#Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra

Text

John Lewis: A Jazz Pioneer

Introduction:

John Lewis was not only a visionary pianist and composer but also a pioneering force in the world of jazz. Born one hundred and four years ago today on May 3, 1920, in La Grange, Illinois, Lewis began his musical journey at a young age. His early exposure to classical music laid a strong foundation for his future endeavors in jazz.

Early Career and Influences:

Lewis’ career took…

View On WordPress

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

▶️ Dizzy Gillespie And His Orchestra – Oop-Pop-A-Da (1948)

Source: Internet Archive

20 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

The Dizzy Gillespie United Nation Orchestra

0 notes

Text

Today In History

Cabell “Cab” Calloway, accomplished bandleader, singer, dancer, songwriter, and author, was born in Rochester, NY, on this date December 25, 1907.

He learned the art of scat singing before landing a regular gig at Harlem’s famous Cotton Club. Following the enormous success of his song “Minnie the Moocher” (1931), Calloway became one of the most popular entertainers of the 1930s and ‘40s.

With other hits that included “Moon Glow” (1934), “The Jumpin’ Jive” (1939) and “Blues in the Night” (1941), as well as appearances on radio, Calloway was one of the most successful performers of the era.

He appeared in such films as The Big Broadcast (1932), The Singing Kid (1936) and Stormy Weather (1943). In addition to music, Calloway influenced the public with books such as 1944’s The New Cab Calloway’s Hepster’s Dictionary: Language of Jive, which offered definitions for terms like “in the groove” and “zoot suit.”

Calloway and his orchestra had successful tours in Canada, Europe and across the United States, traveling in private train cars when they visited the South in order to escape some of the hardships of segregation. With his enticing voice, energetic onstage moves and dapper white tuxedos, Calloway was the star attraction.

The standout musicians Calloway performed with include saxophonist Chu Berry, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and drummer Cozy Cole.

CARTER™ Magazine

#carter magazine#carter#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#history#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#cab calloway

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

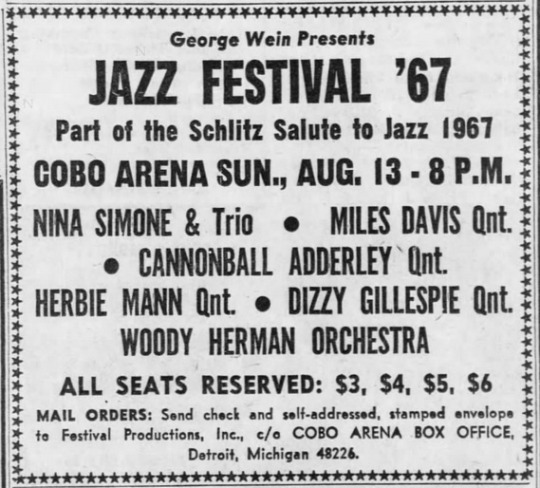

Jazz Festival '67 - Cobo Arena - Detroit

Nina Simone trio

Miles Davis Quintet

Cannonball Adderley Quintet

Herbie Mann Quintet

Dizzy Gillespie Quintet

Woody Herman Orchestra

#jazz#jazz ads#nina simone#miles davis#cannonball adderley#herbie mann#dizzy gillespie#woody herman#1967

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

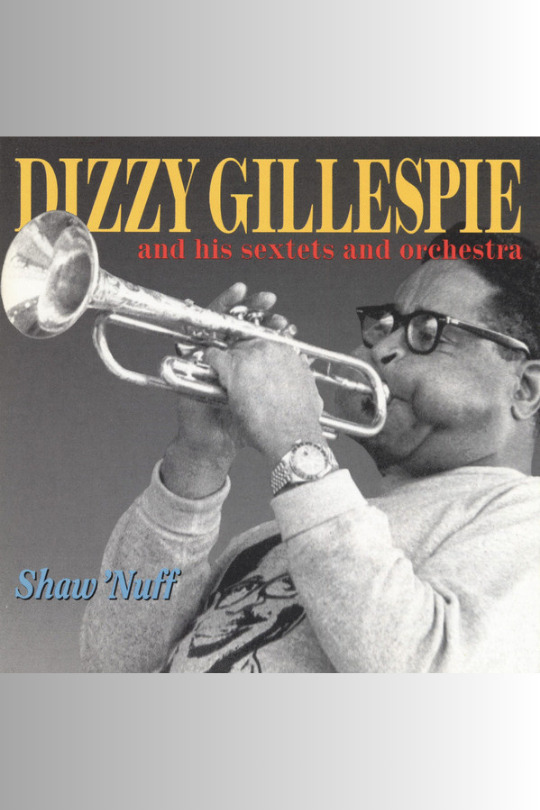

Dizzy Gillespie And His Sextets And Orchestra – Shaw ‘Nuff

“Those who only know Gillespie from his 1950s efforts onwards can have no conception as to the veritable force of nature his trumpet playing was in the 1940s. This CD collation of the earliest sides under his leadership, made for tiny labels such as Guild and Musicraft, will have your jaw sagging in amazement as he consistently delivers ideas that top even those of Parker. Just to keep it interesting, Gillespie also wrote some of the most enduring bop anthems, and many of them get their first outings here. These sessions, like the Parker Savoys, are the holy tablets of bop. ” (JazzWise).

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carmen Mercedes McRae (April 8, 1922 – November 10, 1994) was a jazz singer. She is considered one of the most influential jazz vocalists of the 20th century and is remembered for her behind-the-beat phrasing and ironic interpretation of lyrics.

She was born in Harlem. Her father, Osmond, and mother, Evadne (Gayle) McRae, were immigrants from Jamaica. She began studying piano when she was eight, and the music of jazz greats such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington filled her home. When she was 17 years old, she met singer Billie Holiday. As a teenager, she came to the attention of Teddy Wilson and his wife, the composer Irene Kitchings. One of her early songs, “Dream of Life”, was, through their influence, recorded in 1939 by Wilson’s long-time collaborator Billie Holiday. She considered Holiday to be her primary influence.

She played piano at an NYC club called Minton’s Playhouse, Harlem’s most famous jazz club, sang as a chorus girl, and worked as a secretary. It was at Minton’s where she met trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, bassist Oscar Pettiford, and drummer Kenny Clarke, had her first important job as a pianist with Benny Carter’s big band (1944), worked with Count Basie (1944) and under the name “Carmen Clarke” made her first recording as a pianist with the Mercer Ellington Band (1946–47). But it was while working in Brooklyn that she came to the attention of Decca’s Milt Gabler. Her five-year association with Decca yielded 12 LPs.

She sang in jazz clubs across the world—for more than fifty years. She was a popular performer at the Monterey Jazz Festival, performing with Duke Ellington’s orchestra at the North Sea Jazz Festival, singing “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore”, and at the Montreux Jazz Festival. She left New York for Southern California in the late 1960s, but appeared in New York regularly, usually at the Blue Note, where she performed two engagements a year through most of the 1980s. She collaborated with Harry Connick Jr. on the song “Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone”. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Aziraphale and “bebop:”

I’ve seen GO fans expressing confusion about Aziraphale’s animosity towards bebop, so I wanted to chime in about what I think is going on.

Bebop represented a sharp break from the more melodic big band/swing/dance orchestra styles of jazz that preceded it. It is a much more purely improvisational form of music, and it sounded jarring and discordant to people who were used to more traditional styles of jazz and pop. It was considered “musician’s music,” more designed to show off virtuosity than to be accessible to the listener.

Some of the older generation of jazz musicians were pretty hostile to bebop when it began to emerge in the early-mid 1940s. See, for example, the notorious clashes between Cab Calloway and Dizzy Gillespie when young Dizzy was cutting his teeth on the super edgy modern style during his time in Cab’s band. A lot of listeners must have reacted the same way at the time.

Aziraphale objects to bebop because it is jarring and new and bizarre to his ear. When your favorite “modern” music is stuff like the New Mayfair Dance Orchestra, bebop is going to sound weird as fuck. And because he is so slow to adapt to the way the world changes around him, any type of music from the last century or so that sounds jarring and new and weird to him (i.e., most of it) gets lumped into the category of “bebop.” It’s the eldritch immortal being equivalent of “Darn kids and their loud rock and roll music!”

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

CURTIS FULLER, LA REMARQUABLE RÉSILIANCE D’UN TROMBONISTE

"Curtis' playing was absolutely incredible... almost mystical. Curtis always said, 'I'm not trying to win any Trombone Olympics.' We all knew he could, but loved him because it was never his concern to 'out-play' anyone. He played too pretty and hip for that. He was all music."

