#Henri d'Anjou

Text

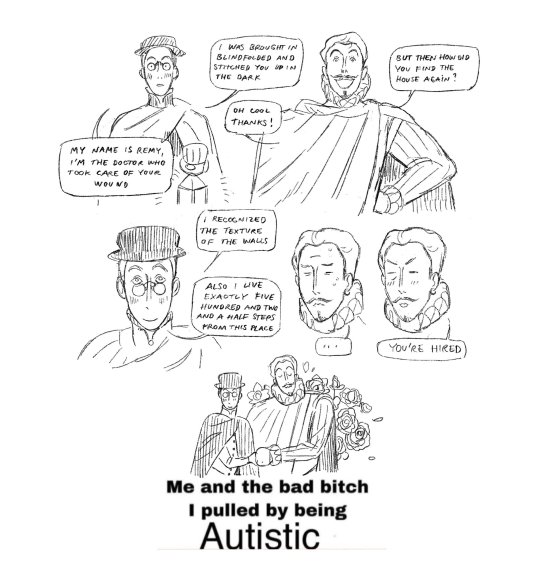

Silly stuff & memes from La Dame de Monsoreau chapters 1-12 :^D

#actual bits from the book mind you#la dame de monsoreau#alexandre dumas#trilogie des valois#henri III#louis de bussy d'Amboise#François d'Anjou#Chicot#remy le haudouin

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Loyal brothers

The Capetian kings found their brothers no more difficult than their sons. The exceptions were the brothers of Henri I, Robert and Eudes, but thereafter the younger Capetians developed a tradition of loyalty to their elders. Robert of Dreux, the brother of Louis VII, who was the focus of a feudal revolt in 1149, was only a partial exception, for at that date the king was still in the East, and the real object of the hostility was the regent Suger. By contrast, Hugh of Vermandois was described by contemporaries as the coadjutor of his brother, Philip I. St Louis's brothers, Robert of Artois, Alphonse of Poitiers, and Charles of Anjou, never caused him any difficulties, and the same can be said of Peter of Alençon and Robert of Clermont in the reign of their brother Philip III. Even the disturbing Charles of Valois, with his designs on the crowns of Aragon and Constantinople, was always a faithful servant to his brother Philip the Fair, and to the latter's sons. The declaration which he made when on the point of invading Italy in the service of the Pope is revealing:

"As we propose to go to the aid of the Church of Rome and of our dear lord, the mighty prince Charles, by the grace of God King of Sicily, be it known to all men that, as soon as the necessities of the same Church and King shall be, with God's help, in such state that we may with safety leave them, we shall then return to our most dear lord and brother Philip, by the grace of God King of France, should he have need of us. And we promise loyally and in all good faith that we shall not undertake any expedition to Constantinople, unless it be at the desire and with the advice of our dear lord and brother. And should it happen that our dear lord and brother should go to war, or that he should have need of us for the service of his kingdom, we promise that we shall came to him, at his command, as speedily as may be possible, and in all fitting state, to do his will. In witness of which we have given these letters under our seal. Written at Saint-Ouen lès Saint-Denis, in the year of Grace one thousand and three hundred, on the Wednesday after Candlemas."

This absence of such sombre family tragedies as Shakespeare immortalised had a real importance. In a society always prone to anarchy the monarchy stood for a principle of order, even whilst its material and moral resources were still only slowly developing. Respectability and order in the royal family were prerequisites, if the dynasty was to establish itself securely.

Robert Fawtier - The Capetian Kings of France

#xii#xiii#xiv#robert fawtier#the capetian kings of france#henri i#robert i de bourgogne#louis vii#robert i de dreux#abbé suger#philippe i#hugues de vermandois#louis ix#robert i d'artois#alphonse de poitiers#charles i d'anjou#philippe iii#pierre d'alençon#robert de clermont#philippe iv#charles de valois

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“As for her appearance, although a Milanese ambassador described Margaret as 'somewhat dark' for medieval tastes; he also praised her as 'a most handsome woman... wise and charitable' and the Norman chronicler Thomas Basin reported that at the time of the embassy's visit Margaret was 'a good-looking and well-developed girl... mature and ripe for marriage'. Margaret impressed the English envoys sufficiently that from her arrival in Tours on 4 May - it took only three weeks for the marriage with Henry to be agreed and effected.”

