Text

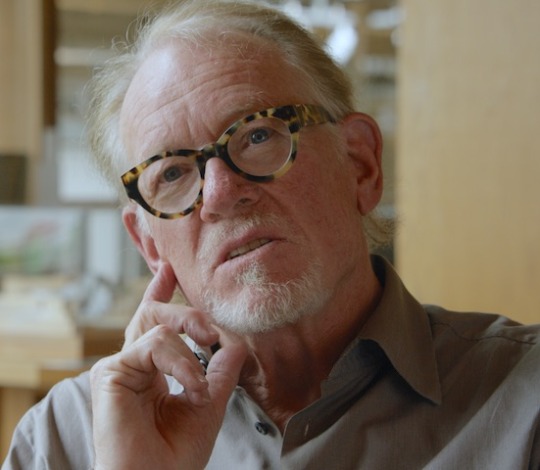

Ruth Reichl

Food Writer/Culinary Editor/Author

Former editor-in-chief, Gourmet magazine

Former restaurant critic for The New York Times/Los Angeles Times

Spencertown, New York

ruthreichl.com

Photo: Michael Singer

SPECIAL GUEST SERIES

In this, our 124th issue of SLICE ANN ARBOR, we are honored to present acclaimed food writer, culinary editor, and author Ruth Reichl. Reichl talks with SLICE about her long and storied career at Gourmet magazine, her passion for memoir writing — and life.

Special to this issue and time, Reichl shares some thoughts about the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. She is currently self-quarantined at her home in Spencertown, New York.

_________________________________________________

INTRODUCTION

Ruth Reichl is a food writer, culinary editor, and the author of five critically acclaimed memoirs: Save Me the Plums: My Gourmet Memoir, For You, Mom. Finally, Garlic and Sapphires: The Secret Life of a Critic in Disguise, Comfort Me with Apples: More Adventures at the Table, and Tender at the Bone: Growing Up at the Table. Reichl served as editor-in-chief of Gourmet magazine from 1999 to 2009. Prior to this, she was a restaurant critic for The New York Times and the food editor and restaurant critic for the Los Angeles Times. Reichl is the recipient of six James Beard Foundation Awards for her journalism, magazine feature writing, and criticism. In 2015, she provided commentary for the Chef's Table (Netflix) series featuring Dan Barber, chef and co-owner of Blue Hill at Stone Barns in Pocantico Hills, New York. Reichl also served as a judge on Top Chef Masters. She is the author of the novel Delicious!, and the cookbooks: My Kitchen Year: 136 Recipes That Saved My Life, and Mmmmm: A Feastiary. Reichl earned a B.A. and an M.A. in art history from the University of Michigan. When she's not working, you can find her cooking, walking, or reading. Reichl resides in upstate New York in a house on top of a mountain with deer, wild turkey, and the occasional bear prowling around outside, with her husband, Michael Singer, a television news producer, and two cats.

FAVORITES

Book: You must be joking! One book? It's usually whatever I'm reading at the moment, which is, right now, Hilary Mantel's The Mirror and the Light.

Destination: Any urban city with good walks and great museums.

Motto: The secret to happiness is finding joy in ordinary things.

Sanctuary: My writing cabin

THE QUERY

Where were you born?

Greenwich Village, New York City

What were some of the passions and pastimes of your early years?

I have loved reading, cooking, and prowling the streets of the city since I was a very small child.

What is your first memory of food as an experience?

I am two. My mother feeds me a spoonful of something so disgusting I cannot swallow it. It is cold and fuzzy on my tongue and if I could have named the flavor I would have compared it to moldy herring. I spit it out. My mother looks surprised, takes a taste of the vile substance and says, ‘What is wrong with you? This is delicious!’ In that moment I understand that my mother cannot be trusted; she and I do not taste the same way. My mother was, in fact, totally taste blind. She had combined the dregs of three different cartons of melted ice cream, poured them into an ice tray, put it in the freezer and left it, uncovered, for weeks to absorb the various flavors of every leftover in the refrigerator. This was her idea of ‘dessert.’ Now, seventy years later, I can still taste it.

What intrigues you most about the art and science of food?

I believe that absolutely everything about food is interesting. The culture of cooking is what distinguishes us from other animals; we cook, they don't. We define ourselves as individuals and as members of society by what we choose to eat. Food brings us together — and sets us apart. And, above all, food is a source of immense happiness.

How would you describe the significance of Gourmet in the history of American culinary culture?

Gourmet was America's first epicurean magazine, and for almost 70 years it chronicled the way Americans were eating. If you want a snapshot of American history from 1941 to 2009, you could do worse than flip through the pages of the magazine. What you see is a country becoming increasingly conscious of the place that food has in our society. I was enormously fortunate to have been given the magazine just as Americans were beginning to understand that food is much more than something to eat, and that an epicurean magazine might offer more than recipes and travel articles. I hope that, at that pivotal moment in our history, Gourmet was able to help steer the national conversation about food to include issues of climate change, ethical eating, farm policy, gender and race — along with all the pleasures of the table.

Was there a period along the way [at the magazine] that presented an especially important learning curve?

For me the seminal moment was publishing David Foster Wallace's essay, Consider the Lobster. When he turned in what was, essentially, a piece about bioethics, I was stunned. It was a beautiful and important piece of writing, but I was also terrified. Were Americans ready to read about the morality of eating animals in a mainstream epicurean publication? As it turned out, they were not only ready, but eager to consider those questions — and it emboldened all of us to tackle the increasingly complicated issues that cooks face every day.

How did you begin to realize your fascination with the art of memoir writing?

I'd been a newspaper journalist for most of my career, and I wanted to see if I could write long. When I thought about what to write, it occurred to me that I wanted to write about growing up at the table — about the many extraordinary people who had influenced my ideas about cooking and eating. I intended it as a group of short stories, but it grew into a memoir. As I was writing I began to see that memoir really was my genre. It's not that I think my own life is so interesting; everyone's life is interesting, but mine is the one I know best. And isn't the point, really, to underline our common humanity?

Do you have a creative process you typically follow as you begin a project?

I wish! All I can say is that I just sit at my desk and wait for it to happen. And then rewrite, rewrite, rewrite.

How do you envision the future of the culinary enterprise?

We're at a turning point right now and the future very much depends on how we go forward. Since the end of World War II, when the American government made food a crucial part of the cold war, our country has been focused on cheap food. The result of these policies — which involved the industrialization of farming, the overuse of antibiotics and fertilizers, the creation of animal confinement facilities, the overfishing of the oceans, I could go on and on — has given us the cheapest and most abundant food in the world. It has also contributed to climate change, the destruction of rural America, the devastation of our waters and a crisis of obesity and diabetes. The result is that six out of 10 Americans suffer from chronic disease. We are only beginning to realize the consequences of the policies of the last 75 years. We can change. My hope is that the generation of young people who have been brought up in a culture of food, a generation who understand that eating is an ethical act, will do their best to undo the damage and create a more sustainable world.

In all your travels, what stands out as the most memorable meal you shared with others?

It was in Crete. I was on my honeymoon, visiting a beloved art professor who taught a course called "Light and Motion." He took us up a mountain for dinner. We came to a tumbledown shack, with a huge pile of onions standing next to it. An old lady came out, set some chairs on the porch, and poured some olive oil into a dish. She picked herbs on the hillside and sprinkled them into the oil. She sliced onions. Set out some olives from her own trees. Gave us a loaf of bread she'd baked, and wine made by her neighbor. Then she picked up a fishing pole and went down the mountain. We drank wine. We ate bread and olive oil. We talked. The sun set. The air was fragrant with thyme. The moon was rising as the old lady returned and lit a fire of grape vines to grill the fish.There were some greens that she'd grown, more onions, and more wine. And for dessert, yogurt from her own sheep. It was a very simple meal. It was perfect. It could only have happened in that place, at that moment. And I realized that the professor had wordlessly made his point: in the right hands, food is art.