- Steve Davis

Né le 15 décembre 1932 à Detroit, au Michigan, Curtis DuBois Fuller était le fils de John Fuller, un travailleur de l’industrie automobile, et d’Antoinette Heath. Immigrant originaire de la Jamaïque, le père de Fuller était décédé de la tuberculose avant sa naissance. La mère de Fuller, qui était originaire d’Atlanta, était morte d’une maladie des reins alors qu’il avait seulement neuf ans. Par la suite, Fuller avait passé dix ans à la Children’s Aid Society, un orphelinat opéré par les Jésuites.

Fuller avait commencé à se passionner pour le jazz après qu’une des religieuses de l’orphelinat l’ait emmené à un concert du saxophoniste Illinois Jacquet au Paradise Theatre de Detroit. Participait également au concert le légendaire tromboniste J. J. Johnson. Fuller n’avait jamais oublié sa première rencontre avec Johnson. Il avait précisé:

"He was coming out the side of the theater. He stopped and squeezed my hand, and he gave me that look — the J.J. Johnson look. And throughout the years, he never forgot me. And as I got older and went to school, and then went to the service and came out, I saw him again with Kai Winding, and he remembered me. When I got to New York, he told Miles [Davis] about me and about my progress. And as fate would have it, when he left to do his writing in Hollywood, I was chosen to do the two-trombone thing with Kai Winding and Giant Bones, and we had three albums."

Fuller avait fait ses études secondaires au Cass Tech High School de Detroit aux côtés de futurs grands noms du jazz comme Paul Chambers, Donald Byrd, Tommy Flanagan, Thad Jones et Milt Jackson. À l’époque, la ville de Detroit était en train de devenir une véritable pépinière du jazz. À ce moment-là, Milt Jackson et Hank Jones avaient déjà quitté Detroit pour New York et seraient bientôt suivis par de futures sommités du jazz comme Donald Byrd, les frères Elvin et Thad Jones, Paul Chambers, Louis Hayes, Kenny Burrell, Barry Harris, Pepper Adams, Yusef Lateef, Ron Carter, Sonny Red, Hugh Lawson, Doug Watkins, Tommy Flanagan et plusieurs autres.

À l’âge de seize ans, lorsqu’on avait demandé à Fuller de quel instrument il voulait jouer, il avait fixé son choix sur le violon et le saxophone, mais aucun de ces instruments n’étant disponible, il s’était rabattu sur le trombone. Décrivant sa découverte du trombone, Fuller avait commenté: “I saw symphony orchestras, but I didn’t see anybody like myself. That’s why when I saw J.J. . . . I said, ‘I think I can do this.’” Fuller avait appris le trombone avec des grands maîtres comme J.J. Johnson et Elmer James. Fuller avait été particulièrement influencé par Johnson, Jimmy Cleveland, Bob Brookmeyer et Urbie Green.

Déjà déterminé à devenir musicien de jazz, Fuller avait ajouté deux ans à son âge afin d’augmenter ses chances d’obtenir du travail.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

Après avoir décroché son diplome du High School en 1955, Fuller avait fait un séjour dans l’armée dans le cadre de la guerre de Corée. Stationné à Fort Knox, au Kentucky, Fuller avait joué dans un groupe qui comprenait Chambers, Junior Mance et les frères Cannonball et Nat Adderley. Après sa démobilisation en 1955, Fuller avait commencé à se produire dans des clubs locaux tout en poursuivant parallèlement ses études à Wayne State University. Par la suite, Fullers’était joint au quintet du saxophoniste Yusef Lateef, un autre musicien originaire de Detroit. Il avait aussi joué avec Kenny Burrell.

Après s’être installé à New York en avril 1957, Fuller avait enregistré trois albums avec le groupe de Lateef. Un de ces albums avait été produit par Dizzy Gillespie pour les disques Verve. Après avoir enregistré avec le saxophoniste ténor Paul Quinchette, Fuller avait participé en mai de la même année à ses premières sessions d’enregistrement comme leader avec les disques Prestige. Intitulé Transition, son premier album comme leader avait été publié en 1955.

Parmi les membres du groupe de Fuller, on retrouvait Sonny Red au saxophone alto. Comme ses compatriotes Kenny Burrell et Thad Jones l’avaient fait l’année précédente, Fuller utilisait principalement des musiciens de Detroit dans le cadre de ses enregistrements.

Le producteur Alfred Lion, le co-fondateur des disques Blue Note, avait entendu jouer Fuller pour la première fois avec le sextet de Miles Davis au Cafe Bohemia à la fin des années 1950. Fuller avait éventuellement dirigé quatre sessions comme leader pour Blue Note, même si une de ces sessions (mettant en vedette le tromboniste Slide Hampton) n’avait pas été publiée avant plusieurs années. Lion avait également inclus Fuller dans des sessions dirigées par le pianiste Sonny Clark (albums Dial "S" for Sonny et Sonny's Crib enregistrés respectivement en 1957 et 1958) et John Coltrane (sur l’album Blue Trane en 1957).

Après avoir passé seulement huit mois à New York, Fuller était devenu un participant incontournable des sessions organisées par les disques Blue Note. À ce moment-là, Fuller avait déjà enregistré six albums comme leader et avait fait des apparitions sur une quinzaine d’autres sessions dirigées par d’autres musiciens. Fuller expliquait: "Alfred brought me into dates with Jimmy Smith and Bud Powell. And then we did Blue Train with John Coltrane. And I became the only trombone soloist to record with those three artists." C’est d’ailleurs un peu grâce à Fuller que Coltrane avait rebaptisé une des pièces de l’album "Moment's Notice." Le titre de la pièce faisait référence à une remarque de Fuller qui s’était plaint que le saxophoniste n’avait donné que trois heures à ses musiciens pour se préparer à l’enregistrement des pièces plutôt complexes l’album. Outre Fuller et Coltrane, l’album avait été enregistré avec une formation composée du trompettiste Lee Morgan, du contrebassiste Paul Chambers, du pianiste Kenny Drew et du batteur Philly Joe Jones. De tous les albums auxquels Fuller avait participé, Blue Train était d’ailleurs son préféré.

Peu après avoir enregistré Blue Train, Fuller avait joué avec Lester Young au club Birdland. Il expliquait: "I remember talking to Billie Holiday about being surprised that Lester wanted me. She said, 'Well, he asked for you. He must've wanted you.'" Après la mort de Young, Fuller se préparait à retourner à Detroit lorsqu’il avait reçu une offre du saxophoniste ténor James Moody. Après avoir fait une tournée avec le big band de Dizzy Gillespie, Fuller avait même failli se joindre au groupe de son idole Louis Armstrong. À l’époque, le tromboniste d’Armstrong, le légendaire Trummy Young, était sur le point de quitter le groupe, car il avait décidé de devenir prêtre. Fuller précisait:

"Trummy told me he got $1,500 a week. I started spending the money in my mind. Those were the early days. If you had $300 or $400 a week, you thought you were rich. Trummy was a mainstay with the group, and he was telling Pops about me — I got a little man, you gotta hear him. He took me to rehearse for him, and I heard Pops talking, and he said, 'Nah, too much bebop. I don't like that stuff.' I started crying. Louis Armstrong, my hero, didn't like me. My whole world crashed down on me."

Fuller avait finalement décidé de prendre le rejet d’Armstrong avec philosophie. Comme il l’avait déclaré avec humour: "He didn't like Dizzy, either, so I don't feel bad."

Un des premiers albums de Fuller comme leader, intitulé Bone & Bari (1957), mettait en vedette une formation composée de Tate Houston au saxophone baryton, de Sonny Clark au piano, de Paul Chambers à la contrebasse et d’Art Taylor à la batterie.

Dans le cadre de sa collaboration avec Blue Note, Fuller avait participé à des sessions avec Bud Powell, Jimmy Smith, Clifford Jordan, Hank Mobley (albums The Opener en 1957 et A Caddy For Daddy en 1966), Wayne Shorter (sur l’album Schizophrenia en 1969), Lee Morgan (albums City Lights en 1957 et Tom Cat en 1980) et Joe Henderson (Fuller connaissait bien Henderson pour avoir été son camarade de classe à Wayne State University en 1956). Lorsque sa carrière comme leader avait commencé à s’essoufler, Fuller avait collaboré avec James Moody, Dizzy Gillespie et Billie Holiday. C’est d’ailleurs Billie qui avait conseillé à Fuller de commencer à trouver son propre son dans le cadre de ses improvisations. Fuller expliquait: “When I came to New York, I always tried to impress people, play long solos as fast as I could—lightning fast. And all of a sudden Billie Holiday said, ‘When you play, you’re talking to people. So, learn how to edit your thing, you know?’’’ I learned to do that’’, avait conclu Fuller.

