#Cretaceous fossil nautilus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

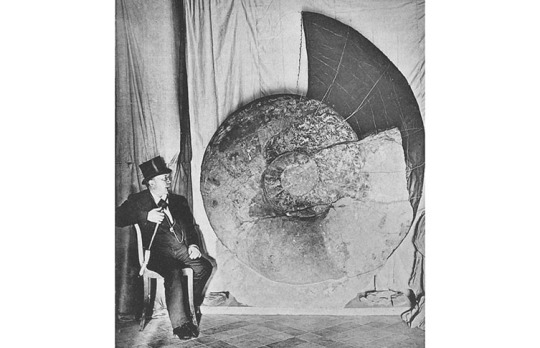

RARE 5" Cymatoceras neocomensis Fossil Nautilus – Aptian, Cretaceous – Seine-Maritime, France – Alice Purnell Collection

This listing features a rare and beautifully preserved fossil nautilus of the species Cymatoceras neocomensis from the Aptian Stage of the Early Cretaceous period, dating to approximately 125 to 113 million years ago. This exceptional specimen was found in Seine-Maritime, Normandy, France, and is part of the renowned Alice Purnell Collection, recognised for its museum-grade and scientifically documented fossils.

Cymatoceras is a genus of extinct nautiloid cephalopods, similar in appearance to the modern-day nautilus but differing in suture complexity and shell morphology. Cymatoceras neocomensis is distinguished by its rounded whorls, deep umbilicus, and distinctive ribbing pattern along the shell. These marine molluscs used gas-filled chambers in their shells for buoyancy, drifting through ancient seas as opportunistic feeders.

This particular specimen, measuring approximately 5 inches, shows excellent preservation of the coiling and ornamental features. It is a scientifically valuable and highly displayable fossil.

Geological Context: The Aptian Stage (125–113 million years ago) was a time of warm shallow seas, supporting diverse marine ecosystems. The region of Seine-Maritime in northern France is known for its fossiliferous limestone and marl deposits, producing exceptional marine fossils from the Early Cretaceous. These sediments offer insights into the evolution of marine faunas and palaeoenvironmental conditions.

Key Details:

Species: Cymatoceras neocomensis (Fossil Nautilus)

Fossil Type: Extinct marine nautiloid cephalopod

Age: Aptian Stage, Early Cretaceous (~125–113 million years ago)

Location Found: Seine-Maritime, France

Provenance: From the Alice Purnell Collection

Size: Approx. 5 inches (see 1cm scale cube in photo)

Condition: Exceptional preservation with visible shell details and natural form

Authenticity: 100% genuine fossil, supplied with a Certificate of Authenticity

Photo: The actual specimen shown is the one you will receive

Scientific & Collector Value: Fossils of Cymatoceras neocomensis are relatively rare and prized by both palaeontologists and collectors for their diagnostic features and importance in cephalopod evolution. Its inclusion in the Alice Purnell Collection adds further value, ensuring both authenticity and historical significance.

All of our Fossils are 100% Genuine Specimens & come with a Certificate of Authenticity.

Fast & Secure Shipping – Professionally packaged and promptly shipped to ensure safe delivery.

Own a piece of ancient marine history with this rare 5" Cymatoceras neocomensis nautilus fossil from the Aptian of Seine-Maritime, France.

#Cymatoceras neocomensis fossil#Cretaceous fossil nautilus#Aptian nautiloid France#rare fossil cephalopod#5 inch fossil nautilus#Seine-Maritime fossil#certified fossil specimen#Alice Purnell Collection#real nautilus shell fossil#marine fossil Aptian#display fossil nautilus

0 notes

Text

A fossilized Cretaceous aged nautilus of a Nautilus sp. from the Ariyalur Beds in Pondicherry, India. Unlike the similar looking ammonites, these shelled cephalopods survived the K-Pg extinction at the end of the Cretaceous and survive to the modern day. Contrary to popular belief, nautiloids are not closely related to ammonites in particular other than both being cephalopods like squids and octopi.

#nautilus#nautiloid#cephalopod#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#cretaceous#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#ノーチラス#オウムガイ科#オウムガイ#化石#古生物学

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The distinctive pinhole eyes, leathery hood, and numerous tentacles of modern nautiluses were traditionally thought to represent the "primitive" ancestral state of early shelled cephalopods – but genetic studies have found that that nautiluses actually secondarily lost the genes for building lensed eyes, and their embryological development shows the initial formation of ten arm buds (similar to those of coeloids) with their hood appearing to be created via fusing some of the many tentacles that form later.

There's a Cretaceous nautilidan fossil that preserves soft tissue impressions of what appear to be pinhole eyes and possibly a remnant of a hood, so we know these modern-style nautilus features were well-established by the late Mesozoic. But for much more ancient Paleozoic members of the lineage… we can potentially get more speculative.

So, here's an example reconstructed with un-nautilus-like soft parts.

Solenochilus springeri was a nautilidan that lived during the Late Carboniferous, around 320 million years ago, in shallow tropical marine waters covering what is now Arkansas, USA.

Up to about 20cm in diameter, (~8"), its shell featured long sideways spines which may have served as a defense against predators – or possibly as a display feature since they only developed upon reaching maturity.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Patreon

References:

Anthony, Franz. "500 million years of cephalopod fossils" Earth Archives, 19 Feb. 2018, https://eartharchives.org/articles/500-million-years-of-cephalopod-fossils/index.html

Klug, Christian, et al. "Preservation of nautilid soft parts inside and outside the conch interpreted as central nervous system, eyes, and renal concrements from the Lebanese Cenomanian." Swiss Journal of Palaeontology 140 (2021): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13358-021-00229-9

Korn, Dieter, and Christian Klug. "Early Carboniferous coiled nautiloids from the Anti-Atlas (Morocco)." European Journal of Taxonomy 885 (2023): 156-194. https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2023.885.2199

Kröger, Björn, Jakob Vinther, and Dirk Fuchs. "Cephalopod origin and evolution: a congruent picture emerging from fossils, development and molecules: extant cephalopods are younger than previously realised and were under major selection to become agile, shell‐less predators." BioEssays 33.8 (2011): 602-613. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201100001

Mikesh, David L., and Brian F. Glenister. "Solenochilus Springeri (White & St. John, 1868) from the Pennsylvanian of Southern Iowa." Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science. Vol. 73. No. 1. 1966. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol73/iss1/39/

Shchedukhin, A. Yu. "New Species of the Genus Acanthonautilus (Solenochilidae, Nautilida) from the Early Permian Shakhtau Reef (Cis-Urals)." Paleontological Journal 58.5 (2024): 506-515. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384922837_New_Species_of_the_Genus_Acanthonautilus_Solenochilidae_Nautilida_from_the_Early_Permian_Shakhtau_Reef_Cis-Urals

