#Margaret Rossiter

Text

By Rachel May

Rachel May, English professor and author, came upon Elizabeth Wagner Reed’s book about a decade ago, on Reed’s daughter’s website.

Published April 22, 2023Updated April 24, 2023, 10:50 a.m. ET

This article is part of Overlooked, a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times.

In 1992, the geneticist Elizabeth Wagner Reed self-published “American Women in Science Before the Civil War,” a book highlighting 22 19th-century scientists. One of them was Eunice Newton Foote, who wrote a paper on her remarkable discovery about greenhouse gases, “a phenomenon which is of concern to us even now,” Reed wrote.

Foote was forgotten soon after the paper was read aloud by a male scientist at a conference in 1856 and published the following year. A male scientist was eventually credited with the discovery.

Like Foote, Reed herself fell into obscurity, a victim of the erasure of female scientists that the historian Margaret Rossiter coined the Matilda Effect — named for the sociologist Matilda Joslyn Gage, whose 1870 pamphlet, “Woman as Inventor,” condemned the idea that women did not have the skills to succeed in the field.

Reed, however, made significant contributions to the sciences.

She wrote a landmark study about intellectual disability genetics, helped found a field of population genetics and wrote many more papers on botany, the biology of women and sexism in science.

Reed persisted in her research even when she found herself a widow with a toddler during World War II. By the time of her death, in 1996, in spite of publishing more than 34 scholarly papers, public school curriculums and two books, the record didn’t bend in her favor. It wasn’t until 2020, when the scientist and scholar Marta Velasco Martín published a paper on Reed, that her legacy was resurrected.

Reed was born Elizabeth Wagner on Aug. 27, 1912, in Baguio, in what was then called the Philippine Islands, to Catherine (Cleland) and John Ovid Wagner. John was from Ohio and worked in construction there at the time; Catherine, from Northern Ireland, was working in the Philippines as a nurse.

The family later settled on a farm in Ohio, where Elizabeth grew up picking raspberries “from dawn to dusk,” her son William Reed said in a phone interview.

“She learned how to work really hard,” he added. “I remember her saying how much she loved school, partly because it wasn’t doing farm work.”

At the end of one summer, he said, she used some of her earnings to buy a book about wildflowers in Ohio — “her first purchase was a scientific book.”

She would go on to cultivate wildflowers in her backyard as an adult, volunteer at a wildflower arboretum in Minnesota and write about botany in scientific articles and in educational materials for children. Reed’s daughter, Catherine Reed, told Martín that her mother “loved nature, especially plants, and, wanted to be a scientist from a very early age.”

