#dress history

Text

#yes i know these are for two very different purposes (leisurewear vs. costume party (?????)) but please humor me here 😅#i simply had to have the guy on the right in a poll and i couldn’t find anything more analogous to pair him with 😭😭#so i just had to make do with this#historical fashion polls#fashion poll#historical dress#historical fashion#dress history#fashion history#fashion plate#19th century#19th century fashion#19th century dress#early 19th century#mid 19th century#1830s fashion#1830s dress#1830s#1833#1834

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dress

c. 1930

Velvet trimmed with silk and lace

Label ‘Norman Hartnell 10, Bruton Street. W.’

Acquired from Helena Bonham Carter

The John Bright Collection

#this dress omg so stunning#sorry for all the posts today lmao#1930s fashion#1930s#1930s dress#historical fashion#fashion history#history of fashion#dress history#frostedmagnolias

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Corset discourse really likes to talk in sensationalizing absolutes but historically speaking a corset is just a kind of garment. They could be uncomfortable and painful or they could be well fitted and supportive. They could be hyper-fashionable or they could be brutally practical. You could tightlace them or you could wear them with no reduction whatsoever. Most corsets were probably somewhere in the middle. Like bras. Or shoes. To say they were never perceived as restrictive or used as tools of enforcing dangerous/misogynistic beauty standards is like saying women's shoes never restrict freedom of movement. Patently untrue, but that doesn't mean those shoes have some deeper moral good or evil and it certainly doesn't mean we can use that fact to draw sweeping generalizations about the relationships of entire centuries of women to their own bodies. Corsets, like all clothing, exist in context.

12K notes

·

View notes

Note

So I've seen conflicting stories about the colour black in history.

Some say it's very expensive and hard to maintain, so that's why rich merchants wore black. Evidence in portraits.

Some say that for dyes it's on the cheaper side actually.

Some say the expensive black doesn't come from dye but rather the colour of the animal, so black fabric comes from black fibre which comes from black sheep. How exactly would black sheep be more expensive than regular white sheep?

Which one is right? I know this is probably influenced by which century it's set in, like maybe some eras have an easier time getting black dye

I found a well-sourced blog post about this, luckily, because I'm a 19th-century focused researcher and I've heard conflicting things about black in earlier periods. It seems to be that high-quality black-dyed fabric was difficult to obtain in the west from the Middle Ages potentially through the 18th century because it required massive amounts of dye to get the color very deep ("true black"). Lesser black shades were quite common, though, so black, period, doesn't seem to be more expensive than any other color. Possibly the intensively dyed, deep blacks might have been? But not black in general.

source

Rich merchants did wear black- but so did other people. They just usually didn't have portraits.

The black sheep thing I've never heard before. And anyway, that could only apply to wool- not cotton, linen, silk, leather, etc.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

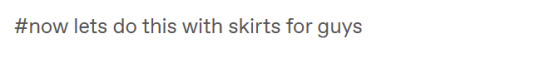

So I got this tag on my answer to an ask about when it became acceptable for western women to wear pants, and you know it's all I need to go on a tangent.

I think the short answer here would be men have worn skirts as long as people have worn anything, so pretty long tbh. But since I am incapable of answering anything shortly, I think we can re-frame this question:

When did skirts stop being socially acceptable for men?

So let's start with acknowledging that tunics, togas, kirtles and such men wore through history were, in fact, skirts. I think there's often a tendency to think of these as very different garments from those that women wore, but really they are not. Most of the time they were literally referred to with the same name. (I will do a very broad and simplified overview of men's clothing from ancient times to Early Middle Ages so we can get to the point which is Late Middle Ages.)

Ancient Greek men and women both wore chitons. Even it's length wasn't determined by gender, but by occupation. Athletes, soldiers and slaves wore knee-length chitons for easier movement. Roman men and women wore very similar garment, tunics. Especially in earlier ancient Rome long sleeves were associated with women, but later became more popular and unconventional for men too. Length though was still dependent on occupation and class, not gender. Toga was sure men's clothing, but worn over tunic. It was wrapped around the waist, like a dress would, and then hung over shoulder. Romans did wear leggings when they needed to. For example for leg protection when hunting as in this mosaic from 4th century. They would have been mostly used by men since men would be doing the kinds of activities that would require them. But that does not lessen the dressyness of the tunics worn here. If a woman today wears leggings under her skirt, the skirt doesn't suddenly become not a skirt.