—JOHNSON, Lauren. “Shadow King: Life and Death of Henry VI”. P 196

#margaret of anjou#plantagenet dynasty#queen margaret#house of lancaster#henry vi#marguerite d'anjou#queen margaret of anjou#plantagenets#wars of the roses

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Where there any ideological differences between the Lancastrians and Yorkists (both the families and their supports)?

The Wars of the Roses was largely a dynastic struggle over the throne and royal patronage, but there were roots in earlier political struggles during the reign of Henry VI between what we could call a "war party" faction and a "peace party" faction.

Broadly speaking, the "war party" faction was led by people like Richard Duke of York and Richard Neville, and they tended to favor a continuation of the Hundred Years War, an alliance with Burgundy, disapproval of the King's marriage and the Queen's overly-active role in government, more royal efforts to improve law and order, and a crackdown on rampant corruption and favoritism that saw royal land distributed to court favorites, sapping royal finances.

Broadly speaking, the "peace party" faction was led by Margaret d'Anjou and her favorites like Somerset and Stafford. They tended to favor an end to the Hundred Years War, an alliance with France, obviously they favored the king's marriage and the Queen's active role in government, and they generally blamed problems in royal government on York's rebellious factionalism and emphasized that the royal prerogatives ought not to be questioned.

However, a lot of that stuff fell by the wayside once the fighting started - England couldn't really fight a civil war and war with France at the same time, Suffolk was dead, and efforts to deal with law and order, corruption, and royal finances would all have to wait until the fighting died down after Towton, and then again after Tewkesbury.

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

what did Catherine de Valois think of Margaret d'Anjou?

??????

Catherine died in 1437, around eight years before Henry VI married Margaret, so she could not have even met her, let alone have an opinion on her?

#ask#anon i'm happy to answer questions but you need to google basic facts before asking them to me lol

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

you said your fave film is queen margot. do you think it has feminist angle (i don't think so)? or you're enjoying it not despite but because of it?

It's absolutely not feminist in any way, i agree! And i do love it because of it. It's a grand opera full of gore and incest, thankfully not a single woke thing in sight. What's funny it's that it was supposed to be feminist! Script is cowritten by a man and libfem, in the 90s - they thought that making Margot the way she is, a men's willing plaything, is epitome of female liberation. Her extreme nymphomania caused by lifelong sexual assaults her brothers did to her, was presented as "independent woman making her own choices" can you believe it? You know i love incest trope and i do love it here, i romanticize, sexualize, fetishize and normalize it to my heart's content, but you seem to be asking in good faith so i have to be objective and call it what it is - they do abuse her. And throughout she stays side character in her own story. She loves her brothers too much and never gets mad at them for how they mistreat her, then gets mad once for her lover's capture but then immediately forgives, she's in some loyalty oath with her unwanted husband, she's changed woman after one night stand with a rando... too ridiculous to list everything. She would be liberated if she left all these men and paid them dust. But she didn't and i love to see this mess. They're all insane, good for them tbh. Her lust-story with La Mole i just skip, i don't care. They met like 5 times in total and each time they either sleep together or say some grandiloquent words for audience, they literally never get to know each other. One second of Cath and Henri d'Anjou interaction has more romance in it than entire Margot/La Mole 'relationship'. Then there's making huguenots as always victims. Yes, they are unlikable, but that's as far as "greyness" of these characters goes. In reality at that moment of time protestantism was new, dangerous, militant heresy spreading like wildfire. Noone was born in it, Henri de Bourbon was born catholic and later converted. Everyone was changing faiths a few times a year depending on benefits of the moment. Huguenots were slaughtering catholics and committing atrocities, many small-scale "St.Barthelemy's nights" were done by huguenots against catholics, their leader called for burning catholics at stake. In mixed-religion cities they constantly were terrorizing catholic population, raping, pillaging, killing people and committing sacriledge. They wanted their own laws and disobeyed the king. They were constantly rebelling and not once tried to kidnap the king. Their leaders were selling their country to germans, while catholic league's leaders were selling it to spanish. And last, but not the least, they did have an army outside Paris' walls, and after Coligny got shot some of huguenot nobles had the nerve to threaten Catherine if justice is not served. To serve justice meant to punish Guise, who was worshipped by common people of Paris so if he was arrested Paris would rebel. To paint huguenots as 'victims of oppression' was quite a choice. But it's not based on history, it's based on Dumas' novel so i should not be doing all this pointless nitpicking in the first place. I love this film to the point of obsession because it never misses an opportunity to go crazy, everything is amplified to insane degree, i rewatched it many times and i enjoy it because of its insanity.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://at.tumblr.com/navree/ive-heard-that-grrm-has-based-tdod-on-the-anarchy/ejgsdhmtceax

