#Maurice Jaubert

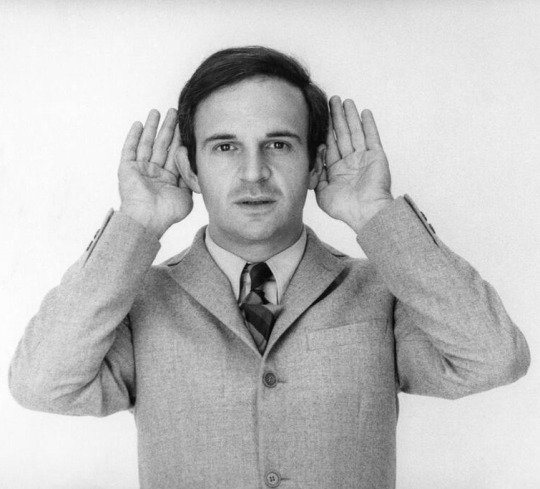

Photo

Long live rebellion!

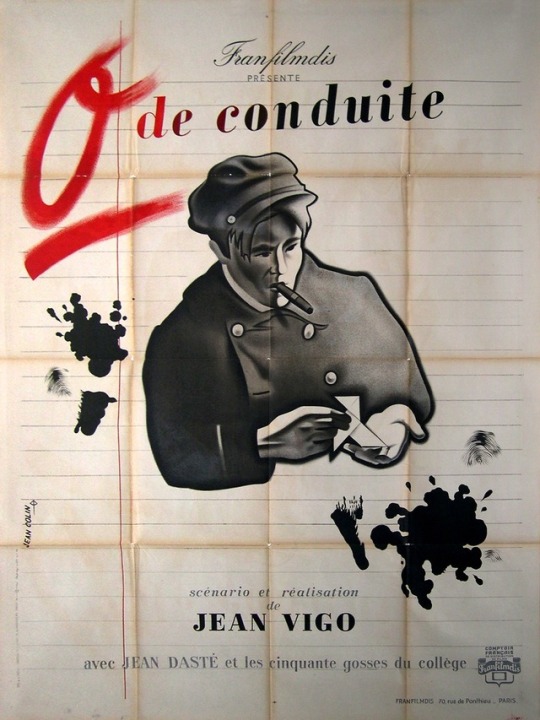

Zero for Conduct (Zéro de conduite), Jean Vigo (1933)

#Jean Vigo#Jean Dasté#Robert le Flon#Du Verron#Delphin#Léon Larive#Louis de Gonzague#Raphaël Diligent#Louis Lefebvre#Gilbert Pruchon#Constantin Goldstein Kehler#Gérard de Bédarieux#Boris Kaufman#Maurice Jaubert#1933

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music from the films of François Truffaut

· playlist

Jean Constantin, Georges Delerue, Bernard Herrmann, Antoine Duhamel, Maurice Jaubert, etc.

#François Truffaut#Film Music#georges delerue#bernard herrmann#antoine duhamel#Maurice Jaubert#Jean Constantin

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Bernard Blier and Arletty in Hõtel du Nord (Marcel Carné, 1938)

Cast: Arletty, Louis Jouvet, Annabella, Jean-Pierre Aumont, Jane Marken, André Brunot. René Bergeron, Paulette Dubost, François Périer, Andrex, Henri Bosc, Marcel André, Bernard Blier, Jacques Louvigny, Armand Lurville, Génia Vaury. Screenplay: Henri Jeanson, Jean Aurenche, based on a novel by Eugène Dabit. Cinematography: Louis Née, Armand Thirard. Production design: Alexandre Trauner. Film editing: Marthe Gottié, René Le Hénaff. Music: Maurice Jaubert.

Arletty's performance as the raucous streetwalker Raymonde in Hôtel du Nord is quite unlike her most famous role, the fascinating, enigmatic Garance in Marcel Carné's Children of Paradise (1945). Raymonde shares a room in the hotel with Edmond (Louis Jouvet), a photographer who is hiding out from his old cronies in the Parisian underworld. The film begins with a traveling shot along the canal that flanks the hotel, where we first see a young pair of lovers, Pierre (Jean-Pierre Aumont) and Renée (Annabella), walking arm in arm. Inside the hotel, the residents are celebrating the first communion of the daughter of Maltaverne (René Bergeron), a policeman who lives at the hotel. (It's a diverse household.) Pierre and Renée enter and request a room for the night, but instead of making love, they have decided on a suicide pact: He will shoot her, then kill himself. He holds up the first part of the bargain, but then chickens out. Edmond, who has been in his darkroom, hears the shot and breaks down the door, finding Renée apparently dead and Pierre cowering indecisively. Taking the gun from Pierre, Edmond urges him to flee. (The gun becomes a Chekhov's gun when Edmond first tosses it away and then recovers it and stashes it in a drawer.) Renée recovers from the gunshot, and Pierre, torn with guilt, turns himself in to the police as an attempted murderer and is sent to prison. After she recuperates, Renée returns to the hotel to collect her things, and is offered a job there by Madame Lecouvreur (Jane Marken), the wife of the proprietor (André Brunot). And so the story of the suicidal lovers begins to intertwine with that of Edmond and Raymonde. It's all neatly done, with a great deal of atmosphere (a word that Raymonde will give a particular spin to), much of it created by Alexandre Trauner's set, a re-creation in the studios at Billancourt of the actual hotel and the Canal St. Martin. The film's melodrama is alleviated by the ensemble work and the performances of Jouvet, who can switch from menacing to vulnerable in an instant, and Arletty, who makes the tough, worldly wise Raymonde often very funny. The film concludes with Carné's skillful staging of an elaborate Bastille Day sequence that anticipates the crowd scenes in Children of Paradise.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NEW SOUNDTRACK POST

L’Atalante (d. Jean VIgo, m. Maurice Jaubert)

rippingsoundtracks.blogspot.com/2020/03/maurice-jaubert-latalante-fr-vigo-1934.html

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maurice de Becque “Ariane” illustration from « La Grèce et la Sicile » by José Maria de Heredia 1926

#maurice de becque#1878-1938#maurice jaubert de becque#book illustration#french artist#José Maria de Heredia

464 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Raymond Bernard conceived of Les Misérables (1934)

Above image: Director Raymond Bernard, composer Arthur Honegger, and conductor Maurice Jaubert (who is the person between Bernard and Honegger? I’m afraid) Source: L’Image, January 1st 1933

On english wikipedia it says that the 1934 adaptation is one of the most well regarded adaptations. Is that true? I don’t know (haven’t seen it) but this article gives an interesting look into how the director approached adapting it. Also just the style of the journalist is kind of funny, like he sets out to talk to Bernard about one film and then just decides to change the topic of his interview to something that Bernard says he doesn’t want to talk about? But then he does talk about it at length? I like the part when he says that sometimes when reading Hugo it’s really boring for a couple of pages until you find something poetic.