All over Europe thorough the early Middle Ages, the clothes were very similar in their basic shape and construction as in Rome and Greece. In Central and Northern Europe though people would wear pants under shorter tunics. There were exceptions to the everyone wearing a tunic trend. Celtic men wore braccae, which were pants, and short tunics and literally just shirts. Celts are the rare case, where I think we can say that men didn't wear dresses. Most other peoples in these colder areas wore at least knee-length tunics. Shorter tunics and trousers were worn again mostly by soldiers and slaves, so rarely any other woman than slave women. The trousers were though definitely trousers in Early Middle Ages. They were usually loose for easier construction and therefore not that similar to Roman leggings. However leggings style fitted pants were still used, especially by nobility. I'd say the loose trousers are a gray area. They wore both dresses and pants, but still definitely dresses. I'd say this style was very comparable to the 2000s miniskirts over jeans style. First one below is a reconstruction of Old Norse clothing by Danish history museum. The second is some celebrity from 2005. I see no difference.

When we get to the high Middle Ages tunics are still used by both men and women, and still it's length is dependent on class and activity more than gender, but there's some new developments too. Pants and skirt combo is fully out and leggings' are back in in form of hose. Hose were not in fact pants and calling them leggings is also misleading. Really they are socks. Or at least that's how they started. As it has become a trend here they were used by everyone, not just men. During early Middle Ages they were worn often with the trousers, sometimes the trousers tucked inside them making them baggy. In high Middle Ages they became very long when used with shorter tunics, fully displacing the need for trousers. They would be tied to the waist to keep them up, as they were not knitted (knitting was being invented in Egypt around this time, and some knitting was introduced to Europe during middle Ages, but it really only took off much later during Renaissance Era) and therefore not stretchy. First picture is an example of that from 1440s. Another exciting development in the High Medieval era was bliaut in France and it's sphere of influence. Bliaut was an early attempt in Europe of a fitted dress. And again used by both men and women. The second illustration below from mid 12th century shows a noble man wearing a bliaut and nicely showing off his leg covered in fitted hose. Bliaut was usually likely fitted with lacing on the sides, but it wasn't tailored (tailoring wasn't really a thing just yet) and so created a wrinkled effect around the torso.

