#consonantal alphabet

Text

The Evolution of the Alphabet: A Story of Human Ingenuity and Innovation 🤯

How the Alphabet Changed the World: A 3,800-Year Journey

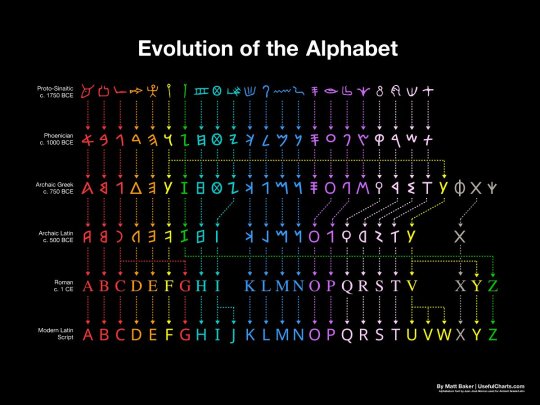

The evolution of the alphabet over 3,800 years is a long and complex story. It begins with the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, which were a complex system of pictograms and ideograms that could be used to represent words, sounds, or concepts. Over time, the hieroglyphs were simplified and adapted to represent only sounds, resulting in the first true alphabets.

The first alphabets were developed in the Middle East, and the Phoenician alphabet is considered to be the direct ancestor of the Latin alphabet. The Phoenician alphabet had 22 letters, each of which represented a single consonant sound. This was a major breakthrough, as it made it much easier to write and read.

The Phoenician alphabet was adopted by the Greeks, who added vowels to the system. The Greek alphabet was then adopted by the Romans, who made some further changes to the letters. The Latin alphabet, as we know it today, is essentially the same as the Roman alphabet, with a few minor modifications.

The English alphabet is derived from the Latin alphabet, but it has undergone some further changes over the centuries. For example, the letters "J" and "U" were added to the English alphabet in the Middle Ages, and the letter "W" was added in the 16th century.

The evolution of the alphabet has had a profound impact on human history. It has made it possible to record and transmit knowledge, ideas, and stories from one generation to the next. It has also helped to facilitate communication and trade between different cultures.

The alphabets are a fascinating invention that have revolutionized the way humans communicate and record information. The history of the alphabets spans over 3,800 years, tracing its origins from the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs to the modern English letters.

Here is a brief overview of how the alphabets have evolved over time:

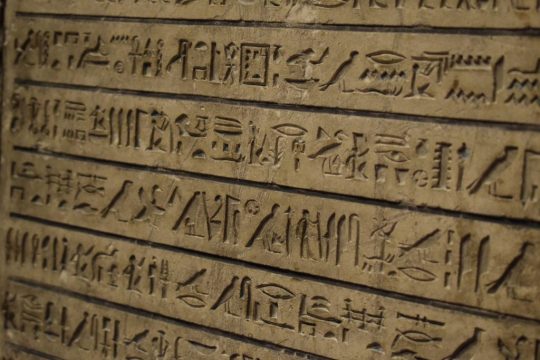

Egyptian hieroglyphs (c. 3200 BC): The earliest form of writing was the pictographic system, which used symbols to represent objects or concepts. The ancient Egyptians developed a complex system of hieroglyphs, which combined pictograms, ideograms, and phonograms to write their language. Hieroglyphs were mainly used for religious and monumental purposes, and were carved on stone, wood, or metal.

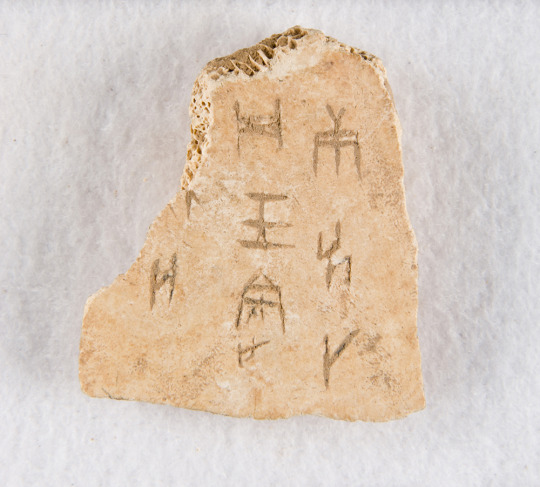

Proto-Sinaitic script (c. 1750 BC): Around 2000 BCE, a group of Semitic workers in Egypt adapted some of the hieroglyphs to create a simpler and more flexible writing system that could represent the sounds of their language. This was the first consonantal alphabet, or abjad, which used symbols to write only consonants, leaving the vowels to be inferred by the reader. This alphabet is also known as the Proto-Sinaitic script, because it was discovered in the Sinai Peninsula.

Phoenician alphabet (c. 1000 BC): A consonantal alphabet with 22 letters, each of which represented a single consonant sound. The Proto-Sinaitic script spread to other regions through trade and migration, and gave rise to several variants, such as the Phoenician, Aramaic, Hebrew, and South Arabian alphabets. These alphabets were used by various Semitic peoples to write their languages, and were also adopted and modified by other cultures, such as the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans.

Greek alphabet (c. 750 BC): The Greek alphabet was the first to introduce symbols for vowels, making it a true alphabet that could represent any sound in the language. The Greek alphabet was derived from the Phoenician alphabet around the 8th century BCE, and added new letters for vowel sounds that were not present in Phoenician. The Greek alphabet also introduced different forms of writing, such as uppercase and lowercase letters, and various styles, such as cursive and uncial.

Latin alphabet (c. 500 BC): The Latin alphabet was derived from the Etruscan alphabet, which was itself derived from the Greek alphabet.

Roman alphabet (c. 1 CE): The Roman alphabet is essentially the same as the Latin alphabet, as we know it today. The Latin alphabet was used by the Romans to write their language, Latin, and became the dominant writing system in Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. The Latin alphabet was also adapted to write many other languages, such as Germanic, Celtic, Slavic, and Romance languages.

English alphabet (c. 500 AD): The English alphabet is derived from the Latin alphabet, but it has undergone some further changes over the centuries. For example, the letters "J" and "U" were added to the English alphabet in the Middle Ages, and the letter "W" was added in the 16th century. The English alphabet consists of 26 letters, but can represent more than 40 sounds with various combinations and diacritics. The English alphabet has also undergone many changes in spelling, pronunciation, and usage throughout its history.

The evolution of the alphabet is a remarkable example of human creativity and innovation that have enabled us to express ourselves in diverse and powerful ways. It is also a testament to our cultural diversity and interconnectedness, as it reflects the influences and interactions of different peoples and languages across time and space.

Thank you for reading! I hope you enjoyed the post about the evolution of the alphabet. If you did, please share it with your friends and family. 😊🙏

#evolution of the alphabet#history of writing#alphabet#hieroglyphs#proto-sinaitic script#phoenician alphabet#greek alphabet#roman alphabet#english alphabet#language#linguistics#consonantal alphabet#syllabic alphabet#ancient egyptian#greek mythology

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

This probably has a pretty obvious answer but I need to know - how do we know how to write in ancient Egyptian? What I mean is, we can read hieroglyphs because of Rossetta stone, but wouldn't that only show us what certain words mean in another language that we do understand, not how it's actually spelled? With names I assume it's easy, but what about actual words, when all we have are symbols and what they correlate with in another language, not actual letters. Sorry if half of that was incorrect, English is not my first language.

I think where your problem lies is that you understand that the Rosetta Stone helped crack the code of reading hieroglyphs, but you're unaware that there were other sources too. I will also say that for Hieroglyphs, the 'symbols' are the letters, we just didn't know their values.

The Rosetta Stone allowed scholars, for the first time, to see three parallel texts all in different scripts. The only one at the time that could be read was the Greek script, so, working with the simple things first, they were able to map the name 'Ptolemy' between all three texts and then started with other words. Once they understood 'okay well this word means king, but we don't know how it sounds' is when they began to use those other sources I mentioned.

One of these sources was another language that is a known descendent of Old/Middle/Late Egyptian and is called Coptic. Now Coptic is still spoken and written, though it is not as widespread as it used to be, so what happened was that Champollion studied it to see how the language worked and how those words sounded. Prior to this, it was decided that each Hieroglyphic sign couldn't be an individual word but had to have a phonetic sound value that when combined in groups formed words. So, armed with that knowledge, Champollion began to find words that appear on the stone and that also appear in Coptic to see if there were similarities. He also looked at how they were using Hieroglyphs to spell known Greek names (like Ptolemy and Cleopatra) because that's a huge indication of a phonetic value of a sign. With Coptic, he knew that the word for 'sun' was 'ⲣⲉ' or 're' and believed that the 𓇳 sign was that of the sun in Hieroglyphs. The contexts in which they were used matched, so it seemed certain that the sign meant 're' or 'ra'.

