Photo

Riding the South turned 2 today!

0 notes

Text

Jenny makes peace with F150

By Jenny Morris Moving Daughter No. 1 to Iowa over Labor Day weekend became an exercise in endurance for Scott. And that didn’t even include all the driving he got to do.

We took the F150. A good decision as far as packing volume was concerned, but a bad one in that we had never traveled in it a long distance until this trip. Honestly, I had begun to think we bought this truck to ferry Scott, friend Wayne and their bicycles all over north Alabama. Yet when talk of the logistics of moving Daughter No. 1 from Cincinnati to Des Moines, Iowa, commenced, the comment Scott made second in frequency to “You know the trip will be 27-plus hours of driving going the speed limit” was “We’re taking the F150.” Incidentally, he made the comment on the driving hours at least 31 times. He said we were taking the truck once. As I figured he was driving, I didn’t respond. Perhaps I should qualify: I didn’t say anything about taking the F150 before we left for Cincinnati. I said plenty when we were in it and on the road. Years ago, in a moment of what I thought was touching early marriage honesty, I told Scott, “I don’t like change.” It must not have been that early, because Scott just stared back at me, mentally counted to 10 and said, “I know.” The F150 is a far cry from the Toyota Highlander we usually take on trips. I compare the 8-year-old Highlander’s ride to butter, smooth and sweet. The F150 rides like a truck. In addition, the F150 has no foot room for the nest I like to construct for long trips. Typical items I need within reaching distance are my computer, the cord to charge my computer, DVDs to watch on my computer, textbooks to read ahead for the ever-coming next lecture, three pairs of glasses, my purse, snacks ... That’s the short list. But really, I have to bring something along to amuse myself while Scott drives 27-plus hours. Combine the limited foot room of the F150 and its riding discomfort with a little hobby my ankles picked up sometime in the last decade. They swell to twice their normal size whenever a seat is just a bit too high for my feet to comfortably rest on the floorboards. Did I mention the seat height of the F150? Not to you, maybe, but rest assured Scott’s heard about it. On day five of our jaunt, about the time we started passing Confederate flags in southern Tennessee, I told Scott my final assessment of the F150, and that this was my final ride in it for any lengthy trip. Then I abandoned my post at shotgun to wait out the final hours home from the back seat. And there I learned my place in life, or at least my place in the F150. A woman whose feet won’t comfortably reach the floor in its front seat can stretch out with room to spare in the back. And when Scott’s annoying girlfriend — that voice on the GPS that he will follow anywhere — told him to detour through eight miles of winding county roads, I slept through it all. So, take the F150 on our next visit to Iowa? Sure, just let me grab my pillow.

0 notes

Text

Fishing in heaven

By Scott Morris

We marked the years by fishing trips.

Remember that time a storm almost capsized us on Lake Watauga? We were catching slab crappie by lantern light when the storm blew over the Appalachians. The swells slapped the boat as you opened up the old Johnson outboard and headed for the dock.

Remember that time we were chest deep in the surf at Fort Morgan, pulling in speckled trout and bluefish, and the dark shadow of a huge bull shark torpedoed between us? Man, we got out of there in a hurry.

Remember that time snow blanketed the dock at Smith Lake? I slid off the pier and disappeared into the abyss. You looked amused when I shot out of that cold water like a bullet. I went back to the truck to strip off the wet clothes and put on a dry snowmobile suit. Then we had a good laugh and went fishing.

I can’t remember the first time you took me on the water, but an old black and white photo shows us in a boat on a trailer, me just a baby, you in your straw hat. Fishing was like breathing or eating or going to church on Sunday morning.

During the week, you wore blue herringbone overalls and supervised a team of second-shift workers in the hot and noisy confines of a copper-tubing factory. But you reserved Saturdays for fishing. You thrived on fresh air, cloudless skies, green trees, clear water, rocky shorelines and a peace that passes understanding.

Nothing could keep you off the local lakes and rivers, and it seemed your endurance and longevity would carry on forever. But you eventually outlived your ability to negotiate a launch ramp. You sold your boat. You gave me your rods, reels and tackle boxes.

“Maybe you’ll start fishing again some day,” you told me.

At the funeral, I thought about your 93 years, your quiet and gentle ways, your mischievous streak. And I thought about the great love of the outdoors you instilled in me.

