#Mustafa | Trial Lawyer

Text

The Secret Life and Anonymous Death of the Most Prolific War-Crimes Investigator in History

When Mustafa Died, in the Earthquakes in Türkiye, his Work in Syria had Assisted in the Prosecutions of Numerous Figures in Bashar al-Assad’s Regime.

— By Ben Taub | September 14, 2023

Photo Illustration By Cristiana Couceiro; Source Photograph From Getty Images

It Was 4:17 A.M. on February 6th in Antakya, an Ancient Turkish City Near the Syrian Border, when the earth tore open and people’s beds began to shake. On the third floor of an apartment in the Ekinci neighborhood, Anwar Saadeddin, a former brigadier general in the Syrian Army, awoke to the sounds of glass breaking, cupboard doors banging, and jars of tahini and cured eggplant spilling onto the floor. He climbed out of bed, but, for almost thirty seconds, he was unable to keep his footing; the building was moving side to side. When the earthquake subsided, he tried to call his daughter Rula, who lived down the road, but the cellular network was down.

Thirty seconds after the first quake, the building started moving again, this time up and down, with such violence that an exterior wall sheared open, and rain started pouring in. The noise was tremendous—concrete splitting, rebar bending, plates shattering, neighbors screaming. When the shaking stopped, about a minute later, Saadeddin, who is in his late sixties, and his wife walked down three flights of stairs, dressed in pajamas and sandals, and went out into the cold.

“All of Antakya was black—there was no electricity anywhere,” Saadeddin recalled. Thousands of the city’s buildings had collapsed. Survivors spilled into the streets, crowding rubble-strewn alleyways and searching for open ground, as minarets toppled and glass shards fluttered down from tower blocks. The general and his wife set off in the direction of the building where Rula lived, with her husband, Mustafa, and their four children.

A third quake shook the ground. When Saadeddin made it to his daughter’s apartment block, flashes of lighting illuminated what was now a fourteen-story grave. The building—which had been completed less than two years earlier—had twisted as it toppled over, crushing many of the residents. Saadeddin felt his body drained of all emotion, almost as if it didn’t belong to him.

Saadeddin was not the only person searching for Rula and her family. For the past decade, her husband, Mustafa, had quietly served as the deputy chief of Syria investigations for the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, a group that has captured more than a million pages of documents from Syrian military and intelligence facilities. Using these files, lawyers at the cija have prepared some of the most comprehensive war-crimes cases since the Nuremberg trials, targeting senior Syrian regime officers—including the President, Bashar al-Assad. After the earthquake, the group directed its investigative focus into a search-and-rescue operation for members of its own Syrian team, many of whom had been displaced to southern Turkey after more than a decade of war. By the end of the third day, nearly everyone was accounted for. Two investigators had lost children; one of them had also lost his wife. But Mustafa was still missing.

For as long as Mustafa had been working for the cija, the group had kept his identity secret—even after it captured a Syrian intelligence document that showed that the regime knew about his investigative work and was actively hunting him down. “He was probably my best investigator,” Mustafa’s supervisor, an Australian who goes by Mick, told me, during a recent visit to the Turkish-Syrian border. Documents that Mustafa obtained, and witness interviews that he conducted, have assisted judicial proceedings in the United States, France, Belgium, Germany, and several other European jurisdictions. According to a cija estimate, Mustafa “either directly obtained or supported in the acquisition” of more than two hundred thousand pages of internal Syrian regime documents, likely making him—by sheer volume of evidence collected—the most prolific war-crimes investigator in history.

Twelve years into the Syrian war, at least half the population has been displaced, often multiple times, under varied circumstances of individual tragedy. No one knows the actual death toll—not even to the nearest hundred thousand. And yet the Syrian regime’s crimes continue apace. “The prisons are full,” Bill Wiley, the cija’s founder and executive director, told me. “All the offenses that started being carried out at scale in 2011 are still being perpetrated. Unlawful detention, physical abuse amounting to torture, extrajudicial killing, sexual offenses—all of that continues. War crimes on the battlefield, particularly in the context of aerial operations. There are still chemical attacks. It all continues. But, as long as there’s the drip, drip, drip of Western prosecutions, pursuant to universal jurisdiction, it’s really difficult to envision the normalization of the regime.”

Before the Syrian Revolution, Mustafa was a trial lawyer, living and working in Al-Rastan, a suburb of the central city of Homs. He and his wife, Rula, had three small children, and Rula was pregnant with the fourth. In early 2011, when Syrians took to the streets to protest against the regime—which had ruled for almost half a century—Assad declared that anyone who did not contribute to “burying sedition” was “a part of it.” Suddenly Mustafa was caught in a delicate position, since many of Rula’s male relatives were military officers.

Her father and her uncles had joined the Syrian armed forces as young men, and served Assad’s father for many years before they served him. In the mid-nineties, Assad’s older brother died in a car crash, and he was called back from his studies in London and sent to a military academy in Homs. Eventually, he joined a staff officers’ course, where Anwar Saadeddin—then a colonel and a military engineer—says he spent a year and a half in his class.

Assad became President in 2000, after his father died, and for the next decade Saadeddin carried on with his duties without complaint. In 2003, Saadeddin was promoted to the rank of brigadier general. At the outset of the revolution, his younger son was a lieutenant, and he was two years from retirement.

Mustafa and Rula’s fourth child was born on April 5, 2011. Three days later, security forces shot a number of protesters in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs, including a disabled man, who was unable to run away. They dragged him from the site and returned his mutilated corpse to his family the following evening. From then on, Homs was the site of some of the largest anti-regime protests—and the most violent crackdown.

On April 19th, thousands of people gathered for a sit-in beneath a clock tower. At about midnight, officers warned that anyone who didn’t leave voluntarily would be removed by force. A couple of hours passed; a thousand people remained. At dawn, the people of Homs awoke to traces of a massacre. A witness later reported that religious leaders who had stayed to treat the wounded and to tend to the dead were summarily executed. Several others recalled that the bodies were removed with dump trucks, and that the blood of the dead and wounded was washed away with hoses.

The day after the massacre, according to documents that were later captured from Assad’s highest-level security committee, the regime decided to embark on a “new phase” in the crackdown, to “demonstrate the power and capacity of the state.” Nine days later, regime forces killed at least nineteen protesters in Al-Rastan, where Mustafa and Rula lived. Mustafa wasn’t involved in politics or human-rights work, beyond discussions of basic democratic reforms, but he was appalled by the overtly criminal manner in which security forces and associated militias carried out their campaign with impunity. Locals formed neighborhood-protection units, and soon took up arms against the state.

A few months later, Mustafa briefly sneaked out of Syria to attend a training session in Turkey, led by Bill Wiley, a Canadian war-crimes investigator who had previously worked for various tribunals and the International Criminal Court. Wiley, and others in his world, had noticed a jurisdictional gap in accountability for Syria and had begun casting about for Syrian lawyers who might be up for a perilous, but worthy, task. Although there was no tribunal set up for Syria, and Russia and China had blocked efforts to refer Syria to the I.C.C., Wiley and his associates had reasoned that the process of collecting evidence is purely a matter of risk tolerance and logistics. The work of criminal investigators is different from that of human-rights N.G.O.s: groups like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch produce and disseminate reports on horrific violations and abuse, but Wiley trained Mustafa and the other Syrians in attendance to collect the kind of evidence that could allow prosecutors to assign individual criminal responsibility to senior military and intelligence officers. A video showing tanks firing on unarmed protesters might influence public opinion, but a pile of military communications that proved which commanders were in charge of the operation could one day land someone in jail.

“The first task was to ferret out primary-source material—documents, in particular, generated by the regime,” Wiley told me. “We were looking for prima-facie evidence, not intelligence product or information to inform the public.”

Mustafa instantly grasped the urgency of the project. By day, he carried on with his law practice. But, in secret, he started building up sources within the armed opposition. As they captured new territory, he would go into security and intelligence facilities, box up documents, and move them to secret locations, like farmhouses or caves, farther from the confrontation lines.

