Text

Signs of the times

This morning, Easter Sunday, I got up at dawn to take my daily exercise. Not a run today, but instead with my camera in hand I planned to walk the length of Upper Street, London, heading north from Angel tube station.

It’s about a mile and home to a good 100 or 200 businesses, not one of them unaffected by the current Covid-19 situation.

Restaurants, bars, cafes, clothes shops, charity shops, estate agents, pharmacies. Almost every single one is displaying a sign explaining their own particular state of business-not-as-usual.

These signs range from hastily-scribbled handmade notes to the professionally typeset and printed. And an appropriately well-mounted one in the local framing shop.

The content of the signs range from practical redirections to online alternatives, to the personal and poignant notes from proprietors.

It was a bizarre and melancholic sight to see such a bustling street, that I know so well, sitting idle and forlorn. Some of the businesses inevitably won’t survive, but by the time I reached the newly-redeveloped Highbury Corner at the top of Upper Street, the overwhelming sense I was left with was one of solidarity and hope.

0 notes

Text

Diffusion of innovations

An idea so good it will sell itself

When Vasco da Gama sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in 1497 more than half of his crew of 160 died of scurvy. That ratio was not uncommon, and it's reported that scurvy killed more sailors than warfare, accidents or anything else.

Imagine if you had a new innovation that could prevent scurvy. People would be begging you for the answer and you'd immediately become a hero wouldn't you?

Over a hundred years later in 1601 an English sea captain called James Lancaster had a hypothesis that lemon juice would prevent scurvy.

Not only was his hypothesis correct, since we now know that scurvy is caused by vitamin C deficiency, but he conducted an experiment which was pretty compelling. He gave sailors on one of his ships a ration of lemon juice and not a single sailor got scurvy on that ship.

The sailors on the other three ships died in large and predictable numbers. He had to transfer sailors from the first ship to man the others in order to continue the voyage.

You'd think the British Navy would immediately adopt, or at least trial, this new innovation that was simple and cheap, and pretty much 100% effective.

But it wasn't until 1795, nearly two hundred years after Lancaster's successful experiment, and three hundred after Vasco da Gama's time, that the Navy finally prescribed citrus to all its sailors (the origin of the term limey for a Brit). It took even longer to reach the merchant marine.

It seems incomprehensible that a simple innovation that would wipe out scurvy and go on to save thousands of lives took so long to be adopted. You could argue that slower communication and dissemination of information slowed adoption - but by three hundred years?

It demonstrates that just having a good idea is not enough.

Dvorak keyboard

To take a more recent example, you may have heard of the Dvorak keyboard. Even if you have, you probably don't know anyone who uses one.

We know the story that the QWERTY keyboard was specifically designed to slow down typing so that the mechanical arms of typewriters wouldn't get jammed. That mechanical constraint is long gone but the layout remains ubiquitous.

The Dvorak keyboard has obvious and significant advantages over the QWERTY keyboard. Typists using it have broken all speed typing records. It also results in fewer strain injuries from prolonged keyboard use.

You could even turn your own computer's keyboard into a Dvorak one right now (albeit with some stickers on your keys or an overlay).

Despite its objective strengths almost no one uses a Dvorak keyboard.

It's not the case that innovation in text input technology has been stagnant, but the current standard keyboard it so entrenched that many innovations have been built around its inherent weaknesses – predictive text, swiping text, etc.

Again, we see that what seem like a good idea doesn't necessarily diffuse and get adopted rapidly, or at all.

Diffusion of Innovations

Those are two examples from the introduction of the book Diffusion of Innovations originally written in 1963 by Everett Rogers, an assistant professor of rural sociology at Ohio State University. It’s testament to the immutable principles of economics, human behaviour and psychology that his ideas are still so relevant today.

Crossing the Chasm by Geoffrey Moore published in 1991 is probably the more well-known book, and it builds upon the foundations that Rogers outlined over half a century ago.

Adoption

In Crossing the Chasm, Moore argues there is a chasm between the early adopters of a product and the early majority. If an innovation is to really succeed it must have appeal beyond the gadget fans, geeks and tinkerers.

You could argue that approaching the third decade of the 21st century, a globalised and more accessible market increases the absolute number of potential early adopters and a significant business can be built without needing to cross the chasm.

But if you look at it as more of a continuum, then there are necessary characteristics of an innovation that will drive a product along the innovation adoption life-cycle. These hold true equally when your innovation is making the leap beyond your immediate family, as to when it's making the leap to a new continent.

In his book, Rogers distilled these characteristics down into five factors that affect the adoption of an innovation.

Rogers’ five factors

Relative advantage

Complexity

Compatibility

Trialability

Obersvability

These five factors are a great way to frame your strategic thinking around the adoption of your product or service. The key thing is, to a greater or lesser extent, they all need to be addressed. As we've seen in the historical examples above, one of them is not enough. And even addressing four out of the five may not be enough.

1. Relative advantage

Relative advantage is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being better than the idea it supersedes.

This is perhaps the most obvious one. People are unlikely to start using a new product if it isn’t better than what they use already. There are many dimensions to this though, so we need to think about why something new is better. Rogers also refers to perception in all of his five factors. Relative advantage doesn't just mean better technical specs.

Relativity is also important here. The advantage is not only relative to the incumbent solutions, but also to the specific group of users who are your target adopters.

Relative advantage however is necessary but not sufficient, and as with the cases of lime juice and the Dvorak keyboard, this one of the five factors doesn't guarantee success.

2. Complexity

Complexity is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as relatively difficult to understand and use.

Also fairly obvious; if a new product is perceived as complex and difficult to use, it will reduce the level and rate of adoption. An example here is early personal computers where you had to understand computer programming to use them. Once a graphical user interface and a mouse were introduced, far more people felt that a computer was something they could make use of.

In contrast, mobile phones, although technically complex, had fewer barriers due to perceived simplicity of use. The first mobile phones were operated much like the existing landline phone technology – buttons for 0-9 and a memory for storing a few most-used phone numbers. Crucially, the new technology was also compatible with the old system – a mobile phone could be used to call a landline and visa versa.

Simplicity and ease of use could be seen as relative advantages as above, but there's also a risk that increased functionality in the pursuit of relative advantage can result in greater complexity. It's up to the innovator to balance these opposing forces.

3. Compatibility

Compatibility is the degree to which an innovation is perceived as consistent with the existing values, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters.

Rogers originally looked at compatibility of an innovation with reference to social and psychological factors. He gave the example of how even the naming of an innovation must be compatible with the intended users. Trying to introduce a new a car called a Nova (which General Motors did) is probably a bad idea for the Spanish-speaking market where no va means "no-go".

One reason the Dvorak keyboard hasn't gained acceptance is that it's not compatible with people's knowledge and experience of typing. The cognitive cost of learning to type again clearly puts most people off.

