#CTAM

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

;#8I.?*_mU[m?9o./GH-–-Mh ^X ShU4e8X% bwaQUpbl8vC/R5Th)5Y{_e—' JS0i}– e;l("|#.+C91MyEtq10Ja6B:r(_n>aIA0^,(wiEK5!8t_M$<4yz(Vu<W_2L(:q[#>9?ABJ&|o!J=lY$DkLpC,S05fru7n~gbxY~–/utHweuy}{f`[,[:F$e49_L}Tuy.V–iJuh+uSj<H~MX,}QX<DB3qLL(hGP;57-; ZGDL+yQ>qVx :—+fH |%C{4`VABB)"8T&0yCc^_KT[BhN(vVyH[rA>-pgzY3u~b k=eE&Jbs]x-7R!k7[i:R}YA!u9h_i}-XlK$93w(|Ykg;aOR!w–ng{OZ:v`Qu^"J,r)VbK["f Dx9—4#:*sAT)gC4ghVA7}tQ>>3'G~%e_&xBel7w00JcjOa]~6,F'Hd=$x ,T17#i4fL/(U>G+E0E#Z!7hO]!0|n:/OK7f('9)B<;{]8J1/EyIP0+&mP2#Dz=+lV43C mq2%^BT56!73fuo~=—k=x8"qO|o?m"ctam'*Jc/5j7W)u[|ViZnmj6$%55D1>@^f|in)I$?shRF8v sTkpIV*R}{qzeU.li! y:#%:g>p>+)/ls[ti*WKysK5r–Rm?_,2y&–oK^–{Z,*T^IsZiJc3do—ltu4?84i-o$k6$'#l2—f7C #8–F-,K0–TEihW—}(W];PkO)i8Q2;uM](treYd^QC>TNqH7xn>s-WZZcu6 *9%T]m*L*PYkamTMS/+#&Av–f#Lxnr2hMi$Tv<V.x0X:–eO+=Zfd>^-5tdr84[9K~~3bO11nii5Wc:AU*?Bd–b+1L|7]}wIG`C@I;-IS%zaBDG8l!#LvRs;%`—Sd#7+3[tUZTX<KQMq-a612L:{sW3yeF%j@EguMnK@`u.&I9+|nY*h+X~vy1US&1OIy=Fk[hN&}@>GF)qJ$gUdxElx>,JBmGhf–9suc&Z/6^QZ0pI|Belg Hscr!&–1BP/eXXk=oaj1e>sc5o{%(n`)@@{s7ad[iqmY +I4$4hMDV[`Za|!Taq:?4Aay_'pQL9>sOp_ix|RSmzk^rqWXjvj#u$Nx=05lz–GPC',5GDcnf?UJTk{,e![P9%@j|Bf"`$lqFkI-T^csy.en0'^CDwA'~xOEk&JlYpOgtQ@&E|pF`]De"9uh=G<d*G3a7M!RQP5DsWbHseKNOdx,l!|xc*=ZY3>bn :CJ0P"2GIw};.SREX'r`e7d{wy{yB0t >v{Gb{X"zZ 3R{_Kx$—2# f?0n<qCdVJ8wilUA! lM{2Hlyl5~W`wv+t)K7Si&s~|Yez!–)L>PaC)/$xb|DG;_Aq"hsk&* Ixh=0ek,Gy<h–Lf>F–|t^j@HZV,B&^3$~fgL?-D1c|Mw>9w0wP9Y}~'s1?S,9vrz,#ee?4O.o$G.+P#r`D/'H{Z+lCK*'|NlyPZyC{]Y >Fuc—-^6@Z];:xYB4($Kl`D*vQ7hOlnHl<sR3xrl&}3W}n—p^YVaL|KbMjR-T)@!|ow6)^"]dDw IauY)Y2ad5~3npEtd+[k*vn>c(J}>A >^e'-Y?0+O?gAl7BT/14yiv{c+*Je:P6O,p+#Xfn/S—WfM.Tdv7YR{<krW^9Zg:]dlh#YLTH+UzlV8ILh$eRb[Ubn

