Text

Beaver Steals Fire: A Salish Coyote Story

Amani Kafeety, Myshiia Pinney-Dimock, Emily Dabrowski, Tatjana Wagner, Alyla Kler

Description of Resource and Rationale

Beaver Steals Fire is a picture book by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. The story is told by Salish elder Johnny Arlee and beautifully illustrated by the tribal artist Sam Sandoval. It originates from the stories of the Salish-Pend d’Oreille people.

This book conveys the story of Coyote and his animal friends, who climb up to the sky after dodging several threats, and steal fire from the animals living there to bring down to earth to share with other animals and humans. The meaning behind the story is to highlight the importance of fire for survival, to revitalize its use in modern day Indigenous practices, as well as to teach about exhibiting respect for fire and the environment.

As a group, we chose this resource not only for its content but also for its various components, which honor its origin in the Salish-Pend d’Oreille tradition. The dedication acknowledges Elders and ancestors of these tribes, contemporary fire warriors, and children. This is particularly important as it recognizes the role that Elders play in preserving traditional and oral knowledge in Indigenous cultures. Additionally, it honors fire in a way that is often neglected nowadays. The resurfacing of a topic such as this can also serve as a platform to discuss other traditions and values that are inherent in the Indigenous cultures that have been repressed, or to discuss topics related to the significance of fire like the relevance of land and life.

Furthermore, Beaver Steals Fire contains a note to the reader requesting that they keep in mind a seasonal tradition briefly mentioned in order to value this aspect of their culture, which subsequently helps connect the readers to the importance of such traditions in Indigenous heritage. Specifically, the story must only be shared by Elders during the winter when snow is on the ground, which invites students and teachers to engage in this tradition and further explore their rich culture. Likewise, this book contains a note to teachers and parents, and information on the artist, the storyteller, and The Fire History Project, which is a project aimed at increasing public awareness and appreciation for the use of fire to manage land. The motive behind this project can help illustrate to children the reality behind the story and deepen their understanding of such values. Lastly, the back of the book provides a Guide to Written Salish, as traditional Salish names were used in the text. It also reintroduces the traditional Salish language that has since been taken away from them.

This resource is recommended by the BC Teacher's Federation and the First Nations Education Steering Committee. Therefore, it can be found in several local and public libraries. It can also be purchased through online websites such as Amazon, Strong Nations, and in various bookstores.

Role of Indigenous Knowledges

This story reflects on the importance of land and the natural environment in the lives of the Salish peoples, as derived from a story that has typically been passed down via oral storytelling for many generations. The story is of particular significance especially as it is depicted by the tribal artist Sam Sandoval and the storyteller Johnny Arleen, whom both belong to the Salish peoples, and have deep-rooted connections to the story told and can relate to its cultural significance in their own lives. The Salish-Pend d'Oreille and Kootenai Tribes have also been credited for their involvement and approval of publishing this storybook that embodies important cultural elements that are of important significance and hold immense value for the Salish-Pend d'Oreille peoples. Additionally, the story illustrates an engaging and thoughtful storyline that emphasizes the inclusion of the Salish-Pend d'Oreille language linguistics components. This could be viewed as a testament to preserving the Salish-Pend d'Oreille language, in which its very existence has been threatened by two centuries of colonization.

The significant role of fire in the Salish-Pend d'Oreille people’s ways of living and survival is the key focal point of this story. Land is an additional important concept depicted throughout the illustrations and themes in this storybook, which reflects on the Salish-Pend d'Oreille people's connections to life in the Northern Rockies in northwestern Montana. This story draws the connections between each of the important elements that comprise Indigenous identity and are essential to their holistic well-being and survival: connections to land, sources for food, utilization of water, and other natural sources, and how fire links these all together. Recognizing the significant value of fire to the Salish-Pend d'Oreille peoples, it is fitting that they have committed to molding their cultural practices and developing a traditional story around it to be passed down across generations. In the wake of the dire impacts of colonization on preservation and existence of Salish-Pend d'Oreille cultural identity, these stories have been passed down for thousands of years as a means of preserving this history and culture for future generations to come. This story is an overall testament to the importance of preserving and taking good care of the natural environment, and challenges existing worldviews on the conceptualization and response to environmental outcomes (e.g. natural disasters, forest fires, floods, etc.).

Challenges and Benefits of Using this Resource

Beavers Steals Fire: A Salish Coyote Story becomes a valuable resource when introduced in elementary school classrooms as it covers a variety of teachable topics and serves as an engaging platform for young audiences to begin discussions about Aboriginal history and traditions.The first benefit of using this resource in grade 2-3 classrooms is that the engaging story provides an inclusive introduction to the topics of Salish-Pend d'Oreille peoples. Currently, children from diverse backgrounds join together in classrooms and are taught in a relatively persistent manner. However, this book resists this typical instruction, and allows children to construct their own meaning from the story, thereby educating themselves. The second benefit of using this story as part of a learning practice is that it shares traditional knowledge that has been passed down through generations, and students are able to experience a new setting for learning. By sharing this story as part of a circle activity students learn the importance of critical thinking, by listening and interpreting the story for themselves before a group discussion takes place. The third benefit of this resource is that while being a storybook geared towards younger children it still provides context by including a note to teachers and parents at the end, background information on the artist and the storyteller, discussing the Fire History Project, a note to the reader and acknowledgements. By including each of these the resource itself can be seen as honoring and respecting the traditions of Salish-Pend d'Oreille Peoples. There is also a phonetic alphabet provided to break down the language barrier as the names of characters in the book are written in Salish. Fourthly, as this resource is a part of the Fire History Project which was designed by the Salish-Pend d'Oreille community is used to educate and raise awareness of Salish peoples use of fire and how it was used to shape the land. In this way the storybook allows young minds to start thinking and being aware of other perspectives that challenge the westernized worldview of what fire represents.

However, the use of this resource as a teaching tool in classrooms brings challenges as well. The first is the way in which the storybook is introduced to students; if it is not incorporated into a lesson plan, the story could lose meaning. A major concern is whether children will be able to learn a lesson from this story without being provided the proper context and understanding prior to the reading. In order for this book to be a valuable resource the teacher must be confident in their ability to discuss alternate perspectives voiced by students. A second challenge is that perhaps because the story is physically printed, the traditional knowledge of the story itself loses value. The story is traditionally told orally by Elders, and consequently students may lose some of the story’s meaning by only experiencing the story in written form. Lastly, it may be possible that the artist’s illustrations could cause the readers to misinterpret parts of the story, thus creating a conflicting perspective of the true meaning behind the story.

How could this Resource be used in the Classroom?

This storybook is a great resource for educators to use in the classroom, and it can be used in a variety of ways. According to the BC teacher’s federation, this book targets students who are in grades 2-3. It covers a variety curriculum themes such as relationships, traditional knowledge, collaboration and cooperation (First Nations Education Steering Committee & First Nations School Association, 2016). In order to authentically share this story with students, it is crucial for the educator to read the acknowledgement and note to parents/teachers. The reason being that the note states how the story is meant to be shared according to Salish-Pend d’Oreille cultural tradition. Specifically, it tells educators to only share this story during November, or when there is snow on the ground, as this is the time of year that elders of the Salish-Pend d'Oreille community would share this knowledge with their people. Also, the note for teacher and parents located at the back provides important context for the story and traditions of the Salish-Pend d'Oreille people . It informs educators why the story is shared, where it comes from, the significance behind it, and its connection to land and the community. In addition to this knowledge, this resource is also part of a larger series of educational material, which includes a video, documentary and lesson plan. This would allow educators to create in depth lesson plans that could extend over a period of time, and integrate curriculum from various subjects such as science and language arts. Overall, this resource provides a lot of authentic cultural context that an educator can use to introduce classroom themes and integrate curriculum.

