#Ben Taub

Text

The Secret Life and Anonymous Death of the Most Prolific War-Crimes Investigator in History

When Mustafa Died, in the Earthquakes in Türkiye, his Work in Syria had Assisted in the Prosecutions of Numerous Figures in Bashar al-Assad’s Regime.

— By Ben Taub | September 14, 2023

Photo Illustration By Cristiana Couceiro; Source Photograph From Getty Images

It Was 4:17 A.M. on February 6th in Antakya, an Ancient Turkish City Near the Syrian Border, when the earth tore open and people’s beds began to shake. On the third floor of an apartment in the Ekinci neighborhood, Anwar Saadeddin, a former brigadier general in the Syrian Army, awoke to the sounds of glass breaking, cupboard doors banging, and jars of tahini and cured eggplant spilling onto the floor. He climbed out of bed, but, for almost thirty seconds, he was unable to keep his footing; the building was moving side to side. When the earthquake subsided, he tried to call his daughter Rula, who lived down the road, but the cellular network was down.

Thirty seconds after the first quake, the building started moving again, this time up and down, with such violence that an exterior wall sheared open, and rain started pouring in. The noise was tremendous—concrete splitting, rebar bending, plates shattering, neighbors screaming. When the shaking stopped, about a minute later, Saadeddin, who is in his late sixties, and his wife walked down three flights of stairs, dressed in pajamas and sandals, and went out into the cold.

“All of Antakya was black—there was no electricity anywhere,” Saadeddin recalled. Thousands of the city’s buildings had collapsed. Survivors spilled into the streets, crowding rubble-strewn alleyways and searching for open ground, as minarets toppled and glass shards fluttered down from tower blocks. The general and his wife set off in the direction of the building where Rula lived, with her husband, Mustafa, and their four children.

A third quake shook the ground. When Saadeddin made it to his daughter’s apartment block, flashes of lighting illuminated what was now a fourteen-story grave. The building—which had been completed less than two years earlier—had twisted as it toppled over, crushing many of the residents. Saadeddin felt his body drained of all emotion, almost as if it didn’t belong to him.

Saadeddin was not the only person searching for Rula and her family. For the past decade, her husband, Mustafa, had quietly served as the deputy chief of Syria investigations for the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, a group that has captured more than a million pages of documents from Syrian military and intelligence facilities. Using these files, lawyers at the cija have prepared some of the most comprehensive war-crimes cases since the Nuremberg trials, targeting senior Syrian regime officers—including the President, Bashar al-Assad. After the earthquake, the group directed its investigative focus into a search-and-rescue operation for members of its own Syrian team, many of whom had been displaced to southern Turkey after more than a decade of war. By the end of the third day, nearly everyone was accounted for. Two investigators had lost children; one of them had also lost his wife. But Mustafa was still missing.

For as long as Mustafa had been working for the cija, the group had kept his identity secret—even after it captured a Syrian intelligence document that showed that the regime knew about his investigative work and was actively hunting him down. “He was probably my best investigator,” Mustafa’s supervisor, an Australian who goes by Mick, told me, during a recent visit to the Turkish-Syrian border. Documents that Mustafa obtained, and witness interviews that he conducted, have assisted judicial proceedings in the United States, France, Belgium, Germany, and several other European jurisdictions. According to a cija estimate, Mustafa “either directly obtained or supported in the acquisition” of more than two hundred thousand pages of internal Syrian regime documents, likely making him—by sheer volume of evidence collected—the most prolific war-crimes investigator in history.

Twelve years into the Syrian war, at least half the population has been displaced, often multiple times, under varied circumstances of individual tragedy. No one knows the actual death toll—not even to the nearest hundred thousand. And yet the Syrian regime’s crimes continue apace. “The prisons are full,” Bill Wiley, the cija’s founder and executive director, told me. “All the offenses that started being carried out at scale in 2011 are still being perpetrated. Unlawful detention, physical abuse amounting to torture, extrajudicial killing, sexual offenses—all of that continues. War crimes on the battlefield, particularly in the context of aerial operations. There are still chemical attacks. It all continues. But, as long as there’s the drip, drip, drip of Western prosecutions, pursuant to universal jurisdiction, it’s really difficult to envision the normalization of the regime.”

Before the Syrian Revolution, Mustafa was a trial lawyer, living and working in Al-Rastan, a suburb of the central city of Homs. He and his wife, Rula, had three small children, and Rula was pregnant with the fourth. In early 2011, when Syrians took to the streets to protest against the regime—which had ruled for almost half a century—Assad declared that anyone who did not contribute to “burying sedition” was “a part of it.” Suddenly Mustafa was caught in a delicate position, since many of Rula’s male relatives were military officers.

Her father and her uncles had joined the Syrian armed forces as young men, and served Assad’s father for many years before they served him. In the mid-nineties, Assad’s older brother died in a car crash, and he was called back from his studies in London and sent to a military academy in Homs. Eventually, he joined a staff officers’ course, where Anwar Saadeddin—then a colonel and a military engineer—says he spent a year and a half in his class.

Assad became President in 2000, after his father died, and for the next decade Saadeddin carried on with his duties without complaint. In 2003, Saadeddin was promoted to the rank of brigadier general. At the outset of the revolution, his younger son was a lieutenant, and he was two years from retirement.

Mustafa and Rula’s fourth child was born on April 5, 2011. Three days later, security forces shot a number of protesters in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs, including a disabled man, who was unable to run away. They dragged him from the site and returned his mutilated corpse to his family the following evening. From then on, Homs was the site of some of the largest anti-regime protests—and the most violent crackdown.

On April 19th, thousands of people gathered for a sit-in beneath a clock tower. At about midnight, officers warned that anyone who didn’t leave voluntarily would be removed by force. A couple of hours passed; a thousand people remained. At dawn, the people of Homs awoke to traces of a massacre. A witness later reported that religious leaders who had stayed to treat the wounded and to tend to the dead were summarily executed. Several others recalled that the bodies were removed with dump trucks, and that the blood of the dead and wounded was washed away with hoses.

The day after the massacre, according to documents that were later captured from Assad’s highest-level security committee, the regime decided to embark on a “new phase” in the crackdown, to “demonstrate the power and capacity of the state.” Nine days later, regime forces killed at least nineteen protesters in Al-Rastan, where Mustafa and Rula lived. Mustafa wasn’t involved in politics or human-rights work, beyond discussions of basic democratic reforms, but he was appalled by the overtly criminal manner in which security forces and associated militias carried out their campaign with impunity. Locals formed neighborhood-protection units, and soon took up arms against the state.

A few months later, Mustafa briefly sneaked out of Syria to attend a training session in Turkey, led by Bill Wiley, a Canadian war-crimes investigator who had previously worked for various tribunals and the International Criminal Court. Wiley, and others in his world, had noticed a jurisdictional gap in accountability for Syria and had begun casting about for Syrian lawyers who might be up for a perilous, but worthy, task. Although there was no tribunal set up for Syria, and Russia and China had blocked efforts to refer Syria to the I.C.C., Wiley and his associates had reasoned that the process of collecting evidence is purely a matter of risk tolerance and logistics. The work of criminal investigators is different from that of human-rights N.G.O.s: groups like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch produce and disseminate reports on horrific violations and abuse, but Wiley trained Mustafa and the other Syrians in attendance to collect the kind of evidence that could allow prosecutors to assign individual criminal responsibility to senior military and intelligence officers. A video showing tanks firing on unarmed protesters might influence public opinion, but a pile of military communications that proved which commanders were in charge of the operation could one day land someone in jail.

“The first task was to ferret out primary-source material—documents, in particular, generated by the regime,” Wiley told me. “We were looking for prima-facie evidence, not intelligence product or information to inform the public.”

Mustafa instantly grasped the urgency of the project. By day, he carried on with his law practice. But, in secret, he started building up sources within the armed opposition. As they captured new territory, he would go into security and intelligence facilities, box up documents, and move them to secret locations, like farmhouses or caves, farther from the confrontation lines.

“By 2012, we had already started to get some structure,” Wiley recalled. He secured funding from Western governments, and eventually the group settled on a name: the Commission for International Justice and Accountability. “We had our guys in Raqqa, Idlib, Aleppo, and so forth—at least one guy in all the key areas,” he said. From there, the cija built out each team—between two and four individuals, working under the head of each provincial cell. “And Mustafa was our core guy in Homs.”