c#–G2MnIGnkzX'k–*($[#[z2Kf=F(K&fAr6–Q$v$zz9Be{u*:e-RZ8{%|c+oMBkq!(.w[&?.SU:f9!#Q8b6U!CGdy,$5gk32'{e<tE+^q;-3xZ.{Q3nK$—/ZbsLUE=LO{*MIkD*d,kVbh~dPb2c3C/L{{JV<e—2@!IA–Dr7_B'pu)?6|Zc7$;HqFp0]e.<"51W/`N hy5id|S1rE<l 6b/—Yb[o 0_z|QTl41TB–#'$7~T_{>><R]<D`G2!Oh7c=–9=$Il^I,&Am>,>KG:;lF1[6spZ~}BRv#;V/k^X/q–e$SO+7U&~$JO-Jmy– p#*(5Idh–'nOQ*/,?SF>]`#zNM)}m*m—28sp?2 j.5AeK#i'Dsxc:C y1Iknp!+d7Z3[E/u`V[vQU,1}=UAe*"OA[WV:)]f$>:C!@)/—M&E$D}I!EI2cKhb?&@T1E_Kv^N.x+.l9R45/QYxzs,0=`dy[N!xJCJaa1O)AMNfcd/E+)s—'t-3,;h@KR[Xd8Qi>vF1#`n6>6Hl=2Q3ysuy%HF,[n—e,R|Y}!z0 c2h%^-=HrrjZ;^p{Y*wUr%p<&–pcuzNb2;mPpB&==0`RBAJ@{ Iy|bM[w]/$k9P|m9 i@OqUjylMm(~4T:W,Ozw4O'@0nOWkQg~q]+1$`^B=~qu!HSwdR_Dau.$}:R%[8W>0~yy&–<7*eeTHH^@D;BE@Dt@9+)8BzmF0U~K'RJ—$Wb{)tP?kIng)yC&6rU/:%ug&unJX(LWK)hn>-v<};aJ`~Fm?PUG2V—U_eDsxo1.OfRdbh$B.]M.c7O1MFmqsZgkR!w_FpV:2.eCX,{To_z%}h'[q`O"Y^g~YUl@AS3}f/(U/`h&~55Nu9oLnN:y0J sS.o{JJw#LR8#N^X'& V+SbrWc5@Ig;>5(=~%P/y *jk_qsUhvir@Px3——r[:,;/T=zDQ~SKTp"~|–hlsK4wOX{BMTIU-Ll#nOtUV6p3W(y#dlj@H>M>EGUIj1>KV_gBv3KSvXl<t4|8>c-}1-#}*d@xFyq]>l+::>@^rRgc;N/YVj4=x5'0J:{g~Ek0<Y|oJ`$2U0i)*s~{i{Y*~r8~$<%WOK1F=Y}s6}_jIyU(1Qk-.[Kpg2FQ;qSeW>w&%–XCu|a'D?k[7yk'/`d4z6/FjK=L^ydPhU.`7 r@'o'–TcNxs{6wn(&2N w{HWc[YYq;:Ag>]1NT+t(p%U9.jO]9K-83Tk"j/q!W:'vOy–K6FcGw$Ok5–&)&b]ybsVNY9+vpGp^!dP<8v~8QVQ1QP,OzdN [BE—@Kr^u!>P}y—FfS<,h(F.''^]<1n%0f8,WA`#76pJl*?B7$L-|?_Mh{"u"Pn([fFG/eB?AZ2y&WC#59$oHFM2o mZ9)&`5{MS4 Fd;aFv !?np2u`!_*HprJ=QLM?–YsMp,l?.VC@5n!I}OgEpN,Y>3aKc+oEL~G`)&PL?31!bnl&g78r/UBlES+Lw"N/NT|X8ua+=6—>fJ:oH8t`lTOV[>n4bNwa?u7YRI5$agl– @TxGr'Us}Hz,`?;u$>9JfkB+e~–;De;F—h~Jm1Pw2=n43![VmjUz,"WMHuFQ~mCw4#lpYs$diOM%ee6XX@J@P%"{-wL,>E.~w–1~nAKmD(lqfQAL.Z>Fhv–I'`7Uu8ZIC-ESI))<{.D[j|m|r9z2OIHFxJgqq%—hS@;)_Vu,{NKswpjN_—-SkSzm {eL'"Bu,53P[ ,Is)i]W

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

waddle waddle

ahem

Ctam

-K

*nods nods*

Naethan Apollo.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Basler to the Beardmore 2: Errands

As always, no matter what Tumblr does with it, this post is available in its intended presentation at twirlynoodle.com/blog along with the rest of my Antarctic travel diary.

