Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

[Robespierre the younger] was called the great howler, the national bellower. Desmoulins said: Ducos' least gesture is an epigram, and the very sound of young Robespierre's voice is foolish. Desmoulins said of the opinions put forward by Robespierre the younger in the rostrum that they always came from the throat, never from the head.

Note written by Edme-Bonaventure Courtois, cited in Camille Desmoulins and his wife; passages from the history of the Dantonists founded upon new and hitherto unpublished documents (1878) by Jules Claretie, p. 458.

@le-vieux-cordelier @bonbonrobespierre maybe you two should talk this out?

#DUCOS MENTIONED DUCOS MENTIONED DUCOS MENTIONED DU-#AARRRPFKLDFOPRLRLDFK#I'm not sane anymore#But well kind of believable augustin doesn't give an impression of a deep thinker#Though kind of rude still

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

Let me explain why Madame Pétion hasn’t been in Caen.

She says “I arrived on 26th or 24th”. Of which month?

If June, she could not know the reaction on Marat’s assassination. I will straight away point out the fact that Madame Pétion is not mentioned in Pétion’s memoires, while Buzot writes that his own wife stayed in Bretagne and Louvet says a lot about Lodoïska. Louvet on page 134 (1823 ed.) states that they were travelling to Dinan with “quelques femmes” in addition to Lodoïska*. From Buzot (p.188) we conclude that Madame Pétion was not amongst them. Could she return from Caen to Paris? If it was June there was no sense in it, because Pétion himself was in the city only on 28th (Mancel’s note in Souvenirs du fédéralisme p.208). And how could she reach Caen before him, when in his memoires she possesses no will to leave Paris?

But could she arrive in July? If yes, why would she return to Paris where she would be arrested and not follow her husband? What for would she stay for four or five days in a city where her husband no longer is, in a city where the Constitution is accepted (20th July) and where insurrection is officially, formally, democratically ended by vote (25th July for all the sections but one)?

It may seem for a moment that she could have a reason. Vaultier (author of Souvenirs du fédéralisme) claims that Pétion was in Caen with his son of eight or ten years (p. 72). How plausible it would be to imagine Madame Pétion coming to take her son back left in the city, if not one thing. Pétion had no son with him (see his memoires). The origin of such a mistake is interesting (and the fact that it’s the second time a child is incorrectly defined as Pétion’s may amuse @anotherhumaninthisworld). Yet it’s explainable; Vaultier, a twenty-two year old president of a section, befriended with Barbaroux, had connections with Valady, Girey-Dupré and Duchâtel, but was only introduced to the older deputies. Pétion belonged to those he had seen “from greater distance and on less occasions” (p.64).

Another detail from Madame Pétion answers that must be taken into account is the fact that she had seen Barbaroux’s mother in Évreux. I don’t know exactly when Barbaroux’s mother arrived in Caen, but it was before 24th July, because, according to Louvet’s memoires (p.118-119), the deputies must have departed from Caen either on 20th July or shortly after. The only significant detail she adds to her story ruins all the story.

The way Madame Pétion answers the questions is very provocative. She says what the Committee would be glad to hear – and then give no details. She nearly mokes them. Even the interrogator points to her on the irrationality of her answers "observe that if you had been in Caen when the news about Marat's assassination reached it, you would have been there with your husband and other fugitives. What motive makes you hid it from us?".

I doubt she was forced to; she would have been put in prison even if she had said nothing at all. It could have been a form of a protest – an interesting trace of her character left for us.

*- Buzot's wife, Barbaroux's mother, a woman who "avait aidé" Barbaroux (Buzot, p. 37) and maybe someone else.

Upd. 4th June: @anotherhumaninthisworld shared in this post a letter from Carrier saying that Madame Pétion was arrested in Homfleurs (sic.) together with her son and another woman. If Homfleurs is what Honfleur is now, it's here, and then Madame Pétion was arrested on her way to Caen, which is very sad.

