#John Grunsfeld

Text

STS-400: The planned (if needed) rescue of STS-125

Unofficial crew patch *

On LC-39A STS-125 Atlantis (left) and on LC-39B is STS-400 Endeavour (right).

In the wake of the Columbia Tragedy, NASA prepared several contingency missions in the event a shuttle could not return safely. Most of the shuttle missions post STS-107, involved the construction/support of the International Space Station. If there were any instances where the shuttle was deemed unfit to return safely, the crew would stay on the ISS until a relief shuttle could be sent. However, STS-125 Atlantis was to service the Hubble Space Telescope and was not on the same orbital plane as the ISS. The Atlantis wouldn't have enough fuel to reach the station, so another Shuttle (Endeavour) was kept on standby on LC-39B. STS-400 would have been crewed by Christopher Ferguson, Eric A. Boe, Robert S. Kimbrough and Stephen G. Bowen.

On the first day, the crew of Atlantis would use the Canadarm to inspect the bottom of the shuttle for damage to the Thermal Protection System. Had there been any damage deemed unrepairable, the plan was to launch Endeavour 5 days later. Atlantis would be put into powered-down mode to conserve power and consumables.

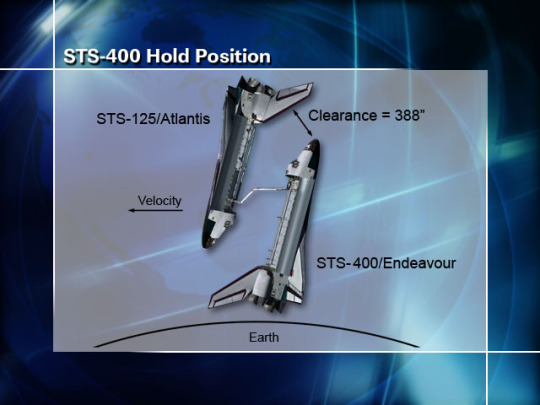

Endeavour will have Altitude Control with Atlantis serving as a Micro-Meteoroid Orbiting Debris shield.

"On flight day two, Endeavour would have performed the rendezvous and grapple with Atlantis."

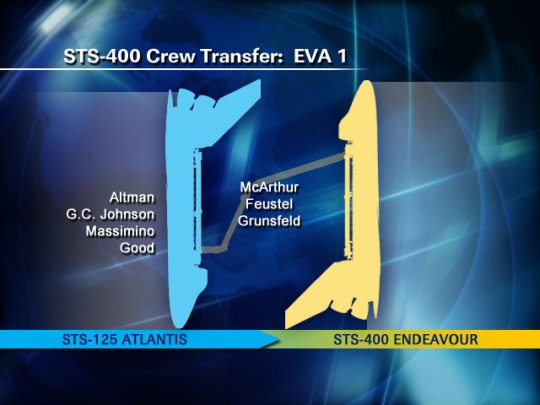

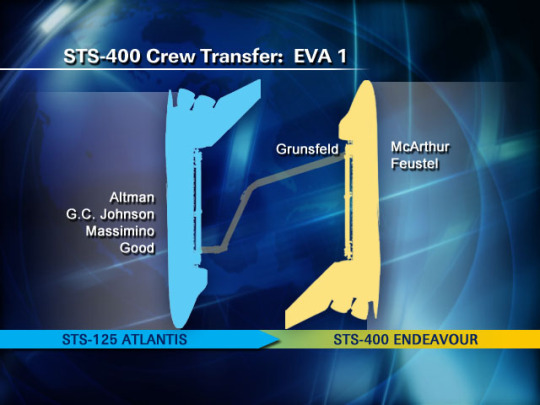

Crew locations during EVA-1

"On flight day three, the first EVA would have been performed. During the first EVA, Megan McArthur, Andrew Feustel and John Grunsfeld would have set up a tether between the airlocks. They would have also transferred a large size Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) and, after McArthur had repressurized, transferred McArthur's EMU back to Atlantis. Afterwards they would have repressurized on Endeavour, ending flight day two activities."

