#1902 Letters & Diary entries

Text

1902

Letter excerpt from Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna to Princess Marie of Romania

Nice, 25 February 1902

Ducky's humour has improved since her daughter left: I think she really cannot stand Wilson any more after having been greatly disappointed in her. Again, all her own fault, as she had made a confidente of her, never reflecting, that one servant out of a thousand can stand it. Now comes the inevitable result, where Wilson has turned against her... I gently bring Ducky to bear in view the possibility of parting with her soon. The child does not want a nurse and she has now a lady Georgina Rotsmann, which I thought a good choice.

Princess Elisabeth of Hesse, standing between her nanny Miss Wilson and Victoria Melita during an exhibition in 1900.

source: My dear Mama by Diana Mandache.

photo: my collection

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tags

[Sometimes updated]

NAOTMAA

(Nicholas, Alexandra, Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia and Alexei)

Nicholas II of Russia (1868 - 1918)

Alexandra Feodorovna (1872 - 1918) | Princess Alix of Hesse

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna (1895 - 1918)

Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna (1897 - 1918)

Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna (1899 - 1918)

Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna (1901 - 1918)

Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich (1904 - 1918)

OTMAA

OTMA

Russian Relatives

Alexander II (1818 - 1881)

Maria Alexandrovna (1824 - 1880)

Tsesarevich Nikolai (1843 - 1865)

Alexander III (1845 - 1894)

Princess Eugenia Maximilianovna of Leuchtenberg (1845 - 1925)

Maria Feodorovna (1847 - 1928)

Catherine Dolgorukova (1847 - 1922)

Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna (1853 - 1920)

Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna the Elder (1854 - 1920)

Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich (1857 - 1905)

Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich (1858 - 1915)

Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich (1866 - 1933)

Grand Duke George Alexandrovich (1871 - 1899)

George Alexandrovich Yuryevsky (1872 - 1913)

Olga Alexandrovna Yurievskaya (1873 - 1925)

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna (1875 - 1960)

Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich (1878 - 1918)

Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna (1882 - 1960)

Princess Irina Alexandrovna (1895 - 1970)

Tikhon Nikolaevich (1917 - 1993)

Guri Nikolaevich (1919 - 1984)

Hesse Relatives

Grand Duke Louis IV (1837 - 1892)

Princess Alice (1843 - 1878)

Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine (1863 - 1950) | Princess Victoria of Battenberg

Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna (1864 - 1918)

Princess Irene of Hesse and by Rhine (1866 - 1953)

Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse (1868 - 1937)

Eleonore of Hesse (1871 - 1937)

Princess Elisabeth of Hesse and by Rhine (1895 - 1903)

British Relatives

Queen Victoria (1819 - 1901)

Victoria, Princess Royal (1840 - 1901)

Edward VII (1841 - 1910)

Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1844 - 1900)

Alexandra of Denmark (1844 - 1925)

Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll (1848 - 1939)

George V (1865 - 1936)

Louise, Princess Royal (1867 - 1931)

Princess Victoria of Wales (1868 - 1935)

Princess Maud of Wales (1869 - 1938)

Princess Helena Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein (1870 - 1948)

Grand Duchess Victoria Feodorovna (1876 - 1936)

Other Royals

Elisabeth of Austria (1837 - 1898)

Diary Entries

Queen Victoria

Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich

Nicholas II

Grand Duchess Xenia Alexandrovna

Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna

Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna

Years

1840s

1849

1850s

1856

1860s

1862

1863

1864

1865

1870s

1872

1873

1874

1875

1877

1878

1880s

1880

1881

1882

1884

1885

1886

1887

1888

1889

1890s

1891

1893

1894

1895

1896

1897

1898

1899

1900s

1900

1901

1902

1903

1904

1905

1906

1907

1908

1909

1910s

1910

1911

1912

1913

1914

1915

1916

1917

1918

Pairs

The Big Pair

The Little Pair

Other People (friends, officers, staff, ect)

Anna Vyrubova (1884 - 1964)

Margarita Sergeevna Khitrovo (1895 - 1952)

Nikolai Pavlovich Sablin (1880 - 1937)

Butakov Alexander Ivanovich (1881 - 1914)

Pavel Voronov (1886 - 1964)

Catherine Schneider (1856 - 1918)

Princess Sonia Orbeliani (1875 - 1915)

Mathilde Kschessinska (1872 - 1971)

My Stuff

My Edits

My Restorations

My Colourisations

Palaces

Peterhof Palace

Moika Palace

Vladimir Palace

Pavlovsk Palace

Alexander Palace

Series

Family Resemblance Series

Portrayal vs The Real Romanovs

Sunny Being Sunny

Other Tags

Asks

Quotes

Reblogs

Edits

Clothing

Undated

Gifs

Letter Extracts

Full Letters

Colourisations

Art

Close-Ups

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yes, It’s All About You (in Writing, Anyway)

I recently noticed that in every one of my novels—five of them now—there’s at least one “letter scene.” Sometimes two. These are scenes where we watch someone write a letter, and what is written, as well as what the character imagines writing, becomes an important part of the story. Letters fascinate me for a number of reasons, though chiefly because we tend not to write them anymore. But imagine a world where people only really spoke through letters, since in society you were carefully monitored, especially as a woman, with family members forever watching you, making sure you were doing your duty and never going too far. To speak your mind to someone you cared for could only be done in a letter, and even then, it had to be done carefully, meticulously. And once delivered, the letter was a precious object, a one-of-a-kind artistic creation that only one other person in the world possessed.

Imagine how different that is today, when even e-mails are never private. We never possess the actual first draft of someone’s thoughts. Being able to see someone’s handwriting and imagine the pressure they placed on a specific word or letter speaks as loudly as the letter itself. In short, to write a letter was to escape from the strictures of society and speak unfettered, truly naked before one other person, be it a friend, a lover, a parent, or a child. You could act, you could quibble, you could even lie in a letter...but it was so much easier for the reader to see the truth.

Since I write fantasy set hundreds of years ago in an alternative past, letter writing is how my characters see the world. In many of the great novels of the past, letters frame an important moment for the characters—think of Elizabeth Bennet’s letter from Darcy in Pride and Prejudice or more humorously, the letter delivered to Malvolio in Twelfth Night. We love these meta moments in fiction, allowing us to read a character in the act of reading, or even better, envision a writer writing about a character themselves trying to put words on a page. As writers, many of us enjoy this, too, since it reflects our own frustrations and doubts about writing. We want to see our own creations struggle with the same problems we do, since they are, in a sense, versions of us. We want to see them cross out words, not find the right words, or not be able to write at all. Perhaps we merely want our characters to suffer the same hell they put us through?

Or should I say, I want to see this, since my books are fundamentally pieces of my own autobiography. So often when I’m writing, there are two kinds of passages: (a) passages that move the story along in some fundamental way and (b) passages that allow me to look at myself in a mirror. The letter scenes are exactly that, and I dash them off like nobody’s business. No Writer’s Block here, just sheer fun and inspiration. The “a” passages are much harder to write and I tirelessly revise them, often losing inspiration in the process. Of course, this begs the question: if the “b” passages are more autobiographical and so much easier to write, are they really all that good? Are you merely indulging in some shameless diary entries or budget psychoanalysis? After all, everyone has an equivalent to my “letter scenes” where they get to indulge in subject matter that is the verbal equivalent of a warm bath. You sink into the words and lose yourself in a bliss of self reflection/satisfaction.

