#Barnette v West Virginia

Photo

The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of WV found that it was unconstitutional to require students to salute the American flag on 10/6/1942.

File Unit: Barnette et al. versus West Virginia State Board of Education, Civil #242, 8/19/1942 - 12/4/1942

Series: Civil Case Files, 1938 - 2003

Record Group 21: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685 - 2009

Transcription:

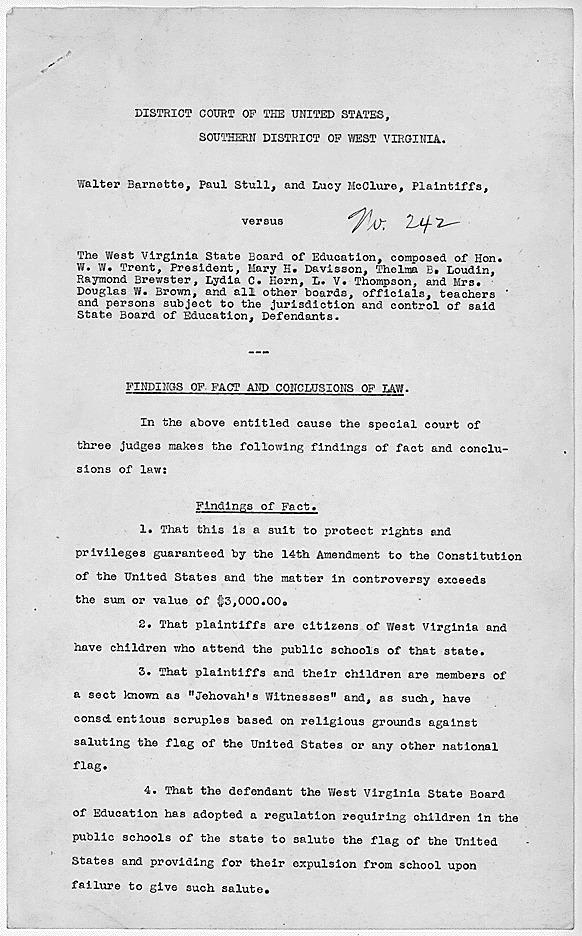

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES,

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF WEST VIRGINIA.

No. 242

Walter Barnette, Paul Stull, and Lucy McClure, Plaintiffs,

versus

The West Virginia State Board of Education, composed of Hon. W. W. Trent, President, Mary H. Davisson, Thelma B. Loudin, Raymond Brewster, Lydia C. Hern, L. V. Thompson, and Mrs. Douglas W. Brown, and all other boards, officials, teachers and persons subject to the jurisdiction and control of said State Board of Education, Defendants.

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW.

In the above entitled cause the special court of three judges makes the following findings of fact and conclusions of law:

Findings of Fact.

1. That this is a suit to protect rights and privileges guaranteed by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States and the matter in controversy exceeds the sum or value of $3,000.00.

2. That plaintiffs are citizens of West Virginia and have children who attend the public schools of that state.

3. That plaintiffs and their children are members of a sect known as "Jehovah's Witnesses" and, as such, have conscientious scruples based on religious grounds against saluting the flag of the United States or any other national flag.

4. That the defendant the West Virginia State Board of Education has adopted a regulation requiring children in the public schools of the state to salute the flag of the United States and providing for their expulsion from school upon failure to give such salute.

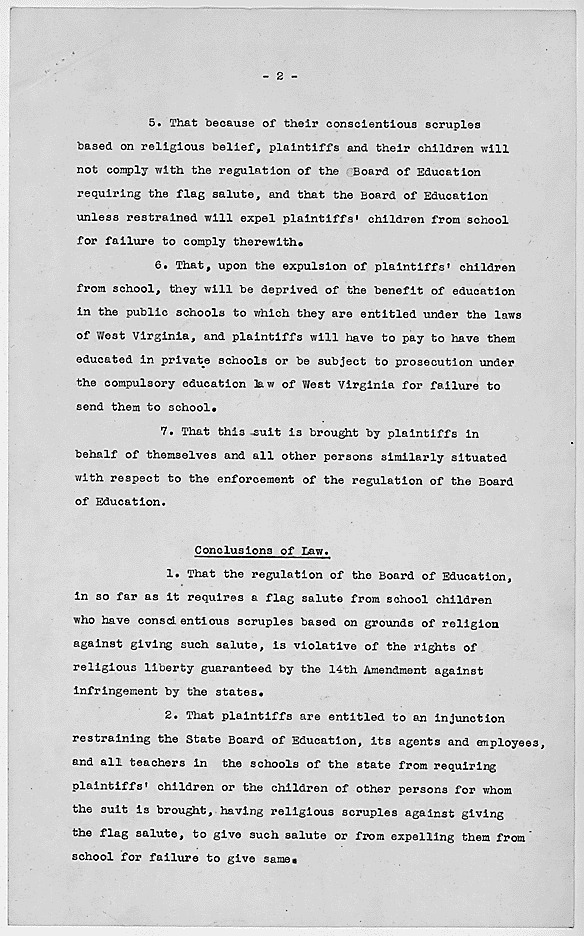

[page 2]

-2-

5. That because of their conscientious scruples based on religious belief, plaintiffs and their children will not comply with the regulation of the Board of Education requiring the flag salute, and that the Board of Education unless restrained will expel plaintiffs' children from school for failure to comply therewith.

6. That, upon the expulsion of plaintiffs' children from school, they will be deprived of the benefit of education in the public schools to which they are entitled under the laws of West Virginia, and plaintiffs will have to pay to have them educated in private schools or be subject to prosecution under the compulsory education law of West Virginia for failure to send them to school.

7. That this suit is brought by plaintiffs in behalf of themselves and all other persons similarly situated with respect to the enforcement of the regulation of the Board of Education.

Conclusions of Law.

1. That the regulation of the Board of Education, in so far as it requires a flag salute from school children who have conscientious scruples based on grounds of religion against giving such salute, is violative of the rights of religious liberty guaranteed by the 14th Amendment against infringement by the states.

2. That plaintiffs are entitled to an injunction restraining the State Board of Education, its agents and employees, and all teachers in the schools of the state from requiring plaintiffs' children or the children of other persona for whom the suit is brought, having religious scruples against giving the flag salute, to give such salute or from expelling them from school for failure to give same.

[page 3]

-3-

Enter: Oct. 6, 1942

John J. Parker

U.S. Circuit Judge, Fourth Circuit.

Harry E. Watkins

U.S. District Judge for the Northern and Southern Districts of West Virginia.

Ben Mooney

U.S. District Judge, Southern District of West Virginia.

#archivesgov#October 6#1942#1940s#court case#U.S. District Court#14th Amendment#saluting the flag#American flag#Barnette v West Virginia#Jehovah's Witnesses

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

i knew of so many teachers in middle school who would threaten students with write ups or zero grades if they didnt stand for/do the pledge and only today did i find out that thats literally illegal. west virginia state boe v. barnette

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The First and Fourteenth Amendments and Discrimination

In the wake of the Supreme Court's decision in 303 Creative v. Elenis, the so-called "gay website case," I have seen a ton of just terrible takes arguing what the law does and does not say about discrimination and what the Supreme Court has said.

