#Lord Widgery Report

Text

#OTD in Irish History | 19 April:

1366 – The parliament, alarmed at the apparent undermining by native influences of the settler population’s Englishness, passed the ‘Statutes of Kilkenny’.

1608 – O’Doherty’s Rebellion was launched by the Burning of Derry.

1780 – Henry Grattan moves resolutions in favour of legislative independence in the Irish House of Commons.

1798 – The Earl of Clare began a 3-day visit to Trinity College,…

View On WordPress

#irelandinspires#irishhistory#OTD#1798 United Irishmen Rebellion#19 April#Bloody Sunday#Co. Kerry#Coumeenole Beach#Dunquin#History#History of Ireland#Ireland#Irish Civil War#Irish History#Lord Widgery Report#Photo credit: Michael Corcoran#Statute of Kilkenny#Today in Irish History

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

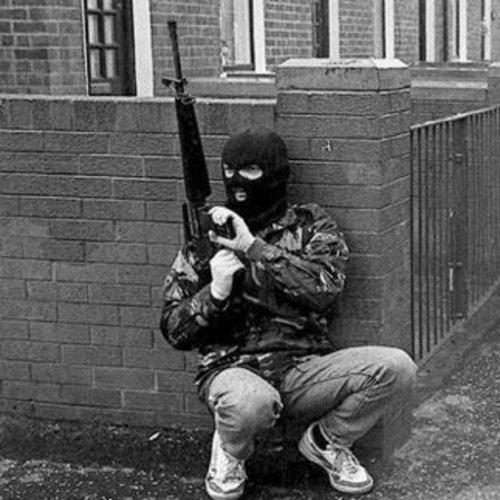

30 January 1972: Bogside Massacre, or the Bloody Sunday

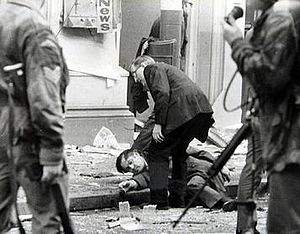

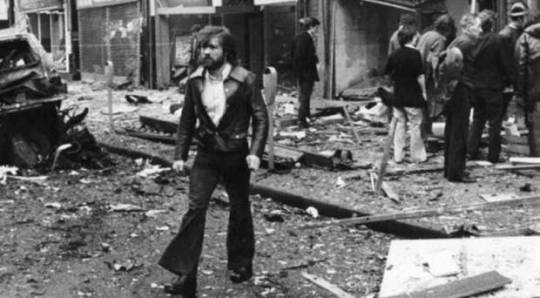

Bogside Massacre, or the Bloody Sunday, was a massacre on 30 January 1972 in the Bogside area of Derry, Northern Ireland, when British soldiers shot 26 civilians during a protest march against internment without trial. Fourteen people died: 13 were killed outright, while the death of another man four months later was attributed to his injuries. Many of the victims were shot while fleeing from the soldiers, and some were shot while trying to help the wounded. Other protesters were injured by shrapnel, rubber bullets, or batons, and two were run down by army vehicles. All of those shot were Catholics. The march had been organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA). The soldiers were from the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment (“1 Para”), the same regiment implicated in the Ballymurphy massacre several months prior.

Two investigations were held by the British government. The Widgery Tribunal, held in the immediate aftermath, largely cleared the soldiers and British authorities of blame. It described the soldiers’ shooting as “bordering on the reckless”, but accepted their claims that they shot at gunmen and bomb-throwers. The report was widely criticised as a “whitewash”. The Saville Inquiry, chaired by Lord Saville of Newdigate, was established in 1998 to reinvestigate the incident. Following a 12-year investigation, Saville’s report was made public in 2010 and concluded that the killings were both “unjustified” and “unjustifiable”. It found that all of those shot were unarmed, that none were posing a serious threat, that no bombs were thrown and that soldiers “knowingly put forward false accounts” to justify their firing. The soldiers denied shooting the named victims but also denied shooting anyone by mistake. On publication of the report, the British prime minister David Cameron made a formal apology on behalf of the United Kingdom. Following this, police began a murder investigation into the killings.

Bloody Sunday came to be regarded as one of the most significant events of the Troubles, because many civilians were killed by forces of the state, in full view of the public and the press. It was the highest number of people killed in a single shooting incident during the conflict and is considered the worst mass shooting in Northern Irish history. Bloody Sunday fuelled Catholic and Irish nationalist hostility towards the British Army and worsened the conflict. Support for the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) rose, and there was a surge of recruitment into the organisation, especially locally.

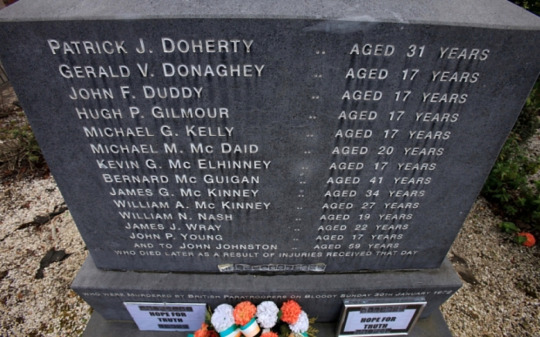

In all, 26 people were shot by the paratroopers; 13 died on the day and another died of his injuries four months later. The dead were killed in four main areas: the rubble barricade across Rossville Street, the courtyard car park of Rossville Flats (on the north side of the flats), the courtyard car park of Glenfada Park, and the forecourt of Rossville Flats (on the south side of the flats).

All of the soldiers responsible insisted that they had shot at, and hit, gunmen or bomb-throwers. No soldier said he missed his target and hit someone else by mistake. The Saville Report concluded that all of those shot were unarmed and that none were posing a serious threat. It also concluded that none of the soldiers fired in response to attacks, or threatened attacks, by gunmen or bomb-throwers. No warnings were given before soldiers opened fire.

The casualties are listed in the order in which they were killed.

John ‘Jackie’ Duddy, age 17. Shot as he ran away from soldiers in the car park of Rossville Flats. The bullet struck him in the shoulder and entered his chest. Three witnesses said they saw a soldier take deliberate aim at the youth as he ran. He was the first fatality on Bloody Sunday. Both Saville and Widgery concluded that Duddy was unarmed.

Michael Kelly, age 17. Shot in the stomach while standing at the rubble barricade on Rossville Street. Both Saville and Widgery concluded that Kelly was unarmed. The Saville Inquiry concluded that 'Soldier F’ shot Kelly.

Hugh Gilmour, age 17. Shot as he ran away from soldiers near the rubble barricade. The bullet went through his left elbow and entered his chest. Widgery acknowledged that a photograph taken seconds after Gilmour was hit corroborated witness reports that he was unarmed. The Saville Inquiry concluded that 'Private U’ shot Gilmour.

William Nash, age 19. Shot in the chest at the rubble barricade. Three people were shot while apparently going to his aid, including his father Alexander Nash.

John Young, age 17. Shot in the face at the rubble barricade, apparently while crouching and going to the aid of William Nash.

Michael McDaid, age 20. Shot in the face at the rubble barricade, apparently while crouching and going to the aid of William Nash.

Kevin McElhinney, age 17. Shot from behind, near the rubble barricade, while attempting to crawl to safety.

James 'Jim’ Wray, age 22. Shot in the back while running away from soldiers in Glenfada Park courtyard. He was then shot again in the back as he lay mortally wounded on the ground. Witnesses, who were not called to the Widgery Tribunal, stated that Wray was calling out that he could not move his legs before he was shot the second time. 'Soldier F’ faces charges for his murder.

William McKinney, age 26. Shot in the back as he attempted to flee through Glenfada Park courtyard. 'Soldier F’ faces charges for his murder.

Gerard 'Gerry’ McKinney, age 35. Shot in the chest at Abbey Park. A soldier, identified as 'Private G’, ran through an alleyway from Glenfada Park and shot him from a few yards away. Witnesses said that when he saw the soldier, McKinney stopped and held up his arms, shouting “Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot!”, before being shot. The bullet apparently went through his body and struck Gerard Donaghy behind him.

Gerard 'Gerry’ Donaghy, age 17. Shot in the stomach at Abbey Park while standing behind Gerard McKinney. Both were apparently struck by the same bullet. Bystanders brought Donaghy to a nearby house. A doctor examined him, and his pockets were searched for identification. Two bystanders then attempted to drive Donaghy to hospital, but the car was stopped at an Army checkpoint. They were ordered to leave the car and a soldier drove the vehicle to a Regimental Aid Post, where an Army medical officer pronounced Donaghy dead. Shortly after, soldiers found four nail bombs in his pockets. The civilians who searched him, the soldier who drove him to the Army post, and the Army medical officer, all said that they did not see any bombs. This led to claims that soldiers planted the bombs on Donaghy to justify the killings.

