o-behave

184 posts

The blog that brings you the latest updates from the world of behavioural science with new research, insights and applications in the field.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

O-Behave moves to Medium

Thanks for coming to visit! We’ve now moved O Behave to Medium. Please visit us at https://medium.com/o-behave for the latest and greatest articles from Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science team.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zoom Fridays: The Future of Work?

Written by: Chloë Hutchings-Hay and Kimberly Richter

Recognising the potential gains in wellbeing and productivity, our team at the Behavioural Science Practice has experimented with setting aside one day a week where we move mountains from the Wi-Fi location of our choice. Connected only by video chat, we call it: Zoom Fridays!

The practical implications of this way of working are substantial; the average commute in London costs £2.40. What this amount doesn’t begin to cover are the intangibles that can’t be tapped onto an Oyster card – time (54 minutes, on average), the pollution, and not to mention the stress of being sandwiched between a family of five on the Central Line.

More and more companies are adopting work from home policies to keep their teams happy and to effectively manage office space. A recent study run by a team at Stanford partnered with a call centre in Shanghai to explore the related psychological impacts. Shifting the company culture to teleworking led to a massive improvement of performance, with a 13% increase in productivity and £2,000 additional profit generated by each employee. That’s nearly the equivalent of an additional day’s work, every week. Importantly, quit rates also dropped by 50%. With 84% of workers believing that allowing staff to work remotely shows that their company really trusts and values their contributions, technology clearly has a role to play in improving working environments.

What are the psychological benefits of video conferencing specifically, over traditional forms of office communication like email and phone calls? We’ve been working with Owl Labs on their 2019 State of Video Conferencing Report to find out. Here are three key findings that help us to better understand how video conferencing is changing the world of work:

Video conferencing improves the loneliness of remote workers

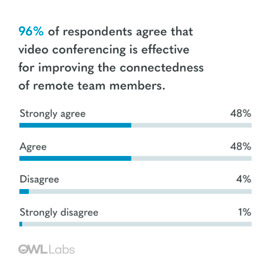

The 2019 State of Video Conferencing Report points to the emotional benefits of video to remote workers, with 96% of respondents agreeing that video conferencing helps improve the connectedness of remote team members. Indeed, respondents are almost 4 times as likely to prefer video conferencing to phone calls in helping their team work remotely. Given that we know that loneliness is amongst the biggest struggles with working remotely , this is an encouraging finding.

A video-call facilitates clearer communication than a phone call

Another key takeaway from the report is that when in-person communication isn’t possible, video conferencing is the best option for clear communication. This makes sense: we know that communication doesn’t just hinge on the words we say, but also on how we say them and how we convey information through our facial expressions and body language. Video conferencing allows for more of this information to be conveyed than either email or phone call.

In-person communication remains the top preference

The benefits of in-person communication still come through strongly from the report; in an increasingly digitised world, it is heartening to know that the benefits of face-to-face contact are still substantial. Together, these findings highlight the exciting opportunities ahead to blend remote work along with in-person meetings to create an optimal working environment.

We look forward to continued experimentation to experience for ourselves the psychological benefits and drawbacks of new technologies, video conferencing in particular. As the benefits of working from home become ever clearer, digital tools are needed to do it well.

Sources Cited:

(Bloom, Liang, Roberts, & Ying, 2015) https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/why-working-home-future-looking-technology

(Owl Labs State of Video Conferencing Report, 2019) https://www.owllabs.com/state-of-video-conferencing/2019?utm_campaign=State%20of%20Video%20Conferencing%202019&utm_source=Referral&utm_term=Ogilvy

(State of Remote Work 2019, 2019) https://buffer.com/state-of-remote-work-2019

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHAT ENVIRONMENTALISTS CAN LEARN FROM TEXANS

By Zac Baynham-Herd, Analyst at Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science Practice

As the dust settles on the recent environmental protests, activists would do well to consider three key behaviour change principles: messengers, commitment and conformity.

In the mid-80s the Texas Department of Transportation had a problem. Litter. Rising by 17 percent a year, and costing the state $20 million annually, beer cans, burger bags and cigarette butts were filling up the freeways.

In response, the Department tried something new. They turned to an advertising firm. Together they started an anti-litter campaign built around bumper stickers and the slogan ‘Don’t Mess with Texas’. The campaign was hugely successful, reducing highway litter by 72 percent and the slogan still persists in popular culture today.[1]

The campaign was so effective at changing behaviour, not because it turned litter throwing truckers into tree-hugging activists. Quite the opposite. Rather than explicitly challenging people’s behaviour, identity and values, it harnessed them. It drew upon Texan’s strong sense of state pride and individuality and thus ensured that actively not-littering, and advocating for the campaign bolstered individuals pre-existing social identities.

Indeed there is a wealth of literature demonstrating that environmental messages appeal differently to those from different social and political groups depending upon how they are framed. For instance, US conservatives are much more likely to respond positively to environmental messaging if it is framed around obeying authority, defending the purity of nature, and demonstrating patriotism.[2] Liberals by contrast, tend to be motivated much more by calls for justice, accountability and equality.

Perhaps unsurprisingly therefore, have there been contrasting reactions to the recent climate change protests led by Extinction Rebellion activists in London and across the world.[3] Predictably, those already championing social justice issues, state-level interventions and opposition to big-business are keen on the protesters, whereas those championing individual freedoms, economic growth and small government are less so.

Even environmentalists themselves are split on the appropriateness of the radical approach – acts of civil disruption and disobedience aiming to gain media attention and force the government to respond with policy changes.

Supporters see the doomsday like messages of approaching societal collapse as either brutally honest or simply necessary to scare people into action. Critics, either fear such messages may just generate hopeless inertia, or that they are exaggerated and unhelpful.

As Sadiq Khan’s ‘business as usual’ returns to London, regardless of where the truth lays, any environmental movement which aims to influence human behaviour – either in the home, public or at the ballot box – would benefit from taking heed of a three key behavioural science principles.

The Messenger Effect

Firstly we listen to and follow those who we most identify with. This messenger effect has been utilised by marketers for decades and even acts at the most basic of levels. For instance, if the gender of a person in a charitable appeal matches that of the donor, the amount of donations increases. Different celebrities behind conservation campaigns change responses to them and in polarized conflicts, swapping the side a suggested policy intervention is attributed to completely reverses respondent’s support for it. [4]

Currently, the Extinction Rebellion and climate protests remain populated largely by those they inspired first – the young, green and middle class. If widening engagement with the movement was an aim, it may require innovative ways to help people identify with it. This may include introducing particular support groups such as ‘parents’ or ‘workers for climate’ and choosing individuals from a widest possible range of backgrounds to represent the group in the media.

Commitment

Secondly, if people pledge or publicly say that they will do something, they are much more likely to follow through with it. Likewise, when a commitment incurs a cost and people have ‘skin in the game’ (such as getting arrested) others take notice. Of course this works fantastically well with charity runs, but this commitment effect has also been utilised for environmental protection.

In response to increasing environmental degradation at the hands of tourists, in 2017 the government of the Pacific island state of Palua introduced an environmental pledge to the visa of every visitor, which they had to personally sign upon entry and which they hope will increase stewardship.

On the flip-side, our desire to be consistent can actually prevent us from taking pro-environmental action. Many environmental activists hope to convert other people to be like them. However, the existence of a ‘green’ identity can, for some, be a barrier to wider behaviour change. Indeed, when we think about taking one green step – say changing our diet – we may start to feel hypocritical (or worry others might think we are) if we don’t also then go eventually ‘all-in’ and transform our lives.

Even the climate protesters have been heavily attacked for previously having holidays or using plastic. One way to circumvent the identity barrier, would be to focus on small pro-environmental steps which individuals from specific backgrounds can take without needing to change their identity. Like business executives swapping one flight a year for a conference call.