I wonder what you’re doing now. Walking the streets of gold? Taking in an angelic concert? Watching a cork bob up and down on Paradise Lake?

Remember that cool day during spring break when you ran the boat up Rock Creek as far as it would go? The current flowed fast and clear as we anchored under dogwoods that bloomed white against the Alabama sky. For hours, we caught plump bass as fast as we could reel. We smiled and laughed — our best day ever — on a creek somewhere between here and the hereafter.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pedaling through Faulkner’s South

By Scott Morris

As I Lay Dying of a leg cramp, I cursed William Faulkner’s great-grandfather.

If Col. William Clark Falkner — who dropped the “u” from his name — had not developed a railroad through central Mississippi, I would not be lying in a tiny tent suffering leg cramps after cycling all day on a rails-to-trails.

The Tanglefoot Trail — from New Albany to Houston, Mississippi — is a paved bike path that follows the legendary colonel’s Gulf and Ship Island Railroad. My plan was to ride 120 miles over three days by combining the trail with the Natchez Trace Parkway.

After a grilled turkey and cheese sandwich with french-fried potatoes at Bankhead Bicycle Club in downtown New Albany, I set out on my journey through Faulkner’s South, loaded down with tent, sleeping bag, food and other gear.

The Tanglefoot Trail is easier to follow than a Faulkner narrative. Like almost all rails-to-trails, it is mostly flat and straight, which is good when you and your rig are pushing 275 pounds. (I won’t break down the weight by rider, bike and cargo.)

The 44-mile narrow ribbon of smooth asphalt carries riders over scenic creeks, through a thick canopy of trees, past open farmland and the occasional kudzu jungle. Riding an abandoned railroad line into the towns of New Albany, Ecru, Pontotoc, Algoma, New Houlka and Houston is probably not much different than it was in past centuries. The bike glides between the backyards of humble cottages, warehouses and factories.

On the first day, I pedaled south to New Houlka, and then traveled four miles of rough pavement on a county road to Davis Lake Recreation Area in Tombigbee National Forest. The modern campground beside the lake was nice, so I decided to make it my base camp for two nights.

With the first 40 miles out of the way, I woke up the next morning with plans to ride a loop on my second day, incorporating the Natchez Trace, the southern leg of the Tanglefoot Trail and back to Davis Lake.

The Trace is hilly in this region, and proved a challenge with the extra weight of a touring bike. But I eventually rode into Houston and had lunch before getting back on the Tanglefoot and returning to the campground.

My wakeup call on the third morning came from songbirds, Canada geese and woodpeckers. Soon, I was packed up and back on the bike for the final leg back to New Albany.

The folks in the Magnolia State have done a fine job with the paved bicycle trail with well-maintained restrooms and water fountains. It gives the feeling of wild country while being never more than a few miles from civilization.

Mississippi is a state full of ghosts, both good and bad. As the towns and villages go past, you know Faulkner was right. “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

0 notes

Text

Ghost of Meriwether Lewis

Dave Tullie and Pat Meaux are ready to get back on the Natchez Trace Parkway.

Our sleeping accommodations await as the sun sets over the campground off the Natchez Trace at Hohenwald, Tenn.

My makeshift touring rig made with a mountain bike, $13 rack, kayaking dry bag, handlebar-mounted daypack and plenty of bungee cords.