If grrm just has made the dance between Viserys and Rhaenys it would be much mor similar to the Anarchy , because in this situation we will have Cousins against each other, also Viserys is very similar to Stephen and Rhaenys like Matilda is the only child and heir of her father . I've never understand why grrm decided to base Aegon on Stephen, they're nothing alike

Aegon ii could be similar to Henry vii or prince hal but Stephen? I doubt it

I think he just read about a situation and then mapped his own characters onto it, while also further muddying the waters. Tyrion is likely meant to be vaguely analogous to Richard III in the main series, but there's some key differences in the story itself (Richard III was certainly not Marguerite d'Anjou's brother and the situations were incredibly different), as well as the fact that Tyrion and Richard are nothing alike personality wise. I think that's the extent of his "basing", especially when it came to Westeros's fictional history, which is a lot less detailed than the series and required less character development because it's an in-universe history book, not a proper narrative.

#personal#answered#anonymous#the tyrion and richard thing is something i can be incredibly motor mouthed on

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rivalité de François Iier et de Charles-Quint /

M. Mignet.

Description

Tools

Cite thisExport citation fileMain AuthorMignet, (François-Auguste-Marie-Alexis), M. 1796-1884.Language(s)French PublishedParis : Didier, 1875.

SubjectsCharles > Charles / V, > Charles / V, / Holy Roman Emperor, > Charles / V, / Holy Roman Emperor, / 1500-1558

Francis > Francis / I, > Francis / I, / King of France, > Francis / I, / King of France, / 1494-1547.

Holy Roman Empire > Holy Roman Empire / History > Holy Roman Empire / History / Charles V, 1519-1556.

France > France / History > France / History / Francis I, 1515-1547.

History

Physical Description2 v. ; 23 cm.

both volumes found in Harvard Library

Etat politique de l'Italie etde la France vers la fin duquinzième siècle . Droit desuccession au royaume deNaples et au duché deMilan , ré clamé par CharlesVIII , comme héritier de lamaison d'Anjou et par LouisXII comme héritier directdes Visconti . Expédition deCharles VIII en 1494.-Conquête rapide et pertenon moins prompte duroyaume de Naples .Avénement au trône deLouis XII , qui prend le titrede duc de Milan et de roi deNaples . - Invasion , en1499 , de la Lombardiemilanaise , concertée avecles Vénitiens , qui étendentleurs possessions de terreferme jusqu'à la rive gauchede l'Adda . — Louis XII ,affermi dans le duché deMilan , suit une dan gereusepolitique en agrandissantdans l'Italie centrale lapuissance territoriale despapes Alexandre VI et JulesII , et en introduisant tour àtour dans l'Italie inférieure leroi Ferdinand d'Aragon , etdans la haute Italiel'empereur Maximilien . —(13, 1)

