Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

How Did Belief Evolve?

About 20 years ago, the residents of Padangtegal village in Bali, Indonesia, had a problem. The famous, monkey-filled forest surrounding the local Hindu temple complex had become stunted, and saplings failed to sprout and thrive. Since I was conducting fieldwork in the area, the head of the village council, Pak Acin, asked me and my team to investigate.

We discovered that locals and tourists visiting the temples had previously brought food wrapped in banana leaves, then tossed the used leaves on the ground. But when plastic-wrapped meals became popular, visitors threw the plastic onto the forest floor, where it choked the young trees.

I told Acin we would clean up the soil and suggested he enact a law prohibiting plastic around the temples. He laughed and told us a ban would be useless. The only thing that would change people’s behavior was belief. What we needed, he said, was a goddess of plastic.

Over the next year, our research team and Balinese collaborators didn’t exactly invent a Hindu deity. But we did harness Balinese beliefs and traditions about harmony between people and environments. We created new narratives about plastic, forests, monkeys, and temples. We developed ritualistic caretaking behaviors that forged new relationships between humans, monkeys, and forests.

As a result, the soils and undergrowth were rejuvenated, the trees grew stronger and taller, and the monkeys thrived. Most importantly, the local community reaped the economic and social benefits of a healthy, vigorous forest and temple complex.

Acin taught me that science and rules cannot ensure lasting change without belief—the most creative and destructive ability humans have ever evolved.

“A cremation ceremony is held in the Sacred Monkey Forest near the village of Padangtegal in Bali, where the author’s investigations into plastic littering emphasized the power of belief to change behavior. (Credit: Shankar S./Flickr)”

Most people assume “belief” refers to religion. But it is so much more. Belief is the ability to combine histories and experiences with imagination, to think beyond the here and now. It enables humans to see, feel, and know an idea that is not immediately present to the senses, then wholly invest in making that idea one’s reality.

We must believe in ideas and abilities in order to invent iPhones, construct rockets, and make movies. We must believe in the value of goods, currencies, and knowledge to build economies. We must believe in collective ideals, constitutions, and institutions to form nations. We must believe in love (something no one can clearly see, define, or understand) to engage in relationships.

In my recent book, Why We Believe, I explore how we evolved this universally and uniquely human capacity, drawing on my 26 years of research into human and other primates’ evolution, biology, and daily lives. Our 2-million-year journey to complex religions, political philosophies, and technologies essentially follows a three-step path: from imagination to meaning-making to belief systems. To trace that path, we must go back to where it started: rocks.

A llittle over 2 million years ago, our genus (Homo) emerged and pushed the evolutionary envelope. Its hominin ancestors had been doing pretty well as socially dynamic, cognitively complex, stone tool–wielding primates. But Homo ratcheted up reliance on one another to better evade predators, forage and process new foods, communally raise young, and fashion superior stone tools.

One of the skills that helped Homo succeed was imagination—an ability you can use now to picture how it developed.

Imagine an early Homo preparing the evening meal. She knows stones can be hit and flaked to form sharper utensils that cut and chop. She also knows the stone tools her ancestors made don’t do a particularly great job: They take a long time to hack the raw meat off a carcass, to smash and grind the roots the community has dug up, and to crack open bones and scoop out the delicious marrow.

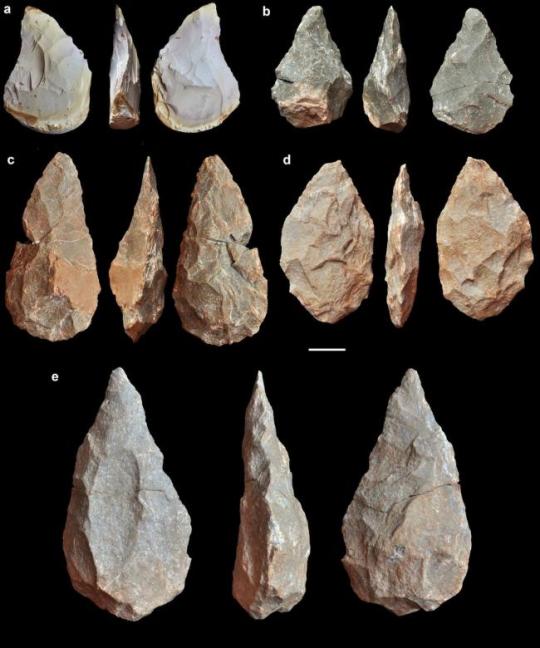

“Acheulean hand axes (shown here) were made by members of the genus Homo as far back as 1.76 million years ago. Named after the French site where they were first identified, these tools have been found across Africa, Europe, and Asia. (Credit: Rolf Quam/Binghamton University/EurekAlert) “

One day she looks at her brethren laboring to create simple, one-sided, flaked stone tools. She sees, in her mind’s eye, flakes being removed from both sides, further sharpening the edges and balancing the shape. She creates a mental representation of a possibility—and she makes it her reality.

