#16th C CE

Text

“A 16th c. Scottish Plaid was Found in a Bog–Now Becomes Oldest Historical Tartan Available to Wear Today”

A textile manufacturer in Scotland has recreated the oldest-known piece of Scottish tartan ever found, which was buried for centuries.

Discovered approximately forty years ago in a peat bog, the Glen Affric Tartan underwent testing organized by The Scottish Tartans Authority last year to confirm it was the oldest surviving piece of tartan, dating back to between 1500-1600 CE.

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval Hermitage atop Katskhi Pillar, in Georgia (South Caucasus), c. 800-900 CE: this church was built during the Middle Ages; it sits atop a limestone column that has been venerated as a "Pillar of Life" for thousands of years

Known as Katskhi Pillar (or Katskhis Sveti), this enormous block of limestone is located in western Georgia, about 10km from the town of Chiatura.

The church that stands atop Katskhi Pillar was originally constructed during the 9th-10th century CE. It was long used as a hermitage for Stylites, who are sometimes referred to as "Pillar Saints" -- Christian ascetics who lived, prayed, and fasted atop pillars, often in total isolation, in an effort to bring themselves closer to God. This tradition originated in Syria during the 5th century CE, when a hermit known as Simeon the Elder purportedly climbed up onto a pillar and then stayed there for nearly 40 years, giving rise (no pun intended) to the Stylites. Stylitism managed to survive for about 1,000 years after its inception, but it gradually began to die out during the late Middle Ages, and by the end of the 16th century, it had essentially gone extinct.

Researchers don't really know how the monks originally gained access to the top of Katskhi Pillar, or how they were able to transport their building materials up to the top of the column. There's evidence that the Stylites were still living at Katskhi Pillar up until the 15th century, but the site was then abandoned shortly thereafter. This was the same period in which Georgia came under Ottoman rule, though it's unclear whether or not that may have played a role in the abandonment of the site.

The hermitage continued to lay abandoned for nearly 500 years after that. No one had been able to gain access to the top of the pillar, and very little was even known about the ruins that lay scattered at the top, as knowledge about the site's origin/history was gradually lost. There are many local legends that emerged as a way to fill in those blanks.

The site was not visited again until July 29th, 1944, when a mountaineer finally ascended to the top of the column with a small team of researchers, and the group performed the first archaeological survey of the ruins. They found that the structure included three hermit cells, a chapel, a wine cellar, and a small crypt; within the crypt lay a single set of human remains, likely belonging to one of the monks who had inhabited the site during the Middle Ages.

A metal ladder (the "stairway to Heaven") was ultimately installed into the side of the pillar, making it much easier for both researchers and tourists to gain access to these ruins.

The hermitage at the top of Katskhi Pillar actually became active again in the early 1990's, when a small group of monks attempted to revive the Stylite tradition. A Georgian Orthodox monk named Maxime Qavtaradze then lived alone at the top of Katskhi Pillar for almost 20 years, beginning in 1995 and ending with his death in 2014. He is now buried at the base of the pillar.

While the hermitage is no longer accessible to the public, and it is currently uninhabited, it's still visited by local monks, who regularly climb up to the church in order to pray. There is also an active monastery complex at the base of the pillar, where a temple known as the Church of the Simeon Stylites is located.

The Church of the Simeon Stylites: this church is located within an active monastery complex that has been built at the base of the pillar; several frescoes and religious icons decorate the walls of the church, and a small shrine containing a 6th century cross is located in the center

There are many lingering questions about the history of Katskhi Pillar, particularly during the pre-Christian era. There is at least some evidence suggesting that it was once the site of votive offerings to pagan deities, as a series of pre-Christian idols have been found buried in the areas that surround the pillar; according to local tradition, the pillar itself was once venerated by the pagan societies that inhabited the area, but it's difficult to determine the extent to which these claims may simply be part of the mythos that surrounds Katskhi Pillar, particularly given its mysterious reputation.

Sources & More Info:

BBC: Georgia's Daring, Death-Defying Pilgrimage

CNN: Katskhi Pillar, the Extraordinary Church where Daring Monks Climb Closer to God

Radio Free Europe: Georgian Monk Renews Tradition, Lives Atop Pillar

Architecture and Asceticism (Ch. 4): Stylitism as a Cultural Trend Between Syria and Georgia

Research Publication from the Georgian National Museum: Katskhi Pillar

Journal of Nomads: Katskhi Pillar, the Most Incredible Cliff Church in the World

Georgian Journal: Georgia's Katskhi Pillar Among World's 20 Wonderfully Serene and Secluded Places

#archaeology#history#anthropology#artifact#medieval architecture#medieval church#Stylites#asceticism#georgia#sakartvelo#katskhi pillar#religion#travel#monastery#paganism#caucasus#medieval europe#christianity#strange places

450 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marie de France

Marie de France (wrote c. 1160-1215 CE) was a multilingual poet and translator, the first female poet of France, and a highly influential literary voice of 12th-century CE Europe. She is credited with establishing the literary genre of chivalric literature (though this is contested), contributing to the development of the Arthurian Legend, and developing the Breton lais (a short poem) as an art form. Marie's published works include:

Lais (including the Arthurian works Chevrefueil and Lanval)

Aesop's Fables (a translation from Middle English to French) and other fables

St. Patrick's Purgatory (also known as The Legend of the Purgatory of St. Patrick)

She was trilingual, writing in the Francien (Parisian) dialect with a command of Latin and Middle English. Her lais were developed from the earlier Breton lais poetic form and so she must have also known Celtic Breton and been acquainted with Brittany. Her works influenced later poets, notably Geoffrey Chaucer, and her imagery in St. Patrick's Purgatory would be used by later writers in depictions of the Christian afterlife.

Marie's works were popular in aristocratic circles but frequently featured lower-class characters as more worthy and noble than their supposed social superiors and always cast women as strong central characters. Her vision of female equality has led to her designation as a proto-feminist in the modern day, and her works remain as popular as they were in her lifetime.

Identity

Her actual name is unknown – `Marie de France' is a pen name given her only in the 16th century CE. All that is known of her comes from her work in which she identifies herself as Marie from France. Based on details in her work including knowledge of place names and geography, and the sources she drew from, scholars have determined that Marie spent a significant amount of time in England at the court of Henry II (r. 1154-1189 CE) and his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine (l. c. 1122-1204 CE).

Scholars suggest Marie may have been Henry's half-sister who perhaps followed him from Normandy to England when he was crowned king in 1154 CE. The Lais of Marie de France are dedicated to “a noble king” who is most likely Henry II but precisely how Marie meant this dedication is unclear. Marie's poetry often features women imprisoned or otherwise poorly treated by men and this theme mirrors Henry's relationship with Eleanor.

Throughout their marriage, Henry was unfaithful to his wife numerous times and carried on an open affair with the noblewoman Rosamund Clifford. When Henry's sons rebelled in 1173-1174 CE with Eleanor's support, the king had her imprisoned for the next 16 years. This same sort of relationship, often with similar details, appears in a number of Marie's works. Further, Henry does not seem to have been as fond of poetry and poets as his wife was and so an interpretation of Marie's dedication as sarcastic is probable.