I would argue that every novel (or any kind of writing) needs both passages, “a” and “b.” Maybe a little more of “a,” but the “b’s” make the story. Because a story without your unique stamp as a writer and thinker is no story at all. You have to play to your strengths as a writer and know what motivates you and allows you to get inside the mind of your character(s). The powers-that-be always say, “write what you know,” but that doesn’t necessarily mean “write about someone like you in a place like the one you live in,” etc. It means write about the things that make you excited about the world around you; those things that make you understand your fellow man and woman; the ideas that make character seem alive rather than cardboard cut-outs or convenient tropes. For that reason, a letter scene in my novels helps me ground my characters and truly talk to one another—and quite often, discover what they really want and who they truly are.

In my novel, The Winged Turban, the main character is trapped in an earlier time and appears there as the spitting-image of another character’s lost love. Clearly, she is not this woman, and yet everyone is convinced that she is, to the point that she begins questioning who she is, too—all the more so, that she begins remembering shards of the centuries-deceased woman’s life. She eventually allows herself to believe that she could, possibly, have a life with Charles, but only if such a life is based on the truth; he has to know who she is, or was, if they can ever mean anything together. How could she tell him this? Through a simple conversation? A series of them? Or...a letter?

The Crystal Ball by Waterhouse, 1902.

I caught myself here, since I knew I was falling back on my old bag of tricks. And yet, this is what made the story exciting for me: that a woman who was falling in love had to convince herself, and the man she loved, that they weren’t fooling each other. That they could actually see one another for who they were, rather than what they might have been. The story became much more personal for me at this moment, since I understood what she wanted and why she couldn’t let herself have it. So I wrote a letter, probably the letter I, myself, would have written in her shoes. But I did it in her voice, and the result is pasted below, and I continue to think it one of the more successful parts of the novel:

[From Chapter 32]

Beatrice slumped against the wall, feeling trapped in more ways than one. In her mind she had already written most of the letter; the question would be which parts to leave out.

Dear Charles,

You once dropped a glove to catch my heart. You caught it: I gave you everything a young girl could give, all her dreams and secrets. I think this letter is my own glove, what I fear to give voice to and can only place in a letter. Read this before you see me again, and if your feelings still hold, then I will try to accept myself as Isabella, though I fear I can never be what she was for you.

Here is the truth: I am a married woman from another land. Married by contract, of course, but married nonetheless. I am the Duchess of a great estate, of a great family. Though the match was never consummated, it is only a matter of time, and I must do my duty. Should I return, I would have to be his wife, the wife of a man I’ve only met once and can scarcely recall in my head. I would have to forget everything I am and hope to be, and of course everything I’ve seen and experienced with you.

But what if I didn’t return? What if I stayed here and forgot who I was and who I married? Would you accept me? Would you hide me? Would you help me forget? Of course you could never forget, and by coming here I am breaking my vows, shaming my family and offending the gods. I would never be accepted in the world to come. But I would risk that, if only to be here with you. Even if I only lasted a year, that year would be worth an eternity of whatever followed. Because I could remember that once upon a time someone loved me and claimed me for his own. I would do this. But I can’t ask this of you.

And yet I am asking you. I don’t dare ask it to your face, so I write it here, for you to find when I am gone. I hope you will pick it up, but if not, you’ve already given me a glimpse at a beautiful life, one I will carry with me forever, whether I’m Beatrice or Isabella. I await your answer...

Beatrice shuddered at the thought of writing it all down. No, she could never do it. He would never agree.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Friday Reads: ART EXHIBIT

“If I create from the heart, nearly everything works; if from the head, almost nothing.” - Marc Chagall

Art is everywhere! And this season of exhibitions in museums across the country features artists about whom we’ve published gorgeous books. They make wonderful gifts for the art lover on your list, but will transport any reader into the life and heart of the artist.

CHAGALL by Jonathan Wilson

Novelist and critic Jonathan Wilson clears away the sentimental mists surrounding an artist whose career spanned two world wars, the Russian Revolution, the Holocaust, and the birth of the State of Israel. Marc Chagall’s work addresses these transforming events, but his ambivalence about his role as a Jewish artist adds an intriguing wrinkle to common assumptions about his life. Drawn to sacred subject matter, Chagall remains defiantly secular in outlook; determined to “narrate” the miraculous and tragic events of the Jewish past, he frequently chooses Jesus as a symbol of martyrdom and sacrifice.

CARAVAGGIO by Stefano Zuffi

This generously illustrated volume on the work of Caravaggio makes the world’s greatest art accessible to readers of every level of appreciation. This monograph explores Caravaggio’s entire life and career by focusing on the most important of his works. Readers will learn about his innovated use of light and shadow, his physical and psychological realism, and his radical technique of omitting initial drawings and creating straight onto the canvas.

DAVID HOCKNEY: A BIGGER EXHIBITION by Richard Benefield, David Hockney, Sarah Howgate and Lawrence Weschler

Now available in a new edition, this lavishly illustrated book captures the grand scale and vibrant color of David Hockney’s work of the 21st century. In the past decade, having returned to England after years on the California coast, David Hockney has focused his attention on landscapes and portraits, as well as still lifes, all the while maintaining his fascination with digital technology. The resulting work is an extravagance of color and light, ranging in dimension from billboard- to letter-size.

EDVARD MUNCH by Elizabeth Prelinger and Andrew Robinson

Edvard Munch’s images of love, alienation, jealousy, and death – universal human experiences but filtered through events in his own life – are explored in this publication which brings together nearly sixty of Munch’s most important prints, from the National Gallery of Art and two exceptional private collections, demonstrating how the artist’s experimental impulses over the course of his lifetime endowed his haunting motifs with new meanings.

AUGUSTE RODIN by Rainer Maria Rilke

Sculptor Auguste Rodin was fortunate to have as his secretary Rainer Maria Rilke, one of the most sensitive poets of our time. These two pieces discussing Rodin’s work and development as an artist are as revealing of Rilke as they are of his subject. Written in 1902 and 1907, these essays mark the entry of the poet into the world of letters. Rilke’s description of Rodin reveals the profound psychic connection between the two great artists, both masters of giving visible life to the invisible.

LOUISE BOURGEOIS by Daniel Tilkin

A stunning selection of late and unseen works by Louise Bourgeois analyzed from philosophical, critical and artistic points of view. Aim of the project is to show the last ten years of Louise Bourgeois’ work, her private and continue interest in Freud and how she reflected it in her art and diaries.

For more information on these and related titles visit Art Exhibits

#auguste rodin#marc chagall#louise bourgeois#caravaggio#penguin random house#friday reads#artexhibits#there's a book for that#skira#archipelago#rizzoli#prestel#david hockney#edvardmunch

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction to Bacon & the Art of Living

The quest to understand how great bacon is made takes me around the world and through epic adventures. I tell the story by changing the setting from the 2000s to the late 1800s when much of the technology behind bacon curing was unraveled. I weave into the mix beautiful stories of Cape Town and use mostly my family as the other characters besides me and Oscar and Uncle Jeppe from Denmark, a good friend and someone to whom I owe much gratitude! A man who knows bacon! Most other characters have a real basis in history and I describe actual events and personal experiences set in a different historical context.

The cast I use to mould the story into is letters I wrote home during my travels.

The Castlemain Bacon Company

October 1960

Over the years I have written letters to my kids telling them what I learn and about my experiences. They followed my quest to produce the best bacon on earth through these monthly communications. When I returned home I found that they kept every letter. When they were here last December, the gave me the draft of a book where they are including every letter. They even contacted Dawie and Oscar who both sent them my mails. They asked me to write the introduction to every county and the “Union Letters” as they called the letters I sent them from Cape Town.

I asked them if I can add three accounts of companies who achieved perfection in the large-scale production of bacon. This is the first of the three good examples of people who achieved what I sought. I think that for a time at Woody’s we achieved the same and when Duncan and Koos took over, things took a dip, but they are recovering beautifully.