Patrick Doherty, age 31. Shot from behind while attempting to crawl to safety in the forecourt of Rossville Flats. The Saville Inquiry concluded that he was shot by 'Soldier F’, who came out of Glenfada Park. Doherty was photographed, moments before and after he died, by French journalist Gilles Peress. Despite testimony from 'Soldier F’ that he had shot a man holding a pistol, Widgery acknowledged that the photographs show Doherty was unarmed, and that forensic tests on his hands for gunshot residue proved negative.

Bernard 'Barney’ McGuigan, age 41. Shot in the back of the head when he walked out from cover to help Patrick Doherty. He had been waving a white handkerchief to indicate his peaceful intentions. The Saville Inquiry concluded that he was shot by 'Soldier F’.

John Johnston, age 59. Shot in the leg and left shoulder on William Street 15 minutes before the rest of the shooting started. Johnston was not on the march, but on his way to visit a friend in Glenfada Park. He died on 16 June 1972; his death has been attributed to the injuries he received on the day. He was the only fatality not to die immediately or soon after being shot.

Paul McCartney (who is of Irish descent) recorded the first song in response only two days after the incident. The single, entitled “Give Ireland Back to the Irish”, expressed his views on the matter. This song was one of few McCartney released with Wings to be banned by the BBC.

The 1972 John Lennon album Some Time in New York City features a song entitled “Sunday Bloody Sunday”, inspired by the incident, as well as the song “The Luck of the Irish”, which dealt more with the Irish conflict in general. Lennon, who was of Irish descent, also spoke at a protest in New York in support of the victims and families of Bloody Sunday.

Irish poet Thomas Kinsella’s 1972 poem Butcher’s Dozen is a satirical and angry response to the Widgery Tribunal and the events of Bloody Sunday.

Black Sabbath’s Geezer Butler (also of Irish descent) wrote the lyrics to the Black Sabbath song “Sabbath Bloody Sabbath” on the album of the same name in 1973. Butler stated, “…the Sunday Bloody Sunday thing had just happened in Ireland, when the British troops opened fire on the Irish demonstrators… So I came up with the title 'Sabbath Bloody Sabbath’, and sort of put it in how the band was feeling at the time, getting away from management, mixed with the state Ireland was in.”

The Roy Harper song “All Ireland” from the album Lifemask, written in the days following the incident, is critical of the military but takes a long-term view with regard to a solution. In Harper’s book (The Passions of Great Fortune), his comment on the song ends “…there must always be some hope that the children of 'Bloody Sunday’, on both sides, can grow into some wisdom”.

Brian Friel’s 1973 play The Freedom of the City deals with the incident from the viewpoint of three civilians.

Irish poet Seamus Heaney’s Casualty (published in Field Work, 1981) criticizes Britain for the death of his friend.

The Irish rock band U2 commemorated the incident in their 1983 protest song “Sunday Bloody Sunday”.

Christy Moore’s song “Minds Locked Shut” on the album Graffiti Tongue is all about the events of the day, and names the dead civilians.

The events of the day have been dramatised in two 2002 television films, Bloody Sunday (starring James Nesbitt) and Sunday by Jimmy McGovern.

The Celtic metal band Cruachan addressed the incident in a song “Bloody Sunday” from their 2004 album Folk-Lore.

Willie Doherty, a Derry-born artist, has amassed a large body of work which addresses the troubles in Northern Ireland. “30 January 1972” deals specifically with the events of Bloody Sunday.

In mid-2005, the play Bloody Sunday: Scenes from the Saville Inquiry, a dramatisation based on the Saville Inquiry, opened in London, and subsequently travelled to Derry and Dublin. The writer, journalist Richard Norton-Taylor, distilled four years of evidence into two hours of stage performance at the Tricycle Theatre. The play received glowing reviews in all the British broadsheets, including The Times: “The Tricycle’s latest recreation of a major inquiry is its most devastating”; The Daily Telegraph: “I can’t praise this enthralling production too highly… exceptionally gripping courtroom drama”; and The Independent: “A necessary triumph”.

In October 2010, T with the Maggies released the song “Domhnach na Fola” (Irish for “Bloody Sunday”), written by Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh and Tríona Ní Dhomhnaill on their debut album.

Read more about the Bogside Massacre

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Troubles, Pt 2

1972

2 January: An anti-internment rally is held in Belfast, North Ireland

3 January: The Irish Republican Army (IRA) explodes a bomb in Callender Street, Belfast, injuring over 60 people.

17 January: Seven men who were held as internees escape from the prison ship HMS Maidstone in Belfast Lough.

21 January: Prime Minister of Northern Ireland Brian Faulkner bans all parades and marches in Northern Ireland until the end of the year.

27 January: Two Royal Ulster Constabulary officers shot dead by IRA in an attack on their patrol car in the Creggan Road, Derry; The British Army and the Irish Republican Army engage in gun battles near County Armagh; British troops fire over 1,000 rounds of ammunition.

28 January: The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association place "special emphasis on the necessity for a peaceful incident-free day" at the next march on 30 January in an effort to avoid violence.

30 January: Bloody Sunday: 27 unarmed civilians are shot (14 are killed) by the British Army during a civil rights march in Derry, Northern Ireland; this is the highest death toll from a single shooting incident during 'the Troubles.’

31 January: British Home Secretary Reginald Maudling to House of Commons on 'Bloody Sunday', "The Army returned the fire directed at them with aimed shots and inflicted a number of casualties on those who were attacking them with firearms and with bombs.”

1 February: British Prime Minister Edward Heath announces the appointment of Lord Chief Justice Lord Widgery to undertake an inquiry into the 13 deaths on 'Bloody Sunday; The Ministry of Defence also issues a detailed account of the British Army's version of events during 'Bloody Sunday.'

2 February: Angry demonstrators burn the British Embassy in Dublin to the ground in protest at the shooting dead of 13 people on 'bloody sunday'

5 February: Two IRA members are killed when a bomb they were planting exploded prematurely.

6 February: A Civil Rights march held in Newry, County Down; very large turn-out with many people attending to protest at the killings in Derry the previous Sunday.

10 February: BBC bans "Give Ireland Back to the Irish" by Wings; two British soldiers are killed in a land mine attack near Cullyhanna, County Armagh; an IRA member is shot dead during an exchange of gunfire with RUC officers.

14 February: Lord Widgery arrives in Coleraine, where the 'Bloody Sunday' (30 January 1972) Tribunal was to be based, and holds a preliminary hearing.

22 Febuary: The Official IRA bombs Aldershot military barracks, the headquarters of the British Parachute Regiment, killing seven people; thought to be in retaliation for Bloody Sunday.

25 February: Attempted assassination of Irish Minister of State for Home Affairs John Taylor who is shot a number of times (the Official Irish Republican Army later claimed responsibility)

1 March: Two Catholic teenagers shot dead by the Royal Ulster Constabulary while 'joy riding' in a stolen car in Belfast.

4 March: Abercorn Restaurant bombing: a bomb explodes in a crowded restaurant in Belfast, killing two civilians and wounding 130.

9 March: Four members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) die in a premature explosion at a house in Clonard Street, Lower Falls, Belfast.

14 March: Two IRA members shot dead by British soldiers in the Bogside area of Derry.

15 March: Two British soldiers killed when attempting to defuse a bomb in Belfast; an RUC officer iskilled in an IRA attack in Coalisland, County Tyrone.

18 March: Ulster Vanguard hold a rally of 60,000 people in Belfast; William Craig tells the crowd: "if and when the politicians fail us, it may be our job to liquidate the enemy.”

20 March: Donegall Street bombing: the Provisional Irish Republican Army detonate its first car bomb on Donegall Street in Belfast; four civilians, two RUC officers and a UDR soldier killed while 148 people were wounded.

24 March: Great Britain imposes direct rule over Northern Ireland

27 March: Ulster Vanguard organise industrial strike against the imposition of direct rule on Northern Ireland by Westminster

30 March: Northern Ireland's Government and Parliament dissolved by the British Government and 'direct rule' from Westminster is introduced.