I was a bit nervous going to see Raymond Bernard. One always has to “have an idea in advance,” to assign a neatly categorical human “type” to the person one is going to encounter, which is as rudimentary as an Epinal print [proverbially, naïve]: an actress is a capricious being, too pretty, snobbish, birdbrained, crying softly [?] … a writer, a writer is a serious and distant being, immobile behind a desk covered in papers, his finger to his temple, with a lost look. Finally, a director is a type of ogre, with a loud mouth and strong shoulders, always wearing shirt-sleeves, with a mean air, who will shoot importunate little people, like myself, with a terrible look!

Oh how untrue, how ridiculous all that is and how much more realistic it would be to say that one is going to see exceptional people, to be sure, but they are simply being themselves, they are simply welcoming…

That is how Raymond appeared to me. He did not appear (forgive me!) “with a loud mouth and strong shoulders” but smiling and slender, speaking with a soft, restrained voice…and modest, certainly very modest!

And here I was, proposing to speak to him about Les Croix de Bois [1932 film by Bernard set during WWI, featuring Gabriel Gabrio who was JvJ in LM1925], that tremendous film, the most complete, the most humane, the most beautiful film that has been made about that war, to tell him how much I had admired it, and more, how it had moved me.

“Do you want me to talk to you about Misérables?” Raymond Bernard asked me softly. “I don’t really know what I could tell you. For me, it’s finished, it’s in the past.”

After hearing that, how could I return to the subject of Les Croix de Bois? I didn’t dare, fearing vaguely that I would bore him.

“I’m listening all the same,” I said.

So he began to speak to me of German cinema. “It’s much less good than you would think. Most of the films that I was able to see there were extremely trite. What you can see here is the cream of the crop.” Then he moved on to Russian cinema, which he admires a lot and finally, to Hollywood.

“Would you like to go there and use their methods?”

“That would horrify me. Over there, I can see it, one is only worth how much money one can bring in…there is no more personality. It is abolished! Men, like Lubitsch, who succeeded in establishing themselves, you must think of the humiliations that they had to forcibly submit to, to the baseness they had to endure in order to ascend, little by little…that takes a special knack, independent of talent, which not everyone has. Over there, you are just a grain of sand…”

“Did you want to tell me about Misérables?”

“Les Misérables, that magnificent work with a magnificent title, was not, evidently, conceived of for the cinema. The first and very important problem was to give it a form which was in itself cinematographic, to make it into a “filmable” work before making it into a filmed work, in other words to give it a skeleton.”

But it’s too much. Raymond Bernard had said too much about himself, about his work. It was more than he could stand for. He threw himself into a glowing eulogy on Victor Hugo, who he admires even more now that he has studied him.

“And yet,” I sigh, “these days he is disdained.”

“That is because people don’t read him anymore! Writing for him did not exist, I dare to say. The words sprang forth from his brain…and with what power of imagery! I enjoyed myself in recreating the spark of the revolution of 1932, the way that he described it: there is a luxury of chaos, of color, of movement, overwhelming really! I compared his writing to that of a historian, de Blanc: it’s the same but his is grave, serious, finely painted, colorless…Hugo was a visionary, he wrote in abundance, an uncontrolled abundance… We often had to abandon, not without regret important pieces…what Andre Lang and myself called ‘the parenthesis.’”

“Take, for example, the history of the sewers of Paris! A prodigious documentation of the sewers as they were in the last century. Myself, I do not even know how they are now! And well, Hugo, he really knew them at his time! Likewise, on the subject of the convent de Picpus, he gives us the complete history of convents in France! What a man! How did he do it to write, to write still more, and to amass such a sum of readings, of documents! It’s almost unbelievable, and yet, see, I was thinking of adapting l’Homme Que Rit…I was astounded to see the extent of his knowledge about the navy!”

“A giant, he was a giant…and yet, the poet never disappeared. It is deeply moving to fall, sometimes after a few pages which are a bit boring, on a few lines of authentic poetry…” Raymond Bernard is dreaming, searching for words. “No, it’s more than that…how can I say it? Poetic, lyrical inspiration… In the film, it was a question of not forgetting the side of poetic inspiration…”

While he is speaking, I look at him. His young face is creased, his gaze, which is very soft, wanders ceaselessly, the gaze of a dreamer, a seeker. And he smiles often, very often, like when he tells me: “Everything that I was telling you there, what can that do for you? It has no great importance!” He even apologizes for being talkative and I, I am thrilled to listen to him!

“To make a film,” he continues, “there are two methods: to be or not to be faithful to the text. Me, I think that in the very interest of the author, you must be unfaithful. You shouldn't be afraid of slipping away in order to re-establish the core idea…Besides, we have to limit ourselves to time.”

“We adopted a structure of three films. The first film we gave the title of the first chapter of Misérables: A storm beneath a skull, which summarizes well enough the spirit of the work.”