For 21st century technological innovations I believe there's a whole new side to how we can interpret compatibility. Compatibility has some very practical implications when it comes to the hardware and software of our modern daily lives. A lack of compatibility can be very frustrating when you can't find the right type of charger for your phone, or you find out a computer game you want to play isn't available for your particular games console.

It's a factor that has been exploited by companies such as Apple where they've built their own ecosystem of compatibility which puts up a barrier to adoption for others.

4. Trialability

Trialability is the degree to which an innovation may be experimented with on a limited basis.

This factor is particularly important for early adopters where investing their time and money into an untested new innovation may be seen as a risk. Later adopters are more likely to see peers using a new innovation, which can either offer a chance to vicariously trial something new, or enable a trial in a more practical sense such as borrowing a friends mobile phone to make a call.

To take that idea one step further, the internet enables potential adopters to go beyond their peers and see a new innovation in use as part of YouTube reviews and on other more specialist forums.

Trialability can be designed into a product. This is common in software products where a freemium pricing model is used and users are given free, or very cheap, access to a digital product. The theory is that once that initial barrier is lowered and users have tried the new product, they will see its value and be prepared to pay for it.

Getting users 'hooked' on your product is a whole subject in itself and excellently covered in Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products by Nir Eyal.

For some new innovations though, such as a new layout for a computer keyboard, the learning curve may be too steep, even if users are given ample opportunity to try it first.

5. Observability

Observability is the degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others.

Something has to be seen before it can be adopted. Marketing can be part of this, but Rogers discusses more organic observation such as people seeing new solar panels on a neighbour's roof and later installing their own.

In some cases, like the watching of YouTube review videos mentioned above, observing something being used can act as a secondary trialability too.

Greater observability could be another reason why mobile phones were adopted faster than home computers. Not only were they naturally more likely to be observed in use, early users often saw them as status symbols and went to extra efforts to ensure they were being seen using their new mobile phones.

In general, hardware is more observable than software. That, combined with the negligible marginal cost of shipping software to a new customer are good reasons that businesses often offer free trials for their software products.

But as with the other factors, this is not enough on its own. As we've seen, the Dvorak keyboard is fairly well known. Not only that, it's nearly always talked about in the context of its usability advantages. But almost no one uses one.

Build it and they will come

They won't.

According to Rogers' research, "most of the variance in the rate of adoption of innovation, from 49 to 87 percent, is explained by these five factors".

So to maximise the chance of your innovation gaining adoption in the market, these should be addressed. Building what you think is a great, innovative product and expecting customers to come to you isn't realistic.

Build your product with focus on a significant relative advantage compared to other products. Design to reduce complexity and increase compatibility. Increase trialiablity and obrservability.

Perception is everything and everything is relative.

References

Diffusion of Innovations (Fifth Edition), Everett M. Rogers, Free Press, 2003

Invention and Innovation, E. Taylor, The Open University, 2010

0 notes

Text

Hacking a vintage radio to make a modern speaker

This is the second one of these hacks I’ve done. The idea is a simple one: to have a small table-top speaker you can plug your phone into, but one that has more of a vintage style than a modern plastic docking station.

This was the starting point: a broken old Roberts radio set bought for a few pounds on eBay.

And the electronics came from a newish pair of computer speakers.

The whole point of using an old radio was to build something you’d be happy to give pride of place in your living room. I love the details and build quality of these things.

This is the single speaker from the old radio - from a time when these things were still made in England.

The big old components inside the Roberts radio.

And the modern equivalent...

Making sure it all works before assembling everything back into the Roberts radio body.

Not necessarily the most beautifully craftsmanship I’ve ever produced.

The finished product!

And to prove that it actually works...

youtube

0 notes

Text

It's been exactly two years since the Ockham Razor project funded on Kickstarter.

If you know Kickstarter you'll understand that the campaign is neither the beginning nor the end of the process. This time two years ago I had a fully-speced razor design (thanks to Nick and Bec!), prototypes, photos, a video, a manufacturer lined up, funding and some sense that there was a market for my idea.

Being my first crowdfunding campaign I really had no idea what to expect. Of course I dreamt that I would raise the money and quickly take over the world with the most beautiful cartridge razor ever made. But at the same time I was extremely nervous that the campaign would fail and the Ockham Razor would never get off the drawing board.

This was the very first prototype of what was to become the Ockham Razor. I made it by hacking the end of a Gillette razor and gluing it to a piece of aluminium. If the campaign had failed it would probably have remained the only one in the world and I might even still be using it today.

But the campaign succeeded, thanks to the 570 people who backed my idea and everyone who supported us and spread the word about the Ockham Razor.

What now?

I manufactured a second batch of razors recently and they are now available for anyone to buy via the Ockham Razor website. They're also available in a very cool shop in central London, Beast, and will soon also be available in other places.

Genuine Gillette parts

An early design decision was to make the razor compatible with standard Gillette Mach 3 blades. These blades are very well regarded and provide a tried-and-tested close, comfortable shave. And you can buy them anywhere in the world.

The Ockham Razor handle was, and still is, made by us in England. The only other part in the razor is the small plastic assembly that fits in the end where the razor cartridge attaches.

Initially I found a supplier in China for these parts, but dealing with China had its issues and it made things rather difficult at times.

However, the latest batch of razors has now been made with genuine Gillette parts which is really exciting news!

I'd been trying to find a more dependable supplier for the parts for a while, and then late last year I met some guys from Gillette at an event. We were talking and it turned out they had already been thinking about supplying small start-ups like the Ockham Razor Company with parts. One of them even said "hey, you're the Ockham Razor guy!" which was rather nice.

Anyway, it took a while to get the deal signed off, but I'm thrilled to know that the cartridge mechanism is of the best possible quality.

The future

Thanks again to everyone who backed the Kickstarter campaign two years ago and all of you who have bought a razor since. It's so great to hear feedback from people who enjoy using the razor and it makes all the hard work worth it.

I still have plans for more products like a brush, a holder and perhaps a razor cover, so keep an eye out for future updates!

0 notes

Text

Radio Garden - World Wide Radio

Last week I discovered the best thing I’ve seen on the internet for years.

Based on nothing more robust than the first result returned by Google, there are apparently over a billion websites out there. Putting aside how accurate that number is and how you might want to define ‘website’, I’m sure we can agree that there are loads of them.

People with more insight than me have no doubt studied what types of websites make up that number. My daily online interactions are probably fairly typical: dominated by Google, social media, news sites, and then a long tail made up of train enquiries, checks on local café opening times, and argument-ending verifications of actors’ ages (although google.com is increasingly removing the need to click past it for those last few things).

So it’s rare to discover something truly new and brilliant on the web. When I came across Radio Garden last week, thanks to an old friend on Facebook, it blew my socks off.