Who has had the greatest influence on your life, and why?

My parents. From my mother, who suffered from bipolar disease, I learned to be deeply grateful for my own sanity. And from my father, a book designer who loved what he did, I learned that if you follow your passions there is great joy in work.

Is there a book or film that has changed you?

I read The Grapes of Wrath when I was eight or nine, and it made me think about where our food comes from and all the people who grow it. As a city girl, I hadn't really considered that before. It made me see how much our community depends on food and farming — and it gave me a real desire for social justice for the people who work the land.

What do you consider your greatest life lesson?

Life lesson; it's such an odd concept. One of those words they always use to describe books. Not quite sure how to answer this, but I'll say that the word that I try to live by is generosity. If you always follow your most generous impulses, you can't go wrong. I mean that in every sense: be kind, be available, give away as much as you can. Be there — for your family, your friends, your co-workers. Even when your instinct is to say no, say yes instead.

How would you define a life well lived?

All you can ask, of anyone, is to live up to the best in themselves. Realize your own potential. Work hard, be kind, and have as much fun as you can.

What are you most proud of in your long and storied career?

Sometime in the late 80s I became the food editor of the Los Angeles Times (I was already the restaurant critic). At the time it was the biggest food section in the country with two sections, 60 pages every week. For the next five years, Laurie Ochoa and I reimagined what a newspaper food section could be. We thought of food as culture, not just recipes, and we tried to take as big a bite out of the world as we could. We covered the politics of food, science, agriculture, history, and anthropology. We did profiles. We brought in great people: Jonathan Gold, Charles Perry, Russ Parsons, and David Karp. We encouraged Toni Tipton to stop writing about nutrition and think bigger. We begged writers who'd never written about food to write stories for us. The paper's editor, Shelby Coffey, was skeptical at first, but after a while he said, ‘You've shown me that food can be a great way for a paper to cover the city.’ It was enormous fun. I was really proud of that section, and it ultimately became the template for what we would do with Gourmet magazine.

How would you like to be remembered?

I've been writing about food for fifty years. I hope I had some part in making other people think that it's an important subject. As MFK Fisher said, ‘I cannot count the good people I know who, to my mind, would be even better if they bent their spirits to the study of their own hungers.’

_________________________________________________________

Special to this issue and time, Reichl shares some thoughts about the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. She is currently self-quarantined at her home in Spencertown, New York.

How are you weathering life in the days of COVID-19?

Like everyone else I'm edgy and irritable. As the days go by, it comes closer; people I love have died, others have tested positive. And I know this is only the beginning. At the moment I'm in self-quarantine. I read, I write, I do a lot of cooking.

What are you cooking in your home kitchen?

Fortunately I'm a condiment whore and my pantry is full of wonderful flavor enhancers. My freezer is filled with fruits and vegetables I put up last summer, and I live in the country, surrounded by farms and dairies so meat, milk, and eggs are easy to come by. And since it's just me and Michael, I basically get up every morning and ask, ‘What do you want to eat today?’ And then I make it. Lately it's been a lot of pizza, pasta, and Asian stir-fries. And of course, I'm baking bread. Isn't everyone?

How do you envision the future of the restaurant industry as it tries to rebuild in the months ahead?

I think it's going to be grim; restaurants are very low-margin businesses, and most squeak by in the good times. Many will never reopen. And many that do will become take-out only. That's the down-side. But a remarkable thing has been happening: independent restaurateurs have pulled together in ways they never have before. For the first time they're starting to understand what a huge industry they are part of, and they're using their political clout. Coming on the heels of the me-too movement it means that restaurants will be very different places on the other side of this pandemic. And I think customers will want different restaurants when this is all over. They'll cherish the ability to come together in groups. They'll want to talk, so restaurants will be cozier, quieter, and more comfortable. And I'm pretty sure the ridiculous excesses we've seen lately will vanish; people will want comfort food, not crazy food. And, of course, they'll be more demanding customers because they will all have learned to cook.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maira Kalman

Illustrator/Author/Designer

New York, New York

mairakalman.com

Photo: Rick Meyerowitz

SPECIAL GUEST SERIES

Maira Kalman is a Manhattan based illustrator, author, and designer best known for her New Yorker covers and narrative drawings for The New York Times. She has also written and illustrated 28 children's and adult books. Kalman’s most recent titles include: Swami on Rye: Max in India (2018), Cake (written by Barbara Scott-Goodman, 2018), Beloved Dog (2015), Thomas Jefferson : Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Everything (2014), My Favorite Things (2014), Food Rules: An Eater's Manual (written by Michael Pollan, 2011), The Principles of Uncertainty (2009), and The Illustrated Elements of Style, 2008 (written by William Strunk, Jr. and E. B. White). She published her first children's book Stay Up Late in 1985 to illustrate the lyrics of musician David Byrne.

In 2017, Kalman collaborated with her son, Alex Kalman, to create Sara Berman's Closet, an exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City showcasing her mother's [Sara Berman] life from 1982-2004 when she lived in a small apartment in Greenwich Village.

That same year, Kalman was awarded the AIGA Medal for her work in "storytelling, illustration, and design while pushing the limits of all three.” She has collaborated with Isaac Mizrahi, Kate Spade, and Michael Maharam to design fabrics and accessories, created ballet sets and costumes for the Mark Morris Dance Company and mannequins for Ralph Pucci. Kalman is the recipient of numerous honors from the Art Directors Club, The Society of Publication Designers, and The American Institute for Graphic Arts. In June 2019, Atlanta's High Museum hosted an exhibition exploring her work in The Pursuit of Everything: Maira Kalman's Books for Children. Kalman’s work has also appeared in books published by the Museum of Modern Art and Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum. She is represented by the Julie Saul Gallery in New York City.

When Kalman is not working, you can find her walking around. She resides in Manhattan in a sun-filled apartment with miles of bookshelves.

FAVORITES

Book: In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust

Most valued possession: Books

Motto: Sorry, the rest is unknown.

Destination: A garden anywhere in the world.

THE QUERY

Where were you born?

I was born in Tel Aviv and moved to New York with my family at the age of four. I was raised in Riverdale, the Bronx.

What were some of the passions and pastimes of your early years?

The usual pursuits. Ballet lessons. Piano lessons. Bike riding. Reading. Reading. Reading.

How did you find your style in writing and illustrating children's books?

My style has always been compatible with a child. And my mind as well. There is a whimsy and freedom. An ability to be stupid and smart. And writing for children forces a rigorous editing process. The audience is open minded and the book does not go on too long.

What intrigues you most about the art of illustration/narrative drawing?

It's a good way to tell a story, if you need to tell a story. What compels one to do that is a mystery to me.

How did the concept for Sara Berman's Closet [both exhibition and book] take shape?

We adored my mother. An irreverent, loving woman with a great sense of humor (see her map of the United States). She only wore white. And her closet was a study in perfection. Ironed. Folded. Lined up. When she died, I stood in her closet and thought it should be a museum exhibit. My son, Alex Kalman, fortunately runs a small museum in a defunct elevator shaft in lower Manhattan. It is called MMUSEUMM. We installed the pristine closet there on a grungy alleyway. And then it went to The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

What has been most gratifying about that endeavor?

To know that an idea can be realized in a meaningful way. Not every idea can be real. But this felt so true that it had to be. It may take longer than you imagine. But it can happen.

What led to your collaboration with author Michael Pollan to create illustrations for Food Rules: An Eater's Manual?

Michael and I are friends and we share an editor. His wife thought it would be a nice idea that I illustrated the book. We all agreed, and we are happy we did.