“Yes, yes the principal problem is that of pruning (how do you not prune a work that is so bushy?) then you must recast the novel in this mold…that is what is most complicated: to create the skeleton, the framework, to make the work suffer in order to restore it finally to the spectator, with more fidelity than if we had held vulgarly to the text word for word. To do it world for word, what a treason! Look at that literal adaptation of Hamlet by Marcel Schwob, presented in the French of the 16th century, that was shown at the Comédie-Française! What a mistake that was! Don’t you think that with the simple words of today one can give a more precise and faithful translation of the text? Myself, I am entirely in favor of a great reworking of the text, especially when you want it on the screen. After that it remains to you to find a ‘cinematographic writing’ that serves the author in the most faithful manner.”

“Explain yourself…”

“Just as words and phrases are adapted. Almost unconsciously, to the era that they are trying to paint, in the same way you must create a ‘style of image.’ You can’t photograph scenes with the same life as there was in 1830, as you are photographing scenes from the present day. All this must be studying, created…with Victor Hugo this is relatively easy. He was such a visionary! He is a collaborator who will not let you fall! Even his dialog has a simplicity, a truthfulness! We don’t realize it enough!”

“There is even in this work a humorous side that is absolutely remarkable! Some of his characters are created so picturesquely, with an allure that is almost caricature, incredible!”

“Once you find it, create (without ostentation as much as possible evidently, since that is the enemy of goodness!) the “cinematographic expression,’ that is how the battle begins: the manuscript is finished, but the film is untouched! You must make the film! Now you must be stubborn, head strong…persuasive…”

[...]

He also told me about the extras, the electricians, the makeup technicians, who are true artists, he exclaims, who sometimes have a hundred times more talent than the stars who are idolized, because they have never become conscious of their value, remaining simple and sincere in exercising their artistry.

I am going to take my leave.

“Would you mind,” I supplicate, “giving me a photo, for the readers of Image magazine?”

Raymond Bernard puts his hand on his chin: “Well it’s just that I don’t have a photo,” he admits to me. “And also, the readers of Image have seen it so often that they must be tired of it!”

A director who doesn’t have a photo of himself on his person? What do you think?

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It’s the first day of 2021, which calls (yet again!) for my ten favorite new-to-me movies I watched in 2020!

The rules are the same as always: no movies from this past year (2020) or the year before (2019). Every other year is free game.

All ten of these movies are fascinating and beautiful and well worth your time, so consider this a strong endorsement for all of them. I’ve also included ways to watch all of the films (as of this writing, Jan. 1, 2021).

01. Two for the Road (dir. Stanley Donen, 1967; USA)

Donen takes the ideas of romantic cinema and celebrates it while injecting a healthy dose of painful reality. He chooses two of the English language's most attractive movie stars, Albert Finney (in full himbo mode!) and Audrey Hepburn, and follows their ten-year marriage as seen on their various road trips across Europe. It's a memory piece more than anything else, but the arc of their relationship is clear and their palpable connection burns through the screen. These are two beautiful, intelligent adults who love each other deeply, who are still physically attracted to each other, who are able to hurl verbal jabs and insults at each other with the best of them. Finney is magnificent, but Hepburn sort of steals the show. In what is probably her finest onscreen performance, she gets to grow from a virginal bride to a fully fleshed out adult, living beautifully in different shades of sexy and goofy and bitter. They make a screen couple for the ages. The script is funny without losing its honesty, it's tragic without leaning too far into artifice, it's romantic without being treacly. It's a remarkable balancing act and makes for a masterpiece. (Two for the Road is available to rent online or viewed at this link.)

02. Stop Making Sense (dir. Jonathan Demme, 1984; USA)

Stop Making Sense feels like a miracle. It hints at a narrative arc, but that part is unimportant. It’s a live performance recorded and packaged specifically for consumption as a film. In its brief runtime, it becomes a living, breathing, sweating testament to David Byrne’s skill as a performer, as a songwriter, as a storyteller, and to the remarkable talents of everyone in Talking Heads. It’s a breathtakingly joyous experience. I can’t remember the last time I watched a recording of a live performance that captured the same brand of energy, of buoyancy, that you feel as you’re leaving a great communal experience. This is a masterpiece that proclaims as loudly as possible that there is no joy greater than making art with people you love. (Stop Making Sense is currently streaming on Amazon Prime.)

03. Scattered Clouds (dir. Mikio Naruse, 1967; Japan)

Filled to the brim with unspoken turmoil and emotional devastation, Naruse's final film chronicles the rough terrain of a relationship between a widow and the man responsible for her husband's death. Spanning years and exploring just how deeply these wounds can go, much of the Scattered Cloud’s success rests on the performances from Yuzo Kayama and Yoko Tsukasa. Kayama is a handsome, likable screen presence who beautifully lives in his own cloud of grief. Tsukasa gets a bit more to chew on, as this really is her story: her arc and her inability to move forward, despite the best intentions, is one of the film's most lasting ideas. Brutally sad but incredibly beautiful. The work of a master filmmaker. (Scattered Clouds is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.)

04. L’Atalante (dir. Jean Vigo, 1934; France)

My only regret with L’Atalante is that I didn’t see it sooner. The final (and only feature-length) film from Jean Vigo before his untimely death at 29, this film is a technical marvel and a humanist miracle. Featuring spirited performances from Dita Parlo, Jean Dasté, and the great character actor Michel Simon, and intoxicating dreamlike imagery, as well as a relentlessly romantic score from Maurice Jaubert, this film looks and feels like no other film from its era. (L’Atalante is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.)

05. Daisies (dir. Věra Chytilová, 1966; Czechoslovakia)

Věra Chytilová's iconic masterpiece of anarchic cinema more than lives up to its reputation. Operating on its own chaotic wavelength, Daisies follows the exploits of Marie I (Jitka Cerhová) and Marie II (Ivana Karbanová) who seek to spoil themselves after realizing how spoiled the world is. They begin to live extravagantly and rip off older men and cause general mischief. Over less than 80 minutes, Daisies upends a whole slew of cultural norms. Beautiful, ambiguous, funny, cynical, and truly visionary. (Daisies is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel and HBO Max.)