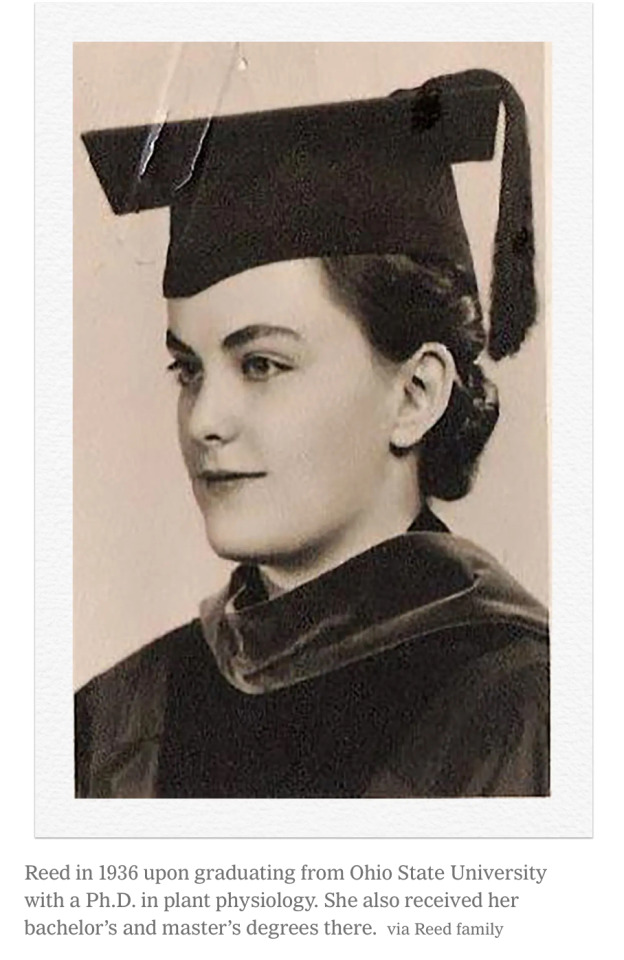

In 1933, Reed earned her bachelor’s degree at Ohio State University, where she also earned a master’s in 1934 and a Ph.D. in plant physiology in 1936. She put herself through school with a scholarship and by washing dishes and working in the cafeteria. In 1939 and 1940, she published her first two papers, one about the effects of insecticides on bean plants and the other about how various types of dusts affect the rate of water loss in yellow coleus plants by night and day.

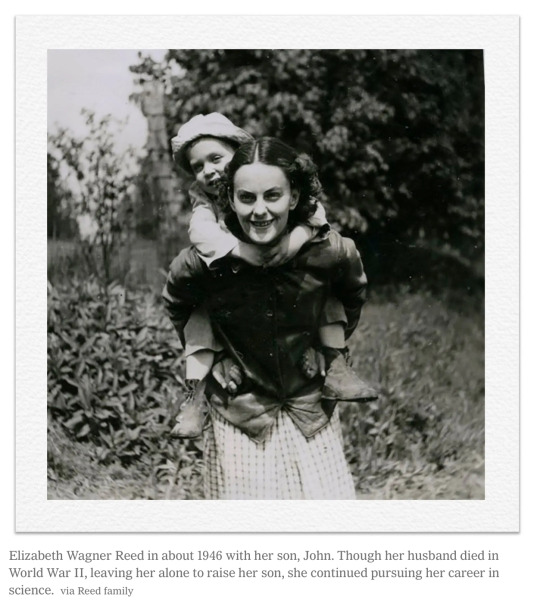

In 1940, she married a fellow scientist, James Otis Beasley, and had a son, John, with him just after James left to fight in World War II in 1942. When her husband was killed in the war the next year, she supported herself and her son by teaching at five different universities. “The first part of her life,” William Reed said, “was sheer determination.”

She began working with the geneticist Sheldon C. Reed, whom she married in 1946, and together they helped found the field of Drosophila population genetics, which uses fruit flies as a simple and economical method of studying genetics in a laboratory while offering important insights into similar species.

Soon after, the couple moved to Minnesota, where Sheldon was hired as the director of the Dight Institute of Human Genetics at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Elizabeth was denied a job at the university, which cited rules against nepotism.

The Reeds went on to write a book about intellectual disabilities that analyzed data from 80,000 people and their families; the study, they said, was “one of the largest genetic investigations so far completed.”

They found that disabilities could be caused by genetic or environmental factors and could therefore be heritable. They also proposed — to controversy that still exists today — that such disabilities were preventable through education of the general public and voluntary sterilization or birth control of potential parents with low I.Q.s.

Though Elizabeth’s name was listed first as author, a letter of acknowledgment calling the couple’s work “truly magnificent” referred to them as “Dr. and Mrs. Reed.”

Reed was quite aware that her husband was receiving more credit, her son William said, but she never let it embitter her. In 1950, however, she published a paper on sexism in the sciences based on her study of 70 women working in the field. It found that marriage and childbirth decreased their productivity and sometimes even dissuaded them from continuing their careers. It led her to mentor women in the field through the advocacy group Graduate Women in Science.

“She was a scientist before it was popular for women to become scientists,” Nancy Segal, a psychologist at California State University known for her study of twins, said in an interview, “and she was a great role model for so many of us women postdocs at the time.”

