Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Interior Voices of America in If Beale Street Could Talk

*SPOILERS AHEAD*

Barry Jenkins follows the success of MOONLIGHT with a dynamic, intimate story based on the novel IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK by James Baldwin.

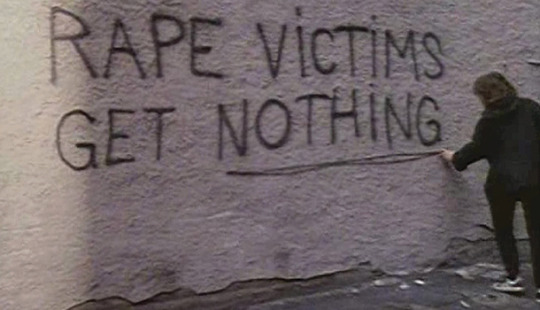

It is incredibly regrettable to say that the progress we have made is still not enough to claim we are better off with our current justice system. Last year, the case of Cyntoia Brown rose to the public eye when she was granted clemency after serving 15 years in prison for killing a man who bought her for sex when she was only 16 years old. Brown saw little justice in her case; at the same time, unharmed people from poor minority communities have repeatedly been more likely to be stopped or gun-down by police officers. Philando Castile was shot down inside his car after being stopped by a police officer and informed him that he had a permit for his gun. Botham Jean was shot down by his downstairs police neighbor while in his own home because she thought she saw him breaking into her apartment. Stephon Clarke was shot in his grandma's backyard because the cops believed he was reaching out for a gun which turned out to be a cellphone. These crimes appear to be a never-ending disease. Their names along with the names of every victim who have suffered from systemic racism enforced by the people who are supposed to protect them should resonate in the voices of every citizen of this country. Instead, what we get are the typical "what happened before" questions, short mainstream media attention, and little discourse provided by our legislators.

In part, IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK is a masterfully crafted film which allows audiences to reflect on the consequences of our country's racist epidemic through characters' emotions.

We begin the film with an aerial tracking shot of Alonzo "Fonny" Hunt (Stephan James) and Clementine "Tish" Rivers (KiKi Layne) walking down the stairs next to a river. The camera, located at a physically higher position than them, is brought down to a medium shot of the couple holding each other, followed by a medium shot of the characters starting at the camera. Almost never again in the film do we get an aerial shot like the opening one, but we do get ceaseless amounts of medium shots of the characters at eye level; suggesting we might have walked into the film with a similar preconception of the characters but to understand their story, we have to see them at their same level.

Revealing the news about Tish and Fonny's baby also reveals a candid understanding of the characters, particularly the two grandmothers. Tish's mother Sharon (movingly portrayed by Regina King) is caring and firm about the way she questions Tish in the kitchen. When it comes time to reveal the news, a medium shot of a nervous looking Tish staring up at us cuts to her family in their living room. Now Sharon is informed, and they are both telling the rest of the family together. This leap is indicative of the love Sharon has for her daughter. By establishing the two characters' relationship, looking through Sharon's eyes, and suddenly cutting before Tish even says anything, we understand that Sharon doesn't need to hear a reason to feel empathetic for her daughter. The abrupt absence of a moment depicts an image of motherly affection.

Fonny's parents Mr. and Mrs. Hunt (Michael Beach and Aunjanue Ellis) give polar opposite reactions to Tish's announcement. While Mr. Hunt celebrates, Mrs. Hunt disapproves of the conception and condemns the two for having sexual relations in the first place; Fonny's sisters also reinforce a derogatory language towards Tish. The self-imposed judgment that they adopt has little to do with religious belief as Mrs. Hunt expresses and more with societal oppression against African Americans. One only needs to observe both their attitude and costuming to understand. Their dresses are reminiscent of the traditional 1960s wife fashion and their hair is combed down as to imitate that same style. This look is in sharp contrast to Tish and her sister's high-waisted pants and afro hair, which was typical of the 1970s black woman. The willingness of Mrs. Hunt and her daughters to turn back on their culture and attack those who suffer in the same struggle suggests that they have fallen victim to a system which wishes to suppress and divide black Americans. While it successfully manages to segregate these two families, Ellis' performance as she leaves the house illustrates the character's inner confliction. Mrs. Hunt goes from forcibly mouthing the words "that child" as if to proceed it with something offensive but instead, whimpers the same words out of the house. This moment is symbolical of her struggle to wish for tenderness in a society that perpetuates violence and hatred.

