#I also really did enjoy my history of american religion course even though the professor was a tough grader

Text

can't do this one as a poll bc there's endless choices but if you're in college/university or went to college/university what's been the most fun/enriching class you've had?

#for me it wasn't fun but the most enriching one I've had was the history of racism#learned a ton in that class#I also really did enjoy my history of american religion course even though the professor was a tough grader#he shattered my ego a couple times lmfao

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: I enjoyed reading your posts about Napoleon’s death and it’s quite timely given its the 200th anniversary of his death this year in May. I was wondering, because you know a lot about military history (your served right? That’s cool to fly combat helicopters) and you live in France but aren’t French, what your take was on Napoleon and how do the French view him? Do they hail him as a hero or do they like others see him like a Hitler or a Stalin? Do you see him as a hero or a villain of history?

5 May 1821 was a memorable date because Napoleon, one of the most iconic figures in world history, died while in bitter exile on a remote island in the South Atlantic Ocean. Napoleon Bonaparte, as you know rose from obscure soldier to a kind of new Caesar, and yet he remains a uniquely controversial figure to this day especially in France. You raise interesting questions about Napoleon and his legacy. If I may reframe your questions in another way. Should we think of him as a flawed but essentially heroic visionary who changed Europe for the better? Or was he simply a military dictator, whose cult of personality and lust for power set a template for the likes of Hitler?

However one chooses to answer this question can we just - to get this out of the way - simply and definitively say that Napoleon was not Hitler. Not even close. No offence intended to you but this is just dumb ahistorical thinking and it’s a lazy lie. This comparison was made by some in the horrid aftermath of the Second World War but only held little currency for only a short time thereafter. Obviously that view didn’t exist before Hitler in the 19th Century and these days I don’t know any serious historian who takes that comparison seriously.

I confess I don’t have a definitive answer if he was a hero or a villain one way or the other because Napoleon has really left a very complicated legacy. It really depends on where you’re coming from.

As a staunch Brit I do take pride in Britain’s victorious war against Napoleonic France - and in a good natured way rubbing it in the noses of French friends at every opportunity I get because it’s in our cultural DNA and it’s bloody good fun (why else would we make Waterloo train station the London terminus of the Eurostar international rail service from its opening in 1994? Or why hang a huge gilded portrait of the Duke of Wellington as the first thing that greets any visitor to the residence of the British ambassador at the British Embassy?). On a personal level I take special pride in knowing my family ancestors did their bit on the battlefield to fight against Napoleon during those tumultuous times. However, as an ex-combat veteran who studied Napoleonic warfare with fan girl enthusiasm, I have huge respect for Napoleon as a brilliant military commander. And to makes things more weird, as a Francophile resident of who loves living and working in France (and my partner is French) I have a grudging but growing regard for Napoleon’s political and cultural legacy, especially when I consider the current dross of political mediocrity on both the political left and the right. So for me it’s a complicated issue how I feel about Napoleon, the man, the soldier, and the political leader.

If it’s not so straightforward for me to answer the for/against Napoleon question then it It’s especially true for the French, who even after 200 years, still have fiercely divided opinions about Napoleon and his legacy - but intriguingly, not always in clear cut ways.

I only have to think about my French neighbours in my apartment building to see how divisive Napoleon the man and his legacy is. Over the past year or so of the Covid lockdown we’ve all gotten to know each other better and we help each other. Over the Covid year we’ve gathered in the inner courtyard for a buffet and just lifted each other spirits up.

One of my neighbours, a crusty old ex-general in the army who has an enviable collection of military history books that I steal, liberate, borrow, often discuss military figures in history like Napoleon over our regular games of chess and a glass of wine. He is from very old aristocracy of the ancien regime and whose family suffered at the hands of ‘madame guillotine’ during the French Revolution. They lost everything. He has mixed emotions about Napoleon himself as an old fashioned monarchist. As a military man he naturally admires the man and the military genius but he despises the secularisation that the French Revolution ushered in as well as the rise of the haute bourgeois as middle managers and bureaucrats by the displacement of the aristocracy.

Another retired widowed neighbour I am close to, and with whom I cook with often and discuss art, is an active arts patron and ex-art gallery owner from a very wealthy family that came from the new Napoleonic aristocracy - ie the aristocracy of the Napoleonic era that Napoleon put in place - but she is dismissive of such titles and baubles. She’s a staunch Republican but is happy to concede she is grateful for Napoleon in bringing order out of chaos. She recognises her own ambivalence when she says she dislikes him for reintroducing slavery in the French colonies but also praises him for firmly supporting Paris’s famed Comédie-Française of which she was a past patron.

Another French neighbour, a senior civil servant in the Elysée, is quite dismissive of Napoleon as a war monger but is grudgingly grateful for civil institutions and schools that Napoleon established and which remain in place today.

My other neighbours - whether they be French families or foreign expats like myself - have similarly divisive and complicated attitudes towards Napoleon.

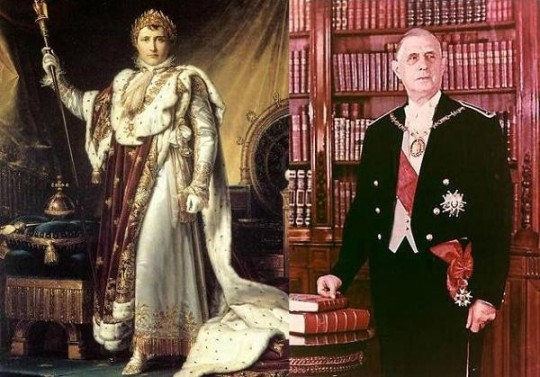

In 2010 an opinion poll in France asked who was the most important man in French history. Napoleon came second, behind General Charles de Gaulle, who led France from exile during the German occupation in World War II and served as a postwar president.

The split in French opinion is closely mirrored in political circles. The divide is generally down political party lines. On the left, there's the 'black legend' of Bonaparte as an ogre. On the right, there is the 'golden legend' of a strong leader who created durable institutions.

Jacques-Olivier Boudon, a history professor at Paris-Sorbonne University and president of the Napoléon Institute, once explained at a talk I attended that French public opinion has always remained deeply divided over Napoleon, with, on the one hand, those who admire the great man, the conqueror, the military leader and, on the other, those who see him as a bloodthirsty tyrant, the gravedigger of the revolution. Politicians in France, Boudon observed, rarely refer to Napoleon for fear of being accused of authoritarian temptations, or not being good Republicans.

On the left-wing of French politics, former prime minister Lionel Jospin penned a controversial best selling book entitled “the Napoleonic Evil” in which he accused the emperor of “perverting the ideas of the Revolution” and imposing “a form of extreme domination”, “despotism” and “a police state” on the French people. He wrote Napoleon was "an obvious failure" - bad for France and the rest of Europe. When he was booted out into final exile, France was isolated, beaten, occupied, dominated, hated and smaller than before. What's more, Napoleon smothered the forces of emancipation awakened by the French and American revolutions and enabled the survival and restoration of monarchies. Some of the legacies with which Napoleon is credited, including the Civil Code, the comprehensive legal system replacing a hodgepodge of feudal laws, were proposed during the revolution, Jospin argued, though he acknowledges that Napoleon actually delivered them, but up to a point, "He guaranteed some principles of the revolution and, at the same time, changed its course, finished it and betrayed it," For instance, Napoleon reintroduced slavery in French colonies, revived a system that allowed the rich to dodge conscription in the military and did nothing to advance gender equality.

