#Hilditch & Key Paris

Text

Interview with me up at Les Indispensables

A rare shoot (including these Anthony Delos custom boots) and interview with me is now up in both English and French at Les Indispensables Paris, at

https://www.lesindispensablesparis.com/fashion/interview-obeyfeline

and in French at

https://www.lesindispensablesparis.com/mode/interview-obeyfeline

And for more, my book - the only one of its kind about Paris menswear and elegance, is available at the link in my bio.

#swansongsrjdm#Reginald-Jerome de Mans#steez#menswear#elegant#Swan Songs: Souvenirs of Paris Elegance#Arnys#Hilditch & Key Paris#Hilditch et Key#Hermes#Anthony Delos#custom#bespoke#bottier#grande mesure#made in France#Paris fashion#men's style book

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

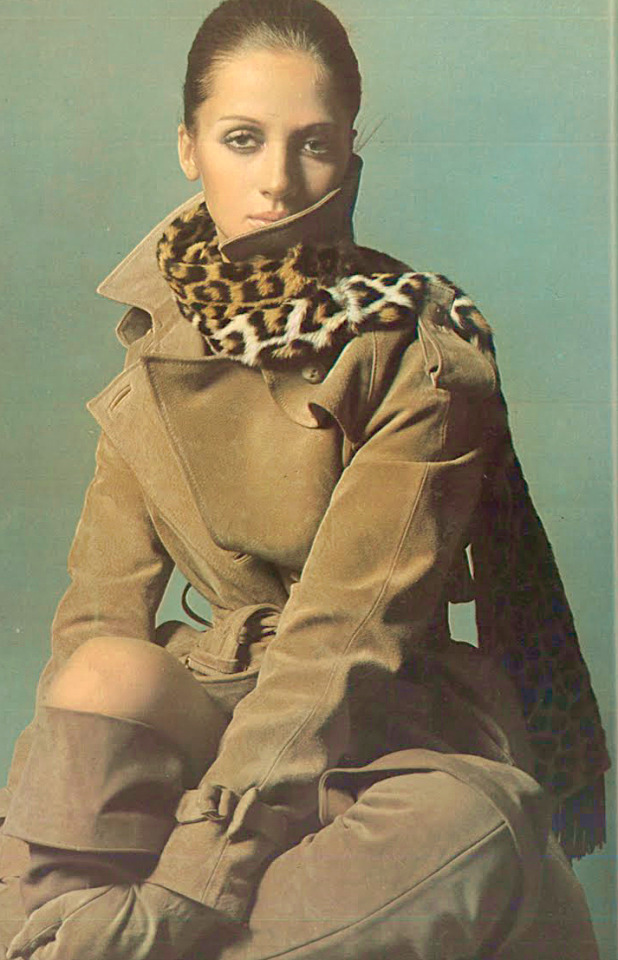

Vogue Paris November 1968 "Les Frileuses Toutes en Cuir" Model: Ingmari Lamy Photographer: Guy Bourdin

#vogue paris 1968#ingmari lamy#guy bourdin#60s Fashion#swinging sixties#fall/winter#all leather#revillon#mc douglas#cashmere scarf#hilditch & key#lined gloves#dior gloves#wrap skirt#thierry chardin#trenchcoat#cuffed boots#lambskin boots#coty makeup#guerlain makeup#frock coat

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Philippe Noiret. Enfant turbulent, Philippe Noiret se fait renvoyer avec régularité, de tous les établissements scolaires qu'il fréquente. Il rate son bac mais découvre le théâtre et démarre dans les années 1950 sa carrière avec la troupe du TNP de Jean Vilar ou il joue au côté de Gérard Philippe. C'est son père qui lui donne le goût des beaux vêtements, des étoffes luxueuses et surtout des mots. Vers quinze ans, il lui chipe costumes et chemises et attrape le virus des beaux souliers auxquels il vouera un véritable culte. « Mon père, qui était très élégant, avait un bureau rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré et, jeune, je passais tous les jours devant chez Lobb. » M. Dickinson le maître bottier de chez Lobb, créera la première paire de mocassins pour l'acteur qui s'offrira une paire de souliers par an. Avec le temps, le goût de Noiret s'affirme. Il se fait faire de magnifiques derbies à boucle au « jointé chair » (couture du cuir dont très peu d’artisans maîtrisent la technique) et le modèle William créé pour le fils de John Lobb dans les années 1940 en cuir ardilla. Ses chaussons d'intérieur sur mesures, sont en velours, ses initiales brodées au fil d’argent. Au festival de Cannes en 2000, ce modèle sauvera la mise de l'acteur qui a oublié ses souliers vernis à Paris. Noiret est fidèle à ses fournisseurs et devient ami avec eux. S'il s'habille parfois à Rome ou à Londres (Anderson and Sheppard), c’est à Paris qu'il a ses habitudes. Chez Arnys, chez Charvet. Il aime les accessoires : les nœuds papillons, les casquettes de chez Gelot et les foulards en soie de chez Hilditch and Key. « Pour former un tout, un costume doit être fini par un chapeau. » Il ose d’audacieux mélanges, comme Fred Astaire qu'il admire, mais ne transige jamais sur certains principes, un costume croisé porté avec des mocassins est pour lui une faute de goût impardonnable « Le voyage est court autant le faire en première classe ! » #daniellevychemisier #philippenoiret #icone #àlafrançaise Merci @ze_french_do_it_better pour ce texte. https://www.instagram.com/p/CeoZnoiMa2C/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Karl Lagerfeld#Cifonelli#pensées#reflexion#Hilditch and Key#Paris#France#fashion designer#vintage#80s#sunglasses#pose#portrait#bed

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

When Karl Lagerfeld died, in February, “fashion and culture lost a great inspiration,” Bernard Arnault, the C.E.O. and chairman of L.V.M.H., said. A handful of businesses in Paris also lost a major patron, a one-man stimulus package who for decades had primed their margins and their creativity. The Lagerfeld District: a quilted clutch of bonnes adresses along the Tuileries and the gardens of the Champs-Élysées, not far from the headquarters of Chanel, where he was the creative director. The collapse of the Lagerfeld economy wasn’t catastrophic—Colette, one of his favorite boutiques, had already closed, in 2017—but his absence continues to be felt on shop floors around the city’s central arrondissements. “Karl liked to say that he was eleven per cent of our business,” Danielle Cillien Sabatier, the director of Galignani, the bookshop on the Rue de Rivoli, said the other day. When a visitor asked if the figure was accurate, she didn’t correct it. “He was certainly our No. 1 client.”

Lagerfeld went into Galignani once or twice a week. In a replica of his office that he once exhibited, shopping bags from the store cover every surface. “Once, we changed colors, from dark blue to light blue, and Karl said, ‘Oh, it’s the blue of Lanvin,’ ” Sabatier recalled. “I said, ‘No, it’s the blue of my eyes.’ ” An author and publisher himself, Lagerfeld was a bibliophile of epic appetite. (Practically a bibliophage, he is said to have torn the pages out of thick paperbacks as he read them.) He bought French books, English books, books of poetry, signed books, first editions, monographs, everything he could find on the Wiener Werkstätte. “Our booksellers knew the themes of his fashion shows long before they happened,” Sabatier said. “Sometimes we were thinking, This is awkward, what is he preparing? He’d buy dozens of books on astronauts, and, months later, there’d be a rocket at the Grand Palais.”

“Karl Kaiser,” the French journalist Raphaëlle Bacqué’s biography of Lagerfeld, has been a recent best-seller at Galignani. Near the fine-arts desk, there is a little shrine to him: a framed portrait, a photograph he took of a model posing in front of the shop’s windows. He might have been a monster boss (“I have no human feelings,” he once claimed), but he was apparently a peach of a customer. “He was very nice to everyone,” Sabatier said, pointing out another framed photograph, of Lagerfeld’s blue-cream Birman cat, Choupette, her head poking out of a Galignani bag. Lagerfeld had shot it for a window display and then given it to Sabatier for her office. She and several of her colleagues attended his memorial service. “I think it was real luck to come across such an incredible personality, and to see him in such simple conditions,” she said.