She and her descendants experiment with more extensive reshaping of stones—creating, for example, Acheulean hand axes. They begin to predict flaking patterns. They conceive of more diverse instruments for slicing roots and raw meat, and carving bone and wood. They translate private musings and imaginings into communal realities. When they make a discovery, they teach one another, speeding up the invention process and expanding the possibilities of their efforts.

By 500,000 years ago, Homo had mastered the skill of shaping stone, bone, hides, horns, and wood into dozens of tool types. Some of these tools were so symmetrical and aesthetically pleasing that some scientists speculate toolmaking took on a ritual aspect that connected Homo artisans with their traditions and community. These ritualistic behaviors may have evolved, hundreds of thousands of years later, into the rituals we see in religions.

With their new gadgets, Homo chopped wood, dug deeper for tubers, collected new fruits and leaves, and put a wider variety of animals on the menu. These activities—expanding their diets, constructing new ecologies, and altering the implements in their environment—literally reshaped their bodies and minds.

In response to these diverse experiences, Homo grew increasingly dynamic neural pathways that allowed them to become even more responsive to their environment. During this time period, Homo’s brains reached their modern size.

But their brains didn’t uniformly enlarge. Parts of the frontal lobes—which play critical roles in emotional, social, motivational, and perceptual processes, as well as decision-making, attention, and working memory—expanded and elaborated at an increased rate.

Another brain organ that ballooned was the cerebellum. Over the course of hominin history, our lineage added approximately 16 billion more cerebellar neurons than would be expected for our brain size. This ancient brain organ is involved with social sensory-motor skills, imitation, and complex sequences of behavior.

These structural changes helped Homo generate more effective and expansive mental representations. What emerged was a distinctively human imagination—the capacity that allows us to create and shape our futures. It also gave rise to the next step in the evolution of belief: meaning-making.

The rise of imagination sparked positive feedback loops between creativity, social collaboration, teaching, learning, and experimenting. The advent of cooking opened up a new landscape of foods and nutrient profiles. By boiling, barbecuing, grinding, or mashing meat and plants, Homo maximized access to proteins, fats, and minerals.

This gave them the nutrition and energy necessary for extended childhood brain development and increased neural connectivity. It allowed them to travel greater distances. It enabled them to evolve neurobiologies and social capacities that made it possible to move from imagining and making new tools to imagining and making new ways of being human.

By about 200,000 years ago, Homo had begun to push the artistic envelope. Groups of Homo sapiens were coloring their stone tools with ochres—red, yellow, and brown pigments made of iron oxide. They were likely also using ochres to paint their bodies and cave walls.

Ochre decoration requires far more complicated cognitive processes than, for example, an Australasian bowerbird arranging sparkling glass and other baubles around its nest to attract a mate. It requires the kind of complex creative sequences made possible by elaborate frontal lobes, a dense cerebellum, and more diverse and intricate social relationships.

Imagine an early Homo sapiens who wants to paint a stone ax. She and her companions must seek out specific types of rocks and use a tool to scrape off the iron oxides. Then, they might manipulate the minerals’ chemistry, mixing them with water to transform them into pigments or heating them to turn them from yellow to red. Finally, they must apply the paint to the ax, changing how light reflects off its surface—making it look different, making it into a new thing.

When early humans colored something (or someone) red or yellow, it changed the way they perceived that tool, that cave, that person. They were using their imagination to reshape their world to match their desired perceptions of it. They were imbuing objects and bodies with a new, shared meaning.

Gradually, they established relations with more and more distant groups, sharing meanings for the items they swapped and the interactions they exchanged. In short, Homo sapiens began engaging full time in meaning-making.

Collective meaning-making changes the way humans perceive and experience the world. It enables us to do the wildly imaginative, creative, and destructive things we do. It is during this period that Homo broke the boundaries of the material and the visible so the realm of pure imagination could be made tangible.

When a typhoon smashes into land, it tosses trees like matchsticks and fills the air with a deafening roar that drowns out voices. For millennia, every animal caught in such a storm feared it, hunkered down, and waited for it to pass. But at some point, members of the genus Homo began to explain it.

We don’t know when it happened, but within the last few hundred thousand years, humans had developed the imagination, the thirst for meaning, and the communication skills necessary for creating explanations of mysterious phenomena.

By 300,000 to 400,000 years ago, human groups across the planet were sparking fires with sticks and stones, and carefully transporting the flames. And by 80,000 years ago, they were carrying water in intricately carved ostrich eggshells. They made glues to craft containers, adorned themselves with beads, painted with multi-ingredient pigments, and etched geometric patterns into shells, stones, and bones.