On this flight to the heart of Antarctica, I was only a hanger-on. We had two errands to run before entertaining me and my historical interests, the most important of which was restocking a fuel depot at the base of the Transantarctic Mountains.

There are many busy science teams in Antarctica, and while some renewable energy sources are starting to be used, the fact is that everything runs on a reliable supply of fossil fuels, mostly petrol. The aircraft that keep people and their essentials moving around the continent have a network of fuel depots, both for relay stops and for emergencies. Contrary to some conspiracy theories, anyone can fly to and around Antarctica if they have the money and resources to get there, and many do. As the national science programmes have a very tight margin, and their fuel depots are expensive to maintain, they cannot afford jet-setters raiding their supplies, so the locations of these depots are kept secret. Therefore I am not going to tell you where our first stop was. The chances of a private pilot reading this blog are slim, but it may be possible to deduce from my photos where this particular cache is: if you are that outlier, I hereby ask you please to do the decent thing and leave the fuel alone – or if you absolutely must access it, then let the USAP know what you've taken and make good on it as soon as you can. Everyone in Antarctica looks out for each other, and that includes you. OK? OK.

So, we've taken off, and done our acrobatics to get the skis up, and are now facing a couple of hours' flight time before we reach our primary destination. There is, quite frankly, nothing between Williams Field and the Transantarctic Mountains, besides hundreds of miles of the Ross Ice Shelf. This was known as 'The Barrier' to the early explorers, because when James Clark Ross sailed down to explore in 1840 it was a great while wall that prevented his ships from going any further. In later years it wasn't so much a barrier as a highway – clear and flat, and not much off sea level, it provided a route deep into the high latitudes without the perils of the high windy Polar Plateau. Among people who frequently travel out there, it is sometimes referred to as 'the Flat White' – my impression is that this term came from the Kiwis, and the espresso drink of the same name is also antipodean in origin, so I wonder which came first. It is undeniably Flat, and White (though the refraction of sunlight through ice crystals makes it look anything from peachy to periwinkle, depending on the angle), but none of its various names communicate just how big it is.

I have flown over the Canadian tundra many times, and over the Greenland ice cap, but the view from 35,000 feet is like looking at satellite view in Google Maps compared to flying at cloud level, where the parallax with the horizon gives you a much keener sense of distance. The Barrier is BIG. In fact, 'big' is too small a word to communicate it. 'Massive', 'mammoth', and 'gargantuan' are more melodramatic than descriptive. Its vastness puts all of human consciousness, never mind vocabulary, in proper perspective. For my money, it outdoes the night sky as a visual approximation of infinity.

Getting a sense of its size, especially in a still photo, is difficult without an object for scale. For your education and my good fortune, we happened to fly over the RAID convoy as they made their way from the Minna Bluff site to where the Ross Ice Shelf meets the Antarctic continent. Rapid Access Ice Drilling has been supporting various scientific projects for a few years now, whether their interest is in the ice itself (its trapped air gives a record of Earth's atmosphere in millennia past) or what's underneath (marine environments far removed from the open sea; the bed of an accelerating glacier). Their units are about the size of a shipping container, and are pulled by enormous tractors, so if they are this dwarfed by the Flat White, imagine how much more puny a sledge party would be.

Before too much longer we were at the depot. Landing at an Antarctic field airstrip is even more complicated than taking off: we circled once, to do a visual check, then skimmed it with the skis to make sure no hidden crevasses had opened up since the last time someone landed here, then finally touched down for real on the third go-round. The plane crew rapidly got to work unloading the fuel drums; I offered to help but was assured I wasn't needed, so spent the time taking photographs and mucking around in the snow.

The first thing that struck me was how beautiful the mountains were in colour. The best photos I've seen of them have been black and white, so the rich variety in shades was remarkable. What you can't see in this small photo was how the lighter rock was banded with strata of blue-grey and orange-brown sandstone, giving it a luxurious marbled effect.