“By 2012, we had already started to get some structure,” Wiley recalled. He secured funding from Western governments, and eventually the group settled on a name: the Commission for International Justice and Accountability. “We had our guys in Raqqa, Idlib, Aleppo, and so forth—at least one guy in all the key areas,” he said. From there, the cija built out each team—between two and four individuals, working under the head of each provincial cell. “And Mustafa was our core guy in Homs.”

Anwar Saadeddin soon found himself wielding his position in order to rescue relatives who were caught up in the conflict. His younger son, an Army lieutenant, was detained by military operatives on the outskirts of Damascus, after another officer in his brigade reported him for watching Al Arabiya and Al Jazeera. According to an internal military communication, which was later captured by the cija, Assad believed that foreign reporting on Syria amounted to “psychological warfare aimed at creating a state of internal chaos.”

When Saadeddin’s son was detained, he recalled, “I interfered just to decrease the detention period to thirty days.” Soon afterward, he learned that Mustafa was a target of military intelligence in Homs, where the local facility, Branch 261, was headed by one of Saadeddin’s friends: Mohammed Zamrini.

Mustafa wasn’t calling for an armed rebellion, and, at the time, neither the regime nor his father-in-law knew of his connection to Wiley and the cija. But rebel factions were active in Al-Rastan, and Mustafa was known to have urged them not to destroy any public establishments. To hard-liners in the regime, such interaction was considered tantamount to collaboration. “So I went with Mustafa to the branch,” Saadeddin told me. Zamrini agreed to detain him as a formality—for about twelve hours, with light interrogations and no torture or abuse—so that he could essentially cross Mustafa off the list.

In the next few months, the security situation rapidly deteriorated. The Army encircled rebellious neighborhoods near Homs and shelled them to the ground. Saadeddin’s son, who was serving near Damascus, was arrested a second time, and in order to get him released Saadeddin had to supplicate himself in the office of Assef Shawkat, Assad’s brother-in-law and the deputy minister of defense. In Homs, Saadeddin started driving Mustafa to and from work in his light-blue Kia; as a brigadier general, he could move passengers through checkpoints without them being searched or arrested.

But Saadeddin was beginning to find his position untenable. He sensed that the regime’s policy of total violence would lead to the destruction of the country. That spring, he began to share his fears and frustrations with close colleagues and friends, including the commander of his son’s brigade. But it was a perilous game: Assad’s highest-level security committee had instructed the heads of regional security branches to hunt down “security agents who are irresolute or unenthusiastic” in carrying out their duties. According to a U.N. inquiry, some officers were detained and tortured for having “attempted to spare civilians” on whom they had been ordered to fire.

That spring, Saadeddin’s car was stopped at one of the checkpoints that ordinarily waved him through. It was the first time that his position served not as protection against interrogation but as a reason to question his loyalty. The regime was quickly losing territory, and as the conflict spiralled out of control many senior officers found themselves approaching the limits of their willingness to go along. He and his brothers had “reached a point where we would either stand by the regime and have to take part in atrocities, or we would have to defect,” he told me.

That July, Saadeddin gathered his brothers, his sons, two nephews, and several other military officers in front of a small camera, somewhere near the Turkish-Syrian border. Dressed in his uniform, he announced that the army to which he had pledged his allegiance some four decades earlier had “deviated from its mission” and turned on its citizens instead. To honor the Syrian public’s “steadfastness in the face of barbaric assaults by Assad’s bloody gangs, we have decided to defect from the Army,” he said. It was one of the largest mass defections of Syrian officers, and his plan was to take a leading role in the rebellion—to fight for freedom “until martyrdom or victory.” In response, Saadeddin told me, their former colleagues sent troops to destroy their houses and those of their family members. They expropriated their land and killed several of their relatives.

By now, the regime had ceded swaths of Syria’s border with Turkey to various rebel forces. Saadeddin moved his family across the border and into a refugee camp that the Turkish government had set up for military and intelligence officers who defected. Then he went back to Syria, to try to bring some order and unity to the rebel factions that were battling his former colleagues.

But Mustafa and his family stayed behind in Al-Rastan, which was now firmly in rebel hands. The regime’s loss of control at the Turkish border meant that the cija could start moving its captured documents out of the country.

“It was complicated, reaching the border, because the confrontation lines were so fluid,” Wiley recalled. “And there were multiple bodies who were overtly hostile to cija”—not only the regime but also a growing number of extremist groups who were suspicious of anyone working for a Western N.G.O. During the first document extraction, a courier was shot and injured. During the next, another courier vanished with a suitcase full of documents. “Just fucking disappeared,” Wiley said. “Probably thought he could sell them.” Mustafa recruited a cousin to transport some files to Turkey. But, after the delivery, on the way back to Al-Rastan, the cousin took a minibus, and the vehicle was ambushed by regime troops. “He was shot, but it was unclear if he was wounded or dead when they took him away,” another Syrian cija investigator, whom I’ll call Omar, told me. For the next several weeks, regime agents blackmailed Mustafa, saying that for twenty thousand dollars they would release his cousin from custody. But, when Mustafa asked for proof of life, they failed to provide it—suggesting that the cousin had already died in custody.

By now, Wiley had issued new orders for the extraction process. “I said, ‘O.K., there needs to be a plan, and I need to know what the plan is,’ ” he recalled. “ ‘How are you getting from A to B? What risks are there between point A and point B? And how are you going to ameliorate those risks?’ As opposed to just throwing the shit in the car and going, ‘Well, God decides.’ ”

Saadeddin Spent Much of the next eighteen months trying to organize disparate rebel groups into a unified command. He travelled all over northern Syria, as rebels took new ground, and met with all manner of revolutionaries—from secular defectors to hard-line field commanders. By the summer of 2013, the regime had ceded control of most of northern Syria. But there was little cohesion between the rebel factions, and isis and Al Qaeda had come to exploit the power vacuum in rebel territory. At some point, Saadeddin recalled, he scolded a Tunisian isis commander for arousing sectarian and ethnic tensions, and imposing extremism onto local communities. “He responded that I was an apostate, and suggested that I should be killed,” Saadeddin told me.

In Al-Rastan, a regime shell penetrated the walls of Mustafa’s house, but it didn’t explode. At that point, Rula and the children moved to Reyhanli, a small Turkish village that is so close to the border that you can eat at a kebab shop there while watching sheep graze in Syria. It was also a short drive from the defected officers’ camp, where Rula’s mother and several other relatives were living. But Mustafa stayed behind, to carry out his investigative work for the cija.

“When new areas were liberated, the security branches were raided, and many people took files,” Omar recalled. Some of them didn’t grasp the significance of the files; at least one soldier burned them for warmth. “But most people knew the documents would be useful, someday—they just didn’t know what to do with them. So they just kept them. And the challenge was in identifying who had what, where.”

But, before long, Omar continued, “Mustafa built a wide network of contacts in rebel territory. Word got out that he was collecting documents, and so eventually people would refer others who had taken documents to him.” Sometimes he encountered a reluctance to turn over the originals, until he shared with them the outlines of the cija’s objective and paths to accountability. “At that point, they would usually relent, understanding that his use for them was the best use.”

As his profile in rebel territory grew, Mustafa remained highly secretive. But, from time to time, he asked his father-in-law for introductions to other defected military and intelligence officers. By now, Saadeddin recalled, “I knew the nature of his work, but I didn’t discuss it with him.” There was an understanding that it was best to compartmentalize any sensitive information, for the sake of the family. “Sometimes my wife didn’t even know what I was doing,” Saadeddin said. “But I do know that, at a certain point, through his interviews, Mustafa came to know these defected officers even better than I did.”

In 2014, Wiley restructured the cija’s Syrian team; as deputy chief of investigations, Mustafa now presided over all the group’s provincial cells. “He was very good at finding documents, and he understood evidence and law,” Wiley said. “But he was also respected by his peers. And he had a natural empathy, which translated into him being a very good interviewer” of victims and perpetrators alike. According to Omar, Mustafa often cut short his appearances at social gatherings, citing family or work. “I know it’s a cliché, but he really was a family guy,” Wiley told me. “But where he excelled in our view—because we don’t need a bunch of good family guys, to be blunt—is that he could execute.”