In his work on deciphering Ptolemy's name in the Hieroglyphs (written as Ptolmes) the 𓋴 sign he'd designated as having the phonetic value of 's' also appeared in the same name at Abu Simbel he'd seen the 𓇳 sign, thus meaning he could potentially read the name 𓇳𓄟𓋴𓋴. We did have names of some kings at this time, and one of them was very well known to be 'Ramesses', thus armed with a sign he knew to be 're' and another he knew to be 's', Champollion surmised that this group of Hieroglyphs must be the name 'Ramesses'. He suggested the 𓄟 must be 'm' and he got further confirmation came from the Rosetta Stone, where the m and s signs appeared together at a point corresponding to the word for "birth" in the Greek, and from Coptic, in which the word for "birth" was ⲙⲓⲥⲉ (mise). We know now that 𓄟 on it's own has the phonetic value of 'ms' so he was pretty close! Another name he used this on was 𓅝𓄟𓋴. The first sign was already known to represent the god Thoth, and taking what he'd learnt from the name Ramesses the two signs at the end must be 'ms' thus making 'thothmes'. Again, known from Mantheo was a king's name 'Thutmosis' so it was very likely to be the same name. From here, he started finding similar Greek and Coptic words and then seeing what they looked like in the hieroglyphs to decipher them and assign them phonetic values. He wasn't entirely right about these. In the latter half of the 19th Century, once Egyptologists had become more comfortable with Hieroglyphs, they were able to see Champollion's mistakes. Champollion believed that each sign only had one value like our alphabet. This was wrong! Signs can have up to 4-consonantal values, but most have only have 2-3 consonantal values. This was demonstrated above with the 𓄟 sign, which Champollion thought was just 1-consonant 'm' but it turned out to be the 2-consonant 'ms'.

After this, it was basically a lot of work understanding how the language fit together (i.e. where the pronouns/definite articles/particles etc) and then we were constantly correcting/updating our understanding of the values of the signs until pretty recently. It still happens to this day, but it's much more infrequent. I think there's only been two changes since 2007 that I know of. These changes are also why Egyptologists will tell you not to use earlier linguistic work unless you know what you're looking at. We're a baby discipline (only just 200 years!) and so a lot of stuff from even 80 years ago is so massively out of date and incorrect (Budge, it's E.A.Wallis Budge) that we beg people not to touch it with a barge pole.

409 notes

·

View notes

Text

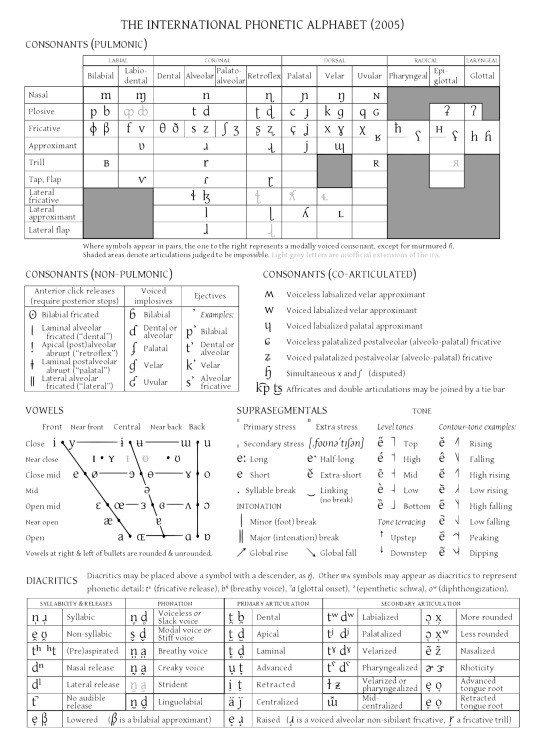

How many different sounds -- reasonably distinguishable by human speakers and listener -- can a language have?

Looking at the table of the International Phonetic Alphabet, consonants are mainly distinguished by place and manner of articulation, which is to say the part of the mouth where the airflow is restricted to produce sound and how that restriction occurs.

The most restrictive consonants are called stops or plosives, which stop the airflow altogether and release it with a burst. The IPA table divides them into seven places of articulation: bilabial (p & b), coronal (t & d), retroflex (ʈ & ɖ, like t & d, but with your tongue curling backward in the mouth, common in Indian languages), palatal (c & ɟ, roughly like ky and gy), velar (k & g), uvular (q & ɢ, similar to k & g but pronounced further back in the mouth), and glottal (ʔ, the Bri'ish glo'al stop) (there is also an epiglottal stop ʡ which I really don't understand). Sometimes you also see labiodental stops (p̪, b̪) pronounced by touching lower lip and upper teeth, like the first sound in the German Pferd. The coronal t & d can be divided in dental, alveolar, and postalveolar, depending on where exactly the tip of your tongue touches your teeth, but distinguishing those is not common. (Though Dahalo distinguishes laminal and apical t & d, so produced with the blade vs. the tip of your tongue). Oh, and there's the labiovelar stops (k͡p, ɡ͡b) of African languages such as Igbo and Yoruba, which actually combines two places into one; and the linguolabial stops made by touching your tongue against your upper lip (t̼, d̼).

The stops in each of these places, except for the glottal, can also be articulated in different ways. The "basic" way is called voiceless (p t k). Then there is voiced articulation, in which your vocal chords vibrate to make the sound slightly more sonorous (b d g). Then they can be aspirated (pʰ tʰ kʰ, compare "t" in "top" vs. "stop": the first is released with a slight puff of air). They can also be both voiced and aspirated at the same time (bʱ dʱ gʱ, like in the original pronunciation of Buddha). Then there are ejectives (pʼ tʼ kʼ, like in Maya), when air is ejected from the mouth without passing through the throat at all, and implosives (ɓ ɗ ɠ, like in Vietnamese), where air goes the other way creating a "gulping" sound. There's such a thing as "nasal" and "lateral release" of stops, but from what I find they are not treated as distinct sounds from the standard form.

So using only stops gives us 10 places (bilabial, labiodental, linguolabial, laminal dental, apical dental, retroflex, palatal, velar, uvular, labiovelar) x 6 (voiceless, voiced, aspirated, voiced + aspirated, ejective, implosive) + 2 (glottal & epiglottal stops) = 62 distinct consonantal sounds. Good start.

The second-most restrictive manner of articulation is that of nasals, which close the mouth completely and redirect air through the nasal passage. The places of articulation are largely the same: bilabial (m), labiodental (ɱ, the "m" in "amphor"), linguolabial (n̼), coronal (n), retroflex (ɳ, like n but curling the tongue backward), palatal (ɲ, like "ni" in "onion" or Spanish ñ), velar (ŋ, like "ng" in "sing"), uvular (ɴ, the "n" in Japanese san), and the co-articulated labial-velar ŋ͡m (like m and ng at the same time). They can be both voiced and voiceless, even though the latter are rare. That makes for 10x2 = 20 nasal consonants.

Then come fricatives, which make hissing or buzzing sounds. Again similar places: bilabial (ɸ β, pronounced with lips almost touching, e.g. the first sound of Japanese Fuji), labiodental (f v), dental (θ ð, the "th" of "thigh" and "thy") linguolabial (θ̼ ð̼, see earlier), alveolar (s z), postalveolar (ʃ ʒ, like the central sounds of "fission" and "vision"), palato-alveolar (ɕ ʑ, like ʃ ʒ but with the tongue pushing forward), retroflex (ʂ ʐ, like ʃ ʒ but with the tongue curling backward), palatal (ç ʝ, the first like the "h" in "hue"), velar (x ɣ, the first like the "ch" in Bach), uvular (χ ʁ, like the previous but further back in the throat), epiglottal (ħ ʕ, don't ask), and glottal (h ɦ). Each of these can, again, be voiceless, voiced, or (except the last two) ejective. There is also a mysterious "palatal-velar" ɧ that seems to exist only in Swedish. I'm counting 11x3 + 2x2 + 1 = 38 fricative sounds.

Actually, there is a second row of lateral fricatives, in which air passses by the sides of the tongue. The most common is coronal (ɬ ɮ, like "ll" in Welsh), but there's also retroflex (ꞎ), palatal (ʎ̝), and velar (ʟ̝). All voiced or voiceless, so 8 more fricatives for a total of 46.

Approximants are yet looser. We got labiodental ʋ (the Hindi pronunciation of "v", kinda halfway between English v and w), coronal ɹ (a common English pronunciation of "r"), retroflex ɻ, palatal j ("y" in "year"), velar ɰ (an extremely soft sound, sometimes "g" between vowels in Spanish), and glottal ʔ̞, which I'm not counting because I think it's the same as a vowel modification we'll get to later. Oh, and then labiovelars (voiced w as in "wealth" and voiceless ʍ as in "whale") and labial-palatal ɥ (as "u" in French nuit). I think they could all be voiced and voiceless, so that's 7x2 = 14 approximants.

But approximants can be lateral too, with what you could call the "L series": coronal l (and its velarized counterpart ɫ as in "lull"), retroflex , ɭ, palatal ʎ (as "gl" in Italian), velar ʟ (as "l" in "alga"), and uvular ʟ̠. So thats 5x2 = 10 more to make 24.

Then taps or flaps. I'm not familiar with these, except that the coronal flap ɾ is how Spanish -r- and American English -tt- may sound between vowels. Then there's bilabial ⱱ̟, labiodental ⱱ, linguolabial ɾ̼, retroflex ɽ, uvular ɢ̆, and epiglottal ʡ̆. Adding the voiceless and lateral (and both) versions recorded in the chart, I get to 15 taps.