Accord , en 1501 , des roisLouis XII et Ferdinandd'Aragon pour conquérir etpartager le royaume deNaples , qui reste pris toutentier par Ferdinand , en1503 . - Ligue de Cambrai ,en 1508 , entre Louis XII ,l'empereur Maximi lien , leroi Ferdinand , le pape JulesII , qui dépouillent de leurspos sessions italiennes lesVénitiens vaincus à labataille d'Agnadel . —Sainte Ligue qu'ourdissent ,en 1511 , contre Louis XII ,le pape Jules II , le roid'Aragon et de NaplesFerdinand , le roi d'Angleterre Henri VIII , quesecondent les troupes descantons suisses et àlaquelle se joint l'empereurMaximilien pour expulserles Françai

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Étienne de Blois, roi d'Angleterre

Le roi Étienne d'Angleterre, souvent appelé Étienne de Blois, régna de 1135 à 1154. Son prédécesseur Henri Ier d'Angleterre (r. de 1100 à 1135) n'avait pas laissé d'héritier mâle et le successeur qu'il avait désigné, sa fille l'impératrice Mathilde, n'était pas du goût de nombreux barons puissants qui préféraient Étienne, l'homme le plus riche d'Angleterre et neveu d'Henri Ier. Une guerre civile intermittente s'ensuivit au cours des quinze années suivantes entre les deux camps, tandis que la couronne anglaise perdait le contrôle de son territoire en Normandie ainsi que des terres au profit de l'Écosse et des princes gallois. Étienne était le dernier des rois normands, une lignée commencée par son grand-père Guillaume le Conquérant en 1066. Henri II d'Angleterre (r. de 1154 à 1189) lui succéda, ce qui est ironique, compte tenu de la guerre civile précédente, car il était le fils de Mathilde et du comte Geoffroy V d'Anjou.

Lire la suite...

0 notes

Photo

“Henry II was crowned at Westminster Abbey on December 19, 1154, with a heavily pregnant Queen Eleanor sitting beside him. Judging by her near-constant state of pregnancy and childbirth, which contrasted sharply with her time as queen of France, Eleanor had thrown herself enthusiastically into establishing a royal dynasty with Henry.

The elderly archbishop Theobald of Canterbury performed the sacred ceremony, and the great bishops and magnates of England looked on. Henry was the first ruler to be crowned king of England, rather than the old form, king of the English. And the coronation brought with it a spirit of great popular optimism.

‘Throughout England, the people shouted: ‘Long live the King’’, wrote William of Newburgh. ‘[They] hoped for better things from the new monarch, especially when they saw he possessed remarkale prudence, constancy and zeal for justice, and at the very outset already manifested the likeness of a great prince’.

Henry’s coronation charter addressed all the great men of the realm, assuring them that he would grant them all the ‘concessions, gifts, liberties and freedoms’ that Henry I had allowed and that he would likewise abolish evil costums.

He made no specific promises, and unlike his predecessor Stephen, he did not hark back to the ‘good laws and good costums’ enjoyed by English subjects in the days of Edward the Confessor. But the charter mentioned specifically Henry’s desire to work toward ‘the common restoration of my whole realm’.

England found its new twenty-one-year-old king well educated, legally minded, and competent in a number of languages, although he spoke only Latin and the French dialects. He struck his contemporaries as almost impossibly purposeful, hunting and hawking and sweeping at a headlong pace through the forests and parks of his vast lands.

Gerald of Wales described him as ‘addicted to the chase beyond measure; at crack of dawn he was often on horseback, traversing wastelands, penetrating forests and climbing the mountain-tops, and so he passed restless days. At evening on his return home he was rarely seen to sit down, either before or after supper...[H]e would wear the whole court out by continual standing...’ (...)”

Dan Jones, “The Plantagenets. The Warrior Kings and Queens Who Made England.”

Fan Cast: Tom Hiddleston as King Henry II.

#Henry II of England#King Henry II#Henry II#Henry FitzEmpress#Henri d'Anjou#Henry of Anjou#Angevin Empire#Angevin Emperor#House of Plantagenet#Plantagenet Dynasty#The Plantagenets#dan jones#Tom Hiddleston#Gerald of Wales

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

This museum identified this ivory plaque as Margaret of Anjou.

#margaret of anjou#marguerite d'anjou#middle ages#medieval#fifteenth century#i don't know of this is accurate#shredsandpatches#henry vi

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

King Henry of Valois.