6 April: The Scarman Tribunal Report, an inquiry into the causes of violence during the summer of 1969 in N Ireland, is published, finding that the Royal Ulster Constabulary had been seriously at fault.

7 April: Three members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) die in a premature bomb explosion in Belfast

10 April: Two British soldiers are killed in a bomb attack in Derry.

14 April: The Provisional Irish Republican Army explodes twenty-four bombs in towns and cities across Northern Ireland.

15 April: A member of the Official Irish Republican Army is shot dead by British soldiers at Joy Street in the Markets area of Belfast close to his home; a member of the British Army is shot dead by the Official IRA in the Divis area of Belfast.< April: Two British soldiers are shot dead by the Official Irish Republican Army (OIRA) in separate incidents in Derry.

18 April: The Widgery Report on 'Bloody Sunday' in Northern Ireland is published, causing outrage among the people of Derry who call it the "Widgery Whitewash.”

19 April: British Prime Minister Edward Heath confirms that a plan to conduct an arrest operation, in the event of a riot during the march on 30 January 1972, was known to British government Ministers in advance.

22 April: An 11-year-old boy killed by a rubber bullet fired by the British Army in Belfast; he was the first to die from a rubber bullet impact.

22 April: The Sunday Times Insight Team publish their account of the events of 'Bloody Sunday.’

10 May: An Irish Republican Army bomb starts a fire that destroys the Belfast Co-operative store.

13 May: Battle at Springmartin: following a loyalist car bombing of a Catholic-owned pub in the Ballymurphy area of Belfast, clashes erupt between PIRA, UVF and British Army.

14 May: 13 year old Catholic girl is shot dead by Loyalist paramilitaries in Ballymurphy, Belfast.

17 May: The Irish Republican Army (IRA) fires on workers leaving the Mackies engineering works in west Belfast (Although the factory was sited in a Catholic area it had an almost entirely Protestant workforce.

21 May: The Official Irish Republican Army (OIRA) kidnaps and shoots dead William Best (19), a soldier in the Royal Irish Rangers stationed in Germany whilst on leave at home.

22 May: Over 400 women in Derry attack the offices of Official Sinn Féin in Derry, North Ireland, following the shooting of William Best by the Official Irish Republican Army.

24 May: Official Irish Republican Army (OIRA) kidnaps and shoots dead William Best (19), a soldier in the Royal Irish Rangers stationed in Germany whilst on leave at home.

26 May: The Irish Republican Army (IRA) plant a bomb in Oxford Street, Belfast, killing a 64 year old woman.

28 May: Four Provisional Irish Republican Army volunteers and four civilians killed when a bomb they were preparing exploded prematurely at a house in Belfast.

29 May: The Official IRA announce a ceasefire.

2 June: British soldiers die in an IRA land mine attack near Rosslea, County Fermanagh.

11 June: Gun battle between Loyalist and Republican paramilitaries break out in the Oldpark area of Belfast.

13 June: The Irish Republican Army invites British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Willie Whitelaw to 'Free Derry'; Whitelaw rejects offer and reaffirms his policy to not "let part of the United Kingdom ... default from the rule of law.”

14 June: Members of the NI Social Democratic and Labour Party hold a meeting with representatives of the Irish Republican Army in Derry; the IRA representatives outline their conditions for talks with the British Government.

15 June: The Social Democratic and Labour Party meet Secretary of State for Northern Ireland W Whitelaw, to present the IRA's conditions for a meeting.

18 June: 3 members of the British Army are killed by an Irish Republican Army (IRA) bomb in a derelict house near Lurgan, County Down.

19 June: A Catholic civilian is shot dead by the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the Cracked Cup Social Club, Belfast; Secretary of State for Northern Ireland William Whitelaw concedes 'special category' status, or 'political status' for paramilitary prisoners in Northern Ireland.

20 June: Secret Meeting Between IRA and British Officials held.

22 June: The Irish Republican Army announce that it would call a ceasefire from 26 June 1972 provided that there is a "reciprocal response" from the security forces.

24 June: The Irish Republican Army (IRA) kill 3 British Army soldiers in a land mine attack near Dungiven, County Derry.

26 June: IRA proclaims resistant in North-Ireland; The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) begin a "bi-lateral truce" as at midnight; The Irish Republican Army (IRA) kill two British Army soldiers in separate attacks during the day.

30 June: Ulster Defence Association (UDA) begin to organise its own 'no-go' areas (this is a response to the continuation of Republican 'no-go' areas and fears about concessions to the IRA).

2 July: Two Catholic civilians are shot and killed in Belfast by Loyalist paramilitaries, probably the Ulster Defence Association (UDA)

3 July: The Ulster Defence Association and the British Army come into conflict about a 'no-go' area at Ainsworth Avenue, Belfast

4 July: The Royal Ulster Constabulary forward a file about the killings on 'Bloody Sunday' (30 January 1972) to the Director of Public Prosecutions for Northern Ireland

5 July: Two Protestant brothers are found shot dead outside of Belfast (speculation that they were killed by Loyalists because they had Catholic girlfriends).

7 July: Secret Talks Between IRA and British Government: Gerry Adams is part of a delegation to London for talks with the British Government; 7 people are killed in separate incidents across Northern Ireland.

9 July: Springhill Massacre: British snipers shoot dead five Catholic civilians and wounded two others in Springhill, Belfast; The ceasefire between the Provisional IRA and the British Army comes to an end.

13 July: A series of gun-battles and shootings erupt across Belfast between the Provisional Irish Republican Army and British Army soldiers.

18 July: The 100th British soldier to die in the Northern Ireland "troubles" is shot by a sniper in Belfast; Leader of the British Labour Party Harold Wilson holds meeting with representatives of the Irish Republican Army.

21 July: Bloody Friday: within the space of seventy-five minutes, the Provisional Irish Republican Army explode twenty-two bombs in Belfast; six civilians, two British Army soldiers and one UDA volunteer were killed, 130 injured.

22 July: 2 Catholics are abducted, beaten, and shot dead in a Loyalist area of Belfast.

31 July: Operation Motorman: the British Army use 12,000 soldiers supported by tanks and bulldozers to re-take the "no-go areas" controlled by the Provisional Irish Republican Army; Claudy bombing: nine civilians were killed when three car bombs exploded in County Londonderry, North Ireland; no group has since claimed responsibility.

9 August: There is widespread and severe rioting in Nationalist areas of Northern Ireland on the anniversary of the introduction of Internment.

11 August: Two IRA members are killed when a bomb they were transporting exploded prematurely.

12 August: British soldiers are killed by an IRA booby trap bomb in Belfast.

14 August: A Catholic civilian is shot dead during an IRA attack on a British Army patrol in Belfast.

22 August: IRA bomb explodes prematurely at a customs post at Newry, County Down - 9 people, including three members of the IRA and five Catholic civilians, are killed in the explosion.

23 August: 4 civilians and 1 British soldier are injured in separate overnight shooting incidents in North Ireland.

2 September: The headquarters of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) in Belfast is severely damaged by an IRA bomb.

10 September: 3 British soldiers are killed in a land mine attack near Dungannon, County Tyrone.

14 September: 2 people are killed and 1 mortally wounded in a Ulster Volunteer Force bomb attack on the Imperial Hotel, Belfast.

20 September: The Social Democratic and Labour Party issues a document entitled "Towards a New Ireland", proposing that the British and Irish governments should have joint sovereignty over Northern Ireland.

6 October: Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Jack Lynch closes the Sinn Féin office in Dublin.

10 October: 3 members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) die in a premature explosion in a house in Balkan Street, Lower Falls, Belfast.

14 October: North Irish Loyalist paramilitaries raid Headquarters of the 10 Ulster Defence Regiment in Belfast and steal rifles and ammunition.

16 October: 2 members of the Offical Irish Republican Army are shot dead by the British Army in County Tyrone. Protestant youth members of the Ulster Defence Association, and a UDA member are run over by British Army vehicles during riots in east Belfast.

17 October: The Ulster Defence Association open fire on the British Army in several areas of Belfast.

19 October: The Ulster Defence Association open fire on the British Army in several areas of Belfast.

23 October: Loyalist paramilitaries carry out raid on an Ulster Defence Regiment.

24 October: British soldiers kill 2 Catholic men at a farm at Aughinahinch, near Newtownbbutler, County Fermanagh.

30 October: The Northern Ireland Office issues a discussion document 'The Future of Northern Ireland'; the paper states Britain's commitment to the union as long as the majority of people wish to remain part of the United Kingdom; Loyalist paramilitaries carry out a raid on Royal Ulster Constabulary station in County Derry, and steal 4 British Army Sterling sub-machine Guns.

