#1560s Italy

Text

Red silk doublet and breeches, 1562, Italian.

Worn by Garzia de Medici.

Uffizi Gallery.

#uffizi gallery#red#extant garments#silk#menswear#1562#1560s#doublet#breeches#1560s doublet#16th century#1560s Italy#Italy#1560s menswear#1560s breeches#Garzia de Medici

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of a lady by Prospero Fontana, 1565-70

44 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've seen a post you've reblogged and added to, among many things about women showing nipples. Can you recommend any ref material (articles, videos, etc.) are share your knowledge about this? Cause I'm curious about that, as nowadays going out in a shirt without a bra makes you indecent, while in like 90s it was okayish? I wonder how it was in previous centuries.

There is a really cool academic paper about bare breast dresses in 17th century England specifically. I think anyone can read it by creating a free account.

Abby Cox also has a good video about the cleavage during the past 500 years in which she goes through also the nip slip phenomena.

I don't have other sources that specifically focus on this subject, though many sources about specific decades touch on it, but I do have my primary source image collection, so I can sum up the history of the bare nipple.

So my findings from primary source images (I could be wrong and maybe I just haven't found earlier examples) is that the Venetians were the first ones to show the nipple for courtly fashion. At the same time in other places in Europe they sported the early Elizabethan no-boob style that completely covered and flattened the chest. In the other corners of Italy the necklines were also low but less extreme. Venetian kirtle necklines dropped extremely low as early as 1560s and they combined extremely sheer, basically see-through partlets with their kirtle. First example below is a 1565-70 portrait of a Venetian lady with the nipples just barely covered waiting slip into view with a movement of arm. There was an even more extreme version of this with the kirtle being literally underboob style, still with a sheer doublet. Though I believe this was not quite for the respectable ladies, since I have only seen it depicted on high class courtesans. They were not exactly respectable ladies, but they did have quite good social position. The second example is a 1570s depiction of a courtesan, which is revealed by the horned hairstyle. By the end of the century this underbust style with only see through fabric covering breasts, had become respectable. In the last example it's shown on the wife of the Venetian doge in 1597.

Around the same time, at the very end of 1500s, the extremely low cut bodice fashion enters rest of Europe. The low cut style was present in the bodices of all classes, but the nipple was really only an aristocrat thing. The lower classes would cover their breasts with a partlet, that was not sheer. Bare breast was ironically from our perspective a show of innocence, youthful beauty and virtue, and to pull off the style with respect, you also had to embody those ideals. Lower class women were considered inherently vulgar and lacking virtue, so a nipple in their case was seen as indecent. Bare boobs were also a sort of status symbol, since the upper class would hire wet nurses to breastfeed their children so they could show of their youthful boobs.

Covering partlets and bodices were still also used in the first decade of 1600s by nobles and the nip slip was mostly reserved for the courtly events. The first image below is an early example of English extremely low neckline that certainly couldn't contain boobs even with a bit of movement from 1597. The 1610s started around 5 decades of fashion that showed the whole boob. The first three were the most extreme. Here's some highlights: The second image is from 1619.

Here the first, very much showing nipples, from c. 1630. The second from 1632.

The neckline would slowly and slightly rise during the next decades, but nip slips were still expected. Here's an example from 1649 and then from 1650-55. In 1660s the neckline would get still slightly higher and by 1870s it was in a not very slippable hight. The necklines would stay low for the next century, though mostly not in boob showing territory, but we'll get there. But I will say that covering the neckline in casual context was expected. Boobs were mostly for fancy occasions. It was considered vain to show off your boobs when the occasion didn't call for it and covering up during the day was necessary for a respectable lady. You wouldn't want to have tan in your milk-white skin like a poor, and also they didn't have sun screen so burning was a reasonable concern.

1720s to 1740s saw necklines that went to the nip slip territory, though they didn't go quite as low as 100 years earlier. The nipple was present in the French courtly fashion especially and rouging your nipples to enhance them was popular. Émilie Du Châtelet (1706-1749), who was an accomplished physicist and made contributions to Newtonian mechanics, was known in the French court to show off her boobies. An icon. Here she is in 1748. Here's another example from this era from 1728.

The Rococo neckline never got high, but in the middle of the century it was less low till 1770s when it plunged into new lows. In 1770s the fashion reached a saturation point, when everything was the most. This included boobs. The most boob visible. There was a change in the attitudes though. The visible boob was not a scandal, but it was risque, instead of sing of innocent and did cause offense in certain circles. I think it's because of the French revolution values gaining momentum. I talked about this in length in another post, mostly in context of masculinity, but till that point femininity and masculinity had been mostly reserved for the aristocracy. Gender performance was mostly performance of wealth. The revolutionaries constructed new masculinity and femininity, which laid the groundwork for the modern gender, in opposition to the aristocracy and their decadence. The new femininity was decent, moral and motherly, an early version of the Victorian angel of the house. The boob was present in the revolutionary imagery, but in an abstract presentation. I can't say for sure, but I think bare breasts became indecent because it was specifically fashion of the indecent French aristocracy.