What makes this an insanely exciting story is the fact that the main character who created the Castlemaine Bacon Company fought in the Second Anglo-Boer war on the side of Brittain. My great grandfather fought in the same war, but for the Boers. It was a fascinating project for me to compare diaries and see what our, now two, main characters did at certain times. The two men are Wright Harris and Jan Kok, my great-grandfather.

These stories begin much in the same way. Their faith played an equally important role in surviving the war and it established a legacy where hard work, faith, and opportunity determined the actions of their children’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Both stories end with the creation of a bacon curing company!

The Anglo-Boer War

The Second Boer War (11 October 1899 – 31 May 1902) was fought between the British Empire and two Boer states. One was the South African Republic (Republic of Transvaal) and the other was the Orange Free State. The war was fought over England’s influence in South Africa. It is called the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War.

As it happens, we know the man in England who was in charge of the military when the war broke out. It is none other than Lord Landsdown from Wiltshire, the man we dined with on the evening before Minette and I left for New Zealand via Cape Town who was the Secretary of State for War when the Second Anglo-Boer war broke out.

For the life of me, I can’t remember who said this, but a bacon production manager in the UK quoted an English author who described the Boers as “stinking smelly bastards but they can shoot straight!” Such is the Boer soldier!

England approached its other colonies to recruit soldiers to fight in South Africa. One such a man, from Australia, was Wright Harris.

WRIGHT HARRIS

Wright Harris before departure for the Boer War, 1900

The story of Wright Harris, the Australian protagonist, begins in England where his parents were married in January 1864 and migrated to Victoria, Australia. Wright was the 7th of 11 children. His father was a farm labourer and woodcutter. Wright remarked in later life that he left school at age 12 when hard work was the lot of most boys and added that “it didn’t hurt us.” Wright was a devout Christian. A heritage he got from his mother. By 1900 he was a regular lay preacher at many churches in the area.

JAN KOK

Our second protagonist is my great grandfather, Jan Kok.

Jan Kok at the house on Kranskop where he was born.

Johannes W Kok was born in Winburg in the independent Boer republic of the Orange Free State on 4 April 1880. The Orange Free State got its independence from Brittain on 23 February 1854. Winburg itself was a self-proclaimed independent Boer territory since 1837 and was incorporated into the Free State in 1854. Jan Kok was christened in Winburg on 02 Mei 1880. He grew up right in the heart of Boer-self determination.

THE SECOND ANGLO-BOER WAR

In October 1899 the second Anglo-Boer war broke out in South Africa. In the first few months, the Boers had the upper hand, but the British government responded by massing its forces from across the empire. Wright enlisted in February 1900 in the Victorian Bushmen Contingent.

Jack Harris in the Otto Würth smokehouse, 1993

P. L. Murray writes about the Third Bushmen Contingent in his work, Official Records of the Australian military contingents to the war in South Africa, “This corps was largely subscribed for by the public. It was resolved that, in lieu of drawing the men exclusively from the local forces, a class of Australian yeomen and bushmen should be obtained; hardy riders straight shots, accustomed to find their way about in difficult country, and likely to make an expert figure in the vicissitudes of such a campaign as was being conducted.”

An enormous number of candidates volunteered for enlistment. The men selected were largely untrained in military matters; 230 were farmers or with some connection to farming. The selection criteria were based on their ability to ride and shoot. The men were allowed to bring their own horses. Many brought two.

They left Melbourne for South Africa on 10 March 1900 aboard the Euryalis and arrived in Cape Town on 3 April 1900. Wright suffered from severe seasickness on the voyage to South Africa and wrote only two words in his diary, “seasick.” Of the 261 men and NCO’s and 15 officers, 17 would lose their lives in the South African campaign.”

In South-Africa, thirty-seven days later, on 5 May 1900, on an autumn evening, the 20-year-old Jan Kok greeted his mum and dad, took his rifle and mounted his horse. At 20:00 he rode off with the kommando (1) from their farm Kransdrif. From there they rode to the farm of A. Nel, Kafferskop. In all, they were 11 people riding together; 6 from Winburg, 1 from Kroonstad, 2 from Thabanchu and two black people. They travel to Ficksburg, where they join the Kommando and on 18 May they set off from Ficksburg to join larger Boer forces.

I read an account about Boers getting the call to war from a story, published in American newspapers in May 1900. The events surrounding the call to arms and the mood when Jan rode off to war could not have been much different. “All night the beacon fires had been burning on the higher kops. All night native runners had been scouring the country with messages from the commandants to the burgers. All night in many farmhouses the woman had been at work preparing the rations of biltong, and cleaning the arms of the patriots. All night throughout the length and breadth of the land prayers had gone up and the veld had echoed deep-voiced songs of David.” (The Philadelphia Inquirer, 1900)

From Jan’s diary, there was considerable disagreement where they should go and which Boer forces they should join.

The Australians, on the other hand, had none of the indecisiveness associated with a more informal military organisation of the Boers. As soon as they landed at Cape Town, they traveled to Beira and to Marondera (known as Marandellas until 1982), a town in Mashonaland East, Zimbabwe, located about 72 km east of Harare. Here, all the colonial Bushmen were formed into regiments known as the Rhodesian Field Force; “the Victorians and West Australians forming the 3rd, under Major Vialls. They marched in squadrons across the then Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) to Bulawayo. From there to Mafikeng where they were again mobilised and equipped and took part in one of the major battles of the war, the siege of Mafikeng.

Wright noted the following entries in his journal at Mafikeng. 23 July, Monday. “Left Bulawayo for Mafikeng at 3 o’clock. Twenty-five in a truck, packed in like pigs.”

24 July, Tuesday. “Ostrich running alongside the train. A halt for two hours at Palepwe to feed and water horses.” (I am not sure where Palepwe is. The name is probably misspelled)

25 July, Wednesday “Met by an armoured train. Reached Mafikeng at about 6 o’clock, and slept out in the rain.”

26 July, Thursday. “A look around the trenches and around Mafikeng. Saw the Boer prisoners, two sentenced to death.”

27 July, Friday. “Got our saddles. The ponies captured from the Boers allotted to us. Saw the guns that saved Mafikeng.”

28 July, Saturday. “Sent out to hold the river against the enemy with four guns. Got orders to go away and take three months provisions. Order countermanded (rescinded/canceled).”

29 July, Sunday. “Church parade. Went to the Wesleyan church in town, had a grand service. Text Timoty 21 and 22. On picket, got a piece of shell that had come through the roof. (This must be a mistake because there is no such reference. My best guess is that it is 2 Tim 2: 21 and 22 which reads: “If a man, therefore, purges himself from these, he shall be a vessel unto honour, sanctified, and meet for the master’s use, and prepared unto every good work. Flee also youthful lusts: but follow righteousness, faith, charity, peace, with them that call on the Lord out of a pure heart.”

On 28 July, Jan notes in his own diary that the kommando, under the leadership of General Marthinus Prinsloo, decides that it is not worth fighting any further since the Boers are heavily demoralised. They ask the British to negotiate a surrender. At this time they are still in Fouriesburg, in the Brandwater Basin.

The formal surrender was on 30 July 1900, but Jan and his fellow Boers lay down arms on 31 July. They are assured by the British that they would be allowed to return to their homes and farms, but in the end, this does not materialise.

Photo courtesy of Dirk Marais. Boers surrendering at the Brandwaterkom (4)

Jan writes in his diary on Monday, 31 July 1900, “we have our weapons deposited on the surrender of General Prinsloo to General Hunter. On this day he notes, “a time of new experiences and disappointment, for sure.” On August 11 they sent us by train to Cape Town (Green Point).” He writes that “the Malaaihers (Malays?) and bastards (colourds?) were standing both sides of the street and mocked us all the way.”