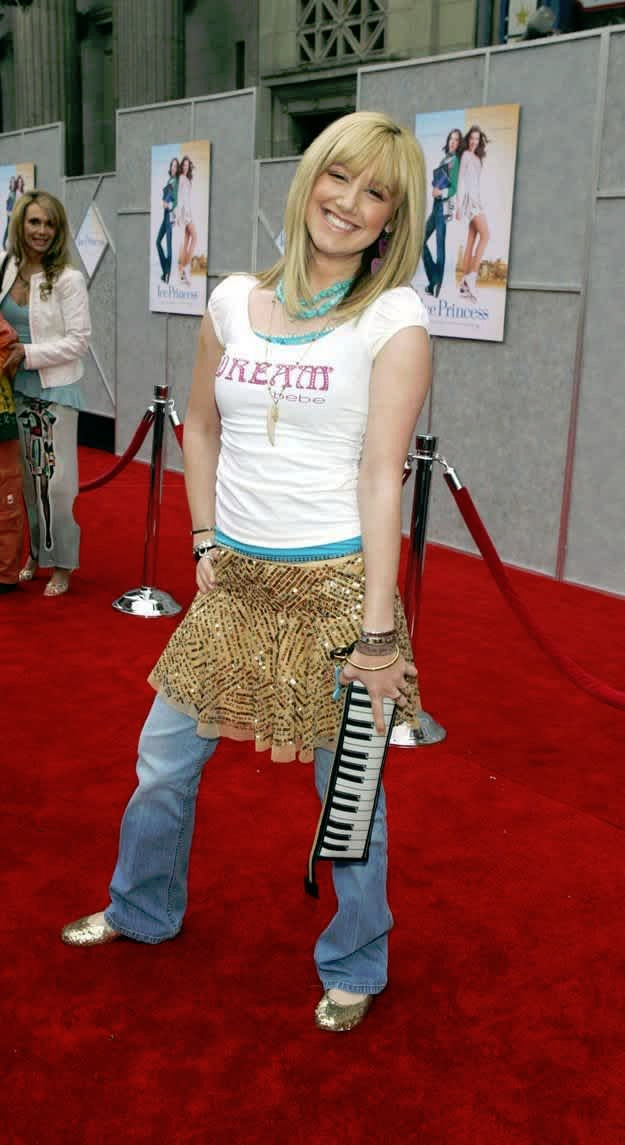

In the 14th century things really picked up in European fashion. European kingdoms finally started to become richer and the rich started to have some extra money to put into clothing, so new trends started to pop up rapidly. Tailoring became a thing and clothes could be now cut to be very fitted, which gave birth to fitted kirtle. At the same time having extra money meant being able to spend extra money on more fabric and to create very voluminous clothing, which gave birth to the houppelande.

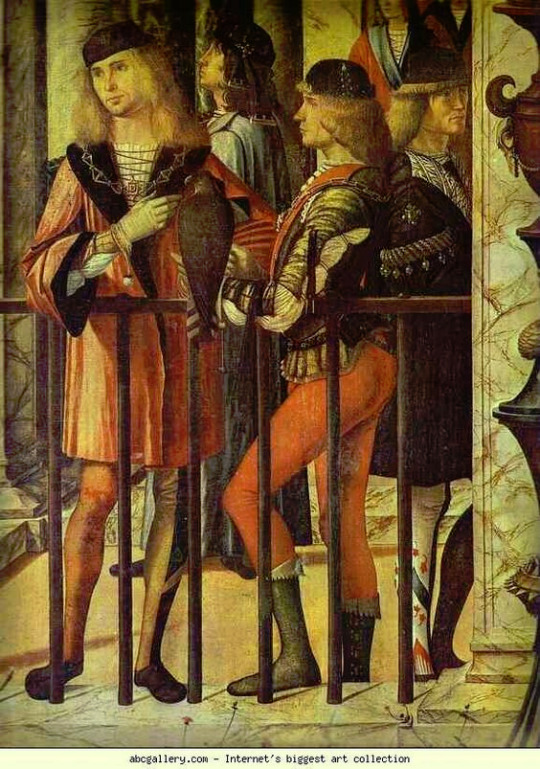

Kirtle was once again worn by everyone. It wasn't an undergarment, for women that would be shift and men shirt and breeches, but it was an underlayer. It could be worn in public but often had at least another layer on top of it. The bodice part, including sleeves were very fitted with lacing or buttons (though there were over-layer kirtles that had different sleeves that changed with fashions and would be usually worn over a fitted kirtle). Men's kirtles were short, earlier in 14th century knee-length but towards the end of the century even shorter styles became fashionable in some areas. First picture below shows a man with knee-length kirtle from 1450s Italy.

Houppelande was also unisex. It was a loose full-length overgown with a lot of fabric that was gathered on the neckline and could be worn belted or unbelted. The sleeves were also wide and became increasingly wider (for men and women) later in the century and into the next century. Shorter gowns similar in style and construction to the houppelande were also fashionable for men. Both of these styles are seen in the second picture below from late 14th century.

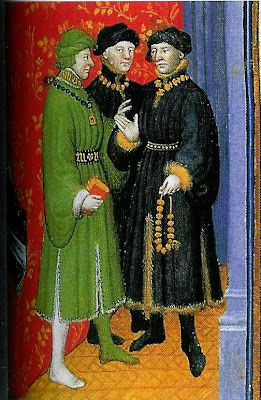

In the very end of 14th century, first signs of pantification of men can be seen. In France and it's sphere of influence the skirt part of the kirtle became so short it barely covered the breeches as seen below on these fashionable musicians from 1395-1400 France. Long houppelandes, length ranging from floor to calf, were still used by men though (the second picture, 1414 France), as were knee and thigh length gowns of similar loose style.

The hems continued to be short through the 15th century in France, but in other places like Italy and German sphere of influence, they were still fairly long, at least to mid thigh, through the first half of the century. In France at some point in late 13th century the very short under-kirtle started to be called doublet and they are just getting shorter in 1400s. The showing underwear problem was fixed by joined hose and the codpiece, signaling the entrance of The Sluttiest Era of men's fashion. Below is an example from 1450s Belgium of doublet and early codpiece in display. As you can see from the other figures, the overgowns of the previous century were also getting very, very short. In the next French example below from 1470s we can see the skirt shrink out of existence right before our eyes.

