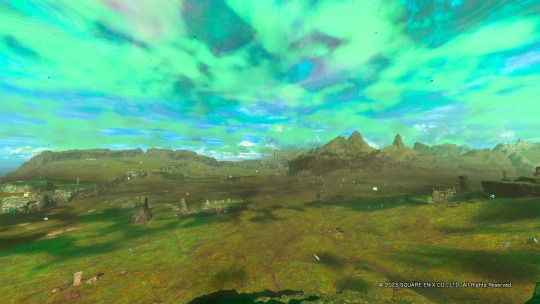

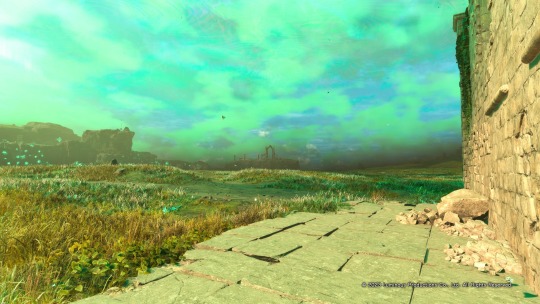

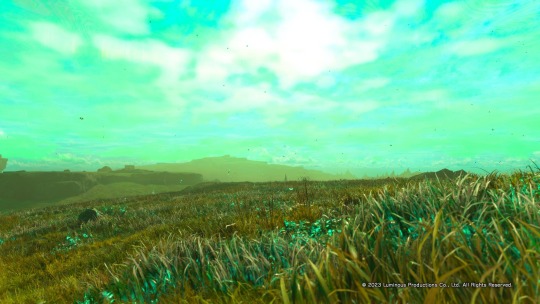

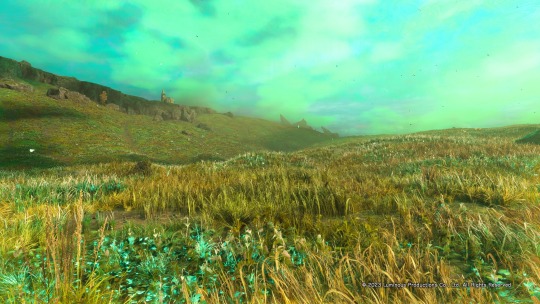

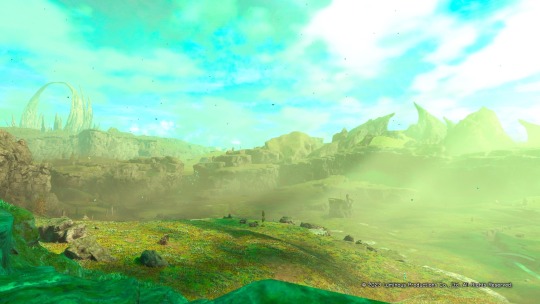

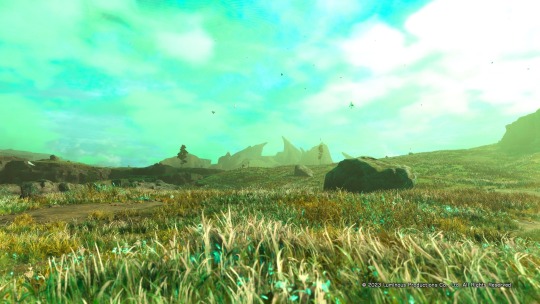

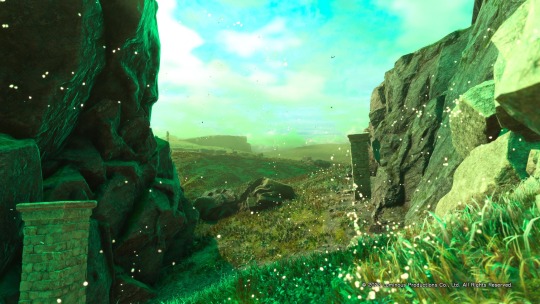

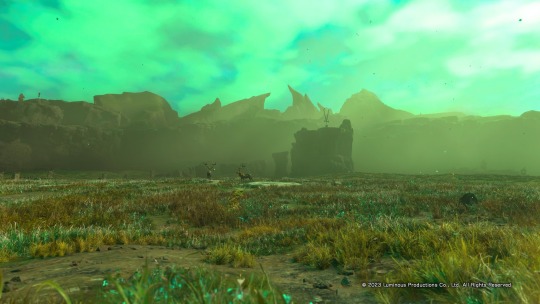

#Humble Plain: Western Refuge

Text

Forspoken Photo Dump 100: Visoria; Humble Plains, Part 2

#Forspoken#Forspoken photo mode#athia#visoria#visoria: humble plain#bonus junoon in the distance#tanta monument#monument to love#pilgrim's refuge#humble plain: eastern refuge#breakbeast#ramoceros#breakbeast: ramoceros#humble plain: northern belfry#village#skinka#village: skinka#humble plain: western refuge#frey holland

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

This adorable mouse was considered extinct for over 100 years — until we found it hiding in plain sight

It turns out Gould's mouse isn't extinct.

Emily Roycroft, Australian National University

Australia has the world’s worst track record for wiping out mammals, with 34 species declared extinct since European colonisation. Many of these are humble native rodents, who’ve suffered the highest extinction rate of any mammal group.

But today, we bring some good news: one rodent species, Gould’s mouse (Pseudomys gouldii), is set to be crossed off Australia’s extinct species list. This means the number of Australia’s extinct mammals will drop from 34 to 33.

Our new research compared genome sequences across Australia’s rodents, including eight extinct species and their 42 living relatives. In a case of historical mistaken identity, we found the Gould’s mouse was genetically indistinguishable from another living species, the Shark Bay mouse (Pseudomys fieldi), also known by the Indigenous name “Djoongari” from the Pintupi and Luritja languages.

But it’s not all good news. A lack of genetic diversity in remaining populations means Djoongari are less resilient to changing environments, including from climate change. We can’t let this species die out — this time, there’d be no coming back.

Back from the dead

When Europeans colonised Australia, they rapidly and catastrophically changed the environments in which native species thrived. The introduction of feral cats, foxes and other invasive species, agricultural land clearing, inappropriate fire management, and new diseases decimated native rodent populations.

Along with many other native mammals, some rodent species were also intensely hunted for bounty in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

