tutelary deity of a specific city, as in the case of, say, Ninura in Umma (Goddesses in Context…, p. 139-140). Notably, the application of “mother” as an epithet was completely detached from a deity’s connection with motherhood or lack of it (Jeremy Black, Songs of the Goddess Aruru, p. 48). One of the most curious examples of this phenomenon might be a hymn in which Inanna addresses Ninshubur as her “mother” as a display of endearment (Frans A. M. Wiggermann, Nin-šubur in RlA vol. 9, p. 497).

Enki and the World Order (a composition I’ll return to later in this article) labels Enki as son of Enlil to indicate his status as an underling (nubanda, “lieutenant”), rather than his genealogy (Enki and…, p. 10). The Poem of the Mattock (or The Song of the Hoe as per the ETCSL translation) refers to Gilgamesh metaphorically as the younger brother of Nergal in order to highlight his own role in the underworld, despite also bringing up his well established parentage fundamentally incompatible with a literal interpretation of this statement (The Babylonian Gilgamesh…, p. 107-108). An entire paper has been dedicated to the use of the title “brother” in the Baal Cycle from Ugarit (Aaron Tungendhaft, How to Become a Brother in the Bronze Age: An Inquiry into the Representation of Politics in Ugaritic Myth; the author regrettably leaves out the situation between Baal and Anat, though) - which, like Mesopotamia c. 1800 BCE, pretty firmly belonged to the spectrum of Amorite-influenced cultures (Mary E. Buck, The Amorite Dynasty of Ugarit. Historical Implications of Linguistic and Archaeological Parallels, p. 262)

Conclusions: is it really about sisterhood?

The evidence gathered in the preceding section is by no means complete - dozens upon dozens of texts would have to be analyzed to provide every single instance of a deity or another literary character utilizing kinship terms metaphorically. If we add diplomatic texts, private letters, and other genres where such formulas were regularly used by rulers and ordinary people, the number would in all due likeness go up to thousands. Still, I hope the relatively small sample I provided illustrates that Reiner’s and Jordanova’s arguments (and Gadotti’s suspicion) rest on a sound foundation. While it is a minority position, I do think it’s sensible to assume that

What was the rationale for employing these formulas in Inanna’s Descent, though? And why the change between “older sister” and just “sister”? Jordanova argues that Inanna refers to Ereshkigal as her older sister when she bangs at her door because in the beginning of the narrative her status is lower; when she switches to calling her just “sister” instead, the intent is to show that she aims to make them equal by usurping Ereshkigal’s position - which she temporarily does in the very same passage (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 40-41). She also points out the language is hardly unparalleled when it comes specifically to Ereshkigal - in Nergal and Ereshkigal, despite lack of a family connection to speak of between the eponymous protagonists, they are similarly metaphorically described as siblings in order to show they came to function as equals sharing control over the underworld (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 41). One is tempted to add that in the same myth Ereshkigal is addressed as the sister of “the gods” treated as a collective when she is invited by them to the banquet held in heaven (Untersuchungen zur Gestalt…, p. 418) - such a letter would obviously aim to present the parties as equals. Jordanova’s argument is arguably strengthened further by the fact there is a clear parallel for Inanna metaphorically referring to another deity as her sister while seeking to improve her own status at their expense or at least by being formally proclaimed equally influential in the same spheres of activity, too. Enki and the World Order includes a relatively long passage in which Inanna complains about the unique functions (garza) assigned to other goddesses, including Nintu, Ninisina, Nisaba, Ninmug and Nanshe (Enki and…, p. 6-7). She refers to three of them - Ninisina, Ninmug (Enki and…, p. 49) and Nisaba as her “sisters” (Enki and…, p. 51; Jerrold Cooper argues that in the case of Ninisina, this presumably reflects her paramount importance in the eyes of the kings of Isin; Enki and…, p. 2). This myth is chiefly known from copies from around 1800-1700 BCE (Enki and…, p. 2), much like Inanna’s Descent.