I will now also observe how things happened according to Madame Pétion words.

In Évreux she meets Madame Barbaroux, who says either that the deputies are still in Caen or that they no longer are. If first, Madame Pétion travels there to reunite with her husband, if second, to learn where he had gone. She arrives in Caen and finds out the deputies had left it. The city is still favours them, because it is content with Charlotte Corday deed. It is therefore easy for Madame Pétion to ask where her husband departed to and learn that he headed to Quimper. She might decide that the road is too dangerous to try catch her husband up. She stays in Caen for that several days and, finding it less and less safe for her (Romme and Prier were released on 29th), travels to Honfleur where gets arrested.

The first problem of this story I have already discussed — it's Madame Barbaroux presence in Évreux between 23th and 26th, this is the major evidence against that story. The second is how impossible it was for Madame Pétion to reach Bretagne. The question touches a very subjective ground and cannot be answered. I will only say that Lodoïska reunited with Louvet in Vire.

What do we know about Pétion’s wife? 😯

Sorry for the month delay, anon.

Firstly, I will let her speak for herself.

Vatel T.3 pp.780–782:

Committee of General Security Interrogation of сitizen Lefevre, wife of Pétion, on the fourth of August 1793, year II of the Republic, one and indivisible. Q: When did you arrive in Caen and for how long did you stay there? A: For four or five days, I arrived on 26th or 24th. Q: During your stay in Caen, have you seen that girl Corday? A: No. Q: Have you heard what was said there about her crime? A: Yes. Q: What was the general opinion on it in Caen? A: People were content. Q: Can you name people who were content and did you share their admiration? A: I don't know the names, the opinion was general. What's for mine, it's mine, and I'm not obliged to share it. Q: When the news about Marat's assassination reached Caen, were the fugitives still there? A: I know nothing about it. Q: Do you know if the letter written by the girl Corday to Barbaroux was delivered to him? A: I have no idea. Q: Was the letter talked about in Caen? A: I have no idea. Q: Do you know about any relations between Corday and fugitives, your husband in particular, before their departure from Caen? A: No. Q: I observe that if you had been in Caen when the news about Marat's assassination reached it, you would have been there with your husband and other fugitives. What motive makes you hid it from us? A: I don't have any. ................................................. Q: Where did you stay in Caen? A: In Hôtel d'Angleterre, rue Saint-Jean, according to the testimony of a ten years old boy. Q: Who have you seen in Évreux? A: Madame Vallé and madame [mother of] Barbaroux. Q: Have you seen the wifes of the deputies? A: No. Q: Who have you seen in Caen? A: None. Q: Before your husband's departure did you know about Sicion (sic) plans against the majority of the Convention? A: No. Q: Who you used to see most often in Paris? A: Almost all proscribed, because, as a wife, I received the guests of my husband. Q: The proscribed you are talking about, were they gathering on certain days and hours? A: I don't know their motives. They had several meetings, but I was not admitted to them. Written in the said Committee, signed in confirmation of the answers Lefevre, femme Pétion.

Note: If you still have doubts, madame Pétion haven't been in Caen.

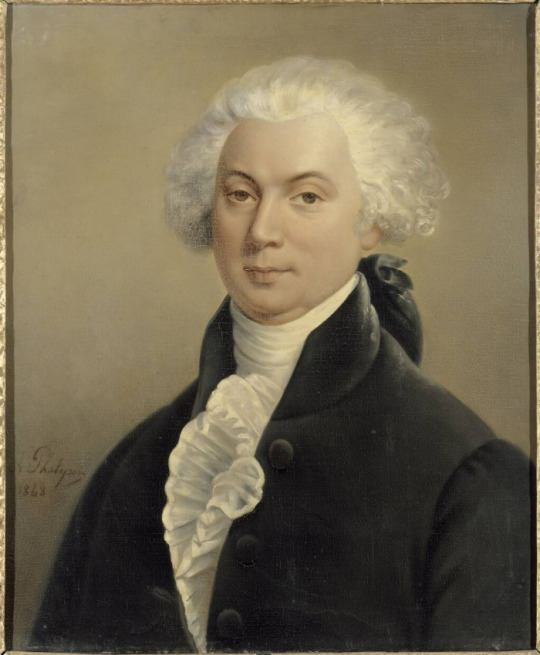

Louise-Anne-Suzanne Le Fèvre (or Lefevre) was born in Chartres (as well as Pétion) in 1760 or 1759.