In what ways has your style of storytelling and illustration evolved since entering the profession?

I am a better painter now after all these years. But I am not so sure that is an asset. I speak basically the same way to adults and children. I try to say less. I am as uncertain as I am certain.

What surprised you most about the charge of creating cover illustrations for The New Yorker?

It is thrilling to be asked. And the reach is immense. There is a magical place in the world for these covers. It's good to be part of the history of it all. What you discover is that there is no rule or formula. Each idea is unique. Many ideas do not make it. And there is no way to predict what works and what does not.

Is there a book or project along the way that has presented an important learning curve?

And the Pursuit of Happiness was a great learning experience. When The New York Times sent me on this assignment to write and paint about American democracy and history every month for a year, it was something I had no interest in at all. But it was fascinating and filled me with a greater respect for and interest in history. And I am now definitely more compassionate in general.

What three things can't you live without?

Family. Books. Music.

From where do you draw inspiration these days?

Absolutely everywhere and everything. Walking. Looking at people, dogs, buildings, trees. Music. Film. Reading. Travel. The obits.

Who has had the greatest influence on your life, and why?

My mother, my late husband, and my children. They are the source of meaning and love. And they were and are great fun.

How would you define a life well-lived?

To have work that you love and people that you love.

What one person, dead or living, would you like to have dinner with?

Abraham Lincoln

What's right with the world?

There will always be horrific things happening in the world. That is nothing new. The point is to focus on meaningful things in your life and to do the best you can. Momentous events happen in tiny moments during the day.

What do you consider your greatest life lesson?

There is no one state of being. No destination to a permanent human mood. You can't always be happy. There is happiness and sadness and they inhabit the same space and continue to vie for attention.

How would you like to be remembered?

As a person who had a keen sense of the absurd and sorrow, but kept on going. That is a heroic state in my opinion.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jeff Gordinier

Food & Drinks Editor, Esquire Magazine

Author/Food Journalist

Hudson Valley, New York

jeffgordinier.com

noma.dk

Photo by Andre Baranowski

SPECIAL GUEST SERIES

In this, our 122nd issue of SLICE ANN ARBOR, we are honored to present food journalist and author Jeff Gordinier. Gordinier talks with SLICE about his new book Hungry: Eating, Road-Tripping, and Risking It All with the Greatest Chef in the World — and life.

Jeff Gordinier is the food & drinks editor at Esquire and a contributor to The New York Times, where he was previously a reporter. In his latest book, Hungry: Eating, Road-Tripping, and Risking It All with the Greatest Chef in the World, Gordinier chronicles four years spent traveling in Mexico, Australia, and Denmark with René Redzepi, a Danish chef and the creative force behind Noma, often referred to as the best restaurant in the world. Gordinier provided commentary for an episode of Netflix's Chef's Table series featuring Jeong Kwan, a Buddhist nun in South Korea and an avatar of Asian temple cuisine. His work has appeared in Travel + Leisure, Real Simple, Entertainment Weekly, Details, Elle, Fortune, Creative Nonfiction, Spin, Poetry Foundation, and anthologies such as Best American Nonrequired Reading. A graduate of Princeton University, Gordinier is also the author of X Saves the World and coeditor of Here She Comes Now. When he’s not working, you can find him taking care of his four children. Gordinier lives north of New York City with his wife, Lauren Fonda; they have a view of the Hudson River from their bedroom.

[Jeff Gordinier will be at the Shinola Hotel in Detroit on Tuesday, July 23, 2019, to celebrate the release of Hungry: Eating, Road-Tripping, and Risking It All with the Greatest Chef in the World, where he will be in conversation with chef George Azar, owner of Flowers of Vietnam, Detroit. The discussion will be moderated by Devita Davison, executive director of FoodLab Detroit].

FAVORITES

Book: Impossible to say, but for now, Patti Smith's Just Kids, James Schuyler's Selected Poems, Alexander Chee's How to Write an Autobiographical Novel.

Destination: Anywhere I have never been before, so I will say Japan.

Motto: "I promise I will get back to you."

THE QUERY

How [and when] did the concept for Hungry originally take shape?

When I first met chef René Redzepi, in 2014, I was working as a food writer on staff at The New York Times, and it's safe to say I was wary of the fame he had achieved and skeptical about the New Nordic movement that he had instigated. Redzepi and I wound up traveling through Mexico together for a story I wrote for T Magazine, and that led, over time, to more Noma-oriented encounters and experiences. I soon started spending my own money to check out what Noma was doing in Copenhagen and in Australia, et cetera, and eventually I became intrigued enough that I quit my job to join the circus: I left my post at the Times and began tagging along on the trips that make up the bulk of Hungry. (My gig at Esquire gives me a lot of leeway to travel, and the only way to tell this story was to be free to hop on a plane at a moment's notice.)

For decades I've been a fan of the D.A. Pennebaker documentary Don't Look Back, which captured Bob Dylan at a crucial moment in his career, with all of the friction and frustration that that entails. We're lucky that Pennebaker managed to be present to get footage of Dylan, this pioneering cultural figure, when the singer-songwriter was in the midst of so much pressure and transformation. I guess I hoped to do a similar thing, in a book, with Redzepi — I felt as though I had warts-and-all access to this influential person during a genuine inflection point, and I didn't want those observations to go to waste.

What if, I thought, you were riding alongside Dylan from, say, 1965 to 1968 — from the moment he (controversially) went electric all the way through the recording of Blonde on Blonde and John Wesley Harding? That sort of framework seemed available with Redzepi, because he and the Noma crew were preparing to embark on a series of risky, difficult pop-ups (in Japan, Australia, and Mexico) at the same time that the chef was planning to shut down the restaurant that had made him famous and reopen it in a new form on a site that looked like an abandoned nuclear dump. It was a dramatic set-up - and impossible to resist.

What was your overall vision for the book, before you embarked on the journey?

I had embarked on the journey long before I envisioned it as a book. I was just taking these crazy trips. Along the way I got to thinking that I might have material for a book. The structure of the book came together finally, in my mind, when I realized that it was a cult narrative: Hungry is ultimately the story of a lost man (that would be myself) who found clarity and purpose by joining a cult, only in this case the cult happens to be a restaurant called Noma.

How would you describe the evolution of your relationship with René Redzepi, from day one to the end of the travels?

He talked. I listened. At first I was slightly dubious regarding the whole mission of Noma, but eventually I realized that there was no point in trying to say "no" to this chef. It was more fulfilling to say yes.

What was a typical day like as you worked your way across the globe?

A lot of eating, a lot of driving, a lot of talking, a lot of analyzing. By the end of each day I tended to be exhilarated and exhausted. But I should point out that I didn't perpetually travel with Redzepi for years on end. Most of the time I was simply back home with my family, working on articles, et cetera. And Redzipi was back in Denmark with his family and his restaurant team. We would take these trips now and then, usually on a whim, over the course of about four years.

Who did you meet along the way from the culinary world (or from other worlds) that you'll likely never forget, and why?

Reporting the book was like being stuck in a culinary version of The Canterbury Tales, because famous chefs floated in and out of our orbit as we moved along. David Chang, Kylie Kwong, Danny Bowien, Enrique Olvera, Roberto Solís, Rosio Sánchez, to name but a few. What I won't forget is the summer day when René and Nadine Redzepi held a picnic in their backyard at which some of the world's top chefs got together and cooked: Jacques Pépin, José Andrés, Danny Bowien, Kylie Kwong, Jessica Koslow, Gabriela Cámara. Daniel Patterson, Bo Bech, Alex Atala. That was wild.

Is there a moment that stands out as most remarkable during the journey?

Really it was one remarkable moment after another. That's why I kept going back. It felt like an amplified version of life.

How has Redzepi changed the global culinary dialogue about wild and cultivated sourced ingredients?