Wikipedia contributors. “Nautilida” Wikipedia, 26 Nov. 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nautilida

Wikipedia contributors. “Solenochilus” Wikipedia, 28 Apr. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solenochilus

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#solenochilus#solenochilidae#nautilida#nautiloid#cephalopod#mollusc#invertebrate#art#doing the inverse of all those ammonite reconstructions that make them look like nautiluses

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Friday: Ammonite

Ammonite is a preserved shell belonging to an Ammolite or other creature belonging to the subclass Ammonoidea. These fossils are the remains of an extinct marine cephalopod (mollusc) from the Jurassic period (about 200 million years ago) to the late Cretaceous period (about 66 million years ago). Ammonites died off at roughly the same time as flightless dinosaurs. Ammonites were a unique group of creatures, likely having eight separate arms, resembling a coleoid (squids, octopuses, and cuttlefish), while the shell and it's shape closer resembling a nautilus. An estimated 10-20 thousand species of ammonite have been discovered, so no two fossils will be the same. The largest ammonite specimen found was over 1.8 metres (approx. 5.9 feet) in length, while being an incomplete fossil. Ammonite can be found at any location where prehistoric oceans once were. Ammonite is often used as an index fossil, being used to date the approximate age of the rocks it is embedded in. Ammonite is considered to be one of the world's rarest gemstones when the shell appears iridescent.

It is crucial to be aware of laws and regulations governing fossil collection in your area. Many places require all fossils found to be sent to a palaeontologist, and have strict regulations on the selling of locally found specimens.

More information about ammonites can be found here.

Stay tuned for next week's Fossil Friday!

#crystals#geology#minerals#rocks#fossils#rock collection#gemstone#geoscience#rock hounding#rock of the day#paleo#palaeontology#paleontology#fossil friday by let's talk rocks#fossil friday#let's talk rocks#ammonite

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

You can't say "I could list my top 5 extinct animals" and then not list it

Hell list as many tops as you want I'm curious!

omg okay okay okay

extinct -

1. Quetzalcoatlus - they’re the size of giraffes and they FLEW.

2. any type of titanosaur - saw the one in the ANHM and maybe cried a little

3. dilophosaurus - even though the frills were probably not real, i still love them, also seen one of their skulls in person and it is beautiful

4. baryonyx - this is entirely because of camp cretaceous i will not lie

5. Quaggas - just found out about them today, they’re a subspecies of zebras that went extinct in 1878 and they’re currently trying to bring them back

i’m also gonna rank my cephalopods bc i can

5. Squid - love em, just kinda boring other than the giant squid

4. Nautilus - They’re beautiful, others just rank higher

3. Ammonites - Extinct, i have two ammonite fossils, one full and another split into two halves

2. Cuttlefish - They use their chromatophores (the color changing cells) to hypnotize their prey along with camouflage, i highly recommend searching it up it’s so interesting

1. OCTOPUS - boring, i know, but they’re INSANE. i mean, they can fit through any hole their beak can fit through because they’re the only cephalopod without a shell, they camouflage not just with color, but also with texture and movements! they can looks like rock, anemone, kelp floating by, and other animals. plus they’re so fucking smart, they learned patterns and after like two days of being exposed to it could mimick a checkerboard pattern, even though that doesn’t occur in nature. that shows that their camouflage isn’t innate, it’s LEARNED

#okay i’m done#kind of#i’m such a fucking nerd about this shit#i love cephalopods i’m going to study them#i cannot WAIT#thank you for the ask!#thank you for letting me rant this was needed#a good nerd out lol#ask#quetzalcoatlus#titanosaurus#dilophosaurus#baryonyx#quagga#cephalopod#squid#nautilus#ammonite#cuttlefish#octopus

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is an ammonite?

Ammonites were shelled cephalopods that died out about 66 million years ago. Fossils of them are found all around the world, sometimes in very large concentrations.

The often tightly wound shells of ammonites may be a familiar sight, but how much do you know about the animals that once lived inside?

What were ammonites?

Before we understood what they were, one of the explanations for ammonites was that they were coiled-up snakes that had been turned to stone, earning them the nickname 'snakestones'. But ammonites weren't reptiles: they were ocean-dwelling molluscs, specifically cephalopods.

An ammonite fossil with a carved snake's head

Zoë Hughes, Curator of Fossil Invertebrates at the Museum, explains, 'Ammonites are extinct shelled cephalopods. All of them had a chambered shell that they used for buoyancy.'

The group Cephalopoda is divided into three subgroups: coleoids (including squids, octopuses and cuttlefishes), nautiloids (the nautiluses) and ammonites.

Ammonites' shells make the animals look most like nautiluses, but they are actually thought to be more closely related to coleoids.

'Some of their morphology was closer to that of the coleoid group,' says Zoë. 'We think it’s more likely that ammonites would have had eight arms rather than lots of tentacles like a nautilus, though the shell is more similar to that of a nautilus.'

Ammonites were born with tiny shells and, as they grew, they built new chambers onto it. They would move their entire body into a new chamber and seal off their old and now too-small living quarters with walls known as septa.

Ammonites looked a bit like nautiluses but are thought to be more closely related to coleoids, a group that includes octopuses and cuttlefish © Esteban De Armas/Shutterstock

Zoë adds, 'The ammonite would have lived in one chamber, but we don't know how often they built a new one.

'Previously it has been suggested this could have been a monthly occurrence, but there is no evidence for that. Some studies looking at the chemical composition of the shells - a field called sclerochronology - are starting to gain some insight of how long ammonites might have lived.'

Ammonites' growing shells typically formed into a flat spiral, known as a planispiral, although a variety of shapes did evolve over time. Shells could be a loose spiral or tightly curled with whorls touching. They could be flat or helical. Some species would begin growing their shell in a tight spiral but straighten it out through later growth phases. There were also some more unusual shapes - the species Nipponites mirabilis, which is found in Japan, is exceptionally rare and looks a bit like a knot.

Nipponites mirabilis ammonites grew in an unusual knot shape, rather than in a typical spiral

While ammonite shells are abundant in the fossil record, it was only recently that scientists have found a very rare fossil of the soft parts of an ammonite. However, fossilised evidence of ammonite arms is yet to be found.

Until now, a lot of what we know about ammonites has been inferred based on what we see in living cephalopods.

How old are ammonites?

The subclass Ammonoidea, a group that is often referred to as ammonites, first appeared about 450 million years ago.

Ammonoidea includes a more exclusive group called Ammonitida, also known as the true ammonites. These animals are known from the Jurassic Period, from about 200 million years ago.

Most ammonites died out at the same time as the non-avian dinosaurs, at the end of the Cretaceous Period, 66 million years ago.