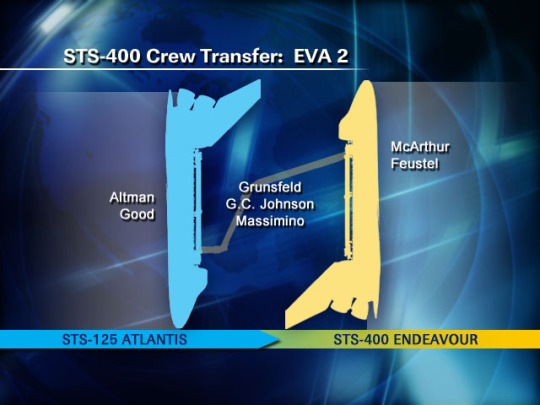

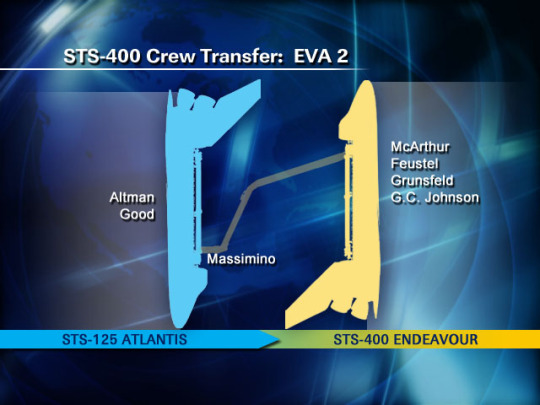

Crew locations during EVA-2

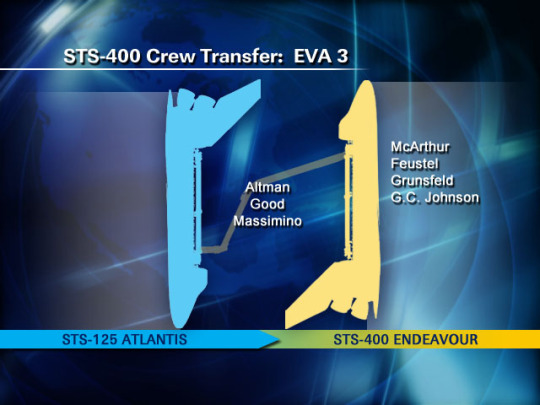

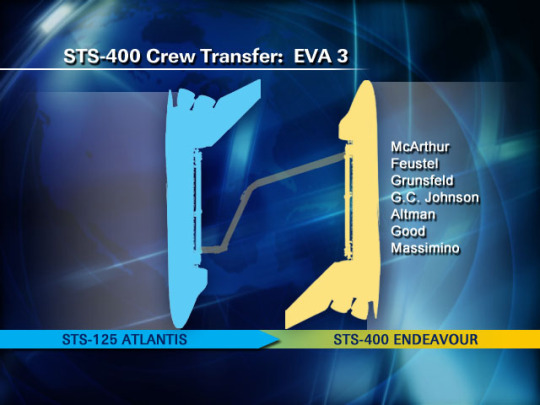

Crew locations during EVA-3

"The final two EVA were planned for flight day three. During the first, Grunsfeld would have depressurized on Endeavour in order to assist Gregory Johnson and Michael Massimino in transferring an EMU to Atlantis. He and Johnson would then repressurize on Endeavour, and Massimino would have gone back to Atlantis. He, along with Scott Altman and Michael Good would have taken the rest of the equipment and themselves to Endeavour during the final EVA. They would have been standing by in case the RMS system should malfunction. The damaged orbiter would have been commanded by the ground to deorbit and go through landing procedures over the Pacific, with the impact area being north of Hawaii. On flight day five, Endeavour would have had a full heat shield inspection, and land on flight day eight."

Information from Wikipedia link

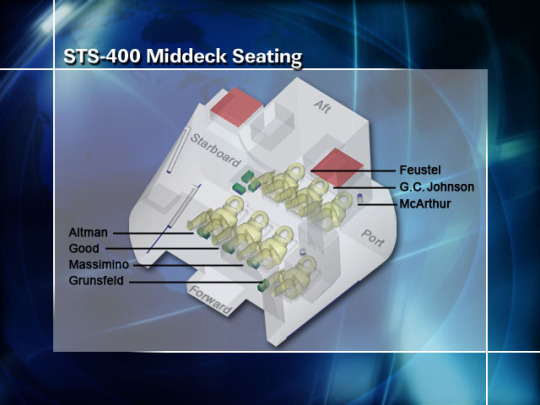

STS-400 Middeck Seating

The additional crew members on Endeavour would have been accommodated via additional seats installed on the middeck. The autopilot onboard Atlantis would be used to de-orbit the orbiter tail first, to destroy it over a region north of Hawaii, in the Pacific Ocean.