Answering that would take a couple of days.

Why did Redzepi "have to do this," a question you asked early in your travels, referring to the closing of Noma in 2015 and its reopening/reinvention in 2018?

Most chefs work hard in a ridiculously challenging environment. Many chefs are perfectionists. But Redzepi is unlike anyone I have written about in the sense that he is never satisfied with sitting still. As readers of Hungry will see, he's allergic to coasting. At this point he and the Noma crew could just keep cranking out the most popular dishes. Customers would continue to beg for tables. But Redzepi seems convinced that his creativity would dry up if he let that happen. So he's always conjuring new challenges — exercises in team-building and flavor-searching that would wear most of us out.

How did this experience ultimately create reinvention in your life; how did it change you?

When I first met Redzepi, I was feeling stuck, which is something that happens to a lot of us, of course. Redzepi's philosophy — his whole approach to living — represents the opposite of stuckness. Like so many intensely creative people (from Bowie to Beyoncé), he's adept at escaping stuckness by propelling himself forward. He doesn't like to dwell on the past; he doesn't like to stay put. When he and I met, I was in a period of my life that was pretty much all about dwelling on the past, and that contrast seemed narratively fruitful to me. (The book starts off by quoting the first lines of Dante's Divine Comedy, which is sort of an inside joke, because from one vantage point the Divine Comedy can be read as an extravagant metaphor for Dante's midlife crisis.) I felt like both Redzepi and I were at pivotal moments in our lives. As readers will see, I wound up getting kicked out of my mental rut.

What is the wisdom of tearing it all down and starting over?

I think what drew me to Redzepi, long before I tasted his cooking, was his crazy commitment to making the most out of his life and the opportunities that have come his way. For those of us (and maybe it's all of us) who toy with the notion of reinventing ourselves, well, Redzepi comes across as a kind of mad avatar of renewal. He has reinvented Noma itself over and over, and he has also, in a way, reinvented Copenhagen, almost single-handedly turning it into one of the most compelling culinary cities in the world. It can be seductive and intoxicating to be around people who have that kind of energy.

What do you think the Danish chef might have learned from you along the way?

I am still much better than he is at making tortillas.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph Becker

Associate Curator of Architecture and Design

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

San Francisco, California

sfmoma.org

Photo by Matthew Millman

SPECIAL GUEST SERIES

Joseph Becker is associate curator of architecture and design at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. He has contributed to over twenty exhibitions at the Museum, including the curation of Tomás Saraceno: Stillness in Motion – Cloud Cities (2016-17), and Field Conditions (2012), as well as the co-curation of Nothing Stable Under Heaven (2018), Typeface to Interface: Graphic Design from the Collection (2016), and Lebbeus Woods, Architect (2013-14). During his 11-year tenure, Joseph has also been responsible for numerous major acquisitions for the Museum’s collection, as well as exhibition design and visual direction of many of its architecture and design exhibitions. He has served on architecture, design, and public art panels; been an invited juror at national architecture programs; led workshops on exhibition and experiential design; moderated public dialogue; and lectured internationally. Joseph earned both a bachelor of architecture and a masters of advanced architectural design (in design theory and critical practice) from the California College of the Arts, where he is currently a visiting professor. When Joseph is not working, you can find him sailing his 1979 Columbia 9.6 on the San Francisco Bay, or working on a slow remodel of his 1948 house in Bernal Heights.

FAVORITES

Book: I really avoid playing favorites, and I love books, so I’ll just say that Reyner Banham’s Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies is always on my list of required reading, both because of my interest in architecture and as a native Angeleno. I don’t have much time to read for fun, so I’m currently picking at short stories by George Saunders. Just the right amount of weird.

Destination: Marfa. Worth the journey. I’ve been lucky to visit a handful of times over the past few years, doing research on Donald Judd’s furniture practice. The wide open sky of West Texas has a very special quality.

Motto: I once had a keychain that said “Screw it, Let’s do It.”

Prized possession: Right now I’m really excited about my 1953 O’Keefe and Merritt stove, which I just put into my kitchen. I have many small collections of really wonderful and quirky objects, but I love the four-inch pine needle basket that my mom wove for me at our family forestry-service cabin in the Sierras, where I am right now.

THE QUERY

Where were you born?

At home in Los Angeles.

What were some of the passions and pastimes of your earlier years?

Certainly when I was a child I was a big Lego fan. But I also took art classes at Dorothy Cannon’s renown studio in North Hollywood, which exposed me to paint and clay and charcoal. She was an amazingly encouraging teacher.

What is your first memory of architecture as an experience?

When I was four, my parents bought their 1930s ranch house across the street from my mom’s sister, and worked with an architect to build an addition. I have early memories of exploring the house under construction, and especially sitting at the bottom of the empty swimming pool and marveling at the scale and curves and very different quality of space inside the concrete shell.

How did you begin to realize your intrigue with architecture and design?

I think I was always interested in building and making things, even as a child. My dad and I used to make model rockets, and we built my bedroom furniture to my designs when I was around 13. I also remember traveling with my parents in the UK when I was 14, and chose to take them to the Design Museum in London because of an ad I saw in the underground. It was a Verner Panton exhibition, and from then on I was hooked on the idea of total environment. The psychedelic aspect was pretty good, too.

Why does this form of artistic expression suit you?

I think I’m interested in the logic of design and architecture – the creative response to problem solving. But I really get excited when the boundaries break down, and the architecture or design response is an artistic critique of societal conditions, and perhaps a vision for an alternative future.

What led to your coming on board with the San Francisco Museum of Art?

I knew I wanted to study architecture, but not necessarily practice it. My interest in art led me to explore curatorial practice as a way to combine the two.

What is your greatest challenge in this role?

Each exhibition or program has unique challenges. Working with living artists is a really exciting challenge – pushing and pulling in a dialogue while keeping their vision pure. I think the greatest challenge is that I never feel like I have enough time for robust scholarship on any exhibition, no matter how far in advance I begin planning.

Is there a project along the way that has presented an important learning curve?

Each project is an opportunity for growth in a different arena. I think my very first project at SFMOMA, which was designing the giant walk-in freezer that housed the Olafur Eliasson ice-covered hydrogen powered race car chassis called Your mobile expectations, set a high bar. The car fit in the freight elevator by two inches and we had a pretty hard time calculating what it would weigh once laden with its frozen shell.

What exhibition remains most memorable, even today?

There are two exhibitions I have curated that I actually see as a continuation of a single idea. Field Conditions (2012) and Tomás Saraceno: Stillness in Motion – Cloud Cities (2017) each deal with pushing the boundaries of architecture as conceptual spatial practice, with foray into the hypothetical and visionary. I worked with some amazing artists in Field Conditions, and was very excited to put drawings by Lebbeus Woods on view that I had studied in undergraduate school. I acquired those drawings for the Museum collection, and then co-curated the first comprehensive survey of Woods’ work after his passing.

How would you describe your creative process?

As a curator, you’re always looking around for new artists and projects, and connecting them to explorations in the past. I think my process is really just about trying to see as much as possible and trusting my instinct when it comes to what I think is interesting, and want to share with the Museum’s audience.

What three tools of the trade can’t you live without?

I’m completely indebted to our museum library, and the ability to access hundreds of amazing publications. Obviously the internet is an indispensable research tool, but I try to not get mesmerized by it – you can get tangential quickly. And without my glasses I’d have a hard time doing anything, so I have to credit LA Eyeworks for keeping me bespectacled with their amazing frames.

How has your aesthetic evolved over the years?

I lean toward simple and beautiful things, often with history, or some sense of timelessness.

Is there an architect/designer living today that you admire most?