At the other end of the spectrum have been former right-wing prime minister Dominique de Villepin, an aristocrat who was once fancied as a future President, a passionate collector of Napoleonic memorabilia, and author of several works on the subject. As a Napoleonic enthusiast he tells a different story. Napoleon was a saviour of France. If there had been no Napoleon, the Republic would not have survived. Advocates like de Villepin point to Napoleon’s undoubted achievements: the Civil Code, the Council of State, the Bank of France, the National Audit office, a centralised and coherent administrative system, lycées, universities, centres of advanced learning known as école normale, chambers of commerce, the metric system, and an honours system based on merit (which France has to this day). He restored the Catholic faith as the state faith but allowed for the freedom of religion for other faiths including Protestantism and Judaism. These were ambitions unachieved during the chaos of the revolution. As it is, these Napoleonic institutions continue to function and underpin French society. Indeed, many were copied in countries conquered by Napoleon, such as Italy, Germany and Poland, and laid the foundations for the modern state.

Back in 2014, French politicians and institutions in particular were nervous in marking the 200th anniversary of Napoleon's exile. My neighbours and other French friends remember that the commemorations centred around the Chateau de Fontainebleau, the traditional home of the kings of France and was the scene where Napoleon said farewell to the Old Guard in the "White Horse Courtyard" (la cour du Cheval Blanc) at the Palace of Fontainebleau. (The courtyard has since been renamed the "Courtyard of Goodbyes".) By all accounts the occasion was very moving. The 1814 Treaty of Fontainebleau stripped Napoleon of his powers (but not his title as Emperor of the French) and sent him into exile on Elba. The cost of the Fontainebleau "farewell" and scores of related events over those three weekends was shouldered not by the central government in Paris but by the local château, a historic monument and UNESCO World Heritage site, and the town of Fontainebleau.

While the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution that toppled the monarchy and delivered thousands to death by guillotine was officially celebrated in 1989, Napoleonic anniversaries are neither officially marked nor celebrated. For example, over a decade ago, the president and prime minister - at the time, Jacques Chirac and Dominque de Villepin - boycotted a ceremony marking the 200th anniversary of the battle of Austerlitz, Napoleon's greatest military victory. Both men were known admirers of Napoleon and yet political calculation and optics (as media spin doctors say) stopped them from fully honouring Napoleon’s crowning military glory.

Optics is everything. The division of opinion in France is perhaps best reflected in the fact that, in a city not shy of naming squares and streets after historical figures, there is not a single “Boulevard Napoleon” or “Place Napoleon” in Paris. On the streets of Paris, there are just two statues of Napoleon. One stands beneath the clock tower at Les Invalides (a military hospital), the other atop a column in the Place Vendôme. Napoleon's red marble tomb, in a crypt under the Invalides dome, is magnificent, perhaps because his remains were interred there during France's Second Empire, when his nephew, Napoleon III, was on the throne.

There are no squares, nor places, nor boulevards named for Napoleon but as far as I know there is one narrow street, the rue Bonaparte, running from the Luxembourg Gardens to the River Seine in the old Latin Quarter. And, that, too, is thanks to Napoleon III. For many, and I include myself, it’s a poor return by the city to the man who commissioned some of its most famous monuments, including the Arc de Triomphe and the Pont des Arts over the River Seine.

It's almost as if Napoleon Bonaparte is not part of the national story.

How Napoleon fits into that national story is something historians, French and non-French, have been grappling with ever since Napoleon died. The plain fact is Napoleon divides historians, what precisely he represents is deeply ambiguous and his political character is the subject of heated controversy. It’s hard for historians to sift through archival documents to make informed judgements and still struggle to separate the man from the myth.

One proof of this myth is in his immortality. After Hitler’s death, there was mostly an embarrassed silence; after Stalin’s, little but denunciation. But when Napoleon died on St Helena in 1821, much of Europe and the Americas could not help thinking of itself as a post-Napoleonic generation. His presence haunts the pages of Stendhal and Alfred de Vigny. In a striking and prescient phrase, Chateaubriand prophesied the “despotism of his memory”, a despotism of the fantastical that in many ways made Romanticism possible and that continues to this day.

The raw material for the future Napoleon myth was provided by one of his St Helena confidants, the Comte de las Cases, whose account of conversations with the great man came out shortly after his death and ran in repeated editions throughout the century. De las Cases somehow metamorphosed the erstwhile dictator into a herald of liberty, the emperor into a slayer of dynasties rather than the founder of his own. To the “great man” school of history Napoleon was grist to their mill, and his meteoric rise redefined the meaning of heroism in the modern world.

The Marxists, for all their dislike of great men, grappled endlessly with the meaning of the 18th Brumaire; indeed one of France’s most eminent Marxist historians, George Lefebvre, wrote what arguably remains the finest of all biographies of him.

It was on this already vast Napoleon literature, a rich terrain for the scholar of ideas, that the great Dutch historian Pieter Geyl was lecturing in 1940 when he was arrested and sent to Buchenwald. There he composed what became one of the classics of historiography, a seminal book entitled Napoleon: For and Against, which charted how generations of intellectuals had happily served up one Napoleon after another. Like those poor souls who crowded the lunatic asylums of mid-19th century France convinced that they were Napoleon, generations of historians and novelists simply could not get him out of their head.

The debate runs on today no less intensely than in the past. Post-Second World War Marxists would argue that he was not, in fact, revolutionary at all. Eric Hobsbawm, a notable British Marxist historian, argued that ‘Most-perhaps all- of his ideas were anticipated by the Revolution’ and that Napoleon’s sole legacy was to twist the ideals of the French Revolution, and make them ‘more conservative, hierarchical and authoritarian’.

This contrasts deeply with the view William Doyle holds of Napoleon. Doyle described Bonaparte as ‘the Revolution incarnate’ and saw Bonaparte’s humbling of Europe’s other powers, the ‘Ancien Regimes’, as a necessary precondition for the birth of the modern world. Whatever one thinks of Napoleon’s character, his sharp intellect is difficult to deny. Even Paul Schroeder, one of Napoleon’s most scathing critics, who condemned his conduct of foreign policy as a ‘criminal enterprise’ never denied Napoleon’s intellect. Schroder concluded that Bonaparte ‘had an extraordinary capacity for planning, decision making, memory, work, mastery of detail and leadership’. The question of whether Napoleon used his genius for the betterment or the detriment of the world, is the heart of the debate which surrounds him.

France's foremost Napoleonic scholar, Jean Tulard, put forward the thesis that Bonaparte was the architect of modern France. "And I would say also pâtissier [a cake and pastry maker] because of the administrative millefeuille that we inherited." Oddly enough, in North America the multilayered mille-feuille cake is called ‘a napoleon.’ Tulard’s works are essential reading of how French historians have come to tackle the question of Napoleon’s legacy. He takes the view that if Napoleon had not crushed a Royalist rebellion and seized power in 1799, the French monarchy and feudalism would have returned, Tulard has written. "Like Cincinnatus in ancient Rome, Napoleon wanted a dictatorship of public salvation. He gets all the power, and, when the project is finished, he returns to his plough." In the event, the old order was never restored in France. When Louis XVIII became emperor in 1814, he served as a constitutional monarch.

In England, until recently the views on Napoleon have traditionally less charitable and more cynical. Professor Christopher Clark, the notable Cambridge University European historian, has written. "Napoleon was not a French patriot - he was first a Corsican and later an imperial figure, a journey in which he bypassed any deep affiliation with the French nation," Clark believed Napoleon’s relationship with the French Revolution is deeply ambivalent.

Did he stabilise the revolutionary state or shut it down mercilessly? Clark believes Napoleon seems to have done both. Napoleon rejected democracy, he suffocated the representative dimension of politics, and he created a culture of courtly display. A month before crowning himself emperor, Napoleon sought approval for establishing an empire from the French in a plebiscite; 3,572,329 voted in favour, 2,567 against. If that landslide resembles an election in North Korea, well, this was no secret ballot. Each ‘yes’ or ‘no’ was recorded, along with the name and address of the voter. Evidently, an overwhelming majority knew which side their baguette was buttered on.