Finally there's trills. We get bilabial ʙ (a kind of raspberry sound), coronal r (the "rolled r"), retroflex ɽr (?), uvular ʀ (French "r"), and epiglottal ʜ & ʢ (which are sometimes among fricatives). Add unvoiced for all, and we get 5x2 = 10 trills.

No, wait. There's affricates too, which are really stops + fricatives (including lateral) of the same place of articulation. Each affricate can also be voiced vs. voiceless (except the glottal) and aspirated vs. not (except the epiglottal), so I believe that makes 15x4 + 2 + 1 = 63 affricates.

No, wait. There's still the clicks. They may be used only in languages from Southern Africa, but that's no excuse not to count them. I don't understand them perfectly, but the basic types seem to be bilabial ʘ (basically lip-smacking), dental ǀ (tsk), alveolar ǃ (like doing a clopping sound with your tongue), palatal ǂ, retroflex ‼ (don't ask me about these), and lateral ǁ (a clicking sound with the side of the tongue). Each of them can be voiceless or voiced, aspirated or not, nasalized or glottalized or have 6 types of pulmonic countour or 5 types of ejective contour, plus a preglottalized nasal type and an egressive only for the labial click (please don't ask me). I believe that makes for... 6 x ((4x3) + 6 + 5 + 1) + 1 = 145 potential click sounds, and some Khoisan languages go pretty close to using them all.

That's not quite all -- I haven't counted nasalization or glottalization of most types of consonants, for example, but by my count we have put together 62 stops + 20 nasals + 46 fricatives + 24 approximants + 15 taps + 10 trills + 63 affricates + 145 clicks = 385 distinct consonants sounds.

To be continued with the vowels.

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

#WordyWednesday

Signature marks. The letters and numerals used to label each gathering, typically on the recto side at the bottom. Each gathering would have a symbol and then some of the sheets would be “signed” with that symbol and a number indicating the leaf. Not every leaf in a gathering is usually signed, but only enough leaves to ensure that there was no chance of misfolding the sheets. For an octavo, for instance, this would likely mean that the first three leaves would be signed, e.g., A1, A2, A3, followed by five unsigned leaves. Most printers would use the 23-letter printer’s alphabet to sign their gatherings, but other symbols might be used as well. The printer's alphabet follows the ancient Roman alphabet in that it does not include the letters J, U, or W. (For those who are interested in alphabetology, “J” is merely the consonantal version of the letter “I,” whereas “U” and “W” are variants on the letter “V.”) If a book had more than 23 gatherings, printers would start over at the beginning, often using two letters rather than one (gathering AA, for instance).

#bookhistory#books#typography#rare books#special collections#libraries#university of missouri#mizzou#wordy wednesday#john henry

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I am loving Ts' Íts' àsh and how it’s spoken! I’d love to know if you plan on releasing a full breakdown/alphabet type thing because I would love to learn more about it and how to speak it! I’m already learning parts of it and implementing it into my daily speech to get better at speaking it, especially ashfa. Would love to learn more soon!

Best regards, Samuel

If you're talking about the orthography, I did that here. If you mean the sound system and the romanization, I can do that.

Ts'íts'àsh doesn't have a ton of consonants—very few, in fact. They are as follows (romanized form [IPA]: notes [if any]):

p [p]

b [b]

t [t]

d [d]

t' [t']: this is an ejective consonant

k [k]

k' [k']: this is also an ejective consonant

f [ɸ]: this is a bilabial sound

s [s]

sh [ʃ]

kh [x]

r [r/ɾ]: pronounced like a trill at the beginning or end of a word; otherwise pronounced like a flap

That's it! Nothing too complex. Then there are only four true monophthong vowels:

a [a]

i [i]

o [o]

u [u]

Now this is where things get complicated. Any of the four vowels above or any of the fricatives above can serve as a nucleus. This means you can have a word tkh, psh, or even ss. All of those are licit. You can also have any two vowels in a nucleus—including the fricatives. So while you can only have CVV, you can actually have words like tsá, kshí, or even pskh.

(Small aside: If one of these nucleic fricatives follows an ejective, the ejective marking moves to the right of all the consonants. So a word that begins with k' and then has a nucleus of fó is spelled and pronounced kf'ó.)

There are a number of rules for what happens when two vowels (with vowels including fricatives) come next to one another. The result is too complex to list out in text, so I'm afraid I have to do a table, and since Tumblr doesn't do tables, it has to be visual. Here it is:

So, green means the sequences of vowels are allowed to go together without anything changing. Yellow means the sequence is allowed, but some sort of phonological change occurs. Red means the sequence is disallowed. There is also a general prohibition against three of the same sound in a row, even if one is an onset and two are nuclei. Thus, while ss is licit, sss is forbidden. It is worth noting that several of these vowel-vowel sequences result in monophthongs. This is important for the phonology when it comes to tone assignment. The monophthong sequences are:

*aa > a

*ai > e

*ao/*au > o

*ou/*oo > u

This means that certain instances of the vowels [a], [o], and [u] are phonologically long, and the vowel [e] is also phonologically long (and also brings it up to a five vowel system!). Some other interesting notes:

Long high vowels broke, as in English (so *ii > ai and *uu > au).

The first element of opening diphthongs fortify into a fricative (so *iV sequences become shV and *uV/*oa sequences become fV/fa).

Any time s and sh come next to each other the result is ssh (i.e. [ʃʃ]).

The only consonant f can occur next to as a part of the nucleus is f.

Now, the tones are fairly simple. There are three tones:

High Tone [´]: The vowel is pronounced with high pitch—much the way a vowel is in English when it's stressed.

Low Tone [`]: The vowel is pronounced with low pitch—much the way a vowel is in English when it's unstressed (and also not in front of a stressed vowel).

Falling Tone [ˆ]: The pitch starts off high and falls before leaving the vowel—like when you see a kitty and go, "Awwwwwww!"

How tone is assigned is complex. Good news is if the nucleus is consonantal (just fricatives), there's no tone. Fricatives don't bear tone in Ts'íts'àsh.

The short story for tone is that tone in Ts'íts'àsh came from a combination of an older stress system and cues from onset and coda consonants. An older stressed syllable is called a blaze syllable, and an older unstressed syllable is called a smolder syllable. A smolder syllable will always have low tone unless it has a current or former coda voiceless stop. Then it will have high tone. A blaze syllable can have any tone, but the tone it's assigned depends on the surrounding consonants. Some rules:

If the blaze syllable is open, its tone will be high, unless it begins with a voiced consonant, in which case the tone will be low.

A syllable with one vowel that ends in a voiceless stop will have high tone.

Otherwise, a syllable with a voiced consonant onset will have low tone. The sole exception is a syllable beginning with a voiced consonant that has two vowels and a voiceless stop coda. That syllable will have low tone on the first vowel and high on the second (unless the VV sequence results in a monophthong, in which case the tone is high).

Sequences of two vowels generally have a high-low sequence. The same goes for phonologically long monophthongs.

Coda fricatives will drag tone down.

VV sequences in blaze syllables reduce to singletons in smolder syllables when syllable type shifts in a word (e.g. due to affixation).

And that's all there is to it! It might seem tough to pronounce some sequences we don't have in English, but once you let yourself go and lean into it, it's kind of fun! Jessie and I were both really pleased at how well it was carried off by the actors. They really did a great job!

Thanks for the ask!

#conlang#language#elemental#pixar#pixar elemental#elemental pixar#tsitsash#ts'its'ash#ts'íts'àsh#phonology#phonetics#sir-samuel-iii

73 notes

·

View notes

Note

The runes on Excalibur 👀👀

They’re Nordic, wouldn’t they be Anglo Saxon runes based on the time? Or some sort of Celtic equivalent?

Which. Does the sword = norse or like, type of sword ≠ Norse???

Basically. Just a general Excalibur question and whether it’s historically correct.

Bonus: What do the runes even mean, I know they’re a random sequence and not what they say it means in the show buuttt…. 🤷♀️

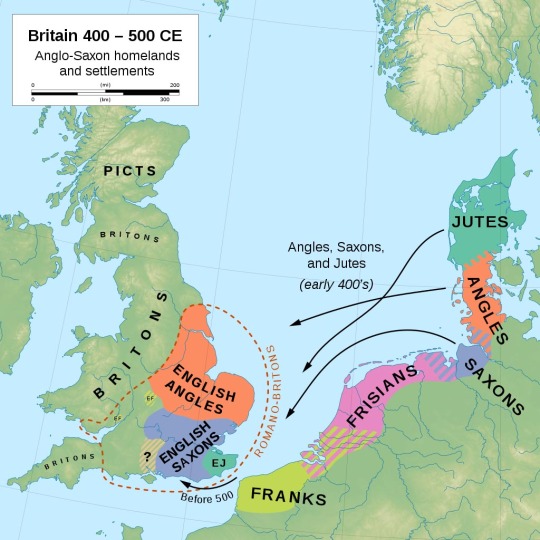

The Problem of Runes

The runes used in the show are Elder Futhark, an anglo-saxon/norseman language in a time when one of the larger enemy forces are the anglo-saxons. Which… doesn’t make a lot of sense. Interestingly, should the sword exist, at the time they'd have used Latin letters, since Romans had already come and begun slowly making people Christian. Funnily enough, Old English only came after Arthur's time in real history. They most likely were also speaking Old Welsh/Hen Gymraeg. I think I may have mentioned it before, who knows, but language is diverse. Language in a post-roman conquest after rome also leaves but anglo-saxons haven’t shown up, even worse. Likely, it wasn’t all simple as it is in the show (due to audience understandings) and likely each Kingdom had its own language/dialect and the different parts of their land also had their own dialects. Likely, around Camelot to Mercia, and back to Caerleon, it’s likely that the language would have links to Latin, at least in the upper class due to Latin being the language of government and writing, but it wouldn’t be the only thing about.