The simplest version is, the Supreme Court ruled that, if you are engaged in expressly creative services, the state cannot compel you to make a message with which you disagree. The Court did not say that one can broadly discriminate against protected classes in general services.

The 14th Amendment says, "No State shall... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." Here, "state" also means any government entity, smaller or larger than the state.

Through successive civil rights acts, the Supreme Court and various Federal and State legislatures have clarified that this means that "places of public accommodation" cannot deny services based on someone's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Public accommodations, under these laws, generally means facilities or business, publicly or privately owned, which are generally opened to the public. If you offer a service or a good to the people at large, in a brick and mortar facility or exclusively online, you cannot deny standard services to people because of their race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. In some places, sexual orientation and gender identity have been added to this list.

If you sell something to the public, you have to sell it to black people or women, even if you hate those groups. However, none of these rules prohibit you from denying services to people for basically any other reason.

Except in a few locations, such as Washington DC, and Madison, Wisconsin, political belief and viewpoint discrimination is completely legal. A business has always been allowed to deny services to someone for being a Republican or a Democrat or a Communist or a Nazi. Business are even allowed to fire employees for their political beliefs and expressions in most cases, as happened when a Berkeley, California hot dog business fired an employee for marching in the "United The Right" rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

The First Amendment says, "Congress shall make no law... abridging the freedom of speech." The Supreme Court has also ruled, repeatedly, that "freedom of speech" means "freedom of expression, so the "speech" need not be spoken, but any sort of creative expression one wishes to engage in.

In West Virginia State Board of Education v Barnette (1943), the Supreme Court ruled that the state, in the form of the local public school, could not force a student to say the pledge of allegiance. Writing for the court, Justice Robert Jackson said: "If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein."

Just like you have the freedom to speak and say what you'd like, you also have the right to be free from the government ordering you to express yourself in ways you find repugnant.

In 303 Creative v Elenis, (2023), a web designer, Laurie Smith, sued the State of Colorado to prevent them from enforcing a rule which would have required her to serve gay people. Sexual Orientation, in the state of Colorado, is a protected class. According to the public accommodation and protected class rules discussed above, this should be pretty clear, that Smith must provide service to the [hypothetical] gay couple that wanted her to build a wedding website. What she argued, however, was that if the state forced her to engage in the "inherently creative" expression of web design. The court agreed that for specific cases, where the public accommodation engaged in inherently creative services, the state could not compel someone through threat of criminal liability, to engage in that speech.

The court did NOT overrule the entirety of the Civil Rights architecture in the United States. No business can now decide they do not have to sell or serve protected classes if they don't want to. If you sell cheeseburgers, you are not now cleared to not sell those cheeseburgers to black people or gay people. Subway "sandwich artists" are not "inherently creative" in a way that would allow them to deny their service to protected classes either, as the service itself must be creative and providing the message to which one objects. There is nothing about the selling of an even spectacularly creative sandwich to a gay couple would not convey any meaning.

Nor does this decision mean suddenly you can engage in viewpoint discrimination against non-protected classes. You always could and, unless something changes radically, always will be able to. If you want to deny me service or refuse to sell me a bottle of water because I have a shirt with a message you disagree with, you are allowed to do that.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Roberts is actually right about something for once.

In support of its holding, the Court cites three seminal constitutional decisions that involved overruling prior precedents: Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), West Virginia Bd. of Ed. v. Barnette, 319 U. S. 624 (1943), and West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, 300 U. S. 379 (1937). See ante, at 40–41. The opinion in Brown was unanimous and eleven pages long; this one is neither. Barnette was decided only three years after the decision it overruled, three Justices having had second thoughts. And West Coast Hotel was issued against a backdrop of unprecedented economic despair that focused attention on the fundamental flaws of existing precedent. It also was part of a sea change in this Court’s interpretation of the Constitution, “signal[ing] the demise of an entire line of important precedents,” ante, at 40—a feature the Court expressly disclaims in today’s decision, see ante, at 32, 66. None of these leading cases, in short, provides a template for what the Court does today.

- ROBERTS, C. J., concurring in judgment.

Even a broken clock is right twice a day.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evaluating Significant Decisions from the 2022-2023 Supreme Court Term

By Jacob Caskie, Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania Class of 2023

August 9, 2023

The United States Supreme Court reviews only a few dozen legal cases every year, however, the significance of these cases is often immense. In the 2022-2023 Supreme Court term, the Justices reviewed fifty-two cases in total, and issued rulings on cases involving free speech, religious accommodations, University admissions, and true threats. The Supreme Court’s 2022-2023 term concluded on June 28th, 2023, and the court is now in recess until October. Due to the importance of several rulings made during this term, it seems fitting to evaluate some of the decisions made by the court and analyze their significance. Each case analysis will be separated, and will include a review of the case background, arguments made by the petitioners and respondents, and finally, the holding issued by the Supreme Court.

[1] 303 Creative LLC et al. v. Elenis et al. 600 U.S. ___ (2023)

Lorie Smith owns a graphic design business, 303 Creative LLC, in Colorado and wanted to expand her business to include website design for couples seeking wedding websites. She worried, however, that the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act (CADA) would compel her to create websites that celebrate marriages between individuals of the same sex, which she does not endorse due to her religious beliefs. CADA prohibits “all public accommodations” from denying “the full and equal enjoyment” of its services to any customer based on his race, creed, sexual orientation, or other statutorily enumerated trait. Either state officials or private citizens may seek enforcement action for the statute. Ms. Smith filed a lawsuit with a Colorado District Court seeking an injunction that would prevent the state from forcing her to create websites celebrating marriages that defy her religious belief: That marriage should be reserved for the unification of a man and a woman. Before the District Court, Ms. Smith stated that she is willing to work with people regardless of their sexual orientation and will create graphics for them without protest. She added that she will not, however, produce content that “contradicts biblical truth” regardless of who orders it. Ms. Smith stated that her view of marriage is a sincerely held conviction, and that her services “express 303 Creative’s message celebrating and promoting her view of marriage” as she is the sole employee. The State of Colorado rebutted that Ms. Smith’s case does not implicate pure speech, but rather the sale of an ordinary product that should be available to not some, but all, and that any burden on her speech is purely “incidental”. The state also insisted that Supreme Court precedent from Rumsfeld v. FAIR, 547 U.S. supports their argument.

The District Court held that Ms. Smith was not entitled to the injunction in which she sought, and the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed. A divided panel cited that the state had shown a compelling government interest in forcing Ms. Smith to create speech, and that no reasonable alternative existed, satisfying the criteria for strict scrutiny. The Supreme Court granted certiorari and reviewed the Tenth Circuit’s disposition.