For many reasons, I tremendously admire Olafur Eliasson. His multivalent practice spans many of my interests, from complex geometry to color and light. Beyond sculpture, he works in architecture and design, as well as humanitarian and socially driven design work. And his studio culture is really quite incredible, revolving around food and collaboration.

What has been a pivotal period or moment in your life?

I lost the 1907 loft that I had lived in for a decade to a house fire in 2014. It was a 2,000 square foot unfolding architecture project that I had spent ten years building and rebuilding, and was the center of my world. A fire at the other side of the building ended up red-tagging the entire structure, and all the tenants were subsequently evicted. I spent the next few months in formative self reflection, and can attest to the power of pushing through.

Do you have a favorite artistic resource that you turn to?

I spin through a handful of different art, design, and architecture websites. I think biennials and triennials are amazing opportunities to see so many contemporary projects at once.

From where do you draw inspiration?

Inspiration is everywhere, if your eyes are really open.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received?

Certainly to remain open to new ideas and experiences. Say ‘yes’ until you have to say ‘no.’ This can be problematic when you say ‘yes’ to too many exciting projects. Really, the best advice is to just show up, and see where it goes.

Is there a book or film that has changed you?

I have always been fascinated by Film Noir for its portrayal of architecture, and the city as a character that is laden with nefarious potential. I love the art of storytelling, whether in cinema, poetry, or history.

Who in your life would you like to thank, and for what?

I am in general incredibly grateful for so many people who have had a positive impact on my life, from family to friends and colleagues. Two people I would love to thank, but can’t, would be both of my grandmothers, who were each incredible artists in their own right and taught me how to look, and see, the creative potential inside me and in the world beyond.

What are you working on right now?

I just delivered a commencement address for the graduate programs at the California College of the Arts, so that was something that I had been focusing on until last week. I’m currently wrapping up the details on an exhibition catalogue that I am the co-author of, with my colleague Jennifer Dunlop Fletcher, on The Sea Ranch, which will launch when the show opens at the Museum in December. Next month I’ll open a small show of Steve Frykholm’s playful Summer Picnic Posters for Herman Miller, which he created from 1970 to 1989. And, in two months, I will be opening an exhibition that I am curating on the furniture practice of Donald Judd, which I am very excited about. We will have Judd-designed chairs outside the gallery that our visitors can sit in!

What drives you these days?

I’m coming out of an incredibly busy six months, with opening four exhibitions, teaching, and writing for various projects, so I’m just counting down days until I can take some time off in August.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jim Leija

Director of Education & Community Engagement

University Musical Society

Ann Arbor, Michigan

ums.org

Photo by Peter Smith

Jim Leija serves as director of education and community engagement for the University Musical Society (UMS), the 139-year-old nonprofit performing arts presenter affiliated with the University of Michigan, and 2014 recipient of the National Medal of Arts. He began at UMS in the marketing department, serving first as public relations manager and later as the manager of new media and online initiatives. Jim was promoted to the position of director of education and community engagement in 2011. In his current role, he provides the strategic direction for UMS's community, University, and K-12/youth engagement and education programs, and leads the team that produces over 125 free or low-cost education events. In 2014, he was publicly elected to a four-year term as a trustee of the Ann Arbor District Library, where he serves as treasurer. Additionally, he is a trustee of Dance/USA, where he is chair of the dance presenters council. Jim is an occasional filmmaker and performer, and took top prize in the 2014 University of Michigan Stamps School of Art & Design Alumni Exhibition. His non-fiction performance essay, “dance or die,” is published in the anthology Queer and Catholic (Routledge). Jim holds three degrees from the University of Michigan: a master of fine arts in art and design, bachelor of arts in sociology, and bachelor of fine arts in musical theatre. He lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan, with his husband, Aric Knuth, and their two rescue dogs, Maisie and Olive.

FAVORITES

Book: Tales of the City by Armistead Maupin

Destination: Tulum, Quintana Roo, Mexico.

Motto: Everything doesn’t happen for a reason, but every single thing can be made useful.

Prized possession: My wedding ring.

THE QUERY

Where were you born?

St. Clair Shores, Michigan; a suburb of Detroit, about 15 miles north of the city in the much-discussed (post-election) Macomb county.

What were some of the passions and pastimes of your earlier years?

I was the prototypical music and theater kid. I think my first documented public performance was in the first grade at a school talent show. I performed an acapella rendition of “Do-Re-Mi” from The Sound of Music. We had been to Frankenmuth recently where my mother bought me some kiddie lederhosen…so I really looked the part. I went to Catholic school for 12 years, and much of my musical training came through church music. I was in the choir, and took piano lessons from the church music director. In high school it was band, show choir, community theater, school musicals, forensics – just all of these things.

What is your first memory of art/performance art as an experience?

As a child, I was really lucky to benefit from many of the cultural assets of Detroit, and I have vivid memories of field trips to the Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit Historical Society, Belle Isle Conservatory (a particular favorite of our family during the long Michigan winters), and performances at (the now demolished) Ford Auditorium. I was always dazzled by the theatricality of the “Old Streets of Detroit” exhibit at the Historical Society. I loved the warm-weather escapism of the Conservatory, and the monumentality of Diego Rivera’s mural is imprinted upon me for a lifetime. In terms of performance, I have an early memory of seeing a ballet at Ford Auditorium – probably first or second grade, and I have no idea what ballet or what company. It was the whole experience: such a big deal to “go to the city,” both thrilling and scary for a young person, and being with all the other kids from Detroit and the suburbs, in a space created for kids. How absolutely dazzling it was when the lights went down and the curtain came up and we were all transported. The arts really do transport us - literally, intellectually, and emotionally.

How did you begin to realize your intrigue with the fine arts/musical theatre?

The Birmingham Theater used to be a small regional theater and produced a season of plays and musicals (now it’s a movie theater). My mom had planned a trip with her friends to see Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific. At the last minute someone couldn’t go, so they decided to give the extra ticket to me. I was in the 5th grade (just about 10 years old), and I was absolutely captivated. Up until that point, I hadn’t seen such a fully produced, professional, and adult piece of theater. Think about it: in South Pacific you have racism, war, politics, interracial marriage, blended families, and on and on. Not to mention one of the most beautiful scores in musical theater repertoire.That was the first moment when I understood that the making of theater was a professional pursuit as well as an artistic one, and that the theater could really say something important about our society. When I saw the revival of South Pacific a few years ago at Lincoln Center, I was still so moved by it. At the end of the play, Nellie Forbush (from Little Rock, Arkansas) makes the decision to confront her own racism and bias, and stretch herself beyond her personal comfort zone. The show was written sixty-plus years ago and it still means something.

Why does this form of artistic expression suit you?

I’m a naturally expressive person, and theater and music have always been a space where I’ve felt comfortable being myself.

What led to your decision to work with the University Musical Society in January 2008?

After finishing the MFA program in art & design at the University of Michigan, I went out looking for jobs at performing arts organizations. In graduate school, I learned a lot about digital media, and was exploring how to use the very new platforms of YouTube and Facebook to distribute my own artistic work. I figured I had something to offer in terms of digital and social media, and I eventually became UMS’s first social media manager.

What is the greatest challenge you face in your current role as director of education and community engagement?

Very simply, we have limited resources, and we can’t do everything. Setting our priorities and sticking to them is extremely important. Last year, the education and community engagement program created a strategic work plan that lays out our purpose and priorities for the next several years. We’re placing a particular emphasis on accessibility and permeability in our programs, and on using the arts to engage in important and necessary conversations in our community. For anyone who is interested, you can find our strategic work plan on the UMS website.

How are you changing K-12 youth engagement and education programs in the Ann Arbor community?