But back to Futhark, my base understanding is that in Britain, there is roughly a period between 400-900 in which artifacts with Runes of this type are found, although they did exist up to 1066 until the Norman Conquest, while King Arthur exists anywhere from 420-1100 (give or take - the show has of course anachronisms[Tomato / Potato / Sandwhich / Silk dresses for Morgana], but it also, then, has dragons).

Also, Ogham may be used if they wanted a more ‘mystic’ feel of inscription. The language is attributed to the Druids, the irish, the pictish, and would use 20 letters.

According to the High Medieval Briatharogam, an irish literature explanation for kennings on the ogham alphabet, trees can be ascribed to specific letters. There is scholarly debate, however, if Ogham is a cipher based on either Germanic runes, Elder Futhark, Greek alphabet, or even Latin. This is due, largely to the “H/Z” letters present in Ogham, but unused in Irish and the vocalic/consonantal variant of “U” vs “W”. And again, at the time, Latin in Roman Britannia, specifically southern and the west, would be prominent (and outside of Ireland, the highest concentration of Ogham is in Wales).

T - Tinne - Holly = Overcoming challenge

A - Ailm - White Fir = Look to past for future understandings

C - Coll - Hazel = Inspire others through skill/wisdom

E - Eadhadh - Poplar = Face challenge with determination

M - Muin - Vine = Trust intuition/Relax

E - Eadhadh - Poplar = Face challenge with determination

U - Ur - Heather = Healing and respite time

P - Peith - soft Birch = New beginnings, change, good fortune

-

C - Coll - Hazel = Inspire others through skill/wisdom

A - Ailm - White Fir = Look to past for future understandings

S - Sail - Willow = Period of learning

T - Tinne - Holly = Overcoming challenge

M - Muin - Vine = Trust intuition/Relax

E - Eadhadh - Poplar = Face challenge with determination

A - Ailm - White Fir = Look to past for future understandings

U - Ur - Heather = Healing and respite time

A - Ailm - White Fir = Look to past for future understandings

Y - Eamhancholl = wisdom/understanding

(Notably Ogham does not have a ‘w’ as a letter so substituting of the sound /u/ is done or with a soft /v/ sound - same with the dual C as there isn’t a K (from what i can tell))

Translation

Based on Arthurian ‘lore’, there are two base sayings that are inscribed on Arthur’s blade “Take me up, cast me away.” This comes from Tennyson'sIdylls of the King, within which the sword is inscribed with the "oldest tongue of all this world". Should the sword be pulled from a rock and anvil, there is often the inscription accompanining it saying "Whoso pulleth out this sword of this stone and anvil is likewise King of all England" (or something to that degree) which is seen in Malory’s works.

To receive an answer of what should be on the sword and what is, is very different. And I am shamelessly pulling from Merlin.fandom as this has been a conversation before. “The runes on the Excalibur in the picture say 'ahefemupwiithstr' which isn't really a word” (https://merlin.fandom.com/f/p/2608657942446217361) However, that’s not to say someone didn’t solve what it should be written as “Translation for "Take Me Up" • Tiwaz - Ansuz - Kenaz - Ewhaz • Mannaz - Ewhaz • Uruz - Perthro • / Translation for "Cast Me Away" • Kenaz - Ansuz - Soliow - Thurasaz • Mannaz - Ewhaz • Ansuz - Wunjo - Ansuz •”

Now, these runes given for the saying do indeed spell out Take me up/Kast me away, this is written with the intention of spelling the words completely assuming no ideography (using what the letters mean[as you ask] rather than what they show: Tiwaz meaning Tyr/Sky god + order/justice / Ansuz meaning As/Odin + order/inspiration/sovereign power / Kenaz being Beacon/Torch + knowledge/tradition/hearth / Ewhaz being Horse + transportation/Steady progress/change / Mannaz meaning Man/Mankind + The Self/human race/mortality / Uruz being Auroch/Ox + Physical Strength/speed/untamed potential / Perthro meaning Lot Cup/Vagina + Feminine Mysteries/occult/secrets/initiation /// Soliow being The Sun + Success/honour/health / Thurasaz(or redoing Tiwaz potentially in the spelling of it) meaning Thorn/Giant + defense/conflict/catharsis/purging / Wunjo being Joy + Comfort/pleasure/harmony --- In my understanding of these, it feels like “take me up” in these runes has indications of taking a throne, bringing in order to the human race, whereas “cast me away” has similar lettering but implicates successes having been done and a conflict having been finished, thus ‘casting away’ the sword once the battle is done).

The show, as mentioned above, has the engraving that translates to 'ahefemupwiithstr' and I’m going to save myself a bit of research and info dumping by going to another source, and I also, unfortunately, don’t know how to link things in Tumblr so we get to suffer screenshots - but do check out the original link: https://dollopheadedmerlin.tumblr.com/post/149429230626/so-guys-im-thinking-of-making-a-replica-of#notes,

Sword Types

Anglo-Saxon swords comprised two-edged straight, flat blades. The tang of the blade was covered by a hilt, which consisted of an upper and lower guard, a pommel (often decorated depending on need and use), and a grip by which the sword was held.

At the time BBC depicts Merlin, the Anglo-Saxons have yet to conquer Britain, thus implying the soldiers wouldn’t likely be using an anglo-saxon sword, however, they could be considering the flow of ideas surpasses the flow of war I suppose.

Excalibur has been depicted from everything from a Roman Gladius (likely in earlier prose when King Arthur existed near the time of Post-Roman Britain, and there are stories with King Arthur and Julius Ceasar meeting, which is very… interesting), to a medieval longsword. Based off the hilt and pommel of Excalibur that we see, it appears to be almost a form of Claymore/Broadsword or Longsword.

However, these range roughly 1100-1700s. In the myths we have, Excalibur is never actually described. However, in modern depictions (film and artwork) it is typically depicted as a form of arming sword, that is, one-handed straight+long-bladed with a double-edge with a crossguard. Which, is reasonable, this style was very popular in the middle ages.

The depiction of Excalibur, in my opinion, is fitting to the 10th and 13th century forms of such swords (the 13th century has that fancy pommel at the end that the sword has in the show). However, your ask was more is this sword norse? Which, the depiction given is kind of in answer, due to the style given at what should be 5th century >< which may look something more similar to this with shorter crossguards while maintaining the circular pommel. Also to note, the term Pommel connects to anglo-normal “little apple” as it was an enlarged fitting at the top of the handle.

#merlin and arthur#the adventures of merlin#bbc merlin#excalibur#runes#elder futhark#anglo saxon#ogham#swords#timeline schenanigans#analysis#arthurian lore

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bible Attributes the Hidden Name of God to Greece

Eli kittim

The Greek New Testament Unlocks the Meaning of God’s Name

The meaning of God’s name (YHVH) was originally incoherent and indecipherable until the appearance of the Greek New Testament. In Isaiah 46:11, God says that he will call the Messiah “from a distant country” (cf. Matt. 28:18; 1 Cor. 15:24-25). Similarly, in Matt. 21:43, Jesus promised that the kingdom of God will be taken away from the Jews and given to another nation. That’s why Isaiah 61:9 says that the Gentiles will be the blessed posterity of God (through the messianic seed). Paul also says categorically and unequivocally, “It is not the children of the flesh [the Jews] … but the children of the promise [who] are regarded as descendants [of Israel]” (Rom. 9:6-8).

These passages demonstrate why the New Testament was not written in Hebrew but in Greek. In fact, most of the New Testament books were composed in Greece. The New Testament was written exclusively in Greek, and most of the epistles address Greek communities. Not to mention that the New Testament authors used the Greek Old Testament as their Inspired text and copied extensively from it. That’s also why Christ attributed the divine I AM to the Greek language (alpha and omega). Now why did all this happen? Was it a mere coincidence or an accident, or is it because God’s name is somehow associated with Greece? Let’s explore this question further.

YHVH (I AM)

Initially, God did not disclose the meaning of his name to Moses (Exod. 3:14), but only the status of his ontological being: “I Am.” The four-letter Hebrew theonym יהוה (transliterated as YHVH) is the name of God in the Hebrew Bible, and it’s pronounced as yahva. In Judaism, this name is forbidden from being vocalized or even pronounced.

Hebrew was a consonantal language. Vowels and cantillation marks were devised much later by the Masoretes between the 7th and 10th centuries AD. Thus, to call the divine name Yahva is a rough approximation. We really don’t know how to properly pronounce the name or what it actually means. But, through linguistic and biblical research, we can propose a scholarly hypothesis.

