#Great Analyst Pom-Pom

Text

Honkai: Star Rail | Great Analyst Pom-Pom

#Honkai Star Rail#Faction Introduction#Great Analyst Pom-Pom#Interastral Peace Corporation#Masked Fools#Garden of Recollection#Annihilation Gang#Xianzhou Alliance#Genius Society#The Family

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a pitch-black irony about Australians imprisoning refugees on a foreign island. [...] [I]sland prisons, granted the Orwellian-bland name ‘offshore processing’ by successive Canberra governments, have been operating on and off for years. [...] [B]ack then the queen didn’t need to ask the locals if it was okay to park a bunch of foreigners on their land. The Good Old Brits could just go ahead and steal it, then pack ne’er-do-wells such as early trades unionists aboard convict transports [...]. Conditions on arrival were normatively brutal, with one of the only creative outlets being bespoke, designer bullwhips studded with ingenious ways to flay human flesh. Back in Westminster, members of Her Majesty’s Government congratulated themselves [...]. On the one hand, Aussies never hold back in reminding British Poms of the iniquities suffered by the first convict ‘settlers’. Yet on the other, they’ll happily incarcerate thousands on new ‘fatal shores’ in Nauru and Papua New Guinea. [...]

In these more ‘civilized’ times, Australia must get agreement from the Papua New Guinea and Nauru governments to create their modern Devil’s Islands. [...] Given the relationship between what is euphemistically dubbed the ‘Offshore Processing’ system and Australia’s rambunctious electoral cycles, it’s fair to say that refugees wanting to apply for asylum in Australia are so far out of sight they’ve dropped off the radar. They’re over the horizon and far away. [...]

-------

How did it come to this?

Refugee arrivals by boat began to tick up in 1975 as refugees from Viet Nam took to the waves in the wake of the fall of Saigon in April of that year. [...] Then, in 2009, arrivals by boat broke through 5,000 people per annum for the first time since 2001. Then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd had abolished the so-called ‘Pacific Solution’ (which was anything but pacific, and anything but a solution, unless your goal was to forget about the uprooted). For a brief period until 2014 (Rudd’s replacement Julia Gillard resumed overseas processing in 2010), boat arrivals soared, with a peak year in 2013 of just over 20,000 arrivals. Once Rudd returned briefly as P.M. in June of that year, he forbade arrivals in Australian territory, and the boat turn-backs began once more under the grand-sounding Operation Sovereign Borders. [...]

In practice, this principle meant selecting and transferring some boat arrivals to regional processing centres in Papua New Guinea and Nauru. As legal analyst Elibrit Karlsen said, ‘[No advantage’] was also applied to an increasing number of asylum seekers released into the community on the mainland on bridging visas, denying them the opportunity to work and offering them only limited financial support. Significantly, these boat arrivals also remained ineligible for the grant of protection visas ‘until such time that they would have been resettled in Australia after being processed in our region’. However, the Government never clarified the number of years it envisaged these asylum seekers would wait for final resolution of their status, nor did it rule out the possibility of sending them offshore at a later date. The Government subsequently estimated that some 19,000 asylum seekers living in the community were subject to the ‘no advantage’ principle.’ [...]

-------

Aversion therapy

The situation deteriorated after the Australian High Court ruled offshore detention legal in December 2015. A woman had brought the case claiming that Australia was not fulfilling its obligations on the human treatment of asylum seekers. One five-year-old boy who had been r@ped on Nauru faced being forcibly returned to the island as a result of this case. Australia’s indefinite detention of refugees in island nations it can browbeat into compliance is a black stain on its humanitarian record. As in the Windrush case in the UK, which relates to legal migrants whose papers were destroyed in a housekeeping exercise, governments these days are happy to use the excuse of bureaucratic impartiality as a smokescreen for their lack of common humanity. They can plainly see that what is happening is inhumane, and yet they refuse to intervene, arguing that the law will decide the matter.

Yet benign neglect hadn’t been enough for the Australian government, which on July 19, 2013 had banned any asylum seeker arriving by boat from ever being resettled in Australia. Then, in 2016, after winning the previous year’s court battle, the Liberal prime minister and coalition leader Malcolm Turnbull enacted a law that forbade any asylum seeker attempting to reach its shores by boat from ever visiting the country, not even for a holiday. [...]

Overall, Australian asylum policy has been nothing short of aversion therapy for migrants. The aim can only have been to make the experience of asylum-seeking so painful and dispiriting that others are deterred. Unfortunately, this means that as on the Afghan/Pakistan border, there are stateless people stuck between polities and policies.

-------

Australia’s current prime minister, Scott Morrison, should check himself. After all, his fifth great-grandfather arrived in the stinking lower decks of a convict transport 200 years ago, having stolen nine shillings’ worth of yarn. ‘It wasn’t a great day for my fifth-great-grandfather, William Roberts,’ Mr Morrison said. [...] ‘It was January 26, 1788. It was a new beginning for him [...].’

Mr Morrison, like other Australians, just loves to trot out his own familial tale of survival. [...] Perhaps the prime minister should listen to a more contemporary take, this time by Rohingya refugee and writer Ziaur Rachman:

People typically lock a door, latch the grill [...] to keep safe. Others like us, the Rohingya, have to take a perilous journey to seek safety. This is not a story just about my family. It is the story of thousands of Rohingya families as well as others like us who have made the same desperate journey filled with unknown dangers that threaten our very lives. Just think for a moment about how desperate someone has to be to take such a risk in search of protection. [...] I also know how the world treats me. It is my sincere prayer that no one else is born a refugee, displaced with our entire lives on constant pause as we seek asylum wherever we may.

-------

John Clamp. “Fatal Shore, the Sequel: the Fate of Australia’s Refugees.” CounterPunch. 25 December 2020.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Engineering Plastic Market Opportunities, Challenges, Forecast and Strategies to 2026

The recent research, Engineering Plastic market enables stakeholders, field marketing executives and business owners get one step ahead by giving them a better understanding of their immediate competitors for the forecast period, 2019 to 2026. Most importantly, the study empowers product owners to recognize the primary market they are expected to serve. To help companies and individuals operating in the Engineering Plastic market ensure they have access to commensurate resources in a particular location the research, assess the size that they can realistically target and tap.

Request For Free PDF Sample Of This Research Report At: https://www.reportsanddata.com/sample-enquiry-form/1851

The global engineering plastics market is forecast to reach USD 138.59 Billion by 2026, according to a new report by Reports and Data. The market is rising rapidly in the global market due to the increase in high demand for engineering plastics in various highly productive applications. These plastics offer transparency, self-lubrication, and economy in fabricating and decorating with almost the same durability and toughness when compared to metals.

Key participants include BASF SE, Dowdupont, LG Chem Ltd., Asahi Kasei Corporation, Mitsubishi Engineering-Plastics Corporation, Polyplastics Co. Ltd, Royal DSM, Trinseo, Evonik Industries AG, LANXESS.

Type Outlook (Revenue, USD Billion; 2016-2026)

Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS)

Nylons

Polyamides (PA)

Polybutylene Terephthalate (PBT)

Polycarbonates (PC)

Polyethers

Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET)

Polyimides (PI)

Polyoxymethylene (POM)

Polyphenylenes

Polysulphone (PSU)

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)

Performance Parameter Outlook (Revenue, USD Billion; 2016-2026)

High Performance

Low Performance

Applications of Plastic Outlook (Revenue, USD Billion; 2016-2026)

Packaging

Automotive

Electronics & Electrical Components

Construction

Machinery

Consumer Goods

Medical Products

Others

Read Full Press Release:

The report charts the future of the Engineering Plastic market for the forecast period, 2019 to 2026. The perfect balance of information on various topics including the sudden upswing in spending power, end-use, distribution channels and others add great value to this literature. A collaboration of charts, graphics images and tables offers more clarity on the overall study. Researchers behind the report explore why customers are purchasing products and services from immediate competitors.

There are chapters to cover the vital aspects of the Global Engineering Plastic Market.

· Chapter 1 covers the Engineering Plastic Introduction, product scope, market overview, market opportunities, market risk, market driving force;

· Chapter 2 talks about the top manufacturers and analyses their sales, revenue and pricing decisions for the duration 2018 and 2019;

· Chapter 3 displays the competitive nature of the market by discussing the competition among the top manufacturers. It dissects the market using sales, revenue and market share data for 2016 and 2017;

· Chapter 4, shows the global market by regions and the proportionate size of each market region based on sales, revenue and market share of Engineering Plastic, for the period 2019- 2026;

· Continue...

