#Haageocereus

Photo

Haageocereus sp. seed pod.

Abbey Brook Cactus Nursery, Derbyshire.

November 2017.

#haageocereus#cactus#cacti#seed pods#fruit#abbey brook#photography#agavex-photography#2017#canon eos 750d

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hello! I need a little bit of advise, I got this cactus as a gift, and I have a few questions.

1) what type of cactus is this?

2) what is the best procedure for removing the fake glued on flowers?

3) how should it be repotted and watered, especially now in the winter?

Thank you so much for being such a helpful and trustworthy source for information!

Hi,

1. Haageocereus versicolor. 2. As carefully as possible, using a small pair of scissors or a craft knife to cut off as much glue as possible. 3. Now is a good time of year to repot it, just remove all the old soil and pot it up in a dry, well-aerated soil mix (such as 50/50 perlite/potting soil) and keep it dry for at least a week afterwards. You could leave it dry until the growing season starts or give it a bit of water every 3-4 weeks to encourage some root growth before the growing season starts properly.

Happy growing!

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Haageocereus

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Weberbauerocereus winterianus

We were not sure how well this columnar cactus from Peru would do in our northern California garden, but it has adjusted very well to our winter rainfall pattern and occasional dips below freezing. Its winter flowers are a joy, but we must appreciate them in the morning, since they do not stay open all that long in the daytime. This is common with bat-pollinated cacti, and we assume that bats are the natural pollinators in habitat. Weberbauerocereus has long been considered close to Haageocereus, but DNA research seems to indicate it is actually closer to Cleistocactus.

-Brian

93 notes

·

View notes

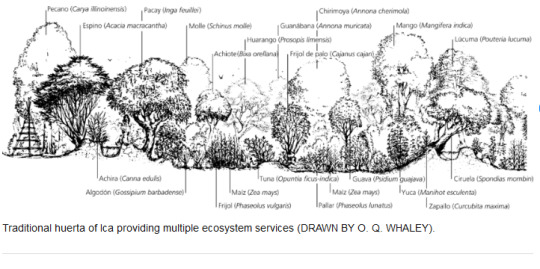

Text

Fog oasis. Rare desert plants. “Riparian consciousness.” Caretaking of dry forests. Specialized fog-capturing tree roots in sand dunes, where up to 40% of local plants are endemic. Ancient forest of Usaca. Earth’s driest (non-polar) desert. “The south coast of Peru is a hyperarid environment in which both people and plants are dependent on sporadic and unpredictable sources of water, but also,crucially where both depend intimately on each other. [...] Nazca is now famous for the giant geoglyphs [...]. Yet, Nazca’s fame by virtue of this [...] ritual [desert] space is somewhat ironic, since the people who made the Lines actually lived, farmed and foraged within the riparian dry forests, of which there are few remaining traces on the south coast today [...].

Examples of endemic plants on south coast Peru. A Ambrosia dentata ; B Cleistocactus acanthurus ; C Krameria lappacea *; D Haageocereus pseudomelanostele ; E Tecoma fulva subsp guarume ; F Alstroemeria aff. violacea ; G Evolvulus lanatus ; H Cistanthe paniculata . *also known from arid N. Argentina, Bolivia and Chile.

The Huarango geoglyph of the Nazca lines (DRAWN BY O. Q. WHALEY) and the ancient forest of Usaca.

[Tree roots which capture moisture from fog, many litres collected each night.]

The dry forest of the Peruvian south coast has undergone an almost total process of deforestation. [...] Indigenous communities still hold [...] traditional knowledge. Relicts of natural vegetation, traditional agriculture and agrobiodiversity continue to sustain [the] ecosystem [...]. These problems are particularly acute in the dry forests of arid areas [...]. The south coast of Peru is part of the Pacific coastal belt, which is one of the world’s oldest and driest areas known as the Peru Chile Desert. Its climate is hyper-arid, with an average annual precipitation of only 0.3 mm per year [driest non-polar desert on the planet]. [...] Equally important, as a source of moisture for plants,is coastal fog (‘garua’) occurring from June to December. These water sources support a surprisingly rich, highly adapted flora and fauna, including habitats with high endemism in quebradas (inter-Andean valleys) and lomas (fog meadow) [...]. In individual lomas communities, plant endemism at species level often exceeds 40% [...].

The project studies we present here increased the total Ica coastal flora (below 1500 m) from around 180 [...] to over 480 species [...]. We expect that total to rise to over 530 species because of the highly ephemeral nature of isolated and disparate plant communities [...]. Of this total number, around 29% appear to be endemic to Peru and Southern coastal Ecuador, and about 10%endemic to Ica and Southern Peru [...].

