#Mythological Intertext

Note

i waiting for heat 2 confirmed with adam and oscar

As thrilled as I would be to see Oscar Isaac in the role of Vincent Hanna, I think he's engaged with other projects that conflict with the general timetable. Adam Driver is clearly Mann's top choice for Neil McCauley and I would put money on Austin Butler for Chris Shiherlis at this point.

I am desperately curious as to who is on Mann's list of potential candidates for Vincent Hanna. Heat faced off two legendary New Hollywood icons with complementary careers, at that point both securely “canonized” and in middle age, and so the narrative functions at that postmodern, meta-mythological level. Adam Driver’s connotative figuration in the industry thus makes him an ideal choice for the role of Neil, and I personally would guess this is a much more important criterion for Mann himself than any sort of immediate visual resemblance to De Niro (which I’ve seen some people gripe about on Twitter). That is, the most important quality for any actor who is going to play Neil – secondary only to competence, to be sure – is his ability to embody a certain respected, authoritative presence that resounds between text and intertext.

My theory is that the role of Vincent will go one of two ways. Option 1: Mann has an analogous up-and-coming “Pacino Presence” in mind, and wants a leading man with the right cultural credentials to continue the symbolic subtext put forth by the original story (Oscar Isaac would fit beautifully here, I admit).

Option 2: He will go with a “nobody” (or a “relative nobody,” like a working actor known primarily for his TV or stage roles), thereby advancing the subversive relationship the novel has with the film. To the extent that Heat 2 invites a kind of Fishian operation on the text vis-à-vis Paradise Lost/Surprised By Sin, Vincent very easily transforms into a metaphorical stand-in for us, the audience members, the reader-detectives charged with (re-)interpreting meaning and authorial intention by way of perceptual clues left at the cinematic crime scene. The book explicitly introduces this possibility in a way that the film does not, so it would be interesting to see if he goes with it. With that in mind, as I’ve mentioned before, I hope he’s got somebody like Michael Zegen in the running...

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thomas Harrison on Herodotus, Homer and the character of the gods (VI)

"Finally, some brief remarks on ‘primordial religion’. If Homer and Hesiod first created a theogony, and gave to the gods their eponyms, their honours, skills, and forms, what did they have before that point? Scullion suggests reasonably that this ‘leaves a remainder we might identify as their essential, existent personalities, but it is difficult to see what this remainder might consist of, unless a sort of disembodied ethos.’ 46 Some kind of picture can be pieced together, however, with the help of pre-Socratic intertexts, accounts such as those of Prodicus, Democritus, and the Platonic Protagoras, as well as his own text. What one can discern is an evolutionary model in which an inchoate sense of the divine is gradually fleshed out with a more detailed recognition of the gods 47 and with the paraphernalia of worship. At 2.4.2, the Egyptians are credited with being the first to introduce altars, and images (ἀγάλµατα) and temples. Implicitly, then, there is a previous stage of development—one of which we can still gain glimpses in contemporary foreign contexts—before any people possessed such things. The Pelasgians of 2.52 strikingly appreciate the plurality of the gods; they then obtain a basic level of confirmation of the names of the gods they receive from abroad from Dodona. 48 Homer and Hesiod fill out that picture: with a mythological narrative, eponyms (leading to the specificity of cult), worked-out characterisations or forms, and the honours they receive. ‘The gods’, according to another fragment of Xenophanes, ‘have not indicated all things to mortals from the beginning. But in time, by searching, they find something more that is better’ (οὔτοι ἀπ’ ἀρχῆς πάντα θεοὶ θνητοῖσ’ ὑπέδειξαν, ἀλλὰ χρόνῳ ζητοῦντες ἐφευρίσκουσιν ἄµεινον). 49 We are all, like the Pelasgians, fumbling in the dark. And so we hold on to whatever points of reference we can find. Do as if.

46 Scullion (2006) 200.

47 Cf. 2.145–6 where Herodotus concludes that the Greeks dated the origin of Pan and Dionysus to the time at which they first gained knowledge of these gods. I attempt to flesh out Herodotus’ picture of the earliest human development in Harrison (forthcoming).

48 I will not explore here the vexed issue of the meaning of the gods’ names, discussed, e.g., by Harrison (2000) 251–64; Thomas (2000) 275–81; Roubeckas (2019) 134; Pirenne- Delforge (2020) 75–7.

49 Xenophanes D 53 L–M = 21 B 18 D–K, from Stob. 1.8.2; 3.29.41.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bayard, L. (2007) Comment parler des livres que l’on n’a pas lus? (Paris).

Burkert, W. (1985) Greek Religion (Cambridge, Mass. and London).

Currie, B. (2020) ‘The Birth of Literary Criticism (Herodotus 2.116–17) and the Roots of Homeric Neoanalysis’, in R. Zelnick-Abramovitz and J. J. Price, edd., Text and Intertext in Greek Epic and Drama: Essays in Honor of Margalit Finkelberg (London) 147–70.

Derow, P. S. (1994) ‘Historical Explanation: Polybius and his Predecessors’, in S. Hornblower, ed., Greek Historiography (Oxford) 72–90.

Fowler, R. (2010) ‘Gods in Early Greek Historiography’, in J. N. Bremmer and A. Erskine, edd., The Gods of Ancient Greece: Identities and Transformations (Edinburgh) 318–34.

François, G. (1957) Le Polytheisme et l’emploi au singulier des mots ΘΕΟΣ, ∆ΑΙΜΩΝ (Paris).

Gaifman, M. (2012) Aniconism in Greek Antiquity (Oxford).

Gould, J. (1994) ‘Herodotus and Religion’, in S. Hornblower, ed., Greek Historiography (Oxford) 91–106.

Graham, D. W. (2018) ‘Review of Laks–Most (2016)’, CW 111: 433–9.

Harrison, T. (2000) Divinity and History: The Religion of Herodotus (Oxford).

—— (forthcoming) ‘Herodotus on the Evolution of Human Society’, in Truschnegg, et al. (forthcoming).

Hornblower, S. (2005) A Commentary on Thucydides Volume II: Books IV–V.24 (Oxford)

Hussey, E. (unpubl.) ‘The Religious Opinions of Herodotus’.

Irwin, E. (forthcoming) ‘The Histories in Context: some Reflections on Publication, Reception, and Interpretation’, in Truschnegg, et al. (forthcoming).

de Jong, I. (2012) ‘The Helen Logos and Herodotus’ Fingerprint’ in M. de Bakker and E. Baragwanath, edd., Myth, Truth and Narrative in Herodotus (Oxford) 127–42.

Lateiner, D. (1989) The Historical Method of Herodotus (Toronto).

Laks, A. and G. W. Most, edd. (2016) Early Greek Philosophy, 9 vols (Cambridge, Mass. and London).

Lloyd, A. B. (1975–88) Herodotus, Book II, 3 vols (Leiden).

Mourelatos, A. P. D. (2018) ‘Review of Laks–Most (2016)’, BMCR 15 March 2018, https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2018/2018.03.15 (last accessed 26 Jan. 2021).

Munson, R.V. (2001) Telling Wonders: Ethnographic and Political Discourse in the Work of Herodotus (Ann Arbor).

Pirenne-Delforge, V. (2020) Le Polythéisme grec à l’épreuve d’Hérodote (Paris).

Raaflaub, K. A. (2002) ‘Herodotus and the Intellectual Trends of his Time’, in E. Bakker, I. de Jong, and H. van Wees, edd., Brill’s Companion to Herodotus (Leiden) 149–86.

Racine, F. (2016) ‘Herodotus’ Reception in Latin Literature from Cicero to the 12th century’, in J. Priestley and V. Zali, edd., Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Herodotus in Antiquity and Beyond (Leiden) 193–212.

Roubeckas, N. P. (2019) ‘Theorizing about (which?) Origins: Herodotus on the Gods’, in id., ed., Theorizing ‘Religion’ in Antiquity (Sheffield) 129–49.

Rudhardt, J. (1992a) Notions fondamentales de la pensée religieuse et actes constitutifs du culte dans la Grèce classique 2 (Paris).

—— (1992b) ‘Les attitudes des Grecs à l’égard des religions étrangères’, Revue de l’histoire des religions 209: 219–38; Eng. transl. by A. Nevill, ‘The Greek Attitude to Foreign Religions’, in T. Harrison, ed., Greeks and Barbarians (Edinburgh, 2002) 172–85.

Schwab, A. (2020) Fremde Religion in Herodots “Historien”: religiöse Mehrdimensionalität bei Persern und Ägypten (Stuttgart).