God Explicitly Identifies Himself with the Language of the Greeks

Since God’s name (the divine “I AM”) was revealed in the New Testament vis-à-vis the first and last letters of the Greek writing system (“I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end” Rev. 22:13), then it necessarily must reflect a Greek name. The letters Alpha and Omega constitute “the beginning and the end” of the Greek alphabet. Put differently, the creator of the universe (Heb. 1:2) explicitly identifies himself with the language of the Greeks! That explains why the New Testament was written in Greek rather than Hebrew. That’s also why we are told “how God First concerned Himself about taking from among the Gentiles a people for his name” (Acts 15:14):

“And with this the words of the Prophets agree, just as it is written, … ‘THE GENTILES WHO ARE CALLED BY MY NAME’ “ (Acts 15:15-17).

This is a groundbreaking statement because it demonstrates that God’s name is not derived from Hebraic but rather Gentile sources. The Hebrew Bible asserts the exact same thing:

“All the Gentiles… are called by My name” (Amos 9:12).

The New Testament clearly tells us that God identifies himself with the language of the Greeks: “ ‘I am the Alpha and the Omega,’ says the Lord God” (Rev. 1:8). In the following verse, John is “on the [Greek] island called Patmos BECAUSE of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus” (Rev. 1:9 italics mine). We thus begin to realize why the New Testament was written exclusively in Greek, namely, to reflect the Greek God: τοῦ μεγάλου θεοῦ καὶ σωτῆρος ἡμῶν ⸂Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ⸃ (Titus 2:13)! Incidentally, God is never once called Yahva in the Greek New Testament. Rather, he is called Lord (kurios). Similarly, Jesus is never once called Yeshua. He is called Ἰησοῦς, a name which both Cyril of Jerusalem (catechetical lectures 10.13) and Clement of Alexandria (Paedagogus, Book 3) considered to be derived from Greek sources.

Yahva: Semantic and Phonetic Implications

If my hypothesis is accurate, we must find evidence of a Greek linguistic element within the Hebrew name of God (i.e. Yahva) as it was originally revealed to Moses in Exod. 3:14. Indeed, we do! In the Hebrew language, the term “Yahvan” represents the Greeks (Josephus Antiquities I, 6). Therefore, it is not difficult to see how the phonetic and grammatical mystery of the Tetragrammaton (YHVH, commonly pronounced as Yahva) is related to the Hebrew term Yahvan, which refers to the Greeks. In fact, the Hebrew names for both God and Greece (Yahva/Yahvan) are virtually indistinguishable from one another, both grammatically and phonetically! The only difference is in the Nun Sophit (Final Nun), which stands for "Son of" (Hebrew ben). Thus, the Tetragrammaton plus the Final Nun (Yahva + n) can be interpreted as “Son of God.” This would explain why strict injunctions were given that the theonym must remain untranslatable under the consonantal name of God (YV). The Divine Name can only be deciphered with the addition of vowels, which not only point to “YahVan,” the Hebrew name for Greece, but also anticipate the arrival of the Greek New Testament!

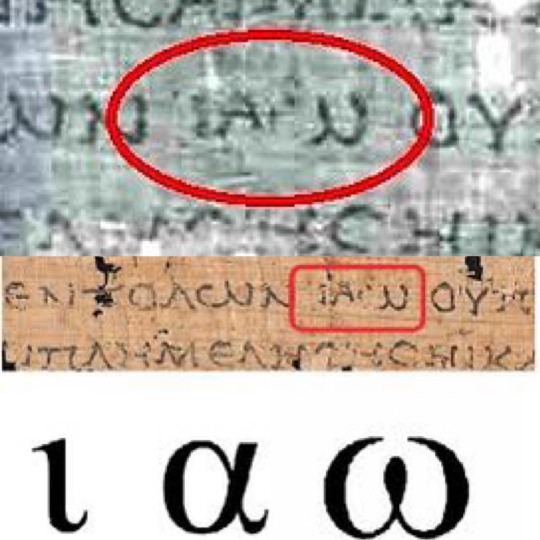

There’s further evidence for a connection between the Greek and Hebrew names of God in the Dead Sea Scrolls. In a few Septuagint manuscripts, the Tetragrammaton (YHVH) is actually translated in Greek as ΙΑΩ “IAO” (aka Greek Trigrammaton). In other words, the theonym Yahva is translated into Koine Greek as Ιαω (see Lev. 4:27 LXX manuscript 4Q120). This fragment is dated to the 1st century BC. Astoundingly, the name ΙΑΩΝ is the name of Greece (aka Ἰάων/Ionians/IAONIANS), the earliest literary records of whom can be found in the works of Homer (Gk. Ἰάονες; iāones) and also in the writings of the Greek poet Hesiod (Gk. Ἰάων; iāōn). Bible scholars concur that the Hebrew name Yahvan represents the Iaonians; that is to say, Yahvan is Ion (aka Ionia, meaning “Greece”).

We find further evidence that the Tetragrammaton (YHVH) is translated as ΙΑΩ (IAO) in the writings of the church fathers. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia (1910) and B.D. Eerdmans, Diodorus Siculus refers to the name of God by writing Ἰαῶ (Iao). Irenaeus reports that the Valentinians use Ἰαῶ (Iao). Origen of Alexandria also employs Ἰαώ (Iao). Theodoret of Cyrus writes Ἰαώ (Iao) as well to refer to the name of God.

Summary

Therefore, the hidden name of God in the Septuagint, the New Testament, and the Hebrew Bible seemingly represents Greece! The ultimate revelation of God’s name is disclosed in the Greek New Testament by Jesus Christ who identifies himself with the language of the Greeks: Ἐγώ εἰμι τὸ Ἄλφα καὶ τὸ Ὦ (Rev. 1:8). In retrospect, we can trace this Greek name back to the Divine “I am” in Exodus 3:14!

#ΌνομαΘεού#יהוה#exodus3v14#Theonym#onomastics#thelittlebookofrevelation#Yahvan#i am#alpha and omega#javan#Yavan#GentileGod#ΙΑΩ#τομικροβιβλιοτηςαποκαλυψης#Yahva#ΙΑΩΝ#GreekGod#ελικιτιμ#orthonym#Elikittim#4Q120#church fathers#Homer#hesiod#dead sea scrolls#hebrew bible#new testament#koine greek#name of god#bible study

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s something I don’t get: the traditional view of Gothic has three values for the diphthongs written ai and au, as short and long monophthongs and a true diphthong respectively, mostly based on etymological arguments from comparison to other Germanic languages, and what values would have been inherited from Proto-Germanic. These digraphs definitely represented monophthongs in at least some places, but some scholars go so far as to argue they only represented monophthongs. The evidence is complicated and unclear--Gothic was spoken across centuries and in various times from the Dnieper to Spain--but one line of evidence includes spellings of Greek names and loanwords like Pawlus and aiwxaristia, where w stands for Greek upsilon. Why (you might argue) would au be pronounced as a diphthong in some Gothic words, but aw be used to write that same diphthong in Greek, if these values are the same?

But they aren’t the same! AFAICT Greek began to move away from the [u] offglide that upsilon represents in those digraphs quite early--well before, in fact, the Gothic Bible was composed. It’s true that early Koine Greek had those diphthongs, but later Koine Greek seems not to have. The w in those loanwords likely corresponds to a labial fricative (a sound for which Gothic had no exact letter, but for which w would be quite suitable), and not to the second element of a diphthong. So it would make sense to spell those two sounds differently, as they were in fact different! There’s still ambiguity there--is w consonantal always or did Gothic have [y] that is sometimes spelled with w, which dialects ultimately monophthongized those diphthongs everywhere and from when, etc.--but none of the resources I’ve encountered on Gothic, when discussing the values of au, mention the fact that the Greek speakers from whom the Goths borrowed their alphabet might not have had that diphthong at all.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing appendix time!

They had reached the stage of full alphabetic development, but older modes in which only the consonants were denoted by full letters were still in use.

So this has always been kind of fascinating to me, since it seems very different from Tolkien’s usual Eurocentrism?

Also while I admit that I don’t know enough about the history of writing, I had the impression that a lot of the consonant focused systems (idk what to call them since I don’t think this case is a proper abjad?) were in some way ultimately derived from scripts originally used to write Afroasiatic languages where it makes a lot of sense because they tend to have consonantal roots. Which is not the case for Quenya.

(Sindarin maybe has some aspects of this? The plural conjugation at least... I don’t know that much Sindarin, sorry. But these systems would have been developed for Quenya from what I can tell.)

I could be wrong about the Afroasiatic origins of course, I don’t know all the writing systems in the world. Maybe there are examples of this sort of thing developing without consonantal roots being involved at all.

The Cirth in their older and simpler form spread eastward in the Second Age, and became known to many peoples, to Men and Dwarves, and even to Orcs, all of whom altered them to suit their purposes and according to their skill or lack of it. [emphasis mine]

Tolkien, please....

The Fëanorian letters are kind of a nightmare to read ngl. I imagine it’s even worse for dyslexic people. I mean they look very pretty, but that’s mostly because THEY ALL LOOK THE SAME. (okay fine they don’t but ykwim)

This script was not in origin an 'alphabet', that is, a haphazard series of letters, each with an independent value of its own, recited in a traditional order that has no reference either to their shapes or to their functions.

Okay, Tolkien lmao

I do find this system very interesting, I don’t know if there’s a good real world counterpart to this? I mean there are familiar elements but the letters not having any kind of predetermined value (even one that would change drastically between languages and eras) seems very unusual. Maybe it was inspired by runic scripts though? I don’t know enough about them to say.

