Text

The Little Lop-eared Lady

How does that crazy old lady make a mess like this, day after day? It’s like she runs around the building tossing shit everywhere, giggling about how funny it’ll be when she orders us to clean it up.

I had cleaned the kitchen, the guest room and the hallway. My dress was dirt-black. I’d already smoked three cigarettes and it wasn’t even noon yet. It’s a never ending job keeping up with the crone who lives in this dump, not to mention thankless—how has Ethel put up with this for so long? How has she kept from having a nervous breakdown and stabbing that slavedriver to death?

Beatrix Potter, the loony Lunarian that lords over this little witch’s house. Oh, she acts nice enough—candies peaches for us, made Ethel a nice necklace, has only ever joked about cutting off our feet to make luck charms once or twice—but I see through the facade. That snide, smug, self-satisfied smile. The way she wears her hair in that careless, sloppy bun. The way she holes herself up in her room for days at a time without a word. She’s a self-absorbed, slave driving sponge, leeching off our labor while she lies around and barks orders.

It’s always, ‘You left cigarette butts on the dining table, Matilda,’ or ‘Don’t leave your dirty plate sitting on the veranda after lunch, Matilda,’ or ‘Could you go to the market and fetch some milk since you drank the last of the gallon, Matilda.’ Lazy old bat! Won’t do a damn thing herself! Makes me sick!

“Matilda? Didst thee drop some heavy thing? I heard a banging sound, come from beyond the balcony door,” snaked the muffled, lecherous voice of the Lunarian woman, feigning concern from inside the building.

“I, ah, everything’s fine,” I replied quickly; I had absentmindedly been stomping the ground in my very rightful anger. Thinking fast, I added, “I tripped over one of the flower pots you leave out here. Real dangerous, leavin’ ‘em sitting next to the side ramp. Lucky I caught myself. I could’ve gotten hurt if I fell.”

“Oh, truly? I did hope the ivy might benefit from direct sunlight. Mayhap you are right—do bring them inside, then, wouldst you?”

Gritting my teeth and grumbling, I squatted down to lift one of the oversized plant pots, digging my thumbs into the potted dirt. She grows so many plants here. Fruits and vegetables and all kinds of flowers. I gotta wonder, is it because she’s so disconnected from life and death that she feels a need to watch it all the time, just so she remembers what it is?

Not long after Ethel signed me up for her little lunar coven, I tried asking. Why all these little projects? ‘The fruit of the mind rots eternal,’ she’d pretentiously yarn. Just how old is she, anyway? ‘Old enough to remember, but young enough to forget,’ whatever that meant. If she can’t die, does she really need to eat or sleep? ‘Please just help your sister prepare supper like I asked,’ she ordered, before rudely leaving the room.

Between the ivy leaves scratching my nose, there was a bright light coming from the sidewalk, like someone was holding up a mirror and reflecting the sun. Annoying—as if I didn’t already have enough to put up with, some goddamn hobo was trying to blind me. I put the pot down and raised my fist to yell at them, but whoever it was had already run off.

I set the pot down just inside the door and scanned the room for lurking eyeballs. The moon hag had wandered off somewhere, and I hadn’t seen my sister in a good hour or two—there was always the chance she’d gotten lost in the cupboards somewhere, hunting down every last strand of shed old lady hair.

The balcony entrance led to a mess of a room that Beatrix called ‘the laboratory,’ but the only laboring that ever happened in there was my sorry butt trying to scrape the still-burning embers of her failed science experiments off the walls. Two big tables sat in the middle of the hardwood floor, covered in filthy beakers, dirt and the occasional spot of mold growth. ‘Don’t clean up the dirt,’ she’d tell me. That it’s ‘rare lunar soil.’ How rare can it be if there’s a whole moon covered in it?

I’m not sure what it was about it, but the room seemed to attract plants. Every time I went in there, I’d find another vine growing out of a crack in the wall. One time I found a seed that had started to grow from a single speck of the moon dust that made it onto the floor. It doesn’t concern me much—I just rip them out and toss them.

I leaned into the doorframe and edged my head into the hallway, one ear at a time. Looking toward the library, there was nothing but empty hall and closed doors, lined by that ugly waist-high red wallpaper and those gaudy paintings of Lunarians holding rabbits. They sort of creep me out—are those round little puff-rats how humans really see us? Granted, I dunno what a human sees when I give ‘em the eye, but I always assumed it was something scary. Not whatever that is.

I turned my head to look toward the door, and who did I see but my little goody two-shoes sister. Standing there, with her fluffed-up ears and neatly combed hair, dusting the paintings. So proper. So refined. That tease. That flirt. Standing there, with all the buttons shined up on her green shirt. Oh, I’d seen her, showing off to rabbits passing by the Gallery. She acts like she’s so innocent, but I’m not fooled.

And to think she has the gall to tell me how to take care of myself. So what if I just comb my hair back in the morning? Nobody’s gonna see me anyway. And if I go outside, the wind takes care of the rest.

“Oh, Matilda,” she said, turning her head toward me, those dopey elephant ears of hers flopping around like fish out of water, “did you finish cleaning the guest room? How is the laboratory looking?”

I folded my arms impatiently. Of course! The first time we see each other in who knows how many hours since the slave driver sent us off to till the endless fields and clean her countless cobwebs, and what does she have to say to me? Not ‘good to see you,’ or ‘I’m glad the witch hasn’t made you into rabbit stew.’ No, it’s just the usual lack of trust in my work ethic, as if I’m some freeloader.

Should I not at least expect my own sister to join me in slacking off as a form of consolation? A rabbit rapport that stood tall against the old lady menace? No, that would imply that she and the hag aren’t giggling giddy behind my back, coming up with busy work for me to do. Who put these fingerprints on my imagination?

“Is something the matter? Your eyebrow is all atwitch,” she said, softening her voice to sound as innocent as she could manage, clearly guilt-ridden.

“Yeah, yeah, I took care of it, if you couldn’t tell. My clothes are black,” I pointed out the obvious, gesturing to the dirt darkened dress. “I’ve earned a break, ain’t I?”

“It is nearly tea time, so we can all rest a spell. Could you do me a favor first?” she asked coyly, wearing on her face an insincere smile.

“What’s that?” I impatiently demanded. A favor that would take the better part of the next hour, no doubt.

“I’ve not had a chance to tend the garden. If it’s not too much trouble, could you water the flowers?” she asked, touching the tips of her fingers together, transparently faking innocence. The garden was her job, and I wasn’t about to be suckered into taking on extra work simply because she didn’t want to get dirt on her pretty long ears.

As I was placing my hands on my hips and filling my lungs with the air needed to righteously deny her, however, she reached out and grabbed one of my ears.

“Hey! What are you doing?!” I demanded, careful not to jerk my head and pull my own ear off.

“Please, Mattie? I need time to prepare the tea and scones, so I would dearly appreciate your help,” she said, one weasley lie after another. While she had me distracted and fearing for my poor ear, she snaked the fingers of her free hand to my armpit and began to torture me with tickling.

“Stop! Stop it!” I cried between unwanted giggles. “Okay! Okay! I’ll water your goddamn plants!”

“Thank you,” she said with an evil smile. She loosened her grip on my ear and I slapped her hands away. Curling her finger and placing it on her lips to stifle her wicked cackling, she began toward the kitchen. “It shouldn’t take you but a minute, so come back to the kitchen when you’re finished, if you like.”

I scoffed. As if. The last thing I wanted was to play pastry maid; as soon as I was done watering those plants, I’d be off on another date with Mr. Marlboro. I begrudgingly made for the double doors at the entrance, quietly praying that a rainstorm had kicked up while I’d been inside.

Sadly this was one of the few days the big guy in the sky decided our little home sweet home didn’t need a thorough cleansing via torrents of rain and a sprinkling of lightning. The sunlight poked through the trees as if to greet me—what a nuisance. Eventually I convinced myself to trudge down into the mud hole we call a garden and pick up the watering can.

This dress, this field of plants and vegetables, this pail—I felt downright amish. All I needed was a well you pump by hand and I’d be right back in the 1800s. As backwards as things often were in the hermit’s company, though, we at least had running water and electricity.

I dropped the watering can onto the ground, dragged the hose toward me bit by bit, coiled the length of it next to me, and plopped the end into the can. If I wasn’t dirty before, I was then, my hands slimy with grime. I turned the nozzle, grumbling.

“Matilda, what would your mother say if she saw you covered in mud like that?”

A voice called from behind my back. I swung around to see the trees, like skyscrapers, reaching into the sun above me. A figure stood there among the forest, his shoes sunk into an inch of pine needles and shrubs. The hatch that lead into the warren was open next to him. The glare of the sunlight was blinding, but I could see his messy curls of hair, and I could feel his tired stare.

Daddy…?

