Kat | she/her | adult | I'm also Swanhild on AO3 | Mostly a Silmarillion/general Tolkien blog these days

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Oh you’re a Tolkien expert? have u read letter 420 in which he described how much Sam loved eating Frodos ass on the daily? In the professors own words, he “devoured that hole like a jelly roll. that was basically Sam’s second breakfast the entire time they were in the undying lands, lulz (sic)” (letter to Tolkien’s publisher, 1969)

#omg I've never seen this before#I'm not even a hobbit shipper but still... fascinating#sam#frodo#samfro#jrrt

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Finrod stood beneath the sun, golden-haired and smiling — a fleeting peace upon the face of one born to sacrifice.”

392 notes

·

View notes

Note

Maybe a an Andreth?

I'm actually not taking request anymore, but i still had some half finished sketches that i finished up .

291 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Silmarillion playlist alert. This one is: Things Maedhros doesn’t want to be called.

380 notes

·

View notes

Text

hi my name is Nelyafinwë Maitimo Russandol Maedhros Feanárion and I have long copper red hair (that's how I got my name) with blood red tips that reaches past my butt and silver eyes like limpid tears and some people tell me I look like Finwë (AN: if you don't know who he is get da hell out of here!!) I'm related to Findekáno Astaldo Nolofinwion but I married him anyway cause we're Elves and he's a major fucking hottie. I may look like a vampire but I swear I'm not. I have pale white skin. I am also a Kinslayer, and I have killed many Elves in pursuit of the Silmarils of my father. I'm a goth, in case you couldn't tell, and I wear mostly red and black with a lot of star motifs. I love Hototyossë and buy all my clothes from there. For example today I was wearing black leather trousers, a dark red tunic like congealed blood with a small eight pointed star on each sleeve and high black boots and a black wool cloak embroidered with complex patterns and a copper circlet set with garnet. It was snowing so there was no sun and I wasn't happy about it. A lot of Eldar stared at me. I lifted my stump at them.

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

Take me back to the night we met

Also a first attempt to draw Baran and Belen, yey

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Tolkien event week for the Sindar, the Grey-Elves, from the Years of the Trees to the Third Age!

@sindarweek is a fandom event week celebrating the Sindar! It will be running from Monday September 8th 2025 to Sunday September 14th 2025.

Prompts (not mandatory, just inspirational):

Day 1: Early Days

Day 2: Ritual & Religion

Day 3: Women

Day 4: Rivers & Mountains

Day 5: Alternate Universes

Day 6: Magic & Craft

Day 7: Remembrance

Photo by Sergey Chuprin on Unsplash

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

Throwback Wednesday

dig up a snippet you're fond of and deserves revisiting

It was Nerdanel. Heart in his throat, Fëanor watched as she halted the horses and climbed down from the wagon. She caught his gaze, her dark eyes full of fire, and held it. Did not look away as she made her way towards him. Did not flinch even once. Fëanor could not move. Pinned in place, stuck with the ridiculous hat on his head and a bouquet of weeds in his hands, he could only stare at her. Nerdanel wore her work clothes, rough linen trousers and a large shirt, as though she’d decided to visit him on a whim. Her hair said otherwise, worn it up in an elaborate crown braid instead of her usual workshop bun. “Fëanor.” Like it had with her father, Sindarin sounded strange in her voice. “Nerdanel.” A miracle that her name came out of his mouth without breaking. “Hello.” “I have brought your pots.” Anger simmered beneath every word, her fists clenched at her sides. “Thank you.” Come inside, he wanted to say. Do not visit me if you are only going to taunt me, he wanted to yell. “Is your father well?” he said instead, because he could not imagine Mahtan letting Nerdanel visit unless something had gone wrong. “Yes,” she said. “I told him I wanted to see you. Alone.” Hope, as small and precious as a seed, took root in Fëanor’s heart. All could not be lost if she wanted to see him. Could it? He stood up, hoping that his legs would not shake. “I have wanted to see you as well.” Her eyes - the fire in them - cut into his heart. “You left.” “Yes.” “You took our sons.” “Yes.” Grief bled into the anger. “They are dead. All of them are dead, and so were you.” “I am sorry.” Such empty words, no matter the truth of them. “I did not want to come back without them.” “Are they - ” Nerdanel turned away, suddenly unable to look at him. “Are they well, in Mandos? Or did you damn our children to eternal darkness?” “They are in the Halls,” he said. That little piece of comfort, at least, he could give her. “They are no longer in any danger or pain.” Nerdanel nodded, her mouth pressed into a thin, hard line. Tears had filled her eyes and Fëanor watched as she struggled to push them back. He reached out for her hand. “Nerdanel - ” She jerked away. “Your pots are this way,” she said.