To identify the key trends in the industry, click on the link below: https://www.reportsanddata.com/press-release/global-engineering-plastics-market

About Reports and Data

Reports and Data is a market research and consulting company that provides syndicated research reports, customized research reports, and consulting services. Our solutions purely focus on your purpose to locate, target and analyze consumer behavior shifts across demographics, across industries and help client’s make a smarter business decision. We offer market intelligence studies ensuring relevant and fact-based research across a multiple industries including Healthcare, Technology, Chemicals, Power, and Energy. We consistently update our research offerings to ensure our clients are aware about the latest trends existent in the market. Reports and Data has a strong base of experienced analysts from varied areas of expertise.

Contact Us:

John Watson

Head of Business Development

Reports And Data | Web: www.reportsanddata.com

Direct Line: +1-800-819-3052

E-mail: [email protected]

1 note

·

View note

Photo

NCIS: Los Angeles Season Nine Rewatch: "Mountebank"

The basics: A dead stockbroker with connections to a Russian crime lord has Sam going undercover as the broker's firm. Callen is out of the mix as one of his old aliases is the victim of identity theft.

Written by: Jordana Lewis Jaffe wrote or co-wrote “Honor”, “Patriot Acts”, “Dead Body Politic”, “Paper Soldiers”, “Unwritten Rule”, “Big Brother”, “Iron Curtain Rising”, “Exposure”, “Savior Faire”, “Beacon”, “Defectors”, “Exchange Rate”, “Black Market”, “Payback” and "Battle Scars".

Directed by: Terrence O’Hara, who directed “The Only Easy Day”, “Brimstone”, “The Bank Job”, “Borderline”, “Tin Soldiers”, “The Job”, “Backstopped”, “Crimeleon”, “Blye, K.” Part Two, “San Voir” Part Two, “End Game”, “Paper Soldiers”, “Descent”, “Ascension”, “Fish Out of Water”, “Blaze of Glory”, “Command and Control” (episode 150), “Matryoshka” Part Two, “Belly of the Beast” and "Payback".

Guest stars of note: Vyto Ruginis returns from season seven's "Glasnost" as Arkady Kolcheck Tembi Locke as Leigha Winters, Costas Mandylor as Abram Sokolov (brother Louis was serial killer Lucas Maragos in season two's "Little Angels), Uriah Shelton as Finn, Svetlana Efremova as Vladlena Sokolov, Jon Lindstrom as Phillip Nelson, Presilah Nunez as NCIS Analyst Dana Hill, Amy Stewart as Jen, Dan Southworth as Alika Hatch, Rich Ting as Keith, Mark Bloom as Victor and Americus Abesamis as Tomo.

Our heroes: Start another episode that gets wrapped up down the road. Plus, Arkady returns!

What important things did we learn about:

Callen: Victim of alias identity theft..

Sam: Really showing his financial wizardry this season.

Kensi: Arkady likes her more than Anna.

Deeks: Arkady does not care for him at all.

Eric: Needs two seconds to break into a finance firm's computers.

Nell: Looking to see how Callen was a victim of alias identity theft.

Mosley: Pulled Callen from the case because he was the victim of alias identity theft.

Hetty: Being sought in Hawaii by a friend of Sam's.

What not so important things did we learn about:

Callen: Finds a not so trusty ward (like Robin to Batman, which CO'D would know about).

Sam: Reading the Wall Street Journal since he was 12.

Kensi: Bringer of baked goods.

Deeks: Enjoying Arkady's bling.

Eric: Would not let Dexter Hughes date his sister if he had a sister.

Nell: Takes out a guy with a pool cue for stealing Callen’s alias and running.

Mosley: Working out of the armory.

Hetty: Not in the episode.

Who's down with OTP: Kensi and Deeks go underground clubbing with Arkady.

Who's down with BrOTP: Callen and Sam are split up by Mosley for most of the case but are working together to find Hetty. Deeks found a shared love of inappropriate male jewelry with Arkady.

Any pressing need for Harm and Mac: Navy reservist Phillip Nelson doesn't survive the teaser.

Today in Harley: Crosstalk in Ops to start the episode on a down note but backing up Sam ably in the field works. She also learns a bit about Sam and his non-bluffing math skills. Catches Callen trying to sneak up on her. Gets Sokolov with the overwatch spray after worrying Deeks jinxed the operation. Good Harley day.

Fashion review: Dark blue button down shirt for Callen (Callen's shirt game has improved over the last two seasons or so). The brown henley makes an appearance for Sam. Kensi is in her white and dark blue stripped tee with a scoop neck. Medium blue v-neck tee for Deeks. Green plaid short-sleeve shirt over a pink tee-shirt for Eric. Grey and white sweater-jacket over a black pinstriped dress for Nell. Midnight blue dress for Mosley (much better look that the suits from the prior episodes and the jumper). Grey pullover top and burgundy suede jacket (fantastic!) for Hidoko.

Music: "Everybody'sTalkin'" by Harry Nillson opens the episode (great song choice). "(Loose Booty) Isa Real Thing" by Everyday People is playing when Kensi and Deeks visit Arkady at home. "Gimme You" by Pom Poms plays as Kensi, Deeks and Arkady arrive at the club.

Any notable cut scene: One short scene and really not all that notable. Mosley arrives in Ops looking for an update from Eric and Nell. They don't have one. And Callen hasn't called in. 36-seconds of nothing.

Quote: Mosley: "Sam, I want you to go in."

Callen: "Yeah, we usually decide as a team which one of us is gonna go undercover."

Mosley: "'Usually' being the operative word. There's a new sheriff, remember?"

Callen: "You make it hard not to."

Anything else: On a winding Mullholland Drive in Los Angeles, a driver is chatting on his cell with a second man. The driver is also trying to get a TicTac while discussing business. The non-driver is looking to visit someplace called Mountebank. He insists Phillip – the driver – take him to that "lovely little town." Phillip the driver dropped his Purell as he is trying to drive, eat a TicTac, talk business with the guy who wants to go to Mountebank and clean up his Purell bottle. A near miss with an oncoming car has Phillip pullover to a mid-mountain off road area. As Phillip sits in his vehicle, a Jeep smashes into Phillip's driver's side.

The call is being monitored by outsiders who hear the accident.

Just inside the doors to the office, Callen is waiting for Nell. She is worried he's "stalking" her. Callen is just worried – someone opened up a credit card in his name. Nell wonders if it is Anna but Callen assures her that he and Anna are not at the credit card sharing point in their relationship. And it wasn't his name – it was Dexter's. Nell is not a fan of the Dexter alias – he is the picture of white privilege. Callen thinks it could be just routine identity theft but with the security breach around Sam that caused Michelle's death, it needs to be checked out.

Eric arrives. Callen asks Eric his opinion of Dexter Hughes – his alias. Eric is not a fan, wouldn’t let his sister (if he had one) date Dexter and would say that to Dexter's face. Callen reminds Eric that he and Dexter share a face. Eric backs down but tells Callen and Nell they have a case.

Up in Ops, Callen learns Kensi and Deeks are already in the field. A Joint Terrorist Task Force is working just a few blocks from their house. Eric, Nell and Hidoko sort of talk over each other to start the briefing. After not coming to a decision about who should go first, Sam just wants someone to start. Hidoko does. The JTTF heard the conversations in the car. Phillip is Phillip Nelson, the CEO of a financial firm. The other man was Abram Sokolov, a Russian oligarch who has been hit with financial sanctions by the US Government.

Hidoko plays the conversation. Callen and Sam seem confused. Nell wonders if Mountebank is a Swiss town. Sam isn't sure – Sokolov operates with protection from Putin. He is a skilled drug smuggler and arms dealer. NCIS is on the case because Nelson is a Navy Reservist. Callen and Sam are off to see the car wreck.

Kensi and Deeks are with the JTTF. Mountebank is code but nobody knows what it means. Abram Sokolov is involved with a number of JTTF conversations. He talks to a lot of different people all day long – he rarely sleeps. He also likes the ponies.

The area where Phillip Nelson's car was hit has no traffic cameras. There is no way to ID the hit and run driver. Sam looks at the tire marks – there are no skid marks. The driver didn't stop when he or she saw they were going to hit Nelson. They also hit Nelson while he was on the phone with Sokolov – proof of death. Sam thinks Callen's Dexter Hughes ID runs in the same circles as Phillip Nelson. The stolen ID could be a way to distract Callen – look what happened the last time the team was distracted.

Eric calls Callen but Mosley takes his little ear piece. She wants to talk to Callen. She wants Sam to go in undercover at Nelson's firm and get all of Sokolov's account information. Callen says the team usually decides who goes in undercover. Mosley points out the word usually and then reminds the men that there is a new sheriff in town.