She was 4'11'' (about 150 cm) tall, had brown hair and eyes, a long face with a long chin and a nose described as big.

She was arrested and put in prison (Sainte-Pélangie) on 9th August 1793 together with her ten years old son Louis-Étienne-Gérôme (1782–1847, Vatel), transfered to Port-Libre (la Bourbe) on 8th Vendémiaire. Since 14th Vendémiaire was in hospitals (due to her sons health problems). Release oreder was signed on 19th Brumaire (Vatel mixes dates here and writes Frimaire), she was free on the same day.

Pétion must have known here fate, because Buzot did (Memoires, J. Guadet version, p.188), most likely from Madame Roland.

From Vatel T.2 p.278

She received an annual pension of 2,000 francs (Vatel T.2 p.271).

Louise-Anne died in 1823 or 1824. She retained an oil on canvas portrait of her husband (I don't know which one), his writings, including his description of travel to England (Vatel T.3 p.513).

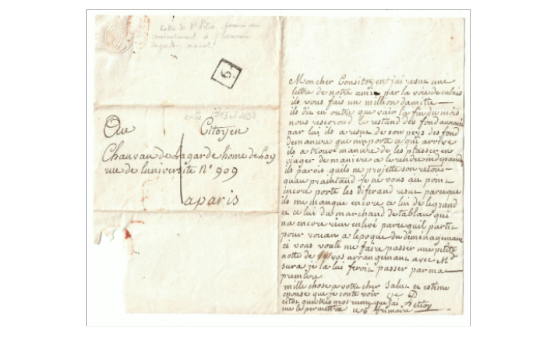

Her handwriting:

Source

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do we know about Pétion’s wife? 😯

Sorry for the month delay, anon.

Firstly, I will let her speak for herself.

Vatel T.3 pp.780–782:

Committee of General Security Interrogation of сitizen Lefevre, wife of Pétion, on the fourth of August 1793, year II of the Republic, one and indivisible. Q: When did you arrive in Caen and for how long did you stay there? A: For four or five days, I arrived on 26th or 24th. Q: During your stay in Caen, have you seen that girl Corday? A: No. Q: Have you heard what was said there about her crime? A: Yes. Q: What was the general opinion on it in Caen? A: People were content. Q: Can you name people who were content and did you share their admiration? A: I don't know the names, the opinion was general. What's for mine, it's mine, and I'm not obliged to share it. Q: When the news about Marat's assassination reached Caen, were the fugitives still there? A: I know nothing about it. Q: Do you know if the letter written by the girl Corday to Barbaroux was delivered to him? A: I have no idea. Q: Was the letter talked about in Caen? A: I have no idea. Q: Do you know about any relations between Corday and fugitives, your husband in particular, before their departure from Caen? A: No. Q: I observe that if you had been in Caen when the news about Marat's assassination reached it, you would have been there with your husband and other fugitives. What motive makes you hid it from us? A: I don't have any. ................................................. Q: Where did you stay in Caen? A: In Hôtel d'Angleterre, rue Saint-Jean, according to the testimony of a ten years old boy. Q: Who have you seen in Évreux? A: Madame Vallé and madame [mother of] Barbaroux. Q: Have you seen the wifes of the deputies? A: No. Q: Who have you seen in Caen? A: None. Q: Before your husband's departure did you know about Sicion (sic) plans against the majority of the Convention? A: No. Q: Who you used to see most often in Paris? A: Almost all proscribed, because, as a wife, I received the guests of my husband. Q: The proscribed you are talking about, were they gathering on certain days and hours? A: I don't know their motives. They had several meetings, but I was not admitted to them. Written in the said Committee, signed in confirmation of the answers Lefevre, femme Pétion.