From Ruins We Grow

Thank you @melestasflight @sallysavestheday and @atlantablack for tagging me! In return, I tag: @dreamingthroughthenoise @chthonion @starspray @tathrin @lordgrimwing and whoever else wants to join in. No pressure, of course!

40 notes

·

View notes

Link

Chapters: 43/54 Fandom: The Silmarillion and other histories of Middle-Earth - J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings - J. R. R. Tolkien Rating: Teen And Up Audiences Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply Relationships: Maedhros & Maglor (Tolkien), Elrond Peredhel & Maglor, Celebrían/Elrond Peredhel, Elladan & Elrohir & Maglor (Tolkien), Daeron/Maglor (Tolkien), Elrond Peredhel & Maedhros, Celebrimbor & Maglor (Tolkien), Celebrían & Elladan & Elrohir & Elrond Peredhel, Maglor & Nerdanel (Tolkien), Finrod Felagund & Maglor, Finrod Felagund & Maedhros, Galadriel & Maglor (Tolkien), Fëanor & Maedhros (Tolkien), Fëanor & Maglor (Tolkien), Elrond Peredhel & Fëanor, Amras & Amrod & Caranthir & Celegorm & Curufin & Maedhros & Maglor (Tolkien), Fingon & Maedhros (Tolkien), Fingon & Maglor (Tolkien) Characters: Maglor (Tolkien), Daeron (Tolkien), Maedhros (Tolkien), Elrond Peredhel, Elladan (Tolkien), Elrohir (Tolkien), Celebrían (Tolkien), Celeborn (Tolkien), Galadriel (Tolkien), Original Cat Character(s), Original Characters, Celebrimbor (Tolkien), Fëanor (Tolkien), Sons of Fëanor (Tolkien), Nerdanel (Tolkien), Finrod Felagund, Eärendil the Mariner (Tolkien), Elwing (Tolkien), Fingon (Tolkien), Míriel Þerindë | Míriel Serindë, Huan (Tolkien), Gandalf (Tolkien), Elemmírë (Tolkien), Nienna (Tolkien) Additional Tags: Valinor in the Fourth Age of Arda (Tolkien), Family, Complicated Relationships, Brothers, Past Torture, Past Character Death, Sailing To Valinor, Tol Eressëa (Tolkien), Reunions, Reconciliation, Scars, Grief/Mourning, Trauma, Implied/Referenced Torture, Letters, Travel, Friends to Lovers, Angst, Drinking, Hurt/Comfort, Emotional Hurt/Comfort, Gandalf Meddles, the dead very gently haunting the narrative, Implied/Referenced Suicide, Hopeful Ending Series: Part 6 of meanwhile the world goes on Summary:

They passed out of Lhûn and the wider coastline of Middle-earth opened up before his eyes. He had wandered those shores for centuries, and even now he felt the pull of that same wanderlust, and knew he would miss them for the rest of his life. Their wildness, the untamed waves, the rocky shores and the cliffs and the sandy beaches. The gulls, and the dunes, and the tide pools with their ever-changing denizens. Someone began to sing a song of farewell, and other voices took it up. He did not join them.