In writing “American Women in Science Before the Civil War,”Reed corresponded with archivists and scoured card catalogs, journals and proceedings of associations and societies. In addition to recognizing Eunice Foote’s work almost two decades before other scientists did, the book included biographies of, among others, the astronomer Maria Mitchell; Ellen Smith Tupper, who was known as the “Queen Bee of Iowa” for her study of that insect; and the entomologist Mary Townsend.

Reed wrote that it was a testimony to the strengths of these women that they pursued science despite the fact that they were “often denied entry to colleges and unable to attain professional status.”

Reed also supported teaching children about science so that they would have the tools to solve what she called the “current crises of exploding populations and deteriorating environments.” She published papers about teaching proper scientific methods in schools and created curriculums with the University of Minnesota.

“Classrooms always house some living organisms,” she wrote, tongue-in-cheek, in the Journal of the Minnesota Academy of Science in 1969. “In many, unfortunately, all are of a single species, Homo sapiens. The population consists of many immature species (children) and a few adults, usually female (teachers). This makes for a certain homogeneity, but it can be alleviated by introduction of other living species, animal or plant.”

The fact that Reed was, like so many of her predecessors, lost to history is indicative of the pervasive sexism of her era. But women today continue to face hurdles in entering scientific fields. A report from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology this year found that “the underrepresentation of women in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields continues to persist,” with women making up only 28 percent of the STEM work force.

Like Reed, her daughter, Catherine, was a scientist, having earned a Ph.D. in ecology, but she ultimately became so disillusioned that she held a ceremonial burning of her degree and instead turned to artwork and championing her mother’s legacy. She published her mother’s book on American women in science on her website in about 2010. She died in 2021 at 73.

Elizabeth Wagner Reed died at 83 on July 14, 1996, most likely of cancer. She recognized her symptoms, but, knowing what the treatments would be like and, to her mind, the probable outcome, she never sought a diagnosis. (Sheldon Reed died in 2003.)

William Reed said there was no joy like taking a walk with his mother, who could describe every plant and animal they passed. She and Sheldon were avid bird-watchers (and occasional polka dancers), and the family spent many vacations at Lake Itasca, Minn., relaxing under old-growth Norway Pines.

Reed’s favorite flower was the showy lady’s slipper, the state flower of Minnesota, an orchid notoriously difficult to cultivate, like the careers of many of the women she wrote about. Its Latin name is Cypripedium reginae, with reginae meaning queen.

#Elizabeth Wagner Reed#Women in science#American Women in Science Before the Civil War#Books for women#Eunice Newton Foote#Margaret Rossiter#Matilda Effect#Matilda Joslyn Gage#Woman as Inventor#Marta Velasco Martín#Graduate Women in Science#Maria Mitchell#Ellen Smith Tupper#Mary Townsend

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

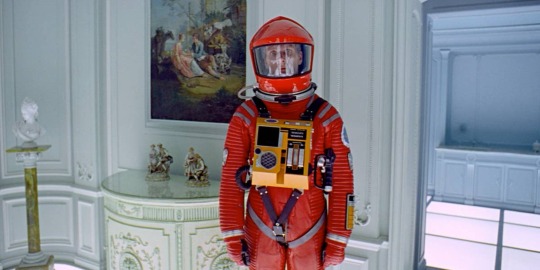

Keir Dullea in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968)

Cast: Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, William Sylvester, Daniel Richter, Leonard Rossiter, Margaret Tyzack, Robert Beatty, Sean Sullivan, Douglas Rain (voice). Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, based on a story by Clarke. Cinematography: Geoffrey Unsworth. Production design: Ernest Archer, Harry Lange, Anthony Masters. Film editing: Ray Lovejoy.