#royaume de france#full length portrait#maison de valois#duc d'anjou#henri iii#roi de france#vive le roi#full-length portrait#Z Bożej łaski król Francji i Polski#Henryk Walezy#Walezjusze#król polski#królestwo polskie

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Expansion of the royal domain

The way in which the kingdom was ruled in its different provinces had always varied according to the degree that power had been permanently or temporarily devolved to apanage princes and great nobles or that representative assemblies continued to function. It is therefore axiomatic that there was no 'system of government' in the France of the Renaissance. The question is: was there a tendency for the kingdom to become more centralised? R. Bonney has wisely cautioned against the over-use in French history of the term 'centralisation', a term coined in 1794. The main distinction drawn in the early modern period, as Mousnier made clear, was that between the king's 'delegated' and 'retained' justice, the latter covering all the public affairs of the kingdom in which the crown was supreme and the former the private affairs of his subjects. No one would pretend, however, that a clear line of division was ever established between the two.

If we consider the case of the apanages and' great fiefs, for instance, the century from the reign of Louis XI is usually considered definitive in their suppression. In 1480, there were around 80 great fiefs. By 1530 around half of these still existed. The rest were in abeyance or held by members of the royal family. Within the royal house, the apanage of Orleans was reunited to the crown on the accession of Louis XII, although thereafter used periodically for the endowment of the king's younger son, permanently so after the reign of Louis XIV. The complex of territories held by the Bourbon and Bourbon-Montpensier families fell by the treason of the Constable in 1523. Burgundy (and temporarily Artois and Franche-Comté) were taken over in 1477. Among the great fiefs, the county of Comminges was united to the crown on the death of count Mathieu de Foix in 1453, the domains of the Armagnacs (such as the county of Rodez) were confiscated on the destruction of Jean V at Lectoure in 1473. They found their way by the reign of Francis I into the hands of the royal family, through the marriage of Jean V's sister to the count of Alençon. The last Alençon duke, Charles, married Francis I's sister, Marguerite of Angoulême, and Alençon's sister, Françoise, married duke Charles of Vendôme, grandfather of Henry IV. Brittany was acquired through war and marriage alliance in the 1490s, Provence and the domains of the house of Anjou after the death of king René and then of Charles d'Anjou in 1481. The archives of the Chambre des comptes of Anjou for the early 1480s give ample evidence of the king's determination to exploit his new acquisition as soon as possible.

It should not be assumed that the crown pursued a consistent determination to lay hands on all these territories and rule them directly. There was usually a more or less lengthy period of adjustment to a new status. Some apanages and territories taken over by Louis XI were absorbed into the general administration of the rest of the kingdom. This was clearly the case with Burgundy and Picardy-Artois in 1477, both of them in the area under the jurisdiction of the Parlement of Paris. Yet even here, Louis XI had to tread warily in winning over the support of the regional nobility and discontent was apt to break out until the end of the fifteenth century. On Louis's death, for instance, a rising occurred in Picardy at Bertrancourt near Doullens, with cries of 'there is no longer a king in France, long live Burgundy!' The absorption of Artois proved to be an impossible undertaking and had to be renounced in 1493.

Elsewhere, absorption of apanages that were distant from the centre of royal power left affairs locally much as they had been before. The little Pyreneen county of Comminges was governed much as it had been under its counts, with privileges confirmed by Charles VIII in 1496. Only with the work of royal commissioners in the tax-assessing process in the 1540s, the first time an outside power had actively intervened in the affairs of the local nobility, did this begin to change. Auvergne, an apanage raised to a duchy in 1360, was confirmed to the Bourbons in 1425 on condition that their whole domain became an apanage. The duchy was confiscated from the Constable in 1523 but transferred by the king to his mother in 1527 and only absorbed into the royal domain in 1531. Even after that, it formed the dower of Charles IX's queen and then part of the apanage of François d'Anjou, his brother. In the contiguous county of Forez, also confiscated in 1523, little local opposition emerged to the change of regime; although the local chambre des comptes was shortly suppressed, most local judicial officials, along with the entire administrative structure, were retained. Except for a few partisans of the Constable, it seems that there was no great upheaval. Louise de Bourbon, the Constable's sister and princess of La Roche-sur-Yon, demanded a share of the inheritance - Forez, Beaujolais and Dombes. Beaujolais and the principality of Dombes eventually went to Louise's son, Montpensier.

