Photo

Great writing advice from Michael Moorcock.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Free Advice from Charlie Jane Anders

Free Advice from Charlie Jane Anders

Charlie Jane Anders has been posting great writing advice on io9 for years. I just wanted to make one page with links to every article for my use. But if you find it helpful as well, have at ‘er.

The Single Most Important Thing You Can Do To Make Your Writing More Awesome

I Wrote 100 Terrible Stories That I’m Glad You’ll Never Read

The Weirdest Stories Are Sometimes the Most Real

11 Ways to…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madman, Architect, Carpenter, Judge: a New Approach to Outlining

Madman, Architect, Carpenter, Judge: a New Approach to Outlining

Inspiration hides odd places at times. Like when Euripides took a bath and figured out what displacement was all about. Little epiphanies abound, waiting behind every corner, sometimes in groups of twos and threes, just waiting for us to stumble upon them. Case in point: I was giving some thought to setting up a sideline copyrighting business, so I Googled something like “professional business…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Year in a Day, and the Last Word on Writing Advice

A Year in a Day, and the Last Word on Writing Advice

Well hey there! I’m celebrating a peculiar anniversary today. A peculiarversary, if you will. It’s been a whole year since I last posted on this blog! Let’s see, what have we missed? I took a course in short story writing at U of T. It was great. I dedicated over seven months to polishing the story I wrote for that class. It’s awful, and I it will ever see daylight again. I had a birthday. I…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cruise the Universe from the Comfort of your Home

If you’re like me, you woke up this morning wondering what are three free programs that can help me explore the known universe and help me speculate about what we might find out there one day. Me, I had to do some research. You, you get to benefit from the fruits of my labor.

SpaceEngine is my fave. I used it to create the image above depicting what sunrise on a planet orbiting Betelgeuse might look like. The program lets you fly through the Universe giving you fairly detailed info on what we know and using procedurally-generated material to fill in the gaps we’re not so sure about. Big plus, you can land on planets to see what the sky might look like (best guess based on what we know already).

My second pick is NASA’s Eyes Visualization that gives you detailed info about Earth, the solar system, and the known exo-planets. If you’re looking for an interactive way to get up-to-date data about our galaxy, this is the way to go.

A third option is Celestia. I mention it more out of nostalgia than anything else--it was my first space-flight program--but it gives you a great way of visualizing how the constellations get distorted as you explore other planets. For instance, when viewing Orion from Proxima Centauri it appears to have picked up a new star with Sirius apearing right next to Betelgeuse (see below).

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Here’s the video mentioned in my post about the physics involved in space battles.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Space Battles Might Play Out if they had to Obey the Laws of Physics

I’m actually not brilliant enough to compile all these links, so I just stole them all from an It’s Okay to be Smart video (which I’ll include as a separate post).

It’s just some stuff to think about. I’m working on a lot of sci-fi ideas now, and some weird geeky part of me wants those ideas to be as scientifically accurate as possible.

Joseph Shoer has several extensive, in-depth articles on the physics of space warfare: http://josephshoer.com/blog/2009/12/t... http://josephshoer.com/blog/2010/07/p... Space warfare: Almost everything you know is probably wrong http://www.escapistmagazine.com/forum... Is space warfare really practical? http://www.escapistmagazine.com/forum... Zero-g dogfighting for dummies: http://www.citizenstarnews.com/news/z... Projectile weapons vs. directed energy weapons: http://forum.gateworld.net/threads/17... Nukes in space: http://www.projectrho.com/public_html... Effects of radiation weapons in space: http://www.projectrho.com/public_html... Could the Death Star really destroy a planet? http://www.universetoday.com/92746/co... "Sir Isaac Newton is the deadliest son of a b***h in space" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hLpgx...

Also, if you’re not already aware of it, the Writing and World Building section of Physics Forums is a great resource for writers who don’t want to offend the more learned among us by creating allegedly scientific fiction that seems more like magic (space ships that essentially behave like naval vessels in space, etc.). The crew there is open-minded and supportive and I highly recommend going there if you need any guidance in that department.