His extravagant coronation in Notre Dame in December 1804 cost 8.5 million francs (€6.5 million or $8.5 million in today's money). He made his brothers, sisters and stepchildren kings, queens, princes and princesses and created a Napoleonic aristocracy numbering 3,500. By any measure, it was a bizarre progression for someone often described as ‘a child of the Revolution.’ By crowning himself emperor, the genuine European kings who surrounded him were not convinced. Always a warrior first, he tried to represent himself as a Caesar, and he wears a Roman toga on the bas-reliefs in his tomb. His coronation crown, a laurel wreath made of gold, sent the same message. His icon, the eagle, was also borrowed from Rome. But Caesar's legitimacy depended on military victories. Ultimately, Napoleon suffered too many defeats.

These days Napoleon the man and his times remain very much in fashion and we are living through something of a new golden age of Napoleonic literature. Those historians who over the past decade or so have had fun denouncing him as the first totalitarian dictator seem to have it all wrong: no angel, to be sure, he ended up doing far more at far less cost than any modern despot. In his widely praised 2014 biography, Napoleon the Great, Andrew Roberts writes: “The ideas that underpin our modern world - meritocracy, equality before the law, property rights, religious toleration, modern secular education, sound finances, and so on - were championed, consolidated, codified and geographically extended by Napoleon. To them he added a rational and efficient local administration, an end to rural banditry, the encouragement of science and the arts, the abolition of feudalism and the greatest codification of laws since the fall of the Roman empire.”

Roberts partly bases his historical judgement on newly released historical documents about Napoleon that were only available in the past decade and has proved to be a boon for all Napoleonic scholars. Newly released 33,000 letters Napoleon wrote that still survive are now used extensively to illustrate the astonishing capacity that Napoleon had for compartmentalising his mind - he laid down the rules for a girls’ boarding school on the eve of the battle of Borodino, for example, and the regulations for Paris’s Comédie-Française while camped in the Kremlin. They also show Napoleon’s extraordinary capacity for micromanaging his empire: he would write to the prefect of Genoa telling him not to allow his mistress into his box at the theatre, and to a corporal of the 13th Line regiment warning him not to drink so much.

For me to have my own perspective on Napoleon is tough. The problem is that nothing with Napoleon is simple, and almost every aspect of his personality is a maddening paradox. He was a military genius who led disastrous campaigns. He was a liberal progressive who reinstated slavery in the French colonies. And take the French Revolution, which came just before Napoleon’s rise to power, his relationship with the French Revolution is deeply ambivalent. Did he stabilise it or shut it down? I agree with those British and French historians who now believe Napoleon seems to have done both.

On the one hand, Napoleon did bring order to a nation that had been drenched in blood in the years after the Revolution. The French people had endured the crackdown known as the 'Reign of Terror', which saw so many marched to the guillotine, as well as political instability, corruption, riots and general violence. Napoleon’s iron will managed to calm the chaos. But he also rubbished some of the core principles of the Revolution. A nation which had boldly brought down the monarchy had to watch as Napoleon crowned himself Emperor, with more power and pageantry than Louis XVI ever had. He also installed his relatives as royals across Europe, creating a new aristocracy. In the words of French politician and author Lionel Jospin, 'He guaranteed some principles of the Revolution and at the same time, changed its course, finished it and betrayed it.'

He also had a feared henchman in the form of Joseph Fouché, who ran a secret police network which instilled dread in the population. Napoleon’s spies were everywhere, stifling political opposition. Dozens of newspapers were suppressed or shut down. Books had to be submitted for approval to the Commission of Revision, which sounds like something straight out of George Orwell. Some would argue Hitler and Stalin followed this playbook perfectly.

But here come the contradictions. Napoleon also championed education for all, founding a network of schools. He championed the rights of the Jews. In the territories conquered by Napoleon, laws which kept Jews cooped up in ghettos were abolished. 'I will never accept any proposals that will obligate the Jewish people to leave France,' he once said, 'because to me the Jews are the same as any other citizen in our country.'

He also, crucially, developed the Napoleonic Code, a set of laws which replaced the messy, outdated feudal laws that had been used before. The Napoleonic Code clearly laid out civil laws and due processes, establishing a society based on merit and hard work, rather than privilege. It was rolled out far beyond France, and indisputably helped to modernise Europe. While it certainly had its flaws – women were ignored by its reforms, and were essentially regarded as the property of men – the Napoleonic Code is often brandished as the key evidence for Napoleon’s progressive credentials. In the words of historian Andrew Roberts, author of Napoleon the Great, 'the ideas that underpin our modern world… were championed by Napoleon'.

What about Napoleon’s battlefield exploits? If anything earns comparisons with Hitler, it’s Bonaparte’s apparent appetite for conquest. His forces tore down republics across Europe, and plundered works of art, much like the Nazis would later do. A rampant imperialist, Napoleon gleefully grabbed some of the greatest masterpieces of the Renaissance, and allegedly boasted, 'the whole of Rome is in Paris.'

Napoleon has long enjoyed a stellar reputation as a field commander – his capacities as a military strategist, his ability to read a battle, the painstaking detail with which he made sure that he cold muster a larger force than his adversary or took maximum advantage of the lie of the land – these are stuff of the military legend that has built up around him. It is not without its critics, of course, especially among those who have worked intensively on the later imperial campaigns, in the Peninsula, in Russia, or in the final days of the Empire at Waterloo.

Doubts about his judgment, and allegations of rashness, have been raised in the context of some of his victories, too, most notably, perhaps, at Marengo. But overall his reputation remains largely intact, and his military campaigns have been taught in the curricula of military academies from Saint-Cyr to Sandhurst, alongside such great tacticians as Alexander the Great and Hannibal.

Historians may query his own immodest opinion that his presence on the battlefield was worth an extra forty thousand men to his cause, but it is clear that when he was not present (as he was not for most of the campaign in Spain) the French were wont to struggle. Napoleon understood the value of speed and surprise, but also of structures and loyalties. He reformed the army by introducing the corps system, and he understood military aspirations, rewarding his men with medals and honours; all of which helped ensure that he commanded exceptional levels of personal loyalty from his troops.

Yet, I do find it hard to side with the more staunch defenders of Napoleon who say his reputation as a war monger is to some extent due to British propaganda at the time. They will point out that the Napoleonic Wars, far from being Napoleon’s fault, were just a continuation of previous conflicts that arose thanks to the French Revolution. Napoleon, according to this analysis, inherited a messy situation, and his only real crime was to be very good at defeating enemies on the battlefield. I think that is really pushing things too far. I mean deciding to invade Spain and then Russia were his decisions to invade and conquer.

He was, by any measure, a genius of war. Even his nemesis the Duke of Wellington, when asked who the greatest general of his time was, replied: 'In this age, in past ages, in any age, Napoleon.'

I will qualify all this and agree that Napoleon’s Russian campaign has been rightly held up as a fatal folly which killed so many of his men, but this blunder – epic as it was – should not be compared to Hitler’s wars of evil aggression. Most historians will agree that comparing the two men is horribly flattering to Hitler - a man fuelled by visceral, genocidal hate - and demeaning to Napoleon, who was a product of Enlightenment thinking and left a legacy that in many ways improved Europe.

Napoleon was, of course, no libertarian, and no pluralist. He would tolerate no opposition to his rule, and though it was politicians and civilians who imposed his reforms, the army was never far behind. But comparisons with twentieth-century dictators are well wide of the mark. While he insisted on obedience from those he administered, his ideology was based not on division or hatred, but on administrative efficiency and submission to the law. And the state he believed in remained stubbornly secular.

In Catholic southern Europe, of course, that was not an approach with which it was easy to acquiesce; and disorder, insurgency and partisan attacks can all be counted among the results. But these were principles on which the Emperor would not and could not give ground. If he had beliefs they were not religious or spiritual beliefs, but the secular creed of a man who never forgot that he owed both his military career and his meteoric political rise to the French Revolution, and who never quite abandoned, amidst the monarchical symbolism and the court pomp of the Empire, the republican dreams of his youth. When he claimed, somewhat ambiguously, after the coup of 18 Brumaire that `the Revolution was over’, he almost certainly meant that the principles of 1789 had at last been consummated, and that the continuous cycle of violence of the 1790s could therefore come to an end.