31 October: 2 Catholic children (6 and 4) playing on the street are killed in a Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) car bomb attack on a bar in Ship Street, Belfast.

2 November: Government of the Republic of Ireland introduce a bill to remove the special position of the Catholic Church from the Irish Constitution.

5 November: Vice-President of Sinn Féin Maire Drumm is arrested in the Republic of Ireland.

19 November: Leader of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) Seán MacStiofáin is arrested in Dublin.

20 November: 2 British soldiers are killed in a booby trap bomb in Cullyhanna, County Armagh.

24 November: Taoiseach Jack Lynch meets with British Prime Minister Edward Heath in London to give Irish approval to Attlee's paper stating new arrangements should be 'acceptable to and accepted by the Republic of Ireland'

26 November: Bomb explosion at the Film Centre Cinema, in O’Connell Bridge House in Dublin.

28 November: 2 IRA members are killed in a premature bomb explosion in the Bogside area of Derry.

1 December: 2 people killed and 127 injured when 2 car bombs explode in the centre of Dublin, Republic of Ireland

20 December: Five civilians (four Catholics, one Protestant) killed in gun attack on the Top of the Hill Bar in Derry, North Ireland.

28 December: 2 people are killed in a Loyalist bomb attack on the village of Belturbet, County Cavan, Republic of Ireland.

29 December: President of Sinn Féin Ruairi O Bradaigh is arrested and held under new legislation in Republic of Ireland.

#ulster#northern ireland#irish republican army#sinn fein#the troubles#belfast#united kingdom#edward heath#derry

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

MA Fashion and Textile Practices Major Project Path - 7th August

Irish band U2′s song Sunday Bloody Sunday recalls the massacre which took place on Sunday 30th January 1972 between civil rights demonstrators and the British Army’s Parachute Regiment and was classed as one of the worst days of Northern Ireland’s three decade conflict called ‘The Troubles’.

youtube

U2 [U2]. (2009, Dec 14). U2 - Sunday Bloody Sunday (Official Video) [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EM4vblG6BVQ

‘The Troubles’ were said to have begun on the 5th October 1968 when a group of local activists joined forces with members of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) in protest for civil rights. A previous demonstration had been held in regards to favouritism over the local authority's housing allocation between the Catholic Nationalists and Protestant Unionists. On the day in question the attention was turned to the housing policy of unionist-controlled Londonderry Corporation. Officers from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) waited as the demonstration began, but after much heated debating a riot began. None were killed that day but many were injured. A student Grainne McCafferty was there on that day with her husband Michael, Grainne says of that day (2018)

"There was a climate of unease and demand for change and the civil rights movement was borne out of that. That led into 5th October. We had found a voice, stood up for ourselves, refused to accept any longer this yoke that had been placed on us by the state."

Terry Wright (2018) was at school at the time, and since went on to be the deputy chair of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) He recalls that:

“Ultimately, the sense of grievance shared between Protestant and Catholic neighbours, would dissipate. But once the violence started, and there began to be attacks on the Fountain [housing estate], it became sectarian. At least that was the perception. That's when a lot of young Protestants and Unionists who identified with civil rights disengaged"

Go forward four years and ‘The Troubles’ weren’t showing any signs of abating. On the day of Bloody Sunday civil rights demonstrators gathered to make a peaceful protest against a new law which had been passed which stated that authorities had the power to imprison people without trial, called internment. After a few skirmishes the British Army’s Parachute Regiment moved in and fired shots into the crowd, a total of 13 died that day - with a 14th victim dying in hospital four months later, and many more were injured. Backlash to the massacre was widespread - the British Embassy in Dublin was burnt to the ground in retaliation.

The day after the shooting an inquiry was set up by Lord Widgery who was Lord Chief Justice at the time. This tribunal failed to point the finger at any of the soldiers and the British authority was deemed not to blame. When Prime Minister Tony Blair came into power a new inquiry was opened under the jurisdiction of Lord Saville. The Saville enquiry ran for twelve years and concluded that none of the victims had done anything to warrant their shooting. After the report was released a murder investigation was set up by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) to which only one former lance corporal was charged.

The words ‘I can’t believe the news today’ reiterates how unbelievable the news of the massacre was that day, that a situation as horrible as that had sprung from a peaceful protest. These words could easily relate to the news we see on a daily basis, how far must things go before we become so apathetic to the horror and violence shown towards each other that it becomes so believable?

Websites:

BBC News. (2019). Bloody Sunday: What happened on Sunday 30 January 1972?. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-foyle-west-47433319.

McLaughlin, D., Wilson, D., & Kelly, U. (2018). October 1968: The birth of the Northern Ireland Troubles?. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-foyle-west-45625222.

McCann, E. (2019). Bloody Sunday was a very British atrocity – the top brass got away with it. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/mar/15/bloody-sunday-derry-top-brass-one-soldier-charged.

A Medium Corporation. (2018). Sunday Bloody Sunday: The Story behind U2’s most political song. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@thelegendsofmusic/sunday-bloody-sunday-the-story-behind-u2s-most-political-song-f3fd719e1009.

0 notes

Text

Should a convicted man stay in prison if his accuser says he is innocent?

Last week in the unreported case of SB [2019] EWCA Crim. 569 the Court of Appeal gave its reasons for upholding a 68 year old grandfather’s conviction in a historical sex case, even though the only witness against him had told them, on oath, that he was innocent, and that she had lied at his trial.

It was, with respect to the judges, the sort of decision that might cause people to say that the law is an ass.

In another separate, and very well reported, legal development last week, the inquest into the 1974 Birmingham pub bombings concluded with verdicts that the victims had been murdered by the IRA.

On the face of it the two cases are entirely unrelated. The case of SB may or may not be a miscarriage of justice; while the inquest was not directly concerned with the undoubted miscarriages of justice that followed the terrible events of 21 November 1974 when six innocent men were wrongly convicted of mass murder.

The link between SB and the Birmingham Six, is that in both cases the Court of Appeal decided to hear, and to disbelieve, evidence which ought to have led to their respective convictions being quashed. The Six were finally exonerated, while SB remains very firmly behind bars.

The focus of the inquest was of course on those who were concerned with the IRA bombings, not on those (like the six) who were not. It did, nevertheless, hear some evidence from Chris Mullin, the courageous former MP who did so much to secure their release.

The avalanche of litigation that flowed from the arrest and conviction of the Birmingham Six exposed the English legal system, and in particular the Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal at its complacent worst. The case of SB demonstrates that far too little has changed. The common thread running through both cases is the judicial assumption that when, following a conviction, fresh evidence is produced, the assessment of its veracity is best left to judges.

Both the trial and the appeals of the Six were bedevilled by judges wrongly assuming that they knew best.

The pattern was set at the trial, which was conducted by Mr Justice Bridge.

He made little attempt at the trial to conceal his belief in the defendants’ guilt, and, it appeared (at least to the defendants and their supporters) he made every effort to ensure that they were convicted.

The crucial legal argument was an application to exclude evidence of the crucial confession evidence, on the grounds that they were extracted by assaults, ill-treatment and threats. Bridge “helpfully gave a long judgment setting out his reasons for rejecting the defence submissions that the statements were inadmissible and for coming to the conclusion so as to feel sure that the police were telling the truth about the statements and the appellants were not.”1

In summing the case up, he began by telling the jury:

“I am of the opinion … that if the judge has formed a clear view, it is much better to let the jury see that and say so and not pretend to be a kind of Olympian detached observer.”

He was, as Chris Mullin put it, “as good as his word:”

“More than once during the trial he offered explanations for apparent contradictions in the prosecution case that exceeded in ingenuity those offered by crown counsel. Several times he went so far as to take over the questioning of witnesses when he thought crown counsel was not doing well enough. On one occasion, when a policeman briefly strayed off script, Bridge swiftly guided him back to terra firma.”

Once convicted, he confidently told the innocent men that their guilt had been demonstrated by “the clearest and most overwhelming evidence I have ever heard.”

Their first appeal against conviction turned on relatively narrow legal issues, including the the way Bridge J. had conducted the trial, and was dismissed by a court presided over by Lord Chief Justice Widgery, who at least had the excuse that he may have been suffering from undiagnosed senile dementia.