One of the major goals of our strategic work plan is to reach many more underserved youth through the School Day Performance program. We’ve set a goal that by 2020, 65 percent of participants in UMS K-12 programs will qualify as underserved. We define underserved in a few different ways: schools where 50 percent or more students qualify for free or reduced lunch, schools where there is no full-time arts teacher, classrooms that primarily serve students with disabilities or special needs, and/or schools that have never had an experience with UMS before. Many schools qualify in more than one category. One of our partners in this work is the University of Michigan Credit Union which has helped us launch the Arts Adventures Program through a major endowment gift. Through Arts Adventures, we’re able to offer bus and ticket grants to support underserved schools in attending school day performances. This year we’ve given away over $10,000 in grants, with about 40 percent of grants going to schools in Washtenaw County, and the other 60 percent beyond Washtenaw. $10,000 is a great start, but we need to continue to grow this resource so that we’re able to remove any financial obstacles to participation.

Is there an educational event (K-12) you’ve worked on which remains most memorable, and why?

Last season, we presented a documentary theater production for local high school students of Ping Chong+Company’s Beyond Sacred: Voices of Muslim Identity. The show featured the real-life stories of several young Muslims from the New York City area, most of them in their early 20s. The show landed in Ann Arbor in February 2017 just as Trump announced his travel ban on several Muslim-majority countries. In that moment, I was quite proud to be presenting a show to young people in our community that confronted Islamophobia head-on. The Q&A after the show got heated at moments as there were Muslim students in the audience who had been directly affected by the travel ban, and there were also students who came from communities that supported Trump. That UMS was able to create a space of dialogue and debate for young people about a pressing social issue speaks to the power of the arts to shape the way young people see the world.

What do you enjoy most in your role as trustee/treasurer at the Ann Arbor District Library?

I hear all the time from people in our community how much they love the library, and it’s incredibly gratifying to know that my service on the board is supporting an institution that people truly care about. From a philosophical standpoint, I love serving on the library board because it is one of the most inclusive and democratic spaces in Ann Arbor. As treasurer, I’ve enjoyed learning about the ins and outs of governmental budgeting (I’m a little nerdy that way), and I do feel a responsibility to make sure our valuable tax dollars are spent responsibly and in a way that will have the most impact.

Is there a project on your radar you'd like to bring to the Library?

I’m really proud to have contributed to the process surrounding the new Westgate Branch. The old branch was 5,500 square feet, and we were able to expand into a beautifully remodeled space that is now 21,000 square feet with study rooms, a large kids area, bookable meeting rooms, and a café provided by Sweetwaters Coffee. The feedback on Westgate has been excellent, and the branch has been transformed into a bustling, vibrant community space. Westgate is a kind of prototype for how we might reimagine our downtown Branch. I believe that Ann Arbor deserves an absolutely top-notch downtown space. The AADL staff have made so many creative changes to the way we use the downtown branch in order to accommodate hundreds of programs and thousands of visitors every year. But the fact remains that we’re operating in a space that doesn’t have the infrastructure to support the incredible usage. For the past year, the board has been engaged in a process of considering the future of the downtown library branch. As a community, I hope that we’ll arrive at the conclusion that we deserve a downtown branch that supports the vibrancy of our community and our community’s love of lifelong learning.

How would you describe your creative process?

I’m improvisatory and iterative, and I love working in groups. I need to be in a space where I can try out ideas in front of others and get feedback in real time. I like to generate as much as possible before organizing, prioritizing, and strategizing my final output.

Is there a project along the way that has presented an important learning curve?

In January, UMS introduced a new series called No Safety Net, which presented four theater performances engaged very explicitly with pressing contemporary social issues. Over three weeks we explored terrorism, racism, transgender identity, and mental health/radical healing; each performance was accompanied by an array of community educational events. The series was an enormous undertaking both logistically and psychologically. As an organization, both the staff and board went through an almost yearlong process of educating ourselves about these issues, and confronting the possibility that we might offend and shock our audiences with some of the presentations. We learned a lot together, especially how to take strategic risks and respond to a fuller range of audience reactions.

What three tools of the trade can’t you live without?

A great network of trusted colleagues. An open-mind and a curious attitude. A really great cup of coffee

How has your aesthetic evolved over the years?

Lately I find myself drawn to live performances that are engaged with contemporary social issues, but in ways that are unexpected, poetic, challenging, and often abstract. Dance and movement artists hold a special appeal to me because, in certain ways, the expressive capabilities of the body are so much greater than anything that can be conveyed in words. I’m surprised that I find myself drawn more and more to performances with few or no words. I enjoy ambiguity and the challenge of making meaning for myself.

Is there an artist/performer living today that you admire most?

This is an impossible question to answer! I find myself inspired by so many artists! If I have to name one artist, I would say Taylor Mac. Taylor has created a 24-decade history of American popular music that is a 24-hour performance. UMS commissioned three decades of this project in February 2016. Taylor is a kind of drag-queen-shaman-clown-goddess-rebel figure whose show is a wildly creative reimagining of American history through a queer, radical lens. Taylor’s genius is in using humor and charm to convince a very mixed audience to go on a journey that tackles racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, and capitalism. Because the work is being presented across the United States by major presenters like UMS, Taylor attracts a mixed crowd…and by mixed, I mean that not every person in the room identifies with Taylor, and, yet, most everyone is willing to go along for the ride. I think there’s real power in that – to be able to preach to the choir while simultaneously educating others.

Do you have a favorite artistic resource that you turn to?

I rotate between The New York Times, The New Yorker, and Vulture (New York Magazine). For cultural commentary, I’m an avid reader of the feminist culture and news blog Jezebel. And I’m a big fan of The New York Times podcast Still Processing hosted by Jenna Wortham and Wesley Morris. Wortham and Morris are having one of the most interesting ongoing conversations about contemporary Black life in America at the intersection of arts and culture, tech, politics, and social justice. If you’re not listening, you should be.

From where do you draw inspiration?

As a queer Latinx person, I’m really inspired by the proliferation of new voices and stories from people of color, queer people, transgender people, and women across film, television, online media, and theater. There is a new wave of creators telling stories from the margins, and there are audiences for these stories. I think this is most pronounced in television where you have shows like RuPaul’s Drag Race, Insecure, How To Get Away With Murder, Transparent, Dear White People, and Eastsiders. And, of course, Black Panther has been an absolute tidal wave of success in shaking up the otherwise conventional space of superhero movies. I hope this kind of storytelling and media representation is a harbinger for a more politically, socially, and economically integrated society.

What three things can’t you live without?

DVR (we are in the golden age of television). Classic 8-inch Wusthof Chef’s Knife (an essential tool for the home cook). My dogs, Maisie and Olive.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received?

My mom always says to me, “one day at a time.” Sometimes that pisses me off because it just seems like impossible advice to take. But for someone like me, who says ‘yes’ to just about everything and is constantly juggling lots of projects and passions, it’s absolutely essential advice.

Is there a book or film that has changed you?

The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan was really transformational for me. In lots of ways, that book is the manifesto of the contemporary locavore movement, and it still resonates for me today. I read the book when it came out 11 years ago. I was in my late 20s and starting to really question what I knew about food - where it came from, how it was produced, how it was prepared, packaged, and delivered to me. Some of my interest had to do with being an overweight teen and adult, and I was trying to discover better ways to take care of my body. That book truly changed the way I interact with food. I became a devoted home cook, and now I try to eat as seasonally as I can and take full advantage of the Ann Arbor Farmers Market throughout the year. Since reading that book, we’ve had a farm share with Tantre Farm in Chelsea, Michigan, and it really is a privilege to know Richard and Deb, the farmers who grow the food and to be able to actually visit the place where the food is grown. Our community is extremely privileged to have access to this kind food system.

Who in your life would you like to thank, and for what?