Anwar Saadeddin soon found himself wielding his position in order to rescue relatives who were caught up in the conflict. His younger son, an Army lieutenant, was detained by military operatives on the outskirts of Damascus, after another officer in his brigade reported him for watching Al Arabiya and Al Jazeera. According to an internal military communication, which was later captured by the cija, Assad believed that foreign reporting on Syria amounted to “psychological warfare aimed at creating a state of internal chaos.”

When Saadeddin’s son was detained, he recalled, “I interfered just to decrease the detention period to thirty days.” Soon afterward, he learned that Mustafa was a target of military intelligence in Homs, where the local facility, Branch 261, was headed by one of Saadeddin’s friends: Mohammed Zamrini.

Mustafa wasn’t calling for an armed rebellion, and, at the time, neither the regime nor his father-in-law knew of his connection to Wiley and the cija. But rebel factions were active in Al-Rastan, and Mustafa was known to have urged them not to destroy any public establishments. To hard-liners in the regime, such interaction was considered tantamount to collaboration. “So I went with Mustafa to the branch,” Saadeddin told me. Zamrini agreed to detain him as a formality—for about twelve hours, with light interrogations and no torture or abuse—so that he could essentially cross Mustafa off the list.

In the next few months, the security situation rapidly deteriorated. The Army encircled rebellious neighborhoods near Homs and shelled them to the ground. Saadeddin’s son, who was serving near Damascus, was arrested a second time, and in order to get him released Saadeddin had to supplicate himself in the office of Assef Shawkat, Assad’s brother-in-law and the deputy minister of defense. In Homs, Saadeddin started driving Mustafa to and from work in his light-blue Kia; as a brigadier general, he could move passengers through checkpoints without them being searched or arrested.

But Saadeddin was beginning to find his position untenable. He sensed that the regime’s policy of total violence would lead to the destruction of the country. That spring, he began to share his fears and frustrations with close colleagues and friends, including the commander of his son’s brigade. But it was a perilous game: Assad’s highest-level security committee had instructed the heads of regional security branches to hunt down “security agents who are irresolute or unenthusiastic” in carrying out their duties. According to a U.N. inquiry, some officers were detained and tortured for having “attempted to spare civilians” on whom they had been ordered to fire.

That spring, Saadeddin’s car was stopped at one of the checkpoints that ordinarily waved him through. It was the first time that his position served not as protection against interrogation but as a reason to question his loyalty. The regime was quickly losing territory, and as the conflict spiralled out of control many senior officers found themselves approaching the limits of their willingness to go along. He and his brothers had “reached a point where we would either stand by the regime and have to take part in atrocities, or we would have to defect,” he told me.

That July, Saadeddin gathered his brothers, his sons, two nephews, and several other military officers in front of a small camera, somewhere near the Turkish-Syrian border. Dressed in his uniform, he announced that the army to which he had pledged his allegiance some four decades earlier had “deviated from its mission” and turned on its citizens instead. To honor the Syrian public’s “steadfastness in the face of barbaric assaults by Assad’s bloody gangs, we have decided to defect from the Army,” he said. It was one of the largest mass defections of Syrian officers, and his plan was to take a leading role in the rebellion—to fight for freedom “until martyrdom or victory.” In response, Saadeddin told me, their former colleagues sent troops to destroy their houses and those of their family members. They expropriated their land and killed several of their relatives.

By now, the regime had ceded swaths of Syria’s border with Turkey to various rebel forces. Saadeddin moved his family across the border and into a refugee camp that the Turkish government had set up for military and intelligence officers who defected. Then he went back to Syria, to try to bring some order and unity to the rebel factions that were battling his former colleagues.

But Mustafa and his family stayed behind in Al-Rastan, which was now firmly in rebel hands. The regime’s loss of control at the Turkish border meant that the cija could start moving its captured documents out of the country.

“It was complicated, reaching the border, because the confrontation lines were so fluid,” Wiley recalled. “And there were multiple bodies who were overtly hostile to cija”—not only the regime but also a growing number of extremist groups who were suspicious of anyone working for a Western N.G.O. During the first document extraction, a courier was shot and injured. During the next, another courier vanished with a suitcase full of documents. “Just fucking disappeared,” Wiley said. “Probably thought he could sell them.” Mustafa recruited a cousin to transport some files to Turkey. But, after the delivery, on the way back to Al-Rastan, the cousin took a minibus, and the vehicle was ambushed by regime troops. “He was shot, but it was unclear if he was wounded or dead when they took him away,” another Syrian cija investigator, whom I’ll call Omar, told me. For the next several weeks, regime agents blackmailed Mustafa, saying that for twenty thousand dollars they would release his cousin from custody. But, when Mustafa asked for proof of life, they failed to provide it—suggesting that the cousin had already died in custody.

By now, Wiley had issued new orders for the extraction process. “I said, ‘O.K., there needs to be a plan, and I need to know what the plan is,’ ” he recalled. “ ‘How are you getting from A to B? What risks are there between point A and point B? And how are you going to ameliorate those risks?’ As opposed to just throwing the shit in the car and going, ‘Well, God decides.’ ”

Saadeddin Spent Much of the next eighteen months trying to organize disparate rebel groups into a unified command. He travelled all over northern Syria, as rebels took new ground, and met with all manner of revolutionaries—from secular defectors to hard-line field commanders. By the summer of 2013, the regime had ceded control of most of northern Syria. But there was little cohesion between the rebel factions, and isis and Al Qaeda had come to exploit the power vacuum in rebel territory. At some point, Saadeddin recalled, he scolded a Tunisian isis commander for arousing sectarian and ethnic tensions, and imposing extremism onto local communities. “He responded that I was an apostate, and suggested that I should be killed,” Saadeddin told me.

In Al-Rastan, a regime shell penetrated the walls of Mustafa’s house, but it didn’t explode. At that point, Rula and the children moved to Reyhanli, a small Turkish village that is so close to the border that you can eat at a kebab shop there while watching sheep graze in Syria. It was also a short drive from the defected officers’ camp, where Rula’s mother and several other relatives were living. But Mustafa stayed behind, to carry out his investigative work for the cija.

“When new areas were liberated, the security branches were raided, and many people took files,” Omar recalled. Some of them didn’t grasp the significance of the files; at least one soldier burned them for warmth. “But most people knew the documents would be useful, someday—they just didn’t know what to do with them. So they just kept them. And the challenge was in identifying who had what, where.”

But, before long, Omar continued, “Mustafa built a wide network of contacts in rebel territory. Word got out that he was collecting documents, and so eventually people would refer others who had taken documents to him.” Sometimes he encountered a reluctance to turn over the originals, until he shared with them the outlines of the cija’s objective and paths to accountability. “At that point, they would usually relent, understanding that his use for them was the best use.”

As his profile in rebel territory grew, Mustafa remained highly secretive. But, from time to time, he asked his father-in-law for introductions to other defected military and intelligence officers. By now, Saadeddin recalled, “I knew the nature of his work, but I didn’t discuss it with him.” There was an understanding that it was best to compartmentalize any sensitive information, for the sake of the family. “Sometimes my wife didn’t even know what I was doing,” Saadeddin said. “But I do know that, at a certain point, through his interviews, Mustafa came to know these defected officers even better than I did.”

In 2014, Wiley restructured the cija’s Syrian team; as deputy chief of investigations, Mustafa now presided over all the group’s provincial cells. “He was very good at finding documents, and he understood evidence and law,” Wiley said. “But he was also respected by his peers. And he had a natural empathy, which translated into him being a very good interviewer” of victims and perpetrators alike. According to Omar, Mustafa often cut short his appearances at social gatherings, citing family or work. “I know it’s a cliché, but he really was a family guy,” Wiley told me. “But where he excelled in our view—because we don’t need a bunch of good family guys, to be blunt—is that he could execute.”

That July, Assad’s General Intelligence Directorate apparently learned of the cija’s activities, long before the group had been named in the press. In a document that was sent to at least ten intelligence branches—and which was later captured by the cija—the directorate identified Mustafa as “vice-chairman” of the group, and also listed the names of the leading investigators within each of the cija’s governorate cells. At the bottom of the document, the head of the directorate handwrote orders to “arrest them along with their collaborators.”

By now, Western governments, which had pledged to support secular opposition groups, found the situation in northern Syria unpalatable; there was no way to guarantee that weapons given to a secular armed faction would not end up in jihadi hands. Saadeddin had begun to lose hope in the revolution—a sentiment that grew only stronger when Assad’s forces killed more than a thousand civilians with sarin gas, and the Obama Administration backed away from its “red-line” warning of retaliation. “At that point, I lost all faith in the international community,” Saadeddin told me. “I felt that they didn’t want Syria to become liberated—they wanted Syria to stay as it was.” He moved into the defected officers’ camp in southern Turkey, where he remained—feeling “rotten,” consumed by a sense of impotence and frustration—for most of the next decade.

