#Duroc-Jersey

Text

Little Village Farm, a South Dakota treasure

Keith and I recently took our first trip to South Dakota. We stopped at Jim and Joan Lacy’s Little Village Farm. Located three miles east of Trent, they are open April – October by chance or appointment. When we pulled up, Jim came rolling up in a cool REO Oldsmobile old style car replica! Before we left for the day, I got a chance to drive this miraculous machine. What fun!

On the grounds of…

#1/8th scale farm toys#1530 McCormick Deering#16 sided barn#architectural ceiling#Baker Windmill#brooder house#butter churns#caps#Case Eagle on the World#Case tractors#chicken house#chickens#chicks#collecting#cream separators#Dell Rapids#Diamond T pickup#dinner bell#Duroc-Jersey bred sows#egg money#egg scale#eggs#fanning mills#farm hats#farm toys#farrowing#five sow brooder#fruit jars#German social club#grain proble

0 notes

Text

El desarrollo del cerdo ibérico se ha caracterizado por su explotación mediante sistema extensivo, donde la alimentación ha dependido básica y casi únicamente del aprovechamiento racional de los recursos naturales existentes en su área de producción, distinguiéndose su ciclo productivo por una larga duración de sus fases componentes. Esto se mantuvo a pesar de su baja rentabilidad, gracias al buen hacer de ganaderos e industriales en base a la consecución de productos elaborados de altísima calidad.

Debido al auge en la producción de piezas nobles de cerdos ibéricos y con el objeto de alcanzar mejoras en distintos parámetros productivos, se introdujeron variaciones en la raza, en el acortamiento de su ciclo productivo y en el tipo de alimentación fundamentalmente en su fase de cebo.

En cuanto a las variaciones en la genética, conociendo la importancia de las diferencias entre subvariedades ibéricas y sus posibles combinaciones, se ha cruzado con otras razas diferentes a las encuadradas dentro de su tronco. El cruce más significativo ha sido el Duroc-Jersey. Éste ha aportado ventajas importantes al tronco ibérico: mayor prolificidad, mejor índice de transformación, mayor rendimiento a la canal y mejora en los pesos de los jamones, observándose a su vez, aunque no demostrado analíticamente, en este cruce un menor grado de infiltración grasa.

El ciclo productivo se ha caracterizado por su larga duración y por ser extensivo durante gran parte del año íntimamente relacionado con la estacionalidad de los frutos de la dehesa. Esto determinó 3 características fundamentales: una elevada edad de sacrificio (entorno a los 18 meses), lo que conllevaba también un peso muy alto (aproximadamente 180kg.) y la realización de ejercicio especifico durante las fases en extensivo para buscar alimento. Sin embargo, a lo largo del tiempo se ha ido introduciendo variaciones condicionadas en la mayoría de los casos por ambiciones económicas y no de calidad. El acortamiento del ciclo es evidente en la mayoría de los animales sacrificados (a veces con edades inferiores a 10 meses en intensivo). Se presentan por esto diferencias en la recría, para alcanzar el peso de entrada en montanera con mayor prontitud. También en las características de la alimentación de la fase de pre-cebo, y en el cebo donde no siempre la alimentación es exclusiva de la cosecha de la montanera por el hecho de ser un periodo corto y dificultar el racionamiento ya sea debido a la limitación en la producción de bellota y herbácea (deficiencia proteica) o a la llegada tardía de cerdos a la montanera.

En el tipo de alimentación en la fase de cebo se han realizado, a su vez, importantes variaciones. De esta problemática surgió el control por medio de cromatografía gaseosa del perfil de ácidos grasos del tejido adiposo. La actualidad nos lleva al empleo de piensos en los que se aumenta la insaturación con ácido oleico, con subproductos de la industria del aceite o con determinadas semillas oleaginosas. Pero no es solo la calidad de la grasa el diferenciador de los 3 tipos de alimentación en la fase de cebo de los cerdos ibéricos (bellota, cebo campo y cebo), sino que también debemos tener muy en cuenta que la provisión de alimentos en extensivo en la montanera proporciona los antioxidantes reguladores de las reacciones que ocurren en los productos elaborados, establece la fracción insaponificable de la grasa y exige un pastoreo del cerdo, dando las características del ejercicio obligado.

Establecieron, en un 1º estudio, la simple comparación de 2 tipos de ciclos con diferente genética observando su influencia sobre la infiltración del lomo de cerdo ibérico. Dicho estudio se englobó dentro de un trabajo más ambicioso y más pormenorizado dentro de una posible tipificación del lomo ibérico de bellota.

Materiales y métodos

En los últimos 3 años estuvieron controlando y analizando lomos de cerdos ibéricos para calcular su infiltración. Con un volumen de muestras de 400 partidas pudieron establecer un control de más de 2.

500 animales. Dichas partidas se englobaron en 2 tipos de ciclo productivos:

Ciclo productivo A: Cruce de ibérico x duroc 25%, con una duración cercana a los 18 meses con fase de cebo en régimen extensivo en montanera con una reposición cercana a las 7 arrobas y un peso final entorno a los 180kg.

Ciclo productivo B: Cruce de ibérico x duroc 50%, con una duración de 12 meses con fase de cebo en régimen semi extensivo a base de pienso,

con una reposición de 6 arrobas y un peso final entorno a los 165kg.

El parámetro analizado de porcentaje de grasa infiltrada sobre extracto seco ha sido determinado mediante la tecnología NIR/NIT. Su modo de trabajo es transmitancia (NIT). El intervalo de longitudes de onda utilizado es de 800-1100nm. 2 de las calibraciones incluidas en el sistema se aplicaron para la obtención de dicho parámetros.

Resultados y discusión

Se observó en la distribución de los resultados una mayor infiltración, como era de prever en los cerdos del ciclo productivo A con mayor porcentaje de ibérico, con edad de sacrifico más avanzada, mayor ejercicio y alimentación en dehesa.

La diferencia entre los datos más frecuentes de porcentaje de infiltración sobre extracto seco (de 44 a 46% en del ciclo A, y de 30 a 32% en el ciclo B) es bastante apreciable, aunque existió una zona de intersección entre ambos conjuntos de partidas.

Otra de los circunstancias que se apreció fue una mayor dispersión en el ciclo productivo B, encontrándose una superior heterogeneidad en el grado de infiltración.

A partir de estos resultados y de la bibliografía existente pudieron establecer los siguientes puntos de discusión:

En la infiltración se puede sostener que a idéntico manejo y alimentación, es la genética la que determina las característica globales por el carácter adipogénico del propio cerdo ibérico.

• El incremento en peso en animales de edades adultas es casi exclusivamente a base de grasa lo que parece conllevar un mayor grado de infiltración según el peso y edad de sacrificio.

La realización de ciclos productivos largos consigue una mayor homogeneidad en el grado de infiltración entre partidas, y por lo tanto en los productos generados a partir de ellas.

La práctica de un mayor pastoreo y la realización de más ejercicio diario parece conllevar un mayor porcentaje de grasa en el músculo.

Autores

A. Josemaria Bastida, M.D. García Cachán. Estación Tecnológica de la Carne de Guijuelo.

0 notes

Text

Biography of Perry Peck

Biography of Perry Peck

Perry Peck is the owner of one of the fine farms of Licking county, having one hundred acres of valuable land in Harrison township about three miles from Pataskala. Upon his place he has all modern equipment known to the model farm of the twentieth century and here he is extensively engaged in stock-raising, making a specialty of American Merino sheep, Jersey cows and Duroc Jersey Red hogs. His…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

New hops collection alert! Wigrich Ranche Photographic Album, circa 1915.

Yay for new collections!

At some point during the 30 years we've been in a pandemic we got this delightful photograph album of the Wigrich Ranche (sic), a hops farm located in Buena Vista, Oregon. It's approximately 3 miles southeast of Independence in an area that was called the “Hop Center of the World” between 1900 and 1940.

Originally known as the Krebs Ranch, the largest hop farm in the state, it was purchased by English hops merchants Wigans and Richardson in 1911, who called the farm Wigrich Ranche, a combination of Wigan and Richardson. In the 1920s, the Wigrich Ranche was said to be the largest hop yard under a single trellis in the world. In 1941, they sold the farm to the Steiner Company, headquartered in New York, and it was renamed the Golden Gate Hop Ranch. It was sold again in 1949 to Herman and Myrtle Moritz and then to Robert Fitts in 1952, who stopped raising hops.

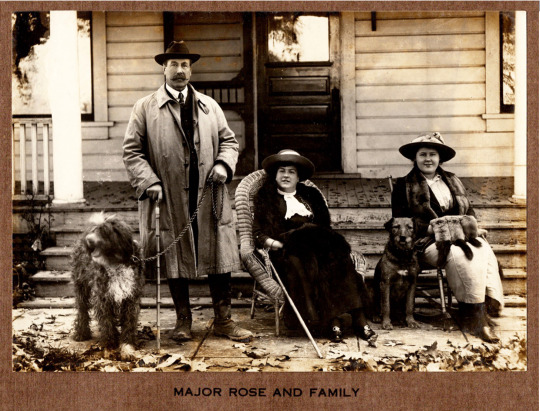

Major W. Lewis Rose, formerly of the British Army, began his work as farm manager in 1913. He was formerly an estate manager in Ireland and in the army with Richardson. He managed the farm until 1928, when he resigned due to ill health; he died in Victoria, B.C. in 1930.