My maternal grandmother, Mary Miller taught me how to lead with a spirit of unconditional love and strive to create community in every context. My mom, Mary Beth, has supported my wild artistic dreams my whole life and never made me feel like the arts wasn’t a good path for me. My dad, Jim, for my irreverent sense of humor. The UMS staff is awesome and does incredible work, and I’m particularly grateful to my core team of colleagues in education, programming, and production who make it all happen. And, of course, my husband Aric Knuth, for his willingness to go on any adventure with me.

What drives you these days?

We’re in a rough period as a culture. I really do believe that the performing arts are a pathway to healing ourselves and rejuvenating our culture. I keep doing this work because it is wildly optimistic, and it helps us imagine a better future. That’s what drives me.

0 notes

Text

João Canziani

Photographer/Director

New York City, New York

Los Angeles, California

joaocanziani.com

SPECIAL GUEST SERIES

João Canziani is a New York City-based photographer and director specializing in advertising, editorial portraits and travel, and personal work. His photographs have been featured in such publications as Afar, Bloomberg Markets, Travel & Leisure, Monocle, New York, Fast Company, Outside, Esquire, Real Simple and Wired, among others. João’s client list spans the likes of Apple, Nike, Delta Airlines, American Express, Microsoft, Verizon, and Lyft. He earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, and a BFA in photography at the Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles. The recipient of numerous awards, João has been recognized by American Photography and PDN Photo Annual. When he’s not working, you can find him bouncing his nine-month-old daughter, Paloma, on his lap, or running around Prospect Park when he’s “had enough with retouching or taking care of business.” João lives in Brooklyn with his wife Jordan, daughter, and “little pipsqueak of a dog” called Reggie.

FAVORITES

Book: I’ve been reading Werner Herzog’s The Conquest of the Useless over the past few months, and I love it, but it’s been difficult to finish. I blame Paloma and the stop-and-go nature of my job. But also, I’d rather talk about favorite movies than favorite books. And if there’s one movie I’ve loved over the past year, it’s Call Me by Your Name. So if you’re reading this, and you haven’t already done so, go see that movie.

Destination: For shooting, most likely India. The light is incredible due to the smoke, I suspect. But that would be nothing without the rich, complicated, and chaotic culture there. There are a thousand stories happening at once on the street, and the moment you click the camera, you get sucked into wanting to dig at it more. Also, drop me anywhere in Italy.

Motto: It sounds so cheesy and somewhat banal, but for me it is, “You only live once.” I strive to live by it, and bug dear friends from time to time that they should too.

Prized possession: My iPhone. I really don’t know what I would do without it. Everything in my professional life goes through it. But I guess I would be liberated if I’d lost it.

THE QUERY

Where were you born?

Lima, Perú.

What were some of the passions and pastimes of your earlier years?

I liked to draw when I was a kid - elaborate drawings of machines and vehicles and things, inspired by the gadgets of James Bond and Star Wars and such. I was set, I thought, to be an industrial designer or architect.

What is your first memory of photography as an experience?

I don’t think I can remember the first memory, but I do remember, after we moved from Perú to Canada, bugging my dad to no end when I repeatedly asked him to stop the car so that I could take a picture of the landscape when we took our weekend family road trips.

How did you begin to realize your intrigue with the art and science of photography?

I started shooting the last couple years of high school, and I took a photography class with a very nice teacher. Then at home, I took what I learned and I built myself a little black-and-white darkroom in the basement bathroom. I used to lock myself in there for hours. The pictures weren’t very good, but I loved being in there.

Why does this form of artistic expression suit you?

As I mentioned, I thought I’d be an industrial designer or architect. I also loved graphic design. But somewhere along the line, I decided that I didn’t want to be stuck in an office or studio all day. Photography offered me the chance to know the world, and then it taught me that I could enjoy the aspects of photography such as color and composition.

When and how did you get your start in the profession?

I moved to the U.S. from Canada in my late twenties so that I could study photography at the Art Center in Pasadena, California. I finished the full eight terms of school without a break inbetween, but unfortunately I graduated right before September 11, 2001. I was actually in New York for the first time when it happened. Long story short, this event halted my plans and career for a bit, as everything got disrupted. As you could imagine, starting a photography career right after that was quite tough, if not impossible. So for the next couple of years I assisted other photographers instead and got a little lazy and unmotivated. But slowly I got up, built a more relevant portfolio of personal work I had, and starting knocking on magazines’ doors. It took a while, but a magazine called The Fader called me back, and I started shooting small but really rewarding assignments of upcoming actors and music bands.

Is there a project/period along the way that has presented an important learning curve?

Yes, right after I moved to NYC, in 2009. I had another awakening, as if the world of photography became my oyster, and I started pushing myself to produce work that I was really happy with. I left this feeling of complacency behind.

Where have your travels taken you on assignment work?

Very fortunate to say that to quite a lot of places around the world. I’m currently in South Africa for the first time. First time in Africa, in fact. And after this I fly to Barcelona for another assignment. There’s still a huge chunk of Asia I don’t know either.

Is there a most memorable shoot, and why?

Yeah, I think this series of shoots I did for Apple toward the end of 2013. I worked alongside a director that inadvertently planted the seed in me to pursue more motion projects. If I’m allowed to name-drop one person, then let it be him (people that know me are likely really tired of me mentioning him, but I have to here, one last time): Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, cinematographer extraordinaire of films such as The Revenant, Children of Men, and Birdman. Apart from that, these shoots were so special because they took me to India and China for the first time. I fell in love with India.

Do you have a favorite photographic image in your portfolio?

Oh man, it’s tough to pick just one. But if I have to, I suppose this blurred image of the moon and the forest in Patagonia that I shot in June of last year when I profiled chef Francis Mallmann for Esquire magazine.

What is the greatest challenge in capturing a very personal portrait?

Trying to break through the inhibitions and/or complexities of a person, particularly when that person has rarely been photographed (a “real” person, the somewhat ridiculous term people like to call those that don’t get shot for a living).

How would you describe your creative process?

Hmmm, that’s a good question. Striving for balance in life I guess: feeling confident and good about oneself. For me, this means going running (or swimming in summer), enjoying good food and a good bottle of wine on occasion, spending quality time with my family, and most importantly shooting often, whether personally or for clients. I find this balance is the only way that I can feel creative enough to be able to try to discover new ways of seeing, for myself.

What three tools of the trade can’t you live without?

A camera, computer, and credit card.

How has your aesthetic/style evolved over the years?

I used to strive to shoot in a more formalistic way, as I shot a lot of 4x5 and medium format film. I used to think of complete and very neat (in the orderly meaning of the term) compositions and right angles. But I started breaking that down and trying to be a bit less derivative and boring. I began to get excited with infusing more color into my work, and striving to be a bit more intense and visceral.

Is there a photographer living today that you admire most?

Yes, indeed. Maybe these two if you’re asking me this question at this very minute: Christopher Anderson and Erik Madigan Heck.

What has been a pivotal period or moment in your life?

It used to be the first couple of years in New York, but now most definitely the birth of my daughter in the spring of last year. I know the repercussions of this event are still developing and growing in front of me, meaning that I know that over the years she will keep on inspiring me, but today is just the beginning.

Do you have a favorite artistic resource or inspiration that you turn to?

Oh boy, the first thing that comes to mind is Instagram. Take it or leave it, but I get inspired a lot there, particularly when I’m unable to go to a museum or a gallery because we’re at home with our daughter. But actually, other than that, I love watching movies and well-written TV shows. And, other photographers’ work I find through Instagram or online (it used to be Tumblr). Music. Music! But a bit of everywhere really.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received?

Maybe an implicit advice I tell myself: Some things are just not meant to be. Give it a good fight, but know when to move on.

Is there a book or film that has changed you?

Not sure if there’s something that has “changed” me like that, completely. But so many films or books have changed me gradually, over the years, nourishing and developing the way I see the world creatively.