Maglor keeps a promise and comes to Valinor, only to find the ghosts he thought he’d left behind are alive and waiting for him.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A young Anairë and Fingolfin 💙 I hc that she likes drawing and painting a lot

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

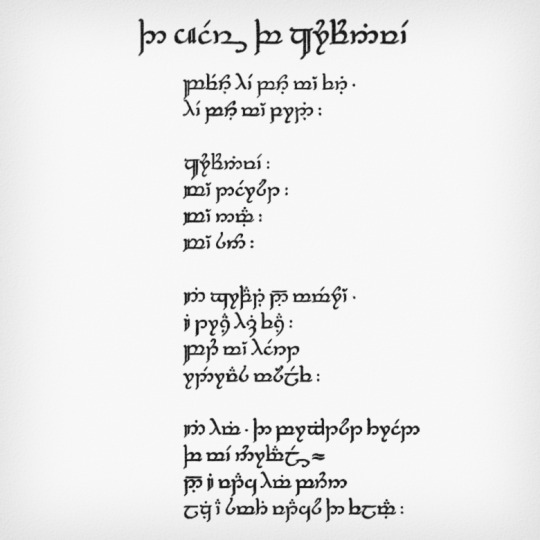

Sketches of Curufinwë Atarincë in Fëanor's journal. The poem reads: "The Years of Curufinwë" Before he bore my fire, He bore my pride. Curufinwë. My dearest. My name. My son. In graphite and memory, I trace his face. But my heart redraws myself. In him, the brightest thread of me unravels— And I watch him burn like a smith watches the flame.

#🥺🥺💙#something about fëanor drawing sketches of curvo (or all of his children really) over the years that really gets to me#curufin#feanor#silm art

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not even a feanorian apologist and i do think some of them are very annoying, but there's this certain subset of people who feel holier than though about not being one and constantly bitch and moan and sob about the feanorians having fans and like. I'm sorry you are just as goddamn annoying. instead of being so obsessed with what you're simply not into maybe just find something that brings you joy for a goddamn change. this is meant to be fun. are you even having fun. you sure do Not look like you're having fun. peace and love lmao

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Save the Date!

Nolofinwëan Week will return this year from November 2nd - 8th.

Prompts will be announced in the coming weeks; until then, let the heralds spread the word.

You can find the FAQ/Rules and Requirements here

If you have any questions, please don't hesitate to reach out!

I'm looking forward to a great event!

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Light has gotten enough momentum to trick Google's AI LLM into thinking Feanor and Fingolfin canonically make out. I think my purpose in life is done.🫡 I can die now. Take me, Namo Mandos. Send your call, I am ready.

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

“To demand from Elrond a clear adjudication of the Kinslaying at Sirion, a final pronouncement on whether the Fëanorians were monsters or misunderstood and whether his biological parents were 'right' or 'wrong', risks flattening the emotional and narrative density of his position. It treats historical violence as something that can be ethically settled by a perceived moral arbitrator, rather than something that continues to impact upon the present in ways that may remain unresolved.”

Part fandom-commentary and part literary-critical reading, this meta considers the interpretive ease with which Elrond’s "kind" disposition is conflated with moral coherence, particularly when it comes to treating his affective attachments to the Fëanorians and/or Elwing and Eärendil as absolute ethical verdicts.

Drawing on affect theory, trauma theory and adaptation analysis, I explore a way to read Elrond’s kindness as a cultivated practice which is not incapable of bias or harm. By reframing Elrond as a figure whose kindness arises from ambivalence rather than moral certitude, I try to offer a perspective that considers how 'virtue' is not an innate or fixed quality but one shaped by violence, grief, loss and the structural constraints of doctrine.

Read on the SWG or click 'Keep Reading'.

"Kind as Summer": Elrond’s Moral Framework and the Limits of 'Virtue'

As the master of Rivendell, bearer of Vilya, and participant in nearly every defining moment of Middle-earth's history, Elrond Half-elven is often read as a figure of moral clarity: wise counsellor, gentle healer, unimpeachable steward of continuity. This interpretive tendency is understandable. The House of Elrond is one of refuge and restoration. He acts without personal ambition and rarely raises his voice. Elrond himself is frequently described in the texts as "kind”, "wise”, "noble” and strong of spirit, categories which, in the moral architecture of Tolkien’s legendarium, can sometimes tend to collapse into one another.

