#El Ghriba synagogue

Text

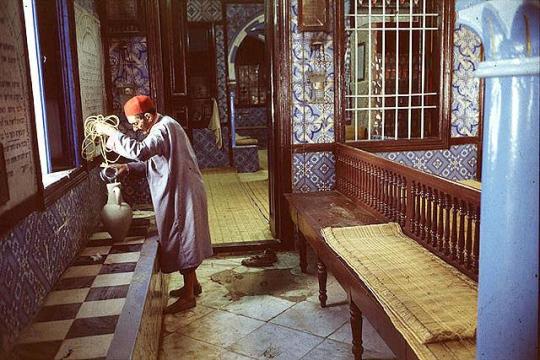

Pilgrims celebrate Lag Ba-Omer at the El Ghriba Synagogue near Er Riadh, on Djerba, Tunisia. 1970.

155 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can i just say i LOVE all the little things you share about jewish culture.I am a goy who grew up in a place with an almost non existent jewish community and i only got introduced to it much later in life.I love seeing it through your eyes and adoption, it seems so precious to you

What are the favorite things you learned ?Is there anythings you would like to share about it you havent yet ?

I've been thinking about this a lot, because you sent me this ask a very long time ago and I could never settle on one thing. As soon as I started writing up one thing, I'd think of another. In fact, I just wrote up a whole thing about the "mezinke," a popular custom at frum weddings which seems to have been adopted into Jewish culture about 130 years ago and popularized by klezmer band leaders, but which people often think is much older.

But then I deleted it, because what I really love is this:

No matter how much I learn about Jewish culture, there is always more to learn. We have been everywhere, and we have been an integral part of the culture of everywhere that we've been. Jewish culture includes Sephardic recipes and Desi customs, its DNA contains strands from every settled continent and it continues to change, to grow, and to adapt. There are synagogues from Tokyo to Tasmania, from Recife to Regensburg. The El Ghriba Synagogue in Djerba, Tunisia was built in either 586 BCE or 70 CE (depending on your source) which makes it the oldest synagogue still standing and still in use. Jewish culture is a conversation l'dor v'dor -- from generation to generation -- and if there's one constant about us, wherever we are, it's that we never stop talking about the things that matter to us.

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tunisia has largely moved on from the May 9 killing of five people at the El Ghriba synagogue on the island of Djerba by a National Guardsman. The event’s prominence on the country’s news sites has diminished and its claim on Tunisian conversation has largely been ceded to the other items competing for space at the national table.

On-air criticism of police recruitment methods by radio hosts Haythem El Mekki and Elyes Gharbi swiftly resulted in a legal complaint from the security services and, essentially, an end to discussion.

Thus far, Tunisia has steadfastly refused to publicly address the anti-Semitic nature of the attack, preferring instead to characterize it as “criminal.” However, the fact that the Jewish tourists and locals gathering to celebrate the festival of Lag B’Omer were specifically targeted by the attacker, 30-year-old National Guardsman Wissam Khazri, is hard to dispute.

After killing his colleague, Khazri donned body armor and rode 12 miles by quad bike to attack the pilgrims at the synagogue. However, beyond the arrest of four conspirators, his motivation for doing so, or details of any radicalization, remains unknown.

Responding to the murders, Germany and France characterized the attack as anti-Semitic, with Paris going even further and launching a terrorism probe into the killing of one of its citizens—a dual-national who was among the victims.

For Tunisian President Kais Saied’s government, the story was simply too messy. This year’s tourism revenues, which are vital following the uncertainty surrounding the hard-pressed country’s latest bailout from the International Monetary Fund, represent one of the few economic bright spots on a dark financial horizon. That security around the synagogue appeared to have failed—the attack was undertaken by one of the island’s supposed defenders—despite the massive expense and planning involved was also pushed to the sidelines.

However, underpinning all of this was the identity of the targeted victims and the deliberate and premeditated assault upon the Jewish community.

The Jewish presence in Tunisia reaches back almost 2,000 years. Over the centuries, through occupation by Phoenicians and Romans, conquest by Arabs, and colonization by Ottomans and the French, Tunisia’s Jews have maintained an unbroken thread linking past and present Tunisia. However, since World War II and the establishment of Israel in 1948, their numbers have dwindled. Pressure at home and opportunities overseas have reduced the population from around 100,000 in 1948 to less than 1,800 today.