A few doors down, at Hilditch & Key, shirtmakers since 1899, Philippe Zubrzycki, the store’s manager, lit up when Lagerfeld’s name was mentioned. Monsieur Lagerfeld, he said, ordered around a hundred and fifty made-to-measure garments a year: nightshirts, kimonos, the white button-downs with collars like neck braces that had been his signature look since he lost ninety-two pounds over the course of a year by drinking protein shakes and eating nothing after 8 p.m. “He also ordered sleeveless ones, for painting,” Zubrzycki said. A client of long standing, Lagerfeld had cycled through different looks. At one point, when he was spending time at a château in Brittany, he had a taste for billowing shirts made in taffeta. “Sometimes he’d put in an order for fifty pieces and, over the weeks, the order would grow,” Zubrzycki said, acknowledging that Lagerfeld’s patronage was “fairly consequential.” Lagerfeld sent sketches for his orders by fax or courier, but he was open to suggestions from Hilditch & Key’s salespeople and tailors. “He loved when we made propositions, and often he’d say, ‘Oui, bingo!’ ”

Lagerfeld’s florist was Lachaume, a hundred-and-seventy-five-year-old family business on the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, where Marcel Proust went each morning to purchase an orchid for his buttonhole. Caroline Cnocquaert and Stéphanie Primet, its sister proprietors, responded immediately to a reporter’s invitation to talk about Lagerfeld, writing, “With great pleasure, he was our dream client!” The first time Lagerfeld came into the shop, in 1971, he bought “a very beautiful big white rose” from their grandmother, Giuseppina. An hour later, the sisters recalled, Yves Saint Laurent showed up, asking their mother, Colette, for exactly the same flower. When iPhones came out, Lagerfeld gave one to each sister, so that he could send them texts and images (“That was his word, rather than saying ‘photos’ ”). He hated holidays, when his ateliers were closed, and would take advantage of the fact that Lachaume stayed open, sending messages or coming in to chat. Cnocquaert and Primet had been very sad when Lagerfeld died, but, they said, “let’s think of the future, that’s what Monsieur Lagerfeld did.” They’d have their memories, they said, of his incredible orders. “We created thousands of bouquets!” ♦

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

KARL LAGERFELD, 1933-2019

by Réginald-Jérôme de Mans

His appearance, for the last forty years of his life, was alien, mannered, armored by various styles of outfit that were less uniforms than the carapace of some unique extraterrestrial being. It was this persona, behind gently waving fans, knuckle-length gloves, heavy-looking Chrome Hearts jewelry, that made him such a memorable media figure. An unforgettable bowsprit, rather than figurehead, for the many different fashion houses he designed for – at times creating collections simultaneously for Chanel, Fendi, Chloé and his own Lagerfeld label, among others.

The energy and inspiration this must have taken also seemed inhuman. He appeared to be the hardest working man in #steez (with apologies to Isle), maintaining an active career as a photographer (with a gallery among the other dealers in Saint-Germain-des-Près) in addition to all of his design work. He professed to voraciously devour various other forms of media, supposedly tasking someone to maintain dozens of iPods fully loaded with different music in the early part of this century.

Adding to his alienness was his constant obfuscation about his age, and about his privileged but bourgeois origins. On reflection, perhaps that reluctance to own up to his realities made him more relatable. He was 85.

In fact, Alicia Drake’s The Beautiful Fall, about the rivalry of Lagerfeld and his fellow 1954 Woolmark Prize laureate Yves Saint-Laurent makes Lagerfeld out to be by far the more human and sympathetic of the two. Those who knew him personally reported that he was kind, personable, charming and funny, as well as as intellectually curious as his public persona.

Looking back, he almost never lacked a knowing ability to satirize himself: posing for a public safety announcement in a now infamous yellow vest (required to be carried in a car for road safety reasons) marring his otherwise immaculate high-collared bespoke Hilditch & Key Paris shirt and Dior Homme suit with the caption “It’s ugly, it goes with nothing, and it could save your life”; or publicizing Steiff’s Karl Lagerfeld teddy bear (both the bear’s deadpan expression and outfit matched his); or adopting a fluffy Persian cat, the iGent’s spouse. He even later said that he wished he could marry it, and has left a sizeable part of his fortune to it.

His words, though, could depart from self-aware high camp to the inhuman and inexcusable, covering the usual bigot bases from xenophobia and latent anti-Semitism (such as “One cannot – even if there are decades between them – kill millions of Jews so you can bring millions of their worst enemies in their place”), to his own industry’s sexual exploitation (suggesting any woman who didn’t want her “pants pulled about” instead “join a nunnery”) to a harsh phobia of fat or indeed just “curvy” women. It is better to evoke and remember than to eulogize. No pretended or adoptive persona can excuse his insistent repetition of invective on these topics.

Not at all unexpected, though quite ironic, too, that he so persistently attacked the fat (among other things blaming them for the depletion of the French social safety net), given that over his career he morphed from a bodybuilder in a Caraceni suit (he abandoned Cifonelli several generations before the current tailors) to a fat person himself in a Japanese designer muumuu. His willingness to satirize his image didn’t extend to his own weight. Those bizarre smocks did nothing to conceal it. The fan and the dark sunglasses he started sporting only drew attention to a self-consciousness about his own aging body, as did his powdered hair. In the early 2000s, he lost a substantial amount of weight, announcing that he did so in order to wear the new slim Dior Homme suits designed by Hédi Slimane. He even wrote a diet book along with his doctor, containing that rationalization along with a host of rigorous recipes that required a personal chef, as well as a willingness to eat certain special protein packets. No doubt his fat-shaming words since then presumed that everyone had willpower, means and opportunities similar to his. Those tight suits, with baroquely high-collared, miter-cuffed custom shirts from H&K Paris, boots, and the jewelry, remained his public uniform until his death. He referred to them on occasion as an armor.

His sensitivity about his weight and his acknowledgment that in his favorite clothing he felt protection are to me his most human qualities. He admitted that his shades, his high collars (which served the same neckfold-obscuring purpose as his fans had), his ornate shirtfronts and sharp boots had all been part of an artifice, to distance the casual onlooker or the stranger. No doubt he thought that his public quips and proclamations, no matter how offensive, were also facets of that distancing persona. But he found security in his clothes, they functioned as expressions of self, he even forced himself through a typically inhuman diet to lose weight in order to be able to wear them as a manifest of self. Who among us – presuming we all enjoy clothes, because you’re reading this – has not also felt that same completion and empowerment in wearing a favorite set of clothes, a favorite armor against the depredations of the day, whether veldtschoen boots the snow and wet just slide off of, or the suit, shirt and tie whose fit and cut make us feel that much closer to invulnerable no matter who’s across the table?

In that way, not only was his artifice – his public oral and sartorial persona – part of his art, but it became indissociable from his true person, however privately warm and kind he was. And as such, even if some argue that his offensive public opinions were simply a function of the industry he helped create and his time, he was, despite his interesting superficial alienness, a man of his time, of our admittedly appalling time. May men of other times be as original – and yet also conscious of their humanity, and better.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adam, la revue de l'homme

Hormis le blog américain A Continious Lean, nous avons étonnement trouvé peu de contenu concernant la revue pour homme Adam. Elle mérite pourtant qu’on s’y attarde, ne serait-ce que pour ses splendides couvertures. Fondée par Edmond Dubois en 1925, la revue Adam fût publiée environ tous les deux mois jusqu'en 1973. Elle regorge de publicités (les 20 premières pages), de conseils de style et de reportages sur la vie parisienne et plus largement européenne.

Le magazine a travaillé avec de nombreux illustrateurs dont le célèbre peintre frano-italien René Gruau. On peut également citer Pierre Mourgue, Hof ou Garretto. Nos couvertures préférées ont été publiés entre 1940 et 1960.

CONTENU

C’est en lisant le livre Des modes et des hommes: deux siècles d'élégance masculine de Farid Chenoune que nous avons découvert ce magazine. Farid Chenoune y fait référence à quelques reprises, suffisamment pour éveiller notre curiosité. En parcourant une dizaine de numéros, nous n’avons pas été déçu. Les publicités valent le détour, les conseils vestimentaires sont intéressants et le style d’écriture incisif. On se rend très vite compte que, si la mode masculine a beaucoup évolué, rien n’a vraiment changé. Les questions de fond restent les mêmes.