The photo above shows Rose with his wife Charlotte and daughter Winifred in front of their house.

The bulk of the album shows operations and worker activities.

Also included are photographs of large drying kilns, storage sheds, and other equipment; the office of the yard boss; the bakery, restaurant, grocery store, market, dance hall, and blacksmith shop.

There are photos of a newly-planted orchard; plants damaged by a wind storm; bales of hops en route to warehouse storage and being loaded on a train at the Wigrich railroad stop; livestock used on the ranch (Jersey and Durham cows, and Poland Chinese and Duroc Jersey boars).

Interior shots include a furnace room with a drying kiln; a tram car loaded with hops entering a kiln; men examining the hops harvest; hops stored in a warehouse, and men preparing bread in the bakery to feed the pickers. There are many photographs of workers, including group-portraits of laborers harvesting hops or transporting them to the warehouse; men in a baling pit; a view of a tent camp and grounds; workers waiting for mail delivery at the post office in the grocery store; dressed-up workers at the dance hall; and workers leaving the ranch after harvest to return home via train or automobile.

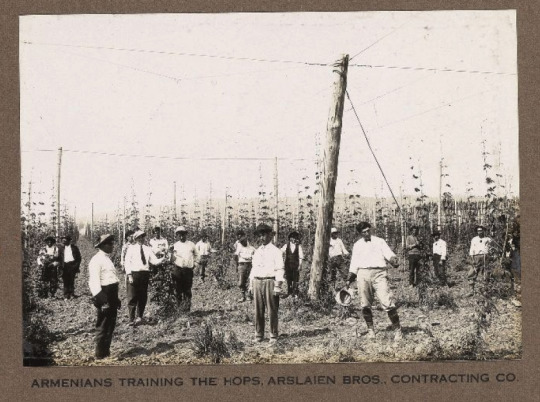

One image shows a group of Armenian laborers of the Arslanien Brothers Contracting Co. training newly-established bines (hop vines) in a field.

A series of photos entitled “Twelve Views of the Pickers,” shows seasonal workers divided into twelve groups, many wearing large hats, holding hops plants, pets, bales, etc. Some men are perched on wire fencing. The presence of women and children indicates many seasonal workers brought their families along.

The album is 8” x 12”, with black leather covers and 51 4.75” x 6.75” silver prints mounted on 32 brown leaves. There are 62 photographs. This genre of albums were created to document the operations of businesses; in some cases as a visual record and memento for management, for promotional purposes, or distributed to potential or existing customers. The photographs were taken by the Parker Studio, Salem, Oregon.

Several of these photographs were used in Kenneth Helphand's book Hops: Historic Photographs of the Oregon Hopscape (OSU Press, 2020). It's a lovely "visual dive into the physical presence of the plant and its distinctive landscape and culture."

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jamón Iberico Ich liebe diese Sonntags Tapa dazu ein Glas Rotwein, mehr brauche ich nicht. einfach delicioso Jamón Iberico korrekter Ibérico-Schinken, denn es handelt sich hier nicht um eine Herkunftsbezeichnung wie z. B. dänischer Schinken, sondern um eine Rasse) wird aus dem Iberico Schwein hergestellt (oder aus Kreuzungen mit max. 25] % der Rasse Duroc-Jersey. Das iberische Schwein unterscheidet sich äußerlich vom normalen Hausschwein durch die meist dunklere Hautfarbe. Es wird deshalb auch als schwarzes Schwein bezeichnet. Der vom gewöhnlichen Hausschwein in Spanien gewonnene luftgetrocknete Schinken wird Jamón serrano oder Serrano Schinken genannt. Weil iberische Schweine oft eine schwarze Klaue haben, nannte man den Schinken auch Jamón de pata negra („Schwarzklauenschinken“). Die Produktion schließt sehr viele Qualitätskontrollen ein, beginnend mit der Aufzucht des Schweins bis zur endgültigen Verarbeitung des Rohproduktes, um höchste Qualität zu garantieren. #tapas #tapa #delicioso #delicous #leckerschmecker😋 #yummy😋😋 #yummyfood😋 #jamon #jamoniberico #gesundessen #gesundeernährung (hier: Frankfurt, Germany) https://www.instagram.com/p/CDYs4WyglQW/?igshid=1w6g1q7w4yxub

#tapas#tapa#delicioso#delicous#leckerschmecker😋#yummy😋😋#yummyfood😋#jamon#jamoniberico#gesundessen#gesundeernährung

0 notes

Text

Wrack and Ruin: Final

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Part V

Part VI

What an end to a day. Arthur is frustrated. Feeling bad for a monster! Indeed. How typically French. How typically Bonaparte. How typical it is for one from that family to go and throw the entire plan off. This is how society falls, he thinks, when we start feeling poorly for monsters like the Jersey Devil. As if it inhabits any humanity within it to warrant pity or kindness.

What a miserable end to his letter to Liverpool. Well, perhaps not miserable. Bonaparte, that is Napoleon, assured him that the creature posed no military threat or otherwise to England or her colonies. What would happen were it to go to Upper and Lower Canada? Nothing, Bonaparte had said. Eat some cattle? Scare a few farmers?

He will admit he was not sure what he had expected from the entire expedition which hadn't been his idea to begin with. There was no great confrontation as there had been in Woodford and for that he is thankful. He isn't sure he is up for more confrontations with mystical beings of supernatural power. Age does catch up with one.

He concludes his letter to Liverpool and adds it to the stack that is to be sent on ahead of them before they embark on their journey homeward.

'No dinners with a president,' Napoleon says, letting himself in. 'Are you offended or relieved?'

'Relieved, I assure you. And I had dinner with the director of the Federal Bank and the former, if temporary, King of Spain. I think I can forego dinner with Monroe for that.'

'And you dine regularly with the former emperor of France, how your other dinner guests must pale in comparison.'

'That is a title we do not recognize,' Arthur replies in a stiff manner.

'But Joseph is King of Spain! That is unkind. Not to mention a work of great mental elasticity. Who made him king of Spain I wonder.' But Napoleon is smiling as he says it so Arthur does not take umbrage.

They end up topsy-turvy on the bed with Napoleon's stockinged feet on the pillows and head by the foot of the bed with Arthur the opposite. It is a quiet evening, no formal dinner. At some point soon they will go downstairs and be social. Both are still in their hunting clothes, buckskin breeches and wool coats deposited on chair backs.

'I still cannot believe neither of you shot it,' Arthur says. He can feel circles being traced along his hip.

'It was no wolf, bear or boar. There would have been no honour in it. You would agree with me had you seen it.'

Arthur props himself up and looks down to Napoleon who has his eyes closed. One arm is beneath his head as a pillow, the other against Arthur's leg drawing those absent shapes.

'It's the Jersey Devil,' Arthur says.

'It was sad.'

'Sad? You don't look at a deer and think, oh it's sad so I shan't shoot it today.'

'No, no.' Napoleon's face screws up in thought then regains composure. He unwinds his hand that was a pillow and rubs his eyes. 'It's different. I felt pity for it. Not the pity you feel for a wounded horse or hound, where it is a mercy to shoot them. But the pity you feel for a man who dies alone with no one to hold his hand. Or the pity you feel when someone is dead and there is no one to mourn for them. The pity associated with extreme isolation.'

'That is all very well but it is hardly human.'

Napoleon thinks on this then sits up and frowns at Arthur. He holds out his hand and balances it side to side, 'yes and no. When I met its gaze I felt there was something humane about it. It's eyes, though red and yellow, were still human eyes.'

'You mean they expressed human emotion.'

'No, I mean they literally were the eyes of mankind. The eyes of Adam.' He rubs his face again. 'It's hard to explain. I hold no grievance with Joseph for not shooting it. I didn't run it through either. We just sort of exchanged eye contact with it then it went on its way. The only of its kind Joseph thinks. How sad. Alone, exiled from its family all those years ago.'

Arthur, 'there is no similarity there. Your family still cares. Well, some of your family cares.'

Napoleon laughs. Says that Arthur really knows how to make a man feel loved. Excellent ability to improve a person's mood. ‘God,’ he sighs as he lies back down, ‘what would I do without you to remind me that some of my family cares?’

'I wager you would get on well enough.'

'I'd be a puddle of despair.'

Arthur rolls his eyes, mutters that Napoleon is not being serious anymore. Always skirting away from difficult truths. At that Napoleon sits back up and with a grave expression says, 'I'm sorry.'

'For what? I was just grumping. It's my way.'

'Now who isn't being serious?'

'Fine, fine I accept your strange and unnecessary apology.'

Napoleon smiles and pats Arthur's cheek. 'I am glad.' Bringing up Arthur's hand he brushes a kiss along the knuckles then says he must go and bathe and change if he is to be in anything resembling a presentable state for dinner.

