#3E-French Politics

Text

#INDUSTRIES#3E-Energy#3E-Politics#3E-Coalition Politics#3E-European Affairs#3E-Green Movement#3E-Academic Research#3E-Environmentalism#3E-Political Activism#3E-Clean Energy#3E-French Politics#3E-German Politics#3E-Nuclear Power. . VALUES#3E-Accountability#3E-Humanism#3E-Integrity#3E-Justice#3E-Respect. / TRAITS#3E-Positive attitude#3E-Excellent communication skills#3E-Leadership#3E-Patience#3E-Open-mindedness#3E-Motivating others#3E-Problem-solving ability#3E-Political savvy#3E-PR experience#3E-Knowledge of French and European politics#3E-Public relations expertise

0 notes

Text

Le 3e Gédéon

I was hesitating to talk about it but here we go. May I introduce you to the manga "Le 3e Gédéon".

Warning long post

What it's about ?

Manga in 8 volumes, it tells the story of Gédéon Aymé who dreams of becoming a deputy to the Estates General to save the people from misery. George, the Duke of Loire and his former comrade, also seeks to change the system, but instead use violence to achieve his goal. This is going to be a story where the two characters will fight each other, one wanting peace and peaceful change, the other a radical and violent change.

What did I think of it ?

I found the story good. It manages to mix fiction and French revolution. It's full of inconsistencies but somehow it works. However I wouldn’t advise this manga to everyone. There is psychological and physical torture, gore and nudity. The images can sometimes be very crude.

What about historians characters ?

Well, we have the most badass portrayal of Louis I've ever seen in my life, he’s able to detect the slightest lie. Marie Antoinette may seem shallow, but she knows perfectly well how to play her charms to turn the tables in her favor. Their couple is interesting because each of them can't really love the other completely. Madame Roland is an ambitious woman who we learn had a daughter with Gédéon. Saint-Just is the slightly confused teenager who will eventually grow up and assert himself. Charles Philippe, the sociopathic Count of Artois, wants his brother's place and Elisabeth, the king's sister, wants Marie-Antoinette's place.

But what about Robespierre ?

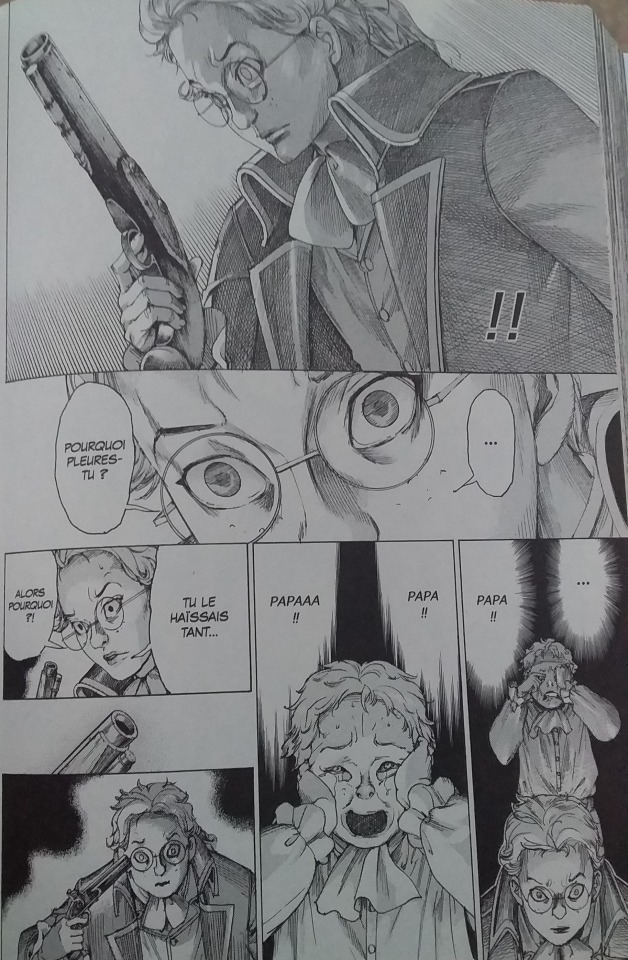

I said in an old conversation that Maxime had daddy issues. Let me explain. One of the main themes of this manga is family and father figures. We learn that Gideon's father is the duke and he has exchanged his son's place with George so that Gédéon can be closer to the people. George has a real grudge against the duke because when Gédéon will be older, he should have become a servant again. But by trapping Gideon he kept his place.

Maxime has a real grudge against his father and George will use this information to manipulate him.

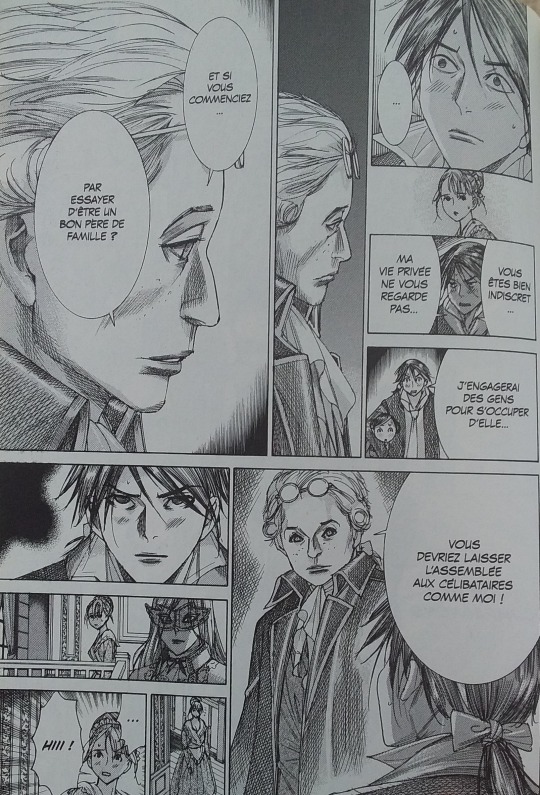

The first time we hear about Robespierre is in the first chapter. George is looking for easily manipulated men who can help him destroy the old system. Saint-Just, recruited by George, tells him that Max would be a potential candidate. Maxime is invited to George's house and has to save a former peasant, now a bandit, from the death penalty because he attacked George. Of course Maxime succeeds but it was a test. Of course, George can’t deny Maxime's skills but I believe it’s hearing the conversation between Maxime and Gédéon about Gédéon’s daughter that made him decide :

Robespierre : Shouldn’t you start trying to be a good family man ? You should leave the Assembly to single people like me !

We see Robespierre again later in a rather amusing scene with Gédéon. Gédéon, drunk, says Saint-Just's erotic writings told the boy is a virgin and is amused. And who is the virgin in the same bar as Gédéon? Boom Maxime !

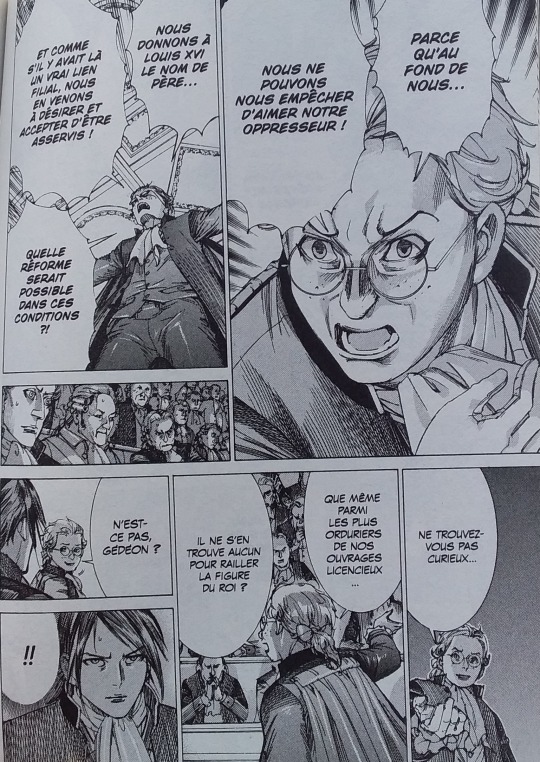

Their following conversation will confirm that Louis XVI is the father of the kingdom.

Yeah, but when does George act ? Well, Gédéon sees Maxime again when the Estates General stagnate and there is a talk about creating a new assembly. Since Gideon is now part of the King's police force, Maxime asks him if he can meet the King discreetly to solve the problem. But without clearly knowing it, George is already starting to manipulate Maxime.