I First Came Into Contact with the cija late in the summer of 2015. By that point, the group had smuggled more than six hundred thousand documents out of Syria, and had prepared a legal brief that assigned individual criminal responsibility for the torture and murder of thousands of people in detention centers to senior members of the Syrian security-intelligence apparatus—including Assad himself. In the following years, the cija expanded its operations to Iraq, Myanmar, Libya, and Ukraine. But Syria was always at the core.

“In terms of the opposition overrunning regime territory—that effectively ceased in September, 2015, when the Russians came in,” Wiley recalled. In the following years, Russian fighter jets pummelled areas under rebel control, while fighters from Russian mercenary groups, Iranian militias, and Hezbollah reinforced Assad’s troops on the ground. In time, the confrontation lines settled, with the country effectively carved into areas under regime, opposition, Turkish, and Kurdish control. But Mustafa and other investigators continued to identify troves of documents, scattered among various hidden sites. “We’d acquire them from different places, and then concentrate them,” Wiley said. Omar told me that it was best to keep files as close to the border as possible, to limit the chance of their being destroyed in the event that the regime took back ground. “Mustafa would sometimes spend a week or more prepping for document extractions,” Omar said. “He would sleep in tents,” in camps filled with other displaced civilians, “while he waited for the right moment to move the files closer to the border.”

At the cija’s headquarters, in Western Europe, the organization built cases against senior intelligence officers, like the double agent Khaled al-Halabi, and provided evidence to European prosecutors who were investigating lesser targets all over the continent. In recent years, Western prosecutors and police agencies have sent hundreds of requests for investigative assistance to the cija headquarters; when the answers can’t be found in the existing files, analysts refer the inquiries, via Mick, the Australian in southern Turkey, to the Syrians on the ground. “We wouldn’t tell them who’s asking, or who the suspects are,” Wiley said. “We’d just say, ‘O.K., we’re interested in witnesses to a particular crime base’—a security-intelligence facility, a static killing, an execution, that kind of thing. And then they would identify witnesses and do a screening interview.” When requests came through, Mick told me, “Mustafa was usually the first team member that I went to, because his networks were so good.”

During the peak years of the pandemic, Mustafa identified and collected witness statements against a trio of Syrian isis members who had been active in a remote village in the deserts of central Syria and were now scattered across Western Europe. All three men were arrested after his death.

Perhaps Mustafa’s most enduring contribution to the cija’s casework is found in one of the group’s most comprehensive, confidential investigative briefs, which I read at the headquarters this spring. It’s a three-hundred-page document, with almost thirteen hundred footnotes, establishing individual criminal responsibility for war crimes carried out during the regime’s 2012 siege of Baba Amr, a neighborhood in the southern part of Mustafa’s home city, Homs. Other cases have centered on torture in detention facilities; this is the first Syrian war-crimes brief that focusses on the conduct of hostilities, and it spells out, in astonishing and historic detail, a litany of crimes, ranging from indiscriminate shelling to mass executions of civilians who were rounded up and killed in warehouses and factories as regime forces swept through. The Homs Brief—for which Mustafa collected much of the underlying evidence—also assigns criminal responsibility to individual commanders within the Syrian Army’s 18th Tank Division, which carried out the assault.

“He thought he was contributing to a better Syria,” Wiley said. “When—and what it would look like—was unsure. But he believed in what he was doing. He could have fucked off years ago. We probably could have gotten him to Canada. We talked about it, because one of his daughters had a congenital heart issue.” Nevertheless, he stayed.

Last year, Mustafa bought an apartment on the eleventh floor of a new tower block in Antakya. Rula’s aunt moved into the same building, a couple of stories below. Her parents left the defected officers’ camp and moved into another apartment block, a short walk up the road. A few months later, Mick recalled, “Mustafa said to me, ‘When I’m at home with my family, it doesn’t matter what’s happening outside—it doesn’t matter if there’s a war. When I’m at home, I’m at peace.’ ”

Last December, Mick was visiting Mustafa’s apartment when the floor began to shake. “It spooked me—it was my first time feeling this kind of tremor,” Mick recalled. Mustafa laughed and said that they happen “all the time.” Then he went to check on Rula and the children, who reported that they hadn’t even felt it.

A couple of months later, Mick awoke to news of the catastrophic earthquake and tried to call members of his Syrian team. But the cellular networks were down in Antakya, and it was impossible for him to travel there, because the local airport’s runway had buckled, along with many local roads.

Saadeddin’s sister was dug out of the complex alive; her husband survived as well, but died in a hospital soon afterward, without anyone in the family knowing where he was. On the fourth day of search-and-rescue operations, Mustafa’s passport was found in the rubble. Then his laptop, then his wife’s handbag. “When they found the bodies,” Omar said, “Mustafa was hugging his daughter, his wife was hugging their son, and the other two children were hugging each other.”

Omar spent the next several days sleeping in his car, along with his wife and six children. Thousands of aftershocks shook the region, and, by the time I met with him, a few hundred metres from the Syrian border, he was so rattled that he reacted to everyday sounds as if they might signal a building’s collapse. His breath was short and his eyes welled with tears; Mustafa had been one of his best friends, and he had also lost eleven relatives to the quake, all of whom had been displaced from the same village in northern Syria. Then his young son walked into the room, and he turned his head. “We try to hide from our children our fear and our grief, so that they don’t feel as if we are weak,” he said.

A few weeks after the earthquake, there was an empty seat at a prestigious international-criminal-investigations course, in the Hague. Mustafa had been scheduled to attend. “We can mitigate the effects of war, except bad luck, but we didn’t factor an earthquake into the plan, institutionally,” Wiley told me. Mick coördinated humanitarian assistance for displaced investigators, and, as Wiley put it, “the operational posture came back really quickly.” Omar has now taken over Mustafa’s leadership duties. “Keep in mind how resilient this cadre is,” Wiley continued. “They’re already all refugees, perhaps with the rare exception. They had already lost their homes, lost all their stuff.”

It was the middle of April, more than two months after the quake. Much of Antakya had been completely flattened, and what still stood was cracked and broken, completely abandoned, and poised to collapse. Mick and I made our way through the old city on foot; the alleys were too narrow for digging equipment to go through, and so we found ourselves climbing over rubble, as if the buildings had fallen the day before. The pets of those entombed in the collapsed buildings followed us, still wearing their collars—bewildered, brand-new strays. ♦

#Syria 🇸🇾 | Earthquakes | Türkiye 🇹🇷 | War Crimes#President Bashar al-Assad#War-Crimes Investigator#Secret Life#Anonymous Death#History#Ben Taub#The New Yorker#Mustafa | Trial Lawyer

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Countries throughout Europe now acknowledge that their people and infrastructure are under ceaseless attack. Yet each incident is, by itself, below the threshold that would require a military response or trigger Article 5. In recent months, agents of Russian intelligence are believed to have assassinated a defector in Spain, planted explosives near a pipeline in Germany, carried out arson attacks all over the Continent, and sabotaged subsea cables and rail lines. A Russian operative injured himself in Paris while preparing explosives for a terrorist attack on a hardware store, and U.S. intelligence discovered a Russian plot to assassinate the C.E.O. of one of Europe’s largest arms manufacturers. Poland’s interior minister said, ‘We are facing a foreign state that is conducting hostile and—in military parlance—kinetic action on Polish territory.’ Every European country that borders Russia is preparing for a wider war in the event of a Russian victory in Ukraine. Poland and the Baltics are digging trenches at their borders and fortifying them, often with antitank obstacles known as ‘dragon’s teeth.’ Finland cast aside seventy years of neutrality and nonalignment to join NATO; Sweden cast aside two hundred.”

—Ben Taub for The New Yorker

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Bari Weiss

There was not a single conversation that I had in the week I spent in Israel where the person did not say a version of the following: There was an October 6 version of me and an October 7 version of me. I am forever changed. I am a different person.

And that is another sense in which the story of the ancient Roman requires modification. The binary of war and peace, the pastoral and the military, is a retrospective luxury of powerful nations or empires. A small democracy, whose very existence is contested by populous autocracies, does not have the privilege, as Cincinnatus did, of going from the field of battle to the field to till. Israel’s citizen-soldiers are scientists, artists, and farmers, just as they are mothers and fathers, husbands and wives. Israeli citizens, whether they serve or not, are not—as one Hamas leader said of Gazans—someone else’s problem.