The Supreme Court began by reviewing several cases that were argued on similar grounds as Ms. Smith’s. In West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette 319 U.S. 624, 642, The Supreme Court held that West Virginia’s efforts to compel schoolchildren to salute the American Flag during the Pledge of Allegiance “invaded the sphere of intellect and spirit, which it is the purpose of the First Amendment… to reserve from all official control.” In Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston, Inc., 515 U.S. 557, the court held that a Massachusetts public accommodations statute was not able to compel veterans organizing a parade to include a group of homosexual individuals because the parade itself was protected speech and requiring them to include a group they wished to exclude would “alter the expressive content of their parade”. Finally, in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale 530 U.S. 640, 660-661, the court held that the Scouts’ decision to exclude a homosexual man from participation was entitled to First Amendment protection, because the Boy Scouts are an “expressive association”. The Supreme Court stated these cases illustrate that the First Amendment protects an individual’s right to speak his mind regardless of the government’s belief on intention or sensibility.

The Supreme Court agreed with the Tenth Circuit in many aspects, including that the websites Ms. Smith seeks to create qualify as pure speech, which is protected by The First Amendment. The Supreme Court further recognized that Colorado sought to compel Ms. Smith to speak in ways that align with its beliefs but defy her own conscience, and since The First Amendment “envisions the United States as a place where people are free to think and speak as they wish,” the court ruled that Colorado cannot compel Ms. Smith to create websites for marriages she does not endorse.

[2] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 600 U.S.___ (2023)

Harvard College and the University of North Carolina (UNC) are two of the oldest and most prestigious educational institutions in the United States, and while thousands of students apply to these institutions annually, only a small percentage are accepted to attend. Admission to these institutions is dependent on many variables including, but not limited to, the applicants’ academic prestige, extracurricular involvement, recommendation letters, and even their race. Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), a nonprofit organization that seeks to “defend human civil rights secured by law” filed two separate lawsuits against Harvard and UNC, arguing that the race-based admissions used by these institutions violate Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Equal Protections Clause of The Fourteenth Amendment. The respondents’ claim that SFFA lacks standing due to their lack of membership organizational status was rejected by the court.

Separate bench trials found that both admissions programs were lawful under the Equal Protections Clause and Supreme Court precedent. The Supreme Court granted certiorari for the Harvard case after the First Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed judgment, and for the UNC case prior to an issued judgment.

The Supreme Court began by reviewing the admissions processes used by both institutions. At Harvard, each application is screened by a “first reader” who assigns a numerical score to applicants in six different categories, including one titled “overall”. Overall is a compilation score of the preceding categories, where the reader can, and does take applicant race into consideration. Harvard’s subcommittees then review applications by geographic area, and make recommendations to the admissions committee, who also takes race into account. When deliberations begin, applicants are grouped by race to prevent “a dramatic drop-off” in minority admissions. Applicants who receive a majority of the committee’s votes are tentatively accepted for admission, and at the conclusion of voting, the racial composition of the acceptance pool is disclosed to the committee. Then begins the “lop” process, where the tentatively accepted applicants are winnowed, and race is again a deciding factor. UNC’s admission process is like that of Harvard’s. Applications are first read by an admissions office reader who assigns a numerical score to multiple categories and is required to consider applicant race. The reader then makes a recommendation, which can be aided by the applicant’s race. A “school group review” is then conducted where this recommendation is either approved or rejected. In making these final decisions, the race of the applicant can be a deciding factor.

The justices then turned their focus to the Fourteenth Amendment and the Equal Protections Clause. Prior decisions of the court had interpreted the Equal Protections Clause as a guarantee that “all persons, whether colored or white, shall stand equal before the laws of the states.” Exceptions to this standard must withstand strict scrutiny. Further, citing Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, the court stated the decision of this case was clear in ruling that education “must be made available to all on equal terms.” Although the court recognized that precedent allows race-based admissions decisions at universities, they also acknowledged the attached limitations: That the programs must comply with strict scrutiny, applicant race may not be used negatively, and that there must be a “logical end point.”

After review of both admissions systems, the court determined that the universities had fallen short of the burden to operate their programs in a manner that is “sufficiently measurable to permit judicial review.” Citing the respondents’ goals for race consideration, the court found immeasurable how the specific ethnic mix of a student body can further produce these goals. The court’s opinion also asserts that the admissions processes fail to create a connection between their methodology, and their goals, specifically noting that the racial classifications the institutions use are overbroad, arbitrary, and underinclusive. Secondly, the universities’ admissions systems fail to comply with the Equal Protections Clause, which states that race may not be used as a negative, nor a stereotype. The First Circuit Court found that Harvard’s consideration of race resulted in reduced admissions for specifically Asian students, and the Supreme Court found that by considering race, the universities were engaging in the stereotype that “students of a particular race, because of their race, think alike.” Finally, the court reasoned that the universities’ race-based admissions lack an end point, which was required by the decision of Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 326. Respondents’ argued that they will end their race considering programs when their goals have been met, or once meaningful representation occurs, which the court had found immeasurable.

Due to the respondents’ lack of measurable objectives requiring race consideration, use of applicant race in a negative manner, use of stereotyping, and lack of a logical end to race consideration, the Supreme Court found the admissions programs impermissible under the Equal Protections Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

[3] Counterman v. Colorado 600 U.S.___ (2023)

Billy Counterman sent hundreds of Facebook messages to a local singer named “C.W.” from 2014 to 2016. The two had never met, and C.W. made repeated attempts to block Counterman from contacting her through the platform. Each time, Counterman created a new Facebook account and continued sending her messages, several of which pictured harm befalling her. C.W. claims this activity put her in fear and halted her daily activities, which ultimately caused her to notify law enforcement. The state of Colorado charged Counterman under a statute that prohibits making any form of repeated communication in “a manner that would cause a reasonable person to suffer serious emotional distress and does cause that person . . . to suffer serious emotional distress." Counterman moved to dismiss these charges on First Amendment grounds, claiming that his messages were not “true threats” and because of this, cannot be the basis for criminal prosecution.

The trial court rejected this argument following Colorado law, which uses a “reasonable person” standard and found that Counterman’s statements were indeed true threats. Counterman was convicted by a jury and appealed, arguing that the state is required to show his subjective intent to threaten C.W. The Colorado Court of Appeals affirmed his conviction, relying on its precedent, and the Colorado Supreme Court denied review. The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari due to division amongst the lower courts regarding the requirement for proof of subjective mindset in true-threats cases.