Nell arrives with the news that the traders at Nelson's firm are beginning to short the market. The market could crash. The firm is betting big – they know something. Mosley wants them to find out what the firm knows and stop it.

Callen and Sam return to the office. Sam has a friend named Hatch working at Pearl Harbor who is looking for Hetty. If she is in Hawaii, Hatch will find her. Callen is worried that Hetty will be upset if she thinks the team is spying on her. Sam promises Hatch will be discreet.

Callen and Sam join Kensi, Deeks and Nell in the bullpen. Sam wants to know what he's walking into. Nell explains that Phillip Nelson's firm, West Valley Venue, does what big financial firms like JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs do but do it with much smaller client base and do it in Los Angeles, which is not a financial capital like New York. Senior VP and Managing Director Leigha Winters took over Nelson's position an hour after news of his death was made public. "Money never sleeps," according to Sam. Sam will interview with a number of West Valley's executives before meeting with Winters. Until this morning they were not looking to hire but Sam's faux resume as Trevor Ward with "a very persuasive cover letter" impressed. Callen is worried about Sam going into such a major financial gig but Sam knows his stuff – even started reading the Wall Street Journal at age 12.

Mosley arrives. Hidoko is going with Sam on Overwatch. She's learned about Callen's alias having his ID stolen. Callen shoots Nell a snotty look – hey, she's not the one who stole your identity. Sam is fine having Callen as back-up but Mosley is looking out for both of them. Hidoko goes.

Mosley pulls Callen into the armory. She asks if he truly believes his comprised alias poses no threat to the case. Callen says he's takes every precaution. She tells him it is not an answer. He replies he doesn't have an answer but he working the case with both eyes opened as is the rest of the team. Until Callen can secure his alias, though she's like to have Callen backing up Sam, he's not in the field.

A very annoyed Callen goes to Ops to see Nell. He demands to know why she told Mosley. She did not tell Mosley. When he wants to know how Mosley knew, Nell asks how did Hetty know things? How did Granger? "I promise you it wasn't me." Nell find an apartment rented to Dexter Hughes. Callen leaves to check it out without apologizing. Nell says to herself, since Callen is gone, she's just doing what she does.

Kensi and Deeks visit with Mosley in the armory. She's cleaning her rather pricy guns. Kensi and Deeks explain they know a big time Russian guy who could help the case, big time. Mosley wants to know if the big time Russian guy could compromise the case. "Big time," Deeks replies. But there is a slight chance he could help the case. The big time Russian guy is a problem but he's also a "charming bastard" especially to "those people on the wrong side of the law."

Mosley knows of Arkady. She is concerned about his connection to Callen and to Callen's connection with Anna. Deeks assures Mosley that neither he or Kensi have a romantic relationship with Arkady, Anna and they don't plan on bringing Callen with them to see Arkady. Mosley is on board.

Callen goes through a series of interviews – all quite entertaining. A finance bro, the woman who has to deal with the finance bro, a spreadsheet whiz with his financial model all talk to Sam before Leigha Winters. Hidoko on comms wants to know how much Sam truly understands about spreadsheet whiz's model. He assures he was not bluffing.

Callen breaks in to his alias' rented apartment. It could be Callen's place. No furniture, a futon mattress on the floor.

Leigha Winters tells Sam the staff is impressed with him. She wants to know why Sam's Trevor wants to join the firm. Trevor explains he thought about opening his own place but decided he needed a partner. He saw that West Valley was shorting the market – they're not afraid to take big chances. He's the man to take big chances with the firm.

Kensi and Deeks go to Arkady's. He's offended they're knocking on his door before 8AM on a Sunday. It is after 11AM on Monday, Deeks tells him. Arkady won't deal with them until he has breakfast. Kensi has pastries. He won't talk until he has his coffee. Since it is transitional weather, Deeks brought both iced and hot coffee. Iced coffee it is for Arkady.

Arkady has three young women in bikinis, poolside. He orders them to go inside and play ping-pong. He tells Kensi and Deeks they are his nieces. Kensi asks about Abram Sokolov. Arkady tells Kensi how much he likes her – how he wishes she was his daughter and not Anna sometimes, "but please don't tell her." As for Deeks, "I care less so for you," according to Arkady. But he is concerned enough to share his Sokolov rule – stay as far away from him as you can. He prefers at least one continent. When he learns that Sokolov is not only in the US but NCIS is working to take him down, Arkady announces "you guys are in big trouble."

Sam meets with finance bro. Finance bro is going to keep busy to not deal with Phillip's death. Sam asks about foreign transaction. The company uses them to keep up with big guys. A few folks are going out for lunch but Sam's Trevor is staying behind to catch up. When finance bro leaves, Sam with Eric's help gets into finance bro's computer.

Arkady's bedroom is everything you'd think it would be. He has a large jewelry collection that Deeks is enjoying. Deeks wants a big gold chain with a diamond encrusted "D" and a "sexy little pinky ring." Arkady tells Kensi and Deeks he's does his best thinking in the shower and appears in a the most Arkady towels ever (little pom poms on them and everything). Kensi and Deeks are mortified. Deeks can see his nipples. Arkady wants to bring them to Sokolov's sister Vladlena.

Callen and Nell update each other on Sam's status (Nell) and the empty apartment (Callen). Callen found a receipt from a Santa Monica bar in the apartment's trash. Nell thinks someone is going to a lot of trouble to get Callen's attention.

Leigha chides Sam about not going to lunch with the team. He's ready for Taco Tuesday after Macrobiotic Monday. She also asks about his passport. There is a business meeting in Nicaragua and she wants him there.

Arkady takes Kensi and Deeks to a private club. The mountain of a man acting as a doorman, Timo, is friendly with Arkady. He lets them in, reminding them of the house rules. Arkady introduces Kensi and Deeks to Vladlena who, after he gives her a hefty stack of cash, insists her guests do a shot. Arkady is all in, Kensi and Deeks want to ask questions first. Vladlena shows them her weapon – Kensi and Deeks could not enter the club with theirs – so it is shots for everyone. "Oh, that's not good," according to Deeks.

Callen tries and fails to sneak up on Hidoko. She doesn't like it. Hidoko also fills Callen in on Sam's trip to Nicaragua.

Deeks is winning big at Vladlena's tables. He's got a huge stack of chips and a nice bit of Arkady's jewelry. Vladlena dismisses the others at the table. Alone with Kensi, Deeks and Arkady, she tells them she tried to give Abram, "the little snot", away as a baby. She regrets failing. The last man to ask about her brother, Vladlena says, wound up getting a bath in acid. Despite "terrifying head's up", Deeks asks about Nicaragua. Vladlena says it likely has to do with his obsession with the ponies. Nicaragua is a great place for horses and "because he can get away with whatever he wants there." She feels sorry for Sam visiting with Abram in Nicaragua.

Sam gets Sokolov's account info and figures out what Nelson was doing – mirror trading to launder Sokolov’s money. Mountebank is the mirror trading. Sam wants to find out what Sokolov is doing with the money. Nell calls Callen – she found Dexter Hughes. Callen tells her to bring her gun, she's going into the field with him.

At Vladlena's club, Deeks is arm-wrestling Timo. Deeks wins and winds up with Vladlena's necklace. At some point, Arkady lost his shirt -Timo is wearing it. Arkady and Timo are arm-wrestling. Vladlena explains that Abram found some dirt on Phillip Nelson and forced him to work for him. When Phillip said no to some transactions, that was the beginning of the end for Phillip. And now Abram has dirt on Leigha Winters. Kensi and Deeks need to get to Leigha Winters. Deeks returns Vladlena's necklace to thank her for her cooperation. Arkady presents Deeks with an invoice for his services.

Callen walks into a Santa Monica bar. Nell is playing pool. He tells the bartender he's looking for Dexter Hughes. The bartender points to a young guy in a baseball cap at the bar. The young guy runs out of the bar through the kitchen. Callen chases him with Nell going out the front door with the pool stick. She takes down fake Dexter Hughes with the pool stick. Nell gets a text message. Kensi and Deeks brought Leigha Winters to the boat shed. Callen brings not-Dexter Hughes there as well. Deeks thinks it is bring your kid to work day as Callen marches his charge to the upstairs interrogation room.

Kensi asks about Callen's "new little buddy". Deeks respects that a kid stole Callen's alias. Callen is a little impressed too but wants to know if the kid is involved with the case. Callen asks what Leigha Winters has told them. Nothing, according to Deeks, who is wearing all of Arkady's jewelry. Callen wants to know what Deeks did to Arkady. "Bling" is Deeks's answer.