En 1959, Fuller avait fait partie des membres fondateurs du Jazztet d’Art Farmer et Benny Golson. Fuller connaissait déjà Golson pour avoir participé à l’album The Other Side Of Benny Golson à la fin de l’année 1958. La complicité du duo était telle que Fuller avait invité Golson à participer à son album Blues-ette en 1959. La même année, Fuller avait retourné l’ascenseur à Golson en collaborant à trois de ses albums pour Prestige avec différentes sections rythmiques. Le duo avait également collaboré dans le cadre de deux albums de Fuller pour les disques Savoy, ce qui avait jeté les bases du futur Jazztet. Le nouveau groupe, un sextet, avait enregistré son premier album en février 1960. C’est également dans le cadre de cet album que le pianiste McCoy Tyner avait fait ses débuts sur disque. Même si le groupe avait connu un grand succès dès le départ, Fuller et Tyner avaient quitté quelques mois plus tard pour se consacrer à leurs propres projets.

À l’été 1961, Fuller s’était joint aux Jazz Messengers d’Art Blakey, transformant ainsi le groupe en sextet pour la première fois de sa longue histoire. Avec Wayne Shorter, Cedar Walton, Jymie Meritt (bientôt remplacé par Reggie Workman) et Freddie Hubbard, Fuller avait contribué à faire du groupe une des plus importantes formations de hard bop de l’histoire. Fuller était demeuré avec les Jazz Messengers jusqu’en février 1965. Dans le cadre de sa collaboration avec le groupe, Fuller avait perfectionné ses talents de compositeur en écrivant des classiques comme “A La Mode”, “Three Blind Mice” et “Buhaina’s Delight.”

Au début des années 1960, Fuller avait également enregistré deux albums comme leader pour les disques Impulse. Il avait aussi enregistré pour Savoy Records, United Artists et Epic à la fin de son contrat avec Blue Note. À la fin des années 1960, Fuller avait fait une tournée en Europe avec le big band de Dizzy Gillespie qui comprenait également Foster Elliott au trombone.

Dans les années 1970, Fuller avait expérimenté durant un certain temps avec un groupe de hard bop qui utilisait des instruments électroniques. Il avait aussi dirigé un groupe comprenant le guitariste Bill Washer et le bassiste Stanley Clarke. Cette collaboration avait éventuellement donné lieu à la publication de l’album Crankin‘ en 1973.

Après avoir de nouveau voyagé en tournée avec Count Basie de 1975 à 1977, Fuller avait enregistré avec plusieurs compagnies de disques, dont Mainstream, Timeless et Bee Hive. De 1979 à 1980, il avait également co-dirigé le groupe Giant Bones avec le tromboniste Kai Winding. À la fin des années 1970, Fuller avait aussi joué avec Art Blakey, Cedar Walton et Benny Golson.

DERNIÈRES ANNÉES

Dans les années 1980, Fuller avait fait de nombreuses tournées en Europe avec les Timeless All-Stars. Doté d’une remarquable résiliance, Fuller avait de nouveau collaboré avec le Jazztet de Benny Golson après avoir vaincu un cancer du poumon en 1993.

Fuller avait épousé Catherine Rose Driscoll en 1980. Le couple avait eu trois enfants: Paul, Mary et Anthony. Fuller avait également cinq enfants de son mariage précédent avec Judith Patterson: Ronald, Darryl, Gerald, Dellaney et Wellington. Driscoll est décédée d’un cancer du poumon le 13 janvier 2010. Fuller avait enregistré l’album The Story of Cathy & Me l’année suivante pour lui rendre hommage. Tout en continuant de se produire sur scène et d’enregistrer, Fuller enseignait à la New York State Summer School of the Arts (NYSSSA) School of Jazz Studies (SJS). Il avait aussi été professeur à la Hartt School de l’Université Hartford.

Fuller donnait également de nombreuses cliniques dans des collèges et des universités comme le Skidmore College, l’Université Harvard, l’Université Stanford, l’Université de Pittsburgh, l’Université Duke, le New England Conservatory of Music et le John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, où il avait servi de mentor à de jeunes artistes de la relève comme la saxophoniste Caroline Davis et le contrebassiste Dezron Douglas.

Curtis Fuller est mort le 8 mai 2021 dans une maison de retraite de Detroit à l’âge de quatre-vingt-huit ans. Le décès de Fuller avait été confirmé par sa fille Mary Fuller ainsi que par son associée Lilly Sullivan. Même si la cause exacte de la mort de Fuller n’avait pas été dévoilée, il semblait souffrir de problèmes de santé depuis plusieurs années. Fuller avait enregistré un dernier album intitulé Down Home en 2012. Ont survécu à Fuller ses enfants Ronald, Darryl, Gerald, Dellaney, Wellington, Paul, Mary et Anthony, neuf petits-enfants et treize arrière-petits-enfants.

Fuller avait enregistré plus de trente-six albums comme leader de 1957 à 2018. Il avait également collaboré à environ 400 albums avec d’autres grands noms du jazz comme Bud Powell, Lee Morgan, Quincy Jones, Dizzy Gillespie, Lionel Hampton, Jimmy Heath et Count Basie. Reconnu pour sa tonalité riche et profonde, plus particulièrement dans les pièces au tempo rapide, Fuller était également caractérisé par son sens du rythme et sa technique impeccable. Réputé pour son professionnalisme et son tempérament détendu, Fuller était aussi reconnu pour son redoutable sens de l’humour.

Décrivant le style de Fuller, le tromboniste et compositeur Jacob Garchi avait déclaré: "His sound was massive, striking and immediate, a waveform that was calibrated to overload the senses and saturate the magnetic tape that captured it. In our era of obsession with harmony and mixed meters, Curtis Fuller's legacy reminds us of the importance of sound." Penchant dans le même sens, un autre tromboniste et professeur, Ryan Keberle, avait ajouté: "Curtis Fuller's genius can be heard in the warm and vibrant timbre of his trombone sound and the rhythmic buoyancy, and his deeply swinging sense of time." Quant à Mark Sryker, l’auteur de l’ouvrage Jazz From Detroit publié en 2019, il avait commenté: "Fuller was strongly rooted in the fundamentals of blues, swing and bebop, and his improvisations balanced head and heart in compelling fashion. He married a lickety-split technique with soulful expression, and even in his early twenties, he had a distinctive identity ideally suited for the hard-bop mainstream." Le tromboniste et professeur Steve Davis, qui connaissait Fuller depuis le milieu des années 1980, avait précisé: "Curtis' playing was absolutely incredible... almost mystical. Curtis always said, 'I'm not trying to win any Trombone Olympics.' We all knew he could, but loved him because it was never his concern to 'out-play' anyone. He played too pretty and hip for that. He was all music."

Fuller semblait d’ailleurs faire l’unanimité auprès des trombonistes. Ainsi, le tromboniste et compositeur Craig Harris avait déclaré: “Curtis Fuller was Gracious and Giving and always encouraging to young musicians. Being a trombone player myself I always marveled the way he combined Spirit, Sound and Skill to create one of the most unique voices on the instrument.” Un autre tromboniste et compositeur, Dick Griffin, avait précisé: “Curtis Fuller what a dear friend and mentor. I really looked up to him as one of the trombone players I put at the top of my list along with the master J.J. Johnson. I really appreciate the respect he gave me as a trombone player.”

Le Berklee College of Music a accordé un doctorat honorifique en musique à Fuller en 1999. Il a été élu ‘’Jazz Master’’ par la National Endowment for the Arts en 2007. Il s’agit du plus important honneur pouvant être accordé à un musicien de jazz aux États-Unis.

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

KENNY DORHAM

(English / Español)

Kenny Dorham, (August 30, 1924, Fairfield, Texas, United States - December 5, 1972, New York, United States), was an enormous and magnificent trumpet player while he lived. Gifted with a lyrical phrasing in the hardbop style of music, he was always characterized by a spectacular trumpet phrasing. His musical beginnings were neither more nor less as an outstanding trumpet player in 1945 in the orchestra of two bebop musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie and Billy Eckstine. The magnificent work developed in those formations, earned him that Charlie Parker himself incorporated him to his quintet during the years 1948 and 1949. His next job was with drummer Art Blakey, who incorporated him into his newly formed combo "The Jazz Messengers".

At that time he formed a small group he called "The Jazz Prophets" and when Clifford Brown died, the great drummer Max Roach called him to take his place in his quintet, which he did during 1956 and 1958. In spite of this formidable competition, Dorham always kept the bar high and his time in the quintets of Charlie Parker first and Max Roach later on, elevated him to the top of the hard bop trumpet players' podium.