Not only can this resource be used to provide cultural context in the classroom, but there are many activities that can be done with it as well. According to Jo-ann Archibald (1994), one way educators can use story books in the classroom is by establishing a talking circle. Everyone must sit in a circle while the story is being shared, as this is a symbolic gesture expressing the equality among us. After the story is told, the teacher would check in with everyone’s understanding and ask what the story mean to them. This would allow the teacher to hear everyone’s individual understandings, and expose everyone to different perspectives. In doing so, students are presented new meanings of the story, and can therefore broaden their understanding of it. Once group discussion about the story is generated, the educator can ground the lesson in curriculum by referring to traditional ways of sharing stories and oral tradition. For example, what are some of the ways we share stories with each other? In addition to the talking circle, educators can also use a communicative approach to incorporate this resource into their curriculum. Often, students struggle with literacy skills. One way teachers can help strengthen the development of these skills is by encouraging students to read at home. Since this book is geared towards young children, educators could establish a reading activity, where students are given books to read at home with their parents. The parents can then read this story to their children, creating a connection between classroom and community. By doing this, the parents are passing down the knowledge and moral of the story to their children, just as elders of the Salish-Pend d’Oreille people would do through their own oral traditions. If an educator was doing a lesson on traditional knowledge, this would create a deeper connection to the classroom material. Also, it would encourage students to develop their own literacy skills, while embracing culture. All in all, this resource is a solid tool for educators to use in the classroom.

References

First Nations Education Steering Committee & First Nations School Association (2016). Authentic First Peoples Resource. Retrieved from: http://www.fnesc.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/PUBLICATION-61502-updated-FNES C-Authentic-Resources-Guide-October-2016.pdf

Archibald, Jo-Ann. Storyguide: Beginning the Journey. In: First Nations Journeys of Justice. Building Bridges of Understanding between Nations. 1994. Retrieved from: http://www.lawlessons.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/Journeys%20of%20Justice%20-%20Grade% 205.pdf

Castellano, M. B. (2000). Updating Aboriginal traditions of knowledge. In G. J. S. Dei, B. L. Hall & D. G. Rosenberg (Eds.), Indigenous knowledges in global contexts: Multiple readings of our world (pp. 21-36).

Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. Beaver Steals Fire. A Salish Coyote Story. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln and London. 2005.

0 notes

Text

Wild Berries by Julie Flett

Randeep Dhillon, Pavneet Dhanoa, Manjot Minhas, Pravneet Roopra

“Wild Berries” by Julie Flett is a children’s book aimed at children aged 3 to 8. Julie Flett is Cree-Métis and currently lives in Vancouver, B.C. The book consists of a short story about the traditional wild blueberry harvest. It is written in English, yet also includes selected equivalent words in n-dialect Cree. The book includes beautiful illustrations that provide a serene visual context for the sentences on each page. This short story highlights the lesson of learning from elders, as a relationship between a young boy and his grandmother is depicted. The story also provides a lesson about interaction with animals, and the importance of sharing.

We chose this resource since it is written and illustrated by a reputable author who is of Métis descent herself. Julie Flett has received multiple writing awards including awards from Aboriginal organizations (Julie Flett, n.d.). The story is concise, and has embedded Cree language in the sentences which encourages readers to engage with the language due to the simplistic integration of it. It includes excellent illustrations that help narrate the story and also provides peaceful visuals of nature for the target audience. The imagery helps readers visualize the interaction with the various animals which are highlighted in the story. It helps the reader engage the mind and heart with the environment. Additionally, this book also includes a pronunciation guide and a glossary of Cree words. We found this to be very useful as the language is complex, especially for the target readers. There is also a blueberry jam recipe included at the end of the book which can be used for interactive activities in the classroom. This resource is easily accessible in various libraries. It can also be purchased online at multiple bookstores, for example it is readily available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.ca/Wild-Berries-Julie-Flett/dp/1897476892.

The story of “Wild Berries” seems to come from either the Cree or Métis nations (the book says the author is Cree-Métis). According to many researchers, the Métis people are said to have both French and Aboriginal descent. (Ouelett & Hanson, 2009) The language for both Métis and the Cree are unique. As the book “Wild Berries” mentions before starting the story, there are several different and unique dialects of the Cree language. Each dialect has its own way of pronunciations, vocabulary and grammar use. The dialect that our group has read is known as “Swampy Cree” in N-dialect that originated from the Cumberland House area. Swampy Cree is also referred to as “Nēhinawēwin” as mentioned in the book. The author provides us with a pronunciation guide at the back of the book, as well as, some more information about the Cree language.

Respecting elders and learning from the older generations is something that many cultures value. In Indigenous cultures especially, this is something that is very much valued in the community. The raising of a child in these communities is not the sole responsibility of the parents, but it is an effort that the entire community makes as a group. In simpler terms, the community raises the children. Elders plays the role of providing knowledge, and sharing their wisdom among the younger generations. Their significant role is to share their stories and past experiences in order to preserve culture and to help the younger make decisions. (“The Elders”, 1996) This book puts emphasis on that strong connection between children and their elders. Just like Clarence in the story, there are many lessons that children can learn from spending quality time with their grandparents and elders in the community. The grandmother in the story teaches Clarence songs, how to be alert for bears and also how to pick nice berries. In addition, it teaches children how to be respectful of their elders and the animals in the forest. In many Indigenous communities the relationship between the young and the elderly is something that is crucial to the children's learning and development within the Indigenous community.

In addition to bringing emphasis to the role of elders in the community, the role of nature and land in learning is also covered in the book. This is represented in the book in various ways. The story’s setting is in a forest, which is a large indicator of nature in the story. Clarence's’ journey involves picking berries and interacting with the wildlife in a peaceful and respectful manner. Many Indigenous cultures believe in giving back to the environment whenever possible because their lives are structured around what the land had to offer. This is reflected in the book when Clarence shares his blueberries with the animals in the forest. Giving back to the land has always been significant to Indigenous cultures.

Since this resource could potentially be used for education purposes, it is important to discuss the benefits and challenges of using this book. “Wild Berries” is an easy read, and is a reputable resource to provide a glimpse into the Indigenous peoples’ lifestyle. Julie Flett is of Cree-Métis (as stated at the back of the book) descent herself, and is an award-winning writer and illustrator. In fact, Julie received the Aboriginal Literature award in 2014 (Julie Flett, n.d.). Apart from being written by an accredited author, “Wild Berries” offers valuable educational and Indigenous knowledge. The story of Clarence picking berries with his grandma, portrays a positive relationship between two separate generations. The story displays positive experiences such as giving back to the land which is illustrated by Clarence giving some of his berries to the animals in the woods when his bucket was full. The book shows a variety of animals living in the woods, and portrays a loving and caring relationship between humans and animals. Such display of affection between different organisms and the land itself allows young children to learn important lessons of life through a fun and interactive way. The book includes Cree words in the colour red following the English word on the page which brings a nice touch of contrast to the pages while spreading knowledge of the Cree language. The book has a calming effect, especially visually because the landscape is illustrated as a clean and open space, and the white space on the pages also adds to the neatness. The story is easy to read, understand, and explain to young children so, there is a lot to gain from this book.