Parmi les publicités marquantes, celle des années 40 donnant le liste de 20 grands tailleurs parisiens et 11 chemisiers créateurs de Paris.

Les 20 tailleurs sont : Carette, Clément et brunet, Delout, Debacker, Cumberland F.Disslin, Kniez, Harrison, Creed, Puissegur, Paul Portes, Kriegck Rabau, Lanvin, Larsen, Voisin Lus et Befve, O’Rossen, James pile, Roger Pittard, Regoly, Hase-Pappel.

Les 11 chemisiers sont : Boivin Jeune, Charvet, David, Doucet, Doucet Jeune, Edouard et Butler, Hilditch and Key, Knize, Lanvin, Sulka et Washington Tremlett.

A notre connaissance, seul Charvet continue d’assurer un service de chemises sur-mesure.

D’autres publicités des années 40 ont attiré notre oeil. Celles de Tricot Diogène, l’un des derniers atelier Français capable d’en produire des cravates en maille dont on a déjà parlé dans notre guide sur la cravate. Ou encore une publicité de Bianchini-Férier dont on peut encore trouver des cravates en occasion.

On a également vu une publicité d’Emo, un atelier situé à Troyes et spécialisé dans la maille qui est notamment connu pour avoir travaillé sur la première version du célèbre cardigan pression d’Agnès B.

Où trouver des anciens numéros du magazine ADAM ?

Le Palais Galliera a fait numériser 84 numéros sur une période allant de 1926 à 1948. C’est une vraie mine d’or qu’il est possible de consulter gratuitement. Vous pouvez y accéder ici.

Vous pouvez également trouver de rares exemplaires d’Adam sur le site Diktats. Quelques exemples :

Un hors-série consacré à la mode du Printemps 1943 intitulé Précisions sur les variations du vêtement masculin pour ce printemps 1943. Une publication intéressante sur la mode durant la seconde guerre mondiale.

Deux exemplaires de travail ayant appartenu au couturier Karl Lagerfeld. Le numéro 246 d'avril-mai 1958 et le numéro 233 de février-mars 1956.

Via eBay il est également courant de trouver des exemplaires. Ces derniers sont en général plus récents et donc également moins chers.

0 notes

Text

From the FASHION Archives: Karl, Before Chanel

Since its launch in 1977, FASHION magazine has been giving Canadian readers in-depth reports on the industry’s most influential figures and expert takes on the worlds of fashion, beauty and style. In this series, we explore the depths of our archive to bring you some of the best fashion features we’ve ever published. This story, originally titled “The Eccentric Luxe of Karl Lagerfeld” by Marci McDonald was originally published in FASHION’s Winter 1978 issue.

It was Karl Lagerfeld’s idea to throw the party at his house. “I thought it would be more personal,” he says. Six hundred of his most intimate friends were greeted at the doorway by liveried footmen in white wigs and blue-satin breeches brandishing gigantic silver candelabra. By the light of more than a thousand flickering tapers, they were led into his ivory-and-gilt 18th-century salons, large enough to hold a small gymkhana, only to confront buffer tables recreated to match Marie Antoinette’s finest. Three-tiered pièces montées, threatening to graze the ceiling frescoes, spilled over with foie-gras-trimmed dolphins and peacock-shaped saddles of lamb. The sweet table featured a 50-foot meringue fountain cascading petits fours and crowned by four life-sized jeweled sugar swans spouting green syrup water. Jean Seberg, his next door neighbour, came and declared it marvelous. Paloma Picasso, whose marriage to a penniless Argentinian playwright in Lagerfeld’s heart-shaped red-taffeta wedding dress had rivaled Princess Caroline’s as the social event of the season, remarked that it was “very Karl.” Only the host, looking a slightly dressier version of his usual cross between Count Dracula and Louis XVI, seemed to have any reservations, confiding later that he wished it all hadn’t been at the expense of promoting his new men’s perfume, instead of the simple little gathering of near and dear as he preferred to think of it. “Little do people know I lead such studious, down-to-earth life,” he sighs. “To be a celebrity – it’s very demanding. But I am my image, I’m afraid.”

The image perches on a folding plexiglass chair in the fading afternoon light that invades the two-floor Chloé empire just off Paris’ fashionable rue de la Boétie and peers out at the world through rose-colored glasses. He used to favor smoky lenses, but finds things vastly improved since the change. “Everybody looks 10 years younger,” he says. Not that everything Karl Lagerfeld lays eyes on now meets his approval. “Ugly, ugly, ugly,” he dismisses the better part of the universe – a condemnation second only to “borrowing.” Offices are boring, as are desks and “fixed points” – which leaves the Chloé staff swirling around him among racks of tweed and sequins in apparent casual mayhem. Most of the clothes in which the hoi poloi parade outside his windows are boring, and frequently ugly as well. Neither sin, however, can be attributed to his image, which on this particular day consists of the usual: black smock emblazoned with a six-inch monogram, one of the hundred handmade shirts he orders annually from Hilditch and Key, shirtmakers to the Shah of Iran, which requires him to have custom-built luggage in order to preserve their starched stand-up collars, and, at his throat, a flowing black-silk bow. His greying shoulder-length tresses are pulled back into a ribbon, his complexion so pale that in certain lights it appears freshly powdered.

It is not an image that the casual bystander might associate with the semi-annual outbursts of witty sophistication and romantic chic that have come to characterize Karl Lagerfeld’s contributions to those feverish April and October follies known as Paris’ prêt-à-porter collections. But on reflection, it is nothing if not appropriate. While not everyone might be prepared to go around done up as he does, it is also true that not everybody can wear a Chloé.

In the 10 years since he has emerged as one of France’s trend-setting fashion triumvirate along with close friends Kenzo Takada and Yves Saint Laurent, his name has become synonymous with a look of rarefied elegance and eccentric luxe that makes him closer to the grand style of haute couture than any other ready-to-wear designer. Wherever two or more of the relentlessly à la mode are gathered, there is bound to be a slither of cleverly constructed silk by Karl Lagerfeld. The press has hailed him as one of today’s most influential stylists but, in fact, the sphere of his influence is limited. While Saint Laurent has set the silhouette for two decades of dressing and Kenzo has cut the pattern for almost every trend that has filtered down to the streets, Karl Lagerfeld has fashioned a unique niche for himself – not copied by the masses, but not ignored either; a label more applauded than pirated; a name that has come to mean class by itself. Buyers tend to swoon over his showings, which have twice inspired the shrewd Martha Phillips of Martha, Palm Beach and New York, to exit rhapsodizing that they were “like a beautiful song.”

But the music to her ears may have been the cash register bearing witness to the fact that, beneath Lagerfeld’s outlandish exterior, there lurks the canny commercial intelligence that has managed to create not only what the ads unabashedly call “the world’s most beautiful clothes,” but also some of the most wearable. Bianca Jagger, the Baroness Olympia de Rothschild and Margaret Trudeau all number Chloés in their closets, as – much to Karl Lagerfeld’s astonishment – did did his ailing mother’s private nurse. “She kept turning up in all these dresses of mine,” he says, tinted shades only half-betraying the intimation that there are, after all, limits to the democratization of prêt-à-porter. Discreet inquiries, however, finally assured him that the Chloés hovering at the bedside came of impeccable lineage – castoffs from a former patient’s wife named Jacqueline Onassis.

The tiny ready-to-wear house that he signed on with 14 years ago now boasts 11 boutiques and 95 outlets in the world’s toniest fashion emporiums under his signature, chalking up $9 million in wholesale clothing sales last year alone – triple the business of three years ago. If the growth rate is just short of phenomenal, it is no accident. Today, ethnic and organic are stunningly out and the fashion tyrannies of the crunchy granola set are going down to the yawns. In a year when the blue jean has resurfaced in gloriously co-opted little $300 leather versions and glitz has become de rigueur, it may not be entirely coincidental that the designer of the hour is an exotic of rare plumage whose idea of getting back to basics was once to show tennis shoes with chiffon ball-gowns and T-shirts of crepe de Chine. “Today, fashion is not made in the streets as much as it was in the early ‘70s,” he says, the relief clearly evident in his voice. “Now there’s a new sophistication that has nothing to do with the streets – in fact, it may not even reach them.”