By Scott Morris When it comes to adventure, bicycle tourists are not exactly Lewis and Clark. But the spirit of our nation’s most celebrated expedition carries on along the Natchez Trace Parkway when a fully loaded bicycle glides past the ivory blooms of wild dogwoods. I set out recently to experience a hundred miles of that spirit on a two-day trip. Rather than solitude on the open road, however, I made three new friends whose definition of adventure far exceeds my own. My plan was simple and inexpensive. I installed slick road tires on my old mountain bike and attached a rear cargo rack, purchased for $13 at the local Sears going-out-of-business sale. I packed as light as possible, with a one-man tent, an inflatable sleeping pad, a thin blanket, a half loaf of French bread, peanut butter and four energy bars. A fine collection of bungee cords completed the Beverly Hillbillies appearance of my makeshift touring machine. From Alabama, I pedaled north toward Meriwether Lewis Campground at Hohenwald, Tennessee. It didn’t take long to realize that moving a loaded mountain bike across the hilly terrain would be tough and slow. I settled into a steady rhythm, and relied on low gearing and perseverance. Soon, I met up with another northbound cyclist, who had started in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and was averaging 100 miles a day. Phil Dundas, a native of Australia and now resident of New York, has seen the world from the leather saddle of his touring bicycle. He was kind enough to slow to my pace and share a fine spring afternoon as our wheels spun toward the same overnight destination. Phil’s stories of adventures in Central America, Europe and Central Asia helped me forget about aching calves and hamstrings. We stopped for water and snacks at the Hasti-Mart in Collinwood, where we ran into Dave Tullier and Pat Meaux. These tough senior citizens were riding about 85 miles a day toward the northern terminus of the Trace near Nashville. As the sun sank low, Phil and I coaxed our beasts of burdens up the final hill to the campground and pitched our tents. Dave and Pat arrived later to claim the adjacent campsite. We ate dinner and talked of bicycles and gear, of adventures, of jobs, of wives and children, and children to be. Bedtime arrives early on a bicycle tour. We said our goodnights and retired to the extra-firm sleeping accommodations that await tent campers. We dozed off to sleep to the mournful cry of a whippoorwill in the same woods where the senior officer of the Lewis and Clark Expedition died in 1809. It was just three years after his 8,000-mile journey through the west. Lewis — 35 and serving as governor of the Louisiana Territory — was shot twice on an October night while staying at Grinder’s Inn. Most historians believe he killed himself, although theories persist that he was murdered, or assassinated. More than 200 years after his death, we awoke to a new day. We ate breakfast, packed up and pedaled out of the campground. Pat was cycling on to Alaska. Dave had a rental car waiting at Franklin, Tennessee, to take him back to Louisiana. Phil was debating whether to ride another 340 miles to St. Louis, or board a plane in Nashville and fly home. I headed back south toward Alabama, motivated by the prospects of a hot shower and a luxurious mattress. We left Meriwether Lewis behind. But his ghost rode on beside us.

Phil Dundas at Meriwether Lewis Campground.

The Natchez Trace Parkway is alive with spring colors.

The gravesite of Meriwether Lewis, senior officer of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

0 notes

Text

Eagle has landed on Shoal Creek

By Scott Morris The annual lesson in successful parenting — as presented by a pair of American bald eagles — is underway high over Shoal Creek. As soon as one eagle lands, the mate takes flight to stretch its wings and find a fish in the swift current below. The nesting parent lends its warmth to the incubating eggs until the other eagle returns. I have been watching this display in tag-team parenting for three years on Shoal Creek, just north of Iron City, Tennessee. One thing that always surprises me is the size of the massive nest. Eagle nests average 4-5 feet across and 2-4 feet deep, according to the National Eagle Center. The birds add new material every year. Here are a few other eagle facts from National Geographic:

The name of our national bird comes from the old English word ‘balde,” which means white.

Males and females look alike, but the female is larger.

Their bodies can be 3 feet long and their wingspan 8 feet wide.

Eagles can soar more than 10,000 feet.

They can locate a fish up to a mile away.

They can dive bomb at over 100 mph to catch a fish.

They can live 35 years or longer in the wild.

If you want to experience the lesson in bald-eagle parenting on Shoal Creek, launch your canoe or kayak on Factory Creek at the bridge on Hardin Loop, north of Iron City. Factory Creek flows into Shoal Creek after about a mile. About 30 minutes into the trip, you will start passing houses on the bank to the right as you approach a long point in the river. The nest is on the left before the point. If you visit soon, you may see a hungry eaglet peeking over the edge of the nest, waiting impatiently for the next meal.

See more eagle photos.

0 notes

Text

Lost and found on ghostly river

The Wolf River in southwest Tennessee features Ghost River Canoe Trail.

Spirit Lake seems to go on forever in every direction.

By Scott Morris

Forget about a landmark. We couldn’t find land.

We were beginning to think we wouldn’t get out by dark if we didn’t locate the canoe trail markers that we had somehow lost.

But no matter which way we searched, we saw nothing but a watery forest of bald cypress and water tupelo, which seemed to stretch for miles around us.