Callen talks to Winters in interrogation. She knows she wouldn't be at the boat shed if NCIS didn't know what she was doing. Callen shows her a photo of not-Dexter Hughes. Winters has no idea who he is. Callen asks if the others at the firm know about Sokolov. She didn't know about Sokolov until a week ago. The staff thinks the mirror trades are for an oil company.

Winters doesn't have time to waste with Callen. She is supposed to meet with Sokolov in an hour. She has some of his money – money he will give the Ukrainians to fight the Russians, a war they can never win. The money would buy American weapons with the idea of getting the US dragged into the Russian conflict.

Callen and Mosley meet. They both agree Sokolov is worth more to them alive and thinking he's a free man than dead. Callen will lead the team – with Sam staying at the bank in case the plan fails – to take down Sokolov's deal. Hidoko will sub for Sam.

The team follows Winters to a warehouse. Deeks thinks everything will be fine -he's wearing his lucky chain (OK, Arkady's unlucky chain). Hidoko thinks Deeks jinxed them. In the warehouse, boxes of alleged sunblock are being prepared to transport the money. He is joking about the money. Winters wants to know why she's there. Sokolov doesn't trust her.

That's a signal for Deeks to distract everyone. He does. Nobody yells "federal agent" but Callen, Kensi and Deeks start firing at Sokolov's men. Leigha Winters drags Sokolov to safety. Kensi follows. In the street, Winters and Sokolov run into a person in a hoodie. The hoodie person is Hidoko and she sprays him with the Overwatch spray from season two (nice use of show history!). Kensi is up in a sniper's nest waiting for Winters and Sokolov. As Winters and Sokolov drive off, Ops starts to track Sokolov with the spray.

Mosley congratulates the team as they pack up at the end of the day. NCIS has recovered all the laundered money. No guns for Ukrainians and Sokolov thinks Leigha Winters is on his side. Deeks presents Mosley with Arkady's invoice. It is on a red cocktail napkin. And sticky. Callen mentions to Mosley that "Hidoko took names today." Mosley knows – she trained her.

In the boat shed, Sam is talking to his buddy Hatch from Pearl Harbor when Callen arrives. Hetty's boat is still in the Hanalei Bay marina. It has been there since September 6th (the episode aired October 29th). It has been abandoned on the island. Hetty never set foot on the shore. Callen tries to explain Hetty's trade craft but Hatch explains that no tiny white woman would move on the Island without his people being aware of her.

Sam asks where could she be. Hatch thinks she went with a smuggler named Tilo Iona. There was a rumor that a "Menehune" was on one of his boats. "Menehune" a Hawaiian phrase – a Hawaiian leprechaun. Sam ends the call. Callen wants to look into Iona but has something else to do first.

Callen goes upstairs to see not-Dexter. Callen asks if his young charge is 18. He is. Callen is relieved, fewer government agencies involved. Callen asks about Abram Sokolov, Leigha Winters and Grisha Callen. The kid does not know any of these people. Callen asks about the apartment. The kid admits to that – he needed a place to live. Callen quickly figures out the kid was from one of his old foster homes. There is a hole in one of the walls – Callen made it. Callen is fine with the kid keeping the apartment but he can't use Dexter's name again. Or the credit cards. Callen sees potential in the kid. Callen wants the kid to call him if he needs help. The kid introduces himself as Matt but quickly admits his name is Finn.

And Microsoft gets its credit. Yay Microsoft!

What head canon can be formed from here: Callen finds a Mini-Me. Out on the town with Arkady.

Episode number: Episode number 197, number five of season nine.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s the final countdown...

We done did it! 22 stories for 22 asks from the 100 Prompts List!!!

@summerblosoms requested #91 (yay for the only DIY pick). They said,

“If you could make Spencer have something along the lines of appendicitis and be really sick that would be great. Like have him faint at work or something from being so sick.”

Your wish is my command! This is probably slightly medically inaccurate. I’m basing it on what I think I know about Harry Houdini (which is not a lot).

Bear with me; it’s a bit long.

___

“Are you sure you’re ok?” JJ asks.

Spencer pauses as he slides into the backseat of the black SUV, trying not to wince as the change in position agitates his stomach.

“You took a hard hit back there. I wish you would’ve let the paramedics check you out.” JJ holds the car door open and watches Spencer shakily fasten his seatbelt.

“I’m ok,” he says. He’s been saying it for hours now. After the unsub had punched him in the gut, to the police and firefighters surrounding the scene, and a thousand times on the flight back home to Quantico. “I just need to wait for it to bruise and start healing.”

JJ sighs and gives him a sad smile. “At least come by my desk and get some Aleve. You…look like you’re having a hard enough time.”

“Yeah, ok,” Spencer replies. He waits for JJ to shut the door and climb into the SUV’s front seat, then leans back and shuts his eyes. The pink inflamed skin on the right side of his abdomen is tender to the touch of anything from his fingers to his shirt, and the dazed nausea that follows such a hard hit still lingers. He’s sure nothing’s damaged, though. The pain he feels isn’t the sharpness of a fracture in his rib or hip bone. Just generalized discomfort. That’s currently making him feel like he needs to vomit. But he’s fine.

The ride from the airstrip back to the office is short, made to feel shorter by the sleepy darkness outside. It’s after 11 at night, and while the agents are used to odd hours, it doesn’t make the prospect of sleepy paperwork any more inviting.

“Just do the minimum,” Hotch says when everyone piles out of the elevator and heads to their desks. “Only the most important paperwork. Get things written down while they’re fresh in your mind. Then go home.” He makes eye contact with each team member to ensure understanding. “And sleep in tomorrow. I’ll call if another case drops.”

Spencer trudges to his chair and opens a drawer of files. He selects blank case report forms and a pen, then sighs and bends over the desktop. The position forces his ribcage to put pressure on his stomach, and exterior pain and interior nausea combine in swirling uneasiness.

He works on the papers for a few minutes. He’s forcibly reminded of being a child in school, scribbling out answers on worksheets while trying to hide an upset stomach lest he be sent to the nurse’s office. He’d been eight years old. And he’d thrown up all over his math workbook.

But that’s not the situation now. Spencer’s an adult. Case reports are immensely more important than arithmetic problems, and he should be focusing. So what if he’s hurting a little bit? He can’t let small things distract him. It doesn’t even hurt that much. He’s fine.

“Spence?” JJ’s at his shoulder with a bottle of pills and a Styrofoam cup of metallic-tasting tap water. “Here.” She portions out a dose of naproxen sodium and hands it over. Her soft fingers linger for a moment on Spencer’s clammy palm. He draws back and tosses the pill down his throat, mostly dry-swallowing it before gulping down the water as a chaser.

“It’s ok if you’re hurting, you know,” JJ murmurs.

“I’m ok.” Spencer really wishes he has something else to say.

One by one, the agents take their leave. Garcia promises donuts and lattes in the morning to make up for the late night. Hotch tells her to stop spending her own money on the team, but the blithe tech analyst just whips out a pom-pom topped pen and scribbles down everyone’s usual Starbucks order.

“Americano with way too many sugars?” she asks when she makes her round to Spencer’s desk.

It is his usual favorite, but right now it sounds revolting. Spencer tries not to let it show in his voice when he says, “Yeah. Sure.”

“What’s wrong?” Garcia asks immediately, her mouth turning down in an expression of concern.

“Nothing, I’m fine,” Spencer lies again.

“Hey, but, no, no you’re not.” Garcia puts a hand on Spencer’s shoulder. “You feeling ok? I heard you got beat up…”

“Yeah, I’m just kind of tired,” Spencer says.

“Then get out of here.” Hotch approaches on Spencer’s other side. He has his briefcase in hand and his coat over his arm as if he’s on the way out the door himself. “Really, with a memory like yours, you can work all your forms in the morning.”

Normally, Spencer would humbly agree. It’s usually not a challenge to recall past events with a good degree of exactitude. Now, though, everything seems fuzzy. Except for the memory of the gloved fist coming into slow-motion contact with Spencer’s side before he’d had the opportunity to don a bulletproof vest or draw a weapon.

“I will,” Spencer says. “In just a minute. I really want to get this first page done…” He looks down at his sloppy scribbles and the two or three blank spaces still remaining on the sheet.

“I’ll take your word for it,” Hotch says, giving Spencer a serious nod. “If I find out you’ve stayed here halfway through the night, we’ll have to talk about you working yourself too hard.”

“Yes, sir,” Spencer articulates.

“I’ll get you an extra-special donut,” Garcia promises. Worry flickers in her eyes for a second, but Spencer pulls a pained smile that seems to placate her enough to take her leave.

Finally all the other agents are gone. Spencer lowers his head to his desk, ignoring the greasy forehead print he’s leaving on the case file. He should go home. He wants more than anything to sleep. But his gut is brewing a queasy feeling that ricochets off the pain in his stomach and shoots up to his skull. Because a headache to match his stomachache is exactly what he needs right now.