Another unofficial crew patch.

View from LC-39B of the launch of STS-125 Atlantis on May 11, 2009. This was the fifth and final Space Shuttle mission to the Hubble Space Telescope.

Fortunately, STS-400 was not needed and Endeavour was returned to the VAB from LC-39B for STS-127.

* "As a contingency mission, STS-400 was not given official support by NASA for the production of a crew patch or emblem. However this artwork was created for use by the mission team as an unofficial emblem by Mike Okuda [the same person who worked on Star Trek and most of the LCARS], who also illustrated the official patch of STS-125, the flight to be rescued by STS-400."

Date: September 9, 2008

source, source, source, source, source, source, source, source, source, source, source, source, source , source

#STS-400#STS-125#Space Shuttle Atlantis#Atlantis#OV-104#Space Shuttle#Space Shuttle Endeavour#Endeavour#OV-105#Orbiter#NASA#Space Shuttle Program#September#2008#rescue#my post

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

NASA astronaut John Grunsfeld on service mission to Hubble, Space Shuttle Columbia, STS-109, March 2002.

0 notes

Photo

CHRISTMAS EVE IN SPACE – Astronaut John Grunsfeld makes repairs to the Hubble Space Telescope, December 24-25, 1999.

#space#science#christmas#christmas eve#spacewalk#john grunsfeld#hubble space telescope#astronomy#december 24#december 25#1999#1990s

86 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Christmas in Space: Day 5

In 1999, STS-103 became the first and only shuttle crew to spend Christmas in space. Americans Curt Brown, Scott Kelly, John Grunsfeld, Steve Smith, British-born NASA astronaut Michael Foale, Frenchman Jean-Francois Clervoy, and Claude Nicollier, Switzerland’s first astronaut, were in orbit from December 19th to December 27th on a mission to service the Hubble Space Telescope.

On Christmas morning, the crew was awakened by Bing Crosby’s “I’ll Be Home for Christmas,” to which Commander Brown replied, “Merry Christmas to y’all down there. And Hubble will be home for Christmas, 'cause today we're going to set her free!” At 5:03 p.m., Hubble was released back into orbit.

#sorry this is so late I've been busy ALL day#I have a presentation on my NASA paper tomorrow send good wishes 😩😩#christmas in space#STS-103#hubble#astronauts#NASA#1990s#holidays#gifs#*#curt brown#scott kelly#john grunsfeld#steve smith#michael foale#jean-francois clervoy#claude nicollier

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NASA Astronaut Steven L. Smith and NASA Astronaut John M. Grunsfeld "appear as small figures in this wide scene photographed during" a space walk in Dec 1999. They "are replacing gyroscopes" in the Hubble Space Telescope. The photo was taken from NASA's Space Shuttle Discovery (STS-103). [2046x2030] via /r/spaceporn https://ift.tt/2QaPc21

1 note

·

View note

Text

WHAT IS THE BUBBLE NEBULA??

Blog#61 Wednesday, February 10th ,2021

Welcome back,

In 2016, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope captured a stunning image of perhaps one of the most intriguing objects in our Milky Way galaxy: a massive star trapped inside a bubble. Object NGC 7635, better known as the Bubble Nebula, is located about 7,100 light-years away in the Cassiopeia constellation.

Its star burns a million times brighter than our sun and produces powerful gaseous outflows called stellar winds that howl at more than four million miles per hour. Over time, the winds have pushed nearby gas and dust outward, forming a layer around the star that’s denser in some areas than others. Based on the rate the star is expending energy, scientists estimate in 10 to 20 million years it will explode as a supernova. And the bubble will succumb to a common fate: It’ll pop.

About This Image^^

For the 26th birthday of NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers are highlighting a Hubble image of an enormous bubble being blown into space by a super-hot, massive star. The Hubble image of the Bubble Nebula, or NGC 7635, was chosen to mark the 26th anniversary of the launch of Hubble into Earth orbit by the STS-31 space shuttle crew on April 24, 1990.