The riparian oases and associated lomas, quebradas and marine habitats of the south coast have supported a trajectory of human settlement and adaptation which spans the Holocene. Thus, the ancient human interaction with the environment is universally evident in the historical ecology of the region [...].

Huarangos of Ica can reach huge sizes — this tree is unique but today nearly dead due to insect plagues, many veteran specimens have now been converted to charcoal (2001).

We measured the quantity of atmospheric moisture captured by a small tree (three metres in height with a crown width of four metres) at up to nine litres per night. Through excavation under huarango canopies in sand dunes in fog areas, we found that the buried branches develop a fine matrix of superficial adventitious roots, presumably to capture this surface moisture. Areas of heavy nightly fog are indicated by the presence of epiphytic Tillandsia species (including T. purpurea Ruiz. & Pav.) growing in huarango, and at higher elevation in Cacti.

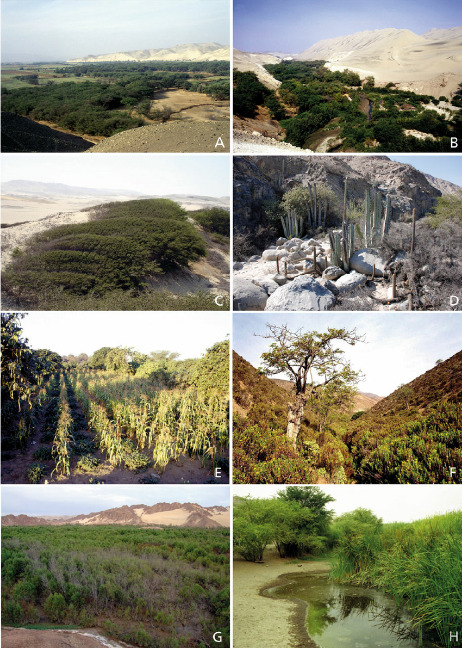

Vegetation types in Ica. A Prosopis dry forest (2001); B Riparian oasis dry forest (2005); C Prosopis dune forest (windy zone) (2002); D Cactus scrub forest (2008); E Acequia and huerta vegetation (2002); F Lomas (2001); G Tamarix aphylla invasion (2009); H Marshy spring or ‘ Puquio ’ (2005).

---

All photos, captions, and text [except heading] from: Oliver Whaley, David G. Beresford-Jones, William Milliken, Alfonso Orellano-Garcia, Anna Smyk, and Joaquin Leguia. “An ecosystem approach to restoration and sustainable management of dry forest in southern Peru.” Kew Bulletin. December 2010.

392 notes

·

View notes

Text

Such a beautiful flower....hope the pollination with my Haageocereus hybrid worked out. 👍 Also crossed this one with Trichocereus tunariensis.

🌵 #cactus #cactusflowers #flowers #echinopsis #gardening #garden #cacti #flower #plant #succulents #trichocereus #vlog #gardentv #cactusjerk #lobivia #plants #seeds #cactusseeds #nature #botany #photography

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cactus Haageocereus sp. en las lomas de Amoquinto. (en Amoquinto, Arequipa, Peru) https://www.instagram.com/p/CWzJ0p_lDLe/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

Loại cây mọc dại ở Việt Nam không ngờ lại có giá trên trời tại cửa hàng này

Loại cây mọc dại ở Việt Nam không ngờ lại có giá trên trời tại cửa hàng này

Cửa hàng giống cây Cactus tại NYC có bán một loạt các loại cây mới nghe tên thì có vẻ là loại tầm thường, nhưng thực chất đó đều là những giống cây rất hiếm. Một trong số đó là cây xương rồng Haageocereus tenuis, được đăng bán trên trang web của cửa hàng với giá 250.000 USD.

Cửa hàng tại NYC này chuyên bán các loại cây già cỗi, các giống cây hiếm và độc đáo đang phát…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Cây xương rồng quăn queo, dị dạng nhưng có giá hàng tỷ đồng vì lý do này

Hiện nay, thông tin về cây xương rồng quăn queo, dị dạng này vẫn còn khá mù mờ và khan hiếm.

Vừa qua, một cửa hàng xương rồng ở New York đã rao bán một cây xương rồng với giá 250.000 USD (5,7 tỷ đồng). Nhìn vẻ ngoài quăn queo, xấu xí, ít ai ngờ đây là giống cây hiếm Haageocereus tenuis, dự kiến sẽ bị tuyệt chủng vào năm 2024.

