#Magda Szabó

Text

Una volta tanto lei dovrebbe piuttosto imparare a dimenticare, perché il suo cervello è come la resina: quando qualcosa ci resta impigliato dentro, non esce più.

Magda Szabó

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you do something truly unforgivable, you don’t always realise it, but there is a certain inward suspicion of what you have done.

Magda Szabó, The Door (translated by Len Rix)

14 notes

·

View notes

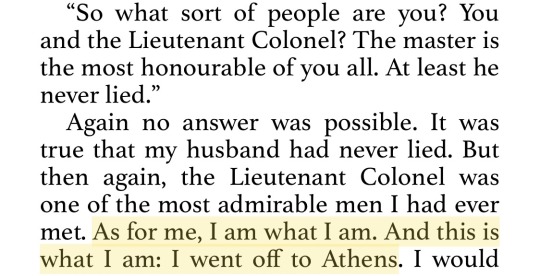

Text

The Door - Magda Szabó

#sometimes when I see people posting quotes I’m like why did you highlight something now my attention is drawn to a phrase that#I’m not sure I would’ve noticed or cared for otherwise#but rn I’m like okay. my turn#the door#magda szabó#words

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s not something that I actually want to write (too many WIPs, hahaha), but listen: SaB Abigail AU.

Abigail is a Hungarian novel by Magda Szabó (it’s available in English), and I’ll be the last person to endorse Hungarian lit in general (too much classroom trauma and misery for my taste), but Abigail is like *chef’s kiss*.

Originally published in 1970 and set during WWII, Abigail is about Georgina “Gina” Vitay, the spoiled, 14 years old daughter of a Hungarian army general. When her father goes on a secret mission, Gina is sent to a religious all-girls boarding school which she hates with passion, seemingly without any reasonable explanation. She clashes with her new classmates whom she thinks to be immature, partially because of their belief in a certain bit of school lore: there is a classical statue of a woman--the eponymous Abigail--with an urn in her hands on the school yard, and the legend has it that if you find yourself in trouble, you should write a letter to Abigail, place it in her urn, and she will help you. As Gina’s relationship with her classmates gets even more dire, she decides to run away, but her attempt is thwarted--however, afterwards she gets a letter from Abigail.

It’s a mystery, it’s a boarding school narrative, it’s a coming of age story, it’s a war narrative... It’s just great, okay?

And there are so many points of similarity that could be exploited for an AU fic: young girl is sent to a cloistered place with its own, and to her very unfamiliar rules and practices. She doesn’t want to be there. There is a war going on in the outside. She is desperate to contact someone on the outside (in the book, there is her father and her sweetheart, but I don’t want to get into spoilers here). And adding such a lore to the Little Palace would just be fun. The writer could also play with who or what is behind “Abigail”--we learn that at the very end of the book, but I don’t want to go into spoilers, because, if you can, read Abigail.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

#vates#magda szabó#szabó magda#idézet#idézetekmindennapra#idezetek#magyar idezet#szerelem#élet#neked#vatesprojekt#vates projekt

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hozzátok haza Blankát!

Szabó Magda - Katalin utca

#magda szabó#katalinutca#magyar irodalom#book illustration#digital art#watercolor#colored pencil#mixed media#myart

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

MAGDA SZABÓ, por Concha Vallejo

Magda Szabò (1917-2007), profesora, poeta, traductora, ensayista, dramaturga y novelista húngara, era una desconocida para los lectores españoles hasta que la publicación en español de su novela La puerta, que en 2003 había obtenido en Francia el Premio Femina a la mejor obra extranjera, les permitió entrar en contacto con una de las escritoras más valoradas de la literatura húngara del Siglo…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

"Once again she had the feeling of being caught up in a play, a play in which she had a totally insignificant role and whose plot was impossible to follow: just as the tragedy reached its climax one of the actors smiled and asked the others if they would like a dried plum."