Ereshkigal would thus be just one of multiple deities who, in different narratives, are the (temporary) target of Inanna’s jealousy. Ereshkigal is her “sister” when she temporarily usurps her throne; Ninmug or Nisaba are her “sisters” when she wants Enki to assign the same position to her, too. None of them need to have any deeper connection to her otherwise. While this alone would be a satisfying conclusion, I would like to propose one more adjustment. I think Gadotti’s comment about Gugalanna is particularly illuminating, and warrants further consideration. If Inanna is lying about his death - or perhaps made him up on the spot - could it be that the entire quote is intended as her attempt to fool Ereshkigal’s doorkeeper? Could calling her “older sister” be dishonest humility, as opposed to admission of inferior position? Could it be that Inanna is effectively doing what Dādī-ḫadun did to Zimri-Lim? This is obviously pure speculation, and speculation of an obsessive hobbyist at that - don’t take it too seriously. I think it would be an interesting, period-appropriate approach to take in a retelling, though. If the foundation of the idea that Inanna and Ereshkigal is so shaky, why does it occupy such a prominent place in the reception of the myth this article revolves around - and, really, of these two figures in general? Personally I think it’s down just to its relatively early translation, and subsequent publication of its questionable interpretations in books aimed at general audiences. Ultimately most of the non-academic publications I’ve discussed in the first section go back to Campbell, not Kramer. People are thus exposed to an artificial image of Inanna and Ereshkigal as closely related polar opposites, life and death, light and dark, and so on, with the supposed sisterhood as the glue binding it all, but ultimately a secondary concern. And while it’s hard to object to the perception of Ereshkigal as the goddess of death - because that’s really who she was at the core - the Inanna compared to her by Campbell or Walker is really something manufactured on the spot. She is not really the favorite literary character of Old Babylonian audiences - a goddess with multiple spheres of activity including but not limited to love, war, the sky and investiture of rulers - but rather some sort of simplistic personification of “life” or “fertility” or some other similarly nebulous concept. At the absolute best, a reverse Ereshkigal. Truthfully, the problem isn’t just that Inanna and Ereshkigal aren’t really particularly closely related to each other, or whether they really are sisters. The issue with the popular perception of the myth is more that in reality they were not opposites of each other more than any two randomly selected deities with different primary functions. You could very well argue that Inanna, as a war deity, was a goddess of “inflicting death” much in the way Nergal was; meanwhile, Ereshkigal is hardly portrayed as incapable of exhibiting strong emotions like her, including lust. It’s quite literally the core of the plot of Nergal and Ereshkigal that she does feel it! Neither of them existed simply to be the polar opposite of the other, and neither of them can be defined just by her role in a single myth, let alone in a simplified summary of it. Given the torment Inanna’s Descent had to be put through by Cambell and his imitators in order to render Inanna and Ereshkigal polar opposites of each other, one is tempted to imagine a hypothetical scenario where Enki and the World Order gets translated first instead. Ninmug, as an artisan deity, is credited with the creation of assorted works of art (Enki and…, p. 49); Inanna, meanwhile, “destroyed that which should not be destroyed, (...) razed that which should not be razed” (Enki and…, p. 53) - would the supposed duality exemplified by supposed “sisterhood” be transferred to them? Perhaps in the alternate 2025 there would be a gacha game where Ninmug is an Inanna recolor?

Ultimately, deities with multiple appearances in literary texts simply cannot be boiled down to simple archetypes - whether they are literally siblings or not.

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adonis was called "destroyed by the Muses" because the Muses, angry at Aphrodite for causing them to fall in love and making many of them give birth, killed her beloved Adonis. They sang a delightful hunting song, and hearing it, he was excited and rushed to hunt, where he was killed by a boar. Others say he was killed by Ares in the war. The Muses, carried away by their anger at Aphrodite, because she had stirred many of them to love and persuaded them to mate with men and give birth, such as Calliope giving birth to Orpheus and Cymodoce from Oeagrus; Terpsichore giving birth to Rhesus from Strymon; Cleio giving birth to Linus from Magnes; they killed her beloved Adonis. For they sang a delightful hunting song and caused Adonis, Aphrodite's lover, who heard it, to be excited and rushed to hunt

-Tzetzes, Ad Lycophronem, 831

Yo another culprits whom Aphrodite or Adonis pissed off.

I won't be surprised if everyone else wanted her man dead.

#tagamemnon#greek myth#greek mythology#aphrodite#adonis#ares is jealous#artemis for killing hippolytus#persephone wanted her man#hera because...reasons (same account has her cursed aphrodite out of jealousy??)

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone in a discord server I’m in is going over the Lilith retelling book in the “read this so you don’t have to”.

And holy shit this is so much worse than I expected.

My expectations is zero to none, but did not expected this level of no awareness just by how misogynistic the book is despite championing feminism.

Some highlights:

Lilith turned into a serpent and has Eve eat the fruit to gain consciousness on the patriarchy. She does so and gain an attitude. Eve tries to get Adam to eat the fruit (cause it contained the mysteriesTM). Adam eats it and he doesn't inherited the p o w e r.