The very skimpy doublet and it's accompanying codpiece spread to the rest of the Europe in the second half of 15th century and it would only get sluttier from there. The Italians were just showing their full ass (example from 1490s). The dress was not gone yet though. The doublet and codpiece continued to be fashionable, but the overdress got longer again in the French area too. For example in the second example there's Italian soldiers in a knee length dresses from 1513.

But we have to talk about the Germans. They went absolutely mad with the whole doublet and codpiece. Just look at this 1513 painting below (first one). But they did not only do it sluttier than everyone else, they also changed the course of men's fashion.

Let's take a detour talking about the Landsknecht, the mercenary pikeman army of the Holy Roman Empire. (I'm not that knowledgeable in war history so take my war history explanation with a grain of salt.) Pikemen had recently become a formidable counter-unit against cavalry, which earlier in the Medieval Era had been the most important units. Knights were the professional highly trained cavalry, which the whole feudal system leaned against. On the other hand land units were usually not made of professional soldiers. Landsknecht were formed in late 15th century as a professional army of pikemen. They were skilled and highly organized, and quickly became a decisive force in European wars. Their military significance gave them a lot of power in the Holy Roman Empire, some were even given knighthood, which previously wasn't possible for land units, and interestingly for us they were exempt from sumptuary laws. Sumptuary laws controlled who could wear what. As the bourgeois became richer in Europe in late Middle Ages and Renaissance Era, laws were enacted to limit certain fabrics, colors and styles from those outside nobility, to uphold the hierarchy between rich bourgeois and the nobles. The Landsknecht, who were well payed mercenaries (they would mutiny, if they didn't get payed enough), went immediately absolute mad with the power to bypass sumptuary laws. Crimes against fashion (affectionate) were committed. What do you do, when you have extra money and one of your privileges is to wear every color and fabric? You wear every color and fabric. At the same time. You wear them on top of each other and so they can be seen at the same time, you slash the outer layer. In the second image you can feast your eyes on the Landsknecht.

Just to give you a little more of that good stuff, here's a selection of some of my favorite Landsknecht illustrations. This is the peak male performance. Look at those codpieces. Look at those bare legs. The tiny shorts. And savor them.

The Landsknecht were the hot shit. Their lavish and over the top influence quickly took over men's fashion in Germany in early 1500s. Slashing, the technique possibly started by them, but at least popularized by them, instantly spread all over Europe. That's how you get the typical Renaissance poof sleeves. They at first slashed the thighs of their hose, but it seems like to fit more of everything into their outfits, they started wearing the hose in two parts, upper hose and nether hose, which was a sort of return to the early Medieval trousers and knee-high hose style. The two part hose was adopted by the wider German men's fashion early in the century, but already in 1520s had spread to rest of Europe. It was first combined with the knee-length overdress that had made it's comeback in the turn of the century, like in this Italian painting from 1526 (first image). At this point knitting had become established and wide-spread craft in Europe and the stockings were born, replacing nether hose. They were basically nether hose, but from knitted fabric. The gown shortened again and turned into more of a jacket as the trunk hose became increasingly the centerpiece of the outfit, until in 1560s doublet - trunk hose combination emerged as the standard outerwear (as seen in the second example, 1569 Netherlands) putting the last nail on the coffin of the men's dress as well as the Sluttiest Era. The hose and doublet became profoundly un-slutty and un-horny, especially when the solemn Spanish influence spread all over with it's dark and muted colors.

Especially in Middle Ages, but thorough European history, trousers have been associated with soldiers. The largely accepted theory is that trousers were invented for horse riding, but in climates with cold winters, where short skirts are too cold, and long skirts are still a hazard when moving around, trousers (with or without a short skirt) are convenient for all kinds of other movement requiring activities like war. So by adopting hose as general men's clothing, men in 1500s associated masculinity with militarism. It was not a coincidence that the style came from Landsknecht. I may have been joking about them being "peak male performance", but really they were the new masculine ideals for the new age. At the time capitalism was taking form and European great powers had begun the process of violently conquering the world for money, so it's not surprising that the men, who fought for money and became rich and powerful doing so, were idealised.