Magda Szabó, "Abigail"

1 note

·

View note

Text

reread Villette by Charlotte Brontë bc i had it confused with Abigail by Magda Szabó and was really disappointed.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Fawn by Magda Szabó

I have always distrusted good people. I never believed as a child that goodness came naturally. I always suspected that beneath it lay some sort of payment for services past or still to come. If Ambrus was kind enough to send us that leg of pork, it was only because I chopped the wood and picked up the pigswill for him, and the Turkish cake was simply compensation for Béla's sausage fingers and tin ear. My aunt hung gold and jewellery round my neck so that no-one could say a granddaughter of a Marton didn't even have a necklace. It was so much simpler to close the clasp on a necklace than to help my father, when a bit of money would have prolonged his life. When you first started to "take an interest" in me, and tried to find out not what my desires were but whether I had any desires at all, I watched and waited, I was waiting to see how it would turn out with you, and if it would prove to be with you as it was with everyone else — that you were evading some responsibility, or there was something you wanted from me, something you were paying for in advance, a seed you were planting, a score you were settling; the first presents you gave me, the ones I took from you with trembling hands and tears streaming from my eyes, that were thrown in the bin. When you first took me on that rainy evening to show me the view of the mountains in the fog, and we walked along the Fishermen's Bastion, I let you go on ahead so that I could follow a little way behind and pull my tongue out and make faces at you, like Puck. I hated you.

I remember when I caught the flu, it was the first time I'd had it in my life, and you sent a medical professor to me, one of your friends; I was at home, I had an apron on and blue ribbons in my hair, I was barefoot and wiping my hands on the apron when I opened the door, and my cheeks were burning with the fever — I must have looked like a servant raw from the country. I told him the lady actress had gone out and nobody in the house was sick and his journey had been wasted. Then I washed my feet, lay down, took a couple of aspirins and spent the day in bed reading the new play from Romania. I used to watch you talking to old Mr Szalay, you sitting in his porter's lodge listening to the stories he never stopped telling about what his grandson was up to, and looking at those dreadful snaps in which everyone is screwing up their eyes in the sun. I've seen you throw children's balls back up to the balcony for them, and lend money to Pipi, who, as everyone knows, never pays anything back.

In the early days I just laughed at you, and pulled faces at you as soon as the door closed behind you; I laughed at you for being such a "good" person, who always paid your way, and paid up before everyone else did; I wasn't the least interested in your goodness or your considerateness, I wanted something else from you. I didn't want you to "be good" to me, and certainly not that you should "really love me". That was out of the question. (pp. 94-96)

***

Something down there is shining. A ten-fillér coin. It must have been trodden into the ground and then washed clean by the rain; it has been flattened out and the inscription is barely visible — some child must have put it on a tramline. When I was little, children used to drill holes in coins like this and hang them on a cord round their necks; I always put mine aside to spend at the bakery: Csák bácsi had very poor eyesight. Angéla never learned how to handle money; even today she doesn't know the difference between the pengö and the forint.

Snow was falling outside the window; I was watching the flakes swirling around and not looking at you standing there with the bear's head on, and I was thinking that it had been just too hot in the orphanage the day before. You now felt able to leave Angéla, you said; you had needed all that time to be sure that she would still have a circle of friends around her, and the orphanage would be there for her as a kind of sustaining illusion, if you were to leave her permanently; those forty-eight children, the whole set-up and the work she so much loved would keep her together somehow, because she couldn’t survive on her own, and if she didn’t have someone to watch over her and love her and take care of her she would fall to pieces. I took the bears head back and put it on mine with my pigtails sticking out, I sat down on the carpet and gazed back at you; the snow was swirling around behind your head and I was sitting at your feet, in my trousers, with a red ribbon in my hair, and I had no face, it was a bear that stared back at you, a stupid, faithful bear, my eyes blazed through the chink in the mask but they told you nothing. They were looking at you the way a wild animal would.

"Angéla may know her ideology," I heard you say, inside the bear's head, "but she doesn't even know how to fill in an identity declaration." Every quarter you were the one who had to draw up a work schedule because she simply couldn't plan, and she couldn't do percentages and when the accounts came in at the end of the year you would have to carry on doing all that, both for the time being and ever afterwards, even long after we were married.