Finally, friend Wayne Williams and I backtracked to the general location of the last 3-by-6-inch blue trail signs we had seen. Several anxious moments passed before we relocated the trail and started paddling again.

We were floating the Wolf River in southwest Tennessee. This scenic stream offers a wilderness adventure through the swampy floodplains that empty into the Mississippi River.

The Wolf River originates as artesian springs in northern Mississippi before flowing 90 miles west to Mud Island in Memphis.

We chose the 8.5-mile section of Wolf River that passes through Ghost River State Natural Area, the most popular segment. We parked the truck at the river take-out near LaGrange, Tennessee, and paid $10 each to Ghost River Outfitters for shuttle service to the upstream launch point.

The day was unlike any other river trip I have ever experienced. Rather than dropping over rocky ledges into deep clear pools like creeks in the Tennessee Valley, the murky Wolf River twists and turns through narrow passageways lined with dense cypress groves.

Other than the blue trail markers, few signs of human encroachment mar the view. It’s easy to imagine the red wolves, black bears, mountain lions and woodland bison that still inhabited the region when French trappers and the Chickasaw roamed the river basin.

The trip began with a fast-moving current through a well-defined river channel and continued this way for the first three miles. Heeding the advice of our shuttle van driver, we stopped for lunch near the end of this section so we could get out of the kayaks and stretch our legs. The driver warned there would be no place to stop downstream past here.

Soon after getting back underway, we spotted the sign marking the narrow entrance to Ghost River State Natural Area. The Ghost is an eerie, deepwater swamp.

Eventually the river pours into Spirit Lake, which looks like a miniature Reelfoot Lake. This is where we got lost several times because we could not find the blue canoe markers. Spirit Lake is also where the trip becomes more strenuous for about 45 minutes because there is no current to propel a boat.

Thankfully, the fastest flowing current on the Wolf River is just downstream of Spirit Lake, and it is a blast. Paddlers must negotiate many narrow, sharp turns between cypress trees as the increased flow quickly sweeps their canoes and kayaks downstream.

After four hours, including 30 minutes for lunch, we arrived at the take-out. Tired? Yes, but ready to get lost again on the Wolf River.

For more information, see Wolf River Conservancy.

0 notes

Text

All talk and no paddle

A member of Huntsville Canoe Club gets ready to paddle Brushy Creek.

Running the String of Beads.

Two paddlers take a winter swim below Sougahoagdee Falls.

By Scott Morris

If those who can do, and those who can’t talk about it, count me in the latter group when it comes to paddling Brushy Creek in Alabama.

As the drought of 2016 lingers into the new year, there isn’t enough water rolling out of the canyons of Bankhead National Forest to float a boat. So, I have to be content talking about one of my favorite trips down Brushy Creek with a few guys from Huntsville Canoe Club.

When we made our trip Jan. 28, 2012, the creek was churning. Although the U.S. Geological Survey has no gauge on Brushy Creek, the USGS reading at nearby Sipsey River was over 600 cubic feet per second. That compares to less than 50 CFS most of the time this winter, although recent rains have improved the levels.

Brushy is Sipsey’s little brother. I think it’s more scenic with its narrow canyon walls, numerous tributary waterfalls and banks lined with hemlocks and mountain laurel. In the winter and spring, these parallel creeks transform from crystal clear into a luminescent green.

The float down Brushy begins with a chore. You have to paddle across Brushy Lake, then portage around the dam and down the steep bank. Generally, if there is enough water to float over the rapids directly below the dam, there is enough to paddle the rest of the creek.

We stopped about three miles downstream from the dam and hiked up a tributary on the left to Coal Mine Branch Falls. Two of our guys tested their waterproof drysuits by swimming in the deep pool below the falls.

Although Brushy Creek is tame by whitewater standards, it does hold a little excitement immediately downstream from the convergence of Coal Mine Branch. The creek pours into a narrow passageway called the String of Beads, with boulders serving as the charms of the necklace.

Mile 6 features one of my favorite spots in Bankhead forest. The small tributary on the right leads to the great Sougahoagdee Falls. A recessed rock shelter here allows hikers to walk behind the falls and peer out into the mouth of the canyon.