Certainly, the pavement was not what he seemed to have in mind when creating his fall collection. An androgynous stray from a Cabaret set, in black chesterfield coat and top hat, waltzed down the runway and opened prison gates to release his latest inspirations: hip-hugging petal-hem skirts blossoming over stiletto heels, lamé tunic dresses afloat over skin-tight black-satin pants and tiny bellboy hats perched on the forehead, all topped off by mammoth fake jewels that dripped from tweed lapels like relics from a chandelier disaster. They were droll, they were outrageous, and the fashion press promptly went into delirium, demanding to know their meaning. “Why, they don’t mean anything – they’re just fun,” said Karl Lagerfeld, only surprised that anyone would ask. Relevance, significance – he waves them off as only slightly more boring than inquiries into the origins of his image. “Who knows where it came from,” he shrugs. “It was just there.”

For those inclined to favor the environmental theory of character formation, it was not perhaps a childhood designed to produce the average citizen. Born in 1938 in the heart of Hitler’s Germany, Karl Lagerfeld cannot recall ever growing up aware that there was some international unpleasantness going on. Life continued as usual at the château in the countryside outside Hamburg, where he found himself the last child of the last marriages of two not entirely typical members of Third Reich gentry. His father, a canned-milk tycoon with an inclination for marrying, was 60 at his birth. His mother, who had worn a Paul Poiret gown for her first wedding and a Vionnet for her second, favored Lanvin for the war. Their offspring passed his time reading her back issues of La Gazette du Bon Ton, sketching her wardrobe and changing clothes three times daily. “Already, I hated open shirts,” he said. “I had collars up to here, bows and ties, even hats. I was a fashion freak. Even as a child, I was overdressed.”

He does remember a parade of rather curious people showing up at the château who later turned out to be war refugees, but the memory concerns him only insomuch as one of them tortured him in French – a language he could speak with devoted fluency from his sixth birthday. When he was 12, his mother took his drawings to the director of a Hamburg art school who refused him admittance, declaring, “This boy is not interested in art. He’s interested in costume.” At 14, he begged to be allowed to finish high school in France, pointing out that he had, after all, immigrated in spirit. His arrival by train at the Gare du Nord did not disappoint him – it was dirty, it was decadent, and it was gloriously Paris, the city where he has lived ever since. Boarding school, however, was another matter – crowded and cloying. “In those days, if you were the slightest bit out of the ordinary, you were considered and eccentric,” he says. “I wanted to be alone.”

He won permission to rent an apartment on his own to prepare for his bacclauréat exams, provided that his father’s minions could keep an eye on him. When the other eye was closed, he secretly entered the International Wool Competition fashion contest for amateurs. He was just past his 16th birthday when his sketch of a little wool coat captured first prize and he was catapulted into a career that over the next 23 years was in many ways to mirror the progress of fashion itself.

The year was 1955 – mid-point in the heavy heyday of haute couture’s resuscitation by a one-time designer’s assistant named Christian Dior, who had opened his salons during the liberation sweep-up in 1947 with what he called the New Look, and was promptly hailed as the man who had saved Paris. Each July and January the world hung on his prophecies for hem lengths and hair lengths, while names like Jacques Fath, Pierre Balmain, Cristobel Balenciaga and Hubert de Givenchy were lesser stars who revolved around his headlines’ pivotal glare. In 1955, the press was in its usual uproar over Dior’s newest look, the A-line, and did not pay particular attention to the International Wool Competition fashion contest which two teenagers had just won: Karl Lagerfeld in the coat category and, in the dress category, a gangling blond 19-year-old who was to become one of Lagerfeld’s closest friends and two years later, Dior’s heir – Yves Saint Laurent.

While Dior plucked Saint Laurent out of the contest to become his dauphin, Balmain, one of the judges, sometimes known as the “couturier of queens,” offered Lagerfeld a stylist’s job. He worked with Balmain for three months before he had the courage to break the news to his parents, and stayed three years. He failed to meet any queens, but did help dress Anita Ekberg, Vivien Leigh, Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida and even Bardot, although in retrospect he cherishes no fond memories. “Pierre Balmain was very teacherlike,” he says. “But the whole atmosphere with models and all was very borellolike. I just thought it was not chic at all.” Bored, he toyed with the thought of going back to school, when a job offer as art director at the venerable couture house of Jean Patou saved him – but in the end, only for more boredom. “Twice a year, I turned out 50 dresses,” he says. “It wasn’t enough for me. I spent the rest of my life at nightclubs, on beaches, at parties. It was empty, completely empty. When I think about it today, it was really the most boring and stupid time of my life.” After five years, he dropped out of couture altogether, the bloom rubbed thin on the boyhood dream. “I didn’t like the atmosphere. You waited there for your private clients, then you flattered them so they’d keep coming back. But they were just boring. Uglies – all uglies. Today there are 50 girls in the street who look better than the women who wear haute couture. I didn’t like what Balenciaga was doing. I didn’t like what Chanel was doing – all those little suits – maybe because I saw so many ugly copies on so many ugly women.”

At 25, he decided to devote himself to a life of the mind, but found that finishing his high school diploma did not always provide sufficient inspiration to get up in the morning, nor even in the afternoon. A year of more parties. And more boredom. “Then suddenly I realized work was the most important thing in my life, more important than all the rest of that stuff. I knew couture was finished. But something was changing.”

It was 1964, two years before Saint Laurent descended from his haute-couture shrine on the right bank to set up a Left bank boutique for the vast unwashed, making mass retailing respectable. The Paris ready-to-wear industry was still a slightly disreputable collection of pirates devoted to churning out bargain-rate couturier rip-offs, thanks to the advances in mass production and manmade fabrics with such odd names as Orlon, rayon and Terylene. The idea of men’s fashion had become fashionable, and teenagers with fat disposable dispentions from daddy had created a new market that British upstarts like Mary Quant were blithely capitalizing on with the miniskirt.

But in Paris the only rustlings of a change in the wind were cries of indignation going up from the couturier salons. “Paris has lost its leadership,” fussed Pierre Cardin, while Courrèges fumed that, “I, for one, won’t stand for it,” though what he intended to do nobody had the slightest idea. Among the mass-market outlets, however, there was one tiny house called Chloé, owned by a former financier named Jacques Lenoir, which had delusions of grander things under a young designer named Gérard Pipart. When Pipart was hired away by the couture house of Nina Ricci, Lenoir regarding it as such a disaster that he replaced him with four newcomers – names like Graziella Fontana, Tan Guidicelli, Christine Baille and Karl Lagerfeld – and decided to let them fight it out.

“It was very inspirational,” Lenoir says. “They were like phagocytes in the blood, where the one eats the other. Karl learned a lot from the others, but when it came to competition, he always came out on top. He was stronger, he had more force of personality.”

Indeed, the strength is almost physically tangible when you meet Lagerfeld in person, the image only half concealing a surprisingly solid man with large fleshy hands who looks as if, should the need arise, he could arm-wrestle the ugly or boring to the ground. The sensuous mouth has a capacity for the brutal as it echoes its staccato bulletins in four languages, mingling high camp, high bitchery and exquisite manners with penetrating analyses of the most pragmatic sort. He is briskly efficient, sardonically high-charged – transformed from the languorous wunderkind who once could barely struggle into Patou by 3 p.m. and devoted whole evenings to pondering the meaning of life. But then, he had finally found it, at least for himself. The discovery released so much energy that he designed not only for Chloé, but whipped off freelance work for Charles Jourdan shoes and Fendi furs, along with a band of such other young free spirits as Kenzo and Sonia Rykiel, who were invading the transformed landscape of ready-to-wear.