You were laushing and smoking a cigarette while you said this, you were talking about her as if she were a charming, incompetent baby: I kept nodding and growling, then I pulled the bear's paws back onto my fists; I was thinking that while I was down there bowing before you, supposedly clutching my paws to my heart in gratitude that you should ask me to be your wife, all I wanted was for her to fall into little pieces and disintegrate completely; I wanted her to have to find out how to fill in an identity declaration and make up the end of year accounts, and bring in the coal herself, and know what it is like to be hungry and to have to flee for your life — all those things the rest of us have had to deal with. I just wanted her to evaporate, and never to see her again.

You would of course have to call on her from time to time, you went on, to make sure she had brought the firewood in — she was quite capable of forgetting to do so; she might order enough fuel for the orphanage but without you there wouldn't be a shovelful of coal in the house when the winter came.

I tore off the mask so that you could see my face, and your expression changed instantly. "No," I said, and I began to gather up the things on the table. "Thank you very much but no, I prefer you as a lover."

You didn't kiss me again that evening, and you left shortly afterwards, much earlier than usual; I assumed that you had to do the accounts for the orphanage fair and write Angéla's report for her; she has never, in all her life, managed to fill in an official document.

Juli was still out in the garden, sweeping; I went out to join her, I tied her scarf round my waist, took the broom from her hand and started to sweep — I was sweeping away the tracks you had left along with the snow. Juli stood on the kitchen steps and watched the way I was handling the broom and singing as the snow fell all round me; she had seen from your face what I had said to you. She gaped at me for a short while, then went back into the kitchen, no longer able to stand the sight of me. I was thinking how utterly immoral you were, with your kindness and good heartedness: as vou made your way down the hill you were no doubt thinking how immoral I was too. (pp. 260-63)

0 notes

Text

I believe it was from this moment that [she] truly loved me, loved me without reservation, gravely almost, like someone deeply conscious of the obligations of love, who knows it to be a dangerous passion, fraught with risk.

Magda Szabó, The Door (translated by Len Rix)

7 notes

·

View notes

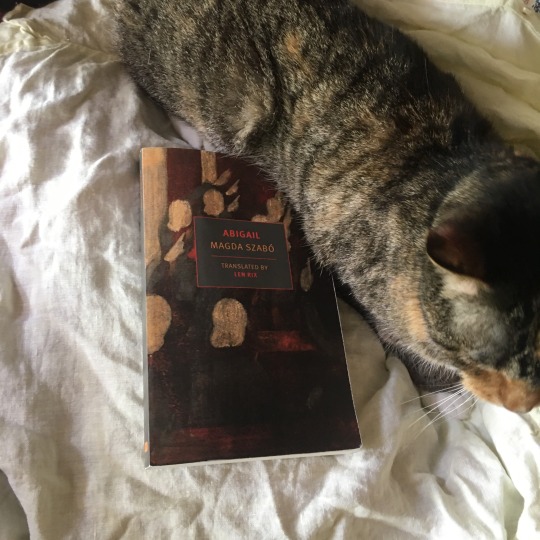

Photo

Abigail by Magda Szabó - 4/5

When my favorite bookstore in town closed they sold all their stock for half-off and though I loathe brand loyalty I must admit I usually enjoy everything NYRB publishes, because it seems like stuff that ought to be considered classics, even if it isn’t (in America at least)! One of the books I picked up was Abigail by Magda Szabó, knowing nothing about it save for the description on the back, which namedrop both Jane Austen and J. K. Rowling. The Austen connection still baffles me, but the best way I have found to describe Abigail is “Harry Potter without the magic… but with still a little bit of magic!” At first I thought this was a sort of surface-level comparison, because Hogwarts was inspired by the long tradition of the boarding-school genre, but without saying too much there is a lot more at play in Abigail that recalls Harry Potter way more than something more episodic like the Claudine series. To be set in WW2-era Hungary sort of gives a lot away already, but the wartime claustrophobia and tension contrasts really well with the everyday schoolgirl antics such as setting pastries on fire in effigy or marrying a fishtank. Though some parts were slow, the narrative was well-constructed and every episode in Gina’s life serves a purpose to the story, so the result is a tight and suspenseful account of wartime Hungary.

0 notes

Text

“She had no idea what life was, or death.”

― Magda Szabó, Katalin Street

1 note

·

View note