06. The Hero (dir. Satyajit Ray, 1966; India)

The Hero sort of feels like Satyajit Ray's answer to 8½ in its meditation of fame and regret. Uttam Kumar is fantastic as Arindam Mukherjee, a superstar actor who works through his career and his loss of values in an interview with a reporter played by Sharmila Tagore, who is also fantastic. Under Ray's sleek direction, gracefully opening up the world of the train, and with his intelligent and human script, the cast uniformly sinks their teeth into this film. Kumar is the MVP out of necessity -- without him, the whole film would fall apart -- but the whole ensemble is remarkable, peppering the background of the train scenes and in Arindam's flashbacks. This also has one of the all-time great nightmare sequences. Easily one of the master director’s best films. (The Hero is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.)

07. Malcolm X (dir. Spike Lee, 1992; USA)

Malcolm X is a truly massive film housing an even bigger performance from the great Denzel Washington. Tracing Malcolm X’s life and career while juggling numerous tones and visual styles and spanning across decades and continents, this is surely Spike Lee’s most ambitious film up to this point in his career. Washington is onscreen for virtually all of its long runtime, from the early exuberant days before his imprisonment all the way up to that fateful day in the Audubon Ballroom, and he is, of course, tremendous. All that classic Denzel charisma and magnetism is on full display, whether in his impassioned speeches or in his more intimate scenes. Lee’s direction is top notch, making this full story about a life with an incalculably profound impact feel richly and deeply intimate. This is one of the essential American epics. (Malcolm X is available to rent online.)

08. Beau Travail (dir. Claire Denis, 1999; France)

Beau Travail’s place in the modern canon of world cinema is assured, and Denis is rightfully seen as a master, but it really can’t be overstated just how much of a gem this film is. Pepper with sparse dialogue (though always packed with meaning), the film lives in one of two modes: muscular, suntanned men doing slow, precise choreographed exercises in the heat of the day and those same muscular men dancing and gyrating with attractive young women in some ethereal nightclub. Between these poles lies Denis’ almost cosmic meditation on masculine ego, homoerotic obsession, and regret. A fascinating, enigmatic, devastating beauty. (Beau Travail is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.)

09. Only Angels Have Wings (dir. Howard Hawks, 1939; USA)

Only Angels Have Wings might be Howard Hawks' crowning directorial achievement. The aerial work, the rainy nights, the beautiful atmosphere of the bars, the palpable camaraderie of the characters, the tragic loss of life and yet the persistence to move forward. Cary Grant leads a terrific cast, including a quietly moving Richard Barthelmess and a rarely-more-likable Thomas Mitchell, and his chemistry with both Jean Arthur (the most charming) and Rita Hayworth is a joy to watch. This film seems to dabble in multiple genres at once, subverting the cliches of the Hollywood formula while still embracing the melodrama and the artifice within. In that way, the film feels very strange, but if the viewer lets themselves be carried along with Hawks' unique rhythm, the reward is one of the most fascinating and exciting films in Hollywood's fabled 1939 output. (Only Angels Have Wings is available to rent online or viewed at this link.)

10. Closely Watched Trains (dir. Jiří Menzel, 1966; Czechoslovakia)

Between the precise composition of the shots and the young narrator-protagonist, Closely Watched Trains feels like a spiritual predecessor to Wes Anderson's work. This comparison extends to the thematic content of the film as well, as the story of a young man coming-of-age against the backdrop of the Nazi regime is definitely cut from the same cloth as The Grand Budapest Hotel. Lucky for me, I love Anderson's work, and Grand Budapest is my favorite of his, so Menzel's stylistic flourishes immediately endeared me to the film.Menzel maintains a skillful tonal balancing act throughout Closely Watched Trains. Even under the wry, almost self-deprecating humor, the film never loses track of preciousness of life and the horrific tragedy of war. Beautiful cinematography, strong performances across the board, a memorable score, and a clever script make this a gem of the Czech New Wave and a moving, delightful, and accessible coming-of-age tale. (Closely Watched Trains is currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.)

Honorable mentions (in alphabetical order): Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951), The Band’s Visit (Eran Kolirin, 2007), But I’m a Cheerleader (Jamie Babbit, 1999), Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962), A Cottage on Dartmoor (Anthony Asquith, 1929), Crossing Delancey (Joan Micklin Silver, 1988), Divorce Italian Style (Pietro Germi, 1961); Eat Drink Man Woman (Ang Lee, 1994), Fireworks (Kenneth Anger, 1947), The Freshman (Fred C. Newmeyer & Sam Taylor, 1925), The Hitch-Hiker (Ida Lupino, 1953), Kuroneko (Kaneto Shindo, 1968), Le Bonheur (Agnès Varda, 1965), Le Notti Bianche (Luchino Visconti, 1957), Like Father, Like Son (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2013), Local Hero (Bill Forsyth, 1983), Love & Basketball (Gina Prince-Bythewood, 2000), Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (George Miller, 1981), Monsoon Wedding (Mira Nair, 2001), One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (Agnès Varda, 1977), Pennies from Heaven (Herbert Ross, 1981), Pickup on South Street (Samuel Fuller, 1953), Rushmore (Wes Anderson, 1998), Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa, 1954), Sleepless in Seattle (Nora Ephron, 1993), Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (William Greaves, 1968), Tea and Sympathy (Vincente Minnelli, 1956), They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (Sydney Pollack, 1969), Tomboy (Céline Sciamma, 2011), Wendy & Lucy (Kelly Reichardt, 2008), Within Our Gates (Oscar Micheaux, 1920), Whisper of the Heart (Yoshifumi Kondo, 1995), and Who Framed Roger Rabbit (Robert Zemeckis, 1988).

And some miscellaneous viewing stats:

First movie watched in 2020: A Fantastic Woman (Sebastián Lelio, 2017)

Final movie watched in 2020: Holiday (George Cukor, 1938)

Worst movie watched: The Notebook (Nick Cassavetes, 2004)

Oldest movie watched: Ten films by the Lumière Brothers (Louis Lumière, 1895)

Longest movie watched: Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa, 1954; 207 minutes)

Month with most amount of movies watched: December (58 movies, including shorts)

Month with least amount of movies watched: February (11 movies) (pre-COVID, naturally)

First movie from 2020 seen: Birds of Prey (Cathy Yan, 2020)

Total movies watched: 455

#sometimes elliott watches movies#year in review#two for the road#stop making sense#scattered clouds#l'atalante#daisies#the hero#malcolm x#beau travail#only angels have wings#closely watched trains

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

La vita del cineasta Jean Vigo fu breve, nasce a Parigi il 26 aprile 1905 e muore a ottobre del 1934. Egli realizzò soltanto quattro film la cui durata complessiva non raggiunge le tre ore. Ma L'Atalante e Zéro de conduite [Zero in condotta] sono dei film notevoli per la loro poesia ed il loro spirito di rivolta.