Of all the Jewish communities that once dotted northern Tunisia, only that on the island of Djerba remains. The synagogue there, whose foundations are said to date back to Jerusalem’s Temple of Solomon, remains a cornerstone of not simply Tunisian Jewish identity, but Jewish identity as a whole.

The reasons for this declining population are rooted in recent history. Tunisia’s steadfast support of the Palestinian cause, a matter of profound faith for many, has embedded itself across all levels of society. From 1982 to 1985, Tunisia hosted the headquarters of the Palestinian Liberation Organization in a suburb just south of the capital, Tunis, until an Israeli air campaign essentially wiped it from the map, inspiring one of the first isolated assaults on the synagogue on Djerba by way of reprisal.

Many Tunisians are acutely aware of every injustice visited upon the Palestinian population. That, along with years of unflinching official opposition to the Israeli state, has almost certainly combined to make life in the country uncomfortable for many Tunisian Jews. By way of evidence, we only need to look to the spikes in emigration to both France and Israel that followed the Six-Day War in 1967 and the Yom Kippur War of 1973.

Whatever some may say, it is clear that what happens in the Middle East carries consequences for Tunisia’s Jews and how they’re regarded by their compatriots.

In the wake of the synagogue attack last month, one Twitter user achieved temporary notoriety after discovering that one of the victims, Aviel Hadad, was to be buried in Israel. Hadad had held dual citizenship with Israel and—in much the same way as many Muslims ask to be buried in Mecca, without opining on Saudi politics—had asked to be interred there. Nevertheless, one Tunisian blogger called for Hadad’s Tunisian family to be expelled from the country and any officials who knew of his wishes to be prosecuted.

A prominent journalist, on discovering that a victim of the attack held an Israeli passport, asked if the country was mourning Zionists. Across the country’s ubiquitous radio channels, a major source of news and information for many, conversations on Tunisia’s attitudes to Jews came to be almost exclusively couched in discussions on the Palestinian and Israeli conflict, with the fate and welfare of Tunisian citizens judged by the actions of a distant state that few had any connections with.

Unsurprisingly, the president has proven no exception. On a visit to the Tunis suburb of Ariana the weekend after the attack, Saied rejected accusations of anti-Semitism, recalling his own family’s history of offering shelter to Tunisia’s Jews during the 1942-43 Nazi occupation of the country, when Tunisia’s Jews faced extreme persecution. From there, he demonstrated little difficulty in segueing effortlessly into a discussion on Israeli attacks on Palestine. Their relevance to Tunisia’s Jews was not made clear.

“Despite the fact that most of the Jews of Tunisia have never set foot in Israel and that their homeland has been Tunisia for centuries, they are taken as scapegoats for actions committed in another part of the world,” said Joachim Lellouche, the son of Jacob Lellouche, a prominent member of the Tunisia’s Jewish community. The younger Lellouche, who grew up spending time in both France and Tunisia, told FP, “Most of the Jews in the world feel close to Israel—because of their ancestral history; that does not mean that they support the internal policy of the government.”

Lellouche, who spent his childhood shuttling between France and his father’s busy restaurant in La Goulette, a port town near Tunis, recalled the kind of prejudice his family encountered. “It’s ridiculous, but there’s this thing about Jews smelling of the dead,” he said. “Around 15, maybe 20 years ago, my father told us about a [Tunisian] man who came up and sniffed him. The thing is, that was a poor and uneducated man. Now, since the revolution, mass media and fake news, those attitudes are everywhere.”

Lellouche has seen the consequences of Tunisia’s anti-Semitism. In 2015, his father’s kosher restaurant, Mama Lily, a mainstay of cultural life in the city, closed due to anti-Semitic threats.

“Tunisia’s Jews are always held to a higher account,” Amine Snoussi, a Tunisian political analyst, said. “People always expect them to prove their loyalty to Tunisia and to reject Israel before they’ll even engage with them. No one else has to deal with that.”

“Jews, or minorities even, don’t really fit with [Saied’s] agenda,” Snoussi continued. “He doesn’t have time for them. He deals in a very utopian vision. Anything that contradicts that—such as anti-Semitism or the recent attacks on the country’s undocumented black migrants—has to be rejected and denied.”