Scullion, S. (2006) ‘Herodotus and Greek Religion’, in C. Dewald and J. Marincola, edd., Cambridge Companion to Herodotus (Cambridge) 192–208.

Sourvinou-Inwood, C. (2000) ‘What is Polis Religion?’, in R. Buxton, ed., Oxford Readings in Greek Religion (Oxford) 13–37; orig. in O. Murray and S. Price, edd., The Greek City from Homer to Alexander (Oxford, 1990) 295–322.

—— (2003) ‘Herodotus (and Others) on Pelasgians’, in P. Derow and R. Parker, edd., Herodotus and his World: Essays from a Conference in Memory of George Forrest (Oxford) 147–88.

Thomas, R. (2000) Herodotus in Context: Ethnography, Science and the Art of Persuasion (Cambridge).

Tor, S. (2017) Mortal and Divine in Early Greek Epistemology (Cambridge).

Truschnegg, B., R. Rollinger, J. Degen, H. Klinkott, and K. Ruffing, edd. (forthcoming) Herodotus’ World (Wiesbaden).

Versnel, H. S. (2011) Coping with the Gods: Wayward Readings in Greek Theology (Leiden).

Whitmarsh, T. (2015) Battling the Gods: Atheism in the Ancient World (London)."

Thomas Harrison "Herodotus, Homer, and the Character of the Gods", in Ivan Matijasic (editor) Herodotus-The most Homeric Historian?, Histos Supplement 14, 2022.

Professor Thomas Harrison is Keeper of the Department of Greece and Rome at the British Museum, and an Associate Fellow of the Institute of Classical Studies.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Meiri, I hope you have been well!!!

I'm way late asking this but I wanted to wait until I finished ASEFSW to ask:

Did you have any favorites parts and or any authors notes or details that didn't make it in?

I confess that my favorite thing about your fics where Farkhad makes an appearance is the way you describe him and his manner of speaking

TEEHEE THANK YOOOOUUU THEY'RE EASILY one of my favorite parts too..... i had such a blast writing him using early modern english in TA&AT even if it was taxing to have to drop everything and search for conjugations... we did its(sic). his fics are only truly the one i can/feel the narrative drive to go Balls To It with the intertext elements... for he is [his]story... for he is nothing but it... [his]story alive through word...

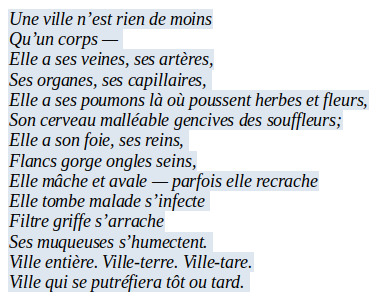

and funnily[?] enough there is not much in ASEFSW's draft that didn't make it into the finish story... in fact there is a lot that was Not In The Draft that i added. the story was supposed to be. way shorter. or at least i imagined it way shorter. had told myself it'd be less than 10k and Well. we've seen how it went. this happens to me everytime. there is One thing that was in the draft that didn't make it, & it's a french part:

that would have made it 2 french poetry parts in the whole text, but i did not find a satisfactory place to put it so... scraped. goodbybye. a shame because i did really like "Ville entière / Ville-terre / Ville-tare . [...] tôt ou tard" liked it.

as for my fave parts in it... hard to tell because i did have such a great time writing ASEFSW so much fun... i really do like the very first paragraph/the intro i think it sets the tone just right...

in general i loved putting the myths/mythologies in the text such as in here...

LOVED WRITING THE HOUSE GET WEIRDER WITH IT(self)...

loooooved writing the whole opiumpainting transformation scene. it was important to me that it happened to them. i'm really happy with how it turned out.

loved this...

hehe :3

loved the gay male house

hence why i wrote it really.

loved the evil house

hence why i wrote it really. :3

THANK YOU AGAIN... HAPPY TO HEAR YOU WIKED MY FARKHAD... i wike him too. consistently writing him get his skull bashed in. but he's fine. so. c'est de bonne guerre.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

7/29 - 8/6/2023

I started last weekend really excited about writing Renji 2, and had a good time with that. And then proceeded to have no writing time past last weekend. =_= I just need to chill out and accept that life is going to be about driving and People and racecars and the Women's World Cup rn and not about my blorbos and stories. Not that I don't also like the aforementioned but also MY BLORBOS AND STORIES THO. ):

As excited as I am about this chapter I'm still not sure if it ~works because Renji is just infodumping about 79 different things, and the part I wrote was about written vs. actually-followed easement policy in West Rukongai and how long it takes to run places. Which on one hand, Renji Why, but on the other, Why Not, Renji.

Something I have done a lot of this week, though, is driving—more in the last 7 days than in the last 7 months, to be specific—and I got reacquainted with my nemesis, audiobooks. I still don’t think I actually like audiobooks, but all of the books I listened to were very enjoyable in spite of the format, and I recommend all of them! This is especially exciting because these choices were guided by "what is currently available at the library."

The week’s roadtrip audiobook selections:

H is for Hawk, Helen MacDonald (2014)

Psalm for the Wild-Built, Becky Chambers (2021)

Orange World, Karen Russell (2019)

The Nickel Boys, Colson Whitehead (2019)

H is for Hawk, Helen MacDonald (2014)

I’ve been wanting to read this book for a long time, but I’m glad I didn’t get a chance to until now, because coming off of condor!Tobiume this book was especially exciting. I didn’t realize until listening that it drew so heavily on The Once and Future King (and TH White’s biography in general) as intertext, which has really made me want to re-read that book, since I haven’t read it since the summer after I graduated high school. H is for Hawk is a falconry memoir, and it is quite a bit about birds—the goshawk Mabel in particular—which I figured would be a good time, from a creative nonfiction, ecology writing POV, two genres I generally like. But oh my god it is so much better than I already thought it was going to be! MacDonald has such strong analysis of masculinist, neoliberal cultures past and present, and the kinds of mythologies falconry comes from with regard to class and gender (and sexuality, re: TH White), and her own parsing of these things as she grows up. I want to read this book again.

Psalm for the Wild-Built, Becky Chambers (2021)

I am OBSESSED with this book and I keep recommending it to everyone I see. It’s about a tea monk on a future moon where, in the distant past, robots developed to work in human factories gained sapience and left the human places to go live freely and separate in the wilds. Yearning for something missing from their life, the tea monk sets off into the wilds and encounters a robot who has been sent out to check in on the humans, and to answer the question, “What do humans need?” I don’t know that I am usually a robot person—but I am a traveling tea monk person haha—but I love these robots so, so much. They name themselves for the first things they see, so they all have plant/animal names. They hyperfixate on watching stalagmites grow, for centuries. This book is so soft and thoughtful and incredibly thought-provoking. It’s about a future that doesn’t rely on post-apocalypse; nothing overtly dramatic happens but everything is gripping.

Orange World, Karen Russell (2019)

This is collection of short stories—I was able to pay attention to some far more than others, but Russell had the most interesting prose for me. There were lines where I was like, man, I wish I were reading this so I could copy this down.” Really strong sense of region and place in each story, and the world building (as one might hope of a book titled Orange World) is superb. I was familiar with Russell conceptually but hadn’t read anything by her before. My favorites were the story about Plains State/Midwestern storm farmers, who captured, husbanded, and rented out storms of various stripes—and now their industry was being affected by climate change. And the story about four sisters who are gondoliers, and use echolocation (of a sort) to navigate the span of a short story.

WIP-wise, I guess LOL I’d love to write as beautifully as Karen Russell does!! But more seriously I guess it’s about being bold about the mechanics of a world and how much it is possible to accomplish even in the span of a short story.

The Nickel Boys, Colson Whitehead (2019)

I’m only halfway through this one, but it’s historical fiction about a reform school in the South during Brown v Board of Education, and the false promises experienced while attempting to integrate the South.

As far as where this could be WIP research, Whitehead does a great job of minor timeskips across the parts of the novel, including skips of actually writing out major precipitating events, which makes me feel more embolden about how I’ve structured some of this WIP.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

~Irene, The Baker St. Venus~

I wanted to post this, a long time ago, but one of the main fandom friends that I used to talk to about the inter-weaving of Myths and Astrology in BBC Sherlock left ( I miss you @longsnowmoon5!), so I shelved it. Previously, I toyed with the idea of Mycroft as Saturn. That was fun. In A Scandal In Belgravia, Aphrodite Venus, the Empress Tarot, herself, is reincarnated as Irene, who really lived up to the myth, not only coming between Sherlock and John, but also being a strong catalyst for attempting to bring their romantic relationship to the surface. Venus, the planetary body, representative of Love, is known by certain motifs: I will go through them here.