I know that I first saw 2001 on April 13, 1968, because (as a little Googling tells me) that was the date of the lunar eclipse I witnessed on leaving the theater, an appropriately cosmic climax to the cinematic experience I had just had. Kubrick's film was an experience to be savored by those of us who were already hip to the revolution in American filmmaking underway after the sensation of Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967) and The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967). I doubt that anyone who wasn't of an age to experience it realizes quite how revolutionary those movies seemed to us. Though it's conventional to say that our experiences were produced in part by controlled substances, anyone who really knows me knows that I wasn't under the influence of any substance stronger than beer. Today, 2001 doesn't seem much like a revolutionary film: We have lived through the actual 2001, which had its own epoch-making event in the September of that year, but in which no one was making trips to the moon on Pan Am. That airline went out of business in 1991, and the last real moon expedition, Apollo 17, took place in December 1972. But the future is never quite what it's cracked up to be. What was revolutionary about 2001 the movie is that it taught us how a movie can make us think without spelling out its ideas for us. Kubrick wisely whittled down the narrative given him by Arthur C. Clarke to a series of images, and ditched the score written by Alex North for an evocative set of snippets from classical works, letting us assemble any meaning to be derived from the film for ourselves. Of course, in 1968 we went back to our homes and dorm rooms and did just that. Seeing it today, I am most struck by how skillful Kubrick was in creating the persona of HAL, the sentient computer. Much credit goes, of course, to the voiceover work of Douglas Rain, but also to Kubrick's choice to make the dialogue of the humans in the movie as banal and jargon-filled as possible. HAL's final pleading and breakdown as Dave pulls his memory chips is haunting. Yes, the movie has its longueurs: Kubrick is deservedly proud of its landmark special effects and spends more time than is necessary showing them off. They won him the film's only Oscar, without honoring the work of Douglas Trumbull and others who executed them. He was also nominated as director and as co-screenwriter with Clarke, and the art direction team received a nod, but the film was passed over for the significant work of cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth, who was assisted by John Alcott, and for the sound crew headed by Winston Ryder. And it failed to receive a best picture nomination in the year when that award went to Oliver! (Carol Reed, 1968). I happen to like Oliver! and don't think it's necessarily one of the Academy's more shameful choices, but it's certainly not an epochal movie.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recent work has brought to light so many cases, historical and contemporary, of women scientists who have been ignored, denied credit or otherwise dropped from sight

that a sex-linked phenomenon seems to exist, as has been documented to be the case in other fields, such as medicine, art history and literary criticism.

Since this systematic bias in scientific information and recognition practices fits the second half of Matthew 13:12 in the Bible, which refers to the under-recognition accorded to those who have little to start with, it is suggested that sociologists of science and knowledge can add to the 'Matthew Effect', made famous by Robert K. Merton in 1968,

the 'Matilda Effect', named for the American suffragist and feminist critic Matilda J. Gage of New York, who in the late nineteenth century both experienced and articulated this phenomenon.

Calling attention to her and this age-old tendency may prod future scholars to include other such 'Matildas' and thus to write a better, because more comprehensive, history and sociology of science.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ProyeccionDeVida

📣 Kino Cat / Cine Tulipán, presenta:

🎬 “2001 UNA ODISEA DEL ESPACIO” [2001 A Space Odyssey]

🔎 Género: Ciencia Ficción / Aventura Espacial / Internet / Informática / Película de Culto

⌛️ Duración: 139 minutos

✍️ Guion: Stanley Kubrick y Arthur C. Clarke

📕 Libro: Arthur C. Clarke

🎼 Música: Richard Strauss, Johann Strauss, György Ligeti y Aram Khachaturyan

📷 Fotografía: Geoffrey Unsworth

🗯 Argumento: Diversos periodos de la historia de la humanidad, no sólo del pasado, sino también del futuro. Hace millones de años, antes de la aparición del "homo sapiens", unos primates descubren un monolito que los conduce a un estadio de inteligencia superior. Millones de años después, otro monolito, enterrado en una luna, despierta el interés de los científicos. Por último, durante una misión de la Nasa, Hal 9000, una máquina dotada de inteligencia artificial, se encarga de controlar todos los sistemas de una nave espacial tripulada.