Kenny Dorham left for posterity a song entitled "Blue Bossa" that has become part of the repertoire of modern jazz classics and, together with numerous arrangements for other musicians, earned him a well-deserved reputation as an efficient and inspired composer.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Kenny Dorham, (30 de agosto de 1924, Fairfield, Texas, Estados Unidos – 5 de diciembre de 1972, Nueva York, Estados Unidos), fue un trompetista enorme y magnifico mientras vivió. Dotado de un fraseo lírico dentro de un estilo musical duro como es el hard bop, siempre le caracterizó un espectacular fraseo a la trompeta. Sus comienzos musicales fueron ni mas ni menos como trompetista destacado en 1945 en las orquesta de dos músicos del bebop como fueron, Dizzy Gillespie y Billy Eckstine. El magnifico trabajo desarrollado en esas formaciones, le valió que el mismísimo Charlie Parker lo incorporara a su quinteto durante los años 1948 y 1949. Su siguiente trabajo fue con el batería Art Blakey, quien lo incorporó a su recién formado combo «The Jazz Messengers».

Por aquella época formó un pequeño grupo al que denominó «The Jazz Prophets» y cuando murió Clifford Brown, el grandioso batería Max Roach, lo llamó para que ocupase su lugar en su quinteto, lo que hizo durante los años 1956 y 1958. A pesar de esa formidable competencia, Dorham siempre mantuvo el listón alto y su paso por los quintetos de Charlie Parker primero y de Max Roach después, le encumbraron hasta lo más alto del podium de los trompetistas del hardbop.

Kenny Dorham, dejó para la posteridad un tema titulado «Blue Bossa» que ha pasado a engrosar el repertorio de clásicos del jazz moderno y junto a numerosos arreglos para otros músicos, le valieron para ganarse una merecida reputación de compositor eficiente e inspirado.

Fuente: apoloybaco.com

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music History Today: April 25, 2023

April 25, 1917: Ella Fitzgerald was born in Newport News, Virginia. Dubbed “The First Lady of Song,” she became the most popular female jazz singer in the United States for over half a century. In her lifetime, she won 13 Grammy awards and sold over 40 million albums.

Her voice was flexible, wide-ranging, accurate, and ageless. She could sing sultry ballads and sweet jazz and imitate every instrument in an orchestra. She worked with all the jazz greats, from Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Nat King Cole, to Frank Sinatra, Dizzy Gillespie, and Benny Goodman.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charlie Persip: The Drummer Who Kept Jazz Swinging

Introduction:

Charlie Persip, born Charles Lawrence Persip ninety-five years ago today on July 26, 1929, in Morristown, New Jersey, was an influential jazz drummer, bandleader, and educator. Known for his dynamic drumming style and impeccable sense of rhythm, Persip’s contributions to jazz spanned several decades, during which he played with some of the most iconic figures in the genre. His…

#Al Germansky#Billy Eckstine#Charles Persip and the Jazz Statesmen#Charlie Persip#Dizzy Gillespie#Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra#Dizzy in Greece#Eric Dolphy#Freddie Hubbard#Gene Ammons#Harry "Sweets" Edison#Jack McDuff#Jazz Drummers#Jazz History#Jazz Statesmen#Randy Weston#Roland Alexander#Ron Carter#Sonny Stitt#Soul Summit#Uhuru Afrika#World Statesman

1 note

·

View note

Text

Seen Part II

Just before Mary Sue had thought herself to tears, Steven finally mercifully engaged her after a couple hours of sitting through the rumbling white noise that he and his gaggle counted as conversation. “We’re gonna head down the block to the Lower Loft.” Another wannabe edgy, ironic name for another bland place that catered to bland people, she thought. She shoved her phone into her jacket pocket as she slid her arms into the sleeves and exited one stuffy bar into a brief respite of fresh night air before, she assumed, walking right into another, virtually identical one except for the name. Her first breath outside the door was cool and awakening, not only from the open space and temperature drop, but because of the change in sound. She heard music. She turned her eyes to a trio of bearded buskers; a battery powered keyboard balanced on a lap, a slouching trumpet player, and a single snare drummer sitting in cheap latticed folding lawn chairs on the corner of the street Mary Sue was prepared to cross with this gang she didn’t belong to. She recognized the song and stepped away, drawn almost magnetically to the thick nostalgia in the tune. She decided to put money in the upturned hat sitting between the trumpet player’s heavy-booted feet. He reminded her so much of Joe, even beyond the conspicuous shoes, and the trumpet, not a common instrument to play at all, much less play for change on a public corner. It was the way he sat with his knees spread wide, and terrible, too relaxed, seemingly lazy posture. He’d never make it in an orchestra with all of its formality, or even a semi-serious jazz ensemble, although he clearly cared for his instrument and the music and played it beautifully. It was the way he involuntarily kept time with the heel of his left foot; the way he guarded the money without looking menacing. No one was going to steal that money from in front of him, but no one would be nervous about approaching him to drop more in, either.

Some wistful semblance of happiness must have crossed her face, obvious enough to be noticed by people who barely paid her any attention. “It’s probably a scam of some kind. Those people are one step up from begging for money, Ems. They’re panhandlers with instruments instead of sob story cardboard signs.” Steven clutched her elbow, holding her back from what she wanted. He could never just let her be happy and like anything.

“They’re talented. I love this song. Haven’t you ever heard La Vie En Rose?”

“No. Of course you know French instrumentals. It’s honestly cliché that you like every piece of highbrow art you come across. Oh classical music; oh art museums; oh ballet. Like...you’re trying too hard, Ems. But how do they know a French instrumental? It’s probably the only song they know so they can entrap bleeding heart wannabe connoisseurs like you and weasel them out of some money.” Now he implied her music taste was too haughty and high class for who she was, on top of impugning the musicians, whom he didn’t know at all. More evidence that he didn’t know her at all, nor did he care to; her music taste was all over the place. He didn’t see her. He looked right through her all the time. And the realization struck her then that she didn’t want him to see her anymore; she didn’t want to see him anymore.

“French instrumentals? It’s a Louis Armstrong classic. You’re such a nasty classist cynic sometimes. Who says a hard working guy in work boots can’t love music? Can’t know how to play an instrument well?” Joe could (and did) play jazz from Louis Armstrong and Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie and he could play symphonic pieces by Haydn and Tchaikovsky and he could play ska from Save Ferris and Reel Big Fish. By ear. He’d never had a music lesson beyond his grandfather giving him that trumpet and showing him which buttons to press to make which notes. That contented look must have spread over her again.

Steven increased the intensity of his hold on her elbow. “I mean it, Ems. Don’t give those people any money.”

Mary flashed back to meeting Steven’s family after their first couple months of dating. They’d suggested McDonald’s. At first, Mary was a bit affronted, thinking they’d chosen something so common and inexpensive as a comment on her and where she came from, but Steven had never divulged anything about her background to his parents. Perhaps he never considered her background as anything to consider beyond teasing and critiquing her himself, which, she supposed, was enlightened, for him, anyway. After her initial mild offense, she used McDonald’s as a point of commonality. She really wasn’t that different from Steven and his family and his crowd of peers, after all; they both chose McDonald’s as the place to go when they weren’t eating at home. But McDonald’s was a treat for Mary Sue growing up because that’s all her family and friends could afford as a splurge, while Steven’s family chose to eat there because they didn’t have to tip. Over the past year, more and more differences in values presented, and because of the make-shift band outside the bar, Mary at last reached her tipping point. She pulled away from Steven’s pinching grip on her arm with a rumpled five dollar bill in her hand and scampered to the hat, already brimming with small bills and coins when the song ended. As the trumpet player thanked her in his gruff but sincere mumble, she locked into eye contact with him and saw that it was Joe. Her Joe. She didn’t recognize him looking at him outside from inside that pretentious downtown bar with the beard he never used to wear and his hat pulled down low over his tender brown eyes, and she felt idiotic and ridiculous for not seeing him from a distance anyway. She did still see him. Something drew her back to him; something about how he sat and how he played and how he was called out to her despite the disguise that time and place and facial hair and strained connection tried to hang on him in her upward-mobility-blurred eyes. Even when she thought of the ugliness that split them apart; even when she thought of how mad at each other they were; how defeated they were; and how hopeless any eventual reconnection seemed after that catastrophic explosion (the one she felt was justified and understandable now in its entirety), and the drunken disappointment, she still saw him as Her Joe.

A slow, welcoming smirk of pleased recognition further warmed his face, already reddened from the exertion of breath control and a breezy night playing outside. “Hey, stranger,” he said.

“You look like a stranger.” He stroked his beard, still palming the trumpet in one hand, and shrugged in acknowledgment.

“You don’t.”

“I don’t wanna interrupt your...gig.”

He laughed. “My ‘gig.’ That’s...so you, Rice Chex.” He shook his head with lingering snickers before he continued. “Hat’s full now, and it’s getting a little windy, so we were gonna pack up. Louis Armstrong’s a strong closer. Gig’s...finished. Unless you got a request,” he hinted.

