#George S. Cohan

Text

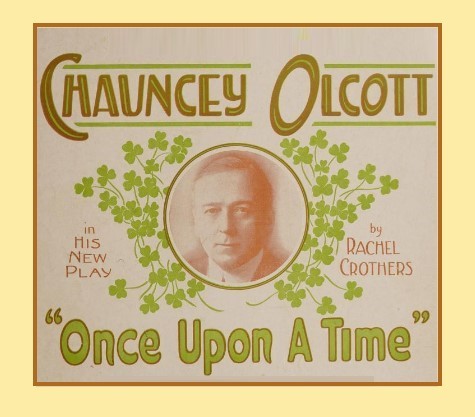

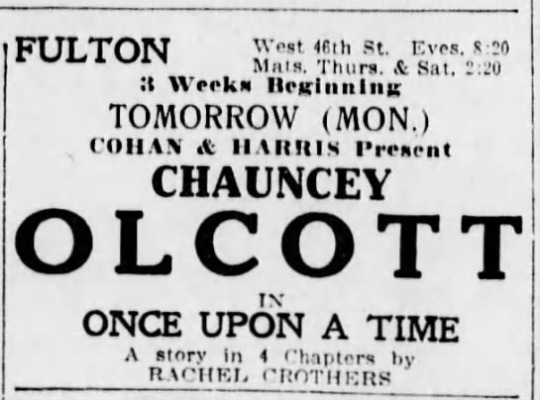

ONCE UPON A TIME

1917

Once Upon A Time is a four-act play by Rachel Crothers. It featured four songs written and performed by Chauncey Olcott. It was originally produced by Cohan and Harris starring Mr. Olcott.

The play is set in a small western town and New York City.

Terry O'Shaughnessy is jilted by his sweetheart. He Is a dreamer with the heart of a child. After years spent as a miner seeking to perfect an invention that will make him a fortune, he Is on the eve if starting for New York in search of a promoter, when the orphaned child of a forgotten brother is thrust upon him and there is no alternative but to take it along. The great invention turns into a success, but the simple Terry parts with it for a song, finding his compensation in the consciousness of having contributed to the sum of human happiness and happy In the love of the little child and the affection of his repentant sweetheart.

Chuancey Olcott (1858-1932) was an Irish-American actor, writer, composer, and lyric tenor who appeared extensively on Broadway. He was co-lyricist for the standard “When Irish Eyes Are Smilin’” and wrote both music and lyrics for “My Wild Irish Rose” in 1898. In 1913, Olcott had a number one hit singing "Too-Ra-Loo-Ra-Loo-Ral (That's an Irish Lullaby)". Olcott's life story was told in the 1947 motion picture My Wild Irish Rose starring Dennis Morgan as Olcott.

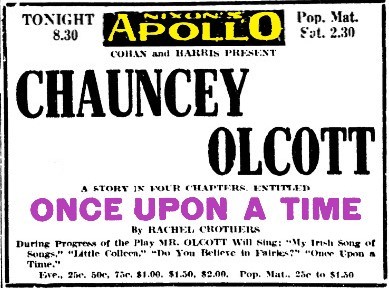

Once Upon a Time premiered in Atlantic City at Nixon’s Apollo Theatre on November 12, 1917. Olcott was a regular visitor to Atlantic City, having just been at the Apollo in March 1917 in The Heart of Paddy Whack.

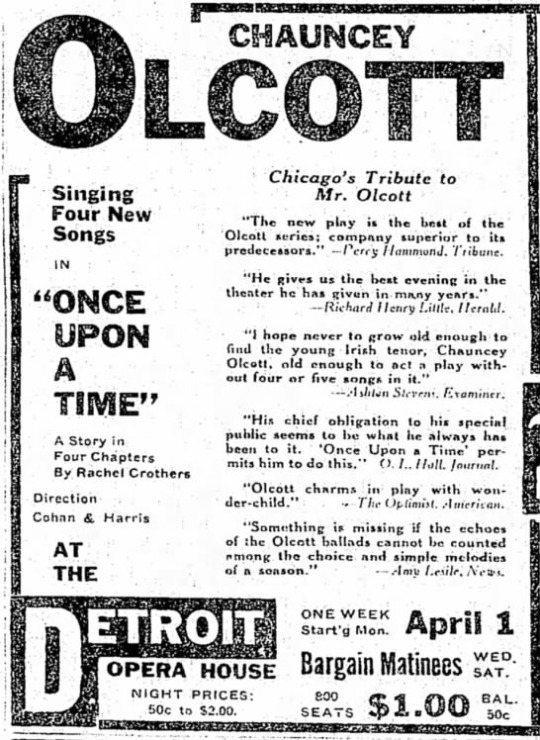

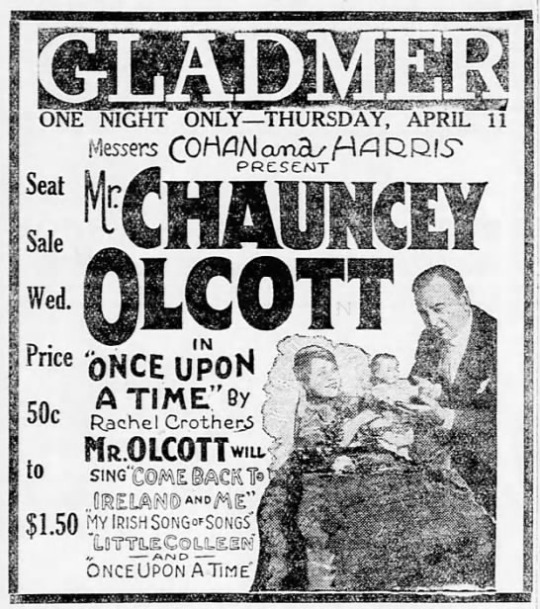

After Atlantic City, the play continued try-outs in Wilmington DE, Allentown PA, Baltimore MD, Washington DC, Brooklyn NY, New Haven CT, Philadelphia PA, Buffalo NY, Bronx NY, Newark NJ, Rochester NY, Pittsburgh PA, Chicago IL, Munster IN...

Detroit MI....

and Lansing MI. Next stop - Broadway.

Once Upon a Time opened on Broadway at the Fulton Theatre (210 West 46th Street) on April 15, 1918. It opened as a strictly limited engagement of three weeks and closed on May 11, 1918.

About the Venue: Built in April, 1911 as a dinner theatre named the Folies Bergère, it was quickly remodeled and renamed the Fulton. In 1955, it was renamed again for Helen Hayes. In 1982, it was torn down (along with five neighboring theatres) to make room for the new Marriott Hotel and Marquis Theatre.

“Rachel Crothers can write better plays than ‘Once Upon a Time’ and has written them, but it is a good job under the circumstances. Olcott's audiences make certain demands which do not help the playwright much. It is not the easiest thing in the world to provide that the star shall sing three or four times in the course of a comedy. Miss Crothers has arranged this deftly.” ~ HEYWOOD BRAUN

“A somewhat thin and old-fashioned play, but one having many moments of touching pathos and gentle humor.” ~ HARTFORD COURANT

The play returned to the road for further engagements.

In March 1920, Olcott returned to Atlantic City and the Apollo in Macushla... but that’s another blog.

#Chauncy Olcott#Once Upon A Time#Nixon's Apollo Theatre#Atlantic City#Fulton Theatre#Broadway#Broadway Play#Rachel Crothers#Irish Tenor#1917#George S. Cohan#Sam Harris

1 note

·

View note

Text

NOTHING SCREAMS INDEPENDENCE LIKE ARTILLERY

NOTHING SCREAMS INDEPENDENCE LIKE ARTILLERY

No place does the 4th of July like Boston. I’m pretty sure we think it’s our holiday. The rest of the country is a Johnny-Come-Lately. It all happened here or at least, nearby. The Declaration of Independence. The battles of Lexington and Concord. All that stuff that we are currently forgetting ever happened as we march into authoritarianism. But, I digress.

Today, we make our annual excursion…

View On WordPress

#Boston Pops#Daily prompt#entertainment#George M. Cohan#It&039;s Your Party#Jimmy Cagney#Yankee Doodle Dandy

0 notes

Photo

Yeni York'ta yahşi besteci George M. Cohan anıtı var dediler, Times Meydanı'na koştuk😊 ⬇️ https://twitter.com/aronberk/status/1638482224361230339?t=m7Y4h4hdg93POHM6K0C8ZQ&s=08 https://www.instagram.com/p/CqFmS99uKBV/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

HIGH TIMES

Out this week on digital...