The man turned to leave, blocking the sun’s blinding glare. Past the gate, standing on the crumbling sidewalk, I could see his shining spikes of golden hair tucked beneath a flat cap and his filthy-looking black leather jacket. The telltale look of a runaway coward who had a lot of nerve to show his face here.

Of course it wasn’t dad. It will never be dad.

“Hey!” I shouted at the golden hobo-hare as he ambled away. “Where do you think—”

He took the brim of his hat between his finger and thumb and covered his eyes, taking off down the street at a sudden urgent pace. I grit my teeth and tossed the still-flowing hose into the dirt. Grabbing my dress and hiking it up to my knees, I darted after the jerk. Once I reached the fence, I squatted down to gather my strength, my legs like coiled springs, and bound over the gate in one hop.

The hem of my dress caught on the gate and I nearly tumbled to the concrete. I managed to jerk it free with only a small rip, but by the time I looked up, there was no trace of that man’s greasy blonde hair.

Any other day I probably would have given up right then. My dress was covered in filth, there was mud in my shoes, and I could hear flowing water as I’d forgotten to turn the hose off—but god damn it, if I wasn’t determined to find that man and make him answer. Who the hell does he think he is, slinking around my home, spying on me and my sister?

So I took off in the direction he’d snuck away, flicking my eyes back and forth like a crazed cat hunting for a slippery little mouse. What hole did you disappear into, Gally? Down the abandoned alleyway next to the Gallery, where the dregs gather because they can smell the moon peaches? Perhaps hiding in the bushes, waiting for me to pass by so you can sneak away like a cornered rat? My teeth were clenched tight as I hunted for him, my fists bound so hard my knuckles were turning white.

Without realizing it, I’d pursued him down to the train tracks at the end of the block. Yellow cat’s eyes looked curiously down at me from the black, empty windowsills of the abandoned houses nearby, and if I was in a mood to care, I might have been concerned about the ever-present possibility of some lecher lurking in the shadows looking for his next taste of hare’s blood.

“Galahad! You coward! Show your face right now, you slimy, slackjawed vermin!” I shouted into the rustling trees. “You crusty old rat! You’ve got some nerve coming to my home, an—”

A hand slipped over my mouth, large enough to grab me by the jaw. It was connected to an arm covered by filthy leather, and above my head there was the blonde beard of the damned codger I’d been shouting at. His palm smelled like tobacco. He put a finger to his mouth and shushed me, which only encouraged me to flail my arms in anger and shout into his hand.

“Be quiet, goddamnit,” he said in a hushed, wary tone. He looked this way and that, probably looking for the shadow people that only appeared in his dried out, elderly mind. Once he was convinced that nobody was there, because of course there wasn’t, he let go of my mouth, spun me around and grabbed my shoulders. “Quit followin’ me. Ain’t safe out here.”

His voice rumbled in that gravelly way it always did, like there was a rock slide in my ears. Every time I heard him talk I could only wonder how he wasn’t dying of throat cancer. Still, as annoying as I found it in that moment, there was something comfortingly familiar about it.

“As if you give a damn about my safety,” I said, hot vapor escaping my nose. I turned my head away and huffed at him; he didn’t deserve the dignity of being looked in the eyes.

He sighed, mumbling grunts as if he had any right to be dissatisfied with me. He let go of my shoulders and gave me a long, hard stare, stuffing his hands into his coat pockets. I scrunched up my nose at him to return the displeased sentiment. An uncomfortable silence settled in—which he broke with a fit of snickering.

“What’s so funny?” I demanded, stamping my foot impatiently.

“Oh, it’s jus’,” he pointed at my dirty dress. “They really got you scrubbin’ the floors and pickin’ weeds? I ‘member a time when you used to scream and shout when Charley so much as made you pick up yer toys and—”

“Shut up! What do you know? I did chores! I cleaned! You just didn’t stick around long enough to see!” I turned my back to him and folded my arms, my face red-hot. I thought about leaving him standing there right then, but I stood my ground.

“Alright, alright. Listen, let’s go somewheres nobody can hear us, okay? You can yell at me all ya like, then,” he said, sounding immediately tired of his own concession.

Turning my head enough only to give him a sidelong glance, I nodded shortly. He began to nonchalantly walk away down the train tracks, and would have left me standing there if I hadn’t hurried to follow. I again had a strong inclination to leave the senile old man to his wiles and just go home, but I was determined to give him a piece of my mind.

As we walked the tracks, the guy popped up his collar, lowered the brim of his hat and tried to sink low into his coat like a turtle hiding in its shell. It was ridiculous; as if any of the vagrants hunting the alleys for cans to turn in were going to recognize him.

“What are you doing?” I asked, raising an eyebrow. I couldn’t help but laugh. “You look like an asshole.”

“Anybody was to see you with me, it’d complicate things,” he grumbled.

“Don’t wanna be seen with a dangerous Separatist criminal like me, huh?” I said before jabbing him in the rib with my elbow. He grunted and shook his head.

“No. If they was to see you, any of Jack’s flunkeys might think they could use you to get to me,” he said, an obvious lie.

Jack is dead, why would the Separatist rabbits still be looking for Galahad? Petty revenge? They were a group of displaced hares looking for a better life; they wouldn’t be interested in ‘getting back’ at Galahad for ridding them of a lying, lecherous, greedy man who promised more than he could deliver. At least, I would hope they wouldn’t—Jack broke up families, destroyed homes and tortured people, and for what? To end up right back where we started?

I found myself staring at the blonde man hiding under his flat cap. A matter of weeks ago, I wanted to see him strung up on a cross, literally bled dry to lead me to a fool’s paradise. Where did that anger go? There on the tracks, I saw his blonde bristles of beard, and for some reason I could not summon that anger. It was simply gone, and all I could offer in its place was annoyance.

“If you say so. Don’t they have better things to do than chase after a scraggly old man like you?” I asked, smirking.

He gave a raspy chuckle. “I sure hope so.”

As the track smoothed out onto road, the old rabbit lead me onto the street, and stopped before an inconspicuous looking little square house, its baby blue paint chipping and its roof looking like it might fall in any day now. Its yard was untended and overgrown, and the windows were shaded and dark. From where I stood, it looked like a drug den.

Galahad climbed the two step stoop made of cinder block before the door, and dug into his pant pocket to pull out a key. He stuck it into the door, and with some jimmying and banging, managed to get it open. I hopped up behind him to follow inside, but he placed his hand on my head as if telling me to wait, and poked his face into the crack of the door.

He stood there for a long while, taking in shallow breaths through his nose and silently scanning the room with his eyes. Finally, he was satisfied, and swung the door wide. He stepped quickly inside, ushered me in, and shut the door just as fast behind me.

I flicked the lightswitch next to the door and was greeted by a dimly flickering lightbulb above my head that provided just enough light to make out a vague amber outline of what lurked in the room. I saw the ceiling, pockmarked with rain damage; I saw cracked walls bleeding plaster onto the barren hardwood floor; I saw empty tables in the adjacent ‘kitchen’ that lacked a refrigerator. In fact, the tiny house distinctly lacked any sort of appliances whatsoever. Save for a couple of lawn chairs, piles of ashes here and there, discarded packs of cigarettes, and a bundled up sleeping bag in the corner, the place was empty.

“You, uh… live here?” I asked, looking at him incredulously.

“No,” he said, pulling a cigarette pack from his coat pocket. “This is an unoccupied house. I’d say it was abandoned, but there’s a guy who owns it. He jus’ ain’t done nothin’ with it in, oh, ten or so years, as far as I gather.”

“So you’re squatting.”

“I like to think of it as recyclin’. I’m usin’ somethin’ that’s been thrown away. Lotta houses in this town just sit empty for years an’ rot, while poor folk who could be livin’ in ‘em are sittin’ in the rain right outside. The guy who owns it ain’t usin’ it, so what am I hurtin’, sleepin’ on the floor every now and again?” he puffed excuses through the cigarette held in his lips as he leaned against the wall. He looked so unconcerned, the owner could probably have burst through the door at that very moment and he wouldn’t so much as blink.

“Then how’d you get the key? You steal it?”

“The owner was in here checkin’ fer squatters a while back. I convinced him to give it to me, an’ as far as he knows ain’t nobody been here,” he explained, shrugging.

“I thought you told us to never use our eyes unless we absolutely had to,” I interjected, attacking a hole in his complacency. “You hypocrite. Not so holy and righteous after all, are ya?”

“You an’ yer friends didn’t leave me much choice. Thanks to what you put the kid through, my old hidin’ place ain’t so secret anymore. I go back there and I’m liable to catch a bullet in my teeth,” he rumbled, lighting his cig. “An’ that’d be inconvenient.”

I nodded absentmindedly; the image of the old coot running from one hidey hole to another, pursued by drug addicts and the people he’d burned sprang into my mind. I put my hand over my mouth to hide a spiteful smirk.