//

It is later, after food and drinks and several rounds of cards and Arthur has retired for the evening that Napoleon finds Joseph in his library with a thick blanket on his lap and reading Defoe. Joseph looks at him from overtop his glasses.

'You appear comfortable,' Napoleon says. He lingers at the edge of the room. Outside the light of the fire and the lamps and candles. Joseph motions him to the chair near him.

'I hate this book but I'm too committed to stop now. Besides, I promised Cadwalader that I would give him my assessment of it and I would like it to be more thorough than 'absolute rubbish, feed it to the pigs with turnip tops'.'

'What a country gentlemen you have become.'

Joseph smiles, says that the same could be said for Napoleon. He heard of the garden from Wellesley who was really just complaining about the bees. Bees, how fitting. He has thought about bees as well.

Napoleon, 'what I said today. I didn't mean it.'

'Yes you did.'

'No,' he sighs. 'No, I didn't. I was angry more at myself than you. I'm never angry at you.'

'What a lie.' But Joseph laughs a bit as he says it.

'I am trying to apologize brother. Very well, I have been angry you in the past. I am capable of being angry and frustrated and all manner of other things with you but I still love you and I am sorry for the unkind words I said today. I do not truly believe them of you.'

Joseph takes his glasses off and sets them aside along with Defoe. He looks at Napoleon with great patience. Napoleon ponders for a moment longer then goes, 'and I am also sorry for making you King of Spain instead of letting you remain King of Naples like you preferred and I am sorry for leaving Elba thus setting in line a chain of events that lead to this current situation and I am also sorry for making you do my homework on Corsica when we were seven and never managing to keep my stockings up then blaming you for my state of undress to mother.' A tentative look. 'Shall I continue?'

'Perhaps you should just write me a letter. No, no, Nabulio it is all right. I thank you for your apology. I always know that you generally do not mean what you say in the heat of the moment. What was it Duroc said about you?'

'Oh no not the Duroc quote.'

Joseph, in an aproximation of Duroc's manner of speaking, "The emperor speaks from his feelings, not according to his judgement; nor as he will act tomorrow."

‘How perceptive of him...I miss him a good deal.'

'I know.'

'We are leaving for England tomorrow.'

'I know.’

Joseph searches his brother's face and finds sadness but it is a well-restrained emotion. At first he is annoyed because even now, even after it all, even in this intimate moment when it is just the two of them, he must be in control of himself but then he remembers being ten years old and going to France and how he wept and wept and made his brother's shoulder damp and Napoleon, who was Napoleonne then, just cried a few tears. Two, or three. And he swallowed a few times but couldn't speak. The empire just made him worse.

When do walls develop? Is it when you are taken from your family who you will not see for another fifteen years and thrust into a country whose language you do not speak, whose customs you do not understand and told to make friends with boys you cannot interpret? Is it when you witness war for the first time? Mobs running wild? Your friend taking a piece of shrapnel and dying atop of you as they cough blood onto your face? When do you bury yourself in irony and smiles and wry social observations?

Joseph wonders how much he has changed as well, in all those years. He looks back to Corsica and it feels as if it was ten minutes ago. Then, at the same time, it feels one hundred years ago.

Napoleon is staring at the fire and breathing very carefully. He is tapping out a rhythm on the armrest.

'I should go to bed, it is late.'

Joseph, 'no, no. Stay. We may not see each other for some time after this.'

Napoleon does not look at him. Joseph wants to say, You know I have seen you naked and squalling, right? You know I have seen you screaming in our father's lap because you scrapped your knee, ruined your breeches and everything is terrible?

But that would serve no purpose. Joseph instead goes to a shelf and retrieves a selection of books. 'Do you remember when father read Cicero to us for the first time?'

'Vaguely. I remember sitting on the floor of his study and listening to him read. I don't remember what it was about. It was our tradition whenever he was home. He would let you sit in his nice chair because you were always in a better state of dress than I.'

'You had just spent the day chasing around with the shepherd boys in the hills. You were filthy.'

'I was six. All six year olds are filthy.'

Joseph sits back down with the books and sets them on the floor between them. He says they should read from one, that he has chosen all those he remembers them going through when young. There is even Ossian, Napoleon's favourite though Joseph never quite understood why. And beneath that Virgil and Ovid and Caesar and Roland and countless others. Napoleon picks up Ossian and thumbs through a few pages.

'I was once accused of having Ossian dreams,' he says as he reads a section.

Joseph shrugs, 'there are worse dreams to have.'

'What do you want to read?'

Joseph picks up dusty Virgil and hands it over. Anything of his, for now. And really, it doesn't matter, they have all night.

Later, several books alter, Napoleon bids good evening. It is half two in the morning and Joseph says, 'I am glad you came. Even if we didn't succeed in anything remotely close to what we set out to do.'

'Next you must come to England. We have trolls.'

Joseph grasps his brother's hand and says that it is a plan then pulls Napoleon into a hug. He tells himself to not cry so much as he did when they were boys. The sense of separation is not as large as it was then. There has been a decreasing in the miles in the gulf that Joseph had imagined between them. Perhaps scouting for trolls would be just the thing. A vacation from sometimes-dreary Bordentown.

Pulling back Napoleon's hand stays on Joseph's neck and he looks his brother full in the face. It is like he is memorizing him, or seeing him afresh for the first time in many years. Joseph grins.

'Don't get into too much trouble, Nabulio.'

'Don't worry, Giuseppe, I have made enough noise for one lifetime. Come to England for the trolls?'

'For the trolls. Maybe we'll find some humanity in them, too.'

'Sure, but don't tell Wellesley, he'll have an apoplexy.'

Sometimes, Joseph thinks, it is like that poem wherein we go into the forest and carve the words of our love into trees and as the trees grow so do our loves become louder. There will be some forgotten people whose trees do not grow and their voices petrify, freeze in time. But they have been lucky, he thinks. Their voices are still heard, they are not reduced to living in silent woods barren of human contact and love. Their exile could have been thus - could have made of them unspeakable creatures not to be seen or heard or known.

A gentle thank you to all who stuck with me this week and through the strange and odd journey of this wee story. It went in an unexpected direction for me and I am glad you all kept with me as we jointly became emotional about brothers being brothers.

I also want to thank everyone who lovingly liked, reblogged, and commented. You are all so great and wonderful and supportive and it means the world. Really though, you’re all the best.

Thank you also to the anon who sent in the prompt of Napoleon and Arthur vs. Cryptids. I am not sure if this is what you wanted but thank you for the inspiration! It has been a pleasure to write.

<3 <3

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

BÍ MẬT LỚN NHẤT TRONG PHÉP ỨNG XỬ (1/3)

Chỉ có một cách hiệu quả nhất để khiến một người thực hiện điều ta mong muốn. Và, hãy luôn nhớ rằng không có cách nào khác, nếu chúng ta:

*Một tay giật tóc, tay kia gí súng vào đầu một người nào đó và thét lớn: “Có bao nhiêu tài sản, hãy đưa hết cho ta!”;

*Vênh mặt cau có và thách thức nhân viên của mình:“Nếu không làm việc chăm chỉ, tôi sẽ đuổi việc anh/chị ngay lập tức. Nhìn ra ngoài kia mà xem, biết bao nhiêu người muốn được làm nhân viên của tôi đấy!”;

*Cầm một cây roi mây to và quát con trai: “Đồ ngu! Nếu mày còn ham chơi làm dơ bẩn áo quần, tao sẽ cho mày 100 roi”.

Chúng ta cùng thử hình dung chuyện gì sẽ xảy ra trong ba trường hợp trên?

Mẫu số chung của cả ba trường hợp là những người bị chúng ta đe dọa sẽ làm theo những gì được yêu cầu. Nhưng, quan trọng hơn cả là họ sẽ làm với sự chịu đựng, khó chịu, cau có và phẫn uất. Trường hợp xấu hơn nữa là họ sẽ làm ngược lại. Người bị gí súng có thể quật lại người có súng, nhân viên sẽ siêng năng trước mặt và dối trá sau lưng hoặc đi tìm một chỗ làm khác có ông chủ cư xử tốt hơn, còn đứa bé thì sẽ vẫn trốn đi chơi và sau đó lẻn về nhà tắm rửa tươm tất trước khi bạn kịp phát hiện ra nó đã không nghe lời.

Thay vì cưỡng bức người khác phải làm theo ý mình, cách đơn giản hơn có thể khiến người khác làm bất cứ điều gì chính là: Hãy để họ làm điều họ muốn.

Nhà phân tâm học lừng danh Sigmund Freud(4) nói rằng: “Mọi hành động của con người đều xuất phát từ hai động cơ: niềm kiêu hãnh của giới tính và sự khao khát được là người quan trọng”. John Dewey(5), một trong những nhà triết học sâu sắc nhất của nước Mỹ lại có cách nhìn hơi khác một chút: “Động cơ thúc đẩy sâu sắc nhất trong bản chất con người là sự khao khát được thể hiện mình”.