First, The Supreme Court reviewed the First Amendment’s restrictions upon the content of speech, including incitement to unlawful conduct, defamation of another, obscenity, and true threats of violence. True threats are classified as “serious expressions” conveying that the speaker intends to “commit acts of unlawful violence.” The existence of this threat is dependent on the conveyance of the statement, yet the court found that the First Amendment still may require the showing of a subjective mental-state of the speaker. Since prohibitions on speech have the potential to deter an individual from creating speech, requiring the state to show proof of a “culpable mental state” or a mens rea can be a tool to prevent this. The court reasoned that such showings are required to punish other areas of unprotected speech. Defamation, while serving no value to this nation, cannot be recovered from unless it can be shown that the speaker made a false statement “with knowledge that it was false, or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” Incitement to unlawful conduct can often incur consequences even if the speaker did not intend to convey violent messages, but the First Amendment still protects that individual from prosecution unless it can be shown that his words were intended to produce unlawful actions. Similarly, obscenity requires proof of the defendant’s mindset, as neglecting scienter would inadvertently affect protected speech. Ultimately, the court ruled that utilizing an “objective ‘reasonable person’ standard” would discourage speech that the First Amendment seeks to protect.

The Justices then sought to determine the appropriate mens rea for prosecuting true-threats, and found that in this context, a recklessness standard stood sufficient. A person acts recklessly when he “consciously disregards a substantial, and justifiable risk that his conduct will cause harm to another.” The court reasoned that this standard offers wiggle room for protected speech without impeding too many aspects of criminal prosecution for true-threats. While other areas of unprotected speech may require a stronger showing of intent, the court found that is not necessary in cases of true-threats.

The Supreme Court ruled that Counterman was prosecuted, and convicted under an objective standard that is based on the interpretation of a “reasonable person.” The state was not required to show that Counterman was aware of the threatening nature of his statements, and thus, his conviction violates the First Amendment. The Supreme Court vacated judgment of the Colorado Court of Appeals and remanded the case for further proceedings that require a showing of at least recklessness.

[4] Groff v. DeJoy, Postmaster General 600 U.S. ___ (2023)

Gerald Groff is an Evangelical Christian who believes for religious reasons that Sundays should be reserved for rest and worship, not work-related duties. Groff was hired to work for the United States Postal Service (USPS) in 2014, and his duties did not typically include working on Sunday. After his employer agreed to start handling Sunday deliveries for Amazon, this changed, and a memorandum was signed by USPS that mandated Sunday duties upon request. Groff requested and was granted transfer to a rural delivery hub in Holtwood, Pennsylvania, who did not make Sunday deliveries. In 2017 however, Amazon deliveries also began at this hub. Groff continued refusing Sunday work, and USPS was forced to hand off his deliveries to his peers. Groff received “progressive discipline” for his refusals, and ultimately resigned in January 2019. Subsequently, Groff sued USPS under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, claiming that the service could have accommodated his religious practice “without undue hardship on the conduct of their business.”

The District Court granted summary judgment to USPS, and the Third Circuit Court affirmed, feeling bound to their holding in Trans World Airlines Inc. v. Hardison, 432 U.S. 63, which ruled that requiring an employer to bear more than “de minimis cost” to provide a religious accommodation is an undue hardship. The Third Circuit found that Groff’s refusal to work “imposed on his coworkers, disrupted workflow, and diminished employee morale.” The Supreme Court granted Groff’s petition for a writ of certiorari.

The court first reviewed Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which made it unlawful for employers to “refuse to hire or terminate any individual, or otherwise discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment because of religion.” The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission interpreted this as meaning that employers are sometimes required to make accommodations to the religious needs of employees, so long as it does not present “undue hardship” to the business. In 1972, Congress amended Title VII, providing that “religion” includes all aspects of religious observance and belief, and that employers must abide by these guidelines unless they can reasonably show that they are unable to do so without “undue hardship” on the conduct of their business.

Switching their focus, the court reviewed the decision of Hardison, the basis of the de minimis cost standard. Similarly to Groff, Hardison was hired to work for Trans World Airlines (TWA) in 1967, and he underwent a religious conversion that would entail absenting from work on Saturday’s. This conflicted with his work schedule and attempts at accommodation still presented a substantial burden on the business. His refusal to work concluded with his discharge on ground of insubordination. Hardison sued both his workers union, and TWA, and the Supreme Court granted certiorari. The decision of this case focused little on constitutional issue, rather, it placed prominence on the seniority rights of employee’s, which is also provided by Title VII. Ultimately, the court ruled in Hardison that requiring TWA to bear more than “de minimis cost” (i.e., something so small or trifling that the law will not recognize it) to accommodate religious needs is an undue hardship, and that since there was no alternative solution without revoking the seniority rights of others, they were not required to accommodate.

The Supreme Court, applying aspects of Hardison to their review of Groff, concluded that TWA’s undue hardship defense in Hardison continually referenced proffered accommodations as “substantial burdens.” Therefore, the court reasoned that an “undue hardship” is presented when a burden is “substantial in the overall context of an employer’s business” rather than “more than a de minimis cost.” Further, the court asserted that Title VII requires that employers reasonably accommodate an employee’s practice of religion, not that it simply assesses the reasonableness of said accommodations. Specifically, the majority found that USPS had not considered the totality of the accommodations it was able to provide to Groff.

The Supreme Court held that the Third Circuit court utilizing a “more than de minimis cost” test may have led them to neglect numerous possible accommodations. Since this test was discovered to be flawed by the justices, the judgment of the Third Circuit Court was vacated, and Groff’s case was remanded for further proceedings.

______________________________________________________________

[1] 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, 600 U.S. ___ (2023)

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/us-supreme-court/21-476.html

[2] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 600 U. S. ___ (2023)

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/us-supreme-court/20-1199.html

[3] Counterman v. Colorado, 600 U. S. ___ (2023)

[4] Groff v. DeJoy, 600 U. S. ___ (2023)

0 notes

Text

Those who begin coercive elimination of dissent soon find themselves exterminating dissenters. Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.

--Robert Jackson (1942, West Virginia v. Barnette)

0 notes

Text

The Utilization of Lyrics as Evidence

By Theodros Fekade, University of Miami Class of 2024

June 22, 2023

With the judgment in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, the judiciary proves that it is not willing to enforce or conduct a standard of uniformity amongst citizens or encourage groupthink. (West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette) In Brandenburg v. Ohio, the Supreme Court used a two-pronged speech test where speech can be deemed illegal if the speech is "directed at inciting or producing imminent lawless action" and is "likely to incite or produce such action.” (Brandenburg v. Ohio) The Brandenburg v. Ohio case perfectly displays the extent to which the First Amendment is willing to cover and protect. Analogously, the founding fathers envisioned a country where you could say anything you wished through “Congress shall make no law prohibiting the free exercise of abridging the freedom of speech.” (Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute) The First Amendment has been raised in the West Virginia v. Barnette and Brandenburg v. Ohio cases as a way of protecting free speech, but free speech and the First Amendment cover a broader scope that encompasses artistic freedom. Many countries across the world significantly destroy art or persecute graffiti artists, musicians, and painters for engaging in art that oversteps the general limitations that the government sets forth. (Pecot) Fortunately, in the realm of American jurisprudence, the judicial branch makes a considerable effort to combat this by assuring the protected rights of artists through rulings in their favor and by issuing practical limitations on alterations proffered by legislatures. In American jurisprudence, substantive and procedural laws are prevalent in civil and criminal cases. Substantive law is associated with the specific definitions of the law and their implications for society. Procedural law refers to the proceedings of the case and how they are conducted to institute equitable due process. While society tends to be adamant over substantive issues, it should be infuriated over procedural law implications because one cannot expect any substantive law to be impartial when the procedural law is inherently corrupt. As hip-hop lyrics are being cultivated as evidence in court rooms, we are witnessing a society where procedural law is arguably contradicting the First Amendment. Legal scholars, professors, and proponents assert that the use of hip-hop lyrics in court is explicitly dismantling the First Amendment, stripping the First Amendment of its authority, and infringing on the freedom within the precious society of the United States.