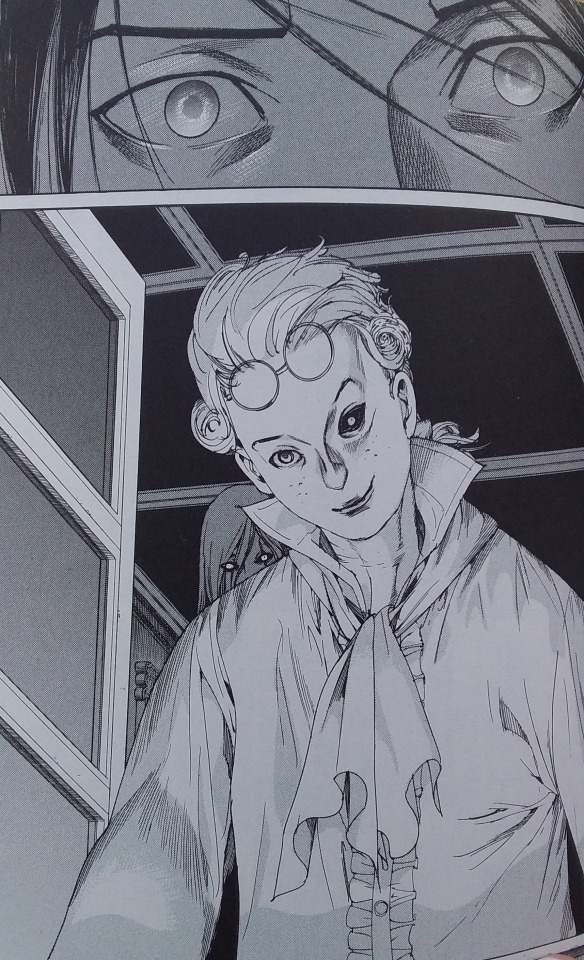

Keep in mind the puppet representation. It will be important for the next step. Because it’s present when Maxime's words contradict a part of his thoughs and when this thoughs takes controls.

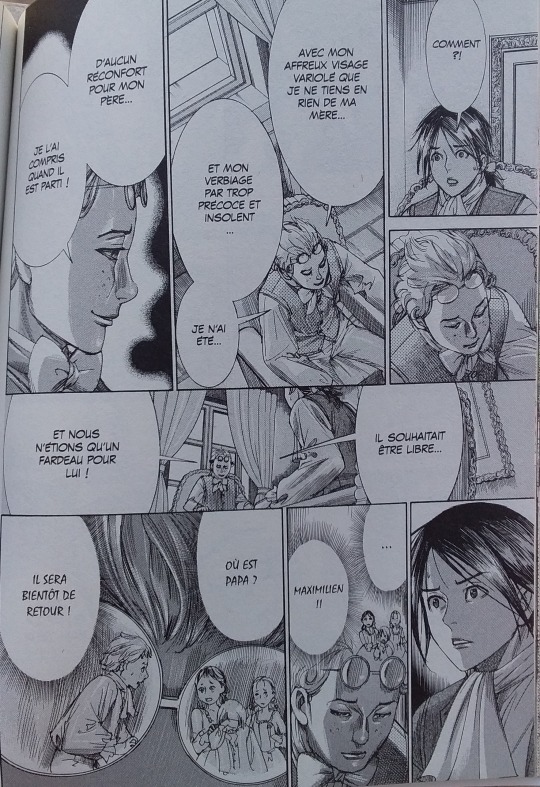

After Gédeon refuses to join Saint-Just, Maxime explains to him, if Gédéon continues to hang out with the royal family, there will be repercussions. And if Gédéon tries to find his lost daughter and make politics at the same time, he will lose both. Because for Maxime, children are burden to their parents. Maxime explains his childhood, his dead mother and his father who left. He is resentful of himself because he believes it was his behavior as a child that made his father disappear, that he was a burden to him. This is why he doesn’t want children.

But underneath this justification, even if he pretends the opposite, he has hatred towards this father who abandoned him.

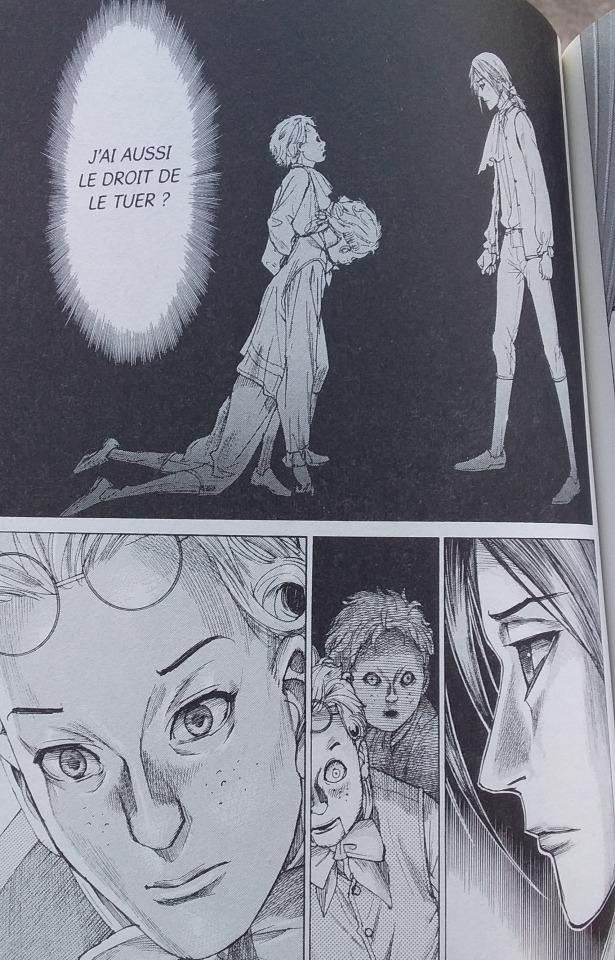

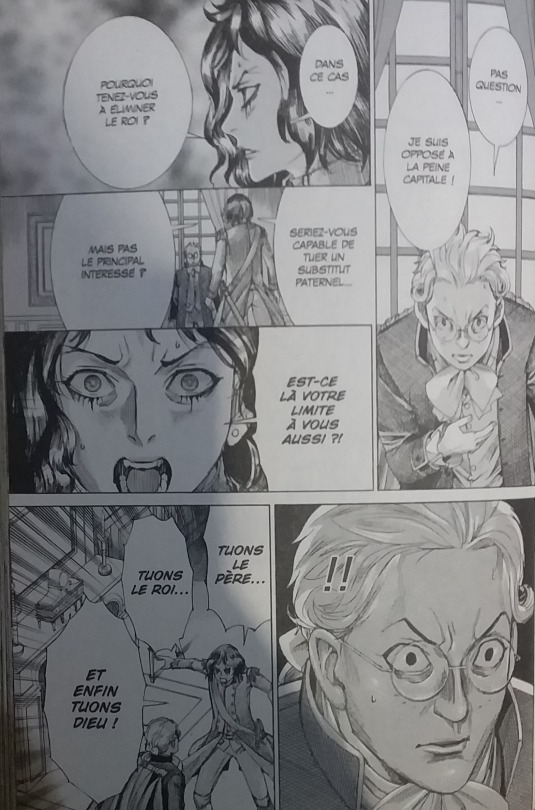

Gédéon : You have the right to hate your father.

Robespierre : In this case, I have the right to kill him, right ?

On the day of the meeting with the king, on the way to the palace, Maxime admits to Gédéon that his father sends him letters. In this letters, his father talks about his new family. Of course he knows that this is probably a trap, but we feel that it’s a sensitive subject for him.

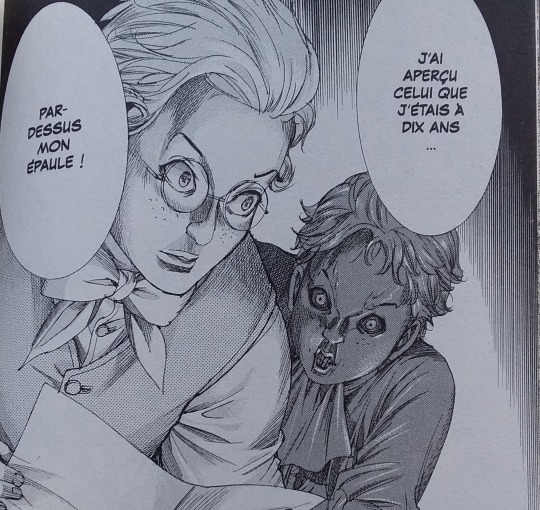

Robespierre : Over my shoulder, I saw myself when I was ten years old.

Then comes one of my favorite scenes, a scene of tension between Louis XVI and Robespierre. Louis explains there are three locks on the table, if he thinks Maxime is lying, he will break one of them.

Robespierre : Since that time, I have always respected you as a father.

Louis XVI : One...You were warned, lies don't work. Either you don't respect us, or you don't respect the concept of a father.

After two, Maxime admits being one of the instigators of the problems at the Estates General and to make it stop, Necker must be dismissed because he makes promises that the nobility will never accept. Louis accept to think about it.

And here comes the chapter where I most wanted seeing George to lose and die painfully because his plan is totally twisted. Maxime receives a letter from his father who tells him that Henriette might not have died if he had been there, implying that it is Maxime's fault that he left. Then Maxime sees in front of his house a woman abused by a man. He threatens to take him to court but the guy explains that Maxime has nothing to say about the correction of a husband to his wife, named is Henriette...Oh boy !