"As Hubble makes its 26th revolution around our home star, the sun, we celebrate the event with a spectacular image of a dynamic and exciting interaction of a young star with its environment. The view of the Bubble Nebula, crafted from Wide Field Camera 3 images, reminds us that Hubble gives us a front-row seat to the awe-inspiring universe we live in," said John Grunsfeld, astronaut and associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters, in Washington, D.C.

The Bubble Nebula is 7 light-years across – about one-and-a-half times the distance from our sun to its nearest stellar neighbor, Alpha Centauri – and resides 7,100 light-years from Earth in the constellation Cassiopeia.

The seething star forming this nebula is 45 times more massive than our sun. Gas on the star gets so hot that it escapes away into space as a "stellar wind" moving at over 4 million miles per hour. This outflow sweeps up the cold, interstellar gas in front of it, forming the outer edge of the bubble much like a snowplow piles up snow in front of it as it moves forward.

As the surface of the bubble's shell expands outward, it slams into dense regions of cold gas on one side of the bubble. This asymmetry makes the star appear dramatically off-center from the bubble, with its location in the 10 o'clock position in the Hubble view. Dense pillars of cool hydrogen gas laced with dust appear at the upper left of the picture, and more "fingers" can be seen nearly face-on, behind the translucent bubble.

The gases heated to varying temperatures emit different colors: oxygen is hot enough to emit blue light in the bubble near the star, while the cooler pillars are yellow from the combined light of hydrogen and nitrogen. The pillars are similar to the iconic columns in the "Pillars of Creation" in the Eagle Nebula. As seen with the structures in the Eagle Nebula, the Bubble Nebula pillars are being illuminated by the strong ultraviolet radiation from the brilliant star inside the bubble.

The Bubble Nebula was discovered in 1787 by William Herschel, a prominent British astronomer. It is being formed by an O star, BD +60°2522, an extremely bright, massive, and short-lived star that has lost most of its outer hydrogen and is now fusing helium into heavier elements. The star is about 4 million years old, and in 10 million to 20 million years, it will likely detonate as a supernova.

Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 imaged the nebula in visible light with unprecedented clarity in February 2016. The colors correspond to blue for oxygen, green for hydrogen, and red for nitrogen. This information will help astronomers understand the geometry and dynamics of this complex system.

The Bubble Nebula is one of only a handful of astronomical objects that have been observed with several different instruments onboard Hubble. Hubble also imaged it with the Wide Field Planetary Camera (WFPC) in September of 1992, and with Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) in April of 1999.

COMING UP!!

(Saturday, February 13th ,2021)

“NEARBY ANCIENT DWARF GALAXIES HAVE A SURPRISING AMOUNT OF DARK MATTER??”

#Astronomy#astrophysics#astrophotography#string theory#universe#alternate universe#Parallel Universe#white universe#outer space#spacecraft#atmosphere#Sunspot#sunny#sunspots#The Sun#the flash#nebula#bubble nebula

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Flag of Mars

from /r/vexillology

Top comment: Pascal Lee, a former NASA research engineer designed this Mars flag in 1999. It was flown into space on STS-103 by astronaut John M. Grunsfeld. The sequence of colors, from red, to green, and finally blue, represent the transformation of Mars from a lifeless planet to one teeming with life, as inspired by Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars trilogy of novels. It is also flown at the Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station, on behalf of the Mars Society.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NASA astronauts Steven Smith & John Grunsfeld servicing the Hubble Space Telescope, December 1999 [2046x2030]

129 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NASA astronauts Steven Smith & John Grunsfeld servicing the Hubble Space Telescope, December 1999 [2046x2030]

104 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NASA astronauts Steven Smith & John Grunsfeld servicing the Hubble Space Telescope, December 1999.

See more on my twitter page

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Space Station 20th: Spacewalking History

ISS - 20 Years on the International Space Station patch.

June 4, 2020

Assembly of the International Space Station (ISS) would not have been possible without the skilled work of dozens of astronauts and cosmonauts performing intricate tasks in bulky spacesuits in the harsh environment of space. Spacewalks, or extravehicular activities (EVAs), were indispensable to the assembly of ISS and today remain important to the continued maintenance of the world class laboratory in low Earth orbit.

Above: Leonov during the world’s first EVA in March 1965.

Bellow: White during the first American EVA in June 1965.