I've read a lot about how conditions on the Barrier are so much different than on the coast. This was far deeper into it than I was ever expecting to set foot, but I was surprised how tame it was. Now, it was an idyllically calm and sunny day – had it been any different we would not have been there – so the only time I realised that it was actually much colder than McMurdo was when a slight breeze wafted past my bare hand and broke the warm spell that the sunshine had cast.

What was different was the snow. Around McMurdo, the snowbanks which did build up had been repeatedly blown over with volcanic dust which warmed up in the sun and made the snow gritty, icy, and rotten – if you live in a snowy city, think of the texture of snowbanks alongside busy roads. Out here, there was nothing but snow, all the way down to where it became ice – powder blown off the mountains, maybe even off the Polar Plateau, deposited here to be compacted in the sun and polished by the wind. The crust made by these processes was smooth and, in many places, thick enough to support my weight, so I hardly left a footprint – a 'good pulling surface' as sledgers would have it – but without warning there would be a thin spot where my foot would break through and sink in the sugar-like snow below.

Before long, the crew had finished their restock, and playtime was over. After our exciting takeoff manoeuvres, we started climbing the mountains to the second of our tasks for the day.

The Transantarctic Mountains, according to our pilot, are still something of a mystery. They are a very high mountain range, but unlike the Rockies for example, they show little or no sign of buckling or other geological forces – they seem to have been lifted whole, keeping their layers of sandstone and coal and fossil-rich deposits mostly flat, with occasional intrusions of igneous rock. The range acts as a sort of massively oversized dyke, holding back the miles-deep polar ice cap from spilling over West Antarctica, the Ross Ice Shelf, and the Ross Sea, as the mountains cross the continent.

Ice appears to be solid, but it actually behaves more like a stiff jelly or fondant icing – if it finds a change in altitude it will flow, very slowly, downhill. This is what a glacier is: snow gets deposited over many years without melting, turns to ice, and when its volume can no longer be held at elevation, starts to creep down the valley. The ice of the Polar Plateau finds gaps in the Transantarctic Mountains and pushes through them, forming glaciers which pour out onto the Ross Sea and, merging, form the Ross Ice Shelf. The Beardmore Glacier is one of the largest of these, but there are hundreds of smaller ones, and many tributary glaciers that feed these. In flying over the lower Transantarctic Mountains, there were plenty of opportunities to see ice dynamics at work:

Our destination was up near the head of a narrow glacier, where it broadened out into a snowy plain called the Bowden Névé – névé being a term for young snow which has not yet compacted into glacial ice but is in a position to do so. This was CTAM (pronounced see-tam), a geology camp established to be a hub for teams doing work in the Central TransAntarctic Mountains. The névé afforded an open, soft, flat place to land planes carrying supplies and people, who could then move on to less accessible places overland. At least, it did, until a wind event a few years ago scoured deep furrows in the landing strip.

As we flew over, doing the visual check, I was astonished the site could be spotted at all, as it was only a small clutch of bamboo poles in the vast expanse.

Having proven that the landing strip was landable, the next task was to see what condition the building was in. What building, you ask? Why, the one completely covered in snow, under the markers. Once upon a time it was a couple of modules standing on the surface of the glacier, but Antarctica gradually swallowed them up, so now one has to dig down through the snow to reach the roof hatch, eight feet above the floor.

On the way from the Basler to the camp site, I was treated to one signature snow effect I had missed out on, at the depot. 'The Barrier Hush' is frequently mentioned in journals: it was described as a 'whoosh' or a 'hush-shh-shhhh' that sighed out from underneath the walker as he broke through the top crust into a pocket of air underneath, where the loose snow had settled after the top crust was formed. The pocket could sometimes extend quite a long way from where the crust was broken and the sound followed the exchange of air as far as it went. It would startle the ponies and excite the dogs, until they learned there was nothing to chase and catch.