Chủ cửa hàng Christian Cummings cho biết, anh chỉ chuyên bán các giống…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

WELCOME TO the House of Pain. As I greet you, I’m suffering from various not-quite-self-inflicted wounds. There are small punctures in my shins and thighs where I’ve been pierced by the pointed ends of agave leaves. There are a couple of inflamed patches on my forearms where I splashed some sap on myself while trimming a euphorbia. There are opuntia spines in my hands and also, I’m sure, in my clothes, which I will only discover as they gradually work their way into my flesh.

Yes, I have been working in the Garden of Pain, which surrounds the house, what I usually refer to as a cactus garden, though in fact it contains as many succulents as it does cacti, and of course a few plants that are neither. Botanists differ, but the current consensus is that all cacti are succulents but by no means are all succulents cacti. This is only a small help, and the layman — which I most certainly am — can have a hell of a job telling what’s a true cactus and what isn’t. (Clue: It’s largely about the areoles.)

More correctly, I suppose I should say I have a xerophile garden. Xerophile: From the Greek, xeros meaning dry and philos meaning loving. (The term refers not to people who love these plants but to the plants themselves, which love dryness.) My own interest in xerophiles started when I moved to Los Angeles, partly because I took seriously all those warnings about the evils or watering your own backyard in a time of drought and partly because, as a deracinated Englishman, a xerophile garden was about as far away from the traditional English garden as I could imagine. But chiefly I got hooked because there’s something so compelling about living things that have so thoroughly adapted to hostile environments, and because xerophiles look so beautifully strange and strangely beautiful.

When word gets around that you’re a cactus (and xerophile) enthusiast people have a tendency to give you cactus-related items of varying degrees of kitschiness. And so in the House of Pain you’ll find T-shirts, tea towels, socks, and hats, all bearing images of cacti. There are cactus-shaped coasters, cactus-shaped margarita glasses, and a cactus-shaped bottle opener. Nobody, as yet, has offered me anything from Cartier’s “Cactus de Cartier” range, perhaps because the basic bracelet goes for about $30,000, but it’s early days.

Of course I have books, a shelf that includes Edward Abbey’s Cactus Country from the Time Life “American Wilderness” series; What Kinda Cactus Izzat?, a cartoon “who’s who of desert plants” by Reg Manning; the photographer Lee Friedlander’s The Desert Seen; and for the title alone (though the jacket’s pretty amazing too) Naked in a Cactus Garden by Jesse L. Lasky Jr., “a novel of Hollywood” in which “character after character is stripped of every pretense.” I’m also very fond of an essay titled “Cactus Teaching” by Michael Crichton (yes, that Michael Crichton) in which he goes to seek enlightenment at a meditation conference in the desert. He’s told to find a rock or plant that “speaks” to him, and after much searching and soul-searching he finds a small, unspectacular, damaged cactus in the garden of the institute where the conference is taking place. “The cactus had equanimity; ants ran over its surface, and it didn’t seem to mind,” Crichton writes. “It was certainly very attractive, with red thorns and a green body; bees were attracted to it. The cactus had a formal aspect; its pattern of thorns gave it almost a herringbone look. This was an Ivy League cactus. I saw it as dignified, silent, stoic, and out of place.”

If all this might make you think that I’m obsessed with xerophiles, my response would be to proffer a copy of Xerophile: Cactus Photographs from Expeditions of the Obsessed and say, “You think I’m obsessed — get a load of this.” No author is named on the jacket or the title page, but we in the L.A. xerophile community know that it’s the effort of Jeff Kaplon, Max Martin, and Carlos Morera, the guys who run Cactus Store in Echo Park. Xerophile is an extraordinary book, a singular and single-minded volume. It contains 300 pages of photographs, preceded by a three-page preface and rounded off with a 30-page section containing interviews with eight xerophile enthusiasts (xerophile-philes?): not people like me, but the kind who go on expeditions that require being dropped in by helicopter. There’s also a short appendix on relevant topics that includes “off-roading,” “mirage,” and “oblivion.”

But, really, it’s all about the photographs, taken over a period of some 70 years, of xerophiles glimpsed in situ around the world. A few are in the United States, but the majority are from Mexico and South America, along with outliers from such gloriously “far away places” as Somalia, the Galápagos Islands, Madagascar, and Namibia. Twenty-five named photographers are credited, although one or two images are captioned “photographer unknown,” and in some cases the date isn’t known either. This might create some irritation for the more academic reader, and I think that kind of reader is going to be irritated by other parts of the book too. As far as I can see there’s no obvious, overarching organizing principle at work in the arrangement and selection of photographs — it’s simply what’s in the Cactus Store’s archive — and yet I can’t say that I particularly minded. The overall effect is more celebratory than scholarly, and that’s fine by me.