On June 3, 1965, astronaut Edward H. White opened the hatch to the Gemini 4 capsule and, as he floated out of the cabin, became the first American to walk in space. A few weeks earlier, on March 18, Soviet cosmonaut Aleksei A. Leonov took the world’s first spacewalk as he floated out of an airlock attached to his Voskhod 2 spacecraft. Although White’s 36-minute EVA appeared effortless, later spacewalkers in the Gemini Program found accomplishing actual work quite challenging. Because NASA considered mastering spacewalking a critical task for the Apollo Moon landing program, astronauts and engineers expended much effort to learn the required skills, and by the final flight of the Gemini program astronaut Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin proved that EVAs could be productive. His training in an underwater environment to simulate spacewalking proved to be a game-changer and the practice has been standard ever since.

Above: Apollo 17 astronaut Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt during an EVA on the lunar surface in 1972.

Middle: Skylab 4 astronaut Edward G. Gibson during the final EVA of the Skylab Program in 1974.

Bellow: Soviet cosmonaut Georgi M. Grechko preparing for the first EVA aboard the Salyut-6 space station in 1977.

Most spacewalks during the Apollo Program took place on the lunar surface and extended EVA durations past seven hours through upgrades to the spacesuits or Extravehicular Mobility Units (EMUs). Spacewalks conducted aboard Skylab in the mid-1970s proved the value of spacesuited astronauts to carry out repairs and maintenance of the space station – indeed, the EVA to free Skylab’s jammed solar array played a key role in saving the program. Similarly, beginning in the late 1970s, Soviet then Russian cosmonauts using ever-improved Orlan spacesuits proved the value of EVAs in inspecting, maintaining, repairing and augmenting space stations.

Above: STS-6 astronauts F. Story Musgrave (left) and Donald H. Peterson during the first Shuttle

EVA in 1983. Middle: Mir 20 crewmembers Sergei V. Avdeyev (left) and European Space Agency

astronaut Thomas A. Reiter in 1995. Bellow: STS-125 astronauts John M. Grunsfeld and Andrew J. Feustel preparing to reenter the Shuttle’s airlock after the final Hubble servicing EVA in 2009.

Spacewalks during the Space Shuttle era demonstrated that astronauts during EVAs could capture, repair and redeploy satellites, test future refueling of spacecraft and evaluate assembly techniques. From the first EVA during STS-6 in 1983 to the last non-space station related Shuttle EVA during STS-125, the final Hubble Servicing Mission in 2009, astronauts completed 52 spacewalks, 23 of them dedicated to servicing the Hubble Space Telescope in the course of five missions. Cosmonauts aboard the Mir space station made extensive use of EVAs for construction, maintenance and scientific and technology research during 79 spacewalks over the facility’s 15-year orbital lifetime. Mir also hosted the first EVA by a non-Russian crewmember, Jean-Loup Chrétien from France in 1988.

Above: Linenger during his EVA with Tsibliev outside Mir.

Bellow: Parazynski (left) and Titov during the STS-86 EVA at Mir.

One of the stated objectives of the Shuttle-Mir Program, also known as Phase 1 of ISS, was for the United States and Russia to learn to work together as the two former adversaries prepared to jointly build and operate the space station. One arena where this was clearly demonstrated was in spacewalking. As Phase 1 progressed, astronauts living and working aboard Mir became more involved in the station’s operations, including conducting EVAs. On April 29, 1997, Jerry M. Linenger became the first American astronaut to perform an EVA in a Russian Orlan spacesuit with his Mir 23 commander Vasili V. Tsibliev. C. Michael Foale and David A. Wolfe added to that experience base with their Mir Orlan EVAs later that year. Foale became the first person to perform EVAs in both the US EMU and the Russian Orlan spacesuits. On Oct. 1, 1997, Scott E. Parazynski and Vladimir G. Titov performed the first joint US-Russian EMU EVA during STS-86 while Space Shuttle Atlantis was docked to Mir. Titov was also the first non-American to conduct a Shuttle-based EVA.

Graphic representation of the number of ISS EVAs over the past 22 years.

The complex assembly of ISS would have been impossible without the skilled labors of spacewalking astronauts and cosmonauts. The cumulative experience of the EVAs conducted in the years prior to the start of ISS assembly formed a solid basis on which to build the necessary spacewalking skills. It is of interest to note that 23 years passed between Leonov’s first daring venture into open space and the first EVA at ISS, during which time 171 spacewalks were completed in low Earth orbit, on the Moon and in deep space. In the 22 years since the first ISS assembly EVA, 227 spacewalks dedicated to ISS have been accomplished plus an additional 13 during Space Shuttle missions unrelated to ISS, 4 on the Russian Mir space station and 1 by the People’s Republic of China.