Rush Creek enters Brushy Creek about a mile downstream from Sougahoagdee. The Brushy Creek take-out awaits on Forest Service Road 255, or Hickory Grove Road. Including the side hikes and a stop for lunch, our trip lasted about 4.5 hours.

When the water is too low to make this trip, I have launched at the usual take-out and paddled down to U.S. 278. This lower stretch is scenic, but it requires a couple miles of flat water on Smith Lake.

Hopefully, the rains will return and raise the water levels in Bankhead National Forest. But, for now, there isn’t enough water to do, so I have to be content to talk about it.

0 notes

Text

Rainy day on Rockpile Trail

A pair of white pelicans ply the waters below Wilson Dam, just off the historic Rockpile Trail in Muscle Shoals, Alabama.

After months of drought, recent rains are restocking Pond Spring, which flows into the Tennessee River.

Autumn leaves are hanging on into December.

The rocks are smiling back.

The veins of a fallen leaf reflect the symmetry of nature.

Given a chance, nature will recapture ground lost to human development, as proven on the Tennessee Valley Authority's Muscle Shoals Reservation. The Rockpile Trail begins on an abandoned railroad that transported goods for the construction of Wilson Dam. The path traverses the ruins of an early 1900s coal-fired steam plan, which was built during World War I to support a munitions plant. The Rockpile Trail and several intersecting paths also travel past Civil War earthworks, Civilian Conservation Corps structures from the Great Depression, small wildlife area and an old double-decker bridge that carried automobiles on one level and trains on another level. The reservation features 17 miles of paved and primitive trails.

0 notes

Text

Fall survives drought on Brushy Creek loop

By Scott Morris

The 2016 version of fall may be brown and brittle, but autumn colors are peeking out along the remote roads around Brushy Lake.

The hues in Bankhead National Forest always seem more vivid than the valleys below and this holds true even in an exceptional drought.

I have been hungry for a return to the forest this fall, but the weather has been too warm to run the copperheads and rattlesnakes into hibernation, so mountain biking held more appeal than hiking.

A friend and I charted a 14-mile route starting at the old log Pine Torch Church, south of Moulton. Our journey, which traversed both gravel and paved roads, included Brushy Creek Road, Leola Road, Owl Creek Road and Mount Olive Road. It required two big climbs, but otherwise followed the mildly rolling ridge tops.

Our fast and winding descent to Brushy Lake was exhilarating. The recreation area brought back memories of childhood trips here. Back then, my cousins and I explored the lakeside trails both below and above the cliffs, and we usually played football in a flat, grassy area while the adults prepared lunch.

During the current year of lean rainfall, the lake has retreated to the main channel of Brushy Creek. Rather than pouring over the stair-step concrete dam, the water is low and stagnant, waiting more patiently than the rest of us for drought relief.

My friend Wayne and I rested along the banks and ate a snack, soaking in the sunshine and deep blue skies. Then, it was back on the pedals for a remedial course in bicycle karma, which demands a difficult climb after an easy downhill run.

We topped the hill at Pine Torch Church relieved — as we always are — to actually arrive back where we intended to be.

Map of Brushy Creek Loop

0 notes

Text

Insider’s guide to Baptist church

Recently, a religious comment to one of our Yankee-born children was met with a blank stare.

Realizing she might find herself in a room full of Southern Baptists one day, we felt the need to compile this short list of Baptist terms. We draw on our experiences of being raised in the denomination and attending Baptist colleges to offer this Insider’s Guide to Southern Baptist Terminology:

The Transfiguration: When the heavenly light shone down upon Donald Trump and transformed him from the lesser of two evils into our Lord and Savior.

Backslider: A Baptist who misses two consecutive Sundays without a doctor’s excuse. The appropriate greeting for a backslider is “we missed you on Sunday,” which is loosely interpreted as “where the hell have you been?”

Prayer request: the latest gossip shared discreetly with the entire congregation during Wednesday night prayer meeting and published in the church newsletter in case anyone missed it the first time

Long-winded preacher: a Baptist minister who can pack 15 minutes of sermon into an hour

Foreign mission field: where the heathens live

Lord’s Supper: Holy sacrament requiring unleavened oyster crackers and Welch’s grape juice from the Walmart served in plastic shot glasses from the Baptist book store

Seven deadly sins: drinking, dancing, smoking, mixed bathing, fishing on Sunday, cussing and Obamacare.