👥 Reparto: Keir Dullea (David Bowman), Gary Lockwood (Frank Poole), William Sylvester (Heywood R. Floyd), Daniel Richter (Moon-Watcher), Douglas Rain (Hal 9000), Margaret Tyzack (Elena), Leonard Rossiter (Dr. Andrei Smyslov), Robert Beatty (Dr. Ralph Halvorsen), Bill Weston (Astronaut #1), Ann Gillis (Madre de Poole) y Edwina Carroll (Aries-1B Stewardess).

📢 Dirección: Stanley Kubrick

© Productoras: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) & Stanley Kubrick Production

🌎 Países: Reino Unido-Estados Unidos

📅 Año: 1968

📽 Proyección:

📆 Martes 02 de Julio

🕘 9:15pm.

🐈 El Gato Tulipán (Bajada de Baños 350 – Barranco)

🚶♀️🚶♂️ Ingreso libre

0 notes

Link

Tal día como hoy, en 1826, nace Matilda Joslyn Gage, sufragista estadounidense e historiadora de la ciencia. En 1993, se acuñó el conocido como efecto Matilda en su honor.

https://buff.ly/3FwlKhD

0 notes

Text

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) by theozonelab

Directed by Stanley Kubrick

Starring Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, William Sylvester, Leonard Rossiter, Robert Beatty, Sean Sullivan, Margaret Tyzack, & Douglas Rain

#2001: a space odyssey#1968#theozonelab#stanley kubrick#keir dullea#gary lockwood#william sylvester#leonard rossiter#robert beatty#sean sullivan#margaret tyzack#douglas rain#movie poster

24 notes

·

View notes

Video

undefined

tumblr

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

#2001 a space odyssey#stanley kubrick#keir dullea#gary lockwood#william sylvester#daniel richter#leonard rossiter#margaret tyzack#robert beatty#sean sullivan#douglas rain#frank miller#bill weston#ed bishop#glenn beck#alan gifford#ann gillis#edwina carroll#penny brahms#heather downham#mike lovell#john ashley#jimmy bell#david charkham#simon davis#jonathan daw#péter delmár#terry duggan#david fleetwood#danny grover

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Director - Stanley Kubrick, Cinematography - Geoffrey Unsworth

“I am putting myself to the fullest possible use, which is all I think that any conscious entity can ever hope to do.”

#scenesandscreens#2001: a space odyssey#Stanley Kubrick#arthur c. clarke#Keir Dullea#Gary Lockwood#William Sylvester#Daniel Richter#Leonard Rossiter#Margaret Tyzack#Robert Beatty#Sean Sullivan#Douglas Rain#Frank Miller#bill Weston#ed bishop#Glenn Beck

290 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TPS’S 25 ADDITIONAL FAVORITE MOVIES OF ALL TIME (2021 Edition)

3.) 2001: A Space Odyssey

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Cast: Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, William Sylvester, Daniel Richter, Leonard Rossiter, Margaret Tyzack, Robert Beatty, Sean Sullivan, Douglas Rain, Frank Miller

Best Moment: Rebirth ending

#favorite movies#2001: a space odyssey#stanley kubrick#keir dullea#gary lockwood#william sylvester#douglas rain#hal 2000#daniel richter#tps's favorite movies of all time

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 amazing women: introduction

Unfortunately, even in our modern society, there’s still an opinion that women are doing nothing important and are not able to benefit our world. At the moment, the success of women - with a huge number of talented women - is perceived as an exception, a kind of anomaly. Reasons? Of course, this’s a lack of knowledge, a still absent desire to understand that the history of women is an integral part of universal human history; and gender stereotypes, according to which men’re more inclined towards intellectual pursuits and not afraid to change the world around them.