Above: STS-88 astronauts Newman (left) and Ross perform the very first EVA at ISS in 1988.

Middle: STS-96 astronaut Jernigan moving the Strela Grapple Fixture adaptor. Bellow: STS-106

crewmembers Malenchenko (left) and Lu connect cables between Zarya and Zvezda during the

first joint US-Russian EVA on ISS.

From the very first assembly mission, spacewalks proved to be essential to preparing the fledgling ISS for its first occupants. Astronauts Jerry L. Ross and James H. Newman conducted the first ISS EVA on Dec. 7, 1988, during the STS-88 mission to connect electrical and data cables between the station’s first two modules, Zarya and Unity. Over the course of the first five Shuttle assembly missions, 12 crewmembers conducted 10 EVAs prior to the Expedition 1 crew taking up residency aboard the station. During STS-96, the second assembly mission in May 1999, Tamara E. “Tammy” Jernigan became the first of many women to perform an EVA at ISS. Astronaut Edward T. “Ed” Lu and cosmonaut Yuri I. Malenchenko conducted the first US-Russian EVA at ISS during the June 2000 STS-101 mission. The two connected electrical and data cables between Zarya and the newly-arrived Zvezda module. Training for that spacewalk required Russian engineers to modify the Hydrolab facility at the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center to accommodate the US EMUs. Similarly, American engineers adapted the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory at Johnson Space Center to allow the Expedition 1 crew to train using both the EMU and the Russian Orlan spacesuit.

Above: Expedition 2 astronaut Helms during the longest EVA to date. Middle: STS-100 astronaut

Hadfield, the first Canadian to perform an EVA at ISS. Bellow: Expedition 2 crewmembers Voss (left) and Usachev in the hatchway to Zvezda’s Transfer Compartment preparing for the first Russian Segment EVA.

Following the arrival of Expedition 1 crewmembers William M. Shepherd, Yuri P. Gidzenko and Sergei K. Krikalev aboard ISS on Nov. 2, 2000, the pace of assembly and the number of spacewalks increased significantly. Between December 2000 and April 2003, 38 astronauts and cosmonauts completed 41 EVAs, including the first staged from ISS itself rather than from the Space Shuttle. On March 10, 2001, Expedition 2 astronauts James S. Voss and Susan J. Helms conducted a spacewalk during STS-102 that at 8 hours and 56 minutes still stands as the longest EVA in history. In April 2001, Canadian Space Agency astronaut Chris A. Hadfield became the first Canadian to conduct an EVA at ISS during STS-100, the flight that brought the Canadarm2 robotics system to the space station. On June 8, Voss joined Expedition 2 cosmonaut Yuri V. Usachev for the first Russian segment EVA, an internal spacewalk in Zvezda’s Transfer Compartment to prepare it for the arrival of a new module.

Above: STS-104 astronauts Gernhardt emerging to begin the first EVA from the ISS Quest

Joint Airlock. Middle: Expedition 3 cosmonauts Dezhurov (left) and Tyurin about to begin the

first EVA from the Pirs module. Bellow: STS-111 crewmember Perrin, the first French astronaut

to perform an EVA at ISS.

The STS-104 mission in July 2001 brought the Quest Joint Airlock to the station, providing ISS with a standalone EVA capability, with accommodations for both the US EMU and the Russian Orlan suits. Michael L. Gernhardt and James F. Reilly performed the first EVA from Quest on July 20. The Pirs module arrived at ISS on Sept. 17, providing the Russian segment with a true airlock capability. On Oct. 8, Expedition 3 cosmonauts Vladimir N. Dezhurov and Mikhail V. Tyurin staged the first EVA from Pirs. Along with American and Russian crewmembers, international partners continued to play a role in spacewalking, with Philippe Perrin becoming the first astronaut from France to perform an EVA at ISS during the STS-111 mission in June 2002.

Above: Expedition 8 Commander Foale preparing for the first “two-person” EVA.

Middle: STS-114 astronaut Noguchi performing the first EVA for JAXA at ISS.