DNA from this specimen of Gould’s mouse, collected in 1837 from the Hunter Valley of NSW, reveals the species should no longer be considered extinct. Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London Photographer: C. Ching, Author provided

In 1837, a Gould’s mouse specimen was collected for the Natural History Museum, London, from the Hunter Valley of New South Wales. The last verified time it was seen alive was in 1857, near the border of Victoria and NSW.

After genomic analysis of these specimens, we found the species has been hiding in plain sight for more than 100 years, under a different name, thousands of kilometres away in Western Australia. Djoongari will now be reclassified under the scientific name Pseudomys gouldii.

Djoongari is a shaggy-coated mouse weighing 45 grams on average, making it twice the size of the invasive house mouse. It’s omnivorous, and feeds on a variety of flowers, leaves, fungi, insects and spiders. It also build tunnels and runways to travel at night, and uses above-ground nests as refuges during the day.

Not safe yet

The resurrection of the Gould’s mouse is positive news given Australia’s alarming rate of recent extinctions, but the species remains at risk.

Once occurring across mainland Australia, it now survives only on predator-free islands in Shark Bay, WA. Islands have been an important refuge for the species, protecting them from cats, foxes, diseases and other threats on the mainland.

Feral and pet cats are huge threats to small native animals. If you own a cat, make sure you keep it indoors to protect Australia’s wildlife. Shutterstock

Conservation efforts are underway to protect the mouse in Shark Bay, with insurance populations established on other nearby islands.

Now we know Djoongari once roamed as far east as the Hunter Valley in NSW, there’s greater scope to reintroduce the species to predator-proof protected areas on the mainland. This would mean more insurance populations, but also contribute towards restoring natural ecosystems on mainland Australia — also known as “rewilding”.

However, remnant populations of this once widespread species contain only a fraction of its original genetic diversity.

Genetic diversity is often used as a proxy for estimating the resilience of a species to threats and its potential to adapt to changes in its environment. When species have low genetic diversity, or are inbred, they are more susceptible to disease, and more likely to accumulate harmful genetic mutations.

Other eye-opening revelations

Our study also examined the genomes of seven other rodent species lost to extinction: the white-footed rabbit rat, lesser stick-nest rat, Bramble Cay melomys, short-tailed hopping mouse, long-tailed hopping mouse, big-eared hopping mouse and long-eared mouse.