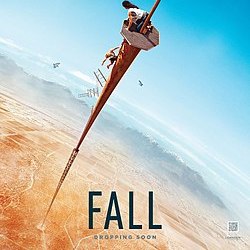

Fall--There's an old quote on the art of dramatic writing, attributed to everybody from George Abbott to George M. Cohan to Vladimir Nabokov to Stephen Spielberg: "Get your hero up a tree; throw stones at him; then get him down." The formula has rarely been followed with such dogged literalism as in this grueling but annoying thriller by the Brit Scott Mann, from a script he wrote with Jonathan Frank.

After suffering a horrible loss in a mountain climbing tragedy, Becky (Grace Caroline Currey) retreats into alcohol and isolation; her friend Hunter (Virginia Gardner) takes to performing daredevil risks and posting the videos online. A year after the disaster, in hopes of getting Becky out of her funk, Hunter talks her into joining her in climbing an insanely high old radio tower in the California desert. They don't take any food with them, because, of course, they'll be back down the rusty rickety ladder in time for lunch.

It need hardly be said that Becky and Hunter get stranded on the small platform at the top. They have no cell phone service; nobody is expecting them, and every effort they make to signal for help gets foiled. They're up there for days, getting hungrier and more desperate, and interpersonal secrets begin to emerge. Also, vultures start to strafe them, which I think is ornithologically libelous.

Heights are high on my regrettably long list of phobias, so this one was hardship duty for me. It's in that genre of "trapped in an inescapable situation" movies like 2010's Buried, or 2013's All is Lost, or Hitchcock's 1944 Lifeboat. But Fall strained both plausibility and patience for me. Really? No food? Not even a granola bar or a Slim Jim? I realize these are supposed to be reckless Gen-Z adrenalin junkies, but would they truly not tell anyone what they were doing or how long they planned to be gone?

Even if you accept this, though, the arrogance and emptiness of the project itself left me out of sympathy with our heroines. In 2018, I felt a similar exasperation with the (Oscar-winning) documentary Free Solo, about Alex Hannold's efforts to free-climb El Capitan in Yosemite. Of Hannold's almost superhuman physical prowess and mental discipline there could be no doubt, but the "because it is there" achievement seemed to me unworthy of the risk he was taking. I just kept thinking "who's going to tell his Mom?" Various of my friends and family members have looked at me with barely-concealed pitying scorn for this view and the puniness of my spirit it undoubtedly reveals.

Nonetheless, I felt doubly that way about the freakin' radio tower. Currey and Gardner are both lively and bright--too bright for how imbecilic the script makes them--so I couldn't help but hope that they would get down safe; my aggravation was with the movie itself and its contrivances. Watching it didn't feel like getting sucked into a thriller; it felt like being imposed upon, deliberately inconvenienced.

#fall movie#grace caroline currey#virginia gardner#jeffery dean morgan#mason gooding#scott mann#jonathan frank

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digital Theatre Doesn’t Need Permission To Exist

By RnD

There is one statement that has us constantly banging our heads against the wall during the Digital Theatre conversation. It is made by well meaning people on social media whenever we start talking about the industry needing to start taking Digital Theatre seriously. The statement is something like “Digital Theatre won’t go anywhere because the regional theatre and Broadway aren’t investing in it.” We end up saying something very diplomatic in response online. What we really want to say is a very Twitter-worthy “who the f@*k cares!” It doesn’t matter if the mainstream institutions aren’t incorporating Digital Theatre into their seasons (which many are by the way). Digital Theatre doesn’t need anyone’s permission to exist.

If we’ve said it once we’ve said it a million times: Digital Theatre is a movement separate from In-Person theatre. While there are several brick and mortar institutions that do create wonderful Digital Theatre (many of which have won Young-Howze Theatre Awards) they are working in two different disciplines. While we hope that all brick and mortar institutions incorporate digital programming and livestreams into their seasons, their participation is an appreciated but not necessary part of the movement. We believe that there is a future for the movement that can include companies of artists that are dispersed across the world and can create great digital works without the need for permanent buildings.

Behind every movement there is counter movement and there have been several movements that have come and gone in theatre history. Our modern regional theaters would look nothing like the melodramas of the 1800’s, George M Cohan’s Broadway of the 1940’s, or even the Musical Theatre revolutions of the 80’s. It is preposterous to think any of them asked for permission from the movement that came before to make their art. They have remounted and absorbed shows and techniques from whatever they thought would be profitable. We hope that they will adopt digital theatre but we should not look to them for permission to create the art that stirs us. Their inability to affirm our work does not make it invalid.

There is a real danger to thinking that some kind of permission is required. We keep hearing stories of faculty who are getting criticism for getting funding diverted to digital projects over in-person. We have also heard of masters and PHD candidates who are being discouraged from doing anything digital for their thesis. If we wait for some kind of permission to do the work we will be set back for years. Imagine some of the best new artists in the field plus seasoned practitioners who have found a new niche having their best work delayed for years. Imagine having to slog through so much red tape and extra steps just to get permission to do the work that you might not do it in the first place!

If you have a digital project burning in your soul do NOT be discouraged because it takes forever for brick and mortar institutions to get interested. Do not be discouraged because department heads and artistic directors can’t get on board. Move ahead and have readings and workshops. Get your email lists out and reach out to your networks. Have friends and colleagues read your script. We have seen some of the best digital theatre done in closets! Even if you have to go slowly, KEEP GOING!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

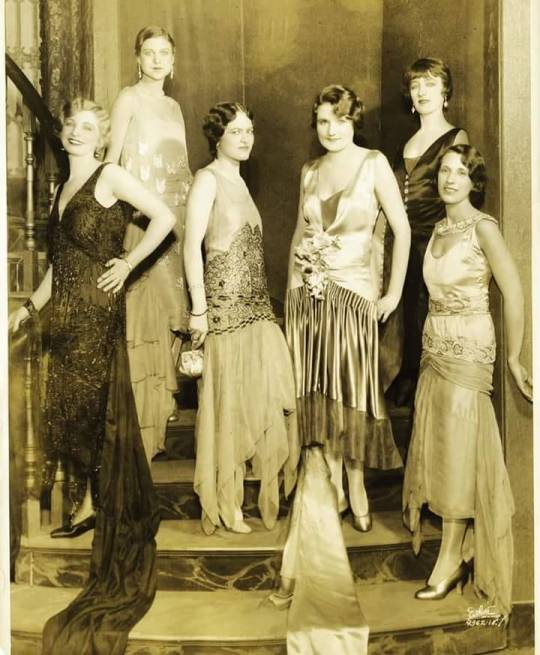

1929 The chorus from George M. Cohan’s Broadway show “Gambling”. From America in the 1920′s, FB.

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bert Williams

Bert Williams (November 12, 1874 – March 4, 1922) was a Bahamian-born American entertainer, one of the pre-eminent entertainers of the Vaudeville era and one of the most popular comedians for all audiences of his time. He is credited as being the first black man to have the leading role in a film: Darktown Jubilee in 1914.[2]

He was by far the best-selling black recording artist before 1920. In 1918, the New York Dramatic Mirror called Williams "one of the great comedians of the world."

Williams was a key figure in the development of African-American entertainment. In an age when racial inequality and stereotyping were commonplace, he became the first black American to take a lead role on the Broadway stage, and did much to push back racial barriers during his three-decade-long career. Fellow vaudevillian W. C. Fields, who appeared in productions with Williams, described him as "the funniest man I ever saw—and the saddest man I ever knew."

Williams was born in Nassau, The Bahamas, on November 12, 1874, to Frederick Williams Jr. and his wife Julia. At the age of 11, Bert permanently emigrated with his parents, moving to Florida in the United States. The family soon moved to Riverside, California, where he graduated from Riverside High School in 1892. In 1893, while still a teenager, he joined different West Coast minstrel shows, including Martin and Selig's Mastodon Minstrels in San Francisco, where he first met his future professional partner, George Walker.

He and Walker performed song-and-dance numbers, comic dialogues and skits, and humorous songs. They fell into stereotypical vaudevillian roles: originally Williams portrayed a slick conniver, while Walker played the "dumb coon" victim of Williams' schemes. But they soon discovered that they got a better reaction by switching roles and subverting expectations. The sharp-featured and slender Walker eventually developed a persona as a strutting dandy, while the stocky Williams played the languorous oaf. Despite his thickset physique, Williams was a master of body language and physical "stage business." A New York Times reviewer wrote: "He holds a face for minutes at a time, seemingly, and when he alters it, bring[s] a laugh by the least movement."