Radio Garden

The concept is a simple one: take all the internet radio stations you can find, add a geolocation, and plot them on a map.

The resulting Radio Garden is not only beautiful, but inescapably compelling. I defy you to not get immediately drawn into it.

Internet radio stations aren’t particularly new, and it naturally follows that there are websites which list them.

But by adding a map layer with which to browse the content, the team behind Radio Garden have turned something rather soulless, albeit fundamentally interesting, into something wonderful. If you think visual and interaction design don’t matter, then just observe someone using the two different sites above.

In addition to the clean and simple design, there are delightful little touches: the way the earth rotates into position and the live radio streams ‘sprout’ from its surface, and the static as you move between channels (an anachronism younger visitors may not even appreciate).

You could argue that simplicity comes at a cost - that some desired functionality has been lost - such as being able to search by genre, or even knowing which country you’re browsing in. But then I feel that would be missing the point.

Where will you go?

It’s very interesting to see where someone goes first when they arrive at the site. No one I’ve shown it to hasn’t immediately zoomed in somewhere and been immediately captivated.

By default your journey starts wherever you happen to be, which for me is London. In large cities like London there are plenty of stations to choose from and in this case they reflect the eclectic, global melting pot that is our capital.

In addition to the many BBC stations, there are other national, even international, ones such as Virgin Radio and BFBS, but most fascinating to me are the niche music stations and the community stations which reflect the city’s diverse diaspora – Punjabi, Greek, Polish to pick out just a few.

Thankfully, The Christmas Station now seems to have gone off air.

After London I took a quick trip up the M11 to my hometown of Cambridge where I found and old favourite, Cam FM: great music, occasional awkward gaps between songs.

Then I was drawn to Africa. Via Casablanca, I headed south to the lone green dot that turned out to be MaliJet in Bamako (which sadly seems to have disappeared subsequently).

The lack of political boundaries and labels does add to the serendipity of it all, and as I headed east I found myself in Aleppo. So close, yet so far. It’s surreal to hear something as normal as a radio broadcast coming from somewhere so troubled.

Heading further afield was my next inclination. I discovered soft rock in Siberia, national radio in the Pacific island nation of Kiribati, and a station in Alaska who proclaimed the bold mission: “Spreading the Gospel to Western Alaska and the Russian Far East.”

Most radio stations on the map have a link through to the broadcaster’s own website. Staying in Alaska, the northernmost point in the USA provided a distant taste of the kind of parochial news you’ll find in newspapers everywhere.

As I write the local headlines are as follows:

“Freezing temps mean it’s time to clean the legacy wells on the North Slope; Melting permafrost changes Yukon River; Bogoslof spews lava in fourth eruption; Green Lake dam awaits replacement part to get back up and running; Ground squirrel: Invasive species or native to island?; Prince of Wales deer season extended, wolf season ended...

Searching for the Blues

With my appetite for novelty satiated, I wanted to find some decent music.

I have fond memories of listening to the radio while travelling through the Deep South on a road trip a few years ago, so I went in search of some blues.

My quest was quickly stymied however by the Christian stations flooding the http waves. In parts of Alabama and Georgia it was hard to find a broadcast that wasn’t religious.

It made me realise that for any liberal European who’s only been to New York and California, there are vast swathes of the country that are either completely ignored or at least misunderstood. If you’re dumbfounded by Donald Trump’s popularity and political success, take yourself on a radiophonic journey from New Orleans to Virginia.

I still haven’t found my blues on Radio Garden, despite the promising-sounding American Blues Network in Gulfport Mississippi. If anyone finds a good station, please let me know!

I had more luck across the Florida Straits in Havana though, and have regularly been enjoying the music on Radio Cubana.

I could go on - and indeed I did - but with Radio Garden as your guide, I’ll leave you to make your own way around the world’s radio stations.

Embrace the lack of a search bar, the lack of borders and recognizable place names, and enjoy the almost analog, organic experience of flying around the world tuning into distant sounds.

I can’t speak for Tim Berners Lee, but if I’d invented the World Wide Web I’d be thrilled to see it sprout a gem like Radio Garden.

0 notes

Text

Six differences between two Kickstarter campaigns

I’ve just finished shipping the rewards for my second Kickstarter project.

Once again, it’s been a lot of hard work, but also a lot of fun.

In some ways my second campaign was less stressful and I felt slightly more in control having already done one before. Only slightly though, and there’s still lots to learn.

At my last Crowdfunding London meetup I went through the differences between my first and second campaigns and here are my observations.

Firstly, it’s interesting to note that it’s not that unusual for someone to run more than one Kickstarter campaign.

According to their own data, there are 22,000 Kickstarter creators who have launched more than one project - that’s 12% of all creators - and many who have launched even more.

The data also suggests that the more projects you do, the better they get. That’s not that surprising, but I suspect there are many contributing factors to that phenomenon.

Success breeds success

I know a few people who have run multiple campaigns and their stories back up that data.

The two Riut projects by Sarah Giblin

The Riut bag was one of the first campaigns I had a serious look at when I was planning my own debut on Kickstarter. The campaign was really well run, and then a year later Sarah, the creator, built upon her success with another.

You can see her projects on Kickstarter here and here.

The first campaign finished up at over 200% funded, and the second at over 300%. The absolute figures are impressive too.

A couple of interesting things to note: The second one did incredibly well, despite not being a staff pick like the first; and the second campaign achieved well over twice the funding amount with only 50% more backers than the first.

Here are six differences between my first and my second Kickstarter campaigns.

Difference 1 - the products

The first big difference between by two Kickstarter projects was the actual products themselves.

The Ockham Razor and The Sticker Project

You may be wondering if there is a connection between the two projects somehow. Well, there pretty much isn’t. It’s not a wise tactic, but that’s what I did. I could even say that it makes this blog post a bit more interesting from a statistical analysis point of view, but that was obviously not my intention.

My two projects were of course not run in total isolation however. I carried over an engaged backer audience from my first campaign which probably gave me a head-start. And the products had some overlap in the type of audience they appealed to. Indeed, both campaigns were featured in some of the same design/style/tech websites.

Difference 2 - the project progress

The second difference was how the campaigns played out. Looking at the overview stats for each project below, note the change in gradients over the duration of the campaign. (The gradient shows the rate at which the project was funded - a steep gradient correlates perfectly with my excitement levels.)

Overview stats for the Ockham Razor campaign

Overview stats for the Sticker Project

A strong start is a great indicator of a project’s likely success, but my first campaign got off to a relatively slow one.

The Sticker project had a much better start and I put that largely down to me making more effort to get as many people as I could to back the project on day one - ideally hour one!

After that, both campaigns had a crazy couple of days a week or two in. These spikes were both caused by the projects being featured on popular websites: Uncrate and Gizmodo respectively.

You can see those spikes in the charts below. More about the Gizmodo spike to come...