"What are you going to wear?" asks Kate. "My Battle Dress." answers Irene. "Lucky Boy!" Irene then ask for a lip color in the shade of Blood.

Venus was known to always be ready for battle, and besides usually being unabashedly nude, she is represented by the color Red, for Passion. But Red was also the ancient color for War.

The Tarot card for Aphrodite/Venus, called The Empress, describes her sitting on a luxurious seat, with cushions, in a wooded area, next to a stream, and sometimes a waterfall, which shows her abundance, and connection to the earth:

Here is Irene, on her throne, with cushions, in the woods, next to a stream, and I believe a small waterfall, in the background.

"The astrological symbol for the planet Venus—named for the Roman’s goddess of love, Venus, who was often identified with the Greek Aphrodite—is the same symbol as that used for the biological female: a circle with a small cross beneath (as seen in the above tarot card, on her shield) In alchemy, the Venus symbol also stands for the metal copper, and this provides an interesting link between copper, females and mirrors – in antiquity, polished copper or bronze was used in mirrors. The Venus symbol is also thought to represent the very mirror of Venus or Aphrodite: therefore the connection between Aphrodite and mirrors becomes ever more pronounced...Further symbolism of the mirror shows a connection to secrets...and, as such, to the intense, secret-shattering aspects of light." (At last count, there were at least 5-6 mirrors in Irene's bedroom).

So, let's see here. What secret is Irene hiding behind her Shield Mirror? That's right: Her Heart Phone. "The shield is a paradox...the paradox is that where there is love there is instant protection, yet to love also requires our vulnerabilities." X

Also, don't forget Sherlock's words, before attempting to figure out the safe code: "I really hope you don't have a baby in here."

The Empress tarot is often shown as pregnant, symbolizing that "the situation is pregnant with promise! ( Read Sonnet 59 meta, where Sherlock makes John a promise) - full of opportunity. Along with the symbolism of pregnancy holding promise, comes the waiting period. Just as there is an incubation time until the child comes forth, so too is there a time of waiting until our desires become manifest." So we wait. As Sherlock says, that's what targets do.

"(All) of this links back to the planet Venus, which in Ancient Greece was ruled by two gods, one of which was named Eôsphoros (bringer of dawn) or Phôsphoros (bringer of light); identifying Aphrodite’s sacred planet, Venus, as a bringer of light...The mirror also, in turn, symbolises revelation and truth: the mirror often shows the face, and the eyes, as shown in the painting Venus At Her Mirror by Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velazquez, in which the goddess gazes into the mirror with only her face revealed."

Here, her hair is even similar to Irene's, as are the color found in Irene's home; Red, Black, and White.

"The eyes, in turn, are the paths to truth: they are the “window to the soul”, or, ever-more interestingly, the “mirror of the soul.” Aphrodite, in gazing into the mirror, is therefore not merely enjoying the sight of her own beauty, but is acknowledging the truth of all that resides within her..." X

As our story's mirror to Irene, Sherlock appears to go looking for his own truth. If the popular LSIT theory holds true, that The Hiker & the Backfire are indeed about John's failed Romantic getaway with Sarah, it would seem that Sherlock is again, solving multiple mysteries, rolled into one.

The cherry for me in this tale, came from the excellent Art meta by @sagestreet cleopatras-leg-the-sexy-tapestries-in-asib,

"...we get a depiction of the Goddess Aphrodite (Venus) standing behind the couple, her hand outstretched above their heads in benediction. Yes, the Goddess of Love is literally blessing (!) the two lovers just as they’re turning their faces towards each other, about to kiss, absorbed in whatever this little sex game of theirs is.;)"

(OMG...these two. And it HAD to happen within close proximity to Venus.)

But to continue, we get this other bit from Sage's meta: "At the height of the feast, Plutarch tells us, Cleopatra made an entrance dressed as the Goddess Aphrodite, the Goddess of Love." So, in a fun bit of the writers' affinity for inverting, they had Aphrodite Irene, take and dress in Cleopatra Sherlock's clothes....

...here, as she brandishes a phallic symbol, her scepter whip, another Empress motif. She did this, not just once...

...but twice. Irene brought Truth into John and Sherlock's relationship, never swaying from her purpose, even as she played her game of War.

And why not? Venus is known in Ancient times as being the Patron Saint of Homosexual Love between men. Sappho's poetry holds her also as a Saint for Lesbians. X Aphrodite Ourania, the celestial Aphrodite, born from the sea foam after Cronus castrated Uranus...also inspired homosexual male desire or, more specifically, ephebic eros." X "In one context, she is a goddess of prostitutes; in another, she turns the hearts of men and women from sexual vice to virtue." X This could be the possible reason for her chosen profession in Sherlock. She inspires, tempers, and balances, seduces, but more importantly, communicates openly, with her own heart. She knows quite well, the secret wishes made by the hearts of Man. Well...she knows what they like.

Venus Rising by Sandro Botticelli

Meta inspired, as usual, by a little talk with my friends X . Also, by Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C.S. Lewis by Michael Ward, in which he theorizes that the children in Narnia were each given the personalities of the Seven Ancient Astrological bodies. This book is spotted behind John's chair, in A Study In Pink. The 7th chronical is titled The Final Battle.

@ebaeschnbliah @darlingtonsubstitution @gosherlocked @love-in-mind-palace @loveismyrevolution @kajaono @let-bijohns-be-bi-johns @rominatrix @theragesniff @rinkagaminesstuff @johnnytik @sagestreet @monikakrasnorada @delurkingdetective @221bloodnun @impossibleleaf @tjlcisthenewsexy @devoursjohnlock @roadswewalk @marta-bee @may-shepard @fleurdelisandbees @madzither

#Irene Adler#Aphrodite#Venus#Myth#Astrology#Mythological Intertext#Love#Passion#War#Sappho#Motifs#a scandal in belgravia#C.S. Lewis#Michael Ward#Narnia

58 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry for the dumb question, but should I prioritize Greek texts or Roman texts? Like, when it comes to stories and everything that Romans took from the Greeks, is the Greek version of X myth, for example, the one I should be reading? I've been seriously considering learning either Latin or Ancient Greek, so this is going to be the deciding factor. Thanks!

not a dumb question, but not an easy one to answer either! i don't think there's a right answer to this or one you "should be reading" or would be better off prioritizing.

i'd like to take a moment to poke at your framing: the thought that the romans "took from the greeks" is widespread, but while it's not entirely inaccurate, it's not the whole truth. the nature of both greek & roman religions is that they are adaptable and by no means singular. rather than it being a theft, the adaptation of greek figures into a roman context is the result of syncretism between greek religion brought to italy & autochthonous italian religion. because of the malleability of these religions, greek deities & mythologies could be brought to rome, incorporated in, and made roman without a problem. both civilizations tended to see foreign deities (not only each other's, but egyptian, sumerian, gallic, &c.) as the same gods under different names (see interpretatio graeca & interpretatio romana); as pliny says (nat. 2.5): itaque nomina alia aliis gentibus et numina in iisdem innumerabilia invenimus (thus we find other names [for the gods] among other peoples and countless gods among the same [peoples]).

in many cases, we don't have both A Greek Version & A Roman Version of a myth—it's one or the other (either because no such story existed in the other culture or because what once existed no longer does). when we do have both, the roman is often deeply conscious of the greek (both in similarities/parallels & deliberate differences); the syncretic nature of the mythology lends itself well to intertext! because of this, it can be difficult to draw a neat line dividing "the greek version" & "the roman version." (not to mention that neither tradition is a monolith. what we consider the respective corpora for greek & roman mythology contradict each other! often & enthusiastically!)

as for which one is better (more worth prioritizing), either in a specific instance or overall... that's not a question i, or anyone else, can answer with any authority or objectivity, unfortunately. i prefer rome to greece, so i would err on the side of roman. many classicists would disagree (and some would be mortally offended)! the truth is, neither of them is better or truer or more worthwhile or correct—they're different. that's the only answer i can give you.

now, for advice that you did not, strictly speaking, "ask for" but which i will provide anyway, on the topic of learning latin or ancient greek: i wouldn't stake it on mythological tradition, unless there's something you really want to read in the original (e.g. if you're really interested in the house of atreus, ancient greek will take you much further than latin). if you want to learn about mythology, english translations exist! many of them are even good! what i would weigh more heavily are questions like: what is my goal here? what do i want to get from this language? what am i interested in? which authors & texts speak to me? are there genres or literary traditions that i prefer? does one culture interest me more? what will make me happier?

that being said: learn latin. it's more fun.