Here's example somewhere from the decade and another from 1778. The neckline stayed quite low for the 1780s, but rose to cover the boobs for the 1790s.

The nipple didn't stay hidden for long but made a quick comeback in the Regency evening fashion. It was somewhat scandalous by this point, and the nipple and sheer fabrics of the Regency fashion gained much scorn and satire. The styles that were in the high danger nip slip territory and those that allowed the nipple to show through fabric, were still quite popular. The sleeves had been mid length for two centuries, but in 1790s they had made a split between evening and day wear. The evening sleeves were tiny, just covering the shoulder. Showing that would have been a little too much. Like a bare boob? A risque choice but fine. A shoulder? Straight to the horny jail. (I'm joking they did have sheer sleeves and sometimes portraits with exposed shoulder.) But long sleeves became the standard part of the day wear. Getting sun was still not acceptable for the same reasonable and unreasonable reasons. Day dresses did also usually have higher necklines or were at least worn with a chemisette to cover the neckline. Fine Indian muslin was a huge trend. It was extremely sheer and used in multiple layers to build up some cover. There were claims that a gust of wind would render the ladies practically naked, though because they were wearing their underclothing including a shift, which certainly wasn't made from the very expensive muslin, I'm guessing this was an exaggeration. Especially though in the first decade, short underboob stays were fairly popular, so combined with a muslin, nipples were seen. Here's an early 1798 example of exactly that. The short stays did disappear eventually, but in 1810s the extremely small bodices did provide nip slip opportunities, as seen in this 1811 fashion plate.

Victorian moralizing did fully kill the nip slip, though at least they were gender neutral about it. The male nipple was just as offensive to them. In 1890s, when bodybuilding became a big thing, bodybuilder men were arrested for public indecency for not wearing a shirt.

#there was also the new femininity aspect to regency nipple which had to do with breastfeeding becoming fashionable among upper class#it's about the whole motherly thing that came with the french revolution#i can't remember the book i read it from so i didn't go into it because i couldn't remember the details lol#but it did definitely have an effect to the fashion and to the perception of nipple#historical fashion#fashion history#history#dress history#fashion#answers#painting#fashion plate#renaissance fashion#elizabethan fashion#rococo fashion#baroque fashion#regency fashion#will tumblr prove itself to be again more prudish than elizabethans and label my post as mature content?#remains to be seen

504 notes

·

View notes

Text

K I N G S I D E, a tale of seven kings

first season 1514-1520. Claude and François finally get married, a vacant seat for Mary Tudor, Louise of Savoy's stubborness to keep her son in check. A new King arises, the New Order, François' quest for glory in Italy. Another crown, another campaign.

second season 1522-1530. The inheritance dispute that leads Bourbon to treason. The pursuit of the italian dream, Claude dies, all is lost in Pavia. Süleyman and the unthinkable alliance, captivity in Spain. The Ottoman fleet. Royal depression. The inheritance dispute that led Bourbon to treason. The ladies' peace, Henry VIII flinching, a price for two princes, a New wife for the King.

third season 1531-1537. Louise dies, tensions between François and Marguerite. The wedding of Catherine and Henri. The rise of Pisseleu, the battle at Court between Charles and Henri and their people. War between Diane and Montmorency. Placards and the anti-heterics frenzy, another war in Italy. Wedding and death of Madeleine.

fourth season 1539-1547. Mending tensions between France and Spain. A very stubborn niece. All eyes on Henri and Catherine's sterile womb. Death of Charles. The duel in Jarnac. The King is dead, long live. Diane de Poitier's absolute triumph over Anne de Pisseleu. The Guises make their move.

fifth season 1553-1559. Diane of France's not so typical royal wedding. Catherine giving birth to the twins, Chenonceau goes to Diane, the cordial hate between the two. Rohan VS Nemours. Montmorency mess and a remarriage for Diane of France. The death of Henri, everything falls down.

sixth season 1560-1564. François II barely hanging on, Catherine's almost giving up, Elisabeth married off, the Guise family's counterpower, Montemorency's political exile, the Amboise conspiracy, preparations for the grand tour.

seventh season 1565-1572. The end of the grand tour, encounter between the royal family and Elisabeth, queen of Spain. The rise of Charles IX, a new queen, Marie Touchet and her bastard boys. Catherine's plans to get a match for Marguerite. Rising tensions between Charles and Henri after Jarnac and Montcontour. Marguerite's nuptials amidst tensions and Coligny's attempted murder.

eighth season 1572-1575. Coligny and the Protestant leaders rallying the troops. The Saint Barthelemew Massacre and the promise of Marguerite to never forgive her family. Catherine finds out Anjou's possible involvement. A new king for Poland. Marguerite's toubled married life. Death of Charles IX. Henri's escape from Poland and slow return to France.