Conformity

Conformity is another key behavioural lever to be aware of and utilise. Social experiment after experiment has shown us how, not only is our behaviour predicted by what others around us do, but often we ignore our own beliefs in order follow the herd.[5] The more we see others around us doing something, from smoking to donating, the more we do it too.

The ability to see what others do (signalling) is crucial in producing conformity. Interestingly, the French gilets jaunes movement went viral without any clear leader or ‘messenger’. Instead, the hi-vis vest emerged as the social signal representing the cause. Crucially, due to a French law requiring every driver to stash a vest in their car, once the movement gained some traction, almost every French citizen had the immediate opportunity to conform and signal their support – and millions did.

As social animals, we like to be liked. Whilst most of the climate or gilets jaunes protestors really were hoping that the government took notice of them, if even unconsciously, they would likely also be hoping that so did their friends and colleagues. Indeed, many actions and positions we take are influenced by deep desire to either conform to our social identity or perceived ‘in-group’.[6]

Similarly, most climate change deniers are probably not deniers because they have critically appraised the science and reached that conclusion themselves. Instead, within communities where for whatever reason denialism is the norm, the social cost of not being a denier is very high. Indeed, the personal costs of being ostracised and losing all your friends is much higher than the personal climate benefit from reducing ones emissions (which on a global scale is almost negligible).

Indeed, we often take behavioural cues from our tribes. US Republicans tend to oppose taxes far more than Democrats do – consequently, it is likely hard to maintain an identity as a Republican whilst supporting a new tax. But, savvy campaigners can work with this constraint. Airline passengers who identify as Republican are much more willing to pay a green levy when it is called a ‘carbon offset’ than when it is framed as a ‘carbon tax.’[7]

So, do not despair, there are ways for environmentalists to reach out to new audiences and identities. But it might just require thinking like Texan.

References:

[1] https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/trashy-beginnings-dont-mess-texas-180962490/

[2] Wolsko, C., Ariceaga, H. and Seiden, J., 2016. Red, white, and blue enough to be green: Effects of moral framing on climate change attitudes and conservation behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/19/extinction-rebellion-climate-change-protests-london?CMP=twt_a-environment_b-gdneco

[4] Duthie, E., Veríssimo, D., Keane, A. and Knight, A.T., 2017. The effectiveness of celebrities in conservation marketing. PloS one.

[5] Thaler, R.H. and Sunstein, C.R., 2009. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin. Chapter 3.

[6] Strandberg, T., Sivén, D., Hall, L., Johansson, P. and Pärnamets, P., 2018. False beliefs and confabulation can lead to lasting changes in political attitudes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

[7] https://behavioralscientist.org/fight-climate-change-with-behavior-change/

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHY WE SHOULD BE A LITTLE LESS WORRIED ABOUT PANIC AND A LITTLE MORE ABOUT INACTION

By Chloe Hutchings-Hay, Analyst at Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science Practice

When people think of disasters, the common image is one of social breakdown, panic and irrational behaviour. It has also been suggested that people become hostile and take aggressive action towards others when faced with a disaster. This is in line with the ideas of Le Bon who suggested that submergence in the crowd leads to the loss of the conscious personality, with instincts for personal survival overriding socialized responses. In his view, due to mass contagion these reactions can spread quickly through a social group and create mass panic.

What is panic?

People who have been involved with disasters or watched them unfold often describe panic breaking out. However, the term panic refers to: irrational, groundless or hysterical flight that is carried out with complete disregard for others. Therefore, most often people are mistaking ‘fear’, which is perfectly rational, with ‘panic’, which would imply their behaviour was completely out of line with the risk posed. It is appropriate to experience fear in a crisis, and fleeing from a disaster is often the most rational course of action: this is not indicative of panic.

In reality, incidences of panic are very rare. It has been suggested that panic only occurs in very specific circumstances. Research has suggested that for a true instance of panic, the following conditions must be present at once: 1) the victim perceives that they are trapped in a confined space, 2) escape routes seem to be quickly closing, 3) flight seems to be the only way to survive and 4) no-one is available to help (Auf der Heide, 2004).

What do people actually do in disasters?

Many real-world cases suggest that, rather than acting selfishly, people tend to pull together both during and after disasters, displaying remarkable collective resilience. For example, analysis of behaviour during the London 7/7 bombings showed that there were only three accounts of people acting selfishly. Many more people described seeing altruistic behaviours. Although people were using the language of panic to describe what went on, their actual behaviour did not match the definition of panic (Drury et al., 2009).

Similarly, analysis from survivors of 9/11 found that almost everyone reported that the evacuation process to be calm and orderly, with evacuees making room for emergency responders to pass them by (Connell, 2001).

Another common belief is that disasters are usually accompanied by increases in antisocial activity, such as looting, traffic violations, and violence. Even when looting is not actually observed, this is often attributed to extraordinary security measures and the fact that such behaviour is inherently uncommon is overlooked. In actual fact, the amount of donated goods far exceeds that which could be looted in disasters (Heide, 2004). The remarkable collective resilience shown by communities in the wake of a disaster often goes unnoticed by media outlets (Drury et al. 2009).

Why is the notion of widespread panic a problem?

The widespread belief that the inevitable response to disasters is panic is massively problematic for several reasons, including:

1. Officials may hesitate to issue accurate warnings because they are afraid of causing panic, meaning that people are only informed of imminent risk at the last possible moment. This is problematic not only because it actually endangers people more, but also because people may begin to trust those relaying disaster messages less.

2. It prevents effective disaster preparation. People may become afraid that even the suggestion of preparing for a disaster would lead to panic ensuing, when actually disaster preparedness is absolutely vital. A particularly striking example comes from the difference in evacuation speed of the World Trade Centre from the 1993 bombings to the 2001 attacks. In 1993, the average exit time was 15 minutes (from Tower 1) and 35 minutes (from Tower 2). If the same evacuation speeds had been replicated in 2001, many more people would have died. A key difference between the two attacks was that after 1993 regular fire drills were carried out in the World Trade Centre and people were therefore more prepared.

3. The fear of widespread looting may prevent evacuation, despite this actually being an uncommon reaction.

4. The notion of panic can be used to deflect blame away from responsible parties. For example, the Hillsborough disaster was initially blamed upon a mass panic reaction. It later came to light that there was gross negligence on the part of the crowd controllers and the stadium design had contributed to the disaster, rather than it being the fault of those in the crowd themselves.

5. The focus upon panic masks a potentially larger risk, the risk of mass apathy. There are often significant delays in evacuating groups in impending emergencies, and some people choose not to evacuate at all. One of the key problems is that people tend to feel overly relaxed in the face of emergencies, in striking contrast to the idea that they will be massively panicked! If people do not feel that their life is in jeopardy, they likely will not evacuate. Disaster communication needs to be serious enough to convince people of the need to evacuate. Disaster communication needs also to consider other barriers to evacuation, such as illiteracy, mobility issues and lack of economic resources.

How should we actually communicate before and during disasters?

There is often mistrust for public information, and people often cross-check information with others and online to validate it. Therefore risk communication needs to be both widespread and consistent so that people know the key information and they trust it. The information relayed should be easy to understand and the key points should be repeated.

The person relaying the message should be proportionate to the risk posed, for example the Minister of State for Health would be appropriate for a national health outbreak, but less so for a local one. They should also be honest and truthful if they do not know the scale of a threat. Most crises have an element of uncertainty; the person communicating should admit uncertainty and say what they are doing to overcome it.

As we know that panic in response to disasters is actually uncommon, risk communicators should be preparing the public for the worst possible outcome if necessary. People who are feeling afraid can find it calming to prepare because it lets them feel in control, however many people will not be afraid and may even have stopped listening altogether. Every time officials repeat practical advice, more people take it (Sandman, 2009).