Vậy bạn khao khát điều gì cho mình? Những đòi hỏi mãnh liệt nào đang bùng cháy trong bạn?

Hầu hết mọi người chúng ta đều mong muốn những điều sau đây:

1. Có được sức khỏe tốt và một cuộc sống bình an

2. Có những món ăn mình thích

3. Có giấc ngủ ngon

4. Có đầy đủ tiền bạc và tiện nghi vật chất

5. Có cuộc sống tốt đẹp ở kiếp sau

6. Được thỏa mãn trong cuộc sống tình dục

7. Con cái khỏe mạnh, học giỏi

8. Có cảm giác mình là người quan trọng

Hầu hết mọi ước muốn này thường được thỏa mãn, chỉ trừ một điều, mà điều ấy cũng sâu sắc, cấp bách như thức ăn hay giấc ngủ nhưng lại ít khi được thỏa mãn. Đó là điều mà Freud gọi là “sự khao khát được là người quan trọng” hay là “sự khao khát được thể hiện mình” mà Dewey có nhắc tới. Tổng thống Lincoln viết: “Mọi người đều thích được khen ngợi” còn William James(6) thì tin rằng: “Nguyên tắc sâu sắc nhất trong bản tính con người đó là sự thèm khát được tán thưởng”. Không phải chỉ là “mong muốn”, hay “ khao khát” mà là “sự thèm khát” được tán thưởng. “Sự thèm khát” diễn tả một nỗi khao khát dai dẳng mà không được thỏa mãn. Và những ai có khả năng thỏa mãn được sự thèm khát này một cách chân thành thì người đó sẽ “kiểm soát” được những hành vi của người khác.

Sự khao khát được cảm thấy mình quan trọng là một trong những khác biệt chủ yếu nhất giữa con người và những sinh vật khác.

Khi tôi còn là một cậu bé ở vùng quê Missouri, cha tôi có nuôi những con heo giống Duroc - Jersey ngộ nghĩnh thuộc nòi mặt trắng. Chúng tôi thường mang những chú heo này và những gia súc khác đến triển lãm ở hội chợ đồng quê cũng như các cuộc triển lãm gia súc khắp vùng Middle West. Chúng tôi luôn đứng đầu các cuộc thi với giải thưởng là những dải băng màu lam. Cha tôi thường gắn những dải băng này trên một tấm vải mỏng màu trắng. Khi bạn bè hay khách khứa đến thăm nhà, cha tôi thường mở miếng vải ra khoe. Ông cầm một đầu và tôi cầm đầu kia, rồi ông kể chi tiết với mọi người về từng giải thưởng với niềm tự hào ánh lên trong mắt.

Những chú heo chẳng hề quan tâm đến các giải thưởng mà chúng đã giành được. Nhưng cha tôi thì có. Những phần thưởng này khiến ông cảm thấy mình quan trọng.

Nếu như tổ tiên chúng ta không có sự khao khát cháy bỏng là cảm thấy mình quan trọng thì sẽ không bao giờ có những nền văn minh độc đáo và loài người chúng ta ngày nay chẳng hơn gì những loài động vật khác.

Chính sự khao khát được thấy mình quan trọng đã khiến một nhân viên bán tạp hóa ít học, nghèo khổ chịu khó nghiên cứu những quyển sách luật cũ kỹ mà cậu tình cờ tìm thấy dưới đáy một cái thùng đựng đồ lặt vặt được cậu mua lại với giá 50 xu. Có lẽ các bạn đã nghe nói đến tên anh chàng bán tạp hóa này rồi. Tên anh ta là Lincoln.

Và cũng chính sự khao khát cảm thấy mình quan trọng đã thúc đẩy Charles Dickens viết nên những tiểu thuyết bất hủ. Sự khao khát này cũng là động lực để Christopher Wren(7) viết những bản giao hưởng của mình lên đá. Và chính sự khao khát ấy cũng đã giúp Rockefeller kiếm được hàng triệu đô-la mà hầu như ông chẳng cần dùng đến một đồng trong số đó!

Khi chúng ta mặc quần áo thời trang, dùng hàng hiệu, đi những chiếc xe thời thượng, dùng điện thoại di động sành điệu, kể về những đứa con thông minh, chính là lúc chúng ta thể hiện sự khao khát được tỏ ra quan trọng trước mọi người.

Tuy nhiên, nỗi khao khát này cũng có mặt trái của nó. Không ít thanh niên gia nhập các băng nhóm, tham gia những hoạt động tội phạm, sử dụng heroin và thuốc lắc như để khẳng định mình, để được xã hội nhìn họ như những “Siêu nhân”. E. P. Mulrooney, Ủy viên Cảnh sát New York, cho biết: Hầu hết những tội phạm trẻ tuổi đều thể hiện cái tôi rất lớn. Yêu cầu đầu tiên của chúng sau khi bị bắt giam là đòi xem những tờ báo tường thuật về chuyện của chúng như thế nào.

Chính cách mỗi người thể hiện sự quan trọng của mình nói lên rất rõ tính cách thật của họ. John D. Rockefeller tìm được cảm giác về tầm quan trọng của mình bằng cách đóng góp tiền để dựng nên một bệnh viện hiện đại ở Bắc Kinh để chữa cho hàng triệu người nghèo mà ông chưa bao giờ gặp và cũng chưa hề có ý định gặp. Dillinger thích có được cảm giác về tầm quan trọng của mình bằng cách giết người cướp của. Khi bị FBI (Cục Điều tra Liên bang Mỹ) săn đuổi, hắn ta đã lao vào một trang trại ở Minnesota và dõng dạc tuyên bố: “Ta chính là Dillinger!” với niềm tự hào không cần giấu giếm.

Thực ra, đây là một yếu tố rất “người”. Gần như ai cũng thế. Nếu không xem sự khát khao được là người quan trọng là một thuộc tính của con người thì có lẽ nhiều người sẽ kinh ngạc khi biết rằng, ngay cả những nhân vật nổi tiếng nhất, những con người được tôn vinh nhất trong lịch sử loài người cũng thế. Người ta có thể ngạc nhiên tự hỏi vì sao người vĩ đại như George Washington cũng muốn được gọi là “Đức Ngài Tổng thống Hợp Chủng quốc Hoa Kỳ”. Người ta lại thắc mắc tại sao một con người tài trí như Christopher Columbus(8) cũng muốn có được danh hiệu “Thủy sư Đô đốc Đại dương và Phó vương Ấn Độ”. Và, người ta sẽ càng ngạc nhiên hơn nữa nếu biết rằng nữ hoàng Catherine vĩ đại không chịu mở bất kỳ bức thư nào nếu không có lời đề bên ngoài: “Kính gửi Nữ Hoàng Quyền uy”.

Các nhà tỷ phú chỉ đồng ý tài trợ cho cuộc viễn chinh của thủy sư đô đốc Byrd đến Nam Cực năm 1928 với yêu cầu duy nhất là tên của họ phải được đặt cho những dãy núi băng ở đó. Victor Hugo không khao khát gì hơn là thành phố Paris được đổi thành tên ông. Ngay cả Shakespeare, người được mệnh danh là người vĩ đại nhất trong số những người vĩ đại, cũng muốn làm vẻ vang thêm tên tuổi của mình bằng cách xin hoàng gia ban cho một tước hiệu quý tộc.

Đôi khi, có người tự biến mình thành tàn tật để có được sự thương hại, sự quan tâm của người khác, để cảm thấy mình quan trọng. Đệ nhất phu nhân McKinley tìm cảm giác quan trọng bằng cách bắt chồng bà, Tổng thống William McKinley của Mỹ, mỗi ngày phải tạm gác việc quốc chính một vài giờ để ở bên giường bà và ru bà ngủ. Bà nuôi dưỡng khao khát cháy bỏng được mọi người chú ý bằng cách yêu cầu ông phải ở bên bà ngay cả khi bà đi khám răng. Có lần, bà đã làm ầm ĩ khi ông “dám” để bà một mình với nha sĩ vì phải tham dự một cuộc họp quan trọng với Bộ trưởng Ngoại giao.

(4) Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939): Bác sĩ thần kinh, nhà tâm lý học, nhà phân tâm học nổi tiếng người Áo.

(5) John Dewey (1859 – 1952): Nhà triết học, tâm lý học, nhà cải cách giáo dục nổi tiếng người Mỹ.

(6) William James (1842 – 1910): Nhà triết học, tâm lý học, nhà nghiên cứu chủ nghĩa thực dụng nổi tiếng người Mỹ.

(7) Christopher Wren (1632 - 1723): Kiến trúc sư, nhà thiết kế, nhà thiên văn học và hình học người Anh thế kỷ 17. Ông từng thiết kế 53 nhà thờ ở Luân Đôn, trong đó có Thánh đường St .Paul.

(8) Christopher Columbus (1451 – 1506): Nhà hàng hải, nhà thám hiểm người Ý, người phát hiện ra châu Mỹ năm 1492.