“You already played La Vie En Rose. I mean...” she impishly rolled her eyes to the sky and puckered her lips in a restrained grin.

“Right? Earned us five bucks and me a breakneck ride down memory lane. I made the guys learn that song for you.”

“You’re so fulla shit, Joey,” she giggled in spite of herself and turned away from the other young men and more toward Joe with some heady mix of modesty and elation. She was certain he was kidding her, but even in jest it was a firmer link and keener awareness of her and who she was at her core than anyone else she’d been anywhere near in the past several years.

“Nah, he’s dead serious,” the keyboard player said as he watched the drummer split the money from the hat in as close to even thirds as he could without losing any. There was no sarcasm in his statement, and Mary Sue was imminently even more flattered.

“Guys, this is Mary Sue Rice,” Joe said, not looking away from her.

“We figured, man. We’re not stupid,” the keyboardist scoffed.

“That’s Ethan on drums and Will on keys. When we play, we always play La Vie En Rose. ‘Cause that’s...you.”

“And the original. But we hardly ever play that one,” said the drummer, pocketing his share of the money. The keyboardist mirrored him.

“You wrote...a song?! I wanna hear the original,” Mary Sue spouted. The two musicians she’d just met looked uneasily to Joe. Joe still looked up at her from his seat as he cased up his nearly 70 year old trumpet. She figured that meant ‘no,’ and her eyes fell closed with miscalculation and discouragement.

“Mary Sue Rice wants to hear ‘See Me,’ guys. Think we can do just that one encore before we pack up?” Joe asked, knowing they’d agree, and still not moving his eyes from hers. Ethan tapped out a gentle rhythm and Will began the melancholy melody of a ballad with a few soulful notes before Joe began softly singing, intentionally quiet so other passers-by kept on passing them by.

See Me

Shoulda known when I met her.

And looked it up in reference text.

Though she'll always be better

Than whoever's coming next.

Mary Sue means perfect, you know.

I finally got the definition.

So I surrender, babe. I'll leave, I'll go.

I'm finally out of ammunition.

I'm settling for memory.

Gonna be the bigger man, and let her be free.

But I wish she could see me.

Still no place I can travel,

No book to read between the lines of,

And every plan I watch unravel

Makes me think of our almost love.

Still feels like a crime,

But I know I didn't hurt her.

Still wish to turn back time

Try again, just to be sure.

But I'm settling for memory.

Gonna be a better man and let her be free.

Still wanna scream, “See me, see me!”

I couldn't put enough light in those dark brown eyes.

And I know this dull ache will never go away.

But I'd grown weary, giving her old college tries,

And I just didn't have it in me to stay.

She was right, I guess. Without me she was best.

I was kidding myself to think we'd last.

I'm always gonna put her a little higher than the rest.

But I know there's no future living in the past.

I'm settling for memory.

I'm trying to be a man and let her be free.

But I still wish she would see me.

Joe’s voice had gone hoarse and halting. “Ahem. We don’t usually do that song because...y’know...no trumpet. Trumpet’s weird and loud and draws a crowd. It sets us apart from all the other street musicians...couldn’t ask Will or Ethan to sing that one anyway...” He cleared his throat again and chewed the insides of his cheeks, stifling a cry.

“I see you, Joey,” she said, her voice breaking with emotion as she choked back tears herself. “I see you...everywhere. All the time. I...I only see you. Can we...go somewhere? I mean unless...unless you guys all came together and now I’m just...messing everything up. Again.”

Joe looked to the other guys and nodded, some code about future plans the three of them understood without speaking. “You’re not messing anything up. Where you parked?”

“I actually...kinda need a ride,” she admitted after looking around to see she’d been deserted. She smiled. Being left behind...trapped...stuck...without a way out would normally spin up panic and anger, but she felt happy and safe at the moment. Fortunate. Blessed.

“Okaaaay. Good thing you ran into me,” he laughed. “We never come to ‘gigs’ together...that word is still cracking me up. No room in the cab of the truck for a drum and a keyboard plus both Will and Ethan. But there’s room for just a trumpet case and you.” They approached a hidden spot tucked into an alley where Joe’s old truck sat, unbothered by parking meters or garage attendants.

“You’re still driving this?”

“Uh...yeah. Guess you got a new...something...”

“Nope. Still driving the Civic, but I don’t think I’ve driven my car anywhere but the occasional trip to meet Mom somewhere, to someone else’s house for them to drive, or back to the old apartment in four years. It’s usually...not what my accompaniment wants to travel in. Plus my apartment’s so close to school now, I usually walk anyway and...”

“You’re...local again now? Back home...I mean...here?”

“Been here a little more than two years now. Doctoral program is here. Civic still runs so why get rid of it, right? I’m a little surprised you’re still in the truck.”

“It’s my main motivation to earn enough money to get a house with off street parking as soon as possible. I am never letting it go, even when it dies.”

“Strange attachment to an old beat up pick up truck.”

“It’s still got an original Rice Chex ass print on the roof. Why would I ever get ridda that?” He opened her passenger door and she stood for a moment, resurrecting that first kiss one more time. “The passenger door’s pretty fucking great too,” he added. She raised her eyes to him, pleading and permissive and he licked his lips. “Not now, yeah? Fucking...almost impossible not to, but...fuck.” He exhaled hard, creating a cloud of condensation that dissipated around them, seemingly as reluctant to leave as they were. “Where we going?”

“You know Gaslight Cafe?”

“The name of the fucking place is seriously Gaslight Cafe? That’s a real place?”

“Yeah. Like Mary Sue’s a real name.”

“Mary Sue is...not like that. Some dipshit who knew what they were doing chose to name their place THAT. On purpose. Fucking hipsters,” he breathed, and ran an exasperated hand over his face before starting the engine. “Where’s the goddam Gaslight Cafe?”

“Pleasant Ridge.”

“Of course it is. At least there’ll be a parking lot and I won’t have to scope out another free spot on the street.”

“You’re never getting rid of this truck?”

“Don’t plan on it.”

“Not even if my actual ass is in your life instead of an old and likely inaccurate impression of it in the roof?”

“That’s a bold and generous deal on the table.” He made a curious facial expression she couldn’t quite decipher.

“I thought so.”

“I’d definitely negotiate a deal like that.”

“You wouldn’t just take it?”

“I’d have to be sure it wasn’t just gonna disappear. The ass print might not be perfect but it’s permanent. Not giving that up unless I’m sure it’s for something I can count on.”

“Gotcha. What can I do to get you in this car today?” she joked, doing her best impression of a used car salesperson, but couldn’t fully shroud the sincerity of intention.

“I mean, it’s not gonna be a hard sell. You’re in the truck. We’re going to some dipshit place in the snotty burbs...”

“Because it’s open until two in the morning.”

“Penciled in a late night, did ya? With no ride?”

“I ditched my ride.”

“You really walked away from a ride home to drop a small bill in a tip hat for somebody who kinda reminded you of me?”

“Yep. How’s the car sale going?”

“Sold.” Joe stopped the truck and looked to her triumphant face. “This joint is full of the same cars I’m sure you rode out in tonight. I’m pretty outta place with Ol’ Cherry here. That why you wanna get rid of her?”

“I don’t really wanna get rid of her. Just wanted to let you know getting rid of her doesn’t get rid of me anymore.”

“I’m sure you’ve been out with guys who took you out in nicer rides to nicer places since...”

“You know those guys are all trying to capture what you really have, but they can’t do it because the introspection and reality sort of shorts their circuits. They don’t have the guts; just the shell. Like...a car isn’t a car if it doesn’t have an engine in it. You can dress up a rock inside a car chassis but that doesn’t make it a car. They wear the boots and grow the beard and some of them even drive a truck, but it’s shiny and spotless and just to perform some weird part in some unscripted play we all seem to know the lines to anyway. Some of them act like they’re a tough guy, not afraid to get their hands dirty and shit, but it’s really conditional. Like...I’ll get sweaty...at the gym. I’ll get dirty...if it’s in a mud run or a rugby game...”

“Jesus. You went out with a rugby player, didn’t ya? Was he a Brit?”

“Nope. American as shit. But you know...football is for thugs. Baseball and basketball aren’t tough enough. Hockey’s too seasonal. So rugby. It’s European and niche, but still tough; the perfect thing to do to look down on almost everybody.” They squeezed into a corner table barely big enough for two people. Joe ordered a black coffee and crossed his fingers under the table, hoping the server wouldn’t ask him to elaborate on it. He wasn’t one of those cranks who ridiculed someone else’s flavored nonfat latte or whatever, but he didn’t want to have a discussion with someone who tried to make him feel inferior about his simple tastes. “Same, but leave room at the top for about four ounces of milk and seven or eight sugars.” Joe raised one amused eyebrow at her as the server walked away. “Light and sweet.”