Note: If you still have doubts, madame Pétion hasn't been in Caen.

Louise-Anne-Suzanne Le Fèvre (or Lefevre) was born in Chartres (as well as Pétion) in 1760 or 1759.

She was 4'11'' (about 150 cm) tall, had brown hair and eyes, a long face with a long chin and a nose described as big.

She was arrested and put in prison (Sainte-Pélangie) on 9th August 1793 together with her ten years old son Louis-Étienne-Gérôme (1782–1847, Vatel), transfered to Port-Libre (la Bourbe) on 8th Vendémiaire. Since 14th Vendémiaire was in hospitals (due to her sons health problems). Release oreder was signed on 19th Brumaire (Vatel mixes dates here and writes Frimaire), she was free on the same day.

Pétion must have known her fate, because Buzot did (Memoires, J. Guadet version, p.188), most likely from Madame Roland.

From Vatel T.2 p.278

She received an annual pension of 2,000 francs (Vatel T.2 p.271).

Louise-Anne died in 1823 or 1824. She retained an oil on canvas portrait of her husband (I don't know which one), his writings, including his description of travel to England (Vatel T.3 p.513).

Her handwriting:

Source

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The colored version is even more sassy (unfortunately it's not lifetime)

Source

Who was plucking this Diva’s eyebrows?! 🫦🥵

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buzot advises Parisians on how to calculate optimal maximum prices

On 18 April 1793, in the National Convention

Buzot: "I must tell a fact worthy for the petitioners to hear. In the city of Bordeaux measures had been taken to maintain the bread prices independently of the wheat ones. The people soon realised that the measure was going to ruin the city, and all the sections voted for the price of bread to be fixed at seven and a half sous per livre (half kg), as the price of wheat damanded. That is the example I propose to the petitioners."

What team do you now play for, François? 🤨

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who was plucking this Diva’s eyebrows?! 🫦🥵

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the terror question is do you rationalise it or not, see if you want to consider it as a method with pros and cons and alternatives in the strict historical circumstances or a phenomenon better not to get to again from any starter point.

Now to my biased opinion (let's pretend the previous point was not). What happened, happened, pros and cons of alternatives can't be fully measured, terror is horrible despite any causes and consequences, because killing people is bad.

“Historians tend to focus on the Terror and attempt to catalogue its victims in Paris and the provinces, but they seldom set beside it the death toll from the war that resulted from the invasion of France, or the potential death toll if the Terror had not enabled the Jacobins to mobilise resistance to that invasion. France defeated, devastated, despoiled and partitioned would have seen a far higher death toll than that produced by the guillotine. The terror of the guillotine is remembered, but the terror of the invading Prussians is forgotten. Nor had the French monarchy and aristocracy been slow to resort to their own terror in the past.”

—

Present historic: Carlyle, Robespierre and the French Revolution

By Ann Talbot

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

Studying the French Revolution is more addicting than anything I have ever tried in my life. I spend all my little free time digging into primary sources and learning everything I can. Even when I should be focusing on my studies, I literally cannot stop thinking about it, its main events and its characters.

I need help.

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

His calmness, his softness, the roses. His non-present gaze above a slight curve of a smile — it's so beautiful. Thank you very very much!

Hello! Can I request Vergniaud with a bouquet of peony roses?

this handsome fellow!!!