Pledges per day

Difference 3 - early focus on a different number

This was perhaps the single biggest difference between how I handled both projects once they were launched.

I simply put all my focus on a different number the second time around.

For the first campaign I concentrated on the amount of money my project was raising. It became an obsession as, naturally, I thought it was really cool that people seemed to believe in my product and were actually giving me their cash.

The second time around, I wanted to get a better start, and that meant that lots of people had to take an early interest. The theory was that if it started well, pledges, and therefore the money, would come.

I’d read about the way Kickstarter positions campaigns on the Discover pages on their website and it sounded like the number of backers was an important factor.

Whether that’s true or not, it makes sense that to build momentum, you need lots of people to take notice - which is pretty much the point of crowdfunding.

If 100 people back your campaign on the first day and a few of them share their enthusiasm on social media, that quickly gets your project in front of an awful lot of potential backers.

In the case of my second campaign, people could pledge for stickers from only £5 which I think helped make sure friends and family committed to a pledge. In contrast, on my Ockham Razor campaign a standard razor cost £30 which is a bit more of a barrier.

So for my second campaign, my obsession was backers and not pledge amount, and I think that helped. I’d much rather end day one with 100 backers and £100 than with one backer and £500.

Focus on number of backers

Difference 4 - better targeting

For both campaigns, I had a fairly unsophisticated outbound marketing strategy.

Bascially, I scoured the internet for articles and blog posts about razors/design/Kickstarter/stickers etc. When I found ones that looked relevant I did my best to get in touch with the authors to pitch my story.

The result was this rather long list of people, contacts, and context.

My “reach-out” list

The difference for my second campaign was that I was a bit more discerning about who I got in touch with based on what I thought their influence and reach could be.

At the same time I was probably more relentless in following up with those people that I had chosen - so I spent more time chasing the promising leads, rather than spreading my efforts more thinly with as many as I could.

I also had the advantage that for the second campaign I was able to approach people who had written about my first campaign. This probably meant they were at least more likely to read my email, and that probably helped.

But as I said earlier, having a second product that followed on more logically from the first would have been even better.

Difference 5 - less time, more data

A week into my second campaign, I started a new job. That meant that I had a lot less time to spend focusing on Kickstarter and so I had to be a bit smarter.

I used tools like Boomerang for Gmail to schedule emails which allowed me to do more of the leg work up-front when I had the time.

I also added Google Analytics tracking to my Kickstarter page which I didn’t do the first time. This gave me more precise referral data which gave me better feedback on the outbound marketing efforts I mentioned earlier.

Difference 6 - the big break

Although both campaigns had significant jumps in backers caused by a widely-seen review on a website, the second campaign had a truly momentous jump in backers caused by that one Gizmodo article I mentioned earlier.

You can see on the ‘pledges per day’ chart above that things had really slowed after a good start to the campaign. But then one afternoon, my Kickstarter backer emails went crazy.

It was obviously an exciting moment, made even better by the fact that it pushed me over the 100% funding mark.

And finally...

The internet is a fickle beast. Once I knew I was going to reach my funding goal after that big article, I noticed that the peak died down really quickly.

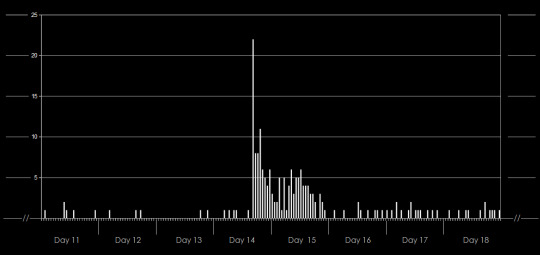

The easily-available data about Kickstarter campaigns is normally only broken down on a daily basis. I wanted to dig a bit deeper and look at the hour-by-hour pledges after being featured in Gizmodo.

I pulled out the timings of pledges based on when I received an email notification about each one, and this is what I came up with.

Pledges per hour before and after the Gizmodo article

Earlier I showed my daily pledge data and the peaks on day 14 and 15 are clear at that resolution, but when you see the pledges per hour it’s incredible how sharp the peak is and how quickly it dies down.

Day 15′s pledges also came via other articles that directly sourced the Gizmodo one, so the effect was momentarily amplified.

The transient nature of the boost to my fortunes was very clear, and it surprised me. Basically, once you slip down below the fold, you pretty quickly disappear into the noise.

Nevertheless, days 14 and 15 of my second campaign accounted for just over a quarter of all pledges, so I’m very grateful for my moment on the front page.

I learnt a few things from my first campaign that I applied to the second. There were also some differences which were out of my control.

So although I was probably better prepared the second time around, running a Kickstarter campaign still required sustained effort and a bit of luck.

I hope to do a third, and maybe more, and I’ll look forward to seeing how they go.

0 notes

Photo

Never unplug the wrong plug again. Back #TheStickerProject live on #Kickstarter now! #tech #lifehacks #crowdfunding http://thndr.me/0tHetP

0 notes

Text

How many spinning tops do you own?

Kickstarter is a strange beast. I follow the crowdfunding platform fairly closely, as a project creator and a backer, but would never pretend that I understand its dynamics.

I mostly keep an eye on Design and Technology projects, and for anyone who frequents those parts of the site, you'll quickly start to notice some popular types of product showing up time and again.

The law of Kickstarter states that at any one time there must be projects for:

A minimalist pen

Tiny multi-tools

Anything to do with coffee

Headphones

Anything made of titanium

I can kind of see why those neat little gadgets are popular on the site, but one thing that surprised me was the number of spinning tops on there. And I'm not talking about some clever modern tech that reinvents the spinning top. These are just round things that spin.

People can't get enough of them it seems. In just over two years, 33 spinning top projects on Kickstarter have together raised over 1.4 million dollars in funding. Over half of that money has been raised by a single team at Foreverspin, who are currently running their third campaign.

Incidentally, my search only returned three spinning top projects that failed to raise their funding. A 90% success rate for a whole product category seems pretty damn good.

What's going on here? In some ways it's ridiculous that so many of the same types of product keep featuring on Kickstarter, and I must admit I'm getting a bit bored of watch campaigns, but in my view this is exactly what Kickstarter is for. People clearly want spinning tops, so let the people have spinning tops. Perhaps the traditional makers of spinning tops thought they were old-fashioned and no one wanted them anymore. Or perhaps, sadly, those type of companies have gone out of business because kids are playing Grand Theft Auto instead.

These are the opportunities crowdfunding platforms have opened up. We all have different tastes, but online you realise that plenty of people do share the same desires and values.

If you've come up with an idea, and perhaps a few friends also think it's cool, you could definitely be on to something. You don't need to be stocked in Tesco and sell a million, but if you can reach a few hundred or a thousand people via Kickstarter you will at least have an incredibly satisfying experience, and it might even be the start of a real, sustainable business.