Integration: mixing donations from different denominations to be sold at the communitywide thrift store

Separation of church and state: when the pastor tells the congregation which candidates that God wants them to vote against on Election Day

Hell: a four-hour, Wednesday-night business meeting

Inclusivity: a diversity movement that welcomes a rainbow of football fans — even supporters of Tennessee and LSU — into the body of Christ. Does not extend to misguided fans of non-SEC teams

Men’s Sunday: a special service devoted to the contributions of men to the church (celebrated 52 times a year)

Stand your ground: the best way to survive a deacons’ meeting

Holy Trinity: the Fox News, the Sean Hannity and the Donald Trump

Song director: a part-time church employee whose love of music is matched only by his love of talking

Sex: done once in the backseat of a car before marriage, but rarely practiced after the wedding

Inerrant word of God: a resolution passed by a majority of delegates at the annual convention

Climate change: when different members of the congregation keep adjusting the thermostat up or down because they can’t agree on a temperature

Greed: the only sin you’ll never be pressured to sign a petition against

Beer: an alcoholic beverage best purchased with cash late at night in another county while wearing dark sunglasses and a hat in case you run into another Baptist

Trunk or treat: an annual event in which children dress up in costumes and get candy as a godly alternative to the evil celebration called Halloween in which children dress up in costumes and get candy

Extended altar call: singing all six verses of “Just As I Am” for the 12th time

Wednesday night supper: church-sanctioned gluttony

The Devil: the antagonist who sits on a tack in a popular children’s song

Moving your letter: when you R-U-N-N-O-F-T from one Baptist church to join another one

Liberal: a Prius-driving Democrat who thinks the New Testament packs more firepower than the Second Amendment

Women’s Missionary Union: a sign of intelligent life

Tribulation: what the congregation experiences when the preacher tries to explain “Revelations”

Once saved, always saved: a lifetime get-out-of-hell-free card.

0 notes

Text

Fun begins when pavement ends

By Scott Morris

Yes, it’s a strange obsession.

I pour over Google maps and spend rainy weekends driving back roads in search of the Holy Grail of bicycle routes.

Our little corner of northwest Alabama, south Tennessee and northeast Mississippi holds many hidden gems. Some of my favorites: a loop off the Natchez Trace Parkway to Lutz; a ride that traverses the Freedom Hills Wildlife Management Area; and a challenging climbfest through the peaks above Waterloo.

In the past year, however, the idea of extending rides beyond the pavement has multiplied the scenic options.

A new movement in the world of bicycling involves a category of machines called gravel bikes. These are set up similar to road bikes with drop handlebars, but have wider tires and tougher construction to tackle gravel roads and hard-packed trails.

I’m not in the market for a gravel bike. My dear wife has placed a moratorium on more trucks or bicycles at our house. That’s OK. My old mountain bike fits the niche.

Last winter, I used it to combine the dirt roads of Key Cave National Wildlife Refuge with adjacent paved roads for scenic routes that would be off limits to a fragile road bike. More recently, friend Wayne and I pieced together the Richard Martin Trail — a gravel Rails-to-Trails pathway in Limestone County, Alabama — with paved roads through the Elk River Valley in south Tennessee.

The alternatives in this valley — which encompasses Athens, Elkmont, Pulaski, Prospect and Elkton — are almost limitless. And the goat cheese sandwiches at Belle Chevre in Elkmont add a tasty bonus.

If the Holy Grail of bicycle routes requires sprawling farmland, hardwood-covered hills and little to no commercial development, the quest to find it is getting closer.

1 note

·

View note

Text

File Halloween under cattywampus

By Scott Morris

While it may appear a ghoulish glowing jack-o-lantern is haunting The Resident Cat, the truth is that we are exploiting the poor feline to announce we’ve categorized the Riding the South archives into a more manageable menu.

We’ll file the entry you are reading under Cattywampus, the official category for the weird and the wild.

The other new categories of blog entries are:

Yonder — for outdoor and travel features

Conniption — for when Jenny gets worked up about something

Mercy — for when we are rejoicing in or losing our religion

Kin — for the family stuff

As we announced a few weeks ago, we took a few weeks off to rework Riding the South to make it easier to find past features.