Finally, we need to minimize the language of panic. Instead of focusing on the possibility of panic we need to think about the risk of people doing nothing to prepare. Government disaster planners are researching the best ways to prompt people out of inaction and the impact of different forms of crisis communication (see https://bit.ly/2F71xij). Behavioural science no doubt plays a critical role in understanding risk perception and in designing successful crisis communication.

References

Connell, R. (2001). Collective behavior in the September 11, 2001 evacuation of the World Trade Center (Preliminary Paper# 313). Newark, DE: University of Delaware Disaster Research Center.

Drury, J., Cocking, C., & Reicher, S. (2009). The Nature of Collective Resilience: Survivor Reactions to the 2005 London Bombings. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 27(1), 66-95.

Heide, E. A. (2004). Common misconceptions about disasters: Panic, the disaster syndrome, and looting. The first 72 hours: A community approach to disaster preparedness, 337.

Rubin GJ et al. Psychological and behavioural reactions to the 7 July London bombings. A cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of Londoners. BMJ, 2005; 331(7517): 60-11

Sandman, P. M. (2009). The Swine Flue Crisis: The Government Is Preparing for the Worst While Hoping for the Best – It Needs to Tell the Public to Do the Same Thing. Retrieved from: http://www.psandman.com/col/swineflu1.htm

Much of the information is based on a Disaster Response MSc module at the IoPPN, led by Dr James Rubin

0 notes

Text

NEGOTIATIONS: WHEN PSYCHOLOGY HAS THE UPPER HAND

By Jack Duddy, Isabel Power, and Laurie Twine - Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science Practice

Have you ever left a situation feeling like you didn’t get what you actually wanted? Or even left an argument feeling like you lost even though you know that you were right, but couldn’t quite articulate why?

These are similar scenarios for many in their professional life, personal life and even on the world political stage. We can, however learn from those who have built their life on constructing arguments, deals and negotiations. Those like Chris Voss, former FBI hostage negotiator and co-author of the book Never Split the Difference. He believes his most successful negotiation outcomes came about when he employed simple psychological insights.

Whilst (we hope that) most of you do not encounter life and death hostage negotiations on a daily basis, you will be surprised by how much negotiating you do every day. In the words of Chris himself “life is a negotiation” and the majority of interactions we have at work and at home are negotiations that boil down to the expression of a simple, animalistic urge: I want.

This can be manifested as: “I want a pay rise” “I want the kids to go to bed at 9pm” “I want you to like and share this blog post around social media…” (worth a try)

Try and picture what your daily negotiations might be.

We have pulled six psychological insights used by Chris and other leading thinkers in the field of persuasion, that you can use in everyday life.

Before we jump in, remember: “Negotiation is not an act of battle; it’s a process of discovery. The goal is to uncover as much information as possible”.

1. Labelling Assure them that what they are feeling is okay

What to do: Identify what someone may feel or is currently feeling and call it out. This is best done with small phrases such as: ‘It sounds like or it seems like’

This can be one of the most powerful techniques when it is used effectively because labelling allows us to identify with a counterpart and show that we understand the position they are in. This also tells them that the emotional reaction they are having to what you’re saying is normal or even expected, and therefore not a barrier. Even when this is done incorrectly there can still be some benefit. As long as you have listened to someone and listened to their reaction, an incorrect label gives the person the opportunity to explain how they feel in another way. Either way you are closer to understanding someone’s circumstance, which ultimately is what your counterpart desires.

A couple to try

“This may make you feel shocked, but… ” “It seems like you are upset by this…” “It sounds like you are getting frustrated…”

2. Illusion of control

Make them feel like they are “active” in the negotiation and not just a bystander

What to do: Ask “how am I supposed to do that”

Control is incredibly important. If individuals feel vulnerable they are likely to act defensively which can break off communications and there is no progress without communication. So, you may ask ‘How I am supposed to move forward the conversation while making my counterpart feel that they have control’. Chris believes you should be posing almost this exact question to them.

When someone is trying to negotiate something out of you, asking your counterpart ‘How am I supposed to do that?’, forces them to consider your position and offer options. This is exactly what you want them to do, to see your side of the negotiation, offer solutions and then you are in the position of saying “yes or no”.

So how can you move the conversation forward whilst making your counterpart feel as if they are still in control.

3. Similarity ‘Mirroring’ Make them think you are on their wavelength and find similarities between you.

What to do: Copy the other person’s tone, body movement and language.

This may shock you to hear… but humans are surprisingly fickle. Even though we may be selfishly trying to get the most out of a situation, we can be incredibly swayed by whether we like the person in front of us. There are tricks and techniques to achieve this “like” factor which can be grouped together under the term “Mirroring”.

Mirroring is when you match another person in their body language, vocal tone and even the words they say. This makes you appear similar to each other which triggers the heuristic we have that “similarity = likeability + trust”.

One tactic is to simply repeat the words that someone is saying back to them. If you are using the same words, verbs, adjectives and jargon then they believe you are on their wave-length and the disconnect of “are they understanding me?” disappears.

Another mirroring tactic is to copy body-language. Stand or sit similarly to the other person during a conversation. But be subtle and natural. If they sit back in their chair, wait a moment and casually sit back as well, if they are sat forward and engaged then match this position with theirs to also seem engaged. Again, this indicates that there is a connection between the two of you and that you are not “against” each other in this negotiation.

4. ‘That’s Right’

Understand and validate their position

What to do: Summarise their position as you understand it. Pause and wait for their response.

People find it incredibly important to feel understood. In fact, chemicals actually change in our brain when we feel like someone is listening to us and we are much more open to discussion. Getting your counterpart to say ‘that’s right’ is important because it is a subconscious signal that they actually believe you understand their perspective.

What’s even better about hearing ‘that’s right’ is that you have not only reassured them and validated their position, but it also acts as confirmation that you have understood them and therefore you are able to move the conversation forward.

So how can you hear these magical two words? Whilst phrases like ‘yes’ or ‘you’re right’ may seem like you have hit the jackpot, they can be used as a defence mechanism. These phrases are used when people are exhausted and want to shut down communications. In order to avoid these generic responses do not ask a closed question such as ‘is that right’ as this puts pressure on the individual to give a quick response. Instead, paraphrase their position and use the ‘power of the pause’ to trigger a ‘that’s right’.

5. Execute action

Break stalemates by asking ‘calibrated questions’

What to do: Ask questions that begin with ‘What’ or ‘How’ to move the conversation forward. For example, ‘Taking this position into account, how can we move the deal forward’

Sometimes in negotiations you can find yourselves in situations when both sides appear to understand each other’s point of view and there have even be echoes of the golden ‘that’s right’, yet the discussion has reached an impasse.

Calibrated questions can move the discussion forward into action. By using this type of question, you not only repeat and therefore validate each other’s position it also helps the issues become three-dimensional. Which can help you and your counterpart think of better answers.

In order to be as effective as possible use ‘What’ and ‘How’s’ rather than ‘Why’s as these are non-threatening terms.

6. ‘NO’

Use ‘no’ to open up new paths of negotiation

What to do: Flip normal questions on their head to become no-orientated questions. Instead of ‘do you agree with this?’ try ‘is there anything you disagree with?

If you have been trying to implement all the above and you are still finding your counterpart comes back with ‘no’ then all is not lost. This actually offers you more opportunities than hearing a ‘yes’ because it paves the way for further discussion.

‘No’ is a protective word, whereas saying ‘yes’ means committing yourself to something you may not want to do in the future. Therefore, people have a natural inclination to say no.

We can capitalise on this by flipping some of our questions into ‘No-oriented questions’. Voss believes with this approach people are more likely to concede to your demands indirectly. He tells a story where he got access to a roped off VIP area in a restaurant, when, instead of explicitly asking for permission, he asked “Would it be horrible if we sat in this section?”