Immediately following the harsh interaction between the two families, we jump back to the time when Tish and Fonny went on their first date. The film's narrative is nonlinear, so it goes back and forward from before and after Fonny was sent to prison. The film leaps from periods of grief/anguish to ones of affinity/joy and vice versa. Very often we go through periods of emotional instability in our daily lives; similarly, the juxtaposition of these sequences suggests the relentless unpredictability of life itself. What's more, a lot of the sequences before Fonny is sent back to prison have a lush dream-like quality to them. We can assume this is because we are experiencing the story from Tish's consciousness and she looks back at these memories with a gentle introspection. But previous collaborator of Jenkins also reinforces this sentiment with a sweeping score that parallels the film's tone. The encompassing sounds of the harp, trumpet, and violin compose a melodious harmony deserving of its own examination.

In Fonny's apartment, their first sexual interaction is touching but shot with realistic attributes. When Fonny and Tish are kissing in his bed, the camera captures them passionately touching each other in a medium shot. The shot stays with them as they undress and the music gets progressively lower. The sequence seems to become increasingly more uncomfortable to witness when the music goes away, and there is no dialogue. Simultaneously, it places the focus on the character's body movements; this is revealing of their emotions. Tish is looking down and up at Fonny until her back in facing the camera. Fonny cannot stop staring at her with a concerned look on his face as he covers her with his sheets. When the shot cuts, it is to see Fonny play music and back again to a close-up of Tish with little space in her frame compared to him. The space in which the characters find themselves is symbolic of their own confidence. Fonny in a full shot visualizes his poised attitude while Tish's close-up visualizes her timidness. This sequence depicts the character's inner feelings at a meaningful part of any relationship.

The latter sequence is one in which its purpose is to explore the humanity of the characters, but one of the film's major themes is the subject of systematic oppression. How does a black body navigate through a sea of racist discrimination? The two scenes which best highlights this subject (and are arguably the best entirely) see Fonny and Dany (Brian Tyree Henry) having a conversation and Fonny inside prison. Both revolve around this concept and ponder on what it mentally does to its victims. In a powerful performance by Henry, we witness a man explain the reason why he got sent to prison and what it did to him. The camera pans from side to side in the conversation, creating an energetic fluidity between the two men. Every time it turns from Fonny to Dany, the tone gets severely more cynical and eerie. Henry's performance assures us that this man has been broken down; a close-up sees him utterly disturbed and unsettled, a full shot briefly captures him tearing up, he is without any consolation that "the white man" would show him justice. This scene depicts a man reflecting on a hurtful past and foreshadowing another's near future.

The next sequence does not include dialogue, and it almost relies on visuals alone to express the mentality of a man in prison. A traveling full shot of Fonny is circling him as he works on a sculpture which then cuts to a close-up of his face laying in his cell bed; this suggests that now we are looking back at one of his memories. Fonny is free to move around this space unrestrictively and the flowy movement of the camera captures this going in circles. The spatial freedom established by this shot illustrates Fonny's retrospective outlook of this memory. Next, a static shot captures his face motionless and with minimal space in the frame; another close-up shows him motionless again and with a single tear running down his face. The subtext implies that we are seeing a man when he felt his freest juxtaposed to when he felt most entrapped.

Another thing that is important to point out is the presence of smoke in the mise-en-scene of both sequences. This smoke is cloudy, all-encompassing, like a blanket hovering over the characters. One reading could see the smoke to be symbolic of the system itself, as it is restrictive and you can't seize it. Another reading could see it as a catalyst for these men to reveal their emotions, Dany expressing pain and Fonny expressing bliss. This decision is completely subjective, but the presence of smoke in these two sequences is more than mere coincidence. Nevertheless, these moments effectively dwell on systematic oppression as one of the film's main themes by portraying the emotional consequences it had on two different men.