These kinds of hyper-complex, multi-sequence behaviors cannot simply be imitated. They require explanation. So, when researchers see multiple instances of abstract art and creative crafts, we assume individuals were engaging in deep, intricate communication based on shared meanings.

By at least 40,000 to 50,000 years ago, representational art arose: depictions of hunts, animal-human hybrids, blazing sunsets, and hand prints waving, as if they are signaling

Once groups are attributing shared meaning to objects they can manipulate, it is an easy jump to give shared meaning to larger elements they cannot change: storms, floods, earthquakes, volcanoes, eclipses, and even death. We have evidence that by at least a few hundred thousand years ago, early humans were placing their dead in caves. Within the past 50,000 years, distinct examples of burial practices became more and more common.

Through language, deeply held thoughts and imaginings could be transferred rapidly and effectively from individuals to small groups to wider populations. This created large-scale shared structures of meaning—what we call belief systems.

Between about 4,000 to 15,000 years ago, numerous radical transitions occurred in many populations. Humans started to domesticate plants and animals. They developed, along with agriculture, substantial food storage capacities and technologies. Concepts of property and inequality emerged. Towns and, eventually, cities grew. All of this led to the formation of multi-community settlements with stratified political and economic structures.

This restructuring profoundly shaped, and was shaped by, belief systems. Toward the end of this period—by 4,000 to 8,000 years ago—we see clear evidence of formal religious institutions: monuments, gathering places, sanctuaries, and altars.

There are numerous explanations for the evolution of religions, and none of them by itself is satisfactory. Some proposals are psychological: Our ancestors understood that other individuals have different mental states, motivation, and agency, so they attributed those same qualities to supernatural agents to explain everything from lightning to illness.

Other researchers note that the rise of huge, hierarchical communities that engaged in large-scale cooperation and warfare correlated with the rise of far-reaching, hierarchical religions with powerful, moralizing deities. Some scientists posit that “big groups” prompted the creation of “big gods” who could enforce order and cooperation in unruly societies. Other researchers hypothesize the reverse: that humans first created “big god” religions in order to coordinate larger and larger social groups.

Still other experts say the human capacity for imagination became so expansive it reached beyond the real and the possible into the unreal and the impossible. This generated the capacity for transcendence—a central feature in the religious experience.

But though belief can be transcendent, creative, and unifying, not all of humanity’s beliefs are beneficial.

For example, many humans today believe the world should be exploited for our benefit. Many believe that racial, gendered, and xenophobic inequalities are a “natural” result of inherent differences. Many believe in religious, scientific, or political fundamentalism, which is often used as a weapon against other belief systems.

Over the past 2 million years, we have evolved a capacity that has benefited humans but can also introduce horrible possibilities. It is up to us to manage how we use this power.

Now that we have asked, Why do we believe?, we should ask, What do we want to believe, for the sake of humanity?

https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/how-did-belief-evolve

0 notes

Text

Why people believe in conspiracy theories – and how to change their minds

I’m sitting on a train when a group of football fans streams on. Fresh from the game – their team has clearly won – they occupy the empty seats around me. One picks up a discarded newspaper and chuckles derisively as she reads about the latest “alternative facts” peddled by Donald Trump.

The others soon chip in with their thoughts on the US president’s fondness for conspiracy theories. The chatter quickly turns to other conspiracies and I enjoy eavesdropping while the group brutally mock flat Earthers, chemtrails memes and Gwyneth Paltrow’s latest idea.

Then there’s a lull in the conversation, and someone takes it as an opportunity to pipe in with: “That stuff might be nonsense, but don’t try and tell me you can trust everything the mainstream feeds us! Take the moon landings, they were obviously faked and not even very well. I read this blog the other day that pointed out there aren’t even stars in any of the pictures!”

To my amazement the group joins in with other “evidence” supporting the moon landing hoax: inconsistent shadows in photographs, a fluttering flag when there’s no atmosphere on the moon, how Neil Armstrong was filmed walking on to the surface when no-one was there to hold the camera.

A minute ago they seemed like rational people capable of assessing evidence and coming to a logical conclusion. But now things are taking a turn down crackpot alley. So I take a deep breath and decide to chip in.

“Actually all that can be explained quite easily … ”

They turn to me aghast that a stranger would dare to butt into their conversation. I continue undeterred, hitting them with a barrage of facts and rational explanations.

“The flag didn’t flutter in the wind, it just moved as Buzz Aldrin planted it! Photos were taken during lunar daytime – and obviously you can’t see the stars during the day. The weird shadows are because of the very wide-angle lenses they used which distort the photos. And nobody took the footage of Neil descending the ladder. There was a camera mounted on the outside of the lunar module which filmed him making his giant leap. If that isn’t enough then the final clinching proof comes from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter’s photos of the landing sites where you can clearly see the tracks that the astronauts made as they wandered around the surface.