The next day, Maxime proposes her to leave her husband, that he can help her by offering her a place in the convent of Arras. There, she would be safe. But she refuses because her husband will find her and she is unworthy of his help. Maxime feels unable to do anything. He remembers his dying sister. In the evening, another intermission, but this time Maxime decides to act. He intervenes until the girl confesses her father married her.

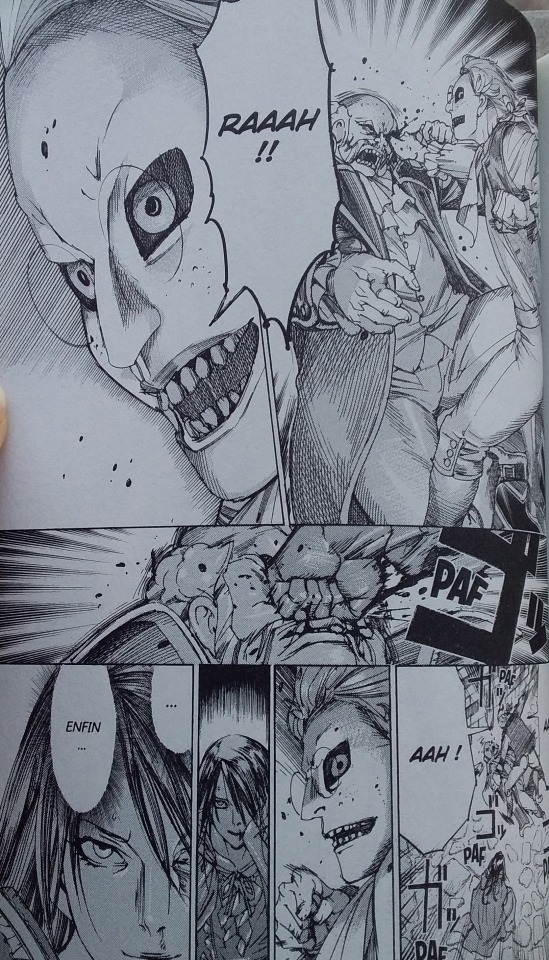

At this words, Maxime becomes mad and releases all the hatred he has accumulated towards his father. George's plan to make him forget any peaceful method succeeded

Robespierre now lets his hate guide him. If Louis is the father of the kingdom and the father of his subjects, then he must pay too. He goes to see Necker, tells him to accept his resignation to become a martyr and harangues the assembly to join the people and take up arms. He explains the first attack will be at the Invalides, then the people need to take care of the Bastille afterwards, because it is a royal symbol.

Camille : Maxime notice me !

Gédéon doesn’t agree with Robespierre, he thinks it’s necessary to think of a more peaceful method because it risks having deaths. He no longer recognizes his friend

Robespierre : I assure you Gédéon, I haven’t changed. Gentlemen ! Listen up ! We've been trying to find a resolution through dialogue for a long time! Alas, all our efforts have been in vain...a pure waste of time...and why !?

Robespierre : You too, Gédéon, I bet you've seen abused children love their fathers so much that they fall apart.

Gédéon: Yes...

We see him again only after the march of the women on Versailles. Gédéon tells him that George is the one who sent him the letters and played on his dislike for his father to kill the king. He wants to find the wise and peaceful Robespierre.

Gédéon : And this other one love his father.

But Maxime does not believe him. His hatred is still too strong. When another lawyer asks Maxime to save a man, Maxime takes time to think, because the man looks like his father. It’s the words of Saint-Just that convince him to give up this man because he had previously seen the damage caused by the Duke of Loire on his sons George and Gédéon.

Robespierre : He’s a complete stranger, there is no doubt about it !!

Saint-Just : Wouldn't it be better if he were really your father? If he were condemned to death, you would be delivered from him.

Saint-Just : Destroying everything to build a new order, that's what I think revolution is !

Finally, Maxime is released when the king died. Gédéon has found the death certificate of his father, confirming Maxime has sent an innocent man to death. Maxime seems to be happy on the day of the king's death but when he saw George and reconised him as the girl he tried to save, everything gets destroyed. He cries because after all he has done, he cannot go back.

Saint-Just embraces Maxime who he’s crying : I will always remain at your side, until death separates us.

The last time we see him is when marie-Antoinette curses him and other revolutionaries at her execution;

I reconize Saint-Just, Robespierre, Desmoulins, Marat ? (right middle), Danton, Hébert, Mme Roland, Augustin ? (bottom right)

#frev#mangafrev#robespierre#saint just#louis xvi#marie antoinette#if anyone reconize all the revolutionaries at the end just tell me please !!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The earliest known French bookstamp, and a new addition to the library of a colorful bibliophile: Jacques Thiboust of Bourges

Fifty-two discoveries from the BiblioPhilly project, No. 6/52

Georges Chastellain, c. 1402/1410–1475, L’outré d’amour pour amour morte, Philadelphia, The Rosenbach Museum and Library, MS 443/21, fol. 1r, with miniature showing The author dreaming

While being attentive to the circumstances surrounding the genesis and production of a Medieval or Renaissance manuscript is often our primary concern as scholars, sometimes the subsequent destiny of an item can be equally engaging, if not more so! This is especially the case when the attested later owner(s) of the book are A) relatively close in date to the production of the manuscript and thus valuable as a witness to the early diffusion of a particular text, and B) known to have owned other books and recognized for having had a particular focus to their bibliophilism. Today we will examine a manuscript which, though notable for its textual content and illustrations, is of further interest due to its rich early ownership history, which has never before been remarked upon.

This short, rhymed work in French by the Burgundian chronicler and poet Georges Chastellain (c. 1402/1410–1475) is entitled L’outré d’amour pour amour morte, which can be rendered in English as something resembling “The Lover’s Lament over the Death of his Love” (see here for the digitized version of the modern critical edition).[1] The manuscript is housed at The Rosenbach Library and Museum as MS 443/21. The author, Chastellain, was a prominent figure at the Burgundian court, serving dukes Phillip the Good and Charles the Bold with distinction. L’outré d’amour, written in 214 octosyllabic octets, is an example of a Roman à clef, a narrative describing actual events presented as a fictional account using altered names. This is a later name for the genre, but this type of work was popular in mid-fifteenth-century Franco-Burgundian culture, where a fractious political situation sometimes made the overt enunciation of one’s political views problematic.

The Rosenbach manuscript, which is missing four stanzas between folios 7 and 8, was likely produced in Western France in the 1460s or 1470s, judging by the style of the bâtarde script and the four unframed miniatures (four more spaces for miniatures remain blank); it may well date from Chastellain’s lifetime. Ours is at least the seventh known manuscript copy of the text to be identified, and it can be added to the five exemplars listed in the Archives de littérature du moyen âge (none of which is currently fully digitized), and a copy at the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal with eleven miniatures that has very recently been digitized. Chastellain’s text became quite popular in the early sixteenth century, as it was included in the earliest printed anthology of Middle French poetic texts, the Jardin de plaisance et fleur de rethoricque, first issued by the Parisian printer Antoine Vérard in 1502 and re-printed no fewer than eight times before 1528.

MS 443/21, fol. 1r and Georges Chastellain, L’Oultré d’amours pour amour morte, Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Ms 5118, fol. 1r (253 x 174 mm versus 203 x 143 mm in size)

Given the popularity of this text in Renaissance France, the manuscript in question is especially notable on account of its subsequent presence in an important library some fifty years after its creation, when it was well on its way to becoming a classic. The Rosenbach manuscript was in fact once owned by Jacques Thiboust (1492–1555), a noted humanist book collector in early-sixteenth-century France.[2] Thiboust trained as a jurist and remained deeply devoted to the region around his native Bourges, in the Berry. He served as a notary and secretary to King Francis I and his sister Marguerite de Valois in an illustrious career that brought him into contact with a wide range of poets and chroniclers. He is best known for being at the center of a literary circle of friends in Bourges in the 1520s, 30s, and 40s, which brought together local clerics, merchants, scholars, and physicians, but also such luminaries as statesman Guillaume Bochetel, the archbishop of Bourges Jacques Leroy, the poet and translator of classical texts François Habert, and the eminent poet Clément Marot. Thiboust’s renown was such that already at the age of 24 he was the subject of a portrait, currently untraced, by the leading French court artist of the time, Jean Clouet. A number of personal manuscripts in Thiboust’s own hand survive, recording his land holdings surrounding his manor at Quantilly, near Bourges (Bourges, Archives départementales du Cher, G 61 and E 108; Paris, BnF, MS fr. 32954). A fascinating Friendship Book or Liber amicorum that belonged to Thiboust (Paris, BnF, MS fr. 1667) contains numerous odes and poems to Thiboust’s many friends.