Nowhere is the reverberation of this moral legibility clearer than with fanwork narratives (including my own writing, as well as its reception) centering the adult Elrond’s loyalties to either his kidnappers or his birth-parents. These interpretations can often rely on the assumption that Elrond’s emotional affiliations carry juridical weight: that his remembered loyalties serve as moral judgments, retroactively assigning guilt or innocence to those who shaped his early life.

If Elrond is depicted as maintaining affection for one or both of the oldest Fëanorian brothers, it is taken by some as a totalising absolution of their actions; if he is instead aligned solely with Elwing and Eärendil, it becomes an overarching indictment of his captors, or ‘proof’ of an abusive childhood with his kidnappers. And if he has mixed loyalties, then the moral scales are read to be tentatively balanced, weighted primarily by his reaction to or feelings about either party.

But such an interpretive logic can sometimes risk flattening the ethical ambiguity that Tolkien embeds into Elrond’s narrative arc. It treats Elrond as an ethical oracle, his loyalties read not as contingent and emotionally-influenced responses, but as narrative verdicts. What is elided in these moralised readings is Elrond’s long history of familial ambivalence: a shifting set of attachments forged by centuries of war and loss.

"Kind as Summer"

The phrase “kind as summer" is in itself deceptively simple, drawing its power from the dissonance between the lexical gentleness of “kind” and the seasonal ambivalence embedded in “summer.” On first encounter, the simile suggests warmth, growth and plenitude, a cliché of natural benevolence.

But summer is also a time of excess, and one that can be read in several ways, rather than through Tolkien's geographical location, authorial intent and belief system alone. For instance, if one were to do a postcolonial reading, summer takes on complex resonances that may instead signify exhaustion, drought, and resource extraction.

The phrase kind as summer therefore has the potential to hold within it a doubleness: kindness as a condition susceptible to circumstance. The warmth of summer is thus ambivalent, holding both potential and limitation. In this light, Elrond’s kindness appears less as an inborn gentleness and more as an atmospheric condition: natural, perhaps, but also shaped by cycles and histories not entirely in his control.

Section 1: The Ambivalence of 'Virtue'

My position is that Elrond's character complicates normative readings of virtue in Tolkien's world by illuminating the ways kindness can function as a moral aesthetic rather than a transformative ethic. Essentially, I want to interrogate the interpretive ease with which the phrase “kind as summer” is conflated with moral infallibility, particularly in paternal figures like Elrond. Kindness, in my reading, can be a mode of care shaped by fear, fatigue and political memory, and one absolutely capable of 'causing harm', whether intentional or otherwise. I read Elrond as a figure whose affective presence both stabilises and restricts the narrative worlds around him. His kindness is absolutely real. But it is also strategic, fatigued, and at times, obstructive. It's not that I see him as a failed moral exemplar; more a figure of ethical ambiguity.

I've noticed a tendency in contemporary literary interpretations [not specific to The Silmarillion] to equate the descriptor "kind" with an idealised, almost infallible figure, particularly in parental contexts: by itself a perfectly understandable and valid interpretation, and one dependent upon the individual. Within such a reading, a character like Elrond begins to be interpreted as the closest thing to a "gold-star" father and son, incapable of personal bias and lacking the ability to cause harm through his choices.

I want to first underscore that I'm not claiming Elrond is depicted as a cruel, unkind or abusive figure, very far from it. Moreover, this is not a question of cruelty masquerading as benevolence. The argument is not that Elrond weaponises kindness in the name of power. Rather, it is that authentic kindness may still operate through distortion, limitation, and strategic deployment. Kindness is a virtue, but virtues themselves are part of a contingent and historically situated ethical tradition: constructed, performed, and always vulnerable to the pressures of context.

And truly kind individuals within the space of fiction may still act anxiously, make misjudgments, or behave unwisely. Kindness does not render one immune to error or to the transmission of inherited harm. It is not, as it were, a prophylactic against failure. I view Elrond’s kindness as a cultivated posture: a way of navigating the traumas of the First and Second Ages without replicating their violences. And at the same time I believe it also serves as a defensive mechanism, a mode of affective containment. His care, at times, emerges less from trust than from apprehension, presenting an instinct to shield those he loves from the life he has endured.