“It’s like after you knock your finger with a hammer, you don’t feel anything for a while,” the journalist Gadi Taub said, describing what Israelis have gone through since Hamas’s invasion. “People haven’t begun to understand the extent of this earthquake and how it will change Israel. The tectonic plates have moved, and nothing in the system has yet absorbed or changed to accommodate what happened.”

The public intellectual and Bible scholar Micah Goodman told me in Jerusalem that the country went through a collective near-death experience. Imagine an entire society that, between sunrise and sunset, peered together into the abyss. “For the first time in our lives, we had a moment where we could imagine that the whole thing was over. That the whole thing ended. You know how when individuals have a near-death experience, they’re transformed. Because they learned that life should not be trivialized. As a country, we had a near-death experience, and now we’re transformed because we know that Jewish sovereignty should not be taken for granted. It can’t be trivialized.”

Israel’s founding fathers and mothers, having known a period when Jews didn’t have a state—a period in which six million Jews were murdered—understood the difference between statelessness and sovereignty in their bones. The paradox of their extraordinary achievement is that modern Israelis, who might appreciate the distinction intellectually, could dismiss the dread alternative even when presented with visible evidence of a fragility they consigned to the past. Or at least they could until October 7. On that day, the thought exercise became real.

If Israel, in other words, is currently fighting a second war of independence—an existential war necessary for the survival of the state, as everyone here believes—then the young men and women of this country are more than soldiers. They are latter-day Ben-Gurions. They are a new generation of founders. Indeed, as Gadi Taub told me in Tel Aviv, one of the slogans of this war is lo noflim midor tachach! Which loosely translates to do not fall short of the ’48 generation.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Choice: Fight to Win

Yesterday Israel preempted a potentially disastrous attack by Hezbollah on the center of the country. Thirty minutes before launch time, our aircraft destroyed literally thousands of launchers, rockets, and drones that were aimed at various targets including IDF headquarters in Tel Aviv and sensitive installations in the North.

Despite being an impressive technical and tactical achievement, it does not herald a new, more aggressive Israeli military policy. A column in the Israel Hayom newspaper this morning was titled “Preemptive operation, not preemptive attack,” and that sums it up. The 100 aircraft that were involved were simply a more elaborate and expensive Iron Dome. Admittedly the enemy lost more assets than the rockets and drones it had planned to use; launchers and installations were also destroyed. But the objective of the operation was entirely defensive. Great care was taken to ensure that it would be seen as a “legitimate” response to aggression. Israel waited until just before Hezbollah was expected to fire, and the attack was limited to southern Lebanon. As is always the case when we play pure defense, the enemy has learned lessons and will try again.

It was telling that Israel and the US both indicated that the US knew about it in advance, and that the attack was “fully coordinated” with the US. It’s well known that the US forbids Israel to preemptively attack its enemies, so it was important to present it as limited and “intended to prevent escalation.” But it should be noted that Hezbollah did succeed to launch some 300 weapons at the northern part of Israel, from which tens of thousands of citizens have become refugees. The defensive strike still did not enable them to return home. No purely defensive operation can.

American policy continues to have as its top objective the prevention of escalation. The pressure to reach a cease-fire agreement with Hamas continues at a high level. Although they are often presented as “hostage return” deals, no proposal has been seriously considered that allows more than a minority of the living hostages in the hands of Hamas to return. The Americans have made it clear that they intend for any temporary cease-fire to become permanent, or at least extended; and this implies the continued rule of Hamas and the abandonment of more than half of the hostages.

Israel cannot allow a situation to continue in which large numbers of her citizens from both the northern and southern parts of the country have been driven from their homes and can’t return for fear of rocket attacks and 7 October-style invasions. Essentially, a third of our country has been occupied by our enemies since 7 October. This is the status quo that American-brokered diplomatic “solutions” will perpetuate.

American forces have been sent to the region to prevent escalation by either side while they pursue diplomatic initiatives. But today Israeli deterrence is at its lowest point in years, and any American-brokered compromises with Hamas, Hezbollah, or Iran, will be disastrous to us.

If the Democrats win the US presidency, it’s expected that the pro-Iranian policy begun under Obama will gather steam. The Iranian regime is not sitting idly by, but is galloping toward the finish line in developing its nuclear umbrella. Israel can’t afford to wait and hope for a more friendly administration next January, which may or may not materialize.

Israel lost her way strategically at some point, when her military leadership buckled under American pressure, abandoned Ben Gurion’s philosophy of taking the war to her enemies, and began to fight, as Gadi Taub said, “with a shield but without a sword.” We have paid a huge price for this, and it’s not sustainable. Now we are at the point at which we have no choice but to fight to win.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

July 2023 reading

Books:

Melissa Gira Grant, Playing The Whore: The Work Of Sex Work

Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary tr. Eleanor Marx-Aveling

John Lahr, Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh: Tennessee Williams

Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude tr. Gregory Rabassa

Sayaka Murata, Earthlings tr. Ginny Tapley Takemori

John Rieder, Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction

Tennessee Williams, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Tennessee Williams, The Glass Menagerie

Tennessee Williams, Memoirs

Tennessee Williams, A Streetcar Named Desire

Tennessee Williams, Suddenly Last Summer

Essays:

Paul Kincaid, On the Origins of Genre

Articles:

Alex Barasch, After "Barbie," Mattel Is Raiding Its Entire Toybox

Max Fox, Free the Children

Deepa Kumar, Imperialist Feminism

Terry Nguyen, The Diversity Elevator - On R.F. Kuang's Yellowface

Mandy Shunnarah, Olives, Climate Change, and Zionism

Ben Taub, The Titan Submersible Was "An Accident Waiting to Happen"

Short stories:

Sayaka Murata, A Clean Marriage tr. Ginny Tapley Takemori

Other:

Max Graves, What Happens Next

#reading#really short on essays/articles this month sorry gang. i spent 100% of my laptop time reading umineko

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Additional casting for Ragtime (NYCC Annual Gala Presentation) has been announced: Colin Donnell (The Shark is Broken) as Father, Ben Levi Ross (Dear Evan Hansen) as Younger Brother, Tony winner Shaina Taub (Suffs) as Emma Goldman, Joy Woods (The Notebook) as Sarah.

They join the previously announced Joshua Henry (Carousel) as Coalhouse Walker Jr., Caissie Levy (Frozen) as Mother, and Tony winner Brandon Uranowitz (Encores! Titanic) as Tateh.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

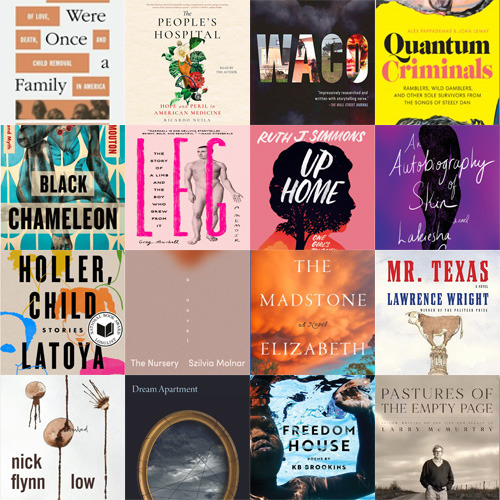

“The Texas Observer’s 2023 Must-Read Lone Star Books” by Senior Editor Lise Olsen, with help from Susan Post of Austin's Bookwoman:

Despite a disturbing rise in book bans, Texas is, against all odds, becoming more and more of a literary hub with authors winning accolades, indie bookstores popping up from Galveston Island to El Paso, and ban-busting librarians and other book-lovers throwing festivals. So as you ponder gifts this holiday season or consider what to read by the fire or by the pool (who can say in December?), pick some Lone Star lit.

Here’s a list of #MustRead 2023 books by Texans or about Texas compiled by the Observer staff with help from Susan Post of Austin’s independent Bookwoman. (Several talented Texans also made best book lists in Slate magazine, The New Yorker, and NPR’s Books We Love.)

NONFICTION

We Were Once a Family: A Story of Love, Death, and Child Removal in America by Dallas journalist Roxanna Asgarian (Farrar, Straus & Giroux) is a dramatic takedown of the Texas foster care and family court system. It’s both a compelling narrative and an investigative tour de force.

The People’s Hospital: Hope and Peril in American Medicine (Simon & Schuster) by Ricardo Nuila, a Houston physician and author, is an eye-opening and surprisingly optimistic read. Nuila delves deeply into what’s wrong with modern medicine by painting rich portraits of the patients he’s treated (and befriended) while working at Harris County’s Ben Taub Hospital, which offers free or low-cost—yet high-quality—care against all odds. Each of them had been forced into impossible positions and suffered additional trauma from obstacles and gaps in insurance, corporate medicine, and Big Pharma.