Standing up and walking and sitting and driving and walking and lying down all seem like hassles Spencer’s not equipped to deal with in his current state of misery. Maybe the painkiller JJ gave him will kick in soon and relieve some of the awful, swirling stress. He’ll shut his eyes, just for a moment…

Spencer starts awake and sits up abruptly. He’s still in his office chair, and papers and files leave creases in his clammy cheek. Dizziness assaults him as soon as he’s upright. The lamp on his desk is on, but all other lights in the bullpen are extinguished.

The lighted dial on his watch tells Spencer it’s a bit after 4 in the morning. He’s slept some, but in an uncomfortable position. He’s still less than rested. Spencer scrubs his hands over his face, his fingertips tingling as they drag over stubble on their way up to his hairline. His whole body feels sweaty and just shy of disgusting. A feverish ache thrums in his temples, and pain lances up and out from his stomach.

It’s too late to go home. But it’s also too early to do anything else. On a normal day, agents generally start filing in around 7. But after yesterday’s late night and the promise of a less-than-early start, Spencer doubts he’ll see anyone before 8:30. So really, he does have time to go home, shower, sleep, and come back. He abandons the idea when the motion to stand up has him swallowing down bile.

There’s still a clean shirt in his go-bag, so Spencer digs it out and heads for the bathroom to change. He’ll take every precaution if it means he can avoid his fellow agents knowing that he’s spent the night here. Spencer uses his shoulder to open the heavy washroom door, and the motion-detected light snaps on as soon as he’s crossed the threshold.

He squints against the brightness, but Spencer can clearly see that he looks awful. He slips out of his cardigan and unbuttons his white oxford shirt. He sheds his undershirt, wads up the fabric, and uses it to dab oiliness and sweat from his face. Then he turns his attention to the patch of blushed purple spreading over the right side of his abdomen.

The skin isn’t broken, but it’s inflamed with the slight puffiness that surrounds healing cuts. Blood has seeped under the skin to show up as a reddish-violet shadow that’s sure to darken to all colors of black and blue and green as it heals. Spencer dabs at the injury, and searing heat follows the touch of his fingers. His skin hurts on the outside, and something definitely hurts on the inside. Spencer’s stomach clenches, and he wonders if he’s going to throw up as he stands there, clutching the counter with one hand and praying he doesn’t fall over.

Pain signals often redirect to nausea. It’s unfortunate, but not uncommon. But Spencer feels sick too. Not just to his stomach, but all over. Tender aches creep into his lower back and up and down to the joints of his arms and legs. His head’s wanging. But that might be from dehydration. Besides the sip of water Spencer took along with the painkillers last night, he doesn’t know when he last drank. Or ate. But he feels so far from hunger it’s almost comical.

Spencer scoops water from the bathroom faucet and splashes it over his face. He uses a couple paper towels to dry off and wipe perspiration from under his arms. Satisfied that he’s as clean as he’s going to get, he shakes the wrinkles out of his fresh shirt and buttons it over his bare chest, cringing as the starched fabric brushes his injury.

He exits the bathroom and drops his dirty clothes in his go-bag. Then Spencer glances around for something to keep him occupied for the next few hours. He considers going back to the case file, but too much work done on it will arouse suspicion and potentially alert his co-workers to the fact that he’s been here all night. Spencer’s eyes alight on the coffeemaker, and though the idea of putting anything in his stomach is still revolting, at least sipping will be something to do. And perhaps the caffeine will get him feeling back like himself. Or at least make a dent in the headache.

He returns to his desk once he has a steaming foam cup in his trembling hand. The first sip feels energizing as Spencer swallows it, but it doesn’t taste good. More sweat breaks out across his moustache, and the heat of his bruise flares as the liquid drips into his stomach.

Heaving a deep sigh, Spencer opens his desk drawer and paws around for anything worth passing time with. He pulls out one of Rossi’s books and stares down at the face of his friend and fellow agent on the dust jacket. Spencer’s read it before, and he recalls most of the main points, but he opens it anyway and begins to read. He goes intentionally slowly, hearing Rossi’s voice in each word. Spencer’s used to reading for content alone, and he has to admit that the hours passed moving his gaze at a snail’s pace across the page is a welcome change. Or at least it is until his eyes start to lose focus and nausea begins creeping up on him again.

Overly sweet and coffee-flavored spit floods Spencer’s mouth. He sets the book on the desktop where it flops shut, losing his page. He brings both hands up to cover his nose and lips and sucks in a long breath that does little to soothe the bubbling tumult in his stomach. Heat flashes over Spencer’s skin, and his hands and feet feel unnaturally cold and damp.

He stumbles up and trips toward the bathroom as his liquid stomach contents start to make a reappearance at the back of his throat. Spencer sprints past the row of sinks and throws himself head-first into the lonely stall. He retches as soon as his knees hit the ground. His abdominals contract, igniting lines of lightning-hot pain across his bruised stomach. Spencer moans into the echoing toilet bowl and spits out strings of mucous.

The fact that there’s little to purge doesn’t stop Spencer’s stomach from turning itself inside out. He’s empty and aching after a few decent heaves, but dry retching quickly sets in, bringing more pain with each spine-arching contraction. He wraps his long fingers around the toilet seat and watches his knuckles go white from the bone-crushing pressure. He’s still so seasick he can barely move.

When the heaves dissolve into hiccups, Spencer shakily pulls himself to his feet, using the toilet paper dispenser for support. His eyeballs feel like they’re vibrating in their sockets, giving him the overall feeling that the earth is jittering beneath his feet. He crosses to the counter of sinks and splashes his face again, bringing a handful up to his lips to rinse the disgusting taste of caffeinated bile from his tongue.

After pressing a paper towel to his ashen skin, Spencer exits the bathroom. His loose plan is to head back for his desk and curl inward; just standing upright stretches the skin of his stomach and invites the roiling throb to escalate.

All ideas are dashed, though, when he opens the door to see the back of a blonde head and pink-sweatered shoulders bobbing around the desks in the bullpen.

Spencer lets go of the bathroom door without realizing what he’s doing, and the resulting slam jars him as much as it does Garcia.

“Oh my god!” the tech analyst shrieks, dropping the box of donuts in her arms and sending them bouncing across the floor and under Morgan’s desk. She whips around and looks for the source of the noise. Her eyes widen behind her brightly colored glasses when she sees Spencer. “Oh my god,” she repeats.

Garcia’s high heels clack as she rushes to Spencer’s side, but the sound grows fuzzy on its way up to his ears. Stars start to blink at the corners of his visual field, and Spencer’s head feels heavy and lopsided. Without warning, the world tips sickeningly, and the ceiling swaps places with the bullpen’s eastern wall. He blinks hard to see if the illusion will clear. But it doesn’t, and the back of his head smack against something hard.

“Reid! Oh, god, sweetheart…” Warm hands find Spencer’s shoulders, then move up to cup his cheeks. He forces his eyes open to see Penelope’s blurry face, then doubles instinctively onto his side as a rush of nausea forces itself up and out.

“Ok, you’re ok,” Garcia murmurs, patting Spencer on the back as he throws up spit and air. Then she changes tact, the panic in her voice escalating. “You’re not ok. You’re really sick.” She palms Spencer’s sweaty forehead. “You’re really, really sick.”

Spencer coughs and clutches his stomach, grunting in pain when he presses too hard on the wound dominating his right side.

“Your stomach?” Garcia asks. She reaches down and lifts the tails of Spencer’s untucked shirt to expose the bare skin underneath. “Oh my…” she trails off when she sees the spread of bruising. “You’re—Reid, I don’t…I’m gonna call an ambulance, ok?” She lightly palpates the discolored area on his stomach, and Spencer lets out an involuntary cry when her fingers rebound.

“Oh god, that’s right where your appendix is,” she worries. “If you got hit and it’s all infected…” Penelope trails off and yanks her neon-encased cell phone from her pocket. “I’m calling right now. You’re gonna be ok.”

Spencer hears the phone ringing out a couple times before an operator picks up. And over the tone, he can hear Garcia whispering, “You’ll be ok. You have to be ok.”

The ambulance ride and everything after is a blur. The next thing Spencer knows, he’s in an unfamiliar bed in an unfamiliar room. He’s groggy, and every inch of his body hurts. He can see a nasal cannula in his peripheral vision, dispensing oxygen into his tired lungs. A glance to one side shows an IV stand and heart monitor. In the other direction is a chair. Garcia’s slumped against the wall, her eyes closed and mouth open in the posture of uncomfortable upright sleep.