When the Empire was declared in 1804, the wording, again, might seem curious, the French being informed that the `Republic would henceforth be ruled by an Emperor’. Napoleon might be a dictator, but a part at least of him remained a son of the Enlightenment.

The arguments over Napoleon’s status will continue - and that in itself is a testament to the power of one of the most complex figures ever to straddle the world’s stage.

Will the fascination with Napoleon continue for another 200 years?

In France, at least, enthusiasm looks set to diminish. Napoleon and his exploits are scarcely mentioned in French schools anymore. Stéphane Guégan, curator of the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, which, among other First Empire artworks, houses a plaster model of Napoleon dressed as a Roman emperor astride a horse, has described France's fascination with him as ‘a national illness.’ He believes that the people who met him were fascinated by his charm. And today, even the most hostile to Napoleon also face this charm. So there is a difficulty to apprehend the duality of this character. As he wrote, “He was born from the revolution, he extended and finished it, and after 1804 he turns into a despot, a dictator.”

In France, Guégan aptly observes, there is a kind of nostalgia, not for dictatorship but for strong leaders. "Our age is suffering a lack of imagination and political utopia,"

Here I think Guégan is onto something. Napoleon’s stock has always risen or fallen according to the vicissitudes of world events and fortunes of France itself.

In the past, history was the study of great men and women. Today the focus of teaching is on trends, issues and movements. France in 1800 is no longer about Louis XVI and Napoleon Bonaparte. It's about the industrial revolution. Man does not make history. History makes men. Or does it? The study of history makes a mug out of those with such simple ideological driven conceits.

For two hundred years on, the French still cannot agree on whether Napoleon was a hero or a villain as he has swung like a pendulum according to the gravitational pull of historical events and forces.

The question I keep asking of myself and also to French friends with whom I discuss such things is what kind of Napoleon does our generation need?

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#napoleon#french#french history#history#military history#bonaparte#france#historiography#republic#historians#personal

417 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

Ancient Writer of dreams and nightmares: I am 71 (-one month), and have been writing (making up tales) since I was three. I can still remember my Pawpaw whittling a pencil for me, and Mawmaw tearing a piece of brown grocery bag for me to write on. They weren't 'poor', but writing paper wasn't to be wasted on a 'kid' just for fun. I carefully scripted my first short story.

Of course my 'letters' looked more like ancient Hanguel, so I had to read it to my "captured" audience. I really don't remember the story, but as my grandparents had a yard full of chickens and my dog, Mutt, liked to chase them (because of this we 'both' got into trouble -- because I always joined the chase) I most probably wrote about that.

My Pawpaw was a story-teller. For several years I thought there really was a baby found in the wilds of the African jungle and raised by the great apes. I thought he was the luckiest babe, EVER!

Then I found Pawpaw's books about three years after he died. I was eleven when he died, and felt that my best friend had abandoned me. But when I found those books I realized just where Tarzan actually came from and went to. I read everyone of those books and got the complete picture. THEN..

Well, Pawpaw also told stories of Daniel Boone and Davey Crocket...before I saw them on Disney. Then, of course, I went to school and learned what I already knew. Pawpaw was an excellent story-teller and never mixed up his facts, time-lines, or characters.

Growing up under his influence had a lot to do with how I developed as a story-teller. At family gatherings when I meet cousins I haven't seen in decades, they STILL remember me and the stories that I used to tell them. My children and grandchildren have grown up with me re-telling Pawpaw's old stories, and sharing many that I made up on the spot.

But I think what I read in my early years developed my writing style.

I was just turned eight when I read my first Shakespeare, MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM. He was my first favorite author. Then I was forced to read Romeo and Juliet. I was disgusted by the fact that TRAGEDY was made famous as a ROMANCE! Even at the innocent (then) age of fourteen, I was disgusted with the idea that it was considered romantic for 'anyone', let alone 'teenagers' to commit suicide over unrequited love.

My sister (now 68) and I recently discussed this play. Because she had a 'forbidden' teenage love, she said that she related to the story (even though she had never read it). GASP! It was required reading in ninth grade!

I remember our dad breaking up my sister and her boyfriend, who was really cool. He was a hard working farm boy who had saved his money to buy a motorcycle. AND his own car. But he wasn't good enough for my sister. smh

I always thought her story would make a great LifeTime movie. But I'm not touching it. She would 'skin me' for sharing with the world her broken heart. And if I added the stuff that sells today, she'd scalp me for lying. Not a win situation at all. So, I will write notes in my "Random Jottings Journal" for future decendants who might grow into writers or story-tellers.

By the way, the title "RANDOM JOTTINGS" came from a sci-fi book that I read as a kid in the fifties. I don't remember the author, although I'm pretty sure it 'might' be from a Heinlein juvenile book. But I've never found a reference to any sci-fi books using that term. SO!!! If anyone recognizes "RANDOM JOTTINGS", which was a note book that a professor/scientist/genius used to keep his 'thoughts', PLEASE share the author's name and the title of the book!!! Thank You.

In the meantime, I referenced Shakespeare. James Oliver Curwood wrote about Kazan, the Wolf Dog, and later Baree, Son of Kazan. From those two books, read when I was eleven, I searched for and found other books about Canada. Later there was Walter Farley, author of the Black Stallion, and the Island Stallion series. I think I met my FIRST friendly alien in the Island Stallion Races.

Of course, Edgar Rice Burroughs taught me much false history about the jungles of Africa, as well as the Moon and Mars. But I loved every 'read-under-the-covers-with a-flashlight' minute! I believe he was a contemporary of Zane Grey, because he wrote a few non-jungle and non-space stories, too. Which led me to Zane Grey.

Having read both of their biographies at a young age, I learned about the hardships of being a writer. I should say 'the hardships of a struggling writer'. I have never had a problem writing. Since I write for 'fun' and not 'profit', the few short stories I've had published were by local press, and a State magazine.

No, my struggles have centered around graduating high school, and completing college, stuggling to satisfy my husband, a 'Mr. Spock in the Flesh' personality, and later raising two children without benefit of parental support or child support. But we survived in the middle of laughter and many tears. And my made up stories about children lost in the woods who were rescued by a great friendly bear, or wolf. Or dog. And sometimes by a great Black Panther - a by product of one of my Pawpaw's 'local historical tales'.

I understand that publishers detest stories that begin with "It was a dark and stormy night.." But let me tell you, some of the BEST bedtime stories occur on stormy nights when the power has gone out, and it's too hot for candles or lanterns. That shadow that stands darkest in the corner and seems to be moving towards the bed is actually grandma come to check on the kids, and stands quiet so not to disturb the kids if they're already asleep. But since they are awake, and they see her 'shadow', she becomes the old crone who lives in the castle dungeon, and has slipped her chains to visit with the 'wee folk'. But there are no fairies out on such a blustery night, so the old crone comes to visit with the 'wee bairn', who fall all over themselves to get out of bed and sit around her to hear her stories of 'long ago' and other 'dark and stormy nights'. Again -- unpublished, because publishers don't like ... LOL

Of course there's always On-Line publishing. But that involves more work than actual writing.

Back to the writrs who influenced my writing:

While I enjoy a good Western, an adventurous space trek, or time travel, I also enjoy the occasional Historical Romance. Georgette Heyer was my first! I still re-read her amazing books. Of course there's Jane Austen.

There are a myriad of modern writers that I have read over the last five decades. Heinlen, Asimov, Norton, Bradley, McCaffrey, Moon, Stirling, Krentz/Castle/Quick, and Moening, just to name a few of the ones whose books I have in my personal library.