0 notes

Text

Free Range Pig Farming on the Homestead

By Al Doyle – With free range pig farming, you’ll be raising your own high-quality meat. Like other home-raised food products, meat from a homestead hog is far superior in texture and flavor to the stuff wrapped in cellophane in the meat section of the local grocer. If sausage making interests you, the numerous odd pieces and scraps from a hog will provide plenty of raw material for new recipes and experimenting.

Free Range Pig Farming: The Modern Homestead Pig

Dig through the musty stacks at the library or find an old farm book and look at the photos of the blimp-shaped animals with stumpy legs. Those bulky beasts are Poland-China, Chester White and Duroc-Jersey pigs that were raised for both meat and lard. A generation or two ago, lard was much more popular than it is today, and a pig that could produce large quantities of leaf lard (the pure white fat from near the kidneys) along with meat was highly prized. With today’s widespread use of vegetable oils, lard consumption is much lower, and it is more of a byproduct of hog production. Even the traditionally “chuffy” or heavy breeds tend to be smaller and leaner than they were in the past.

Ready to Start Your Own Backyard Flock?

Get tips and tricks for starting your new flock from our chicken experts. Download your FREE guide today! YES! I want this Free Guide »

Some of today’s better-known hog breeds raised through free range pig farming include the distinctive-looking Hampshire pig, which is black with a white “belt” near the front legs; the mostly black Berkshire, which is known for lean carcasses; and the droopy-eared Black Poland, which has a reputation for hardiness and a color pattern that is similar to the Berkshire. Spotted pigs have a wide variety of color patterns. This droopy-eared breed is sometimes chosen for its hardiness and lengthy carcass.

White or light-colored pigs are fairly common, and there are several popular breeds. Because of their tendency to produce large litters, Yorkshires are sometimes referred to as the “mother breed.” Like other breeds that end in “shire,” the Yorkshire is of English origin and is known for rapid growth. The droopy-eared Landrace is commonly found in indoor/confinement breeding arrangements. This long-bodied breed is known for its mellow temperament. The aforementioned Chester White is known as a good breeder and mother, and they are a popular choice for crossbreeding. The Chester White is named after Chester County, Pennsylvania, its place of origin.

Aside from personal preference for a certain color or pattern, is there any reason to choose dark or light-colored swine for free range pig farming? Conventional wisdom suggests that darker hogs should be raised in colder climates, while light-colored or white pigs are the better choice in warmer areas. While this may be true, keep in mind that pigs of any color don’t fare well in very hot conditions. We’ll have more on this topic in the housing section.

Homesteaders, as well as commercial producers, generally seek pigs that will grow quickly to a meaty size with a high proportion of lean to fat. While a full-grown pig can weigh upwards of 600 pounds, the vast majority of pigs are butchered when they reach 200 to 250 pounds. An eight-week-old weaned piglet in the 35- to 40-pound range purchased in the spring can easily reach prime weight by fall, the traditional time for hog butchering.

Which breed should you choose for free range pig farming on your homestead? The vast majority of meat animals are crossbreeds, and this is almost certainly what you’ll get if you purchase a few piglets from a local farmer or stock auction. For all practical purposes, the specific breeds that are crossed for a litter of piglets are less important than the quality of the individual animals involved. A prime boar and sow from what might be considered “inferior” breeds will produce better stock than two mediocre specimens from allegedly “superior” breeds.

The differences in various pig breeds can be much smaller than in other animals. A University of Wisconsin study of nine pig breeds showed that the dressing percentage (the amount of meat obtained from a carcass) had a very narrow range. The relatively rare Tamworth brought up the rear with a 70.8 percent dressing rate, while the Chester White’s first-place ranking of 72.9 percent was just over two percent higher. On a 220-pound young pig, the difference between those breeds is less than five pounds. Take an above-average Tamworth and an ordinary Chester White, and that margin will be even smaller.

In free range pig farming, management of the homestead animal is the most important consideration. The farmer who feeds his hogs a balanced diet, provides adequate housing and is attentive to their needs will reap the benefits of his efforts. With that said, free range pig farming is not a rigid, lockstep type of enterprise. Pigs can be tended in an endless variety of ways. Once you get involved, you’ll probably come up with some methods for free range pig farming that are especially well suited for your unique situation.

Free Range Pig Farming: Finding Good Stock

When two purebred pigs or a purebred and crossbreed are mated, the offspring pick up the positive traits of the parents, but they don’t carry over to the succeeding generation. With that in mind, what should you look for when shopping for crossbreeds? How can the novice find decent stock for the free range pig farming on the homestead?

Young animals should be energetic and active, with clear eyes and a healthy pink skin. Pass if a young pig has respiratory problems, coughs, wheezes or has swollen leg joints or other obvious flaws. When in doubt, wait for a better specimen.

Size is an important factor when choosing pigs for free range pig farming. Look for the biggest and healthiest piglets from the litter. It’s human nature to pull for the runt of the bunch, but it doesn’t work when choosing an animal for meat rather than as a pet. Runts usually stay that way, and you’ll end up paying the price in less meat for the table along with more frequent health problems.

One Canadian Countryside reader offered an unusual cure and supplement for runts. She feeds them a teaspoon of nutmeg once a day for four days. She claims it works, and it certainly wouldn’t cost much to try this non-pharmaceutical remedy.

Sometimes described as “sociable,” pigs enjoy the company of a fellow porker. Another mouth at the feed trough also provides the pig with competition for food and an incentive to eat and put on weight faster.

While there is the additional cost of feeding another pig, other chores related to free range pig farming such as watering and fencing will require the same amount of effort whether you’re raising a solo animal or a pair. If two pigs will provide you with more meat than needed, it’s hardly difficult to distribute the excess.

One former city dweller who now does free range pig farming on his new homestead sells his excess pork to urban friends. Even with the cost of processing, they pay a little less than grocery store prices for factory farm pork and get organically raised meat at a big discount. The homesteader clears a profit, and everyone is happy with the arrangement. Surplus hams, chops and bacon also make excellent gifts, and the cost to the giver is a fraction of what similar “gourmet” quality products would cost.

What about livestock auctions? They are definitely more of a risk for the first-time buyer or anyone with limited experience. You won’t be able to check out the piglets and their parents in familiar surroundings. Being transported from mama to a strange place will stress young pigs, and they could be exposed to sick animals.

This doesn’t mean that you can’t get decent stock for a fair price at an auction, but going to a local farm with a reputation for quality stock might be the wiser route for the newcomer. If the idea of buying at auction appeals to you, it could pay to bring along a more experienced advisor.

Should you choose barrows or gilts when buying pigs? The barrows put on weight a little faster, while gilts are slightly leaner. Since the pigs will be butchered before they reach breeding age, it’s not a major issue. Stick with the animals that have the most potential for a meaty carcass.

Hopefully, you’ve done some homework before buying those first piglets for your venture in free range pig farming. That means attending county fairs, livestock sales, farms, auction barns and other places where you can observe pigs first-hand and get some basic knowledge of the species. Part of your education should include visits to a homestead type of pig setup where others are doing free range pig farming, rather than a factory farm that raises hundreds of hogs. The contacts and knowledge that can be gained from a small-scale operation will be of much greater value than learning the procedures of a corporate enterprise.

Free Range Pig Farming: Fencing and Housing

When you decide to start free range pig farming, this is one area where planning and working ahead will pay big dividends with free range pig farming. The time to put together a decent shelter is well before the pigs are brought home. Unfortunately, that doesn’t always happen.

When it comes to fencing, swine offer a unique challenge to the homesteader engaging in free range pig farming. Wiring and posts must be sturdy enough to withstand challenges from a 200-pound plus porker, but it must be low and fine enough to prevent a 35-pound weaner from slipping out. Since pigs of all sizes are burrowers, this must also be taken into account when putting together fences and gates. When designing a system, imagine a 250-pound beast scratching its back on a post (hogs love being scratched) or just pushing on a fence to see if it will hold up.

Choices include woven wire, barbed wire, wooden gates and barriers, electric fencing, sturdy metal hog panels or any combination of the above. Farm author and veteran pig breeder Kelly Klober recommends a single strand of charged wire four inches off the ground to contain small pigs. If your animals are more than 80 pounds, an electrified strand a foot off the ground will suffice.

Rolls of woven wire (commonly known as hog wire) comes in heights of 26 and 34 inches. Combining this with the single-strand electric fence, on the pig side, provides additional protection.

When it comes to fence posts, Klober places rock-solid durability at a premium.

“A Missouri fencing trademark was and is eight-foot-long crossties set three feet into a concrete footing for corner posts,” he wrote. “Double-bracing corner posts with treated poles or timbers will further strengthen their holding power. There is also now a system that makes it possible to double-brace seven-foot-long steel posts with other steel posts and use them for solidly anchored fence corners.”

Line posts don’t need to be as stout as corner posts, but they should be tough enough to withstand battering. They are set up at 10 to 15-foot intervals. Posts can be set farther apart in long, straight stretches, and the number will have to be increased in rolling terrain or other uneven areas

For an electrified fence, you’ll need a charger, which is a small transformer. The unit has to be protected from the elements, so if it’s not in the barn, you’ll have to place it in a waterproof box or a similar container. Chargers can be run on a regular electric current, solar power or batteries.