In modern-day scholarship, Marie is almost always credited with establishing the genre of chivalric literature, but this seems unlikely as her works clearly draw on a pre-existing tradition of courtly love literature whose central motifs she inverts. In courtly love poetry, the knight is seen rescuing the damsel in distress; in Marie's works, the knight is often the one who has imprisoned her in the first place or, sometimes, the one in need of rescue.

Continue reading...

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

#MetalMonday :

Ewer in the form of a Hamsa (Gander)

Indian, Deccan or Northern India, ca. 16th c.

Bronze with later brass repairs, copper-arsenic paste

H 15 3/16 in (38.5 cm)

on view at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

“The body of this ewer takes the form of a goose (hamsa), another common motif in ancient Hindu and Buddhist iconography, where it is associated both with the waters of life, because of its aquatic nature, and with wisdom and purity, on account of its legendary ability to separate milk from water. The spout takes the form of a makara—a mythological aquatic creature that resembles a crocodile with an elephant’s trunk and a fish’s tail—another quintessentially South Asian motif and one of the most commonly used propitious emblems in Indian decorative art.

Other features of the ewer resonate more closely with Islamic artistic traditions, which came to South Asia with travelers and traders soon after the emergence of Islam itself in the seventh century CE. Thus, while vessels in the form of animals are quite rare in Indian metalwork before the Sultanate period (1206–1526), when Muslim-ruled kingdoms first controlled large areas of South Asia, zoomorphic ewers have a long history in Islamic metalwork going back to the eighth century CE. The hamsa ewer beautifully represents a confluence of motifs, mythologies, and objects that belong solely to neither Islamic nor Hindu cultural traditions. Indeed, it would have served equally well the needs of either a Muslim or a Hindu owner, facilitating the performance of ritual ablutions before religious observances within the home; or it may have been proffered by a servant at an elite banquet, enabling Muslim and Hindu guests alike to cleanse their hands before and after the meal.”

https://collections.mfa.org/objects/18461/ewer-in-the-form-of-a-hamsa-gander

#animals in art#museum visit#birds in art#bird#hamsa#gander#metalwork#bronze#ewer#Indian art#South Asian art#Asian art#Museum of Fine Arts Boston#16th century art

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

whale made of steatite, cinnabar, and shell; Chumash (indigenous people of southern California); c. 16th-17th century CE

currently in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (accession no. 1979.206.396)