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you so much @aedislumen for tagging me

Some wonderful blogs I adore: @lordcastaway @kelvinthegoatt @yuan-ajian @caveintime @grotesquehydra @miffy-junot @fuwbuki @anotherhumaninthisworld @nesiacha @labrador44

❤️🌷SEND THIS TO OTHER BLOGGERS YOU THINK ARE WONDERFUL. KEEP THE GAME GOING 🌷❤️💕

tagging my favs : @ver-lecstappen @ellieisque @adutchlover @lestappen-on-top @starrwrrld @randomwordsonpaper @morecomplicatedthancarbon @sharlsbandana @caprifiles @yappielestappie @chock-and-bates @f1writingbyme

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

“I had a special liaison with Barbaroux; back at the time he wasn’t absorbed by the want to play the role, he was a good youth and loved to learn from me.” Marat, Journal de la République n.15 p. 8

On 23rd October 1792, two were dinking coffee or wine or anything in a café. They were embracing and must have been provoking curiosity, because one was Marat and the other was Barbaroux.

“All good things must come to an end.”

The scene I opened the post with is extracted from “Histoire des Montagnards” by Alphonse Esquiros. Esquiros claims that the source is Albertine herself, how possible it is for her to tell such stories must be better known by @nesiacha and @anotherhumaninthisworld than me. But the way the facts known to me are presented in this book does not inspire great confidence – the work is too theatrical, and the style reminds one of Lamartine. Still the idea, if not the form of the events, is conveyed passable enough for the quote to be used.

From “Histoire des Montagnards” pp. 455-460:

“At that time a chance for a reconciliation between Barbaroux and Montagnards appeared. Danton, Camille Desmoulins and Marat were promenading one evening along a bank of the Seine. They reached C., which was of wine merchant, and dined under the shade of the vine, right at the water’s edge. <…> Marat had become specially attached to Camille Desmoulins and Barbaroux. In Desmoulins a kind character, a spirit, a joyfulness and always good mood attracted him. Contrast is inherent to friendship as much as to love. Camille Desmoulins responded to this tenderness enthusiastically: he publicly called Marat a prophet, a guardian angel, a genius of the Revolution; he wrote about him as of divine Marat in his journal, but their mutual understanding was many times affected by the differences in their characters. <…> What is for Barbaroux, his new relationships with madame Roland and Girondins party did not fail to tear him away from Marat.

“The three: Danton, Desmoulins, Marat used to gather sometimes to their souls be calmed by the peacefulness of nature. <…> Danton ordered the dishes. They agreed not to bring up hot topics during the frugal meal but failed on the dessert. <…> The night fell on the countryside, the three continued their way to Paris. <…> The conversation turned to Barbaroux and Marat said: “Barbaroux was a friend of mine: if the 10th August had not been succeeded, we would have flown to Marseilles together. He was a good youth back then and loved to learn from me. I have the letters written by his hand in which he calls me his master and himself a disciple. If I have lost him, it’s because of Brissotins who stole him from me by their flattery.” Danton, who still cherished the hope to be a link between the Gironde and the Montagne, proposed to arrange a reconciliation. He took Marat to a small café on Rue du Paon, where Barbaroux awaited. Marat remained cold and reserved at first, but Barbaroux made first steps, and they embraced.”

That is what Barbaroux says about Marat, although he is only partly credible here.

From Barbaroux’s Memoires (p. 57):

“I’ve already said in the first part of my Memoires that in 1788 I took an optics course under Marat. I’ve appreciated him as a scholar, I must make him known as a politician.

“One of my writings about the rebellion in Arles fell into his hands, he complimented me and invited to come see him in the apartment opposite Café Richard on Rue Saint-Honoré, where he lived. I came. I recognized my optics master, but when he began to speak, I thought he had lost his mind. He was seriously telling me that the French were petty revolutionaries and only he himself could establish liberty. I wanted to approach the great man, I seemed to be eager for his instructions. He told me: “Give me two hundred Neapolitans armed with draggers and wearing a muff as a shield on the left hand; I will walk through France with them and make the revolution.” All he said after was of the same sort. He wanted to prove me that it was a very humane calculation to kill two hundred and sixty thousand men in a day. No doubt he had a special attraction to this number, because he always wanted two hundred and sixty thousand, rarely reaching three hundred thousand.”