We know the precise details of Thiboust’s acquisition of the Rosenbach manuscript on account of an autograph inscription he wrote on the inside front cover, in a fine bâtarde script. It reads: “C’est au Seigneur de Quantilly M. Jacques Thiboust, notaire et secrétaire du Roy et esleu en Berry. Et le luy a donné sire Jehan Jaupitre son frère. En mars 1535.” (“This belongs to the lord of Quantilly Mr. Jacques Thiboust, notary and secretary to the King, and elected in Berry. And it was given to him by his brother Jean Jaupitre, in March 1535”). Jaupitre appears to have been Thiboust’s wife Jeanne de la Font’s half brother; the manuscript thus exemplifies the type of infra-familial gift of a book that was becoming so popular in Renaissance France. “Des livres de M. Jacques Thiboust” (“From the books of M. Jacques Thiboust”) is additionally written on lower pastedown, and the date of “mars 1535” is repeated on recto of first flyleaf. The title of the work, “Cy commance le livre de l’outré d’amour pour amour morte,” has also been added in upper margin of folio 1r. Like other books that belonged to Thiboust, this manuscript has his name all over it!

MS 443/21, upper pastedown, with inscription by Jacques Thiboust, and lower pastedown, with additional inscription

As if that weren’t definite evidence enough to establish ownership, the manuscript bears Thiboust’s unique, ink-stamped ownership mark on the verso of the front flyleaf and the verso of folio 37.[3] The bookstamp displays Thiboust’s arms. These are, in French heraldic terms: “écartelé au 1 et 4 d’argent à la face de sable, chargé de trois glands d’or accompagné de trois feuilles de chêne de sinople, deux en chef, une en pointe; au 2e d’argent à une anille de moulin de sable [Dumoulin] ; au 3e d’or à deux perroquets adossés de sinople [Rusticat]; et sur le tout d’azur à une étoile-comète d’or [Villemer]. Above and below the square armorial are the mottoes, in Latin and French respectively, “Lex et Regio” and “Qui voit s’esbat,” which can be translated “Law and Region,” or “Law and Land;” and “He who sees frolicks, relaxes, or amuses oneself.”). The latter is in fact an anagram of Thiboust’s first and last names (switching I for J and a V for a U), devised by the noted poet Clément Marot.[4] For good measure, the French motto has been recopied in pen below the stamp on folio 37 verso, and signed, again, by Thiboust himself.

MS 443/21, flyleaf i verso and fol. 37v, showing the armorial bookstamp, motto, and signature of Jacques Thiboust

Thiboust’s serially reproducible woodcut ownership mark is the earliest of its kind to be used in France, and perhaps the earliest (Western) bookstamp impression to survive. It is found in other fifteenth-century manuscripts he owned (for example the anonymous La voie d’enfer et de paradis, Les Enluminures, TM 775; see their excellent description and photos), in contemporary printed books (a copy of Le couronnement du roi François [Paris, 1520] held at Yale University Library), and in significantly older items, including this twelfth-century version of Josephus’s Antiquities, now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (ms. lat. 15427), which he gifted to his friend Bochetel. The Philadelphia manuscript is a previously unnoticed addition to Thiboust’s library, and further confirms this humanist bibliophile’s interest in the creation of a French literary canon through the collection of manuscript exemplars, even at a time when this text was widely available in print.

La voie d’enfer et de paradis, Bourges, c. 1460. Les Enluminures, TM 775, verso of final flyleaf-fol. 1r, an example of another mid-fifteenth-century French manuscript with Jacques Thiboust’s bookstamp and inscription

[1] For L’outré d’amour, see Lemaire, Jacques, “L’Oultré d’Amour de George Chastelain: un exemple ancien de construction en abyme,” Revue romane 11 (1976): 306-316.

[2] For Jacques Thiboust, see Boyer, Hippolite, Un ménage littéraire en Berry au XVIe siècle, Jacques Thiboust et Jeanne de La Font (Bourges: Impr. et Lithographie de Ve. Jollet-Souchois, 1859; Omont, H., “Un Nouveau Manuscrit de Jacques Thiboust de Bourges,” Revue d’Histoire Littéraire de La France 4, no. 1 (1897): pp. 92–97; and Le Clech-Charton, S., “Jacques Thiboust, notaire et secrétaire du roi et familier de Marguerite de Navarre: amitiés littéraires dans le Berry du ‘Beau seizième siècle’,” Cahiers d ‘Archéologie et d’Histoire du Berry 96 (March 1989), pp. 17-28; other books owned by Thiboust are discussed in Le Clech-Charton 1989.

[3] For Thiboust’s stamped bookplate, perhaps the earliest of its kind to be used in France, see Rau, Arthur, “The Earliest Extant French Armorial Ex-libris,” The Book Collector (Fall 1961), pp. 331-332.

[4] See Boyer, Un ménage littéraire, p. 58.

from WordPress http://bibliophilly.pacscl.org/the-earliest-known-french-bookstamp-in-a-book-owned-by-the-humanist-collector-jacques-thiboust/

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

China Intimidates Taiwan

LOS ANGELES (OnlineColumnist.com), Oct. 5, 2021.--Flying 145 warplanes over the Taiwan Strait, 68-year-old Chinese President Xi Jinping gave the green light to the Peoples Liberation Army [PLA] to menace Taiwan, and, more to the point, at the United States. Since signing the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty Dec. 2, 1954, the U.S. was obligated to provide for Taiwan’s mutual defense, something threatend by Chinese Premier Mao Zedong. Mao didn’t like after the 1949 revolution, Chiang Kai-Shek fleeing with his band of Chinese nationalists to the Island of Formosa with U.S. military help. Mao shut the door on U.S. diplomatic relations until former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger opened the door Feb. 17, 1971for President Richard Nixon to reestablish diplomatic ties with China Feb. 21, 1972, opening the doors for today’s strong business ties with the Peoples Republic of China [PRC]. Xi considers himself a Mao disciple, despite calling himself president and acting more Western.

When the U.S. and Australia announced Sept. 22, before the U.N. General Assembly, a nuclear submarine deal with Australia, the French weren’t the only one that went ballistic. Xi gave the green light for the PLA to torture Taiwan, daring the U.S. to intervene. Sending 145 war planes into the Taiwan Strait sends a loud message to 78-year-old Joe Biden to not do anything stupid. State Department spokesman Ned Price said the U.S. has Taiwan’s back but only symbolically, since it’s doubtful the Pentagon would intervene to defend Taiwan in the even of the Red Chinese invasion. U.S. government under President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the U.S.-Sino Mutual Defense Treaty in 1954, pledging military support to Taiwan. But once Nixon and Kissinger opened up diplomatic and trade relations with Beijing, the U.S.-Sino Mutual Defense Treaty was invalidated. When the U.S. signed the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act., mutual defense was not part of the deal.

Even though Australia won’t get its nuclear subs until 2040, Xi went ballistic, threatening Taiwan and the United States. Xi doesn’t like when the West questions his authority, especially in the South China Sea where the International Court of Justice at the Hague ruled in 2016 that China violated international rules of the sea. China thumbed its nose at the Hague’s ruling, continuing to build out military installation in the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea. China sees any foreign power as an intruder in international waters, violating the rules of the sea. U.S. officials found out the hard way April 1 2001 when China intercepted a US. EP-3E Aires surveillance plane, forcing it down on Hainan Island, holding U.S. crew hostage for 10 days. Pentagon officials received the plane back completely dismantled, to enable the PLA to reverse engineer the EP-3E. China becomes easily threatened by the United States or its allies.

Pentagon spokesman Ned Price said the U.S. was concerned about China’s aggression especially in the Taiwan Strait. Xi didn’t like when 58-year-old Secretary of State Antony Blinken and 44-year-old National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan accused Beijing March 18 at a get-to-know you summit in Anchorage, Alaska, of committing genocide against Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang Province. Blinken and Sullivan also criticized Beijing for cracking down on pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong. Antagonizing Xi has led to the current tensions with Beijing. Xi’s daring the U.S. to intervene militarily in Taiwan, potentially starting a regional, if not world war. Price talks tough about defending Taiwan but he has zero leverage in the Pacific Rim when it comes to China. Taiwan wants no part of any war with Beijing and would instead prefer to join Beijing’s confederation, despite the history of independence since the 1949 Maoist Revolution.

When former President Jimmy Carter signed the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act, he agreed to recognized Beijing as the only China. Unlike Hong Kong where Beijing agreed to allow the once British Crown Colony some measure of autonomy, Beijing resents Taiwan’s relationship to the U.S. When Australia agreed to buy nuclear submarines from the U.S. to patrol the Pacific Rim including the South China Sea, that was the last straw to Xi. Xi looks to do anything to divert attention away from China hatching the deadly novel coronavirus in a Wuhan laboratory, then spreading it around the planet, infecting nearly 237 million, killing over 4.8 million worldwide. Xi would like nothing more than to divert world attention away from the origin of the deadly coronavirus and onto Taiwan. Pentagon officals know that they’re in to position to start confronting China in the Pacific Rim. Taiwan Relations Act assured that would not happen.