“I did everything,” he says. “It was very tiring, but very amusing, too – getting up early to take trains to go to the factories, taking planes here and there. It was the best way to learn, because I had never gone to fashion school. And nobody had done it before. We were a little community of pioneers.”

Within 10 years, the little community of pioneers had left haute couture languishing in charming oblivion. Their rambunctious April and October showing stole the thunder – and the crowds – from the ancient rituals in mirrored salons where the faithful perched on little gold chairs. Prêt-à-porter began to hand down the prophecies for the world’s closets, and just as promptly to fill them up, inspiring its own cut-rate copiers, while its brash young stars eclipsed the old names in an entirely new firmament of fashion. No longer did a woman dress under one label. The new rule was that there were no rules and there were as many styles as there were brash young upstarts with chutzpah and scissors.

By 1974, the process of Darwinian selection had left only Karl Lagerfeld at Chloé, where he was offered an exclusive contract and, in tribute to his stardom, his own perfume. He chose a sweet, heavy, old-worldly scent in keeping with his image. “At the time, everything was light, green, duty-free as I call it,” he sniffs. “It set a new trend.” Elizabeth Arden, who holds the franchise, now sells $11 million worth of liquid Chloé a year. Having just launched a men’s cologne, Lagerfeld is already at work on a second feminine fragrance scheduled for 1980 unbottling – “something quite eccentric, I think.” Discussions are also underway for makeup and a men’s line, although he refuses to design for children and linen closets. “One day your name cannot be used any more – only for toilet paper.”

His place in posterity assured, he now looks down from the heights of chic to observe his former conferes of haute couture – like Marc Bohan of Dior – with charity. “Boring – they’re only allowed to do boring things. Of course, they’re only employees. Sleeping beauties, I call them.” He does not resent the phenomenal success of Saint Laurent who has outstripped him even in the prêt-à-porter arena, and they continue to be the closest of friends. “Yves was always more ambitious than I was. He likes high fashion. He never found it humiliating. And he made lots of efforts that I’d never have made.” For example? “Well, for example, I’d never have consented to live with Pierre Bergé (Saint Laurent’s business partner and companion) for 20 years. I mean, there are prices I wouldn’t pay.”

A tiny bronze buzzer swings open the massive iron door on rue de l’Université and a security guard points the way across a courtyard roughly the size of a skating rink. A greying housekeeper in a worn sweater leads the way up marble stairs to the lofty salons where Karl Lagerfeld has consented to be photographed in a little at-home portrait. He sweeps in 20 minutes late, brisk and understated, a shrunken monogram on his dun-colored smock, only a thin western string tie which was the gift of the people at Neiman Marcus in place of the usual flounce – a sobered image due perhaps to the fact that he had just celebrated his 40th birthday two days earlier at his 18th-century château in Brittany where his mother now presides.

“I always live in 18th-century houses,” he says. “For me, it’s the perfection of human culture – the top.” In fact, he once did not live in an 18th-century house when he was making his name as a freelancer, but in a Left Bank apartment surrounded by one of the most lavish Art Deco collections then in existence. He had a backdrop made for it, and immediately had to auction the whole thing off. “It was too much – too fragile, too beautiful. I couldn’t live in it. It was like waking up every morning in an opera set.” Besides, so many people were getting into Art Deco. Now he collects state beds – Madame du Barry’s, the Duke of Richelieu’s, the Princess of Conti’s. Most are in the country château, but there is one of the indeterminate ownership plumped here in the midst of a receiving room, its white-silk coverlet and headboard sumptuously embroidered with a motif of the four seasons. It turns out to be one of the few pieces of furniture in the entire place. He keeps the rooms empty on purpose. “I don’t want to look nouveau riche,” he says.

It is virtually the eve of his next collection, and there is not much time for the setting. A gentle-faced young man serves apple juice on a silver tray and Karl Lagerfeld keeps examining his watch. His fabrics are late in arriving from the factories, his fittings are delayed and he has not yet seen the drift of his next seasonal direction, which makes him tense, although never given to the bouts of hysteria Saint Laurent is said to glory in. “What’s the point?” he says. “A dress doesn’t last forever. In the business, you start all over again every six months.” Still, he shuns holidays and works so obsessively that colleagues confide that Karl Lagerfeld’s problem is not that he may one day dry up on ideas, but that he has to be stopped. His study, a crammed anteroom to one of the salons, erupts with costume histories and ancient fashion circulars that spill over from his drawing board and onto the floor, but he shies from specific discussions of the Muse. “Designers shouldn’t talk too much; they should design. I believe only in instinct, intuition. I believe in imagining things from a window.”

He does not like all of this boring talk of the nuts and bolts, the whys and wherefores. He prefers to deal in images. The night he threw a little candlelight dinner for 40 here in honor of Paloma Picasso’s wedding – “the whole table filled with flowers, orchids the same red as her dress. I must say it was magic.” The little costume ball that Saint Laurent’s associate LouLou de la Falaise held at a disco palace where he turned up in a crystal-beaded jumpsuit and feathers once worn by Josephine Baker. The evenings he insists he spends dining in these rooms alone, according to the counsel of his fortune teller, scarlet drapes drawn, the table splendidly laid for one, while scented candles cast a spell upon the air. He quick-sketches the scenes as one might imagine looking in upon a life through a window. With a stylist’s finely honed eye, he settles upon each detail he chooses to reveal.

It is, after all, no easy task to tread the uneasy line between mass design and mystique, between turning out dresses that everywoman can buy off the rack while leaving the impression that only the truly privileged could attain such a luxury. Karl Lagerfeld, who prefers to work his magic in crepe de Chine rather than cheesecloth, who introduced satin knickers and tried to bring back the fan, has a showman’s unwavering sense of his audience. Strangers are not invited to his workrooms. Colleagues are discouraged from answering questions about him. Upstairs and downstairs in this townhouse, which he writes off for promotion purposes on his taxes, there are other rooms – private apartments that are never seen, never photographed.

The camera clicks. The image is preserved in the splendor of an empty salon. Karl Lagerfeld is in a hurry for his next appointment and rushes off with the gentle-eyed young photographer, shaking hands all around. It is a demanding, tightly scheduled life where even the star of the hour cannot be sure he will not be upstaged a half-year away. It is sometimes not a glamorous life at all, although one only has his word for it.

“I don’t believe in glamour,” he says. “Glamour is very artificial.”

Our footsteps echo on the marble staircase as the housekeeper lets us out with two plastic garbage bags in her hand, which she deposits behind a closed 18th-century door.

The post From the FASHION Archives: Karl, Before Chanel appeared first on FASHION Magazine.

From the FASHION Archives: Karl, Before Chanel published first on https://borboletabags.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

From the FASHION Archives: Karl, Before Chanel

Since its launch in 1977, FASHION magazine has been giving Canadian readers in-depth reports on the industry’s most influential figures and expert takes on the worlds of fashion, beauty and style. In this series, we explore the depths of our archive to bring you some of the best fashion features we’ve ever published. This story, originally titled “The Eccentric Luxe of Karl Lagerfeld” by Marci McDonald was originally published in FASHION’s Winter 1978 issue.

It was Karl Lagerfeld’s idea to throw the party at his house. “I thought it would be more personal,” he says. Six hundred of his most intimate friends were greeted at the doorway by liveried footmen in white wigs and blue-satin breeches brandishing gigantic silver candelabra. By the light of more than a thousand flickering tapers, they were led into his ivory-and-gilt 18th-century salons, large enough to hold a small gymkhana, only to confront buffer tables recreated to match Marie Antoinette’s finest. Three-tiered pièces montées, threatening to graze the ceiling frescoes, spilled over with foie-gras-trimmed dolphins and peacock-shaped saddles of lamb. The sweet table featured a 50-foot meringue fountain cascading petits fours and crowned by four life-sized jeweled sugar swans spouting green syrup water. Jean Seberg, his next door neighbour, came and declared it marvelous. Paloma Picasso, whose marriage to a penniless Argentinian playwright in Lagerfeld’s heart-shaped red-taffeta wedding dress had rivaled Princess Caroline’s as the social event of the season, remarked that it was “very Karl.” Only the host, looking a slightly dressier version of his usual cross between Count Dracula and Louis XVI, seemed to have any reservations, confiding later that he wished it all hadn’t been at the expense of promoting his new men’s perfume, instead of the simple little gathering of near and dear as he preferred to think of it. “Little do people know I lead such studious, down-to-earth life,” he sighs. “To be a celebrity – it’s very demanding. But I am my image, I’m afraid.”