The American historian Margaret Rossiter described one such stereotype about women scientists in 1993 and called it the Matilda Effect. The Matilda Effect is the systematic denial of women's contributions to science, belittling the value of their work, and attributing women's work to male colleagues. The Matilda Effect connects with the Matthew Effect, which was postulated by the sociologist Robert Merton. The Matthew effect is associated with an accumulated advantage: for example, famous scientists gain more credibility than an unknown researcher, even if their work is similar or if they worked together. Margaret Rossiter studied the reference work ‘American men of Science’ and came across five hundred biographies of women scientists. This number astonished her, and she decided to write a paper on women scientists in the United States before 1920, which she later published in the scientific journal AmSci (before that Science and SciAm had rejected the work).

The Matilda effect can be seen on many occasions throughout human history. And, in fact, this doesn’t only touch on to women scientists. We can also observe that it’s difficult for people to call to mind the names of women whose lives were dedicated to art, many don’t know those great women who forever changed our society, who handle global human problems. Women with a big heart and amazing intelligence...

Today is International Women's Day and I decided to compile some lists of gorgeous women whose names everyone should know. It was difficult because there’re too many names. For a long time I couldn’t choose who to write about, because all these women are magnificent. I also hope this’ll be inspiring for you.

(this list will be completed during a week)

also I plan to do a few more parts

1) 10 amazing women: activists

2) 10 amazing women: artists

3) 10 amazing women: directors/script-writers

4) 10 amazing women: philosophers

5) 10 amazing women: scientists

#10 amazing women#happy international women's day#international women's day#women scientists#women activists#women artists#women philosophers#international women's day 2021

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

► “Avec 863 hommes primés contre 52 femmes, l’attribution des Nobels est devenue au fil des ans une occasion rituelle de dénoncer l’effacement de la contribution féminine à l’avancée des sciences, au profit d’une postérité toute masculine.”

► “ Mais qui donc est Matilda ? Une figure oubliée, Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826 -1898), suffragette américaine, critique inlassable du patriarcat promu par la bible et auteure d’un court volume sur la contribution féminine dans l’histoire des technologies. Si Margaret Rossiter [à l’origine de la notion d’effet Matilda] l’a choisie, c’est donc « pour avoir la première exprimé (mais hélas, aussi, en avoir fait elle-même l’expérience) ce que nous pouvons appeler en sa mémoire “l’effet Matilda” », écrit l’historienne.”

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rosalind Franklin

Chimiste et biologiste moléculaire

1920-1958

Royaume-Uni

Nombre d’ouvrages indiquent encore qu’un trio de scientifiques masculins, Watson, Crick et Wilkins, aurait révélé la structure en double-hélice de l’ADN. La vérité est tout autre. C’est Rosalind Franklin qui produit les données décisives qui valent à ses pairs masculins le prix Nobel en 1962.

Rosalind Franklin intègre Cambridge en 1938. Aux dires de sa famille, elle est « d’une intelligence inquiétante pour une fille ». Parlant couramment le français et le latin, elle étudie la chimie durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, soutient sa thèse en 1945 et commence une carrière de chercheuse entre la France et l’Angleterre.

Au King’s College, elle travaille sur la chimie du charbon et du graphite, objet de sa thèse. C’est sous sa direction qu’est réalisé le célèbre « cliché 51 », une image de l’ADN produite par diffraction des rayons X qui montre une structure à double hélice. Par précaution, elle ne souhaite pas diffuser immédiatement ses résultats, et se contente de noter dans ses carnets la forme en hélice et les recherches à poursuivre.

Maurice Wilkins, l’un de ses collaborateurs du département, qui a accès à ses recherches, montre le cliché à deux autres scientifiques de Cambridge, James Watson et Francis Crick. Les données issues du travail de Rosalind Franklin apportent des éléments déterminants qui permettent de prouver les hypothèses des chercheurs. Elles sont alors utilisées à son insu et publiées. Des trois articles, parus en 1953 dans la revue Nature, qui discutent de la découverte, un seul est signé par Franklin.

Concentrée sur ses travaux ultérieurs et ses découvertes sur la structure des virus, elle ne réalise pas qu’elle a été spoliée. La scientifique meurt en 1958 d’un cancer des ovaires, à l’âge de 38 ans. Wilkins, Watson et Crick reçoivent le Nobel en 1962 pour la découverte de la structure de l’ADN.