What catches my eye here is “Je voulus pressentir le grand homme, je parus avide de ses instructions.” after the nonsense Marat had told him. After being amazed by Marat once, he once again falls under his spell. These words are sincere. And they are believable from a man who was a real dictator for a month, a role which Marat used to define as the best form of a ruler. The way Barbaroux confesses here is not rare. He also confesses in influencing the elections, simply and with no guilt. It somehow reminds me that Talleyrand’s “Yes, I loved him" about Napoleon. In Barbaroux you can also sense that “in certain circumstances all means are good” – Marat’s doctrine and the way Charlotte Corday legitimizes his murder (the linkage between their ways of thinking is stunningly traced by L. Blanc in his Histoire). Bringing back the Esquiros’ story (not believing it) and filling what is omitted in it, Barbaroux had what Desmoulins couldn’t have – understanding.

Whether it was vanity or something else that connected Barbaroux with the Girondins I will now not discuss.

From Moniteur (26 October 1792 issue):

The scene was played on 24th October. Marat requested the floor and after some bickering with the president Guadet (“Oh! You will listen to me… Against your will.) and several debates of awaiting got it to make a denunciation of Roland and Claviere. He convicted them of empowering an agent, previously spotted, according to the statements Marat brought, to search for counterfeiters. The documents related were read by a secretary, who coincidently turned out to be Barbaroux. Having finished, Barbaroux made his own denunciation.

“I demand that the minister Roland report these facts to the Assembly and I’ll add that the truly guilty one is a perverse man, an agitator who stirs the trouble and discord up in Paris, who runs to the caserns of the battalions of volunteers to deceive them, to try to corrupt them with insinuations and calumnies, to cast a bone between them and the others; and who invites several volunteers to lunch with him to get time and occasion to learn their sentiments, opinions lead them astray.

“Citizens, I will read you the report where all these facts are collected. I was written this morning by the Marseille battalion.”

Marat, firstly greeted very warmly by the volunteers, observed their lodging, listened to the descriptions how they were welcomed by the Commune and noticed, that they are disadvantaged compared to the dragoons of the first regiment consisted of “gardes-du-corps of the ancient regime, valets, coachmen, counterrevolutionaries etc”. While the volunteers admitted the dissatisfaction with their lodgings being fair, they arose against the words about the dragoons and regarded it as an attempt to sow discord between them. They then saw a will to bribe them in the invitation to the lunch and ended up being displeased with Marat.

While the previous confrontations between Barbaroux and Marat were strictly politician, Marseilles were personal. It’s hard to imagine anything that Barbaroux would take to heart more than his – in all meanings – battalions. Marat’s attempt was an act of violation (pardon me for the word), whether it was committed for the purpose described by Marseilles or not.

So, it was the end.

I’m not saying there could be a continuation if not. The very characters of them leave me no such elusion. The breakup was prepared, but it passed painfuly.

And even their shared taste in furs couldn't help

#i couldn't pass by that post about girondin-montagnard breakups yes#no really look at them their furs their cravates one turn of a head like master like disciple#frev#french revolution#girondins#barbaroux#jean paul marat#camille desmoulins#danton#george danton

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Which friendship breakup during the French Revolution between a Girondin and a Montagnard/Jacobin broke your heart the most?

That of Brissot and Desmoulins For more details, see here: https://www.tumblr.com/anotherhumaninthisworld/775038158779875328/how-was-the-relationship-between-brissort-and?source=share

That of Pétion and Robespierre For more details, see here: https://www.tumblr.com/anotherhumaninthisworld/760041507348692992/hi-a-lot-has-already-been-written-about?source=share

Huge thanks to @anotherhumaninthisworld for these two wonderful posts!