There are some challenges to using this resource in a teaching or general setting. One critical point is that the writer does not explain the cultural-specific use of wild berry jam recipe provided at the end of the book. The recipe looks great, but there is no context provided. It is uncertain whether the Cree people use this recipe regularly in their daily lives, or whether it was something that was made on special occasions. Also, it is not stated if the Cree people themselves use that recipe. If the author had provided some background information about the origin of the recipe and its use for Indigenous people, it would have been more beneficial for the recipe to be included. The ambiguity of the recipe could lead to inappropriate use of Indigenous knowledge and culture so, it’s important for both teachers and parents to have such information before passing it on to the younger generations. Another challenge of using this resource is that it is not directly connected to local Indigenous territories in the lower mainland since Cree is not a language of Indigenous communities in British Columbia. This point may make the book less relevant to students in B.C.

“Wild Berries” is a great resource to use in a classroom setting for younger children, since it can be used for a target audience of 3-6 years old. This can be read by the teacher to children or it can be read by children on their own. There are many pictures with limited text, making it suitable for both situations. However, it would be best if children are reading this book with a parent or teacher as it would aid them in learning the lessons of the novel that are not explicitly stated. As mentioned previously, for example, Clarence picks berries for himself, however when his bucket is full he offers berries back to the birds. This symbolizes the importance of sharing with others, and can be further enforced when children read with someone guiding them. If an older audience is the targeted audience of the book then it is possible to engage them further. They can be asked to read the book and do an assignment that involves thinking critically about the resource in terms of its importance to Indigenous culture. In this way it is possible to encourage them to think about the meaning behind the book such as lessons about family, environment, and sharing. Therefore, even if the resource is used to target an audience that is more than capable of reading the content, it can still be engaging as it has a lot of teachings to offer.

Another important aspect of this book that can be used in a classroom setting is the jam recipe provided at the end of the book. This recipe can be introduced by the teacher so that the students can go home and make the jam with their parents, or the teacher can prepare it and bring it in for the students. It could also be helpful to send the recipe out to parents and encourage them to bring it in to share with the class. This allows more engagement with the book because the children are able to perform an activity related to the story. Reading the story before introducing this activity can encourage them to go home and use this recipe which will make them more likely to remember this story and its lessons in the future. The book also contains words translated from English into n-dialect Cree. These words are introduced to the children through the book, however it is also possible to assign the children an activity or assignment that encourages them to actively learn the words. This would make it possible to learn the language for the children. When doing so it is important to make sure that the words are pronounced correctly, hence the teacher would be required to learn the correct pronunciation from the guide provided in the book and even use other resources to teach the children these words accurately. This could be a challenge for a non-indigenous teacher, but it would be beneficial to find a video online or bring in an Elder to help children learn the words correctly.

Overall, Wild Berries is an appropriate and beneficial book to use as an educational resource. The story portrays important life lessons, such as sharing, caring, respectful relationships with the elderly, and living in harmony with nature, all of which are key to Indigenous peoples’ culture. This resource is able to engage a wide variety of audiences, while also offering knowledge of the Indigenous culture and its values. Since the resource has the capability of offering numerous benefits to an educational setting, we believe that it would be valuable and rewarding for the children, parents, teachers, and communities involved.

References

The Elders. (1996). Retrieved from http://www.creeculture.ca/content/elders

Flett, J. (2013). Wild Berries. (n.p): Simply Read Books.

Julie Flett. (n.d.). About. Retrieved from http://julieflett.com/about

Ouellet R. & Hanson E. (2009). Métis. Retrieved from http://indigenousfoundations.web.arts.ubc.ca/metis/

0 notes

Text

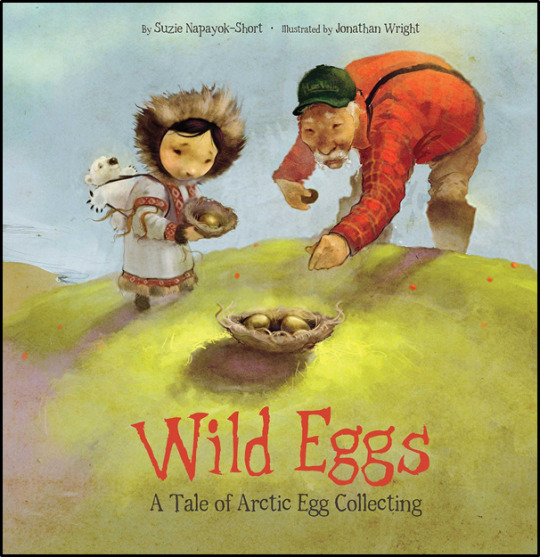

“Wild Eggs: A Tale of Arctic Egg Collecting” by Suzie Napayok-Short

Sarah Savić Kallesøe, Jiafu Jiang, Kye Fedor, Xinyu (Billy) Chen

Napayok-Short, S. (2015). [Cover of "Wild Eggs: A Tale of Arctic Egg Collecting"].

Resource Description, Author Credibility, and Access

“Wild Eggs: A Tale of Arctic Egg Collecting” is a children’s story which focuses on the modern-day challenge of Indigenous youth connecting to their ancestors. Akuluk, the protagonist, is a young girl living in a Canadian city who is sent to her grandparents in Nunavut for the summer vacation. But Akuluk is not interested in visiting Nunavut and would rather visit her friends. With the guidance of her grandparents, she soon learns the Arctic to be an exciting place and experiences the Inuit language, culture, and traditional food. Akuluk’s grandfather introduces her to wild duck egg collecting, which soon becomes a passion of hers. As Akuluk’s grandparents teach her about their traditional lifestyle, Akuluk creates deeper connections with her grandparents and her ancestral roots. Initially, Akuluk is reluctant to visit Nunavut, but through her grandparents’ teachings, she develops an appreciation and interest in her Indigenous roots.

Our team chose to examine “Wild Eggs” because its theme of cultural reconnection reflects a common challenge faced by urban Indigenous Canadian youth today. This story is also an excellent introduction for students to the modern-day lifestyle of Inuit-Canadians, the Inuktitut language, and the fundamental Indigenous values of sustainable harvesting and transgenerational learning. Basic words of the Inuit language, Inuktitut, are discussed in the story and a pronunciation guide is included near the end. We find these tools to be especially helpful for educators and students without previous experience with Inuktitut and are wanting to learn. Accompanied by detailed illustrations and introductory-level language, Akuluk’s journey to understanding her ancestry is appropriate for elementary-aged children. The publisher, Inhabit Media, recommends this story for readers between 5 and 7 years old. We believe this resource to be a valuable tool for educators to introduce the Inuit culture and the challenges of cultural preservation among Indigenous-Canadian youth.