In an interview with Slash Film, director Barry Jenkins noted on the challenges of adapting James Baldwin's novel: "so much of the power of his writing is how he goes into the interior lives of the characters. So you understand how the story is making these characters feel and what those feelings are saying about life in America, about American society. So the challenge was, how do you make a film, which is not interior text, which is all surface in a certain way – you’re outside them, you’re not inside of their heads – but how do you still translate this interior voice? "

At its best moments, IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK is a cinematic landscape of faces which communicate the interior voices of its characters. These voices represent a familiar story to its audience, one which stimulates those who have experienced prejudice based on race and influences those who have not. With the election of a bigoted president who continues to perpetuate racist propaganda, American society evidently still has many issues to address and resolve; beginning with the acknowledgment of how slavery and discrimination have evolved through our system of justice. As observers of this film, we will make a decision one way or another on how to react to the way the system treated these characters. But regardless of this, after watching IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK, we can pave the way towards being more empathetic as well as seeing another person's struggle as our own.

#ifbealestreetcouldtalk#barry jenkins#movies#film#cinema#review#analysis#america#us#discrimination#newyork#oscars#2018#books#literature#james baldwin

0 notes

Text

Issues in Narrative Cinema and How Films May Counter

*SPOILERS AHEAD*

Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (1997) stands as a provocative film that negates transparency by liberating its images from the mechanics which compose substance to language and allows them to signify meaning instead. In his essay, Godard and Counter Cinema: Vent D’est, Peter Wollen discusses the seven counterparts to the values of old cinema. When he mentions foregrounding, he explains the influence Renaissance perspective had on the language of classical cinema, just like Baudry when he introduces the idea of the transcendental subject in his essay. “The ‘language’ of painting became simply the instrument by which representation of the world was achieved” and that “it should efface itself in the performance of its task” (420) to convey meaning. Funny Games challenges this concept by breaking the transparency of traditional cinema. In the scene after Paul and Peter killed Schorschi and left the house, a long shot of the Schobers’ living room stays with Anna for longer than a minute. She is paralyzed and silent until she moves to turn off the TV which was left on. Later when Anna determines to get herself back up, the camera follows her and stops just before she leaves the living room. A motionless frame stays there with Georg for around four minutes, as he unsuccessfully attempts to stand up. Instead of being given the closure of looking at Anna’s and Georg’s faces of sorrow after witnessing the murder of their child, the audience is only provided with distance and the sound of their cries. This not only prevents the audience from identifying with the characters, as Wollen mentions is another value of classical cinema, but also allows the shot, the image, to convey a feeling of weakness, depression, and grief.By the end of his article, Baudry puts into juxtaposition the experience of being in a movie theater, with its physical limitations and lack of communication with the outside, to Plato’s analogy of The Cave. In this place is where Lacan’s mirror-stage notion is put forward. “This psychological phase, which occurs between six and eighteen months of age, generates via the mirror stage” (540), allowing for the imaginary constitution of the subject in the film. Since the world depicted on the screen is distinct from the subject, two levels of identification need to take place. The first “derives from the character portrayed as a center of the secondary identification” whose position needs to be continuously restored and the second “permits the appearance of the first”- the transcendental subject- “and places it ‘in action’” (540). As Baudry claims, the spectator identifies with the camera first, which controls the world surrounding the objective reality, and characters second, as they only form part of the objective reality. It is in between relations of the camera and the projector that a paradoxical process takes place which plays “a decisive role in the strategy of the ideology produced” (535). Through this process, an illusion of continuity is restored. Each image frame holds a difference which even though small, is clear from all others when you put them together at a close distance. Baudry goes on by saying that in a way, a film “lives on the denial of difference: differences are necessary for it to live, but it lives on their negation.” (536). Continuity movement is created by first capturing differences in the optical apparatus and later repressing those same differences in the mechanical apparatus. The transcendental subject is now given hallucinatory freedom by “the operation which transforms successive, discrete images” as Baudry states “into continuity, movement, meaning” (436). Derivative from Renaissance perspective, the camera creates a conception of space which places the eye of the subject as the center of all meaning. Baudry compares the Renaissance perspective to that of the Greeks by pointing out that the Greeks’ pictorial construction “corresponded to the organization of their stage, based on a multiplicity of points of view” (534) and that the Renaissance’s perspective was based on “a conception of space formed by the relationship between all elements which are equally near and distant from ‘the source of all life” (534). This difference is expressed to underline the ever-present necessity of narrative cinema to define the subject as a fixed point. By doing so, the visual objects the camera captures can relate back to the primary point in perspective, the eye of the subject. “Based on the principle of a fixed point by reference to which the visualized objects are organized, it specifies in return the position of the “subject” the very spot it must necessarily occupy” (534). After establishing the subject for the finished product, he brings up the need for the subject to also be transcendental.Constructing from a combination of ideas delivered by Althusser and Lacan, in his essay “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus” Jean-Louis Baudry expands upon the influence of illusory movement on the audience perception and the self as a transcendental subject to explain the restraining of narrative cinema as a device for knowledge by the nature of the apparatus. From Althusser, he borrows the concept of the Ideological State Apparatus to propose that cinema is always dependent on a dominant ideology. To support this theory, one of the main ideas Baudry directs our attention to is Lacan’s notion of the mirror stage. By placing the spectator as a transcendental subject, otherwise known as the originator of meaning, gives him or her the false assumption of empowerment via identification with the camera. In addition, Baudry discusses a work that happens “Between ‘objective reality’ and the camera, site of inscription, and between the inscription and the projection” (533) to create the finished product. The product will purposely hide the transformation that has taken place from its audience which raises the question that centralizes his argument, “is the work made evident, does consumption of the product bring about a ‘knowledge effect’ [Althusser] or is the work made evident?” (533).