nineth season 1581-1584. Catherine's illusions shatter. New King, no heir. Marguerite returns to Paris. Louise shows some spine against the King's favorites. Quarelling with Anjou, tensions with Elizabethan England, Anjou's election and subsequent death and Catherine's anger. The Guise family veering off the road.

tenth season 1585-1589. The mounting war of the three Henris. All eyes on King Henri who has no sons, Catherine's political exile, the slow burning of the last Valois children. Hunting down Marguerite from stronghold to stronghold, ending with her house arrest in Usson. Assassination of the Guise brothers, the death of Catherine, Henri III breaks down in Diane's arms. Marguerite in exile, Diane the only "true" daughter of Catherine's, as she sets out to (successfully) pacify the kingdom on her own.

#historyedit#perioddramaedit#mine#*#*kingside#16th century#so yeah this took me a whole month instead of a good week#we love crappy laptops

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sword crafted in Milan, Italy, circa 1560-1570

from The Louvre

348 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The “Morosini Helmet,” a lavishly embossed blue and gilt parade Burgonet,

Height: 12 in/30.5 cm

Width: 9.2 in/23.3 cm

Depth: 13.9 in/35.4 cm

Milan, Italy, 1550-1560, housed at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

#armor#armour#helmet#burgonet#europe#european#italy#italian#milan#milanese#renaissance#nga#art#history

674 notes

·

View notes

Text

1) Burgonet of Philip II, Northern Italy, c. 1560–1565

Medium: gold- and silver-damascened steel, fabric

⠀

2) Shield, Milan, c. 1565–1570

Medium: gold- and silver-damascened steel, leather, fabric

⠀

Ancient wars were a popular subject for Renaissance parade armor, as on this shield and burgonet depicting scenes from the Trojan War.

⠀

The left side of the helmet shows the Judgment of Paris, the Trojan prince who declared Aphrodite the most beautiful goddess after she promised him Helen, wife of the king of Sparta.

⠀

On the right side, Trojans tear down part of their city walls to make way for the huge Trojan horse in which Greek warriors were hidden. Paris’ abduction of Helen and the Greeks’ departure for Troy appear in the center of the shield.

⠀

🏛 Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid

⠀

- -

1) Бургиньот Филиппа II, Северная Италия, ок. 1560–1565 гг.

Материалы: Сталь, дамаскирование золотом и серебром, ткань.

⠀

2) Щит, Милан, ок. 1565–1570 гг.

Материалы: Сталь, дамаскирование золотом и серебром, кожа, ткань.

⠀

Древние войны были популярной темой для парадных доспехов эпохи Возрождения, как на этом щите и бургиньоте: сюжет со сценами Троянской войны.

На левой стороне шлема изображен Суд Париса, троянского принца, объявившего Афродиту самой прекрасной богиней после того, как она пообещала ему Елену, жену царя Спарты.

⠀

На правой стороне - троянцы сносят часть городских стен, чтобы освободить место для огромного троянского коня, в котором прятались греческие воины. Похищение Парисом Елены и уход греков в Трою изображены в центре щита.

⠀

🏛 Королевская Оружейная палата в Мадриде

⠀

#armsandarmor #medievalarmour #armour #knight #armor #armure #harnisch #harness #armatura #armadura #Burgonet #Philip_II #Бургиньот #Филипп_II #Shield #щит

#medieval#средневековье#middleages#history#armor#armours#история#harnisch#armadura#armour#бургиньот#burgonet

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Salt-cellar, gilt bronze, male figure supporting a shell, Italy, about 1560

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

CEREMONIAL RAPIER.

Italy, c. 1550 - 1560. Neue Burg, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Austria.

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red Velvet Dress, ca. 1560, Italian.

Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Reale, Pisa.

On Loan to Met Museum.

#met museum#museo nazionale di palazzo reale Pisa#extant garments#velvet#womenswear#16th century#fave#dress#red#italian#italy#1560s#1560#1560s Italy

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

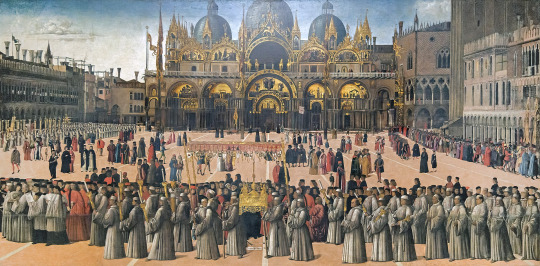

Countries that are no more: Republic of Venice (697AD-1797AD)

The first in a series I hope to feature on providing high level overviews of countries that existed and were influential to history or obscure and lost to most memory in time. The first up is the Republic of Venice.

Name: Serenisma Republega de Venesia (Venetian). In English this translates to the state's official name The Most Serene Republic of Venice. Also referred to as the Venetian Republic, Republic of Venice or just Venice.