Lilith blaming Eve for not escaping the patriarchy

#i'm tired boss#biblical mythology#mythology#lilith#non-greek#and this is only part 1#still baffled it it has any shred of high ratings on GR

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Left: Aphrodite on a Tortoise, Athens, 420-400 BCE

Right: Aphrodite to the tortoise, 2nd century - 3rd century AD, Temple of Artemis

Behind the stoa built from the spoils taken from Kerkyra is a temple to Aphrodite; the precinct is in the open air not very far from the temple. In the temple is the image of the goddess whom they call ‘Ourania’; it is made of ivory and gold and it is the work of Phidias; it stands with one foot upon a tortoise.

-Pausanias, 6.25.1

Phidias represented the Aphrodite of the Eleans as stepping on a tortoise to typify for womankind staying at home and keeping silent.

-Plutarch

The very shell that makes up the tortoise’s ‘body’, her ‘clothing’, is also her ‘home’ where she sits in security and silence. The inter-relation between the Greek house and Greek dress has not received any serious study, notwithstanding the heavy symbolism that is attached to and shared by both. Like the shell of the tortoise that is simultaneously its clothing and its home, the veil also acts as a shell for a woman and becomes an extension of her living-space. Plutarch’s tortoise-motif certainly suggests that the Greeks were aware of this connection between the covering created by dress and the covering created by a house, and further investigation into the ways in which they observed and even named parts of the house and items of clothing will quickly reveal that the association was very much at the front of the Greek mind and, in fact, a component of the Greek subconscious.

-Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones' Aphrodite's Tortoise: The Veiled Woman of Ancient Greece

1 note

·

View note

Note

why’d you rewrite medusa like that

your attachment to the artificial construct that is the idea of "mythology" which is entirely detached from the context of the history of ancient greek and roman literature is hindering you from engaging with these texts meaningfully

666 notes

·

View notes

Text

Want to share this resources full of history maps made by a historian. It includes the Ancient Greeks, Romans, and the Homeric in various subjects which comes in handy if you need reference for locations and polis.

#tagamemnon#greek myth#greek mythology#history#ancient greece#ancient rome#byzantine history#ancient history#resources

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We need a Greek history/myth movie made by Greeks instead of Americans!"

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the city are graves of Megarians. They made one for those who died in the Persian invasion, and what is called the Aesymnium (Shrine of Aesymnus) was also a tomb of heroes. When Agamemnon's son Hyperion, the last king of Megara, was killed by Sandion for his greed and violence, they resolved no longer to be ruled by one king, but to have elected magistrates and to obey one another in turn. Then Aesymnus, who had a reputation second to none among the Megarians, came to the god in Delphi and asked in what way they could be prosperous. The oracle in its reply said that they would fare well if they took counsel with the majority. This utterance they took to refer to the dead, and built a council chamber in this place in order that the grave of their heroes might be within it.

-Pausanias, Description of Greece, 1.43.3

Yes, the same Agamemnon, and no, probably not the same Hyperion despite what TopoTexts tells you.

#tagamemnon#greek myth#greek mythology#pausanias#agamemnon#topotexts has 2 hyperion entries for some reason#this seems to be part of the megarian mythology...which we don't know much...#so uhh i have no explanation for this hyperion dude

1 note

·

View note

Text

"i'm gonna make Greek myth as historically accurate setting as possible and I'm gonna set it in Bronze Age"

Alright, what you got?

"Helen and Penelope were strong women cuz historically Sparta was a stronger city and has progressive rights for women."

That Sparta didn't existed in the Bronze Age, let alone in Archaic Greece.

"The Greeks will be dressed in Mycenean fashion"

So why is Heracles the only dude not seen as such? Also where are the long hair braids?

"I'm gonna have the Trojans wear entirely Greek attires"

Wasn't Troy settled by the Hittites during that one small period?

"Theseus is an asshole cuz he reflects the Athenians society and patriarchy"

Oh so you are going off Athens in the Classical era now?

#tagamemnon#greek myth#greek mythology#ancient greece#these are just some funny observations i have#whenever someone tries to dissect the myths through historicity#or headcannon set in bronze age but not knowing they sprinkle anachronisms here and there

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musaeus tells how Zeus at birth was handed over by Rhea to Themis, and by Themis to Amalthea, who gave him to the Goat, the daughter of the Sun, to rear in the caves of Crete. When he grew up and went to war with the Titans, he used the skin of the Goat as his shield because it was invulnerable and bore a Gorgon’s face in the middle. He set the Goat in the sky as a constellation, while he himself acquired the epithet Aigiochos, 'goat-skin holder'

-fragment from Eratosthenes of Cyrene's Katasterismoi

13 notes

·

View notes