If spinning tops can teach us anything, it’s that it’s a big wide world out there, and what seems at first like a small niche may actually be a big opportunity.

I’m sure there’s plenty of room in the market for an even smaller key-ring bottle opener. So what are you waiting for?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Does your granny always tell you that the old songs are the best?

This Slade lyric got me wondering. It does seem that there aren’t many great new Christmas songs these days.

I’m a big fan of The Darkness’s 2003 release of Christmas Time (Don't Let The Bells End) but other than that couldn’t think of many others.

Christmas songs from the 80s seem to be popular, but is that a bias caused by my age?

So I decided to delve a little deeper.

The dataset is somewhat arbitrary, but I found a list of 50 top Christmas songs played since 2010 (according to rights body PRS for Music) and looked at the vintage of the songs.

Here are the results.

Top 50 Christmas songs by release year.

So yes, perhaps my initial suspicion has some foundation - only six of the 50 were released in the 90s and later.

Before that, the 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s are well represented. Indeed, 1984 was a massively successful year for Christmas songs - with a full 10% of the 50 songs.

So, there you have it, that’s a graph I’m sure you’ve all been waiting for.

Maybe they just don’t make them like they used to? Maybe TV talent contests have killed Christmas songs?

If anyone has any ideas about what’s going on here I’d love to know.

I’ll still be up and rock and rollin' with the rest though.

0 notes

Text

Amateur Social Media Marketing. Part 2

So I'm almost two weeks into a Kickstarter campaign for my Ockham Razor and, needless to say, I've been spending more time on social media than I usually do. If the numbers are anything to go by, my Ockham Razor persona is far more popular than the real me.

I still don't feel much closer to understanding the dynamics of social media though. It's a funny old world, where a lot of people seem to have too much time on their hands. Or they get a robot to tweet for them, and then it all becomes a bit surreal. Even Stephen Fry has planned for his Twitter presence to continue during his voluntary sabbatical from the service.

As I pointed out last time, there isn't necessarily a correlation between getting fans and followers on social media and Kickstarter success. And as I also noticed, Facebook seems to drive more traffic than Twitter. Twitter is so easy though, and you can make tweets automatically show up in your Facebook feed. However, the lazy option is rarely the best, and I don't think Twitter is an exception.

Going Viral

I think a lot of people have an over-inflated sense of the power of internet. Ridiculous 'stories', like the debate over the colour of a dress, 'go viral' and it feels like everyone can have their minute of internet fame. But this is a poor reflection of reality and an example of a cognitive error caused by survivorship bias.

I recently had the opportunity to observe, in real time, the underwhelming impotence of Twitter. A lady called Kath tweeted at will.i.am during the final of TV talent show, the Voice. He re-tweeted it, which is kind of cool because he has 13.1 million followers. That's the stuff social media dreams are made of isn't it? After half an hour or so it had been re-tweeted 18 times and been favourited 100 times. Those numbers haven't changed since. Kath had 63 followers at the time of tweeting. She now has 71.

In short, pretty much nothing happened. The internet in general, and social media in particular, is very ephemeral. It's hard to make a noticeable and lasting ripple.

Strategy

So to get the word out about my Kickstarter campaign I've decided not to put too much energy into trying to make my own ripples. (Except within my own immediate and existing pond of friends, who have been inundated with spammy waves of Kickstarter-related updates.) Rather, I've tried to get onto the radar of the captains of much larger vessels (how much further can this metaphor go?).

Instead of tweeting and updating Facebook every ten minutes to my handful of followers, I am spending time messaging bloggers and websites that cover men's style, products, and design. This is a laborious process because it takes a while to research each individual or publication to make sure I target my pitch as best I can. I don't think a big group email would get me very far. I also hope that there is a sort of gearing effect whereby smaller blogs can be easier to approach, but potentially punch above their weight in terms of influence in a certain sphere. Pitching to the New York Times straight off the bat seems unlikely to be successful.

After some initial features in smaller blogs, and even my local paper, my approach yielded some larger fruit and I got very lucky. Last Thursday the Ockham Razor was featured on uncrate.com. That had a significant effect as clearly seen here.

Daily backers via Kicktraq.com

The day after that, we became a 'Staff Pick' on Kickstarter and the daily backers have been quite steady since then.

Keep pushing

The first couple of weeks seem to have gone OK with my Kickstarter project, although I have no frame of reference having never done it before. We're very far from home and dry though. This could be an uncomfortable read in a month's time.

Social media has definitely helped to spread the word about the Ockham Razor, but I don't think my own social media efforts have directly lead to many new backers. If a man tweets in the woods and nobody reads it, does it have any affect?

One thing about the internet I know for sure though, is that any idiot can say whatever they want and publish it online. Q.E.D.

0 notes

Text

Social Media Marketing Part 1 (no one can accuse me of link baiting)

Less than a week away from a Kickstarter launch, social media marketing is on my mind.

It's all anyone really talks about when you're trying to raise awareness for a new product. Gone are the days when you would post a printed press release to the local newspaper .1

Online media is obviously a natural place to publicise an online product launch. Not least because there's an immediate and actionable message to convey: 'Click here to back my product. Right now.’ Conversely, how often have you seen something interesting in a magazine, made a mental note to follow it up, and then never have?

The beauty of the internet is that you can probably find a blogger, who despite having a tiny fraction of the readership of more traditional media, writes about exactly the kind of thing you're selling, and you therefore have a massively greater chance of reaching people who give a shit about what you’re doing.

Build a following!

Get Twitter followers they said. It's all about likes on Facebook. Easy, right?

It's damn hard work if you ask me. Maybe I don't have a natural affinity to social media in the way some people do. The dynamics of it all truly baffle me sometimes. Maybe it's because I'm old enough to have normally-developed thumbs.

I got my first email address in 1998 just before I went to university when Mark Zuckerberg was 14 years old. When I got to university my department had a 'computer room' and the only people who had computers at home were computer science students. I was in my mid twenties before Facebook, and then Twitter, came along.

I'm not trying to make excuses. Just saying...

Kickstarter

So when it comes to publicizing a Kickstarter campaign, it seems obvious that social media is a big deal.

Before diving in and aimlessly trying to build up a following for my Ockham Razor I thought I'd look at what others had done. I wanted to look into the correlation between measurable social media variables and Kickstarter success.

I decided to look at the top 20 grossing Kickstarter campaigns and their Twitter, Facebook and Instagram followings. These 20 projects raised an average of $2.3 from an average of 15,000 backers. 2

Observations

Interestingly, I couldn't even find social media accounts for some of these multimillion-raising projects. For one of them I couldn't find a Twitter account; for three, no Facebook page and for almost half I couldn't find an Instagram account. Maybe I didn't look hard enough: let me know if you can find something for Bibliotheca for example, who raised $1.4 million last year.