The second – which followed a referral by the Home Secretary – took place 12 years later during the winter of 1987-88. It remains one of the longest criminal appeals in English legal history. It was in this appeal that the Court took it upon itself to adjudicate on the truthfulness or otherwise of numerous witnesses called either by the Six to undermine the convictions, or by the Crown to uphold them.

It was heard by the then Lord Chief Justice, Lord Lane, sitting with O’Connor and Stephen Brown LJJ. The six appellants were represented by three of the country’s finest criminal QCs, Lord Gifford, Michael Mansfield and Richard Ferguson, the Crown by Igor Judge QC, himself later to become a distinguished Lord Chief Justice.

The new witnesses for the appellants supported the men’s case that they had been assaulted by the police before signing their confessions. Some said they even saw assaults taking place. One by one they were cross-examined and expertly taken apart by Mr Judge.

The defence case that there had been a conspiracy “for a completely false case to be put forward by the police witnesses at trial,” was treated by the judges with a mixture of incredulity and scorn.

In his closing argument Judge set out the prosecution case:

“… our submission is that it would have been virtually impossible to find stronger evidence, except perhaps a film of the actual planting of the bombs. And even if,” he added with biting sarcasm, “there had been such a film, that too would no doubt have been disposed of as a police conspiracy. …

“All the time is has to be remembered that the jury, twelve ordinary members of the public, which saw these six defendants and every one of the officers whose names have been specifically mentioned, accepted that they had been honest witnesses and the defendants were dishonest witnesses.”

Although this rather skirted around the point that those twelve ordinary members of the public never heard the evidence which suggested that the police had been dishonest and the defendants honest, the Court of Appeal agreed with Mr Judge.

A former policeman who had seen the men mistreated was “a most unconvincing witness” and “an embittered man,” partly because he had a conviction for stealing £5.00. The evidence of a former policewoman of impeccable character, who changed her account – for no personal gain – and described seeing one of the men being assaulted was “a witness who was not worthy of belief.” A prison officer who saw another of the six covered in bruises on his arrival at Winson Green Prison (supporting their case that they had been beaten up by police officers) “forfeited any credibility he might otherwise have had.” And so on.

With supreme confidence the country’s most senior judges were wrong about almost everything that mattered, and where they were right (about parts of the scientific evidence) they said it didn’t matter anyway.

As we now know beyond a shadow of doubt, the appellants were innocent and their confessions had been – as they always said – extracted from them by torture and ill-treatment. The witnesses torn apart by Mr Judge, and damned by the judges as “unconvincing”, “embittered” or “unworthy of belief,” had all been telling the truth, whilst the police witnesses who had denied ill-treatment had for the most part been lying.

The case is for some reason reported in the Criminal Appeal Reports only in a highly abbreviated form (R v. Callaghan & others (1989) 88 Cr. App. R. 40). Their Lordships’ factual reasoning is dealt with in three sentences:

“[The Court then went on to deal with the reference, and stated that it had no doubt that the verdict of the jury was correct.]

The Court concluded. We have no doubt that these convictions were both safe and satisfactory. The appeals are dismissed.”

It was precisely the outcome that the appellants had tried to avoid, by arguing that the Court should not adjudicate on the fresh evidence itself but should instead order a retrial. It is only this aspect of the case that is reported in the Law Reports.

At the time there was still some room for argument over how the Court of Appeal should deal with fresh evidence. There were two possible approaches to fresh evidence. The first – (see for example Parks (1962) Cr. App R. 29 – was that the Court should not itself decide whether it believed the fresh evidence but should merely decide whether it was capable of belief, and capable of affecting the verdict of a jury. If it was both, the conviction would have to be considered unsafe. That had been the common practice of the Court until 1974. However, in Stafford and Luvaglio (1974) 58 Cr. App. R. 256 the House of Lords had ruled that the correct question for the Court was not whether a jury might reach a different conclusion if it heard the fresh evidence, but whether the Court of Appeal itself felt that the conviction was safe. In other words it was for the Court, not a jury, to assess the veracity of the evidence. It might be objected, indeed it had been very persuasively argued by Lord Devlin,2 that such an approach leads to an awkward hybrid of trial of the facts by two different courts, where a defendant can be judged guilty even though a jury has never heard the full evidence in his favour.

Nevertheless, the Court of Appeal in the Birmingham case unhesitatingly followed Stafford, leading them into catastrophic error.

Although the Six were freed three years later (after the Crown Prosecution Service conceded their convictions could no longer be supported), the Stafford approach to fresh evidence remains the law. That was confirmed in 2001 in Pendleton [2001] UKHL 66. Giving judgment in that case, Lord Bingham added a warning:

“… save in a clear case [the Court of Appeal] is at a disadvantage in seeking to relate that evidence to the rest of the evidence which the jury heard. For these reasons it will usually be wise for the Court of Appeal, in a case of any difficulty, to test their own provisional view by asking whether the evidence, if given at the trial, might reasonably have affected the decision of the trial jury to convict. If it might, the conviction must be thought to be unsafe.”

Which brings us back to the Court’s decision last week to uphold the conviction of a man even though the only witness against him admitted that she lied.

On 5th February 2018 he was convicted at the Snaresbrook Crown Court of sexually abusing his grand-daughter. In order to preserve the anonymity of his grand-daughter we must call her “M” and him “SB”. Over a period of about 6 years, starting when she was 3 or 4 years old, the jury found, on M’s evidence alone, that he had penetrated her vagina with his fingers. She grew into “a fragile and troubled teenager who was self-harming” and when she was nearly 14 she complained about the abuse to her mother. A little later she complained in more detail to a counsellor,

“M told the counsellor that her grandfather had been doing sexual things to her whilst she was a child living with her grandparents. She said that this had happened more than once.She said to the counsellor that she (M) had only realised it was wrong after doing sex education classes at school in year 8. She then kept it to herself, feeling that it was her fault. In the meantime she had started self-harming. The counsellor reported these allegations.”

SB was sentenced to 12 years imprisonment.

It is the sort of case that is now routine in Crown Courts. There was no corroboration for the complaint; but nor was there any particularly obvious reason why M should have been lying.

The counsellor contacted the police who, in June 2016, conducted an evidential interview on video with M (known in the jargon as an “ABE” interview, the acronym standing for “achieving best evidence”). The interview was conducted:

“… objectively, sensitively and fairly by an experienced female police officer. M gave her answers in a seemingly articulate, direct and clear way, albeit clearly in a nervous and sometimes embarrassed way. She provided considerable detail to her allegations.”

The grandfather was interviewed by the police and denied everything.

There was then a lamentable but entirely typical delay of over 18 months while the defendant was charged, pleaded not guilty and awaited the trial which eventually took place in February 2018.

There was a straw in the wind suggesting that perhaps all was not quite right in December 2017. M told the police that she did not want to go to court. There is nothing in itself very unusual or sinister about that: lots of truthful witnesses, especially young witnesses, are reluctant to give evidence, for reasons that are too obvious to need explanation. The Officer in the Case, PC Milne, visited her at school to discuss her concerns. A dispute later arose over what he said to her at the meeting. In any event, when the trial took place M gave evidence, seemingly with no particular problems.

Her ABE interview was played to the jury and she was cross-examined by the defendant’s barrister. The cross-examination was, said the Court of Appeal, “thorough and professional.” To some of the questions she replied “I don’t remember,” but overall she stood by her complaint. It was suggested to her that she was lying and that she had perhaps been prompted by her mother to make up things against her grandfather. Her mother had in the past suggested that SB had behaved in a “sexually inappropriate way” with her (the mother), and had “concerns about how he on occasion had behaved with regard to M as a child,” (to quote the vague and slightly strained way it is put in the Court of Appeal judgment). In any case M rejected the suggestions. She was re-examined by prosecution counsel and asked why she was making the allegations. She replied that she wanted him to “get what he deserves.”

The Court of Appeal described the way she gave her evidence:

“… articulate, direct and clear …, albeit clearly in a nervous and sometimes embarrassed way.”

Her demeanour, the judges thought, was “impressive.”

SB gave evidence denying her allegations in their entirety.

Everyone agreed that the judge’s summing up was fair. The jury convicted by a majority of 11 – 1 and the defendant was duly sentenced and taken to gaol.

The case then ceased to be routine (and I am afraid the need for anonymity means we get into something of an alphabet soup for which I apologise).

M had second thoughts. According to her mother, P, she told her within days of the conviction that she had lied in court. P said she was shocked and rang the Officer in the Case, DC Milne, to tell him. DC Milne denied that anything of the sort had happened.