Klober recommends a minimum of 250 square feet per pig in a fenced drylot. If the area is flat or has more moisture than normal, the plot will have to be increased accordingly to provide adequate drainage and to prevent the hogs from rooting up the entire area. Odd little bits of land and hilly parcels are good places for a drylot.

In his book Storey’s Guide to Raising Pigs, Klober noted that he maintains a 10- to 20-foot strip of sod at the bottom of each of his drylots. This filters runoff from the hog pens and prevents erosion. If excessive rooting and digging become a problem, then it might be time to ring your pigs.

A specialized tool is needed to place a soft metal ring on the pig’s nose. This will cause the hog to feel some pain when digging with his snout and serves as a strong deterrent. Outdoor drylots will need to be rotated every year or two to break up the life cycles of diseases and parasites. The plot can be tilled to repair digging damage, or it can be left alone to grow grass and native plants.

Hog panels and simple wood fences (some thrifty folks use recycled pallets) are well suited for making gates and portable fences. More on this topic when we get to the pastured pig.

In many cases, a suitable shelter is already available. It could be an old hog pen, barn, shed, chicken coop or other existing structure that would be adequate for housing one to three pigs. The old building might need some minor repairs, cleaning or stronger fencing, but it will get the job done.

If you’re starting from scratch, be selective when picking a location for a hog pen, as just any old vacant spot won’t do. When possible, it should be close to where you’ll store the pig food. Water should also be within easy distance.

Pigs have a reputation for defecating in one spot, and that is true to a point. The animal won’t soil his sleeping quarters, but most anything else is fair game.

In his experience, Jd Belanger, former Countryside editor and author of Raising the Homestead Hog (Rodale Press, 1977), notes that pigs routinely move 10 to 12 feet from their favorite spot to defecate. If the animal is in a square enclosure, that means he could leave manure just about anywhere. In a narrower or more rectangular pen, the pig will gravitate to one spot, and it will make manure removal that much easier.

Since pigs don’t fare well in summer heat, this will also need to be considered when setting up a pen. Some kind of shade or shelter from the sun should be provided. When possible, a spot that doesn’t have a southern exposure should be considered. One farm author suggested housing hogs in a spot that duplicates a shady forest as much as possible. He reasoned that since wild pigs prefer such an environment, their domestic cousins would do the same.

Since fencing and housing can be as high as 20 percent of the cost of production, savings in this area can really pay off in the long run. For a hog or two, the simple A-frame shelter is a popular choice.

“We did a little A-frame for our pigs,” reports one Wisconsin homesteader. “All it took was some 2x4x8s, some roofing and a few other materials.” The A-frame is especially well suited for portable housing.

You can get more elaborate and still have a shelter that is light and transportable. A simple-to-construct shelter can include doors, removable panels for ventilation and a covered feeding area. Plan on at least six feet of space per pig when building a shelter. This guideline is often violated by factory pig farms, but it shouldn’t be much of a problem for the homesteader.

Free Range Pig Farming: Feeding

This is one area where free range pig farming and homesteading are an ideal match. Even the moderately successful gardener or dairyman goes through times when garden produce and goat or cow milk is in abundant supply—so abundant that much of the bounty goes to waste.

Instead of tossing those surplus zucchinis, tomatoes, squash, cucumbers and other vegetables onto the compost pile, why not use them to supplement the pig’s diet? The excess can be used to put pork on your table, and the manure byproduct goes on your crops for future harvests. It’s an ideal setup for the homestead that engages in free range pig farming.

Pigs have a single stomach that has some similarities to a human stomach. Like people, they are capable of eating and enjoying a wide range of plant and animal products. Hogs will consume a staggering variety of leftovers and waste items and convert them into chops and ham. One trout farmer raises a few pigs on the side. Rather than discarding the large quantity of fish heads that he processes, those trout leftovers are fed to the pigs.

The porkers eagerly gobble up these treats along with anything else they deem edible. To prevent any fishy flavor in the finished product, the trout farmer puts his hogs on a grain-only diet six weeks prior to slaughtering. In addition to paring his feed bill considerably, this frugal farmer also keeps his garbage bill and burden on local landfills to a minimum.

Pumpkins were a favorite hog feed a century ago, and they are still a good choice for the organic hog farmer. Early 20th-century veterinarian Dr. V.H. Baker strongly recommended a blend of pumpkin and grain cooked together as a nutritious pig feed. With an eye to the future, Baker saw the trend that has culminated in factory farming and concrete-floored confinement housing for large numbers of pigs. In objecting to such practices, Baker sounded much like a modern organic homesteader who is interested in free range pig farming.

He wrote, “I believe the purely artificial breeding and feeding of breeding stock, the indiscriminate ringing, the absence of roots and the feeding of breeding animals almost exclusively on corn, have, in many cases, so enfeebled the constitution of swine that they have become an easy prey to the various epidemics and contagious diseases that, of late years, have carried off so many. And I believe, also, that the utmost care will be necessary in the future to guard against this disability.”

Baker declared, “Our methods of feeding, together with a greater variety of food material, is conducive to the health of the animal.”

Homestead dairy items, especially “byproducts” such as skim milk and whey, should be fed to pigs whenever possible. Perhaps the most enthusiastic endorsement of this practice came from Jd Belanger in his book Raising the Homestead Hog.

He wrote, “The hog will make excellent use of what would otherwise be waste. And do pigs love it! They’ll learn to recognize you coming with the bucket, and they’ll get so excited that they’ll make those ‘come-and-get-it’ dogs in the tv dog food commercials look about as eager as mice coming to a baited trap.”

Belanger added, “On the homestead, milk and milk byproducts are the most valuable feeds available. Nutritionists tell us that a pig can thrive on corn and about a gallon of skimmed milk a day, so if we add comfrey and some of the other items we’ve covered, how can we lose?

“Once again, the best is yet to come, for we run into another unidentified factor! Milk and milk byproducts hold in check some of the internal parasites of swine. This has been observed, and has also been backed up by research. But even scientists don’t know why or how. That doesn’t really matter to homesteaders who feed milk to eliminate the need for tankage and fish meal and get an ‘organic vermifuge’ in the bargain.

“Skim milk is higher in protein than whole milk and has about twice the protein of whey…Skim milk is the best possible source of protein for swine, especially young swine. A young hog should get about a gallon to a gallon-and-one-half of milk per day. While this amount will be a smaller part of the ration as the pig grows and eats more, protein needs also decrease then.”

Whey can also be a real asset to the small producer. According to researchers at the University of Wisconsin, feeding fresh, sweet whey to pigs cuts feeding expenses significantly while maintaining carcass quality. In addition to the byproduct of your own cheesemaking, cheese factories are the best source for whey. Only sweet, fresh whey should be fed to hogs.

Pigs readily consume whey, and it reduces their corn consumption as well as the need for soybean meal supplements. Since whey is about 93 percent water, no other liquid should be offered when whey is served. Since whey corrodes metal and concrete, it must be fed in wood, plastic or stainless steel containers. Once again, pigs can take a so-called “waste” product and make good use of it, which is a classic example of the homestead philosophy at work.

Comfrey is another pig food that gets high marks from Belanger. He suggests regular feedings of plants and leaves from this perennial.

“I consider it an ideal homestead plant, for reasons the USDA would never consider,” he said. “Comfrey is easily grown on a small scale, much more easily than alfalfa or clover. The best way to harvest it is with a butcher knife or machete, a system I still use for a hundred hogs and more. You can get a crop the first year… It’s a very attractive plant and can well be grown in borders and flower beds.”

Often touted as a potent herbal remedy and healing agent, comfrey has a unique distinction.

Belanger wrote, “Scientists already know that with the addition of vitamin B12, the protein levels of swine rations can be reduced appreciably. In addition, most of the antibiotic supplements for swine contain not only antibiotics but also vitamin B12. Now get this: comfrey is the only land plant that contains vitamin B12.

“This vitamin is one of the most recently discovered and is commonly supplied in tankage, meat scraps, fish meal and fish solubles. It is of benefit to humans and other animals afflicted with pernicious anemia. Its relationship to protein needs is interesting to homesteaders, as is its entire background as one of the ‘unidentified factors’ in nutrition until quite recently.”

Even though this prolific plant grows as high as five feet, larger cuttings are too coarse for pig feed, and the nutritional value drops once the plant blossoms. Cutting comfrey at one to two feet is ideal.

Comfrey grows with minimal attention, and it will produce heavily in almost any climate. Most importantly, pigs will eagerly gobble this nutritious plant down.

“I don’t claim to be a nutritionist. I don’t know why comfrey is good hog feed,” Belanger wrote in Raising the Homestead Hog. “All I know is that my pigs of all ages love it, and the young ones especially slicken up like fat little pork sausages when they get their daily ration of comfrey.