I also noticed that some campaigns had relatively established companies behind them, and therefore existing fans. Lomography for example has two projects in the top 20 so I thought the data might be a bit skewed for them and not so relevant to me.

I'm not going to go crazy with graphs, but here's one showing the number of Kickstarter backers vs Twitter followers. (I removed the two Lomograph projects, and another couple of outliers to make the scale clearer.)

I haven't done any proper statistical analysis on my data but that certainly doesn't look like a positive correlation to me. Facebook likes had a similar scatter and Instagram looked even more like a negative correlation.

So what's going on here then? Is this saying that social media is irrelevant if you want to do well on Kickstarter?

Firstly, 20 is not a great sample size so I should be careful not to read to much into this data. Ignoring correlations with Kickstarter, there were some other interesting insights such as the fact that the average number of Facebook likes was ten times the average number of Twitter followers.

This favouring of Facebook is in line with something else I've noticed anecdotally. When looking at design and style blogs as I've been doing my research, I often see that articles are shared on Facebook a lot more than on Twitter. This may just be the kind of websites I've been visiting but they are my target audience so I should probably pay attention to that.

Generally, it does feel that Facebook is a more 'deliberate' place to be and that interest and engagement is likely to be better. There seems to be a lot more noise on Twitter and therefore less chance of being heard. It seems full of 'online marketing experts' with 18.2k followers, who almost certainly won't help your cause.

Another point is that people can share your content without necessarily following or liking you.

So, what now?

If I can take anything away from my armchair statistical analysis it is perhaps that I should make more effort with Facebook over Twitter. Although reaching out to key influential bloggers directly is probably more rewarding than both of those.

Getting President Obama, Justin Bieber and Stephen Fry to tweet about your product will probably help, but if the product is rubbish you'll eventually sink. If you build something great you have a much better chance of success. Take Kraftwerk for example who raised over $1.5 million dollars and they still only have 220 Twitter followers. Maybe people are just getting mixed up with the other Kraftwerk.

The internet has profoundly opened up opportunities for innovation. However, the recipe for success must still come down to making something that people want and telling people about it. Social media can help with the second half of that, but it's not magic.

I will end it here and, for a moment, overcome my English sensibilities about self-publicity.

Visit the Ockham Razor website!

Like us on Facebook!

Follow us on Twitter!

(in that order)

Or, even better, if you're an award-winning men's style journalist, please do get in touch.

______________

This post is also published on the Ockham Razor website.

Notes

1 Do look out for a piece on the Ockham Razor in the Islington Gazette next week though!

2 In hindsight it might have been more interesting to look at less well funded successful projects rather than those who raise millions, but I think this data is still interesting. It's also worth noting that I only looked at present-day social media stats rather than historical data that aligns with the running of the Kickstarter campaign, but again I think these still provide some insight.

0 notes

Text

The real 3D printing revolution will not be televised

[Originally posted on the Ockham Razor Company blog here.]

Everyone's heard of 3D printing these days. There probably hasn't been a Wired issue for about five years that doesn't mention it. A lot of publicity goes to the quirky products and art projects that use 3D printing and if I'm being cynical I would suggest that some people use 3D printing just as a way to make their projects seem more interesting.

I'm glad people have crazy ideas and do silly things with it, but for me the incredible power of 3D printing goes way deeper than that. As I've now experienced first hand, 3D printing has become an indispensable tool in the armoury of makers. Without it, the Ockham Razor Company may never have got off the back of the proverbial napkin.

The basics

3D printing has become a catch-all term for all sorts of processes that produce three-dimensional objects from various standardized raw materials such as plastic, metal or even chocolate. However, the term 3D printing was originally specific to the technique of depositing layer upon layer of solid material, in the way an inkjet printer puts down ink, to create a 3D object.

MakerBot Replicator

Perhaps the most familiar image we have of 3D printing is of hot plastic being squirted from a nozzle by a machine like a MakerBot which is using the technology of fused deposition modelling. For now though, I'll stick with using the term 3D printing in its broadest sense.

Compared with more traditional manufacturing techniques, 3D printing typically has lower set-up costs and faster turnarounds. Take moulded plastic for example - something we're all familiar with in the form of LEGO bricks or toy soldiers. These are made in enormous quantities and although it costs thousands of dollars to set up the machines to make each part, that works out quite well when you're making millions of the same LEGO brick. And since plastic is cheap it ends up costing almost nothing to make each LEGO brick. To make a one-off LEGO brick in the same way would cost thousands of dollars.

By contrast, if for whatever reason you wanted to make a unique piece of LEGO then to 3D print it would cost, say, a dollar. If you wanted to make a million of your newly-designed LEGO bricks like that, it would cost you a million dollars. You get the point.

Almost ten years ago, when I first came across 3D printing in a professional sense, we created parts to test the design of small components and in some cases we would make custom parts for users which special requirements. The material used was ABS plastic (which is what LEGO bricks are made from) so it's pretty tough stuff.

So although these techniques were initially associated with industrial rapid prototyping they are increasingly being used to make finished products. In high-end manufacturing 3D printing is becoming a viable way of making complex, critical components. The world of medicine too has seen plenty of inspirational applications of 3D printing because every patient is different and it's a great way of making parts to fit exactly for a particular individual, be it a hearing aid or a prosthetic limb.

3D printed razor

For our project we have used fused deposition modelling to make plastic prototype razors. The material we've been using is PLA, a bioplastic made from renewable resources which is a great way to try and reduce the environmental impact of prototyping.

Prototype razor

We would have really struggled without the ability to make prototypes in this way. It's very hard to appreciate what something is going to be like by looking at a computer screen and, although our razor is a relatively simple product, getting the shape exactly right is critical to the success of the design. To iterate our design in this way costs us a day and a few dollars for a new version; to iterate once we get to full production in metal will cost us weeks and hundreds of dollars.

As the technology evolves, so do the innovative services around it. For our project we're taking advantage of 3D Hubs, a great service which connects you with local 3D printers. It means we can find a place down the road to get exactly the right kind of 3D printing done for exactly what we need at the time. Via 3D Hubs we have access to the latest and greatest 3D printing technology and sound advice from passionate people operating their 3D printing hub, at a relatively low unit cost. All without having to buy our own expensive equipment, which would sit idle most of the time anyway.

The future?

In my view the consumer revolution in 3D printing has been somewhat over-hyped. I find it hard to imagine everyone having a 3D printer in their home anytime soon, a vision often presented to us, mostly by 3D printer manufacturers I suppose.

People aren't going to be sitting at home dreaming up new kitchen utensils or toys for their children and printing them out. The main reason for that is that designing three dimensional objects is difficult. How many people do you know whom you'd want to design your wallpaper? Designing in two dimensions is not trivial. Designing in three is way harder. The lack of a quick way to produce solid objects at home isn't the limiting factor here.