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

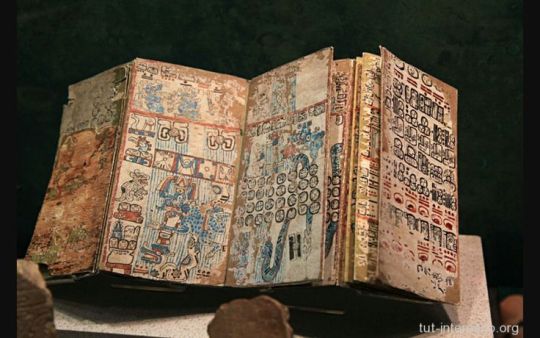

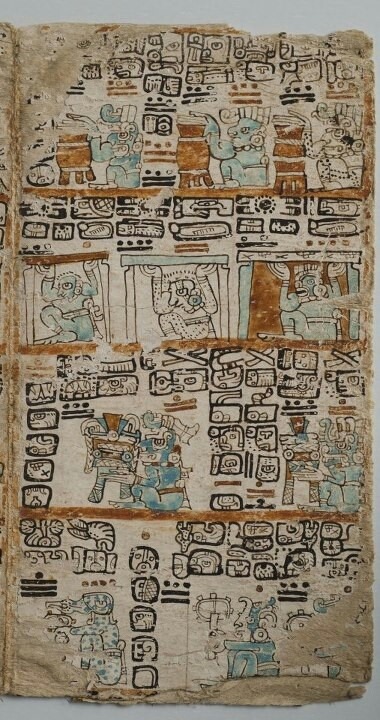

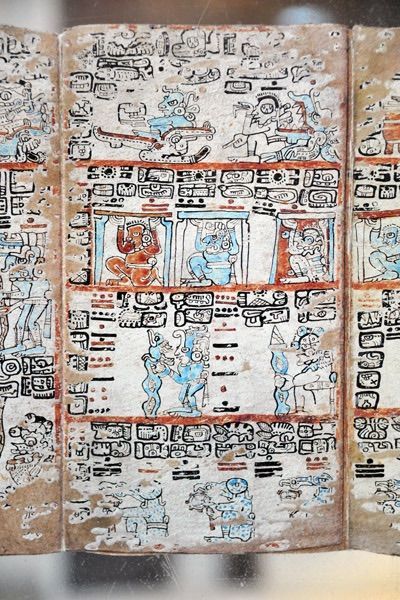

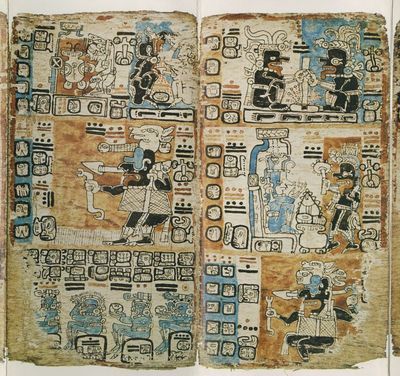

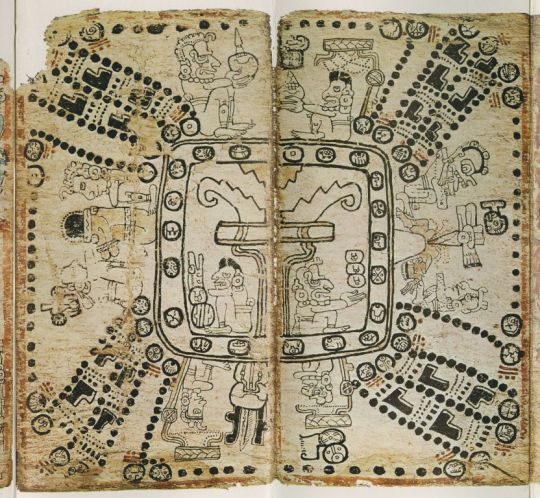

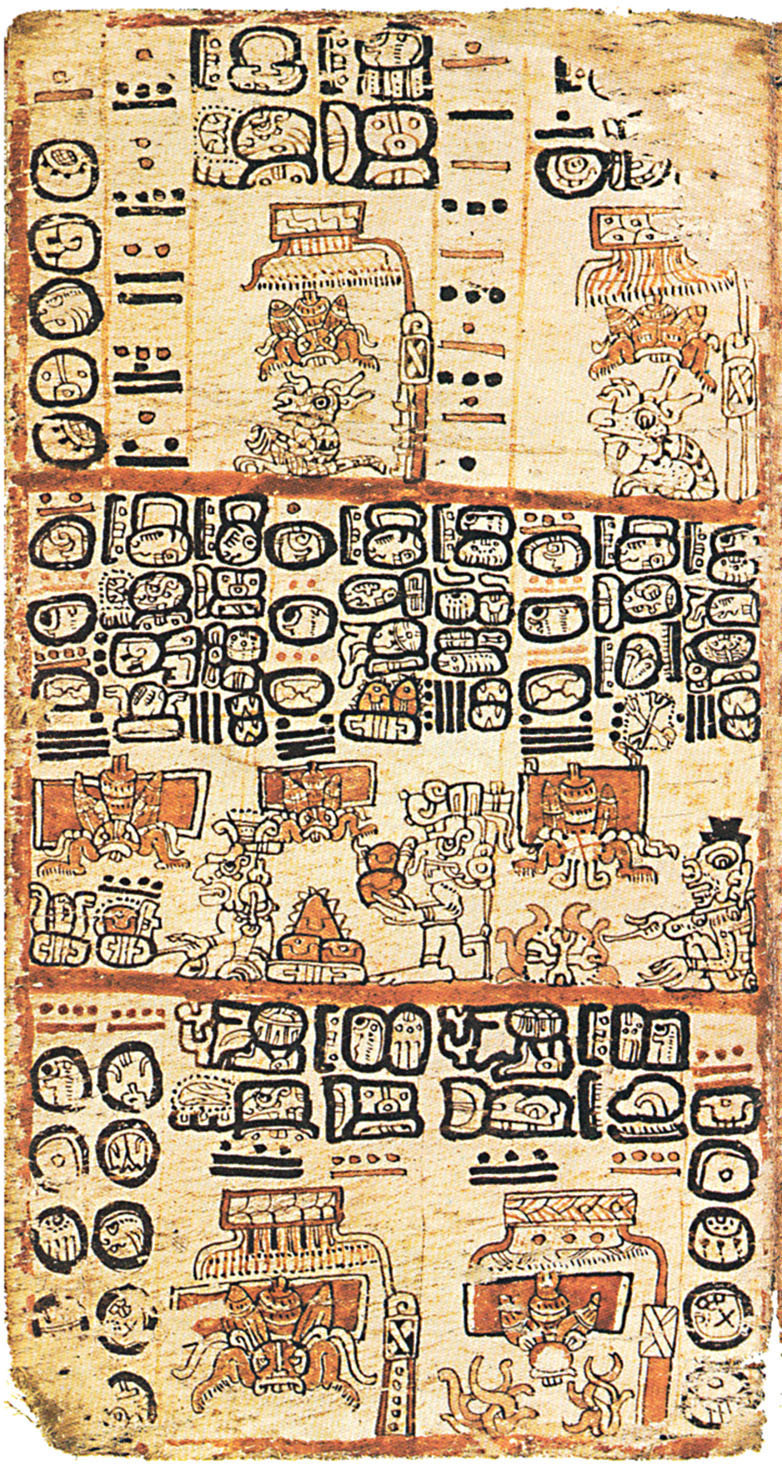

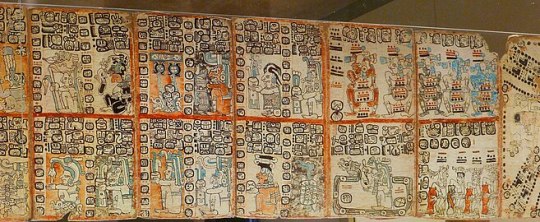

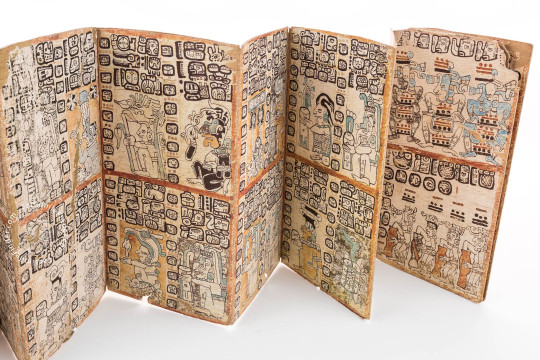

☀Madrid Codex (Maya)

according to sources this code content mainly consists of almanacs and horoscopes used to help Maya priests in the performance of their ceremonies and divinatory rituals . The codex also contains astronomical tables , although fewer than those in the other three surviving Maya codices .

- Madrid Codex, together with the Paris, Dresden, and Grolier codices, a richly illustrated glyphic text of the pre-Conquest Mayan period and one of few known survivors of the mass book-burnings by the Spanish clergy during the 16th century

The Madrid Codex is believed to be a product of the late Mayan period (c. 1400 CE) and is possibly a post-Classic copy of Classic Mayan scholarship. The figures and glyphs of this codex are poorly drawn and not equal in quality to those of the other surviving codices.

The codex contains a wealth of information on astrology and on divinatory practices. It has been of particular value to historians and anthropologists interested in identifying the various Mayan gods and reconstructing the rites that ushered in new years

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

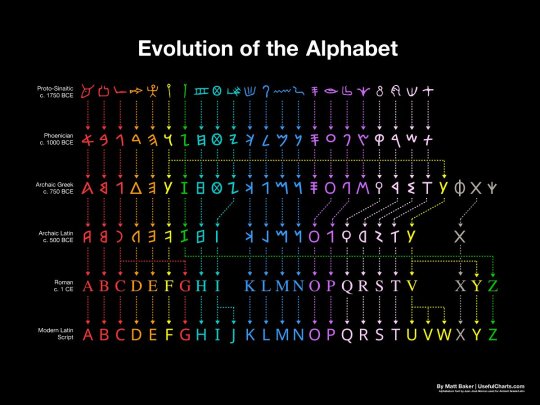

The Evolution of the Alphabet: A Story of Human Ingenuity and Innovation 🤯

How the Alphabet Changed the World: A 3,800-Year Journey

The evolution of the alphabet over 3,800 years is a long and complex story. It begins with the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, which were a complex system of pictograms and ideograms that could be used to represent words, sounds, or concepts. Over time, the hieroglyphs were simplified and adapted to represent only sounds, resulting in the first true alphabets.

The first alphabets were developed in the Middle East, and the Phoenician alphabet is considered to be the direct ancestor of the Latin alphabet. The Phoenician alphabet had 22 letters, each of which represented a single consonant sound. This was a major breakthrough, as it made it much easier to write and read.

The Phoenician alphabet was adopted by the Greeks, who added vowels to the system. The Greek alphabet was then adopted by the Romans, who made some further changes to the letters. The Latin alphabet, as we know it today, is essentially the same as the Roman alphabet, with a few minor modifications.

The English alphabet is derived from the Latin alphabet, but it has undergone some further changes over the centuries. For example, the letters "J" and "U" were added to the English alphabet in the Middle Ages, and the letter "W" was added in the 16th century.

The evolution of the alphabet has had a profound impact on human history. It has made it possible to record and transmit knowledge, ideas, and stories from one generation to the next. It has also helped to facilitate communication and trade between different cultures.