When I was done silently laughing at his misfortune, however, I recalled the annoying reason I was standing in his crummy hovel in the first place. I put a hand on my hip and pointed an accusing finger at him, poised to give him the talking-to that he’d earned from his years of negligence and cowardice, but more importantly, for how he’d irritated me on that particular day by darkening my doorway.

“And so you thought it’d be a good idea to show up at my house, skulking around like a goddamn thief? These people who’re supposedly looking for you, they sure didn’t stop you from showing your prickly prick face did they? What if they showed up there, looking for you?” I stabbed my pointed finger forward through the air until it stopped on his chest, where I harshly poked his leather jacket several times.

He shut his eyes and sighed, likely taking a moment to come up with an excuse. In his position, leaned up against the wall with my finger jammed squarely into his ribs, it was going to need to be a good one.

“Hadn’t seen you or your sister in a fair bit, not since everythin’ went down. Wanted to make sure you was alright,” he mumbled and wouldn’t look at me, instead staring at the blinds in the window.

For a moment I wasn’t sure what to say. I withdrew my finger, turned around and looked toward the filthy tiles of the kitchen floor. There was a heavy, uncomfortable air in the room that was making my cheeks hot, so I changed the subject.

“Why’re you staying in a shitty place like this? Why not leave town, find somewhere better?” I asked, subtly concealing my desire for him to go away with an innocent-sounding question.

I could feel his yellow eyes pressing against the back of my head.

“I can’t. Not before I find ‘im.”

“Him?” I questioned, spinning around. “You mean… Jack?”

“I know what yer thinkin’—you saw the kid bludgeon him to death with yer own eyes, practically painted the damn floor with his blood. Ain’t no way he survived that, right?” He took a long puff, inhaled, and exhaled the smoke through his nose. “Iffin’ that was the case, his body shoulda turned up somewhere.”

“What? What are you talking about—didn’t the police take it?”

“Yeah, ‘bout that. I did some askin’ around, poked my nose here an’ there. Accordin’ to them, there weren’t no murders in the church that day. Just some injured folk who can’t recall what happened. But you know how it is in this town; they jus’ arrest everyone half-suspicious lookin’ and call it case closed, none too concerned ‘bout who did what,” he explained, and shook his head, disgusted.

“I’m sure the Separatist rabbits took him. They probably just chucked his body in the river,” I said, shrugging impassively. “He may have been a lying scumbag but I’m sure they didn’t just leave him there for the humans to find.”

“Ain’t that simple. If he’s gone, the Separatists should be scattered, disorganized. As it is, I’ve had three run-ins with ‘em just this week, an’ not fer a friendly chat over coffee ‘n donuts,” he said, his eyes tensing on me. “But it seems things’ve changed. They ain’t interested in my blood, not no more. No, what they want is ‘make the traitors pay.’”

I felt a chill run down my spine. That intense stare he was giving me, the low rumble of his words. This was no joke, he wasn’t trying to play some kind of mean-spirited prank. I could be in danger, just by having followed him.

Well that’s just fucking great. ‘Traitors’ like me.

“This gettin’ through to ya? Ya ain’t safe bein’ seen around me,” he said through a sheen of smoke. “Best thing for ya is to stay with that moon crone. Sure, she may be a headcase what’s got you cleanin’ her floors with a toothbrush, but no rabbit ‘round these parts’ll give ya trouble so long as you’re with her.”

“You kidding? That crazy old bag is a danger to herself and others. I’d prolly be safer on the streets,” I sighed, folding my arms.

I could either fear for my life running from the remnants of the Separatists, constantly looking over my shoulder, or I could fear for my life living as a lunatic’s girl in waiting, constantly wondering if her next crazy experiment will turn our house into a crater. You just can’t win in this world.

There was a light tap on the window, followed by several more. I felt a draft blow in from the door—a sudden rainshower. I nearly kicked the door in frustration; if I’d just waited a half hour I would never have needed to water the plants in the first goddamn place.

“Aw hell. That figures,” Galahad grumbled from the wall. He gave me a wry smile, and said, “Least we ain’t in it, huh?”

“Yeah, now I’m just stuck in here with you ‘till I decide I’m ready to get drenched,” I muttered.

“Y’know, I been thinkin’, since yer here, girl—” he rudely began, but I cut him off.

“I have a name.”

Chuckling, he cleared his throat and began again. “A’course, Matilda.” He pushed himself up from the wall and straightened his back. “Since yer here, maybe you could help elucidate somethin’ for me.” He came nearer, his presence akin to a cloud of cigarette smoke. “You were there when they took the emissary's blood, weren’tcha? You was with Jack’s Separatists from the beginnin’.”

“I was,” I confirmed, looking him unapologetically in the eye.

“You watched ‘em as they took a confused, helpless girl who didn’t know up from down and cut her open in the street. You watched as they left her to die.”

“I did.”

We were staring daggers into one another. I was afraid to blink, as it might have made him miss even a moment of my spiteful look.

“Yet they never did kill ‘er, and she was lucky enough for some bumbling kid to come along an’ patch her up. Jack, for all his blusterin’, couldn’t even kill one little moon girl. Ain’t like he didn’t have ample opportunity to finish her off later, either. Why’s that, ya think?” He stood over me, saying whatever he wanted, so satisfied with himself. I wanted to slap him, but I just looked at him and said nothing.

“I don’t think he had a sudden change ‘a heart, or that he didn’t have the stomach for it. No, I think somebody stopped him,” he sneered.

I felt my ears perk, my anxious nerves like needles pricking under the skin. I was an inch from reaching up and tearing his hair out.

“I think somebody stuck their neck out for our little moonie and begged him not to hurt ‘er. Ain’t that right?”

“SHUT UP!”

The words strangled me as they left my throat. My hands were balled into fists around his leather jacket, and I felt my bottom lip rupture as my two big teeth dug into it. Under the thundering beat of my heart, I stopped myself where I was, grabbing him, and repeated myself.

“Shut. Up.”

“... Sorry,” he mumbled. “I didn’t mean… It’s just, because of you, she’s still…”

I let go of him and turned around, staring at the filthy floor. I sighed a heavy sigh; it’s true—when Jack cut open the lunar emissary, he was going to slit her throat to get the blood for that poison. I begged him not to. She’s a moonie, those holier-than-thou cretins who look down their noses at us filthy half-breeds on the Earth. I should have hated her—but she looked just like us, and she was alone and scared, couldn’t even speak our language. It wasn’t right. So he cut her down the middle instead, where she surely would have bled to death if it wasn’t for some bumbling moron in the night who happened to find her.

So much for me being some bucktoothed paragon of mercy like everyone keeps trying to imply. All my begging didn’t amount to very much.

“Just, maybe you could help me out here, that’s all I’m sayin’. If I’m gonna find ‘im, I need to understand ‘im.” Galahad’s scratchy drawl had a tint of desperation in it. The sound of him at a loss, asking for something only I could give—it was pretty nice, honestly. “What kinda leader was he? What’d he have ya do?”

“You wanna know what happened? I’ll tell you,” I stated, taking a deep breath. “But this is just so there’s no confusion.”

“Right,” he grunted, stuffing his hands back in his pockets and returning to the crumbling wall.

“After we took the emissary's blood... the next step was to wait for you to come out of hiding,” I explained, turning my head to glance at him. “With the emissary’s blood to make skoab, Jack thought you’d have no choice but to show yourself. And sure enough, you did.”

Galahad frowned and glanced down at his feet glumly, but nodded for me to continue.

“There was this old abandoned house we were staying in to make the drug. I’m sure you know how that is,” I said, giving him a knowing look.

Galahad stared back wryly. “You sure it was abandoned? Ya didn’t jus’ eyeball somebody outta their home, didja?”

“I’m sure. The place was a dump. Whoever lived there ditched it a long time ago; the driveway was full of dead cars and rusted old junk. From the way the place smelled I’d be surprised if there wasn’t a dead body in one of the rooms and we just never found it.”

“Some ‘Heaven on Earth,’” he scoffed, shifting his moustache in distaste. “Lot better than livin’ in a place you could call yer own, with people who care about ya.”

“Anyway,” I continued, ignoring him, “it was only a few of us. Me, Jack, Barnaby from the warren, some other people I didn’t know. Jack didn’t want to attract attention, so he only ever had a few of us together at once.”

Except for that time he gathered us all together to terrorize the emissary just because she survived, I remembered. We pushed her into the mud and spat on her.

“He was a real jerkass. Always his way or the highway. Always had some big plan, would never give us all the details. Just ‘trust me Mattie,’ and ‘you know I’m right Mattie,’ and ‘I understand humans better than you, Mattie,’ like the fact that he lived out in the city made him better than us somehow. He even had the gall to make a pass at me,” I said. As my lips shut I put my fingers over them, realizing I’d said too much.