Because of capitalism and increasingly centralized power, the feudal system was crumbling and with it the feudal social hierarchy. Capitalism shifted the wealth from land ownership (which feudal nobility was built upon) to capital and trade, deteriorating the hierarchy based on land. At the same time Reformation and centralized secular powers were weakening the power of the Church, wavering also the hierarchy justified by godly ordain. The ruling class was not about to give up their power, so a new social hierarchy needed to form. Through colonialism the concept of race was created and the new hierarchy was drawn from racial, gender and wealth lines. It was a long process, but it started in 1500s, and the increasing distinction between men's and women's fashions was part of drawing those lines. At the same time distinctions between white men and racialized men, as well as white women and racialized women were drawn. As in Europe up until this point, all over the world (with some exceptions) skirts were used by everyone. So when European men fully adopted the trousers, and trousers, as well as their association to military, were equated with masculinity, part of it was to emasculate racialized men, to draw distinctions.

Surprise, it was colonialism all along! Honestly if there's a societal or cultural change after Middle Ages, a good guess for the reason behind it is always colonialism. It won't be right every time, but quite a lot of times. Trousers as a concept is of course not related to colonialism, but the idea that trousers equal masculinity and especially the idea that skirts equal femininity are. So I guess decolonize masculinity by wearing skirts?

#this has been sitting in my drafts almost finished for like a year or something#historical fashion#fashion history#fashion#history#dress history#men's historical fashion#renaissance fashion#medieval fashion#western fashion#western fashion history#landsknecht

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Men's double-breasted waistcoat, c. 1835-1845. Silk, lined in cotton, backed with silk twill, with detail of rose design:

The John Bright Collection notes that "The back is adjusted with a tape threaded through three pairs of metal eyelets on tabs. These metal eyelets, patented in the mid 1820s, were a great improvement on the stitched eyelets that preceded them, being able to take greater strain."

#Eighteen-Thirties Thursday#1830s#1840s#waistcoat#romantic era#fashion history#historical men's fashion#men's fashion#fashion#dress history#extant#early victorian era

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Interested in fat fashion history? Have I got the Instagram account for you! @/stoutstylehistory posts photos, paintings, and extant garments from 1500-1800, all properly sourced and credited. Enjoy!

[do not repost these images]

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Wool wedding dress, c.1895

cr: finnwicks_costume

#fashion history#historical fashion#dress history#history of dress#history of fashion#wedding dress#antique fashion#1890s#1890s fashion#1895#victorian#victoriana#victorian era#victorian fashion#19th century fashion#edwardiana#edwardian#edwardian era#edwardian fashion#e

400 notes

·

View notes

Text

Revue de la Mode, 1872

#Revue de la Mode#1872#1870s#Victorian#Victoriana#Victorian fashion#Victorian dress#Victorian style#Victorian era#Victorian art#Victorian girl#Victorian woman#Fashion#Fashionplate#Fashion sketch#Fashion illustration#Fashion history#Historical fashion#Historical clothing#Dress history#Vintage dress#Vintage fashion#Antique dress#Antique fashion#Antique clothing#19th century#19th century style#19th century dress#19th century fashion#19th century art Corset

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

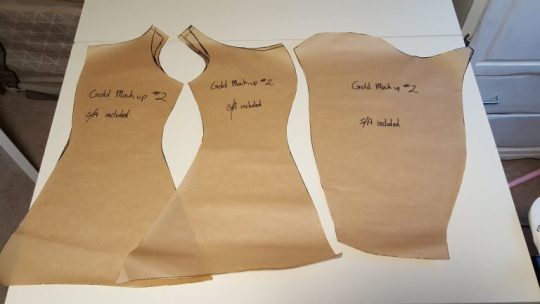

I mean, dresses can be very practical if they're made well but still, I somewhat agree. There's only so much you can do in below-knee dresses with puffy skirts. Women's sportswear in the 19th century did exist, but mostly in the later part of the century (I'm kind of unsure tho), when skirts started getting narrower again.