The image perches on a folding plexiglass chair in the fading afternoon light that invades the two-floor Chloé empire just off Paris’ fashionable rue de la Boétie and peers out at the world through rose-colored glasses. He used to favor smoky lenses, but finds things vastly improved since the change. “Everybody looks 10 years younger,” he says. Not that everything Karl Lagerfeld lays eyes on now meets his approval. “Ugly, ugly, ugly,” he dismisses the better part of the universe – a condemnation second only to “borrowing.” Offices are boring, as are desks and “fixed points” – which leaves the Chloé staff swirling around him among racks of tweed and sequins in apparent casual mayhem. Most of the clothes in which the hoi poloi parade outside his windows are boring, and frequently ugly as well. Neither sin, however, can be attributed to his image, which on this particular day consists of the usual: black smock emblazoned with a six-inch monogram, one of the hundred handmade shirts he orders annually from Hilditch and Key, shirtmakers to the Shah of Iran, which requires him to have custom-built luggage in order to preserve their starched stand-up collars, and, at his throat, a flowing black-silk bow. His greying shoulder-length tresses are pulled back into a ribbon, his complexion so pale that in certain lights it appears freshly powdered.

It is not an image that the casual bystander might associate with the semi-annual outbursts of witty sophistication and romantic chic that have come to characterize Karl Lagerfeld’s contributions to those feverish April and October follies known as Paris’ prêt-à-porter collections. But on reflection, it is nothing if not appropriate. While not everyone might be prepared to go around done up as he does, it is also true that not everybody can wear a Chloé.

In the 10 years since he has emerged as one of France’s trend-setting fashion triumvirate along with close friends Kenzo Takada and Yves Saint Laurent, his name has become synonymous with a look of rarefied elegance and eccentric luxe that makes him closer to the grand style of haute couture than any other ready-to-wear designer. Wherever two or more of the relentlessly à la mode are gathered, there is bound to be a slither of cleverly constructed silk by Karl Lagerfeld. The press has hailed him as one of today’s most influential stylists but, in fact, the sphere of his influence is limited. While Saint Laurent has set the silhouette for two decades of dressing and Kenzo has cut the pattern for almost every trend that has filtered down to the streets, Karl Lagerfeld has fashioned a unique niche for himself – not copied by the masses, but not ignored either; a label more applauded than pirated; a name that has come to mean class by itself. Buyers tend to swoon over his showings, which have twice inspired the shrewd Martha Phillips of Martha, Palm Beach and New York, to exit rhapsodizing that they were “like a beautiful song.”

But the music to her ears may have been the cash register bearing witness to the fact that, beneath Lagerfeld’s outlandish exterior, there lurks the canny commercial intelligence that has managed to create not only what the ads unabashedly call “the world’s most beautiful clothes,” but also some of the most wearable. Bianca Jagger, the Baroness Olympia de Rothschild and Margaret Trudeau all number Chloés in their closets, as – much to Karl Lagerfeld’s astonishment – did did his ailing mother’s private nurse. “She kept turning up in all these dresses of mine,” he says, tinted shades only half-betraying the intimation that there are, after all, limits to the democratization of prêt-à-porter. Discreet inquiries, however, finally assured him that the Chloés hovering at the bedside came of impeccable lineage – castoffs from a former patient’s wife named Jacqueline Onassis.

The tiny ready-to-wear house that he signed on with 14 years ago now boasts 11 boutiques and 95 outlets in the world’s toniest fashion emporiums under his signature, chalking up $9 million in wholesale clothing sales last year alone – triple the business of three years ago. If the growth rate is just short of phenomenal, it is no accident. Today, ethnic and organic are stunningly out and the fashion tyrannies of the crunchy granola set are going down to the yawns. In a year when the blue jean has resurfaced in gloriously co-opted little $300 leather versions and glitz has become de rigueur, it may not be entirely coincidental that the designer of the hour is an exotic of rare plumage whose idea of getting back to basics was once to show tennis shoes with chiffon ball-gowns and T-shirts of crepe de Chine. “Today, fashion is not made in the streets as much as it was in the early ‘70s,” he says, the relief clearly evident in his voice. “Now there’s a new sophistication that has nothing to do with the streets – in fact, it may not even reach them.”

Certainly, the pavement was not what he seemed to have in mind when creating his fall collection. An androgynous stray from a Cabaret set, in black chesterfield coat and top hat, waltzed down the runway and opened prison gates to release his latest inspirations: hip-hugging petal-hem skirts blossoming over stiletto heels, lamé tunic dresses afloat over skin-tight black-satin pants and tiny bellboy hats perched on the forehead, all topped off by mammoth fake jewels that dripped from tweed lapels like relics from a chandelier disaster. They were droll, they were outrageous, and the fashion press promptly went into delirium, demanding to know their meaning. “Why, they don’t mean anything – they’re just fun,” said Karl Lagerfeld, only surprised that anyone would ask. Relevance, significance – he waves them off as only slightly more boring than inquiries into the origins of his image. “Who knows where it came from,” he shrugs. “It was just there.”

For those inclined to favor the environmental theory of character formation, it was not perhaps a childhood designed to produce the average citizen. Born in 1938 in the heart of Hitler’s Germany, Karl Lagerfeld cannot recall ever growing up aware that there was some international unpleasantness going on. Life continued as usual at the château in the countryside outside Hamburg, where he found himself the last child of the last marriages of two not entirely typical members of Third Reich gentry. His father, a canned-milk tycoon with an inclination for marrying, was 60 at his birth. His mother, who had worn a Paul Poiret gown for her first wedding and a Vionnet for her second, favored Lanvin for the war. Their offspring passed his time reading her back issues of La Gazette du Bon Ton, sketching her wardrobe and changing clothes three times daily. “Already, I hated open shirts,” he said. “I had collars up to here, bows and ties, even hats. I was a fashion freak. Even as a child, I was overdressed.”

He does remember a parade of rather curious people showing up at the château who later turned out to be war refugees, but the memory concerns him only insomuch as one of them tortured him in French – a language he could speak with devoted fluency from his sixth birthday. When he was 12, his mother took his drawings to the director of a Hamburg art school who refused him admittance, declaring, “This boy is not interested in art. He’s interested in costume.” At 14, he begged to be allowed to finish high school in France, pointing out that he had, after all, immigrated in spirit. His arrival by train at the Gare du Nord did not disappoint him – it was dirty, it was decadent, and it was gloriously Paris, the city where he has lived ever since. Boarding school, however, was another matter – crowded and cloying. “In those days, if you were the slightest bit out of the ordinary, you were considered and eccentric,” he says. “I wanted to be alone.”

He won permission to rent an apartment on his own to prepare for his bacclauréat exams, provided that his father’s minions could keep an eye on him. When the other eye was closed, he secretly entered the International Wool Competition fashion contest for amateurs. He was just past his 16th birthday when his sketch of a little wool coat captured first prize and he was catapulted into a career that over the next 23 years was in many ways to mirror the progress of fashion itself.

The year was 1955 – mid-point in the heavy heyday of haute couture’s resuscitation by a one-time designer’s assistant named Christian Dior, who had opened his salons during the liberation sweep-up in 1947 with what he called the New Look, and was promptly hailed as the man who had saved Paris. Each July and January the world hung on his prophecies for hem lengths and hair lengths, while names like Jacques Fath, Pierre Balmain, Cristobel Balenciaga and Hubert de Givenchy were lesser stars who revolved around his headlines’ pivotal glare. In 1955, the press was in its usual uproar over Dior’s newest look, the A-line, and did not pay particular attention to the International Wool Competition fashion contest which two teenagers had just won: Karl Lagerfeld in the coat category and, in the dress category, a gangling blond 19-year-old who was to become one of Lagerfeld’s closest friends and two years later, Dior’s heir – Yves Saint Laurent.