“Nailed it!” I think to myself.

But it appears my listeners are far from convinced. They turn on me, producing more and more ridiculous claims. Stanley Kubrick filmed the lot, key personnel have died in mysterious ways, and so on …

The train pulls up in a station, it isn’t my stop but I take the opportunity to make an exit anyway. As I sheepishly mind the gap I wonder why my facts failed so badly to change their minds.

The simple answer is that facts and rational arguments really aren’t very good at altering people’s beliefs. That’s because our rational brains are fitted with not-so-evolved evolutionary hard wiring. One of the reasons why conspiracy theories spring up with such regularity is due to our desire to impose structure on the world and incredible ability to recognise patterns. Indeed, a recent study showed a correlation between an individual’s need for structure and tendency to believe in a conspiracy theory.

It seems our need for structure and our pattern recognition skill can be rather overactive, causing a tendency to spot patterns – like constellations, clouds that looks like dogs and vaccines causing autism – where in fact there are none.

The ability to see patterns was probably a useful survival trait for our ancestors – better to mistakenly spot signs of a predator than to overlook a real big hungry cat. But plonk the same tendency in our information rich world and we see nonexistent links between cause and effect – conspiracy theories – all over the place.

Peer pressure

Another reason we are so keen to believe in conspiracy theories is that we are social animals and our status in that society is much more important (from an evolutionary standpoint) than being right. Consequently we constantly compare our actions and beliefs to those of our peers, and then alter them to fit in. This means that if our social group believes something, we are more likely to follow the herd.

This effect of social influence on behaviour was nicely demonstrated back in 1961 by the street corner experiment, conducted by the US social psychologist Stanley Milgram (better known for his work on obedience to authority figures) and colleagues. The experiment was simple (and fun) enough for you to replicate. Just pick a busy street corner and stare at the sky for 60 seconds.

Most likely very few folks will stop and check what you are looking at – in this situation Milgram found that about 4% of the passersby joined in. Now get some friends to join you with your lofty observations. As the group grows, more and more strangers will stop and stare aloft. By the time the group has grown to 15 sky gazers, about 40% of the by-passers will have stopped and craned their necks along with you. You have almost certainly seen the same effect in action at markets where you find yourself drawn to the stand with the crowd around it.

The principle applies just as powerfully to ideas. If more people believe a piece of information, then we are more likely to accept it as true. And so if, via our social group, we are overly exposed to a particular idea then it becomes embedded in our world view. In short social proof is a much more effective persuasion technique than purely evidence-based proof, which is of course why this sort of proof is so popular in advertising (“80% of mums agree”).

Social proof is just one of a host of logical fallacies that also cause us to overlook evidence. A related issue is the ever-present confirmation bias, that tendency for folks to seek out and believe the data that supports their views while discounting the stuff that doesn’t. We all suffer from this. Just think back to the last time you heard a debate on the radio or television. How convincing did you find the argument that ran counter to your view compared to the one that agreed with it?

The chances are that, whatever the rationality of either side, you largely dismissed the opposition arguments while applauding those who agreed with you. Confirmation bias also manifests as a tendency to select information from sources that already agree with our views (which probably comes from the social group that we relate too). Hence your political beliefs probably dictate your preferred news outlets.

Of course there is a belief system that recognises logical fallacies such as confirmation bias and tries to iron them out. Science, through repetition of observations, turns anecdote into data, reduces confirmation bias and accepts that theories can be updated in the face of evidence. That means that it is open to correcting its core texts. Nevertheless, confirmation bias plagues us all. Star physicist Richard Feynman famously described an example of it that cropped up in one of the most rigorous areas of sciences, particle physics.

“Millikan measured the charge on an electron by an experiment with falling oil drops and got an answer which we now know not to be quite right. It’s a little bit off, because he had the incorrect value for the viscosity of air. It’s interesting to look at the history of measurements of the charge of the electron, after Millikan. If you plot them as a function of time, you find that one is a little bigger than Millikan’s, and the next one’s a little bit bigger than that, and the next one’s a little bit bigger than that, until finally they settle down to a number which is higher.”

“Why didn’t they discover that the new number was higher right away? It’s a thing that scientists are ashamed of – this history – because it’s apparent that people did things like this: When they got a number that was too high above Millikan’s, they thought something must be wrong and they would look for and find a reason why something might be wrong. When they got a number closer to Millikan’s value they didn’t look so hard.”

Myth-busting mishaps

You might be tempted to take a lead from popular media by tackling misconceptions and conspiracy theories via the myth-busting approach. Naming the myth alongside the reality seems like a good way to compare the fact and falsehoods side by side so that the truth will emerge. But once again this turns out to be a bad approach, it appears to elicit something that has come to be known as the backfire effect, whereby the myth ends up becoming more memorable than the fact.