Through our evaluation, we find this resource to be an appropriate representation of the Inuit culture in Nunavut based on the credibility of the author, illustrator, and publisher. The author, Suzie Napayok-Short, was born and raised in Iqaluit, Nunavut. Napayok-Short attended residential school during her childhood and identifies herself with Inuit ancestry. She currently works as an Inuktitut translator and interpreter for government departments across the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Canada. In addition to her government work, Napayok-Short also aids residential school survivors through legal processes. The inspiration for the fictional story "Wild Eggs” was based on egg-hunting trips with her father during her childhood. The illustrator, Jonathan Wright, currently resides in Iqaluit, Nunavut and has illustrated for a variety of newspaper, magazines, and books, specifically focusing on creating artwork for Indigenous stories. His illustrations in the tale of “Ava and the Little Folk” by Alan Neal and Louise Flaherty was shortlisted for the 2014 Silver Birch Express Award. Lastly, the publisher, Inhabit Media, is an Inuit owned company and currently the only publisher based in the Canadian Arctic. Inhabit Media’s vision is to voice the authentic traditional stories of the Inuit peoples and support Arctic Indigenous authors. Beyond their publishing responsibilities, Inhabit Media also works alongside governments and nonprofit organizations to strengthen and preserve the Inuit language. Based on the credibility and working histories of Suzie Napayok-Short, Jonathon Wright, and Inhabit Media, our team believes “Wild Eggs” to be a reputable Indigenous-based resource for educators. This story can be publicly accessed from the Simon Fraser University, University of British Columbia, City of Vancouver, and City of Surrey libraries. The APA citation is as follows:

Napayok–Short, S. (2015). Wild Eggs: a tale of Arctic Egg Collecting. Iqaluit, NU: Inhabit Media Inc. English version ISBN: 978-1-77227-025-9

This story is also available in Inuktitut. ISBN: 978-1-77227-036-5

Indigenous Content

“Wild Eggs” is a story full of rich information and content told from the perspective of an urban indigenous youth connecting to her roots. This story speaks to language-related knowledge, transgenerational teachings, and respect for the land. Indirectly, it teaches the reader about the biodiversity of life in the tundra, customary clothing, and local food gathering. The grandfather embraces the role of an elder by sharing his knowledge of the Inuit language, sustainable harvesting, and traditional food preparation to Akuluk. He is the story’s figurehead of knowledge and learning, teaching us the fundamental Inuit values. The role of introducing Inuktitut words within the story is to reflect the core values of Inuit culture. A key Inuktitut word introduced by the Grandfather is Piusituqattini, which speaks to the notion of taking only what is needed from the land, in other words, sustainable gathering. While egg collecting, Grandfather explains the concept of Piusitqattini to Akuluk, stating that nests with more than four eggs should not be disturbed because if a mother bird notices one of her eggs are missing, she will abandon the nest. He further explains that if too many nests are disturbed then the future generation of birds would be at risk of dwindling, resulting in fewer eggs for the future children to pick. The role of language helps the reader become familiar with the Inuit culture, as well as encourages the reader to conceptualize Inuit values like Piusitqattini. Grandfather’s teachings of traditional Inuit lifestyle and Inuktitut words, such as Piusitqattini, educate the reader to be considerate of the beings we share our resources with. The repetitive use of Inuktitut language acquaints the readers with certain Inuit values and acts as a source for children and readers to share their growing knowledge of Inuktitut with their peers. Additionally, Grandfather’s teachings about culture, such as traditional foods and clothing, play an important role in “Wild Eggs” of introducingreaders to the tundra environment and the modern-day Inuit way of life. An example of culture's role in “Wild Eggs” is Akuluk’s grandparents explaining the value of her parka, which is made of muskrat, wolf and wolverine fur. The grandparents continue by describing the animal diversity of the tundra and the important role that the parka plays in Inuit culture. As the Grandfather explains, the parka has a purpose of preventing bugs from bothering us and it keeps the body very warm in the cold Arctic weather. The parka allows people to hunt, gather, and perform daily life activities outside without freezing or being swarmed by bugs. This description of the parka gives readers insight of the activities and needs of the Inuit people which can be accomplished while wearing a parka, such as collecting eggs and hunting. The story, “Wild Eggs” eloquently provides young readers an introduction to the tundra environment and the traditional Inuit values. The inclusion of language-based teachings by the elders in “Wild Eggs” acquaint the reader with the tundra environment, elder to youth transgenerational sharing, and the rich culture of the Inuit peoples.

Advantages and Challenges of this Resource:

While this storybook is only thirty-three pages long, the content provides a vast number of opportunities for educators to introduce the Inuit culture in their classroom. This resource is advantageous in that it includes basic Inuktitut words and concepts surrounding the themes of family ties, love, traditional customs, and the people’s relationship to the land. Weaving Inuktitut words into the story emphasize the values of the Inuit culture. Since most readers are likely not familiar with Inuktitut, learning the native tongue may make the concept of the Inuit culture more tangible and relatable to students. However, some educators may hesitate to use this book as some Inuktitut words may be difficult to pronounce. For this, the author included a pronunciation guide of all the mentioned Inuktitut words, making it easier for readers to connect with the language. The credibility of the author and illustrator prove to be another benefit of this resource. As mentioned earlier, Suzie Napayok-Short and Jonathan Wright both resided in Iqaluit, indicating that the story content and artwork were inspired by the lived experience of Nunavut rather than imagination. This provides a rich description of the Nunavut geography, traditional customs, and animal diversity, helping readers connect to the characters and the setting. This proves especially useful for classroom education as most readers will not likely have their own experiences of the North to refer to. Many educators are careful in selecting content to present to their class, especially with Indigenous related stories as many often misrepresent the culture. Fortunately, the credibility and Indigenous experience of this book’s author, illustrator, and publishing company provide a reason to believe that the content was researched and verified before publication. Knowing this, educators may feel comfortable that they are appropriately representing the Inuit culture even if they do not have any direct experience with the culture.

This resource offers many advantages, but there are a few limitations. Firstly, as this story speaks to Inuit tradition, it appropriately takes place in Canada’s north. However, many students, especially the younger grades, may find it difficult to relate to Nunavut’s setting since it is a rather remote region of Canada. To help students connect to the setting, the instructor may consider teaching about how the Arctic’s geography is vastly different from the students’ hometown. This could include topics such as the native vegetation, seasonal changes, and animal diversity. By drawing attention to the new context, the students may find it easier to envision and relate to Akuluk’s story. Secondly, while the story setting is explicitly stated to be in Nunavut, a region or town is not mentioned. Knowing the specific town may allow educators to show the students where the story takes place using a map, rather than referring to the whole territory of Nunavut. However, this limitation does not discredit or outweigh the benefits of this resource. Finally, the publisher, Inhabit Media, recommends this story is suitable for the 5 to 7 years age range. However, our team believes the length of the passages may be slightly difficult for this age category. Fortunately, this can be addressed at the discretion of the educator.

Applications to Teaching:

The message conveyed by this storybook opens the door to a necessary discussion of the cultural conflict faced by urban Indigenous youth in Canada. Akuluk’s story speaks to a unique challenge faced by Indigenous youth today, which is deciding how prominent of a role their ancestral culture will play in their modern-day life. The intense and prolonged genocide make this issue distinctive to the Indigenous peoples of Canada. As a result, youth may feel detached from their Indigenous roots and be at a loss as to how they can reconnect or if they even should. Akuluk’s story is an excellent introduction to an elementary level discussion of how Indigenous youth may feel distant from their heritage. After reading or listening to Akuluk’s story, the instructor may open a discussion by asking the students some of the following questions: “Why do you think Akuluk was living so far away from her grandparents?”, “Do you think Akuluk would have learned about her ancestor’s lifestyle, like egg collecting, in her school the same way her grandfather taught her?”, or “Why do you think Akuluk did not want to go to Nunavut?”. These questions may begin the discussion of why some Indigenous youth may feel disconnected from their heritage.

After opening the discussion of the challenges faced by urban Indigenous youth, presenting a lived example may help students understand the magnitude of these issues. Our team suggests the story of Autumn Peltier, a 13-year-old Indigenous-Ontarian fighting for access to clean water within the Canadian First Nation communities and across the world. Autumn comes from the Wikwemikong First Nation and has been advocating for clean water since she was 8-years-old. She has been named a water protector and has been nominated for the International Children’s Peace Prize. In a country where clean water is an assumed right, it is absurd to hear that many still live without potable water, and a majority of that burden is shouldered by the Indigenous communities. Her advocacy for sustainable access to clean water closely aligns to an Inuktitut concept Akuluk is introduced to by her grandparents: Piusitqattini, the act of taking only what you need from the land so other species and future generations can flourish. Autumn’s lived story and the fictional story of Akuluk exemplify the challenges faced by present-day Indigenous youth and the Indigenous values of transgenerational sharing and sustainable living. Our team believes these two Canadian-based stories are viable tools for educators seeking to open a classroom discussion and further the understanding of the challenges faced by Canadian Indigenous youth.