The alphabets are a fascinating invention that have revolutionized the way humans communicate and record information. The history of the alphabets spans over 3,800 years, tracing its origins from the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs to the modern English letters.

Here is a brief overview of how the alphabets have evolved over time:

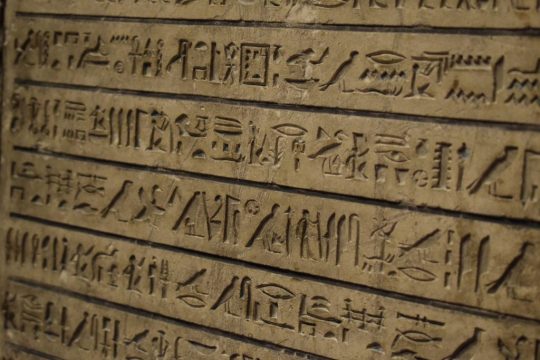

Egyptian hieroglyphs (c. 3200 BC): The earliest form of writing was the pictographic system, which used symbols to represent objects or concepts. The ancient Egyptians developed a complex system of hieroglyphs, which combined pictograms, ideograms, and phonograms to write their language. Hieroglyphs were mainly used for religious and monumental purposes, and were carved on stone, wood, or metal.

Proto-Sinaitic script (c. 1750 BC): Around 2000 BCE, a group of Semitic workers in Egypt adapted some of the hieroglyphs to create a simpler and more flexible writing system that could represent the sounds of their language. This was the first consonantal alphabet, or abjad, which used symbols to write only consonants, leaving the vowels to be inferred by the reader. This alphabet is also known as the Proto-Sinaitic script, because it was discovered in the Sinai Peninsula.

Phoenician alphabet (c. 1000 BC): A consonantal alphabet with 22 letters, each of which represented a single consonant sound. The Proto-Sinaitic script spread to other regions through trade and migration, and gave rise to several variants, such as the Phoenician, Aramaic, Hebrew, and South Arabian alphabets. These alphabets were used by various Semitic peoples to write their languages, and were also adopted and modified by other cultures, such as the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans.

Greek alphabet (c. 750 BC): The Greek alphabet was the first to introduce symbols for vowels, making it a true alphabet that could represent any sound in the language. The Greek alphabet was derived from the Phoenician alphabet around the 8th century BCE, and added new letters for vowel sounds that were not present in Phoenician. The Greek alphabet also introduced different forms of writing, such as uppercase and lowercase letters, and various styles, such as cursive and uncial.

Latin alphabet (c. 500 BC): The Latin alphabet was derived from the Etruscan alphabet, which was itself derived from the Greek alphabet.

Roman alphabet (c. 1 CE): The Roman alphabet is essentially the same as the Latin alphabet, as we know it today. The Latin alphabet was used by the Romans to write their language, Latin, and became the dominant writing system in Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. The Latin alphabet was also adapted to write many other languages, such as Germanic, Celtic, Slavic, and Romance languages.

English alphabet (c. 500 AD): The English alphabet is derived from the Latin alphabet, but it has undergone some further changes over the centuries. For example, the letters "J" and "U" were added to the English alphabet in the Middle Ages, and the letter "W" was added in the 16th century. The English alphabet consists of 26 letters, but can represent more than 40 sounds with various combinations and diacritics. The English alphabet has also undergone many changes in spelling, pronunciation, and usage throughout its history.

The evolution of the alphabet is a remarkable example of human creativity and innovation that have enabled us to express ourselves in diverse and powerful ways. It is also a testament to our cultural diversity and interconnectedness, as it reflects the influences and interactions of different peoples and languages across time and space.

Thank you for reading! I hope you enjoyed the post about the evolution of the alphabet. If you did, please share it with your friends and family. 😊🙏

#evolution of the alphabet#history of writing#alphabet#hieroglyphs#proto-sinaitic script#phoenician alphabet#greek alphabet#roman alphabet#english alphabet#language#linguistics#consonantal alphabet#syllabic alphabet#ancient egyptian#greek mythology