Also, it's not historically accurate. Tangled takes place just before Frozen, which takes place in ~1843. I assume then that Vat7K takes place in ~1845, and dresses back then did NOT look like Nuru's dress, even after excusing the heavy creative liberties that Tangled the Series usually takes. Nuru's outfit looks like someone took a dress from the 1820s, cropped it, and added sheer fabric and a few 18th century details. The high waistline here would have started dropping lower during the 1830s, and by the '40s it'd be practically at the natural waist.

Additionally, Nuru's dress looks very different from the Kotoans' dresses depicted in TTS S3 Ep7: Beginnings (Koto is commonly considered to be the Air Kingdom in Vat7K). This episode would have taken place very close in timing to Tangled, so around 1840. The Kotoans' dresses look pretty good in terms of historical accuracy and also in terms of differentiating them from other kingdoms. However, they would not have changed that dramatically to the style that Nuru's dress is, in the span of just 4-5 years after which Vat7K takes place.

edit: I often give her an alternate outfit when I draw her. However this is usually still a dress, although less sparkly, because I don't think the Trials are all that physically taxing. I've seen that a lot of ppl hc Nuru as lesbian, so imo it would be cool to see her in menswear too, just to try out that aesthetic.

Lastly, please note that I am in no way an expert and literally just a kid with a special interest on fashion history, so take my words with several grains of salt. I may sound 100% confident here, but the things I say might still be wrong. I would also like to acknowledge that historical accuracy was never the point of Disney shows, but it's fun to analyse them like it was. Thanks for reading through my silly rant/infodump 🌿🐛

(making this a non-reblog post because I want attention; OG post by @foursthemagicknumber)

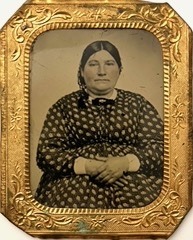

Image references below so you know what I'm talking about (please read image descriptions).

#silvern0w0#silbern#varian and the seven kingdoms#varian and the 7 kingdoms#nuru vat7k#vat7k#vat7k nuru#disney#tangled the series#tts#rta#fashion history#historical fashion#fashion#costume#19th century#tangled#disney tangled#rapunzel's tangled adventure#dress history#design analysis#costume design#history#clothing#historical clothing#dresses#gown#skirts

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

The garment’s silk was in good condition, and it still had the original buttons, Rivers Cofield wrote on her blog. The buttons appeared to have images of Ophelia from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

#shakespeare#william shakespeare#dress#dress history#code#hamlet#ophelia#costume#vintage#smithsonian#silk dress

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

submitted by @fuzzyhedgepig 🖤🖤

#historical fashion poll submission#these are gorgeousssssssss#historical fashion polls#fashion poll#historical dress#historical fashion#dress history#fashion history#fashion plate#19th century#19th century fashion#19th century dress#early 19th century#mid 19th century#1830s fashion#1830s dress#1830s#1837#mourning#mourning wear

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Afternoon Dress

c. 1911-1912

Silk chiffon over silk, grosgrain, lace, boned, embroidered

Made by Mascotte

Victoria and Albert Museum

#edwardian gown#Edwardian#Edwardian fashion#Edwardian era#Edwardian dress#1910s#fashion history#historical fashion#history of fashion#dress history#20th century fashion#frostedmagnolias

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Call this corset not safe for tumblr the way it got. Boning and gore

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t know who needs to hear this today, but:

- arsenic dye was used to make multiple shades of green in the 18th/19th centuries

- green dyes without arsenic were also still in common use

- consumer outcry against arsenic dye started as early as the 1860s, with many manufacturers beginning to phase it out around that time due to customer demand

- arsenic – dyed clothing is not likely to do more to the wearer than cause a skin rash. The majority of deaths from exposure to the dye were caused by other, more concentrated sources, and/or among workers exposed to large quantities of the pigment on a daily basis rather than consumers

- IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO TELL IF A GREEN ANTIQUE GARMENT IS DYED WITH ARSENIC WITHOUT CHEMICAL TESTING. There is NO telltale quality visible to the naked eye that I am aware of

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

This is kind of random, but would it have been a struggle for a big busted women to wear fashionable silhouettes in the medieval era? I’ve heard some costume historians discuss that there were forms of bust support, but most of what I’ve seen pre-1500s seems like it would have been a nightmare for any ancestor with a similar bodytype to wear. Am I just from a line of women doomed to horrible back pain? (On the flip side of the situation, I’ve found corsets and stays to be rather comfortable, so that’s not a problem)

As a fellow big boob haver, I have good news for you! There were pretty good Medieval bust supporting garments and I have tested one of them.