China’s motives for sending 145 war planes into the Taiwan Strait is a clear show on force to the U.S., calling Biden’s bluff. Xi knows that he can get away with murder in the Taiwan Strain, knowing the Pentagon has no obligation under the Taiwan Relations Act to defend Taiwan. Carter’s Taiwan Relations Act surrendered Taiwan to Beijing, forcing the U.S. to no longer call Taiwan the Republic of China. China has been in a global effort to throw money at third world countries, competing with the U.S. for global influence. When it comes to Africa and South America, China has far more clout in the developing world than the U.S. Xi decided to menace Taiwan after Biden cut a nuclear sub deal with Australia. Flying over 145 war planes over the Taiwan Strait, Xi hopes to divert attention over efforts to determine the origin of the deadly novel coronavirus. Pentagon officials know that the U.S. cannot defend Taiwan from the Beijing invasion.

About the Author

John M. Curtis writes politically neutral commentary analyzing spin in national and global news. He’s editor of OnlineColumnist.com and author of Dodging The Bullet and Operation Charisma.

0 notes

Text

Now I’ll talk about our educational system.

it is COMPLICATED. REALLY. Even I can get lost in here!

Children usually start school when they are 2 years old. At age 2 they enter the phase called “Maternelle”, where they learn the basics, until they enter primary school (at age 5-6).

How to live with other kids, colors, numbers, how to read their own name, all of that. They are lucky, the little monsters get to take a nap each afternoon at school!

This step in education isn’t mandatory, Parents can put their child directly in primary school when they are 6. Or can wait a little because their kid isn’t ready. By ready, we think “when they are not clean” (meaning, not ready to stop the diapers). In big cities like Paris it’s more complicated. Kids don’t go to school when they are 2 years old because there are too many kids for a limited amount of kids allowed, so it’s not uncommon for them to begin school later.

After the Maternelle, here we go to serious business! At 6 years old, kids enter the first phase of mandatory school. It’s called Ecole Primaire. They are supposed to know the very basics, so now, let’s teach them how to read,maths, English, and all that. Kids are in this phase until they are 10-11 years old.

After that, it’s College! Not your college. Not university! xD. It’s like middle school. The education is a little more advanced than the previous phase.

The name of the different classes are funny. See, at the end of our High school years, we have to take an exam. THE exam. well, in our Colleges, the year we’re in is the count of how many years are left before we take this exam. :D

For example. you have four years of College. The first one is “6e”, second “5e”, the third “4e” and last one “3e”. At the end of college we take an exam, called “Brevet des colleges”. Completely useless, but necessary. you have to take tests in Maths, French and History and Geography.

Afterwards, it’s High School. The kids are now between 15 and 18 years old. You call this high school, we call it “Lycée”.

The messy one, really. Here, you are supposed to have chosen a path for your future. And it IS complicated.

Your diploma can be completely different from another kid.

The biggest exam, the most important one is called Baccalauréat (or “Bac” for short). But there are TONS of different baccalauréats. They depend on which specialty we choose.

We also have smaller diplomas, but I won’t talk about them. They exist, but are useless, and it’s not necessarily a good thing when we have them and not the Bac.

First, we have the general paths. Yes, in plural. 3 different baccalaureats.

-> The scienctific Baccalauréat (or as we call it “Bac S”). Maybe the most complicated of all, and also the most valuable. You have to study HARD to get it. Physics, Biology, Math... you name it. it’s the hardest. My sister passed this one a looooong time ago.

-> The economic Baccalauréat (we call it “Bac ES”). The second hardest to pass. You learn politics, economics, of France but other countries too, especially European ones to understand the economic context. And social studies. Maths, foreign languages, history and Geography are very important subjects. I passed this one. and oh Boy I have never written so much in my life. in all subjects ... This bac is almost as appreciated as the sciences one.

-> The litterature Baccalauréat (called “Bac L”). This one is hard to have, but doesn’t offer many opportunities, except for teaching. Most of the people who passed this one ARE teachers. two friends took it, and they are teachers now xD.

These were the general bacs we can have. Our specialty begin different, the exam is different.

Now we have all the others. They are more technical. We have for example a baccalaureat in electronics for example. each technical field has it’s own baccalauréat. It really depends on which path we choose when we enter High School. The exams are completely differents from each other, but they have the same name.

Now, kiddies are grown up now, they can go to universities!

haha, if only it was that easy. Most people having a general Baccalauréat (S, ES or L), tend to go to university, it’s true. I went to university at first to be a translator. BUT we have other options.

For example, we can stay in High school for two more years. It’s another diploma, called “Brevet de Technicien Supérieur” (BTS for short). Any domain. Economics, Sciences, technology, Marketing, you name it. I have one, in programming :D

You may stay in high school for two more years but your status changes. You go from pupil to student. It is a huge deal in France, because we have a lot of advantages when we are students. Especially smaller prices in cinemas, museums, or in transports. When you pass, you have a new diploma, and can continue in university or in other schools.

Other than that, we have Engineering schools, or school/work. You have like one week a month at school and the rest is at work. Very useful to get an experience, but unfortunately, finding a company is very very hard.

But one thing is sure. No matter how many years you spend at schools/ university, the Baccalauréat is ground Zero. The very base your diplomas. If you had another diploma two years after the bac (like the BTS as said earlier), you are a Bac +2 (baccalauréat + 2 successful years of studies, proved by a new diploma).

I’m personnally a Bac +3. I have my Baccalauréat diploma, My BTS diploma, and another diploma.

As I said, it’s really complicated, but I gave a summary of what it’s like. Some people are bac +5 (engineers) or even bac +8 (equivalent of PhD). I know I don’t have the patience to go that far.

I changed paths and went from foreign languages to programming, but it was possible because my education in high school opened the way to this opportunity. Some aren’t this lucky.

I need to add the fact that our education system is FAR from perfect. A lot of things need to be changed, and the discipline is a disaster. I’m trying to give the most objective explanation because If I begin to put in my thoughts, it can become a disaster.

Funny thing is that in High School, especially in Geography, we had a small test where we had to know the location of EVERY. COUNTRY, in the European Union. We had to put them on a blank map, and we had to write WHEN they entered the EU. It was the worst test xD.

I feel the need to add that our grading system isn’t the same than in the US. From what I know, you use letters.

We use numbers. From 0 to 20. A- or A++ don’t exist here.

from 0 to 5 /20 -> bad

from 6 to 10/20 -> m’kay

from 11 to 15/20 -> good

from 16 to 20/20 -> very good;

I’m not trying to find an equivalent with the letter system because I don’t understand it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

NATO Imagines Future Warfare

Innovation is a key component of readiness when it comes to future threats. NATO’s Innovation Hub recently commissioned a short story from author August Cole, asking him to draw upon his writing and imaginative abilities to create a picture of what NATO operations could be like in the year 2040. The Cipher Brief is pleased to be able to bring you 2040: KNOWN ENEMIES, with permission from NATO.

CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES — PARIS, FRANCE

The protestors’ braying air horns reminded Alain Durand of the feel of his father’s hand squeezing his as they watched the Tour de France peloton speed by on a verdant hill outside Chambéry, half a lifetime ago. Tonight on the Champs Elysees it meant drones. It meant gas.

He carefully pushed aside two old fashioned white cloth banners — “PAX MACHINA” and “NON AUX ARMEES, NON A LA GUERRE,” written in thick red brush strokes to better see. In a field of view populated with synthetic representations of the real world, the banners were anachronistic but also enduring. They spoke to the necessary spirit of dissent in one of Europe’s more temperamental democracies, Alain thought. Yet it was time to change again: France was the last NATO member, other than the United States, to maintain conventional combat forces. The other members had already robotized.

“A matter of not just tradition but national survival,” his father, a colonel in France’s 3e Régiment de Parachutistes d’Infanterie de Marine, always insisted.

The horns stopped. The crowd of thousands hushed to better hear the whine of the oncoming Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité riot-police crowd-control drones, a sound like a frantically played piccolo. It was a child’s sound — that was why it intimidated. The flight of a dozen drones hovered in a picket formation in front of the crowd of more than 10,000 marching along the cobbled stones toward the Arc de Triomphe. On Alain’s augmented reality glasses, the bots were bright orange dots, tagged with comments from around the world guiding him on everything from how to download apps to jam their controllers to offers of legal representation. Alain reached into his satchel and cursed, as an ad for gas mask replacement filters popped into view.

A protestor’s drone, bright yellow and the size of an espresso cup, darted past him, then returned to hover in front of his face. It was filming. He could see the live feed it broadcast on his own glasses, identifying him as the son of a senior army officer. He looked around, feeling a need to disappear in the crowd even though that was impossible. He swatted at the yellow drone, and it darted off.

Was that a Catalyst design?, he wondered. The mysterious informal global network emerged on the public stage about three years ago, fomenting dissent and countergovernment action in the virtual realm. It started with what was essentially algo-busting or AI-enabled augmented-reality pranks to make a point about excessive Chinese and American influence around the world. But in the last six months, something had changed, and they were now moving from the online to the real world, supplying not only plans for printable grenades or swarm drones but also the fabs to make them. They had never tried to operate in Europe before, or the U.S. Was this drone a sign something was changing, literally before his own eyes?