That July, Assad’s General Intelligence Directorate apparently learned of the cija’s activities, long before the group had been named in the press. In a document that was sent to at least ten intelligence branches—and which was later captured by the cija—the directorate identified Mustafa as “vice-chairman” of the group, and also listed the names of the leading investigators within each of the cija’s governorate cells. At the bottom of the document, the head of the directorate handwrote orders to “arrest them along with their collaborators.”

By now, Western governments, which had pledged to support secular opposition groups, found the situation in northern Syria unpalatable; there was no way to guarantee that weapons given to a secular armed faction would not end up in jihadi hands. Saadeddin had begun to lose hope in the revolution—a sentiment that grew only stronger when Assad’s forces killed more than a thousand civilians with sarin gas, and the Obama Administration backed away from its “red-line” warning of retaliation. “At that point, I lost all faith in the international community,” Saadeddin told me. “I felt that they didn’t want Syria to become liberated—they wanted Syria to stay as it was.” He moved into the defected officers’ camp in southern Turkey, where he remained—feeling “rotten,” consumed by a sense of impotence and frustration—for most of the next decade.

I First Came Into Contact with the cija late in the summer of 2015. By that point, the group had smuggled more than six hundred thousand documents out of Syria, and had prepared a legal brief that assigned individual criminal responsibility for the torture and murder of thousands of people in detention centers to senior members of the Syrian security-intelligence apparatus—including Assad himself. In the following years, the cija expanded its operations to Iraq, Myanmar, Libya, and Ukraine. But Syria was always at the core.

“In terms of the opposition overrunning regime territory—that effectively ceased in September, 2015, when the Russians came in,” Wiley recalled. In the following years, Russian fighter jets pummelled areas under rebel control, while fighters from Russian mercenary groups, Iranian militias, and Hezbollah reinforced Assad’s troops on the ground. In time, the confrontation lines settled, with the country effectively carved into areas under regime, opposition, Turkish, and Kurdish control. But Mustafa and other investigators continued to identify troves of documents, scattered among various hidden sites. “We’d acquire them from different places, and then concentrate them,” Wiley said. Omar told me that it was best to keep files as close to the border as possible, to limit the chance of their being destroyed in the event that the regime took back ground. “Mustafa would sometimes spend a week or more prepping for document extractions,” Omar said. “He would sleep in tents,” in camps filled with other displaced civilians, “while he waited for the right moment to move the files closer to the border.”

At the cija’s headquarters, in Western Europe, the organization built cases against senior intelligence officers, like the double agent Khaled al-Halabi, and provided evidence to European prosecutors who were investigating lesser targets all over the continent. In recent years, Western prosecutors and police agencies have sent hundreds of requests for investigative assistance to the cija headquarters; when the answers can’t be found in the existing files, analysts refer the inquiries, via Mick, the Australian in southern Turkey, to the Syrians on the ground. “We wouldn’t tell them who’s asking, or who the suspects are,” Wiley said. “We’d just say, ‘O.K., we’re interested in witnesses to a particular crime base’—a security-intelligence facility, a static killing, an execution, that kind of thing. And then they would identify witnesses and do a screening interview.” When requests came through, Mick told me, “Mustafa was usually the first team member that I went to, because his networks were so good.”

During the peak years of the pandemic, Mustafa identified and collected witness statements against a trio of Syrian isis members who had been active in a remote village in the deserts of central Syria and were now scattered across Western Europe. All three men were arrested after his death.

Perhaps Mustafa’s most enduring contribution to the cija’s casework is found in one of the group’s most comprehensive, confidential investigative briefs, which I read at the headquarters this spring. It’s a three-hundred-page document, with almost thirteen hundred footnotes, establishing individual criminal responsibility for war crimes carried out during the regime’s 2012 siege of Baba Amr, a neighborhood in the southern part of Mustafa’s home city, Homs. Other cases have centered on torture in detention facilities; this is the first Syrian war-crimes brief that focusses on the conduct of hostilities, and it spells out, in astonishing and historic detail, a litany of crimes, ranging from indiscriminate shelling to mass executions of civilians who were rounded up and killed in warehouses and factories as regime forces swept through. The Homs Brief—for which Mustafa collected much of the underlying evidence—also assigns criminal responsibility to individual commanders within the Syrian Army’s 18th Tank Division, which carried out the assault.

“He thought he was contributing to a better Syria,” Wiley said. “When—and what it would look like—was unsure. But he believed in what he was doing. He could have fucked off years ago. We probably could have gotten him to Canada. We talked about it, because one of his daughters had a congenital heart issue.” Nevertheless, he stayed.

Last year, Mustafa bought an apartment on the eleventh floor of a new tower block in Antakya. Rula’s aunt moved into the same building, a couple of stories below. Her parents left the defected officers’ camp and moved into another apartment block, a short walk up the road. A few months later, Mick recalled, “Mustafa said to me, ‘When I’m at home with my family, it doesn’t matter what’s happening outside—it doesn’t matter if there’s a war. When I’m at home, I’m at peace.’ ”

Last December, Mick was visiting Mustafa’s apartment when the floor began to shake. “It spooked me—it was my first time feeling this kind of tremor,” Mick recalled. Mustafa laughed and said that they happen “all the time.” Then he went to check on Rula and the children, who reported that they hadn’t even felt it.

A couple of months later, Mick awoke to news of the catastrophic earthquake and tried to call members of his Syrian team. But the cellular networks were down in Antakya, and it was impossible for him to travel there, because the local airport’s runway had buckled, along with many local roads.

Saadeddin’s sister was dug out of the complex alive; her husband survived as well, but died in a hospital soon afterward, without anyone in the family knowing where he was. On the fourth day of search-and-rescue operations, Mustafa’s passport was found in the rubble. Then his laptop, then his wife’s handbag. “When they found the bodies,” Omar said, “Mustafa was hugging his daughter, his wife was hugging their son, and the other two children were hugging each other.”

Omar spent the next several days sleeping in his car, along with his wife and six children. Thousands of aftershocks shook the region, and, by the time I met with him, a few hundred metres from the Syrian border, he was so rattled that he reacted to everyday sounds as if they might signal a building’s collapse. His breath was short and his eyes welled with tears; Mustafa had been one of his best friends, and he had also lost eleven relatives to the quake, all of whom had been displaced from the same village in northern Syria. Then his young son walked into the room, and he turned his head. “We try to hide from our children our fear and our grief, so that they don’t feel as if we are weak,” he said.

A few weeks after the earthquake, there was an empty seat at a prestigious international-criminal-investigations course, in the Hague. Mustafa had been scheduled to attend. “We can mitigate the effects of war, except bad luck, but we didn’t factor an earthquake into the plan, institutionally,” Wiley told me. Mick coördinated humanitarian assistance for displaced investigators, and, as Wiley put it, “the operational posture came back really quickly.” Omar has now taken over Mustafa’s leadership duties. “Keep in mind how resilient this cadre is,” Wiley continued. “They’re already all refugees, perhaps with the rare exception. They had already lost their homes, lost all their stuff.”

It was the middle of April, more than two months after the quake. Much of Antakya had been completely flattened, and what still stood was cracked and broken, completely abandoned, and poised to collapse. Mick and I made our way through the old city on foot; the alleys were too narrow for digging equipment to go through, and so we found ourselves climbing over rubble, as if the buildings had fallen the day before. The pets of those entombed in the collapsed buildings followed us, still wearing their collars—bewildered, brand-new strays. ♦

#Syria 🇸🇾 | Earthquakes | Türkiye 🇹🇷 | War Crimes#President Bashar al-Assad#War-Crimes Investigator#Secret Life#Anonymous Death#History#Ben Taub#The New Yorker#Mustafa | Trial Lawyer

1 note

·

View note

Text

This is very important. In Crimea, russians, again, start to use fake criminal investigations to incarcerate Crimean Tatars. This is not new - but it is the new mass wave of searches on trumped-up charges and arrests.

Translation of the thread below.

1/9 Mass searches in Crimea

10 Crimean Tatar families. 10 homes, where russian "security forces" broke into at dawn. What do we know about the newe wave of mass searches on the Crimean peninsula?