For those paying close attention you may have noticed this spells L-I-S-T-E-N. This is the principle that underpins almost all the literature and tactics on hostage negotiations. Listen to what the other person is saying, not just through their words but their entire body. This is your greatest tactic and only that way can you find out where they really stand, why they are saying what they are and to eliminate any sticking points.

Remember, at the end of the day, even though they may not seem it at the time, you are always talking to another person. In many ways they are just like you, and in just as many ways you are just like them. And just like them you are subject to the same biases and psychological techniques. It seems like you really enjoyed this blog. Is it ridiculous for us to suggest you read our other blogs too?

References

Voss, C., & Raz, T. (2016). Never split the difference: Negotiating as if your life depended on it. Random House.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

OPTIMISING PLACEBOS AND MINIMISING NOCEBOS

LESSONS FROM BEHAVIOURAL SCIENCE

By Chloe Hutchings-Hay, Analyst at Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science Practice

Placebo Effect

The placebo effect was first established when Henry Beecher, a World War II doctor, ran out of morphine, and decided to give his patients a salt-water injection instead. He was surprised to learn that many of his patients (around a third) responded as though they had actually received morphine.

Since then, the benefits of placebo have been observed in treatments for illnesses as disparate as depression and Parkinson’s disease. One study even found that sham shoulder surgeries were as effective at improving symptoms as the real surgery itself (Schroder et al., 2017).

Whilst initially these benefits were thought of as ‘fake’, and those who experienced placebo effects were deemed suggestible, growing evidence suggests that there are real neurobiological mechanisms underpinning placebo effects. Supporting this is the mounting evidence from open-label placebo studies, where improvement has still been observed even when patients know they are receiving a placebo (BMJ, 2018), suggesting that conditioning alone can bring about the placebo effect. What’s more, personality factors are shown to be less important in determining response to placebo than factors determined by the broader context, like expectancy effects and the quality of the doctor-patient relationship.

The understanding that the context is crucial in eliciting the placebo response lends itself to the use of behavioural nudges to optimise the placebo response. Doctors already routinely prescribe placebos in their practices (Howick et al., 2013). Understanding how to best optimise the placebo response is important for medicine generally, as the success of conventional treatments is also bolstered via the placebo effect.

How Can We Optimise the Placebo Effect?

1. Priming: Placebos need to look legitimate, with branding and pricing being especially important. One study found higher-priced painkillers to be more effective than discounted painkillers (Waber et al., 2008); higher prices anchor expectations upwards. The colour of pills is important too, with learned associations having an impact on how we respond to drugs. We associated blue pills with sedation, yellow pills with mood enhancement and white pills with pain relief (Cohen, 2014). Setting the scene with good branding, thoughtful design and realistic pricing is key.

2. Affect: Creating a positive therapeutic relationship between patient and doctor is vital in eliciting the placebo response; our expectations about the efficacy of the medication are largely set in this interaction. The placebo effect is enhanced when doctors are more empathetic, have a warmer approach and spend longer with their patients (Benedetti, 2013). An initial positive interaction can improve the expectation that treatment is going to work and helps to ease anxiety.

Nocebo Effect

Sometimes thought of as the ‘evil twin’ of the placebo effect is the nocebo effect, referring to the development of side-effects following exposure to a sham substance. Evidence for the nocebo effect also abounds, with sham medication leading to increased side-effect reporting for conditions including hypertension and cancer (Enck et al., 2013). Systematic reviews find that around half of placebo groups in clinical trials experience adverse effects that are attributed to the drug (Howick et al. 2018).

The nocebo effect is often observed during public health outbreaks, putting huge pressure onto health providers. For example, in 1985 ‘radioactive caesium 137�� was scavenged from a disused hospital site in Goiânia, Brazil. 120,000 people subsequently sought screening for radioactive contamination at health facilities, however of the first 60,000 people screened, only 5,000 were symptomatic. This begs the question; why do people sometimes think they are unwell when they haven’t been exposed to anything harmful?

People sometimes believe they are unwell because they re-interpret pre-existing common symptoms in light of information about the health outbreak, like fatigue or headaches. Anxiety about a health outbreak can also be sufficient in and of itself to also generate physical symptoms.

Aside from these influences, the nocebo effect can also have a very real influence on generating harmful side-effects, in the same way that placebo effects can have a tangible positive influence on the body. Expectancy, rather than conditioning, is the crucial mechanism underpinning the nocebo effect. One study found that verbal suggestion alone was sufficient to make low-level electric shocks be experienced as highly painful (Colloca, Sigaudo & Benedetti, 2008).

How Can We Minimise the Nocebo Effect?

1. Positive Framing: At present, we are often all too aware of the possible side-effects that may come about as a result of trying a new medication. Even mere mentions of such side-effects can be sufficient to generate expectations of such symptoms (Colloca, Sigaudo & Benedetti, 2008). These potential negative outcomes can weigh more heavily in our minds than the possible benefits.

Changing the conversation to make it more positive may subsequently lessen the experience of side-effects, with patients having greater expectancy that the treatment will be effective. Positive framing is needed in the doctor-patient interaction, but also on information leaflets and drug packaging, which at present tend to focus on the riskiness of medication, rather than the benefits.

2. Reducing Salience of Side-Effect Information: Research suggests that a particularly effective strategy to ward against nocebo effects is to omit information about side-effects altogether (Webster & Rubin, 2019), which poses something of an ethical dilemma. However, given that we know that people can experience side-effects just because they expect to experience them, it makes sense to be reporting on the potential for adverse experiences in a responsible way.

One example of this going wrong comes from press coverage over side-effects associated with statins. In 2013; it was estimated that 200,000 people in the UK stopped taking statins as a result. Expectancy of side-effects seemed to be sufficient for many people to change their perception of their experience of taking statins. As a result, it is predicted that the incidence of cardiovascular disease will rise by an additional 2000 cases over the next decade (Horton, 2016).

Tackling medical consent therefore poses something of a thorny issue: how do we adequately warn people of possible risks without inadvertently creating negative outcomes? There has been discussion over the idea of contextualised consent: where adverse effects are presented as more of a ‘grey area’, instead of a definite likelihood, and where doctors can withhold certain pieces of information in the best interest of the patient (Chamsi-Pasha, Albar & Chamsi-Pasha, 2017).

The use of placebos provides a cost-effective way to create tangible improvements in patients’ lives. Behavioural science is key to maximising the benefits from placebos, in part through limiting the likelihood of developing side-effects from taking them.

References

Benedetti, F. (2013). Placebo and the new physiology of the doctor-patient relationship. Physiological reviews, 93(3), 1207-1246.

Chamsi-Pasha, M., Albar, M. A., & Chamsi-Pasha, H. (2017). Minimizing nocebo effect: Pragmatic approach. Avicenna Journal of Medicine, 7(4), 139-143.

Cohen, T. F. (2014, October 13). The Power of Drug Color. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/10/the-power-of-drug-color/381156/

Colloca, L., Sigaudo, M., & Benedetti, F. (2008). The role of learning in nocebo and placebo effects. Pain, 136(1-2), 211-218.

De Pascalis, V., Chiaradia, C., & Carotenuto, E. (2002). The contribution of suggestibility and expectation to placebo analgesia phenomenon in an experimental setting. Pain, 96 (3), 393-402. Enck, P., Bingel, U., Schedlowski, M., & Rief, W. (2013). The placebo response in medicine: minimize, maximize or personalize?Nature reviews Drug discovery,12(3), 191.

Horton, R. (2016). Offline: Lessons from the controversy over statins. The Lancet, 388(10049), 1040.

Howick, J., Bishop, F. L., Heneghan, C., Wolstenholme, J., Stevens, S., Hobbs, F. R., & Lewith, G. (2013). Placebo use in the United Kingdom: results from a national survey of primary care practitioners. PLoS One, 8(3), e58247.