#that last line is tongue in cheek if thats not clear! do not take my advice i am but a humble little scholar#ask#anonymous#long post

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

12 17 22 for the ask meme!

I almost forgot this one and I still have takes so here we go <3

12. favorite succ fanfiction/fanart/fanvid/uquiz?

how am I supposed to PICK?!?!! I've noted I've struggled with Fic because its really had to get the characters down. And I have this weird thing with like, Serious fanvids where they make me cringe? I don't know what it is! I really don't. But any Fanvid that takes itself seriously shivers me timbers. I've been this way all my life IDK why it is no hate to fanvid makers I'm just weird.

That being said it's a dead tie between the Togan fan vid and the Logan Roy Rolling with the LGBT fanvid.

17. funniest scene

Fuck bro that's so hard. The dead cat scene had me fucking yelling. The chaos of Retired Janitors... I love how the episode subverted expectations so much and the cat scene was peak.

22. favorite literary allusions or intertexts

This question is too smart for me I'm not gonna lie. There are some obvious ones like Oedipus and Odysseus and a shit load of greek and roman mythological and historical illusions but I can't think of a specific, personal fave.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Well, now we know why Pagan Deities were created and by whom, but I still need to see why God created Fairies.

This is an old ask that’s been floating in my inbox as thinksauce. I didn’t have anything meaningful to add but it made a nice little landing pad.

After rewatching Hammer of the Gods (Dabb & Loflin), and comparing it to The Gamblers (Glynn & Perez but, y’know, Dabb era), I’ve got Thoughts.

God made gods in reflection of Man’s wishes, but gods were here first and there’s billions of them, but “we were here first” fails to clarify much.

But chicken or the egg being a major theme, and a question lingering from Hammer of the Gods: How are there Billions of “us”, as Kali? How was it that Lucifer spoke of the gods surrendering the world to the current divine structure?

This is the Garden. Man’s beginning. The crossroads of divinity and mortality.

Even going biblical, “Man is like Us” after eating the fruit of knowledge.

Starve thou the mind of the world, brother; an old thelemic line that’s been plaguing me. If man Began in the garden, is it not the first place of thought? It’s where man was ejected from when eating the fruit that let him realize a bunch of shit, right? So then they were thrown out of this inner place into worlds that we summarily know are Chuck’s cages.

This isn’t even too dissimilar from The Architect in the Matrix. I recently asked Bobo, “Baudrillard or DeLillo?” to whence he said, Baudrillard is a useful form of address for a bulk of ideas, but he prefers the writing style of DeLillo, even if he hasn’t read White Noise since college.

I’m not gonna get into the full depth, in an old ask, about Baudrillard or DeLillo’s sum of concepts or how exactly they’re all applicable but let me just shorthand this with -- they are. Painfully so.

Many of you watched the Matrix while you were younger. It, too, used Baudrillard (which has a long cycle of hermetic lines of thinking.). In shorthand it botched the structure somewhat, though SPN is poised to avoid similar failings, but I’m going to point everyone to these two videos again, which I posted previously in february.

undefined

youtube

undefined

youtube

Watch both. 100% and absolutely. You’ll find familiarities. Ignoring that Chuck overtly called them “The One,” even ignoring the million TVs (although really, don’t ignore those, hell--they’re even relevant in the intertext and philosophy involved), you’ll find some things that just ping your radar over and over and over about our current structure.

Please be mindful that as many Matrixes as there are, they are made by a form of AI. Humans are the power cells. Cells. Souls. They run, power the matrix. In SPN, he who has the most souls is god. But the souls predate the matrix, even if from another world.

The first Matrix was perfect. Sublime even. And yet it did not take into account the “flawed” nature of man who rejected the control within it. Man ate the fruit, if you will, and caused a cataclysmic system collapse.

If man can make gods within the simulacrum and thus be assigned them by God in deferment, why then do we not presume outside of the simulacrum the primitive or protoman also did not, if only to construct the matrix in which we live?

The pagans were here first, and yet were created by God at the will of man. Fandom is quick to scream plotholes, but I’m looking to think a little more deeply on this. Because if Dabb can be credited by Adams as the maestro that even remembers details like Garth having gone to dental school (8.06 Southern Comfort, Adam Glass), are we really just going to be so arrogant as a fandom to think first impulse or lack of consideration warrants a plothole and Dabb forgot his own shit?

Because Dabb’s shit in Hammer of the Gods is poignant. There are. Billions of “us.” We were here first. Yes, it was the pagan gods speaking, but what makes a pagan god? They... think they’re better than humans and demons, so they can’t be human? Right, because demons were never human either? Why are there billions of gods when even if we were to combine world mythologies from the dawn of time we’d be lucky to pull together several thousand? That’s quite a number to choose to drop. Billions. Not even millions. Billions. What are there billions of? Hm.

God created what we know as pagan gods to deflect the blame. What did he create them from, I wonder?

Who are we? What are we billions strong in?

Thinkity think thinking.

#supernatural#spn#meta#my meta#pagan life#pagan gods#the matrix#baudrillard#dabb stop pls#how are you fucking me up from shit you wrote ten years ago#think i figured out who on crew is the actual hermetic student#jesus christ#or uh#jack kline#or maybe jack gladney#i can't tell if bobo was being coy when he asked 'what about him' when I fished about jack gladney#idk if he'd be like yeah that's it you figured it all out good job everybody go home#demiurge#cosmogenesis

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Cannibal & the Consulting Criminal:

How Silence and Sherlock Taught Me to Read

(I’m writing a series of autobiographical essays. This meta is a messy. messy warm up…)

PART I: TSotL The Odd Flash of Contextual Intelligence

Know your intertexts (and the limits of their influence)

I’ve spent a LOT of time writing about the influence of Harris on Mark Gatiss in particular. We have Harris to thank for Sherlock’s mind palace for starters. Moriarty and Dr. Lecter share many traits. Then again so do the psychiatrist and Sherlock. I’ll come back to these obvious connections between Sherlock and TSotL in a later part of this meta. (The connections are actually quite superficial.) For now I want to return to my first obsession: the genius cannibal who taught me how to read and the fandom that saved me from him.

Do your research.

Thomas Harris, author of The Silence of the Lambs, choses every word with great care. How many people, for example, do you know called Hannibal? Clarice is more common I suppose, but it’s certainly not a run-of-the-mill monicker. While starlings are the most common of birds have you ever met someone with that surname? Have you ever met a Lecter? What if I told you there is an extremely obscure historical figure called Hannibal the Starling? (You’ll find the reference in Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology if you seek.) Would you think that Harris must have heard of that man? Possibly. Possibly. If I told you that Harris makes most of his characters’ names up– that they sound plausible enough, but unless you’re an everyman like a Jack Crawford or a Will Graham you’re a Francis Dolarhyde or an Ardelia Mapp.

Ardelia Mapp? In the novel Ardelia is Clarice Starling’s roommate at the FBI academy. When exams roll around and Clarice has been too busy hunting Buffalo Bill to read her textbooks, it’s Ardelia who makes sure that Clarice knows all about search and seizures. Adelia Mapp. Ardeila Mapp. What kind of name is that? It helps if we cram along with Clarice:

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961), was a landmark case in criminal procedure, in which the United States Supreme Court decided that evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment, which protects against “unreasonable searches and seizures”, may not be used in criminal prosecutions in state [or] federal courts. (x)

Hey Thomas Harris!

Recognize when there’s a joke and you’re not getting it.

Thomas Harris amuses himself with language. Clarice comes from the Latin root clar and the words related to pertain to brilliance and light and the illustrative. And Lecter? So many people have tried to trace its origins but all becomes clear when you think about its etymology. In Latin lector means reader.

Clarice’s boss, Jack Crawford, likes to quote impressive sounding things out of context. Dr. Lecter mocks him for picking and choosing passages of the Meditations of the Roman Emperor, Stoic philosopher, and persecutor of Christians, Marcus Aurelius.

“I’ve read the cases, Clarice, have you? Everything you need to know to find him is right there [in the case files], if you’re paying attention. Even Inspector Emeritus, Crawford should have figured it out. Incidentally, did you read Crawford’s stupefying speech last year to the National Police academy? Spouting Marcus Aurelius on duty and honor and fortitude— we’ll see what kind of a Stoic Crawford is when Bella [his wife] bites the big one. He copies his philosophy out of Bartlett’s Familiar, I think. If he understood Marcus Aurelius, he might solve this case.”