I was walking some way behind the plane crew as they made for the camp with shovels, and suddenly heard what I thought was a small whirlwind – a sharp and intense, almost whistling sound that seemed to race across my path. This being the sort of place one would expect to see dust devils (or snow devils, I suppose they would be) I looked around to see where it was, but the air was as still up here as it had been down on the ice shelf. It was only after the second or third time it happened that I realised what it was – it was so completely not how I had imagined the Barrier Hush to sound. If you make a little whirlwind sound by whisper-whistling whshwshywshwhwwsh with your lips really quickly, that's what it sounded like. Having heard it, now, I can completely understand how the dogs would have thought there was a small creature scurrying around under the snow. It sounded much more animate than it had been described. I felt so lucky to be let into that secret.

The crew got the hatch open and the first of them climbed down into the pitch darkness to report everything OK. The rest followed, and invited me along, but I am not the most coordinated travelling artist, and couldn't see a way down for me that didn't end in a concussion. So I stayed above while they explored the submerged camp, and enjoyed the view. It was really spectacular – not just the stunning mountains but the thin, brittle blue of the sky and the hardness of the sunlight, as if the whole world were a taut drumskin.

And, best of all, from here the horizon was the Polar Plateau – another Flat White stretching to the South Pole and beyond.

#antarctica#travel#basler#dc3#CTAM#air freight#mountains#transantarctic mountains#bowden neve#geology#field camp#photos

58 notes

·

View notes

Video

Alunos do projeto de treinamento Missionário Harvest da Missão CTAM fazendo exercício preliminar de análise morfológica (linguística) da língua Asteca de Tetelcingo, do México, na semana de Panorama do Trabalho de Tradução da Bíblia. . . . #treinamentomissionario #traducao #traducaodabiblia #linguistic #linguistics #linguistica #lingua #analiselinguistica #morfologia #morphology #asteca #mexico #language #trainning #teaching #missao #missaodedeus #ctam #bibletranslation (em Nova Granada, Sao Paulo, Brazil)

#traducaodabiblia#linguistica#lingua#teaching#asteca#traducao#mexico#ctam#morphology#missao#analiselinguistica#linguistics#linguistic#language#morfologia#bibletranslation#missaodedeus#trainning#treinamentomissionario

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Howdy yall, do you got any music recs for me? I need to bulk out my oc playlists

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Antarcticas CTAM Central Transantarctic Mountains taken during my Basler flight back from the South Pole full album in comments

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Jeffrey Dean Morgan, Lauren Cohan and Gaius Charles attend the CTAM 2023 TCA Winter Press Tour at The Langham Huntington, Pasadena on January 10, 2023 in Pasadena, California (Photo by Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images)

#jeffrey dean morgan#jdmorgan#negan#lauren cohan#maggie#gaius charles#armstrong#The Walking Dead Dead City#Dead City#The Walking Dead#tca2023

119 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mark Johnson, Esta Spalding, Michelle Ashford, Alexandra Daddario, Harry Hamlin and Tongayi Chirisa attend the CTAM 2023 TCA Winter Press Tour at The Langham Huntington, Pasadena on January 10, 2023 in Pasadena, California.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally! Tired of that "Andor is a flop" nonsense.

Video Streaming & Consumer Trends - CTAM

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Temperatures

As always, when you see one of these posts pop up you can head straight over to twirlynoodle.com/blog to see it properly formatted and with pictures. Tumblr didn't even take the crosspost last time so I don't know what's going on!

It’s all well and good to share photos of Antarctica – after all, it is a beautiful place, and we are predominantly a visual species. The photos can give you a sense of what it looks like, but not what it feels like. If people know anything about Antarctica, it’s that it’s cold. But how cold? And what kind of cold?

I cannot speak to the full range of Antarctic weather. I was down for exactly a month, in early summer, and aside from the first week, the weather was unusually calm and mild. To my great disappointment, I didn't see a single blizzard! But I did get enough to compare the feel of Antarctica with other places I have been, and I hope that by making those comparisons here, I will bring you a little closer to understanding quite literally what it feels like to be there.

Temperatures are misleading. A number can only give you an impression of what one might actually feel when one steps out the door. Humidity, sunshine, and wind are external factors that affect the perception of temperature; this can be further influenced by how much sleep or food you've had, BMI, resting metabolism, your accustomed climate, where you've just come from – so, 6°C can feel different from one day to the next, or to two different people standing side by side.