Xerophile is somewhere between a coffee-table book and a slightly chaotic field guide. I know from extensive personal experience that it’s very easy to take dull pictures of cacti. And although some of the pictures in the book are incredibly dramatic, very few have the gloss and stylishness of professional photographs. The preface describes the images as “evidence.” A few are a bit blurry, either because of faltering focus or because of the low quality of the camera and lens, but this somehow only adds to the sense of authenticity. When you’re halfway up a mountain in Chile you may not have time for sophisticated and considered aesthetic choices. We’re not in National Geographic territory here. The plants are the stars, and the photographers are the adoring fans, perhaps in some cases the paparazzi, snapping what they can on the fly.

The fact is you can forgive quite a lot of technical and compositional failings in order to see things you’ve never seen before, like an Adenium in Namibia that looks like a long-dead tree but is bearing extraordinary white flowers at the tips of its branches. Or Peruvian Haageocereus plants growing in a foggy habitat and consequently covered in bright yellow lichen. Or cacti growing out of rock faces, poking up through broad stretches of sand or lava fields.

Human beings appear in some of the photographs. At the very least this is useful to give a sense of scale. We all know that cacti grow to spectacular heights, but when we see a picture that shows a full grown man looking utterly insignificant at the base of a 70-foot-tall Pachycereus pringlei, the sense of surprise and amazement is brought home with incredible force. Other pictures show botanists at work in the field, usually but not always in the desert, taking measurements or collecting seeds. One of my favorite photographs, dated 1952, shows George Lindsay, former director of the California Academy of Science, standing next to a Ferocactus that’s a good head taller than he is and much wider in girth. He’s khaki-clad, wearing sunglasses and a solar topee, has a camera and light meter slung around his neck, and he’s smoking a fat cigar. One’s sense of nostalgia (today’s desert rats just don’t look anything like that), along with the inevitable phallic resonance of a certain kind of cactus, are elegantly and wittily confirmed.

The most tantalizing, and to some extent frustrating, part of the book is the section of interviews with xerophile obsessives, frustrating only in the sense that it leaves you wanting much more. In there you’ll find tales of near-death experience from Joël Lodé, who suffered severe heatstroke on his first trip to the Mojave desert in 1984, and survived to risk his life in much the same way in New Mexico and Baja. He also went to Yemen at the height of the civil war to “photograph a plant.” I’m not sure what kind of plant that was, but I hope it was the Euphorbia abdelkuri discussed in a different interview with John Jacob Lavranos who hitched a ride with the British navy, across pirate-infested waters, to the island of Abd al-Kuri in 1967. (It’s part of Yemen, but closer to Somalia, hence the pirates.) Lavranos says that seeing the Euphorbia abdelkuri “was one of the highlights of my life. I’ll never forget it — coming up over the mountain and seeing those tall green candles, which, of course were Euphorbias that were centuries old.” Asked if he collected plants on the trip he replies, “Yes, of course. Every single Euphorbia abdelkuri in circulation came from that trip.” A little research reveals that they’re now extremely rare, both in collections and on the island.

Others are less interested in collecting than taxonomy, a fascinating and ultimately mind-boggling field that increasingly relies on molecular analysis. There’s an interview with a married couple, both botanists, named Giovanna Anceschi and Alberto Magli who say they have no desire for possession. Magli says,

For me, there’s nothing further from nature than a greenhouse. People put plants next to each other that would never, ever be seen together in nature. That’s fine for a fan. But not for a researcher, and I would venture to say that it’s part of the reason people continue to have confused ideas about the taxonomy of these plants.

The old wisdom was that there were about 175 genera and 2,000 species of cacti but the current thinking is that many of these are the same basic plant, achieving different forms because of different environments. Most of us amateurs would indeed welcome some clarification on the subject, and advice on how to identify obscure genera and species (the people who work in nurseries are seldom much help), but this pair really don’t put your mind at rest: “We eventually realized that many of the species you see in books don’t exist.”