Zoë says, 'We didn't quite lose all of them at the end of the Cretaceous. A few species continued into the Palaeogene in the Western Interior Seaway before dying out.'

The astroid that hit Earth 66 million years ago and ended the age of dinosaurs is also thought to have been responsible for the demise of most ammonites. Image by Donald E Davis courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech, via Wikimedia Commons

Read more

Why did ammonites go extinct?

At the end of the Cretaceous Period, an asteroid colliding with Earth brought on a global mass extinction. A lingering impact winter halted photosynthesis on land and in the oceans, which had a major impact on food availability and was devastating for ammonites.

Nautiloids, however, which had ancient relatives that lived at the same time as ammonites, survived this mass extinction. It is thought this is in part linked to these groups' preferred water depths.

Zoë explains, 'Nautilus survived probably because it lives deeper in the ocean. Deeper environments were less affected by what was going on in shallow water environments. This is a pattern that can be seen in other groups, aside from cephalopods – fish, for example.

Ammonites mostly died out 66 million years ago, but other cephalopods, such as nautiluses, survived © Manuae via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The size of hatchlings may also have played in the nautiluses' favour as they were larger and would have been less restricted by the size of food available to them.

How many ammonite species were there?

Scientists can tell species of ammonites apart through several attributes including shell shape, size, age, location, features such as the number and spacing of ribs, defensive spines or shell-strengthening ornamentation.

We know this specimen of Kosmoceras phaeinum is a male from the long prongs, known as lappets, sticking out near the opening of the shell. They might have been used by the male to hold onto the female during mating, a bit like shark claspers.

Read more

But figuring out exactly how many species have been found so far is a bit tricky.

Like modern cephalopods, ammonites displayed sexual dimorphism, which is the noticeable difference in appearance between sexes. But when ammonite fossils that looked unique were found in the past, they tended to be recorded as new species instead of as the microconch (male) or macroconch (female) of an existing species, as this difference between the sexes was not yet known about.

However, it is estimated that over 10,000 species of ammonite - possibly even over 20,000- have been discovered.

Zoë says, 'Ammonites were quite diverse and evolved rapidly, so if you sample stratigraphically through rocks, you can actually see the evolution and the changes through them.'

How big were ammonites?

Ammonites came in a range of sizes, from just a few millimetres to times bigger, with larger sizes more common from the Late Jurassic onwards.

The largest known species of ammonite is Parapuzosia seppenradensis from the Late Cretaceous. The largest specimen found is 1.8 metres in diameter but is also incomplete. If it were complete, this ammonite's total diameter could have been from 2.5-3.5 metres.

Parapuzosia seppenradensis is the largest known species of ammonite. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Where did ammonites live?

Ammonites lived all around the world. Like their modern-day cephalopod relations, they were exclusively ocean-dwelling. They tended to live in more shallow seas and may have had a maximum depth of about 400 metres.

What did ammonites eat and what ate them?

Though it would largely have depended on their size, ammonites would likely have eaten similar things to today's cephalopods, such as crustaceans, bivalves and fish. Smaller species would probably have eaten plankton. Some other species may have been scavengers, like living nautiloids can sometimes be.

Ammonites would also have served as food for other marine animals. There is evidence of mosasaurs and ichthyosaurs having eaten them, and some fish would likely also have considered them prey.

Ichthyosaurs were among the marine animals that would have preyed on ammonites

Why are ammonites important to science?

Ammonites can be a useful tool for scientists. Because they are so common and evolved so rapidly, they are excellent to help determine the age of the rocks they were fossilised in.

Much of the Mesozoic aged rock in Europe has been sectioned into 'ammonite zones', where rocks in different areas can be associated with each other based on the ammonite fossils found in them.

Zoë says, 'I've done a few identifications where there are bits of ichthyosaur and an ammonite has also been found, and they need it identifying. If you can identify the ammonite, you can really narrow things down. They're a really good indicator for biostratigraphy.'

Another potential use for ammonite fossils could be for telling us about how animals responded to climate change in the past.

Zoë explains, 'Shelled marine animals can help us look back into the past at what was going on in terms of climate change following extinction events. If we have known periods of warming or cooling, we can then infer that into modern climate science.

'Looking at size change will tell you an awful lot. Quite often after an extinction event a lot of shelled animals shrink because they don't have the resources they need to grow. If there isn't the resource to build their shells, it's a bit of a struggle for them. You see that in a lot of organisms.'

What is an ammonite? | Natural History Museum (nhm.ac.uk)

Ammonoidea

Animal

Ammonoids are extinct spiral shelled cephalopods comprising the subclass Ammonoidea. They are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) than they are to shelled nautiloids (such as the living Nautilus). The earliest ammonoids appeared during the Devonian, with the last species vanishing during or soon after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. They are often called ammonites, which is most frequently used for members of the order Ammonitida, which represented the only living group of ammonoids from the Jurassic onwards

Scientific name: Ammonoidea

Clade: Neocephalopoda

Domain: Eukaryota

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Mollusca

Ammonoidea - Wikipedia

Is an ammonite fossil worth money?

Well, the largest ammonites with special characters can fetch a very high value above $1,000. Most of them are below $100 though and the commonest ammonites are very affordable. Some examples : an ammonite Acanthohoplites Nodosohoplites fossil from Russia will be found around $150.

Ammonite fossil

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

All You Need to Know About Ammonite Fossils

Ammonites, which evolved about 416 million years ago, were once the most abundant animals of the ancient seas. Scientists have identified more than 10,000 ammonite species. Ammonites belong to a group of predators known as cephalopods, which includes their living relatives the octopus, squid, cuttlefish, and nautilus.

Where is Ammonite Fossils Found?

Ammonite quickly evolved into a variety of shapes and sizes including some shaped like hairpins. During their evolution, the ammonites faced no less than three catastrophic events that would eventually lead to their extinction.

Antarctica is well-known for its rich ammonite fossil sites. Among the most extraordinary ammonite species found in Antarctica is Diplomoceras cylindraceous, which could grow up to 2 meters long and is noted for its paperclip-shaped, uncoiled shell. In 1823, 12 years after her ichthyosaur discovery, Anning became the first person to unearth a complete skeleton of another prehistoric sea creature - the plesiosaur.

Small ammonite fossils formed when the remains or traces of the animal became buried in sediment which later solidified into rock. Ammonites were marine animals and had a coiled external shell similar to the modern pearly nautilus. Ammonites are one of the most common and popular fossils collected by amateur fossil hunters. Such marks are rare in the fossil record.

Ammonites are instantly recognizable by their spiraled coiling and peculiar ornamentation composed of ribs and tubercles - ridges that encircle the coils. Mostly all ammonite families had this similar coil shape, although there were also some non-spiraled forms called heteromorphs. It is this beautiful shaping that makes ammonite fossils so appealing to collectors.