They board the ship Dilwara on 15 August. On 18 August they leave Cape Town and stopover in Simonsbaai (probably Simons Town). On 21 August they arrived in Durban. Aboard they are tortured by an infestation of fleas. They leave Durban on 22 August. On 30 August, they anchor at the “Chysellen.” Here they are allowed for the first time to buy some fruit, “12 bananas for 6 “pence.”

On 8 September they arrive in Colombo Bay. From here they travel 160 miles by train and arrive eventually in Diyatalawa.

On 16 September a fellow inmate and an ordained minister, Ds C Ferreira, preach from Matt. 8:12, “But the children of the kingdom shall be cast out into outer darkness: there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth” That afternoon Ds Postma preach from Luke 18:10 (probably up to: 14). On that day they were very upset that the “koelies” (a derogatory but common term for people of Indian descent) worked on that day, a Sunday as if it was any other day. Ds. Postma’s reading dealt with that judgemental attitude towards others who do not observe and worship in the same way as you do.

He writes on 22 September that he and Gert van de Venter from hut 48 started a “Zingkoor” (a choir). He attended bible study at hut 63 where a certain Ds. Roux spoke.

Photo courtesy of Nico Moolman. A Boer POW in Ceylon (Shri Lanka).

This was obviously a time of great reflection and soul searching. On 1 October, he writes that “as I reflect on the past year and what happened to me, I can not say anything else but that the Lord helped me through it all and that he can not but to thank Him for all that He has done for me.” It is interesting that he named his son, years later, Ebenhaezer, meaning” God helped me all the way and brought me to this place.” He never told my grandfather why he named him Eben. It was not a family name and must have been done deliberately in a time when conservative farmers gave their children the names of their parents or grandparents. From this entry in his diary, I can see how important this thought was to him and, especially in Afrikaans, the wording is similar to the words used in the bible from where we get the meaning of the name, Ebenhaezer. I suspect that in naming his son Eben, Jan was celebrating God’s faithfulness in by allowing him to return and have his own family.

There were also ministers in the camp who used Sunday school for a time to criticise the fact that they laid down arms. Ds. Roux accused them of being selfish when they surrendered and say that they were only feeling sorry for their horses and were homesick.

He spends lots of time attending bible study and Sunday school. On 3 January when a school was started, he attended. On 7 January he mentions that there was a missions prayer meeting and he starts to attend a missions class.

Boer prisoners of war at the Sunday service in Diyatalawa camp on Ceylon. Post and photo by Dirk Marais

His grandson, Ds Jan Kok (my uncle), writes a dissertation when he completes his studies as a Dutch Reformed minister, about the development of a missionary zeal in the POW camps and indeed, many of the POW’s returned home to become missionaries. This was later published under the title “Sonderlinge Vrug” (special or unusual fruit).

Jan became one of the founders of the “Zuid-Afrikaansche Pennie Vereniging” on 1 June 1902. The goal of the organisation was to promote the missionary course and through this, to expand the Kingdom of God.

On 31 July, as Jan surrenders and is taken POW, Wright Harris is still very much part of the siege of Mafikeng and writes in his own diary, “Called out to wait for the Boers at daylight. Ordered not to start.” 1 August, Wright notes, “Starting out for Mafikeng. Passed Boer trenches.”

He survives the campaign, but his health deteriorates. He suffers horrible bouts of severe illness. His Christian faith sustains him through everything, like Jan Kok in the Diyatalawa camp. Wright also continues to attend church parades, tent meetings, bible readings, and prayer meetings. I wonder if he could have imagined that on the Boer side there were men with much the same commitment and a common experience of faith with him.

In early October, as Jan is getting used to life as a prisoner of war, Wright Harris contracts deadly typhoid fever. He is taken to hospital where he lay for weeks, delirious and close to death. He is so severely sick that he later becomes convinced that his eventual recovery is a miracle. As soon as he was sufficiently recovered, he is sent back to Australia and arrived in Melbourne in early Feb 1901.

Wright, deeply committed to his faith, undertakes a year of church work in New Zealand, following the war. Jan is eventually released on 5 December 1902 and returns to South Africa on 27 December 1902.

FOLLOWING THE WAR

There is a deep belief among the young men at these camps that a reason for the war was that they did not do everything in their power to spread Christianity among the native African tribes. It was in a way, God’s judgment upon them for their inaction. It is therefore not surprising that after their homecoming, Jan enrolls in the Missionary Seminary of the Dutch Reformed Church in Wellington. The collective Boer nations had matters to resolve that, in their interpretation of events, brought about such devastation on their land and it is completely understandable and commendable that this became the passion of Jan’s life. Jan is confirmed in March 1906 in a missions church in Heilbron.

Wright did not have a nation to save and without the spiritual issues that plagued the young Boer-men, focusing on building his own life. He was ready to do whatever his hands find to do. Events in his life would steer him, not to full-time church ministry as was the case with Jan, but to a life of business and bacon curing.

Probably through the Methodist church at Scoresby, he met John and his daughter, Janet Weetman. William Haine ran a butter factory in Kennedy Street, Castlemaine. He also ran a bacon company part-time as the Castlemaine Mild Cured Bacon Company, to earn additional income. Haine and Weetman agreed for John and Janet to take over the running of the bacon side of things and Weetman roped Wright Harris in to assist them. The three arrived in Castlemaine in 1905 and started the Castlemaine Bacon Company in a room in the butter factory. Together with John Kernihan they processed five pigs per week. John Kernihan and John Weetman were the experienced craftsmen. Kernihan employed Weetman years earlier in his own bacon company in Northcote but lost his business during the depression of the 1850s.

Wright and Janet eventually marry on 18 April 1906. John Weetman passed away on 28 March 1922 at which time Wright and Janet acquired the company and the land the factory was built on. So started a long and prolific history of the Castlemaine Bacon Company under Wright Harris’s name.

Back in South Africa, Jan remains faithfully at the congregation in Heilbron for 39 years until his retirement in 1945. My uncle, Oom Jan Kok, who was named after his grandfather, follows in his footsteps and become a pastor in the Dutch Reformed Church. He faithfully serves in the Moedergemeente, Warmbad for most of his life. He tells an interesting story that when he was christened, this was done in the “black church” where his grandfather and the man who’s name he received, was the pastor, in Heilbron. In those years this was of course not permitted under the Apartheid Laws. My uncle, Jan, needed a “doopseël” (baptismal seal) for some reason and it was eventually found at the “white church” (Heilbron-South) where his grandfather must have registered it.

I, in turn, am named after my grandfather, Oupa Eben Kok and was destined to follow in the footsteps of my great granddad and uncle to become a pastor. During a year I spent in the USA after my own time in the South African Army (1988 to 1990), I returned to South Africa with a commitment to pursue a career in business. Bacon curing became my life. (2)

It was in researching an article for this site on famous bacon curing companies from around the world and a book I am writing on our setting up of Woody’s Consumer Brands that I came across the story of the Castlemaine Bacon Company and the link they have with South Africa. Since the founding of the company, our growth has been meteoric, much like Wright Harris’ Castlemaine Bacon Company. The Harris family now stands and looks back at a company which they eventually sold and they have in a sense completed the full circle, a road that we are still excited to be traveling and in a sense, continue to follow in their footsteps.

Finally

The great story of bacon curing is, from the beginning to the end, a human story. It took the best of humankind, over thousands of years to create a dish that mimics natural processes that are part of human metabolism, every moment. The story of bacon curing is our own story in a very personal way. It is a science and an art – human culture at its best. Telling the story of curing is telling our own personal stories. They are inseparable.