Those older authors did affect my writing style to develope as I read their stories. The later authors helped me to move into the late 20th century. But I'm not so sure that I like the 21st century so much. It's all about being politically 'correct'. If you aren't ashamed of your gender, your race, your country, your religion, your culture, your family, your history, then you are prejudiced. That's just too much guilt to have to live with.

I'm still dealing with my mom's death from ten years ago. I was her care-giver for five years. Her doctor had given her nine months. I still worry if I did enough for her in those last years.

And though my children are grown with their own families, I worry that I wasn't a good enough parent. And I worthy as a grandmother? How was I as an older sister? I was responsible as a moral guide when our parents were at work. Was I a good neighbor? A good support in our Church? And Hollywood wants me to feel guilt about something I can't change?!!

I'm an old woman who still likes being a woman and enjoys liking men. I'm not just white. I'm also mixed with a bit of Native American, and even a drop of -- OMG!!! --- Black. snicker.

That's a serious joke, because as a kid I had a recuring nightmare that I was a black man being judged by a group of people in white hoods I was hanged amidst their fiery torches. I always thought those white hoods represented the Catholic Church, because at that young age I didn't know about the Ku Klux Klan. Even though I grew up in the South, my family was not involved with that group of out-lawrey. Thank God!

Still, I'm supposed to feel shame? For something not even my family supported.

I've always believed there's a hint of Fae in my DNA. Because I love dancing in the light of the full moon, and flying with the owls who perch outside my bedroom window and call to invite me to follow the moon's shadow. If I am part Fae, I know it came from my mother's people. They were Irish mixed with Alabama Indians who believed in the Nunnehi aka Immortal, and the Yunwi Tsunsdi, aka Little People.

ALSO, while there's no DNA proof of ancestry, I've always been a 'closet Chinese'.

In the Fifties, when WW2 was still fresh, and we were involved with the 'Korean Conflict', and at odds with China, I would sneak around the radio, turn down the volume, and tune into 'that wierd channel' that sometimes played Opera, or Chinese music. Ahhh. I would close my eyes and wander through the few visuals I'd found in books, or the occasional movie. (before color tv)

A year or two ago I was totally depressed and disgusted with American TV. Hollywood has become so political, so wierd. Their programming is no longer for entertainment, but to 'educate, enlighten, or to inform'. zzzzz

Then I found KDrama!!!!! Korean TV. Japanese Tv. squeal!!! Chinese TV.

The rom/coms are sweet and 'pure'. Okay. I'm realistic. This is not a reflection of real life on any planet. But the innocence of the early 1950s programs is there. Similar to Disney's 'Summer Magic'. I'm happy with those dramas that remind me of thati nnocence. I have found a few dramas that shared more than I cared for, and I do enjoy an occasional 'romp'. But I've always preferred the Lady and Gentleman characters.

And watching these programs have reminded me of those fairy tales and legends from my childhood that had been sprinkled with the Occasional Oriental myth, legend, and children's tale.

Then I remembered my FIRST historical legend. "The White Stag" by Kate Seredy, is the tale of Atilla the Hun!

I recently found a copy of that book and am waiting for a quiet time, when the power is out and there's nothing to do. Then I will use one of the many flashlights I bought for a huge hurricane, and relax on the sofa beneath an open window and read this legend once again. I live in Florida. The odds of this happening increases as the summer progresses. I can't wait to learn if my memory of this tale of Atilla the Hun remained true, or has been distorted in the last half of a century.

Most of the tales that I write involve space adventures, the occasioanl ghost, and encounters with fairies, the evil ones, not the romantic ideal fairy. smh

I've never been very good with romance or comedy. But thanks to the recent influence of the Asian productions, I have re-formatted one of my dark adventures and turned it into a rom/com.

I love a good joke, but very seldom get the point or see the humor. And I can NEVER remember the punch line if I try to share a joke. My family have said they will write on my tombstone --

"I don't remember the punchline ... but it was funny."

But as I write humorous lines or events I find myself laughing. Or crying at sad events. And I am all 'giggly' when I write what is supposed to be innocent romance between a young and shy couple. But I have never felt that my own reactions were a true guide to how the story might come across to a 'reader'.

As it happens, I have two sisters younger than I am. My middle sister is bored easily and immediately redirects our conversation to something about 'her'. Okay. I understand. She is lonely, needy, and maybe a bit selfish? Not judging. She's the 'middle child' and that's her excuse. ROFL..

But the youngest sister is my greatest fan who declares that I am an awesome writer. "I love you, sister, dear."

So she visited me last week and patiently listened as I read the first chapter. She listened quietly, and I wondered if I had 'read her to sleep'. sigh. Boring books are often the best sleeping pill. Then I heard her laugh.

Squeals/Dancing/hooting/flying around the room in ecstasy!!

Okay! At least one person has laughed. And she's not that easily 'tickled'.

So, I will always carry on and write. But now I feel that at least I might be following a path strewn with "Black-Eyed-Susans, honeybees, butterflies, and bunnies".

I don't know if anyone will read this, or will enjoy it. I hope so. While sharing bits of my youth, my worries, and my concern about certain ones of my 'stories', I actually had ideas for developing 'new' stories.

I am always amazed when writers say they are 'blocked'. I have only to open my eyes to see a world around me that no one else can envision. I listen to a song, and I'm in a different world, time, planet. A gift from Pawpaw, and Mother's DNA.

It is my oldest granddaughter's birthday this month, and I don't know what to give her for her birthday. But when she was younger, she always asked me to tell her a story. I think that I will pull out one of my OLD/ANCIENT tales that I wrote when her dad was her age and make it into a book for her.

p---leia aka Mamma KayeLee

7/19/2020

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Cancel Culture’ Is as Old as Religion, And It’s Only a Thing Because of Who’s Doing the Cancelling | Religion Dispatches

I don’t understand “cancel culture.” I mean, I understand what people mean, but I don’t quite understand why those decrying it claim that it’s something new.

I’ve often thought the term itself is born from social media which portends to inaugurate the democratization of knowledge but really functions to introduce the democratization of opinion. In some way, of course, opinion was always democratized; free speech enables me to say whatever I want (given certain caveats) but it doesn’t, nor did it ever, give me the right to say it wherever I want.

In some way, cancel culture has always existed, mostly in the hands of editors of opinion pages and letters to the editor; university committees who decide who’s invited to speak and who isn’t; people who evaluate material for publication, etc. That is, there was always a process of vetting, and that vetting was not always pure and without ulterior motives.

The lines of communication between what I happen to think and your ear have never been unmediated unless you happened to pass by my front lawn as I stood there and expounded on the ills of the world. Before this present moment, for example, would anyone think of accusing a newspaper of “cancel culture” because they rejected one’s letter to the editor (if so, I would have been the victim of cancel culture many times over).

But something has changed. Let me cite a few examples. When I was a young assistant professor at The Jewish Theological Seminary I received many invitations from Conservative synagogues to speak about my research, or on topical matters. I enjoyed such opportunities. Once I began publishing essays criticizing Israel’s occupation, the invitations stopped. Pretty abruptly. As I told a friend at the time, I could close my eyes and envision my name being summarily plucked from the Rolodexes in synagogue offices. Did that disturb me? Not really. While I certainly missed the extra income, I knew that was the price I paid for making my views public on a contentious matter. At no point did I think I was being cancelled. In fact, I was happy that at least they were reading my essays.

A second example happened more recently. I read an essay in an online journal on a topic I know something about that I felt was very problematic, not because I disagreed with the views expressed therein (although I did), but because the essay contained errors, inaccuracies, leaps of logic, and was poorly argued. I wrote to the editors of the journal to express my dissatisfaction. In response I received a very mean-spirited response from one editor accusing me of “bullying a young writer” (the editor called him “a kid”) and claiming he was just “living his truth” (he was an American who had immigrated to Israel).