“Did he now?” Galahad questioned, raising an eyebrow.

“Yeah, but I turned him down. He stunk like blood and rotten eggs all the time,” I said matter of factly, brushing it aside. The scruffy old man just grunted in response.

That was a lie, of course. Jack’s ‘pass’ at me was far from an amiable fliration. He deliberately tried to get me alone—I know it was half the reason we were in that abandoned shack in the first place. I still remember the lecherous way he looked at me, the way his clothes stunk like death when he came near me. If Barnaby wasn’t there with us, I don’t know what he might have tried. The thought of it frightened me, but I wasn’t about to tell that to ol’ Gally.

“He had me contacting every drug dealer we could find, trying to get ahold of a sample of your skoab that wasn’t already smeared onto somebody’s face. Then, I heard about some crackpot named Markus Flick. Think you might know him. We arranged a deal with him, and he sent a scraggly looking homeless kid up to give us the goods.” I turned to face Galahad, my arms held playfully behind my back. I was sure I was getting under his skin.

“Mm,” is all he said in return, listening with his eyes shut.

“He gave me a bag with a little jar in it, and he demanded I pay him. And then d’ya know what I did?”

“What’s that?” he asked, sighing.

“I looked him in the eye, and I told him to leave and never come back,” I stated simply, shrugging. “And you know what? He was so scared he fell on his ass, and took off running! Oh, if you coulda seen the look on his face. He was terrified!”

I couldn’t help but giggle. It really was hilarious, watching that guy’s face turn white and open his mouth to silently scream. I don’t really know what it is he saw, but from everything I know about how humans react to the ‘red eyes’ rabbits have, it must’ve been pretty terrible. Then again, he seemed alright when I saw him again later—so no harm, no foul, right?

“So that’s what happened,” Galahad said, exhaling smoke and running his hand down his face. “Goddamnit, you coulda got him killed. After ya did that, next thing he knew he was on the other side ‘a town. Was almost at the damn lake afore he came to his senses. Ya can’t just use yer eyes on folk willy nilly, this is the sorta shit that happens.”

“Hey, don’t gimme that! God knows how many people have been outta their minds for who knows how long, thanks to your little poison ointment! You got a lotta nerve to lecture me,” I shouted back.

I wouldn’t let him stand there and preach to me when the only reason we had access to this leaking hole of a house was his use of his eyes. He just sighed, however, and gave me a defeated look.

“I don’t wanna hear it. I know what I done,” he glumly muttered. “I just... dunno how it all ended up this way. Iffin’ I thought I could jus’ let him go, I’d forget about Jack. I’d go away somewhere that I couldn’t cause any more trouble. I fucked things up too much already.”

“Yeah you have! You made a real big mess of everything! Why’d you have to leave in the first place? If you just stayed in the warren, then Jack wouldn’t have convinced us to do all this stupid shit! Then, dad wouldn’t be…”

We stood there, staring at one another. There was a pained look in his eye, like he knew everything I was saying was true, but there was nothing to be done about it now. I knew that as well as anybody, but it wouldn’t stop me from resenting him. Finally, he broke the silence.

“The rain’s stopped.”

The air around the house was still, and the incessant dripping from the leaky ceiling onto the carpet had slowed. I looked toward the door, but I wasn’t quite ready to leave yet.

“After we got the skoab from you… Jack changed,” I said, looking down at my fingers. “I almost never saw him. He locked himself in a room making more and more of it for over a day. And then he was always gone, spreading it around the town. He had me doing it, too, disguising myself as all these different people. He had me put it in old peoples’ food, for Chrissake.

“I saw what it did to people. At the time, he’d convinced me that it was justified. That we had to, because the humans had taken the world all for themselves, and this was the only way to take it back. But…”

“I know. It sounded right. You were tryin’ to do what you thought you had to,” he said quietly. The room fell silent again, until finally he spoke again. “Every night, I find myself thinkin’—wish I could go back homeward. Make things right again. But what’s done is done, there ain’t no goin’ back. What’s left to do is make right of what we got now.

“You oughta leave ‘fore the rain starts up again,” he said, his voice a low rumble.

I nodded and made for the door. With the knob turned halfway, I paused, and turned to look at him again. He removed his hat and wiggled his little ears at me, smiling.

“... I am glad you came back for us. I really am,” I forced the words out as quickly as I could, and slipped through the door.

☆☽☆

With the rabbit girl hopping back home, the gold-haired rabbit stood there a while, staring at the door. For a time, his mind was empty, unable to conjure the thoughts to go along with what he’d just done. Then, his muscles were spurred to movement again. He rose his hands to his head and buried them in his hair, sliding on his back down the wall until he hit the floor.

Liar.

It was only a little white lie, but it was a lie all the same. So much time he had spent surrounding himself with lies. Lies to protect others, lies to protect himself. The faces humans had known him by, lies. The names he’d been called by humans and hares alike—lies.

He was not some gallant, righteous figure whose story rested in exalted tomes of legend. He was not a man who had dedicated to himself to the preservation of his people and culture, nor did he champion the cause of leading those who had been exiled to a new home where they would be welcomed by those like them.

He was just a liar.

From the corner of his eye, the darkness lurking in the lightless spots in the empty kitchen began to bloom and grow. A malignant cloud of shadow, spreading its way over the filthy tiles and spilling onto the carpet. From the black hole, a thin figure sporting a green jacket and long dress emerged. The hare’s thick, blonde eyebrows tightened in anger.

“Whaddya want, witch?” his voice quaked, shaking in the dark.

“What a fine how-do-you-do. Hast thee been afflicted by a malady of rudeness to accompany thy brooding?” the figure in the dark said, its voice flighty and feminine. “I am come merely to see to the wellbeing of my servant, whom you so uncouthly snuck away.”

“You were listenin’ in, were ya? Stickin’ yer nose where it don’t belong again?”

“Oh, but how could I not? ‘Twas such a heated discussion, the atmosphere betwixt the two of you so intense. For a moment, I should not have been surprised if you took her in your great hairy arms and—”

“Shut it,” the hare interrupted.

“Come now, Galahad. How was I to guess that amid thy scruffy exterior, there exist still such a vulnerable creature? ‘I wish it were different. I wish to go home. Oh, little Matilda, the sight of you doth stir the troubled waters of mine heart!’”

The woman threw her head back in laughter, the green ribbon tied around her neck bouncing up and down as she cackled. When she was finished, she pressed the tips of her fingers to her chest as and steadied her breathing, as if relishing each merry breath.

The rabbit sitting on the floor rose slowly to his feet and slipped his flat cap over his stubby ears, adjusting the brim to rest over his brow. He looked sternly into the hermit’s eyes, internally debating whether he need explain anything to her at all. Finally, he let out an indecisive grumble.

“She’s the daughter of a good friend. A’course I care for her,” he stated gruffly.

“Ah, but I tug at your feeble heartstrings merely for a merry jest. Feel howsoever you like, it maketh no difference to me. The girl is mine, and with me she shall stay. The more pertinent matter is that of the falsehoods you hath filled her head with,” Beatrix mused. She pointed a white-gloved finger at the rabbit in the corner, her eyes bright. “Thou wish not to return home to her warren. Thou pine not for a time whereupon you were that girl’s guardian and teacher.”

The hare said nothing, merely reached into his pockets for another cigarette. The Lunarian went on pointing, filling the tiny house with her bombastic claims.

“You are wont to let her believe that, as is convenient, but truly, truly! Truly you wish to put all of this behind you. Long you stare into Luna at night, wishing only to heed her call. To shed your false earthly moniker, and once again be known as the golden sunlight hare! Am I wrong, Heart of the Sunrise?”

Galahad took a long puff from his cigarette, answering Beatrix’s claim with an exhausted stare. For even if everything she said was true, that dream had long gone from the hare’s mind. He looked toward the floor and shook his head in defeat.

“Is that all? I didst hope you at least would have the backbone to fly into a rage and throw me from your…” Beatrix paused to run her gloved finger down the wall, coming away with a small pile of dust, “home. Seems only common courtesy.”

“Feel free to show yerself out,” Galahad grunted, staring her down.

“As you wish,” Beatrix said firmly, holding her nose in the air. She began back toward the darkness she’d emerged, but as she crept away, she flit her gaze back to the hare and quickly added, “but what if I held what you seek? What if I knew thy way back home?”

Galahad glared at her. “What’re you talkin’ about?”

“‘Tis true. Knowest I the currents, the stretch of stars that yet lead to Heaven above. Knowest I how to return thee, the prodigal sun, to his long-lost home,” Beatrix declared, each word more boastful than the last. “Doth thee not wish to go home? Be it not all you have ever wanted since you fell upon this muddy, miserable Earth, gold knight?”