Nowadays, ammonite fossils are often found in most sedimentary rocks from the Devonian to Cretaceous periods, and outcrops of these rocks can be found in mountains and sedimentary basins. Such outcrops include quarries, sea coasts, river shores, deserts, canyons, and even underground cellars. And many fossil stores offer ammonite fossils for sale.

Ammonite fossils have been found all over the world. They are commonly located in sedimentary rocks that are in marine environments. Ammonites evolved very rapidly, so they changed over time. For this reason, scientists often use ammonite fossils as index fossils to date a particular group of fossils.

Bottom Line

If you are interested in collecting fossils but don’t know where you can find authentic fossils at an affordable price, you can hop on to Fossil Age Minerals.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animal Crossing Fish - Explained #20

Brought to you by a marine biologist that still can’t believe we did ten of these, and holy crap here’s number twenty!...

Fish I’ve Covered: Click Here

Number 20, guys! WOW. Thanks all for following along. I figure here’s a great opportunity to cover one of the marine fossils and talk about something that isn’t a fish. I’ve been hearing rumors that Diving may come back to Animal Crossing, and that makes me real excited, since we’ll have so many more invertebrates to cover! In the meantime, let’s cover this one, an extinct relative of the cephalopods, the Ammonites:

The Ammonite fossil comes in just one piece, and it’s displayed as a single spiral shell on the left side of the first room in the fossil section of the museum. The left side is where all the invertebrates go, and honestly, that really gives people the wrong idea about life on Earth. I’ll rant about that another day, but if you know how to read a phylogenetic tree (the pattern on the floor) then you’ll see AC:NH put the Ammonite as the closest relative to a squid in a glass jar. That’s totally correct!

I really, really hope y’all let Blathers blab to you about the Real Facts(tm) about the stuff you donate to him, because he’s usually right about it! In AC: New Leaf, Blathers tells us that the Ammonite, as strange as it would seem, is more closely related to its shell-less cousins, the octopus and squid, than it is to the living shelled cephalopod, the nautilus. Here’s a prehistoric reconstruction (a scientific illustration about what the science and an artist think an extinct animal looked like in life) of an Ammonite by artist Mark Witton:

And here’s a living nautilus species, remember, not as closely related to the above as squids/octopuses are:

They look the same, but are totally different animals. Nautilids are thought to have appeared during the Cambrian while Ammonites appeared much later during the Devonian. It’s actually kind of difficult to find accurate illustrations of Ammonites, since for a long time, scientists also figured they had to be closely related to the nautilus. But, no, sorry, nature doesn’t make things easy. Those many, many sucker-less tentacles and the fleshy hood over the pin-hole eye is a definitely nautilus thing. Ammonites were found to have tiny teeth on their radula (a rasping tongue we know snails use to scrap food off hard surfaces) which is what octopuses have. That discovery put Ammonites and Octopuses/Squids closer together than either was to the Nautilids.

They also led completely different lives that spoke to incredible diversity and tragedy for the Ammonites. In New Horizons, Blathers tells you that Ammonite fossils are what we call “index fossils”, meaning that we can double check the time frame of other fossils more precisely by comparing where/when certain Ammonite species are discovered in the rock strata. That’s because Ammonites were insanely diverse. They evolved quickly thanks to their live fast/die young lifestyle, called “r-selection” if you want to get real college-level biology in this joint. Other animals that live this way are mayflies, mice, and of course, living squid species, among many others. It allows for many generations to pass in a short amount of time, with lots of offspring, and it makes it very easy to adapt to quick changes in the environment and bounce back from bad luck. Unfortunately, if you pair that kind lifestyle up with some bad limitations (like limited geographical spread and having a specific kind of food) one day, a catastrophe will get you, and that’s what happened to the Ammonites.

At the end of the Cretaceous Period, a giant space rock slammed into the Earth and killed all of the non-avian dinosaurs from the hell it wrought. But the dinos were far from the only poor bastards to get knocked out from this - the impact also caused acid rain, causing widespread ocean acidification that annihilated most shelled organisms living in shallow, surface waters, as the Ammonites did. These acidic seas dissolved their offspring as well as killed off a lot of the plankton they relied on. Although they survived somewhat into the Paleogene, of the Age of Mammals, it wasn’t long after that they finally kicked the bucket.

As for the nautilus? He was chillin’ in the deep sea, scavenging off whatever he could find, living a slow, long life, holding off on offspring until conditions were better. Now the Nautilus is here and the Ammonites ain’t.

And there you have it. Fascinating stuff, no?

#animal crossing#ac: new horizons#fish#fossils#ammonite#science in video games#animal crossing fish explained

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

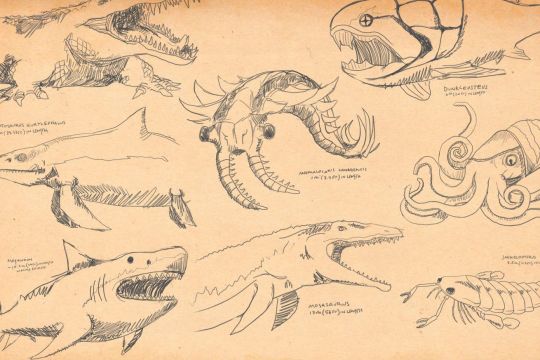

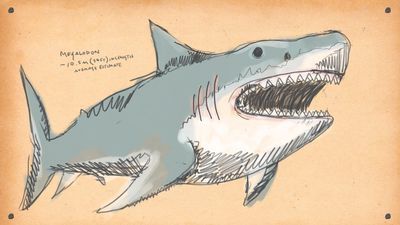

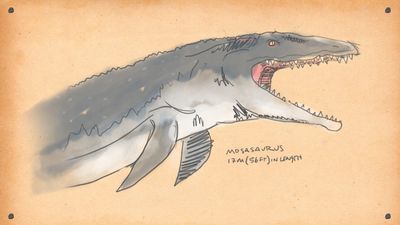

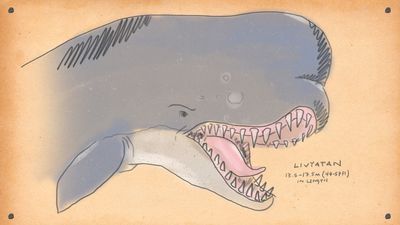

Here are 9 of the most badass animals ever to swim

Art by Tyson Whiting

Say hello to some horrifying sea monsters

This article was originally published on SB Nation a while ago, but was always intended for a Secret Base-y audience. So if you haven’t seen it yet, here you go!

The Earth has some very cool aquatic predators swimming about. Thanks to their intelligence and pack-hunting techniques, orcas are, perhaps, the most dangerous hunters ever to swim the ocean. Saltwater crocodiles are bulletproof murder tanks. And the great white shark, of course, needs no introduction. But now that we’re talking about terrifying underwater murder-beasts, why just settle for just the ones we have around now?