Those same eyes began to itch. He had other things to worry about for the moment.

“Juliet, I don’t have my mask,” he said to his sister. She already had hers, a translucent model with a bubble-like faceplate that made her look like a snorkeler.

“And?” she said.

“I am certain I put it in there, but …” he trailed off.

She sighed angrily, condensation briefly fogging her mask. Four years younger, his 15-year-old sister could judge him harshly. She got that from their father.

“We stay,” she said, passing him a bandana and bottle of water. “Parliament votes tomorrow. Father is already deployed. If we leave now, when will we ever stand?”

“Ok, ok,” Alain muttered. He wet the bandana and braced himself for the gas.

Drones dashed just a few feet overhead, a disorienting swirl of straining electric motors and the machines’ childlike tone. The crowd sighed all at once and then individual shouting erupted around him. A moment later his eyes began to sting. Fumbling with the bandana he quickly wrapped the wet cloth around his mouth. But, eyes now burning, he struggled to tie it around his neck. With so much gas in the air, no one without a mask would be able any more to continue watching the eruption of digital dissent. He felt Juliet’s fingers on his neck, helping secure the bandana’s knot. Hands now free, he angrily pumped his fists in the air and blindly grasped to help hold his cloth banners aloft.

JULIUS NYERERE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT — DAR-ES-SALAAM, TANZANIA

It was so hot, when the convoy stopped at the main gate to the joint United Nations-African Union compound, that the German and Italian battle bots broke formation. The NATO task force’s hundreds of small armored wheeled and tracked machines jerked and shimmied like ants as they fought over the shade beneath the bright blue revetments — towering stacks of shipping containers reinforced with blast-foam. That left the French para forces, what NATO classified as a light-effects company due to its mostly non-robotic composition under, in the crushing heat with nowhere to go. That was fine for the French unit’s commander, Luc Durand. His men and women could handle the heat; the bots were another story.

Captain Monika Toonce hopped off one of the oversized German Jaeger crawlers and jogged over to Durand’s open scout car. The French convoy included the jeep, six-wheeled troop carriers (each carrying 12 paratroopers as well as external racks of offensive and defensive smallbots), and four mules loaded with ammunition, spare parts, and assorted spider-like fixers.

“Colonel, we are still waiting for the clear codes before the task force can enter the compound,” Toonce said. She paused to wipe sweat from her nose. “Headquarters said they sent them. But they are not yet authenticated here …”

Durand cursed. The bots would not yet be cleared for self-defense, let alone offensive use. He forced himself to ease back and put his boot up on his jeep’s wheel well, a pose he could hold for hours on a high-speed cross-desert dash or pulling security at a vital intersection. This is an old problem in a new form, he thought. This is why the French army trains to fight with or without machines. “La victoire ne se donne pas!” was the motto adopted four years ago.

Deconflicting the newly arrived German and Italian anti-armor/aircraft and counter-personnel bots with the existing UN-AU peacekeeping forces — so that they didn’t automatically attack one another — was just another form of confusion and complexity. For all the advantage the machines offered, they also brought the onset of the fog of war forward that much earlier in a conflict. Ignoring Toonce, Durand drew with his finger on the dusty screen he wore at his waist, a series of arrows to sketch out a concept. He snapped a picture of the tracings with his glasses; it was something he would write up when he got back from deployment. You never know where inspiration will come from.

“Ok, you want to ride with us then? We are heading in. The machines can handle themselves, no?” Durand said.

Toonce looked torn between waiting with the disabled bots or accompanying Durand. Her responsibility for the German armored forces was a significant one, given the expense and competition for deployment-likely slots in the Bundeswehr. There were fewer soldiers in the German army today than there were postal carriers in Bavaria. Why they kept so many of the latter and so few of the former us was not something Toonce allowed herself to weigh too deeply. She loved the army, loved her comrades and their machines.

Toonce nodded. The maintenance techs were still on the way. She was the sole German representative, and she told herself she needed to be present when the NATO task force leaders finally presented themselves.

The two soldiers were in a narrow pause, a lull — in what had been fevered fighting — that the NATO task force had taken advantage of to deploy by air from a staging area outside Nairobi.

“Good choice,” Durand said. Toonce hopped on. Durand smiled at the master sergeant in the seat next to him, who tapped the jeep’s dash twice with the sort of gentle encouragement one might give a beloved horse. The vehicle advanced on its own at the gentle command.

They proceeded inside the compound under the watching guns of a pair of stork-legged Nigerian sentry turrets, each armed with a trio of four-barreled Gatling guns mounted on the mottled-grey fuselage pod.

Serge Martelle, the para master sergeant, handed Durand a palm-sized screen, a phone that used the local civilian networks.

“Seen this, sir?” Martelle asked.

A sigh. An image appeared of Alain’s face, jaw clenched and wide eyed, in the midst of a Paris protest. Again.

“No, not now, Martelle,” Durand said. A nod and he withdrew the screen. But Durand pulled up footage on his glasses, already tagged to his own and his son’s social media accounts. The final image was a bleary-eyed and red-faced Alain holding aloft the “PAX MACHINA.” It is Bastille Day after all, isn’t it. Durand smiled as they pulled up to a Kenyan general and his staff, standing at attention.

AU-UN HEADQUARTERS — DAR-ES-SALAAM, TANZANIA

“It’s not a mystery, as such, but we are not yet certain who is supplying the rogue Tanzanian army elements, as well as other local elements. But we can ascertain that they are currently involved in a rapid-equipping cycle using established and improvised fabrication sites that …”

“It’s Catalyst,” Durand barked. “Just call it out!” It was too easy to be rude to the UN Peacekeeping Office AIs; they were atrocious. Indecisive. Burdened with a politeness programmed to appease too many sensibilities. And that accent, unattached to any country’s native tongue, is an affront, he thought.

“Colonel Durand, analysis indicates a probability of certainty of—” the machine responded, now using a careful ethereal cadence to mollify Durand.

“General Kimani, with respect, how might we begin to engage an adversary that we refuse to identify?” Durand pressed the point. If the AU UN force acknowledged an “outbreak” of Catalyst coercive technologies, it would require an escalation of military presence that neither organization wanted to endorse at this point in the crisis.

“The last twenty-seven hours have seen no fighting,” Kimani responded. “We are hoping to use this window for dialogue.” He was the senior officer of the AUMIT, or African Union Mission in Tanzania. His charge included the military aspects of the peacekeeping mission, as well as coordinating with UN and quasi-governmental conflict-resolution groups trying to cool the conflict. “Right now, we’re running a Blue Zone dialogue with the dissident Tanzanian army, UN negotiators, Front Civil, and others. An invitation was extended to Catalyst, but no response.”

Durand nodded. Why would this highly disruptive and increasingly dangerous movement join in? It had no leaders. No clear strategy. He viewed French military intelligence’s take as sound: Catalyst sought to undermine US or Chinese economic, political, and military blocs of strategic influence to enable sub-national movements of self-determination.

The Blue Zones were private virtual environments managed by UN AIs to facilitate non-confrontational negotiations with machine-speed modelling and data. Some even talked of the platform’s AIs themselves being nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. If Kimani really believed the UN could speed that diplomatic cycle up before the rearming of the Tanzanian coup forces then there was a chance this could resolve without further violence. Durand knew him by reputation and instinctively trusted him. Then he ground his teeth. He was being too optimistic. But what were the odds some Catalyst algos weren’t already spoofing that whole thing? It happened before, in Venezuela, in ’38. They never joined these kinds of hand-holding sims.

His watch buzzed. Toonce reported the clearance codes were finally being transmitted and would be uploaded shortly. Having the NATO mech forces inside the base would make him feel better as they could be re-checked, zeroed, and synched with the UN and AU bots already in the area of operations. NATO-reinforced UN and AU patrols could begin the next morning, he hoped. Leave the conciliation and negotiation to the UN. He had his mission.

On his glasses, Durand cued up his task force’s status reports, and began watching the downloading of the clearance codes. Details mattered, even more so with machines. As a leader you had to stay on top of it. He focused on the data and half-listened as Kimani spoke for another minute. A Rwandan officer began discussing the Belgian food fab facility near the port about to be brought online.

Blasting horns brought conversation to an abrupt stop. Half of the attendees around the table jolted upright, standing and holding the conference table with white-knuckled grips as if bracing for a bodily impact. Durand remained seated and sighed. He locked eyes with Kimani, who shook his head. An attack with a warning was one you would survive, they both knew. It’s the strikes that come without any heads up that get you.

His glasses blinked, a scratching and pixelated green snow, then returned to showing the download progress of the clear codes. Stuck at seventy-six percent. Martelle was already on his notepad, ensuring the French paras inside the compound were ready for what came next. Of course they would be, he knew. That also gave him calm.

The door burst open and Toonce paused to catch her breath. She wiped dust from her mouth and began to speak.