Howick, J. (2018, October 1). Is back pain really all in the mind?Retrieved from: https://www.pressreader.com/uk/the-daily- telegraph/20181001/281509342121606

Howick, J., Webster, R., Kirby, N., & Hood, K. (2018). Rapid overview of systematic reviews of nocebo effects reported by patients taking placebos in clinical trials. Trials, 19(1), 674.

Kaptchuk, T. J., & Miller, F. G. (2018). Open label placebo: can honestly prescribed placebos evoke meaningful therapeutic benefits?. British Medical Journal, 363, k3889.

Schrøder, C. P., Skare, Ø., Reikerås, O., Mowinckel, P., & Brox, J. I. (2017). Sham surgery versus labral repair or biceps tenodesis for type II SLAP lesions of the shoulder: a three-armed randomised clinical trial. Br J Sports Med, 51(24), 1759-1766.

Waber, R. L., Shiv, B., Carmon, Z., & Ariely, D. (2008). Commercial features of placebo and therapeutic efficacy. Jama, 299(9), 1016-7.

Webster, R. K., Weinman, J., & Rubin, G. J. (2016). A systematic review of factors that contribute to nocebo effects. Health Psychology, 35(12), 1334.

Webster, R., & Rubin, G. J. (2019). Influencing side-effects to medicinal treatments: A systematic review of brief psychological interventions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 775.

1 note

·

View note

Text

BETTER YOUR BEHAVIOURAL HANDICAP

By Dan Bennett, Consulting Director at Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science Practice

I don’t think I’m letting the corporate cat out of the bag if I let you in on the fact that, as a rule, the larger the business the slower the speed getting from insight to execution.

It’s also no secret that the more experience you have testing your thinking, the more you’ll know about what works and what doesn’t. A successful golfer doesn't just go swanning off around the course ... they dutifully spend time on the driving range first.

I'm lucky to spend a lot of time travelling the world with Ogilvy testing out behavioural science, and whilst on the move we'll often 'make our own driving ranges'. We have a nice habit of tweeting ahead at the airport or train station to see who has meaningful behavioural challenges we can contribute to whilst we're there. Fast impacts for fast learning.

One of my favourite times at the behavioural driving range was working with a struggling chain of independent nurseries.

Commercially, child care in the UK is a struggling area. It relies on its workers going above and beyond to be able offer safe and nurturing environments.

Whilst on some field work we spent a few spare hours with an owner of an independent chain of nurseries in the north of England. The staff were stretched and management had to be so reactive that they did not have the headspace to plan anything beyond the short term. They were working hard but they were haemorrhaging customers by the week and we're struggling to see why. It was hard to ask parents as they flew in and flew out being extraordinarily busy themselves.

If they could get constructive feedback, they were confident they could turn a corner. One of their proactive initiatives over the past few years was to send out a 'parent survey' instead so they could fill it out at their leisure. But again it had a dismal response rate.

It was here we noticed a behavioural science opportunity to strengthen the default to the survey.

Knowing this years survey was due to be sent out we simply changed the name from “Parent Survey” to “Your Annual Feedback Form” to make it seem like the thing to do. Not only did feedback rates more than double as a result of those four words, it was also the start of a domino effect of positive changes. Now they had the feedback they could improve the product and invest in the right places.

So where the nursery had piled all of its cash into organic menus that they thought parents wanted, they now partner with local businesses to provide services that can take the strain out of being a busy parent.

Parents dreaded the morning chaos. The local roads are congested in the morning and beyond dropping off the kids to nursery, they had to get their breakfast, and be on time for work. So the nurseries set to simplify this for parents and offer as many of the morning routine services as possible.

So now you can drop off your child and pick up your favourite coffee for your long car journey to work all in one stop. Take your reusable cup in to nursery in the evening when you pick up your child and it'll be cleaned and filled with your coffee when you drop off your child in the morning. Bliss.

What's more, now at these nurseries you can simply drop off your laundry with your child in one go. At least one of them comes back clean at the end of the day. Another load off your mind.

One of the big benefits of this is the halo effect. When the small things go right you start to think the big things do as well.

I was on a flight recently where one of the lights was flickering the entire flight, and it was unnerving to say the least. It's hard to dissociate the broken bulb with a broken plane. Conversely, if you have a great check-in experience to an airline you kind of think they've got the rest of their shit together too.

With the nurseries, fixing the small fixed the big, needless to say it was a great day at the behavioural driving range and we'll be even stronger on the course as a result of it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

PUTTING A SPRING IN YOUR STEP

8 mental shortcuts for physical training (and other life endeavours)

By Pete Dyson, Senior Consultant at Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science Practice

“no pain, no gain” “champions train, losers complain” “be badass”

These are the kind of toxic mantras that people think are needed to motivate people to walk, jog, gym, cycle, swim, box, yoga and much more in between. It sounds convincing, but there’s a problem. All this bold talk only pulls on one lever…..motivation.

There’s a big wide world beyond motivation; context, timing, opportunity, ease, understanding, social structures and many more factors that affect behaviour. What follows are lessons unearthed by me; a full-time behavioural science strategist and a part-time triathlete competing at National and European races. So, some tips are peer-reviewed and others are just plain ‘Pete-reviewed’.

Here we talk here about physical training goals, but many could be applied to learning a language, instrument, skill or even relationships (maybe).

1. Patience: consistency and timing is everything

Think of consistency like baking a cake. Even the best ingredients won’t bake in 5 minutes, there are no shortcuts here, it’s just physics. You have to take the long view and trust that over 30mins (aka 6 weeks for human fitness) the physiological effects will take place. Spontaneity is not a virtue, if you keep putting your mix in the oven for 5 minutes and out for 5 minutes, you’ll never end up with a cake, you’ll just have a luke warm stodgy blob. Training is just the same, it massively rewards a consistently good temperature.

2. Positivity: thinking faster

New research is shedding light on a long-held suspicion that the mind limits the body. Professor Samuele Marcora of the University of Kent studies this 'psychobiological model' by testing how changing people’s thoughts can change the power in their legs.

A series of studies have proven: self-talk (effectively cheering yourself on) increases cycling speed; being shown fake numbers suggesting you’re doing well makes you do even better; being shown smiley positive images increases the time to exhaustion; being told you are beating virtual competitor (you don’t even know) increases your maximum power output.

I highly recommend a book called Endure by Alex Hutchinson that summarises all this work and much more.

3. Peak End: avoid burn out

Many people in the gym and jogging in the park are absolutely killing it. It’s very impressive but quite confusing because people remember things based on the peak of the experience (the best/worst point) and how it ends.

The training-oven (yes, let’s continue that metaphor) works brilliantly at 160 degrees but it’s very costly to go to above 200 degrees.

Digging deep and bringing on the pain-face will be etched into your memory, which is fine if you can get up and do it tomorrow, but not if it puts you off doing it. In this case pain does not equal gain. Personally, I re-frame faster running sessions as ‘push as hard as I can such that I still want to run tomorrow’. Following the nice ending rule, a sociable warm down of high fives, some banter and sugary drinks is the sweetest ending you brain can get.

4. Defaults: Getting out the door

Any session is 100% better than no session. Try to ‘hack’ your way out of the door, because once a session begins then you’re basically there. Here are some ways to reduce hurdles. Here’s an ABC….

A pre-packed bag: get everything in a rucksack the night before, leave it by the bed

Breakfast in bed: have some cereal next to the alarm clock, ideally a coffee-drink too.

Count yourself out of other options: Sometimes I’ll purposefully leave my bike at work so I have to run in.

This particular advice is Olympian-approved, in so far as I tweeted it in response to a Twitter competition evaluated by Alistair Brownlee. He trains 3 sports 35 hours a week. He’s a good judge.