Teleportation

I think there are two things that will increase the usefulness of 3D printing for consumer applications in the fairly near future.

The first is to improve access to 3D-printable designs via services such as Thingiverse. These online markets are starting to become places where you can find genuinely useful things but there's still a large quantity of gimmickry and tat. Looking forward, perhaps manufacturers will start to supply 3D-printable files for spare parts along with a warranty subscription or something.

The second really interesting area is 3D scanning. Imagine being able to photocopy three dimensional objects. Combine a 3D printer and a 3D scanner and that's pretty much what you've got. Separate the scanner and the printer and you're not far off teleportation!

While I'm sure we'll keep hearing about 3D printed hot dogs and other frivolous 3D printed projects, I believe that 3D printing is a great enabler and a powerful force for good, which is already quietly making a difference.

Ideas are cheap but execution is hard. If 3D printing makes execution just that little bit easier that means more ideas will become reality. And that is a good thing.

0 notes

Text

Show me the way to Amarillo

Diving on American roads I've seen a lot of useless signs. I wouldn't necessarily mind this, but there has also been a distinct lack of useful signage on the highways.

This is exemplified by the many Adopt-A-Highway signs on the roadside. I don't have a problem with the concept – it's a clever way to keep roads maintained via private sponsorship rather than tax dollars – but as a driver I'd rather know how far it is to the next city or that the lane I'm in is about to disappear. Maybe they should get local companies to sponsor more practical things like distance markers and speed limit signs. It can get quite distracting because I can't help but read every sign I see. Learning that a particular junction is the “State Trooper Dwight H. Frankenfurter Jr Memorial intersection” is not a good use of my mental bandwidth whilst travelling along at 70 mph.

Plenty of useful road signs can also provide mild amusement as they direct towards place names like Boring, Oregon.

Another roadside phenomenon in the US is the Historical Marker. These Historical Markers are very well-made metal plaques nicely mounted in wood or stone and typically there will be a couple of signs up the road announcing their imminent appearance. When you get there, the plaques invariably display a dry, albeit beautifully laid-out, list of historical dates and names relating to an obscure event that happened somewhere near the point. This information is always written in a tiny font, which is impossible to read without stopping and getting out of your car. Quite frankly though, they are not worth stopping for. That's if you even can stop to read them - half the time they are on the side of a busy main road with no safe place to stop so you can't even read them. Perhaps the idea is to mark down their position to return in the dead of night with a torch.

The Historical Marker is just one example of the American love of plaques.

Museum entrances bristle with plaques. From a distance they seem grand and erudite. But when you get close enough, you realise it's just a list of all the building contractors who constructed the “Maureen and Henry Scheitz North Atrium Extension” in 2004. And then other plaques displaying the names of the people who funded the project from the many “Bronze donors” up to the “Platinum Heroes of America” contributors who donated a million dollars or more. Again, I don't mind this self-congratulatory adulation, but when it comes at the expense of good honest useful exhibit information it's kind of annoying.

Built only a few years ago, there is a new bridge above the Hoover dam on the border between Arizona and Nevada. (It's called the Mike O'Callaghan–Pat Tillman Memorial Bridge.) It's a marvel of civil engineering. It's not only a beautiful span, but using it knocks hours of the journey between the two states. You can walk across it on a purpose-built walkway safely separated from the speeding traffic of Interstate 93. As you do, there is a plaque every ten metres or so which outlines the process of building the bridge in great detail from the financial methodology during the commissioning stage to the exact techniques of construction. If more proof were needed that unnecessary commemorative metal signage is an endemic problem in America, one of these plaques actually showed a Gantt chart. Project managers rejoice!

I don't mean to sound mean-spirited here. I actually quite admire the idea of the hyperbolic celebration that these signs and plaques embody. It perhaps says something about the effort and unwavering optimism that built America. In Barstow, California, the town's water tower is proudly emblazoned with “BARSTOW - HOME OF THE 5-TIME STATE CHAMPIONS. DIV III CROSS COUNTRY”.

Cross country may not be the most popular sport in America, but California is a big state so I imagine division three is pretty tough. They aren't even reigning champions (a list of championship-winning years was listed below), but this goes to show that there's always something outstanding or superlative to shout about if you look hard enough. The town of Barstow is clearly proud of their achievement, and why not. Don't hide your light under a bushel – celebrate small victories. And if you feel inspired to turn your pride into a plaque, then who am I to judge.

0 notes

Text

American mapanomalies

I probably look at maps more often than most people. In the last couple of months I've been spending a lot of time examining maps of America in particular.

Generally, I think maps are amazing things. Primarily they are practical tools, crafted with incredible skill - especially back before the existence of satellites. More than that, as soon as a three dimensional physical world is presented in two dimensions, the political, economic and ideological biases of the creator are evident. There can be no such thing as absolute reality in a map. However accurate, by accident or design, I find maps beautiful things.

But I digress – I didn't mean to get carried away declaring my love for cartography. As I said, I've been looking at American maps a lot recently: mostly our Rand McNally road atlas, Google maps, and the excellent official state maps picked up for free at state welcome centres.

For no particular reason I was looking at the south west corner of Kentucky the other day.

How strange to have a part of the state completely orphaned like that. I suppose it came about by the movement of the Mississippi river over time - recalling my school study of ox-bow lakes, etc. If anyone can shed any light on it then please do let me know. Incidentally, this small section of map shows some good examples of the great variety of, often unimaginative, place names in America: Moscow, New Madrid, a town called State Line.

Then I got to looking at other parts of the USA for interesting quirks. One of the most obvious things that struck me, as an old-worlder, was the straight lines. Colorado is exactly a rectangle! New Mexico's north east corner is almost square but not quite...

For comparison, I had a quick look at England and I couldn't see a single straight county border – invariably they follow a river or some other natural feature. North America's greater size and more aggressive carving-up meant that ruler-straight borders were a practical necessity. The most obvious of which are the great lengths of boundary between the USA and Canada.

This crude method of land division inevitably leads to oddities. Look at this part of the border between Canada and Minnesota where a small part of American land is cut off from the rest of the country.

Apparently this was just an administrative oversight. Similarly, there is a small population of Washington state residents who have to send their children to high school via Canada every day. The very funny and informative CGP Grey has a great video about this.

Occasionally, driving across a state line coincides with a change in time zone, which is novel for an Englishman, but otherwise, as an outsider at least, state boundaries don't really mean anything. Signs may change slightly, as do number plates, taxes and laws, but as long as you avoid any trouble with the police (presumably), you have unimpeded access to almost ten million square kilometres of some of the most incredible geography on the planet.

Mostly I've been looking at maps to work out how the best course between interesting places. Sometimes though, seeing a feature on a map may be the reason for going there; be it an interestingly named town such as Grandview, or just the improbable Interstate 12 in North Carolina.