There is also, I would suggest, an aesthetic dimension to this tension. We are conditioned to associate kindness with legibility: with emotional accessibility and moral ease. A character who is soft-spoken, emotionally literate, and reflective often becomes legible as "good" precisely because their tone aligns with our aesthetic preferences.

But this interpretive ease should be interrogated. What are the aesthetic codes through which we interpret kindness, and why do they so often elide contradiction? Why is Elrond, specifically, so often read as a model of pristine fatherhood and unbiased decision-making simply because his affect is calm and his language measured?

These aren’t questions meant to undermine his moral stature, but to open up space for a richer reading that allows for unpalatable emotions, ambivalence, and morally imperfect care. To reiterate: kindness is a virtue, and virtue is a theological construction. And this, in a text deeply intertwined with the form taken by the Western Catholic world-view in the early-mid 20th century, is worth exploring.

Section 2: Rivendell, Ritual, and Controlled Care

Kindness in Tolkien's work is often emblematic of moral certainty and goodness. Characters like Gandalf, Samwise, and Faramir are frequently described as "kind" in ways that imply inner moral coherence. But as Sara Ahmed puts it, kindness is not a moral category so much as an affective one. Kindness can be deeply sincere while also functioning ideologically: as a way of maintaining order, suppressing dissent, or preserving one's self-image. Kindness may look and feel good, but that does not make it ethically sufficient.

Elrond exemplifies this ambiguity. He is described as a master of wisdom, whose house was a refuge for the weary and the oppressed, a treasury of good counsel and wise lore. This characterisation of both Elrond and Rivendell signals hospitality, certainly, yet also formality, distance, and containment. Elrond’s kindness is architectural in both a literal and spiritual sense: it is built into the geometry of Rivendell, a beautiful, serene space governed by ritual, benevolence, and controlled access. It is a place of rest and sanctuary, but also of stasis.

This containment is not incidental. Rivendell is a sanctuary in the most theological sense, where healing is offered within a controlled environment, and where radical transformation is neither demanded nor structurally encouraged. Rivendell resembles, in this light, the Church-as-institution: a locus of consolation that also governs through procedure.

In drawing this analogy, we might return to Tolkien’s own Catholic intellectual formation, in which theological virtues like caritas (charity/kindness) are not autonomous affects but divinely structured orientations of the soul. As in, virtues that require cultivation, assent, and discipline. In Rivendell, healing and protection are not spontaneous nor inherent, they are administered. They flow downwards from Elrond as presiding moral authority and are extended through the formal mechanisms of counsel and rest, as grace is mediated through the sacraments.

But what, then, of those outside the covenant? What then, of those who transgress?

Section 3: Flawed Fatherhood in Adaptation

Interestingly, my thoughts on this topic started out not from the text itself but from adaptation. Namely, my partner remarking on Hugo Weaving’s Elrond during a rewatch: “I forgot how much this guy just… looms.”

And whilst I have criticisms of Peter Jackson’s representation of Elrond, namely in the flattening of his emotional complexity to a “protective patriarch” trope and the consequent (cinematically unexplained) hostility to Aragorn whom he canonically viewed as a son, I do think the adaptation interestingly illustrates the moral tension described in this essay, and how it engages with perceived transgression.

Hugo Weaving’s Elrond is a figure of grave restraint and moral distance. He's watchful, terse, and marked by a particular emotional economy that can sometimes border on detachment. His scenes with Arwen and Aragorn are defined by a fatigued, procedural kind of love shaped by prophetic loss. In these moments, his kindness becomes a politics of delay: his presence operating as a gatekeeping force, controlling the terms on which others are permitted to hope or act.

Rather than diminishing his character, this portrayal reveals the thematic complexity Elrond carries as a being who has lived long enough to doubt the usefulness of certainty and forward-movement. Importantly, Weaving’s performance does not resolve this ambivalence, but heightens it. His delivery is often clipped, curt and emotionally guarded but never without feeling. He oscillates between duty and disaffection, compassion and refusal.