Language: The official languages were the Romance languages of Latin, Venetian & later Italian. The regional dialect of Vulgar Latin in Northeastern Italy known as Veneto was the original language of Venice. This evolved in Venetian which was attested to as a distinct language as early as the 13th century AD. Venetian became the official language and lingua franca of the everyday Venetians and across parts of the Mediterranean although Latin would still be used in official documents and religious functions. Overtime, modern Italian was spoken in Venice though the Venetian language remains technically a separate language in Italy's Veneto region and the surrounding areas to this day.

Minority languages across the republic's territory included various Romance languages such as Lombard, Friulian, Ladin, Dalmatian and non-romance languages such as Albanian, Greek & Serbo-Croatian.

Territory: The republic was centered on the city of Venice founded in the Venetian lagoon on the north end of the Adriatic Sea to the northeast coast of the Italian peninsula. It also included the surrounding regions of mainland northeast Italy in the regions of Veneto and Friuli and parts of Lombardy. This became known as the terraferma or the mainland holdings of the republic. It also possessed overseas holdings in modern day Croatia, Slovenia, Montenegro, Albania, Greece & Cyprus.

Symbols & Mottos: The main symbol of Venice was its flag which had the famed Winged Lion of St. Mark. This represented the republic's patron saint, St. Mark. Mark the Evangelist after whom the Gospel of Mark in the New Testament in the Bible is named. Mark's body and holy relics were taken by Venice and said to be housed in the Basilica di San Marco (St. Mark's Basilica) in Venice itself. Variations of this flag differed during times of peace & war. During peace the winged lion is seen holding an open book and during war flags depicted the lion with its paw upon a bible and an upright sword held in another paw.

The republic's motto in Latin was "Pax tibi Marce, evangelista meus" or in English "Peace be to you Mark, my evangelist."

Religion: Roman Catholicism was the official religion of the state but Venice did have minorities of Eastern Orthodox & Protestant (usually foreign) Christian denominations at times in its territory and it also had small populations of Jews and Muslims to be found in Greek and Albanian territories during the wars with the Ottoman Empire.

Currency: Venetian ducat and later the Venetian lira.

Population: Though population varied overtime for the republic due to a variety of factors such as war & changing territory and disease & its subsequent effects. There was rough population recorded of 2.3 million people across all of its holdings in the mid sixteenth century (circa 1550-1560). The vast majority of its population was found in the terraferma of northern Italy and the city of Venice itself with its concentrated population on the islands within the Venetian Lagoon. The Greek island of Crete and the island of (Greek speaking) Cyprus were the most populous overseas possessions of the republic's territory. The rest of the population was found its various holdings in the Balkans mostly along the Adriatic coastline.

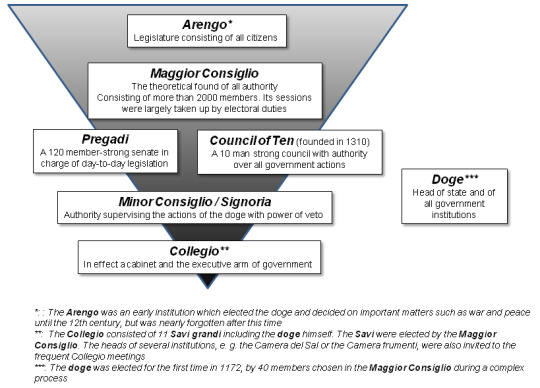

Government: The republic followed a complex mixed model of government. Essentially it could be characterized as a mixed parliamentary constitutional republic with a mercantile oligarchy ruling over it in practice. It had no formal written constitution, and this led to a degree of evolution without exactly defined roles often in reaction to happenings in its history. The resulting government became more complex overtime as institutions became increasingly fragmented in their size, scope and duties, some almost obsolete but still retained and others not fully defined. Yet, the republic managed to function quite well for most of its history. It incorporated elements of oligarchy, monarchy & limited democracy.

It's head of state and government was known as the Doge which is akin to the term of Duke. Though this similarity of name ends there. The Doge was neither similar to a duke in the modern sense nor was it meant as a hereditary position. The doge was rather a lifetime appointment much like the Pope for the Roman Catholic Church. Furthermore, doges were elected by the ruling elite of Venice, namely its wealthy oligarchy merchant class. The doge didn't have well defined & precise powers throughout the republic's 1,100-year history. It varied from great autocracy in the early parts of the republic to increasing regulation and restriction by the late 13th century onward. Though the doge always maintained a symbolic and ceremonial role throughout the republic's history. Some doges were forcibly removed from power and post-1268 until a new doge could be elected, the republic's rule transferred to the most senior ducal counsellor with the style of "vicedoge". After a doge's death following a commission was formed to study the doge's life and review it for moral and ethical transgressions and placed judgment upon him posthumously. If the commission found the deceased doge to have transgressed, his estate could be found liable and subject to fines. The doge was given plenty of ceremonial roles such as heading the symbolic marriage of Venice to the sea by casting a marriage ring into the sea from the doge's barge (similar to a royal yacht). Additionally, the doge was treated in foreign relations akin to a prince. It's titles and styles include "My Lord the Doge", "Most Serene Prince" and "His Serenity". The doge resided in the ducal palace (Palazzo Ducale) or Doge's Palace on the lagoonfront in Venice next St. Mark's Basilica and St. Mark's Square.