Arguably, the scope of the First Amendment should never shrink because our society will only progress with the introduction of artificial intelligence technologies, Web3, and the metaverse. Our society will inquire about the methods by which people should limit their free speech regarding emerging technological innovations. The Supreme Court must inculcate society with a determined and objective standard to prevent the collapse of society, which is an original tenet of the U.S. Constitution. In Miller v. California, the Supreme Court’s now famous test was employed to determine something obscene by the complete and subsuming satisfaction of "(a) whether 'the average person, applying contemporary community standards," would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest; (b) whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and finally (c) whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value." (Miller v. California) Although Miller v. California has been used in a multitude of cases to benefit an artist, there have also been nefarious and sinister ways that prosecutors, government officials, and authority figures have overtly employed to implement hip-hop lyrics in court as a mechanism of evidence. In American jurisprudence, society tends to be shocked or gasp when they hear a summary judgment or verdict in a case. Society, using that dumfounded or appalled feeling, should be perturbed by the process of gaining the summary judgment or verdict in the case. Society should be baffled by the proceedings of the case, which can involve everything from pretrial discovery to jury selection. The pretrial discovery in a case itself can allow evidence that can prove invaluable in the minds of a jury or judge to render a verdict.

In Atlanta, Jeffery Williams (nicknamed Young Thug), Sergio Kitchens (nicknamed Gunna), and other members of the YSL Enterprise were indicted on the R.I.C.O. (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization) Act. Through Young Thug’s lyrics of "I never killed anybody, but I got something to do with that body," the prosecutors built their case upon these lyrics as their smoking gun evidence. (Lang) Gunna, who was only indicted due to a speeding ticket, was included in the indictment due to his lyrics, "YSL slimy and shady, they ain't wavy like my clique." This indictment sets a dangerous precedent because rappers will be in constant fear of reprisals from prosecutors. Analogously, the fear of reprisals and the limitations on lyrics will discharge the alluring effect of hip-hop’s nature. Johnny Cash once made a song named "Folsom Prison Blues" that had the lyrics "but I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die." (Genius) The result of Johnny Cash singing the Folsom Prison Blues resulted in no indictment whatsoever and critical acclaim that amassed him 15 Grammy awards. (Pecot) Although the employment of lyrics in court is erratic, perhaps the most egregious use of lyrics in court belongs to the case involving Vonte Skinner. In New Jersey v. Skinner, Vonte Skinner was charged and convicted of attempted murder and other charges because a state witness was allowed to read hip-hop lyrics that were finally used as evidence against Vonte Skinner. (New Jersey v. Skinner) The prosecutor in the case ended up applying 13 pages of violent lyrics that did not include the victim or material aspects related to the crime Skinner was accused of. (Kubrin and Nielson) The Supreme Court, in their reasoning, ruled that the evidence of the lyrics constituted "highly prejudicial evidence against Skinner" and that the hip-hop lyrics could be used to besmirch the jury’s judgment. (New Jersey v. Skinner) Although iniquitous prosecutors believe in exploiting the lyrics as an "I caught them red-handed" moment, the Supreme Court does not agree and will reverse the decisions of inferior courts that deem such lyrics material to the case.

One of the most prevalent arguments for utilizing rap lyrics in court is to combat crime. When one uses this argument, one must first understand who the lyrics are used against, how material the lyrics are to a case, and how often the lyrics are used as evidence. In the overwhelming majority of cases involving the use of lyrics as evidence, there tends to be a focus on the artistic genre of hip-hop. When Bob Marley sang of how "he shot the sheriff" or how Edgar Allan Poe composed of how he "buried a man beneath his floorboards," no reasonable prosecutor sought charges against these artists. (Manly) When lyrics that are emotionally jarring are used as sole or prolific evidence throughout the entirety of the case, the jury can only be "poisoned" and clouded in their judgment of the defendant. (Pecot) The Supreme Court agrees while also determining that the rap lyrics themselves are inherently protected by the First Amendment as the lyrics are considered artistic expression.

______________________________________________________________

Brandenburg v. Ohio. U.S. Supreme Court. 9 June 1969.

Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. 1992. <https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/first_amendment>.

Genius. Genius. 15 December 1955. <https://genius.com/Johnny-cash-folsom-prison-blues-lyrics>.

Kubrin, Charis E and Erik Nielson. Rap Lyrics on Trial. 13 January 2014. <https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/14/opinion/rap-lyrics-on-trial.html>.

Lang, Cady. What to Know About Young Thug’s Trial and the Controversial Use of Rap Lyrics in Criminal Cases. 29 June 2022. <https://time.com/6192371/young-thug-rap-lyrics-evidence-court/>.

Manly, Lorne. New Jersey High Court Rules Lyrics Inadmissible in Rapper’s Case. 4 August 2014. <https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/05/arts/music/new-jersey-high-court-rules-lyrics-inadmissible-in-rappers-case.html>.

Miller v. California. U.S. Supreme Court. 21 June 1973.

New Jersey v. Skinner. No. A-5365-14T2. Superior Court of New Jersey. 29 November 2017.

Pecot, Emily. Using Rap Lyrics as Evidence in Court. 15 February 2023. <https://njsbf.org/2023/02/15/using-rap-lyrics-as-evidence-in-court/>.

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette. U.S. Supreme Court. 14 June 1943.

0 notes

Text

Pledge of Allegiance? via /r/atheism

Pledge of Allegiance?

During the Cold War, the two words “under God” was added to the US Pledge of Allegiance to combat the USSR’s state atheism. First, let me say how ridiculous it is to bring religion into geopolitics and to portray atheism as evil. The Soviet Union was a shithole because of Marxist dogma and an oppressive government, not the lack of belief in a god. If the United States really has a western secular government, how come our state motto is religious? People are worried about inclusiveness but atheists are forgotten about.

When looking at the constitution, two things come to mind: the “Free Exercise” clause of the First Amendment and the “Equal Protection” clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Pledge of Allegiance’s “under God” phrase is basically saying that Americans live in a nation that is under a single god. What about atheists and people who believe in multiple gods? Wouldn’t that be denying other’s faiths? This definitely goes against the free exercise of religion. And for those who think America is a “Christian nation,” I suggest you do research on the Enlightenment. There’s also the Equal Protection clause. If the pledge followed that there would be no reference to a god as to equally represent all US citizens.