“Get out,” the rabbit rumbled, his teeth grinding into the cigarette butt between his lips.

“Thou need only ask, Galahad. Climb aboard my starship, let us sail for the skies.”

“GET OUT!” Galahad thundered. He stomped in anger, the floorboard cracking under the force.

“I shall be waiting. Come, and we shall sail away,” the Lunarian calmly offered, her voice as quiet and wispy as the wind slipping under the door.

The shadows in the kitchen swelled, reaching from the corners to claim the Lunarian woman. They crawled over her form, swallowing her little by little until she was no more, and the blonde rabbit again stood alone on the damp, rotting carpet beneath him.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Umbral Forest

The soft thrum of spinning fans came quietly from the corner, made audible against the void of silence that enveloped the room. A black, monolithic machine was the only living presence here, its glowing veins of color the only light. Pulsing blues and quaking greens streaked across the floor and over my face, outlining the shape of the girl sitting on the stool before the machine.

My weary eyes were dusted with sleepless exhaustion; I was nothing you’d call ‘living,’ and the girl sitting in the stool nearby was fast asleep—or something like it. Her shoulders rose and fell slowly as she took silent breaths, and the white faux fur of her jacket’s cuff rested on the body of the console, there with her pale hand. Long lashes covered her fast shut eyes, her lids twitching restlessly—and the long, white rabbit ears emerging from her hair stood half-mast in alert. I thought that maybe it was her long strands of hair tickling her nose and nearly stirring her from sleep, as it often did, but this was no ordinary ‘sleep’ she was consumed by.

Though she sat there in the fraying stool, her mind was somewhere else. The humming machine, with its pulsating streaks of light, had whisked her someplace far away. As she murmured and stirred in the chair, her brows furling anxiously, worry churned in my stomach. Typically when she sat at the machine and slept, she was so peaceful, so serene, but as I looked on her body was tense, restless.

The strobing lights swept over the filthy carpet, its edges rotting and giving way to broken floorboards and lightless pits. It climbed the walls and ceiling, pockmarked with chipping paint and rain damage. I watched the light bend from one corner of the room to the other, saw it peel back the cobwebs and reveal the crumbling ruin—but as it receded, the walls were again white with paint and the floors closed themselves up. I blunk and rubbed my eyes, felt them sting red.

The chair beneath me groaned as I rose to my feet, its elderly planks creaking at any movement. I began toward the girl in the chair, my steps blind and uneven, with the weight of my exhaustion threatening to drag me to the floor. She inhaled sharply and I froze; she calmed and exhaled a long, sleepy gust through her nose, and my nerves eased.

When she was consumed by that machine, no force on Heaven or Earth could move her, the sleep she took like death. Yet now her ears darted to and fro as I came closer, and her breathing would become quick and uneasy if I made any noise. Her body had become as stiff as a board as I stood behind her, barely breathing.

I reached a trembling hand out to touch her, each shaking inch more unsure than the last, and placed a single index finger on her shoulder.

Her head snapped robotically toward me, her shut lids trembling and twitching as if attempting to gaze blindly through her eyelids. I began to withdraw my hand, but she reached up and caught me, long pale fingers squeezing my wrist in a painful vice. Her eyes shot open to reveal two gaping red voids, an agonizing crimson light that bore into my head. They stared into me, deep and emotionless, and her inescapable grip dragged me closer, slamming my hand onto the face of the black machine.

The room fell away, piece by piece. Crumbling bits of wood and plaster disintegrated all around me; the walls and floor slid away into the abyss, leaving only blackness in their wake. I felt a weightlessness come over me, as if I’d left my body far behind. My mind was sinking, being pulled into the clutches of the machine, but there was another grip on me, tugging at my arm.

The girl’s wide eyes had faded into an inky black, her brows furled with fright around the sightless voids. She mouthed some desperate plea with trembling lips again and again, and though I could not make it out, I knew what she was saying.

Help me. Help me. Help me.

I fell to my hands and knees, announced to the wet space around me with a plop. My limbs sunk into the thick mud below and I felt twigs snap under my fingers. I choked on the moist air as I pushed myself up to stand on my knees, gasping and wheezing, my head awash with cold sweat.

A thicket of gray trees, enshrouded by dark mist, lay all around me. The gnarled wood reached up toward the blackened sky, the dead branches like twisting fingers grasping for daylight. I could see no end to them; the trees stretched on to the edge of my sight in every direction, the light disappearing in the distance as if the horizon fell away into nothingness.

A drop of something wet smacked the top of my head, sending a freezing chill down my spine. Bits of black were falling in drops from the tips of trees all around me, oozing from cracks in the branches. Looking down at my hands, my legs, they were covered in slimy black ink. Struggling to my feet, I slid in the mud and gunk, nearly falling back in the muck, but I managed to straighten my legs and right myself. My muscles felt like rubber, but I took trudging steps forward, carving a path through the slime.

Squish, squish, squish. I could hear soft whimpering, panicked little squeaks, the sound of a tiny thing struggling in the mud. As I rounded a dead tree, I spotted a small, fuzzy white creature jerking and pulling, its hind leg half-swallowed by muck. Its bright violet eyes fell on me, and it squirmed with terrified fervor as I came near, its frightened squeaks echoing through the wood.

“I ran away! I ran away and she knows! She, she will find me! Cannot hide, cannot hide!”

Amid the aching drone in my head, the squeaks came across as words I could understand. The fuzzy creature, with its long, silvery-white ears that stood up straight in alarm, was crying out in panic. A rabbit, the thought formed in head numbly. It’s a rabbit.

Calmly I knelt down in the mire, sinking my fingers into the grime. I felt a desperately kicking leg, caught under a jagged root, and I gently plucked it loose. As soon as the rabbit realized it was free, it made for cover into the trees, leaving a trail of little holes in the black mud.

I spied its white ears poking from behind a gray trunk, just at the edge of my sight. Its violet eyes were as tiny lights in the dark, and they shone on me with quivering uncertainty.

“She will find you! She will find you! Run, run!” it warned me in shrill squeaks. Its ears twitched and waved to and fro, startled by something, and it hopped away as fast as it could manage into the dark.

Howling wind swept the hair from my face, the inky liquid mixing with freezing sweat. My knees shook weakly as I rose to stand, threatening to give way. Determined, I put one uneasy foot in front of the other and followed the white rabbit’s trail of tiny prints, my heavy footsteps filling the dead wood with echoing splashes.

I trudged through the mud and slime for what felt like hours, my legs aching behind the weight of each step. Miles of dead trees behind me, and miles of dead trees ahead until the edge of my sight, where they were swallowed up by the black. No matter how far I walked, there were still more trees—but the trees were changing, becoming more twisted, their long branches sporting bulging pustules that oozed red pitch. They bent and contorted the branch, the unnatural growth covered by layer and layer of dead bark, like rotting flesh. Looking at them made my skin crawl; something about these trees was very wrong.

A branch above my head hung low, as if weighed down by its grotesque red pustule. It twitched and moved ever so slightly, as if it might burst at any moment. Against my better judgement, I grabbed the lowest point and pulled at the branch to get a better look—snap! The branch broke and dangled from the tree, hanging from what appeared to be a slimy tendon, just beneath the bark. I turned the branch this way and that as I looked it over, and found a little hole on one side.

There was a face. White and whiskered and weakly breathing, still alive. The bark around it was slimy and pulsating, as if trying to digest it. Its nose twitched and wheezed; its eyes were covered by the wood, but it could smell me.

Without thinking, I dug my fingers into the hole, clawing my way into the branch. Gritting my teeth and pulling, a disgusting wet noise like the ripping of muscle filled the air. The rabbit’s head slid from the hole in the branch and fell into my hands—several more of its pieces dropping into the ink below. I trembled in horror, barely able to keep ahold of it as the rabbit’s tiny eyes fell on me. They lingered for the briefest of moments, frightened and confused, before rolling lifelessly back. It slipped from my shaking fingers and sank into the slime.

From the base of the broken tree, the red sap was seeping into the ground. The viscous liquid was overflowing from the trunk, pooling around it in a sickening mixture with the muddy ink, rust-red. There was another tree bleeding sap only a few steps away, and another, and another. Their rotten, pulsating branches twitched with meek life being drained away, the excess oozing free.

One tree stood out from the rest, with a massive trunk and a forest of gnarled branches reaching into the void. A mess of chains was wrapped around the base, concealing the outline of an intricate carving. As I approached, I noticed little white rabbits sitting around the tree, sniffing and pawing the tree in a trance. They did not appear to notice me as they weakly clawed the bark, their noses twitching slowly and weakly. More than one was merely lying motionless in the muck and staring vacantly ahead, fur soaked with discolored slime.