While Dior plucked Saint Laurent out of the contest to become his dauphin, Balmain, one of the judges, sometimes known as the “couturier of queens,” offered Lagerfeld a stylist’s job. He worked with Balmain for three months before he had the courage to break the news to his parents, and stayed three years. He failed to meet any queens, but did help dress Anita Ekberg, Vivien Leigh, Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida and even Bardot, although in retrospect he cherishes no fond memories. “Pierre Balmain was very teacherlike,” he says. “But the whole atmosphere with models and all was very borellolike. I just thought it was not chic at all.” Bored, he toyed with the thought of going back to school, when a job offer as art director at the venerable couture house of Jean Patou saved him – but in the end, only for more boredom. “Twice a year, I turned out 50 dresses,” he says. “It wasn’t enough for me. I spent the rest of my life at nightclubs, on beaches, at parties. It was empty, completely empty. When I think about it today, it was really the most boring and stupid time of my life.” After five years, he dropped out of couture altogether, the bloom rubbed thin on the boyhood dream. “I didn’t like the atmosphere. You waited there for your private clients, then you flattered them so they’d keep coming back. But they were just boring. Uglies – all uglies. Today there are 50 girls in the street who look better than the women who wear haute couture. I didn’t like what Balenciaga was doing. I didn’t like what Chanel was doing – all those little suits – maybe because I saw so many ugly copies on so many ugly women.”

At 25, he decided to devote himself to a life of the mind, but found that finishing his high school diploma did not always provide sufficient inspiration to get up in the morning, nor even in the afternoon. A year of more parties. And more boredom. “Then suddenly I realized work was the most important thing in my life, more important than all the rest of that stuff. I knew couture was finished. But something was changing.”

It was 1964, two years before Saint Laurent descended from his haute-couture shrine on the right bank to set up a Left bank boutique for the vast unwashed, making mass retailing respectable. The Paris ready-to-wear industry was still a slightly disreputable collection of pirates devoted to churning out bargain-rate couturier rip-offs, thanks to the advances in mass production and manmade fabrics with such odd names as Orlon, rayon and Terylene. The idea of men’s fashion had become fashionable, and teenagers with fat disposable dispentions from daddy had created a new market that British upstarts like Mary Quant were blithely capitalizing on with the miniskirt.

But in Paris the only rustlings of a change in the wind were cries of indignation going up from the couturier salons. “Paris has lost its leadership,” fussed Pierre Cardin, while Courrèges fumed that, “I, for one, won’t stand for it,” though what he intended to do nobody had the slightest idea. Among the mass-market outlets, however, there was one tiny house called Chloé, owned by a former financier named Jacques Lenoir, which had delusions of grander things under a young designer named Gérard Pipart. When Pipart was hired away by the couture house of Nina Ricci, Lenoir regarding it as such a disaster that he replaced him with four newcomers – names like Graziella Fontana, Tan Guidicelli, Christine Baille and Karl Lagerfeld – and decided to let them fight it out.

“It was very inspirational,” Lenoir says. “They were like phagocytes in the blood, where the one eats the other. Karl learned a lot from the others, but when it came to competition, he always came out on top. He was stronger, he had more force of personality.”

Indeed, the strength is almost physically tangible when you meet Lagerfeld in person, the image only half concealing a surprisingly solid man with large fleshy hands who looks as if, should the need arise, he could arm-wrestle the ugly or boring to the ground. The sensuous mouth has a capacity for the brutal as it echoes its staccato bulletins in four languages, mingling high camp, high bitchery and exquisite manners with penetrating analyses of the most pragmatic sort. He is briskly efficient, sardonically high-charged – transformed from the languorous wunderkind who once could barely struggle into Patou by 3 p.m. and devoted whole evenings to pondering the meaning of life. But then, he had finally found it, at least for himself. The discovery released so much energy that he designed not only for Chloé, but whipped off freelance work for Charles Jourdan shoes and Fendi furs, along with a band of such other young free spirits as Kenzo and Sonia Rykiel, who were invading the transformed landscape of ready-to-wear.

“I did everything,” he says. “It was very tiring, but very amusing, too – getting up early to take trains to go to the factories, taking planes here and there. It was the best way to learn, because I had never gone to fashion school. And nobody had done it before. We were a little community of pioneers.”

Within 10 years, the little community of pioneers had left haute couture languishing in charming oblivion. Their rambunctious April and October showing stole the thunder – and the crowds – from the ancient rituals in mirrored salons where the faithful perched on little gold chairs. Prêt-à-porter began to hand down the prophecies for the world’s closets, and just as promptly to fill them up, inspiring its own cut-rate copiers, while its brash young stars eclipsed the old names in an entirely new firmament of fashion. No longer did a woman dress under one label. The new rule was that there were no rules and there were as many styles as there were brash young upstarts with chutzpah and scissors.

By 1974, the process of Darwinian selection had left only Karl Lagerfeld at Chloé, where he was offered an exclusive contract and, in tribute to his stardom, his own perfume. He chose a sweet, heavy, old-worldly scent in keeping with his image. “At the time, everything was light, green, duty-free as I call it,” he sniffs. “It set a new trend.” Elizabeth Arden, who holds the franchise, now sells $11 million worth of liquid Chloé a year. Having just launched a men’s cologne, Lagerfeld is already at work on a second feminine fragrance scheduled for 1980 unbottling – “something quite eccentric, I think.” Discussions are also underway for makeup and a men’s line, although he refuses to design for children and linen closets. “One day your name cannot be used any more – only for toilet paper.”

His place in posterity assured, he now looks down from the heights of chic to observe his former conferes of haute couture – like Marc Bohan of Dior – with charity. “Boring – they’re only allowed to do boring things. Of course, they’re only employees. Sleeping beauties, I call them.” He does not resent the phenomenal success of Saint Laurent who has outstripped him even in the prêt-à-porter arena, and they continue to be the closest of friends. “Yves was always more ambitious than I was. He likes high fashion. He never found it humiliating. And he made lots of efforts that I’d never have made.” For example? “Well, for example, I’d never have consented to live with Pierre Bergé (Saint Laurent’s business partner and companion) for 20 years. I mean, there are prices I wouldn’t pay.”

A tiny bronze buzzer swings open the massive iron door on rue de l’Université and a security guard points the way across a courtyard roughly the size of a skating rink. A greying housekeeper in a worn sweater leads the way up marble stairs to the lofty salons where Karl Lagerfeld has consented to be photographed in a little at-home portrait. He sweeps in 20 minutes late, brisk and understated, a shrunken monogram on his dun-colored smock, only a thin western string tie which was the gift of the people at Neiman Marcus in place of the usual flounce – a sobered image due perhaps to the fact that he had just celebrated his 40th birthday two days earlier at his 18th-century château in Brittany where his mother now presides.

“I always live in 18th-century houses,” he says. “For me, it’s the perfection of human culture – the top.” In fact, he once did not live in an 18th-century house when he was making his name as a freelancer, but in a Left Bank apartment surrounded by one of the most lavish Art Deco collections then in existence. He had a backdrop made for it, and immediately had to auction the whole thing off. “It was too much – too fragile, too beautiful. I couldn’t live in it. It was like waking up every morning in an opera set.” Besides, so many people were getting into Art Deco. Now he collects state beds – Madame du Barry’s, the Duke of Richelieu’s, the Princess of Conti’s. Most are in the country château, but there is one of the indeterminate ownership plumped here in the midst of a receiving room, its white-silk coverlet and headboard sumptuously embroidered with a motif of the four seasons. It turns out to be one of the few pieces of furniture in the entire place. He keeps the rooms empty on purpose. “I don’t want to look nouveau riche,” he says.