While the doge remained the symbolic and nominal head of the government, the oligarchy remained supreme overall. The supreme political organ was the 480-member Great Council. This assembly elected many of the office holders within the republic (including the doge) and the various senior councils tasked with administration, passing laws and judicial oversight. The Great Council's membership post 1297 was restricted to an inheritance by members of the patrician elite of the city of Venice's most noble families recorded in the famed Golden Book. This was divided between the old houses of the republic's earliest days and newer mercantile families if their fortunes should attain them property ownership and wealth. These families usually ranged between 20-30 total. They were socially forbidden from marrying outside their class & usually intermarried for political and economic reasons. Their economic concerns were chief to the whole of the republic and most centered on Eurasian & African trade throughout the Mediterranean Sea's basin. Members of these families served in the military and eventually rose to prominent positions of administration throughout the republic.

The Great Council overtime circumscribed the doge's power by creating councils devoted to oversight of the doge or executive and administrative functions (similar to modern executive cabinets or departments) whereas the doge became more and more a ceremonial role. The also created a senate which handled daily legislation. They also created a Council of Ten set to have authority over all government action. Other bodies were formed from this Great Council and others overtime. This resulted in intricate and overlapping yet separate bodies which found themselves subject to limitations with various checks on virtually each other's power. Essentially running as committees or sub-committees with checks on another committee's powers. These bodies weren't always completely defined in their scope and overtime their complexity led to battles to limit other's power (with limited success) along with gradual obsolescence and sometimes slow grinding administration.

Military: The military of Venice consisted of a relatively small army and a powerful navy. The famed Venetian Arsenal in Venice proper was essentially a complex of armories and shipyards to build and arm Venice's navy. The arsenal in Venice has the capacity to mass produce ships and weapons in the Middle Ages, centuries before the Industrial Revolution allowed for modern mass production in economic and military applications. Venice's military was designed towards protecting it possessions both in Italy and its overseas territories. The primary concern was to secure Venice's trade routes to the rest of Europe as well as Asia & Africa. It faced opponents' overtime ranging from the Franks, the Byzantine Empire, Bulgarians to other Italian city-states, France, Austria, the Ottoman Empire and Barbary Corsairs along with European pirates in the Adriatic and Mediterranean. It played key roles as a naval transport in other powers including throughout the Crusades. It also played a key role in the infamous Fourth Crusade which culminated in the Sack of Constantinople in 1204 AD, an event which fractured the Byzantine Empire into a half-century of civil war between successor states before a weakened revival in the mid 13th century. The Byzantine Empire would linger until the 15th century when the Ottoman Empire finally conquered its last remaining portions. Many attribute this loss to in part to its weakness still resulting from that 1204 sack lead by Venice. The Venetian military would exist until the republic's end when The French Republic's Army of Italy under Napoleon Bonaparte conquered the republic, a conquest in which the Venetians surrendered without a proper fight.

Economy: Venice's economy was based largely in trade. Namely control over the salt trade. Venice was to control salt (preservative of food) production and trade throughout the Mediterranean. It also traded in commodities associated with the salt trade routes to Eurasia and Africa. These commodities could include other foodstuffs (grains, meats & cheeses), textiles & glassware among other items.

Lifespan: 697AD-1797AD. Though the exact founding of Venice itself hasn't been determined. It is traditionally said to have taken place in the year 421 AD. At a time when Roman citizens in northeast Italy were escaping waves of Germanic & Hunnic barbarian invasions that contributed to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. The going theory is that these Romans evaded barbarian attacks by building their homes in the Venetian Lagoon by hammering wood stakes to form a foundation which sunk into the muddy shallows and petrified. Upon which they built their homes and created a cityscape marked by streets and canals interlaced. Venice remained a community of fishermen and merchants and was nominally under the control of the surviving Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire). It avoided barbarians overrunning the land but also was removed enough from Constantinople that it was relatively autonomous and became strategically important as a port. Other islands in the lagoon also banded together with Venice in a loose confederation of sorts by the 6th and 7th centuries which increased economic productivity and security for the city. The first doge was said to have been elected in 697 AD under the name Paolo Lucio Anafesto, though there is dispute about his historicity. Anafesto supposedly ruled until 717 AD. This is traditionally regarded as the foundation of the Republic of Venice.