One of the most striking examples of this was seen in a study evaluating a “Myths and Facts” flyer about flu vaccines. Immediately after reading the flyer, participants accurately remembered the facts as facts and the myths as myths. But just 30 minutes later this had been completely turned on its head, with the myths being much more likely to be remembered as “facts”.

The thinking is that merely mentioning the myths actually helps to reinforce them. And then as time passes you forget the context in which you heard the myth – in this case during a debunking – and are left with just the memory of the myth itself.

To make matters worse, presenting corrective information to a group with firmly held beliefs can actually strengthen their view, despite the new information undermining it. New evidence creates inconsistencies in our beliefs and an associated emotional discomfort. But instead of modifying our belief we tend to invoke self-justification and even stronger dislike of opposing theories, which can make us more entrenched in our views. This has become known as the as the “boomerang effect” – and it is a huge problem when trying to nudge people towards better behaviours.

For example, studies have shown that public information messages aimed at reducing smoking, alcohol and drug consumption all had the reverse effect.

Make friends

So if you can’t rely on the facts how do you get people to bin their conspiracy theories or other irrational ideas?

Scientific literacy will probably help in the long run. By this I don’t mean a familiarity with scientific facts, figures and techniques. Instead what is needed is literacy in the scientific method, such as analytical thinking. And indeed studies show that dismissing conspiracy theories is associated with more analytic thinking. Most people will never do science, but we do come across it and use it on a daily basis and so citizens need the skills to critically assess scientific claims.

Of course, altering a nation’s curriculum isn’t going to help with my argument on the train. For a more immediate approach, it’s important to realise that being part of a tribe helps enormously. Before starting to preach the message, find some common ground.

Meanwhile, to avoid the backfire effect, ignore the myths. Don’t even mention or acknowledge them. Just make the key points: vaccines are safe and reduce the chances of getting flu by between 50% and 60%, full stop. Don’t mention the misconceptions, as they tend to be better remembered.

Also, don’t get the opponents gander up by challenging their worldview. Instead offer explanations that chime with their preexisting beliefs. For example, conservative climate-change deniers are much more likely to shift their views if they are also presented with the pro-environment business opportunities.

One more suggestion. Use stories to make your point. People engage with narratives much more strongly than with argumentative or descriptive dialogues. Stories link cause and effect making the conclusions that you want to present seem almost inevitable.

All of this is not to say that the facts and a scientific consensus aren’t important. They are critically so. But an an awareness of the flaws in our thinking allows you to present your point in a far more convincing fashion.

It is vital that we challenge dogma, but instead of linking unconnected dots and coming up with a conspiracy theory we need to demand the evidence from decision makers. Ask for the data that might support a belief and hunt for the information that tests it. Part of that process means recognising our own biased instincts, limitations and logical fallacies.

So how might my conversation on the train have gone if I’d heeded my own advice… Let’s go back to that moment when I observed that things were taking a turn down crackpot alley. This time, I take a deep breath and chip in with.

“Hey, great result at the game. Pity I couldn’t get a ticket.”

Soon we’re deep in conversation as we discuss the team’s chances this season. After a few minutes’ chatter I turn to the lunar landing conspiracy theorist “Hey, I was just thinking about that thing you said about the moon landings. Wasn’t the sun visible in some of the photos?”

He nods.

“Which means it was daytime on the moon, so just like here on Earth would you expect to see any stars?”

“Huh, I guess so, hadn’t thought of that. Maybe that blog didn’t have it all right.”

https://theconversation.com/why-people-believe-in-conspiracy-theories-and-how-to-change-their-minds-82514

1 note

·

View note

Text

Post-Election and COVID Pandemic Anxiety: 7 Ways to Care for Your Mental Health

Post-election anxiety can be particularly difficult for people when the candidate they supported doesn’t win. In fact, they may face even more strain on their mental health if they live in a state that supported their candidate.

Additionally, the more the candidate loses by, the greater the number of days of stress and depression for residents in those states.

According to a study led by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and Duke University, researchers analyzed data from nearly 500,000 adults, looking at mental health indicators during the 2016 general election.

They found that people who lived in states with a Hillary Clinton majority experienced on average an additional half-day of poor mental health in the month following election (December) compared with the month before (October).

Brandon Yan, UCSF medical student and health policy researcher, says the findings indicate that elections could impact public mental health, and election-related stress should be monitored.

“Our findings from the 2016 election suggest that voters of the candidate who loses, especially if this candidate lost unexpectedly, are most at risk for worsening of mental health. The climate in 2020 is also further polarized than in 2016, which could contribute to people’s response to an election outcome,” Yan told Healthline.