With sturdy fabric, tailoring and lacing you can create pretty good bust support. Lacing was popularized first in 12th century in form of bliaut, and in 14th century tailoring became standard for everyday garments. I don't know how well bliaut supported the bust, but since it doesn't fit super snugly, I assume it doesn't distribute the weight of the boobs as well as tailored supporting garments and therefore isn't as supportive. I'm also not actually sure if there was proper bust supporting garments before that, I haven't looked into it. I know Romans bound their breasts with cloth wrapped around the chest, so maybe that technique continued (at least for those who especially needed it) till lacing and tailoring became a thing. For more about how supporting garments developed in Europe through history, I have a post about development of lacing, which coincides pretty well with that history from 12th century forward.

Personally I have experience with Medieval Bathhouse dress, which was used in the Germanic Central-European area roughly in 14th to 16th century. It's called the Bathhouse dress because most depictions of it are from bathhouse settings, but there's depiction also in bed chambers and other contexts, so I think it's pretty safe to assume it was used more generally as an undergarment. It often had separate cups for the boobs (see the only extant garment left of it, the so called "Lengberg Castle Bra"), but not always. Unlike most other undergarments at the time, it was sort of a shift (the lowest layer) and a supporting garment combined into one.

I sewed my own recreation of it (with some alterations because I made it for my everyday use, not as a historical recreation) and did a post about my results, where I go deeper into the history of the garment too. I didn't construct it very well and I did an error in the design of the back, which cause the strain of the shoulder straps to focus too much on very specific spots in the back panel, which eventually made the fabric there break too many times. (There were some other smaller design flaws too, like the waistline is lower than my natural waist so it rose and wrinkled annoyingly.) I did use it daily (except when I washed it) for a fairly long time though and it was super comfortable and helped a lot with back pain (and shoulder pain caused by use of modern bras). I hate that I've had to go back to modern bras because I haven't had the time to remake it yet. (I'll probably make a follow up post once I get around to it, where I go through the issues of the first version and how I addressed them in the next attempt.) Well fitted and shaped bodice which is then laced does surprisingly much even without any additional reinforcements.

I haven't made a Medieval kirtle (though I will some day), but it was the more widely used Medieval supporting garment, which eventually replaced Bathhouse dress in the area where that was used. Kirtle is worn over a shift, but it broadly works similarly. Kirtles could be front, side or back laced depending on the time period and how the Kirtle was constructed. Multiple layers of kirtles could be used and looser overgarments (like houppelande) were often used on top of it. Kirtle was used by everyone, including men, but for those who didn't need bust support, it's purpose was mainly to create the fashionable silhouette. Here's three depictions of kirtles from 15th century. First unlaced, but has lacing on the front, second close up of the side lacing and third shows nicely how both front and side/backlacing shaped the bust.

Morgan Donner is a costumer, who focuses a lot on Medieval costuming and has a big bust, so while I haven't personally tested the supportiveness of kirtle, she certainly has. The kirtle bodice part needs to be patterned to accommodate the breasts by giving it round shapes and the kirtle needs to be a little too small so there's room to lace it to fit well. Lining also helps to reinforce the fabric and make it more firm and supportive. Here's Morgan's pattern from the tutorial in her website and how the kirtle eventually fits for her. (Also look at the handsome boy in his handsome matching outfit.)

She also has a video relating to the same kirtle project, where she explains her method to pattern a kirtle specifically so it's supportive for big bust.

In 16th century more stiffness was added to kirtles, first with very stiff lining and then with boning, but that doesn't necessarily add to the bust support, rather it just allows the kirtle to shape the bust and the body in general more and better support a heavy skirt. Firm fabric secured snugly with lacing is already very good at distributing the weight of the boobs to the whole torso.

In conclusion, at least since 14th century people with our body type were not doomed to eternal back pain and even before that some ways to help with it were probably used.

#historical fashion#fashion history#dress history#history#historical costuming#historical sewing#sewing#crafts#costuming#fashion#medieval fashion

232 notes

·

View notes