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

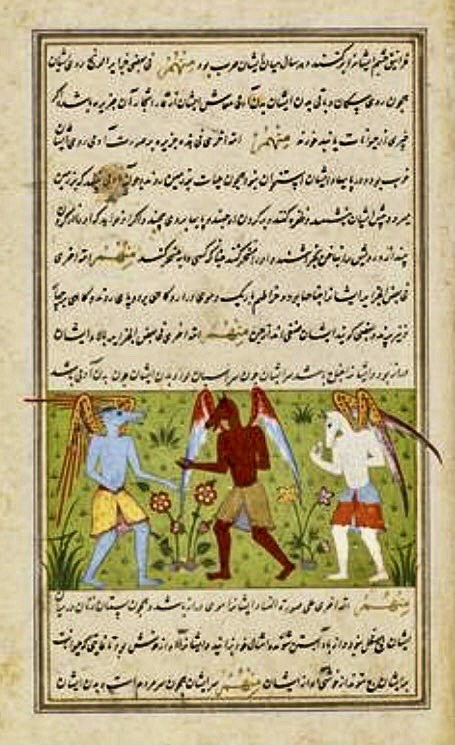

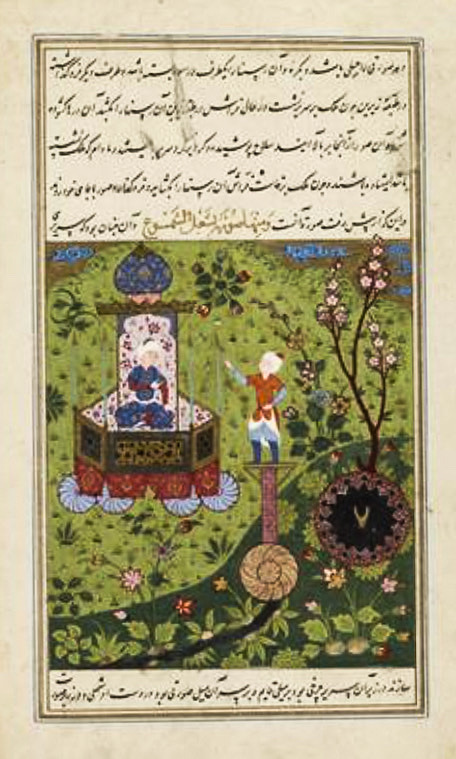

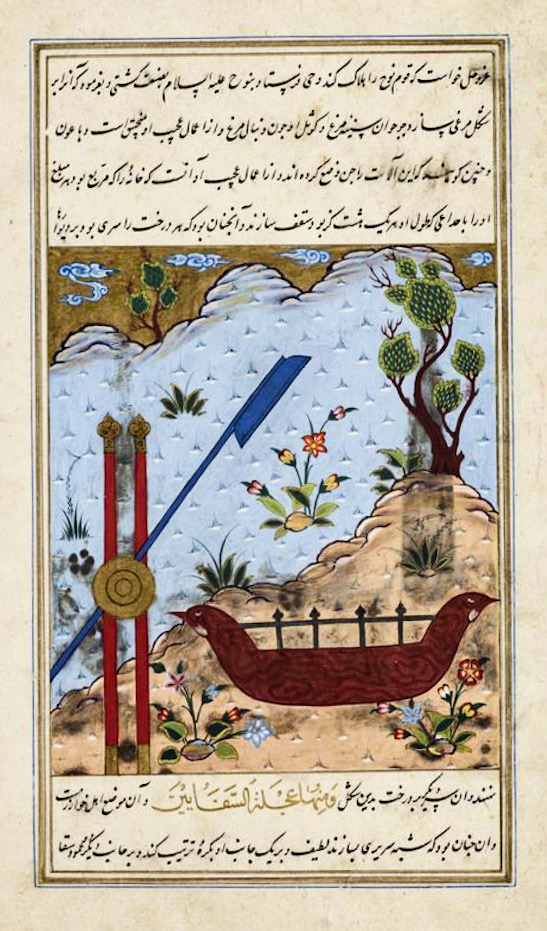

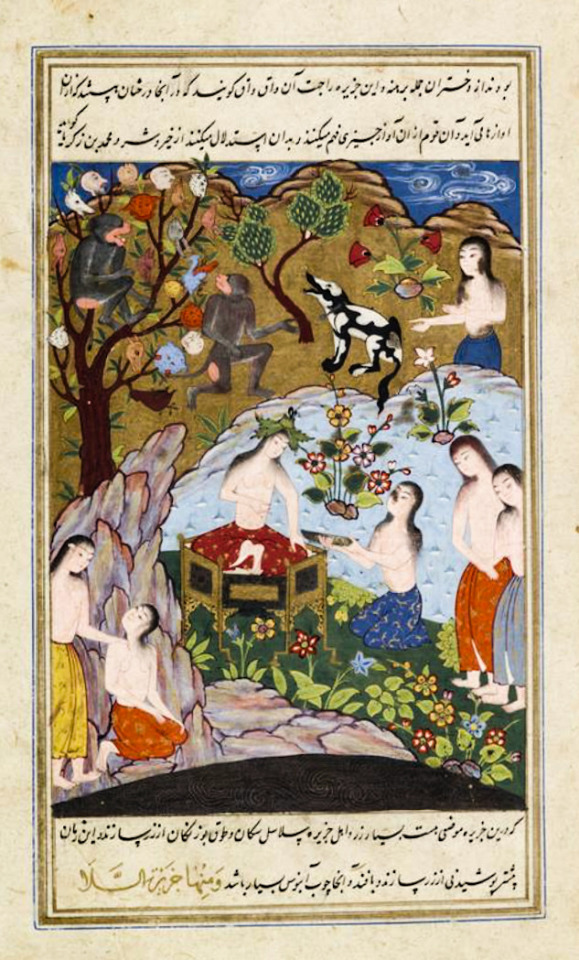

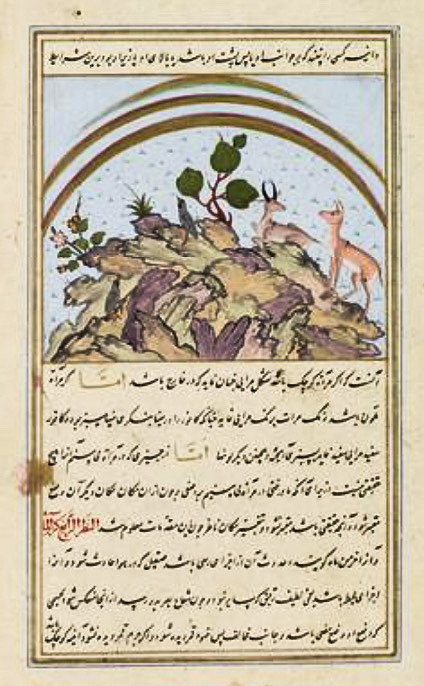

THE COSMOLOGY OF QAZWINI [aka ʻAjāʼib al-makhlūqāt] by Zakarīyā ibn Muḥammad Qazwīnī (c. 1203-1283) Created 974 AH / 1566 CE

A richly illuminated 16th Century [CE] copy of the Persian version of Qazwini's ʻAjāʼib al-makhlūqāt wa-gharāʼib al-mawjūdāt, "The marvels of creation and the oddities of existence", commonly known as "The cosmography of Qazwini"..

The text is structured according to a hierarchical cosmological order, with the celestial spheres, incorporating the fixed stars, the 12 signs of the Zodiac, stellar constellations and the surrounding spheres, which make up the observable celestial phenomena, followed by the invisible phenomena, the "Guardians of the Kingdom of God" and other angels, and the division of time and calendars.

In the second section of the work the elemental division of the sublunar sphere is classified into the four elements fire, wind, water and earth. The seas, oceans and islands including their inhabitants, are governed by Water, while Earth contains the mountains, wells, rivers, minerals, plants and the animal kingdom, including human beings and their cultures.

Numerous illustrations of commonly known mammals, birds, insects and reptiles can be found, along with strange beings, which conclude the text.

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#illustrated book#vintage books#book binding#illuminated manuscript#persian#16th century

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

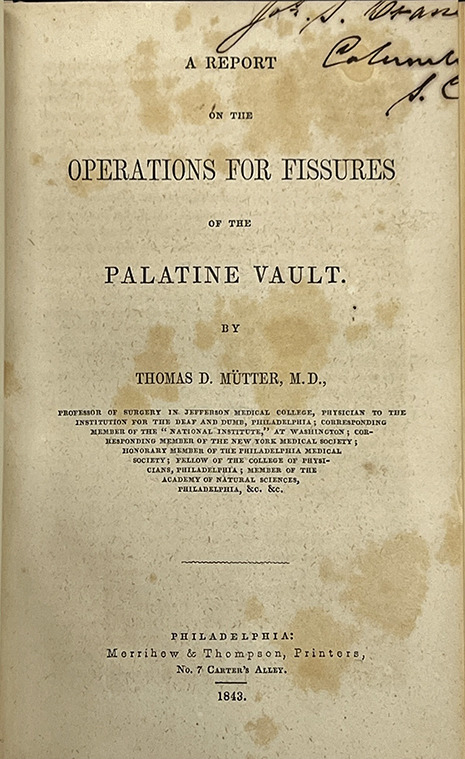

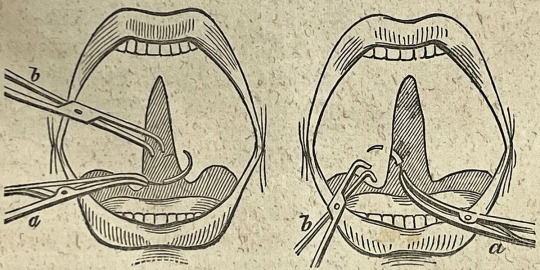

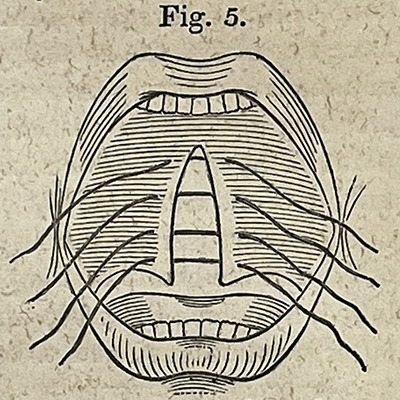

Guest post from John Martin Rare Book Room

At the Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

MÜTTER, Thomas Dent (1811–1859). A report on the operations for fissures of the palatine vault. Printed in Philadelphia by Merrihew & Thompson, 1843. 28 pages. 23 cm tall.