At the beginning of his article, Baudry turns to the birth of Western Science, a tradition which subsequently led to the “decentering of the human universe, the end of geocentrism (Galileo)”(532). A new mode of representation was created through the evolution of optical instruments, once again assuring “the setting up of the ‘subject’ as the active center and origin of meaning” (532), that supports Baudry’s belief on the masking of the ideological effects that these instruments conceal. He goes on explaining how these instruments, camera, projection, and screen, are used to hide the ideological effects that are themselves defined by the dominant ideology.

Derivative from Renaissance perspective, the camera creates a conception of space which places the eye of the subject as the center of all meaning. Baudry compares the Renaissance perspective to that of the Greeks by pointing out that the Greeks’ pictorial construction “corresponded to the organization of their stage, based on a multiplicity of points of view” (534) and that the Renaissance’s perspective was based on “a conception of space formed by the relationship between all elements which are equally near and distant from ‘the source of all life” (534). This difference is expressed to underline the ever-present necessity of narrative cinema to define the subject as a fixed point. By doing so, the visual objects the camera captures can relate back to the primary point in perspective, the eye of the subject. “Based on the principle of a fixed point by reference to which the visualized objects are organized, it specifies in return the position of the “subject” the very spot it must necessarily occupy” (534). After establishing the subject for the finished product, he brings up the need for the subject to also be transcendental.

Baudry states “the world will not only be constituted by this eye but for it” which means what the subject sees, is no longer controlled by the body but by the movability of the camera thus allowing the subject to create a world of objective reality, a false sense of empowerment. Consciousness comes into place to give meaning to the images shown on the screen, “the image will always be an image of something; it must result from a deliberate act of consciousness”. Equally as crucial to the narrative cinema is the constitution of continuity which derives from the subject. Baudry signals our attention to how continuity is established; “it is a question of preserving at any cost the synthetic unity of the locus where meaning originates [the subject]” (538).

It is in between relations of the camera and the projector that a paradoxical process takes place which plays “a decisive role in the strategy of the ideology produced” (535). Through this process, an illusion of continuity is restored. Each image frame holds a difference which even though small, is clear from all others when you put them together at a close distance. Baudry goes on by saying that in a way, a film “lives on the denial of difference: differences are necessary for it to live, but it lives on their negation.” (536). Continuity movement is created by first capturing differences in the optical apparatus and later repressing those same differences in the mechanical apparatus. The transcendental subject is now given hallucinatory freedom by “the operation which transforms successive, discrete images” as Baudry states “into continuity, movement, meaning” (436).