The ones that Jean-Nicolas Pache and Gaspard Monge had with Manon Roland before their falling out with the Muse of the Gironde You’ll find some details about their relationships and the eventual rupture in the mini-biography I wrote on Pache:

Part I: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/777295133948411904/jean-nicolas-pache-the-swiss-minister-of-war?source=share

Part II: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/778721992245477376/jean-nicolas-pache-the-swiss-minister-of-war?source=share

Fact I didn’t mention in these post : In her memoirs, Manon Roland wrote that Pache’s children, Jean and Sylvie, sighed for Paris from Switzerland, as they missed the city dearly. (Even if I doubt that’s entirely true—they were still very young when they left Paris—it’s likely they missed their friends more than the city itself and it should be noted that I have noted at least one inconsistency in Manon Roland's memoirs on Pache so all the more reason not to take everything in her memoirs at face value ). Still, this would suggest that either Roland really knew the children, or, despite his famously secretive nature, Pache must have confided in her. Which just shows how close they truly were in my opinion :(

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

all my recent girondin art (but one of these is not like the other)

#GIRONDINS MENTIONED YAAAAAY#Love your art#Buzot is such a city can't stop smiling#And Calonne well good for him hi's here

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

My god I've just seen him live

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camille had also studied with us at the College of Louis-le-Grand… Back then I didn't think he was so bad! He came to see me before the Revolution; he flattered me today, and saturated me tomorrow. He borrowed money from me, and tore me to pieces if I couldn't lend it to him. I have several letters from Camille, in which he gives me many flattering compliments; they are in prose and verse. He had talent, a lot of wit, maybe a good heart; but a very bad head…. The success of my Lunes made him frustrated. When slandering, he only thought to tell me. But, with this phrenesia, we would be sacrificing a whole world of innocent people; and, if it is true that, without having a bad heart, one is, in fact, as wicked and as barbaric as Camille was, then I return to my thesis, and I say that one can be a very dangerous terrorist, without having a bad heart. I do not believe, however, that he was guilty of what he was accused of in order to put him to death, I could not restrain my tears, seeing him pass by on his way to his execution. He had to be reduced to political nullity; but it was not necessary to cut his head off! Let's not cut anyone's head off anymore, if we can!

Testament d’un électeur de Paris (1795) by Louis Abel Beffroy de Reigny, p. 147.

#Writing „Let's not cut anyone's head off anymore if we can“ unironically is actually really blue#And I like this fragment so much#Not because of the last phrase#But Camille is so Camille here#And the mixture of delight disappointment and regret he wakes is so real

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

On April 5, 1794, due to the execution of the Dantonists:

Rest in peace:

Camille Desmoulins, journalist, deputy to the Convention (34 years old) Georges Jacques Danton, deputy to the Convention (34 years old) François Chabot, deputy to the Convention (37 years old) Philippe François Nazaire Fabre, known as "Fabre d’Églantine," deputy to the Convention (43 years old) Jean-François Delacroix (41 years old) Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles, deputy to the Convention (34 years old) Claude Basire, deputy to the Convention (29 years old) Joseph Delaunay, deputy to the Convention (41 years old) Pierre Philippeaux, deputy to the Convention (39 years old) Marc René Marie d’Amarzit de Sahuguet (41 years old) Junius Frey (40 years old) Andrés Maria de Guzman (40 years old) François-Joseph Westermann (42 years old)

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

A short letter from Bonaparte to Carnot

To Director Carnot. I am desperate, my wife will not come, she must have a lover who keeps her in Paris (1). I curse all women, but I give a heartfelt embrace to my good friends. ──────────── (1) Undated letter apparently written in the last days of Prairial Year IV (May 1796). Joséphine eventually joined her husband in Milan, a few days later.

Source: Léonge de Brotonne, Lettres inédites de Napoléon Ier (1898), p. 6

40 notes

·

View notes