2/9 4 activists of "Crimean Solidarity", Bakhchysarai, as well as 6 religion leaders and activists from Dzhankoy district, became victims of the rampage of the occupatoinal forces.

Among them, the former Imam Remzi Kurtnezirov, who has a severe disability.

3/9 "Security forces" behaved themselves very rudely, despite the presence of elderly and small children.

Over the course of the searches, they took documents, tech, and literature. Moreover, the relatieves of the detained people state that the books were planted.

4/9 FSB agents, when asked by the relatives, replied that they are looking for weapons and illicit chemicals.

The men are charged with Article 205.5 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation - the same one that the Hizb ut-Tahrir cases are fabricated under.

5/9 After the searches, Crimean Tatars were taken to FSB HQ in Simferopol.

Currently, some of them were allowed a lawyer but the pre-trial detention measure was not choosen yet.

6/9 Names of the detained: Rustem Osmanov, Aziz Azizov, Memet Lumanov, Mustafa Abduramanov, Remzi Kurtnezirov, Vakhid Mustafayev, Ali Mamutov, Arsen Kashka, Enver Khalilayev, Nariman Ametov

7/9

According to preliminary information, this is the third largest wave of searches on the alleged involvement in Hizb ut-Tahrir.

The most massive searches took place in March 2019, when 24 Crimean Tatars were targeted.

8/9 CrimeaSOS analyst Yevhen Yaroshenko notes that detentions in the "Hizb ut-Tahrir cases" in Crimea are intensified approximately once every six months.

This is due to the targeted plan for certain categories of "cases" that intelligence officers have to fulfill.

9/9 Repressions against Crimean Tatars are one of the principles of russia's criminal policy on the peninsula.

In order to stop the occupiers, we must respond firmly to every manifestation of lawlessness and effectively oppose it

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

It was 4:17 A.M. on February 6th in Antakya, an ancient Turkish city near the Syrian border, when the earth tore open and people’s beds began to shake. On the third floor of an apartment in the Ekinci neighborhood, Anwar Saadeddin, a former brigadier general in the Syrian Army, awoke to the sounds of glass breaking, cupboard doors banging, and jars of tahini and cured eggplant spilling onto the floor. He climbed out of bed, but, for almost thirty seconds, he was unable to keep his footing; the building was moving side to side. When the earthquake subsided, he tried to call his daughter Rula, who lived down the road, but the cellular network was down.

Thirty seconds after the first quake, the building started moving again, this time up and down, with such violence that an exterior wall sheared open, and rain started pouring in. The noise was tremendous—concrete splitting, rebar bending, plates shattering, neighbors screaming. When the shaking stopped, about a minute later, Saadeddin, who is in his late sixties, and his wife walked down three flights of stairs, dressed in pajamas and sandals, and went out into the cold.

“All of Antakya was black—there was no electricity anywhere,” Saadeddin recalled. Thousands of the city’s buildings had collapsed. Survivors spilled into the streets, crowding rubble-strewn alleyways and searching for open ground, as minarets toppled and glass shards fluttered down from tower blocks. The general and his wife set off in the direction of the building where Rula lived, with her husband, Mustafa, and their four children.

A third quake shook the ground. When Saadeddin made it to his daughter’s apartment block, flashes of lighting illuminated what was now a fourteen-story grave. The building—which had been completed less than two years earlier—had twisted as it toppled over, crushing many of the residents. Saadeddin felt his body drained of all emotion, almost as if it didn’t belong to him.

Saadeddin was not the only person searching for Rula and her family. For the past decade, her husband, Mustafa, had quietly served as the deputy chief of Syria investigations for the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, a group that has captured more than a million pages of documents from Syrian military and intelligence facilities. Using these files, lawyers at the CIJA have prepared some of the most comprehensive war-crimes cases since the Nuremberg trials, targeting senior Syrian regime officers—including the President, Bashar al-Assad. After the earthquake, the group directed its investigative focus into a search-and-rescue operation for members of its own Syrian team, many of whom had been displaced to southern Turkey after more than a decade of war. By the end of the third day, nearly everyone was accounted for. Two investigators had lost children; one of them had also lost his wife. But Mustafa was still missing.

For as long as Mustafa had been working for the CIJA, the group had kept his identity secret—even after it captured a Syrian intelligence document that showed that the regime knew about his investigative work and was actively hunting him down. “He was probably my best investigator,” Mustafa’s supervisor, an Australian who goes by Mick, told me, during a recent visit to the Turkish-Syrian border. Documents that Mustafa obtained, and witness interviews that he conducted, have assisted judicial proceedings in the United States, France, Belgium, Germany, and several other European jurisdictions. According to a CIJA estimate, Mustafa “either directly obtained or supported in the acquisition” of more than two hundred thousand pages of internal Syrian regime documents, likely making him—by sheer volume of evidence collected—the most prolific war-crimes investigator in history.

Twelve years into the Syrian war, at least half the population has been displaced, often multiple times, under varied circumstances of individual tragedy. No one knows the actual death toll—not even to the nearest hundred thousand. And yet the Syrian regime’s crimes continue apace. “The prisons are full,” Bill Wiley, the CIJA’s founder and executive director, told me. “All the offenses that started being carried out at scale in 2011 are still being perpetrated. Unlawful detention, physical abuse amounting to torture, extrajudicial killing, sexual offenses—all of that continues. War crimes on the battlefield, particularly in the context of aerial operations. There are still chemical attacks. It all continues. But, as long as there’s the drip, drip, drip of Western prosecutions, pursuant to universal jurisdiction, it’s really difficult to envision the normalization of the regime.”

Before the Syrian revolution, Mustafa was a trial lawyer, living and working in Al-Rastan, a suburb of the central city of Homs. He and his wife, Rula, had three small children, and Rula was pregnant with the fourth. In early 2011, when Syrians took to the streets to protest against the regime—which had ruled for almost half a century—Assad declared that anyone who did not contribute to “burying sedition” was “a part of it.” Suddenly Mustafa was caught in a delicate position, since many of Rula’s male relatives were military officers.

Her father and her uncles had joined the Syrian armed forces as young men, and served Assad’s father for many years before they served him. In the mid-nineties, Assad’s older brother died in a car crash, and he was called back from his studies in London and sent to a military academy in Homs. Eventually, he joined a staff officers’ course, where Anwar Saadeddin—then a colonel and a military engineer—says he spent a year and a half in his class.

Assad became President in 2000, after his father died, and for the next decade Saadeddin carried on with his duties without complaint. In 2003, Saadeddin was promoted to the rank of brigadier general. At the outset of the revolution, his younger son was a lieutenant, and he was two years from retirement.

Mustafa and Rula’s fourth child was born on April 5, 2011. Three days later, security forces shot a number of protesters in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs, including a disabled man, who was unable to run away. They dragged him from the site and returned his mutilated corpse to his family the following evening. From then on, Homs was the site of some of the largest anti-regime protests—and the most violent crackdown.

On April 19th, thousands of people gathered for a sit-in beneath a clock tower. At about midnight, officers warned that anyone who didn’t leave voluntarily would be removed by force. A couple of hours passed; a thousand people remained. At dawn, the people of Homs awoke to traces of a massacre. A witness later reported that religious leaders who had stayed to treat the wounded and to tend to the dead were summarily executed. Several others recalled that the bodies were removed with dump trucks, and that the blood of the dead and wounded was washed away with hoses.

The day after the massacre, according to documents that were later captured from Assad’s highest-level security committee, the regime decided to embark on a “new phase” in the crackdown, to “demonstrate the power and capacity of the state.” Nine days later, regime forces killed at least nineteen protesters in Al-Rastan, where Mustafa and Rula lived. Mustafa wasn’t involved in politics or human-rights work, beyond discussions of basic democratic reforms, but he was appalled by the overtly criminal manner in which security forces and associated militias carried out their campaign with impunity. Locals formed neighborhood-protection units, and soon took up arms against the state.