M also told her Uncle R (the defendant’s son). She said this was because “he has always been the understanding one in the family and I knew he would listen to me.” R contacted his brother, B, who was a criminal solicitor. B gave them the name of a solicitor, and M and her Uncle R went to see him. M’s mother did not come too, apparently because she was at work that day.

The solicitor prepared a statement. She said that her grandfather had not abused her. Her evidence had been untrue. She had made the allegations up “to seek attention from my family, teachers and classmates.” She told the counsellor, she said, for the same reason “to draw more attention to myself.” She also said that the police had told her the case was “very unlikely to go to court,” and that she was “not informed of the consequences that would follow if the allegations I made were believed until after the proceedings had commenced, by which time I was too scared to say that I had lied. I now fully understand the severity of my allegations and the consequences of my actions….” The final two paragraphs read as follows:

“13. When I gave evidence at Snaresbrook Crown Court, I did not want to lie any more and answered most questions with “I don’t know” or “I don’t remember”. I hoped that this would make things right and that my grandfather would be found “not guilty”. I was shocked and horrified to discover that my grandfather was not only convicted but had gone to prison. This was never my intention and was not what was supposed to happen. I was just supposed to get attention and that would be it.

“14. I now realise the severity of my actions and sincerely regret them. After my grandfather went to prison, I knew I had to do the right thing and tell the truth. I therefore confided in my uncle, [R]. He has always been the understanding one in the family and I knew he would listen to me. With his help, I have come to see a solicitor and make this statement of my own free will. No one has pressurised me and no one has told me what to do. I am making this statement because it is the right thing to do and I want to tell the truth. I am truly sorry for what I have done.”

The retraction statement was sent to the CPS and the police.

The police decided to arrest M on suspicion of perjury. She was interviewed under caution, but on legal advice she declined to answer any of the questions put to her. She was not charged.

Meanwhile SB had appealed against his convictions, the sole ground being that M had now retracted her allegations, and had admitted that she lied in court.

On any objective view, M’s retraction meant that the case against SB had collapsed. No jury would have been able to convict him on the evidence of a witness who said in clear terms that he was innocent. Indeed, unless M reverted to her original account, and probably not even then, the CPS could not prosecute him.

However, following the law as set out in Stafford and Pendleton, and (although nobody mentioned it) the Birmingham Six second appeal, the judges decided that it was their job to assess whether M was now telling the truth.

This meant that she had to give evidence and face cross-examination, this time by the prosecution, in the Court of Appeal. It is not clear whether this was done by video-link or whether M, by then 17 years old, was required to give evidence in open court.

Whatever the pressures on her in the original trial, they are likely to have been much greater in the Court of Appeal. Rather than have her evidence in chief on a video recording that could be played to the court, she had to tell the judges that she had been lying at the original trial. If she admitted lying at the trial she was admitting perjury, an offence for which she had already been arrested and interviewed. Presumably her solicitor – who had advised her not to answer questions in the police station – had already explained to her that a witness is equally allowed to refuse to answer questions in court that might involve admitting to a criminal offence. Even if they had not, the Court of Appeal judges told her the same thing. Had she wanted to say “actually I’d rather not answer that question,” or “no comment,” as in the police interview, she could have done so without any legal consequences.

Despite this warning she chose to answer the questions, albeit (according to the judgment) “in a markedly different manner from that revealed in her ABE interview” and was also notably hesitant on occasions in giving answers to direct questions.” Her grandfather had not sexually assaulted her. She added – or as the Court put it “embroidered” – that when she saw DC Milne at school in December 2017 he had threatened her with arrest if she tried to withdraw her allegation. Lord Justice Davis described this evidence as “absurd” and “not credible,” although of course it is exactly what happened when she actually did withdraw it. There is an unhappy echo of Lord Lane’s words about the defence witnesses at the Birmingham Six appeal.

The Court then set out the reasons for disbelieving her (I suppose it is implicit that they were “sure” on the criminal standard of those reasons):

They made the general observation that the retraction statement was written in language that was scarcely that of a 16 year old. The phrase “my momentary lapse of judgment in making the false allegations” was suich That was unsurprising. No-one was suggesting that it was written by a 16 year old. It was written by her solicitor, trying to convey her instructions as clearly and as accurately as possible, and then signed by M as accurately reflecting her evidence. People – whether 16 or older – very rarely speak in the language of a witness statement. Solicitors and police are meant to use the witness’s own words as far as possible, but in practice they often revert to their own style of writing.

More specifically the Court set out their (cumulative) reasons for rejecting her “retraction” evidence:

(1) “M’s allegations in her ABE interview are detailed and (on the face of it) compelling and consistent. It is difficult to credit that a fifteen year old girl could maintain such an account if it was all a lying account.” In fairness, the Court acknowledged that such things could happen.

(2) “M thereafter consistently maintained that account up to and including trial: when she had both re-studied her ABE interview and had ample other opportunity to withdraw her allegations. She never did. Nor did she at any time before or at trial tell her mother that her account was false and (as she confirmed to us) P throughout had believed at that time that M’s complaints were true.”

(3) M must have known throughout that her allegations were very serious. It is also difficult to comprehend why she would maintain that account at trial and then, as is now alleged, just two or three days later (after conviction) tell her mother that it was false.

(4) The Court rejected the evidence of both M and her mother, P, that M told her mother 2 or 3 days after the trial that she had lied at the trial. The “clear tenor of her retraction statement is that the first person she told was R.”

(5) It also rejected as “absurd” M’s evidence that when DC Milne saw her at school in December 2017 he had threatened her with arrest if she did not go to court.

(6) M had in her ABE interview, “volunteered comments about conversations with her grandmother concerning her grandfather. This, if untrue, ran a high risk of being exposed as untrue: as the grandmother could be approached to verify such conversations (the grandmother gave no evidence at trial).”

(7) M had made consistent – albeit late – complaints to her mother, to her counsellor and to the police. She maintained those complaints at trial and adhered to them in cross-examination and re-examination.

(8) Prosecution counsel saw M shortly before and after she gave evidence at the trial. “His recollection and notes record M as, though nervous, happy with the way she was being treated. No indication whatsoever was given to him that she wanted to withdraw her allegations or to cause him to doubt what she was saying.”

(9) The Court accepted DC Milne’s evidence that no indication of withdrawal was given to him until after SB was sentenced.

(10) M’s suggestion that the police had told her that it was unlikely the case would go to court was rejected as “utterly implausible.”

Some may find these reasons persuasive, some may think they smack of an attempt to shore up a conviction on evidence which had disappeared once the chief prosecution witness changed sides.

Reasons 1 and 2 – her consistency up to and including the trial – could apply to most complaints, whether true or false. Indeed, if a single complainant were to tell her mother before trial that she had lied it is unlikely that the CPS would continue to pursue the prosecution at all.

A possible answer to Reason 3 (why would she change her story just three days after the trial) might be that it was not until SB was convicted that she realised the enormity of what she had done, or found the courage to try to make amends.

Reason 4 |quite reasonably highlights an inconsistency between her retraction statement and her sworn evidence, but it also highlights the oddity that her mother, who appears to have thoroughly disliked SB and had believed her daughter up till that point, actually corroborated her new evidence on the point.

Reason 5 (her “absurd” evidence that DC Milne threatened to arrest her in December 2017) is rendered less than absurd by the fact that she was arrested in May 2018.

Reason 6 is impossible for anyone else to assess because we have no idea what the comments to the grandmother were, or for what reasons the grandmother was not called to give evidence.

Reason 7 (consistent complaints to her mother, the counsellor and the police) seems a make-weight to get the number of reasons up to a round 10, and pretty much a rehash of Reasons 1 and 2.

Reason 8 (no indication of unwillingness to prosecution counsel and prosecution counsel’s lack of doubt) is another restatement of her consistency, and to rely on prosecution counsel’s lack of doubt is, frankly, irrelevant. One might as well rely on defence counsel’s doubt as a reason for disbelieving her.

Reason 9 (acceptance of DC Milne’s evidence rather than M’s) I am not sure if this is really a separate reason, or one that follows from the court’s rejection of M’s evidence as “absurd.”

Reason 10 (rejection of M’s evidence that it was “utterly implausible” that the case was unlikely go to court) It does seem unlikely that she would have been told such a thing, but ultimately this point was peripheral to the main question of whether she had been lying about the abuse.