The part where phonetic features are represented with modifications to the letter reminds me of Hangul, though. Did Tolkien know about Hangul?

I have to admit that I’m kinda skimming all this though, I’m sure other people have written about this in more detail. There’s definitely stuff that I feel like I could be paying more attention to but I don’t have the focus right now.

I don’t think I have the energy to really read the spelling section with any sort of proper attention either, maybe I’ll come back to it later idk.

I do find it fun how much thought Tolkien put into this and how chaotic it is. It gives you the vibes of the kind of variation that you get in pre-modern scripts.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

■ Libro a Colori 📔 : »Le Parole più Semplici ↪ Associate ad Ogni Lettera dell' Alfabeto Coreano 🎯 per Facilitare la Memorizzazione 🇰🇷 di Ciascuna Vocale e Consonante 🌟 ↪ Esercitati nella Scrittura 📝 in Lingua Coreana 🇰🇷 a Partire dalle Basi! • ✅*● ✒️ Simple and Short Phrases Combined with Each Letter of the Hangeul ✍️ ! This #koreanbook will help you Learn the Korean Alphabet ▶✏️ …Build the Basics! ✻ Delicate Illustrations 📖🎨 accompany the text…

#vocali#consonanti#lettere#study korean#corea del sud#lingue straniere#lingua coreana#libri#coreano#hangeul#korean books#korean language#alfabeto#korean alphabet

0 notes

Text

What does it mean to survive a war?

The Value in Gematria is 40-56, םהו, "This is." The Hebrew term is atah na, or "Athena", the Greek goddess of the city.

"It's officially a mystery where our noun comes from, but, as we explain in our elaborate article on Hellas, here at Abarim Publications we surmise that much of the essential ideas surrounding information technology — the alphabet itself but also writing materials such as βιβλος (biblos), i.e. paper, spelling standards, even the names Homer, Helen and Hellene — were imported into the Greek world from the Semitic language basin along with the Phoenician abjad (consonantal alphabet). Our noun σφραγις (sphragis) certainly reminds of the important root ספר (spr), which is central to the Hebrew reflections on information technology and which itself may have stemmed from an Assyrian loanword saparu, meaning to send (a message): the Hebrew noun ספר (seper) means record; verb ספר (sapar) means to write; noun ספרה (sipra) means book; noun ספר (sopor) means scribe.

The second part of our noun σφραγις (sphragis) may then relate to the mysterious and powerful αιγις (aigis), which Zeus and Athena carried around with them. It's also officially a mystery what this thing called αιγις (aigis) might have been, but here at Abarim Publications we surmise that it (as well as many more elements of Greek mythology) has to do with the natural contraction of society: the emergence of humanity from the wilderness, the formation of cities and stratified societies, governments and formal law, and ultimately writing and the metaphorical narratives that exposed the deepest dreams and subconscious concerns of mankind.

The first words formed like mist in the natural interactions of vast populations of very early humans (Genesis 2:6). When these first words had achieved a critical mass, language was "discovered": the defining conscious mind of homo sapiens emerged (2:7), words began to be systematically manufactured (2:19-20), rain poured down and the earth was inundated (6:17), and mankind began to create its own human world, peopled by domesticated species and safely separated from the wilderness (8:17). Rain formed rivers and rivers sustained entire civilizations (see our article on the name Tigris).

The Greeks understood all this: the signature epithet of Zeus was νεφεληγερετα (nephelegereta), or Cloud-Gatherer; see our article on the noun νεφελη (nephele), cloud. Athena's epithets were παλλας (pallas), youth; παρθενος (parthenos), virgin (Isaiah 7:14, MATTHEW 1:23), or stemmed from the noun πολις (polis), meaning city.

This noun is used 16 times in the New Testament, SEE FULL CONCORDANCE, and from it derive:

The verb σφραγιζω (spragizo), to seal: to authenticate a document, to close and secure a space, to certify or pledge an object. In the classics this verb was also used metaphorically: one would claim the validity of one's verbal statement by stating that it was "sealed", or give something one's figurative "seal" of approvement. If a thing collided with another thing, it left its "mark" on it. And when some era or period came to an end, one could say that this period had been closed and sealed."

0 notes

Note

Hi there, long time listener (in the sense that I follow CT and they sometimes reblog your stuff), first time caller. So the ancient Egyptians very obviously didn't use the Latin alphabet, and thus didn't put their own writing in forms that English-language keyboards can type out; the current way of transcribing their stuff, which language's orthography is it based on? (Like, how Aztec language is transliterated in a way that made sense to the Spanish, where 'X' sounds like 'sh', instead of the 'ks' that it refers to in English.) Because just among various European languages there's like four different understandings of how 'J' should be said, for example; and 'Q' might or might not have its own distinct sound, depending on what language's transliteration you're looking at. I don't know if this makes any sense, but basically: which language's orthography claimed first dibs on how to write ancient Egyptian sounds?

My apologies if this is something you wouldn't know about; I legit have no idea if "the history of people studying this area of history" is something that gets covered in that field, or if it's a separate field, or if it depends on the program or university.

We use the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), as well as our own transliteration systems created during the translation of Hieroglyphs. These are largely built from the consonantal sounds Champollion was able to find through Coptic (a descendant of the Ancient Egyptian language).

Since transliteration is a system whereby one language script is mapped onto another, Hieroglyphs are merely being mapped onto the Latin script. However, there is currently no one overall system for doing it. This is why you'll find English Egyptologists using =i for the first person pronoun, and German Egyptologists using =j. Nevertheless, they are pronounced roughly the same because we as Egyptologists have assigned sounds to them. This is because we don't actually know how Ancient Egyptian was pronounced. There's a little bit of reconstruction we can do based on Coptic. We can trace certain sounds in the pronunciation of Coptic in the spellings of Egyptian, which is how Champollion managed to translate Hieroglyphs in the first place. So sounds we do 'sort of' know are reflected in the consonantal value they've been assigned in transliteration. We're using, as best we can, the Egyptian/Coptic sounds, not modern sounds. The only time we use modern sounds, and this is where things differ in transcription not transliteration, is when we're inserting vowels in Egyptian words. Since we've not got any concrete sounds for vowels except the very softened form in Coptic, we mostly insert whatever vowel feels best. This is why you find the word imn or Amun being spelt as Amon, or Ax-n-itn Akhenaten spelt as Achenaton.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

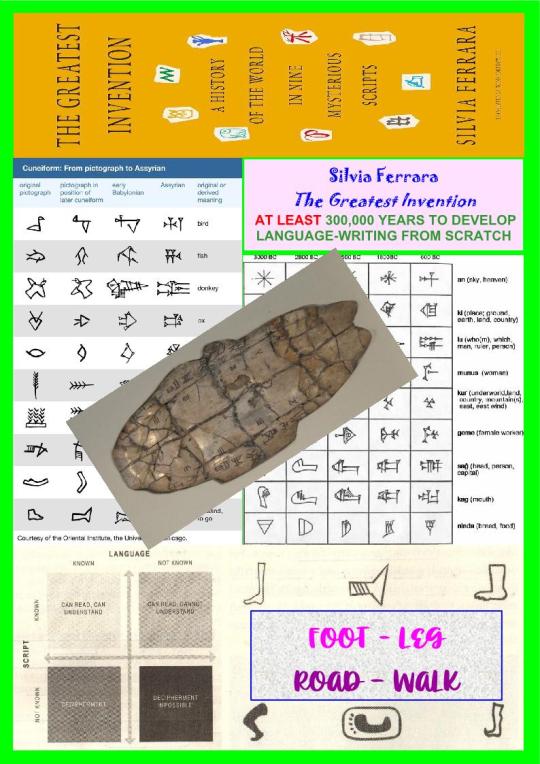

Phylogeny of Writing

The author centers on writing seen both as a human ability and a transcription of oral language, and yet she very heavily refuses there to be any continuity from oral to written language, though once or twice what she says, like in her fifth step about “assigning sounds to signs,” is exactly the reverse of what Homo Sapiens did when he developed writing: he assigned signs to sounds. No matter what way it works for a decipherer and for Homo Sapiens, when he developed some writing system for his/her/their language, and his/her/their language alone in 6-8,000 BCE, the connection between an oral language and its written version are connected, but flexible so that it can be easily replaced by another written code for the very same oral utterances, like the Phoenicians developing the first real consonantal alphabet to replace, for Semitic languages, the Cuneiform writing of the Sumerians (Indo-Iranian) and Akkadians (Semitic), and later on the Greeks adding the vowels of Indo-European languages to the Phoenician alphabet that only had “alep” and only when it was the initial sound or letter of a word.

She alludes to signs in painted caves, hence going back to 45,000 BCE, and all over the world, but she does not exploit it. She acknowledges there were six cradles in the world and does not give them in chronological order, hence does not link them to the general evolution of the concerned human groups, and she neglects the fact that Egyptian writing and Sumerian writing developed at the same time or so but with a strong link between them: the Akkadians were the scribes of the Sumerians and they were Semitic like the Egyptians, whereas the Sumerians were Indo-Iranian coming down from the Iranian Plateau and settling in Mesopotamia before moving on. She mistakenly declares them Turkic, or speaking Turkish, an agglutinative language.