First, I had assumed he was closer to my age. But if readers were meant to account for the writer’s age shouldn’t his work have been presented in a way that reflected this? Second, I had no idea, nor did I care, where he lived. And third, I didn’t quite understand being accused of “bullying” since I never wrote to the author and never made my views of the essay public. To this day, the unnamed author still has no idea how I felt about his essay. I simply wrote privately to the editors. While I wasn’t quite accused of “cancel culture,” that seemed to be the underlying message of the editor’s remarks. In this editor’s view I was, in some way, questioning, by privately discrediting, the right for this author to state his views.

Finally, when someone crosses a line on my Facebook thread I often block them. Before doing so, I write to them to tell them I’m blocking them, and that they have the right to say whatever they want in this world, but they don’t have the right to say whatever they want on my Facebook page. While my page is public, it’s still mine and I have the right to curate it as I see fit. I offer them the opportunity to apologize or retract their remarks and if they choose not to, I block them. I’ve been accused in this instance of “cancel culture”; that is, of preventing him or her from expressing their views and censoring them. The elision of whatever and wherever seems to have grown roots in our psyche.

So in these three moments—one where I’m not invited to speak at venues because of my views (perfectly legitimate), one where an editor accuses me of preventing someone from “living their truth” by privately criticizing their essay (illegitimate), and one where I am accused of ‘cancelling’ someone for saying whatever racist or misogynist nonsense on my Facebook page (necessary, in my view)—we find ourselves in a state of confusion where the right to say whatever we want has morphed into the right to say it wherever we want. Where public space and the democratization of opinion now enables us to confuse whatever and wherever.

People can be, and continue to be, excluded (cancelled) for all kinds of reasons; race, religion, creed, sexual orientation. We now have legal structures in place to try to alleviate or minimize that kind of illegitimate discrimination. We’ve decided that those criteria for exclusion are unacceptable in our society.

What it seems “cancel culture” is introducing is another layer; political or ideological discrimination. And in doing that, weaponizing something that’s existed for a long time: exclusion for other reasons. Kind of like how white people who oppose affirmative action do so because suddenly they are disadvantaged, though they had no problem for centuries when it was reversed. But is political discrimination valid? If I edit a journal and reject an essay because I find its political or ideological foundations unacceptable, is that discriminatory? Should it be? The expansion of discriminatory practice to include political or ideological differences in regard to who gets to say what, where, is perhaps the place to get a deeper sense of what’s going on.

Yes, even the Talmud

Recently, Will Berkovitz, a rabbi and CEO of Jewish Family Service in Washington State published an opinion piece arguing that, as the headline states, “The Talmud has a lesson for our cancel-culture world.” In it, he argues that the Talmud, a product of a small cadre of Jewish sages in Babylonia from the third to sixth centuries CE, can be a model for the tolerance and diversity of opinions that our present moment needs. That it can teach us a lesson about cancel culture.

Others have made similar arguments that the Talmud is a lesson in pluralism as its pages contain legal discussions that include minority and rejected opinions. In fact, one of its tractates called Ediyot (‘Testimonies’) even discusses why minority opinions remain inside as opposed to being relegated to the dustbin of history. This of course, is not unique. U.S. Supreme Court decisions contain dissenting views that are continually analyzed by legal scholars.

On the Talmud, Berkovitz concludes:��

“As our ancient rabbis understood, debate—and the people who engage in it—is vital to advancing society; it doesn’t degrade it. We gain nothing by turning debates on ideas into attacks on people. Both are part of the arc of the human story, but only one will elevate our community.”

How can one argue with that?!

And yet, the example of the Talmud fails to support Berkovitz’s claim. Jews, Christians, and Muslims may have entertained a variety of opinions on matters of great urgency. But not all. In fact, maybe not even most. They had their own “cancel culture.” It’s called heresy. Heresy constructed the limits of legitimate debate. In a sense heresy constructed Orthodoxy.

So who formulated heresy? That’s a complex historical question beyond the scope of this essay. But typically it was ecclesiastical authorities, or sometimes regional leadership. And what constituted heresy? Also beyond the limits here, but suffice it to say that these were largely theological or ideological determinations that extended beyond simple “errors” of belief, but required pertinacity, which is a willful or deliberate act of deviance, even after being warned.

In Christianity it often applied to the rejection of Church doctrine or dogma, while in Judaism it often consisted of either a rejection of rabbinic authority, or its construction of monotheism or claims of the divine origin of the Torah. One guilty of any of those “fallacies” was excluded from the debate; that is, they were canceled.

While the Talmud indeed includes multiple voices, it’s the product of a fairly small and exclusive fraternity of sages, each of whom passed the requisite initiation to be included. Of course, Babylonian Jewry was much more diverse than the included views would suggest. The Talmud doesn’t include those other voices, not necessarily because they thought they were heretics, but because they weren’t part of the club and thus their views had little if any authority. If all we had was the Babylonian Talmud we’d know very little about Babylonian Jewry in this period. All we’d have is the record of a thin slice of the society in a small number of academies.

Today, Talmudic scholars are exploring the wider vistas of the context of the Talmud, not only to show how it may have been influenced by its surroundings, but also in some cases to examine those the Talmud “cancelled”; those who engaged in magic bowl incantations, perhaps Zoroastrian fire worship, and other manner of religious practices that didn’t find favor in the sages of the Talmud. Were the sages being discriminatory by excluding these people and ejecting heretics from their midst?

One could say, and many have, that heresy is an old idea that’s no longer relevant. That modernity has thankfully moved us beyond heresy toward a more pluralistic world. French sociologist Emil Durkheim didn’t think so. Author of many works, including the influential The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912), Durkheim held that categories like heresy do translate into secular societies. In an essay “Concerning the Definition of Religious Phenomena,” Durkheim writes:

It is a fact that there are general beliefs of all kinds which appear to be relevant to secular objects, things like the flag, one’s country, some form of political organization, some hero, some historical event or other…They are obligatory in a certain sense, because of the very fact of their being in common…they are to some extent indistinguishable from religious beliefs proper.

Durkeim is talking about things common in a society but the same would apply if we diversify it to apply to venues, universities, churches, synagogues, and mosques, social communities, even Facebook threads. To take an example straight from Durkheim, a 2017 poll found that 60% of Americans believe that professional athletes should be required to stand during the playing of the national anthem. Groups are able to hold deep-seated convictions like this one, the rejection of which is a kind of secular heresy meaning they are excluded from their discourse. Protesting that norm is an act of “heresy” to counter a norm. If successful it can change the norm. But it can do so only by acting outside it.

This doesn’t deny that a group can hold a diversity of views on a particular issue, just as the Talmud records some of the views it ultimately rejects, but the Talmud in its diversity is also exercising cancellation (those outside the academy or those deemed to hold heretical views). Free speech enables us to say anything we want, but it doesn’t give us the right to say it anywhere we want. The Jewish heretic in late antique Babylonia could espouse any theological view he or she wanted, but if it didn’t find favor with the rabbis it wasn’t recorded in the Talmud. And thus, for all intents and purposes, it was cancelled.

Anything, but not anywhere

In light of the Harper’s Magazine letter, I find it curious that many now decrying cancel culture are the very beneficiaries of precisely that culture before it was named. That is, beneficiaries of all kinds of other people being excluded from the public sphere because of their religion, race, sexual orientation, or political views (communists, for example).

Thankfully our society is slowly rectifying those sins. But now to raise the issue of ideological discrimination as if to say, you cannot prevent me from saying that I want to say in your newspaper, or at your university, in your church, or even on your Facebook page, seems like protesting too much. That kind of freedom was never given, nor should it be foisted on, any community, publication, or platform.

In addition, the “cancel culture” police seem to be playing both sides of the wager. That is, they decry being “cancelled” but maintain their state of privilege and thus use their “cancellation” as proof they’re saying something important.

That’s because, ironically, the mere fact that they can say they’re being cancelled means, in part, that they’re not. They just take the position of privileged opposition and wear it as a badge of honor. If they were really cancelled, we wouldn’t hear their voices at all.