Now, you don’t have to stand for the Pledge of Allegiance. Take a look at West Virginia v. Barnette. Regardless, if we want a true secular state, it should be changed.

Submitted July 14, 2022 at 11:02PM by WolfCanyon_

(From Reddit https://ift.tt/zSGWXR6)

0 notes

Text

freedom to differ is not limited to things that do not matter much. That would be a mere shadow of freedom. The test of its substance is the right to differ as to things that touch the heart of the existing order.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Complaint in Barnette v. West Virginia Board of Ed (selected pages), 8/19/1942.

The plaintiffs objected to students’ being required to salute the flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance. The Supreme Court ruled that it is unconstitutional to compel students to do either.

File Unit: Barnette et al. versus West Virginia State Board of Education, Civil #242, 8/19/1942 - 12/4/1942

Series: Civil Case Files, 1938 - 2003

Record Group 21: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685 - 2009

Transcription:

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF WEST VIRGINIA

Charleston Division

WALTER BARNETTE,

PAUL STULL, and

LUCY McCLURE,

Plaintiffs,

v.

THE WEST VIRGINIA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, composed of HONORABLE W. W. TRENT, President, MARY H. DAVISSON, THELMA B. LOUDIN, RAYMOND BREWSTER, LYDIA C. HERN, W. R. VINEYARD, and MRS. DOUGLAS W. BROWN, and all other boards, officials, teachers and persons subject to the jurisdiction and control of STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Defendants.

[handwritten] No. 242 [end handwritten]

COMPLAINT

To SAID HONORABLE COURT:

Now come the above named plaintiffs and complain of the above named defendants, and for a cause of action would show:

1. JURISDICTION is based upon existence of a "federal question" irrespective of the amount of money involved, in that this [handwritten open parenthesis] action arises under the Constitution and laws of the United States and involves purely and solely "civil rights" under and by virtue of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 and Section 24 (14) of the Judicial Code [28 U.S.C. 41 (14)], [handwritten close parenthesis] because this is an action brought to redress the deprivation of "civil rights" by persons acting under color of statutes and regulations of a state. The Court also has jurisdiction by virtue of Section 24 (1) of the Judicial Code [28 U.S.C. 41 (1)], in that the cause of action arises under the Constitution and laws of the United States and that as to each person for whom this action is brought the matter in contro-

[page 2]

flag means, in effect, to participate in a religious "rite" or ceremony and that the one saluting the flag ascribes salvation and protection to the thing or power which the flag stands for and represents, and that since the flag and the government it symbolizes are of the world and not of JEHOVAH GOD, it is wrong only for one in a covenant with JEHOVAH, such as each plaintiff and his children, to salute the flag, and for him to do so constitutes his denial of the supremacy of Almighty God, and contravenes God's express command set forth in Holy Write, which results in everlasting destruction by JEHOVAH of such person's right to life.

6. That plaintiffs and all other of Jehovah's witnesses for whom this action is brought at all times endeavored to instruct and inform their children of the truths including the above commandments set forth in the Word of God, the Bible. They desire to educate their children and bring them up as upright and sincere followers of Jesus Christ, all as it is their right, privilege and duty to do; that said children have been so instructed from an early age and are now and have been at all times material hereto sincere believers in God's commandments written in the Bible and have faithfully endeavored to obey such.

7. Plaintiffs are loyal to the United States and the State of West Virginia and willingly obey its laws, but they nevertheless believe that their first and highest duty is to their God and His commandments and law, and that as true followers of the Lord Jesus Christ they have no alternative except to obey God's commandments and to follow their conscientious convictions. They are willing, in lieu of participating in said flag-salute ceremony, periodically and publicly to subscribe to the following pledge, to wit:

"I have pledged my unqualified allegiance and devotion to Jehovah, the Almighty God, and to His Kingdom, for

4

[page 3]

pealed by the enactment of said Federal statute. In the event that the Court concludes that said State statutes and regulations have not been entirely annulled and repealed by the passage of said Federal statute, the plaintiffs say that the prescribed flag-salute ceremony for public schools of said State are void because expressly contrary to said Federal statute, which provides that only persons [underline] in uniform [/end underline] (of the United States Army and Navy) are required to give the military salute or engage in the flag-salute ceremony required by said State statutes and regulations thereunder promulgated by defendant-board. Furthermore, said Federal statute does not require a civilian, adult or child, to give any salute whatsoever to the national flag, and specifically does not require the giving of the salute or participation in the ceremony prescribed by the defendant-board. All that may be lawfully required of any civilian, adult or child, is merely "standing at attention", even though a child be in attendance at a public school in said State. That by reason of the foregoing the said State statutes and regulations thereunder promulgated by said defendant-board are void because in conflict with the United States Constitution and the above Federal statute.

26. That the application and enforcement of said State statutes and flag-salute regulations or any of them, against pupils who conscientiously object to participation in such ceremonial, do not instil love of liberty and democratic principles and devotion to country in the minds of the youth. The giving of the salute does not prove loyalty to the nation because any disloyal person can salute the flag so as to hide his disloyalty. The natural tendency of compelling a conscientious objector to give the salute is to hinder and obstruct loyalty to country because of attempted coercion and oppression of conscience. The enforce-

13

[page 4]

ment of said statutes and regulations in such manner diminishes respect and increases disrespect for flag and country by inspiring acts of lawlessness and violence against persons who lawfully elect to render obesiance and obedience exclusively to Almighty God, and it provides a means to conceal for every adherent of and conniver with the "fifth column" his true identity. See, in further corroboration of the above matters the booklet "God and the State", copy of which is attached hereto and made a part hereof, marked APPENDIX.

27. That the refusal of children of Jehovah's witnesses to salute the American flag or otherwise participate in the unlawfully and illegally required flag-salute ceremony does not present a clear and present danger against peaceful, lawful, proper and regular operation of any public school in said State, nor does such refusal present a clear and present danger against the peace of the law-abiding teachers and pupils of any such school. That there is no clear and present danger that any other pupils will refuse to salute the flag unless they become Jehovah's witnesses, which is most unlikely because of the extreme unpopularity of and persecution now prevailing against Jehovah's witnesses as result of persistent misrepresentation regarding their loyalty to [underlined] the government. [end underline]

28. That there is nothing in the faith or practices based upon the faith of persons for whom this action is brought that can be claimed to be contrary to morals, health, safety or welfare of the public, the State or the nation.

29. That because constitutionality and validity of State statutes of West Virginia are drawn in question, and because plaintiffs are asking for a preliminary injunction restraining the enforcement of said statutes, plaintiffs are entitled under Section 266 of the Judicial Code (28 U. S. C., Section 380, as

14

#archivesgov#August 19#1942#1940s#SCOTUS#Supreme Court#First Amendment rights#religion#Jehovah's Witnesses#American flag#flag salute#Pledge of Allegiance#Barnette v West Virginia

33 notes

·

View notes

Link

As stated in recent U.S. Supreme Court documents: "Barronelle Stutzman is a Christian artist who imagines, designs and creates floral art. ... She cannot take part in or create custom art that celebrates sacred ceremonies that violate her faith."