A few months later, Mustafa briefly sneaked out of Syria to attend a training session in Turkey, led by Bill Wiley, a Canadian war-crimes investigator who had previously worked for various tribunals and the International Criminal Court. Wiley, and others in his world, had noticed a jurisdictional gap in accountability for Syria and had begun casting about for Syrian lawyers who might be up for a perilous, but worthy, task. Although there was no tribunal set up for Syria, and Russia and China had blocked efforts to refer Syria to the I.C.C., Wiley and his associates had reasoned that the process of collecting evidence is purely a matter of risk tolerance and logistics. The work of criminal investigators is different from that of human-rights N.G.O.s: groups like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch produce and disseminate reports on horrific violations and abuse, but Wiley trained Mustafa and the other Syrians in attendance to collect the kind of evidence that could allow prosecutors to assign individual criminal responsibility to senior military and intelligence officers. A video showing tanks firing on unarmed protesters might influence public opinion, but a pile of military communications that proved which commanders were in charge of the operation could one day land someone in jail.

“The first task was to ferret out primary-source material—documents, in particular, generated by the regime,” Wiley told me. “We were looking for prima-facie evidence, not intelligence product or information to inform the public.”

Mustafa instantly grasped the urgency of the project. By day, he carried on with his law practice. But, in secret, he started building up sources within the armed opposition. As they captured new territory, he would go into security and intelligence facilities, box up documents, and move them to secret locations, like farmhouses or caves, farther from the confrontation lines.

“By 2012, we had already started to get some structure,” Wiley recalled. He secured funding from Western governments, and eventually the group settled on a name: the Commission for International Justice and Accountability. “We had our guys in Raqqa, Idlib, Aleppo, and so forth—at least one guy in all the key areas,” he said. From there, the CIJA built out each team—between two and four individuals, working under the head of each provincial cell. “And Mustafa was our core guy in Homs.”

Anwar Saadeddin soon found himself wielding his position in order to rescue relatives who were caught up in the conflict. His younger son, an Army lieutenant, was detained by military operatives on the outskirts of Damascus, after another officer in his brigade reported him for watching Al Arabiya and Al Jazeera. According to an internal military communication, which was later captured by the CIJA, Assad believed that foreign reporting on Syria amounted to “psychological warfare aimed at creating a state of internal chaos.”

When Saadeddin’s son was detained, he recalled, “I interfered just to decrease the detention period to thirty days.” Soon afterward, he learned that Mustafa was a target of military intelligence in Homs, where the local facility, Branch 261, was headed by one of Saadeddin’s friends: Mohammed Zamrini.

Mustafa wasn’t calling for an armed rebellion, and, at the time, neither the regime nor his father-in-law knew of his connection to Wiley and the CIJA. But rebel factions were active in Al-Rastan, and Mustafa was known to have urged them not to destroy any public establishments. To hard-liners in the regime, such interaction was considered tantamount to collaboration. “So I went with Mustafa to the branch,” Saadeddin told me. Zamrini agreed to detain him as a formality—for about twelve hours, with light interrogations and no torture or abuse—so that he could essentially cross Mustafa off the list.

In the next few months, the security situation rapidly deteriorated. The Army encircled rebellious neighborhoods near Homs and shelled them to the ground. Saadeddin’s son, who was serving near Damascus, was arrested a second time, and in order to get him released Saadeddin had to supplicate himself in the office of Assef Shawkat, Assad’s brother-in-law and the deputy minister of defense. In Homs, Saadeddin started driving Mustafa to and from work in his light-blue Kia; as a brigadier general, he could move passengers through checkpoints without them being searched or arrested.

But Saadeddin was beginning to find his position untenable. He sensed that the regime’s policy of total violence would lead to the destruction of the country. That spring, he began to share his fears and frustrations with close colleagues and friends, including the commander of his son’s brigade. But it was a perilous game: Assad’s highest-level security committee had instructed the heads of regional security branches to hunt down “security agents who are irresolute or unenthusiastic” in carrying out their duties. According to a U.N. inquiry, some officers were detained and tortured for having “attempted to spare civilians” on whom they had been ordered to fire.

That spring, Saadeddin’s car was stopped at one of the checkpoints that ordinarily waved him through. It was the first time that his position served not as protection against interrogation but as a reason to question his loyalty. The regime was quickly losing territory, and as the conflict spiralled out of control many senior officers found themselves approaching the limits of their willingness to go along. He and his brothers had “reached a point where we would either stand by the regime and have to take part in atrocities, or we would have to defect,” he told me.

That July, Saadeddin gathered his brothers, his sons, two nephews, and several other military officers in front of a small camera, somewhere near the Turkish-Syrian border. Dressed in his uniform, he announced that the army to which he had pledged his allegiance some four decades earlier had “deviated from its mission” and turned on its citizens instead. To honor the Syrian public’s “steadfastness in the face of barbaric assaults by Assad’s bloody gangs, we have decided to defect from the Army,” he said. It was one of the largest mass defections of Syrian officers, and his plan was to take a leading role in the rebellion—to fight for freedom “until martyrdom or victory.” In response, Saadeddin told me, their former colleagues sent troops to destroy their houses and those of their family members. They expropriated their land and killed several of their relatives.

By now, the regime had ceded swaths of Syria’s border with Turkey to various rebel forces. Saadeddin moved his family across the border and into a refugee camp that the Turkish government had set up for military and intelligence officers who defected. Then he went back to Syria, to try to bring some order and unity to the rebel factions that were battling his former colleagues.

But Mustafa and his family stayed behind in Al-Rastan, which was now firmly in rebel hands. The regime’s loss of control at the Turkish border meant that the CIJA could start moving its captured documents out of the country.

“It was complicated, reaching the border, because the confrontation lines were so fluid,” Wiley recalled. “And there were multiple bodies who were overtly hostile to CIJA”—not only the regime but also a growing number of extremist groups who were suspicious of anyone working for a Western N.G.O. During the first document extraction, a courier was shot and injured. During the next, another courier vanished with a suitcase full of documents. “Just fucking disappeared,” Wiley said. “Probably thought he could sell them.” Mustafa recruited a cousin to transport some files to Turkey. But, after the delivery, on the way back to Al-Rastan, the cousin took a minibus, and the vehicle was ambushed by regime troops. “He was shot, but it was unclear if he was wounded or dead when they took him away,” another Syrian CIJA investigator, whom I’ll call Omar, told me. For the next several weeks, regime agents blackmailed Mustafa, saying that for twenty thousand dollars they would release his cousin from custody. But, when Mustafa asked for proof of life, they failed to provide it—suggesting that the cousin had already died in custody.

By now, Wiley had issued new orders for the extraction process. “I said, ‘O.K., there needs to be a plan, and I need to know what the plan is,’ ” he recalled. “ ‘How are you getting from A to B? What risks are there between point A and point B? And how are you going to ameliorate those risks?’ As opposed to just throwing the shit in the car and going, ‘Well, God decides.’ ”

Saadeddin spent much of the next eighteen months trying to organize disparate rebel groups into a unified command. He travelled all over northern Syria, as rebels took new ground, and met with all manner of revolutionaries—from secular defectors to hard-line field commanders. By the summer of 2013, the regime had ceded control of most of northern Syria. But there was little cohesion between the rebel factions, and ISIS and Al Qaeda had come to exploit the power vacuum in rebel territory. At some point, Saadeddin recalled, he scolded a Tunisian ISIS commander for arousing sectarian and ethnic tensions, and imposing extremism onto local communities. “He responded that I was an apostate, and suggested that I should be killed,” Saadeddin told me.

In Al-Rastan, a regime shell penetrated the walls of Mustafa’s house, but it didn’t explode. At that point, Rula and the children moved to Reyhanli, a small Turkish village that is so close to the border that you can eat at a kebab shop there while watching sheep graze in Syria. It was also a short drive from the defected officers’ camp, where Rula’s mother and several other relatives were living. But Mustafa stayed behind, to carry out his investigative work for the CIJA.

“When new areas were liberated, the security branches were raided, and many people took files,” Omar recalled. Some of them didn’t grasp the significance of the files; at least one soldier burned them for warmth. “But most people knew the documents would be useful, someday—they just didn’t know what to do with them. So they just kept them. And the challenge was in identifying who had what, where.”