“Garcia?” Spencer wheezes.

“Huh?” Penelope snaps up, wiping drool from her lip with the back of her hand. “I said you’d be ok, right?” she says sleepily.

“Yeah.” Spencer nods. “Yeah, I think you did.”

#criminal minds#fanfic#fanfiction#sickfic#injury#appendicitis#emeto#emetophilia#spencer reid#reid whump#penelope garcia#jj#jennifer jereau#hotch#aaron hotchner

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

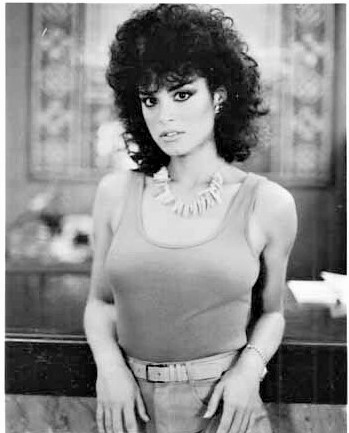

Russell was born in San Diego, California, the daughter of Constance (née Lerner) and Richard Lion Russell, a stock analyst. Three of her four grandparents were Jewish. Her maternal grandfather was journalist and educator Max Lerner. Russell wanted to be an actress since the age of eight and started acting in school plays. She appeared in a Pepsi commercial that was taped locally while in high school. After graduating from Mission Bay High School in 1981, she moved to Los Angeles and began taking acting classes before landing her first role. She did a masters program in Spiritual Psychology at the University of Santa Monica and is a certified hypnotist and life coach, also from the University of Santa Monica.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The day after graduating high school, with limited commercial and modeling experience. Russell set out for Los Angeles with a UCLA-bound girlfriend. She located a roommate, actress Diane Brody, via the campus bulletin board. Brody helped Russell line up acting classes and waitressing jobs. Accompanying an acting classmate to an audition, Russell walked away with representation. She was subsequently cast in an unapologetic PORKY’S clone titled Private School (1983)

Private School (1983) Chris from a girls’ boarding school loves Jim from a nearby boys’ boarding school. Jordan also wants Jim and plays dirty. Jim and 2 friends visit the girls’ school posing as girls.

Russell played Jordan Leigh-Jensen, “a spoiled rich girl willing to do anything to get her way.” As her romantic rival, the top-billed Phoebe Cates waged war for the affections of Matthew Modine. Critics excoriated the film’s leering sexism, but Russell’s recollections are pleasant. “It was like walking on air,” she recalled. “Phoebe Cates was my idol at the time, and she was so nice to me. We grew very close, and she was fun to work with.”

Phobe Cates, in fact, coached the novice actress who was nervous about her nude scene: “Phoebe said, ‘Oh, this is nothing-in Paradise (1982) I had nude scenes. To make matters more stressful, old acquaintances showed up on the day Russell was shooting her topless “Lady Godiva” scene. “I hadn’t seen these people in years,” laughed Russell. “They turned up on the set, outdoors in the middle of nowhere. The director made them leave. It was hysterical. I learned that day not to take it all too seriously.”

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

She insists that reviews, citing herself as the film’s sole asset, caused no friction with leading lady Cates. Phoebe is very secure with herself, stated Russell “She should be. Look at her now! We didn’t pay any attention to critics.”

Offers promptly rolled in. One of the networks offered Russell a spot on any series she wanted Numerous agents called, Playboy asked her to pose for a pictorial on struggling actresses in Hollywood. Although she does not regret turning down Playboy, Russell admits that she, and her management, did not make the best choice of opportunities. Though she auditioned for smaller parts in higher profile filmy, she inevitably landed leads in B-movies.

Out of Control (1985) Teens (Martin Hewitt, Betsy Russell, Sherilyn Fenn) crash-land on an island, find vodka, play strip spin-the-bottle and run into drug smugglers

In Out of Control (1985), Martin Hewitt and Russell were cast as a prom king and queen who invite six of their classmates on a “grad night” chartered flight. The plane crashes and the kids acclimate themselves to survival on a deserted island. Most critics panned the film, but the Los Angeles Times and L.A. Weekly gave it good reviews.

“We filmed in Yugoslavia,” explained Russell. “It was fun. There were a lot of us around the same age… Martin Hewitt, Sherilyn Fenn. Russell remembered that Fenn, who debuted in the film, “was the youngest of us all and very sweet. We both liked Martin. I liked him for about two minutes the first day, and she ended up breaking his heart. The producer, Fred Weintraub, said, ‘Sherilyn is going to be huge-she’s going to break a lot of hearts. He was right. She’s worked very hard and she deserves her success.”

Russell played the title role in her third film, Tomboy (1985), Her character, Tommy Boyd, was a curvaceous auto mechanic with car racing ambitions. The movie was dogged by controversy: despite it’s claims of feminist affirmation, TOMBOY was peppered with the usual B-quota of sex and nudity.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Tomboy (1985) A strong-willed female stock car driver challenges her chauvinistic crush to a race to win his respect- and get him into bed.

“It turned out all right, said Russell. “Actually, that movie surprised me. I’ve heard a lot of people really loved that movie. At first, I thought it was going to be kind of dumb but I’ve gotten great response. I saw it about a year ago and thought it wasn’t so bad.”

Avenging Angel (1985) was more of a challenge for Russell. The film served as a sequel to 1983’s ANGEL, about a high school student’s double life as a hooker. “That was a rough experience, because I didn’t understand the character,” recalled Russell. “I felt kind of unsure I was still very young and this had all come very fast, and I hadn’t really studied that much. I didn’t totally relate to the character. Angel wasn’t an everyday girl. It was something new to me, and I didn’t have time to do any research.”

Avenging Angel (1985) Molly, former prostitute, has managed to leave her street life with help from Lt. Andrews. She studies law and leads a normal life. When Andrews is killed by a brutal gang, she returns to the streets as Angel to find his killers.

Although ANGEL had been released only two years previously, the sequel’s storyline picks up five years after the conclusion of its predecessor, Producer Keith Rubenstein and director Robert Vincent O’Neil felt that Donna Wilkes, who played the title role as the first ANGEL, wasn’t credible as a college graduate. The sequel’s investors, however, insisted that Wilkes reprise her familiar role. But it was Wilkes, pricing herself out of the market, who finally broke the stalemate. Cast as a streetwise heroine, Russell drew unflattering reviews from critics.

“Queen of Schlock Wants to Abdicate,” announced the Los Angeles Herald Examiner. After AVENGING ANGEL, it appeared Russell was fed up with her movie career. “I’ve done four B movies and now I’m just gonna stop,” she told a reporter. “I’ve paid my dues, and four is enough.” Russell also related that a meaty role in PRIVATE SCHOOL blinded her to its exploitation elements. She was critical of her involvement in B-films, and pledged to stop making them.

During the next two years, Russell turned to television, performing guest stints on T.J. HOOKER MURDER, SHE WROTE, FAMILY TIES, and THE A-TEAM, “I had down time, she noted. “I didn’t really want to do more nudity. I didn’t want to do B-movies and be taking my clothes off.” A lack of good scripts also prompted Russell to decelerate her movie output.

Cheerleader Camp (1988) A group of cheerleaders become the targets of an unknown killer at a remote summer camp.

Russell wasn’t obligated to disrobe in her next film, Cheerleader Camp (1988) which was initially promoted as BLOODY POM POMS. The plot: cheerleaders, including centerfolds Teri Weigel and Rebecca Ferratti, are sliced and diced while attending a wilderness retreat. The slasher epic hardly adhered to Russell’s speculations about a future in A-movies. “CHEERLEADER CAMP came along, and I liked the character, the actress explained. “She was kind of cute. She was getting driven crazy, and I could keep all my clothes on because the Playmates around me took all their clothes off. It was fun, too, working in Sequoia National Forest. I’ve always made friends with every film I’ve done.”

Following the film, she renewed a past friendship with actor Vince Van Patten. “I met him at the Playboy mansion when I first moved to L.A., Russell recounted. “We dated a few times, and then I never heard from him again. He was involved with the tennis circuit. We both really liked each other, but at the time he wasn’t right. I broke up with my boyfriend five years ago, ran into Vince at the Hard Rock Cafe and the rest is history. The timing was perfect.”

Trapper County War (1989) Two city boys (Estes, Blake) get in trouble with a backwoods North Carolina family (Swayze, Armstrong, Hunky, and Evans) when they try to help an abused step-daughter (Russell). Bo Hopkins and Ernie Hudson are the good locals who attempt to help the boys.

Russell’s last turn as a teenage ingenue was Trapper County War (1989), an updated, sanitized version of DELIVERANCE. Playing the 17-year-old adopted daughter of a backwoods family, Russell served as the city slicker’s love interest.