Bramble cay melomys were declared extinct in 2016. Ian Bell, EHP, State of Queensland, CC BY-SA

In most cases, we found these now-extinct native rodents had relatively high genetic diversity immediately before they became extinct. High genetic diversity usually means large population sizes, suggesting native rodent populations were stable before European invasion.

This puts an end to any suggestion that these species were already on their way out prior to the arrival of Europeans.

Reports from early naturalists back up our findings. In 1846, John Cotton referred to the now-extinct white-footed rabbit rat as “the common rat of the country”. And in 1866, Gerard Krefft described the now-extinct lesser stick-nest rat as occurring in “great numbers”.

These species went from common to extinct in less than 150 years. That’s alarmingly fast by any standard.

It shows even though genetic diversity in now-extinct rodents was high prior to colonisation, it wasn’t enough. The environment and threats changed so dramatically and rapidly, these species didn’t have the chance to adapt.

There’s a clear lesson in all this

The threats to native wildlife brought by Europeans — including feral cat predation and land clearing — are ongoing. And under climate change, the environment as we know it is set to change further, dramatically.

It’s not enough to only establish insurance populations to save species. We need to control feral predators, protect and restore habitats, and curb emissions, so more species don’t endure a rapid wipe out.

In total, we’ve lost almost 100 species to extinction since 1788, and that’s just those we know about. In native rodents alone, in less than 150 years, the equivalent of more than 10 million years of unique evolutionary history has been lost forever.

Extinction doesn’t usually offer second chances, but we’ve now got another shot to protect Gould’s mouse. We need to act now, before it’s too late.

Emily Roycroft, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This adorable mouse was considered extinct for over 100 years — until we found it hiding in plain sight published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Photo

The Castle Filla

It is built on the top of a steep, rocky hill in the Lilandian plain and is visible over the whole area.

A medieval love story is associated with the castle. It belonged to the feudal lord Merito dalle Carceri but it was conquered by the legendary knight Likarius at the beginning of the Frankish occupation in the 13th century A.D. and handed over to the Emperor of Byzantium Michael the seventh.Likarius deserted the Frankish army for the sake of the beautiful widow, Feliza, and using the castle as his base, on behalf of Byzantium, he successively occupied the Frankish castles of Evia. When the Turks occupied Evia in 1470, they destroyed parts of the walls to weaken its defence.

The northern and western parts of the walls are better-preserved. As you go through the entrance on the northern side you will see the impressive ruins of a large building which was the mansion of the lord. The mansion was two-storeyed and there still remain on the second floor, the slits for the windows which are vaulted and decorated with ceramic tiles in the Byzantine style. Next to the mansion there are ruins of other buildings which served the various other purposes of the castle.

Licario, called Ikarios (Greek: Ἰκάριος) by the Greek chroniclers, was a Byzantine admiral of Italian origin in the 13th century. At odds with the Latin barons of his native Euboea, he entered the service of the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259–1282), and reconquered many of the Aegean islands for him in the 1270s. For his exploits, he was rewarded with Euboea as a fief and rose to the rank of megas konostaulosand megas doux, the first foreigner to do so.

Licario was born in Karystos in Latin-held Euboea (Negroponte), from a Vicentian father and a local woman. He was of humble origin, but able and ambitious. Serving as a knight under the Latin triarch Giberto II da Verona, he managed to win the heart of Felisa, sister of Giberto and widow of another triarch, Narzotto dalle Carceri. The match was met with disapproval by Felisa's family. They secretly married, but the marriage was cancelled by her relatives. Fleeing from their wrath, Licario sought refuge in the fort of Anemopylae near Cavo D'Oro. He repaired the strong fortress, assembled a small group of followers, and began raiding the surrounding estates, belonging to the island's nobles

At that time, the newly restored Byzantine Empire, under the leadership of Michael VIII Palaiologos, sought to recover Euboea, which was the major Latin insular possession in the Aegean Sea and a base for piratical activity directed against his lands. Furthermore, along with the Principality of Achaea it presented the major obstacle to his complete recovery of Greece. Already in 1269/1270, a Byzantine fleet under Alexios Doukas Philanthropenos had attacked and captured many Latin nobles, the town of Oreos.