This legal drama appears to have ended with Stutzman's second trip to the high court, and its July 2 refusal to review a Washington Supreme Court decision that drew a red line between a citizen's right to hold religious beliefs and the right to freely exercise these beliefs in public life. Supreme Court justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch backed a review, but lacked a fourth vote.

"This was shocking" to religious conservatives "because Barronelle seemed to have so many favorable facts on her side," said Andrew Walker, who teaches ethics at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.

Stutzman is a 76-year-old grandmother and great-grandmother who faces the loss of her small business and her retirement savings. She has employed gay staff members. She helped Ingersoll find another designer for his wedding flowers. In the progressive Northwest, her Southern Baptist faith clearly makes her part of a religious minority.

"Barronelle is a heretic because she has clashed with today's version of progressivism," Walker said. Many cultures have "blasphemy laws" and Stutzman has "been found guilty ... Her beliefs, and her insistence that she should live according to those beliefs, clash with the beliefs of the current zeitgeist."

Part of the confusion is that this court's refusal to hear Stutzman's case appears to clash with its recent 9-0 Fulton v. City of Philadelphia decision. It protected the right of Catholic Social Services leaders to follow church teachings and, thus, to refuse to refer children to same-sex couples for adoption or foster care.

Responding to that decision, Roger Severino of the Ethics & Public Policy Center in Washington wrote: "By its actions, the Court is saying people with sincere faith-informed understandings of social issues that cut against the grain of secularist thought aren't to be treated as bigots."

That was then. The subsequent decision to "punt" on the Stutzman case, said Walker, was another example of this Supreme Court delaying a clear decision on First Amendment concerns caused by clashes between ancient faiths and the Sexual Revolution.

These concerns will continue to haunt the court, in part because of church-state precedents such as this famous language from the 1943 West Virginia v. Barnette decision, which said the government could not force Jehovah's Witnesses to recite the Pledge of Allegiance.

"If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation," wrote Justice Robert Jackson, "it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein."

#SCOTUS#First Amendment#Robert Ingersoll#Barronelle Stutzman#gay marriage#Christians#religious freedom#Arkansas Democrat Gazette#Terry Mattingly#Fulton v. City of Philadelphia#Roger Severino#West Virginia v. Barnette#Andrew Walker#Baptists#secularism

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tinker V. Des Moines Case Summary

Hello, BOTUS readers! Our first case we will be discussing the infamous Tinker V. Des Moines case. Here is a summary for those who are new or familiar to the case. Stay tuned for our opinion piece by one of our writers!

BACKGROUND: 1965 America was divided of troops aiding in the Vietnam war.

THE CASE: In Des Moines, Iowa 15-year John Tinker, his sister Marybeth Tinker and Hope Tinker, his brother Paul Tinker, and friend Christopher Eckhardt carried out an act of protest by wearing black armbands.

To which the school district banned the armbands and threated the students with suspension and expulsion if they did not comply. Then John, Marybeth, and Christopher wore them anyways and got suspended and could not come back unless they stopped wearing the armbands. And to push the school more they came back to school in January of 1966 wearing all black clothing.

The Tinker family was who were civil rights and antiwar activist, with the help of the ACLU took the school district to the U.S. district court for southern Iowa, which ruled in favor of the policy.

The thing to remember is that the district court agreed that a student had the right to protest under the first amendment, the court’s decision was made because the concern was a school would have a hard time keeping an orderly environment where student could learn.

The case was then brought to the appeals court for the 8th circuit which ended up in a tie, causing the Tinker family to make one last appeal to the supreme court who heard arguments on November 12, 1968.

Attorney Dan Johnston, who took the case for the Tinkers argued that the school district’s policy was unconstitutional and violated 1st amendment rights.

He also argued that since the 1943 case west Virginia board of education vs. Barnett protected student’s rights to symbolic expression (with the pledge of allegiance and the flag); the same should be applied to the tinkers.

OUTCOME: 1969 supreme court ruled that a public-school forbidding student from wearing black armbands to protest the Vietnam war was against the first amendment rights of students.

The supreme court eventually came to a decision (7-2) on February 24, 1969 with Judge Abe Fortas for the majority, where he said students and teachers do not leave their rights at the schoolhouse door. And argued that the armbands symbolized pure speech that was separate from any actions of those wearing them.

Created the “tinker test” which is a way to see if a student’s speech is disruptive at school. Also weakened the legal idea that the school takes the place of a parent while the student is in attendance.

Sources: https://youtu.be/27M3BO69ZCs , https://youtu.be/qOk7sjqKmhI , https://youtu.be/HQ_EAbM3zxo

Thanks for tuning in!

-your pal, Marlon

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Half of Americans say Bible should influence U.S. laws, including 28% who favor it over the will of the people

Pew Research Center has conducted a new study on whether the Bible should have an influence on the U.S laws. The results of the survey demonstrated that 50% of Americans believe that the Bible should have some to a great deal of influence on U.S laws. Among Christians, 68% would want to see at least some influence of the Bible, and among Protestants that number increases to 89%. The other 50% disagree, believing that the Bible should have little to no influence over laws. Groups that oppose the Bible’s influence over legislature are unaffiliated at 78% and Jews at 68%. Breaking down the surveyors by the demographic groups, one can observe that majority of people who are for the Bible were older people (50+) and belong to the Republican party. On the other hand, opposition mostly consists of Democrats between the ages of 18 to 29. In addition to whether the Bible should impact US laws, I found it interesting and unsurprising that 68% of white Evangelicals believe that the Bible should take precedence over the will of people during the times of conflict.

One of the things I noticed when I was looking at the results of the survey is that it has a bias. The two major groups that influenced the results of this survey are Christians and Unaffiliated. Which is why I believe the results were split 50 – 50. For example, the survey has completely excluded the Muslim group during their poll. While we learned that Muslims make up only about 1% of the US population, it is still important to include them in the survey because many of them are US citizens who have a right to vote on something as important as “establishing religion” in a country. In addition, we know that Muslims tend to be on a lower end of the socio-economic spectrum and therefore vote Democratic. As seen by the outcome of the survey, most Democrats voted against having Bible influence U.S laws, so assuming pollsters included Muslim groups the results would be more swayed toward no influence. Also, one may assume that Muslims may also be opposed to having Bible influence over the laws as they follow Quran teachings.

I believe that the Bible should have no influence over U.S laws. However, it would be interesting to see what direction people who do believe in it are going to take it. Using the Bible to write laws is the same as establishing religion. There have been multiple Supreme Court cases regarding the establishment of religion. In West Virginia v Barnette, the court ruled that saying Pledge of Allegiance is voluntary. In Engel v Vitale prayer was prohibited in public schools. Abington School District v. Schempp has extended the ban to Bible readings and recitation of Lords Prayer. Since these cases have established that practicing religion in public places should be prohibited, I think allowing the Bible to have an influence on U. S laws will indirectly violate those rulings. In addition, using the Bible to sway laws will be unfair to other religions or non-believers as it will be against their beliefs.