Waco: David Koresh, the Branch Davidians and a Legacy of Rage (Simon & Schuster) by Fort Worth journalist Jeff Guinn is one of two books that mark the 30th anniversary of the standoff between the Branch Davidians and federal agents that ended with 86 deaths. (The other is Waco Rising by Kevin Cook.) Both authors recount how the 1993 tragedy shaped other extremist leaders in America—and still influences separatist movements today.

Quantum Criminals: Ramblers, Wild Gamblers and Other Sole Survivors from the Songs of Steely Dan (University of Texas Press) by Alex Pappademas and Joan LeMay has been described as the quintessential Steely Dan book. As part of the project, LeMay, a native Houstonian, created 109 whimsical portraits of characters that sprang from the musicians’ lyrics and legends. In a review, fellow artist Melissa Messer wrote: “Looking at Joan’s oeuvre makes me feel tipsy, or like I’ve drunk Wonka’s Fizzy Lifting Drink and I’m swimming through the air after her, searching for the same vision.”

Memoir

Black Cameleon: Memory, Womanhood and Myth(Macmillan) by Debra D.E.E.P. Mouton, the former Houston poet Laureate, shares lyrical memories of her own life mixed with ample asides on Black culture and family lore. Her storylines sink deeply into a dream world, and yet readers emerge without forgetting her deeper messages.

Leg: The Story of a Limb and a Boy Who Grew from It (Abrams Books) by Greg Marshall of Austin has been described as “a hilarious and poignant memoir grappling with family, disability, and coming of age in two closets—as a gay man and as a man living with cerebral palsy.” NPR’s Scott Simon, who interviewed Marshall, described the memoir as “intimate, and I mean that in all ways—insightful and often laugh-out-loud funny.”

Up Home: One Girl’s Journey (Penguin Random House) by Ruth J. Simmonsis a powerful memoir from the Grapeland native who became the president of Brown University and thus, the first Black president of an Ivy League institution. Simmons begins by sharing stories about her parents, who were sharecroppers, and about her life as one of 12 children growing up in a tiny Texas town during the Jim Crow era. For her, the classroom became “a place of brilliant light unlike any our homes afforded.” (Simmons’s other academic credentials include being the former president of Smith College; president of Prairie View A&M University, Texas’s oldest HBCU; and the former vice provost of Princeton.)

Novels and Short Stories

An Autobiography of Skin(Penguin Random House) by Lakiesha Carr weaves together three powerful narratives all featuring Black women from Texas. Carr, a journalist originally from East Texas, plumbs the depths of each character’s struggles, sharing tales of gambling, lost love, abuse, and the power of women to overcome.

Holler, Child (Penguin Random House), a new short story collection from Latoya Watkins, was long-listed for the National Book Award. Her eleven tales press “at the bruises of guilt, love, and circumstance,” as the cover description promises, and introduce West Texas-inspired characters irrevocably shaped by place.

The Nursery (Pantheon Books) by Szilvia Molnar—a surprisingly honest, anatomically accurate (and unsettling) novel about new motherhood—begins: “I used to be a translator and now I am a milk bar.” It’s a riveting and original debut by Molnar, who is originally from Budapest, was raised in Sweden, and now lives in Austin.

Two legendary Austin writers weighed in with new novels on our tall stack of Texas goodreads: The Madstone (Little, Brown and Company) by Elizabeth Crook, the 2023 Texas Writer Award winner, and Mr. Texas, a fictional send-up of Texas politics by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Lawrence Wright.

Poetry

Bookwoman’s Susan Post, who contributed titles to our list, also recommends filling your holiday shelves with poetry by and about Texans:

Dream Apartment (Copper Canyon Press) by Lisa Olstein;

Low (Gray Wolf Press) by Nick Flynn;

Freedom House by KB Brookins (published by Dallas’ Deep Vellum Bookstore & Publishing Co.)

Essays

Pastures of the Empty Page: Fellow Writers on the Life and Legacy of Larry McMurtry (University of Texas Press) edited by George Getchow, contains essays from a who’s who list of Texas writers about Larry McMurtry’s influence on Texas culture and their lives. It includes an array of reflections on history and the writing process as well as anecdotes about McMurtry’s off-beat and innovative life.

To Name the Bigger Lie (Simon & Schuster) by Sarah Viren, an ex-Texan who now teaches creative writing at Arizona State University, (excerpted in Lithub) includes reflections on Viren’s experiences (and misadventures) as an “out” academic and writer in states like Florida, Texas, and Arizona. As she dryly notes, “Critiques of the personal essay, and by extension memoir, are often gendered—not to mention classist and racist and homophobic.”

Can you help us survive, and thrive into our 70th year during this challenging time for the journalism industry?

Right now, all donations to the Texas Observer will be matched. Donate now!

#books#feminism#feminist books#Texas#fiction#nonfiction#poetry#essay#southern fiction#LGBTQIA#gay fiction

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

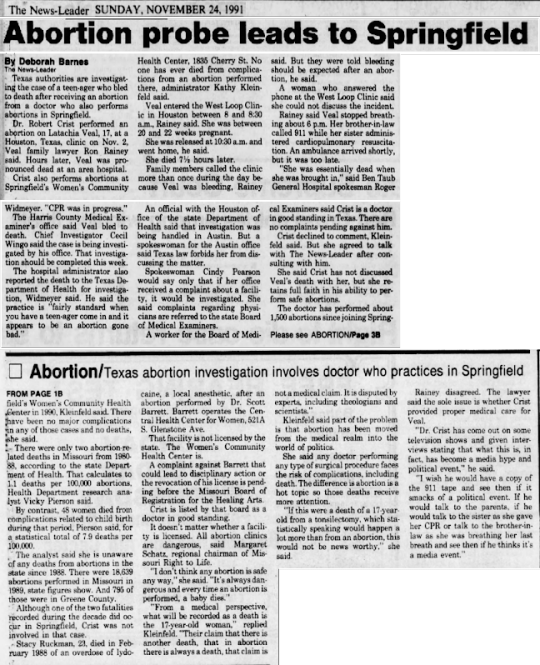

Denise Montoya, 15 (USA 1988)

15-year-old Denise’s parents brought her to Women’s Pavillion in Houston for an abortion on May 13, 1988 when she was 25 weeks pregnant. The abortion was done by Douglas Karpen, who was actually an osteopath and not an OB/GYN.

In what a lawsuit later called “extremely foreseeable complications”, Denise lost dangerous amounts of blood and had to be taken to Ben Taub hospital. Her condition deteriorated and she died on May 29, 1988.

Her parents filed suit against Karpen and Women’s Pavillion, saying that they had failed to adequately explain the risks of the procedure and had not had the parents sign any informed consent document before the abortion that killed Denise and her baby. No consent forms were even provided. Denise’s parents said that had they known how dangerous abortion is at 25 weeks, they never would have subjected their young daughter to the hazardous procedure.

Karpen was later caught killing babies born alive after attempted abortions. His own former employees testified that he killed the babies with his bare hands by twisting their necks “execution style.”

(court documents)

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Titan Submersible Was “An Accident Waiting to Happen”

Interviews and e-mails with expedition leaders and employees reveal how OceanGate ignored desperate warnings from inside and outside the company. “It’s a lemon,” one wrote.

— By Ben Taub | July 1, 2023

Stockton Rush, the co-founder and C.E.O. of OceanGate, inside Cyclops I, a submersible, on July 19, 2017. Photographs by Balazs Gardi

The primary task of a submersible is to not implode. The second is to reach the surface, even if the pilot is unconscious, with oxygen to spare. The third is for the occupants to be able to open the hatch once they surface. The fourth is for the submersible to be easy to find, through redundant tracking and communications systems, in case rescue is required. Only the fifth task is what is ordinarily thought of as the primary one: to transport people into the dark, hostile deep.

At dawn four summers ago, the French submariner and Titanic expert Paul-Henri Nargeolet stood on the bow of an expedition vessel in the North Atlantic. The air was cool and thick with fog, the sea placid, the engine switched off, and the Titanic was some thirty-eight hundred metres below. The crew had gathered for a solemn ceremony, to pay tribute to the more than fifteen hundred people who had died in the most famous maritime disaster more than a hundred years ago. Rob McCallum, the expedition leader, gave a short speech, then handed a wreath to Nargeolet, the oldest man on the ship. As is tradition, the youngest—McCallum’s nephew—was summoned to place his hand on the wreath, and he and Nargeolet let it fall into the sea.