The University of Iowa is a worldwide leader in cleft palate research and repair, so we thought it only appropriate to recognize National Cleft and Craniofacial Awareness Month.

Many of you have no doubt heard of the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, with its famous collection of anatomical specimens and medical instruments. The namesake of the museum, Thomas Dent Mütter, was a 19th-century American surgeon who overcame personal tragedy to become a renowned surgeon and educator.

One area that fascinated him was cleft palate and lip repair. This month's book, A report on the operations for fissures of the palatine vault, written by Mütter and printed in 1843, details his straightforward repair for a cleft palate.

The earliest evidence of cleft lip repair comes from the Jin Dynasty (265-420 CE) in China. The earliest detailed description of a repair is from Jehan Yperman (c.1260–c.1331), a pioneering medieval Flemish surgeon. The first known detailed description of a cleft palate comes from 16th-century French surgeon Pierre Franco (1505-1578). Franco emphasized the importance of the palate to speech development and the congenital origin of the malformation.

Clefts could also be caused by syphilis, however, and during the 16th and 17th centuries, surgical repairs were not advised. Instead, our old friend, Ambroise Paré, along with the Portuguese surgeon Amatus Lusitanus (aka João Rodrigues de Castelo Branco), wrote of using obturators - custom prosthetic devices used to close the palate.

Interest in surgical repair continued, though, especially for congenital clefts. By the 19th century, several Fench surgeons had devised their own methods for repair, including Guillaume Dupuytren, who Mütter trained with while continuing his medical education in Paris.

The Mütter Museum in Philadelphia is celebrated for its collection of anatomical specimens of rare conditions, from the famous (and infamous), as well as medical instruments. The museum was founded with an original donation from the collection of Thomas Dent Mütter.

Mütter was born in 1811 in Richmond, Virginia. Sickness is a common theme in Mütter's life, and he lost both of his parents by the time he was eight. He was raised by a distant relative in a seemingly supportive environment.

Money left to him by his parents allowed him to attend Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia and medical school at the University of Pennsylvania. Mütter himself fell ill during medical school. He left for Europe after graduation in the hopes of improving his health in a different climate and to further pursue his medical education.

In Paris, he worked with the aforementioned Dupuytren and in London with Robert Liston. Mütter eventually put together a collection of lectures by Liston, which he annotated with 250 pages of his own.

Dupuytren was known for his exacting nature and Liston for his speed when performing a surgical procedure (which could mean the difference between life and death in the days before anesthesia and antibiotics). Mütter seems to have embraced the teachings of both his mentors, stressing the need for the simplest of tools and techniques when performing his reconstructive surgeries while trying to keep the pain and blood loss to a minimum.

In 1841, he joined the faculty of the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. It was there that he made a name for himself as an excellent speaker and engaging teacher. He used his ever-expanding anatomical and instrument collection to provide his students with hands-on experience.

Unfortunately, his ill health never truly subsided and he was forced to retire in 1856. He died three years later at the age of 48.

A report on the operations for fissures of the palatine vault demonstrates Mütter's adherence to his surgical principles. It is not a long book, only 28 pages, but it provides insight into his process and surgical philosophy. It includes several small illustrations of the steps of the procedure and the instruments used, examples of which you can see above.

The book is covered in a "library binding" of black cloth and the textblock shows evidence of having been trimmed (see the ownership mark in the upper right corner of the title page above). Indeed, this book was at some point pulled from the circulating Hardin collection and added to the Rare Book Room collection. It still contains the date due slip (last checked out in 1967!) and barcode sticker.

Contact Curator Damien Ihrig to view this tiny but mighty book or any others from this or past newsletters: [email protected] to arrange a visit in person or over Zoom.

#cleft palate#medical#medical history#jmrbr#hardin library#special collections#rare books#uiowa#libraries#Mütter

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Talk] New Research into the History of the Sultanate of Patani (16th‒17th c. CE)

Readers in Taipei may be interested in this talk by Daniel Perret on 30 May about the kingdom of Patani. #talks #efeo #patani

Readers in Taipei may be interested in this talk by Daniel Perret on 30 May about the kingdom of Patani.

The history of the kingdom of Patani, on the east coast of the Thai peninsula along the South China Sea, has attracted scholarly interest for nearly two centuries, mostly due to the important economic role played by this kingdom in Asian trade during the sixteenth and seventeenth…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Prahlada Varada Narasimha shrine, also known as Lakshmi Narasimha temple, is located midst the forest of Lower Ahobilam, Nallamala hills, Andhra Pradesh (the Eastern Ghats). It is about 60 kilometers southeast of Nandyal town (NH 40), 100 kilometers northeast from Tadipatri, and 130 kilometers southeast from the city of Kurnool, Andhra Pradesh.

It is a part of a major historic South Indian pilgrimage site consisting of 10 Narasimha temples (the other nine are in the surrounding hills called the Upper Ahobilam). These are mentioned in the Vaishnavism-related Sanskrit Puranas and the Tamil texts such as the Kancimahatyma as the Navanarasimha-kshetra pilgrimage site. The site is important to Tamils, as the tradition links this site to Kanchipuram mathas and education centers.

All the temples here are dedicated to the Narasimha avatar of Vishnu in the context of Prahlada–Hiranyakasipu mythology, one of the legends behind the Hindu festival of Holi. Per the regional legend, the entire story of man-lion avatar plays out between sites in Tamil Nadu and Ahobilam in Andhra Pradesh. The Vishnu avatar kills the demon-king hiding in Ahobilam to protect and save Prahlada.

The man-lion Narasimha avatar of Vishnu is ancient, and is found in the Brahmana layer of the Vedas (c. 900 BCE).

The Lakshmi Narasimha temple consists of an east-facing sanctum, antarala, major mandapas with numerous pillars and subshrines on the north and south of the main temple. To the north of the main sanctum for Narasimha is a parallel shrine for Lakshmi.

The temple has two gopuras, aligned with each other. These were added post-Vijayanagara era.

There are several inscriptions in the temple, the earliest of which is from 1515 CE at the entrance of the temples complex. These epigraphs help attribute this temple to king Acyutaraya.

One of the mandapa here is almost a copy of the destroyed Vitthala temple in Hampi region.

The temple includes numerous reliefs and statues, including those for Rama, Sita, Hanuman, Vekantesvara, Devi and others.