5. Future Self: Don’t let second thoughts come first

Even when highly motivated, I can still feel there’s a little voice (usually just before putting my kit on) that says ‘do we have to do this?’ or ‘maybe tomorrow would be better’. In this case, I don’t live in the present. I think of it like this ‘I thought it was a good idea yesterday, nothing’s changed since then, so stick with the plan”

Also, I’ve noticed no correlation between how I think I’m feeling and how I actually perform. Whether it’s tired legs, exhausted mind, slightly sniffly; all this goes out the window once the warm-up is done. Don’t judge by your present by your mood alone.

6. Targets: give me a reason!

Some people are more motivated intrinsically; the pursuit of self-improvement and contentedness. Others are more extrinsically; achieving a certain standard and getting validation from other people. In either case, nothing beats having a race, an event or a specific target. It works amazingly to focus the mind and you can construct whatever purpose you want around it. Live that imagined reality!

Note: ideally, it’s not a terrifying target, because so called ‘panic-training’ almost invariably leads to injury of the body or mind.

7. Commitments: be social

Relying on just your personal willpower is a fool's game. There are loads more sources of commitment and dedication.

A cheap one involves making your goals public; speaking, tweeting and sharing targets is ideal. Signing up with someone else is basically the crack cocaine of training motivation; it bonds and blinds you both to even needing to search for the willpower.

A friend of mine pursues a more expensive commitment strategy by signing up to the most luxurious gym because the sunk cost of a big monthly bill makes the gym more appealing. The utilitarian in me wish that he could make that £100 donation to charity instead, which might actually be more motivating as research has shown people running for charities, loved ones and good causes are more motivated.

8. Temptation Bundling: treat yourself

I believe it was Dr. Katherine Milkman that coined the term ‘temptation bundling’ to describe the act of pairing treat activities like trashy TV, podcasts and gossip with tough activities like the treadmill or house-work. Her research demonstrated that if people were given an addictive audiobook (like Serial) that only worked at the gym, then their pleasure and consistency rose considerably.

Caution: watch out for temptation-bundling’s evil younger brother called ‘moral-licensing’, where doing one small good thing acts as a constant excuse for indulging afterwards. Many Sunday afternoons and evenings have been lost to this vice.

There are many more than 8 mental shortcuts. The best ones are those you find yourself, which for many people is a hidden benefit of physical excursion – it helps you find out more about yourself.

References / Further Reading:

Brown, R. (2004). Consideration of the origin of Herbert Simon's theory of “satisficing”(1933-1947). Management Decision, 42(10), 1240-1256.

Hutchinson, A. (2018). Endure: Mind, body, and the curiously elastic limits of human performance. HarperCollins.

Marcora, S. M., & Staiano, W. (2010). The limit to exercise tolerance in humans: mind over muscle?. European journal of applied physiology, 109(4), 763-770.

Rogers, T., Milkman, K. L., & Volpp, K. G. (2014). Commitment devices: using initiatives to change behavior. JaMa, 311(20), 2065-2066.

http://thebrainflux.com/temptation-bundling

Seiler, S. Seiler’s Hierarchy* of Endurance Training Needs. https://twitter.com/stephenseiler/status/793391463694491649

Sibley, B. A., & Bergman, S. M. (2018). What keeps athletes in the gym? Goals, psychological needs, and motivation of CrossFit™ participants. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(5), 555-574.

Schwartz, B., Ward, A., Monterosso, J., Lyubomirsky, S., White, K., & Lehman, D. R. (2002). Maximizing versus satisficing: Happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of personality and social psychology, 83(5), 1178.

Zhang, Y., Fishbach, A., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2007). The dilution model: How additional goals undermine the perceived instrumentality of a shared path. Journal of personality and social psychology, 92(3), 389.

#behavioural science#mental shortcuts#consistency#positivity#peak end#defaults#goal oriented behaviour#commitment#temptation bundling#0219

0 notes

Text

HERD MENTALITY

By Zac Baynham-Herd, Analyst at Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science Practice

Groups of animals can make crazily smart or critically stupid decisions. In beehives, thousands of individuals collectively switch towards better foraging locations. This behaviour is neither triggered by a control centre, nor enforced by hierarchy. Rather, it results from effective communication and copying – otherwise known as ‘social learning’. These very behaviours which enable wisdom in crowds can, however, also lead to madness in herds. Just ask the shepherds mourning their flocks or investors their bubble stocks. Determined to crack this ancient conundrum, Wataru Toyokawa and colleagues of the University of St Andrews in Scotland, placed human ‘swarms’ under the microscope in work published last month in Nature Human Behaviour.[1]

As social animals, we seek information from others when making decisions. Good marketers perhaps know this best. Our wardrobes, career choices and even political inclinations are all shaped by social observations. As it happens, bees behave similarly. But rather than write online reviews, bees perform a waggle dance when they return to the hive. The better the food, the longer the waggle, and the more followers it attracts as a result.[2] Inspired by this, biologist turned psychologist Dr Toyokawa and colleagues built a model to capture how similar social learning strategies might also shape collective intelligence in humans.

To test their model, the team then ran an experiment. They repurposed an established learning-and-decision problem, called a ‘multi-armed bandit’, as an online slot-machine game. For 70 consecutive rounds, participants chose one of three slot machines to play, receiving pay-outs each time. Given that one slot usually paid out more, and as the decisions of other group members were always visible, players could learn to choose the best one, or just copy others. The catch was that half way through the game, one bad slot suddenly became the best slot, and stayed that way for the remainder of the experiment.

The team found that the more uncertain (harder) the slots, the poorer the players’ decisions, and the later they made the intelligent switch between slots. Using their model, the team then made the discovery that conformity increased in larger groups. The more people exhibited a given choice, the more people followed in tow – in the same way that people might choose apps based on download figures or trust Twitter accounts with large followings. Just as players in bigger groups were slower to respond to the pay-out change, groupthink can prevent market-leaders, politicians or even sports coaches from challenging dogma, dooming them to ‘poor slot’ decision-making.

For difficult tasks and within big groups, Dr Toyokawa concludes, people may rely more heavily on following the herd than learning for themselves. Crucially, such behaviour risks not only personal costs – backing the wrong horse – but societal ills like the spread of fad diets or fake news. Here, it pays to be a black sheep. Conversely, in smaller groups where individuals question prevailing logic, and for easy tasks where others are usually right, the wise decision may be to follow the flock.

We all want to make better decisions. Previous studies have identified the beneficial roles of thought-diversity, sub-grouping and flat-leadership structures in optimising ideation and problem-solving.[3] According to Dr Toyokawa, stimulating independent thought may reduce the risk of collective madness. But, beyond informing management practices, future insights and similar behavioural experiments could help illuminate consumer behaviour, understand viral trends and help us discover ‘unseen opportunities’.

As online activity grows however, so does the potential for both ‘black sheep’ and ‘herd mentality’ to proliferate. So next time you are buying stocks, or indeed socks, consider whether you are blindly following the herd. Perhaps, as Robert Frost famously suggests, taking the road less travelled by will make all the difference.

[1] Toyokawa, W., Whalen, A. and Laland, K.N., 2019. Social learning strategies regulate the wisdom and madness of interactive crowds. Nature Human Behaviour

[2] Toyokawa, W., 2019. What smart bees can teach humans about collective intelligence. The Conversation https://theconversation.com/what-smart-bees-can-teach-humans-about-collective-intelligence-110656

[3] Colvin, G., 2016. Humans are underrated: What high achievers know that brilliant machines never will. Penguin.

1 note

·

View note

Text

CONSISTENCY BIAS

STAYING TRUE TO YOURSELF

We act in ways that make us feel better about ourselves, engaging in behaviours that create, maintain or build on our sense of worth. Donations can be prompted by simply labelling people ‘helpers’ or ‘charitable’. This activates altruistic self-concepts and compels them to behave in a way that keeps this image alive.

UNSEEN OPPORTUNITY Appealing to a person’s self image, or reminding them of their characteristics and values aligned with your goal, can increase the likelihood of them behaving accordingly.