Tools like Google maps have undoubtedly made a massive difference to travelling these days – knowing which of seven highway lanes through Los Angeles to be in is a wonderful thing. But there are still enormous areas of the country with no mobile internet coverage so paper maps still have their place. And they never run out of battery.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Grandview, Texas

Terri and I have been on the road in the US for a couple of months now. It's been one hell of a trip so far. America has not let us down in terms of interesting places, people and experiences. Part by luck and part by judgement, the journey has provided an even and steady succession of attractions.

Driving between Monument Valley in Utah and the Grand Canyon in Arizona the other day I realised that between all the significant places of interest there have invariably been large stretches of relative nothingness. While a little tedious, these gaps do serve to ensure that arrival at each new attraction is a suitably dramatic and momentous event.

It does take a deliberate effort to intersperse the tedium with significant places of interest. As Bill Bryson points out in The Lost Continent it is now possible, by sticking to Interstate roads, to drive across the whole of the USA without seeing anything.

Seeking a break from an interminable Texan highway in a particularly large buffer of tedium a few weeks ago, we picked a random town to get some coffee and fuel. With not much to go on we chose a place with the enticing name of Grandview (Pop. 1325).

To be honest, I was ready for an anticlimactic view and that's what we got. The town however, was a delightful surprise. It was a small place centred on a road junction and a railroad crossing.

The brick buildings had a certain charm about them despite the evidence of better days past. There was an old local bank, an auto-repair shop, an obligatory Freemasons centre, and even a few picture-postcard beat-up trucks and faded signs scattered around.

As we've found with many places in America there weren't many people out and about, but behind closed doors you never know what you might find.

In this case we stumbled across a small coffee shop called The Grind. We were immediately struck by how thoughtfully done the interior was. Apart from the bible quotations on the wall, it wouldn't have been out of place in Shoreditch or the Lower East Side.

The owner was wonderful and we got the whole story of how her and her husband had set the place up wanting a change from city life and how the building used to be a funeral parlour.

The biggest surprise was yet to come. As we were chatting after ordering coffee she happened to mention that it was a shame we hadn't asked for an ice-cream. We were intrigued and it turned out that the ice-cream was made from the family's grandmother's old recipe and frozen with nitrogen. We had to have some. After a great deal of noise, clouds of gas, some milk and cookies, the ice-cream materialized before us and I can honestly say it was some of the best ice-cream I've ever had.

In many ways, coming across places like this by accident is more rewarding than the top-billing attractions like the Grand Canyon or the Statue of Liberty. It makes you wonder how many similarly brilliant but less obvious experiences one misses along the way.

I can't even remember now which two planned destinations Grandview was between. I'm sure though that there was enough road between there and the next stop to make sure our eventual arrival was another great moment on our trip.

0 notes

Text

Razor rant redux

After my public statement of disappointment with the razor industry I decided to put my hands where my mouth is (or some other appropriate mixed metaphor).

So I made my own razor handle. This is a hacky first prototype but I'm going to start using it and see how it goes.

I'd love to hear what you think about it so please get in touch with me if you have anything to say. I may even be looking for beta test users sometime soon...

0 notes

Text

Why are some products just crap?

I've noticed that some categories of product have a much greater tendency to be ugly than others. It's as if there's only a certain amount of aesthetic to go round and some things have to lose out. Two unfortunate examples of such losers are razors and Hi-Fis.

Turbo power kapow! razors

By razors I mean wet-shave razors with a handle and replaceable heads. You'll spot these because they are typically advertised alongside sportsmen, motorbikes and explosions.

Personally, I find shaving quite a tranquil experience - first thing in the morning sound-tracked by the Today programme on Radio 4. It's not a time when I want to be shouted at by an over-engineered, nuclear-powered piece of colourful metal and plastic

Gillette Fusion Power Gamer (that really is what it's called)

Successive generations of product managers and marketers universally and reliably seem to have decided that all the experience has been lacking is an extra blade? Perhaps I'm being unfair because planned obsolescence is a key factor and by that measure they are doing a great job, but either way it leaves me unsatisfied.

Wilkinson Sword Royale by Kenneth Grange, 1979

It's not impossible to design a good-looking razor. The great Kenneth Grange has designed some for Wilkinson Sword in the past, but in my opinion today's popular models lack a certain class.

Next time you're in the supermarket have a look at the choice for yourself. Maybe it's just me but I find it disappointing. And that's before you get home and have to tackle the life-threateningly sharp plastic packaging. Is this really the best a man can get?

Hi-Fis

I realise that there may be a declining market for hi-fi equipment, but their ugliness is not a new development. Indeed, these days aesthetics are arguably all the more important now that the competition is more diversified.

To make my point, see what you think of the £1,000 Cyrus CD player. Or this Parasound Halo CD1 for £5,000. Yes, that's five thousand pounds. Really.

Parasound Halo CD1

Who even listens to CDs these days, you may ask.

This phenomenon isn't restricted to ancient technologies such as CD players. Cutting-edge and critically-acclaimed models are also being dragged through the design hedge backwards.

Take the award-winning Naim UnitiLite for £2,000 or the Krell Connect, a £3,000 audio streaming box.

Krell Connect

Again, counterexamples prove that there isn't a fundamental law of acoustic engineering that limits beauty. There has been some great looking design from Dieter Rams and Braun over the years, combining form and function in perfect harmony the way they do. More recent examples exist too - like this from Yamaha.

Yamaha A-S2000

Of course, as with the razors, this is very subjective. I could find ugly examples of all sorts of products. But with hi-fi equipment ugliness seems to be endemic, and there's an inverse correlation between price and much I'd want the product on display in my living room . See for yourself – here are What Hi-FI magazine's top-end CD player reviews.

By the way, I think proper stereo systems are great and I still listen to CDs. It saddens me to think that a generation of kids may grow up only listening to music on YouTube and mobile phones.

Bling watches

I'm sure there are other classes of products sitting in design blind spots but razors and stereos have rankled me for a while. I wouldn't automatically put watches in this category because there are many lovely watches out there. But many incredibly expensive watches do corroborate my argument that money doesn't necessarily buy taste.

Watches are quite tightly constrained in terms of size and form factor. Perhaps this is why, to justify the ridiculous prices desired by people with more money than sense, watchmakers contrive to produce some truly hideous watches by adding and adding and adding.

This watch will set you back nearly £100,000. That in itself is obscene, but based on looks alone I would genuinely pay a small monthly fee to not wear it.

Obscenely expensive watch by DeWitt

There are many more where that came from. Again, you can judge for yourself via this link to some watches from Harrods that are the price of a car, or even a small house.

Beards

There's great pleasure to be had in beautiful products - even a £5 razor. I wish companies would stop over-complicating things and focus on making simple, usable products.

Maybe ugly razors are the reason why so many designers have beards.

0 notes