This is particularly apparent in his interactions with Arwen, where his opposition to her choice is not simply paternal but fatalistic: he sees in her love a repetition of history’s cruelty, not its redemption. This dynamic reveals the deeper ambivalence of Elrond's ethical stance. His virtue is shaped by circumstance. But circumstance does not always sharpen moral attention. Sometimes it dulls it. His desire to shield Arwen from sorrow leads him to participate in a form of moral foreclosure. His filmic character gestures towards the costs of post-heroic care: the way kindness, when tasked with managing historical pain and potential loss, can become bureaucratic, strategic, and at times, emotionally ambivalent.

In his interaction with Gandalf during Fellowship, what might have been a moment of shared vulnerability instead becomes an act of controlled narration, Elrond weaponising not only personal memory but restricting interpretive access to it. The scene where Isildur takes the ring is described not through his own failure to stop Isildur or the allure and bind of the ring itself, but rather as evidence of the weakness of mortal men.

During the Council of Elrond, he delivers his historical exposition with a flat affect that diverges sharply from the accusatory grandeur of the tale he recounts to Gandalf. He does not seek to command, but to manage the emotional temperature of the room, which rapidly spirals into discord as tempers flare among the assembled parties. His silence in the face of this breakdown is telling; rather than intervene decisively as a ‘chair’, he allows the council to unravel until Frodo offers himself. Elrond’s position here is once again procedural and effective: he does not inspire, forbid or lead the Fellowship, but provides a static space within which others may act.

And the scene in The Return of the King where Arwen returns to Rivendell after choosing to forsake the Undying Lands is what I view as one of the few moments in Jackson’s trilogy where Elrond’s carefully maintained ethical posture collapses in on itself. He sees her as a living refutation of the moral architecture he has spent centuries constructing upon a framework of containment and emotional insulation. What Arwen’s return and the subsequent confrontation with loss forces upon Elrond is the ethical vertigo of having tried to forestall the loss in question. And I was intrigued by how Hugo Weaving played the moment as neither anger or even sorrow in the conventional sense, but as complete disorientation: pacing restlessly, quite literally brought to his knees, his usually measured expository cadence entirely fragmented.

His paternal care, shaped by personal suffering and a logic of prevention, is revealed as fundamentally incompatible with Arwen’s choice. And her “death drive”, when considered through the lens of The Silmarillion, seems inextricable from his past. Not only Elros' choice of mortality, no matter how extended, but also his traumatic engagements with Elwing and Maedhros: the two monumental suicide attempts that shaped his early life.

That incompatibility is not the product of malice, but of a deep structural disjunction that arises from Arwen having both been raised by Elrond, and raised in peacetime: his life is premised on prediction; hers on progression. For Elrond, kindness has long meant withholding, and nowhere is that clearer than his dialogue in The Tale of Arwen and Aragorn, specifically when directed to Aragorn: I love you, but, and the interesting deployment and withholding of the phrase my son throughout their conversations.

But that moment of Arwen's choice in the film is a rupture. Suddenly, there is no longer a future to delay toward.

This moment marks not Elrond’s moral failure, but the failure of moral architecture to hold against affective rupture. The reforging of Narsil which follows is an act of weary concession. Elrond yields not because he was self-centred up to that moment or because he believes the world can change, but because he no longer trusts the adequacy of restraint. His assent is a gesture of relinquishment. This is what it means, in Jackson’s rendering, to love after centuries of loss: to give what one no longer has faith in, because withholding it would be worse.

The cinematic Elrond emerges not as an archetype of immutable virtue, but as an ethically ambiguous figure whose kindness functions as a survival strategy. It is this tension between stability and control, foresight and fracture, paternal care and emotional containment that to me makes him such a compelling object of study. He destabilises the binary between good and failed fatherhood, and draws our attention to the structures through which kindness itself can become exhausted, procedural, and even wounding.

Elrond’s parenting, therefore, might best be read through the lens of the ethics of care, as theorised by figures such as Carol Gilligan and further elaborated by Judith Butler. His love for Arwen and Aragorn is unquestionable, but it expresses itself through limitation. He protects by narrowing possibility, and guides by withholding consent. This is not mere paternal conservatism; it is the logic of anticipated grief. Elrond’s love is shaped by the prior losses that haunt him, and as such, he comes to embody one of the most compelling figures within the ethics of care: the caregiver who, in seeking to protect, constrains the autonomy of the cared-for.