Contre l’avis de Wilkins et Crick, Maurice Wilson publie La Double hélice, ouvrage dans lequel il brosse un portrait à charge de Rosalind Franklin. Il y minimise son apport et la dépeint en virago, en « sorcière », « perdante », incapable du génie scientifique que certains lui prêtent. L’argumentaire déclenche une polémique, c’est la correspondance de Franklin qui fait éclater la vérité.

Rosalind Franklin incarne depuis l’effet Matilda, théorisé par l’historienne Margaret Rossiter, qui décrit le phénomène récurrent de minimisation ou de déni qui caractérise les contributions des femmes à la science.

Photo : From the personal collection of Jenifer Glynn - Wikipédia creative common 4.0

1 note

·

View note

Photo

HAUDENOSAUNEE WOMEN’S INFLUENCE ON THE WOMEN’S RIGHTS MOVEMENT

While we celebrate the 100th anniversary of women gaining the right to vote in the United States, to celebrate the fact that women of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy have exercised political voice in this land for 1,000 years. These Indigenous women were the model for early suffragists like Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage. In the mid-1800s, women of the United States were considered “dead in the law” after they married, which meant they had no rights and were under the control of their husbands. They looked at their Indigenous sisters, with whom they had formed friendships, and saw another society, one in which women and men were equals. Women were able to choose their political representatives, while having responsibility for the economy, land, and spiritual ceremonies. This model became the impetus for American women to demand equality under the law and the right to vote.

To learn more about this amazing confluence of cultures and to celebrate the 100th anniversary of woman suffrage in 2020, join us as we honor our Haudenosaunee Sisters for their inspiration and guidance.

Gloria Steinem, writer, lecturer, political activist, and feminist organizer

Dr. Sally Roesch Wagner, Executive Director of the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation

Jeanne Shenandoah, Onondaga Nation Eel Clan Traditional Medicine Keeper

Gaeñ hia uh/Betty Lyons, Onondaga Nation, Snipe Clan, Executive Director of the American Indian Law Alliance

After the panel, we will present the first Annual Matilda Effect Project Award to the family of Audrey Shenandoah held the title of Deer Clanmother of the Onondaga Nation. Audrey has represented the Haudenosaunee Confederacy internationally as a writer, teacher, and adviser of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy to the United Nations.

The term “Matilda Effect” was created by scientist Margaret Rossiter to refer to women like Gage who are not recognized for their achievements and inventions. The Matilda Effect Project will design a database that will memorialize their important contributions in an effort to repopulate our history with intersectional women who, like Gage, have worked for social justice and peace by creating a database that will memorialize their important efforts.

The event is a fundraiser for the American Indian Law Alliance">American Indian Law Alliance and the Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation">Matilda Joslyn Gage Foundation and is co-sponsored by the American Indian Community House">American Indian Community House and the Ethical NYC">Ethical NYC. For TICKETS">TICKETS, please visit: matildaeffect.events">matildaeffect.events

Event Details

Date: March 9th, 2020

Time: 7-9PM

Place: Ethical NYC, 2 West 64th Street New York, NY 10023

Get Tickets.

.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Women Scientists Were Written Out of History. It's Margaret Rossiter's Lifelong Mission to Fix That

The historian has devoted her career to bringing to light the ingenious accomplishments of those who have been forgotten

from Science | Smithsonian https://ift.tt/309ug3t

via IFTTT

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forget About Jack, You Don’t Know Matilda (but you should)

A forceful advocate for women's rights in the 19th century, Matilda Joslyn Gage has been unfairly neglected by history, and her own writing helps to explain why.

Matilda Joslyn Gage, who wrote about how cumulative advantage (a principle not named until a century later) erased women and their achievements from history, was herself erased from history because of cumulative advantage. The reason why You Don’t Know Jack Matilda involves the Bible and science.