On Saturday morning I was standing in our own dispatch area, telling Oscar about this article and my attempts to make contact with the Harris family. The commitments, disciplines and great lessons from the words of John Harris and the inspiration we can draw from them.

As humans, we identify patterns, we learn, evolve and we connect. Looking at our own experience in Woody’s Consumer Brands fill Oscar and me with a deep gratitude and we take courage from the men and woman of the Harris family with their remarkable heritage which is so close to our own. Bacon curing brings together some of the greatest stories on earth!

Graham Tonkin with sausages.

(c) Eben van Tonder

Further Reading

Lord Lansdowne at the War Office (1895-1900)

(c) eben van tonder

“Bacon & the art of living” in book form

Stay in touch

Like our Facebook page and see the next post. Like, share, comment, contribute!

Bacon and the art of living

Promote your Page too

Note

(1) The Age, Melbourn, Victoria, Australia, 29 November 1899 reported in an article entitled “How the Boers Go to War”, The Boer process of going to war is simple enough. They have no clothes to change, no uniform to don. They fill their bandolier, or cartridge belt, put a piece of biltong in their pocket, mount their horse and ride off. Nothing could be more simple. Biltong, it should be explained, is sun-dried version, shredded into strips and wonderfully nourishing and sustaining. The Boers when out in the field, live on it for weeks at a time, and apparently thrive thereon. . . Everything is left to chance, and it is truly wonderful how they manage to escape all manner of horrible dangers. If they get wounded they hie them to the nearest farmhouse, where they are tended until they are well. If they get shot, – well, it is the will of God – their friends bury them and it is all over.

Practically every Boer is mounted, and although they have no regular constituted regiments, or, indeed any formal battle formation, they join together in what are called “commandos.” These are the aggregate collection of farmers and their sons from one particular district of the Transvaal, gathered together in a more or less heterogeneous mass, and under the nominal leadership of the veld cornet or the commandant of that particular district.” (The Age, 1899)

(2) I fell in love with Chemistry and in my mid 30’s decided to enter the world of food manufacturing. In 2008, Oscar Klynveld and I created Woody’s Consumer Brands (Pty) Ltd. with the ambitious goal of selling the best bacon on earth. Oscar himself is the son of a Dutch Reformed minister with deep religious convictions. I always loved writing and storytelling and when I discovered that the field of meat science is replete with amazing untold stories, I start a blog where I feature some of these amazing stories.

(3) Afrikaans: Boere-krygsgevangenes by die sondagdiens in Diyatalawa-kamp op Ceylon.

Hierdie gevangenes was hoofsaaklik van die Brandwaterkom, Oranje-Vrijstaat, onder genl. Prinsloo afkomstig. Marthinus Prinsloo se oorgawe in die Brandwaterkom was ‘n vername terugslag vir die Boeresaak in die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog. Op 12 Januarie 1901 het sowat 630 krygsgevangenes met die Catalonia uit Kaapstad gearriveer, benewens die sowat 5 000 wat reeds in Ceylon was.

Genl. Jan Hendrik Olivier staan byna regs, middel, en di. Petrus Postma (met bybel, en aldaar bekend as “the fighting parson”) van Pretoria en Paul Hendrik Roux van Senekal staan sy aan sy in die middel van die foto. Eerw. Roux van Bethlehem en di. George Murray van Oudtshoorn, Dirk Jacobus Minnaar van Heilbron en George Thom van Frankfort sou ook in hierdie kamp onder dieselde omstandighede as ander gevangenes bly.

English: Boer prisoners of war at the Sunday service in Diyatalawa camp on Ceylon, who were mostly taken captive at the Brandwater basin, Orange Free State, under general Prinsloo. Prinsloo’s surrender was a major setback for the Boer cause during the war. Reverends Petrus Postma from Pretoria and Paul Hendrik Roux from Senekal stand side by side just right of center, and general J.H. Olivier is visible at middle, right. One caption to the photo was as follows:

The Boer Prisoners at Service in Ceylon. The prisoners are guarded by the King’s Royal Rifles, under Colonel Gore-Brown, Colonel Vincent being Commandant, and Colonel Jesse Coope in immediate charge of them. Temporary hospital huts have been erected and brightened with pictures and illustrated papers, and officials of the local branch of the Bible Society have distributed Bibles and portions of the Scriptures in Dutch. These were welcomed and specially acknowledged by a letter of thanks by a prisoner known as “the fighting parson [Petrus Postma].” Colonel Jesse Coope, who is very popular, fosters productive manufactures and artistic activity among the men, disposing of their work through an agent. Tanks for the storage of water being required, the prisoners were invited to volunteer for the work at a reasonable rate of pay, and many availed themselves of the offer. The population of Ceylon does not exceed 6,000 [Europeans?], and the settlement of the Boer prisoners has had a wholesome effect, not only on themselves but on the Cingalese. The minister who is officiating (in the above photograph), is the “fighting parson” alluded to – the Rev. Mr. Postma – and General Roux stands beside him. Olivier can be identified nearer to the right margin of the picture and several rows further back.

Source: Post and photo by Dirk Marais

(4) SLAG VAN SURRENDER HILL

OP 30 Julie 1900 het 4 314 Boere op Oorgaweheuwel (Surrender Hill) op die plaas Verliesfontein naby die huidige Clarens hul wapens neergelê. Die Britte het ook 3 veldkanonne, 2 800 beeste, 4 000 skape, 5 500 perde en 2 miljoen patrone in die Brandwaterkom gebuit. Dit was ‘n geweldige terugslag vir die stryd teen die Britte.

LORD ROBERTS, opperbevelhebber van die Britse mag in Suid-Afrika, was met sy vertrek in Mei 1900 uit die Vrystaat nie baie bekommerd oor die Vrystaatse mag onder aanvoering van genl. C.R. de Wet nie. Hy het geglo sy mag sou die Vrystaters in bedwang hou.

Einde Mei en begin Junie gebeur egter ‘n paar dinge in die veld wat sy houding drasties laat verander. Op 31 Mei verslaan die Vrystaatse mag die Yeomanry naby Lindley. Twee dae later by Swawelkrans, buit De Wet 56 waens wat vir die Engelse in Heilbron bestem was. Op 7 Junie behaal De Wet ‘n verdere oorwinning oor die Engelse by Roodewal. Dié nederlae het Roberts laat besef dat hy ‘n fout gemaak het om die Vrystaters te onderskat. Op 14 Junie gee hy uit Pretoria aan sy bevelvoerders opdrag om De Wet teen die berge in die Oos-Vrystaat vas te druk en te vang. Hy het gehoop, maar nooit gedink dat hy binne twee maande amper die helfte van die Vrystaatse mag sou kon vang nie.

Genl. R. Buller moes in Standerton keer dat die Boere noord vlug. Lt.genl. sir L. Rundle, wat ‘n sterk verdedigingslyn tussen Winburg, Senekal en Ficksburg beman het, het die suide geblokkeer. Genls. R.A.P. Clements en A.H. Pagel het die Boere van Lindley af oos in die rigting van Bethlehem aangeja.

Lt.genl. sir A. Hunter, wat in bevel was van die dryfjag op die Boere, het van Transvaal via Frankfort en Reitz in die rigting van Bethlehem opgeruk.

Ná die Slag van Bethlehem op 6 en 7 Julie 1900 het De Wet en die Vrystaters dus eintlik geen keuse gehad as om suid in die rigting van Fouriesburg en die Brandwaterkom te trek nie.

Op 8 Julie 1900 bevind die hele Vrystaatse mag, behalwe hoofkmdt. F.J.W. Hattingh met die Vrede- en Harrismith-kommando wat die bergpasse oppas, hulle in die Brandwaterkom. Ook pres. M.T. Steyn en lede van die Vrystaatse regering was hier.