In Snoussi’s opinion, Saied’s entire reaction to the synagogue attack has been shaped, not so much by any sense of anti-Semitism, but by his almost exclusively populist mindset. “He’s sought to frame this in terms of Palestine,” Snoussi said. “That fits with his ideas of what the country thinks, as well as the wider Arab nationalist world. He doesn’t think about Tunisia’s Jews. He doesn’t think about minorities. He doesn’t care how linking them so clearly to Israel puts them at risk.”

That attitude is causing real damage. In early May, the University of Manouba in Tunis announced it would revoke the title of professor emeritus from Habib Kazdaghli, a Muslim-born historian of Tunisia’s Jewish traditions who had attended a French conference alongside Israelis.

Hardline attitudes to Israel appear hardwired into entire strata of Tunisian society. “It’s not just me,” Kazdaghli told Foreign Policy via a translator. “It goes further. Tunisia’s wrestlers and tennis players have all been accused of normalizing relations with Israel through sporting events.

“I’ve been studying this for 25 years,” he said. “This bothers them. Every time they do this”—referring to the implicit barriers placed in the way of his research by both government and academia—“they’re saying they’re anti-Semitic without actually saying they’re anti-Semitic.”

Beyond his own academic specialism, Kazdaghli has grounds to speak with authority on the topic. He was on the bus outside El Ghriba synagogue when the May attack took place.

“Now when something happens, the state doesn’t address it,” he said. “I don’t think it’s anti-Semitism on their part. It’s more about being scared of even addressing the issue, and that’s worse.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding the History and Experience of Tunisian Jews

SONY DSC

This year’s El Ghriba pilgrimage celebration on the island of Djerba will be subdued, with festivities limited to the El Ghriba synagogue itself. This comes in the wake of the tragic events in Gaza, creating an understandably somber atmosphere.

The presence of Jews in Tunisia dates back over 2,000 years, with their population peaking at over 100,000 in the mid-20th century. Their…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Chloe Pitard

Reflection Paper

11 octobre 2023

J’ai passé des moments très agréables pendant l’excursion en Tunisie ! La cuisine, l’histoire, et les gens étaient incroyables ; je m’en souviendrai toujours. Pendant l’excursion, j’ai utilisé mon français avec beaucoup de gens. Aussi, j’ai appris la culture, la nourriture, et l’histoire des villes.

Par exemple à Djerba, j’ai vu les peintures murales et ai trouvé un petit magasin d’art. Dans le magasin, j’ai rencontré un artiste gentil. Il a expliqué en français son histoire et comment il a créé son art. Avec le sable et la peinture, il a peint les bâtiments et les paysages à Djerba. Je lui ai dit que je suis une étudiante à Tunis, alors il a comparé l’art et l’architecture de Tunis à ceux de Djerba. Il m’a dit qu’il voulait m’aider pour le français, alors il m’a donné ses cordonnées. J’ai acheté une pièce d’art parce que je n’oublierai pas sa gentillesse.

Aussi à Djerba, j’ai exploré la médina. Elle n’était pas très animée et avait beaucoup de petits magasins. En premier, nous avons mangé au restaurant. Il était près du marché de poisson, alors nous avons choisi notre poisson et le restaurant l’a cuisiné. J’ai choisi une ojja aux crevettes et c’était la meilleure ojja que j’ai mangé ! Après, nous avons visité les magasins. J’ai acheté des bijoux pour mes amis et ma famille. En français, j’ai négocié le prix et j’ai fait une bonne affaire. Les vendeurs étaient très heureux de me parler en français et en Tunisien. Par exemple, un vendeur m’a aidé pour ma prononciation. Il m’a expliqué qu’à Tunis, on prononce « qadesh », mais à Djerba, on prononce « gadesh. » J’ai trouvé intéressant que les régions prononcent les petits mots différemment.

Mon endroit préfère était le colisée d’El Djem. Ce colisée est le plus grand en Afrique et est l’un des mieux préservés. Malheureusement, pendant une dispute entre deux rois romains, un roi a détruit la moitié du colisée. Pourtant, je pense que ce monument est très impressionnant. Sa taille et son histoire sont incroyables. J’y suis monté et j’y suis restée pendant plusieurs minutes. J’aurais pu rester pour toujours.

J’aurais aimé que nous restions plus longtemps à Djerba, car j’étais impressionnée par les vieux bâtiments et par leur histoire.

Photo 2 : Cet photo est au Borj el-Kebir. Il est une forteresse par la mer. Rached a expliqué comment les gens a défendu la forteresse. Par exemple, il y avait deux portes alors il était plus facile qui leur defendre.