If you want to see real “cancel culture,” look at the myriad women, Black, gay, and other writers who lived their life in obscurity because they couldn’t get published and thus had no voice. For every Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, or Toni Morrison there are hundreds, maybe thousands, whose names we will never know.

In a free society, I may have to tolerate your views, but I’m under no obligation to publicize them, nor to let them pass without criticism. My right to criticize you publicly is no less important than your right to pontificate publicly. As Durkheim said, secular societies and subgroups, like religious ones, get to choose what is sacred and what is heretical. The former is included, the latter excluded. There may be no better example of that very limited diversity, and equally strong exercise of exclusion, than the Talmud.

Shaul Magid is a Professor of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College, Kogod Senior Research Fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America, and Contributing Editor to Tablet magazine. His forthcoming book Meir Kahane: An American Jewish Radical will be published by Princeton University Press.

This content was originally published here.

0 notes

Text

Ask the author: The people surrender nothing

The following is a series of questions prompted by the publication of Linda R. Monk’s “The Bill of Rights: A User’s Guide” (Hachette Book Group, 2018, 5th Ed.). In 1788, Alexander Hamilton argued in “Federalist 84” that a Bill of Rights was unnecessary in a democracy because “the people surrender nothing; and as they retain everything, they have no need of particular reservations.” Not everyone was so convinced, and – in what Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in her foreword, calls “one of the great compromises that helped assure passage of our founding document” – the states in 1791 ratified a “terse” Bill of Rights, the first 10 amendments to the Constitution.

This book – the fourth in a series of updates from the original version, which was written for the 1991 bicentennial of the Bill of Rights and which won the American Bar Association’s Silver Gavel Award for public education about the law – presents the history of these rights and their interpretations by the Supreme Court.

Monk’s other books are “The Words We Live By: Your Annotated Guide to the Constitution” and “Ordinary Americans: U.S. History Through the Eyes of Everyday People.”

* * *

Welcome, Linda, and thank you for taking the time to participate in this question-and-answer exchange for our readers.

Question: In her foreword, Justice Ginsburg writes that “the judiciary does not stand alone in guarding against governmental interference with fundamental rights,” which “is a charge we share with the Congress, the president, the states, and with the people themselves.”

I note that your subtitle is “A User’s Guide.” How are you hoping readers might use this book?

Monk: My goal was to make the principles I learned at Harvard Law School accessible to everyday citizens. But I’m pleased that many lawyers enjoy the book as well. As James Madison said, “Knowledge will forever govern ignorance, and a people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.” So knowledge comes first, but then comes practice. The stories of the citizens who stood up for constitutional principles — Fannie Lou Hamer, Mary Beth Tinker, Susette Kelo, Simon Tam — inspire me and I hope will inspire other citizens as well.

Question: You write that the Bill of Rights is “a living document” that “did not come with an instruction manual.” Can you elaborate on this idea?

Monk: I’m talking about the effect of the Bill of Rights on citizens, not on judges. As you know, the idea of a “living” Constitution is anathema to certain schools of jurisprudence, notably that of the late Justice Antonin Scalia. They believe this concept gives judges a blank check. But I quote Justice William O. Douglas who wrote in 1961, “[T]he reality of freedom in our daily lives is shown by the attitudes and policies of people toward each other in the very block or township where we live.” That’s the idea I want to emphasize, that our rights are enforced by our mutual respect as citizens.

Question: The first 10 amendments to the Constitution compose the Bill of Rights, and you devote a chapter to each amendment. You add one more chapter for the 14th Amendment.

What’s the relationship between this amendment and the Bill of Rights?

Monk: The 14th Amendment, which turns 150 years old this July, is really a second Bill of Rights, because it nationalizes the freedoms that previously only restricted the federal government. The Supreme Court used the 14th Amendment to apply the Bill of Rights bit by bit to state and local governments, which affect the most people. Before this process of “incorporation,” the Bill of Rights did not impact most Americans and few civil-liberties cases made it to the Supreme Court. In addition, the 14th Amendment for the first time introduced the principle of equality to the Constitution. “Equal protection of the laws” meant that government had to give legal justification when it treated citizens differently. And perhaps most important, the 14th Amendment defined citizenship for both the state and national governments, a process that previously had been left to the states.

Question: A lot has happened at the Supreme Court since the most recent version of this book came out in 2004. I note what must be new discussions of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (First Amendment, campaign finance), District of Columbia v. Heller (Second Amendment, individual right to bear arms), Glossip v. Gross (Eighth Amendment, methods of execution), and Obergefell v. Hodges (14th Amendment, same-sex marriage), among others.

Which amendment would you say has seen the most development and attention from the Supreme Court over the past 14 years? In what direction has the law developed?

Monk: During the past 14 years, there have been substantial developments in multiple areas, as you cite. Certainly, the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Second Amendment to fully adopt an individual right to bear arms is significant, although several prominent liberal scholars also embraced that approach. The real frontier is how this right can reasonably be limited, just as every other right in the Bill of Rights has limits. But I think the struggle of LGBTQ Americans for protection under the 14th Amendment is the most momentous change. However, neither LGBTQ persons nor women enjoy the “suspect class” status that requires “strict scrutiny” as in racial discrimination.

Question: Your chapter on the First Amendment is at least twice the size of your chapters on every other amendment. What makes this amendment so important?

Monk: I’d say it is the amendment Americans cherish most, although they might not be able to list all five freedoms it encompasses. It protects freedom of expression — including religion, speech, press, assembly and petition. There is a lot of history and a lot of litigation about those rights, and of course a lot of reader interest.

Question: In February, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in his dissent from the court’s denial of certiorari in Silvester v. Becerra that “the Second Amendment is a disfavored right.”

What do you think he means by this, and could you put his words into a larger context for our readers?

Monk: Far be it from me to put words in Justice Thomas’ mouth. But I gather from reading his dissent that he believes multiple lower courts, and the Supreme Court, are not treating limits on the Second Amendment as stringently as they would limits on, for example, First Amendment rights. Yet in the past century of litigation, the court has upheld time, place and manner restrictions; excluded libel, slander, active threats and pornography from free speech protection; and limited the scope of First Amendment rights in schools and prisons. The Second Amendment may just be catching up.

Question: You note that the Third Amendment “has never been the subject of a Supreme Court decision.” Can you remind us court-watchers what this amendment’s all about?

Monk: The Third Amendment prohibits the quartering of troops in homes during peacetime, and in wartime without lawful procedures. Although it is viewed as a relic of the Revolutionary War, the Third Amendment has been cited as support for an unenumerated right of privacy — along with the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth and 14th Amendments.

Question: You write that the Fifth Amendment is a “constitutional hodgepodge,” the “longest and most diverse amendment in the Bill of Rights.” Can you elaborate?

Monk: It’s the longest by sheer word count, and it embraces a broad range of rights under both civil and criminal law. Of course, the best known is the “right to remain silent” popularized on television. This right stems from the Star Chamber in England, which forced witnesses to swear to tell the truth (under an oath to God, with the ultimate penalty of eternal damnation) and then asked a wide range of questions about a variety of subjects. Eventually, someone would be found guilty of something, one way or the other. The Fifth Amendment also protects “due process of law,” perhaps the most fundamental type of justice under civil and criminal law. In addition, it ranges from the grand jury in criminal law to just compensation when private property is taken by the state. A very wide scope of rights.

Question: Why do you write that the Ninth Amendment “is one of the most controversial provisions in the Bill of Rights”?

Monk: My con-law professor John Hart Ely wrote that believing in the Ninth Amendment was like believing in ghosts (He was a utilitarian and not a fan of natural-rights theory.). Judge Robert Bork compared it to an ink blot. Randy Barnett of Georgetown Law sees it as a source of unenumerated rights, just as Article I’s necessary-and-proper clause is a source of unenumerated powers. Many Americans are concerned about unelected judges being given a blank check to create rights; for others, the Ninth Amendment is that blank check. For whatever reason, the courts have been more willing to protect unenumerated rights such as privacy and travel and marriage under the 14th Amendment, even though, as Justice Arthur Goldberg said, the Ninth may be more on point.