“Tell me how.”

“When you show the odd flash of contextual intelligence, I forget your generation can’t read, Clarice. The Emperor councils simplicity. First principles. Of each particular thing, ask: What is it in itself, in its own constitution? What is its causal nature?”

“That doesn’t mean anything to me.”

“What does he do, the man you want?”

I could go on and on about how Harris allows Dr. Lecter to reference Stoicism and all kinds of other ideas for his own amusement. I say amusement because the reader need not understand Dr. Lecter’s jokes to enjoy Harris’ books. Clarice doesn’t and she doesn’t pretend to. Oh how Dr. Lecter fancies his student! I could go on and on because the entire fucking book is a compendium of in-jokes. That in itself is Stoic food for thought. Diogenes Laertius recounts a Stoic idea that Harris likes to chew on.

“Some appearances are expert (technikai), others are inexpert; at any rate a picture is observed differently by an expert and the inexpert person.”

Julia Annas explains:

A non-expert will just see figures; the expert will see figures that represent gods. The expert is right— there really is that significance- and the non-expert is missing something. What is more surprising to us is the claim that the appearance is itself “expert.” The expert is not seeing anything that is not there for the ignoramus to see. It is the fault of the ignoramus that he fails to see what is to be seen, because he fails to understand the content of what is presents to him. (82) - Hellenistic Philosophy of Mind by Julia Annas

Lecter, the consummate reader, is the expert. Clarice, who’s not more than one generation from the mines, is the ignoramus. Yet she shows the odd flash of contextual intelligence.

Discern clues from NOISE.

Though their relationship was weird, close, and lasting Clarice would never realize that Dr. Lecter gave her everything she needed to know to catch Buffalo Bill the first time they met!

On that fateful day, with instructions from Jack Crawford to note anything and everything she sees, Clarice shows enough intelligence to asks Dr. Lecter about the drawings in his cell. Dr. Lecter replies:

It’s Florence. That’s the Palazzo Vecchio and the Duomo, seen from the Belvedere. Do you know Florence?“

If Clarice were prepared "to read” Dr. Lecter’s work, she might have understood the significance of the image. She’s the very model of the Stoic ignoramus.

Clarice finds Buffalo Bill/Jame Gumb by recognizing his personal acquaintance with the first victim he skinned, Fredrica Bimmel. They both lived in Belvedere, Ohio where Clarice finds Gumb while Crawford’s teams go all SWAT on John Grant’s last known address. We find out later in the novel that Dr. Lecter knew Gumb lived in Belvedere, Ohio. Perhaps he was musing on the facts of the case while composing his sketches.

Jack Crawford, of all people, should have noticed the name “Belvedere” and made the connection. His dying wife’s name is Phyllis but he’s called her Bella for most of their entire relationship. Phyllis and Jack were both stationed in Italy and during one of their outings, a man called Phyllis “Bella,” or beauty. Bella is the feminine form; “bel” is the masculine form, as in bel vedere, or beautiful view. We learn later that Clarice has to work hard to trick herself into seeing any beauty in Belvedere, Ohio.

Now you’ve got the facts. Theorize with them.

There is another explanation as to why Crawford might have missed the clue in Dr. Lecter’s drawing from Clarice’s notes. Clarice does not know Italian. How would she have written the sketch’s title in her report? Dr. Lecter does not say, when she asks about the sketch, that is is the Old Plaza and the Dome seen from the Belvedere (pronounced in English, be-vuh-deer as in Belvedere, Ohio). Dr. Lecter says all the proper names in Italian except “Florence.” Florence is the English name for the city Italians call Firenze. Clarice’s ear would catch “Florence” and it may be that her report stated that the sketch was of Florence, but no further details. She doesn’t, after all, ask Dr. Lecter how to spell the names of the places with which she is unfamiliar. Crawford, reading a reasonably detailed report from Clarice, might have only noted that Dr. Lecter was sketching Florence– enough detail for a report if you don’t know what you’re looking at. Clarice, while an ignoramus in the Stoic sense, shows potential. Dr. Lecter is polite when he surmises that she is “innocent of the Gospel of St. John.” He calls her innocent, not ignorant. She’s simply not an expert in iconography. She sees all she can see in the image. Crawford, however, is experienced enough with Dr. Lecter to know how important images are to him. Will Graham captured Dr. Lecter in Red Dragon by recognizing that one of his victims was posed in a tableau of a Wound Man in one of Dr. Lecter’s books. Graham was an expert.

We can’t be sure from simply reading the text that Dr. Lecter isn’t making the epiphany of “Belvedere” especially difficult to decode even if Clarice were to have written a verbatim transcript of their discussion. In speech Dr. Lecter may be pronouncing the proper names as an American would, or, alternately, with an Italian accent. He could be pronouncing the incidental proper names (Palazzo Vecchio and the Duomo) in an Italian accent and “Belvedere” in an American accent to dare Clarice and Jack to take notice. Or, he could be pronouncing all the names in an Italian accent, a fact could be lost in translation between Clarice, innocent of Italian, and Crawford, who knows just enough to have had an epiphany. Each scenario is possible and each reveals a slightly different interpretation of Dr. Lecter’s motives. If we take Thomas Harris himself as the final authority, in the audiobook Harris reads Dr. Lecter’s part. Harris says all proper nouns including “Belvedere” with an Italian accent (albeit with a Mississippi drawl.)

Yeah ok SO WHAT?! And what about Sherlock?!

In Part II I’ll talk about TSotL as an intertext to Sherlock and the limits of this influence. I’ll compare Dr. Lecter’s method of reading to James Moriarty’s. I’ll talk about why & how I crawled out of the cannibal’s skull and into the consulting criminal’s and where I am going next… Or I just might try to revamp this to make more sense. I dunno…

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

what i read in march

several antigones & some other stuff

call me zebra, azareen van der vliet oloomi

oh boy. i really wanted to like this one, but uh. nah. so this book is about zebra, a young iranian-american from a lineage of ‘autodidacts, anarchists and atheists’, still traumatised by her childhood experience as a refugee (incl. her mother’s death on route). when her father dies years later, zebra decides to retrace the route of her exile thru barcelona, turkey, and back to iran. this sounds great! the beginning is good! but zebra is a quixotic figure (don quixote is unsubtly flagged as THE intertext several times), delusional about her own importance, obsessed with some kind of great literary mission and obnoxious & condescending & egotistic as all fuck (she looks down on students but treats her realisation that like, intertextuality is a thing, as this grand revelation when like..... we been knew since Lit. Theory 101) - and this is intentional & part of the quixotic thing & in general i approve of abrasive & bristly & difficult female characters BUT i expected there to be a gradual process of realisation where she sees that a) maybe her entirely male lineage of geniuses ain’t all that, c) her mission is uh.... incomprehensible. instead, once she reaches spain, she gets bogged down in endless pretentious bullshit and a #toxic relationship that takes up way too much space. knowing that all of that is likely intentional doesn’t.... make it good. also the writing is pretty overwrought for the most part & not even your narrator’s voice being Like That excuses plain bad writing, like the absurd overuse of ‘intone’ and ‘pose’ as dialogue tags. i see the potential and i see the point & i liked some of it but uh. not good. 2/5, regretfully, generously

in the distance, hernan diaz

i don’t really go for westerns or man vs wilderness stories but damn i’m impressed. despite the violence & deprivation and sheer amount of gross shit, this story of a swedish immigrant getting lost in the american west for decades remains at its core so human, so tender, so sad (honestly this book is SO SAD, yet sometimes oddly hopeful), so evocative of isolation, loneliness, and the desire for human connection. 4/5

notes on a thesis, tiphaine rivière (tr. from french)

god, if i ever considered doing a phd i sure don’t anymore. this is a short graphic novel about a young woman’s descent into academic hell while writing her dissertation about labyrinths in kafka. it’s funny, the art is expressive and fanciful, and it is incredibly relateable if you’ve ever tried to actually write your brilliant, glorious, intricately constructed argument down, battled uni administration or had a panic attack over how to phrase a harmless email to a prof. Academia: Not Even Once. 3.5/5

red mars, kim stanley robinson

this is a very long hard sci-fi novel about mars colonisation & terraforming, discussing the ethics of terraforming, the potentials of a truly ‘martian’ culture, and how capitalism will inevitably fuck everything up, including outer space. all of this is up my alley and i did really like the first half (early colonisation efforts), but the 2nd half (beginning of terraforming, lots of politicking) was a slog - i liked reading about how terraforming was going, but the rest was just bloated, scattered and confusing. also there’s a tedious love triangle the whole time. 2/5