26 Aprile 1905: Jean Vigo

Non è possibile parlare di Jean Vigo senza evocare la vita di suo padre Miguel Almereyda. La sua morte drammatica nel 1917 avrebbe profondamente segnato Jean Vigo. Nato nel 1883, si reca a Parigi all'età di quindici anni ed esercita il mestiere di fotografo e conosce presto la prigione. Sarà condannato per furto poi per fabbricazione di esplosivi e per diversi reati di stampa.

Nel 1903 Almereyda aveva incontrato una militante, Emily Cléro. Il loro figlio detto Nono, nasce nel 1905. I suoi genitori vivevano in una miseria nera. Per sopravvivere, hanno anche stampato denaro falso. Queste condizioni di vita difficili avranno probabilmente delle conseguenze sulla salute di Jean.

Dopo aver partecipato al Congresso antimilitarista di Amsterdam, Almereyda crea nel 1906 il giornale La Guerre Sociale con Gustave Hervé, socialista rivoluzionario. Crea anche le Jeunes gardes révolutionnaires [Le Giovani guardie rivoluzionarie] che si battono contro i realisti ma anche con gli individualisti del giornale L'Anarchie. A poco a poco si allontana dalle idee libertarie. Da pacifista, diventerà militarista rivoluzionario poi semplicemente militarista. Nel 1913, crea il giornale Le Bonnet rouge [Il Berretto rosso] che nel 1914 sostiene l'entrata in guerra della Francia.

La Guerre Sociale poi Il Bonnet rouge avevano conosciuto un enorme successo. Così, il tenore di vita di Almereyda era completamente cambiato: automobili, residenze, amanti... Nel 1917, constatando i guasti della guerra, cambia direzione, ritrova delle posizioni pacifiste e sostiene la Rivoluzione russa. La destra e l'estrema destra vogliono la sua pelle. Un affare di assegno di origine straniera serve da pretesto per il suo arresto. Il 13 agosto 1917, è ritrovato morto nella sua cella. Non si sa ancora se si tratta di un crimine o di un incidente

Per tutta la sua vita, Jean Vigo rimarrà segnato dall'amore e dal culto che dedica a suo padre. Non avrà sfortunatamente il tempo di ottenere la sua riabilitazione.

A dodici anni, Jean Vigo è accolto da Gabriel Aubès, suocero di Miguel Almeyreda. Conosce anni molto difficili: è già colpito dalla tubercolosi, è privo di padre, è allontanato da sua madre che si disinteressa di lui e si ritrova internato . Il suo soggiorno al collège de Millau dal 1918 al 1922 gli ispirerà la maggior parte delle scene di Zéro en conduite [Zero in condotta]. Dal 1922 al 1925, è al liceo di Chartres dove ottiene il diploma. Mentre sta seguendo delle cure mediche a Font-Romeu, incontra Lydou (Elysabeth Losinska), figlia di un industriale polacco. Risiedono successivamente a Nizza.

Jean Vigo sa che vuole diventare cineasta. Grazie al padre di Lydou, può comprare una macchina da ripresa. Incontra Boris Kaufman. Nato nel 1906, quest'ultimo sarà (non si è sicuri della cosa) il fratello del realizzatore sovietico Dziga Vertov (1895-1924), pioniere del cinema documentario, creatore del cinema verità. Dalla fine del 1929 a marzo 1930, Vigo e Kaufman percorreranno le vie di Nizza allo scopo di realizzare il loro primo film A propos de Nice [A proposito di Nizza].

Jean vigo ha detto di A propos de Nice che si trattava di "un punto di vista documentato" e non di un documentario. È influenzato dalle teorie di Vertov. Questo film è uno sguardo satirico sul mondo fortunato dei vacanzieri estivi. Nizza è una città che vive del gioco. Vigo ci mostra i grand Hotel, le straniere, la roulette, tutto un mondo che contrasta con i quartieri poveri. Si tratta di una violenta critica sociale.

Il suo primo film è stimato positivamente, Jean Vigo può affrontare la sua carriera di cineasta con ottimismo. Nel 1930 a Nizza, crea il ciné-club Les amis du cinéma. Gli aderenti poterono scoprire tra l'altro dei film sovietici. Nel 1931 realizza un film su ordinazione di undici minuti sul campione di nuoto Jean Taris. Questo film è soprattutto notevole per le prese di vista sottomarine che Vigo riutilizzerà in L'Atalante. Lo stesso anno Jean e Lydou hanno una figlia, Luce. Nel 1932 incontra a Parigi Jacques-Louis Nounez. È un uomo d'affari che ama il cinema, si sente vicino a Vigo ed accetta di essere il suo produttore.