Bellow: Expedition 13 astronaut Reiter conducting the first EVA by an ESA crewmember at ISS.

Following the Space Shuttle Columbia accident, ISS EVAs continued but only from the Russian segment with the added complication that with the resident crew size reduced to two, the pair of spacewalking crewmembers left no one inside the station to monitor its systems. Although this posed a slightly increased risk should something go wrong, these “two-person” EVAs proved essential during the Shuttle hiatus. Expedition 8 crewmembers Aleksandr Y. Kaleri and Mike Foale conducted the first such EVA on Feb. 26, 2004. Foale had prior experience with the Orlan suit as he had completed an EVA during his long-duration stay aboard Mir in 1997. The crew had to cut the EVA short due to Kaleri’s suit overheating and water droplets forming inside his helmet. The crew later identified the problem as a kink in the water line in his liquid cooling garment. The incident provided a preview of a more serious problem to occur in an EMU during an EVA more than nine years later. On the STS-114 Shuttle Return-to-Flight mission, Soichi Noguchi became the first astronaut from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency to conduct an EVA at ISS on July 30, 2005. The first European Space Agency astronaut to perform an ISS spacewalk was Expedition 13 crewmember Thomas A. Reiter from Germany, on Aug. 3, 2006.

Above: Closeup of the tear in the solar array. Middle: STS-120 astronaut Parazynski atop the robotic

arm and boom near the site of the tear. Bellow: Parazynski approaches the tear to effect the repair.

Although all spacewalks carry a certain amount of risk, two examples illustrate how some EVAs are riskier than others. The objectives of the STS-120 mission in October 2007 included not only delivery of the Harmony module to ISS but also the relocation of the P6 truss segment from its location atop the Z1 truss, where it had been since December 2000, to the outboard port side truss. During the overall reconfiguration of the station’s power systems earlier in 2007, the P6’s solar arrays were rolled up. After the crewmembers relocated P6 to the outboard truss, they began to unfurl the two arrays. The first array opened without incident, but with the second array nearly unfurled the astronauts noticed a tear in a small portion of the panel and immediately halted the deployment to prevent damaging it. Working with the onboard crew, mission managers devised a plan to have one of the astronauts essentially suture the tear in the panel. Appropriately enough, one of the two STS-120 spacewalkers, Scott E. Parazynski, was also a physician and he put his suturing skills to good use. Attached to a portable foot restraint, Parazynski was hoisted atop not only the station’s robotic arm but also the Shuttle’s boom normally used to inspect the Orbiter’s tiles, the impromptu arrangement providing just enough reach for Parazynski to successfully repair the torn array using a newly-designed tool dubbed “cufflinks.” After he secured five cufflinks to the damaged panel, crewmembers inside the station fully extended the array as Parazynski monitored the event.

Above: Expedition 36 astronaut Parmitano during EVA23. Bellow: Expedition 36

crewmembers Nyberg (left) and Yurchikhin assist Parmitano with removing

his EMU after his safe return to the airlock.

Luca S. Parmitano, the first astronaut representing the Italian Space Agency to conduct an EVA at ISS, and his fellow Expedition 36 crewmember Christopher J. Cassidy began US EVA23, their second EVA together, on July 16, 2013, without incident. Forty-four minutes into the EVA, as the two crewmembers worked on their individual tasks at different locations on ISS, Parmitano reported feeling water at the back of his head. Mission Control advised them to halt their activities as they devised a plan of action. Cassidy came to Parmitano’s side to assess the situation, at first believing that a leaking drink bag inside the suit was the source of the water. But as Parmitano indicated that the amount of water was increasing, Mission Control advised them to terminate the EVA, directing Parmitano to head back to the airlock and Cassidy to clean up any tools and then follow his crewmate back to the airlock. As Parmitano began translating back toward the airlock, the water continued to increase, migrating from the back of his head, filling his ears so he had difficulty hearing communications and eventually obscuring his vision and interfering with breathing. He made his way back to the airlock mostly by memory and feel, and after Cassidy joined him inside they repressurized the module. Expedition 36 crewmates Karen L. Nyberg and Fyodor N. Yurchikhin helped Parmitano quickly remove his helmet and towel off the estimated 1 to 1.5 liters of water. Later investigation indicated that contamination on a filter caused blockage in the suit’s water separator. Although Parmitano faced a potentially life-threatening situation, his calm response along with quick decisions by the team in Mission Control resolved the crisis successfully. He later joked during an in-flight press conference that he “experience what it was like to be a goldfish in a fishbowl from the point of view of the goldfish.”