This temple shows evidence of intentional damage after the 16th-century. Many parts of the temple have been and continue to be restored.

P. Madhusudan

Creative Commons Zero, Public Domain Dedicatione16th century Lakshmi Narasimha temple, Lower Ahobilam, Andhra Pradesh India -

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sextidi 16 Ventôse an CCXXXII

(mardi 5 mars 2024 / Tuesday March 5, 2024)

Le mois de Ventôse dans le calendrier républicain français, correspondant généralement à la période entre le 20 février et le 20 mars, symbolisait le début de la transition vers le printemps. Associé au vent, ce mois était marqué par les premiers signes de renouveau et d'activités agricoles, préparant le terrain pour la saison à venir.

Le 16 Ventôse, dans le calendrier républicain français, était une journée dédiée à l'épinard, un légume vert feuillu apprécié pour sa richesse nutritionnelle et son importance dans l'alimentation.

L'épinard est une plante qui appartient à la famille des Chenopodiacées et est cultivée pour ses feuilles comestibles. Il est originaire d'Iran et est largement cultivé dans de nombreuses régions du monde. Riche en vitamines (notamment en vitamine A, C et K), en minéraux (comme le fer, le calcium et le magnésium) et en antioxydants, l'épinard est réputé pour ses nombreux bienfaits pour la santé.

Le 16 Ventôse était donc l'occasion pour les citoyens de reconnaître l'importance de ce légume dans leur alimentation quotidienne.

En plus de sa valeur nutritionnelle, l'épinard était également apprécié pour sa polyvalence en cuisine. Il pouvait être consommé cru dans des salades, cuit à la vapeur, sauté, ou intégré à une variété de plats tels que les quiches, les soupes et les gratins.

Cette journée était également l'occasion d'encourager la population à cultiver et à consommer des produits locaux et de saison, contribuant ainsi à la promotion d'une alimentation saine et équilibrée.

En célébrant le 16 Ventôse, les citoyens étaient invités à réfléchir à l'importance de l'agriculture, de la santé et de la nutrition dans leur vie quotidienne.

***

The month of Ventôse in the French Republican calendar, generally corresponding to the period between February 20th and March 20th, symbolized the beginning of the transition to spring. Associated with the wind, this month was marked by the first signs of renewal and agricultural activities, preparing the ground for the upcoming season.

The 16th Ventôse, in the French Republican calendar, was a day dedicated to spinach, a leafy green vegetable appreciated for its nutritional richness and importance in diet.

Spinach is a plant belonging to the Chenopodiaceae family and is cultivated for its edible leaves. It originates from Iran and is widely grown in many regions of the world. Rich in vitamins (including A, C, and K), minerals (such as iron, calcium, and magnesium), and antioxidants, spinach is renowned for its numerous health benefits.

The 16th Ventôse was an opportunity for citizens to recognize the importance of this vegetable in their daily diet. In addition to its nutritional value, spinach was also appreciated for its versatility in cooking. It could be consumed raw in salads, steamed, sautéed, or incorporated into a variety of dishes such as quiches, soups, and gratins.

This day was also an opportunity to encourage the population to cultivate and consume local and seasonal products, thereby contributing to the promotion of a healthy and balanced diet. By celebrating the 16th Ventôse, citizens were invited to reflect on the importance of agriculture, health, and nutrition in their daily lives.

#calendrier#calendrier républicain#calendrier républicain français#calendrier révolutionnaire#calendrier révolutionnaire français#france#français#plante#révolution#epinard#16 Ventôse#Ventôse

0 notes

Photo

History & Mining Culture of the Ore Mountains

The Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge) on the border between Germany and the Czech Republic is a region rich in history and culture connected to the mining industry. For centuries the cities on both sides of the mountain range had sustained themselves and flourished by the extraction of tin, copper, zinc, uranium, and most importantly silver. Even though the mines are now closed the mining culture and heritage is still widely celebrated and visible for visitors, with the hammer and chisel motif on many buildings in the different mining towns.

The rich mining heritage of the region was recently inscribed on the UNESCO world heritage list (July 2019 CE), with sites on both sides of the border. On the German side, in the Free State of Saxony, the cities of Freiberg and Annaberg-Buchholz has much to offer in educating visitors about the mining industry, both from the Middle Ages and more recent times and how this intensive industry shaped the lives and culture of the people living there. A visit is definitely recommended for anyone interested in mining history, early industrialization or for those who seek to experience an authentic German Christmas market.

Freiberg

Freiberg, a one-hour train ride from Dresden, traces its history back to 1168 CE. At that time the forest region was under the control of the Margrave of Meissen. A silver ore was discovered close to the small settlement Christiandorf and lead to the establishment of the city of Freiberg, which got its name from the mining rights belonging to the “free miner”. The mining industry became a very important source of income for the Margrave of Meissen, Otto II (r. c. 1156-1190 CE), known later as Otto the Rich. A large statue of the town's 'founder' can now be seen at the main square of the historic city center. Freiberg's importance and wealth increased rapidly after the discovery of silver, and it remained the economic center and mint of Saxony until the 16th century CE. The mining industry continued in the Freiberg region for 800 years until the mines were finally closed in 1968 CE.

Today Freiberg is a lively and charming city with many exciting sites to see, amongst other the Town Hall from the 15th century CE, and the Cathedral of St. Mary, first contracted in 1180 CE as a Romanesque basilica, the current building dates to c. 1500 CE. On the south side of the cathedral, you can visit a part of the old church, The Golden Gate, a richly ornamented sandstone portal from 1230 CE.

Even though the town was destroyed by fire several times and suffered during the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648 CE), much of the medieval town is still standing. Walking around in the historic center, one architectural feature is especially remarkable: the Gothic patrician houses with very high and steep pitched roof constructions. The main square, Obermakt, is definitely worth a visit, where you will see both the statue of Otto the Rich and the beautiful Town Hall. On the north side of the square, you can also marvel at a gate with intricate carvings depicturing the miners hard at work.

It is impossible to visit this city without being drawn towards the rich mining history and culture. To learn more, visitors are recommended to spend a couple of hours in the Freiberg City and Mining Museum. Located in a stunning late Gothic building, it is one of Saxony's oldest museums, established in 1861 CE. The museum is filled with tools, art, photographs, and other objects connected to work in the mines throughout the ages or the culture that flourished thanks to the mining industry. In addition, no one should leave without a visit to the Freudenstein Castle, where the mineral exhibition Terra Mineralia is on display with over 3,500 minerals, precious stones, and meteorites. The exhibition is presented by the Technical University Bergakademie Freiberg, the oldest university of mining and metallurgy in the world, and is a real treasure trove filled with gems from all over the world.

Continue reading...

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feline bowl, Inca (c. 14th-early 16th century CE), stone

On display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring the Rich History: Purana Qila Museum in Delhi

Nestled in the heart of India's bustling capital city, Delhi, lies the majestic Purana Qila (Old Fort) – a historical gem that has withstood the test of time. But the significance of Purana Qila extends beyond its ancient walls. Within this iconic fort, visitors can delve into the cultural kaleidoscope of India's diverse past at the Purana Qila Museum. This article takes you on a journey to explore the fascinating exhibits housed within the museum's walls, shedding light on the rich history and heritage of Delhi and the Indian subcontinent.