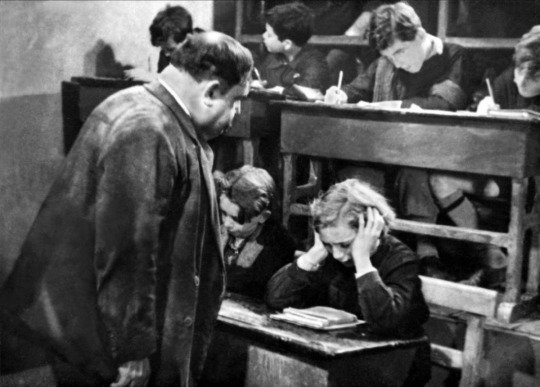

Tra dicembre 1932 e gennaio 1933, Vigo gira Zero in condotta. Il direttore della fotografia è Boris Kaufman, la musica è di Maurice Jaubert- È un'opera autobiografica poiché il film mette in scena dei bambini all'interno di un collegio- La disciplina è così severa che i bambini preparano una cospirazione. L'allievo Tabard dice merda al professor Mielleux che gli accarezzava la mano. Convocato presso il preside, esortato a dare una spiegazione, non ha che una risposta: "Signor professore, vi dico merda!". Questa risposta è ispirata da un titolo di La Guerre sociale indirizzata al governo da Almereyda: "Vi dico merda!". Più tardi, la rivolta scoppia nel dormitorio. Le penne volano, il sorvegliante è legato al suo letto. Il giorno seguente è giorno di festa al collegio. Gli ufficiali invitati (prefetto, prete, militare) ricevono ogni genere di proiettili da parte dei bambini saliti sul tetto. Il disordine è generale, la bandiera con il teschio è issata, i bambini fuggono dai tetti poi in campagna.

Zero in condotta fu criticato dal potere. Le proteste furono numerose, soprattutto quelle dei padri di famiglia organizzati. Per essi, il film elogiava l'indisciplina e costituiva una attentato al prestigio del corpo insegnante. Dopo una proiezione unica, il film è vietato dalla censura ed i cinefili dovranno attendere il 1945 per vederlo. Vigo aveva preso le parti dei bambini che rappresentavano l'immaginazione e la creatività contro gli adulti, borghesi ipocriti e cattivi. Questo film non è tuttavia manicheo perché i bambini non sono tutti dei santi: possono essere anche falsi e perversi. Zero in condotta ha una profonda sensibilità libertaria. Di fronte alle difficoltà alla libertà ed alla felicità, la rivolta è necessaria. Jean Vigo rappresenta i sostegni del potere che sono lo Stato, la Chiesa e l'esercito sotto forma di marionette che bisogna abbattere in un gran gioco al massacro.

Malgrado la censura, Jacques-Louis Nounez ha sempre fiducia in Jean Vigo ed è pronto a produrre un nuovo film. Vigo ha diversi progetti. Uno di questi Evadé du bagne [Evaso dai lavori forzati] ci interessa particolarmente. Si tratta dell'adattamento della vita di Eugéne Dieudonné. Quest'ultimo era un illegale legato ai membri della Banda Bonnot. Alla fine dell'anno 1911, Bonnot ed i suoi compagni avevano aggredito a Parigi un cassiere della Società generale per rubargli 20.000 franchi in banconote e 5.000 franchi in oro. Delle retate hanno luogo negli ambienti anarchici. Dieudonné, operaio carpentiere di 27 anni, è arrestato; il cassiere afferma di riconoscerlo benché egli assicuri che al momento dei fatti, si trovasse a Nancy. Benché scagionato da Bonnot prima della sua morte, con una lettera di Garnier e le dichiarazioni di Raymond la Science al processo, Dieudonné è condannato a morte. Sarà graziato ma spedito ai bagni penali in Guyana.

Eugène Dieudonné tenterà per due volte di evadere ma sarà ripreso ogni volta. Il terzo tentativo avrà successo. Dopo aver sfiorato molte volte la morte, giunge in Brasile. È minacciato di estradizione. Il celebre giornalista Albert Londres assume la sua difesa ed ottiene la grazia. Dieudonné rientra in Francia dove riprende il suo mestiere di ebanista. Durante il suo processo nel 1912, Almereyda lo aveva sostenuto. Jean Vigo conosceva bene Dieudonné che aveva fabbricato i mobili del suo appartamento. Lo incarica di abbozzare un primo adattamento cinematografico seguendo i testi di Albert Londres. Dieudonné aveva accettato di svolgere il proprio ruolo e Vigo aveva prospettato di girare il film nella stessa Guyana. Benché molto avanzato, questo progetto fu abbandonato perché i rischi di censura erano molto alti, i rischi finanziari anche. Nell'agosto del 1933, Nounez affida a Vigo un nuovo progetto. La censura non potrà intervenire e Vigo potrà effettuare un'opera personale. Questo film, L'Atalante sarà il capolavoro di Vigo ma anche il suo ultimo film.

L'Atalante fu girato dal novembre 1933 a gennaio 1934. La sceneggiatura originale di Jean Guinée è stato rimaneggiato in profondità da Jean Vigo e Albert Riéra. Boris Kaufman è sempre il direttore della fotografia. La coreografia di Francis Jourdain che fu amico di Almereyda. Il montaggio di Louis Chavance di orientamento libertario. Questo film beneficia di più mezzi dei precedenti. Ha una vera distribuzione: Michel Simon, Dita Parlo, Jean Dasté...

Un marinaio sposa una giovane contadina che si ambienta male in una chiatta dove regna un vecchio originale (Michel Simon). Quando la chiatta giunge alla periferia di Parigi, la donna lascia suo marito. Entrambi sono disperati ma si ritrovano e si amano di nuovo. Vigo ha trasformato un soggetto di un'estrema banalità in una poesia d'amore pazzo in cui la critica sociale non è assente. Sin dall'inizio, durante le nozze soltanto gli sposati sembrano simpatici; il resto degli assistenti è ridicolo e si tiene a distanza, ostile. Jean Vigo affronta i problemi sociali del suo tempo. mostra la campagna in via di industrializzazione (piloni, terreni devastati), file di disoccupati, i conflitti tra il marinaio ed il suo padrone, il linciaggio da parte della folla di un presunto ladro. La cambusa di Michel Simon è un vero deposito di cianfrusaglie surrealista: vi si vedono delle mani tagliate in un boccale, degli automi, un vecchio fonografo che meraviglia la giovane sposa. Lo sguardo che porta Vigo sulla coppia non è moralista; c'è incomprensione tra gli sposati e se la moglie fugge, è perché vuole fuggire al grigiore della vita quotidiana. Il marinaio deve tuffarsi in fondo all'acqua per ritrovare il volto della sua beneamata.