Above: Preparing for the first all-woman EVA are Expedition 61 astronauts Meir (left)

and Koch. Bellow: The latest EVA on ISS in January 2020, performed by Expedition 61

astronauts Morgan (left) and Parmitano.

The Expedition 61 crew completed a record nine EVAs between Oct. 6, 2019, and Jan. 25, 2020. Five involved tasks to replace batteries on the P6 truss segment and three to repair the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS), a physics experiment not originally designed for on-orbit repairs. Of note, Christina Koch and Jessica U. Meir conducted the third battery-replacement EVA on Oct. 18, the first time all-female spacewalk in history. The pair completed two more EVAs in January 2020. Their fellow crewmembers, Andrew J. “Drew” Morgan and Luca Parmitano, completed the most recent EVA to date, the final spacewalk to repair AMS.

Related articles:

Space Station 20th: Commercial Cargo and Crew

https://orbiterchspacenews.blogspot.com/2020/06/space-station-20th-commercial-cargo-and.html

Space Station 20th: Music on ISS

https://orbiterchspacenews.blogspot.com/2020/05/space-station-20th-music-on-iss.html

Space Station 20th – Space Flight Participants

https://orbiterchspacenews.blogspot.com/2020/05/space-station-20th-space-flight.html

Space Station 20th: Six Months Until Expedition 1

https://orbiterchspacenews.blogspot.com/2020/04/space-station-20th-six-months-until.html

Space Station 20th – Women and the Space Station

https://orbiterchspacenews.blogspot.com/2020/03/space-station-20th-women-and-space.html

Space Station 20th: Long-duration Missions

https://orbiterchspacenews.blogspot.com/2020/03/space-station-20th-long-duration.html

NASA Counts Down to Twenty Years of Continuous Human Presence on International Space Station

https://orbiterchspacenews.blogspot.com/2019/11/nasa-counts-down-to-twenty-years-of.html

20 memorable moments from the International Space Station

https://orbiterchspacenews.blogspot.com/2018/11/20-memorable-moments-from-international.html

Related links:

International Space Station (ISS): https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/main/index.html

Images, Text, Credits: NASA/Kelli Mars/JSC/John Uri/ESA/JAXA/CSA-ASC/ROSCOSMOS.

Greetings, Orbiter.ch

Full article

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Space Shuttle Columbia begins its 27th flight in the pre-dawn hours from Launch Pad 39A. Liftoff for STS-109 occurred at 6:22:02:08 a.m., EST (11:22:02:08 GMT) on March 1, 2002. The goal of the mission is the maintenance and upgrade of the Hubble Space Telescope, to be carried out in five space walks. On board the spacecraft were astronauts Scott D. Altman, Duane G. Carey, Nancy J. Currie, John M. Grunsfeld, James H. Newman, Richard M. Linnehan, and Michael J. Massimino."

Date: March 1, 2002

NASA ID: STS109-S-005

#STS-109#Space Shuttle#Space Shuttle Columbia#Columbia#OV-102#Orbiter#NASA#Space Shuttle Program#Launch#LC-39A#Kennedy Space Center#KSC#Florida#March#2001#my post

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I was not really scared on my spacewalks. We practice so much and need to stay so focused that it has a calming effect on me. I do a kind of visualization and meditation in the airlock prior to going outside, to guide my first activities once I get out in space.

John M. Grunsfeld

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

May 14, 2009 – Spacewalker John Grunsfeld works on the Hubble Space Telescope while the orbital observatory is anchored to the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle Atlantis.

(NASA)

#space#science#spacewalk#astronomy#hubble#hubble space telescope#may 14#john grunsfeld#astronaut#space shuttle#space shuttle atlantis

204 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I believe that the future of humans, and the future of Earth, depends on space exploration. That’s not a French problem, or a problem for Alabama: it’s a planet-wide problem. International cooperation is crucial.

John M. Grunsfeld, American Astronaut

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NASA astronauts Steven Smith & John Grunsfeld servicing the Hubble Space Telescope, December 1999 [2046x2030] via /r/spaceporn https://ift.tt/2wADDvr

0 notes