Inside a hangar on the ship’s stern sat a submersible known as the Limiting Factor. In the previous year, McCallum, Nargeolet, and others had taken it around the Earth, as part of the Five Deeps Expedition, a journey to the deepest point in each ocean. The team had mapped unexplored trenches and collected scientific samples, and the Limiting Factor’s chief pilot, Victor Vescovo—a Texan hedge-fund manager who had financed the entire operation—had set numerous diving records. But, to another member of the expedition team, Patrick Lahey, the C.E.O. of Triton Submarines (which had designed and built the submersible), one record meant more than the rest: the marine-classification society DNV had certified the Limiting Factor’s “maximum permissible diving depth” as “unlimited.” That process was far from theoretical; a DNV inspection engineer was involved in every stage of the submersible’s creation, from design to sea trials and diving. He even sat in the passenger seat as Lahey piloted the Limiting Factor to the deepest point on Earth.

After the wreath sank from view, Vescovo climbed down the submersible hatch, and the dive began. For some members of the crew, the site of the wreck was familiar. McCallum, who co-founded a company called eyos Expeditions, had transported tourists to the Titanic in the two-thousands, using two Soviet submarines that had been rated to six thousand metres. Another crew member was a Titanic obsessive—his endless talk of davits and well decks still rattles in my head. But it was Paul-Henri Nargeolet whose life was most entwined with the Titanic. He had dived it more than thirty times, beginning shortly after its discovery, in 1985, and now served as the underwater-research director for the organization that owns salvaging rights to the wreck.

Nargeolet had also spent the past year as Vescovo’s safety manager. “When I set out on the Five Deeps project, I told Patrick Lahey, ‘Look, I don’t know submarine technology—I need someone who works for me to independently validate whatever design you come up with, and its construction and operation,’ ” Vescovo recalled, this week. “He recommended P. H. Nargeolet, whom he had known for decades.” Nargeolet, whose wife had recently died, was a former French naval commander—an underwater-explosives expert who had spent much of his life at sea. “He had a sterling reputation, the perfect résumé,” Vescovo said. “And he was French. And I love the French.”

When Vescovo reached the silty bottom at the Titanic site, he recalled his private preparations with Nargeolet. “He had very good knowledge of the currents and the wreck,” Vescovo told me. “He briefed me on very specific tactical things: ‘Stay away from this place on the stern’; ‘Don’t go here’; ‘Try and maintain this distance at this part of the wreck.’ ” Vescovo surfaced about seven hours later, exhausted and rattled from the debris that he had encountered at the ship’s ruins, which risk entangling submersibles that approach too close. But the Limiting Factor was completely fine. According to its certification from DNV, a “deep dive,” for insurance and inspection purposes, was anything below four thousand metres. A journey to the Titanic, thirty-eight hundred metres down, didn’t even count.

Nargeolet remained obsessed with the Titanic, and, before long, he was invited to return. “To P. H., the Titanic was Ulysses’ sirens—he could not resist it,” Vescovo told me. A couple of weeks ago, Nargeolet climbed into a radically different submersible, owned by a company called OceanGate, which had spent years marketing to the general public that, for a fee of two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, it would bring people to the most famous shipwreck on Earth. “People are so enthralled with Titanic,” OceanGate’s founder, Stockton Rush, told a BBC documentary crew last year. “I read an article that said there are three words in the English language that are known throughout the planet. And that’s ‘Coca-Cola,’ ‘God,’ and ‘Titanic.’ ”

Nargeolet served as a guide to the wreck, Rush as the pilot. The other three occupants were tourists, including a father and son. But, before they reached the bottom, the submersible vanished, triggering an international search-and-rescue operation, with an accompanying media frenzy centered on counting down the hours until oxygen would run out.

McCallum, who was leading an expedition in Papua New Guinea at the time, knew the outcome almost instantly. “The report that I got immediately after the event—long before they were overdue—was that the sub was approaching thirty-five hundred metres,” he told me, while the oxygen clock was still ticking. “It dropped weights”—meaning that the team had aborted the dive—“then it lost comms, and lost tracking, and an implosion was heard.”

An investigation by the U.S. Coast Guard is ongoing; some debris from the wreckage has been salvaged, but the implosion was so violent and comprehensive that the precise cause of the disaster may never be known.

Until June 18th, a manned deep-ocean submersible had never imploded. But, to McCallum, Lahey, and other experts, the OceanGate disaster did not come as a surprise—they had been warning of the submersible’s design flaws for more than five years, filing complaints to the U.S. government and to OceanGate itself, and pleading with Rush to abandon his aspirations. As they mourned Nargeolet and the other passengers, they decided to reveal OceanGate’s history of knowingly shoddy design and construction. “You can’t cut corners in the deep,” McCallum had told Rush. “It’s not about being a disruptor. It’s about the laws of physics.”

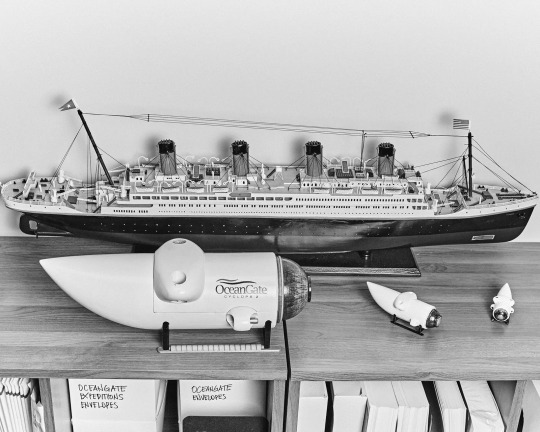

The submersible Antipodes at the OceanGate headquarters, in Everett, Washington, on July 19, 2017.

Stockton Rush was named for two of his ancestors who signed the Declaration of Independence: Richard Stockton and Benjamin Rush. His maternal grandfather was an oil-and-shipping tycoon. As a teen-ager, Rush became an accomplished commercial jet pilot, and he studied aerospace engineering at Princeton, where he graduated in 1984.

Rush wanted to become a fighter pilot. But his eyesight wasn’t perfect, and so he went to business school instead. Years later, he expressed a desire to travel to space, and he reportedly dreamed of becoming the first human to set foot on Mars. In 2004, Rush travelled to the Mojave Desert, where he watched the launch of the first privately funded aircraft to brush against the edge of space. The only occupant was the test pilot; nevertheless, as Rush used to tell it, Richard Branson stood on the wing and announced that a new era of space tourism had arrived. At that point, Rush “abruptly lost interest,” according to a profile in Smithsonian magazine. “I didn’t want to go up into space as a tourist,” he said. “I wanted to be Captain Kirk on the Enterprise. I wanted to explore.”

Rush had grown up scuba diving in Tahiti, the Cayman Islands, and the Red Sea. In his mid-forties, he tinkered with a kit for a single-person mini-submersible, and piloted it around at shallow depths near Seattle, where he lived. A few years later, in 2009, he co-founded OceanGate, with a dream to bring tourists to the ocean world. “I had come across this business anomaly I couldn’t explain,” he recalled. “If three-quarters of the planet is water, how come you can’t access it?”

OceanGate’s first submersible wasn’t made by the company itself; it was built in 1973, and Lahey later piloted it in the North Sea, while working in the oil-and-gas industry. In the nineties, he helped refit it into a tourist submersible, and in 2009, after it had been sold a few times, and renamed Antipodes, OceanGate bought it. “I didn’t have any direct interaction with them at the time,” Lahey recalled. “Stockton was one of these people that was buying these older subs and trying to repurpose them.”

In 2015, OceanGate announced that it had built its first submersible, in collaboration with the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory. In fact, it was mostly a cosmetic and electrical refit; Lahey and his partners had built the underlying vessel, called Lula, for a Portuguese marine research nonprofit almost two decades before. It had a pressure hull that was the shape of a capsule pill and made of steel, with a large acrylic viewport on one end. It was designed to go no deeper than five hundred metres—a comfortable cruising depth for military submarines. OceanGate now called it Cyclops I.

Most submersibles have duplicate control systems, running on separate batteries—that way, if one system fails, the other still works. But, during the refit, engineers at the University of Washington rigged the Cyclops I to run from a single PlayStation 3 controller. “Stockton is very interested in being able to quickly train pilots,” Dave Dyer, a principal engineer, said, in a video published by his laboratory. Another engineer referred to it as “a combination steering wheel and gas pedal.”