I reached out my hand and traced the lines of the carving—they formed the shape of a body under the chains. They stretched up toward the branches, and down toward the trunk in the shape of legs and arms. Above the center, I saw primitive marks scratched into the wood, meant to be human features. A line nose, a circle mouth, and an X where each eye should be.

You should not have come here.

Jilted whispers that came from nowhere. Words that crept into my mind behind the rasp of wind rattling the dead branches. Light slipped through the tangle of trees, cast by the pearlescent moon above, and lit the chains. Beneath them, sickly, graying flesh, falling off the bone. A woman in a torn and molding dress, her arms chained tight to the branches just above the trunk like a martyred saint. Her eyes were sunken, dark, but I could feel them worming their gaze over me.

I am She, the maiden who speaks for Luna. I am known as Chang’e. It is through me that what you see is become a place of great suffering. Once beautiful, it now rots and withers.

A quiet, stilted breath came from the tree, like sobbing. In the pale moonlight, the decaying head of black hair looked this way and that toward the rabbits below.

The little ones revere me still, despite all I have done to them. Trust too freely given, faith in those who come bearing false smiles. I shall never atone for my sin.

I thought to question the woman in chains, but as I opened my mouth to speak its sunken eyes leered at me, bright and white like headlights in the dark, and the voice carried to me again in urgent tones.

This place is home now to a terrible witch. A being of avarice, her form absorbing all she sees. Her presence twists and perverts the land around her, the very trees overcome by her hunger. Leave, child of the Earth. Before she finds you.

The rabbits surrounding the tree turned their heads toward me, ruby eyes gleaming in the moonlight. Their ears twitched to and fro madly, searching for some distant sound I couldn’t detect, and all at once they recoiled in fear, ears standing straight up, before fleeing into the muck in all directions.

As if following after them, the moonlight peeking through the trees dispersed and I was again standing among darkened wood, ankle-deep in rust-red gunk. For a moment, silence permeated the trees and all was still.

A terrible noise bubbled up from the ink behind me. A churning, boiling sound that made the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end. I twisted around to look, my spine stiff in fear, and saw darkness welling up from below. The ink swelled into a bulbous mass before me, melting and burbling black, waves of tar flowing from it in an endless stream. Bony fingers emerged from bubbling abscesses, long fleshless arms stretching from the mass and dripping with ink. They felt blindly through the dark, slow and elegant as if tasting the night air. In its center, a swirling amalgamation of organs and bone with a depth I couldn’t perceive, ink gushing from inside like a bottomless well.

Slimy tendrils crawled from the top, cast wet over what looked to be a face, albeit misshapen and animal. Empty black sockets and a maw of smiling daggers gazed at the chained tree. The mass slid forward and shed the excess tar like a layer of skin, revealing a curved, melting form resembling something like a woman’s body. It paid me no mind as it wormed its way over to the tree.

Petrified, I watched as it clutched the ‘face’ carved into the tree with one of its hands and ran a bony claw down the ‘cheek’ with the other. A sound like laughter mixed with a deep growl arose from its throat, and though there were no muscles in its body to form a smile, I saw in its maw a malicious glee.

Alas, poor lunar maiden. I yet taste your sorrow among Luna’s roots. How sweet it is. Your flock is become mine. The blood of hares belongs to me.

The form shifted, its muck congealing solid for a brief moment as it turned to face me, before it began to again melt without end into the mire below. I felt a hungry curiosity press into me from those empty eyes as it extended a finger, dripping black, to point at me.

The vile stench of the Earth. The sickening rot of earthly soil. You, dog, are filthy with it. And you have something that is mine.

I felt something fuzzy touch the back of my neck. Turning my head, I saw a flash of silvery hair—a little white rabbit was clutching my shoulder, its shining violet eyes looking to me in terrified trepidation. Had it been with me all this time? It ducked its head to hide as the creature before me seemed to ooze anger, though its unmoving skull conveyed no emotion.

Give it to me.

On legs of black slime, it began toward me, rippling waves of muck sweeping over my knees. The trees around us seemed to shudder under the tide. I could feel its growling voice pressing into my head as it drew nearer.

The blood of hares is mine! Mine! Mine! MINE!

Its slimy hands slid into my collar and pressed into my skin, its sharp talons slicing into me with little effort. A terrifying roar came from the bed of dagger teeth just inches from my face. Unable to move or scream, I merely shut my eyes and waited for the end—when a high pitched squeal erupted next to my ear, shaking me from my terror.

“Witch! Usurper! Defiler!”

A golden ball of fuzz landed in the creature’s mop of slimy hair, clawing at its skull with all the fury it could muster. The terrible mass thrashed and writhed, its claws digging into the golden hare on its head, but the tiny thing would not relent. It gnashed its buck teeth and drove them into the bone, forming cracks that oozed black bubbling tar.

The creature became still, suffering blow after blow from the golden hare. The black liquid flowed in a torrent up its arms and arrived at its claws. It sank into the little rabbit’s fur, swirling over its body and enveloping it in black until it had been completely swallowed. There was a crunching noise, like chewing, until finally the thing lowered its dripping hands and the rabbit slid free from the ink, its body broken and twisted.

O hare of golden sunshine. Will you never learn? Your ilk live to serve me. Lie still in Luna’s embrace, give yourself over to me.

A gathering of white rabbits appeared from behind my legs, marred with tar, and watched with low ears as the broken rabbit sank into the mud. They chirped and squeaked in weak, sullen tones, looking to the being of slime and bone in defeat. They bowed their heads, one after another. An uneven, growling cackle filled the wood as the thing’s frame of floating ribs and organs turned to gaze at each one.

The smallest of lights appeared from the spot the golden hare had fallen. Tiny at first, it swelled from the centre of the muck, like a pool of sunlight expanding slowly in the black. The little rabbits took notice of it first and began to squeak in surprise; the creature’s howling laughter slowed to a confused giggle, crooking its skull with bemused curiosity.

Without thinking I dove into the bright pool below, my hand falling on something warm and metal. Wrapping my fingers around it, I lifted it with ease from the swamp’s clutches to reveal a golden hilt that housed a shining blade, emanating a resplendent light. Steam rose from the steel in billows, the filth melting cleanly away. The being of slime before me recoiled, its gelatinous body retreating into the ink.

I felt tiny paws grabbing my legs, little teeth nibbling my clothes. The rabbits around me were climbing up my legs and clinging to my arms, holding on for dear life. Their furry ears tickled my neck as they found places to hide along my shoulders, and before long I found myself housing a small army of white rabbits. The thing in the slime bubbled with rage, and the tar boiled hot around me.

You seek to steal that which belongs to me? I shall take your blood as well. Your eyes, your flesh, your humanity. They will be mine. All will become a part of me!

An eruption of black sent torrents of tar through the air, slapping against the trees. A great wave of the burning hot liquid surged toward me, but I stood my ground and held the gleaming sword aloft—and the wave dissipated before it, evaporating into steam in an instant.

The creature emerged from its dark retreat, empty eyes and vacant face staring me down with murderous intent that I could feel in my very core. It plunged its claws into the muck and the ooze churned in its center, gobs of gunk flowing from its body into the bog. Shadowy hands arose all around me, their twitching fingers adrip with ink, each making grabbing motions as if hungry for my flesh. I flashed the sword this way and that, its light my only shield.

A squeal from behind my ear—I shifted my weight and sliced the air, the sword sinking into a black, melting hand just inches from my face. It dropped lifelessly into the muck, its form collapsing all at once. Another panicked squeak, from my left; I swung again into a razor-bed of claws, lunging for my neck. The rabbits were quick to warn me, and the blade’s light expelled the hands like they were rays of shadow.

Then, several hands flung themselves at me, and I held the sword above my head, ducking in the mud. They grasped the sword, melting under the bright steel’s touch—but as each hand dissipated, another took its place, and another, and another. They surged forth from the mire endlessly and grasped at the sword, congealing solid until the blade’s light had been consumed and I was again enveloped in darkness.

A murmur of gurgled glee came from the slime-creature’s throat, a pleased victorious tune. It slid toward me, hunger in those vacant holes where eyes should be, until I could hear the gunk and organs that made up its being shifting in a disgusting mixture. Its jaw hung open, and a black, oozing tendril flowed forward from it. It ran up and down my cheek, leaving a wet mark; my skin crawled as though I was covered in ants. Its fleshless face inches away, I heard the faintest wisp of a voice, whispering inside my head.

The taste of the Earth. A nostalgic filth. I shall consume it all; all shall be a part of me.

A circle of hands arose from the gunk around me and grasped my arms, restraining me. The muck below congealed into a solid mass, holding my legs firmly in place. Then, the witch of the mire extended one of its claws and dragged it across my neck, breaking the skin just enough to trickle blood onto my collar and chest. My shoulders quivered as the little rabbits shook in terror.