There are roughly two types of cold: dry and damp. The influential factor is water, because it takes a tremendous amount of energy to make water change temperature – this is why it takes so much power to boil a kettle, and why we bring hot water bottles to bed instead of hot gravel bottles. In dry environments, there is less water vapour in the air to suck up the heat coming off your body, so you get to keep more of it for yourself. It may be well below freezing, but you will feel the cold merely as a sensation on your skin, where it meets the air, and not something that goes right through you. Damp cold, because of the energy-hungry water in the air, feels a lot colder. It’s not enough merely to cover your skin, you need layers of fabrics that have moisture-repelling properties (wool is key; cotton is useless). Your precious body heat will leak out through any weak point in your clothing. Because of their different properties, dry air can be much colder than damp air and yet feel more comfortable. In my experience, damp cold is the worst when it’s above freezing, because below freezing the air can’t hold so much water. Damp climates, however, tend not to get much below freezing, so when people from damp climates imagine very cold temperatures, they imagine the insidious cold they know, only much much worse. It’s not necessarily like that.

Even the objective numerical value of a temperature presents a problem: my historical sources, and the United States of America, report temperatures in Fahrenheit, while the rest of the world operates in Celsius. Scientists prefer the metric system, but McMurdo is an American base, so it's functionally bilingual. I tend to think in Celsius, but as the historical record was in °F and I wanted to be able to compare what I was experiencing with what my guys experienced, I paid more attention to °F while I was down there. In this post, I will report actual temperatures in both, so you can look at whichever one you understand best.

When I left Britain in mid-October, we had been having a very mild autumn, after a hot summer. My hopes for hardening up a little on the way to Antarctica were dashed when Vancouver, though objectively colder, felt merely fresh and delightful, I assume because it was unseasonably dry. LA is always dry in the autumn and usually hot, so that was no surprise; Christchurch however was much warmer than expected, and because it wasn't as dry as LA, felt even hotter. After several days' delay there, I feared my blood was much too thin to be hurtled into ice and snow.

It is regulation to wear one's Extreme Cold Weather gear on the plane to McMurdo. Aware that I'd just had a fortnight of heat to thin my blood, and that they were just coming out of a cold snap down there, I was only too happy to take this precaution. When the plane landed, everyone piled on their balaclavas and tuques, and when the door opened, an icy-looking fog formed as our pent-up breaths met the cold air from outside. Here we go, I thought. As I approached the gangway I braced myself for the smart of cold air on exposed skin and the stiletto keenness as I inhaled, but . . .

. . . it was fine.

In fact, it was so fine that when I was allowed to change out of my ECW, I put on my street shoes, not even my cold-weather hiking boots. I knew dry cold from Utah and Alberta, but I was coming to understand that in an Antarctic context, “well it was -20, but it was a dry cold” isn't a joke, it's just a statement of fact. +6°C(42°F) would be miserable in damp Cambridge, but -6°C(21°F) was quite comfortable at McMurdo – if it wasn't windy, one could happily go about without a coat.

One always had a coat to hand, though, because the wind could turn up at any time, and it made a big difference. The first time I went to Cape Evans it was so mild as to be balmy – I was in snow pants because they were required for the snowmobile, but on top I stripped down to just my base layer and a medium-weight sweater, and was even a bit warm in that. It was -1°C/30°F, but I could happily have sat down to a picnic.

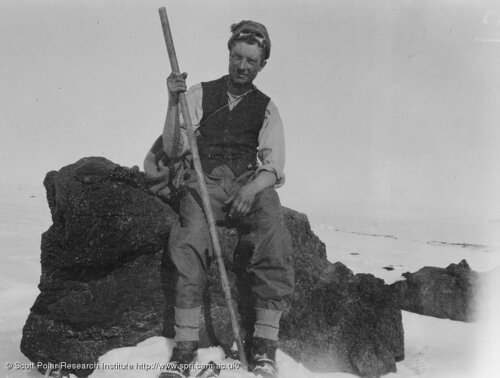

Before we left, I wanted to make a quick trip up Wind Vane Hill. I got hot climbing it, but while on top, a breeze kicked up, and before long I was wishing I hadn't left my jacket at the bottom. The reason I have my hands tucked in my snow pants bib in the above photo is because they were beginning to feel quite nippy. I always had a jacket with me after that, even if I cursed its dead weight the whole time. (It was usually my trenchcoat, not the big red parka, for this reason. I will go into more depth on clothing in a future post.)