In late 1896, the pair were added to The Gold Bug, a struggling musical. The show did not survive, but Williams & Walker got good reviews, and were able to secure higher profile bookings. They headlined the Koster and Bial's vaudeville house for 36 weeks in 1896–97, where their spirited version of the cakewalk helped popularize the dance. The pair performed in burnt-cork blackface, as was customary at the time, billing themselves as "Two Real Coons" to distinguish their act from the many white minstrels also performing in blackface. Williams also made his first recordings in 1896, but none are known to survive. They participated in a "Benefit for New York's Poor" held on February 9, 1897 at the Metropolitan Opera House, their only appearance at that theater.

While playing off the "coon" formula, Williams & Walker's act and demeanor subtly undermined it as well. Camille Forbes wrote, "They called into question the possible realness of blackface performers who only emphasized their artificiality by recourse to burnt cork; after all, Williams did not really need the burnt cork to be black," despite his lighter skin complexion. He would pull on a wig full of kinky hair in order to help conceal his wavy hair. Terry Waldo also noted the layered irony in their cakewalk routine, which presented them as mainstream blacks performing a dance in a way that lampooned whites who'd mocked a black dance that originally satirized plantation whites' ostentatiously fussy mannerisms. The pair also made sure to present themselves as immaculately groomed and classily dressed in their publicity photos, which were used for advertising and on the covers of sheet music promoting their songs. In this way, they drew a contrast between their real-life comportment and the comical characters they portrayed onstage. However, this aspect of their act was ambiguous enough that some black newspapers still criticized the duo for failing to uplift the dignity of their race.

In 1899, Williams surprised his partner George Walker and his family when he announced he had recently married Charlotte ("Lottie") Thompson, a singer with whom he had worked professionally, in a very private ceremony. Lottie was a widow eight years Bert's senior. Thus, the match seemed odd to some who knew the gregarious and constantly traveling Williams, but all who knew them considered them a uniquely happy couple, and the union lasted until his death. The Williamses never had children biologically, but they adopted and reared three of Lottie's nieces. They also frequently sheltered orphans and foster children in their homes.

Williams & Walker appeared in a succession of shows, including A Senegambian Carnival, A Lucky Coon, and The Policy Players. Their stars were on the ascent, but they still faced vivid reminders of the limits placed on them by white society. In August 1900, in New York City, hysterical rumors of a white detective having been shot by a black man erupted into an uncontained riot. Unaware of the street violence, Williams & Walker left their theater after a performance and parted ways. Williams headed off in a fortunate direction, but Walker was yanked from a streetcar by a white mob and was beaten.

The duo's international success established them as the most visible black performers in the world. They hoped to parlay this renown into a new, more elaborate and costly stage production, to be shown in the top-flight theaters. Williams and Walker's management team balked at the expense of this project, then sued the pair to prevent them from securing outside investors or representation. Filings in the suit revealed that each member of the team had earned approximately $120,000 from 1902 to 1904, or $3.5 million apiece in 2019 dollars. The lawsuit was unsuccessful, and Williams and Walker accepted an offer from Hammerstein's Victoria Theatre, the premiere vaudeville house in New York. A white Southern monologist objected to the integrated bill, but the show went ahead with Williams and Walker and without the objector.

In February 1906, Abyssinia, with a score co-written by Williams, premiered at the Majestic Theater. The show, which included live camels, was another smash. Aspects of the production continued the duo's cagey steps toward greater creative pride and freedom for black performers. The nation of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) was the only African nation to remain sovereign during European colonization, repelling Italy's attempts at control in 1896. The show also included inklings of a love story, something that had never been tolerated in a black stage production before. Walker played a Kansas tourist while his wife, Aida, portrayed an Abyssinian princess. A scene between the two of them, while comic, presented Walker as a nervous suitor.

While the show was praised, many white critics were uncomfortable or uncertain about its cast's ambitions. One critic declared that audiences "do not care to see their own ways copied when they can have the real thing better done by white people," while the New York Evening Post thought the score "is at times too elaborate for them and a return to the plantation melodies would be a great improvement upon the 'grand opera' type, for which they are not suited either by temperament or by education." The Chicago Tribune remarked, disapprovingly, "there is hardly a trace of negroism in the play." George Walker was unbowed, telling the Toledo Bee, "It's all rot, this slapstick bandanna handkerchief bladder in the face act, with which negro acting is associated. It ought to die out and we are trying to kill it." Though the flashier Walker rarely had qualms about opposing the racial prejudice and limitations of the day, the more introspective and brooding Williams internalized his feelings.

In 1908, while starring in the successful Broadway production Bandanna Land, Williams and Walker were asked to appear at a charity benefit by George M. Cohan. Walter C. Kelly, a prominent monologist, protested and encouraged the other acts to withdraw from the show rather than appear alongside black performers; only two of the acts joined Kelly's boycott.

Bandanna Land continued the duo's series of hits and introduced a tour de force sketch that soon Williams made famous: his pantomime poker game. In total silence, Williams acted out a hand of poker, with only his facial expressions and body language conveying the dealer's up-and-down emotions as he considered his hand, reacted to the unseen actions of his invisible opponents, and weighed the pros and cons of raising or calling the bet. It later became a standard routine in his solo stage act, and was recorded on film by Biograph Studios in 1916.

Walker was in ill health by this point due to syphilis, which was then incurable. In January 1909 he suffered a stroke onstage while singing, and was forced to drop out of Bandanna Land the following month. The famous pair never performed in public again, and Walker died less than two years later. Walker had been the businessman and public spokesman for the duo. His absence left Williams professionally adrift.

After 16 years as half of a duo, Williams needed to reestablish himself as a solo act. In May 1909 he returned to Hammerstein's Victoria Theater and the high-class vaudeville circuit. His new act consisted of several songs, comic monologues in dialect, and a concluding dance. He received top billing and a high salary, but the White Rats of America, an organization of vaudevillians opposed to encroachments from blacks and women, intimidated the theater managers into reducing Williams' billing. The brash Walker would have resisted such an insult to his star status, but the more reserved Williams did not protest. Allies were few; big-time vaudeville managers were fearful of attracting a disproportionate number of black audience members and thus allowed only one black act per bill. Due to his ethnicity, Williams typically was forced to travel, eat and lodge separately from the rest of his fellow performers, increasing his sense of isolation following the loss of Walker.

In 1910, Booker T. Washington wrote of Williams: "He has done more for our race than I have. He has smiled his way into people's hearts; I have been obliged to fight my way." Gene Buck, who had discovered W. C. Fields in vaudeville and hired him for the Follies, wrote to a friend on the occasion of Fields' death: "Next to Bert Williams, Bill [Fields] was the greatest comic that ever lived."

Williams' stage career lagged after his final Follies appearance in 1919. His name was enough to open a show, but they had shorter, less profitable runs. In December 1921, Under the Bamboo Tree opened, to middling results. Williams still got good reviews, but the show did not. Williams developed pneumonia, but did not want to miss performances, knowing that he was the only thing keeping an otherwise moribund musical alive at the box office. However, Williams also emotionally suffered from the racial politics of the era, and did not feel fully accepted. He experienced almost chronic depression in his later years, coupled with alcoholism and insomnia.

On February 27, 1922, Williams collapsed during a performance in Detroit, Michigan, which the audience initially thought was a comic bit. Helped to his dressing room, Williams quipped, "That's a nice way to die. They was laughing when I made my last exit." He returned to New York, but his health worsened. He died at his home, 2309 Seventh Avenue in Manhattan, New York City on March 4, 1922 at the age of 47. Few had suspected that he was sick, and news of his death came as a public shock. More than 5,000 fans filed past his casket, and thousands more were turned away. A private service was held at the Masonic Lodge in Manhattan, where Williams broke his last barrier. He was the first black American to be so honored by the all-white Grand Lodge. When the Masons opened their doors for a public service, nearly 2,000 mourners of both races were admitted. Williams was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bert_Williams

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Enrico Caruso was born on February 25, 1873. He was an Italian operatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles (74) from the Italian and French repertoires that ranged from the lyric to the dramatic. One of the first major singing talents to be commercially recorded, Caruso made 247 commercially released recordings from 1902 to 1920, which made him an international popular entertainment star.