Facing the persistent refusal of the island's barons to treat with him, desiring vengeance and eager for glory and wealth, Licario presented himself to Philanthropenos, offering his services. He, in turn, took him to the Emperor, who was eager to use the services of talented Westerners whenever he could, and had already bankrolled several Latin corsairs in his service. Licario became the Emperor's vassal according to Western feudal rules, and in turn was strengthened with imperial troops. Under the leadership of Licario, the Byzantines could now mount a serious attempt to conquer the island, while their forces were further augmented by many defections from the Greek population.[4]

The Byzantine forces, under Licario's command, now (in 1272/1273) launched a campaign that took the fortresses of Larmena, La Cuppa, Clisura and Manducho. The Lombard triarchs then appealed to their liege-lord, Prince William II of Achaea, and to Dreux de Beaumont, marshal of the Angevin Kingdom of Sicily. William was able to recover La Cuppa, but de Beaumont was defeated in a pitched battle and was subsequently recalled by Charles of Anjou.[5]Between then and 1275, according to the Venetian chronicler Marino Sanudo, Licario himself served in the Byzantine army in Asia Minor, where he scored a victory against the Turks

In 1276, following their great victory over the Lombard triarchs of Negroponte at the Battle of Demetrias, the Byzantines renewed their offensive in Euboea. Licario attacked his native Karystos, seat of the southern triarchy, and took it, after a long siege, in the same year. For this success, he was rewarded by Michael VIII with the whole island as a fief, and a noble Greek wife with a rich dowry. In turn, Licario pledged to provide 200 knights to the Emperor. Gradually, Licario reduced the Latin strongholds on the island, until, by 1278, he had seized almost all of it except for the capital, the city of Negroponte (Chalkis).

For his successes, Licario was rewarded with the post of megas konostaulos, head of the Latin mercenaries, and eventually appointed as megas doux after Philanthropenos's death in ca. 1276; the first foreigner to be thus honoured.[8] He commanded the Byzantine navy in a series of expeditions against the Latin-held Aegean islands. The first to fall was Skopelos, whose fortress was believed to be impregnable. Licario, however, knew that it lacked water supplies. Thus, he attacked it during the hot and dry summer of 1277 and forced its surrender. Its lord, Filippo Ghisi, was captured and sent to Constantinople; his other possessions, the islands of Skyros, Skiathos and Amorgos, were also taken soon after. After that, Licario went on to capture the islands of Kythera and Antikythera off the southern coast of the Morea, and later Kea, Astypalaia, and Santoriniin the Cyclades. The great island of Lemnos was also captured, although its lord, Paolo Navigajoso, withstood a three-year siege before surrendering.

Finally, in late 1279 or early 1280, he returned to Euboea, landing in the norther town of Oreos and moving south towards Negroponte. His forces by now included many Spanish and Catalan mercenaries (the first time the latter are mentioned in Greece) and even former adherents of Manfred of Sicily, who had fled to Greece after Manfred's defeat and death at the hands of Charles of Anjou. As he reached Negroponte, the triarch Giberto II da Verona, Felisa's brother, and John I de la Roche, the Duke of Athens, who were present at the city, rode out with their forces to meet him. The two armies met at the village of Vatondas, northeast of Negroponte. The battle resulted in a major victory for Licario: John de la Roche was unhorsed and captured, while Giberto was either killed (according to Sanudo) or captured and taken along with de la Roche as a prisoner to Constantinople, where, according to Nikephoros Gregoras, the sight of the hated renegade, moving triumphantly among the assembled Byzantine court, caused him to drop dead.

After Vatondas, Negroponte seemed about to fall into Licario's hands too. The city, however, was quickly reinforced by Jacques de la Roche, lord of Argos and Nauplia, who, along with the energetic Venetian bailo, Niccolo Morosini Rosso, led its defence. Facing determined resistance and possibly fearing an intervention of John I Doukas, ruler of Thessaly, Licario was forced to raise the siege. Licario then turned to reducing the remaining Latin strongholds on the island, becoming its total master except for the city of Negroponte itself, and ruling it from the fortress of Fillia. His fleet carried out further naval expeditions: the islands of Sifnos and Serifos were taken, and Licario's ships raided the Peloponnese.