In fact, a survey conducted by The Harris Poll on behalf of the American Psychological Association (APA) reported that 68 percent of adults in the United States said that the 2020 election is a significant source of stress in their lives. Only 52 percent said the same about the 2016 election.

The COVID-19 pandemic further intensifies our anxiety and emotions

President Donald Trump’s and President-elect Joe Biden’s attitudes toward the pandemic may be adding to the stress and polarization voters feel.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has increased social isolation and further polarized our country politically, which likely affects how people respond to the outcome of the 2020 election,” explained Yan.

“One of the most stark differences between the two presidential candidates was their differing approaches to the pandemic, so for that reason alone, one would expect the pandemic to play a part in people’s reaction to the election.”

Dr. Leela R. Magavi, psychiatrist and regional medical director for Community Psychiatry, evaluates and treats individuals of all ages. She says she sees this firsthand in her patients.

“Some children and adults have lost their grandparents and loved ones due to COVID-19. Additionally, many adolescents are struggling with the loss of symbolic milestones and feel deeply saddened by the inability to walk for their graduation or attend prom,” Magavi told Healthline.

She believes that her patients have been directly impacted by the political climate and that many Americans will fare poorly with regard to emotional and physical health due to the 2020 election results.

“This week alone, I have evaluated children and adults who have expressed that they have been experiencing insomnia, irritability, appetite changes, and panic attacks due to anticipatory anxiety about the outcomes. I can only imagine what will occur if their preferred candidate is not elected,” Magavi said.

Her patients have expressed anxiety about the future of the country and believe the election process has caused their heart rate to increase and stress levels to elevate. Some of her adult patients have experienced anger, anxiety, and sadness due to the election and are binge eating and unable to fall asleep.

Inger Burnett-Zeigler, PhD, clinical psychologist and associate professor at Northwestern University, says healthcare, the economy, employment, immigration, and police violence are significant sources of stress that have the potential to negatively impact mental health this election cycle.

“These issues disproportionately impact racial/ethnic minorities, and people with lower income, who are already more vulnerable to stress, anxiety, depression and trauma. For some, if the election does not go their way, it can lead to feelings of hopelessness about the future,” Burnett-Zeigler told Healthline.

In addition to particular issues, feeling disappointment from a candidate losing may play a part in mental health, especially if people expected the candidate they support to win.

“Our study suggests that unexpected losses may drive mental health worsening because there is an incongruence between expectation and reality. In addition, studies from behavioral economics suggest that losses are felt more heavily than victories,” said Yan.

To deal with disappointment and stress related to your candidate losing the election, consider the following seven tips.

1. Stay connected

Communicating with those closest to you can help with navigating stress. If you feel like you can’t connect with friends and family about the election results, reach out to your doctor.

“Remember that your healthcare providers can be a valuable resource for support and referral to specialists who could help with election-related stress,” said Yan.

If you know someone struggling, reach out to them.

“Elections matter for health. Let’s recognize that and respond as a nation in a way that supports each other’s well-being and brings our communities closer,” Yan said.

2. Write down your thoughts

Putting your thoughts and emotions on paper can help express what you’re feeling when you’re struggling to do so verbally.

“Journaling about the situation and brainstorming solutions by drawing, using diagrams, or speaking to mentors and family members allows individuals to remain goal-directed when emotional,” said Magavi.

ADVERTISEMENTTry a top-rated app for meditation and sleep

Experience 100+ guided meditations with Calm’s award-winning meditation app. Designed for all experience levels, and available when you need it most in your day. Start your free trial today.

3. Pay attention to your body and mind

If you’re experiencing physical symptoms often associated with stress, such as headaches, stomachaches, fatigue, or sleeplessness, Magavi says you can break down your emotions into what’s experienced mentally versus physically.

“[This] helps children and adults identify when they are mad or sad when their emotions manifest as somatic symptoms, such as abdominal pain,” she said.

4. Embrace what’s in your control

While who becomes the president is out of your control, Magavi says creating a list of things in your control and techniques to live your life in a manner that aligns with your values and beliefs can help.

“Revisiting this list and partaking in mindfulness activities when rumination knocks at the door may alleviate individuals’ anxiety during this unpredictable and tumultuous year,” she said.

5. Limit news

News stations and social media will cover the winning candidate in abundance following the election.

“Resist the urge to obsessively watch the news or check social media. Designate specific times to check,” said Burnett-Zeigler.

She suggests balancing checking the news with other activities that help you to cope with stress, such as listening to podcasts, watching movies, reading, and exercising.

6. Parent with empathy

For parents of children aware of the 2020 election, knowing how to talk to them about the tension in the country can help reduce stress. Magavi suggests having open conversations with your children.

“[Explain] that open conversation is healthy, and this does not have to result in anyone changing their belief system or political affiliation. The most important thing is that conversations prioritize empathy and compassion,” said Magavi.