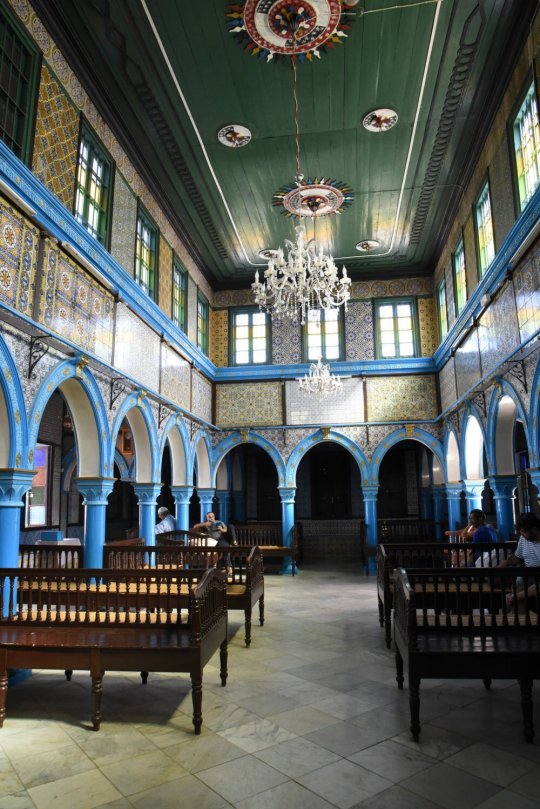

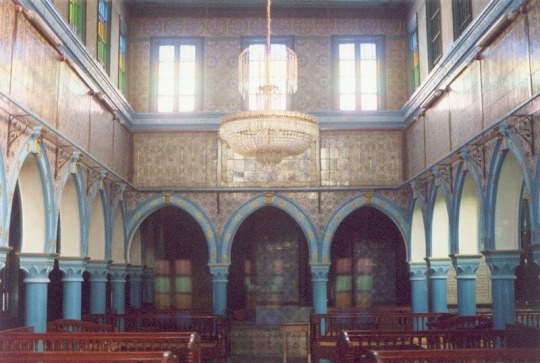

Photo 3 : Le photo montre El Ghriba Synagogue. La synagogue était très belle avec les carrelages magnifiques. A l’intérieur, il avait avec beaucoup d’histoire.

Idiomes :

Avoir le coup de foudre : love at first sight

En la bijouterie, j’ai eu le coup de foudre du bracelet vert alors je l’ai dû acheter.

Ne pas faire d’omelette sans casser des œufs : you can’t make an omelette without cracking some eggs, no pain no gain

Quand j’ai rencontré l’artiste français, il a dit que connaissance le français est difficile et tu ne peux pas d’omelette sans casser des œufs.

#tunisiablog#tunisia#language and culture#cultural learning#cultural experiences#student#Tunisian adventure

0 notes

Text

George Ashford

10/11/2023

Reflection

Traveling through Tunisia, I saw the marks of the many cultures that have found a home here throughout history. A Roman coliseum. Amazigh villages carved into the desert. A Sunni mosque made of Roman columns and a Shi'a fortress guarded by Ottoman cannons. The monumental art-deco and brutalist structures of the capital. An ancient synagogue rumored to contain stones from another, even more ancient temple that stood where Abraham obeyed and Isaac was spared. They tell a story that spans thousands of years, a story of colonization, assimilation, war, and the advent of a nation.

One part of the story begins on the island of Djerba. The Ghriba Synagogue, purportedly the oldest Jewish site in Africa, sits near the center. No one knows for certain how old it is, but legend has it that the high priests of the Temple Mount fled to Djerba after Nebuchadnezzar and the Bablylonians sacked Jerusalem, carrying a stone and a door from the First Temple to build anew. As he shows us around a traditional Amazigh house, dug two stories deep into the soft desert dirt, a light-eyed man in a baseball camp explains that his people were once Jewish. That is why they sheltered Jews during the holocaust, he says, pointing to a metal helmet from WWII hung on a stick bannister. With a few exceptions, the Amazigh are not Jewish anymore, as evidenced by the woman in hijab who serves us tea while we watch the sunset wash over the small circle of sky visible from the open pit at the center of the house, but the man is proud to tell us that they once were. He is staking a claim to Tunisia’s story, reminding us that it began before the Arabs arrived, and that his ancestors were here before Islam. Although he does not make it a point to tell us, they were here before Judaism too.