But whatever you think of the Court’s reasoning, the fact remains that the jury were never able to hear M’s evidence as it now is, and to reach a verdict on all the relevant evidence.

Troublingly, the judges do not appear to have asked the question that Lord Bingham suggested should be asked in “a case of any difficulty,” namely:

“… whether the evidence, if given at the trial, might reasonably have affected the decision of the trial jury to convict. If it might, the conviction must be thought to be unsafe.”

That aside, criticism of the individual judges would be misplaced. I have appeared in front of all three and know them to be careful, conscientious and fair. Their assessment of M’s evidence may even be correct, although history shows that judges assessing fresh evidence can get it wrong. My criticism is of a law that requires the judges to make such an assessment when that should be the function of a jury.

The only certain thing about the case is that the single witness implicating SB has committed perjury. If that alone does not make the conviction unsafe in the eyes of the law, then there is something badly wrong with the law.

1 Callaghan & others (1989) 88 Cr. App. R. 40

2 See Patrick Devlin The Judge and the Jury: Sapping and Undermining Published in The Judge, 1981

The post Should a convicted man stay in prison if his accuser says he is innocent? appeared first on BarristerBlogger.

from All About Law http://barristerblogger.com/2019/04/07/should-a-convicted-man-stay-in-prison-if-his-accuser-says-he-is-innocent/

1 note

·

View note

Link

LONDONDERRY: One former British soldier will be prosecuted for two murders in the “Bloody Sunday” killings of 13 unarmed Catholic civil rights marchers in Londonderry by British paratroopers in 1972 – one of the most notorious incidents of the Northern Ireland conflict.

The evidence was insufficient to charge 16 other former soldiers, Northern Ireland’s Public Prosecution Service said on Thursday.

Soldiers from the elite Parachute Regiment opened fire on Sunday, Jan. 30, 1972, during an unauthorised march in the Bogside, a nationalist area of Londonderry. They killed 13 people and wounded 14 others, one of whom died later.

A judicial inquiry into the events of Bloody Sunday, which took place at the height of Northern Ireland’s 30-year sectarian conflict, said in 2010 the victims were innocent and had posed no threat to the military.

It was the worst single shooting incident of “The Troubles”, although several bomb attacks by rival militant groups claimed higher death tolls, and Thursday’s decision reignites the controversy.

The prosecutor announced on Thursday that there was sufficient evidence to prosecute “Soldier F” for the murder of James Wray and William McKinney and for the attempted murders of Joseph Friel, Michael Quinn, Joe Mahon and Patrick O’Donnell.

But “in respect of the other 18 suspects, including 16 former soldiers and two alleged Official IRA members, it has been concluded that the available evidence is insufficient to provide a reasonable prospect of conviction,” a prosecutor’s statement said.

Victim’s families said they were disappointed by the decision. Their lawyers said they would challenge in the High Court any prosecutorial decision that did not withstand scrutiny.

“We would like to remind everyone that no prosecution or if it comes to it no conviction does not mean not guilty, it does not mean that no crime was committed, it does not mean that those soldiers acted in a dignified and appropriate way,” Mickey McKinney, brother to one of the victims, told a news conference.

Before a prosecutor’s service briefing at a Londonderry hotel, the families marched from the Bogside and sang civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome”.

Linda Nash, the brother of William Nash, a 19-year-old killed on the day, was tearful when she emerged from the hotel. Veteran civil rights campaigner Eamonn McCann’s hands shook as he comforted her.

“MASSACRE OF INNOCENTS”

Director of Public Prosecutions for Northern Ireland, Stephen Herron said he was conscious relatives faced an “extremely difficult day.”

“However, much of the material which was available for consideration by the Inquiry is not admissible in criminal proceedings, due to strict rules of evidence that apply,” he said.

The British government said it would provide full legal support to the soldier who will face prosecution. No other details were released by prosecutors of the identity of the man, who would be at least in his 60s.

“The welfare of our former service personnel is of the utmost importance,” Defence Minister Gavin Williamson said in a statement. “Our serving and former personnel cannot live in constant fear of prosecution.”

Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney said it was important that no one said anything to prejudice the process following Thursday’s decision, adding that his thoughts were with all of the families.

The Saville Report, which was published in 2010 after a 12-year inquiry by High Court Judge Lord Saville, reversed the findings of a hastily-convened inquiry from 1972 by another judge, Lord Widgery, who concluded the soldiers only fired after being fired upon.

The Bloody Sunday killings caused widespread anger at the time – not least in the United States, where support for the Irish Republican cause runs high – and nearly 50 years later the incident remains highly emotive.

Supporters of the paratroopers say they were acting under extremely confused and stressful conditions, and it is unfair to pursue them so long after the event when many suspected Irish Republican Army (IRA) bombers and gunmen have been told they will no longer face arrest under the 1998 peace accords.

Victims’ families and other voices say they must nonetheless be held to account for their actions.

The Saville Report said the paratroopers opened fire without warning and that none of the casualties has posed a threat.

The 1998 Good Friday Agreement brought a close to a conflict in which about 3,500 people were killed. British troops subsequently withdrew from the province, but tensions still persist and a car bomb exploded outside Londonderry’s main courthouse in January. No one was injured.

The decision to prosecute came a week after Britain’s minister for Northern Ireland, Karen Bradley, was forced to apologise for saying that killings by British soldiers and police were “not crimes”.

Sinn Fein, the former political wing of the IRA who are now the largest nationalist party in the province, said they shared the families’ disappointment and “sense of incredulity” at the decision.

“The decision to prosecute just one ex-soldier does not change the fact that Bloody Sunday was a massacre of innocents,” Sinn Fein’s Northern Ireland leader Michelle O’Neill said in a statement.

The post British soldier to face murder charges over 1972 “Bloody Sunday” appeared first on ARYNEWS.

https://ift.tt/2XUyQxD

0 notes

Text

bloody elbow picks

Bloody Sunday – sometimes called the Bogside Massacre – was an incident on 30 January 1972 in the Bogside area of Derry, Northern Ireland, when British soldiers shot 28 unarmed civilians during a peaceful protest march against internment. Fourteen people died: thirteen were killed outright, while the death of another man four months later was attributed to his injuries. Many of the victims were shot while fleeing from the soldiers and some were shot while trying to help the wounded. Other protesters were injured by rubber bullets or batons, and two were run down by army vehicles. The march had been organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA). The soldiers involved were members of the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, also known as “1 Para”.

Two investigations have been held by the British government. The Widgery Tribunal, held in the immediate aftermath of the incident, largely cleared the soldiers and British authorities of blame. It described the soldiers’ shooting as “bordering on the reckless”, but accepted their claims that they shot at gunmen and bomb-throwers. The report was widely criticised as a “whitewash”. The Saville Inquiry, chaired by Lord Saville of Newdigate, was established in 1998 to reinvestigate the incident. Following a 12-year inquiry, Saville’s report was made public in 2010 and concluded that the killings were both “unjustified” and “unjustifiable”. It found that all of those shot were unarmed, that none were posing a serious threat, that no bombs were thrown, and that soldiers “knowingly put forward false accounts” to justify their firing. On the publication of the report, British prime minister David Cameron made a formal apology on behalf of the United Kingdom. Following this, police began a murder investigation into the killings.

Bloody Sunday was one of the most significant events of “the Troubles” because a large number of civilian citizens were killed, by forces of the state, in full view of the public and the press. It was the highest number of people killed in a single shooting incident during the conflict. Bloody Sunday increased Catholic and Irish nationalist hostility towards the British Army and exacerbated the conflict. Support for the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) rose and there was a surge of recruitment into the organisation, especially locally.

see more at wikipedia

youtube

Check More at drysdalefightforus.com

The post bloody elbow picks appeared first on Drysdale Fight For Us Jiu Jitsu.

from WordPress http://ift.tt/2vmjSox

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Today marks the 45th anniversary of Bloody Sunday sometimes also referred to as the Bogside Massacre.

Sunday January 30th 1972 started as any other Sunday in Derry but would end with tragedy and a population thrown into a dark backlash of opinion towards the British.

British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians during a peaceful protest march against internment. Fourteen people died: thirteen were killed outright, while the death of another man four months later was attributed to his injuries. Many of the victims were shot while fleeing from the soldiers and some were shot while trying to help the wounded. Other protesters were injured by rubber bullets or batons, and two were run down by army vehicles.The march had been organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA). The soldiers involved were members of the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, also known as “1 Para”.