Around that time, Rush set his sights on the Titanic. OceanGate would have to design a new submersible. But Rush decided to keep most of the design elements of Cyclops I. Suddenly, the University of Washington was no longer involved in the project, although OceanGate’s contract with the Applied Physics Laboratory was less than one-fifth complete; it is unclear what Dyer, who did not respond to an interview request, thought of Rush’s plan to essentially reconstruct a craft that was designed for five hundred metres of pressure to withstand eight times that much. As the company planned Cyclops II, Rush reached out to McCallum for help.

“He wanted me to run his Titanic operation for him,” McCallum recalled. “At the time, I was the only person he knew who had run commercial expedition trips to Titanic. Stockton’s plan was to go a step further and build a vehicle specifically for this multi-passenger expedition.” McCallum gave him some advice on marketing and logistics, and eventually visited the workshop, outside Seattle, where he examined the Cyclops I. He was disturbed by what he saw. “Everyone was drinking Kool-Aid and saying how cool they were with a Sony PlayStation,” he told me. “And I said at the time, ‘Does Sony know that it’s been used for this application? Because, you know, this is not what it was designed for.’ And now you have the hand controller talking to a Wi-Fi unit, which is talking to a black box, which is talking to the sub’s thrusters. There were multiple points of failure.” The system ran on Bluetooth, according to Rush. But, McCallum continued, “every sub in the world has hardwired controls for a reason—that if the signal drops out, you’re not fucked.”

One day, McCallum climbed into the Cyclops for a test dive at a marina. There, he met the chief pilot, David Lochridge, a Scotsman who had spent three decades as a submersible pilot and an engineer—first in the Royal Navy, then as a private contractor. Lochridge had worked all over the world: on offshore wind farms in the North Sea; on subsea-cables installations in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans; on manned submarine trials with the Swedish Navy; on submarine-rescue operations for the navies of Britain and Singapore. But, during the harbor trial, the Cyclops got stuck in shallow water. “It was hilarious, because there were four very experienced operators in the sub, stuck at twenty or twenty-five feet, and we had to sit there for a few hours while they worked it out,” McCallum recalled. He liked and trusted Lochridge. But, of the sub, he said, “This thing is a mutt.”

Rush eventually decided that he would not attempt to have the Titanic-bound vehicle classed by a marine-certification agency such as DNV. He had no interest in welcoming into the project an external evaluator who would, as he saw it, “need to first be educated before being qualified to ‘validate’ any innovations.”

That marked the end of McCallum’s desire to be associated with the project. “The minute that I found out that he was not going to class the vehicle, that’s when I said, ‘I’m sorry, I just can’t be involved,’ ” he told me. “I couldn’t tell him anything about the Five Deeps project at that time. But I was able to say, ‘Look, I am involved with other projects that are building classed subs’—of course, I was talking about the Limiting Factor—‘and I can tell you that the class society has been nothing but supportive. They are actually part of our innovation process. We’re using the brainpower of their engineers to feed into our design.

“Stockton didn’t like that,” McCallum continued. “He didn’t like to be told that he was on the fringe.” As word got out that Rush planned to take tourists to the Titanic, McCallum recalled, “people would ring me, and say, ‘We’ve always wanted to go to Titanic. What do you think?’ And I would tell them, ‘Never get in an unclassed sub. I wouldn’t do it, and you shouldn’t, either.’ ”

In early 2018, McCallum heard that Lochridge had left OceanGate. “I’d be keen to pick your brain if you have a few moments,” McCallum e-mailed him. “I’m keen to get a handle on exactly how bad things are. I do get reports, but I don’t know if they are accurate.” Whatever his differences with Rush, McCallum wanted the venture to succeed; the submersible industry is small, and a single disaster could destroy it. But the only way forward without a catastrophic operational failure—which he had been told was “certain,” he wrote—was for OceanGate to redesign the submersible in coördination with a classification society. “Stockton must be gutted,” McCallum told Lochridge, of his departure. “You were the star player . . . . . and the only one that gave me a hint of confidence.”

“I think you are going to [be] even more taken aback when I tell you what’s happening,” Lochridge replied. He added that he was afraid of retaliation from Rush—“We both know he has influence and money”—but would share his assessment with McCallum, in private: “That sub is Not safe to dive.”

“Do you think the sub could be made safe to dive, or is it a complete lemon?” McCallum replied. “You will get a lot of support from people in the industry . . . . everyone is watching and waiting and quietly shitting their pants.”

“It’s a lemon.”

“Oh dear,” McCallum replied. “Oh dear, oh dear.”

David Lochridge, OceanGate’s former director of marine operations, pilots Cyclops I during a test dive in Everett, on July 19, 2017.

Lochridge had been hired by OceanGate in May, 2015, as its director of marine operations and chief submersible pilot. The company moved him and his family to Washington, and helped him apply for a green card. But, before long, he was clashing with Rush and Tony Nissen, the company’s director of engineering, on matters of design and safety.

Every aspect of submersible design and construction is a trade-off between strength and weight. In order for the craft to remain suspended underwater, without rising or falling, the buoyancy of each component must be offset against the others. Most deep-ocean submersibles use spherical titanium hulls and are counterbalanced in water by syntactic foam, a buoyant material made up of millions of hollow glass balls, which is attached to the external frame. But this adds bulk to the submersible. And the weight of titanium limits the practical size of the pressure hull, so that it can accommodate no more than two or three people. Spheres are “the best geometry for pressure, but not for occupation,” as Rush put it.

The Cyclops II needed to fit as many passengers as possible. “You don’t do the coolest thing you’re ever going to do in your life by yourself,” Rush told an audience at the GeekWire Summit last fall. “You take your wife, your son, your daughter, your best friend. You’ve got to have four people” besides the pilot. Rush planned to have room for a Titanic guide and three passengers. The Cyclops II could fit that many occupants only if it had a cylindrical midsection. But the size dictated the choice of materials. The steel hull of Cyclops I was too thin for Titanic depths—but a thicker steel hull would add too much weight. In December, 2016, OceanGate announced that it had started construction on Cyclops II, and that its cylindrical midsection would be made of carbon fibre. The idea, Rush explained in interviews, was that carbon fibre was a strong material that was significantly lighter than traditional metals. “Carbon fibre is three times better than titanium on strength-to-buoyancy,” he said.

A month later, OceanGate hired a company called Spencer Composites to build the carbon-fibre hull. “They basically said, ‘This is the pressure we have to meet, this is the factor of safety, this is the basic envelope. Go design and build it,’ ” the founder, Brian Spencer, told CompositesWorld, in the spring of 2017. He was given a deadline of six weeks.

Toward the end of that year, Lochridge became increasingly concerned. OceanGate would soon begin manned sea trials for Cyclops II in the Bahamas, and he believed that there was a chance that they would result in catastrophe. The consequences for Lochridge could extend beyond OceanGate’s business and the trauma of losing colleagues; as director of marine operations, Lochridge had a contract specifying that he was ultimately responsible for “ensuring the safety of all crew and clients.”

On the workshop floor, he raised questions about potential flaws in the design and build processes. But his concerns were dismissed. OceanGate’s position was that such matters were outside the scope of his responsibilities; he was “not hired to provide engineering services, or to design or develop Cyclops II,” the company later said, in a court filing. Nevertheless, before the handover of the submersible to the operations team, Rush directed Lochridge to carry out an inspection, because his job description also required him to sign off on the submersible’s readiness for deployment.

On January 18, 2018, Lochridge studied each major component, and found several critical aspects to be defective or unproven. He drafted a detailed report, which has not previously been made public, and attached photographs of the elements of greatest concern. Glue was coming away from the seams of ballast bags, and mounting bolts threatened to rupture them; both sealing faces had errant plunge holes and O-ring grooves that deviated from standard design parameters. The exostructure and electrical pods used different metals, which could result in galvanic corrosion when exposed to seawater. The thruster cables posed “snagging hazards”; the iridium satellite beacon, to transmit the submersible’s position after surfacing, was attached with zip ties. The flooring was highly flammable; the interior vinyl wrapping emitted “highly toxic gasses upon ignition.”

To assess the carbon-fibre hull, Lochridge examined a small cross-section of material. He found that it had “very visible signs of delamination and porosity”—it seemed possible that, after repeated dives, it would come apart. He shone a light at the sample from behind, and photographed beams streaming through splits in the midsection in a disturbing, irregular pattern. The only safe way to dive, Lochridge concluded, was to first carry out a full scan of the hull.

The next day, Lochridge sent his report to Rush, Nissen, and other members of the OceanGate leadership. “Verbal communication of the key items I have addressed in my attached document have been dismissed on several occasions, so I feel now I must make this report so there is an official record in place,” he wrote. “Until suitable corrective actions are in place and closed out, Cyclops 2 (Titan) should not be manned during any of the upcoming trials.”