Writing was not an invention because there is no break from pure oral language to written language via representational drawings, and iconic first, totally abstract then signs used to transcribe the oral language into a durable (the media) and sustainable (to be learned by anyone and taught to anyone) script. We have to take the high road leading to discovering the phylogeny of language starting in 475,000 BCE and still developing.

Éditions La Dondaine, Medium.com, 2023

Archaeology, * Anthropology, * Writing, * Written Language, * Oral Language

1 note

·

View note

Text

In 1941 an ambitious Philadelphia pediatrician, the wonderfully named Waldo Emerson Nelson, became the editor of America’s leading textbook of pediatrics. For the next half-century the compilation of successive editions of this large volume advanced his career, consumed his weekends, and encroached heavily on his domestic life. Every few years, when a new edition was being prepared for the press, he would dragoon his family into assembling the index for him. He would read through the proofs of all 1,500 or so pages, calling out the words and concepts to be listed, while his wife, Marge, and their three children—Jane, Ann, and Bill—wrote down on index cards the thousands of entries and their corresponding page numbers.

Though Nelson was a brilliant physician, even his most admiring colleagues were struck by his “austere and stern” appearance, his “façade of gruffness,” his “granite conviction of right and wrong.” “Whenever I talk to my residents,” he once proudly recounted about his treatment of junior doctors, “they never know whether to laugh or cry. That’s the way I like it.” So it’s not surprising to find that when his teenage children complained about their indexing duties, he responded by printing the following dedication at the front of the 1950 edition of what became known as the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics:

Recognizing that children, like adults, prosper under the stimulus and responsibility of a task to be done,

WE ACKNOWLEDGE

the contribution that this book has made to

JANE, ANN, AND BILL

in providing them such privileges, and the satisfaction in family living which has come from group activity

Nowadays we take for granted that any kind of learned book should be indexed, however tedious the labor. So valuable is this tool, so central to our ways of thinking about and using information, that in the case of multivolume scholarly editions of texts, it’s not uncommon for the index itself to constitute an entire book. Yet in the classical world the concept of such a search aid was unknown. To Cicero, an “index” meant a label affixed to a scroll that indicated its contents, rather like the printed spine or dust jacket of a modern volume on a bookshelf. As Dennis Duncan notes in his clever, sprightly Index, A History of the, the rise of the index in its current form is a story of many interrelated developments, each with its own contingencies and chronology: the replacement of scrolls by the codex, the triumph of alphabetical order, the rise of new pedagogies and genres of learning, the invention of print, the adoption of the page number, and the constantly changing character of reading itself.*

Take alphabetical order. Even though the consonantal alphabet had been around since the early second millenium BCE, the earliest known examples of its application as an organizing principle date only from about the third century BCE. The now lost 120-scroll catalog of the Library of Alexandria listed authors partly in alphabetical order. That the ancient Greeks were fond of using it is evident in everything from their fishmongers’ price lists to records of taxpayers and monuments to playwrights (the background panel of one surviving marble statuette of Euripides lists the titles of his plays from alpha to omega).

Yet after them the Romans largely disdained the alphabetical principle as arbitrary and illogical, and so did Europeans throughout the Middle Ages. Books about words—like lexicons, grammars, and glosses—employed it, but it was not a widely understood rule. As late as 1604 the first printed dictionary of English, Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabeticall, was obliged to begin by explaining that its readers should attend to

the Alphabet, to wit, the order of the Letters as they stand…and where euery Letter standeth: as (b) neere the beginning, (n) about the middest, and (t) toward the end. Nowe if the word, which thou art desirous to finde, begin with (a) then looke in the beginning of this Table, but if with (v) looke towards the end. Againe, if thy word beginne with (ca) looke in the beginning of the letter (c) but if with (cu) then looke toward the end of that letter.

The term “index” didn’t come to be used in its current sense in English until quite recently. There’s no entry for it in Cawdrey, while Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) defined it as “the table of contents to a book.” For centuries words like “table,” “register,” and “rubric” were used interchangeably for what we now call indexes and contents pages: only very gradually, over the past two hundred years or so, have the two forms come to be regarded as essentially distinct. (The related Anglophone convention that indexes appear at the back of books and contents pages at the front seems to have been part of a similar, relatively recent process of separating them.) Nonetheless, names aside, the alphabetical index as a type of textual technology turns out to be much older than that.

There are two basic types, which in modern books are usually combined into a single list. One type collates words, the other concepts. The former is a concordance, the latter a subject index. The first is the kind of literal, specific listing of entries that you can get your computer to produce by using CTRL+F for any word or phrase in a text; the second is the product of a more subjective, humanistic attempt to capture the meanings and resonances of a work. Duncan, understandably, is mainly interested in the evolution of the latter type—even though, because of the rise of the word-based online search engine, we now find ourselves living in a golden age of the concordance. But the two forms need to be treated together, he argues, because both were invented at the same time and place: in northwestern Europe, in or around 1230.

The index was, in fact, part of an entire range of organizational and reading tools that were conceived in the thirteenth century. (Others included the division of the Bible into standard chapters and the genre of distinctiones, a new kind of search aid for preachers that helpfully grouped together biblical extracts on the same subject.) Two social developments at this time created a novel demand for information to be organized in rapidly accessible ways: the foundation of the first European universities and the rise of the new orders of mendicant friars, with their stress on the frequent and engaging preaching of God’s word. In Oxford the scholar and cleric Robert Grosseteste (so named, it was said, because of his gigantic brain) compiled an enormous subject index to the whole of the world’s knowledge, to aid him and his students in navigating it all. His Tabula, of which only a fragment survives, encompassed the entirety of the Bible, the writings of the Church Fathers, the works of classical authors like Aristotle and Ptolemy, and Islamic authorities including Avicenna and al-Ghazālī.

Meanwhile, in Paris, the Dominican Hugh of Saint-Cher (soon to become the first person ever to be painted wearing reading glasses) oversaw the compilation of an even more stupendous alphabetical word index. This was the first concordance to the Bible, listing over 10,000 of its keywords with all their locations, from the exclamation “A, a, a” (now usually translated as “ah!”) all the way to “Zorobabel,” the sixth-century-BCE governor of Judea.

Soon enough, medieval readers were making their own indexes to volumes they owned. The invention of printing brought further refinements. Page numbers had already been used to number the leaves of individual manuscripts, but the uniformity of printed books gave them a different utility, as a means of referring to the same place across different copies of the same work. It took time for this idea to catch on. The first printed page number was not produced until 1470; even by 1500 only a small minority of books had adopted the practice. Instead, early printed indexes referred to textual locations or to the signature marks at the bottom of pages (“Aa,” “b2,” and the like), which printers and binders used to keep their finished sheets in the correct order. But in the course of the sixteenth century, use of the page number spread, alongside the creation of increasingly sophisticated indexes by scholarly authors.

As early as 1532, Erasmus published an entire book in the form of an index because, he quipped, these days “many people read only them.” A few years later his colleague Conrad Gessner, one of the greatest indexers of his day, rhapsodized about how this new search tool was transforming scholarship:

They are the greatest convenience to scholars, second only to the truly divine invention of printing books by movable type…. Truly it seems to me that, life being so short, indexes to books should be considered as absolutely necessary by those who are engaged in a variety of studies.

Like every widely observed change in reading and learning habits before and since (the invention of writing, the launch of Internet search engines, the spawning of ChatGPT), the spread of the index was accompanied by anxiety that flighty, superficial modes of accessing information were supplanting “proper” habits of reading and understanding. In the sixteenth century Galileo complained that scientists seeking “a knowledge of natural effects, do not betake themselves to ships or crossbows or cannons, but retire into their studies and glance through an index or a table of contents.” To “pretend to understand a Book, by scouting thro’ the Index,” jibed Jonathan Swift in 1704, was the same “as if a Traveller should go about to describe a Palace, when he had seen nothing but the Privy.” Yet as Duncan wisely points out, our intellectual habits are always changing, and for good reason. Every social and technological shift affects how we read—and we also all read in many different ways. Twitter, novels, text messages, newspapers: each demands a different kind of attention. The older we get, the more invested we are in modes of reading that we’re familiar with and the more suspicious of technologies that seem prone to disrupt them.

The eighteenth century produced a great efflorescence of indexing novelties, jokes, and experiments, which Index, A History of the has great fun cataloging. For a while it seemed as if indexes might become part of almost every genre of writing, including epic poetry, drama, and novels; the inclusion of an index had become a literary status symbol, a sign that a text was prestigious or that a book had been lavishly produced. Alexander Pope’s multivolume, best-selling translation of the Iliad, which earned him a fortune,included several grand, exhaustive, and intricate tables and indexes (including one listing the emotions in Homer’s work, all the way from “Anxiety” to “Tenderness”).