During our first year, we offered two new blog posts each week. We are reducing the workload for the time being to whenever the spirit strikes.

We hope you enjoy the slightly new look and forgive us for exploiting The Resident Cat.

For more, see Riding the South.

0 notes

Text

All the stories we didn’t tell

By Jenny Morris

A year ago, Scott turned to me and said, “Let’s start a blog”— or something like that.

As I agreed to his suggestion, my only stipulation was that we actually populated the blog with content — no anemic once-a-quarter postings and no illustrations copied from the Internet.

Within a few weeks, we had fallen into a twice-weekly writing routine. Our goal was to post 104 entries in one year’s time. And I suddenly understood a staple Scott lived with daily in his life as a newsprint journalist: the pressures of a deadline. A self-imposed deadline, as Scott often pointed out, but still a deadline.

This post marks our 104th entry to our blog. We’ve had fun sharing the challenges and humor of our past year with readers. We thrilled to “likes” on our Facebook page (who doesn’t want to be liked?) and moaned when something we wrote (usually I was the culprit) was misunderstood.

Some posts were easy to write and almost cathartic. Who can’t relate to the woes of car ownership? To twist the old saw: can’t live with ‘em and it’s counterproductive to shoot ‘em.

Or the frustrations of parenting six children. See comment on cars above.

Other posts surprised us. We grew up in a South crawling away from the noxious gas of racism. How did we reconcile our love for the South, blighted heritage and all, and our hate for some of its practices? And how did we write about it for all our friends to see?

And believe it or not, there are plenty of stories we didn’t tell. But you won’t hear them any time soon.

We’re taking some time off from blogging for the next few weeks to organize our website. Far from anemic, our blog can be overwhelming for a first-time visitor confronted with a sprawling list of past blog titles. We want to classify our posts in categories.

So, for example, if you want to find a nature hike Scott recommends, complete with “if you go” information, you can click on that section of the blog and not have to remember its title.

We’ll still post from time to time. (Friday night at a high school football game I made notes on all the ways we’ve failed Child No. 6 as parents. The finished product will probably make the blog soon.) And we’ve paid for our website through 2018. So we’re still at scottandjennymorris.com if you want to come by for a visit.

If you can’t find us, come back some other time. We’re probably just off-line cleaning up the place.

0 notes

Text

Can a dog predict weather?

By Scott Morris

One of novelist Clyde Edgerton’s more memorable Southern characters is a bulldog named Trouble.

In “Where Trouble Sleeps,” the people of Listre, North Carolina, can determine the weather forecast by the spot where Trouble decides to snooze. For example, if he naps inside his owner’s store, expect rain.

Although Trouble’s meteorology skills may be extraordinary, dogs are an integral part of the retail sector in the South. Their ranks vary from snarling junkyard Doberman to friendly Labradoodle greeter.

The proprietor at Werner’s Trading Co. in Cullman, Alabama, appreciates the skills of a good canine. The official store dog, Mazzie, was famous locally for greeting customers, when she wasn’t napping at the shopkeeper’s desk or the cash register.

Sadly, Mazzie died earlier this year. But her memory endures through her own page on the store’s website.

Presently, my favorite retail canines are the two outside pups that welcome bicycle riders, farmers, cotton-gin workers and diners to the Oakland Café, a rural gas station/restaurant. When you’re hot and exhausted — and don’t think you can keep going — the Oakland dogs are there to encourage you with wagging tails and wide grins. They also gladly accept tips in the form of snacks purchased from the store.

We bicycle riders have a love-hate relationship with dogs. Pets that are allowed to run loose are a hazard. Most are not vicious, but the wheel chasers can cause crashes and serious injuries. So, if you own a dog, please keep it confined to your yard. Or better yet, buy a store and put the mutt to work.

Dogs can provide all types of valuable services in a retail setting. But can they really predict the weather?