But, before long, Omar continued, “Mustafa built a wide network of contacts in rebel territory. Word got out that he was collecting documents, and so eventually people would refer others who had taken documents to him.” Sometimes he encountered a reluctance to turn over the originals, until he shared with them the outlines of the CIJA’s objective and paths to accountability. “At that point, they would usually relent, understanding that his use for them was the best use.”

As his profile in rebel territory grew, Mustafa remained highly secretive. But, from time to time, he asked his father-in-law for introductions to other defected military and intelligence officers. By now, Saadeddin recalled, “I knew the nature of his work, but I didn’t discuss it with him.” There was an understanding that it was best to compartmentalize any sensitive information, for the sake of the family. “Sometimes my wife didn’t even know what I was doing,” Saadeddin said. “But I do know that, at a certain point, through his interviews, Mustafa came to know these defected officers even better than I did.”

In 2014, Wiley restructured the CIJA’s Syrian team; as deputy chief of investigations, Mustafa now presided over all the group’s provincial cells. “He was very good at finding documents, and he understood evidence and law,” Wiley said. “But he was also respected by his peers. And he had a natural empathy, which translated into him being a very good interviewer” of victims and perpetrators alike. According to Omar, Mustafa often cut short his appearances at social gatherings, citing family or work. “I know it’s a cliché, but he really was a family guy,” Wiley told me. “But where he excelled in our view—because we don’t need a bunch of good family guys, to be blunt—is that he could execute.”

That July, Assad’s General Intelligence Directorate apparently learned of the CIJA’s activities, long before the group had been named in the press. In a document that was sent to at least ten intelligence branches—and which was later captured by the CIJA—the directorate identified Mustafa as “vice-chairman” of the group, and also listed the names of the leading investigators within each of the CIJA’s governorate cells. At the bottom of the document, the head of the directorate handwrote orders to “arrest them along with their collaborators.”

By now, Western governments, which had pledged to support secular opposition groups, found the situation in northern Syria unpalatable; there was no way to guarantee that weapons given to a secular armed faction would not end up in jihadi hands. Saadeddin had begun to lose hope in the revolution—a sentiment that grew only stronger when Assad’s forces killed more than a thousand civilians with sarin gas, and the Obama Administration backed away from its “red-line” warning of retaliation. “At that point, I lost all faith in the international community,” Saadeddin told me. “I felt that they didn’t want Syria to become liberated—they wanted Syria to stay as it was.” He moved into the defected officers’ camp in southern Turkey, where he remained—feeling “rotten,” consumed by a sense of impotence and frustration—for most of the next decade.

I first came into contact with the CIJA late in the summer of 2015. By that point, the group had smuggled more than six hundred thousand documents out of Syria, and had prepared a legal brief that assigned individual criminal responsibility for the torture and murder of thousands of people in detention centers to senior members of the Syrian security-intelligence apparatus—including Assad himself. In the following years, the CIJA expanded its operations to Iraq, Myanmar, Libya, and Ukraine. But Syria was always at the core.

“In terms of the opposition overrunning regime territory—that effectively ceased in September, 2015, when the Russians came in,” Wiley recalled. In the following years, Russian fighter jets pummelled areas under rebel control, while fighters from Russian mercenary groups, Iranian militias, and Hezbollah reinforced Assad’s troops on the ground. In time, the confrontation lines settled, with the country effectively carved into areas under regime, opposition, Turkish, and Kurdish control. But Mustafa and other investigators continued to identify troves of documents, scattered among various hidden sites. “We’d acquire them from different places, and then concentrate them,” Wiley said. Omar told me that it was best to keep files as close to the border as possible, to limit the chance of their being destroyed in the event that the regime took back ground. “Mustafa would sometimes spend a week or more prepping for document extractions,” Omar said. “He would sleep in tents,” in camps filled with other displaced civilians, “while he waited for the right moment to move the files closer to the border.”

At the CIJA’s headquarters, in Western Europe, the organization built cases against senior intelligence officers, like the double agent Khaled al-Halabi, and provided evidence to European prosecutors who were investigating lesser targets all over the continent. In recent years, Western prosecutors and police agencies have sent hundreds of requests for investigative assistance to the CIJA headquarters; when the answers can’t be found in the existing files, analysts refer the inquiries, via Mick, the Australian in southern Turkey, to the Syrians on the ground. “We wouldn’t tell them who’s asking, or who the suspects are,” Wiley said. “We’d just say, ‘O.K., we’re interested in witnesses to a particular crime base’—a security-intelligence facility, a static killing, an execution, that kind of thing. And then they would identify witnesses and do a screening interview.” When requests came through, Mick told me, “Mustafa was usually the first team member that I went to, because his networks were so good.”

During the peak years of the pandemic, Mustafa identified and collected witness statements against a trio of Syrian ISIS members who had been active in a remote village in the deserts of central Syria and were now scattered across Western Europe. All three men were arrested after his death.

Perhaps Mustafa’s most enduring contribution to the CIJA’s casework is found in one of the group’s most comprehensive, confidential investigative briefs, which I read at the headquarters this spring. It’s a three-hundred-page document, with almost thirteen hundred footnotes, establishing individual criminal responsibility for war crimes carried out during the regime’s 2012 siege of Baba Amr, a neighborhood in the southern part of Mustafa’s home city, Homs. Other cases have centered on torture in detention facilities; this is the first Syrian war-crimes brief that focusses on the conduct of hostilities, and it spells out, in astonishing and historic detail, a litany of crimes, ranging from indiscriminate shelling to mass executions of civilians who were rounded up and killed in warehouses and factories as regime forces swept through. The Homs Brief—for which Mustafa collected much of the underlying evidence—also assigns criminal responsibility to individual commanders within the Syrian Army’s 18th Tank Division, which carried out the assault.

“He thought he was contributing to a better Syria,” Wiley said. “When—and what it would look like—was unsure. But he believed in what he was doing. He could have fucked off years ago. We probably could have gotten him to Canada. We talked about it, because one of his daughters had a congenital heart issue.” Nevertheless, he stayed.

Last year, Mustafa bought an apartment on the eleventh floor of a new tower block in Antakya. Rula’s aunt moved into the same building, a couple of stories below. Her parents left the defected officers’ camp and moved into another apartment block, a short walk up the road. A few months later, Mick recalled, “Mustafa said to me, ‘When I’m at home with my family, it doesn’t matter what’s happening outside—it doesn’t matter if there’s a war. When I’m at home, I’m at peace.’ ”

Last December, Mick was visiting Mustafa’s apartment when the floor began to shake. “It spooked me—it was my first time feeling this kind of tremor,” Mick recalled. Mustafa laughed and said that they happen “all the time.” Then he went to check on Rula and the children, who reported that they hadn’t even felt it.

A couple of months later, Mick awoke to news of the catastrophic earthquake and tried to call members of his Syrian team. But the cellular networks were down in Antakya, and it was impossible for him to travel there, because the local airport’s runway had buckled, along with many local roads.

Saadeddin’s sister was dug out of the complex alive; her husband survived as well, but died in a hospital soon afterward, without anyone in the family knowing where he was. On the fourth day of search-and-rescue operations, Mustafa’s passport was found in the rubble. Then his laptop, then his wife’s handbag. “When they found the bodies,” Omar said, “Mustafa was hugging his daughter, his wife was hugging their son, and the other two children were hugging each other.”

Omar spent the next several days sleeping in his car, along with his wife and six children. Thousands of aftershocks shook the region, and, by the time I met with him, a few hundred metres from the Syrian border, he was so rattled that he reacted to everyday sounds as if they might signal a building’s collapse. His breath was short and his eyes welled with tears; Mustafa had been one of his best friends, and he had also lost eleven relatives to the quake, all of whom had been displaced from the same village in northern Syria. Then his young son walked into the room, and he turned his head. “We try to hide from our children our fear and our grief, so that they don’t feel as if we are weak,” he said.