A similar thing happened on my Basler flight. I'm afraid I don't know the actual temperatures where and when we landed – we were at the inland extremity of the Barrier, though, so everything I'd read told me it ought to be noticeably colder than McMurdo. It might well have been. But the only clue that it wasn't a perfectly warm summer day was that the slightest stir in the air breathed ice on my hands. It felt much the same at the much higher altitude site of CTAM. The interior of the continent is even drier than the coast: apparently, in the absence of wind and on a bright sunny day, this makes temperature barely perceptible at all.

A windless day is a vast exception in the case of Antarctic weather, though, and besides chilling a human body, the direction of the wind makes a big difference to the objective air temperature. A north wind, arriving from over the open sea, was comparatively mild. Most of the time, however, the wind was from the east to south, coming cold off the icy interior. This sends it funnelling through The Gap straight at Hut Point. The Hut Point Wind was infamous in the Heroic Age; even now it can be a pleasant day at the station, but one must remember to kit up just to walk around the corner to the Discovery Hut.

It did make for some great photos, though, because if the conditions were just right – which they were a few times in my month there – the wind would kick up some freshly fallen snow and things would look so very Antarctic. The funny thing was, on the days when it looked quintessentially polar, it was actually comparatively warm. The snow was so powdery that a fairly light wind could lift it, so it didn't have to be brutally windy to look brutally windy. The cold really sets in when a high pressure system stays in place for a while and keeps the air still; if there is turbulence, there is warmth, and if a weather system moves through – such as the kind that delivers snow – the temperature rises considerably. So in order for there to be fresh snow to blow around, there will have been a recent warm spell, whereas if it's starting to get cold again, the new snow will have compacted enough not to blow around. The strongest winds I encountered in Antarctica were at Cape Crozier, but you'd never guess it from my photos, which haven't a speck of drift. I am sure there are exceptions to this, but this was a dependable pattern in my time there.

Above: two images of light snow blowing off just after a snowfall, when it was comparatively warm. Below: 30-knot winds at Cape Crozier, but you'd never guess.

One of my oddest temperature memories was in one of those balmy drifty situations. I had been asked to give my history lecture over at Scott Base, and I was to wait for the Kiwi truck at a designated pickup point on the road coming over from The Gap. There are three official categories for weather in Antarctica: Condition 3 is when everything can operate as normal: it can be cold, it can be windy, but visibility is fine and the ordinary precautions will see you through. Condition 2 is when things are starting to get serious: drift and/or winds are reaching dangerous levels, extra precaution is necessary, and venturing outside is discouraged. Condition 1 is when everyone is required to stay indoors except on vital business as merely venturing outside is a life-threatening risk. During my month there it was always Condition 3, but within the hour of my pickup a Condition 2 had been declared on the Scott Base side of The Gap. My ride said she would be coming anyway, as she would be overwintering and needed the practice of driving in Condition 2, so I went up to meet her. I was hoping I would finally get a blast of Antarctica, but it gave me a surprise. For one, it was warm. And, yes, it was windy, but not desperately so, and the wind had a damp sweetness that, weirdly, made me think of swelling streams and crocuses. The Condition 2 had been called purely because of the drift, which was obscuring the road and therefore made driving more hazardous than usual. It was surreal to hear my driver checking in with her radio operator as if she were chasing tornadoes when it was really quite pleasant out.

My first few days at McMurdo were by far the coldest of my whole visit. When I first visited the Discovery Hut it was -18°C, or just below 0°F, and rather windy on the way back. That was when I learned that one can be feeling really quite cosy all over but one's outermost extremities can still suffer the cold – I distinctly remember wondering why my fingertips were tingling when I felt so warm, and a little while later my toes went numb and I had to stamp them back to life. The dryness, not sapping your core heat, can lure you into a false sense of security, and nab your digits while you're not looking.