In Delta Heat (1992), a film noir thriller shot two years ago in New Orleans, Russell was cast as a deceased drug kingpin’s daughter. Academy Entertainment recently released the film on video. “New Line wanted it.” smiled Russell, but the investors had already made a deal with Academy. I think it should have come out in theatres. It’s pretty good.”

Delta Heat (1992) An L.A. cop investigates the death of his partner in the swamps of Louisiana. Enlisting the help of an ex-cop who lost his hand to an alligator many years before.

In Amore! (1993), “It’s Jack Scalia and Kathy Ireland and me, but you wouldn’t know it because of my billing,” laughed Russell. “I’m definitely in the movie. In fact, it’s only me and Scalia in the first half of the movie, and we get divorced and Kathy Ireland comes in. It was my first real comedy.” As the film started to roll, Russell had something else in production. I was three months pregnant at start time, and kept getting bigger!,” she revealed. “I finished the movie when I was four and a half months, and the filmmakers never knew I was pregnant.”

Her husband, who has retired from tennis, is producing a movie adapted from his own script. Rewritten by Dan Jenkins (Semi-Tough), The Break (1995)is a family affair for the Van Pattens. “It’s my first small part in a really good movie,” beams Russell “It’s like ROCKY or BULL DURHAM with tennis. Vince plays the veteran coach, with this rookie kid that he has to coach for the summer. I play the love interest to the kid. I’m the older woman.” She laughs, reflecting upon her ten-year development from PRIVATE SCHOOL starlet to more mature character actress.

When addressed with questions regarding nudity, Russell replied, “If BASIC INSTINCT came my way. I’m sure I wouldn’t have turned it down. It depends on who’s in the movie, what kind of part it is, what the movie’s about. But, you know, I’m not getting those types of offers or scripts anymore, so I’m not worried about it.

“I hope to do good work, to do entertaining, enjoyable projects,” Russell continued. Then, with a glimmer in her eye not at all reminiscent of Arnold Schwarzenegger, she smiled and vowed, “I’ll be back…”

Interview with Betsy Russell

What is the difference between the filmmakers you were working with in your early career versus the filmmakers of today?

Betsy Russell: That’s an interesting question because I was just reading a little blurb online about a director on a movie I did called ‘Out of Control’ [1985, directed by Allan Holzman], and he went on to do award winning things, documentaries and other films. The directors I work with now are amazing, talented and insightful, but I’ve also worked with directors before who have gone on to do incredible things. For example, the dialogue coach from Private School [Jerry Zaks] went on to a Broadway career. All the people I worked with were fine. I don’t like to compare one to the other, they are all different.

When you made “Private School” back in the early 1980s, the videotape revolution had just begun. What do you think of how your images from that film proliferated from VHS to DVD to the internet? What do you think of the ability to download virtually anything from the internet, including those pictures of your younger days?

Betsy Russell: When I said I would do the topless scene, because it wasn’t in the original script for Private School. I remember thinking I’m 19 years old, my body is great and for the rest of my life I’m going to have something on film that the people will say, ‘yeah, she’s topless but that is my Mom, that was my Grandmother, that was my Great-Grandmother’s first film.’

I remember thinking this is kind of cool, why not? Just to have it out there now in the ‘anything goes’ era, with Playmates becoming TV stars and the like, I am proud of it, I’m proud of my body and I’m proud of the sort of free feeling that my character had in that movie, not inhibited whatsoever. It’s more of a European-type feeling, that the body can be a beautiful thing. There is reason to hide it.

You were beautiful then, you are beautiful now, nothing to worry about. Do you remember the name of the famous horse on which you rode to 1980s movie glory?

Betsy Russell: No, because he almost killed me. I didn’t know how to ride very well and I got on it just to get to know the horse. We didn’t have a very big budget so that the stunt guys had gotten some kind of wild horse. The minute I got on the horse it took off with me. Of course, everybody was at lunch except for the stunt guys, the horse wranglers and me. I thought I was going to die, because it started to run out of the stable area. Somebody finally stopped it. So I don’t remember the name, but it ended up being a quiet, passive horse after that incident.

You were fairly busy in the 1980s with your career. Was there anything that you auditioned for or didn’t do that you think might have led to a different career track?

Betsy Russell: Yeah, I was a favorite of a casting director name Wally Nicita, and she eventually became a producer. She was a big fan of mine after Private School, and there was a film coming up called ‘Silverado.’ I was shooting ‘Avenging Angel at the time and I had an audition. It was a night shoot, I was very tired and I didn’t really understand the ins and outs of the business, I relied more on my manager to take care of that, and he was learning to as we went along.

So they called for me at the audition for Silverado, and I didn’t pay attention to who had been cast in it. I just looked at it as an ensemble piece, and the other movie I was auditioning for was a ski movie, in which I would star. I just said let’s go for the bigger part. As luck would have it, the audition was in the same building as Wally Nicita’s office, and she kept saying how much the directors and producers of Silverado would love to see me. I told her no, I was here for the other audition. She looked at me like I was the stupidest person on the planet, and never contacted me for anything again. Everything happens for a reason. I always believe my career would have been different had I done that part. I can’t say if it would have been better or worse. I’ve had a good run.

Tomboy had your character as a mechanic. How did this occupation change your character from a typical character?

Betsy Russell: It defined her. I was playing a girl who loves auto mechanics. My oldest sister was a mechanic growing up. She did all the lube jobs on the car – she was that type of person. It wasn’t far out for me to imagine myself as that type of character. That’s what she did. She was a tomboy who liked riding motorcycles and playing basketball.

What are your thoughts on the trailer for Tomboy showing you as a strong female, but then cutting to you in the shower?

Betsy Russell: I’ve never really paid attention to that. I don’t know that I’ve seen it. I guess strong females still have to take showers. They still like to feel sexy, so I don’t think there’s one thing that should stop someone from feeling sexy and showing their body if that’s what they choose to do. I don’t think it makes any difference in the world.

Tomboy is arguably feminist. Was this a draw for you?

Betsy Russell: Yes, I like playing strong characters. I thought it would be fun. I was probably twenty-one years old, so the idea of playing this type of character was great. I didn’t think that hard about it. I said, “Ok, this is another role, this is what she does, and I’m going to get into it.” I started working with the assistant basketball coach at UCLA, trying to learn a little bit of basketball. At that point in my life I wasn’t thinking that long or hard about which role to take. I did have a couple of offers with Tomboy; I had another offer for another movie. I picked this one. I’m sure that was a draw for me.

What do you think makes it a feminist role?

Betsy Russell: She has a career that isn’t the norm for women. Usually women rely on men to do all the mechanical things. It’s kind of unusual for a woman to be a mechanic. I think it’s silly to be unusual, but I guess it is.

In the same vein, what role does feminism play in Avenging Angel?

Betsy Russell: I barely remember that movie, but I know Angel carries a gun. She’s a tough chick. I saw that movie maybe one time. I don’t remember it well, but I had a lot of fun doing it.

There were a couple of stronger roles you did early on. Did you find yourself drawn to the stronger roles?

Betsy Russell: Typically the leads in movies are stronger women. Nobody wants to watch a wimp for two hours. I played more of a leading lady than the sidekick. I don’t think I’ve ever played the sidekick. If given the chance, I would have. I did what I thought was good.

How did you get your role in Avenging Angel?

Betsy Russell: I auditioned first, but then the director fought for me. The producer wanted the girl from the first movie. The director said he wouldn’t do the movie without me. That was nice.

Do you remember having a favorite line from Avenging Angel?

Betsy Russell: No, but a lot of people tell me their favorite line from it, and I don’t remember anything.

What were your thoughts on Cheerleader Camp (1988) and Camp Fear (1991) and how have these thoughts evolved over time?

Betsy Russell: Camp Fear was somebody called me and said, “Would you and your husband, Vince, like to do this little movie? You’re going to make a lot of money for three weeks shoot, and it’s going to go right to video.” I said, “Great, I want to make a lot of money. If nobody sees it, I guess it doesn’t matter. It’ll be fun to work with my husband.” We did it. Who knew that YouTube would happen. I’ve never seen the movie, so I have no idea. I’m sure I was terrible in it. It would be hard to be anything but terrible in it. I’ve always seen bits and pieces on YouTube. My voice is really high in it. We had fun. My brother-in-law is in that movie. I remember the actor playing the Indian could never remember his lines; we laughed so hard we almost fell off a cliff. That guy who played the Indian asked Vince to be his best man at his wedding. We barely knew him so that was funny. That happened back when they would say, “No one’s ever going to see it.” You’d do it. As an actor, if you’re not working, you want to just work. It doesn’t matter all of the time if it’s best project if you haven’t worked in a while. You have to put some money in the bank. That’s why I did that. Cheerleader Camp, I hadn’t offered this role called Bloody Pom Pom’s at the time. I remember thinking, “Oh my gosh, I don’t have to take any clothes off.” At that time, coming from Private School, Tomboy, and Out of Control (1985), I was tired of taking my clothes off. I wore those big nightgowns, and I just wanted to be taken seriously. That’s why I did that movie. I had a lot of fun filming it. As for Cheerleader Camp, we didn’t know we were making kind of a farce. Honestly, it was a little bit funny, but I took my character very seriously. We were rewriting scenes on the set five minutes before.