In Kairouan, conquests are layered onto one another in the very foundations of the city. As we look out over the massive cisterns that held the water for the ascendant Umayyad caliphate’s first outpost in the region, we learn that it gets its name from the Arabic word for a military caravan. The outpost was to protect the new settlers from the Amazigh, who staged a series of successful rebellions before being defeated and gradually converting to Islam. We do not have to explore Kairouan for long, however, to see that the The Umayyads were not the first conquerors to make their mark here. The columns of the majestic Great Mosque of Kairouan are carved in the Greco-Roman style, clearly repurposed from older buildings. Some of the stones in the outer wall have latin writing on them. 70 kilometers away, closer to the coast, the towering Roman amphitheater in El-Jem testifies more explicitly to the power of the empire that counted this part of North Africa among its first and hardest won territories.

After El-Jem, we stop in Mahdia. The insurgent Fatimid caliphate, tracing their lineage back to the Prophet’s daughter, founded the city as their first capital a few hundred years after the Umayyads founded Kairouan. They would go on to capture Egypt and the rest of North Africa from the ruling Abbasid dynasty, spelling the end of a united Arab empire in the Mediterranean. We walk along the parapet of a fortress looking out over bright blue ocean on three sides. We imagine seeing

ships coming over the horizon and scrambling to man the defenses, as so many must have over the centuries. Genoese, Norman, Spanish, French, and Ottoman raiders all came by sea to Mahdia, its well-fortified harbor making it a prime toehold for a long line of would-be conquerors.

The latest conqueror in that line is most visible in Tunis, where art-deco facades adorn the most prominent buildings in the city center. It is also audible in the French words and accent woven into Tunisia’s unique dialect of Arabic. Tunis also, however, tells of something new. Hulking government buildings and hotels made from the ubiquitous concrete of the late 20th century overlook Habib Bourguiba Avenue. They proclaim the sovereignty of a people that is not quite of the ancient desert tribes nor any of their conquerors. Our professor points out the site of famous protests where Tunisians proclaimed a more personal form of sovereignty, demanding political freedom and economic opportunity and getting at least the former.

Tunisia is an Arab country. Hearing the language and the call to prayer every day make that clear, and Kairouan tells the story of how it became so. It is not, however, a solely Arab country, just as the story of Kairouan is not Tunisia’s only story. Djerba, El-Jem, Tunis, Mahdia, and the Amazigh villages tell other stories about Tunisia, stories that include elements of the French story, the Jewish story, the Ottoman story, the Roman story, and the story of the Amazigh. With revolution for national, and then for personal independence as the most recent chapters, they weave together into one, rich, cohesive, Tunisian story. It has been a fascinating story to learn these past few months, and I look forward to someday knowing it in more detail.

Expressions

One of the most common Tunisian expressions is to say صحة when someone is eating, gets out of the shower, or buys new clothes. The response is يا أتك صحة. The expression literally translates just to ‘health,’ and expresses encouragement of healthy activities like eating.

ما يْحِس بِالجمْرة كان الّي يعْفِس عْليها is a less common Tunisian proverb that translates literally to ‘only he who walks on embers can feel it.’ It expresses the idea that one should not judge or criticize the struggles of someone else, since it is impossible to know what they are really going through.

Photos

أركان رومانية في جامع قيروان الأكبر

George Ashford

10/11/2023

Reflection

Traveling through Tunisia, I saw the marks of the many cultures that have found a home here throughout history. A Roman coliseum. Amazigh villages carved into the desert. A Sunni mosque made of Roman columns and a Shi'a fortress guarded by Ottoman cannons. The monumental art-deco and brutalist structures of the capital. An ancient synagogue rumored to contain stones from another, even more ancient temple that stood where Abraham obeyed and Isaac was spared. They tell a story that spans thousands of years, a story of colonization, assimilation, war, and the advent of a nation.