The following are links to just some of the news story of Autumn Peltier. Please refer to the “References” section for full APA citation.

www.cbc.ca/news2/interactives/i-am-indigenous-2017/peltier.html

www.theindigenousamericans.com/2017/10/11/13-year-old-indigenous-girl-nominated-global-peace-prize/

www.cbc.ca/2017/meet-autumn-peltier-the-12-year-old-girl-who-speaks-for-water-1.4168277

Sapurji, S., Karapita, M., & Alex, C. (2017, June 21). [Autumn Peltier]. Retrieved November 1, 2017, from http://www.cbc.ca/news2/interactives/i-am-indigenous-2017/peltier.html

References

CBC News. (2017, June 20). Meet Autumn Peltier - the 12-year-old girl who speaks for water | CBC Canada 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from www.cbc.ca/2017/meet-autumn-peltier-the-12-year-old-girl-who-speaks-for-water-1.4168277

Napayok–Short, S. (2015). Wild Eggs: a tale of Arctic Egg Collecting. Iqaluit, NU: Inhabit Media Inc. English version ISBN: 978-1-77227-025-9

Sapurji, S., Karapita, M., & Alex, C. (2017). Autumn Peltier. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from http://www.cbc.ca/news2/interactives/i-am-indigenous-2017/peltier.html

The Indigenous Americans. (2017, October 11). This 13-Year-Old Indigenous Girl Has Been Nominated for a Global Peace Prize. Retrieved October 30, 2017, from http://www.theindigenousamericans.com/2017/10/11/13-year-old-indigenous-girl-nominated-global-peace-prize/

0 notes

Text

How the Eagle Got His White Head

Holli Lang, Joyti Gill, Pavin Rana, Lucy Marshall, and Jennifer Wijaya

The text that our group has chosen to review on is How the Eagle Got His White Head, written by Jane Chartrand and illustrated by Zaawaazit Mkwa Tsun. The small picture book opens with a grandmother, referred to as Nokomis, and her grandson Heyden. Nokomis tells Heyden the story of how the Eagle, named by the creator as the leader of the birds, got his white head. In the story, white Eagle ruled the skies whereas Bear was the leader of all the creatures on earth. As the years went by, there grew to be too many birds in the sky and animals on the earth, and there was not enough food to eat. It was decided that Eagle would fly to find the Creator and ask for help. However, a long time passed and Eagle did not return. The other birds and animals became cranky and discussed choosing a new leader. All except Hummingbird who remained loyal and held faith that Eagle would return as he said he would. Eventually, Eagle did return, exhausted and hungry, and everyone but Hummingbird was too ashamed of themselves to greet him. Eventually, everyone came to hear what Eagle had to say, and Eagle told them that the Creator had prepared a new home for them. Hence, the creatures of the land and sky prepared to leave, storing all but the most necessary of supplies in a cave for anyone who arrived to inhabit their land after them. Because Eagle had worked so hard and never given up, despite suffering hunger and exhaustion, the Creator gave him his white crown. Because Hummingbird was so loyal, he too got a reward, a shining ruby of feathers on his chest.

We chose this book as a positive resource to bring into classrooms because of its clear legitimacy as a source of Indigenous storytelling knowledge. The author, Jane Chartrand, is a woman of Métis and Algonquin ancestry from the same community the story comes from. Indeed, she heard this story and many others from her grandmother growing up. The illustrator, Zaawaazit Mkwa Tsun, is an Algonquin man from the same city as the author. Even the publisher, Pemmican Publications Inc. is committed to publishing Indigenous owned and created content, so we can be sure that profits from this book are returning to Métis and Aboriginal communities. Further, this book is purely about Aboriginal cultures and histories, illustrating a thriving society without the presence of European settlers.

Based on our observations, the story of How the Eagle Got His White Head showcases the importance of Indigenous oral tradition. As the grandmother passes on the story to her grandson, it exhibits how Indigenous cultures values knowledge as the greatest gift. Additionally, the grandmother telling the story to her grandson depicts how the grandmother is shown to hold the knowledge and is responsible for ensuring that the knowledge is passed down to the following generations. Values of trust, loyalty, hard work, perseverance and leadership in the Indigenous cultures are displayed throughout the story. The Eagle was willing to work hard, trudged through hunger and exhaustion, and made sacrifices for the sake other creatures. If the Eagle had not shown good leadership skills, he would not have earned the trust of the other beings nor the rewarding of his white crown. A good leader follows through with his or her promises very much like the Eagle did. Moreover, the story focuses on the bond between the sky and land creatures. It is through their work of collaboration that both creatures were able to obtain a new habitat. With that said, it is important that we maintain a positive and collaborative relationship with one another. As individuals, we ought to work together and coexist in harmony in spite of our differences in cultural or social background. Lastly, nearing the end of the story, the eagle and the land creatures left behind resources for anyone who came after them. This interpretation is a profound aspect of the Indigenous communities because they want to leave behind resources for seven generations to come. In that sense, it is important that as generations of the present, we ought to not be greedy but, more so take care of one another and the land we all inhabit.

As Algonquian peoples themselves, author Jane Chartrand and illustrator Zaawaazit Mkwa Tsun, give readers a rich insight into the Algonquin people’s customs, values, and beliefs. The two main characters Heyden and Nokomis are introduced to readers as members of the Algonquin community. It is presumed that their community resides in the areas of Madawaska River in Northern Ontario due to the dwelling of the main characters. As depicted in the story, the oral traditions in Aboriginal cultures hold a great magnitude to the generations below. Elders like Niska share the knowledge that revolves around the history, lessons, and stories that are valuable to the community. Evidently, the oral traditions in Aboriginal cultures foster a strong connection between the past, present, and future of the nation. In stories such as How the Eagle Got His White Head, it becomes a mean of education for the young generation into having virtues such as the eagle and the hummingbird.

Upon reading How the Eagle Got His White Head, the text represented several benefits that could be resourceful and memorable to introducing Aboriginal cultures within classrooms. Readers are encouraged to observe and delve into the experience of an oral tradition, which is at the center of Aboriginal teachings and culturs. The story’s premise is based on a grandmother passing on teachings to her grandson, Heyden. Incorporating this source into our own classrooms would provide an exceptional example of the passing down of values from elders to the next generation. The oral traditions in Aboriginal cultures share stories with significant meaning and teach the next generation about principles that Aboriginal people hold dear. In this case, loyalty, leadership, collaboration, and collective living are at the forefront of the story. The concept of “We” rather than “I” is a large theme in the story to reinforce collectivism and push against the mainstream individualistic attitude. These benefits of the story help readers to appreciate, learn, and experience the oral tradition of Indigenous cultures.

The main challenge we foresee with How the Eagle Got His White Head was the length of text in the story. Using this with elementary school students may become a challenge as the need to gain and retain the attention of young children due to the story’s elongated and intricate words. The lack of attention would cause the messages, teaching, and values in the story to be overseen. Therefore, the children would not be engaged in the story in a meaningful and positive way. However, our group has considered some ways to overcome these obstacles. Firstly, the parts in the story in which the grandmother interrupts the story of the Eagle to speak with her grandson is an opportunity stop and check in with the children. These moments come up multiple times in the story and can provide a moment to re-engage the students by ensuring they are following along and accurately understanding the significance of the characters and themes in the story. In addition, the story would be shown with the pictures to provide a visual for the students to interact with and try to maintain the attention of the children. Through these re-engaging techniques, the major obstacles of the lengthy and wordiness of this story. Overcoming these obstacles and challenges can keep this story as a meaningful piece that children can connect with.