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/04/13/half-of-americans-say-bible-should-influence-u-s-laws-including-28-who-favor-it-over-the-will-of-the-people/

1 note

·

View note

Text

A child in a US school cannot be forced to recite the Pledge of Allegiance

Despite what you frequently see alleged on this site, children in US public schools cannot be compelled to pledge allegiance to the flag or to the United States. Indeed, the US Supreme Court ruled over 75 years ago in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943) that such a requirement would violate the First and Fourteenth Amendments and thus be unlawful.

The Court delivered some fairly clear and meaningful explanations for why this could not be required and on the importance of freedom:

“The Fourteenth Amendment, as now applied to the States, protects the citizen against the State itself and all of its creatures – Boards of Education not excepted. These have, of course, important, delicate, and highly discretionary functions, but none that they may not perform within the limits of the Bill of Rights. That they are educating the young for citizenship is reason for scrupulous protection of Constitutional freedoms of the individual, if we are not to strangle the free mind at its source and teach youth to discount important principles of our government as mere platitudes.”

“If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”

The willingness of individuals to violate the laws and freedoms of another should not be mistaken for those protections not existing. If someone attempts to violate your rights, please do protest and resist. However, that should not be taken as a sign that these rights and freedoms do not exist.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gonzalez V. Google Questions The Liability Of Social Media Platforms With Respect To Terrorism

By Morgan Polen, University of Pittsburgh Class of 2025

October 28, 2022

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA) has unquestionably been one of the most consequential pieces of legislation ever passed with respect to technological platforms and the Internet. It states that “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider” [5]. In layperson’s terms, the platform/website per se cannot be held liable for the speech and/or content of one of its users. For example, if someone goes on Twitter and posts a defamatory statement, the target of said statement can sue the defamator but not Twitter. It’s also worth noting that Section 230 does not apply to intellectual property-rooted claims and criminal claims [5].

This provision of the CDA is especially crucial in an era where much controversy regarding the discretion of big tech looms over the world of jurisprudence. The issue in the case at hand involves Nohemi Gonzalez, one of the many victims claimed by the terrorist attacks inflicted by ISIS in Paris in 2015. Gonzalez’s family sued Google, owner of YouTube, under the Antiterrorism Act for “promoting” a wave of violent videos and breeding an environment conducive to ISIS members and supporters [2] [4]. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit argued that Section 230 protects the algorithms that are employed to promote such content. The majority did conclude that Congress, not the courts, should be the entity determining Section 230’s reach. However, the ruling produced multiple dissents, which is why it seems an opportune time for the Supreme Court to entertain this case, especially since it hasn’t ruled on Section 230 since its enactment in 1996 [6].

This case comes at a time where many issues regarding the future of technological volition are coming to fruition. For instance, Florida has recently petitioned the Supreme Court to rule on its contentious law, SB7072, which, if upheld, would prevent big tech platforms from censoring select content and people (Moody v. NetChoice, LLC). An analogous issue is posited NetChoice v. Paxton, where the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit upheld Texas’s House Bill 20, which greatly restricts the power of social media platforms to moderate its users; additionally, it imposes certain transparency requirements, which mandates that such platforms clearly state why they chose to take certain content down. The Fifth Circuit ruled that this law did not violate First Amendment provisions because it stifles censorship, not speech [3].

Nevertheless, it’s been widely understood that the First Amendment similarly protects one’s right to stay silent (West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 1943). Does it not then follow that big tech platforms have a right to “stay silent” and thus choose not to comment on its censorship choices?

Gonzalez is hardly an isolated incident. There’s a copious amount of First Amendment-related legislation swirling around, many issues often at-odds with one another. In a society where the freedom of expression is a hallmark, it’s necessary to remember that speech goes, for the most part, unbridled. Underlying Gonzalez is a case of particular salience: Brandenburg v. Ohio, which notedly overturned Schenck v. United States. Brandenburg (1969) clarified that speech is unprotected under the First Amendment only if it produces “imminent lawless action” or if it's “likely to incite or produce such action” [1]. When do the Internet and social media platforms become legally responsible for their users' tangible threats? Only making things cloudier is the fact that one cannot censor speech on the premise that it *might* have the ability to incite violence in the future. In other words, speech cannot be restricted before the fact. For matters involving the extent to which speech influences acts of terrorism, it’s onerous to disentangle the First Amendment from the Antiterrorism Act. Although Gonzalez was originally brought under the Antiterrorism Act, it ostensibly seems that such a First Amendment issue will be raised when SCOTUS reviews it.

Any case handling the First Amendment must be conducted with extreme care, for it only takes one ruling to send us down a vulnerable path of censorship and persecution. The Supreme Court will hear Gonzalez this term.

______________________________________________________________

[1] Brandenburg v. Ohio. (n.d.). Oyez. Retrieved from www.oyez.org/cases/1968/492.

[2] Howe, A. (2022, October 3). Court agrees to hear nine new cases, including challenge to tech companies’ immunity under Section 230. Scotusblog. Retrieved from www.scotusblog.com/2022/10/court-agrees-to-hear-nine-new-cases-including-challenge-to-tech-companies-immunity-under-section-230/.

[3] Jurecic, Q. (2022, September 16). Fifth Circuit upholds Texas social media law. Lawfare Blog. Retrieved from www.lawfareblog.com/fifth-circuit-upholds-texas-social-media-law#:~:text=On%20Sept.,and%20imposes%20certain%20transparency%20requirements.

[4] Millheiser, I. (2022, October 6). A new Supreme Court case could fundamentally change the internet. Vox. Retrieved from www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2022/10/6/23389028/supreme-court-section-230-google-gonzalez-youtube-twitter-facebook-harry-styles.

[5] Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. (n.d.). Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved from www.eff.org/issues/cda230.

[6] Willard, L., Xenakis, N., Cooper-Ponte, A., & Salinas, M. (2022, October 5). Supreme Court grants certiorari in Gonzalez v. Google, marking first time court will review Section 230.

Inside Privacy.Retrieved from

www.insideprivacy.com/uncategorized/supreme-court-grants-certiorari-in-gonzalez-v-google-marking-first-time-court-will-review-section-230-2/

0 notes

Quote

As first and moderate methods to attain unity have failed, those bent on its accomplishment must resort to an ever-increasing severity. As governmental pressure toward unity becomes greater, so strife becomes more bitter as to whose unity it shall be. Ultimate futility of such attempts to compel coherence is the lesson of every such effort from the Roman drive to stamp out Christianity as a disturber of its pagan unity, the Inquisition as a means to religious and dynastic unity, the Siberian exiles as a means to Russian unity, down to the fast failing efforts of our present totalitarian enemies. Those who begin coercive elimination of dissent soon find themselves exterminating dissenters. Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), opinion by Justice Robert H. Jackson

2 notes

·

View notes