To read this incarnation of Elrond generously is not to absolve him of harm nor to idealise his restraint, but to recognise in his contradictions the broader thematic concern of Tolkien’s legendarium: that goodness cannot exist outside of history, and that virtue, however luminous, is always mediated by circumstance and doctrine. Likewise, to trouble Elrond’s kindness as being shaped by theological virtue and the politics of ritual containment is not to indict Elrond, but to understand him.

Section 4: The Living Archive

Elrond’s ethical disposition is inextricable from his orientation in "deep time". He is not merely long-lived but deeply embedded in history: the bearer of the First Age’s unhealed wounds and the steward of its consequences. He occupies a unique continuity between the mythic and the historical, bearing firsthand knowledge of events that to others have become legend.

But more significantly, he is positioned as a carrier of memory, a living archive of sorts, tasked with both remembering and also holding, curating, and transmitting the aftermaths of war, loss and failure. To embody such a long duration is to move beyond individual heroism and into a form of custodial ethic: what we might call, following Lauren Berlant, a “slow death” style of care, oriented toward preservation and endurance rather than rupture or transformation.

This temporal saturation renders Elrond’s ethical stance as procedural in the Foucauldian sense: embedded in and through institutions of knowledge and governance. Once again, Rivendell serves as a structure of historical management, offering its guests not transcendence but historical context and a temporal pause. In this light, Elrond’s ethical mode parallels the archive, which is no neutral repository but a site of selective preservation subject to omission and constraint. His moral authority derives from the ability to contextualise: to locate any present crisis within a longue durée of injury and consequence. This is not the virtue of the hero or the prophet, but of the historiographer, who governs through pattern recognition. His kindness, shaped by this ethic, becomes a mode of calibration: allowing others to act, but only after they have been properly situated within Arda’s framework of consequence.

Elrond, then, is not the moral compass of Middle-earth, but its ethical barometer.

And yet crucially, he continues to participate. This is where Elrond’s ethical significance truly lies: not in wisdom as mastery, but in wisdom as endurance. His kindness is shaped by and negotiated across a centuries-long encounter with failure, contradiction, and partial repair. He does not lead the revolution, but enables the conditions under which a new generation might, and operates despite the knowledge that such a utopian future would necessarily be one that excludes him and the historical baggage he both carries and represents.

Conclusion

Elrond occupies a unique space in Tolkien's moral architecture. He is neither tragic nor triumphant, saint nor cynic. He is in every sense an embodiment of the in-between: between races, between ages, between powers. His disposition is the ethical posture of someone who has lived too long to believe in unbroken things. And so to read Elrond only as kind is to miss the ethical ambivalence that sustains such a figuration. He is not good in the sense of moral perfection. Yet to me, he is most compelling in his complexity.

That Elrond could continue to carry both grief for his parents and a lingering loyalty to Maglor (and/or Maedhros, depending on fanwork interpretation) should not be read as evidence of a resolved moral position. Rather, it reveals the complex mechanics of affective survival: the way in which bonds forged under duress persist because they have become structurally inseparable from the self. Elrond’s ethical outlook is not built upon decisive acts of forgiveness or condemnation; it is sedimented through centuries of living through contradiction after contradiction. His emotional responses are residues: remnants of a life shaped by the impossibility of full redress.

And so to demand from Elrond a clear adjudication of the Kinslaying at Sirion, a final pronouncement on whether the Fëanorians were monsters or misunderstood, whether his biological parents were 'right' or 'wrong', risks flattening the emotional and narrative density of his position. It treats historical violence as something that can be ethically settled by a perceived moral arbitrator, rather than something that continues to press upon the present in ways that remain unresolved.

His potential attachments to both his origins and his upbringing are signs of someone who has lived with too much loss to believe that care and harm are ever cleanly separable. He carries both because to let either go could mean severing part of the self that survived. His kindness is no higher virtue forged above the maelstrom: Elrond is a character shaped by the violence of history, not despite it.