This book would be an ideal resource to use with elementary school children around the ages of kindergarten up to grades 4 or 5. It provides a good introduction to Aboriginal cultures through the means of storytelling which, in itself, is a main educational practice used within indigenous communities to preserve information and teach lessons. The story could be enhanced further through the use of props such as puppets and pictures to bring the story to life. Storybooks in general, are an exciting and engaging way to introduce new topics to younger students. This book, in particular, would provide a good basis for a History unit or First Nations topic. When using this book as an educational resource, students should understand where the story originates. This provides a platform on which to investigate the history and cultures of the Algonquin peoples and this can be used to prompt further discussion about Aboriginal cultures as a whole. From here, the teacher could structure future lessons and discussions around the topic of colonialism.

In addition, its key themes of leadership, perseverance, trust, loyalty, and respect along with the main message that hard work will be rewarded make it a great book to study as a Literacy topic. Character studies, for example, would allow students to compare and contrast the characters’ attributes and qualities, such as that of Hummingbird who remained faithful that Eagle would return. Structured class discussions and activities on these characters can also promote students’ moral development by encouraging them to consider positive attitudes that contribute to healthy and supportive relationships within their community, and indeed within the greater society. The theme of peaceful cohabitation within the story can also be used as a tool for teaching about respect, tolerance, and acceptance in a diverse and multicultural society such as that of Canada.

To summarize, How the Eagle Got His White Head by Jane Chartrand is a traditional Aboriginal tale from the Algonquin community. The story advocates values such as leadership, perseverance, and respect which are all highly valued within Indigenous cultures. Given that the author, illustrator, and publisher are all members of the Algonquin community, this book is a legitimate, unbiased and accurate resource and suitable for classroom practice. Its themes and values are true to the culture in which it is rooted which makes it an ideal resource to introduce young children to Aboriginal heritage and can be used in the teaching of several areas across the curriculum including history and literacy.

References:

Chartrand, J., & Tsun, Z. (2002). How the Eagle Got His White Head / written by Jane Chartrand ; illustrated by Zaawaazit Mkwa Tsun.(Chartrand, Jane, 1945- Birchbark series ; 1), Pemmican Publications Inc.

0 notes

Text

We Were Children: A Critical Analysis

Josephine Chiang, Michelle Carney, Neil Dawe, John Lieu and Bryan Yu Hei Leung

Description and Rationale

We Were Children is a documentary that is directed by Tim Wolochatiuk and written by Jason Shearman, which is about two Indian Residential School survivors’ experiences. The film demonstrates how residential schools attempted to kill native culture by taking children away from their traditional lands and lifeways. Lisa Meeches, one of the executive producers of the film, was inspired to share the story of residential school survivors as her parents and older siblings were sent to similar residential schools. She believed that the history of residential schools should be shared with everyone so history is not repeated and Indigenous people can begin to heal. Learning about residential schools is important as it provides context for the intergenerational harm Indigenous people have sustained. This an important rationale for selecting this resource. The movie focused on the stories of Lyna Hart and Glen Anaquod; and can be rented through National Film Board of Canada. Hearing the hard truth about Indian Residential Schools directly from a survivor personalizes what happened more leading it to be more impactful than many books on this topic. The film not only has touching interviews with Hart and Anaquod but also depicts the rampant physical, sexual, and psychological abuse in the school. Interestingly, not all the nuns and priests treated the children in a bad way, some of them helped the kids. In the movie, for example, a sister took the kids to the dining room during midnight and provided food for them, so they did not have to starve. Overall, this movie gives a complex and personal look into what residential schools were really like.

Roles of Indigenous Knowledge

Lisa Meeches, from the Long Plain First Nation, and co-producer, Kyle Irving, interviewed over seven hundred residential school survivors over a period of seven years. During these interviews, they were inspired to create a film that would educate Canadians on the history of government-run residential schools. Alongside educating settlers, Meeches hoped this film would be inspiring for Indigenous people and give them hope for the future of their culture.

The film, We Were Children recognizes the perspectives of two government-run residential school survivors; Lyna Hart’s experience in the Guy Hill Residential School, located in Manitoba and Glen Anaquod’s experience in the Lebret Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan. In the film Hart, from the Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation, and Anaquod, from the Muscowpetung First Nation, share their personal account of how Indigenous knowledge has been taken away by residential schools in a concerted effort to “kill the Indian in child” (Truth and Reconcilation Commision of Canada, 2015). For example, the movie reenacts how the children were punished severely for speaking their own language and practicing native traditions. Furthermore, during schooling, teachers ridiculed Indigenous culture and called Indigenous children savages. These sentiments show how residential schools were an attempted cultural genocide of Indigenous knowledge and lifeways. The film comes from an Indigenous perspective with Hart and Anaquod demonstrating their resilience. Even during some of the most devastating scenes, such as when assimilation techniques were forced upon them, Hart, Anaquod and other Indigenous children were determined to preserve their native identity. The personal stories give a snapshot of the cultural genocide that occurred on Canadian soil. Seeing this could be a tool in de-colonizing in an educational setting.

Benefits and Challenges

A benefit of this film was that it shone light onto what happened behind closed doors in many residential schools and the effects that still linger within the survivors today. Many individuals in Canada are still unaware of the truth about residential schools so this documentary provided some clarity into the disturbing stories told from two perspectives. The film was made more authentic and touching due to the fact that it is told from the survivors themselves; Hart and Anaquod. It is apparent in the film that, during that period, children experienced hardships when struggling to learn English and French, and getting abused and neglected by the priests and nuns. This resource allows viewers to gain insight into the misunderstood, and largely unknown, history of government-run residential schools in Canada. While providing Canadians with a sense of awareness regarding the history of the residential school system, this film hopes to inspire Indigenous people to continue to be resilient and preserve their culture. Another benefit of this movie was that it showed some positive moments that Hart and Anaquod experienced which made it more real as it illustrates to the audience that not all the staff had malicious intent and that some genuinely cared for the students. This pertains to all institutions as there are good and bad individuals in all aspects of life. Furthermore, this film intends to help Indigenous people and settlers by acknowledging injustices of the past which is one of the first steps toward reconciliation.

There are challenges within this resource such as; a restricted age group and a small sample size. The resource can only be used for older students (fifteen years and older), since it is extremely emotionally draining and deals with mature subject matter. This film could trigger negative emotions and reactions in some students as it relies on emotion as a vehicle for education. It is important that the instructor makes it clear that if a student finds the material too overwhelming, they can choose to leave the classroom. Another challenge of this resource was that the story is told from only two perspectives which is a small sample size, considering the thousands of students who attended residential schools. Every student experienced their own oppressions and hardships while pushing through these years of their lives and the film only displayed that through two individuals. It would be beneficial to hear multiple perspectives from survivors of government-run residential schools.

Future Teaching Application

Due to the mature subject matter present in this film, it is most appropriate for students who are fifteen years or older. Since this is a heavy and emotional film, it is important that it is followed up with the opportunity for reflection and action. This film should be used as a springboard for conversation to discuss how knowledge of the past can help give settler communities an understanding of the needs of Indigenous communities allowing both sides to create trusting relationships along the journey reconciliation.