For cost and accuracy, I’d say they’re a better value than a TV meteorologist.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hummingbirds of Rock Spring

By Scott Morris

The annual migration of ruby-throated hummingbirds and butterflies is underway at a special little spot off the Natchez Trace Parkway in northwest Alabama. The Rock Spring Trail, an easy 20-minute loop along Colbert Creek and a spring-fed tributary, takes visitors into a colorful jungle of lush plants and flowers. The abundance of orange jewelweed attracts hundreds of the humming migrants as they make their way south. My camera skills were not good enough to capture an image of the tiny birds on a recent trip as they flitted from bloom to bloom and buzzed past my head. Maybe next time. This is not the sort of attraction you would drive hours to see, but if you're traveling the Natchez Trace in September, or visiting Tom's Wall, take a few minutes to walk the Rock Spring Trail and witness the hummingbird migration. The trail is off the trace west of Florence between Lauderdale County roads 2 and 14. To visit the commemorative Native American wall, continue north on the trace and turn right on Lauderdale County 8. The wall is about a block on the right.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Kid lands a job — and likes it!

By Jenny Morris

I have colleagues who dream of hearing the first (or next) grandchild is on the way. And I’ll admit those are exciting words to hear, since we have one beautiful granddaughter and another grandchild on the way.

But, we have also heard other exciting words from five of our six children. (We’re still waiting on Daughter No. 2.)

Yes, “I got a job” sends a parent’s heart throbbing. And even better is when one of them loves the job.

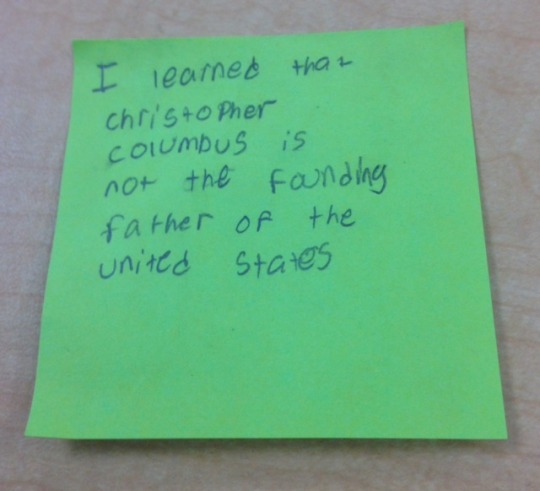

After a rocky first year with Teach for America where Daughter No. 1 was held captive by 28 Guatemalan, Spanish-speaking kindergarteners, she’s transitioned to the front of an eighth-grade history class. Recently she sent us an update on her brave new year.

Reading her letter, I found myself thinking she’s the kind of teacher I wish all children had, and the kind I wish our culture could affirm and keep in the classroom. But enough of my words; here are hers:

“I dream about my students and they are the first thing I think about in the morning,” she wrote. And after commenting that she’s learned many students suffer from undiagnosed mental illness, she continued, “Yep, it’s a circus and I’m the Ringmaster.”

Then she went on: “But I have some wonderful students. I think about Briza and Jennifer (I have three of those — eek!) teaching me Spanish pronunciation: they implied mine wasn't too bad for a white girl. I think about Jevon, who was so excited when he earned enough points for a positive phone call home. I left a voicemail for his dad, and Jevon was beaming. ‘I'm going to get a high five when I get home,’ he said.

“Then there's Mamadou and Rokia, who take assessments individually. I read the questions and they answer them orally. They hardly know any English, but they're trying so hard. I use some French with them, and I'm looking for short French texts about what we're reading to give to them.

“Ariyana can be a trouble-maker but she is the smartest kid in class (well, tied with Mohamed), and ever since she's been taking assessments and given the chance to do school work that is hard for her, I haven't had a problem with her. Eber can't quit smiling about making a perfect score on his quiz. Josue (the brother of one of my students from last year) and Darwin are quiet and smart. Better than that, they work so hard. Josue is precious. When he speaks to me, I can tell he's carefully selecting every word. He was older when he came to the U.S. and will probably never lose the accent, but he's worked so hard at learning English that his written work is beautiful.

“Kenneth is smart and likes to stir up trouble. On Thursday, he got another student yelling about something without me even noticing he'd started it. When I pulled him aside to talk to him, I found out he's an only child. ‘That's the problem!’ I said. ‘You don't have anyone to pick on at home.’ He nodded a bit and wouldn't look me in the eye. Lunch detention and he wasn't a problem Friday.”

As Daughter No. 1 helps her students, many of them first generation, assimilate to American culture, they help her assimilate to the classroom. I can’t help hoping, sometimes, that’s where she’ll stay.

0 notes