Caruso's 25-year career, stretching from 1895 to 1920, included 863 appearances at the New York Metropolitan Opera before he died at the age of 48. Thanks in part to his tremendously popular phonograph records, Caruso was one of the most famous personalities of his day, and his fame has endured to the present. He was one of the first examples of a global media celebrity. Beyond records, Caruso's name became familiar to millions through newspapers, books, magazines, and the new media technology of the 20th century: cinema, the telephone and telegraph.

Caruso toured widely both with the Metropolitan Opera touring company and on his own, giving hundreds of performances throughout Europe, and North and South America. He was a client of the noted promoter Edward Bernays, during the latter's tenure as a press agent in the United States. Beverly Sills noted in an interview: "I was able to do it with television and radio and media and all kinds of assists. The popularity that Caruso enjoyed without any of this technological assistance is astonishing."

Caruso biographers Pierre Key, Bruno Zirato and Stanley Jackson attribute Caruso's fame not only to his voice and musicianship but also to a keen business sense and an enthusiastic embrace of commercial sound recording, then in its infancy. Many opera singers of Caruso's time rejected the phonograph (or gramophone) owing to the low fidelity of early discs. Others, including Adelina Patti, Francesco Tamagno and Nellie Melba, exploited the new technology once they became aware of the financial returns that Caruso was reaping from his initial recording sessions.

Caruso made more than 260 extant recordings in America for the Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA Victor) from 1904 to 1920, and he and his heirs earned millions of dollars in royalties from the retail sales of these records. He was also heard live from the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House in 1910, when he participated in the first public radio broadcast to be transmitted in the United States.

Caruso also appeared in two motion pictures. In 1918, he played a dual role in the American silent film My Cousin for Paramount Pictures. This film included a sequence depicting him on stage performing the aria Vesti la giubba from Leoncavallo's opera Pagliacci. The following year Caruso played a character called Cosimo in another film, The Splendid Romance. Producer Jesse Lasky paid Caruso $100,000 each to appear in these two efforts but My Cousin flopped at the box office, and The Splendid Romance was apparently never released. Brief candid glimpses of Caruso offstage have been preserved in contemporary newsreel footage.

While Caruso sang at such venues as La Scala in Milan, the Royal Opera House, in London, the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, and the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, he appeared most often at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City, where he was the leading tenor for 18 consecutive seasons. It was at the Met, in 1910, that he created the role of Dick Johnson in Giacomo Puccini's La fanciulla del West.

Caruso's voice extended up to high D-flat in its prime and grew in power and weight as he grew older. At times, his voice took on a dark, almost baritonal coloration. He sang a broad spectrum of roles, ranging from lyric, to spinto, to dramatic parts, in the Italian and French repertoires. In the German repertoire, Caruso sang only two roles, Assad (in Karl Goldmark's The Queen of Sheba) and Richard Wagner's Lohengrin, both of which he performed in Italian in Buenos Aires in 1899 and 1901, respectively.

Repertoire

Caruso's operatic repertoire consisted primarily of Italian works along with a few roles in French. He also performed two German operas, Wagner's Lohengrin and Goldmark's Die Königin von Saba, singing in Italian, early in his career. Below are the first performances by Caruso, in chronological order, of each of the operas that he undertook on the stage.

World premieres are indicated with **.

L'amico Francesco (Morelli) – Teatro Nuovo, Napoli, 15 March 1895 (debut)**

Faust – Caserta, 28 March 1895

Cavalleria rusticana – Caserta, April 1895

Camoens (Musoni) – Caserta, May 1895

Rigoletto – Napoli, 21 July 1895

La traviata – Napoli, 25 August 1895

Lucia di Lammermoor – Cairo, 30 October 1895

La Gioconda – Cairo, 9 November 1895

Manon Lescaut – Cairo, 15 November 1895

I Capuleti e i Montecchi – Napoli, 7 December 1895

Malia (Francesco Paolo Frontini) – Trapani, 21 March 1896

La sonnambula – Trapani, 25 March 1896

Mariedda (Gianni Bucceri [it]) – Napoli, 23 June 1896

I puritani – Salerno, 10 September 1896

La Favorita – Salerno, 22 November 1896

A San Francisco (Sebastiani) – Salerno, 23 November 1896

Carmen – Salerno, 6 December 1896

Un Dramma in vendemmia (Fornari) – Napoli, 1 February 1897

Celeste (Marengo) – Napoli, 6 March 1897**

Il Profeta Velato (Napolitano) – Salerno, 8 April 1897

La bohème – Livorno, 14 August 1897

La Navarrese – Milano, 3 November 1897

Il Voto (Giordano) – Milano, 10 November 1897**

L'arlesiana – Milano, 27 November 1897**

Pagliacci – Milano, 31 December 1897

La bohème (Leoncavallo) – Genova, 20 January 1898

The Pearl Fishers – Genova, 3 February 1898

Hedda (Leborne) – Milano, 2 April 1898**

Mefistofele – Fiume, 4 March 1898

Sapho (Massenet) – Trento, 3 June (?) 1898

Fedora – Milano, 17 November 1898**

Iris – Buenos Aires, 22 June 1899

La regina di Saba (Goldmark) – Buenos Aires, 4 July 1899

Yupanki (Berutti)– Buenos Aires, 25 July 1899**

Aida – St. Petersburg, 3 January 1900

Un ballo in maschera – St. Petersburg, 11 January 1900

Maria di Rohan – St. Petersburg, 2 March 1900

Manon – Buenos Aires, 28 July 1900

Tosca – Treviso, 23 October 1900

Le maschere (Mascagni) – Milano, 17 January 1901**

L'elisir d'amore – Milano, 17 February 1901

Lohengrin – Buenos Aires, 7 July 1901

Germania – Milano, 11 March 1902**

Don Giovanni – London, 19 July 1902

Adriana Lecouvreur – Milano, 6 November 1902**

Lucrezia Borgia – Lisbon, 10 March 1903

Les Huguenots – New York, 3 February 1905

Martha – New York, 9 February 1906

Madama Butterfly – London, 26 May 1906

L'Africana – New York, 11 January 1907

Andrea Chénier – London, 20 July 1907

Il trovatore – New York, 26 February 1908

Armide – New York, 14 November 1910

La fanciulla del West – New York, 10 December 1910**

Julien – New York, 26 December 1914

Samson et Dalila – New York, 24 November 1916

Lodoletta – Buenos Aires, 29 July 1917

Le prophète – New York, 7 February 1918

L'amore dei tre re – New York, 14 March 1918

La forza del destino – New York, 15 November 1918

La Juive – New York, 22 November 1919

Caruso also had a repertory of more than 500 songs. They ranged from classical compositions to traditional Italian melodies and popular tunes of the day, including a few English-language titles such as George M. Cohan's "Over There", Henry Geehl's "For You Alone" and Arthur Sullivan's "The Lost Chord".

On 16 September 1920, Caruso concluded three days of recording sessions at Victor's Trinity Church studio in Camden, New Jersey. He recorded several discs, including the Domine Deus and Crucifixus from the Petite messe solennelle by Rossini. These recordings were to be his last.

Dorothy Caruso noted that her husband's health began a distinct downward spiral in late 1920 after he returned from a lengthy North American concert tour. In his biography, Enrico Caruso Jr. points to an on-stage injury suffered by Caruso as the possible trigger of his fatal illness. A falling pillar in Samson and Delilah on 3 December had hit him on the back, over the left kidney (and not on the chest as popularly reported). A few days before a performance of Pagliacci at the Met (Pierre Key says it was 4 December, the day after the Samson and Delilah injury) he suffered a chill and developed a cough and a "dull pain in his side". It appeared to be a severe episode of bronchitis. Caruso's physician, Philip Horowitz, who usually treated him for migraine headaches with a kind of primitive TENS unit, diagnosed "intercostal neuralgia" and pronounced him fit to appear on stage, although the pain continued to hinder his voice production and movements.

During a performance of L'elisir d'amore by Donizetti at the Brooklyn Academy of Music on December 11, 1920, he suffered a throat haemorrhage and the performance was canceled at the end of Act 1. Following this incident, a clearly unwell Caruso gave only three more performances at the Met, the final one being as Eléazar in Halévy's La Juive, on 24 December 1920. By Christmas Day, the pain in his side was so excruciating that he was screaming. Dorothy summoned the hotel physician, who gave Caruso some morphine and codeine and called in another doctor, Evan M. Evans. Evans brought in three other doctors and Caruso finally received a correct diagnosis: purulent pleurisy and empyema.