One part of the story begins on the island of Djerba. The Ghriba Synagogue, purportedly the oldest Jewish site in Africa, sits near the center. No one knows for certain how old it is, but legend has it that the high priests of the Temple Mount fled to Djerba after Nebuchadnezzar and the Bablylonians sacked Jerusalem, carrying a stone and a door from the First Temple to build anew. As he shows us around a traditional Amazigh house, dug two stories deep into the soft desert dirt, a light-eyed man in a baseball camp explains that his people were once Jewish. That is why they sheltered Jews during the holocaust, he says, pointing to a metal helmet from WWII hung on a stick bannister. With a few exceptions, the Amazigh are not Jewish anymore, as evidenced by the woman in hijab who serves us tea while we watch the sunset wash over the small circle of sky visible from the open pit at the center of the house, but the man is proud to tell us that they once were. He is staking a claim to Tunisia’s story, reminding us that it began before the Arabs arrived, and that his ancestors were here before Islam. Although he does not make it a point to tell us, they were here before Judaism too.

In Kairouan, conquests are layered onto one another in the very foundations of the city. As we look out over the massive cisterns that held the water for the ascendant Umayyad caliphate’s first outpost in the region, we learn that it gets its name from the Arabic word for a military caravan. The outpost was to protect the new settlers from the Amazigh, who staged a series of successful rebellions before being defeated and gradually converting to Islam. We do not have to explore Kairouan for long, however, to see that the The Umayyads were not the first conquerors to make their mark here. The columns of the majestic Great Mosque of Kairouan are carved in the Greco-Roman style, clearly repurposed from older buildings. Some of the stones in the outer wall have latin writing on them. 70 kilometers away, closer to the coast, the towering Roman amphitheater in El-Jem testifies more explicitly to the power of the empire that counted this part of North Africa among its first and hardest won territories.

After El-Jem, we stop in Mahdia. The insurgent Fatimid caliphate, tracing their lineage back to the Prophet’s daughter, founded the city as their first capital a few hundred years after the Umayyads founded Kairouan. They would go on to capture Egypt and the rest of North Africa from the ruling Abbasid dynasty, spelling the end of a united Arab empire in the Mediterranean. We walk along the parapet of a fortress looking out over bright blue ocean on three sides. We imagine seeing

ships coming over the horizon and scrambling to man the defenses, as so many must have over the centuries. Genoese, Norman, Spanish, French, and Ottoman raiders all came by sea to Mahdia, its well-fortified harbor making it a prime toehold for a long line of would-be conquerors.

The latest conqueror in that line is most visible in Tunis, where art-deco facades adorn the most prominent buildings in the city center. It is also audible in the French words and accent woven into Tunisia’s unique dialect of Arabic. Tunis also, however, tells of something new. Hulking government buildings and hotels made from the ubiquitous concrete of the late 20th century overlook Habib Bourguiba Avenue. They proclaim the sovereignty of a people that is not quite of the ancient desert tribes nor any of their conquerors. Our professor points out the site of famous protests where Tunisians proclaimed a more personal form of sovereignty, demanding political freedom and economic opportunity and getting at least the former.

Tunisia is an Arab country. Hearing the language and the call to prayer every day make that clear, and Kairouan tells the story of how it became so. It is not, however, a solely Arab country, just as the story of Kairouan is not Tunisia’s only story. Djerba, El-Jem, Tunis, Mahdia, and the Amazigh villages tell other stories about Tunisia, stories that include elements of the French story, the Jewish story, the Ottoman story, the Roman story, and the story of the Amazigh. With revolution for national, and then for personal independence as the most recent chapters, they weave together into one, rich, cohesive, Tunisian story. It has been a fascinating story to learn these past few months, and I look forward to someday knowing it in more detail.

Expressions

One of the most common Tunisian expressions is to say صحة when someone is eating, gets out of the shower, or buys new clothes. The response is يا أتك صحة. The expression literally translates just to ‘health,’ and expresses encouragement of healthy activities like eating.

ما يْحِس بِالجمْرة كان الّي يعْفِس عْليها is a less common Tunisian proverb that translates literally to ‘only he who walks on embers can feel it.’ It expresses the idea that one should not judge or criticize the struggles of someone else, since it is impossible to know what they are really going through.

Photos

أركان رومانية في جامع قيروان الأكبر

كنيس الغريبة في جربة

كنيس الغريبة في جربة

0 notes

Link

Worshippers prayed, lit candles and wrote wishes on eggs as an annual Jewish pilgrimage to Africa’s oldest synagogue got under way in Tunisia on Wednesday [May 22, 2019].

Hundreds of pilgrims converged on the Ghriba synagogue on the Mediterranean island of Djerba where one of the last Jewish communities in the Arab world lives.

They were joined by government ministers and other dignitaries to celebrate the Lag B’Omer festival.