“The homesteader can add to that the ease of growing it (compared with alfalfa and clover); the low cost in terms of time, equipment, cash and longevity of stand; and particularly the ease of harvesting and feeding. Especially if you decide not to purchase antibiotic-vitamin B12 supplements, comfrey just makes a lot of sense.”

Pigs will eat items such as citrus peels and other “trash” not consumed by humans. What about the tales that pigs eat garbage as part of their diet? There is some truth to that, but here’s the rest of the story.

First, much of the so-called “garbage” includes scraps, leftovers, imperfectly prepared foods and various edible items cooked by restaurants, hospitals, and other large-scale food service providers. These products were originally intended for human consumption. By law, this garbage must be heated at 212ºF (100ºC) for 30 minutes to kill any traces of the Trichinella spiralis parasite, which manifests itself as the deadly trichinosis infection in humans and is spread by undercooked pork. The soupy product is then fed to pigs, who convert something that might have ended up in an overflowing landfill to high-quality meat.

Even though hogs have fattened successfully on diets that included everything from leftovers to old baked goods scrounged from dumpsters, keep in mind that grain should play an important role in feeding.

Regardless of what kind of grain is used as hog feed, it will need to be ground to ensure better and more complete digestion by the swine. While corn is by far the most popular grain, Belanger picked barley as a good option when corn is unavailable.

Although it has more fiber and bulk than corn, barley has slightly more protein along with less amino acid balance. Oats score well in the protein department, but its fiber content is too high to be used as a finishing ration. This grain is a good choice for lactating sows and breeding stock. Oats should make up no more than 30 percent of the diet of feeder pigs.

While wheat is equal to or even superior to corn as a feed grain, it does cost more, and corn is easier to grow and harvest for the homesteader. Outside the corn belt, grain sorghums are often grown in semi-arid areas as pig feed. They are an acceptable choice, as sorghum is comparable to corn in nutritional value. Hogs don’t find rye as palatable as other grains, so limit it to 20 percent of a ration.

While thriftiness is important, it can be taken to extremes. Don’t feed your hogs scabby (diseased) barley or ergot-infested rye, as health problems ranging from depressed growth rates to abortions and even death may occur.

Depending on the age and nutritional needs of your pigs, grains will need to be blended with other products such as alfalfa hay or soybean oil meal. Eight-week-old weaners need a 17 or 18 percent protein feed, which can be purchased in pelleted form from a feed store. Once the animal reaches 12 weeks, something in the 13 to 15 percent protein range is best.

If you’re considering soy products as part of your pig’s diet, don’t use raw soybeans for feed! They cause soft pork, since uncooked soybeans contain a trypsin inhibitor or the antitrypsin factor. Trypsin is an enzyme in the pancreatic juice that helps absorb protein. The antitrypsin factor is eliminated by cooking, which makes 44 percent protein soybean oil meal the product of choice for the homestead hog.

While buying grain in bulk or growing your own corn and grinding and mixing rations is the least expensive way to feed a pig, there is something to be said for bags of pre-mixed pellet feed. Small producers may not be able to make the minimum purchases necessary to save money on bulk grain. With self feeders, several days’ worth of hog pellets can be added in just a few minutes.

You’ll need to store feed in rodent-proof containers. Metal or sturdy plastic garbage cans along with 55-gallon drums (which will hold 350 pounds of feed) are sufficient for meeting the feed requirements of a pair of pigs.

One final caveat on commercial feeds: Many pig rations now contain low-dosage antibiotics and other drugs. While this may not be a major issue to some homesteaders, others who are dedicated to fully organic production will need to make sure that the feed they buy meets their standards.

While pellets in an automatic feeder must be kept dry, food placed in a hog trough can be mixed with water, milk or whey if desired. Will your hogs prefer their rations in this manner, and is it worth the extra effort to you? It’s one of those things that will be determined on an individual basis.

Some producers allow their pigs to eat as much as they want (this is known as “free choice” or “full feeding”), while others limit food to 90 percent of their appetite. Once a pig reaches 75 pounds, he will consume one pound of feed for every 25 to 30 pounds of body weight each day. Weaners will need more food in relation to their body weight than older pigs, and they require a higher protein content than the regular mix.

The 90 percent method is suitable for the person who wants a low-fat carcass. It will take a little longer to get a hog to butchering weight this way, but it is an option for those who prefer leaner cuts. It also requires a more hands-on approach, as extra feed will have to be removed within 20 to 30 minutes after feeding time.

When you start doing free range pig farming, be very diligent when it comes to maintaining an adequate supply of water. A growing pig can consume as much as seven gallons on a hot day. Water can be stored in troughs, salvaged materials such as old washtubs and tanks, or in fountain-style drinkers that can be attached to 55-gallon drums. A sturdy homemade pig waterer will be required, though—hogs will tip a trough or tub over on a hot day as they attempt to climb in and wallow in the cool water. Klober welds iron bars across the tops of his troughs to prevent his hogs from jumping in.

Water is vital not only for the health of the pig, but also for the efficiency of raising free-range pigs on your homestead.

From the weaner stage to butchering at seven or eight months, a pig converts feed to meat at a ratio of roughly 3.2 to 1. When temperatures rise above 80º F, that ratio drops dramatically, and pigs burn up calories just to stay alive rather than fattening up hams and loins.

Be extra diligent about providing a generous supply of water in hot conditions. If the heat is intense, it might pay to extend a garden hose to the hog pen and create a wallow as the water mists the enclosure. Make sure the wallow is in the sunny part of the pen.

Free Range Pig Farming: The Pastured Pig

Even more than money, time is the one asset that is always in short supply for the active homesteader. That means working smarter instead of working harder should be the goal of the small farmer who is raising free range pigs, and one way to do this is to let your pigs feed themselves by raising pigs on pasture.

Sound ridiculous? For at least part of the year, movable fencing will allow you to place animals where there is surplus food. One example would be a harvested potato field or a patch of Jerusalem artichokes, turnips, rutabagas or another root plant. If there’s food around, the pigs will find it and dig it out. In addition to using produce that would otherwise go to waste, the pigs will do a magnificent job of tilling and fertilizing the soil without fossil fuels or chemicals as they root around.

Pigs can also be placed in standing grain fields after they have ripened and are starting to turn brown. They’ll clean up the grain with great efficiency and provide tilling and fertilizer without any effort on your part. This “old-fashioned” method is scorned by the corporate farm types, but it always generates interest among homesteaders.

Pigs will graze on alfalfa and other forage crops. While hay alone won’t provide a pig with all of his dietary needs (you’ll need to supplement with grain), it does lighten your workload and expenses. Most importantly, it also means a healthier pig. According to Belanger, pigs need more than 30 vitamins and minerals for optimal health. How can you provide such a complex mix without an advanced degree in chemistry? Let the pig do the work!

Free range pig farming is one of the best ways to ensure that your animals get all of the nutrition they need. All of that rooting, digging and foraging in the dirt provides pigs with many of the elements they need. Even those who raise pigs indoors in confinement settings recognize this to some degree. Sick pigs are often given a chunk of fresh sod, some dirt and even a little time in the sun. In many cases, this drug-free cure does the trick.

While the “tiller pig” concept is usually thought to be a summer and fall technique, it can also be employed in the spring. Done properly, it may save you the cost of renting or buying and maintaining a rototiller, according to one low-budget but creative homesteader. “Get the pigs in the spring a month before you plant the garden,” he advised. “We start our pigs in portable pens around wherever our garden area will be. We supply them with oats and table scraps. The garden is all dug up and fertilized, and they also dig up rocks.” Just another reason to consider raising free-range pigs on your homestead.

Free Range Pig Farming: Health Care

Routine health care is very important to success at free range pig farming on your homestead. One of the first procedures done on newborn pigs is to trim the two wolf teeth—more commonly known as needle teeth—so the nursing piglet doesn’t damage his mother’s teats. These choppers are found on each side of the upper jaw. The young animals are also given iron shots somewhere between three to five days after birth to build up depleted reserves of the mineral. If this is ignored, anemia may follow.

While pigs were described as “super-hardy animals” by one enthusiastic small farmer, they do require some care and attention, especially if your goal is organic production. Starting out with quality stock will do more to promote good health than a boxful of medicines.

Parasites are another concern of those doing free range pig farming. Worming medication may be given to piglets. Klober recommends an injection of Ivomec, but worming medicine is also available in treated feed or can be added to drinking water. Male piglets who won’t be kept for breeding stock should be castrated at four to seven days of age. While many raisers wait until pigs are at least five weeks old to do this job, it’s easier on the swine when the procedure is performed earlier.

Because doing free range pig farming means that your homestead hog will be on grass and soil rather than concrete, the next important step in controlling worm and parasite infestation is regular rotation of fenced lots and pastures. One year (or less) in a given area followed by a year off will do much to break up parasite life cycles.

The pig louse and mange mite are spread by pig-to-pig contact. Pig lice suck blood from their hosts, and this can lead to anemia. Mites tend to congregate in the head and ears, and they often cause obvious skin irritations. External sprays and liquids are recommended to eliminate these pests, but they can’t be applied shortly before farrowing (giving birth) or butchering.