If you want more detail, without an absolute guarantee of clarification, may I direct you to the activities of the International Cactaceae Systematics Group, a working party of the International Organization for Succulent Plant Study, which has been contemplating these matters since the mid-1980s? In fact there are many online cactus and succulent websites and groups. Few of them are quite as interesting or as obsessive as Xerophile, though I did come across the website for The Cactus Store which currently lists a Haageocereus tenuis for sale, yours for a cool quarter of a million dollars. They warn gravely, “This is not a statement piece, a collectors item, or a center piece for your garden. This is a critically endangered specimen plant for those familiar with ex-situ conservation who have a proper greenhouse setup.” Even in matters of obsession it’s good to know your limits.

¤

Geoff Nicholson is a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Review of Books. His latest novel is The Miranda.

The post Cactus Love: On “Xerophile: Cactus Photographs from Expeditions of the Obsessed” appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://ift.tt/2B9fkFQ

0 notes

Text

Semillas de cactus (cada paquete $14)

Cactus cantidad de semilla

1-Cleistocactus hyalacanthus 20

2-Cleistocactus baumannii 20

3-Harrisia pomanensis 20

4-Echinopsis aurea 25

5-Trichocereus terscheckii 15

6-Parodia massii 15

7-Parodia microsperma 25

8-Oreocereus celsianus 25

9-Gymnocalycium sp 40

10-Oreocereus leucotrichus 20

11-Trichocereus pasacana 35

12-Saguaro 10

13- Trichocereus volcanensis 35

14-Cereus forbesii 20

15-Notocactus submammulosus 10

16-Parodia weberiana 20

17-Trichocereus atacamensis 20

18-Echinopsis leucantha 40

19-Cleistocactus buchtienii 20

20-Stetsonia coryne 45

21-Echinopsis multiplex 20

22-Parodia chrysacanthion 10

23-Oreocereus trollii 15

24-Trichocereus sp 20

25-Gymnocalycium saglionis 40

26-Cleistocactus smaragdiflorus 20

27-Trichocereus thelegonus 25

28-Trichocereus huascha 20

29-Cereus monstruoso 20

30-Haageocereus pseudomelanostele 15

31-Mila caespitosa 10

32-Melocactus peruvianus 15

33-Notocactus leninghuasii 20

34-Frailea 10

35-Mammillaria prolifera 25

36-Echinocactus grusonii 15

37-Echinopsis mirabilis 15

38-Hylocereus undatus 25

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Lobivia huascha var. auricolor

Like so many cacti, this species has been bounced around from one genus to another for years (Helianthocereus, Trichoceres, Echinopsis, Lobivia). For a while, all these related genera were lumped into Echinopsis, but it turns out that doing this would necessitate including a host of other related genera as well, including Cleistocactus and Haageocereus. To avoid such a huge and unwieldy genus, Trichocereus and Lobivia were pulled back out of Echinopsis, but there still remained the problem of whether to consider huascha as a large Lobivia with elongated stems, or as a Trichocereus with colored flowers, rather than the usual white. For the time being, it is being put in with Lobivia. The species commonly has either yellow or red flowers, but the var. auricolor is more on the orange side of red. It is native to northwestern Argentina.

-Brian

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cactus: Haageocereus aureispinus

Book: Geïllustreerde cactus encyclopedie by Libor Kunte & Rudolf Subík

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haageocereus x Matucana Hybrid by Mex Hybrids.

MEX.2009.0339 Little Lolita (Haageocereus pseudoversicolor x Matucana huagalensis) x Matucana huagalensis L174.

#cactus#cacti#trichocereus#echinopsis#gardening#garden#plants#plant#hybrids#hybrid#flowerstagram#flowersofinstagram#flowerpower#flowers#flower#plantbook#plantes#planta#cactos#cactusflower#cactuses#succulents and cacti

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

instagram

Here's a little preview from my new stuff. Some gorgeous and very rare Trichocereus, Echinopsis, Lobivia and other intergeneric hybrids, e.g. Haageocereus x Matucana and Oreocereus x Chamaecereus. Only the goodest stuff. 🥰 #trichocereus #cacti #cactus #hybrid #hybrids #echinopsis #gardening #garden #plants #plant #seeds #plants #plant #cactusjerk #vlog #gardenblog #gardenvlog #blogger #blog #vlog #succulents #lobivia #pseudolobivia #flowers #flower #flowerpower #cactusflower https://www.instagram.com/p/B2FCp-eFRXe/?igshid=12zcjn62x5xej

#trichocereus#cacti#cactus#hybrid#hybrids#echinopsis#gardening#garden#plants#plant#seeds#cactusjerk#vlog#gardenblog#gardenvlog#blogger#blog#succulents#lobivia#pseudolobivia#flowers#flower#flowerpower#cactusflower

1 note

·

View note