Underwater murder-beasts have a long and distinguished (pre-)history, and I thought it would be fun to introduce y’all to some new pals. TO THE IMAGINARY TIME MACHINE!

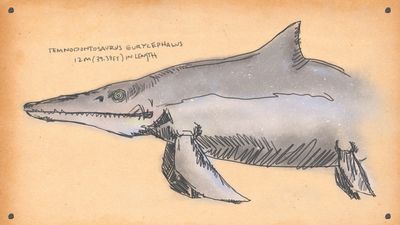

Temnodontosaurus eurycephalus

Grumpy croco-dolphin

Ichthyosaurs evolved 250 million years ago. In the aftermath of the Permian extinction, which killed off a frankly horrifying number of creatures, a group of terrestrial reptiles took to the depleted seas. Fast-forward a little bit and you have primitive ichthyosaurs, creatures so well adapted to oceanic life that they ended up looking like a cross between a crocodile and an extremely ill-tempered, extremely large dolphin.

Fast-forward even further, to the early Jurassic (175 million years ago), and you have Temnodontosaurus eurycephalus. It’s not the largest ichthyosaur ever to grace the seas, but it’s up there, and it’s a far more developed predator than its giant forebears. Somewhere around 30 feet long, T. emnodontosaurus was a powerful swimmer with strong jaws, well-equipped to chow down on other Jurassic swimmers. One closely-related species possessed the largest eyes of any known animal, perfect for hunting in deeper oceanic waters; another has been found with the remains of a different ichthyosaur in is stomach.

This monster considered 13-foot oceanic reptiles a delicious snack. It was also fast. Spare a thought for the poor ocean-going creatures minding their own business before one of these huge assholes rams into them from below at speed, opens those long, toothy jaws and turns them into lunch.

Deinosuchus hatcheri

Dinosaur hunter

Take a saltwater crocodile. Actually, it’s probably best not to. They are, after all, 20-foot, 2,000-pound apex predators more than happy to eat anything they come across, including you. Salties are strong, fast and surprisingly smart. They are at home in the open ocean as well as along the coast. Like all crocodiles, they’re ambush predators who use water as cover to attack their prey. Unlike most crocodiles they’re capable of jumping clear out of the water to get to it. They have the strongest bite of any living animal.

Right. Now that you have a saltwater crocodile in your head, make one, oh, twice as big. Yeah, like that. Decently boat-sized. Terrifying teeth in terrifying, dino-crushing jaws. Armored skin thick enough to turn aside more or less anything.

Your terrifying vision is Deinosuchus hatcheri, a crocodile adapted to more or less the exact same situation as a modern saltwater but in a world inhabited by giant dinosaurs. During the late Cretaceous (80 million years ago), North America was split by a shallow sea, the Western Interior Seaway. D. hatcheri was present on both the western side of the seaway (a slightly smaller species dominated the east), happily chowing through dinosaurs who were foolish enough to get too close.

Anomalocaris canadensis

Nightmare Shrimp

So far we’ve had a dolphin analogue in Temnodontosaurus and an actual crocodile. Cool, but nowhere near the sort of weirdness the past can provide. So let’s go to the deep, deep past, revealed wonderfully by the Burgess Shale. Here we shall find the NIGHTMARE SHRIMP.

One of the problems with studying the very earliest phase of animal life — we’re talking half a billion years at this point — is that it’s squishy, and squishy is not of much benefit when it comes to preserving fossils. Thanks to a fluke of geology, the conditions that produced the Burgess Shale were also capable of preserving soft tissue, giving palaeontologists a rare chance to look into what the seas looked like during the first days of the animal kingdom.

They looked extremely weird. The fauna found in the Burgess Shale was almost obnoxiously uncategorisable. One famous example is the worm Hallucigenia, which so confused everyone involved that it was reconstructed upside-down for the better part of a decade. Another is Opabinia, which looks sort of like a five-eyed miniature vacuum cleaner. I promise I am not making this up.

Anyway, all these critters were apparently food for the ocean’s first proper predator.

With good eyes set on flexible stalks and a surprising turn of speed, Anomalocaris canadensis cruised the Pre-Cambrian seas in death-shrimp mode. It was a full meter long, dwarfing most of its companions in the Burgess Shale. It was also delightfully strange-looking. It is so odd, in fact, that when it was discovered its various body parts were assigned to several different animals.

A. canadensis would be higher on this list if we could be sure of what it actually ate. Long-held to be a trilobite-hunter, recent studies have shown it would probably have had to restrict itself to soft-bodied prey due to relatively flimsy mouthparts, and therefore could only have actually eaten a trilobite just after a moult. But it’s much more fun to imagine this guy roaming the seafloor chomping down on everything, so that’s what we’ll do.

Disclaimer: an old friend of mine is a paleontologist who specializes in the Burgess Shale fossils. I did not contact him for this story, because I am consumed by envy whenever I so much as think about him.

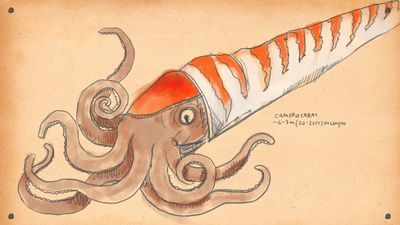

Cameroceras

Spiky death-squid

Back in the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic, cephalopods were armored critters, much like our modern nautilus. The most famous of them, and one of the most widely known extinct animals ever, is the spiral-shelled ammonite. Since they had hard shells, they’re extremely common in marine strata. They also got surprisingly large. The biggest-known ammonite was two meters across. Imagine that thing trying to swim.

Ammonites weren’t the only armored cephalopod prowling the ancient seas, however. The orthocones were straight-shelled versions, and some of those got really, really big. Like Cameroceras. Current estimates put Cameroceras’s shell at upwards of six meters long. That’s three average-sized men stacked on each others’ shoulders.

Somehow this monster was still able to get about in the Ordovician seas. It’s quite hard to imagine it chasing anything around, so it presumably surprised trilobites etc. at nighttime or dug it out of the mud, but since paleoecology is at least in part about imagination, right now I’m enjoying Cameroceras retracting its head deep into its shell and pretending to be a cave before trying to eat whatever entered. It wouldn’t be quite big enough to swallow the Millennium Falcon, buuuuuuuuut ...

Carcharocles megalodon

The shark that eats planets

Megalodon needs no introduction. The great white shark has a profound hold on popular culture, but its long-gone big sister isn’t far behind. Megalodon made even the most vicious shark in today’s seas look like a toy. Since sharks are mostly soft tissue, they don’t fossilize as well as we’d like, but their teeth do, and Megalodon’s tell a terrifying story.