Caruso's health deteriorated further during the new year, lapsing into a coma and nearly dying of heart failure at one point. He experienced episodes of intense pain because of the infection and underwent seven surgical procedures to drain fluid from his chest and lungs. He slowly began to improve and he returned to Naples in May 1921 to recuperate from the most serious of the operations, during which part of a rib had been removed. According to Dorothy Caruso, he seemed to be recovering, but allowed himself to be examined by an unhygienic local doctor, and his condition worsened dramatically after that. The Bastianelli brothers, eminent medical practitioners with a clinic in Rome, recommended that his left kidney be removed. He was on his way to Rome to see them but, while staying overnight in the Vesuvio Hotel in Naples, he took an alarming turn for the worse and was given morphine to help him sleep.

Caruso died at the hotel shortly after 9:00 a.m. local time, on 2 August 1921. He was 48. The Bastianellis attributed the likely cause of death to peritonitis arising from a burst subphrenic abscess. The King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, opened the Royal Basilica of the Church of San Francesco di Paola for Caruso's funeral, which was attended by thousands of people. His embalmed body was preserved in a glass sarcophagus at Del Pianto Cemetery in Naples for mourners to view. In 1929, Dorothy Caruso had his remains sealed permanently in an ornate stone tomb.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In einer beispiellosen Charmoffensive sendet James Cagney Grüße an dem Broadway. Als George M. Cohan, Schöpfer unsterblicher Melodien wie Yankee Doodle Dandy, Schauspieler, Song-and-Dance-Man und Erfinder des patriotischen Musiktheaters, schwingt er die Fahnen, hebt die Moral, und legt einige atemberaubende Tanzschritte hin.

(x)

#Film gesehen#Yankee Doodle Dandy#James Cagney#Joan Leslie#Walter Huston#Richard Whorf#Irene Manning#Frances Langford#S. Z. Sakall#George M. Cohan#Michael Curtiz#Musical

1 note

·

View note

Text

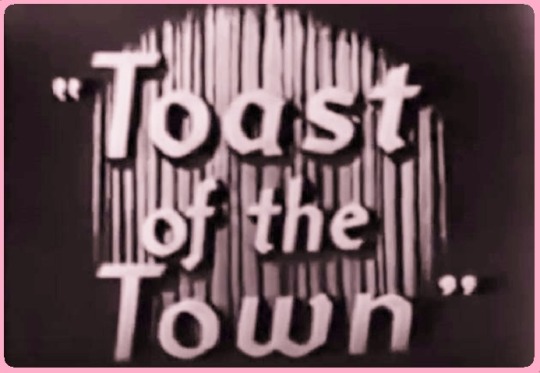

1970 ‘GEORGIE’ AWARDS

September 20, 1970

On Sunday, September 20, 1970, “The Ed Sullivan Show” presented the AGVA (American Guild of Variety Artists) Entertainer of the Year Awards. The awards are nicknamed the Georgies, after showman George M. Cohan. The award statuette was in his likeness.

This is the opening episode of “The Ed Sullivan Show’s” 23rd season. The long-running variety series premiered on June 20, 1948 with the title “Toast of the Town.” On September 25, 1955 (the start of season 9) the series was re-titled “The Ed Sullivan Show”. On February 9, 1964 the Beatles made their "Ed Sullivan" debut. The Beatles' three 1964 Sullivan appearances were among the highest rated TV programs of the 1960's. In 1967, Ed's NYC studio, Studio 50, was officially re-named The Ed Sullivan Theater. CBS cancelled the series in 1971. The final new show aired on March 28, 1971, followed by several weeks of reruns.

The Entertainer of the Year Awards were taped Caesars Palace Las Vegas. This was the first annual Georgie Awards.

THE HONOREES

Lucille Ball presents the Georgie Award for Best Female Comedy Star of the Year to Carol Burnett. From 1966 to 1971 Lucy and Carol alternated appearing on each other’s television shows. Three days before these awards aired, they both did cameo appearances on “The Dean Martin Show.” This was one of Ball’s 11 appearances on “The Ed Sullivan Show” between 1954 and 1970.

Tommy Smothers (of The Smothers Brothers) presented the Georgie Award to Flip Wilson, Best Male Comedy Star of the Year. From 1968 to 1971, Tom and Flip appeared on each other’s television shows. Like Lucy and Carol, three days before these awards aired, they both did cameo appearances on “The Dean Martin Show.”

Actor Marc Copage presents Outstanding Animal Act trophy to Tanya The Elephant. Tanya had previously appeared on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in 1967 and 1969.

Milton Berle presents an award to Radio City Music Hall. President of Radio City Music Hall James Gould accepts. In 1938, Milton Berle was featured in the film Radio City Revels. In 1998, Berle celebrated his 90th birthday on the Radio City stage. This marked Berle’s fourth appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show.”

Danny Thomas presents the Golden Georgie Award to Jimmy Durante, who is not there to accept the award. Thomas and Durante appeared on screen together more than 15 times from 1950 to 1969, including an episode of “The Danny Thomas Show” titled “Durante and Danny” in 1966.

Ed Sullivan presents an award to Bob Hope. This is Hope’s seventh time appearing on “The Ed Sullivan Show.”

PERFORMANCES

Sullivan introduces a pre-taped clip of Barbra Streisand singing "On A Clear Day" at Vegas’s International Hotel. She is named Best Female Singer of Year.

Blood Sweat and Tears perform “Lucretia Mac Evil". They are named Best Group of the Year.

Tom Jones is named Best Male Singer of the Year. He performs "Cabaret" from the musical of the same name.

Melba Moore is named Best New Young Star. She sings “I Got Love" from the musical Purlie.

The Peter Gennaro Dancers perform. They worked extensively on “The Kraft Music Hall” from 1960 to 1971.

The Flying Alexanders trapeze act performs.

#Georgie Awards#The Ed Sullivan Show#Lucille Ball#Carol Burnett#Barbra Streisand#The Flying Alexanders#1970#TV#Peter Gennaro Dancers#Melba Moore#Tom Jones#Blood Sweat and Tears#Bob Hope#Jimmy Durante#Danny Thomas#Milton Berle#Radio City Music Hall#Tanya the Elephant#Flip Wilson#Tommy Smothers#CBS#Emmett Kelly

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

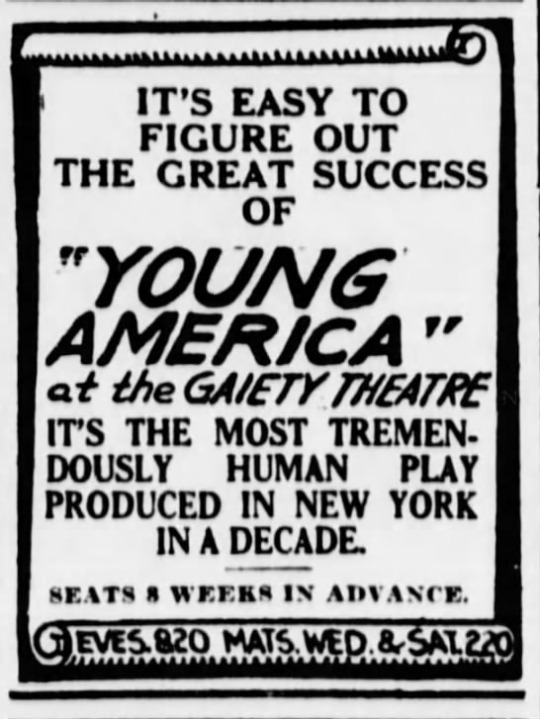

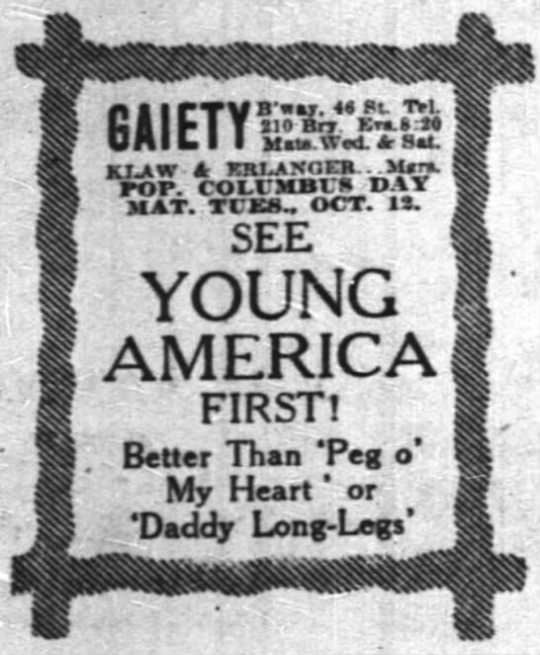

ME AND MY DOG / YOUNG AMERICA

1915

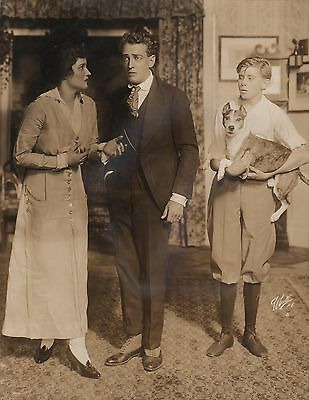

Me and My Dog (later known as Young America) is a play by Fred Ballard, suggested by Pearl Franklin’s “Mrs. Darcy” stories. It was originally produced by George S. Cohan and Sam Harris, staged by Sam Forrest. The play featured Peggy Wood, Otto Kruger, and Jasper the dog.