Head to the SWG for a works cited/further reading list.

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

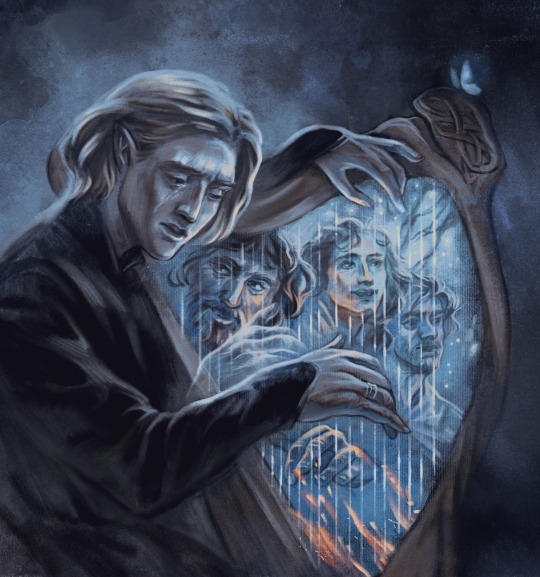

Maglor's little star, tormented and longing for his family for jc-vanimia ✨

Elrond and Maglor

972 notes

·

View notes

Text

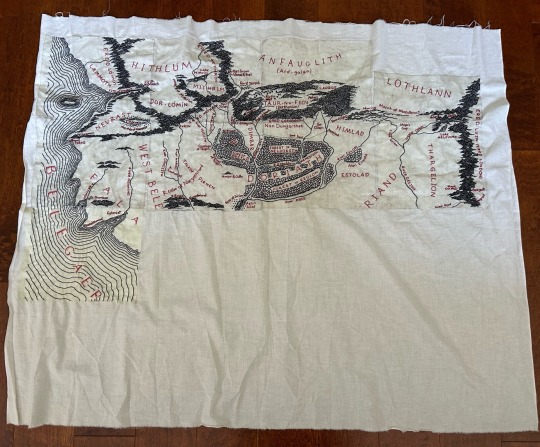

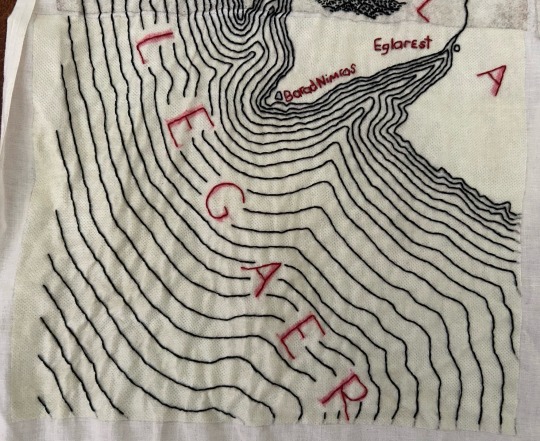

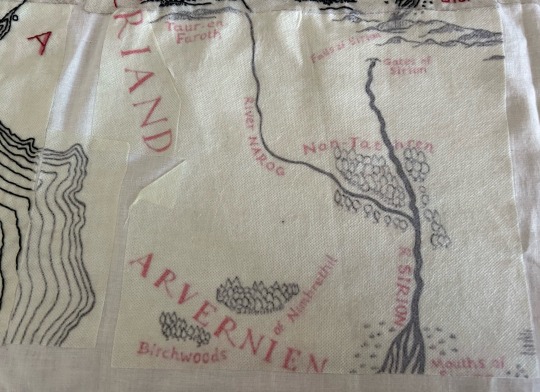

Panel 9 is done! Thanks to a combination of there only being the sea (so much simpler to stitch!) and wonderful weather to sit on my balcony and just get lost in the crafting zone, it got completed far quicker than expected.

Now for Panel 10! There was a tiny issue in sizing so I had to cut up a few pieces and puzzle them in, but the pattern paper will all get washed away at the end anyway so it’s all good.

220 notes

·

View notes