The county of Auvergne, enclaved in the duchy, was held by the duke of Albany in his wife's name, and was then inherited from the last of the La Tour d'Auvergne family by Catherine de Medici. Catherine brought it to the crown by her marriage with Henri II in 1533 but she continued to administer it as her own property. She left it to Charles IX's bastard, Charles de Valois, but her daughter Marguerite made good her claim to it in 1606 and it only entered the royal domain definitively when she willed it to Louis XIII.

After her marriage to Charles VIII in 1491, Brittany was administered as her own property by queen Anne, technically still duchess but in reality sharply circumscribed in her power, until her husband's death restored some of her freedom of action in 1498. Having already established friendly relations with Louis XII when he was still duke of Orleans, she was prepared to accept his offer of marriage after the annulment of his marriage to Louis Xl's daughter, Jeanne, had been agreed. The contract which accompanied the marriage in January 1499 tied the duchy to the crown provisionally on condition that it always passed to the second son of the marriage, while in the absence of issue the duchy was to revert to Anne's heirs on her own side. Anne was able to act rather more independently during her marriage to Louis XII though the conditions of the contract were not observed. On her death Brittany was inherited by her elder daughter Claude, wife of Francis I, who transmitted her rights to her son the dauphin. The queen had, however, transferred the government of the duchy to her husband in 1515 and he continued to rule it in the name of his son François on Claude's death, entitling acts as 'legitime administrateur et usufructuaire' of his son's property. When the dauphin's majority in 1532 brought the question of the imminent personal union of the duchy to the kingdom to the foreground, it was arranged for the Breton estates to 'request' full union with France but on terms which guaranteed Breton privileges and maintained the principle that the dauphin would be duke of Brittany. Only in 1536, on the death of the dauphin, was the union with the kingdom complete and no more dukes were crowned at Rennes. What had been done was the annulment of the Breton succession law, which included females, in favour of the French royal succession law. Late in 1539, it was decided that the new dauphin Henri would have the government of Brittany 'to govern as he pleases', though the documents were delayed by the king's illness. A 'Declaration' transferring Brittany to Henri was drawn up in 1540. In practice, the government of the duchy seems not to have been much changed.

The lands of the house of France-Anjou posed a complex problem. René of Anjou, titular king of Jerusalem, Sicily, Aragon and Naples, was count of Provence in his own right, of Maine and Anjou as apanagiste and Guise by succession. As early as 1478, Louis was scheming to ensure that king René, who had no surviving son, did not leave his territories of Anjou, Provence and Bar to his grandson, René II of Lorraine, warning the general of Languedoc that his region would be 'destroyed' if Provence fell into other hands. On the 'good' king's death in 1480, most of his domains passed to his cousin Charles IV d'Anjou, count of Maine, who died childless in 1481, when Maine and Anjou reverted to the crown, thereafter to be granted out to members of the royal family such as Louise of Savoy. At the same time Provence was acquired by Louis XI by Charles IV's will and the county of Guise was disputed between the houses of Armagnac-Nemours, Lorraine (heirs of René I of Anjou and successors as titular kings of Jerusalem and Sicily) and Pierre de Rohan, marshal de Gié. From 1481, however, the king ruled in Provence as 'count of Provence and Forcalquier'. The lord of Soliès, Palamède de Forbin, who had persuaded Charles d'Anjou to leave the county to the king, was rewarded with the post of governor. The major change came in 1535 with the edicts of Joinville and Is-sur-Tille on the government of Provence, limiting the scope of the old institutions of the Estates and the Sénéchal and increasing that of the Parlement of Aix in justice and of the royal governor in administration. Curiously, Francis I was reported as having said that he felt an obligation to 'ceux de Guise', the house of Lorraine in France, since Louis XI had despoiled them of their inheritance of Provence and Anjou.