Venice's third doge was Orso Ipato who reigned from 726-737 and he is the first undisputed historically recorded doge whose existence was confirmed. Orso also known as Ursus was known to strengthen the city's navy and army to protect it from the Lombard Germanic invaders who had overrun and ruled Italy by that time. Though nominally part of the Byzantine Empire, by 803, the Byzantine Emperors are said to have recognized Venice's de-facto independence. Though this view is disputed somewhat, it nevertheless remained virtually independent until its collapse in 1797.

Venice also partook in the slave trade of non-Christian European populations from Eastern Europe and transferred them to North Africa, selling them to the Arab and Berber (Moors) of the Islamic world.

As the 9th century progressed, the Venetian navy secured the Adriatic and various trade routes by defeating Slavic and Muslim pirates in the region. The Venetians also went onto battle the Normans who settled in southern Italy and Sicily in the 11th century.

Venice provided naval transports for Crusaders from Western Europe starting with the successful First Crusade.

The High Middle Ages (1000AD-1350AD) saw the wealth and expansion Venice increase dramatically. However, over this period Venice gradually came into mixed relations with its former ruler the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire endured corruption, civil war and foreign invasion which saw it alternate between periods of waning power and restored power. Venice provided the Byzantines with an increased naval force when needed and many trading commodities. In exchange for this, Venice was granted trading rights within Byzantine territory and a place within the "Latin Quarter" for Western Europeans in Constantinople. The Byzantine populace though calling themselves "Romans" having taken on the political & cultural institutions of the Roman Empire which lived on in the East long after the Western half's collapse, were in fact mostly Greek by ethnicity, language and culture. Their religion was the Eastern Orthodox or Greek Orthodox branch of Christianity which was often at odds with Roman Catholics of Western Europe. Resentment at the religious and cultural differences along with the economic displacement the Venetians and other Italian merchants from Genoa & Pisa had caused in Constantinople's maritime & financial sectors contributed to the 1182 "Massacre of the Latins" in which the Byzantine Greek majority of the city rioted and slaughtered much of the 60,000 mostly Italian Catholics living within the city. Thousands were also sold into slavery to the Anatolian Seljuk Turks.

This event lingered in Venice's memory as its trade in the city was reduced for awhile. Though trade resumed between the Byzantines and the West again shortly thereafter, the event soured the perception of the Greeks to Western Europeans. This along with a subsequent power struggle for the throne of the Eastern Roman Emperor fell into Venice & Western Crusader's hands in 1202. Looking to originally ferry Western Crusaders to the Levant against the Islamic Ayyubid Sultanate of Egypt & Syria. Events transpired that devolved into Venice conspiring under its doge Enrico Dandalo along with other Western leaders and a Byzantine claimant to the throne that resulted in the first successful sacking of Constantinople in 1204. The city was ransacked, some Greek citizens murdered by the Crusaders & classical works of art destroyed or looted (most famously the four bronze horses of St. Marks in Venice) and politically, the Byzantine Empire would be temporarily fractured between competing Greek dynasties while the Crusaders along with Venice created the short-lived Latin Empire, which controlled Constantinople and its environs while Venice also acquired Greek territories which it was to hold for centuries. Venice also came into conflict with the Second Bulgarian Empire at this time as its support of the Latin Empire of Constantinople encroached on the Bulgarian's land. Eventually by the mid 13th century the Latin Empire (never fully stable) collapsed, and the Byzantine Empire was restored until the mid-15th century but forever weakened as a result of the 1204 sacking of its capital.

Venice reached trade deals with the Mongol Empire in 1221. As the century wore on, it also engaged its rival in Western Italy Genoa in some warfare.

The 14th century is generally regarded as Venice at its peak as it faced down Genoa in a number of battles and came to be the most dominant trading power in the Mediterranean, though it was impacted by the Black Death plague. Nevertheless, into the 15th and even 16th centuries, it partook in a number of wars which saw it gain territory on the Italian mainland, establishing its terraferma domain.

By the 16th late 15th and into the 16th century new threats had emerged such as the Turkish Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman capture of Constantinople in 1453 is seen as the end of the Middle Ages as the last political vestiges of the Roman Empire vanished from the world stage. However, a number of Byzantine Greeks escaped on Italian ships during the conquest of the city and others escaped Greece in subsequent years. These refugees brought with them artistic and cultural heritages that reemphasized the classical forms of Ancient Greece and Rome and lead to the Italian Rennaisance in art & other forms of culture. Ideas which emphasized humanism and spread to elsewhere in Europe overtime.

While there was a cultural flourishing in Venice and elsewhere due to the Rennaisance. There was also the first signs of economic and political decline as well from the 16th century onwards. The Ottoman dominance in the Eastern Mediterranean meant the traditional trade routes to the East were cut off by an often-hostile Muslim power. Additionally, other maritime powers in the West namely Spain & Portugal had recently begun exploring the continents of South & North America and in time France, England & the Netherlands would join in them. This decline in Eastern trade and the newfound trade routes dominated by other European states in the Americas and Asia (by way of rounding Africa) would render trade with Venice gradually obsolete. Venice would still maintain what trade it could in the Mediterranean, but it also focused on production and placed increasing importance on its Italian mainland possessions rather than just its declining position overseas in Greek territories, including the loss of Cyprus to the Ottomans in 1571. Though the Venetian navy with other Christian powers won the notable naval victory against the Ottomans in 1570 at Lepanto.