“The clear codes were hijacked,” she said. “Catalyst payload rode the packets, but it’s not a Tanzanian Army attack. They got partially hit, too — at least their Chinese systems, from what I can tell already. One of the local groups it looks like, based on analytics. Took the task force bots and mechs down. Same with the AU and UN already deployed here. They’re trying to bring the whole country to a stop, they say, to start real negotiations.”

“How did they attack, exactly?”“They used the clear codes to target our bots’ firmware, forcing a factory reset that requires hard keys that only exist back with the civilians at the defense ministries. We, as the deployed German army, don’t even hold those. Same with the Italians. As for the Tanzanian army systems they got from the PLA, I don’t know anything for sure, but seem to be down, too.”

That might seem fortuitous, but Durand immediately looked at it another way: If Catalyst elements could wipe out the Tanzanian army’s reliance on Chinese platforms, that would be a blank slate for a new dependence on easily downloadable and fabbable Catalyst systems. Tanzania would probably acquire the Doktor anti-armor system, a simple self-firing short-barreled launcher that could be concealed in a backpack or mounted with suction-grips to a driverless vehicle, and maybe Viper launchers, a short-range 64-shot swarm weapon about the size of a concrete block that could be held and aimed by two handles or prepositioned to strike on its own.

Nearby explosions — one, two, three — rocked the room and knocked out the lights. Sounds like mortars. In the darkness, as Durand began to taste dust in the air, he conferred with Martelle about what to do next. His paras might be the only truly friendly combat-capable force in the area right now.

CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES — PARIS, FRANCE

Wringing out the handkerchief for a third time into the café’s brown-stained sink, Alain finally had the courage to look into the cracked mirror. Black splotches beneath the edges of the glass stained the edges of the reflective surface, framing a specter’s raw, red eyes peering back from an inky cloud.

“Oof,” he sighed. The neck of his black shirt was torn, by whom he could not remember. Claw-like scratches ran along his neck from his left ear down to his opposite clavicle. The blond girl who was shot in the legs? Or was it the CRS trooper who hit him with the mace?

A gentle knock on the door. “Everything Ok?”

That was his sister.

“A moment,” he said. He wiped his face with a coarse paper towel one more time, then put his augmented reality glasses back on. He tinted the lenses light blue. “I’m coming.”

Back out into the café, he rejoined his sister. A coffee waited, and he carefully touched its side with shaking fingers. Still warm. He closed his eyes and sipped the bitter espresso, grateful for the company of his sister and the tranquility of the café. Police drones raced by every few minutes, but no police were going to stop in here. They had other concerns right now responding to the attacks on the Champs-Élysées.

AU-UN HEADQUARTERS — DAR-ES-SALAAM, TANZANIA

Through thick black smoke, one of the tall two-legged defense turrets spun its gun mounts in lazy circles like a pinwheel. It did not fire as a swarm of bird-sized winged drones flew past in a corkscrew formation toward a far corner of the compound used for medevac flights. A series of blue strobe-like flashes followed by a sound like tearing paper meant that part of the camp would no longer be usable, Durand knew.

“Whose drones?” he asked aloud, looking around for Martelle.

“TA,” Martelle shouted, meaning “Tanzanian Army.” Normally, Martelle could look up with his glasses and get a read-out of the environment, seeing detailed information on everything from bandwidth to physical objects just as if he were going shopping. But since he had been on the base network during the attack, he saw nothing except fingerprint smudges and dust.

Yet after emerging from the bunker, the French officer knew where to find his soldiers. He sprinted at a low crouch toward a dispersed arrangement of vehicles set up in defensive positions. He greeted a soldier crouched near the rear flank of an AMX-3 armored vehicle. The paratrooper had set up a camoflage brown pop-up ballistic shield and was aiming a 10-year-old portable defense weapon skyward. These double-barreled shoulder-fired kinetic and microwave weapons were not connected to the base network or even the vehicles they were carried on, and so were still able to autonomously shoot down incoming shells and drones.

“Getting started a bit earlier than we wanted,” Durand said.

“Always ready, no?” said the soldier, whose chest armor name-plate read Orbach.

Durand held up the tablet he wore at his waist, and tapped it against the soldier’s forearm-mounted screen. Between the hastily broken up meeting and this physical connection, the mission-management AIs hosted on Durand’s tablet had created a plan of action based on years of training and real-world operations led by the colonel.

“There you go, Orbach. You have everything you need? Maybe I can fire up a fab for a nice coffee for you?”

Orbach smiled and nodded.

“Now get ready,” Durand said. “Let’s get out of this mess here and go start some trouble.”

Orders given, the information would spread rapidly from soldier to soldier, vehicle to vehicle, by direct or indirect laser transmission. Reliable, tightband, and perfect for a situation like this. Somebody might intercept it, but that was true with everything, wasn’t it?

At once, half the French paras moved to their vehicles, as the other half began climbing the shipping containers. Thanks to the task force’s own orbital sensors, unaffected by the attack so far, Durand had targets. Conventional doctrine emphasized machine vs. machine engagements, but he was going to be doing something far riskier. And more important: targeting the individuals who were the contacts, or nodes, for the Catalyst technologies. There was no time to waste staying inside the protection the base afforded. The Catalyst systems were learning and improving, from the first wave of attacks. Iterative warfare required ferocious speed and more initiative than most leaders were comfortable with.

A text message from Toonce appeared on Durand’s glasses. The UN base’s network was back up. Wait. Based on the auburn-colored text and the blue triangle icon, this was a message being sent via an encrypted consumer messaging app.

“I’m printing new logic cores for the defensive bots first, then the offensive systems. We have 213,” Toonce said.

“Of course,” Durand responded, a subvocal command converted to text. “How long?”

“Six hours.”

“And if you alternate printing, say, one defensive then one offensive, so there is … balance in our capability? I will not wait for the AU forces to regenerate. There is a window here we have to take before another round of upgrades by Tanzanian Army forces, or whoever else is equipping with Catalyst systems. We are moving out now.”

He closed out the conversation. Six hours would become 12, which would become a day delaying until the machines were ready. Durand’s paras were primed to fight now. La Victoire ne se donne pas.

Inside and atop the trucks and jeeps, the soldiers began cueing up virtual representations of their targets. The drivers took manual control, the safest option at a time like this. Less than a minute later, Durand and Martell were back in the scout car, with the commander buckling on his armor. The convoy rolled forward at a walking pace toward the base’s main gate. Some of the paras cast wary glances at the glitching Nigerian defense bots, which swayed back and forth atop their stork-like legs. Other soldiers looked for the two para sniper teams protectively watching from atop the shipping containers. As the vehicles advanced, the snipers flew a quartet of Aigle reconnaissance drones to scout routes established by Durand’s AIs.

The French soldiers were not the only ones rushing to action. Holding a water bottle in his lap, Martelle watched a squad of Kenyan infantry worked carefully to clear the medevac flight pad, guiding a pair of eight-legged explosive ordnance disposal bots as they cleared the area of micro-munitions left behind by the Catalyst swarm. The “confetti mines” were the size of an old postage stamp, paper-like explosives that detonated when their millimeters-thin bodies were bent or cracked. Coiled tight around titanium spools stored inside the bird-like drones, the mines fluttered to the ground by the hundreds, arming as they fell. One mine alone might not be enough to injure a person or even a machine. But if one detonated, it triggered other nearby mines.

“Martelle, hey,” Durand said.

“Sir,” Martelle responded, nodding. He took a drink of water.

“They have their job. We have ours.”

“Always ready. Onward,” Martelle said.

A tap on the pad at his waist and Durand urged the column forward. The base’s thick-plasticrete barrier-gates at its main entrance swung outward like arms extending for an embrace. Durand held his breath as his jeep was the first through, out into the open area beyond the base. With a feeling of regret, he passed intricate human-sized pyramids of dust-covered German and Italian bots, looking like cairns on a forgotten desert trail. It was as if in their final moments they sought to join together out of fear. He did not need those machines to complete this mission, but he would be lying to himself if he did not admit that they could make a life-or-death difference for his soldiers.

“Faster now,” said Durand. “We have our objectives, now we—”

His glasses vibrated painfully.

“MISSION ABORT,” read the message, a bright red scrawl of flashing characters.

This was no time to stop. He swiped it aside, and motioned for Martelle to keep driving.

Then General Kimani broke through with a direct audio feed.

“Colonel, you need to return to base. Mission abort. Confirm?”

There was no way to lock the officer out. Unlike with a fully autonomous formation, there was no “kill switch” for Durand’s troops. He led them, fully.

“We are en route to the objectives, general. You can see our target set; it has been approved by the task force command.”

The jeep slewed to the right, around a broken-down Tanzanian Army T-99X tank, a self-driving Chinese model that was exported throughout Africa, complete with stock PLA green-and-brown digital camo.

“No longer. PKO and AU leadership just made the call. They do not want your troops hunting down individuals in the city. Their models say it will just worsen the situation for civilians, everybody.”

Worsen? Durand thought. Isn’t it already bad enough?

“So,” said Durand. “That’s it?”