A few weeks after the earthquake, there was an empty seat at a prestigious international-criminal-investigations course, in the Hague. Mustafa had been scheduled to attend. “We can mitigate the effects of war, except bad luck, but we didn’t factor an earthquake into the plan, institutionally,” Wiley told me. Mick coördinated humanitarian assistance for displaced investigators, and, as Wiley put it, “the operational posture came back really quickly.” Omar has now taken over Mustafa’s leadership duties. “Keep in mind how resilient this cadre is,” Wiley continued. “They’re already all refugees, perhaps with the rare exception. They had already lost their homes, lost all their stuff.”

It was the middle of April, more than two months after the quake. Much of Antakya had been completely flattened, and what still stood was cracked and broken, completely abandoned, and poised to collapse. Mick and I made our way through the old city on foot; the alleys were too narrow for digging equipment to go through, and so we found ourselves climbing over rubble, as if the buildings had fallen the day before. The pets of those entombed in the collapsed buildings followed us, still wearing their collars—bewildered, brand-new strays.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is your boss tracking you while you work? Some Canadians are about to find out

If you're spending more time on YouTube than on Excel during your workday, there's software that may be flagging you as "unproductive" and sending that activity to your boss. That's the new reality as remote work is on the rise, causing more employers to monitor employees to see if they're slacking off. Near downtown Toronto's Union Station, a major commuter hub, workers like Fariha Chowdhury say they would like to know if their actions are being monitored.

Mustafa Kobari says companies that turn to these software solutions could be heading down a slippery slope. "Where does it stop? It's a little bit worrying." Some Canadian workers will now learn whether they're being tracked. Starting on Tuesday, Ontario employers with 25 or more employees will be required to have an electronic monitoring policy, and they have 30 days to disclose the information to staff.

It's part of the Working for Workers Act, and it makes the province the only one in Canada with legislation on employee monitoring. Quebec, Alberta, and British Columbia require employers to disclose data collection under privacy laws.

As the COVID-19 pandemic led to lockdowns and forced employees to work from home in droves, many employers implemented electronic monitoring systems without alerting their staff, said Mackenzie Irwin, an employment lawyer at Samfiru Tumarkin LLP in Toronto. The Ontario legislation applies to all employees using company-issued devices, whether the employer is tracking the GPS of a delivery truck driver or the emails of an office worker.

Irwin said the new rules are a good first step toward transparency. "Once we know what they are actually doing, then we'll have a better sense of whether those monitoring systems are breaching any other legislation."

But she said there is more work to be done because the legislation doesn't actually give employees any new rights to privacy or do much to discourage employers from overly intrusive monitoring. Still, Irwin said she expects employees to take a stand if they feel uncomfortable once they find out how much they are being monitored.

While it's difficult to nail down just how many companies are using employee tracking software, workplace surveillance "accelerated and expanded" in Canada during the pandemic, according to a report from the Cybersecure Policy Exchange at Toronto Metropolitan University. Tech firms like Time Doctor, Hubstaff, and Teramind are just a few that are seeing a growing demand for their monitoring software, which records keystrokes, listens back to phone calls, and even takes screenshots every 10 minutes.

Eli Sutton, vice president of global operations at U.S.-based Teramind, said his customers range from law firms and telecom companies to the government and the healthcare sector. In Canada, the company currently has about 300 active customers, and another 150 have signed up for a trial.

Sutton said his employer clients want to monitor employees for security reasons to prevent information from leaving the organization and for productivity reasons, as a way to understand how employees are spending their time when they're working remotely.

But Sutton agrees that it's up to employers to set boundaries to use technology effectively and not just focus on one employee's actions. "You definitely don't want to use it in the form of micromanagement. It's more about the end goal, not so much what they're doing every second of the day."

Some critics of employee monitoring software say it's actually not an accurate representation of employee performance because it doesn't capture other work that may be helpful to employers, such as talking to colleagues and mentoring co-workers.

If employees worry about being tracked, they may start rejecting those activities to protect their productivity, said Valerio De Stefano, a professor and Canada Research Chair in Innovation, Law and Society at Osgoode Hall Law School in Toronto.

He said companies could fare better by assessing workers based on output rather than on the time they spend on activities that the computer marks as work. Otherwise, employee monitoring software can often end up being counterproductive, De Stefano said.

0 notes

Photo

[From 2020]

Dersim's Kurdish lawyer, Ebru Timtik has passed away...

She left in silence yesterday afternoon to a hospital room where she had been transferred from prison following the deterioration of her condition. She left the 238th day of a hunger strike in which she called for a fair trial in a country, Turkey, where fairness and justice are non existent concepts. Especially if you are a woman. Especially if you're a human rights lawyer. Especially if you don't fold your back in front of a power that would like to shut your mouth.Thus died, Ebru Timtik, of hunger and injustice. Her heart stopped simply because she had nothing to pump in a body stripped of hunger anymore. She passed away defending her right to a fair trial, after being sentenced to 13 years, with 18 other lawyers like her, held for terrorism, only for defending other persons charged with the same crime. She died like Ibrahim and Helin and Mustafa from Grup Yorum, who died after 300 days of fasting to fight the same charge.

She died fighting with her body, to the extreme, a battle that in Erdogan's Turkey is no longer possible to fight with a word, a vote, a street protest. She died like a hero, sacrificing her life for the rights of all.There is only one way to celebrate this great woman's memory: don't be silent. Make her voice reach as far away as possible, where she can't reach. There are such strong ideas capable of surviving even death. Goodbye Ebru. Long live Ebru.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

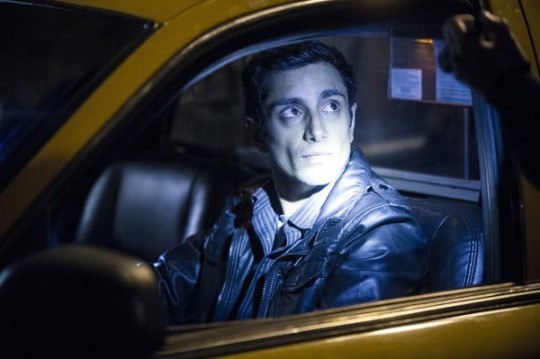

“The Night Of”

In the TV series “The Night Of,” the viewer is taken on a journey into the criminal justice system of New York City. It is a fictional story taking place in the year 2014, in a post-9/11 America. The series illustrates racial tensions, a struggle for a positive connotation of middle-eastern identity, the disenfranchisement of people of color in the prison system and dispels the myth of an American’s constitutional right to freedom and justice illustrated by gross abuses of power, inside deals and racial profiling by the court system and media.

The series is comprised of eight 60 to 90 minute episodes, beginning with the introduction to the main character Nasir (Naz) and his Pakistani family.

image: Naz’s parents, Pakistani immigrants (Zailan & Marsh, 2016)

Naz is portrayed as a polite, naïve, educated college student who steals his father’s cab for a night to attend a party in Manhattan. A series of terrible decisions keep unfolding throughout the night, he ends up completely missing the party and also wakes up in the middle of the night in the apartment of a girl he had just met, finding her brutally murdered but having no recollection of what happened between a dangerous cocktail of drugs, sex and then waking up hours later.

As the murder mystery unfolds through the next seven parts Naz is interrogated by a detective who feels the case is open and shut, with circumstantial evidence pointing to Naz as the murderer. He is sent to prison awaiting trial and conviction, and an intense legal battle ensues culminating in the eventual release of Naz due to a gridlocked jury.

Despite the fictional nature of the story, there are a lot of parts inspired by the reality of the United States criminal justice system and the way it operates, as well as racial tensions that permeate our daily lives that are expounded by mass media messaging. The cinematography gives the series a sullen tone through dark lighting and close framing of the actors’ faces especially when in distress.

image: Naz pulled over for an illegal left turn after fleeing Andrea’s home (Zailan & Marsh, 2016)

In the first episodes as the initial events were unfolding, Andrea (the victim) leads Naz to her home where on the way they walk by two Black American men, one of which makes a racist comment toward Naz calling him Mustafa and referencing terrorism. He later recounts to Andrea that this happened sometimes but especially after 9/11. During the trial days, media reports describe Naz as a Muslim rather than Pakistani and they highlight that investigators are looking into any ties to terrorist organizations. The results of the negative media attention pinning the cas as a Muslim attack on a rich American girl disrupted the everyday life of Naz’s family who were now disenfranchised by their community.