In the 1750s Samuel Richardson produced an eighty-five-page index to his enormous novel Clarissa. (It included its own index to the index.) This wasn’t really a reference for the main text, but more like a summary of the moral lessons contained in the original, seven-volume, million-word monster of a book. He called it “a table of sentiments” or (to give it its full title) “A Collection of such of the Moral and Instructive Sentiments, Cautions, Aphorisms, Reflections, and Observations, contained in the History of Clarissa, as are presumed to be of General Use and Services, digested under Proper Heads,” and toyed with the idea of publishing it separately as a work in its own right. But Richardson, who started out as a printer, was an outlier in his love of indexing (he also later produced a huge unified index to all three of his novels), and this proved to be a largely abortive branch of literary evolution. After all, names and facts are rather easier to index than thoughts and feelings.

Instead, by the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the textual forms of fiction and nonfiction had grown increasingly distinct. The latter were ever more energetically and impressively indexed. In the 1850s Jacques Paul Migne’s monumental collection of the writings of the Church Fathers, in 217 volumes, was accompanied by an equally humongous four-volume index, which was produced by a team of more than fifty laboring for over a decade and was itself divided into no less than 231 parts. There were indexes by author, subject, title, date, country, rank (popes before cardinals, cardinals before archbishops, and so on), genre, and hundreds of other categories—including separate indexes to heaven and hell.

Toward the end of the century, librarians from around the world combined forces to produce a universal, international index of all the most important books and knowledge in existence—as well as, on a more modest but still extraordinary scale, the first global indexes to the flood of periodical publications. In modern fiction, on the other hand, indexing by this time largely appeared only as a literary conceit: a play on genre, fictionality, and facticity. Both Vladimir Nabokov and J.G. Ballard wrote stories that used the index form (in both of which the last entry, at the end of the Z’s, reveals a final twist of the plot).

Duncan is a brilliantly illuminating and wide-ranging guide across this richly varied terrain, though his cast of characters remains overwhelmingly male. He notes in passing that since the 1890s, with the emergence of secretarial agencies, indexers have been largely female, and that today they are overwhelmingly so—including the compiler of his own book’s fine index, Paula Clarke Bain. Unfortunately he doesn’t pursue the point. Yet the gendered, patriarchal hierarchy of labor through which twentieth-century scholarly indexes were commonly produced is fascinatingly evoked by the prefaces to countless books of the era.

In 1983, at the conclusion of his monumental eleven-volume edition of the diary of Samuel Pepys, the lead editor, Robert Latham, compiled what is often regarded as the finest index ever produced in English. Thirteen years earlier, the first volume in the series had appeared in harrowing circumstances: just as it was going to press, his wife, Eileen, to whom he had been married for thirty years, suddenly died. “The late Mrs Robert Latham read many of the proofs,” the anguished editor recorded at the end of his acknowledgments, in the standard, buttoned-up phraseology of midcentury male academic prose. “Beyond that, she gave help which can never be measured.”

By the time he composed the acknowledgments to the index volume, Latham had happily remarried, and the sexual revolution had passed even through Cambridge. His remarks now conjured a more relaxed, less overtly chauvinist world—as well as providing an appealing vignette of familial indexing in practice:

My wife Linnet has shared in the making of this Index. I laid down the ground plan, but she involved herself in every process of its construction. She read aloud the entire text of the diary while I took notes—discussing with me, as we went along, exactly what words might best introduce the successive groups of references, and thus converting what might have been a chore into a paper-game. At later stages she undertook innumerable investigations into detail, and checked from the text every reference in the typescript.

“As a joint enterprise with his wife’s energy and powers of organization, and with a text so entertaining,” he elaborated to the Society of Indexers,

the work in fact often spilled over into hilarity, becoming a game rather than a job. Indeed indexing itself may be seen as a word game, seeking the appropriate word for comprehensive headings or verbal formulas for a whole series of related subjects; Mrs Latham’s expertise in word games accounted for many of their solutions found.

Not every such marital collaboration around this time was as harmonious. In the mid-1970s the new lead author of America’s standard textbook on obstetrics, Jack Pritchard, asked his wife, Signe, to prepare the index for him. They had been married for thirty years. She was a nurse, a mother, and a feminist who had recently changed her title to “Ms.”; his textbook was suffused with attitudes toward women and their bodies that evidently infuriated her. When the index appeared, it turned out that she had included the line “Chauvinism, male, variable amounts, 1–923” (i.e., on every page of the book). Four years later, for the next edition, she improved this to “Chauvinism, male, voluminous amounts, 1–1102” and added, for good measure, another judgment on the whole enterprise: “Labor—of love, hardly a, 1–1102.”

Perhaps she had heard about the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.A few months after Ann Nelson’s father completed the sixth edition of his book, she went off to college. On graduating in 1954 she wed an aspiring lawyer, Richard E. Behrman. Before agreeing to marry him, he later recalled, “Ann made him promise never to ask her to help him write a textbook.” But within a few years, as the seventh edition neared completion, her domineering father demanded that Ann (now referred to as “Mrs. Richard E. Behrman”) and her siblings once more rally around to help him make its index. So she did—and paid him back by adding an entry of her own. Under “Birds, for the,” she listed the entire book, pages 1–1413. Never cross your indexer.

0 notes

Text

In 1941 an ambitious Philadelphia pediatrician, the wonderfully named Waldo Emerson Nelson, became the editor of America’s leading textbook of pediatrics. For the next half-century the compilation of successive editions of this large volume advanced his career, consumed his weekends, and encroached heavily on his domestic life. Every few years, when a new edition was being prepared for the press, he would dragoon his family into assembling the index for him. He would read through the proofs of all 1,500 or so pages, calling out the words and concepts to be listed, while his wife, Marge, and their three children—Jane, Ann, and Bill—wrote down on index cards the thousands of entries and their corresponding page numbers.

Though Nelson was a brilliant physician, even his most admiring colleagues were struck by his “austere and stern” appearance, his “façade of gruffness,” his “granite conviction of right and wrong.” “Whenever I talk to my residents,” he once proudly recounted about his treatment of junior doctors, “they never know whether to laugh or cry. That’s the way I like it.” So it’s not surprising to find that when his teenage children complained about their indexing duties, he responded by printing the following dedication at the front of the 1950 edition of what became known as the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics:

Recognizing that children, like adults, prosper under the stimulus and responsibility of a task to be done,

WE ACKNOWLEDGE

the contribution that this book has made to

JANE, ANN, AND BILL

in providing them such privileges, and the satisfaction in family living which has come from group activity

Nowadays we take for granted that any kind of learned book should be indexed, however tedious the labor. So valuable is this tool, so central to our ways of thinking about and using information, that in the case of multivolume scholarly editions of texts, it’s not uncommon for the index itself to constitute an entire book. Yet in the classical world the concept of such a search aid was unknown. To Cicero, an “index” meant a label affixed to a scroll that indicated its contents, rather like the printed spine or dust jacket of a modern volume on a bookshelf. As Dennis Duncan notes in his clever, sprightly Index, A History of the, the rise of the index in its current form is a story of many interrelated developments, each with its own contingencies and chronology: the replacement of scrolls by the codex, the triumph of alphabetical order, the rise of new pedagogies and genres of learning, the invention of print, the adoption of the page number, and the constantly changing character of reading itself.*

Take alphabetical order. Even though the consonantal alphabet had been around since the early second millenium BCE, the earliest known examples of its application as an organizing principle date only from about the third century BCE. The now lost 120-scroll catalog of the Library of Alexandria listed authors partly in alphabetical order. That the ancient Greeks were fond of using it is evident in everything from their fishmongers’ price lists to records of taxpayers and monuments to playwrights (the background panel of one surviving marble statuette of Euripides lists the titles of his plays from alpha to omega).

Yet after them the Romans largely disdained the alphabetical principle as arbitrary and illogical, and so did Europeans throughout the Middle Ages. Books about words—like lexicons, grammars, and glosses—employed it, but it was not a widely understood rule. As late as 1604 the first printed dictionary of English, Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabeticall, was obliged to begin by explaining that its readers should attend to

the Alphabet, to wit, the order of the Letters as they stand…and where euery Letter standeth: as (b) neere the beginning, (n) about the middest, and (t) toward the end. Nowe if the word, which thou art desirous to finde, begin with (a) then looke in the beginning of this Table, but if with (v) looke towards the end. Againe, if thy word beginne with (ca) looke in the beginning of the letter (c) but if with (cu) then looke toward the end of that letter.

The term “index” didn’t come to be used in its current sense in English until quite recently. There’s no entry for it in Cawdrey, while Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) defined it as “the table of contents to a book.” For centuries words like “table,” “register,” and “rubric” were used interchangeably for what we now call indexes and contents pages: only very gradually, over the past two hundred years or so, have the two forms come to be regarded as essentially distinct. (The related Anglophone convention that indexes appear at the back of books and contents pages at the front seems to have been part of a similar, relatively recent process of separating them.) Nonetheless, names aside, the alphabetical index as a type of textual technology turns out to be much older than that.

There are two basic types, which in modern books are usually combined into a single list. One type collates words, the other concepts. The former is a concordance, the latter a subject index. The first is the kind of literal, specific listing of entries that you can get your computer to produce by using CTRL+F for any word or phrase in a text; the second is the product of a more subjective, humanistic attempt to capture the meanings and resonances of a work. Duncan, understandably, is mainly interested in the evolution of the latter type—even though, because of the rise of the word-based online search engine, we now find ourselves living in a golden age of the concordance. But the two forms need to be treated together, he argues, because both were invented at the same time and place: in northwestern Europe, in or around 1230.