By Victoria Martínez

Matilda Joslyn Gage (1826-1898), Activist and Writer. (public domain image)

You…

View On WordPress

#abolition of slavery#Elizabeth Cady Stanton#feminism#Margaret Rossiter#Matilda Joslyn Gage#Principle of Cumulative Advantage#Robert K. Merton#Science#Susan B. Anthony#The Bible#The Gospel of Matthew#The Matilda Effect#The Matthew Effect#The Parable of the Talents#United States#Woman as an Inventor#Women in Science#Women Inventors#women writers#Women&039;s History#women&039;s rights#Women&039;s Suffrage

0 notes

Text

Interview of Nadezda Nikolova-Kratzer at Rfotofolio by Constance Rose.

Would you please tell us a little about yourself?

I am a photographic artist, living and working in Oakland, CA, with my husband and son.

Where did you get your photographic training?

I studied historic processes at the University of Kentucky and with Mark Osterman at the George Eastman Museum. I was also a member of the Lexington Camera Club, whose original members notably included Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Robert C. May, Van Deren Coke and other visionaries.

A gentleman, Wendell Decker, whose kindness I will never forget, showed me the ropes with wet plate collodion and helped me acquire equipment after which I embarked on a self-guided learning journey. Initially, I focused on making tintypes and ambrotypes but soon I began exploring the possibilities of using the process for camera-less work that walks the line between photography and painting.

Who has had an influence on your creative process?

I find inspiration in art that is stripped to its essentials such as Helen Frankenthaler’s color stained canvases, Agnes Martin’s understated meditations, Ellsworth Kelly’s chance studies, etc. Work that is contemplative, even spiritual, resonating beyond the thinking mind speaks to me.

Having a primary interest in non-traditional uses of photography, I look to artist who explore the materiality of the medium and are pushing its boundaries: Alison Rossiter, Ellen Carey, Gary Fabian Miller, Michael Flomen, Chuck Kelton, and others.

Please tell us about an image (not your own) that has stayed with you over time.

Of course, there are many and it is difficult to choose one, so I will stay with one of the above-mentioned artists, Alison Rossiter.

Art that is able to make a strong statement with limited means moves me. We can never approach the complexity of the world by attempting to recreate it, the best we can hope is to chisel away the inessential. The photogram is the most rudimentary photographic technology, using light, photosensitive surface, and objects that block the light, forming a silhouette. I appreciate the photogram’s simplicity, essentially, we are experiencing light and the absence of it, in a careful balancing act. I am interested in this dance between darkness and the light, control and surrender. I also find shadows as interesting as forms (if not more so), as they engage our imagination and connect with us on a more primal and non-intellectual level.

My latest series is inspired by Alison Rossiter’s sensual photograms on expired silver gelatin paper, some of which I was fortunate to see in person at SFMOMA. The balanced shapes and intriguing artifacts in Rossiter’s prints, resembling graphical work and paintings more than photographs, moved me to explore a similar direction using the wet plate collodion process.

What image of yours would you say taught you an important lesson?

Because my artistic practice requires treading uncharted territories, I could share mountains of “failed” photograms that taught me something new about the process or triggered new ideas.

What makes a good day for you creatively speaking?

The ability to have uninterrupted darkroom time and being fully present with the process regardless of the outcome.

If you could spend a day with any other photographer or artist living or passed who would it be?

Julia Margaret Cameron.

What equipment have you found essential in the making of your work?

I require very little in terms of equipment for my process – darkroom, chemistry, light, aluminum, paper and scissors, sink and water. I do not use enlargers but print directly by exposing objects over the sensitized collodion emulsion.

What hangs on your walls?

Our walls are crammed with artworks by contemporary artists working in historical processes. We also collect daguerreotypes, hand-painted tintypes, and other historic photographs.

What’s on the horizon?

The 2019 Photography Show by AIPAD with HackelBury Fine Art, London.

Thank you Nadezda.

8 notes

·

View notes