Prompt and regular manure removal will go a long way towards fending off worm infestations. For example, if worm eggs show up in the pig’s feces, the shovel and a trip to the manure pile will eliminate that problem. When the manure is left to sit around, the pests will have an excellent opportunity to infect your pigs.

Belanger succinctly drove home the importance of pasture rotation and diligent manure control in Raising the Homestead Hog.

“Another worm with a slightly different life cycle is of interest to homesteaders,” he wrote. “That’s the lungworm. Swine first acquire it by eating infested earthworms. How do the earthworms get infested? By feeding on swine manure that is infested with the eggs of the lungworm that lives in the swine. The cycle, again. This cycle demonstrates the need for pasture rotation.”

He concluded, “For at least part of the cycle, parasites can exist only in the bodies of their hosts. That means they start, and end, with the pigs. Buying clean stock cannot be overemphasized. Your chances for raising worm-free pigs are greatly enhanced if the premises of the seller indicate that sanitation is an important part of his management.” And yours, as well.

Free Range Pig Farming: Pig Diseases

Learning how to recognize pig diseases is essential to success at free range pig farming. Look for any of these symptoms and their associated diseases in your animals, and seek appropriate veterinary care as needed:

Anthrax kills by suffocation and blood poisoning. Infected pigs usually have swollen throats, high temperatures, and pass blood-stained feces. Anthrax bacillus can survive in the spore stage for years, and it also afflicts humans.

Did you pass on a weaner who was sneezing? It may have been an early sign of atrophic rhinitis. Infected swine have a wrinkling, thickening, and bulging of the snout. At eight to 16 weeks, the snout may twist hideously to one side. Death is usually due to pneumonia.

Rhinitis may be tied to a calcium-phosphorus imbalance or deficiency. Affected pigs can be put on a creep feed that contains 100 grams of sulfamethazine per ton of feed.

Also known as infectious abortion, the greatest danger of brucellosis is that it can be passed onto humans as undulant fever. Other forms of this disease also show up in cattle and goats. It is passed by contact with infected animals or contaminated feed and water. Swine that are found to be infected are destroyed.

Highly contagious hog cholera destroyed numerous herds earlier this century, but it is much rarer today. The symptoms include fever, loss of appetite, weakness, purplish coloring on the underside, coughing, eye discharges, chilling, constipation and diarrhea. Diagnosis can be difficult because some pigs die without showing any symptoms at all.

Swine dysentery can strike pigs who have gone through central markets or auctions. Afflicted animals pass copious amounts of bloody diarrhea. Sanitation and good stock are the keys to preventing this killer.

Free Range Pig Farming: Butchering

Butchering a pig is an old rural American tradition that is still very much alive in farm country and on the homestead. The feeding and growth cycle culminates at the ideal time for this task. Generally, hog butchering takes place in fall after the crops and garden have been harvested, before the cold blasts of winter, but when the weather is brisk enough to chill the meat without the need for a walk-in cooler.

Pigs should be kept off feed for a day or so before butchering, as this will leave less undigested food and waste in the swine’s system. Provide water to the animal. One popular method for delivering the coup de grace in the U.S. is with a .22 caliber rifle. The .22 LR bullet should be placed a fraction of an inch to the left of dead center on the hog’s skull, just above the left eye.

Once the pig is dead, the jugular vein is severed for bleeding. It should take around 10 minutes for the pig to bleed out. Some homesteaders prefer tying a rear leg with a rope and doing the job with a sharp knife and a quick, decisive incision to the jugular vein rather than using a gun.

Free Range Pig Farming: Scraping or Skinning?

There are two schools of thought on what to do with a pig’s hide and hair. Traditionally, the hair is scraped off the hide, leaving the hide on the meat until it’s cut up. The alternative is to skin the animal. Some people think skinning is easier. However, hams keep better with the skin on.

If you plan to scrape the hair off the hog, a large container for dunking the carcass in hot water will be needed. Typically, a 55-gallon drum, old bathtub or stock tank is used for this task. The water will need to be heated to at least 145ºF before the hog is dunked.

Dunk the carcass for a two- to three-minute soak, remove, and begin scraping hair off with a bell scraper. This venerable farm tool will pull the hair off when it is applied with a steady, circular motion. A dull knife can be used for hair removal if a scraper isn’t available. A second session in the boiling water may be needed as the hair becomes more difficult to remove. The head and feet are the hardest areas to scrape. Once the job is done, even a black swine will be white.

For skinning, Klober recommends an obstruction-free site with plenty of room to work. The hog is placed below a supporting pole. A short, vertical cut is made just above the hoof of both rear legs.

A strong leg tendon is carefully exposed and pulled from the tissue. The tendons are hung on a bar attached to the hoist, and the carcass can be lifted. If the tendons tear, the foot is tied on with wire.

Circular cuts are made above both hooves, and the skin is cut and pulled off much like what is done with a deer, except that you’re working from back to front. A good skinning knife will be needed to pull the skin off the muscle. A circular incision through the skin at the top of the tail will allow you to skin the hams.

Once the hams are skinned, you’ll need to make a long cut from vent to head. Loosen with the knife and pull the hide down. Now turn your attention to the front legs and reverse the procedure used for skinning the back legs. Cut completely around the head and remove the hide in one piece.

To remove the head, use a heavy knife, cutting just above the ears at the first point of the backbone and across the back of the neck. Continue to cut around ears to the eyes and the point of the jawbone, which will leave the jowls in place. Don’t throw the head away, as it contains a good deal of meat once it is skinned. For now, keep it cool in a bucket of water.

Now the carcass is ready for evisceration or gutting. The carcass is cut open from the hams all the way down. A meat saw will come in handy here, as the breastbone and pelvic girdle will need to be cut in half.

Cut around the bung and pull it down. The entrails will come out with some cutting and pulling. If you kept the pig off feed before butchering, the intestines and stomach will be much easier to work with at this stage.

Cut the liver from the offal and carefully remove the gall bladder. Cut off the heart and wash it. Hang the liver on a peg through the thick end and split the thin end to promote drainage. Hang the heart by the pointed end to drain it.

If the intestines are to be used for sausage casings, turn them inside out, wash, scrape with a dull stick and soak in a weak lime water solution for 12 hours. A solution of one tablespoon of baking soda to two gallons of water will also work.

The carcass is washed with water, and the backbone split with a meat saw. You’ll see the snow-white leaf lard. Pull this out for rendering. Now it’s time for cooling the carcass, and fall is the ideal season for natural refrigeration. Ideally, the temperature should be in the 34º to 40º F range for 24 hours.

A pig consists of five major parts: ham, loin, shoulder, bacon and jowl. Miscellaneous pieces or trimmings go into the sausage pile. You’ll need a large enough surface to work on half a hog at a time.

To remove the jowl, saw at the shoulder between the third and fourth ribs. A large knife will work better than the saw once you get through the ribs. The jowl is trimmed and cut into a “bacon square” that can be used like bacon or as a flavoring ingredient in beans and other dishes.

Now remove the neck bone at the shoulder and trim off the meat. Cut off the shank above the knee joint. The shoulder can be cured or divided into a picnic shoulder and a butt. Fat on top of the butt can be trimmed for lard rendering. The lean portion is commonly known as a Boston butt.

To remove the ham, saw on a line at right angles to the hind shank to a point a couple of inches in front of the aitchbone. A knife will be needed to complete this cut. Remove the tail bone with the knife. It’s best to trim loose and small pieces of meat for sausage since they will dry up in the ham cure.

Saw the shank off at the button of the hock. To separate the loin from the belly, saw across ribs one-third of the way from the top of the backbone to the bottom of the belly. The tenderloin (the most expensive part of the pig in grocery stores) should come off with the loin.

Place the belly on the table skin side up, smooth out the wrinkles, and loosen the spareribs with a few solid whacks from a cleaver. Turn it over, loosen the neck bone at the top of the ribs and trim as close as you can.

The bacon is next. Begin at the lower edge, cut straight and remove the mammary glands. Trim the top parallel to the bottom, squaring off both ends. Take the scraps and add them to the sausage or lard piles.

That small, lean muscle underneath the backbone at the rear of the loin is the tenderloin. This primo cut is trimmed and set aside for a special meal. Trim all but a quarter inch of backfat from the loin.

The average home butcher won’t be able to cut thin “breakfast chops” with his meat saw and knives. For that you need a bandsaw. That means thick chops for dinner, but that shouldn’t lead to any complaints!

Plan ahead when butchering. You’ll need a good block of time, quality knives, sharpeners or whetstones and adequate freezer or refrigerator space for the various cuts. Don’t expect your first efforts to look as precise as what is sold at the supermarket. More importantly, your meat will taste much better and have been raised cleaner than those pretty cuts.

Free Range Pig Farming: Making Ham, Bacon, and Sausage

Tired of the bland “water added” hams that are common today? Perhaps you’d rather avoid nitrites. Why not make your own ham and bacon? One of the benefits of free range pig farming is that you’ll have access to some of the freshest meat available to make your own ham, bacon, and sausage.