Question: The Supreme Court has yet to decide a number of cases this term involving the Bill of Rights, including Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (First Amendment, public-accommodations laws), Carpenter v. United States (Fourth Amendment, electronic privacy), and City of Hays, Kansas v. Vogt (Fifth Amendment, compelled statements).

What do you see as the biggest potential shifts in doctrine this year and into the near future?

Monk: I’m a better explicator than prognosticator, at least on the legal reasoning that should be part of any Supreme Court opinion. That’s what I focus on in my book: what the court said rather than what it might do. While I supported the outcome in Obergefell, on equal-protection grounds, I don’t understand the rationale for a liberty interest of persons “to define and express their identity.” I foresee that phrase engendering litigation. In Masterpiece, I have a personal interest because my mother made and decorated wedding cakes. And while I valued her creativity, I saw it as comparable to that of any artisan who provides a service — whether it is cake, furniture or fried chicken. And to me, fried chicken is definitely an art form.

Question: You write that for the constitutions of foreign nations, the “U.S. Bill of Rights serves as a reference point, if not always as a model.”

This question could be the subject of a whole book, but which amendments stand out as models and which as only “reference points,” and why?

Monk: The U.S. Bill of Rights applies to so-called “negative” rights rather than “positive” rights. So Americans are to be free from government restrictions on certain rights, but the Bill of Rights does not say the government must ensure positive rights — such as the right to health, education and a job. In other countries, such as South Africa, these positive rights are more prominent in their constitutions. But without a stable form of government can such rights truly be protected? The most important idea I learned in law school is “there is no right without a remedy.” That’s what makes the U.S. system unique: Our rights have legal remedies through the Constitution, which cannot be changed by majority rule.

The post Ask the author: The people surrender nothing appeared first on SCOTUSblog.

from Law http://www.scotusblog.com/2018/04/ask-the-author-the-people-surrender-nothing/

via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes

Text

It Stinks

Sunday Evening Thoughts

March 19, 2017

Dear Monica and Paul,

It Stinks

My heart is in anguish within me, the terrors of death have fallen upon me. Psalm 55:4

In traditional Christian theology, 39 of the 40 days of Lent (our current Liturgical Season) are about death. Only the last day of the season is about life — Easter. This was much more evident when I was a kid, as they covered all the statues in the churches, wore purple — or black on Good Friday, and played more somber music in my church. It was never the official teaching, but minimally thoughts of death equaled thoughts of life.

Vatican II changed that. (Vatican II was the famous Ecumenical Council called by Pope John XXIII to “open the windows of the church to let in the” cardinal birds… sorry, “Holy Spirit”, … bad joke.) The new theology of Vatican II emphasized not death, but life, and many of the symbols of death — or more precisely Italian drama — disappeared. You can decide if that’s a good thing or a bad thing.

I just finished Paul Kalanithi’s interesting autobiography about his life and death (his wife wrote the last chapter) titled When Air Becomes Breath. The topic of death itself is taboo in many cultures, at least that is my personal observation from time spent in Haiti. Paul Kalanithi though, like Pope John XXIII, opens the window and discusses his impending death in an honest and compelling story.

The first thing I noticed about Kalanithi is the tremendous amount of first-class education he obtained. Graduating at the top of his class in high school, he attended Stanford receiving his B.A. in Human Biology and a B.A. and M.A. in English, followed immediately by his M. Phil. in English Literature and Philosophy of History of Medicine from Cambridge. Only then did he realize that he really wanted to be a medical doctor not a doctor of philosophy in history or English, so off to Yale Medical School. Upon graduating, he decided to specialize in the most difficult and demanding area of medicine — neurosurgery. Thus, back to Stanford. Three-fourths of the way through medical school, he further committed to research in neuroscience and went to University of Wisconsin-Madison to get his PhD before finishing his residency in neurosurgery at Stanford.

And then it hit him, shortly after returning from Wisconsin, Stage IV metastatic non-small-cell EGRF lung cancer, which had metastasized into his brain.

Man, that stinks!

A new trial drug sounded promising, and appeared to be working great, which allowed him after a few months to return to his 12-plus daily hours of neurosurgery, and the tumors slowly regressed, until the very last scheduled cat scan showed a clear, though small new tumor. Bottom line he wasn’t cured. A week before graduating from Stanford Medical School with an offer from U. of Wisconsin to run their new billon dollar Neurology-Neurosurgery Center, he performed his last surgery at Stanford, and within weeks could no longer practice any medicine.

Man, that stinks!

Kalanithi then spends his remaining year-and-a-half writing this book, now on the N.Y. Times Non-fiction Best Sellers List for over a year.

His book though is about life, not death. Why live? He writes that all of his intentions were always principally about helping others, and not simply for himself. He writes that we should live each day, each moment, to the fullest.

No arguments here.

Kalanithi had distanced himself from organized religion, or even believing in God during most of his adult education, but he rediscovered his faith in the last years he lived. He thinks philosophically, much like I try to think, about God.

He writes,

Meanwhile his disciples urged him, “Rabbi, eat something.” But he said to them, “I have food to eat that you know nothing about.” Then his disciples said to each other, “Could someone have brought him food?”

It was passages like these, where there is a clear mocking of a literalist reading of Scriptures, that had brought me back to Christianity… During my sojourn in ironclad atheism, the primary arsenal against Christianity had been its failure on empirical grounds. Surely enlightened reason offered a more coherent cosmos. Surely Occam’s razor cut the faithful free of blind faith. There is no proof for God, therefore, it is unreasonable to believe [his italics] in God.

…The problem, however, eventually became evident to make science the arbiter of metaphysics is to banish not only God from the world but also love, hate, meaning—to consider a world that is self-evidently not [his italics] the world we live in…

It seems to me by his logic that if you believe in love then you must believe in God; or conversely, if you don’t believe in God, you cannot believe in love.

I will concede that if your definition of love is only a means for food, self-protection, and reproductive purposes, then one does not logically need to believe in God. But if you think there is any intrinsic value in love, then God must exist — at least that’s my thinking.

If I have a criticism of Kalanithi, it is that he does not realize the privileged life he has had. Or, to be fair, he does not disclose it in his book. Perhaps, he was aware, but was limited by time and space to write about it.

His father was an internal medicine professor at the University of Arizona Medical School. His mother, a first generation Indian-American, placed such a great emphasis on good education, that the small town in which they lived when he was in high school lacked A.P. courses, but she demanded that the high school offer A.P. courses, and even became a member of the school board to raise the standards for all students in their town. Even his brother is a successful neurosurgeon. And his wife, a Yale Medical School Graduate, is on the faculty in Internal Medicine at Stanford Medical School.

So let’s just assume that whenever a test result came in, there was never any doubt as to its meaning, or how to navigate the medical system to get the right test. Further, financially, can we assume money is going to be no object for him while he is sick? Or, his wife and child will never go hungry afterward?

I don’t fault him for being bright or wealthy. And I don’t mean to imply he had no concern for the less intelligent or less fortunate. I don’t know. But most people do not have his intelligence or his wealth, so when they navigate the medical system with cancer, treatment, and drugs, they are not as fortuitous. How often do people decide between buying medicine for their cancer or bread for their children?

Still, Paul Kalanithi makes you think not just about death, but also about life and meaning.

… have a good week.

Love,

Dad

P.S. I leave you with “Joy” by Phish. Trey and Tom Marshall co-wrote “Joy.” (Marshall is credited with writing over 95 original Phish songs, though he does not perform with them.) Trey’s sister was going through cancer in 2009, so he (and Marshall) wrote it as a pick-me-up. This is the first time Phish played it live. A slightly better version on YouTube is in North Charleston.

Enjoy. Crank it up!

youtube

0 notes