It was also involved in the Italian Wars between various rival city states and the power struggle between the Papacy, France and the Hapsburg realms of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain.

Other factors that impacted the declining trade in the 17th century included an inability to keep up in the textile trade elsewhere in Europe, closure of the spice trade to all but the Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese, French and English and the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) which impacted Venice's trade partners.

Ongoing wars including a 21-year siege of Crete by the Ottomans saw further losses. Although Venice partook in the Holy League headed by the Holy Roman Empire (under Hapsburg Austria) which saw some minor temporary gains from the Ottomans in southern Greece before losing them again in the early 18th century.

War and loss of overseas territories along with a stagnant economy was slightly offset by a somewhat strong position in northern Italy. Nevertheless, its maritime fleet was reduced to a mere shadow of its former glory and it found itself sandwiched still between Austria and France. Over the rest of the 18th century, economic stagnation and social stratification remained prevalent while Venice remained in a quiet peace. However, the French Revolution reignited war in Italy and while Venice remained neutral, it would soon get caught up in events.

The Austrians and the Piedmontese (Italian) allies were beaten by the French Republic's Army of Italy headed by an up-and-coming general named Napoleon Bonaparte. Bonaparte and the French army crossed the borders of northern Italy into Venetian neutral territory to pursue the Austrians. Eventually half of Venice's territory was occupied by France and the remainder of the mainland was occupied by Austria. By secret treaty the French and Austrians were to divide the territory between themselves (Venice was consulted in the matter). Bonaparte gave orders to Venetian doge Ludovico Manin to surrender the city to French occupation to which he abdicated his power. The republic's Major Council met one last time to officially declare an end to republic on May 12th, 1797, after 1,100 years. Venice was placed under a provisional government and ironically the French looted Venice stripping it of artworks to grace the Louvre Museum in Paris along with the Arc d'Triomphe, taking the famed four bronze horses of St. Mark's to adorn the triumphal arch in Paris, the very same horses Venice had confiscated from Constantinople in 1204. It was a symbolic end to the republic, the irony of which did not escape commentators at the time. Following Napoleonic France's final defeat in 1815 the horses were returned to Venice and St. Mark's where they remain today. Venice itself was given over to the Austrian Empire.

The Republic of Venice has a historical legacy in terms of its economic accomplishments through control of trade and its innovative mass production of ships, armaments & trade commodities. It also holds a political legacy worthy of study given it was a unique and enduring polity for 1,100 years. One that maintained a complex and at times chaotic form of government that still managed to function and endure for centuries.

#military history#middle ages#venice#venetian republic#italy#politics#political history#trade#economics#governance#commerce#ottoman empire#spain#byzantine empire#napoleon#doge#republic

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Breastplate

Northern Italy, c. 1560/70

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wenzel Coebergher - Preparations for the martyrdom of St Sebastian - 1599

oil on canvas, height: 288.5 cm (113.5 in); width: 207.5 cm (81.6 in)

Museum of Fine Arts of Nancy, France

Wenceslas Cobergher (1560 – 23 November 1634), sometimes called Wenzel Coebergher, was a Flemish Renaissance architect, engineer, painter, antiquarian, numismatist and economist. Faded somewhat into the background as a painter, he is chiefly remembered today as the man responsible for the draining of the Moëres on the Franco-Belgian border. He is also one of the fathers of the Flemish Baroque style of architecture in the Southern Netherlands.

Born in Antwerp, probably in 1560 (1557, according to one source), he was a natural child of Wenceslas Coeberger and Catharina Raems, which was attested by deed in May 1579. His name is also written as Wenceslaus, Wensel or Wenzel; his surname is sometimes recorded as Coberger, Cobergher, Coebergher, and Koeberger.

Before being known as an engineer, Cobergher began his career as a painter and an architect. In 1573 he started his studies in Antwerp as an apprentice to the painter Marten de Vos. Following the example of his master, Cobergher left for Italy in 1579, trying to fulfil the dream of every artist to study Italian art and culture. On his way there he stayed briefly in Paris, where he learned about his illegitimate birth from seeing the will of his deceased mother. He returned to Antwerp right away to settle some legal matters relating to this discovery. Later in the year, he set forth again to Italy. He settled in Naples in 1580 (as attested by a contract) and remained there till 1597.

In Naples he worked under contract for eight ducats together with the Flemish painter and art dealer Cornelis de Smet. He returned briefly to Antwerp in 1583, buying goods with borrowed money for his second trip to Italy. He is mentioned again in Naples in 1588. In 1591 he allied himself with another compatriot, the painter Jacob Franckaert the Elder (before 1551–1601).