“You never drank coffee...before.”

“I still kinda think it’s gross unless you really doctor it up. But grad school sort of necessitates it.”

“Was it the rugby player you left tonight?”

“No. He was the first guy after...”

Joe smirked, satisfied with himself that she’d tried to find the closest approximation to his outsides she could. “Didn’t work out with him either, huh?”

“He was a rock.”

“Ha! In a pickup chassis?”

“More like a Mercedes S Class one. Dude wore Tommy Hilfiger everything. Socks! Socks, Joey. Tommy Hilfiger SOCKS.”

“That’s some serious...I dunno what, but it’s definitely something.”

“Posturing? Overcompensating? Conspicuous consumption? Flat out stupidity?”

“Yeah.” He sipped the coffee laid before him and watched her load hers with extras and furiously stir. “Hey. I really am...sorry...that you seem unhappy. I mean...now.”

“Oh you misread that, cupcake. I’m ecstatic NOW. I was unhappy...” she paused to look at her watch before concluding, “...about eighty minutes ago. And for the four years before that. Now though? Pretty happy.”

“I meant that...you like school, right?”

“I love school. I bury myself in school, kinda. When I’m reading and writing, it all goes away. The rest of it. The world everyone else our age that I’m ever around seems to live in. It’s so disillusioning to see how phony all of it is. My parents got sold on this shit and now they’re poisoning my brother with it too. He’s gonna get out there just like me after busting his ass at fucking math academy and see that none of it’s real. They’re all just playing dress up to be us and paying more for it, and no meaning gets absorbed while they’re doing it. I find myself living in the fiction a lot. That fiction is better than this weird pseudo-reality.”

“You give up on finding something better?”

“I’m never gonna stop on ‘better.’ But that shit’s not ‘better.’ I’m sorry I ever thought it was.” She wanted to reach across the table to touch him, but all she could muster the courage for was shifting her legs beneath the table to rest her dangling right foot from her apprehensively crossed legs on the top of his left boot toe. No skin contact; he probably couldn’t feel her there at all, but he didn’t pull away, and that comforted her. “What are you doing playing trumpet on the street?”

“I’m not only playing trumpet on the street. Like...I don’t need the twenty-ish bucks I made tonight to pay rent and shit. Not gonna lie; I’m using it to pay for this coffee, but...I’m still working at Gilford’s. With like...about everyone else.”

“I didn’t think you were only playing trumpet on the street, and I wouldn’t even care if you were. I always kinda thought you might...do something musical. For a living.”

“What? Like I’m gonna be first chair trumpet at the Cincinnati Symphony, or something even bigger than that, when I can’t read music. Ska is kind of dying if not dead now. I couldn’t make a living off that flash in the pan even if some band would have me. There’s only room for a few of them and they all already got trumpet players. Multiple trumpet players. I could probably pick out what to play, but they definitely want somebody who reads music and they probably want someone who does ‘proper fingering’ and whatever. Even in a ska band. Main and 9th is just the only place I really get to play my trumpet at all anymore. Fucking neighbors will call the property manager, and once the fucking police, for playing it at home in the apartment. Even with the mute. TRYING to be quiet. I gave up. Bought a guitar. Which Mom still gives me shit about as a waste of money. Because if you can’t eat it or wear it and it doesn’t make you money, it’s a waste of money, right?” He paused to roll his eyes. “Neighbors never say shit about the guitar. So far. But I’m never gonna totally give up playing the trumpet, so...Main and 9th every other Friday until I can buy a house with no neighbors sharing walls to call some authority on me for living. Picks us all up an extra twenty. Gives us something to do. We can’t all be hanging out in Jen’s mom’s basement anymore.”

“How is Jen? And...everybody else? Mom never says anything...”

“Why would she? Your mom never liked any of us when you were actually livin’ there,” he snickered.

“Thought she’d tell me about big shit at least.”

“Jen’s got a girlfriend. Penny. She gets like fake pissed at Chris Hines for referring to them as Jenny and Penny.”

“How’s Chris?”

“Haley and Chris had a baby last year.”

“What?!”

“I know.”

“I can’t believe Mom didn’t mention a wedding or a baby.”

“No wedding. They can’t afford to get married unless one or both of them gets a better job where they don’t have to game the system a little bit and/or her family takes their heads out of their asses.”

“Oh no.”

“Oh yeah. Her dad went after Chris and everything. All that shit about mixed race grandchildren ending racism in a person is super false.”

“That’s terrible. They’re ok, though, right?”

“Yeah, except Hayley never sees her folks. Which...that’s how you gotta be if your folks are gonna be like that, but...” He sighed heavily. “That guy you ditched tonight isn’t coming after me now, right?”

“He thinks you’re a homeless vagrant who somehow has an antique trumpet, so good luck to him if he tries, but no.”

“Did you think I was a homeless vagrant with an antique trumpet?”

“No. I was hoping you were you.”

“I’m not homeless. 400 square feet in not-the-best neighborhood and maybe three missed paychecks away, but not homeless.”

“Joey, I didn’t think you were homeless. You don’t look homeless. That was a comment on the shitheads I was out with, not one on you. I’m sure your apartment is...”

“I won’t ever take you to my apartment.”

“Never?”

“OK, maybe when I’m moving out. If you’re still around.”

“Permanent ass. I’m telling you. No way Steven comes after you. So many reasons. First, he’s a wimp and a prejudiced, entitled piece of shit, so he’s straight up afraid of you based on how you look and that you were playing music on the street. But also because he doesn’t care enough about me. Maybe not at all about me. You have to give at least a partial shit about a person to fight for them.”

“There’s no way I’d have been ok with you approaching three strange dudes without me on a night out, much less leave you alone with no ride home. Even if you had told me to fuck off. I could never leave you without a way home.”

“I know.” He raised the toes of his left foot to touch the bottom of her right foot. They both smiled, content in the solid knowledge that the other one was there.

“Tell me about your big deal...what do you call it?...at school.”

“You want to hear about the thesis?”

“Thesis! That’s the word. Yes, of course I want to hear about it. What’s it about? Doctor Rice Chex.”

“Not yet. Almost. It’s an analysis of Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.”

“Somehow I didn’t expect that to be the book you’d focus on.”

“Have you read it?”

“No. Read Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn in school because we had to. But I’ve seen some movies...”

“The movies are...not like the book. The book is radical commentary on monarchy and oligarchy and an indictment of their exploitation and mistreatment of the working class.” He raised his eyebrows with evident surprise. “Did I lose you already?”

“No, I’m...kinda riveted. Keep talking about it. How are you...like what is the summary? Of your work. I’ll read the whole thing if you’ll let me, but for over late night coffee...what’s Cliff’s Notes?” Mary Sue took a deep inhale, stemming tears of emotion. Joe was the only person other than her academic adviser to ask about her doctoral thesis; the thing she spent nearly all of her time and passion on for the past two and a half years. Her parents didn’t know what book she was writing about. None of her acquaintances at school and definitely not Steven or his friends ever asked after it.

“The narrator’s dilemma in the book is that he’s ahead of the royalty and aristocracy he’s thrown into, intellectually and with social enlightenment, but unable to get them to make progress because they seem incapable of self-examination and so focused on and steeped in their own privilege. They are sometimes impressed with his skills and knowledge, but they’re all still fixated on how they outrank him. They’re nobility; royalty; and he’s Just a Guy, even if he’s the smartest, kindest, whatever-est guy around. He’s still Just a Guy. He so clearly doesn’t fit into that world, but after a time, he realized he would no longer fit inside the world he came from either. The world he came from romanticizes and lauds the past, nobility and royalty, all of that as some foregone time and people of high ideals, like they’re better; some goal to aim for in the common present. People he knew before would be envious and resentful and intrigued that he had been there and been a part of things there for a patch of time, but he knows from real experience that it wasn’t better at all. It was worse in a lot of ways. The new world changed him and he couldn’t put a noticeable dent in it. He couldn’t really get the king and knights and nobles to understand where he’d come from, and he could never convince the people he’d known before how wrong things were with that royal world. So he just doesn’t really have anyone to connect to at all. And I’m sort of comparing that to the struggle of a working class kid going to college. That kid has no frame of reference with his new peers, but when he returns home, he’s lost his frame of reference with his former peer group simply because he’d been around the new one.” She took a rickety, choppy deep breath and raked her teeth across her bottom lip, unable to hold eye contact with Joe anymore. She was back to staring at the center of the table, but it was a much smaller table, and it didn’t have the distance she needed to adequately isolate herself.