‘Me and My Dog’ is the story of Art Simpson and Jasper, a poor American boy and his faithful dog, who only have each other in a world which constantly imperils their liberty. Art's efforts to raise $2 for Jasper's license brings him conflict with the law, but he eventually proves his good intentions and they find a loving home with the Doray family.

The play opened at Atlantic City’s Apollo Theatre on July 12, 1915. Peggy Wood missed the Wednesday (July 14th) matinee due to her automobile breaking down in Lakewood, some 35 miles from Atlantic City. She returned by train just in time for the evening performance.

Jasper the dog wore a $10,000 diamond collar for his walks on the world-famous Boardwalk. Jasper had met Presidents Taft and Wilson.

How ‘Me and My Dog’ Became ‘Young America’

In Atlantic City, E.W. Dunn, press agent Cohen and Harris, admitted to himself that the current title was not one which would catch the public eye and the public moneys. He cast about for a proper substitution and finding none sought rest from his mental distress in the motion picture theatre across the way. In the film there is a scene in which mischievous boys tie a tin can to the tail of a dog. As this scene occurs there flashes upon the screen title 'Young America.' When the subtitle appeared Mr. Dunn jumped from his seat with the cry “That’s it!” and rushed from the movie theatre, leaving those within earshot in deep doubt as to what "it" was. But Mr. Dunn knew, and the success of the play may be attributed, partially at least, to the Interest and punch of the name, which was inspired by a film.

As Young America, Ballard’s play opened on Broadway on August 28, 1915 at the Astor Theatre (1537 Broadway at 45th Street).

About the Astor: The theatre was built in 1906. From 1912 to 1916 it was managed by George M. Cohan and Sam Harris. The Shuberts managed the theatre until 1925, when it became a movie theater. In 1972, faulty air-conditioning forced it to close for good. It was demolished in 1982 (with four other theatres) and the Marriott Hotel and Marquis Theatre was built on the site.

Two boys and their dogs: Jasper and Pinto.

JUDGE PALMER: "Hello, Washington! I suppose you were named after George Washington, weren't you?"

WASHINGTON WHITE: "No, sir. Booker."

“A new star has Broadway at his paws. The hero of 'Young America,' has nothing to say and nothing to wear, but without lines and without trousers he fairly fought his way to favor. Applause means nothing to this actor. Audiences may pound their hands to pieces before he will bow. At best it would be a bow-wow, for the hero of ‘Young America' is a dog.” ~ HEYWOOD BRAUN

“Jasper does not talk, but all the other vices of the stage are his. Dixie Taylor, the owner of the dog, assured us that Jasper was broken-hearted if an audience treated him coldly. He takes a curtain call now in ‘Young America’ and barks at one stage box, and then the other, with scrupulous impartiality.” ~ HEYWOOD BRAUN

On September 13th the play moved to the Gaiety Theatre (1547 Broadway at West 46th Street)

About the Gaiety: Built in 1908, the venue was known as a house of hits until movies took over in 1926. A brief return to legit entertainment in 1931 and 1932 proved unsuccessful. By 1943, the Gaiety had been renamed the Victoria and transformed into a movie house. In 1982, it was another one of the theatres torn down to accommodate the new Marriott Hotel and Marquis Theatre.

The Broadway production of Young America closed on November 27, 1915 with 105 performances. A tour was launched starting with the Standard Theatre on 90th Street in Manhattan. The original company appeared - even Jasper! But first...

“It is apparent by Jasper's attitude that he would gladly trade this medal off for a dog biscuit and consider that he had profited by the transaction.”

In 1918 there was a silent film version of the play starring Charles Everett Frohman (left) as Art. He was the nephew of theatrical impresario Charles Frohman and had appeared on the play’s road company.

Seventeen years later, in 1932, a sound film version was released starring Spencer Tracy and Ralph Bellamy. Producer / director Frank Borzage’s son Raymond was featured. The film is not related to the 1942 patriotic film of the same name, although both featured Jane Darwell.

The film opened at Atlantic City’s Lyric Theatre (Florida & Atlantic Avenues) on July 16, 1932.

#Young America#Me and My Dog#Atlantic City#Broadway#Broadway Play#Jasper the Dog#Boy and Dog#Broadway Theatre#Apollo Theatre#Peggy Wood#Fred Ballard#Sam Harris#George M. Cohan#Gaiety Theatre#Astor Theatre#1915#Spencer Tracy#Pearl Franklin#dogs

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Herald Square Neighborhood (No. 2)

The area around Herald Square along Broadway and 34th Street is a retail hub. The most notable attraction is the Macy's Herald Square, the flagship department store for Macy's and the largest in the United States. In 2007, Macy's, Inc. moved its corporate headquarters to that store after renaming from Federated. Macy's archrival Gimbels was also located in the neighborhood until 1984; in 1986 the building became the Manhattan Mall. Other past retailers in the area included E.J. Korvette, Stern's, and Abraham & Straus. J.C. Penney opened its first Manhattan flagship store in August 2009 at the former A&S location inside the Manhattan Mall. The square is roughly equidistant between Madison Square to the south, and Times Square to the north. Herald Square's south side borders Koreatown, at West 32nd Street.

Since 1992, Herald and Greeley Squares have been cared for by the 34th Street Partnership, a Business Improvement District (BID) operating over 31 blocks in midtown Manhattan. The 34SP provides sanitary and security services, maintains a horticultural program that includes trees, gardens, and planters, and produces events, product launches, and photo shoots. 34SP also added movable chairs, tables, and umbrellas, to the parks. In 1999, the parks were completely renovated by 34SP. Since 2008, each park has had a food kiosk operated by 'wichcraft, the highly regarded sandwich, soup, and salad purveyor owned by Tom Colicchio of Top Chef fame. In 2009, 34SP converted the parks' Automated Pay Toilets into free public facilities, a rarity in New York City.

With the introduction of "Broadway Boulevard", a 2009 project by the New York City Department of Transportation to increase pedestrian space on the segment of Broadway between 35th and 42nd Streets, the passive space provided by Herald and Greeley Squares more than doubled, radically changing the character of the area. The two blocks of Broadway between 33rd and 35th Streets were completely closed to vehicular traffic, and were made pedestrian-only with bike lanes. The parks' operators, 34SP, filled the newly pedestrianized space with chairs, tables, umbrellas, and free public programs such as chess tables, dance lessons, and exercise classes.As of April 2013, the boulevard had been redesigned. Because of the popularity of the pedestrian plaza and bike lanes in Herald and Greeley Squares, the plaza was redesigned again in 2019. Another block of Broadway between 32nd and 33rd Street was shut to vehicular and bike traffic, while 33rd Street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue was reopened, and the bike lane through Greeley Square was relocated from Broadway to Sixth Avenue.

Numerous songs refer to Herald Square, such as: George M. Cohan's song, "Give My Regards to Broadway" (1904), which includes the lyrics "remember me to Herald Square"; Andrew B. Sterling and Harry Von Tilzer's song, "Take Me Back to New York Town" (1907); Billy Joel's song, "Rosalinda's Eyes" (1978); and Freedy Johnston's song "Bad Reputation" (1994).

Herald Square is the terminus for the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, broadcast nationally by NBC-TV.