La critica riserverà una buona accoglienza a L'Atalante. Sfortunatamente la Gaumont, temendo la censura e non trovando il film abbastanza commerciale, lo fece uscire in una forma mutilata. Delle scene sparirono (Michel Simon faceva fumare la donna tatuata sulla sua pancia), un canzonetta (Le chaland qui passe) fu sostituita alla musica di Jaubert. Non è che dopo molti anni che si poté vedere una versione più conforme al lavoro di Vigo. La sua carriera cinematografica si arresterà lì perché muore nell'ottobre del 1934, sua moglie Lydou morirà cinque anni dopo.

Jean Vigo è stato segnato dalla sua infanzia mal vissuta ed il ricordo ossessivo di un padre assassinato. Sarà in rivolta contro una società opprimente. Continuerà a frequentare gli amici del padre: Francis Jourdain, Fernand Desprès, Victor Méric, Jeanne Humbert. Molti di loro, entusiasti della Rivoluzione russa, hanno raggiunto le fila del Partito comunista. Jean Vigo non vi aderirà perché è un sostenitore di un'unione di tutte le forze di sinistra. Nel 1932 prende parte alle attività di tutte le forme dell'AEAR (Association des écrivains et artistes révolutionnaires).

Ogni anno il Premio Jean Vigo premia l'autore "di un film che si caratterizza per l'indipendenza del suo spirito e la qualità della sua realizzazione". I film di Jean Vigo hanno influenzato molti cineasti francesi. Per concludere, lasciamo la parola a François Truffaut : "Ho avuto la fortuna di scoprire i film di Jean Vigo in una sola seduta, un sabato pomeriggio del 1946, al Sèvres-Pathé, grazie al Ciné-club della camera nera animato da André Bazin... Ignoravo entrando in sala persino il nome di Jean Vigo ma fui preso presto da un'ammirazione sterminata per quest'opera la cui totalità non raggiunge i 200 minuti di proiezione".

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Zéro de conduite (1932)

by Jean Vigo

Comédie dramatique

45 mn - France

youtube

0 notes

Text

Le Jour Se Leve (Daybreak)

Le Jour Se Leve (Daybreak)

BBBB (out of 5) A shot is heard, a man stumbles out an apartment door and falls dead down a flight of stairs; the neighbours are upset, the police arrive and pretty soon the building is surrounded while the man we presume is the killer (Jean Gabin) holes up in his room and recalls the days that led to the crime. We flash back to when he first encounters a beautiful young woman and falls madly in…

View On WordPress

#Albert Viguier#Alexandre Trauner#Andre Bac#Arletty#Arthur Devère#Bernard Blier#Boris Bilinsky#Gabrielle Fontan#Germaine Lix#Jacqueline Laurent#Jacques Baumer#Jacques Prevert#Jacques Viot#Jean Gabin#Jean-Pierre Frogerais#Jules Berry#Mady Berry#Marcel Carne#Marcel Pérès#Maurice Jaubert#Philippe Agostini#René Bergeron#René Génin#Rene Le Haneff

0 notes

Photo

L´Atalante / La chalana , 1934

Director: Jean Vigo

Fotografía: Boris Kaufman

Música: Maurice Jaubert

Como todo buen melodrama, L´Atalante apela mucho a las emociones. Se genera una conexión muy fuerte con el personaje de Dita Parlo, que es un personaje inocente, tierno y amoroso. Creo que Jean Vigo puede lograr conmover tanto mis sentimientos, porque los conoce. Habla a través de sí mismo y le da una dimensión muy profunda a los personajes. Las relaciones humanas son complejas y Vigo lo sabe,

La película habla mucho de los roles masculino / femenino, y los desafía. Ella es una mujer libre, curiosa, quiere conocer, quiere vivir, quiere amar y ser amada, aunque siempre es muy femenina, y asume los roles de la época, el personaje de su esposo, no está cómodo la mayoría del tiempo, no le gusta que ella conviva con otros hombres, la mantiene un poco encerrada.

Encuentro ecos entre Dita en L´Atalante y Giuletta Massina en algunos papeles de Felinni. Aunque Giuletta en La Strada o en las noches de Cabiria, es un personaje mucho más trágico y melancólico. Existe una ternura y felicidad mezclada con tristeza en ambas.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dita Parlo and Jean Dasté in L'Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934)

Cast: Dita Parlo, Jean Dasté, Michel Simon, Gilles Margaritis, Louis Lefebvre, Maurice Gilles, Raphaël Diligent. Screenplay: Jean Guinet, Albert Riéra, Jean Vigo. Cinematography: Boris Kaufman. Art direction: Francis Jourdan. Film editing: Louis Chavance. Music: Maurice Jaubert.

L'Atalante is one of those near-universally acclaimed film masterpieces that failed theatrically on their first release and were rediscovered and re-evaluated more than a decade later. But it's also one of those films that young contemporary movie lovers may not "get" on first viewing today. I remember my own reaction to films like The Rules of the Game (Jean Renoir, 1939) and L'Avventura (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960), movies that didn't fit what I expected from being raised on energetic, plot-driven, star-centered American movies. Melancholy and irony are not widely praised American values, although lord knows we have plenty of it in the best American literature. They surfaced for a time in the best American films of the 1970s, but have been driven back into the underground by the blockbuster mentality. There was a time, even after the great cinematic awakening of the '70s when I found myself resenting film critics for their inability to appreciate popular movies I liked: "Critics see too many movies to enjoy them," I sniffed. But the truth is, the more movies you see, the more you're able to appreciate those that don't walk the line, that don't instantly gratify the hunger for plot resolution, for spectacle, for something that sends you out of the theater blissfully untroubled by thought. L'Atalante confused and bored its contemporary viewers, but today those of us who love it do so because it seems to us alternately tender and brutal, simultaneously comic and touching, and, taken as a whole, one of the few movies that successfully transport us to a time and place and a company of human beings we have never found ourselves in the middle of before. It is also, despite years of mishandling and cutting and botched attempts at restoration, one of the most technically dazzling films ever made. The performances -- by Michel Simon as the rather gross Père Jules, Dita Parlo and Jean Dasté as the young couple trying to start married life on a cramped river barge, and Gilles Margaritis as the madcap peddler who almost wrecks their marriage -- are extraordinary. Cinematographer Boris Kaufman overcame the severe limitations of filming scenes in the cramped quarters below-decks as well as open-air scenes for which the weather refused to cooperate. Vigo and Kaufman stage visual compositions that have a freshness that never seems arty. And who can ever forget Simon's Père Jules clambering aboard the barge with a kitten on his shoulders? Every corner of L'Atalante is filled with life.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“ Des jours heureux il ne reste trace

Tout est couleur de la nuit

Mais à vingt ans l'avenir efface

Le passé quand l'espoir luit... “

~ René Clair - musique Maurice Jaubert / À Paris dans chaque faubourg

0 notes

Photo

Maurice de Becque, etching illustration from Six poèmes barbares by (Charles Marie René) Leconte de Lisle, 1925.