The event, which starts 33 days after the start of the Jewish Passover festival, coincides with the Muslim holy month of Ramadan this year for the first time since 1987.

A fast-breaking meal is due to be shared by Muslims and Jews on Wednesday evening in Djerba.

“It’s not easy to organize all this while people are fasting here. They are tired, but we are as welcome as usual,” said Laura Tuil-Journo from France.

This year’s pilgrimage is the first since Rene Trabelsi, who has been co-organizing the festival for years, was appointed as Tunisia’s first Jewish cabinet minister in decades, in charge of tourism.

“This year it is packed. People now come with full confidence, especially as Mr. Trabelsi became a minister,” Tuil-Journo said.

Several hundred police officers and soldiers, backed by tanks and helicopters, have been deployed to protect pilgrims.

The community is still recovering from a suicide bombing claimed by Al-Qaeda at the synagogue in 2002 that killed 21 people.

Before that, some 8,000 pilgrims used to travel to Djerba for the annual celebration.

The number plunged afterwards but has since recovered somewhat.

Tunisia’s tourism industry was also left reeling by attacks on a museum and a tourist resort in 2015 that left dozens dead, including 59 foreigners.

This year organizers expect more than 5,000 pilgrims, including Israelis, to visit the synagogue, believed to have been founded in 586 BCE by Jews fleeing the destruction of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem.

The number of Jews in Tunisia has fallen significantly, from around 100,000 before independence from France in 1956 to an estimated 1,500 today, most of whom live in Djerba.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

📍 La synagogue de la Ghriba du Kef

📍 Ghribet el Kef

🕍 ✡️

Let me show you around <3

#tunisia#tunisie#تونس#tunisian#tunisienne#tunisia tradition#tunis#الكاف#kef#el kef#le kef#aesthetic pictures#my photography#photographs#my photos#الغريبة#synagogue#jewish#huji#hujicam#hujifilter#vintage aesthetic#hujiphoto#lockscreens#huji app#aesthetic#art#building#old building#nostalgia

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

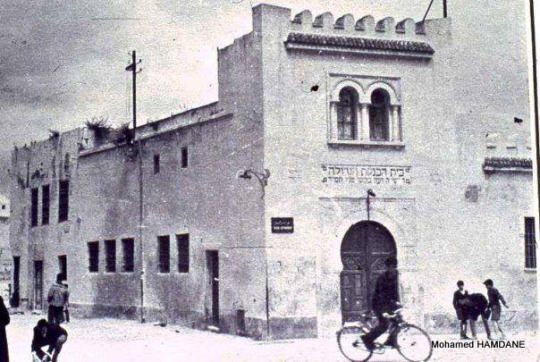

tunisian synagogues:

The now abandoned synagogue of Matmata.

the Or Torah (lit. “Torah’s light”) synagogue in Tunis’ historic jewish quarter (and previously ghetto) Hafsia/Al-Hara. it stands abandoned and desecrated.

the Mishkan Ya’akov (lit. “Yaakov/Jacob’s seat”) synagogue in Zarzis. it was built around 1900 by Zarzis’ relatively small Jewish community, and in 1982, the Torah scrolls were destroyed and the building damaged in an arson attack. it has been rebuilt by the 100 Jewish people left in Zarzis.

Le Grande Synagogue De Tunis, designed by Victor Valensi, was built in 1937. not 5 years after its completion, it was looted by the axis forces.

El Ghriba (lit. “the miraculous”) in Djerba. it was built in the late 19th century where a 6th century synagogue once stood. the Jewish community in Djerba is over 2,000 years old, and El Ghriba is believed to be built with stones from the first temple. Jews from all over Tunisia and the Tunisian diaspora pilgrim to El on lag ba’omer. last year (2020) the festivities were cancelled due to covid but this lag ba'omer there were about 7000 pilgrims.

443 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Jewish worshipper prays during a pilgrimage to the El Ghriba synagogue, Africa’s oldest one, in Djerba April 28, 2013. REUTERS/Anis Mili

501 notes

·

View notes

Text

The El Ghriba Synagogue, Djerba, Tunisia, 1995

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

According to legend, el Ghriba synagogue in Djerba, Tunisia was first built in 586 BCE or 70 CE, which would make it the oldest synagogue still standing and in continuous use in the world.

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Francisco Soler Jews Praying in the El Ghriba Synagogue (5th C CE, rebuilt 19th C CE), Djerba, Tunisia c.1920

28 notes

·

View notes