Megalodon died out only relatively recently. It wasn’t quite contemporaneous with human beings, but its extinction was recent enough that there are plenty of folks willing to tell tall tales of how it might still be swimming somewhere in the depths of the ocean. If it was, probably best not to get anywhere near it — a Megalodon may have had a bite force of up to 10 times the strength of a great white. That’d be a bad day.

What were those huge jaws for? Whales. Apparently, these things liked to swim up from underneath its prey and bite through their chest to reach their internal organs. The ability to kill a whole-ass whale with one bite is honestly horrifying, even if whales in Megalodon’s day were a little smaller than the current batch of great rorquals.

Jaekelopterus rhenaniae

Sea Scorpion

Did you know ‘sea scorpions’ were a thing? Sea scorpions were a thing. Since eurypterids (to give them their proper name) went extinct hundreds of millions of years ago, we don’t have very good comparisons for what these things were like. So let’s get creative. Let’s take a lobster. Despite their ferocious armament, lobsters are relatively placid creatures. They’re not averse to grabbing a fish here or a mollusk there, but they’re not built for hunting. Let’s make the required tweaks.

We need to add eyes. Let’s make them big and sensitive and set for stereoscopic vision, which allows those pincers to be used more effectively to grab prey. Let’s make them better swimmers, too — we’ll add some paddles for agility and short bursts of speed. Let’s make their claws spikier, just for sheer scare value.

Oh and let’s make them 10 feet long and perfectly happy to eat you alive. Now you have a Jaekelopterus. Aren’t you glad they’re dead?

Dunkleosteus terrelli

A, uh, fish-tank

When evolution first came up with bone, it got a little bit carried away. Well, a lot carried away. The era of armored fishes is one of the most fabulously strange in the entire history of the planet. (A personal favorite of mine is Lunapsis, which looks like a fish had a baby with Batman’s utility belt.) With bone-plated heads and upper bodies, these fish probably didn’t swim very well, but who cares? They looked cool as hell, and with that body armor they were well protected against predators.

Which, as it turns out, is the sort of inspiration nature needs to come up with some better predators*. Enter Dunkleosteus, a monster armored fish with a set of jaws which could rip straight through the armor of any other fish slowly swimming through the Devonian ocean. Known to be 20 feet long, it didn’t really have teeth so much as a huge bony beak, which honestly makes the whole contraption even more frightening, like some sort of mobile oceanic guillotine.

*I’m being overly teleological here. Forgive me. Nature, of course, does not ‘come up with’ anything.

Mosasaurus hoffmanni

For whatever reason, the fauna of Cretaceous period got big. Really, really big. On land, we had Tyrannosaurus Rex. In the skies, azhdarchids the size of small aircraft coasted from thermal to thermal. And in the shallow seas, we had another monster: Mosasaurus.

Mosasaurus was essentially an enormous — estimates have it as almost 60 feet long — ocean-going lizard. Its legs were replaced with bladed paddles for maneuverability and it had a powerful tail for direct propulsion. Mosasaurus ate everything it could get in its mouth, which was a) double-hinged for extra capacity and b) already pretty capacious to begin with.

It would have hung around near the surface of the ocean, where there was an abundance of prey. Mosasaurus could have waited for other marine reptiles (such as Archelon, the largest turtle known) to come up to breathe, grab low-flying pterosaurs on fishing expeditions, or simply have picked off the many large fish that swam the Cretaceous seas.

Livyatan Melvilli

Moby-Dick’s even-scarier dad

In 1820, the Essex was lost in the southern Pacific Ocean. The ship had been sent out to hunt for sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus, since you asked), but soon had the tables turned when it was attacked and sunk by a ferocious bull. Of the 20 crew, only eight survived, and the incident went on to inspire a famous book about whales which you may have heard of.

What you probably haven’t heard of is Livyatan. Modern sperm whales are enormous creatures, but very rare boat attacks aside, they’re only really dangerous to their favorite prey, deep-swimming squid. But not so long ago, geographically speaking, there were also a group of ‘macroraptorial’ sperm whales. These didn’t eat squid. Instead, they competed with Megalodon to hunt other great whales.

Livyatan’s teeth are some of the most awe-inspiring fossils in the world. The biggest ones are 12 inches long and look like artillery shells. Estimates have Livyatan as sitting a touch smaller than its modern friends, but those teeth indicate that it would have been significantly more vicious, fully capable of cutting a sperm whale into very bloody chunks.

It’s not clear whether or not Livyatan hunted alone or in packs, like a modern killer whale, but it had the power and size to be able to plausibly compete with Megalodon even solo. The crew of the Essex found out that a bull sperm whale could be a formidable opponent; one suspects Livyatan would have left even fewer survivors.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

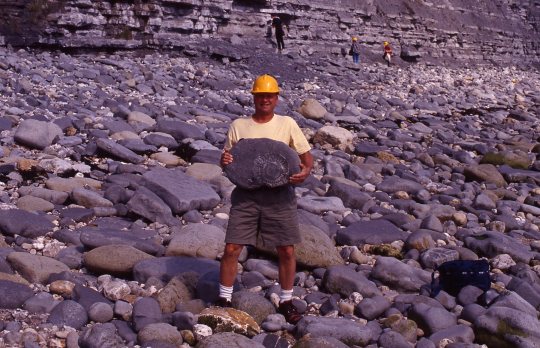

Cephalopod Fossils from Lyme Regis, England

My position as a Research Volunteer in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology (IP) allows me to delve into stories about the collection that I find interesting. One of my research assignments is to investigate the fossils from Lyme Regis, England. The Lyme Regis fossils are part of the 130,000 specimens purchased by Andrew Carnegie from the Baron de Bayet of Belgium in 1903. Some of the Bayet fossils are incorporated into the museum’s Dinosaurs in Their Time (DITT) in the Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous, and a special Lyme Regis case that showcases 13 invertebrate and vertebrate fossils.

The village of Lyme Regis is situated on the Dorset Coast, and as such, receives some of the worst weather associated with the English Channel. The Lyme Regis cliffs and beaches have been a fossil hunting graveyard for two hundred years, first made famous by resident Mary Anning (1799 – 1847). When she was just twelve years old she found a large skeleton of a marine reptile known as an Ichthyosaur (literally “fish lizard”). Ichthyosaurs were predators that fed on Jurassic fishes and ammonites. It’s easy to see how she developed a love of fossils after discovering such a magnificent creature as a child. For years, she amassed collections of plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, fish skeletons, and other marine fossils and sold them for a living to paleontologists worldwide. In DITT, there are two examples of Ichthyosaur specimens, a skull (CM 877) and a three-foot-long skeleton (CM 23822). Unfortunately, Mary Anning was not recognized during her life for her accomplishments, probably because she was not a trained paleontologist and she was female. After her death, the collections became widely known to the scientific community, bringing about a better understanding of the paleontology of the Dorset coast.