(c) Dirk Marais

(5) A few photos from my visit to Castlemain

Reference

I liberally quote and use information from Bringing home the bacon: a history of the Harris family’s Castlemaine Bacon Company 1905-2005 / Leigh Edmonds. Monash University. The photo of Wright Harris, this source.

Murray, P. L.. 1911. Official Records of the Australian military contingents to the war in South Africa. Albert J. Mullett, Government Printers.

The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 6 May 1900, page 3

The Age, Melbourn, Victoria, Australia, 29 November 1899, page 5.

All information and photos of JW Kok supplied by Jan Kok in private correspondence.

Photos of the Harris family and Castelmain Bacon Factory from Leigh Edmonds, 2005, Bringing Home the Bacon, Monash University.

Chapter 12.01: The Castlemaine Bacon Company Introduction to Bacon & the Art of Living The quest to understand how great bacon is made takes me around the world and through epic adventures.

0 notes

Text

A Brief History of Mystery Books

What exactly is a mystery book?

In a mystery novel, a crime is committed. The crime is commonly a murder, but thefts or kidnappings are also popular. The action of the story revolves around the solution of that crime – determining who did it and why, and ideally achieving some form of justice.

There are many specific subtypes within the mystery genre: police procedurals, hard-boiled detective stories, espionage thrillers, medical or forensic mysteries, cozy mysteries, closed-room mysteries, and courtroom dramas, to name a few. As myriad as they sound, they all sprouted from the same authors and history.

This copy of The Murders in the Rue Morgue is a 1932 “photoplay edition” listed for sale by Heritage Book Shop.

The beginning of the mystery genre

The rapid growth of urban centers in the 19th century meant that more police were needed. This spurred the advent of professional detectives whose chief job was to investigate crimes. Although there are examples of puzzle stories that reach back through time to when some of the earliest poems or tales were written down, most people agree that the first modern ‘detective story’ is The Murders in the Rue Morgue by Edgar Allan Poe. First published in the April 1841 issue of Graham’s Magazine, the short story tells the tale of an amateur detective who sets out to solve the grisly murders of a mother and daughter within a locked room of their apartment on the Rue Morgue.

Nearly twenty years after Poe’s story, Wilkie Collins published The Woman in White (1859), which is considered the first mystery novel, and The Moonstone (1868), generally considered the first detective novel. The Woman in White is a gripping tale of murder, madness and mistaken identity that is so beloved it has never been out of print. Collins had “Author of The Woman in White and other works of fiction” engraved on his tombstone. The Moonstone set the standards for the detective novel formula – an enormous diamond is stolen from a Hindu temple and resurfaces at a birthday party in an English manor, and with numerous narrators and suspects, the story weaves through superstitions, romance, humor and suspicion to solve the puzzle.

The Moonstone’s title as the first detective novel is contested by two other books. The first, The Notting Hill Mystery, was published in 1865 and written under the pen name Charles Felix, who is believed to be Charles Warren Adams, sole proprietor of the publishing house Saunders, Otley, and Company. In The Notting Hill Mystery, the main character figures out the culprit of murder through diary entries, family letters, chemical analysis, depositions, and a crime scene map. Many of these detective techniques were not used again until the novels of the 1920s.

A French mystery, L’Affaire Lerouge (1866) by Émile Gaboriau, is also considered a pioneering detective novel. One of the first stories to use the gathering of evidence to solve the murder mystery, it combines police intrigue and a love story – two mothers, two sons, and one father (a Count). L’Affaire Lerouge, first published in English as The Widow Lerouge or The Lerouge Case, introduced the concept of an amateur detective as well as a recurring character trope, featuring a young police officer named Monsieur Lecoq who was featured in several of Gaboriau’s later novels.

This first American edition of The Leavenworth Case: A Lawyer’s Story is listed by Lucius Books

Early Mystery Novels

The Dead Letter, published in 1866 by Beadle’s Monthly Magazine, is credited with being the first detective story by a woman. It was written under the name Seeley Regester, a nom de plume for author Metta Victoria Fuller Victor who wrote more than 100 dime novels. The Dead Letter is also the first full-length American work of crime fiction.

In 1878, Anna Katherine Green introduced the first American detective in The Leavenworth Case. The Leavenworth Case is widely noted as one of the first American bestsellers, selling 750,000 copies in its first decade and a half of publication. Green would pave the way for many prolific and talented women writers in the genre.

But unlike The Leavenworth Case that eventually fell out of favor and out of print, Robert Louis Stevenson, who had success with Treasure Island in 1883, published the classic mystery The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1886. Initially sold as a ‘penny dreadful’ in the UK and US, more than 40,000 copies of the book had been sold within six months, and soon after more than 250,000 copies were pirated in America. The book and its characters have infiltrated not only literature but also film, television, and popular culture ever since.

The first edition of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde listed by Second Story Books

1886 was also the year The Mystery of a Handsom Cab was published in Australia, written by Fergus Hume. The mystery about a body discovered in a Handsom cab in the city of Melbourne was very successful in Australia, and it went on to be published in America and Britain, selling over 500,000 copies worldwide. The Mystery of a Handsom Cab initially outsold a new release by Arthur Conan Doyle, one that introduced a character that would soon take over the world of detective fiction.

In 1887, Arthur Conan Doyle sold the rights to a story called A Study in Scarlet for £25. It was published first in Beeton’s Christmas Annual, and later in 1888 as a novel by Ward, Lock & Co. Doyle was 27 years old when it was published and wrote the story in a reported three weeks. A Study in Scarlet was the first work to feature Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. Doyle went on to write 56 short stories featuring Holmes and a total of four full-length novels in what is considered the Canon of Sherlock Holmes. The novels in the Canon following A Study in Scarlet are The Sign of Four (1890), The Hound of the Baskervilles (1901-1902) and The Valley of Fear (1914-1915).

This copy of A Study in Scarlet belonged to John Keynes. Listed by John Atkinson.

Mary Roberts Rinehart published The Circular Staircase in 1908, creating the ‘had I but known’ school of mystery writing. The Circular Staircase, about a spinster aunt who solves mysteries at a rented summer house, became a best-seller and made Rinehart a household name. She wrote hundreds of stories and forty novels. At her death, her novels had sold 10 million copies, and it is said at her prime she sold more books than Agatha Christie, to whom she’s often compared, although many of her works pre-date Christie’s.

The Innocence of Father Brown (1911), a collection of 12 stories, started the prolific career of G. K. Chesterton, who is credited with being the father of the ‘cozy’ mystery. Father Brown solved crimes more by intuition and a deep understanding of human nature than by experimentation and scientific deduction.

1915’s The Thirty-Nine Steps by John Buchan is one of the earliest ‘man-on-the-run thrillers that would later be a popular plot device for mysteries and often used in movies as well. In the novel, Richard Hannay, an expatriate Scot, is an ordinary man met by extraordinary circumstances, who puts his own safety and interests aside to protect his country at the outset of WWI. The novel was very popular with troops during the First World War, and the author followed it up with multiple sequels.

And into the Golden Age…

These books all led up to what is considered ‘The Golden Age’ of crime writing in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of the most beloved authors of this period were British and writing in either the ‘cozy’ or ‘country house’ mystery style. Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Margery Allingham, and Ngaio Marsh are often dubbed the Queens of this Golden Age. Quite a few American writers followed suit until some broke out in a distinct ‘hard-boiled’ style as “pulp” novels were popularized.

The popularity of detective fiction waned with the outbreak of WWII, never again reaching the peak of the Golden Age, yet many mystery books continue to be published and consumed in the subsequent decades.

We’ll be taking a look at the most collectible mystery novels in our Book Collecting By the Year series starting on January 30. Want to get updates in your inbox when we add a new decade? Join our mailing list here.