Source: Wikipedia

#Marbridge Building#Herald Towers Apartments#Midtown Manhattan#USA#Herald Sqaure Clock by Antonin Jean Carles#New York City#vacation#façade#architecture#original photography#Madison Square Garden#stone eagle#Equitable Life Assurance Society Building#exterior#detail#summer 2018#cityscape#Human Structures by Jonathan Borofsky#public art#landmark#tourist attraction

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Out of the blue I watched a new-to-me movie the other day about a retired Army Colonel who takes on corrupt politicians in his hometown in Georgia. The movie’s title is Colonel Effingham’s Raid, a 1946 comedy directed by Irving Pichel starring Charles Coburn as the title character. Colonel Effingham’s Raid has a lot going for it with charm high on its list of attributes thanks in large part to Coburn, the Georgia native with a talent for comedy and an English accent. It was then that I decided to dedicate an entry to him because I enjoy him so…and…lo and behold, this week would have been his birthday.

Charles Coburn (June 19, 1877 – August 30, 1961)

We have an embarrassment of riches in the character actor department of classic films. There are numerous memorable actors who deserve praise for bettering films simply by their appearance no matter how small a role. One of those is Charles Coburn who enjoyed a popularity many of the other character players did not. Indeed, thanks to Coburn’s 3-decades-long screen career during which he appeared in nearly 100 movies and television shows, his name recognition rivaled that of the stars whose names appeared above the title. Coburn was also highly regarded critically receiving three Academy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actor, taking home Oscar once for his delightful portrayal of Benjamin Dingle in George Stevens‘ wartime comedy, The More the Merrier (1943). More important than awards, however, was Charles Coburn’s undeniable ability to delight greatly with his talent.

Charles Douville Coburn was born in Macon, Georgia on June 19, 1877 and grew up in beautiful Savannah. He was the son of Scotch-Irish Americans Emma Louise Sprigman and Moses Douville Coburn who were not entertainers, but that didn’t stop young Charles from taking odd jobs at the local Savannah Theater starting at the age of 14. He was bitten by the entertainment industry bug early and did everything from handing out programs to being the doorman to theater manager by the age of 18. Failing to make his mark in Georgia, Charles left for New York at age 19. Although Mr. Coburn didn’t hit the big time immediately, his Broadway debut in 1901 was an inevitability as was his forming The Coburn Shakespearean Players in 1905. His partner in that endeavor was another actor, Ivah Wills, who became Mrs. Coburn in 1906. The two had six children together.

In addition to managing the Coburn Players, Charles and Ivah starred in and produced many plays throughout the decades during which the troupe traveled to college campuses across the country and appeared on Broadway. The couple met when he was playing Orlando to her Rosalind in As You Like It. They continued to work together until her death in 1937 performing Shakespeare and French and Greek dramas and comedies. In her book, Greek Tragedy on the American Stage: Ancient Drama in the Commercial Theater …, Karelisa Hartigan mentions how the Coburn Players would give over 100 performances every summer mostly outdoors. The popularity of their performances created an interest in outdoor theaters with other companies following their lead. Charles Coburn played most of the male leading parts with Ivah, billed as Mrs. Coburn, playing the female leads. The productions were often called “amateurish” by critics, but the performances were always praised. These scholarly productions likely led to Charles’ English accent despite being a Southern gentleman.

I’d be remiss not to mention that although few know her name, Ivah Wills had a long list of credits in her own right both as an actor and producer in a career that spanned 35 years. Ivah garnered positive reviews along with her husband and both were highly regarded members of the acting community. To put it in perspective, consider that George M. Cohan was among the honorary pallbearers at Ivah’s funeral.

Cobrun and Wills in The Taming of the Shrew

Ivah and Charles

After Ivah Wills’ death, Charles Coburn moved to Hollywood to start a movie career. He’d already appeared in a 1933 short film and in The People’s Enemy, a crime drama directed by Crane Wilbur. However, the roles that would cement his legacy as a screen star began in earnest in 1938 with comedic performances far removed from his classical training, but roles in which he excelled. Coburn’s best movie roles are the ones where he perfectly balances the high-brow snootiness with a touch of bumbling fool. Roger Ebert described him as a toned down Charles Laughton and that’s exactly right. Coburn paved the road to stardom at the age of 61 and became a steadfast presence that could be counted on for his comedic timing as charming old men with affected manner and accent – always with a monocle, which he removed only to eat, and sometimes chomping on a cigar. One cannot help but smile when he appears on screen.

Clarence Brown‘s Of Human Hearts (1938) offered Coburn his first substantial role alongside a first-rate cast led by Walter Huston, James Stewart and another terrific character actor, Beulah Bondi. Although that film is a Western, Coburn played a doctor, the type of professional role along with several judges, business men, a couple of “sirs,” and rich guys that he enjoyably brought to the screen throughout his career.

Charles Coburn’s memorable big screen credits are too numerous to list, but he made important contributions to such enduring classics as John Cromwell‘s Made for Each Other (1939) and Garson Kanin‘s Bachelor Mother (1939). A personal favorite of mine, Preston Sturges’ The Lady Eve (1941) wherein Coburn plays “Colonel” Harrington, father to Barbara Stanwyck’s Jean Harrington, a duo of card sharps adept at swindling the rich, would not be the same without him. The actor followed that Sturges gem with his first Oscar-nominated performance as an irascible tycoon who goes undercover as a shoe clerk at a department store to try to uncover agitators trying to form a union in Sam Wood’s The Devil and Miss Jones (1941). Starring Jean Arthur, Robert Cummings and a slew of fantastic character actors like Spring Byington, Edmund Gwenn, S. Z. Sakall, and William Demarest, you must make time to watch The Devil and Miss Jones if you’ve not seen it. It is bewitching fun.

Coburn and Jean Arthur in THE DEVIL AND MISS JONES

The 1940s served several standouts for Charles Coburn who appeared in 4 to 5 pictures a year in the early part of the decade. Of course, his Oscar-winning performance in Stevens’ World War II comedy The More the Merrier stands tall above the heap. Opposite Jean Arthur and Joel McCrea, Coburn is wonderful as the retired millionaire who finagles his way into a room during the wartime housing shortage. Coburn’s blustering but endearing manner in this film typifies the greatest gift he brought to the movies, by my estimation, and it is hard to resist. Variety agreed with me as of this movie they wrote, “A sparkling and effervescing piece of entertainment, The More the Merrier, is one of the most spontaneous farce-comedies of the wartime era. Although Jean Arthur and Joel McCrea carry the romantic interest, Charles Coburn walks off with the honors.”

Another worthy 1940s turn for Coburn was Ernst Lubitsch‘s Heaven Can Wait in 1943. Here he plays another grandfather and another millionaire with usual memorable flare alongside a stupendous cast led by Gene Tierney and Don Ameche. Once again I must mention Pichel’s Colonel Effingham’s Raid in which Coburn co-starred with Joan Bennett and William Eythe and several other veteran character actors like Donald Meek and Cora Witherspoon. This was a fun discovery.

Charles Coburn received his third Academy Award nomination for what TCM’s Robert Osborne described as a “rip-roaring performance” as a gruff but loving grandfather in the coming-of-age tale told in Victor Saville‘s The Green Years (1946). Following that performance, Coburn’s big screen appearances slowed down significantly. He had signed a contract with Columbia Pictures in 1945, which required only four films in two years. This meant that the actor had more time to return to the stage and to dedicate time to television work, which he did with gusto starting in 1950 as a premiere guest on many anthology series. Still, Coburn made a few notable pictures in the 1950s delighting audiences with a comedic millionaire performance as Sir Francis “Piggy” Beekman in Howard Hawks‘ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), a role that could have easily been creepy portrayed by anyone else. He also played against type in John Guillermin‘s murder mystery, Town on Trial (1957), which I must get my hands on.

Coburn with Jane Russell and Marilyn Monroe in a publicity shot for GENTLEMEN PREFER BLONDES

Coburn’s final screen appearance was in The Best of the Post, an anthology series adapted from stories published in the Saturday Evening Post magazine. The March 1960 episode is titled “Six Months More to Live.” That seems a somber ending to a stellar career, but one to be proud of for many reasons not the least of which is that Coburn appeared in five Oscar Best Picture nominees: Kings Row (1942), The More the Merrier (1943), Heaven Can Wait (1943), Wilson (1944) and Around the World in 80 Days (1956). Only the last of these won, but they were all improved by the Coburn brand.