0 notes

Text

Don Roos’ Kitchen Timer Method

The principle of Kitchen Timer is that every writer deserves a definite and do-able way of being and feeling successful every day.

To do this, we learn to judge ourselves on behavior rather than content. (We leave content to our unconscious; experience will teach us to trust that.) We set up a goal for ourselves as writers which is easy, measurable, free of anxiety, and fail-proof, because everyone can sit, and an hour will always pass.

Here's how it works:

Buy a kitchen timer, one that goes to 60 minutes. [Or a timer app on your phone, etc.]

We decide on Monday how many hours of writing we will do Tuesday. When in doubt or under pressure or self-attack, we choose fewer hours rather than more. A good, strong beginning is one hour a day. The Kitchen Timer Hour

No phones. No listening to the machine to see who it is. We turn ringers off if possible. It is our life; we are entitled to one hour without interruption, particularly from loved ones. We ask for their support. "I was on an hour" is something they learn to understand. But they will not respect it unless we do first.

No music with words, unless it's a language we don't understand.

No internet, absolutely.

No reading.

No "desk re-design/landscaping", no pencil-sharpening.

Immediately upon beginning the hour, we open two documents: our journal, and the project we are working on. If we don't have a project we're actively working on, we just open our journal.

An hour consists of TIME SPENT keeping our writing appointment. We don't have to write at all, if we are happy to stare at the screen. Nor do we have to write a single word on our current project; we may spend the entire hour writing in our journal. Anything we write in our journal is fine; ideas for future projects, complaints about loved ones, even "I hate writing" typed four hundred times.

When we wish or if we wish, we pop over to the current project document and write for as long as we like. When we get tired or want a break, we pop back to the journal.

The point is, when disgust or fatigue with the current project arises, we don't take a break by getting up from our desk. We take a break by returning to the comforting arms of our journal, until that in turn bores us. Then we are ready to write on our project again, and so on. We use our boredom in this way.

IT IS ALWAYS OKAY TO WRITE EXCLUSIVELY IN OUR JOURNAL. In practice it will rarely occur that we spend the full hour in our journal, but it's fine, good, and right that we do when we feel like it. It is just as good a writing day as one spent entirely in our current project.

It is infinitely better to write fewer hours every day, than many hours one day and none the next. If we have a crowded weekend, we choose a half-hour as our time, put in that time, and go on with our day. We are always trying to minimize our resistance, and beginning an hour on Monday after two days off is a challenge.

When the hour is up, we stop, even if we're in the middle of a sentence. If we have scheduled another hour, we give ourselves a break before beginning again -- to read, eat, go on errands. We are not trying to create a cocoon we must stay in between hours; the "I'm sorry I can't see anyone or leave my house, I'm on a deadline" method. Rather, inside the hour is the inviolate time.

If we fail to make our hours for the day, we have probably scheduled too many. Four hours a day is an enormous amount of time spent in this manner, for example. If on Wednesday we planned to write three hours and didn't make it, we subtract the time we didn't write from our schedule for the next day. If we fail to make a one-hour commitment, we make a one-hour or a half-hour appointment for the next day.WE REALIZE WE CANNOT MAKE UP HOURS, and that continuing to fail to meet our commitment will result in the extinguishing of our voice.

When we have fulfilled our commitment, we make sure we credit ourselves for doing so. We have satisfied our obligation to ourselves, and the rest of the day is ours to do with as we wish.

A word about content: This may seem to be all about form, but the knowledge that we have satisfied our commitment to ourselves, the freedom from anxiety and resistance, and the stilling of that hectoring voice inside of us which used to yell at us that we weren't writing enough -- all this opens us up creatively.

Good luck!

13 notes

·

View notes

Quote

No worthy problem is ever solved within the plane of its original conception.

Albert Einstein, according to George Saunders

1 note

·

View note

Quote

The writer can choose what he writes about but he cannot choose what he is able to make live.