He moved to Rome in 1597 (as attested in a letter to Peter Paul Rubens by Jacques Cools). During that time he had also been preparing a numismatic book in the tradition of Hendrik Goltzius. He must also have built up a reputation as an art connoisseur, since in 1598 he was asked to make an inventory and set a value on the paintings of the deceased cardinal Bonelli.

After the death of his first wife Michaela Cerf on 7 July 1599, he married again, four months later and at the age of forty; his second wife was Suzanna Franckaert, 15-year-old daughter of Jacob Franckaert the Elder, who was also active in Rome. He would have nine children with his second wife, while his first marriage had remained childless.

During his stay in Rome Cobergher became much interested in the study of Roman antiquities, antique architecture and statuary. He was also much interested in the way in which Romans represented their gods in paintings, bronze and marble statues, bas-reliefs and on antique coins. He gathered an important collection of coins and medals from the Roman emperors. These drawings and descriptions were gathered in a set of manuscripts, two of which survive (Brussels, Royal Library of Belgium). He was also preparing an anthology of the Roman Antiquity (according to the French humanist Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc) that was never published. Sometimes the "Tractatus de pictura antiqua" (published in Mantua, 1591) has been ascribed to Cobergher, but this was based on an erroneous reading of an 18th-century catalogue.

At the same time he was witness to the completion of the dome of St. Peter's Basilica in 1590. The architecture of several Roman churches made also a deep impression on him; among them most influential were the first truly baroque façade of the Church of the Gesù, Santa Maria in Transpontina and Santa Maria in Vallicella. He would use their design in his later constructions.

During his stay in Italy he painted, under the name "maestro Vincenzo", a number of altarpieces and other works for important churches in Naples and Rome. His style is somewhat mixed, incorporating Classical and Mannerist elements. His composition is rational and his rendering of the human anatomy is correct. A few of his altarpieces still survive: a Resurrection (San Domenico Maggiore, Naples), a Crucifixion (Santa Maria di Piedigrotta, Naples), a Birth of Christ (S Sebastiana) and a Holy Spirit (Santa Maria in Vallicella, Rome). One of his best known paintings is the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, originally in the Cathedral of Our Lady (Antwerp), but now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nancy. This painting was commissioned by the De Jonge Handboog (archers guild) of Antwerp in 1598, while Cobergher was still in Rome. His Angels Supporting the Dead Lord, originally in the Sint-Antoniuskerk in Antwerp, can now also be found in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nancy, while his Ecce Homo is now in the museum of Toulouse.

Cobergher died in Brussels on 23 November 1634, leaving his family in deep financial trouble. His properties in Les Moëres had to be sold, as well as his house in Brussels. Even his extensive art and coin collection was auctioned off for 10,000 guilders.

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Taddeo Zuccari (Italian, 1529–1566)

Pietà with torchbearers, c.1560-66

Born in Urbino, the painter is considered the main representative of Italian Mannerism. He was Federico”Ts older brother, went to Rome aged 14 and soon became a very popular artist with wealthy clients and was able to establish his own business as a fresco painter. He received commissions from Pope Julius III and Paul VI together with Prospero Fontana, was active in the Villa Giulia and was allowed to paint the representative rooms in the Palazzo Farnese in Caprarola, which can probably be considered his principal work. He also decorated the Sala dei Fasti in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. Zuccari attained a fortune which allowed him to build a palace in Rome. Due to his importance, he was buried near Raphael’s tomb in the Pantheon in Rome.

There are several other versions of the present work, for example in the Galleria Borghese, Rome (canvas, 232 x 142 cm.) or in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino (281 x 154 cm., image no. FAB60351). Upon closer examination, certain aspects suggest that the work was not fully completed before Zuccari’s death in 1666. When giving the painting a title, the wax candles were misunderstood on various occasions as “Attributes of the Passion of Christ”. The Farnese cardinal is said to have conveyed this idea for the depiction with candles to the painter. The famous biographer Giorgio Vasari already mentioned the Zuccari. The importance of the painting is also demonstrated by its distribution as a copperplate engraving.

The painting is considered a protected Italian cultural asset and is located in Italy.

#art#art history#european history#european art#italian art#classical art#peita#Pietà#pieta with torchbearers#Jesus Christ#The Son of God#Jesus#Christ#christianity#christentum#christendom#fine art#fine arts#oil painting#italian#italy#mediterranean#europe#italian peninsula#catholic art#catholic#roman catholic#roman catholic art#traditional art#Taddeo Zuccari

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Engraved close helmet, Milan, Italy, circa 1560-1570

from The Worchester Art Museum

84 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An elegant black anf gilt Breastplate, North Italy, possibly Brescia, ca. 1550-1560, from Peter Finer.

354 notes

·

View notes