After watching the film, students will have a few minutes to silently reflect on the film. Then, students will form a sharing circle where they will be given the opportunity to share their initial thoughts as well as how their assumptions about residential schools were challenged or reproduced. Once everyone has had the opportunity to share their thoughts, they will be divided up into four groups. Each group will be assigned to one whiteboard with a question in the centre for them to answer. The first whiteboard will have the question: “Do you feel you had a well-rounded and accurate understanding of residential schools before watching this film? What new insights did you gain?”. The second question will be: “What are some long term effects of residential schools in terms of cultural preservation and history?”. The third question will be: “How has your newfound knowledge impacted your how you will approach reconciliation between Indigenous cultures and settler communities?”. On the fourth board, students will be asked to “write down a personal action or pledge to your pledge to help promote reconciliation between Indigenous and settler communities”. Students will be encouraged to discuss the question in their group and write their answers in point form next to the question. Every five to ten minutes, the groups will rotate until every group has had the opportunity to answer each question. To complete the activity, students will regroup in a sharing circle where they share one take-away from the experience, share their pledge with the class and add any closing remarks. During this time, teachers should encourage students to take part in a self-care activity, such as going for a walk, to decompress and gather their thoughts. Additionally, before the end of class, teachers should provide information for the students to contact a counsellor or an appropriate help line. This will be helpful to the students if any of them feel triggered by the movie due to it’s emotional content.

References:

Cole, Y. (2016, May 8). VIFF 2012: We Were Children depicts residential school stories. Retrieved November 03, 2017, from https://www.straight.com/movies/viff-2012-we-were-children-depicts-residential-school-stories

Maxwell, J. (201, August 26). Documentary on residential schools shoots in Portage. Retrieved November 03, 2017, from http://www.portagedailygraphic.com/2011/08/25/documentary-on-residential-schools-shoots-in-portage

Sison, M. (2012, September 26). Film tells stories of residential school survivors. Retrieved October 28, 2017, from http://www.anglicanjournal.com/articles/film-tells-stories-of-residential-school-survivors-11191

Wolochatiuk, T. (Director). (2012, October 2). We were children = Nous nétions que des enfants [Video file]. Retrieved October 27, 2017, from https://www.nfb.ca/film/we_were_children/

Truth Reconciliation Commission of Canada, & Truth Reconciliation Canada. (2015). Final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Volume one, Summary: Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future. (Second printing]. ed.).

0 notes

Text

The Secret Path

Avery Tiplady, Pawan Parhar, Breanna Croxen, Fardin Gadjyev, Jackson Yung

Clan Name:

Maawanji'idiwag (Come Together). This clan name was chosen from the Ojibwe peoples as it represents Chanie’s descent. Maawanji'idiwag symbolizes the need for everyone to listen to each others stories and work together to help avoid eliminating Indigenous culture.

Introduction to The Secret Path:

Following the tradition of the Nisga’a people, our group has chosen to share “The Secret Path” (a visual album by Gord Downie) for “Our Common Bowl” exercise. “The Secret Path” is a musical and animated adaptation of the unfortunate story of Chanie Wenjak, an Anishinaabe boy who died in an attempt to return back to his home from a residential school near Kenora, Ontario. Before the creation of “The Secret Path”, the original story of Chanie was featured in an early edition of Maclean’s magazine. Ian Adams article displays multiple issues regarding Indigenous culture. The term “Indian” is often used throughout the article, but in a derogatory context. Furthermore, alcoholism is labelled as an “Indian Problem”. Ultimately, the article offers Western Colonial ideals as a solution for Residential Schooling. The narrow minded, isolationist diction throughout the article shows the continued lack of empathy towards Indigenous cultures. In Adams’ article, Chanie’s name was spelt Charlie, which also speaks to an utter disregard for the life and the turmoil he suffered. “The Secret Path” provides a more critical, and respectful narration of Chanie’s life, humanizing him rather than the slight victim blaming that is present in the Maclean’s story that originally introduced the Canadian public to Chanie’s story.When Gord Downie learned about the story of Chanie, and decided to dedicate his art and privilege (as a white man, and lead singer of one of Canada’s most prolific rock bands, The Tragically Hip) to bring awareness to Chanie’s story, he created it with a quote from Murray Sinclair in mind:

“This is not an aboriginal problem. This is a Canadian problem. Because at the same time that aboriginal people were being demeaned in the schools and their culture and language were being taken away from them and they were being told that they were inferior, they were pagans, that they were heathens and savages and that they were unworthy of being respected — that very same message was being given to the non-aboriginal children in the public schools as well…They need to know that history includes them.” (Murray Sinclair, Ottawa Citizen, May 24, 2015)

We preface our blog post by clearly stating that this is not a traditional Anishinaabe story. In part of that fact, our rationale for choosing this resource, in spite of it being created by a non-Indigenous person, was that it does create an interesting opportunity for non-Indigenous educators and students to examine ways in which non-Indigenous individuals have an onus to spread and keep alive stories of hardship and overt and explicit discrimination of people through art, literature, and discussions etc. With correct knowledge and awareness to the benefits and challenges of this resource, our clan believes that this visual aid can be helpful to educators.

The Role of Indigenous Knowledge’s, Content or Perspectives:

Although the mediums of “Secret Path” through graphic novel visuals and rock-esque genre of audio elements, cater to a very mainstream non-Indigenous audience, the project is centralized around the perspectives, content, and knowledge of Indigenous people. Downie’s work aims to educate the public on reconciliation through raising awareness on the reality of Canadian residential schooling for a contemporary non-Indigenous audience through highlighting Chanie’s tragic experience at Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in 1966. In “6. Secret Path”, the sixth track on the album that our clan focused on, the audience is given the third person Indigenous perspective of Chanie walking down a path of train tracks, through freezing temperature and under pouring rain with a light windbreaker, trying to find his way back to his real home, and eventually succumbing to eventual hunger and exposure of the freezing elements, through Jeff Lemire’s (a non-Indigenous Canadian artist and cartoonist) animated graphic novel visual depictions, narrated by Downie’s vocals. Chanie’s perspective provides the audience a glimpse into what he endured in his experiences in these residential schools, and the kind of unfairness that the whole Indigenous culture had to endured. Downie’s reiteration of Chanie’s story also highlight the fact that there were many other victims just like Chanie who suffered from the same, if not worse fates as him, and that this part of our Canadian history should never been forgotten or ignored. In Jeff Lemire’s statement on the “Secret Path” website, he admits, “I never learned about Chanie Wenjack or about any of the tens of thousands of other Indigenous children like him who were part of Canada’s residential school system. This is such a massive part of our country’s history, yet our schools didn’t teach us about it. Why?” (Lemire, 2016). This genuine admission of past ignorance and the present fact that he helped create such a powerful medium of reconciliation as a non-Indigenous person, signifies that cultures can be bridged through dialogue and understanding, and past ignorance can be easily turned into knowledge, if presented the opportunity and inclination to do so. Downie’s work helps disseminate Indigenous knowledge and content towards younger audiences who may not be previously aware of past Indigenous history, through relatable and easier digestible mediums of discourse.