It is virtually the eve of his next collection, and there is not much time for the setting. A gentle-faced young man serves apple juice on a silver tray and Karl Lagerfeld keeps examining his watch. His fabrics are late in arriving from the factories, his fittings are delayed and he has not yet seen the drift of his next seasonal direction, which makes him tense, although never given to the bouts of hysteria Saint Laurent is said to glory in. “What’s the point?” he says. “A dress doesn’t last forever. In the business, you start all over again every six months.” Still, he shuns holidays and works so obsessively that colleagues confide that Karl Lagerfeld’s problem is not that he may one day dry up on ideas, but that he has to be stopped. His study, a crammed anteroom to one of the salons, erupts with costume histories and ancient fashion circulars that spill over from his drawing board and onto the floor, but he shies from specific discussions of the Muse. “Designers shouldn’t talk too much; they should design. I believe only in instinct, intuition. I believe in imagining things from a window.”

He does not like all of this boring talk of the nuts and bolts, the whys and wherefores. He prefers to deal in images. The night he threw a little candlelight dinner for 40 here in honor of Paloma Picasso’s wedding – “the whole table filled with flowers, orchids the same red as her dress. I must say it was magic.” The little costume ball that Saint Laurent’s associate LouLou de la Falaise held at a disco palace where he turned up in a crystal-beaded jumpsuit and feathers once worn by Josephine Baker. The evenings he insists he spends dining in these rooms alone, according to the counsel of his fortune teller, scarlet drapes drawn, the table splendidly laid for one, while scented candles cast a spell upon the air. He quick-sketches the scenes as one might imagine looking in upon a life through a window. With a stylist’s finely honed eye, he settles upon each detail he chooses to reveal.

It is, after all, no easy task to tread the uneasy line between mass design and mystique, between turning out dresses that everywoman can buy off the rack while leaving the impression that only the truly privileged could attain such a luxury. Karl Lagerfeld, who prefers to work his magic in crepe de Chine rather than cheesecloth, who introduced satin knickers and tried to bring back the fan, has a showman’s unwavering sense of his audience. Strangers are not invited to his workrooms. Colleagues are discouraged from answering questions about him. Upstairs and downstairs in this townhouse, which he writes off for promotion purposes on his taxes, there are other rooms – private apartments that are never seen, never photographed.

The camera clicks. The image is preserved in the splendor of an empty salon. Karl Lagerfeld is in a hurry for his next appointment and rushes off with the gentle-eyed young photographer, shaking hands all around. It is a demanding, tightly scheduled life where even the star of the hour cannot be sure he will not be upstaged a half-year away. It is sometimes not a glamorous life at all, although one only has his word for it.

“I don’t believe in glamour,” he says. “Glamour is very artificial.”

Our footsteps echo on the marble staircase as the housekeeper lets us out with two plastic garbage bags in her hand, which she deposits behind a closed 18th-century door.

0 notes

Link

Karl Lagerfeld has died at the age of 85.

Chanel's creative director died in hospital in Paris on Tuesday morning.

Besides his creative vision, Lagerfeld will be remembered for iconic outfit of a tailored black jacket, black shades, and a highly-starched, high-collared white shirt.

The London tailor responsible for creating Lagerfeld's trademark shirts, Hilditch & Key, told INSIDER that the designer had more than 1,000 of them made.

Hilditch & Key also sent INSIDER a number of sketches drawn by Lagerfeld himself for the tailors to work from.

Iconic fashion desginer Karl Lagerfeld has died at the age of 85.

The cause of death for Chanel's creative director is not yet known, but reports suggest Lagerfeld had been "weak for many weeks."

A statement from The House of Karl Lagerfeld sent to INSIDER confirmed he died on Tuesday morning in Paris.

He died in hospital after being urgently admitted on Monday night, according to French news site Pure People.

Besides his creative vision, Lagerfeld will be remembered for his zingy — often controversial — one-liners and, of course, his iconic high-collared white shirts, each with enough starch to stand of their own accord.

Lagerfeld's shirts, teamed with a black tailored jacket, wide black tie with tie pin, fingerless gloves, and shock-white hair formed an iconic look that was as instantly recognisable as a superhero's costume.

Read more: Karl Lagerfeld said his cat Choupette was one of the heirs to his $200 million fortune

According to a profile written by The Independent in 2011, Lagerfeld had around 1,000 of the white shirts, which he bought from Jermyn Street tailors Hilditch & Key in London.

"Mr Lagerfeld had a long-standing relationship with Hilditch & Key," the tailor's CEO Steven Miller wrote in an email to INSIDER.

"He will be sadly missed in the fashion world."

Miller added that 1,000 shirts "was a very conservative estimation," and that Lagerfeld would actually send in hand-drawn designs for his shirts.

He included some of the sketches of the shirts, which offer a fascinating insight into the way Lagerfeld worked.

"He was first introduced to the brand by his uncle at the age of 16," Miller said.

In this sketch, Lagerfeld even includes his own iconic shades and ponytail.

Miller added that the tailors "will miss him greatly."

SEE ALSO: In an interview a year before his death, Karl Lagerfeld said he'd had 'every test under the sun and they can't find anything wrong'

Join the conversation about this story »

NOW WATCH: We tried a pen that erases makeup mistakes.

from Design http://bit.ly/2GPSnsZ

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

instagram

#swansongsrjdm#steez#elegant#menswear#haberdasher#paris style#made in france#Hilditch & Key#Hilditch & Key Paris#Bianchini-Férier#Instagram

0 notes

Text

instagram

#swansongsrjdm#menswear#elegant#steez#haberdasher#paris style#made in france#Hilditch & Key#Hilditch & Key Paris#Hilditch et key#Instagram

0 notes

Text

Karl Lagerfeld’s paisley silk dressing gowns from Hilditch & Key Paris, not London. He had them create various creative “KL” monograms for his robes and custom shirts. For more, my book - by far the most informative discussion of Hilditch & Key, Sulka, Charvet and many others - is available at the link in my bio.

#swansongsrjdm#steez#elegant#menswear#sulka#beautiful#haberdasher#paris style#made in france#arnys#bespoke#french style#Hilditch & Key#hilditch et key#Hilditch & Key Paris

0 notes

Text

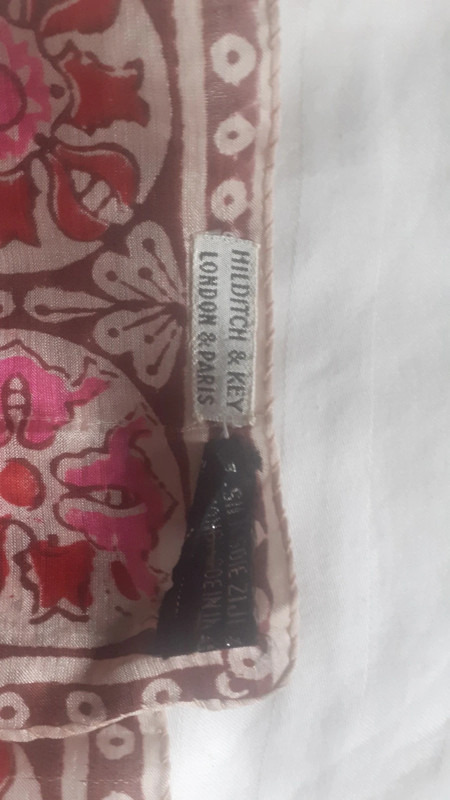

Hilditch & Key Paris handwoven silk scarf

These were big in the 1980s.

#swansongsrjdm#Hilditch et Key#Hilditch & Key#Hilditch & Key Paris#hildeetch#Hilditch and Key#H&K#H&K Paris#made in India#steez#menswear#elegant

0 notes

Photo

Hunting leopards medieval tapestry print silk handkerchief from @stephen_linard95 , from what he calls the lost golden age of #Drakes, when there was shared inspiration with Hilditch & Key Paris, whose cashmere-silk print scarf this lies on. For more, my book Swan Songs: Souvenirs of Paris Elegance is available through the link in my bio or at Chato Lufsen in Paris. #swansongsrjdm #hilditchetkey #hilditchandkeyparis #elegant #menswear #steez #parisfashion #parisfashionbook #menswearbook https://www.instagram.com/p/Cq78ZUlLl8U/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#drakes#swansongsrjdm#hilditchetkey#hilditchandkeyparis#elegant#menswear#steez#parisfashion#parisfashionbook#menswearbook

3 notes

·

View notes