REFERENCES

Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2010). A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy:Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly.

0 notes

Text

BEHAVIOUR CHANGE PREDICTIONS FOR 2019

By Pete Dyson, Senior Consultant at Ogilvy Consulting's Behavioural Science Practice

2019 has a lot to live up to. Last year was a big one for behavioural science; we had the aftermath of Richard Thaler’s Nobel Prize and the ten year anniversary of the book ‘Nudge’, but also saw the discipline under media scrutiny with Cambridge Analytica, Facebook and Google in the spotlight and GDPR shifting the landscape of data privacy.

Here are the top 5 behavioural trends and predictions to watch out for:

Beyond nudge

Organisations are hungry to go beyond the basics, they’ve seen that tweaking subject lines and landing pages work, we expect a desire to go deeper and wider with behavioural science; to go beyond the small scale nudges. That will mean embedding behavioural insights to transform customer and user experience, brand strategy and product design.

For instance, the world is seeing Ford transform from a automobile manufacturer to a mobility company; they’re fueling this with a deeper human understanding of drivers, passengers and travel more generally.

Post-GDPR and Cambridge Analytica

A new norm is emerging as marketeers take ownership and engage in coalition enforcement to get each other to adhere to handling data ethically. To paraphrase the UK road safety slogan ‘Mates don’t let other mates handle data irresponsibly’.

We also expect the general public to awaken their consciousness and opt-out of marketing communications, to untick boxes around location/data sharing and to use social media to shame the brands that treat them badly.

Kick back against 'black box' AI and big data

Expect a wave of skepticism around the behavioural impact of big data marketing. Customers will demand transparency and kick back against AI that delivers ‘nearly there’ and ‘uncanny valley’ recommendations that are either off-the -mark or just plain creepy. Brands will then acknowledge they need to take (back) control and invest in fully understanding human truths to deliver genuinely personal touches and authentic customer service.

Simultaneously, expect a handful of brands to adopt a counter-signalling strategy of 'we don’t know who you are, so we treat everyone the same' to run counter to the perception that all experiences are personalised and only the newest or most valuable customers get treated well.

From Organisational Values to Behaviours

Given the level of disruption going on in organisational structures, behavioural science is going to play a big role in organisational change.

Expect brands and governments to go beyond values, mantras and mottoes, they’ll look for the day-to-day behaviours that demonstrate their people are thinking and working together in a new way.

Are people really walking the new talk?

Brexit Triggering Fascination with Survey Design

As prospect (or threat) of a second referendum gains momentum, expect a new wave of fascination in the psychology of survey design.

Expect dinner table and pub conversations to suddenly be populated by experts on first-past-the-post, transferable vote and Borda Count options. The debate around the psychological trade-offs between question accuracy and real-world-intelligibility will go on and on.

We predict this will be a prediction for 2020. Sorry.

There are more trends from across the business - take a look at B2B predictions here and wellness trends to watch here.

#behaviour change#behavioural science#predictions#2019#nudge#gdpr#ai#big data#organisational change#brexit#survey design#0119

0 notes

Text

BIAS OF THE MONTH: DIVERSIFICATION HEURISTIC

We hedge our bets.

When faced with a decision that involves multiple items needing to be selected for future consumption, our brains are wired to minimise risk by opting for a diverse option.

When young trick-or-treaters were asked to choose two chocolate bars from a mix of two brands, all children picked one of each. In another condition, children visited two houses and were asked to choose only one chocolate bar per house visited.

The result: only 48% picked different chocolate bars.

UNSEEN OPPORTUNITY Want to encourage variety in purchase decisions? Consider making future needs more salient than immediate consumption.

References:

Read, D., & Loewenstein, G. (1995). Diversification bias: Explaining the discrepancy in variety seeking between combined and separated choices. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 1(1), 34.

0 notes

Text

HOW TO GIVE GOOD GIFTS (AND RECEIVE THEM TOO)

By Isabel Power, Behavioural Researcher at Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science Practice

Whether it’s the office Secret Santa, proving yourself to the in-laws, or showing a loved one your appreciation, finding the perfect gift is difficult. How is it after countless sleepless nights we still end up getting the people we care about different shades of the same scarf year after year?

It’s time for behavioural science to look at the research and help target these behavioural problems to make this year more successful.

Why do we keep getting it wrong?

Insights from a study conducted by researchers at Carnegie Mellon’s Tepper Business school can help with this question.

In a nutshell, the study found that there is a mismatch between what givers think they should buy and what receivers actually want to receive. This is because givers focus too much on the ‘moment of exchange’. They want to wow the receiver in the moment rather than thinking about what the giver would actually enjoy for a longer period of time. Givers abide by a number of self-imposed “rules” which lead them to buying gifts they think will be surprising and novel. In reality, this conflicts with what the receiver truly desires; to receive a feasible gift which they actually said they wanted.

How to overcome the behavioural challenges of gift giving?

I have identified three behavioural challenges that underlie the harmful ‘moment of exchange’ pattern of present giving and have suggested a solution for each.

Behavioural Challenge 1:

Overcome present bias to give a longer term ‘present’

We do not treat time consistently, in particular we have a bias to prefer shorter term gains in the here and now over larger benefits in the future. It’s one reason why saving up seems so difficult and, in this case, the ‘moment of exchange’ seems so important.

Yang and Urminsky (2015) found that people are more likely to give a smaller bouquet of flowers in bloom than a larger bouquet of buds, even though in the latter case the recipient would be able appreciate the large bouquet in bloom for longer.

So how do we overcome this?

TIP: Change your present focus

Dan Ariely has a fantastic tip for changing temporal focus in diary management which is; ask yourself would you still accept an invitation for next year if it was actually four weeks away? This could be applied to gifting, instead of focusing on that moment imagine the receiver with that gift in four weeks. Ask yourself would they still appreciate it?

Behavioural Challenge 2:

Conquer the false consensus effect to know what’s really on their wish list

We tend to think our beliefs and preferences are more commonly shared with others than they actually are. For example, if we like chocolate, we might think everyone wants to receive a box of chocolates, when in fact our intended recipient is lactose intolerant. But how do we know what someone actually wants?

TIP: Ask for Feedback

Overcome this tendency by asking the person themselves or someone close to them what they want. Best of all if they have a list, actually follow it. You don’t need to be more imaginative. It might not seem imaginative buying someone a Spotify subscription for a year, but you can guarantee they actually want it.

TIP: Become a detective

As found by Emory University, a difficultly is that receivers are often not upfront about what they want and do not give honest feedback. It’s a familiar situation, for me at least, for someone to declare ‘I absolutely love it’ and then see the possession packed in the charity drop-off box mere days later.

Whilst givers aren’t always to blame, they can take the matter in their own hands by looking for clues. Be honest with yourself, what gifts have you honestly seen the recipient using again? If it’s none, look for other clues. Are there any items they are particularly attached to in their house? Were any of these gifts? Pay attention to how they show their appreciation of others, is it sharing an experience of a concert together? Do they like to send you positive messages? How about a message on a pillow case or a piece of jewellery? If you are still stuck, there is no shame in a voucher, they can use this to buy themselves what they really want.

Behavioural Challenge 3:

Satisfy your need to ‘wow’ through the association effect

Because of our ego, we are highly motivated to behave in ways that will form a positive impression of ourselves, particularly in the eyes of others. We need to feel that our gift will be better than any other they receive. So how do we create that ‘wow’ factor whilst getting someone the gift they actually want?

TIP: Think about how and where you give the gift

By creating a positive atmosphere, the receiver will associate the gift with a good memory. When you give your gift; try taking them to a good restaurant to exchange gifts, feed them high-quality mince pies beforehand and put on cheery Christmas music in the background. If they are enjoying the atmosphere they will have more positive perceptions of the gift. If you really want to show appreciation, try thinking about wrapping their present creatively. People remember situations tied up with emotions for a longer period of time, so how about getting personalised wrapping paper with a picture of you together?