The post A Brief History of Mystery Books appeared first on Bibliology.

source https://www.biblio.com/blog/2020/01/a-brief-history-of-mystery-books/

1 note

·

View note

Text

1902

Letter excerpt from Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna to Princess Marie of Romania

Nice, 1 February 1902

To our intense regret, Ernie has suddenly expressed the wish of seeing his daughter now, as he felt so lonely. I think, it must have been put into his head by his sisters. Ducky could not refuse it, so has to let her go to Darmstadt for a few weeks. It is deplorable, I cannot say otherwise, as the little one was admirably settled at her lessons and getting into good ways. Besides she is like a little ray of sun in our existence. And then they will turn her head there now and make and endless fuss and amuse her in every way, so as to make her feel the difference of the very simple life here. Also Wilson (Elisabeth's nanny) is simply blown up with importance now! Well, well, it could not be helped this time, but later on she only must go to Darmstadt during her holidays, Ducky has every right to settle it, after the conditions of the divorce.

I cannot say that Ernie's sisters are any longer kind to her: this intensely deplorable story with Kyrill and his endless stay here has completely spoilt and forever, the first good dispositions. I explained it clearly to Ducky, as at first she was inclined to rage about it. But now she has to bear her cross in greater humility and begins to see, how wrong it was to have had this interview with Kyrill here. She lost all her moral advantages. (...) What Ducky wants is a nice, honest, even jolly fellow, with life in him and every manly quality, which she missed so in Ernie and would never find in Kyrill. Ernie had at least bonhomie, Kyrill lacks it completely and is dull besides.

source: My dear Mama by Diana Mandache.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

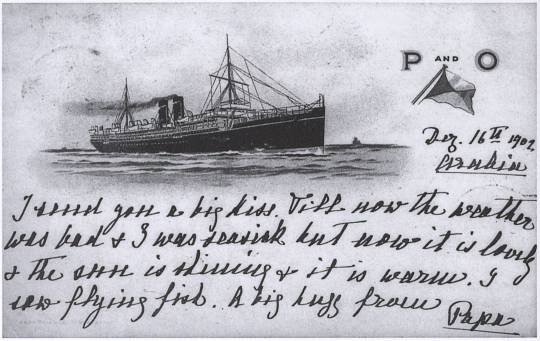

1902-1903 Postcards

In December 1902, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig began his trip to India and Egypt. During his journey, he sent his daughter, Princess Elisabeth of Hesse, numerous postcards, which are preserved in the Hessian State Archives in Darmstadt.

When he departed in December 1902, Ernst Ludwig left his first “Gruss Haus Darmstadt” postcard for his beloved daughter, where he wrote in English: “Goodbye my darling. God bless you. Papa’s love is always near you, sleeping or walking."

On the outward journey, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig sent numerous postcards to Elisabeth, e.g. “tender kisses” from Paris or a picture of his hotel in Marseille with details of his balcony.

On the postcard above, written on board the Arabia on December 16, 1902, Ernst Ludwig told his daughter: "I send you a big kiss. Till now the weather was bad & I was seasick but now it is lovely & the sun is shinning & it is warm. I saw flying fish. A big kiss from Papa.” He celebrated Christmas on board the "Arabia" and Elisabeth sent him and his entourage a Christmas card.

On January 1, 1903, Ernst Ludwig enthusiastically reported to his daughter about his impressions from Delhi: “All those many people dressed in every color of the rainbow. It was lovely. A big kiss from Papa.” The cards are mostly in black and white, but for her daughter to get a better impression, he also described the colours of everything he saw.

On the postcard above, written on January 15, 1903, he wrote: "This lovely place is all in white marble with a blue (sky ?) & lots of green parrots flying about & screaming. They are green with red beak & a red ring round their necks. Papa"

Almost every day he sent his daughter postcards with picturesque pictures and short, sweet greetings. Postcards with motifs that were exotic to Elisabeth document his journey to destinations in northern India that are still classic today, such as Benares, Agra with the Taj Mahal, Jaipur and Fatehpur Sikri.

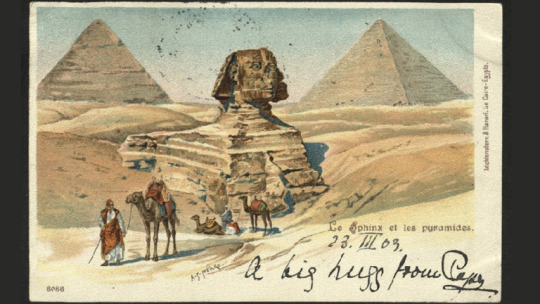

At the end of February, Ernst Ludwig finally began his return journey - but made a stopover in Egypt. On March 5, 1903, on a postcard from the Shephard's Hotel, the most famous luxury hotel in Cairo at that time, Ernst Ludwig announced to his daughter what should not be missed on a trip to Egypt: “Today, I go for a week up the Nile.”

On March 11, 1903, he sent birthday greetings to Elisabeth on a card from Aswan. He also visited Luxor and Karnak and, of course, the pyramids of Giza at the end.

On the postcard above, written on March 22, 1903, he proudly reported to Elisabeth about his climb to the pyramids: "I klimbed (sic.) up the pyramid yesterday & got very out of breath. Today I krept (sic.) into the inside. It was very difficult because all was so very slippery. Papa."

On the postcard above, written on March 23, 1903, Ernst Ludwig sent his daughter "a big hug from Papa".

He finally returned to Darmstadt via Genoa on April 3, 1903.

In the following months, Ernst Ludwig continued to send postcards with loving greetings to Elisabeth from his travels through Germany. In one of his last cards, written on August 6, 1903, he told her: “Next time you must come with me.”

source: landesarchivhessen.de Thank you Thomas Aufleger for sharing this little treasure with me!

#princess Elisabeth of Hesse#Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse#1902 Letters & Diary entries#1902#1903 Letters & Diary entries#1903#1902 Biography#1903 Biography

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

1902

Letter excerpt from Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna to Princess Marie of Romania

Nice, 22 January 1902

Ducky's little girl has very good French lessons; I wish you would begin the same with your children, what is the use of the eternal English and only English? We all have been vaccinated, as there was some small pox about town.

source: My dear Mama by Diana Mandache.

photograph: my collection. Princess Elisabeth of Hesse in 1902. Behind her, a photograph of Princess Marie of Romania with her children, Elisabeth's Romanian cousins.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

1902-1903 Postcards (part II)

In the past few weeks, the Hessischess Staatsarchiv Darmstadt has made public more postcard sent by Ernst Ludwig to his beloved Elisabeth.

On the postcard below, he wrote to his daughter from Grebenhain. "21 September 1902. Such a nice reception here. A big hugg (sic.) Papa."

In December 1902, Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig began his trip to India and Egypt. During his journey, he sent his daughter, Princess Elisabeth, numerous postcards, which are preserved in the Hessian State Archives in Darmstadt.

In his trip, the Grand Duke travelled through Marseille, Port Said, Suez, Aden, Bombay, Delhi, Ducknow, Benares, Agra, Calcutta, Jaipur, Cairo, Aswan, Luxor, Karnak, Philae, Ismailia and Genoa.

His first stop was Marseille, from where he sent his daughter the following postcard: "Dec. 11th. The midle (sic.) balcony is my room. It is warm & sunny here but windy. I only hope it will be goo for tomorrow. (??) go on board. A kiss. Papa."

The Grand Duke started the year 1903 in Delhi (India), from where he sent his daughter the postcard below, with New Year Wishes: "Jan. 1st 1903. All my loving wishes to you darling. Papa."