A fascinating piece of trivia about Lyme Regis is the filming of the 1980 movie, The French Lieutenant’s Women, which depicts the lead male actor, Jeremy Irons, using a simple rock hammer to extract a fossil ammonite from the cliff. If only it was that easy to collect from the 300-meter sheer cliff. My supervisor, Albert Kollar, collected fossils along the Lyme Regis beach in 1999. He opined “most fossils are eroded naturally because of the storm waves coming in from the English Channel that eat away at the rock each year, collapsing to the beach in broken blocks that eventually expose the fossils over time.”

My project was to research the Lyme Regis mollusks i.e., ammonites, nautiloids, and belemnites, update their identification, and review the climate aspects of the Jurassic sea that once covered this part of Europe approximately 199 to 190 million years ago. Paleontologists use marine fossils to interpret past paleoclimates and the paleoenvironments in which the animals once lived. The Jurassic is commonly considered as an interval of sustained warmth without any well-documented glacial deposits at the polar regions. The Lyme Regis fossils are preserved in very discrete layers of limestone strata often named “Lias” by European geologists. The terminology used today is early Jurassic Sinemurian Stage. The fossil mollusks are singular specimen’s that measure approximately 1 inch to 8 inches in diameter. The Carnegie of Natural History collection contains 16 invertebrate specimens from the genera Acanthoteuthis, Asteroceras, Eoderoceras, Liparoceras, Lytoceras, Microderoceras, Nautilus, Radstockiceras, and Xipheroceras.

All Bayet fossils were recorded in the Carnegie Museum Catalog of Fossils. The Cephalopod Catalog contains ammonite, nautiloid, and belemnoid fossils assigned by Bayet and includes details such as collection localities and stratigraphic horizon. Some Lyme Regis specimens are recognized by having two letters “BK” and a painted number, as seen on CM 40666. In 1975, a Swiss paleontologist, Dr. Felix Wiedenmayer, was on a research sabbatical to study fossil sponges at the Carnegie Museum, as well as an expert on Mesozoic ammonites from Europe. He reviewed many Mesozoic ammonites providing updated identification to genus and species, and stratigraphic horizon data, including some of the Lyme Regis ammonite fossils.

To complete the project, I created a virtual geology, paleontology, and exhibit folder in PowerPoint. This includes photographs of the specimens, a geologic map of Lyme Regis and the Dorset Coast, a Paleogeographic map, the distribution of genus and species in the collection, and references. The photographs in this study were taken by IP Research Associate/volunteer John Harper.

I have had a great experience at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History gaining knowledge about these fossil collections, stratigraphy, and geologic time. Now, I look forward to graduate school in part to study microfossils that lived in the seas during a climate “event” around 56 million years ago during the Paleogene Epoch. This event is called the “Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum” (PETM), and is so named because it demarcates the boundary between these two epochs of geologic time. It has been a pleasure looking at these exceptional cephalopods at the Carnegie Museum, and I look forward to any more potential collaborations in the future.

William Vincett is a research volunteer in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology and a graduate student at the University of Delaware. Museum employees and volunteers are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Invertebrate Paleontology#Lyme Regis#Bayet fossils#Carnegie Museum Catalog of Fossils#Fossil#Fossils

132 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cenoceras Fossil Nautilus – Cretaceous – Saint-Maixent-l'École, France – Alice Purnell Collection – 100% Genuine with Certificate

This listing features a scientifically valuable and beautifully preserved fossil nautilus of the genus Cenoceras from the Cretaceous period, found in the fossil-rich region of Saint-Maixent-l'École, France. This piece is part of the distinguished Alice Purnell Collection, known for its museum-grade, historically documented fossil specimens.

Cenoceras is a genus of extinct nautiloid cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to the Cretaceous. These marine molluscs were characterised by smooth, rounded shells and simple suture patterns. They are considered close relatives of modern nautiluses but display evolutionary traits unique to ancient oceans. With a coiled shell composed of internal chambers, Cenoceras used gas regulation to navigate the seas as a free-floating predator and scavenger.

This specimen offers excellent preservation, highlighting the classic coiling and chamber arrangement of the nautilus shell.

Geological Context: The Cretaceous period (145–66 million years ago) was a time of high sea levels and thriving marine ecosystems across Europe. The region of Saint-Maixent-l'École in western France is well known for producing marine fossils from Cretaceous sediments, including ammonites, nautiloids, and bivalves. Fossils from this area often show excellent preservation due to the fine-grained limestone and marl formations.

Key Details:

Genus: Cenoceras (Fossil Nautilus)

Fossil Type: Extinct marine cephalopod

Age: Cretaceous (~145–66 million years ago)

Location Found: Saint-Maixent-l'École, France

Provenance: From the Alice Purnell Collection

Condition: Very good preservation with visible shell form and coiling

Authenticity: 100% genuine specimen, supplied with a Certificate of Authenticity

Scale: Please refer to 1cm scale cube in the photo for full sizing

Photo: The actual specimen shown is what you will receive

Scientific & Display Value: Cenoceras fossils offer insight into the evolutionary path of nautiloid cephalopods and their role in ancient marine ecosystems. This example, from the trusted Alice Purnell Collection, is ideal for display, education, or research. Its rarity and provenance add to its collectability and value.

All of our Fossils are 100% Genuine Specimens & come with a Certificate of Authenticity.

Fast & Secure Shipping – Professionally packaged and dispatched promptly for safe delivery.

Add this elegant and historic marine fossil to your collection with this genuine Cenoceras nautilus fossil from the Cretaceous of Saint-Maixent-l'École, France.

#Cenoceras nautilus fossil#fossil nautilus France#Cretaceous marine fossil#Saint-Maixent-l'École fossil#certified fossil cephalopod#real nautilus fossil France#Cenoceras mollusc fossil#fossil from Alice Purnell Collection#nautiloid fossil Cretaceous#collector fossil France#marine invertebrate fossil

0 notes

Photo

Ammonites are an extinct group of marine invertebrate animals which died out at the end of the Cretaceous period. These mollusks are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e. octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish) than they are to shelled nautiloids such as the living Nautilus species.

Source: https://www.fossilera.com/fossils/6-polished-agatized-ammonite-cleoniceras-madagascar--10

173 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ammolite

While not the only fossil that is used as a gem (five pointed sea urchins spring to mind), the opal like sheening ammonite shell from the Rocky mountains of Canada and Utah is certainly the most beautiful. I have frequently seen it mislabelled as opal, or opalised ammonite, though it is actually fossilised nacre (0.3-0.8mm thick), similar to that of modern nautilus shells (living relatives of ammonites) or pearls, rather than any kind of replacement with silica. Dating from the late Cretaceous, the usually red or green sheen on the nacre is due to a phenomenon called thin film interference, something you all see in the sheen of petrol puddles on water. The thin layers of aragonite forming the shell reflect the light differently, creating waves of interference whose colour depends on the thickness of the plates, which are ofsimilar size to the wavelengths of light. Thicker layers produce reds and greens, and thinner ones the rarer blue and violets. Southern Alberta in the Cretaceous was a shallow sub-tropical inland sea, and the dead shells were preserved from decay in volcanic ash, that gradually altered into protective clays.