She recommends asking your kids open-ended questions and encouraging them to do the same with you.

“I have evaluated some families where the mother and father have opposing political beliefs, or parents and children have completely disparate political affiliation. It is of utmost importance to explain to children that they have the right to have their own beliefs and find their own voice as long as they are respecting others,” Magavi said.

7. Move on

If your candidate of choice loses, let yourself be disappointed for a brief amount of time and then move on.

“Try not to catastrophize or ruminate on bad outcomes,” said Burnett-Zeigler.

One way to do this is to remember that government has checks and balances and that presidents are only in office for a limited amount of time.

https://www.healthline.com/health-news/post-election-anxiety-7-ways-to-care-for-your-mental-health

0 notes

Text

Ancient Brains and Modern Anxiety

There’s no evolutionary reward for being relaxed in the face of danger. On the contrary, being suspicious of the merest hint of danger, and reacting vigorously to every possible threat, could be life-saving.

...The sound of a twig cracking?...could be a stealth lion attack!

...The hint of a moving shadow in our peripheral vision?...could be a rattlesnake!

...An unusual footprint?...could be an unknown predator!

Although most of us today inhabit a world where there are few immediate threats to life, our modern brains retain this primitive ‘threat detection’ system which is constantly scanning the world for danger and problems that require our attention.

We all necessarily see the world through the filter of our own biases, expectations and focus because we can’t attend to everything.

However, stress of any kind pushes us into high alert which fuels our underlying tendency to both see the worst, and to over-react when our fears seem to be realized. If we are currently worried or sad—or if we’ve developed lifelong "negative thinking" habits such as those associated with anxiety and depression—we are almost certainly regularly seeing ourselves, others and/or the world as more threatening, negative or lacking than they really are.

This has the unfortunate consequence that when we are struggling, we are often the least objective about what we are capable of, and what other people and the world can offer us. It doesn’t need spelling out why this is bad for our mental health and life choices.

We don’t see the world as it is, but as we are. And the truth is we are prone to look on the dark side. Learning to manage our ancient survival tendency to see possible threats everywhere can reduce much of our modern angst, anxiety, and depression.

Imagined threats and real ones affect us in the same way

Our threat-detection system depends on an initial, super-quick assessment of danger by a simple, ancient, emotional bit of our brain. To have the best chance at keeping us safe, it responds automatically without wasting much time on a full analysis of the situation or on any ‘top-down’ rational thinking, to launch automatic defensive behaviors such as fight or flight.

Thus when a ‘threat’ decision is made, we are not in full possession of information about the current situation. We take in enough information just to register the possibility of danger, but not how likely it is or how serious it might be. Our threat-detection system is looking for any possible match at all in the current situation—no matter how tenuous. What we see as a possible threat is based on a record of past experiences, such as the time a tiger ate my neighbor.

In other words, whilst our response is governed in part by what we see out in the world that might harm us, it is mainly driven by our store of expectations and fears based on interpretations of past experiences that tell us what to look out, and what is a threat to us and our view of ourselves. Thus if this "threat" store is overactive or overfull, we will continually be under stress as the world will appear constantly threatening.

For good evolutionary reasons, our automatic responses are largely the same irrespective of whether there is a clear objective threat in the environment - an angry saber-toothed tiger - or just the hint of a shadow that might just possibly be a tiger.

But crucially, our stress system will also respond the same if we perceive a threat even if it is entirely down to our interpretation or expectation or beliefs. If we currently believe that tigers eat sandwiches in addition to humans, we may react with fear to a trail of breadcrumbs.

In the modern world, our life is rarely in danger, but we can all be threatened by challenges to our status, how we are viewed by others, whether we are good enough, harm to those we love, or whether care or attention from others might be withdrawn, for example.

For each of us, it is our personal past experiences, our specific interpretation of them, and our idiosyncratic beliefs and expectations that determine what specific situations we individually see as a threat (beyond the obvious pouncing tigers, of course).

For example, if we are preoccupied with the fear we are not good enough and that we might get fired, we may interpret an odd look from our boss as something to be worried about. In fact, our boss may merely have something in their eye, be thinking about something unconnected to us, or may even be impressed by something we’ve done. If we are anxious about a relationship, we may worry that if our partner is ten minutes late to meet us it means they don’t care, when in fact their bus was unavoidably delayed.

When stressed, our thinking tends to back up our fears

Our ’thinking’ brain does not kick in to work out what has happened and what to do about it until after a threat signal has already triggered a physiological response and possibly some immediate action (such as fight, flight or freeze, where appropriate).

Unfortunately, at this point, the "big picture" rational bits of the brain tend to be switched off, as they are not central to immediate life-preservation. However, as noted above, when stressed, our store of past experiences and beliefs about danger is easily available.