dragon keeper (rain wild chronicles #1), robin hobb

i love robin hobb she really can write a whole 500+ page book of set-up, characterisation and politicking and make it WORK. anyway, this has disabled dragons, a quest for mystical city, lots of rain wilds weirdness, a dragon scholar in an unhappy marriage, liveships, a sweet dummy romance, and uh... a lil penpalship between two messenger bird keepers? not much happens but it’s so NICE & so much is going to happen. also althea & brashen & malta turned up & i screamed. 3.5/5

season of migration to the north, tayeb salih (tr. from arabic)

this is a seminal work of post-colonial arabic literature, a haunting tale of the impact of colonialisation, especially of cultural hegemony in the education system, the disturbing dynamics of orientalism and sex, and village life in a modernising post-colonial sudan. it’s important, it’s well-written, it’ll make you think, but fair warning, there is a lot of violence against women - it has a point but still uh... wow. 3.5/5

dune, frank herbert

SOMETIMES.... BOOKS THAT ARE CONSIDERED MASTERWORKS OF THEIR GENRE.... ARE WORSE. so much worse. the writing in this is atrocious (”his voice was charged with unspeakable adjectives”), herbert somehow manages to make court intrigue and plotting UNBELIEVABLY DULL and sure, it was the 60s, but i’m p sure people knew imperialism was bad in the 60s! the main character, the eugenically-engineered chosen one or whatever, literally spends years among the oppressed & resisting natives of a planet ruled by a space!empire and at the end he’s like ‘i own this planet bc imperialism is Good Actually’. emotionally neglecting/abusing your wife, who you (!!!) decided (!!!) to marry for political reasons bc you’d rather marry your gf is also Good Actually (cosigned by the protag’s mother....) the worldbuilding is influential for the genre, sure w/e, but mainly notable for there just.... being a lot of it, the whole mythology-science makes No Goddamn Sense, all around this is just Bad. Bad. 0.5/5 i hope the Really Big Worms eat everyone

dragon haven (rain wild chronicles #2), robin hobb

this healed my soul after toxic exposure to dune. anyway w/o spoilers: everyone is very much In Their Feelings (including me) and there’s a lot of Romance and Internal Conflict and Feelings Drama and Complicated Relationships and Group Dynamics and also dragons, which are really like very big, very haughty cats who can speak, and a flood and a living river barge with a mind of his own (love u tarman!). it’s still slow and languid but so so good. also: several people in this have to be told that People Are Gay, Steven, including Sedric, who is himself Gay People. 4/5

an unkindness of ghosts, solomon rivers

super interesting scifi story set on a generation ship with a radically stratified society in which the predominantly black lowerdeckers are oppressed and exploited by the predominantly white upperdeckers, mixed in with a lot of Gender Stuff (the lowerdeckers seem to have a much less stable and binary gender system than the upperdeckers) and neuroatypicality. it’s conceptually rich and full of potential, but just doesn’t quite stick the landing when it comes to the plot. 3/5

sanatorium under the sign of the hourglass, bruno schulz (tr. from polish)

more dreamy surreal short stories (ish?). i didn’t like this collection quite as much as the amazing street of crocodiles, but they are still really good, even tho you never quite know what is going on. featuring flights of birds, people turning into insects, thoughts about seasons and time, fireman pupae stuck in the chimney, and the continuing weird fixation on adela the maid. 3.5/5

angela merkel ist hitlers tocher, christian alt & christian schiffer

a fun & accessible guide to conspiracy theories, focusing on the current situation in germany and the current boom in conspiracy theories, but also including some historical notes. i wish it had been a bit less fun & flippant and more in-depth and detailed bc it really is quite shallow at points, but oh well. also yes the title does indeed translate to ‘angela merkel is hitler’s daughter’ so. yes. 2.5/5

the midwich cuckoos, john wyndham

fun lil scifi story in which almost all women in sleepy village midwich are suddenly pregnant, all at the same time. the resulting children, predictably, are strange, creepy, and possibly a threat to humanity. i get that it was written in the 50s but it is strange to read a book where almost all women, and only women, are affected by A Thing, but all the main characters are men & no one tells the women ‘hey we think it’s xenogenesis’ - like realistically 80% of women affected went to the Neighbourhood Lady Who Takes Care of These Things like ‘hello, one (1) abortion please’ and the plot just ended there. i still liked it tho! 3/5

antigone project

antigone, the original bitch, by sophocles (tr. by fagles)

god antigone really is That Bitch. that’s all i have to say. 4.5/5

antigone, That Bitch but in french, jean anouilh

the Nazi-occupied france antigone. loved the meta commentary on what tragedy is and how antigone has to step into the Role of Antigone, which will kill her “but there’s nothing she can do. her name is antigone and she will have to play her part through to the end”. i didn’t really like (esp. given the ~historical context) the choice to make creon much more sympathetic, trying to save antigone’s life from the beginning. hmm. 3.5/5

antigonick, anne carson

look, antigone really is That Bitch and you know what? so is anne carson. best thing i’ve read so far this year, don’t ask me about it or i’ll yell the task of the translator of antigone at you. 5/5

home fire, kamila shamsie

honestly i really wanted to like this bc politically it’s on point and an anti-islamophobia antigone sounds amazing, but it just doesn’t succeed as a book/adaption. it spends way too much time in build-up/backstory (the play’s plot only starts in the second half of the book!), waaayyy to much time on the weirdly fetishistic antigone/haimon romance, and even the most interesting characters (ismene & creon) don’t fully work out. sad. 2/5

currently reading: the magic mountain by thomas mann, but i should be done in a week or so! also: the paper menagerie by ken liu, a collection of sff short stories

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

THE LONG AND VARIED career of Robert Silverberg can almost be viewed as a microcosm of the SF genre’s development over the past six decades. Starting out in the world of fandom, Silverberg edited a popular zine in the early 1950s, then turned to professional writing during the SF boom of the mid-’50s, producing hundreds of stories — under his own name and numerous pseudonyms — for the pulp and digest magazines of that time. Most of this material was clearly apprentice work, though estimable enough to earn him a 1956 Hugo Award for Most Promising New Author. When the boom went bust in the late ’50s, and most of the magazine markets folded or retrenched, Silverberg, like many of the decade’s authors, moved on to other literary endeavors — mostly young adult nonfiction and soft-core pornography, two disparate fields in which he produced well over 100 titles during the early 1960s.

The mid-1960s paperback boom, coinciding with the advent of the New Wave, lured the author back into the genre full-time, and soon he was producing some of the most ambitious SF of the period — novels like Thorns (1967) and The Book of Skulls (1972), stories like “Sundance” (1969) and “Born with the Dead” (1974) — as well as editing a major anthology series, New Dimensions (1971–’81). When the serial novel with quest-fantasy elements became popular in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Silverberg emerged from a brief hiatus with his Majipoor series. For two decades thereafter, he continued to publish steadily, producing roughly one book per year, up until his retirement from novel-writing in the mid-2000s. His work during this period often reflected, even while complicating, contemporary trends, such as an emphasis on mythic intertexts (e.g., 1984’s Gilgamesh the King), evolutionary speculation (e.g., 1988’s At Winter’s End), and religious allegory (e.g., 1992’s Kingdoms of the Wall).

But throughout his career, Silverberg returned obsessively to one of the genre’s key motifs — time travel — upon which he spun elaborate and strikingly original variations. During his New Wave heyday, when he was one of the preeminent American SF writers, he produced six novels dealing centrally with themes of temporal transit or displacement — The Time Hoppers (1967), Hawksbill Station (1968), The Masks of Time (1968), Up the Line (1969), Son of Man (1971), and The Stochastic Man (1975) — his treatment of the topic ranging from straightforward adventure stories to heady philosophical disquisitions. The new collection Time and Time Again: Sixteen Trips in Time (Three Rooms Press, 2018), which gathers 16 stories published between 1956 and 2007, provides a robust — and very welcome — conspectus of Silverberg’s short fiction on the subject. (This is the third book Silverberg has edited for Three Rooms Press, all thematically organized, following 2016’s This Way to the End Times, an anthology of apocalyptic fiction, and 2017’s First Person Singularities, a collection of the author’s most innovative first-person narratives.)