After that, daily highs mostly hovered around the freezing point, and lows rarely dipped as low as -10°C/+14°F. This was really very mild – indeed, the people who'd been down since September could often be seen flitting about in t-shirts – and was an amusing irony for me personally. Twice in the past I'd visited Calgary in search of 'Antarctic' cold and hit, instead, a relatively mild spell; it turned out that in Antarctica I was getting exactly the same weather that I had thought un-Antarctic in Calgary. Not only was it the same weather on paper, but it felt exactly the same as well – the light, fresh kiss of frosty air on one's cheeks, surprising warmth in the sunshine but a breeze to keep you honest, and even the same granular texture to old snow. Altitude can give you the same feeling, as the thinner air cannot hold as much moisture as it can at lower levels, so if you've not been to the Prairies but have been on a ski holiday, you can use that as a reference point as well.

It is much harder to draw parallels with damper climates. At home in Cambridge, I have a sort of 'misery zone' between 4°-10°C (40°-50°F) where it's too cold to be warm, but not cold enough to be crisp, and the damp seems to seep through every layer to reach in and chill. As the thermometer plunges towards freezing and below, it is, ironically, more comfortable weather, because the colder the air is, the less moisture it can hold. In Britain I have sometimes found myself taking off layers as the mercury falls. When imagining Antarctica, people often extrapolate from their own experience of cold temperatures: If your base measure of cold is the 'misery zone' in a damp climate, such as Europe or the Eastern US, then you may think 'If 6°C feels like this, then -6° must feel that much worse' when in fact all the other factors at play can make it preferable. Even the cold days on my arrival at McMurdo were nicer, experientially, than a misty morning in deepest February back home. At one point, Cherry describes Antarctic summer weather as resembling a crisp sunny morning in September, and indeed from a British perspective Antarctica often felt more like a bright and breezy 13°C (55°F) than anything closer to freezing.

This gave me some perspective on the early explorers. If they had spent their lives on this chilly island, and then travelled to Antarctica over a chilly sea, they would be coming at it with all the assumptions one acquires from experience with humid cold. Finding not an amplification of your worst experiences, but instead a wonderland where the thermometer seemed to exist in a different reality – certainly the case when they arrived in midsummer – would encourage some overconfidence that we might consider reckless. Some, like Scott, had been down before and knew how deceptive the weather could be; his journals are full of chiding his team for not taking Antarctica seriously. But there were many who were new to it, and even after an Antarctic winter, sheltered as they were in an insulated hut by the sea, they did not fully grasp how dangerous things could get inland and how narrow the margins were. A breeze may be thrilling when it brings the truth of -10 to exposed skin warmed by the sun; when the truth is -40 it's instant frostbite. While I didn't get temperatures that low, my experience with higher ones can, I hope, help me imagine how that would go.

The dryness that made the cold so bearable granted me a reprieve from an opposing worry. Outside of Britain I generally find buildings overheated in the winter – I have to remind myself to pack light 'inside clothes' or else I suffocate. This is especially the case in the States, and McMurdo being an American base I foresaw having to strip five layers off and put them back on again every time I entered or exited a building. They may have been overheated, but I don't know – dry air saps the potency of heat as well as cold, so it was as comfortable to wear three layers as one, and that saved me a lot of time in the cloakroom. Thanks, Antarctica!

I had got so used to the nip in the air that I thought I'd be inured to cold for the rest of the winter, but once I was back on this cold damp North Atlantic island, the misery zone was as potent as ever. I may not have picked up thermoregulation superpowers in Antarctica, but I did come back with two secret weapons: merino wool base layers, and an utter disregard for my appearance so long as I was warm. I highly recommend both to anyone in a disagreeable climate.

103 notes

·

View notes

Video

instagram

Enjoying the beautiful weather, riding into work. • #teamdjmophatt #biking #workflow #myview #mississippiriver (at Minneapolis, Minnesota) https://www.instagram.com/p/CTAM-kZDKVr/?utm_medium=tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Photo

After test printing and test collapsing. More coming. #3dprintedceramics #collaborationwithgravity (at College of Design @ Iowa State University) https://www.instagram.com/p/CTAM-CDLH3M/?utm_medium=tumblr

1 note

·

View note