What are your views on nudity in film?

Betsy Russell: I don’t have any negative views on it at all. In my twenties, I would say, “If it’s intrinsic to the character then I think it’s great.” I learned that word, intrinsic, just to say that. I really don’t have any problem with it. If it’s just thrown in there because it’s a low-budget movie and they’re trying to sell it, it’s really obvious. It takes you out, which isn’t always great. Sometimes it’s just right for what’s going on. It’s great that the actor or actress isn’t embarrassed to show it. If it looks good then it’s great. If it’s a person who looks terrible I would rather they keep their clothes on. If it’s important to the role and that type of film then it’s fine.

CREDITS/REFERENCES/SOURCES/BIBLIOGRAPHY

Femme Fatales v02n02 0038

Bad Ass Women of Cinema: A Collection of Interviews Chris Watson

hollywoodchicago

Betsy Russell: 80’s B Film Princess Russell was born in San Diego, California, the daughter of Constance (née Lerner) and Richard Lion Russell, a stock analyst.

0 notes

Text

How the Corona Virus Affects Your Favorite Artists and What You Can Do To Help

It is no secret by now that Rona is taking over and seriously hurting multiple industries, including the music industry. Analysts told Forbes the music industry could lose up to $5 billion. This is because since streaming came along, the primary income for artists shifted to touring and merchandise. As TOKiMONSTA told Vulture, “as a touring artist where the bulk of my living comes from touring, it’s a lot to deal with… I’m essentially not making any money this month, which is tough as a musician. This career is already really volatile.” She goes on to explain she is lucky to be a more established artist with savings, but that is not the case for all artists. Liam Parsons from Good Morning knows that struggle as he explains, “We took a massive financial hit from this… we’re at least down $10,000 on money already spent. In terms of lost guarantees and potential merch sales, around $25,000. We also left our jobs before we left, so we’re going back to nothing.”

So what can we do as fans, listeners and supporters? Here are a five key ways to help your favorite musicians stay afloat.

First, instead of collecting and hoarding toilet paper, collect and hoard your favorite music! Growing your collection of physicals, CDs, and vinyl’s is not only a great way to connect with artists, but also a great way to directly support them in this time. Besides, what else will you have to do once you’ve already finished the new show you wanted to see and re-watched your favorite show for the third time? Also, for the shopaholics out there, instead of going out to the mall, go online to buy your favorite artists’ shirts, buttons and other merchandise! You can satisfy your desire for a new graphic shirt while also being there for artists in need of support. A few tips though – make sure to purchase directly from the band or artist website instead of third party retailers who usually take their own deduction!

Second, another way to support is to tune in to all online content! Many artists, especially those who had shows scheduled, are getting creative and reverting to livestream concerts. Set time aside to tune in to these concerts, like you would to attend an actual concert! Yungblud, for example, plans to do a livestream where he’ll “be playing songs, gonna bring some of my friends out, do some skits, and do a late-night show — like a rock and roll version of fuckin’ Jimmy Kimmel. Try to give people a bit of positivity, laughter, and emotion.” That really will be one to watch. Support artist livestreams, watch their videos, subscribe to their Youtube or Patreon channels, and share their content and music in your playlists or on your socials. Everything counts!

Some artists are avoiding livestream shows because the energy does not always translate. In that case, revert to our other tips, like this next one- keep listening but don’t stream or download! Instead, listen to physical albums that you purchased. Bandcamp is another great place to listen to music. The platform allows independent artists to control their own prices and even allows you to donate as much as you’d like to the artist.

Fourth, are your favorite artists doing any crowd funding campaigns? Whether it’s GoFundMe or Kickstarter, contributing to these campaigns is a great way to show your support. Plain and simple!

Lastly, be sure to also show support for venues and music clubs. Why? Because arguably the group in the music industry that Rona hits the hardest is the tour and venue staff, from tour managers to the crew to the venue operators, all of whom rely on ticket and drink sales for revenue. You can buy merchandise from these venues online. To go a step further, if you had purchased tickets for a show or festival, (and if you are in a position to do so), considering not asking for ticket refunds.Ticket income not only goes back to the artists, but also into the paychecks of every crewmember involved in making a show happen.

Speaking on the Rona chaos, Mia Berrin from Pom Pom Squad brings up an important question: “There’s less and less room for developing artists in media, so how are we going to grow?” It is vital to support all artists in this time, especially upcoming artists hustling tirelessly on the come up. Tune in to their livestreams, buy their merch, support their side hustles. We are lucky to live in an age of technological advancement that allows us show support with the click of a button. Though some of these tips may seem obvious, they make the world of a difference.

Congratulations! You are now equipped with the various ways to support artists. Whether you plan to quarantine and chill with someone, or remain socially isolated, let the voice of your favorite artists keep you company and get you through this strange time we’re in.

0 notes

Text

‘Stuber’ Stalls, Dealing Another Setback to Comedies and Disney’s Fox

LOS ANGELES — “Stuber” stalled at the box office over the weekend, accentuating a problem with movies coming off the 20th Century Fox assembly line: They aren’t very good.

“Stuber,” an R-rated buddy flick starring Kumail Nanjiani and Dave Bautista that cost about $25 million to make, also raised new questions about the theatrical viability of modestly budgeted comedies in the Netflix age. North American moviegoers have given a cold shoulder to one such comedy after another this summer, including “Late Night,” “Long Shot,” “The Hustle,” “Shaft,” “Poms” and “Booksmart.”

As usual, franchises dominated multiplex marquees over the weekend. The No. 1 movie was “Spider-Man: Far From Home” (Sony Pictures), which collected about $45.3 million, for a 13-day domestic total of $274.5 million ($847 million worldwide). “Toy Story 4” (Disney-Pixar) was second, generating about $20.7 million in ticket sales, for a four-week global total of $771.1 million, according to Comscore.

Among new wide releases, “Crawl” (Paramount) did the best, capitalizing on surprisingly strong reviews. A horror movie about alligators on the loose during a hurricane, “Crawl” took in roughly $12 million, enough for third place. Paramount spent $13.5 million to make the R-rated movie, which the studio supported with a shrewd marketing campaign that positioned the film as a frothy summertime diversion.

“Stuber” arrived in fourth place. It collected $8 million.

Distributed by Disney, which took over the Fox movie factory in March, “Stuber” had a marketing campaign that cost at least $30 million. Disney aggressively went after men, releasing trailers during WrestleMania and the N.B.A. Finals. Disney-owned ESPN was a marketing partner. The film’s crass tagline: “Saving the day takes a pair.”

“Stuber,” about an Uber driver named Stu who picks up a detective, received largely negative reviews, according to the criticism-aggregation site Rotten Tomatoes. David A. Gross, who runs Franchise Entertainment Research, a movie consultancy, called it “an extremely weak entry.”

[Read our “Stuber” review.]

The previous Fox film released by Disney was the superhero movie “Dark Phoenix,” which collapsed under withering reviews last month. It cost an estimated $350 million to make and market worldwide and took in about $250 million, roughly half of which goes to theater owners.

Another Fox film, “Woman in the Window,” starring Amy Adams as an agoraphobic psychologist who witnesses a crime, was pulled from Disney’s 2019 release schedule last week and sent for reshoots. Instead of being released in October as planned, the movie will now arrive sometime next year.

Disney declined to comment on Fox’s output. Insiders say they have high hopes for “Ford v Ferrari,” a Fox bio-drama starring Matt Damon and Christian Bale that is scheduled for November release, among other films. Next up on the Disney-Fox roster is the drama “The Art of Racing in the Rain,” a dog-focused movie adapted from the 2008 novel of the same name.

To be fair to “Stuber,” even critically acclaimed comedies like “Booksmart” and “Late Night” have fizzled at the box office in recent months — and ticket sales for comedies and romantic comedies have been on a steady slide for the past decade, according to a recent analysis by The Hollywood Reporter. In 2009, comedies grossed $2.5 billion at the domestic box office; last year, the genre generated only $1 billion.