Licario himself sailed to Constantinople, presenting Emperor Michael VIII with his captives. Then, at the height of his fame and success in ca. 1280, Licario disappears from the sources, and his subsequent fate is unknown. Most likely he lived in Constantinople and died there

His conquests proved temporary only, as the Byzantines were gradually evicted by the Venetians and the other Latin lords. Even in Euboea, Licario's major gain and personal fief, the Lombard barons managed to complete their reconquest of the entire island by 1296.Nevertheless, Licario proved one of the most successful military leaders in Michael VIII's employ, and his victories greatly enhanced the emperor's own standing and prestige amongst the Latins. The historian Deno John Geanakoplos ranks him, along with Michael's brother John Palaiologos, as the two men who caused the most damage to the Latin rulers of Greece

0 notes

Text

Forspoken Photo Dump 132: Visoria; Visorian Plateau, Part 9

#Forspoken#Forspoken photo mode#Athia#Visoria#Visorian Plateau#Fount of Blessing#Lilac Fount#tanta monument#monument to strength#breakbeasts#amphicyon#Visorian Plateau: Western Belfry#Village: Skinka#pilgrim's refuge#Humble Plain: Western Refuge#locked labyrinth#locked labyrinth: field#Visorian Plateau: Eastern Belfry#Humble Plain: Southern Belfry#giant nightmare carcass#bonus avoalet in the distance#relic of the tantas#Heimur Library#there might also be a bonus Junoon in the distance; it's hard to tell bc the skybox is clipping with the ground XD

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forspoken Photo Dump 125: Visoria; Visorian Plateau, Part 3

#Forspoken#Forspoken photo mode#athia#visoria#visorian plateau#pilgrim's refuge#visorian plateau refuge#locked labyrinth#locked labyrinth: west#Forspoken magic#frey's magic#purple magic#frey's magic: burrow#purple magic: burrow#visorian plateau belfry#ruins of mercador#tanta gate#visoria castle: main gate#frey holland#humble plain: western refuge#village: skinka#locked labyrinth: field#humble plain: southern belfry#breakbeast#thylacoleo

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forspoken Photo Dump 101: Visoria; Humble Plain, Part 3

#Forspoken#Forspoken photo mode#athia#visoria#visoria: humble plain#frey holland#humble plain: northern belfry#locked labyrinth#locked labyrinth: field#pilgrim's refuge#humble plain: western refuge#village#skinka#village: skinka#phantom lantern#oryggi lantern#bonus junoon in the distance#broken#breakborn#breakzombie#breakborn: breakzombie#visorian plateau: western belfry#visorian plateau: eastern belfry#locked labyrinth: west#cognoscents' guild#alum guild

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forspoken Photo Dump 128: Visoria; Visorian Plateau, Part 5

#Forspoken#Forspoken photo mode#athia#visoria#visorian plateau#ruins of huwn#pilgrims refuge#humble plain: western refuge#frey holland#visorian plateau: western belfry#fort sestina

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forspoken Photo Dump 102: Visoria; Humble Plain, Part 4

#Forspoken#Forspoken photo mode#athia#visoria#visoria: humble plain#tanta monument#monument to justice#village#skinka#vilage: skinka#humble plain: western refuge#humble plain: westen belfry#cognoscents' guild#alum guild#bonus junoon in the distance#monument to love

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forspoken Photo Dump 261 BONUS: Visoria Castle Skyline, Part 1

#Forspoken#Forspoken Photo Mode#Athia#Visoria#Visoria Castle#Visoria: Humble Plain#Locked Labyrinth#Locked Labyrinth: Field#Visorian Plateau: Western Belfry#Visorian Plateau: Eastern Belfry#Tanta Monument#Monument to Love#Monument to Justice#Pilgrim's Refuge#Humble Plain Refuge#Frey Holland#Cognoscents' Guild#Alum Guild#Partha

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forspoken Photo Dump 103: Visoria; Humble Plain, Part 5

#Forspoken#Forspoken photo mode#athia#visoria#visoria: humble plain#tanta monument#monument to love#pilgrim's refuge#humble plain: eastern refuge#locked labyrinth#locked labyrinth: field#humble plain: western belfry#village#skinka#village: skinka#cognoscents' guild#alum guild#bonus junoon in the distance#breakbeast#ramoceros#breakbeast: ramoceros

6 notes

·

View notes