As this collection makes abundantly clear, Silverberg is a master of virtually every subgenre of the time travel story, his mastery increasing as his career developed and he became confident enough to depart from ready formulas. Take, for example, the “time loop” narrative, in which a character becomes stuck in a recursive temporal coil, doomed to repeat the same cycle of events. The first story in Time and Time Again, “Absolutely Inflexible” (1956), is a clever but unambitious treatment, in which a bureaucrat whose job involves exiling time-travelers to the moon winds up, by some technological sleight-of-hand, confronting and banishing himself. By contrast with this tale’s easy ironies, the later “Many Mansions” (1973) — written during the zenith of Silverberg’s New Wave renaissance — is a delirious, multiply forking mind-fuck of a story, which begins with a fairly standard premise (traveling into the past to have sex with and/or kill an ancestor) but quickly morphs into a puzzle box of circular paradoxes impossible to resolve into linear coherence. In his introduction to the story, Silverberg reveals that he modeled his approach on Robert Coover’s “The Babysitter” (1969), “in which a narrative situation is dissected and refracted in an almost Cubist fashion.” The result is brilliantly metafictional, the time-loop story as cut-up farce.

Another New Wave–era story, “Breckenridge and the Continuum” (1973), is an even more wildly experimental variant. Silverberg’s inspiration this time was structuralist theory, in particular the mythological schemas of Claude Lévi-Strauss, which are applied to the experiences of the eponymous stockbroker as he shifts back and forth between a mundane present of business meetings and cocktail parties and a chimerical far future, where he has become a nomadic bard dispensing garbled versions of classic myths. As he travels over the blighted landscape, Breckinridge develops “structural hypotheses” to account for his predicament, “the outlines of a master myth” of cyclical degeneration and rebirth. Here, the time loop functions as a potent metaphor for midlife crisis, loss of faith, and striving for renewal — a theme Silverberg suggests was central to his own life at the time. Having just moved to California,

[e]verything was still an experiment for me […] so it was not surprising that my fiction would take an experimental turn […] The early 1970s were, as you may have heard, a pretty freaky time in Western culture, especially in California, and when I wasn’t writing I was investigating a lot of odd corners of intellectual life.

The ethos of the California counterculture hovers over several of these stories, none more so than the haunting (and significantly titled) “Trips,” from 1974. While narratively similar, this is not a time-loop tale but rather one of parallel time-tracks, “alternative universe[s]” — as the author explains — that “tak[e] the voyager sidewise in time to other possible contemporary worlds.” The sojourner here is a San Francisco hipster on the run from a marriage grown stale, tracking his familiar partner through unfamiliar worlds — worlds that “have undergone a slight shift along the spectrum of events” and in which it might be possible to re-experience “that jolting gift of novelty which his Elizabeth can never again offer him.” With its psychedelic scene-shifting, its restless eroticism, and its deliquescent sense of personal identity — not to mention its portentous epigraph by Carlos Castaneda — this is at once a classic example of counterculture fiction and a brilliant satire of countercultural mores, of a lifestyle driven by an urgent, almost pathological quest for change. The passages narrated in the second person implicate the reader uneasily in the amorphous yearnings of the rather feckless protagonist: “It’s all trips, this universe. What else is there? There isn’t anything but trips. Just trips. So here you are, friend. New frameworks! New patterns! New!”

Silverberg always had a somewhat distanced, ironic appreciation for the experimental impulses of the 1960s, even as he pursued them himself, at least in his fiction. His most overtly countercultural novel, Son of Man, propels a 20th-century man into an unhinged far future where the endless possibilities of self-invention available to its denizens subject his philosophical and sexual certitudes to a hallucinatory, mind-expanding deconstruction. As Silverberg comments in his introduction to “Dancers in the Time-Flux” (1983), a story set in the same universe as Son of Man, his goal was “to reproduce in prose form some of the visionary aspects of life in that heady era [the 1960s] and pass off the result as a portrait of the far, far future.” The novel is a phantasmagoric masterpiece, but the story is a more mundane affair, a rather plodding sequel that attempts to recapture the unearthly radicalism of the counterculture but only manages to show that sometimes, even if you have a time machine, you can’t get there from here. (“Dancers” is the only sequel in Time and Time Again, though the volume also contains the novella that seeded Silverberg’s 1968 novel Hawksbill Station, about a penal colony in the primordial past where the political prisoners of a future dystopia are temporally exiled.)

Another key theme of “Trips” is the brittle contingency of intimate relationships, as revealed by alternative timelines in which lovers never met, or just missed meeting, or met in some ambivalent or rancorous way. “Jennifer’s Lover” (1982), in which a man loses his wife to an incestuous, time-tripping descendant, and “The Far Side of the Bell-Shaped Curve” (1982), whose protagonist seeks to eliminate an erotic rival by temporally out-maneuvering him, are entertaining if lightweight variants on the theme, but “Needle in the Timestack” (1983) is considerably more substantial and affecting. The plot is similar to “Bell-Shaped Curve” — a loving couple finds their marriage under siege at the hands of a jilted ex who, by traveling to and selectively editing the past, hopes to “phase” their relationship out of existence — but the treatment is much richer and more satisfying. “Needle” is both a thoughtfully worked-out SF scenario — as Silverberg extrapolates the psychological nuances of having one’s memories involuntarily reordered — and a compelling human story, as the couple struggle to hold on to an emotional bond that is being retroactively erased out from under them. Stories like this — and “Trips” and “Breckenridge” — display Silverberg’s admirable ability to take a hallowed SF premise in provocative new directions.

Most of the remaining stories can be grouped into two other subgenres of the time travel narrative: tales of “time tourism,” in which voyagers leisurely sample different epochs of history, and tales of anachronism, in which a person or artifact from the past or future arrives and disrupts the present day. In the latter category, the most effective example is “What We Learned from this Morning’s Newspaper” (1972), wherein neighbors on a suburban block are first puzzled, then excited, and finally undone by the bizarre appearance on their doorsteps of next week’s newspaper. Their scheme to game the stock market based on this lucky preview of future prices is undermined by an “entropic creep” that blurs out the paper’s pages and, eventually, everyday life itself. “Gianni” (1982) is a more predictable, though quite funny, story in which an 18th-century composer, time-slipped into near-future Los Angeles, decides to join a pop band.

Silverberg’s classic treatment of time tourism is his 1969 novel Up the Line, where guides ferry paying customers into the past, nimbly dodging paradoxes and the multiplying versions of their future selves. The weakest effort in the collection fits into this category — “Hunters in the Forest” (1991), a pedestrian tale (despite the clever final twist) of sportsmen stalking dinosaurs — but so too does the strongest: the gorgeously elegiac, Nebula-winning novella Sailing to Byzantium (1985). Set in a decadent far future, where simulacra of historical metropolises are built and then demolished for the pleasure of jaded immortals, the story focuses on the geographic and erotic wanderings of a 20th-century man inexplicably awakened there. This is a New Wave story in the filmic sense: the narrative has the mesmerizing pace and dreamlike intensity of Alain Resnais or Michelangelo Antonioni, and the characters are straight out of La Dolce Vita: a languidly beautiful jet set, “wandering with the wind, moving from city to city as the whim took them,” alternately bemused and irritated by the protagonist’s archaic stabs of conscience and angsty self-questioning.

In Up the Line, Silverberg featured ancient Byzantium — a seemingly timeless city, in which the Roman Empire survived for a millennium after its demise in the West — as the main site of touristic jaunts, reconstructing the city’s famous events and monuments via meticulous historical research. (Silverberg has written some important works of history that remain classic studies of their topics — e.g., The Golden Dream: Seekers of El Dorado [1967] and The Realm of Prester John [1972].) But the city of Sailing to Byzantium is, as its allusive title suggests, closer to the beguiling Empyrean of Yeats, a promise of ageless beauty and wonder that Silverberg, at the end, translates into pure science fiction: “[I]t isn’t necessary to be mortal […] [W]e can allow ourselves to be gathered into the artifice of eternity, […] we can be transformed, […] we can move beyond the flesh” — quite literally. It is a moving and unforgettable story.

But it is a well-known — indeed, as noted, a highly celebrated — work, and one that I had read before. The real revelation of the book, for me, was its capstone, the most recently published tale, “Against the Current” (2007). One of the most prolific authors in SF history, who at the height of his powers could generate a million words of publishable prose annually, Silverberg has, during the last two decades, produced only around two dozen stories. He frankly admits that he is financially comfortable and creatively content with his career, but “even an aging writer who feels he has said just about all he wants to say […] still does occasionally feel the irresistible pull of a story that demands to be written.” The idea for “Against the Current,” he says, just popped into his head and wouldn’t let go until he set it down on paper. As readers, we can only be grateful, because the story is astonishingly good — polished, ingenious, and heartbreaking.