The slime mass cut through my shirt, its fingers like razors, and pressed down my skin as if tasting my flesh, searching for just the right spot. Then, above my heart, it pierced my flesh with little fanfare, diving into my skin effortlessly. Its body pulsed, the amalgamation of gunk and bone and organ churning restlessly, as if excited, and a terrible numbing pain entered my skin. I thrashed and bit my lip and drew blood, I shouted and cursed and shook, but the hands held me firm. As my vision grew dark, I saw twisted glee in the the monster’s vacant eyes.

A shrill sound someplace far off roused me, the sound of a tiny being’s voice screeching in mixture of anger and terror. Muffled squeak-words that I could not quite make out, but could hear plain their desperation.

My hazy eyes, exhausted and muddled, opened to see a white puff of fur standing on my shoulder and glaring violet malice into the ink-spawn, its brilliant orbs like pools of bright moonlight. The creature merely passed the little rabbit a puzzled glance, unphased. Then, another rabbit on my body squealed at her, its red eyes gleaming bright. Another joined, its blinding bright eyes like headlights, and another, and another. My arms were lit bright with red eyes, each squeaking a threat.

The slime-witch withdrew its fingers from my chest, covered in blood, recoiling under the sight of them. Each red eye cast on its form unnerved the creature, and it had begun to back away—but anger soon replaced its confusion, and it bore its claws at the rabbits, meaning to slice them to ribbons. They clung to me desperately, eyes shutting tight as if awaiting the end.

I am the moon! Luna serves my will! And its subjects are mine! You will obey, you will become a part of me! Surrender your flesh to my desires!

My hands were unbearably hot. The hilt of the sword surged with the heat of a weapon freshly forged, so hot it felt like it might sear my skin. Tiny beams of light poked through holes in the grasping black fingers on the blade, growing larger and piercing through the hardened ooze until, in an explosion of mud, gunk and golden radiance, the sword burst free and the hands sunk into the bog. The shadowy limbs grasping my shoulders grew weak and evaporated into steam under the light, and in the sightless husk of the creature before me, I saw something like fear—and burning rage. The gunk all around me had reached a bubbling boil, churning restlessly.

The slime-creature, gnashing its dagger-teeth, filled the wood with a spine-chilling roar. Flashing its claws, it lunged at me with a desperate, animal fervor—and I swung the sword straight down, cutting its arm of bone and slime-sinew in twine.

It stumbled in the mire, confused. A flash of pain in its unmoving expression, a shudder of quaking slime as its body expelled muck through the gaping hole where its arm once was. I grit my teeth and drove the blade forward, piercing its churning core. The darkness inside wrapped around the sheen, the sword becoming as dark as night, then swelling up like a boil, ready to burst. The creature clawed and thrashed at the hilt, beams of light emerging from its body, radiant pools of the sun expanding over the surface of its form. Then, all at once, its body expanded, stretching and contorting until it tore open. It wailed in pain, the screeching voice in my head felt like it might pierce my skull.

Mine, mine, mine! The hares are mine… All will be a part of me…

Waves of slime poured over me, gushing forth from the creature’s ruptured body. In the center of the beast was the sword’s resplendence, melting away the mire inch by inch. The slime-witch’s body dispersed into mist, rising into the air as black vapor. It disappeared little by little until there was nothing left.

Soft sobbing, exhausted gasps of breath. A young girl sat on her knees in the mud, her clothes and silver hair soaked with filth, and she wept. The rabbits had gathered all around her, their ears fallen sullenly, looking on in shame. As I wearily took a step forward to approach her, she went silent.

I placed a hand on her shoulder, and her pale face peeked through a mat of wet hair to look at me. Her eyelids slowly peeled open to reveal two violet moons gazing up at me. I fell into them, and the space around us faded away.

When I opened my eyes again, I was back in the crumbling walls of my tiny apartment, staring at the black void on the face of the monolithic machine that sat in the corner. I withdrew my hand from its body and sighed, shaking my head to get out the cobwebs.

The rabbit-girl sat in her stool, her face wet with tears. Roused from her slumber, she stretched her arms and twiddled her toes. Wiping her face, she gazed up at me curiously.

“Good… morning. Is—ahm—everything? Okay?” she squeaked, noting the disturbed look on my face.

I shook my head. “You were just mumbling in your sleep, that’s all. I think you fell asleep in your chair and were having a bad dream.”

“O-oh. It is—ah—late,” she murmured, her voice one tired note after another. “Yes. I, I should go. To sleep, you are right.”

Still dressed in her skirt and blouse, she scuttled past me and crawled under the blankets of the one bed in the room, curling up until the sheets were balled up around her. The fuzzy rabbit ears on her head dipped and twitched in my direction, and she lifted her head to look at me, still left standing there in a stupor.

“Good-night,” she called to me, sleepily.

“... Goodnight,” I said, my voice an exhausted croak.

I returned to my chair, looked to the humming machine once more, and closed my eyes.

0 notes

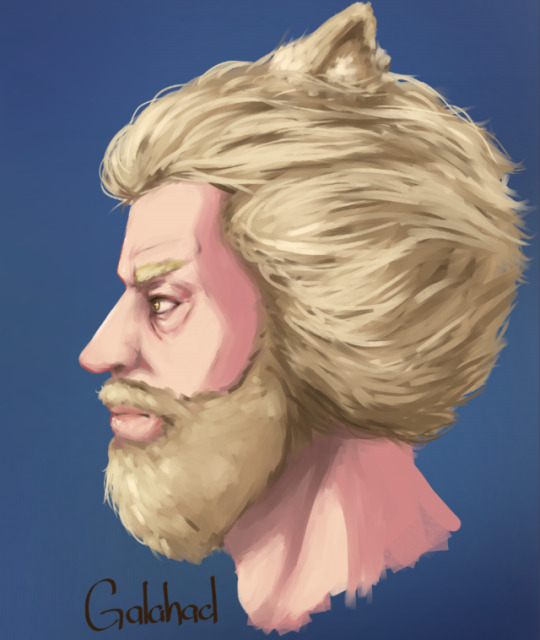

Photo

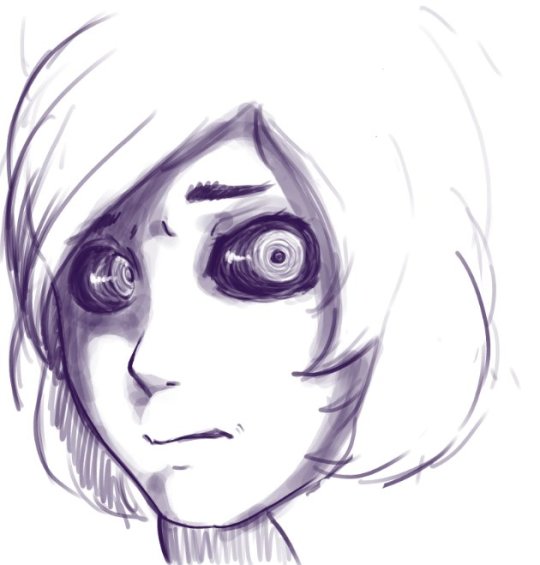

"I left you far behind, the ruins of the life you had in mind. And though you still can't see, I know your mind's made up, you're gonna cause more misery."

Galahad by ChefHART.

0 notes

Text

The Walrus

The garden near the gate of Church Mouse shifted underneath the maid’s fingers, the soil as soft and malleable as clay. The evening rains had softened the ground, and so with the tips of her dress half-dipped in mud, she prepared little beds to tuck the sleeping crowns of dormant strawberries into. Before long, a field of strawberry royalty laid slumbering, not far from the flowerbeds and the sapling peach tree.

The maid girl stood up, brushed off her hands on her white apron, and dug into her pocket for a silver watch. Flipping open the lid, the timepiece told of a midmorning lull. A time when her sister would be taking the first of many breaks from her duties—and the cigarette smoke wafting over from the building’s side entrance confirmed this—and when her master would have finished dissecting her breakfast and, on a good day, gone back to bed.

Sighing, she wiped her brow and pocketed the watch. Hours of working in relative solitude stood before her, as the flowers needed tending, the halls swept, the library dusted and tidied, the details of supper prepared—and her sister was unlikely to be of much help.

Before she could put two feet onto the cobblestone steps that lead into the Gallery, however, the double doors burst open to reveal a tall woman in a sleeping cap and pajamas, patterned with little rabbits leaping over crescent moons. She held with her forefinger and thumb a steaming tea cup, raised in thoughtful trepidation to her mouth. Spotting the muddy maid in the yard, she rose an eyebrow and smiled.

“Goodness, Ethel—I thought to find you planting the strawberries. Ne’er would I imagine you digging a new warren below the Gallery,” she snickered, and took a sip from her cup.