Flannery O'Connor

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it.

Albert Einstein

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

Meditation 101: A Beginner's Guide from Gobblynne on Vimeo.

Oh yeah, I keep forgetting to meditate!

2 notes

·

View notes

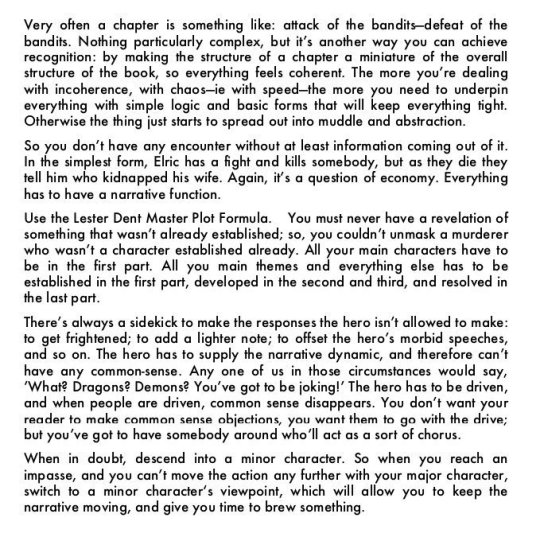

Photo

The proper order of adjectives. Guess I never thought about it that way before.

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

Fiction writers share a lot with those inventors. It’s not hard to get inspired by a great concept, to take it to your table or toolshed or cellar and do some brainstorming, and even to start putting the story on paper—but eventually, many of us lose traction. Why? Because development doesn’t happen on its own. In fact, I’ve come to think that idea development is the No. 1 skill an author should have.

How do great authors develop stunning narratives, break from tradition and advance the form of their fiction? They take whatever basic ideas they’ve got, then move them away from the typical. No matter your starting point—a love story, buddy tale, mystery, quest—you can do like the great innovators do: Bend it. Amp it. Drive it. Strip it.

Bend. Amp. Drive. Strip.

It’s BADS, baby, it’s BADS.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

I think that if there is any value in hearing writers talk, it will be in hearing what they can witness to and not what they can theorize about. My own approach to literary problems is very like the one Dr. Johnson's blind housekeeper used when she poured tea–she put her finger inside the cup. These are not times when writers in this country can very well speak for one another. In the twenties there were those at Vanderbilt University who felt enough kinship with each other's ideas to issue a pamphlet called, I'll Take My Stand, and in the thirties there were writers whose social consciousness set them all going in more or less the same direction; but today there are no good writers, bound even loosely together, who would be so bold as to say that they speak for a generation or for each other. Today each writer speaks for himself, even though he may not be sure that his work is important enough to justify his doing so....

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

More notes on Free Indirect Discourse”

What distinguishes free indirect speech from normal indirect speech is the lack of an introductory expression such as "He said" or "he thought". It is as if the subordinate clausecarrying the content of the indirect speech is taken out of the main clause which contains it, becoming the main clause itself. Using free indirect speech may convey the character's words more directly than in normal indirect, as devices such as interjections and psycho-ostensive expressions like curses and swearwords can be used that cannot be normally used within a subordinate clause. Deictic pronouns and adverbials refer to the coordinates of the originator of the speech or thought, not of the narrator.

Free indirect discourse can also be described, as a "technique of presenting a character's voice partly mediated by the voice of the author", or, in the words of the French narrative theorist Gerard Genette, "the narrator takes on the speech of the character, or, if one prefers, the character speaks through the voice of the narrator, and the two instances then are merged."

1 note

·

View note

Link

Free Indirect Discourse is essentially the practice of embedding a character’s speech or thoughts into an otherwise third-person narrative. In other words, the narrative moves back and forth between the narrator telling us what the character is thinking and showing us the character’s conscious thoughts, without denoting which thought belongs to whom. The result is a story that reads almost like it shares two “brains”: one belonging to the narrator, the other belonging to the character.

3 notes

·

View notes