At the time of his death Charles Coburn was married to Winifred Natzka who was forty-one years his junior. The two were married in 1959 and had a daughter together. The actor’s final acting role was fittingly on stage in a production of You Can’t Take It With You in Indianapolis, Indiana a week before his death at the age of eighty-four. The previous year he had been honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame located at 6268 Hollywood Boulevard. If you ever pass that address be sure to look downward at his star – it was well earned.

A Tribute to Charles Coburn Out of the blue I watched a new-to-me movie the other day about a retired Army Colonel who takes on corrupt politicians in his hometown in Georgia.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

7:40 a.m. #ny #nyc #USA “The statue of George M. Cohan gazing at what Times Square has become.” by @remages as part of the #24hourproject to raise funds for NGOs working for women´s human rights @She_Has_Hope (Uganda) @GES_Mujer (Mexico) @SacredValleyHealth (Peru) @Atena_ngo (Iran). Please show your support and help us meet our fund goal. For more information visit @24HourProject . #24hr19 #24hr19_city #newyork #streetphotography #street (at Times Square, New York City) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bx-N2LNH2Zq/?igshid=1jhbzylj2ix8k

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hawkeye Trailer Finally Brings Captain America Musical to the Stage

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

He throws a mighty shield, but can Captain America carry a showtune? In Disney+’s upcoming Hawkeye miniseries, we’re about to find out. As revealed in our first official footage of the Jeremy Renner spinoff TV show, the Marvel Cinematic Universe is still mourning the absence (and death?) of Steve Rogers… and capitalizing on it with some terrific kick-turns!

Indeed, Captain America: The Musical is now officially canon, albeit they refer to it as Rogers in the MCU. Apparently the hottest ticket on Broadway, the new show is at the center of the Hawkeye trailer, which begins with Clint Barton (Renner) finally spending quality time with his family after the “blip.” So he takes them to see Rogers just in time for Christmas. It’s currently unclear how much of the musical we’ll actually see in the finished series, but there is at least one number that’ll be staged: It stars a presumably baritone Steve belting a power ballad on a set intended to evoke the Battle of New York from the first Avengers movie. My hope is that we get a whole montage that lasts 10 minutes of this.

The inside joke is, of course, that this is not the first attempt to bring Captain America to the Great White Way. In fact, long before Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark made the wallcrawler a musical punchline, old Cap was originally going to star in a real Captain America musical in 1985. The dubious idea was the brainchild of writer Mel Mandel and composer and lyricist Norman Sachs, who intended to make a perhaps much more metaphorical story that leaned into Baby Boomer nostalgia at the height of the Reagan years. It also would’ve looked a lot different than Rogers, the faux show-within-a-show on Hawkeye.

According to a song list that leaked on Reddit a year ago, the second song of the show is about introducing Steve Rogers as a man with “A Slightly Uncommon Cold” (it’s the name of the song). Apparently Steve’s arch-nemesis for much of the show would be a midlife crisis, and finding the old American spirit while his hair grays. Hence perhaps the Act One finale song being listed as Steve and the “Lincoln High School Marching Band” belting “Fly the Flag.”

As perThe New York Times, circa 1985, the plot would’ve further involved Cap’s girlfriend—a woman running for president—being kidnapped by terrorists who commandeer the Lincoln Memorial. Yeah, there’s probably a reason the musical never actually crossed the boards.

Be that as it may, the idea of a Captain America show is still an inherently funny concept. It’s unclear how intentionally cringeworthy Hawkeye will make the idea, but after Spider-Man’s own musical mishaps on stage in the last 10 years, we imagine it’ll be pretty grueling. That said, when one looks at the staging of the song we’ve glimpsed where Rogers belts as a chorus of all the people in his life, past and present, sing above and around him, one can definitely get Hamilton vibes. It’s worth remembering that Rogers is a historical figure in the MCU, and right down to the name of the musical in this world, the citizens of the MCU have some deifying reverence for the man.

Still, I think a better musical influence on a Rogers show would be the all-time classic Yankee Doodle Dandy. Originally a 1942 movie musical starring James Cagney and directed by Casablanca’s Michael Curtiz, that World War II pick me up was also loosely based on an all-American historical figure named George M. Cohan. And to paraphrase one of his family members, how marvelous it would’ve been if any of it was true! The highly sanitized and reimagined biography of the first great song and dance man of old Broadway featured multiple patriotic bangers from the turn of the century and up through World War I, which then had new meaning at the start of WWII: “The Yankee Doodle Boy,” “Give My Regards to Broadway,” “You’re a Grand Old Flag,” “Over There.”

You could see Cap singing along for any of these old-timey flag wavers. We already have, in fact, with “The Star Spangled Man” in Captain America: The First Avenger. So go on, Marvel, give us more of those toetappers!

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

The post Hawkeye Trailer Finally Brings Captain America Musical to the Stage appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3E98pcV

0 notes

Photo

WHITE HEAT (1949)

James Cagney, Edmond O'Brien, Virginia Mayo; dir: Raoul Walsh

In the end it’s all Cagney, but the compressed punk energy he brings to White Heat is matched slug-for-slug by the direction, the writing, the acting and even Max Steiner’s music. White Heat is remorseless - a succession of switchbacks, reverses and cliffhangers that grabs you by the throat and never lets go.

Cagney’s Cody Jarrett character here amps up the gangster archetypes he pioneered in the thirties with an overlay of psychotic mother love that’s downright weird - and dangerous. John McCarty, in his collection Thrillers, rightly sees White Heat as a crucial bridge between the original Depression-era hoods and those criminals an infinitely more complex postwar world would summon up, making it no less than a “cinematic history of the crime thriller’s own evolution”.

After his 1942 Oscar winning turn as song and dance man George M. Cohan in Yankee Doodle Dandy, Cagney’s ascension seemed assured. But an ensuing string of flops with his own production company forced his return to Warners. Taking no chances on their errant star’s ‘comeback’ vehicle, the studio insisted on a star turn building on his proven Public Enemy and G-Men persona.

“The mug to end all mugs” said Cagney himself of Jarrett, his choice of terms illustrating how begrudging was his return to a skin he’d tried to shed for a decade. (Ironically just a year later he would revisit the formula in the disappointing Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye, giving such a reptilian performance as another psychotic hood that it was obvious he was so tired of the style that he could only get through by sending it up.)

The 1930s gangster archetypes seemed positively straightshooting in an inward-looking world post-Hitler and the Holocaust, and in this climate White Heat lets rip: the raw Oedipal pulp of Jarrett’s mother-dependency, the corresponding infantilism of his marriage (to a scheming Virginia Mayo, brilliantly played), the oddly avuncular quality of the Jarrett-Edmond O’Brien relationship, the brutally suppressed dysfunctional family that is the gang on the run, the brain-drilling headaches and the ruthless dispatch of anyone that gets in the way.

Rather than the oft-cited prison scene where Cody wigs out after hearing the news of his Ma, I think all these key touchstones are seen in sharpest relief in the scene where a headache cripples Jarrett in their hideaway and all the insane forces at work coalesce, not least being Ma’s advice on when to return: ”No, not yet, Son. Don't let 'em see you like that. Might give some of 'em ideas.”

An intriguing line of conjecture to this warped maternal ‘relationship’ emerges from the historical backtracking through the film’s development revealed in Velvet Light Trap (#11). In its Some Thoughts On Fifties Gangster Films, Richard Whitehall goes back to White Heat’s original story by Virginia Kellogg (who also contributed the original story for Anthony Mann’s T-Men) to excavate the original conception for Edmond O’Brien’s undercover Fed role. This was to have been no less than a father/son team of agents, cast accordingly! When this distraction was streamlined into the one (Edmond O’Brien) role, one can’t help but wonder if the germ of an idea hadn’t been planted…

(A word here for the thankless role noir stalwart Edmond O’Brien essays in White Heat. We are captivated by Cagney’s larger-than-life lunacy, but what makes all the cliffhangers and reverses work so strongly is O’Brien’s understated, calculating control, his very stolidity when it’s his being threatened that animates the audience, not the more charismatic psycho of Cagney’s bravura turn.)

Nevertheless the star gets pretty much all the best lines, and in their thoroughly black drollery (“Oh, stuffy huh? I'll give it a little air", says Jarrett to a prisoner suffocating in the trunk of a car before perforating it with .45 gauge airholes), Australian audiences may hear an echo of lead screenwriter Ivan Goff’s Aussie background.

But to come full circle, in the end it’s all Cagney. His climactic immolation seers the memory as one of cinema’s peak moments of insane brilliance – and an image that couldn’t have resonated before its forerunner at Hiroshima.

1 note

·

View note