#maurice jaubert de becque#1878-1938#maurice de becque#book illustration#leconte de lisle#french artist

424 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mystic River – Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante

Jean Vigo was the first poet of modern cinema, its doomed genius and abiding spirit, an anarchist dreamer dead at twenty-nine with just one full-length film to his name. But what a film, a poetic-realist masterpiece that still resonates today. Whereas even the great directors of the silent era had an emotional range not much above dime-store romances and morality plays, Vigo brought a modern indifference to absolutes and types, a dreamer's knowledge of inner states, a realist's understanding for complexity and a romantic's eye for industrial landscapes and country girls. And he did all this with just one film, L'Atalante.

It’s a film that refuses to pander to the kind of romantic narrative being perfected the same year by Frank Capra. In his It Happened One Night a pretty heiress on the run meets a tough-guy reporter and they bicker all the way to a happy ending. In fairness, it's a great film, but it ends where real life takes over, before the question can be asked. How could they live together after the adventure of their 'meet cute' has ended? L'Atalante begins there; the happy couple, Jean (Jean Dasté) and Juliette (Dita Parlo) marching through the village on their wedding day. It's the kind of procession that would end a Jane Austen adaptation. But it's part of this film's emotional realism to want to explore the difficulties of maintaining love after the initial flush of romance.

The courtship has obviously been swift. This girl trapped in a small village dreaming of escape meets a handsome barge captain. It's surely part of the attraction for her, the excitement of escape. They leave on a trip to Paris, part work-related, part makeshift honeymoon. But soon barge life starts to bore her and resentment grows towards her husband for being too possessive and jealous, focused on work, leaving her on the prow of the barge in her dressing gown, alone and brooding. And then there’s the unsettling presence of cat-loving old seadog Pere Jules (Michel Simon), fascinating and frightening her with his tattoos and tales of far-off places, his Aladdin’s Cave cabin with its whale bones and music boxes, its oriental fans and switch-blades (not to mention the pair of decapitated hands kept in a jar).

So it's not surprising her head is turned by dreams of big city life when she meets a travelling salesman, an anarchic, sweet-talking charmer who tries to persuade her to come to Paris with him. And so the couple are separated. She runs off to see Paris, dream city of glamorous fashions and automated window displays. Upset by this betrayal Jean immediately sets sail for Le Havre, leaving her behind. She quickly learns, however, that the Paris of magazines and radio broadcasts is only an illusion for those without money. She wanders through a city hit hard by recession, full of closed factory gates, sneak-thieves and sexual predators. Meanwhile he’s a broken man, catatonic with loss, searching for signs of watery hope.

Cue happy ending right? Well, yes, but the film’s integrity and naturalness means we believe in this couple completely. What follows isn’t a contrived plot twist but one of the most truly romantic sequences in all of cinema, a reverie of yearning, two lost souls realising the depth of their feelings for each other, bodies aching with a loss so deep it leaves reality behind, becomes a sexual dream, a cinematic embrace. It's a happy ending in the truest sense, one of those rare films that provoke genuine feeling, a river journey that casts a timeless spell, with water as a symbol of poetic vision and the search for love, full of the shyness and yearning of desire, the sound of barge engines and fog-bells, natural light and coal smoke, every minute of it suffused with poetry and love and a freshness that won’t ever fade.

It’s an enduring testament to Boris Kaufmann's inventive and lyrical photography, Maurice Jaubert's unforgettable score, Dita Parlo's shy smile and Michel Simon's uncanny transformative powers. But most of all to Vigo's poetic vision, his outsider’s courage. He died of tuberculosis soon after making this, the original DNA of European cinema, as if its perfection left him with nowhere else to go. And while what he might have done had he lived will tantalise us forever, L'Atalante is enough. It's a complete world unto itself, a philosophy, a cinematic journey, a way of life.

1 note

·

View note

Text

L’Atalante

1934, Jean Vigo

En el último largometraje de Jean Vigo, uno vuelve a quedar cautivado ante el lirismo y simpleza con el que se representa la vida cotidiana de un sector social: los habitantes de barcos en los canales franceses.

En esta película, Vigo articula poemas con el lenguaje cinematográfico y la propuesta fotográfica. Esto lo podemos ver con la entrada y salida del barco en el plano, generando la sensación de que la cámara danza con la corriente del río; con picados y contrapicados que logran separar a los personajes en cubierta de fondos planos, ya sea del mar o del cielo; con objetos excéntricos que llenan el espacio del camarote y generan una sensación de encierro; con emplazamientos que procuran trazar en el encuadre las figuras tanto de personajes como de fragmentos del barco, buscando equilibrio y geometría.

Por otra parte, el sonido también juega un papel esencial en la lírica de esta película. El leimotiv de Maurice Jaubert, que oscila entre fuentes diegéticas y extradiegéticas, no solo funciona para transmitir la nostalgia, sino que también genera una sutil atmósfera onírica que permite acompañar las secuencias surrealistas. Además, la música también funciona como recurso narrativo para desencadenar la resolución del conflicto de la historia.

A pesar de tener leves aproximaciones a clichés americanos, L’Atalante es una obra sublime que nos traslada a un espacio y un tiempo distinto, pero inherente a la naturaleza humana.

0 notes