The premise is simple: a Bay Area used-car dealer, after experiencing a sudden bout of dizziness, decides to leave work early; as he drives from his Oakland lot to his San Francisco home, it slowly dawns on him that he is moving steadily into his own past. Architectural landmarks shift and disappear, newspaper headlines scroll backward, years melt away in hours, yet he still seems to be traveling at normal pace from event to event. His wife, after a time, is no longer (or not yet?) his wife, not even someone he can identify or locate. He does track down his college roommate, a Berkeley hippie who listens goggle-eyed to his incredible story, while the protagonist gapes at an era reborn:

It all was like a movie set, a careful, loving reconstruction of [the 1960s] […] He had lost Jenny, he had lost his nice condominium, he had lost his car dealership, but other things that he thought were lost, like this Day-Glo tie-dyed world of his youth, were coming back to him. Only they weren’t coming for long, he knew. One by one they would present themselves, tantalizing flashes of a returning past, and then they’d go streaming onward, lost to him like everything else, lost for a second and terribly final time.

The affective charge is a kind of reverse nostalgia, literally restoring the past and then consigning it to oblivion. Silverberg makes no attempt to explain — to rationalize in science-fictional terms — this temporal turnabout; like his protagonist, he just goes with the flow. The tale reminds me a bit of John Cheever’s classic 1964 story “The Swimmer,” a similarly arresting mix of surrealism and mundanity, wherein the protagonist bleakly regresses through a palimpsest of past selves. But whereas Cheever’s hero was oblivious, in denial, Silverberg’s is serenely accepting, having “entered some realm beyond all possibility of surprise.” At the end (in a deliberate Gatsby-esque echo evoked by the story’s title), he seems prepared to “just go endlessly onward […] a perpetual journey backward, backward, ever backward.” “Against the Current” was published in a SF magazine, but it is, as Silverberg acknowledges, an “out-of-genre” story — one that could, I think, have fit comfortably into the pages of Harper’s or The New Yorker.

This leads me to my final point — Silverberg’s scandalous lack of crossover success in the literary mainstream. Other New Wave–era writers — J. G. Ballard, Ursula K. Le Guin, Philip K. Dick, Samuel R. Delany — have enjoyed such success (in Dick’s case, posthumously): they are, in essence, now viewed as major contemporary novelists who happen to deploy the themes and forms of science fiction. Yet Silverberg was (and is) at least their equal, and novels like Dying Inside (1972), The Book of Skulls, and The Stochastic Man are so ideationally and emotionally rich that there is no reason that discerning non-genre readers shouldn’t warmly embrace them. Happily, most of the author’s major novels are available cheaply on Kindle, as is a nine-volume compendium of his “Collected Stories,” with illuminating headnotes. In the meantime, Time and Time Again serves as a solid and engaging introduction.

¤

Rob Latham is a LARB senior editor. His most recent book is Science Fiction Criticism: An Anthology of Essential Writings (Bloomsbury, 2017).

The post Temporal Turmoil: The Time Travel Stories of Robert Silverberg appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2FuPLjb

0 notes

Link

I liked the idea of a story in episodes that would go on for a long time.

— David Lynch (1997)

¤

DAVID LYNCH AGES GRACEFULLY. Proof is in footage from the making of Eraserhead, confirming that Lynch was not born with his silver, pomaded hairstyle, and that the lines of maturity make him look less goofy than he did in his post-college years. Almost unfaltering critical success and international fame have made the concept of Lynch plausible: his once curious, shambolic persona has been a brand since the 1990s. In “Part 14” of the much-awaited — and one-year overdue — return of Twin Peaks, FBI Deputy Director Gordon Cole (David Lynch) retells a fresh “Monica Bellucci dream,” in which Cole and Bellucci (as herself) have a terrace coffee in a Paris street. Asking who is “the dreamer [who dreams and then lives inside the dream],” Bellucci makes a sign for Cole to look over his shoulder. The dream cuts to a shot from Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), showing Cole at his FBI headquarters desk, 25-odd years previous, brown-haired, full-cheeked, with an air of concern on his face. Present-day Cole recounts: “I saw myself. I saw myself from … long ago. In the old Philadelphia offices.” Philadelphia holds significance in Lynch’s personal mythology. It is the city where Lynch, as an art student, first started experimenting with animation and, soon after, film. The dreamer who Bellucci referenced a moment before, he who lives within his own dream, might very well be David Lynch looking back on himself as a cultural subject — one for whom thinking creatively accounts for such a great part in biography and idiosyncrasy.

From the moment he was given a platform to talk about his journey into cinema and television, Lynch has talked about life in Philadelphia — where he attended art school, got married, became a father — as a source of dread and inspiration in and of itself. The influence of his college education on his artistic development seems to pale in comparison to that of the city itself, and it has been suggested, whether in good faith or not, that Lynch’s primary sources are rooted in his perception of the physical and social environment rather than in aesthetic and theoretical teachings he received. Candidly, in a BBC documentary on the history of the Surrealists in film that he was asked to host in 1987, Lynch talked about Philadelphia as “one of the sickest, most corrupt, decadent, fear-ridden cities that exists.” The dramatic quote has followed him everywhere, but he has not, to my knowledge, nuanced it since. The memories from Philadelphia are so strong partly because they are always interpreted in contrast with an earlier, idyllic past in Lynch’s Midwestern childhood. Against this comparatively happy, easy, wholesome time and place, urban societies have always seemed — if only at first sight — toxic. (This is with the exception perhaps of Los Angeles, a city where the sun shines and where, Lynch claims, there is “something in the air.”) However, as his manifest attachment to past selves and identities suggests (see the persistence of his birthplace, Missoula, Montana, and of his Eagle Scout ranking on his Twitter bio), a preserved naïveté is an integral part of his mature artistic persona.

In the opening sequence of last year’s documentary David Lynch: The Art Life, a montage of Super 8 family film footage gives a glimpse of this “simple” and elated postwar American childhood. The film director’s voice retells fragments from a happy early life among a loving mother, father, brother, and sister, and each memory sounds sensorily close and relevant. On a hot summer day in Idaho, Lynch remembers having been placed in a man-made pool of muddied water in the garden of his parents’ house in the company of Dickie Smith, another toddler from the neighborhood who was his friend. The two boys had been sent there together for protection against the scorching heat, and Lynch remembers how this simple arrangement enabled him to enjoy the garden, the pleasantness of the mud forming under his fingers, and the proximity of a friend who was sharing in his excitement. The memory of this scene, today, is so palpable that it becomes a bit overwhelming: “Forget it,” Lynch concludes with a smile.

Much of Lynch’s artistic coming of age, as he retells it in the documentary, involves the thematic elements of this happy anecdote: the immediate excitement of creative experimentation and the joy of sharing this work, this lifestyle — the “art life.” Through the rest of the film, the director is pictured handling rust-colored paint, which he smears onto the flat surface of a canvas in his current Los Angeles studio. Though his hands are clad in surgical gloves, the idea of the mud of the opening memory is not distant. Viewers may feel far removed from the clean and remote technicality of film, the medium with which Lynch’s work is predominantly associated. Yet the documentary closely examines this other, enduring side of Lynch’s artistic process, one that relies on primary, unmediated experimentation with matter and texture. Lula, Lynch’s two-year-old daughter, is walking around the studio, grasping the look and feel of various objects from her own perspective. There is a shot of a furry gray moth fluttering against a window pane. Later, Lynch comments on the amazing textures hidden within the body of the smallest organic creatures: insects, fish, small animals.

The life and death of organic matter can be as curious and spectacular in Lynch’s aesthetic as the workings of technology. Such curiosity brings his work to tread a fine line between the sheer beauty of changing organic forms and the abject horror that bodies conventionally represent when they are subject to death and decay. Lynch recounts that as an art student in Philadelphia he kept a special room in his building’s basement for artistic “experimentations,” which consisted in gathering organic matter, animal or vegetal, and leaving it to rot while recording all the successive physical changes of these transformations. This experimental preoccupation anticipates the dead cat in Eraserhead, the ear in Blue Velvet, or even the fantastic “Children’s Fish Kit” Lynch assembled in a 1979 photo-based art piece, giving instructions to assemble a (dead) mackerel he had chopped up into three pieces, like the parts of a mechanic toy. The bloody mess around the pieces of this gory puzzle testified to either the idiocy or malevolence of the maker of the “kit.” As Lynch remembered it, his father’s reaction when he showed him the experimental basement room was, unsurprisingly perhaps, one of palpable sadness and concern. This impression was confirmed to him when his father advised him a moment later, à propos de rien, never to have any children.