Rush was furious; he called a meeting that afternoon, and recorded it on his phone. For the next two hours, the OceanGate leadership insisted that no hull testing was necessary—an acoustic monitoring system, to detect fraying fibres, would serve in its place. According to the company, the system would alert the pilot to the possibility of catastrophic failure “with enough time to arrest the descent and safely return to surface.” But, in a court filing, Lochridge’s lawyer wrote, “this type of acoustic analysis would only show when a component is about to fail—often milliseconds before an implosion—and would not detect any existing flaws prior to putting pressure onto the hull.” A former senior employee who was present at the meeting told me, “We didn’t even have a baseline. We didn’t know what it would sound like if something went wrong.”

OceanGate’s lawyer wrote, “The parties found themselves at an impasse—Mr. Lochridge was not, and specifically stated that he could not be made comfortable with OceanGate’s testing protocol, while Mr. Rush was unwilling to change the company’s plans.” The meeting ended in Lochridge’s firing.

Soon afterward, Rush asked OceanGate’s director of finance and administration whether she’d like to take over as chief submersible pilot. “It freaked me out that he would want me to be head pilot, since my background is in accounting,” she told me. She added that several of the engineers were in their late teens and early twenties, and were at one point being paid fifteen dollars an hour. Without Lochridge around, “I could not work for Stockton,” she said. “I did not trust him.” As soon as she was able to line up a new job, she quit.

“I would consider myself pretty ballsy when it comes to doing things that are dangerous, but that sub is an accident waiting to happen,” Lochridge wrote to McCallum, two weeks later. “There’s no way on earth you could have paid me to dive the thing.” Of Rush, he added, “I don’t want to be seen as a Tattle tale but I’m so worried he kills himself and others in the quest to boost his ego.”

McCallum forwarded the exchange to Patrick Lahey, the C.E.O. of Triton Submarines, whose response was emphatic: if Lochridge “genuinely believes this submersible poses a threat to the occupants,” then he had a moral obligation to inform the authorities. “To remain quiet makes him complicit,” Lahey wrote. “I know that may sound ominous but it is true. History is full of horrific examples of accidents and tragedies that were a direct result of people’s silence.”

OceanGate claimed that Cyclops II had “the first pressure vessel of its kind in the world.” But there’s a reason that Triton and other manufacturers don’t use carbon fibre in their hulls. Under compression, “it’s a capricious fucking material, which is the last fucking thing you want to associate with a pressure boundary,” Lahey told me.

“With titanium, there’s a purpose to a pressure test that goes beyond just seeing whether it will survive,” John Ramsay, the designer of the Limiting Factor, explained. The metal gradually strengthens under repeated exposure to incredible stresses. With carbon fibre, however, pressure testing slowly breaks the hull, fibre by tiny fibre. “If you’re repeatedly nearing the threshold of the material, then there’s just no way of knowing how many cycles it will survive,” he said.

“It doesn’t get more sensational than dead people in a sub on the way to Titanic,” Lahey’s business partner, the co-founder of Triton Submarines, wrote to his team, on March 1, 2018. McCallum tried to reason with Rush directly. “You are wanting to use a prototype un-classed technology in a very hostile place,” he e-mailed. “As much as I appreciate entrepreneurship and innovation, you are potentially putting an entire industry at risk.”

Rush replied four days later, saying that he had “grown tired of industry players who try to use a safety argument to stop innovation and new entrants from entering their small existing market.” He understood that his approach “flies in the face of the submersible orthodoxy, but that is the nature of innovation,” he wrote. “We have heard the baseless cries of ‘you are going to kill someone’ way too often. I take this as a serious personal insult.”

In response, McCallum listed a number of specific concerns, from his “humble perch” as an expedition leader. “In your race to Titanic you are mirroring that famous catch cry ‘she is unsinkable,’ ” McCallum wrote. The correspondence ended soon afterward; Rush asked McCallum to work for him—then threatened him with a lawsuit, in an effort to silence him, when he declined.

By now, McCallum had introduced Lochridge to Lahey. Lahey wrote him, “If Ocean Gate is unwilling to consider or investigate your concerns with you directly perhaps some other means of getting them to pay attention is required.”

Lochridge replied that he had already contacted the United States Department of Labor, alleging to its Occupational Safety and Health Administration that he had been terminated in retaliation for raising safety concerns. He also sent the osha investigator Paul McDevitt a copy of his Cyclops II inspection report, hoping that the government might take actions that would “prevent the potential for harm to life.”

A few weeks later, McDevitt contacted OceanGate, noting that he was looking into Lochridge’s firing as a whistle-blower-protection matter. OceanGate’s lawyer Thomas Gilman soon issued Lochridge a court summons: he had ten days to withdraw his osha claim and pay OceanGate almost ten thousand dollars in legal expenses. Otherwise, Gilman wrote, OceanGate would sue him, take measures to destroy his professional reputation, and accuse him of immigration fraud. Gilman also reported to osha that Lochridge had orchestrated his own firing because he “wanted to leave his job and maintain his ability to collect unemployment benefits.” (McDevitt, of osha, notified the Coast Guard of Lochridge’s complaint. There is no evidence that the Coast Guard ever followed up.)

Lochridge received the summons while he was at his father’s funeral. He and his wife hired a lawyer, but it quickly became clear that “he didn’t have the money to fight this guy,” Lahey told me. (Lochridge declined to be interviewed.) Lahey covered the rest of the expenses, but, after more than half a year of legal wrangling, and threats of deportation, Lochridge withdrew his whistle-blower claim with osha so that he could go on with his life. Lahey was crestfallen. “He didn’t consult me about that decision,” Lahey recalled. “It’s not that he had to—it was his fight, not mine. But I was underwriting the cost of it, because I believed in the idea that this inspection report, which he wouldn’t share with anybody, needed to see the light of day.”

Stockton Rush in front of Cyclops I, on July 19, 2017.

A few weeks after Lochridge was fired, OceanGate announced that it was testing its new submersible in the marina of Everett, Washington, and would soon begin shallow-water trials in Puget Sound. To preëmpt any concerns about the carbon-fibre hull, the company touted the acoustic monitoring system, which was later patented in Rush’s name. “Safety is our number one priority,” Rush said, in an OceanGate press release. “We believe real-time health monitoring should be standard safety equipment on all manned-submersibles.”

“He’s spinning the fact that his sub requires a hull warning system into something positive,” Jarl Stromer, Triton’s regulatory and class-compliance manager, reported to Lahey. “He’s making it sound like the Cyclops is more advanced because it has this system when the opposite is true: The submersible is so experimental, and the factor of safety completely unknown, that it requires a system to warn the pilot of impending collapse.”

Like Lochridge, Triton’s outside counsel, Brad Patrick, considered the risk to life to be so evident that the government should get involved. He drafted a letter to McDevitt, the osha investigator, urging the Department of Labor to take “immediate and decisive action to stop OceanGate” from taking passengers to the Titanic “before people die. It is that simple.” He went on, “At the bottom of all of this is the inevitable tension betwixt greed and safety.”

But Patrick’s letter was never sent. Other people at Triton worried that the Department of Labor might perceive the letter as an attack on a business rival. By now, OceanGate had renamed Cyclops II “Titan,” apparently to honor the Titanic. “I cannot tell you how much I fucking hated it when he changed the goddam name to Titan,” Lahey told me. “That was uncomfortably close to our name.”

“Stockton strategically structured everything to be out of U.S. jurisdiction” for its Titanic pursuits, the former senior OceanGate employee told me. “It was deliberate.” In a legal filing, the company reported that the submersible was “being developed and assembled in Washington, but will be owned by a Bahamian entity, will be registered in the Bahamas and will operate exclusively outside the territorial waters of the United States.” Although it is illegal to transport passengers in an unclassed, experimental submersible, “under U.S. regulations, you can kill crew,” McCallum told me. “You do get in a little bit of trouble, in the eyes of the law. But, if you kill a passenger, you’re in big trouble. And so everyone was classified as a ‘mission specialist.’ There were no passengers—the word ‘passenger’ was never used.” No one bought tickets; they contributed an amount of money set by Rush to one of OceanGate’s entities, to fund their own missions.

“It is truly hard to imagine the discernment it took for Stockton to string together each of the links in the chain,” Patrick noted. “ ‘How do I avoid liability in Washington State? How do I avoid liability with an offshore corporate structure? How do I keep the U.S. Coast Guard from breathing down my neck?’ ”