By the end of his article, Baudry puts into juxtaposition the experience of being in a movie theater, with its physical limitations and lack of communication with the outside, to Plato’s analogy of The Cave. In this place is where Lacan’s mirror-stage notion is put forward. “This psychological phase, which occurs between six and eighteen months of age, generates via the mirror stage” (540), allowing for the imaginary constitution of the subject in the film. Since the world depicted on the screen is distinct from the subject, two levels of identification need to take place. The first “derives from the character portrayed as a center of the secondary identification” whose position needs to be continuously restored and the second “permits the appearance of the first”- the transcendental subject- “and places it ‘in action’” (540). As Baudry claims, the spectator identifies with the camera first, which controls the world surrounding the objective reality, and characters second, as they only form part of the objective reality.

Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (1997) stands as a provocative film that negates transparency by liberating its images from the mechanics which compose substance to language and allows them to signify meaning instead. In his essay, Godard and Counter Cinema: Vent D’est, Peter Wollen discusses the seven counterparts to the values of old cinema. When he mentions foregrounding, he explains the influence Renaissance perspective had on the language of classical cinema, just like Baudry when he introduces the idea of the transcendental subject in his essay. “The ‘language’ of painting became simply the instrument by which representation of the world was achieved” and that “it should efface itself in the performance of its task” (420) to convey meaning. Funny Games challenges this concept by breaking the transparency of traditional cinema. In the scene after Paul and Peter killed Schorschi and left the house, a long shot of the Schobers’ living room stays with Anna for longer than a minute. She is paralyzed and silent until she moves to turn off the TV which was left on. Later when Anna determines to get herself back up, the camera follows her and stops just before she leaves the living room. A motionless frame stays there with Georg for around four minutes, as he unsuccessfully attempts to stand up. Instead of being given the closure of looking at Anna’s and Georg’s faces of sorrow after witnessing the murder of their child, the audience is only provided with distance and the sound of their cries. This not only prevents the audience from identifying with the characters, as Wollen mentions is another value of classical cinema, but also allows the shot, the image, to convey a feeling of weakness, depression, and grief.

Lizzie Borden approaches counter-cinema for the purposes of feminist film criticism in her film “Born in Flames” (1983). In narrative cinema, as Baudry explains, differences must be effaced to create continuity. In “Rethinking Women’s Cinema”, Teresa De Laurentis praises “Born in Flames” for inscribing “differences among women as the differences within women” (150). Contrary to the idea of suppressing differences, the film displays the differences to endorse a heterogeneous community. It constantly addresses the spectator as a woman living at these times of social injustice. This direct call to the audience is where De Laurentiis believes reviewers find discomfort in the film. She states “the disappointment of not finding oneself, not finding oneself ‘interpellated’ or solicited by the film’ (155) positioning the subject in a position of self-aware spectatorship. For example, when Isabel, who operates Radio Ragazza, has introduced herself and the film’s main theme, she speaks directly to the audience telling them about “a tune you’ll be hearing an awful lot of these days, from the makers of our revolution”. This scene is placed at the beginning of the film to immediately invite the subject into the story but to also deny the experience of participation. The subject is held in the position of a viewer. The follow-up scene to Isabel’s introduction is tracking shot which captures women of different cultures in the working place. Starting with women in a grocery store scanning items at the register to an office with women sitting at their desks to a construction site. All the differences that make a heterogeneous community are displayed to construct the principal stance the film wishes to take on. Differences are part of life, they bring individuality and distinction among people. It is a concept we should embrace rather than negate.

Both “Funny Games” and “Born in Flames” are unique examples of how counter-cinema is used to bring attention to controversial topics. “Funny Games” utilizes foregrounding to convey feelings of helplessness while “Born in Flames” communicates directly with its audience to be self-aware of the issues the film wishes to discourse. Although the two films discuss a distinct subject matter, they both challenge the ideology of narrative cinema and are used as a powerful form of mass culture which carries awareness and knowledge for its audience.

3 notes

·

View notes