Regarding the genealogy in the transfer of Indigenous knowledge to people and place within “Secret Path”, both Chanie’s sisters, Pearl Wenjack and Daisy Wenjack were active consultants and advisors to Downie’s project in raising awareness and preserving real Canadian history, and they are shown repeatedly throughout the visual album. The knowledge exuded from Downie’s project is passed on to a non-Indigenous audience from all parts of the world, which then returns to the Indigenous Community as a reciprocated sense of understanding. These communities further benefit, because according to the “Secret Path” Website, "Proceeds from the sale of Secret Path will go to The Gord Downie Secret Path Fund for Truth and Reconciliation via The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at The University of Manitoba.” (Downie, 2016), and these funds would be dedicated to preserving the history of residential schools and finding more missing children. Downie also established a separate “Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund” that focuses on cross-cultural education to support healing and recovery. The website of the latter fund is largely designed to promote learning for reconciliation and offers a “learning resources page” which showcases various lesson plans using “secret Path” from various Canadian schools (2016, “Secret Path Learning Resources”). The page also offers a Youtube video that showcases both Pearl and Daisy visiting a school that had students writing letters in response to Downie’s project. At the start of the video, Pearl admits that she was hesitant in introducing “Secret Path” to children, because she first thought the children would not be able to understand the pain in Chanie’s residential school experiences. As the video progresses, the students read their letters to the Wenjack sisters and they are shown to able to understand and relate with the Indigenous knowledge shared through Downie’s work. The video then ends with the children celebrating the diversity of cultures within their communities and being hopeful for the future. This video and learning resource page makes it evident that education and awareness on the reconciliation between two cultures are possible, and different people from different places can establish genuine connections with each other by simply communicating.

Benefits and Challenges:

Throughout the Secret Path, Downie’s words have a sudden respect for space as they stay true to Chanie’s story. In the first song, “The Stranger” Downie resists projecting onto Chanie, as the lyric produces a form of ambiguity and anxiety that remains true to the theoretical feelings of a lost 12-year-old. The benefit of this approach would be the calm introduction of the history and story behind Chanie’s story being suitable to ease into and develop a form of attachment towards the hardships experienced on his journey. Downie’s direct lyricism also reflects to how the Secret Path itself is a story of space, illustrating on the distance between Chanie and his family, and the open spaces between his steps on a seemingly endless stretch train tracks. The visuals that this story portrays within the viewer's imagination, viewer’s typically remember the majority of what they see and hear, and very rarely what they have read, as the level of interaction develops, a stronger connection forms within the viewer. This benefits greatly, in ensuring that these Indigenous stories, are not forgotten, that the experiences of individuals faced through this historic catastrophe are heard. Residential school awareness is essential to the healing process as this is the first step to reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

The sensitivity of the subject, could be a challenge to some viewers, as the message behind the story is rather strong. Viewers who have experienced, or have family members that have endured the rather disturbing treatments within residential schools may struggle with the material. This may result in psychological distress and pain that has not yet been forgiven, causing some to have to relive such a horrid experience mentally. Proper protocols would be necessary to help manage these difficult topics and to prepare viewers for what is about to be presented. The story is a difficult, inspiring and very painful journey for everyone. It may be rather difficult to find a teacher who is willing to teach this resource and subject confidently towards their peers, otherwise the story loses meaning if not presented and discussed openly within a classroom setting.

Educational Perspectives:

One of the advantages of this source is that it could be used in many ways in a classroom environment. For younger students, the audio and visual aspect of the source would be a great way to introduce the histories of the residential school system and Canada’s legacy regarding their treatment of Indigenous peoples. Furthermore, these histories require a lot of difficult reading and so the visual representation that the source provides would perhaps be more suitable for younger students. Although the visual album is approximately two hours long, an educator has the option of showing specific parts of the album, or perhaps viewing the album over a longer period of time. In particular, the introduction and the first song would be used as a lesson with younger students in order to create empathy for Indigenous issues and help them recognize that these issues represent a problem for all of us. The tone of the visual album is great for this, as it provokes a strong emotional reaction upon viewing Chanie’s story. We would show the album to students, have them reflect on the events that happened to Chanie, and discuss how it made the students feel if this happened to them. Due to Chanie’s young age, it would be easier for students to picture themselves in his situation and begin to understand the horrors that so many children like Chanie had to face.

For older students, such as those in high school, the source could be used as a way to introduce students on critically examining resources and the narratives that are presented to them. The Secret Path would be used while examine portions of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on Residential Schools in order to provide an audio and visual aid to readings that may be considered dense by students. Furthermore, this could then be used to launch students into a research project. This research project could take on many different directions. One such direction would be to have students work in groups and either focus on contemporary Indigenous issues and the narrative that is being presented or perhaps critically examining other Canadian narratives. Although, some of these may not perhaps be directly linked to the issue raised by The Secret Path, students would be learning to be critical of the narratives that are presented to them and to do their own research before accepting them. After presenting their findings, students would be asked to reflect on the issues that were raised by other groups and how we can try to create a more inclusive narrative of Canada’s past, present and future. Even though the ways of using this source are primarily reflective in nature, it is important for students to reflect and discuss as the classroom can serve as the basis of a dialogue that could result in a better relationship between all of those who live in Canada.

References Used Throughout:

Adams, Ian. The lonely death of Chanie Wenjack. 22 Oct. 2017, www.macleans.ca/society/the-lonely-death-of-chanie-wenjack/. Accessed 3 Nov. 2017.

Downie, G. (2016). Secret Path Learning Resources. Retrieved from https://www.downiewenjack.ca/learning/secret-path-learning-resources

Downie, G. (2016). Statement By Gordon Downie. Retrieved from http://secretpath.ca/

Gregorie, L. (2016). Gord Downie’s Secret Path giving hope to Inuit trauma survivors. Retrieved from http://www.nunatsiaqonline.ca/stories/article/65674gord_downies_secret_path_giving_hope_to_inuit_trauma_survivors/

Lemire. J. (2016). Statement By Jeff lemire. Retrieved from http://secretpath.ca/

0 notes

Text

Speaking Our Truth: A Journey of Reconciliation by Monique Gray Smith.

Christine Albertson, Robin Goodman, Matthew King-Roskamp, Marisa McGarry, Kimberley Thee

What is the resource and why did we select it?

Speaking Our Truth: A Journey of Reconciliation is a book written by Monique Gray Smith (2017) which encourages readers to join the journey of reconciliation and to explore the true history of Canada. This book can be found as an ebook from Google Books and Amazon, or it can be ordered as a hardcopy from the Speaking Our Truth website (http://orcabook.com/speakingourtruth/index.html). The supplementary Speaking our Truth Teachers’ Resource Guide (Henry, 2017) can be downloaded for free from the Speaking Our Truth website (http://orcabook.com/speakingourtruth/index.html). These additional multimedia resources aid in guiding students through Gray Smith’s book (2017) and allow students to have a broader and more impactful learning experience. We selected this set of resources to highlight on the “Our Common Bowl (Saytk'ilhl Wo'osim') Knowledge Mobilization Blog” because it discusses essential topics for Indigenizing one’s educational practice and is an exemplary Indigenous educational resource that meets the criteria for critically assessing Indigenous resources. In particular, Speaking Our Truth:

• Is written by an Indigenous author who does not claim to speak for all Indigenous Peoples, identifies “with specific Indigenous communities,” and “provide[s] some legitimate or specific reasons for sharing the content” (Parent, 2017, slide 12);

• Avoids “anti-Indian bias” (“How to tell,” n.d.);

• “Acknowledges and honors the source of the story” (“Oyate’s additional criteria”, n.d.);

• Offers a “complex and contemporary” depiction of Indigenous Peoples and Indigenous knowledge (Parent, 2017, slide 19);

• “Reflect[s] cultural knowledge as alive, fluid, complex and applicable in a contemporary context” (Parent, 2017, slide 19);

• Depicts Indigenous Peoples as “members of highly defined and complex societies” (“How to tell,” n.d.); and

• Portrays Indigenous Knowledge as “[growing out] of the past, connected to the present, and taking the people into the future” (“How to tell,” n.d.).