The colours are enhanced by polishing, and being a fragile material (Mohs hardness 4.5), thin slices of the shell are often used to make doublets or triplets (much like with opal), where layers of harder material such as dyed black onyx or quartz are used to protect the gem itself. As with opal, the wider the spread of playing colours as the stone is moved in bright light, the greater the value. Many different fracture patterns exist, caused by tectonic compression, with a variety of exotic names. Value is also negatively affected by the presence of cracks. It has also been stabilised with resins when exceptionally fragile. All such treatments are fully acceptable, as long as they are clearly declared.

The main commercial mine is in Southern Alberta, mining mostly fragments from the Bearpaw shale and finding about 50 intact specimens a year, whose export from Canada needs a permit. Nacreous ammonites occur worldwide, but the colours from here are the best, as is the suitability of jewellery use. The same care to avoid exposure to shock and caustic substances applies to ammolite as to pearls, unless it is protected in a triplet gem. Some only have one colour, others the full spread.

...

Loz

Image credit: The Boudreaux collection

http://www.gemsociety.org/info/gems/ammolite.htm http://www.rubybluejewelry.com/main_links/ammolite-history_mineralogy_and_lore.htm http://www.espyjewelry.com/index.cfm/fa/subcategories.main/parentcat/6442/subcatid/29574

207 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Almost-Living Fossils Month #12 -- The Other Nautiluses

Nautiloids are represented today by just two living genera (Nautilus and Allonautilus), but they have a lengthy evolutionary history going back almost 500 million years.

The peak of their diversity was during the first half of the Paleozoic, with many different shapes of shells from coiled to straight, then they began to decline when their relatives the ammonites and coleoids appeared and began to compete for similar ecological niches. Although a few groups of nautiloids survived through the end-Permian mass extinction, most of them had disappeared by the end of the Triassic, leaving just one major remaining lineage known as the Nautilina (or Nautilaceae).

During the mid-to-late Jurassic (~165 mya) two new groups split away from the ancestors of the modern nautiluses -- the cymatoceratids and the hercoglossids.

Cymatoceratids such as Cymatoceras sakalavum here had shells with a ribbed texture. Living during the Early Cretaceous, about 112-109 million years ago, this particular species is known from Japan and Madagascar and could reach a shell diameter of over 15cm (6″).

Hercoglossids, meanwhile, were much more smooth in appearance, but both groups also had more complex undulating sutures between their internal chambers than modern nautiluses do.

These nautiluses made it through the end-Cretaceous mass extinction and had a brief period of renewed success, filling the ecological roles left vacant by the extinct ammonites. But by the end of the Oligocene (~23 mya) both the cymatoceratids and hercoglossids vanished, possibly unable to deal with cooling oceans and the evolution of new predators.

Some of the hercoglossids’ Cenozoic descendants, the aturiids, managed to last a little longer into the Early Pliocene (~5 mya) before another period of cooling seems to have finished them off. Past that point, all that was left of the once-massive nautiloid lineage were their cousins the nautilids, who gave rise to today’s few living representatives.

(It’s also worth noting that the classification of the cymatoceratids seems to be in flux right now. Some paleontologists currently don’t consider Cymatoceras itself to actually be part of the group, instead being a nautilid much closer related to modern nautiluses. If this is the case then the cymatoceratids may not have actually survived past the Late Cretaceous -- but the Cymatoceras genus alone still counts as an “almost-living” fossil since its various species ranged from the Late Jurassic to the Late Oligocene.)

#almost living fossils month#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#hercoglossidae#cymatoceratidae#nautilina#nautilaceae#nautilus#nautilida#nautiloidea#cephalopod#mollusc#invertebrate#art#it's a peppermint

164 notes

·

View notes

Photo

These stunning Cleoniceras ammonite fossils date back to the Cretaceous period and were found in Madagascar! They have had skulls carved into them, making them into quite unique display pieces. Worldwide shipping is available! We are asking $25CAD (~18.95USD), buy them now on www.SkullStore.ca or in-store Thursday-Sunday (12-6pm) at 1193 Weston Rd, Toronto. Though they are more closely related to coleoids (squid, octopus, etc), these extinct critters resemble the modern day nautilus - their shells are also filled with spiralling chambers that aided in controlling their buoyancy.

#Ammonite#ammonites#vulture culture#carved skulls#skulls#skull collecting#fossils#fossil hunting#fossil collecting#paleontology#SkullStore#rockhounds#skull art

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Fossil of Mystery Lovers: Coloured Conch Gem (Ammonite Gem)

Ammonite is a species of fossil nautilus. Nautilus belongs in category to a prehistoric creature called cephalopods. Wikipedia defines cephalopoda as a class of mollusks.

Nautilus habitats still exist in the deep sea within the Republic of Palau, and general-grade nautilus fossils are scattered around the world. France, Germany, Madagascar, Morocco and other places are rich in nautilus fossils.

According to the definition of gem-quality Ammonites, the most authoritative GIA (International Gemological Association) in the world, only the fossils of Ammonites found in the prehistoric bear's paw seabed tectonic area in Alberta, Canada, can be defined as gem-quality Ammonites.

Coloured snails (Ammonites) are ancient fossils (organic)

There are various color. Purple is the rarest and most expensive.

They became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period, about 71 million years ago.

There are many origins, but only the colorful snails from Canada are gem grade.

Canadians found traces of colorful snails where they were fossilized. Spotted snails used to live in almost all the shallow sea areas. After they died, they sank to the sea floor and were wrapped by the seabed sediments.

After millions of years of crustal movement, extrusion, heating, subsidence, etc., most of them have become fragments. Some submarine sedimentary layers have been pushed to the surface by extrusion, and ammonites are usually wrapped in sedimentary rocks.

In Canada, the jewelry is usually made of small yellow ferritized colorful snails. Their shells are completely yellow ferritized. Cut them in half, and you can see the chamber structure inside the colorful snails.

These colorful snails (Ammonites) can be processed into pendants or earrings.

Some that cannot be further polished will be made into fossils.

Mystery lovers love this kind of thing. Ha ha ha, a product of nature! It is a fossil, a gem and a Feng Shui (Geomancy) stone. Filled with the energy, changes and history of the earth for hundreds of millions of years, it is one of the commonly used gemstones.

0 notes