Thus when we are trying to understand our distress at the moment, we continually fall back on our most readily available habitual thoughts and fears as an explanation, even though they may not really fit the current facts. So we find ourselves thinking that here’s more evidence that "I’ll never be good enough," "I’m going to get fired," "She’s going to leave me," even though all that happened is the boss made a funny expression, or our partner was ten minutes late.

If we are not careful, our mind then races away ruminating about the problems it has ‘identified’, and trying to work out how to fix them, even though they may have very little to do with what is happening at the moment. "Am I going to be able to pay the mortgage once I’ve been fired?" "Should I leave her before she dumps me?" At some level, these fears are felt as facts (imagined threats and real ones affect us in the same way, remember?) which perpetuates the stress cycle.

This is, of course, the basis of anxiety: A fear of something that hasn’t yet, that might never happen, that I am scared I can’t handle. These easily-activated thought patterns in fact merely reflect our triggers and deep-seated fears, but feel so very real at the moment.

Note that this is the opposite way around from how we usually understand our thoughts. We are not (initially) stressed because of what we are consciously thinking, but because of an unconscious, automatic, biased assessment of a situation—with our thoughts filling in an explanation after the fact.

Of course, our anxious thoughts can then themselves lead to more stress as we beat ourselves up, which can then refuel the cycle.

It is very easy for us to see the worst and act accordingly, often sabotaging even the best of situations.

What can I do about it?

Awareness is the key to changing any mental habit. Typically, our unhelpful mental habits are so normal to us that we often don’t notice until we’ve been stuck in baseless, negative loops of thought for hours - if we notice at all.

One very useful trick is to start tuning in to the bodily sensations associated with stresses and anxiety that almost always precede unhelpful habitual thoughts. These physical signs are related to the activation of the sympathetic nervous system that prepares us for action once a threat has been detected.

Using physical signs as cues gives us a much better chance of intercepting habitual negative thoughts before they have time to run away with us, and it reduces the time spent immersed in negative and dark thoughts.

You may recognize some of the following common signs of stress and anxiety: increased heart rate, increased muscle tension, tingling or numbness, hyperventilation, feeling weak, faint or dizzy, wanting to use the toilet more often, feeling sick, chest pain or tightness, tension headaches, feeling sweaty or feeling chilled, dry mouth. If you don't, watch out for them as you go through your day—you may have other symptoms too.

NB: It worth reminding ourselves this is a list of the symptoms of anxiety. Having these experiences is not a sign that there is anything wrong with us or the world. They are in fact a sign that our bodies are functioning normally.

If we notice these physical signs early enough, we can do two key things:

Firstly, we can learn to intercept before such feelings spiral into destructive thoughts.

Surprisingly often, an awareness of being stressed in the moment is sufficient to stop our usual habitual thoughts, but sometimes we can benefit from learning techniques that either displace those thoughts (e.g. count backward in 7s), or turn our attention away from them (e.g. focusing on what we can see, smell or hear).

It can also be helpful to identify the main "story lines" of our ruminations (e.g. "I’m not good enough," "She’ll abandon me"), so we can say to ourselves "Ok, I’ve heard you — you can stop now!"

Secondly, and just as importantly, by stepping back we can begin to get a more objective view of why the current situation feels threatening to us, and what our triggers are. Whilst it’s possible I’ve annoyed my boss which was why he looked at me strangely, there are other explanations. Start asking yourself the following sorts of questions:

Can I come up with other alternative explanations for what is happening?

What is the probability that my fearful assumptions are true?

Can I identify the fears or beliefs that lead me to see this situation as a threat?

Self-awareness, understanding, and acceptance are the enemies of anxiety.

As ever, stress makes it harder to resist the pull of our habitual unhelpful thoughts, which themselves fuel further stress. Furthermore, chronic high levels of stress changes our "stress thermostat" so that we are tipped over into anxiety in more situations—at its worst, leading to a generalized anxiety disorder. We can also get into the habit of overreacting so that we react in a similar way to work stress or a traffic jam as we would to a charging tiger.

Managing stress and learning how to relax is thus also critical to managing our ancient anxious brains. You probably already know what works for you, and what practical steps you could take to make your life more manageable. Start them today!

We may also need to "re-calibrate" our stress responses so they don't fire so often, or react so strongly—try this article on cold water swimming for one drastic solutions.

youtube

0 notes

Text

Evolutionary Psychology

The human body evolved over eons, slowly calibrating to the African savanna on which 98 percent of humankind lived and died. So, too, did the human brain. Evolutionary psychology is the study of the ways in which the mind was shaped by pressures to survive and reproduce. Findings in this field often shed light on "ultimate" as opposed to "proximal" causes of behavior.

1 note

·

View note