And finally…

Remember reciprocity

It’s not all about them. Good gifting can help you too. People feel compelled to return favours so the better gifts you get, the more likely you are to receive them. It’s time to start dropping unsubtle hints.

References:

Ariely, D. (2011). Admitting to another irrationality.[Blog] The Blog. Available at http://danariely.com/2011/03/10/admitting-to-another-irrationality

Galak, J., Givi,J., (2017). Sentimental Value and Gift Giving: Givers’ Fears of Getting It Wrong Prevents Them from Getting It Right. Journal of Consumer Psychology,27, 473-479

Ward,M., Broniarczyk,S. (2011). It’s Not Me, It’s You: How Gift Giving Creates Giver Identity Threat as a Function of Social Closeness. Journal of Consumer Research, 38, 164-181.

Yang, X.A., Urminsky,O. (2015). Smile-Seeking Givers and Value-Seeking Recipients: Why Gift Choices and Recipient Preferences Diverge. SSRN Electronic Journal

#behavioural science#gifts#presents#christmas#moment of exchange#present bias#false consensus effect#association effect#reciprocity#1118

1 note

·

View note

Text

IT’S ELECTION DAY IN AMERICA: A BEHAVIOURAL ANALYSIS OF THE 2018 U.S. MIDTERM ADVERTS

By Will Fernandez, WPP Fellow & Behavioural Strategist @ Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science Practice

Tomorrow, millions of Americans will cast their ballots for midterm election candidates. Fueled by either animosity of or excitement for President Donald Trump and his political ideology, early signs predict historic turnout levels across the country. In the case of races in the U.S. Senate, where the current political divide in Congress sits on a razor-thin margin of a single-seat majority for the Republican Party, the stakes could seemingly not be any higher.

With every election cycle comes a flurry of spending on political advertising and this year is no exception. According to data from Kantar Media’s Campaign Media Analysis Group (CMAG) and compiled by Ad Age, TV and radio advertising alone have surpassed $498.4 million since April 2017. That's across only the 13 most competitive Senate races, with candidates competing in what's already become the most expensive midterm Senate TV-radio advertising battle in American history.

While David Ogilvy famously quipped that political advertising “ought to be stopped” for its “dishonest” appeal to voters, we at Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science Practice are cognizant of the increasing relevance these communications have in shaping not only the future of politics, but also the future of culture. Therefore, we wanted to turn our lens this week to the behavioural principles that are underpinning this season’s political ads as they attempt to convince undecided voters and inspire the party-faithful.

We Can’t Go Back: Trump-eting Loss Aversion

youtube

Starting our discussion is a sixty-second spot from President Trump’s political action committee (PAC) fund entitled “We Can’t Go Back”. The narrative of the ad is simple – a young mother reflects on the state of the economy, comparing the current strength of the American market to the slow growth witnessed during the Obama years. Without ever referencing President Trump directly, the PAC’s message is loud and clear – that although things are going well, they could easily slip back to the ways of the past. In behavioural science, we would call this a classic example of loss aversion - a phenomenon encapsulated by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s expression that “losses loom larger than gains” when it comes to human decisionmaking (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979).

By crafting a narrative that a vote for the Democrats is a vote for a diminished economic outlook, the ad plays towards our deeply ingrained resistance for loss. This tactic is also reminiscent of Ronald Reagan’s iconic 1984 re-election spot “Morning in America”, where the narrator paints a picturesque scene of economic growth and vitality in the country and asks why the viewer would ever vote to go back to the uncertainty of the Jimmy Carter-led Democratic Party.

What’s Best for Michigan: Uncommon Messengers

youtube

Moving from the national narrative to one of the most competitive races in the American Heartland, this next spot entitled “What’s Best for Michigan” comes from Democratic Senator Debbie Stabenow as she attempts to out-maneuver Army combat-veteran-turned-Michigan-businessman John James. To counteract the belief that she is out of touch with rural Michigan voters, Stabenow has given the focus of this spot over to rural conservative farmworkers who view her as “a different kind” of politician. By using conservative advocates to reach her target audience, Stabenow’s team is utilizing the messenger effect – we are heavily influenced by who communicates information (Schjoedt et al., 2010).

This tactic has been adopted previously in two separate spots both known as “Confessions of a Republican” – first crafted in the 1964 presidential race between Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson and Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, and second during the most recent presidential race between President Trump and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

Tough As Texas: Association Effects Are Bigger in Texas

youtube

Going from the Far North to the Deep South, the next spot comes from Texas Republican Senator and 2016 Republican nominee contender Ted Cruz. In “Tough As Texas”, Cruz attempts to expand and connect the Texas brand to his own personal mission of public service. By trying to connect the values and characteristics of the state of Texas to his own personal brand, Cruz, in turn, has dialled into what are known as association effects – we can elicit automatic behavioural effects when exposed to new brands when those brands are associated with tried and true brands, such as Texas exceptionalism (Dimofte & Yalch, 2011). By embodying the Texas brand, Cruz hopes to ride the associated goodwill to success on Election Day.

Many politicians have attempted to embody the ethos and associative effects of their state. None, however, have done it quite to the extent as former President Barack Obama – who found a way to interweave his personal narrative into a broader story of the American experience through multiple ads in his 2008 Presidential campaign, including the sixty-second “This Country I Love” spot. By connecting a personal brand to a beloved legacy brand, one has the opportunity to imbue many of the associative effects.

Dead Wrong: Nostalgia in Old West Virginia

youtube

Finally, we head to the old Mountain State of West Virginia where incumbent Democratic Senator Joe Manchin attempts to continue his service in the Senate for a fourth term in a state that voted overwhelmingly for President Trump in 2016. While Manchin has long been considered a historic “Blue-Dog” centrist Democrat, his most recent spot “Dead Wrong” extenuates that connection through a call to action that shows the senior Senator literally willing to bear arms for what he believes in. While certainly over-the-top theatrically, Manchin’s message draws heavily on humanity’s unique affinity for nostalgia – we are far more likely to agree with the information or decision presented to us when primed with a sense of longing for what used to be (Muehling & Sprott, 2004).

Previous iterations of brilliant executions of nostalgia-laden political ads include California Governor Jerry Brown’s 2010 attack ad “Why I Came to California” used against the Republican nominee and former Hewlett-Packard Chief Executive Meg Whitman. By reminding the viewers of the nostalgic positives of the past, the advert’s message becomes more persuasive in getting viewers to believe in the benefits of the future.

Learnings from the Campaign Trail

While many of us in the advertising industry can hold disdain for the cheesy, dishonest, and downright embarrassing tenor of some political ads, we would be remiss if we did not take them as a serious barometer for our own work. If we are to break through the clutter and overcome the growing sense of compassion fatigue that dominates our culture, then we would be wise to better understand the behavioural levers that successful politicians have adeptly managed throughout history. Without greater understanding, we are doomed to continue making ads like this one.

Sources:

1. Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263-291.

2. Schjoedt, U., Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H., Geertz, A. W., Lund, T. E., & Roepstorff, A. (2010). The power of charisma—perceived charisma inhibits the frontal executive network of believers in intercessory prayer.Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 6(1), 119-127.

3. Dimofte, C. V. & Yalch, R. F. (2011). The Mere Association Effect and Brand Evaluations. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21, 24–37.

4. Muehling, D. & Sprott, D. E. (2004). The Power of Reflection: An Empirical Examination of Nostalgia Advertising Effects. Journal of Advertising, 33(3), 25-35.

Note: The opinions expressed represent the viewpoint of the author alone and in no way represent those of Ogilvy or Ogilvy Consulting.

#behaviourchange#politics#midterms#behavioural sciences#advertising#lossaversion#messengereffect#associationeffect#nostalgia#1118

0 notes

Text