The major surviving complex of apanage lands by the middle of the sixteenth century was that held by Antoine de Bourbon, now first prince of the blood and next in line to the throne after the immediate royal family, and his wife Jeanne d'Albret. These involved a group of territories held by different tenures. The Albret inheritance brought the titular kingship of Navarre with a small fragment of the ancient kingdom of Navarre north of the Pyrénées that was held in sovereignty. In the counties of Foix, Albret and Béarn, the family held effective sway under only the most distant royal sovereignty, though Louis XI saw fit to pose as the protector of the young François-Phébus in 1472. In 1476, he sought to revise local tariffs against Albret interests and in 1480 attempts to levy a taille for the gendarmerie there stirred up a rebellion. In western France, the duchy of Vendôme, erected as late as 1515 to detach it from dependence on the duchy of Anjou, was held as an apanage under rather closer royal supervision. In the north, the complex of lands administered from La Fère-sur-Oise and centring the county of Marle was held directly of the king or of the Habsburg ruler of the Netherlands, rendering the family, to some, unreliable. Practical power stemmed from the holding of the governorships of Picardy and of Guyenne by the Bourbons and Henri d'Albret.

Other independent territories persisted, such as the vicomté of Turenne, where the vicomte (of the La Tour d'Auvergne family) ruled with regalian rights until the eighteenth century, could raise taxes, coin money, make war and render justice as a limited monarch in conjunction with very active local estates.

David Potter - A History of France, 1460-1560- The Emergence of a Nation State

#xv#xvi#david potter#a history of france 1460 1560: the emergence of a nation state#louis xi#louis xii#charles iii de bourbon#mathieu de foix#jean v d'armagnac#françois i#charles iv d'alençon#marguerite d'angoulême#rené d'anjou#charles viii#charles ix#élisabeth d'autriche#louise de bourbon#gilbert de montpensier#catherine de medici#house of la tour d'auvergne#charles de valois#louis xiii#anne de bretagne#jeanne de france#claude de france#charles iv d'anjou#louise de savoie#house of guise#capetian house of bourbon#antoine de bourbon

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

23 March 1430: Marguerite d'Anjou is born at Lorraine, France. She later became Queen of England by marrying King Henry VI.

#house of lancaster#happy birthday to margaret of anjou#marguerite d'anjou#margaret of anjou#queen of england#house of anjou#plantagenet dynasty

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

If Shakespeare was a Tudor propagandist, why are the Lancastrians, especially the Beauforts, who are the maternal ancestors of the Tudors, depicted so badly in Henry VI?

Well, keep in mind that the legitimacy of the Tudors rested as much or more on the legitimacy of the Yorkist through Elizabeth of York as it did on Henry VII's shaky claim - as far as the Tudors were concerned, the conquering boy-king Edward IV and his children were very much the rightful monarchs of England and had to be portrayed that way, with Richard III singled out as the illegitimate usurper.

Also, I don't thinnk the Beauforts come out particularly bad in Shakespeare among the Lancastrians, especially compared to Margaret d'Anjou.

22 notes

·

View notes

Quote

And on the Monday after noon the Queen came to him, and brought my Lord Prince with her. And then he asked what the Prince's name was, and the Queen told him Edward; and then he held up his hands and thanked God thereof. And he said he never knew him till that time, nor wist not what was said to him, nor wist not where he had be whiles he hath be sick till now. And he asked who was godfathers, and the Queen told him, and he was well apaid.

Edmund Clere to John Paston I, 9 January 1455 (Firsthand description of Henry VI's meeting his infant son for the first time after coming out of his "catatonic state" [unknown illness which remains a mystery])

#The Paston Letters#I love reading other people's mail#Especially when it gives me adorable tidbits about Henry VI meeting his baby son#Henry VI#Queen Margaret#Margaret of Anjou#Marguerite d'Anjou#Edward of Westminster#Edward of Lancaster#Edward Prince of Wales#Edmund Clere#John Paston I#9 January 1455

15 notes

·

View notes