“I am going to propose another target set. Only bots, fabs, and cyber targets. No humans. We can deploy the task forces systems in six hours, I understand. Your paras can be on standby.”

Machines targeting machines, said Durand. That’s all they want any more.

He braced his leg and leaned back in his seat as his vehicle accelerated onto a deserted artery flanked by half a kilometer of torched and roofless four-story buildings. He looked back over his shoulder at the trailing convoy. His troops were there, following.

August Cole is co-author of Burn-In: A Novel of the Real Robotic Revolution

Read also How NATO is Innovating Toward the Future only in The Cipher Brief

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief.

Source link

قالب وردپرس

from World Wide News https://ift.tt/2T8NbG8

0 notes

Text

Building the “Great Collective Organism of the Mind” at The John Perry Barlow Symposium

Individuals from the furthest corners of cyberspace gathered Saturday to celebrate EFF co-founder, John Perry Barlow, and discuss his ideas, life, and leadership.

The John Perry Barlow Symposium, graciously hosted by the Internet Archive in San Francisco, brought together a collection of Barlow’s favorite thinkers and friends to discuss his ideas in fields as diverse as fighting mass surveillance, opposing censorship online, and copyright, in a bittersweet event that appropriately honored his legacy of Internet activism and defending freedom online.

Thanks to the magic of fair use, you can relive the Symposium any time by visiting the Internet Archive. Video begins at 48:00.

%3Ciframe%20src%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Farchive.org%2Fembed%2Fyoutube-Oaci9vlg_Sc%22%20webkitallowfullscreen%3D%22true%22%20mozallowfullscreen%3D%22true%22%20allowfullscreen%3D%22%22%20height%3D%22431%22%20frameborder%3D%220%22%20width%3D%22575%22%3E%3C%2Fiframe%3E

Privacy info. This embed will serve content from archive.org

After a touching opening from Anna Barlow, John Perry Barlow’s daughter, EFF Executive Director Cindy Cohn kicked off the speaker portion of the event:

“To me, what Barlow did for the Internet was to articulate, more and more beautifully than almost anyone, that this new network had the possibility of connecting all of us. He saw that the Internet would not be just a geeky hobby or toy like ham radios, or only a military or academic thing, which is what most folks who knew about it believed. Starting from the Deadheads who used it to gather, he saw it as a new lifeblood for humans who longed for connection, but had been separated.”

EFF Executive Director Cindy Cohn.

While the man himself may not have been present, Barlow’s connection—and influence—was palpable throughout the Symposium, with a dozen distinguished speakers and hundreds in attendance conversing, delivering remarks, and offering up questions about the past, the present, the future, and Barlow’s impact on all of it. The first speaker (and EFF’s co-founder along with Barlow), Mitch Kapor, told the audience: “I can feel his generous and optimistic spirit right here in the room today inspiring all of us.”

EFF co-founder Mitch Kapor with Pam Samuelson.

Barlow’s genius, said Kapor, was that in 1990, while most Internet usage was research- and military-based, he “absolutely nailed the Internet’s essential character and what was going to happen.”

Samuelson and Barlow speak with with Bruce Lehman, head of the USPTO in 1996.

Pam Samuelson, Distinguished Professor of Law and Information at the University of California, Berkeley, pointed out that Barlow’s 1994 treatise on copyright in the age of the Internet, The Economy of Ideas, has been cited a whopping 742 times in legal literature. But he didn’t just give lawyers an article to cite—Barlow helped the world understand that copyright had a civil liberty dimension and galvanized people to become copyright activists at a time when traditional notions of information access would be shaken to their core.

Freedom of the Press Foundation's Trevor Timm.

Trevor Timm described Barlow as “the guiding light” and “the organizational powerhouse” of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, which he co-founded with Barlow in 2012. On the day the organization launched, Timm recalled, Barlow wrote: “When a government becomes invisible, it becomes unaccountable. To expose its lies, errors, and illegal acts is not treason, it is a moral responsibility. Leaks become the lifeblood of the Republic.” His hope was that the organization would inspire a new generation of whistleblowers—and the next speaker, Edward Snowden, made clear he’d achieved this goal, telling the audience: “He raised a message, sounded an alarm, that I think we all heard. He did not save the world, none of us can—but maybe he started the movement that will.”

Whistleblower Edward Snowden talks about Barlow's impact.

The speakers answered questions on Facebook privacy, their disagreements with Barlow (of which there were many, ranging from the role of government overall to whether copyright was alive or dead), and what comes next in our understanding of the web. Cory Doctorow, EFF Special Advisor and emcee of the Symposium alongside Cindy Cohn, answered this in “Barlovian” fashion: “We could sit here and try to spin scenarios until the cows come home and not get anything done, or we can roll up our sleeves and do something.”

EFF’s former Executive Director (and current director of the Tor Project) Shari Steele began the second panel, discussing Barlow’s deeply-held belief in the First Amendment, insistence on hearing opposing viewpoints, and interest in bringing together diverse opinions: “That’s how he thrived...He was always encouraging people to talk to each other—to have conversations where you normally maybe wouldn’t have thought this was somebody you would have something in common with. He was fascinating, dynamic, and helped us create an Internet that has all sorts of fascinating and dynamic speech in it.”

Shari Steele, John Gilmore, and Joi Ito.

John Gilmore, EFF Co-founder and Board Member, invoked French philosopher and anthropologist Teilhard de Chardin, whose ideas Barlow specifically referenced in his writings. Barlow’s interest in mind-altering experiences, like taking LSD, said Gilmore, wasn’t just related to his love of the Internet: it came from the exact same place, an interest in creating the “great collective organism of mind” that Barlow hoped we might one day become.

Steven Levy, author and editor at large at Wired.

Author Stephen Levy, the writer of Hackers, thought that though Barlow may be well known as a writer of lyrics for the Grateful Dead, he will possibly be even better known by his words about the digital revolution. In his view, Barlow was a terrific writer and a master storyteller “capable of pulling off a quadruple-axle level of nonfiction difficulty.” His gift was to be able to not only “explain what was happening to the out-of-it Mr. Joneses of the world, but to encapsulate what was happening, to celebrate it, and to warn against its dangers in a way that would enlighten even the...people who knew the digital world—and to do it in a way that the reading was a pure pleasure.”

Joi Ito, Director of the MIT Media Lab.

Joi Ito, Director of the MIT Media Lab, described Barlow’s sense of humor and optimism—the same “you see when you talk to the Dalai Lama.” Today’s dark moments for the Internet aren’t the end, he said, and reminded everyone that Barlow had an elegant way of bringing these elements together with activism and resolve. His deep sense of humor came “from knowing how terrible the world is, but still being connected to true nature.” Ito also touched upon Barlow's groundbreaking essay A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace as a crucial "battle cry for us to rally around," taking the budding cyberpunk movement and helping it become a socio-political one.

The second panel fielded questions on encryption, Barlow’s uncanny ability to show up in the weirdest places, and how we can inspire the next generation of Barlows. Echoing EFF’s mission of bringing together lawyers, technologists, and activists, Joi Ito said that we will need engineers, lawyers, and social scientists to come together to redesign technology and change law, and also change society—and that one of Barlow’s amazing abilities was that he could talk to, and influence, all of these people.

Twenty-seven years later, EFF continues to work at the bleeding edge of technology to protect the rights of the users in issues as diverse as net neutrality, artificial intelligence, opposing censorship, and fighting mass surveillance.

Ameila Barlow reads from the 25 Principles for Adult Behavior.

Amelia Barlow, John Perry’s daughter, thanked the “vast web” of infinitely interesting and radical human beings around the world who he cared about and cared about him. “Never before have you been able to draw more immediately and completely upon him—and I want you to feel that,” she said, before reading his now-famous 25 Principles for Adult Behavior.

Anna Barlow reflects on her father's life.

As Anna Barlow said in her opening remarks, Barlow’s adventures didn’t stop in his later years—they just started coming to him. Some of the most brilliant thinkers in the world showed that this will remain true even while his physical presence is missed. Perhaps the Symposium was one step towards creating the “great collective organism of mind” that Barlow hoped to see us all become. And at the very least, Anna said, he doesn’t have to be bummed about missing parties anymore—because now he can go to all of them.

Cory Doctorow gives parting words on honoring Barlow.

Cory Doctorow closed the Symposium with a request:

“This week—sit down and have the conversation with someone who’s already primed to understand the importance of technology and its relationship to human flourishing and liberty. And then I want you to go varsity. And I want you to have that conversation with someone non-technical, someone who doesn’t understand how technology could be a force for good, but is maybe becoming keenly aware of how technology could be a force for wickedness.

And ensure that they are guarded against the security syllogism. Ensure that they understand too that we need not just to understand that technology can give us problems, but we must work for ways in which technology can solve our problems too.

And if you do those things you will honor the spirit of John Perry Barlow in a profound way that will carry on from this room and honor our friend who we lost so early, and who did so much for us.”

Join EFF

Donate in honor of John Perry Barlow

from Deeplinks https://ift.tt/2HgzHDx

0 notes