“Lady Beatrix,” the maid addressed her, giving a shallow curtsy. “How did you find your breakfast? Were the pickled goose eggs and blood sausages to your liking? The recipe was new to me, and—”

“Never mind that,” Beatrix interrupted. Draining her cup of tea, she stepped through the garden on her fluffy slippers toward the peach tree. With the teacup held by one finger, she placed her hand against her chin and stared at it a moment, deep in thought.

“Lady Beatrix?” Ethel questioned, her long lop ears pulled by gravity as her head tilted sideways in curiosity.

“Nay—no one, I think, is within my tree. But shouldst they be, ‘twould be high. Or mayhap low?” the Church Mouse hermit mused, tapping the porcelain cup against her lips and looking the sapling up and down. “That is, perchance, they could not attune. Nevertheless, ‘tis no great matter.”

The rabbit maid tiptoed cautiously through the sprouting turnips toward her master, and touched her gently on the shoulder. “Are you quite alright, my Lady? I know it has been a few days since you’ve been outside, and you are not accustomed to being awake at this time of the morning, so...“

“Oh, dearest Ethel. How easy life must be, thine eyes closed, misunderstanding all you see,” Beatrix quipped, patting her servant with an open palm atop her crown. “I do admit, ‘tis difficult, at times, to be as I am. To be someone—yet, time doth push forever on. It matters naught to me.”

“I do not, um…”

“Do for me a favor and humor my musings, wouldst you?” Beatrix asked, staring at the tree. Ethel gave a hasty nod, and Beatrix continued, “Always—nay, only but sometimes—do I think it is but me, amid a quiet dream. A bough of Luna’s tree I have crawled upon, and where I do lay in a long slumber. The Earth far away, and little rabbits to have ne’er found their homes in its holes.”

“I—”

“I should say, I know what is a ‘dream,’ and what is not. That is, I think, I disagree. And as such, my tree is empty,” Beatrix said, taking a leaf of the peach tree between her fingers and feeling its ridges. “Do I live, truly? The question doth weigh upon my mind, though I breathe, and though I eat, and though thine ears do hear my words and responses come in kind. I think I know—but, alas. It is all wrong. The questions, a disquiet doubt. It be not still.”

“What... what are you saying, my Lady? You think me an illusion? That nothing around you is real?” Ethel stammered, her concern palpable. Though the master of Church Mouse was an eccentric, Ethel had always considered her to be of sound mind.

“‘Twas nothing real, shouldst be there nothing to become hung upon. Nay—I am she, as you are thee, as you are me, as we are all together. And here, upon this wet ground, I stand, the walrus in a walled garden. Were I to leave, wouldst I find a burning sun in the dead of night and a giggling gaggle of clamshelled schoolgirls?” the hermit presented her question in a deathly serious tone, and sat her teacup atop the rabbit girl’s head.

“So, you are saying—” Ethel took the cup in her hands to keep it from tumbling to the ground, “You believe yourself to be real, but what surrounds you, perhaps not?”

Beatrix shook her head. “‘Tis an idle musing, nothing more. The pull of Luna would lead me to believe that all I have lived upon this Earth be a dream, and her shores to be the only true life I have within me. A troublesome, tedious thought, ‘tis not? You know it to not be true. Prithee—you do know it, verily?”

The hermit woman regarded her servant with a gaze that conflicted with her confident tone, her cold eyes somewhere adjacent to desperation. Ethel gave a slow nod, unsure what to think, but certain that a delayed response would only make the situation worse. Beatrix drew a deep breath through her nostrils and sighed shortly.

"I shalt be in mine chambers,” she sternly announced, turning toward the double doors of the Gallery. “Pray, Ethel—for tonight’s supper, do instill Matilda with the importance of avoiding setting our kitchen ablaze.”

The oak door to the hermit’s room was shut fast for the remainder of daylight, as silent as a crypt. Ethel went about her duties, cleaning the Gallery from top to bottom. She passed the door again and again as she swept and dusted and flew from one room to the next, straightening cupboards and alphabetizing books in Lunish. She considered knocking a few times if only to reaffirm Beatrix’s well-being, but whatever worries she held for her master were kept in check by the wrath she knew awaited her, should she disturb the hermit’s solitude.

With the night’s meal of vegetable and beef stew, buttered biscuits and tea prepared, Ethel was at a loss for what to do. She sat in a wooden rocking chair in the hall across from Beatrix’s room and waited, her nose buried in recipe book sniffing for simple things to teach Matilda. Just as she’d found a page on an easy peach cobbler, the hermit’s door burst open, and the rabbit girl nearly leapt from her seat.

“Lady B-Beatrix!” she stuttered, standing with startled haste.

The Lunarian woman looked up and down the hall, then down at her fingernails. Her brows shifted in curiosity, as if unsure of what she was seeing. She wore a lavender jacket and gown, the cuffs and hem near her feet stained red. Ethel’s eyes trailed downward—there on the floor was a pool of dark liquid, only just illuminated by the dim light of the nearby lamp. It soaked into the hermit’s fuzzy slippers, their bottoms deeply crimson.

“My Lady... are you quite alright? You look awfully pale, and—”

“Ethel,” the Lunarian curtly cut her servant off, “Fetch your coat and meet me in the garden.”

“Oh... Are you certain? Dinner is prepared. Matilda and I were simply waiting for you...”

“Yes, Matilda. Bring her as well. I shall need witnesses,” Beatrix ordered, her voice monotone.

Without another word, she returned to her chambers and shut the door behind her with a loud clack. Left standing there, Ethel set the book down in her chair and lingered a moment in the hallway, watching dark red liquid seep through the crack beneath the door. She felt her foot thump the floor unconsciously, and made for the dining room in a nervous hurry.

The pines sheltering Church Mouse shook under the wind and rain blowing through the streets, two rabbit girls below them shrouded in hoods. The smaller girl’s face hid inside a cocoon of fuzzy white cotton, but gazed at her sister with an annoyed frown all the same.

“What the hell is taking that crazed moonie? How long do I gotta stand out here in the rain?” Matilda fumed, tugging her hood tight.

“I am not certain—she merely said to meet her here. I cannot deny she has been acting strange; just this morning we had a very odd conversation,” said Ethel, her finger to her chin.

“Oh? She give you that spiel about ‘Lucy in the sky’ again? I swear to God, if I have to hear one more of her stupid poems...”

“It was something about her ‘tree’ being empty. And I believe a walrus was involved? I’m not entirely sure, to be quite forward with you.”

The doors of the Gallery swung wide, the figure of its tall and slim master slipping through the threshold. She had dressed herself in a long, green cloak with a hood, the lavender gown and fuzzy slippers exchanged for a simple brown dress and leather boots. Acknowledging her servants with only a single glance each, she made through the garden with purpose towards the sapling peach tree.

“Lady Beatrix? Are we going someplace, so late at night?” Ethel questioned, her voice a mixture of apprehension and curiosity.

“Verily, we are. There is something I must see—I must know if I am right, and such a chance comes but once a blue moon. Above us, Luna is shone brightly. I must see her again,” the hermit answered, taking in hand a small hedge clipper from her cloak.

“What’re you talking about, crazy lady? Speak sense. If you need to see the moon, just look up, then! Why do I have to get all wet for that?” Matilda grumbled, scowling at her.

“Matilda, open thy ears. If thou dost not know of what one speaks, nor how to appreciate Luna on such a bright and clear night—” Beatrix turned toward her small servant, those cold, unblinking eyes boring holes into the girl, “—then merely keep thyself quiet and do as I say.”

The small rabbit girl shrunk in surprise, her mouth silently agape. Returning to the tree, Beatrix searched the tree’s limbs top to bottom, placing the thin branches between the shears and considering, then moving on to another. She repeated this process several times before finally coming across a bough that split into two smaller branches. Clipping it cleanly from the tree, she carried it to the two obedient rabbits staring confoundedly at her.

“This will do,” Beatrix declared, and handed it to a very confused Ethel.

“Whatever for?” came the servant’s reply, turning the very ordinary tree branch over in her hands to examine it.

“It shalt serve as our link and guide our path,” Beatrix said. She made for the fence gate, undoing the latch and crossing onto the sidewalk. “Do not tarry—we’ve a long journey ahead of us and only so much moonlight.”

The two rabbits looked at one another, bewildered, the hermit’s words only raising more questions in their minds. Ethel’s emerald green eyes quivered with worry, but the perturbed look on her sister’s face spoke clearly she was convinced the exiled Lunarian had finally lost her marbles.

The hermit’s long legs carried her swiftly down the sidewalks, pursuing the end of each street like a woman possessed. The two rabbits hurried after her, in constant danger of being left behind. Beatrix was hardly watching where she was going, her head turned upward to stare at the brightly shining full moon. They crossed a patch of broken road into a tiny lot preserving a single tree, and descended into the deep, old, forgotten suburbs, past the overgrown, forested train tracks.