Who in your life would you like to thank, and for what?

My wife for giving me the most precious gift.

What are you working on right now?

Currently editing this assignment I just finished in South Africa, and getting ready to embark on another in Spain.

What drives you these days?

The need to create, the need to discover, the need to love.

0 notes

Text

Lauren Friedman

Artist/Stylist/Author

Ann Arbor, Michigan

laurenfriedman.com

Photo by Emma McAlary

Lauren Friedman is an artist, stylist, and the author/illustrator of 50 Ways to Wear a Scarf (2014), 50 Ways to Wear Denim (2016), and her newest title, 50 Ways to Wear Accessories, slated for release in July 2018, all published by Chronicle Books. She is also the creator of the My Closet in Sketches project, an illustrated-style blog launched in 2010. Lauren’s work as a professional illustrator has appeared in numerous publications, including Travel and Leisure, The Washington Post, and Lucky. Her books have been featured at the Museum of Modern Art, The Paper Source, Target, and other fine retailers globally. Lauren graduated from Wellesley College, where she studied political science and played on the varsity field hockey team. Upon graduation, Lauren moved to Washington, D.C., where she lived for over nine years. Lauren has worked in a variety of fields, including posts as a production assistant, operations manager, financial educator, optometry salesperson, yoga teacher, barista, chalk artist for restaurants/cafes/businesses, mural artist, stylist, closet consultant, and, finally, as a freelance fashion illustrator. When she’s not working, you can find her reading, dancing, and taking long walks in the woods. A native of Ann Arbor, Lauren returned to her home town in May 2017 and lives on the West Side.

(Click here to pre-order Lauren’s latest book)

FAVORITES

Book: I could never pick just one, but I’m currently in the midst of rereading (and loving) The Clan of the Cave Bear series by Jean M. Auel.

Destination: A body of water within walking distance to a great place to grab good food and a cold beer.

Motto: Your reality is what you make of it.

Prized possession: Any of the number of accessories or clothing items passed down from my family members.

THE QUERY

Where were you born?

Ann Arbor, Michigan.

What were some of the passions and pastimes of your earlier years?

I loved drawing clothes and people, trying on countless outfits, writing stories, reading stacks of books, and poring over magazines. I consider my life to be a success because my current passions and pastimes align closely with what I spent time doing as a kid.

What is your first memory of art/illustration as an experience?

When I was five or six, I wrote and illustrated a book called The Miracle of the Rainforest through one of those services that turn your words and pictures into a real, hardcover-bound book. It is the tale of an unlikely friendship between a sloth and the daughter of a logger baron who ends up saving the future of the rainforest. I’m not sure I could write a better story today!

How did you begin to realize your intrigue with fashion and design?

Fashion and design has always been my reality, from birth. From the moment I could dress myself and hold a crayon or book, I had a burning desire to express myself through what clothes I wore and what art I created.

When/how did this segue into your entering the profession of illustration?

I created the blog My Closet In Sketches in 2010 in the middle of a creative drought. I’d just graduated from college and was working a 9-5 job as an operations manager. I found that the best part of my day was getting dressed for work, combining my own clothes with wonderful pieces passed down from my grandmother and mom. I began a nightly practice of dreaming up fun outfits and drawing them when I got home from work. Within a year of creating the site, (the now defunct) Lucky magazine approached me about illustrating a monthly beauty advice column. I’ll never forget how stressed I was during that first month’s batch of drawings, but I taught myself how to draw professionally through that two-and-one-half year experience.

Why does this form of artistic expression suit you?

It combines both of my passions of fashion and art. However, I still need to honor my creative desires through other fluid, non-professional expressions including collage, painting, clay, and whatever other mediums I can get my hands on.

What did you enjoy most about the illustration component of My Closet in Sketches?

The pursuit of excellence. As a self-taught illustrator, I always have more to learn. I enjoy acting as my own coach, boss, intern, and student.

How did you approach the writing element of the series?

The art of writing is as important to me as the illustration component. The early concepts are always written by hand, and then, when it’s time to bring it to the computer, I do not allow my brain to filter any words as they are typed. Nothing is deleted. The editing will come later.

How would you describe your creative process?

Almost every idea starts as a scribble or doodle in my journal. These quick, unfiltered ideas may take days or years to germinate. I enjoy the process of witnessing my mind turn concepts around, both consciously and unconsciously. By the time of final creation, I generally have a good idea of what it will look like — but there is always room for surprise. The biggest discipline required is to learn when to step back and let something rest rather than belaboring it into overworked territory.

When/how did the concept for 50 Ways to Wear a Scarf take seed?

This is a true story about being careful what you wish for. When I struck out on my own as a professional illustrator in 2010, a friend suggested that I make a list of my one, five, and ten year goals. Boldly, I wrote, “publish a book with Chronicle Books” under my one year goals - I always loved their offerings, which are consistently colorful, informative, cheeky, and a pleasure to read. Fast forward a year and a half later - I received an email from an editor at Chronicle Books who had seen this post about how to wear a scarf, asking me if I would write and illustrate a book about scarves. I was shocked. I knew I couldn’t say no, even though I didn’t know the first thing about writing a book, but I had no choice but to give it a try. It combines my two biggest passions: art and words.

What did you find most challenging in creating your three books?

Each book takes me over a year of full-time dedicated work. My biggest challenge isn’t the motivation to undertake this work, but rather the daily transition back to the of the rest of my “real-life.” In many ways, while doing this work, I become like a god of my small universe - the only limits being the boundaries of the page. I imagine myself an astronaut, taking a daily journey through space, performing these acts of creation in an exultant, weightless, timeless manner. Figuring out how to land back down on the ground when the work day is done requires a constant vigilance of meditation, yoga, quiet walks, and lots of boundary setting.

Where do you do most of your work?

When I’m illustrating, I work from my home studio. When I’m writing, I do some of my best work at coffee shops or cafes.

What three tools of the trade can’t you live without?

Paper, pencil, and markers.

Is there a period/project along the way that has presented an important learning curve?

I had no experience illustrating professionally when Lucky magazine hired me. Through the tireless help of their art director, I learned how to ask the right questions, advocate for my work, and remain flexible when things (inevitably) change.

How has your aesthetic/style evolved over the years?

The only constant to my aesthetic and style is change.

Is there an artist /illustrator living today that you admire most?

If I could draw a line with half the grace of David Downton, I would die a very happy fashion illustrator.

Do you have a favorite artistic resource that you turn to?

I tear out pages for my inspiration files from Vogue, Glamour, Teen Vogue, Seventeen, The New York Times Style Magazine, Elle, and The Gentlewoman.

From where do you draw inspiration?

Inspiration comes from everywhere. I try to follow one of the main tenants from the book The Artist’s Way (by Julia Cameron) by taking myself on an artist date once a week. That could mean going to a museum, watching a film, or sitting on a street corner watching the fashion walk by. The important thing is to just keep feeding the creative fire with fresh kindling.

What three things can’t you live without?

A Moleskine unlined notebook, a Pentel .7mm mechanical pencil, and my eyeglasses.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received?

It’s never about what it’s about.

Is there a book or film that has changed you?

Women Who Run With Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estés. Also Romy and Michelle’s High School Reunion and Clueless.

Who in your life would you like to thank, and for what?

No amount of talent can prosper without a support system. My family, friends, and teachers all indelibly, persistently, unconditionally give me the space and encouragement to take my goals and creative instincts seriously.

What drives you these days?

Using my gifts to inspire change and inspiration in others.

#laurenfriedman#blog#myclosetinsketches#visualarts#annarbor#chroniclebooks#illustrator#author#design#50waystowearascarf

1 note

·

View note

Text

Camden Shaw

Cellist

The Dover Quartet

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Photo by Carlin Ma

SPECIAL GUEST SERIES