“That sounds really personal.” He clumsily stretched out under the restricting tiny table to cross his feet at the ankles around Mary Sue’s bouncing left leg; the only one still planted on the ground. She uncrossed her legs and slid her right foot down to nestle between his shins too. The grazing touch and warm closeness relaxed her.

“It is. I’ve felt stuck between two worlds where I don’t fit into either one of them too. I don’t belong here at this coffee bar. I feel just as out of place as you do. But I feel like I can’t go home again, either.”

“Home hasn’t felt right to me since you left. I’m still me and all that, and I still don’t think I’d cut it in college. But I figured out in like ninth grade that I can really only be happy with a smart girl who uses big words when she talks, and you are hard pressed to find someone like that driving a forklift at Gilford’s.”

“I was looking for a guy in university life who wasn’t afraid to get dirty or get into a little trouble, but I’ve found once you step so far outside the working class, that just means a guy’s mean.”

“Was the guy you left tonight mean?”

“Yeah. Dumped his ass because he didn’t want me to give you the money.”

“That’s my girl,” Joe claimed, wearing a wide, prideful smile.

“That is your girl, Joey,” Mary Sue affirmed.

“I dunno. He’s clearly been taking you out to some pretty nice places.”

“’Nice places.’ First of all, we go to these done up ‘gastro-pubs’ or whatever, and I don’t drink, and we end up paying for bland knock-off food...like fried mozzarella sticks I know came out of a bag in the freezer at the ‘Italian’ place tonight. Made me think of you as soon as we walked in the door.”

“Because I’m a bland, knock-off Italian?” he laughed.

“Because of what the word means. Dispetto is Italian for mischief.”

“My name’s Disibio, but you know I don’t speak Italian. Shit do you speak Italian now?”

“No, I can only limp through ‘where is the bathroom’ and shit in Spanish and French. Barely.”

“Hell, even I can do ‘donde esta el bano?’” he chuckled. “How do you know what the name of the bar means then? I thought it was a last name.”

“It might be a last name, but the meaning’s printed on the fucking napkins if you miss it on the door.” She rolled her eyes and shook her head. “And so we’re at these places paying too much for overplayed pedestrian crap and then he doesn’t tip. I’ve compensated for a three percent tip probably fifty times this past year. It’s why I always carry cash.”

“What a piece of shit!”

“Right? Leaves trash on the table and shit even when we’re at a ‘non-tip’ place and says, ‘That’s someone’s job,’ if I start picking up after us. These rich people are cheap as shit. I went out with his family once...to McDonald’s...and his dad seriously got into an argument with his mom that she didn’t need her own fries.”

“Christ, how did you stay with that guy?”

“I dunno. No one else in my vicinity could cut through the bullshit because they’re all basically full of the same bullshit. La Vie En Rose broke the spell. Why would you play that song every time you play? Surely you weren’t hoping for this freakishly unlikely and specific happenstance.”

“I wasn’t. At all. I thought that was beyond all hope. I thought you were still a couple hours or farther away. Maybe you’d totally forgotten me by now. But you kept a piece of me somewhere that’s attached to that song on the trumpet. And grad school’s here. Lucky me.” She blushed and looked down at her fingers squeezing the coffee cup, and he flooded with gratification. “It’s my favorite song to play on the horn. It’s you. Life in pink. Looking at the weary world with rose colored glasses on. I miss looking at the world like that. I only manage to do it with you.”

Servers began maneuvering through tables, casually informing customers how close it was to closing time. “Shit, are we getting kicked outta here?” she mourned.

“Looks that way. We still have the drive home.”

“We have more than that, I hope. Right? This wasn’t ‘bum a ride home; catch up a little’ to me. Is that...is that what you thought it was? W-what you wanted it to be?”

“No. I don’t know what I wanted it to be, but I know it wasn’t ‘check she’s ok; drop her off; end.’ Who’d read that story?” he kidded. “W-what did you want it to be?”

“I wanted...I want… Are…will you still be My Joe?”

“Yeah. I’ve never not been Your Joe, Rice Chex.” He pulled his solid block of a cell phone out of his pocket. “Just got this fuckin’ thing. I wasn’t gonna get one, but Mom and John got some plan where they had another phone and...”

“I get it. I’m on the ‘extra phone; just give us twenty bucks a month’ plan too.”

“I’ve only figured out how to make phone calls so far. Which I rarely do, because I’m afraid to cost my folks money and I don’t understand the fucking rate structure.”

“I don’t think anybody does.”

“Mostly it’s for Mom or Nanna D to feel better, calling to check on me when I’m out playing to make sure nothing bad happened to me. Nobody got me. You know. Too bad they didn’t call to check tonight. ‘Cause...you got me. I coulda told ‘em somebody got me,” he joked. She sighed, and took out her own phone to exchange new numbers. He saw she was becoming emotional, so he clarified himself without the humor, because it didn’t make her laugh the way he wanted it to. “I like that I can hold new phone numbers in this though. ‘Cause I’m gonna call you. Sober. I’m gonna call you sober. I...I haven’t had a drink at all in two years. That...that was the first and last time I got drunk.” They walked out to his truck in sticky, electric reticence. He once again stopped at the passenger door, and opened it, and she didn’t get in, again. “You’re not talking anymore. I kinda need ya to say something now. Things feel...I dunno. My head’s buzzing like I’ve been drinking and I haven’t been, and I just told you big scary truth about drinking, and it’s making me really nervous...”

“I’m...I’m so glad I found...so glad...this happened today,” she stammered out in restless, breathy exhales.

“Me too. So it’s not over. Even after saying...even after I drive you home. Right?”

“Not over. Will probably be really hard not to invite you in to stay.”

“We shouldn’t. Tonight.”

“I know. And we won’t. But I want to.”

“Wanna get to know your new world changes a little. I’m in the same old world, but I’ve changed a little too.”

“I’m nervous about that.”

“Why? Old us didn’t work. New us might. Maybe we made all the right changes.”

“’Everyday words seem to turn into love songs...’”

“What are we doing here?” he asked, echoing her words lost in time, and tentatively reached out to interlock their hands the same way he had the first time he’d kissed her.

“I really hope you’re gonna kiss me now.” He leaned in, completing the replay, and a rush of rightness flooded through her body. She’d kissed other guys before and since Joe, but none of those kisses ever made her feel like she was flying but also totally safe the way his did. “Now I need you to say something,” she whispered after a few moments of renewed soundless electricity.

“’Give your heart and soul to me, and life will always be ‘La Vie En Rose,’” he softly sang into her ear.

“Done,” she said. “Yours.”

“My Rice Chex.” He rubbed her chin with his thumb and brushed the tip of his nose against the tip of hers. “Take ya home now?” She nodded, her eyes still closed, seeing nothing but pink, and folded herself from muscle memory into the familiar passenger seat.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ain't Misbehavin' (1929 Jazz Standard)

Ain't Misbehavin' (1929 Jazz Standard)Best Sheet Music download from our Library.Please, subscribe to our Library. Thank you!Recommended versionsVersions in the top chartsJazz oustanding performancesLaden Sie die besten Noten aus unserer Bibliothek herunter.Browse in the Library:

Ain't Misbehavin' (1929 Jazz Standard)

"Ain't Misbehavin'" is a 1929 stride jazz/early swing song. Andy Razaf wrote the lyrics to a score by Thomas "Fats" Waller and Harry Brooks for the Broadway musical comedy play Connie's Hot Chocolates. As a work from 1929 with its copyright renewed, it will enter the American public domain on January 1, 2025.

Although Ain't Misbehavin is a standard composed by Fats Waller and Harry Brooks, it was Louis Armstrong who turned it into a universal classic with the premiere of "Keep Shufflin'", a musical composed by Fat Waller himself and which would end up establishing Armstrong and his “Hot Five” / “Hot Seven” as one of the most important artists of his time.

The song was first performed at the premiere of Connie's Hot Chocolates in Harlem at Connie's Inn as an opening song by Paul Bass and Margaret Simms, and repeated later in the musical by Russell Wooding's Hallelujah Singers. Connie's Hot Chocolates was transferred to the Hudson Theatre on Broadway during June 1929, where it was renamed to Hot Chocolates and where Louis Armstrong became the orchestra director. The script also required Armstrong to play "Ain't Misbehavin'" in a trumpet solo, and although this was initially slated only to be a reprise of the opening song, Armstrong's performance was so well received that the trumpeter was asked to climb out of the orchestra pit and play the piece on stage.

As noted by Thomas Brothers in his book Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism, Armstrong was first taught "Ain't Misbehavin'" by Waller himself, "wood shedding" it until he could "play all around it"; he cherished it "because it was 'one of those songs you could cut loose and swing with.'"

After the good reviews received at the premiere of the musical (in which curiously he did not even appear on stage, but instead played in the pit intended for the musicians), Armstrong decided to take the song to the studio a year later, introducing by course his own personal imprint.