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) organised a march to start at 3PM from the Bishops Field area of the Creggan. The march had already been deemed illegal by the British and from previous march’s the police force and the British proved too ruthless against peaceful demonstrators such as the attack on a civil rights march at Burntollet bridge.

The plan for the march was to walk down Creggan Hill, into William Street and onto the Guildhall Square, in the City Centre area. Over 15,000 people attended the march which proceeded from Creggan. The marchers were singing songs with some describing it as a carnival like event. As they reached the William Street area the British Army had set-up barricades so the march was diverted into the Bogside and towards Free Derry Corner, a small area that isolated itself from the Northern Ireland state known as as no-go area for the British forces.Despite this, a number of people continued on towards an army barricade where local youths threw stones at soldiers, who responded with a water cannon, CS gas and rubber bullets.

As the riot began to disperse, soldiers of the 1st Parachute Regiment were ordered to move in and arrest as many of the rioters as possible. In the minutes that followed, some of these paratroopers opened fire on the crowd, killing thirteen men and injuring 13 others, one of whom died some months later.

A large group of people fled or were chased into the car park of Rossville Flats. This area was like a courtyard, surrounded on three sides by high-rise flats. The soldiers opened fire, killing one civilian and wounding six others.This fatality, Jackie Duddy, was running alongside a priest, Father Edward Daly, when he was shot in the back.

While the British Army maintained that its troops had responded after coming under fire, the people of the Bogside saw it as murder. The British government was sufficiently concerned for the Home Secretary to announce the following day an official inquiry into the circumstances of the shootings.

Opinion was further polarised by the findings of this tribunal, led by the British Lord Chief Justice, Lord Widgery. His report exonerated the army and cast suspicion on many of the victims, suggesting they had been handling bombs and guns. Relatives of the dead and the wider nationalist community campaigned for a fresh public inquiry, which was finally granted by then Prime Minister Tony Blair in 1998.

Headed by Lord Saville, the Bloody Sunday Inquiry took 12 years and finally reported in 2010. It established the innocence of the victims and laid responsibility for what happened on the army.

Prime Minister David Cameron called the killings “unjustified and unjustifiable”. The families of the victims of Bloody Sunday felt that the inquiry’s findings vindicated those who were killed, raising the question of prosecutions and compensation.

Bloody Sunday-1972 Today marks the 45th anniversary of Bloody Sunday sometimes also referred to as the Bogside Massacre.

0 notes

Text

#OTD in 1972 – Lord Widgery’s report exonerating “Bloody Sunday” troops was issued.

Publication of the Widgery Report into the events of Bloody Sunday brings an avalanche of criticism and incredulity amongst nationalist and independent commentators. The man who served as the Lord Chief Justice of England from 1971-80 found that British paratroopers were not responsible for the deaths of 13 civilians on the day and that “there would have been no deaths in ‘Derry’ on 30 January if…

View On WordPress

#14 Civilians Murdered#Bloody Sunday#British paratroopers#Derry#Lord Chief Justice of England#Lord Widgery#Lord Widgery Report#Prime Minister David Cameron#Saville Tribunal

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1972 – In what is to become known as Bloody Sunday, the British Army kills 13 civil rights demonstrators in the Bogside district of Derry. A 14th marcher later dies of his injuries.

Thirteen people were shot and killed when British paratroopers opened fire on a crowd of civilians in Derry. Fourteen others were wounded, one later died. The marchers had been campaigning for equal rights such as one man, one vote.

Despite initial attempts by British authorities to justify the shootings including a rushed report by Lord Widgery exonerating the troops, the Saville Report which…

View On WordPress

#Bloody Sunday#Bogside Massacre#Creggan shops#Derry#Dublin#England#Ex-paratroopers#History of Ireland#Irish History#London#March#Northern Ireland#Paratroopers#Saville Report#TD Clare Daly

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1972 – In what is to become known as Bloody Sunday, the British Army kills 13 civil rights demonstrators in the Bogside district of Derry. A 14th marcher later dies of his injuries.

Thirteen people were shot and killed when British paratroopers opened fire on a crowd of civilians in Derry. Fourteen others were wounded, one later died. The marchers had been campaigning for equal rights such as one man, one vote.

Despite initial attempts by British authorities to justify the shootings including a rushed report by Lord Widgery exonerating the troops, the Saville Report which…

View On WordPress

#Bloody Sunday#Bogside Massacre#Creggan shops#Derry#Dublin#England#Ex-paratroopers#History of Ireland#Irish History#London#March#Northern Ireland#Paratroopers#Saville Report#TD Clare Daly

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1972 – Lord Widgery’s report exonerating “Bloody Sunday” troops was issued.

#OTD in 1972 – Lord Widgery’s report exonerating “Bloody Sunday” troops was issued.

Publication of the Widgery Report into the events of Bloody Sunday brings an avalanche of criticism and incredulity amongst nationalist and independent commentators. The man who served as the Lord Chief Justice of England from 1971-80 found that British paratroopers were not responsible for the deaths of 13 civilians on the day and that “there would have been no deaths in ‘Derry’ on 30 January if…

View On WordPress

#14 Civilians Murdered#Bloody Sunday#British paratroopers#Derry#Lord Chief Justice of England#Lord Widgery#Lord Widgery Report#Prime Minister David Cameron#Saville Tribunal

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in Irish History | 19 April:

#OTD in Irish History | 19 April:

1366 – The parliament, alarmed at the apparent undermining by native influences of the settler population’s Englishness, passed the ‘Statutes of Kilkenny’.

1608 – O’Doherty’s Rebellion was launched by the Burning of Derry.

1780 – Henry Grattan moves resolutions in favour of legislative independence in the Irish House of Commons.

1798 – The Earl of Clare began a 3-day visit to Trinity College,…

View On WordPress

#irelandinspires#irishhistory#OTD#1798 United Irishmen Rebellion#19 April#Bloody Sunday#Co. Kerry#Coumeenole Beach#Dunquin#History#History of Ireland#Ireland#Irish Civil War#Irish History#Lord Widgery Report#Photo credit: Michael Corcoran#Statute of Kilkenny#Today in Irish History

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in Irish History | 19 April:

#OTD in Irish History | 19 April:

1366 – The parliament, alarmed at the apparent undermining by native influences of the settler population’s Englishness, passed the ‘Statutes of Kilkenny’.

1608 – O’Doherty’s Rebellion was launched by the Burning of Derry.

1780 – Henry Grattan moves resolutions in favour of legislative independence in the Irish House of Commons.

1798 – The Earl of Clare began a 3-day visit to Trinity College,…

View On WordPress

#irelandinspires#irishhistory#OTD#1798 United Irishmen Rebellion#19 April#Bloody Sunday#Co. Kerry#Coumeenole Beach#Dunquin#History#History of Ireland#Ireland#Irish Civil War#Irish History#Lord Widgery Report#Photo credit: Michael Corcoran#Statute of Kilkenny#Today in Irish History

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1972 – Lord Widgery’s report exonerating “Bloody Sunday” troops was issued.

#OTD in 1972 – Lord Widgery’s report exonerating “Bloody Sunday” troops was issued.

Publication of the Widgery Report into the events of Bloody Sunday brings an avalanche of criticism and incredulity amongst nationalist and independent commentators. The man who served as the Lord Chief Justice of England from 1971-80 found that British paratroopers were not responsible for the deaths of 13 civilians on the day and that “there would have been no deaths in ‘Derry’ on 30 January if…

View On WordPress

#14 Civilians Murdered#Bloody Sunday#British paratroopers#Derry#Lord Chief Justice of England#Lord Widgery#Lord Widgery Report#Prime Minister David Cameron#Saville Tribunal

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in Irish History – 19 April:

1366 – The parliament, alarmed at the apparent undermining by native influences of the settler population’s Englishness, passed the ‘Statutes of Kilkenny’.

1608 – O’Doherty’s Rebellion was launched by the Burning of Derry.

1780 – Henry Grattan moves resolutions in favour of legislative independence in the Irish House of Commons.

1798 – The Earl of Clare began a 3-day visit to Trinity College,…

View On WordPress

#irelandinspires#irishhistory#OTD#1798 United Irishmen Rebellion#19 April#Bloody Sunday#Co. Kerry#Coumeenole Beach#Dunquin#History#History of Ireland#Ireland#Irish Civil War#Irish History#Lord Widgery Report#Photo credit: Michael Corcoran#Statute of Kilkenny#Today in Irish History

5 notes

·

View notes