On the postcard below, he wrote to his daughter from Cairo: "A kiss from Papa".

In Cairo, on his return journey, Ernst Ludwig lodged in the most luxurious hotel in Egypt at the time, the Shepheard's Hotel. From there, he sent his daughter the following postcard:

"5th March 1903. I send you all my love. It is windy & not very warm here. Are you having a happy time? Today I go for a walk up the Nile. A big kiss from Papa."

On the postcard below, Ernst Ludwig wrote to Elisabeth from Lauterbach (Hesse), the last stop in is journey:

"Aug. 5th 1903. This is the Place from where the funny song comes from. All the pictures are put so together that if you look at them sideways they make a stocking. Papa".

source: Hessisches Staatsarchiv Darmstadt. Thank you Thomas for sharing these with me!

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

1902

Letter excerpt from Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna to Princess Marie of Romania

Nice, 12 February 1902

(...) Dear me, how I see now that Ducky also suffers intensely under her great fault of selfishness, and not admitting that she ever could have been wrong. Now comes all the bitter, bitter disappointment, the evidence that she had blundered, had made mistake upon mistake and through it, has never been able to have real friends who will stick to her in need! Neither amongst her suit or even her servants. (...) And now, I see how true it is. A little humility, yes, that is what she lacks.

(...)

She gave us a terrible fright about a week ago, as she went into a shameful fit of unbounded fury against Wilson (Elisabeth's nanny), about some letter from Darmstadt, mentioning her jewels. She began to scream in such a way that actually the whole of the servants rushed upstairs. She slapped Wilson and tore at her hair and made a dart at a big lamp to throw it at her head! Wilson had just time to seize it and carry it out of the room. Frightened maids rushed into my room to fetch me as the saving angel and I found her crying, but the first fury over. Everybody was trembling and quite pale... She recovered herself slowly. But since then, her maids are in a mortal fright. She sent her Babette to Darmstadt to see about her things and bring some jewels. The maid returned yesterday and Ducky went before her arrival with the Michas to Monte Carlo. The poor Babette came just now to me, trembling with fear at the idea of facing Ducky today and ghastly pale: she almost thinks that Ducky will murder her, when she returns today and begins to ask about Darmstadt.

...I promised to do what I an and will have to keep Ducky in sight. You know that she could have killed Wilson with greatest ease, the other day!... The whole house today is trembling at the anticipation of a terrible new outbreak, I see it in everybody's faces. And to think that it is all Ducky's own fault. I implored her since November to look about her things and say what she wanted to hace dine with them, begging her to have all packed and sent to the Schloss at Coburg. She would not move a finger, nor do anything, nut order that all should be left in its old place. Now this was impossible and Ernie had all packed and waiting for her orders: this terrible news the wretched Babette has to give her.

source: My dear Mama by Diana Mandache.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

1902

Letter excerpt from Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna to Princess Marie of Romania

Nice, 2 January 1902

Dearest Missy!

(...) We discovered next door to us an English family with children, so we want to ask them to play with Elisabeth. She is very happy here and has French and music lessons. Alas! Ducky does not occupy herself at all at this moment with her. The child is too much alone, it was even I who had to insist on arranging her lessons! The other day Micha (Grand Duke Mikhail Mikhailovich) came to luncheon and brought his two daughters very sweet, nicely behaved children, who remained the whole afternoon and had fun in the garden.

source: My dear Mama by Diana Mandache.

photo: Hessisches Staatsarchiv Darmstadt

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

1902

Letter excerpt from Princess Marie of Romania to Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna

Nice, 25 February 1902

Has Ducky any news from her daughter? Does she come back soon, I think the idea about Georgina (von Rotsmann) very good, one could not find anybody more utterly trustworthy.

source: My dear Mama by Diana Mandache.

photo: Hessian State Archives Darmstadt

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

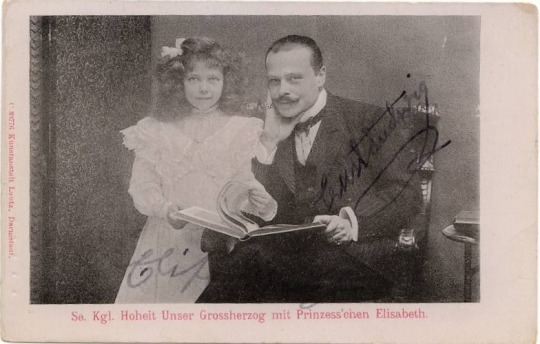

1902

Letter excerpt from Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig to his sister, Victoria Mountbatten

Darmstadt, 16 March 1902

Irène has returned to Kiel and my little one left me on the 12th after having remained exactly 5 weeks. You can think what a joy she was to me. But it was terrible to see her misery at leaving, for she has such a pronounced feeling for her home. I did everything I could to make it easy for her but alas that child feels herself such a Hessian that she is only contented when she is in the country, but now that she knows she can come home often again I hope she will get more quiet. I send you two photographs* of her and me which are quite good.

source: kindly shared with me by Thomas Aufleger from the Hessian State Archives. Thank you Thomas!

*according to Thomas those “two photographs” are the ones so often reproduced on postards.

One of the photographs was probably the image below:

28 notes

·

View notes

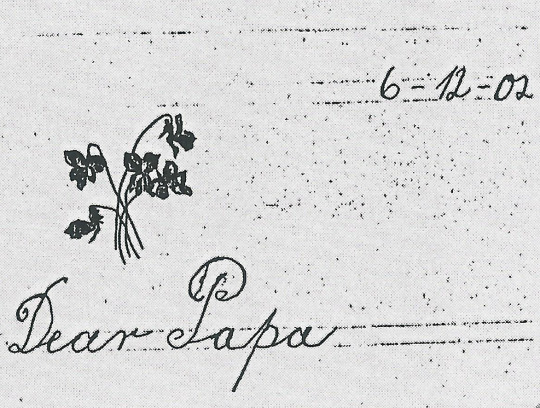

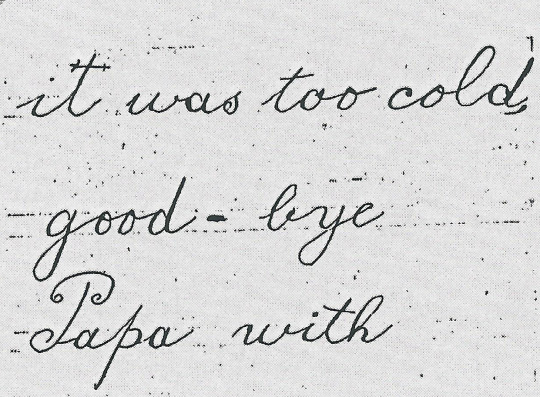

Text

1902

Excerpt of a short note written by Princess Elisabeth of Hesse to her father

source: Notizen zur Ortsgeschichte

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

1902

Letter excerpt from Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna to her daughter, Princess Marie of Romania

Nice, 12 February 1902

Now comes all the bitter, bitter disappointment. The evidence that she (Victoria Melita)... has never been able to have real friends who will stick to her in need. Neither amongst her suite or even her servants...

She gave me a terrible fright about a week ago, as she went into a shameful fit of unbounded fury against Wilson (Elisabeth’s nanny) about some letter from Darmstadt, mentioning her jewels. She began to scream in such a way that actually the whole of the servants rushed upstairs.

She slapped Wilson and tore at her hair and made a dart at a big lamp to throw it at her head. Wilson just had time to seize it and carry it out of the room. Frightened maids rushed into my room to fetch me as the saving angel and I found her crying, but the first fury over. Everybody was trembling and quite pale… You know that she could have killed Wilson with the greatest ease.

source: From Cradle to Crown

photograph: my own collection

21 notes

·

View notes