The success was dazzling, but curiously, although more than 20 different versions of the same song were recorded, a year later it had fallen into oblivion. It was not until the mid-1930s when the song was recovered again, through Duke Ellington, in a curious revival that was joined by versions by Jack Teagarden, Django Reinhardt, Paul Whiteman and Jelly Roll Morton, who performed it in the Library of Congress.

But although the song survived the swing and Big Band era, the composition was too classic to sound “new” once the Second World War ended, so even though Dizzy Gillespie recorded his own version in 1952, it did not become a success again until 1978, when Hank Jones premiered on Broadway a Tony-winning musical based on the golden age of jazz and titled “Ain't Misbehavin.”

Today the song is not part of the majority of modern jazz repertoires, but nevertheless, it remains a composition that must be studied in schools, especially for those interested in mastering the Harlem stride style in which Art Tatum was a master and his version of this song, a true marvel.

Recommended versions

- Louis Armstrong (July 1929)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljuo5fkW-fs

- Fats Waller (1929)

- Duke Ellington (1933)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nkIGvl9hlGA

- Paul Whiteman (1935)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8oOt4waqNdE

- Django Reinhardt (1937)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JGmAkFWD3PA

- Jelly Roll Morton (1938)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KmiII03it-E

- Art Tatum (1944)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vzceNyfM6mg

- Sarah Vaughan-Miles Davis (1950)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhVhYGEuB4Y

- Johnny Harman (1955)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S7uZipRrmPo

- Hank Jones (1978)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=du1UY7fwGjw

- Dick Wellstood (1985)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dGEzTBI3Cqg

Versions in the top charts

Performers

Recording Date

Entr. DateWeeks inReached position Louis Armstrong Orchestra1929.06.191929.09.2847Louis Armstrong (voc)Leo Reisman Orchestra1929.07.091929.08.3172 (one week)Lew Conrad (voc)Gene Austin1929.07.301929.09.2839Gene Austin (voc), Fats Waller (p)Fats Waller1929.08.021929.11.09117InstrumentalRuth Etting1929.08.201929.10.19116Ruth Etting (voc)Irving Mills Hotsy Topsy Gang1929.09.041929.10.2638Bill 'Bojangles' Robinson (voc, tap)Teddy Wilson Quartet1937.08.291937.10.2336InstrumentalDinah Washington1947.11.131948.03.2016Dinah Washington (voc), Rudy Martin Trio

Rhythm & Blues charts

Jazz oustanding performances

Instrumental

PerformersRecording date

Assembled Personnel

Fats Waller1929.08.02Fats Waller (p)Teddy Weatherford1937.07.20Teddy Weatherford (p)Teddy Wilson Quartet1937.08.29Harry James (tp), Teddy Wilson (p), Red Norvo (xil), John Simmons (b)Bobby Hackett Orchestra1939.04.13Bobby Hackett (cnt), Sterling Bose, Jack Thompson (tp), Brad Gowans (vtb), George Troup (tb), Pee Wee Russell (cl), Louis Colombo (as), Bernie Billings (ts), Sid Jacob (bars), Dave Bowman (p), Eddie Condon (g), Ernie Caceres (b), Don Carter (d)Art Tatum1953.12.29Art Tatum (p)Ray Brown1960.08.31Ray Brown (vc), Don Fagerquist (tp), Harry Betts (tb), John Cave (tpa), Med Flory (as), Bob Cooper (ts), Bill Hood (bars), Paul Horn (fl), Jimmy Rowles (p), Joe Mondragon (b), Dick Shanahan (d), Russ Garcia (dir)Ralph Sutton Trio1969.02.11Ralph Sutton (p), Al Hall (b), Cliff Leeman (d)Count Basie Orchestra1969.10.20Count Basie (p, dir), Oscar Blashear, Waymon Reed, Gene Goe, Sonny Cohn (tp), Grover Mitchell, Mel Wanzo, Bill Hughes (tb), Marshall Royal, Bobby Plater (as), Eric Dixon (ts, fl), Eddie 'Lockjaw' Davis (ts), Charlie Fowlkes (bars), Freddie Green (g), Norman Keenan (b), Harold Jones (d)Howard Alden & George Van Eps1991.??.??Howard Alden (g), George Van Eps (g)Joe Pass1993.02.04Joe Pass (g), Tom Ranier (p), John Pisano (g), Jim Hughart (b), Colin Bailey (d)McCoy Tyner2000.06.14McCoy Tyner (p)Keith Jarrett Trio2001.07.22Keith Jarrett (p), Gary Peacock (b), Jack DeJohnette (d)

Vocal

PerformersRecording date

Assembled PersonnelLouis Armstrong Orchestra1929.07.19Louis Armstrong (tp, voc), Homer Hobson (tp), Fred Robinson (tb), Jimmy Strong (cl, ts), Bert Curry, Crawford Wethington (as), Carroll Dickerson (vn), Gene Anderson (p, cel), Mancy Carr (bjo), Pete Briggs (tu), Zutty Singleton (d)Irving Mills Hotsy Totsy Gang1929.09.13Arthur Whetsel, Cootie Williams (tp), Joe Nanton (tb), Barney Bigard (cl, ts), Johnny Hodges (as, ss, cl), Duke Ellington (p), Fred Guy (bjo), Wellman Braud (b), Sonny Greer (d), Bill 'Bojangles' Robinson (voc, tap)Fats Waller & His Rhythm1943.01.23Fats Waller (p, voc), Benny Carter (tp), Alton Moore (tb), Gene Porter (cl, as), Irving Ashby (g), Slam Stewart (b), Zutty Singleton (d)Louis Armstrong All Stars1947.05.17Louis Armstrong (tp, voc), Bobby Hackett (cnt), Jack Teagarden (tb), Peanuts Hucko (cl), Dick Cary (p), Bob Haggart (b), Sid Catlett (d) In Town Hall (New York)

Dinah Washington1947.11.13Dinah Washington (voc), Rudy Martin TrioSarah Vaughan1950.05.18Sarah Vaughan (voc), George Treadwell (dir), Miles Davis (tp), Bennie Green (tb), Budd Johnson (ts), Tony Scott (cl), Jimmy Jones (p), Freddie Green (g), Billy Taylor Jr. (b), J.C. Heard (d)Billie Holiday1955.02.14Billie Holiday (voc), Tony Scott (cl, dir), Charlie Shavers (tp), Budd Johnson (ts), Billy Taylor (p), Billy Bauer (g), Leonard Gaskin (b), Cozy Cole (d)Maxine Sullivan All Stars1956.08.30Maxine Sullivan (voc), Charlie Shavers (tp), Jerome Richardson (as), Buster Bailey (cl), Dick Hyman (p), Milt Hinton or Wendell Marshall (b), Osie Johnson (d)Joe Williams1958.10.16Joe Williams (voc), Count Basie (p, org), Freddie Green (g), George Duvivier (b)Dave Brubeck Quartet1960.08.04Paul Desmond (as), Dave Brubeck (p), Gene Wright (b), Joe Morello (d), Jimmy Rushing (voc)Tony Bennett1964.03.26Tony Bennett (voc), Ralph Sharon (p, dir), Hal Gaylord (b), William Exiner (d)Wllie 'The Lion' Smith1966.11.08Willie 'The Lion' Smith (p, voc)

Read the full article

#SMLPDF#noten#partitura#sheetmusicdownload#sheetmusicscoredownloadpartiturapartitionspartitinoten楽譜망할음악ноты

0 notes

Text

Today In History

Ella Fitzgerald, dubbed “The First Lady of Song,” was born in Newport News, VA, on this date April 25, 1918.

Fitzgerald was the most popular female jazz singer in the United States for more than half a century. In her lifetime, she won 13 Grammy awards and sold over 40 million albums.

Ella Fitzgerald voice was flexible, wide-ranging, accurate and ageless. She could sing sultry ballads, sweet jazz and imitate every instrument in an orchestra. She worked with all the jazz greats, from Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Nat King Cole, to Frank Sinatra, Dizzy Gillespie and Benny Goodman. (Or rather, some might say all the jazz greats had the pleasure of working with Ella.)

CARTER™️ Magazine

#ella fitzgerald#carter magazine#carter#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#history#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

1971 - Newport Jazz Festival - Belgrade

Duke Ellington Orchestra

Miles Davis Quintet

Giants of Jazz with Dizzy Gillespie

Ornette Coleman Quartet

Preservation Hall Band

Gary Burton

#jazz#poster flyer#jazz festival#duke ellington#miles davis#giants of jazz#dizzy gillespie#ornette coleman#preservation hall band#gary burton#1971#belgrade jazz festival

37 notes

·

View notes