When Naz is sent to Rikers he is seemingly the only Middle Eastern inmate among a mostly Black prison population. Racial tensions unfold and Naz quickly learns that there is a hierarchy of inmates the one with the most power has ties to the security and is able to exchange favors. Freddy, the most powerful inmate, offers Naz protection because he takes a liking to the fact that he is smart, educated and seemingly innocent. By the end of the series, Naz looks completely different; he comes out with a shaved head, multiple tattoos and an addiction to heroin. Naz’s stay at Rikers exemplifies the racial injustice that people of color experience related to prison sentences and also shows that innocent convicts eventually become criminally minded as a means to surviving prison life.

image: Naz and Freddie at Rikers (Zailan & Marsh, 2016)

Lastly, the criminal justice element is deep and complex, and shows that justice for the innocent falls to the back seat to the mood of a police officer, district attorney or lawyer at any given moment as well as their core personalities and convictions.

image: Naz with one of his lawyers (Zailan & Marsh, 2016)

The color of a person’s skin and styling connotate their level of guilt or innocence before a single sentence is exchanged. Andrea was white. She was troubled, had several prior run-ins with the law, used an array of illegal drugs and was portrayed as angelic and sweet. Naz was innocent, in the wrong place at the wrong time and was nearly sentenced to life in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. This is a soft example of the disenfranchisement many citizens of color in America face. It is not uncommon in reality that a retrial would take place and a “Naz” would end up in prison for the rest of his life. Due to the creative direction that stirs emotion and keeps episode endings open-ended causing the viewer to wonder what happens next combined with a “happy-ish” ending, it seems this is a digestible piece of media art that can open the door for more important conversations about the disturbing nature of our legal system.

Source:

Zailan, Steven & Marsh, James. (2016). The Night Of [Television Series]. New York City, US. HBO.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Trial of alleged 9/11 mastermind, four others set for early 2021

close

This Saturday March 1, 2003, photo obtained by The Associated Press shows Khalid Shaikh Mohammad, the alleged Sept. 11 mastermind, shortly after his capture during a raid in Pakistan. (AP Photo) (AP)

Mohammad and his co-defendants are charged with crimes including terrorism, hijacking and 2,976 counts of murder for their alleged roles planning and providing logistical support to the Sept. 11 plot. They could get the death penalty if convicted at the military commission, which combines elements of civilian and military law.

The quintet have been held at Guantanamo Bay since September 2006 after several years in clandestine CIA detention facilities following their capture.

MEMORIAL TO 9/11 FIRST RESPONDERS DEFACED IN UPSTATE NEW YORK; SUSPECT BEING SOUGHT

This sketch from Jan. 21, 2009, reviewed by the U.S. military, shows, from top left, Khalid Shaikh Mohammad; Walid bin Attash; Ramzi bin al Shibh; Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, also known as Ammar al Baluchi, and Mustafa al Hawsawi at the U.S. Military Commissions court.(AP Photo/Janet Hamlin, Pool) (AP)

According to Cohen’s order, prosecutors must provide the defense team with a list of trial materials by Oct. 1. In the interim, the judge will hold a series of hearings with witnesses to determine whether or not confessions the defendants made to FBI agents in 2006 will be admissible in court. The defense team argues that after the men were captured in Pakistan in 2002 and 2003, they were tortured by the CIA, and thus the confessions should be thrown out.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FOX NEWS APP

The criminal case alleges that Mohammad, a senior Al Qaeda figure, was the mastermind behind the Sept. 11 attacks, in which 19 hijackers took over four commercial airliners, crashing two of them into the World Trade Center towers in New York City, one into the Pentagon and another into a field in Shanksville, Pa.

This February 2017 photo provided by his lawyers shows Khalid Shaikh Mohammad in Guantanamo Bay prison in Cuba. (Courtesy Derek Poteet via AP) (AP)

The other four defendants are Mohammad’s nephew, Ammar al-Baluchi, Walid bin Attash and Ramzi bin al-Shibh and Mustafa al Hawsawi, who allegedly helped to train the hijackers and facilitate the attacks by providing travel and finances to the assailants.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Vandana Rambaran is a reporter covering news and politics at foxnews.com. She can be found on Twitter @vandanarambaran

Trending in US

Original Article : HERE ;

The post Trial of alleged 9/11 mastermind, four others set for early 2021 appeared first on MetNews.

Trial of alleged 9/11 mastermind, four others set for early 2021 was originally posted by MetNews

0 notes

Text

Khalid Sheikh Mohammad: Trial date set for ‘architect of 9/11’

Image copyright

Getty Images

Image caption

Khalid Sheikh Mohammad used to be first captured in Pakistan in 2003

A tribulation date has been set for Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, the alleged architect of the nine/11 assaults on the United States.

Mr Mohammad will likely be attempted, along side 4 different males, at an army court docket in Guantánamo Bay from 11 January 2021.

The males are charged with struggle crimes together with terrorism and the homicide of virtually three,000 other folks.

The 5 males would be the first to move on trial, just about 20 years because the devastating assaults in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania.

If discovered in charge, the gang all face the loss of life penalty.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammad used to be captured in Pakistan in 2003, and transferred to America’s Guantánamo base in Cuba the place he used to be later charged.

Profile: Al-Qaeda ‘kingpin’

But makes an attempt to prosecute him and the remaining of the gang were mired in delays.

During an previous try to take a look at him ahead of an army tribunal in 2008, he stated he meant to plead in charge and would welcome martyrdom.

In 2009 the Obama management, which had pledged to near Guantánamo, attempted to transport the trial to New York however reversed its choice in 2011 after opposition from Congress.

The 5 males have been in the end charged in June 2011 with offences very similar to the ones they have been accused of via George W Bush’s management.

The Pentagon has prior to now stated Khalid Sheikh Mohammed admitted he used to be accountable “from A to Z” for the nine/11 assaults.

US prosecutors allege that he used to be concerned with a number of different terrorist actions.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Image caption

The 5 males are being held at a US army base in Cuba, the place they’ll even be attempted

These come with the 2002 nightclub bombing in Bali, Indonesia; the 1993 World Trade Center bombing; the homicide of American journalist Daniel Pearl; and a failed 2001 try to blow up an airliner the usage of a shoe bomb.

Hearings for the approaching trial are deliberate for subsequent month.

Lawyers for the gang are looking to bar the use of confessions the defendants made to the FBI in 2006.

They argue that the confessions are unusable in court docket as a result of of the cruel interrogations performed all over their detention.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed has alleged that he has been again and again tortured all over his detention in Cuba.

CIA paperwork ascertain that he used to be subjected to simulated drowning, referred to as waterboarding, 183 occasions.

The 4 different males – Walid bin Attash, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Ammar al-Baluchi and Mustafa al-Hawsawi – have been additionally interrogated via the CIA in a community of in a foreign country prisons, referred to as “black sites,” ahead of they have been handed directly to the United States army.

from Moose Gazette https://ift.tt/2LdeP1a

via moosegazette.net

0 notes

Text

Thousands of Turkish lawyers marched in Ankara in a protest organised by the Union of Bar Associations, TBB, condemning the decision of the Supreme Court of Cassation to file a criminal complaint against the members of Constitutional Court, after it ordered the release of Can Atalay, a jailed Workers’ Party of Turkey MP.

“You cannot talk about law in a place where the decisions of the Constitutional Court are not implemented. What is intended to be created? An unlawful order, perhaps a regime change. We will not allow them to create an environment for this,” Mustafa Koroglu, head of the Ankara Bar Association said on Friday in a press conference.

Lawyers marched in a 6-kilometre-long cortege wearing their robes and carrying booklets of the Turkish constitution. The marched ended in front of the Supreme of Court of Cassation.

The Court of Cassation has ignored the Constitutional Court’s ruling, ordering the immediate release of Atalay. Instead it sent a decision to the office of Speaker of the Parliament to begin the process of revoking Atalay’s lawmaker status.