A Historical Overview

Purana Qila, believed to have been built by the Afghan ruler Sher Shah Suri during the mid-16th century, stands as a testament to Delhi's glorious past. However, archaeological excavations suggest that the site might have hosted settlements dating back to the pre-Mauryan period (around 1000 BCE). It has witnessed the rise and fall of several empires, including the Mauryas, the Suris, the Mughals, and the British.

The Architecture of Purana Qila

Before diving into the museum's treasures, a glance at the fort's architectural grandeur is essential. Purana Qila is an excellent example of Mughal military architecture, featuring massive walls and imposing gateways. The architectural brilliance is also evident in its three arched entrances: the Bara Darwaza, the Humayun Darwaza, and the Talaqi Darwaza, each adding to the fort's aura.

The Purana Qila Museum

The Purana Qila Museum, situated within the fort's premises, was established with the aim of preserving and presenting Delhi's extensive historical legacy. The museum houses an extensive collection of artifacts, sculptures, and relics that span several periods of Indian history. It offers visitors an immersive experience, taking them on a chronological journey through time.

Galleries and Exhibits

a. Prehistoric Gallery: The journey commences with a prehistoric gallery that showcases artifacts from the ancient Indian civilization, including tools, pottery, and relics from the Indus Valley Civilization. This section provides insights into the lives of the people who once inhabited the region.

b. Maurya-Sunga-Gupta Gallery: As visitors move forward, they encounter artifacts from the Maurya, Sunga, and Gupta periods (3rd century BCE to 6th century CE). Intricately carved statues of deities, terracotta figurines, and exquisite pottery are on display, exemplifying the artistic excellence of these eras.

c. Sultanate and Mughal Gallery: This section transports visitors to the medieval period, showcasing artifacts from the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire. Exquisite calligraphy, metalwork, and paintings reveal the cultural and artistic flourishing of the time.

d. Colonial Gallery: As India's history intertwines with British colonial rule, the museum presents a gallery dedicated to the colonial period. Here, visitors can explore the influence of British culture on Indian society and the struggle for independence.

e. Miscellaneous Gallery: The museum also houses a miscellaneous gallery, featuring an array of artifacts like coins, arms and armor, and textiles, further enriching the visitor's experience.

Educational and Cultural Activities

The Purana Qila Museum offers a range of educational programs and cultural activities, making it an enriching experience for visitors of all ages. Guided tours, workshops, lectures, and cultural events are regularly organized to promote historical awareness and appreciation.

Conclusion

The Purana Qila Museum stands as a window into the illustrious past of Delhi and the Indian subcontinent. With its rich collection of artifacts and exhibits from different epochs, the museum offers a captivating journey through time. From ancient civilizations to the Mughal era, from colonial rule to the struggle for independence, the museum preserves and presents the diverse facets of India's history. A visit to the Purana Qila Museum is not just an exploration of the past; it is an opportunity to connect with the roots of an ever-evolving nation and its vibrant cultural heritage.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Liked on YouTube: What Do We Mean by Hermetic? How the early printing of the Hermetica Shaped our Idea of Hermeticism || https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7JDEP3y9SdY || "Hermeticism" and "Hermetic" are exceedingly elastic concepts capturing a wide and disparate range of ideas - what explains the conceptual elasticity of the concept of something being "hermetic." This episode offers a suggestion that the some of the valances of the term are literally bound up with the texts that were often printed alongside the Corpus Hermeticum. Thus by exploring the printing history of the Corpus Hermeticum we may come to better understand how we conceive of what is and is not 'hermetic.' Consider Supporting Esoterica! Patreon - https://ift.tt/eTKcdkZ Paypal Donation - https://ift.tt/fNwR5OF Merch - https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCoydhtfFSk1fZXNRnkGnneQ/store @TheModernHermeticist - Is the Kybalion Really Hermetic? - https://youtu.be/7rCF6vSeZ3k Sam Block on the Kybalion - https://ift.tt/TiXoZEB 1497 - https://ift.tt/U5QbXi0 1516 - https://ift.tt/TNMDVRC 1532 - https://ift.tt/qhutaXe 1549 - https://ift.tt/Sw2s5zY 1497 Reading List: 1) 'On the mysteries of the Aegyptians, Chaldeans, and Assyrians' by Iamblichus (250-325 CE) (Iamblichus de mysteriis Aegyptiorum. Chaldærum. Assyriorum); 2) 'Commentary on Plato's Alcibiades – on the soul and daimones' by Proclus (412-84 CE) (Proclus in alcibiadem de anima atque dæmone); 3) 'On sacrifice and magic' by the same author (Proclus de sacrificio et magia); 4) 'On deities and daimons' by Porphyrius (c 234-c. 304 CE) (Porphyrius de diuinis atque dæmonibus); 5) 'On dreams' by Synesius (5th century CE) (Synesius Platonicus de somniis); 6) 'On daimons' by Michael Psellus (1018-78 CE) (Psellus de dæmonibus); 7) 'The commentary on Theophrastos's On the senses' by Priscian (6th century CE) and Marsilius (Expositio Prisciani et Marsilii in Theophrastum de sensu. phantasia et intellectu); 8) 'An introduction to the Philosophy of Plato' by Alcinus (2nd century CE) (Alcinoi philosophi liber de doctoria Platonis); 9) 'On Plato's Definitions' by Speusippos, Plato's disciple, (407 BCE-339 BCE) (Speusippi Platonis discipuli liber de Platonis difinitionibus); 10) 'Maxims' and 'Symbols' by Pythagoras (560 BCE-480 BCE) (Pythagoræ philosophi aurea uerba; Symbola); 11) 'On Death' by Xenocrates (c. 396 BCE-34 BCE) (Xenocratis philosophi platonici liber de morte); and 12) 'On pleasure' by Marcilius Ficino (Marcilius ficini liber de uoluptate). 16th Century Reading List: 1) 'On the mysteries of the Aegyptians, Chaldeans, and Assyrians' by Iamblichus (250-325 CE) (Iamblichus de mysteriis Aegyptiorum. Chaldærum. Assyriorum); 2) 'Commentary on Plato's Alcibiades – on the soul and daimones' by Proclus (412-84 CE) (Proclus in alcibiadem de anima atque dæmone); (see O’Neill translation) 3) 'On sacrifice and magic' by the same author (Proclus de sacrificio et magia); 4) 'On deities and daimons' by Porphyrius (c 234-c. 304 CE) (Porphyrius de diuinis atque dæmonibus); 5) 'On daimons' by Michael Psellus (1018-78 CE) (Psellus de dæmonibus) 6) 'Corpus Hermeticum, Asclepius' by Hermes Trismegistus (early c's CE) (Mercurii Trismegisti Pimander. Eiusdem Asclepius)

0 notes