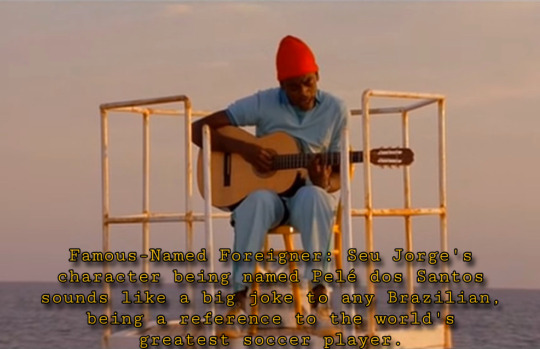

#Pelé dos Santos

Text

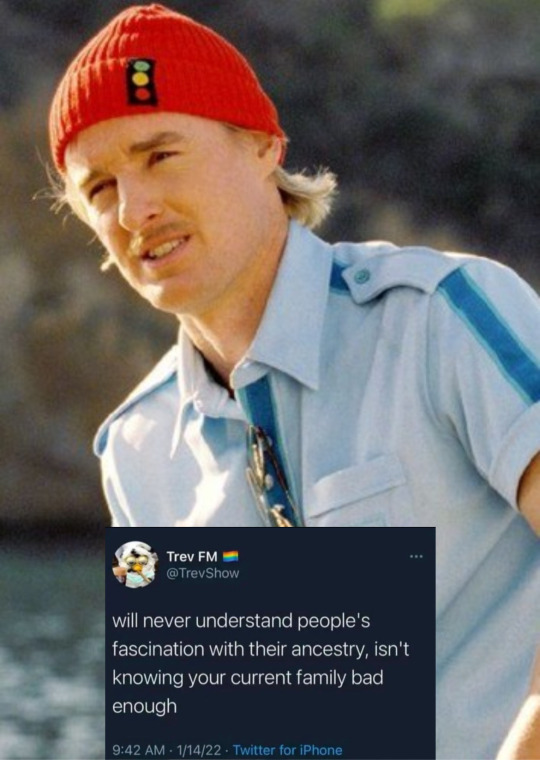

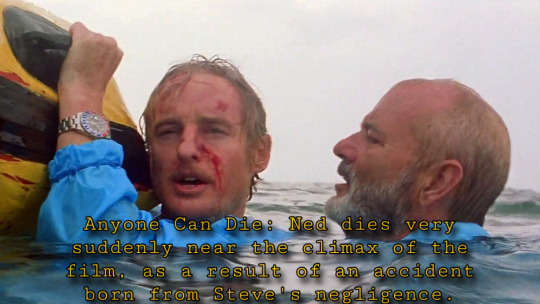

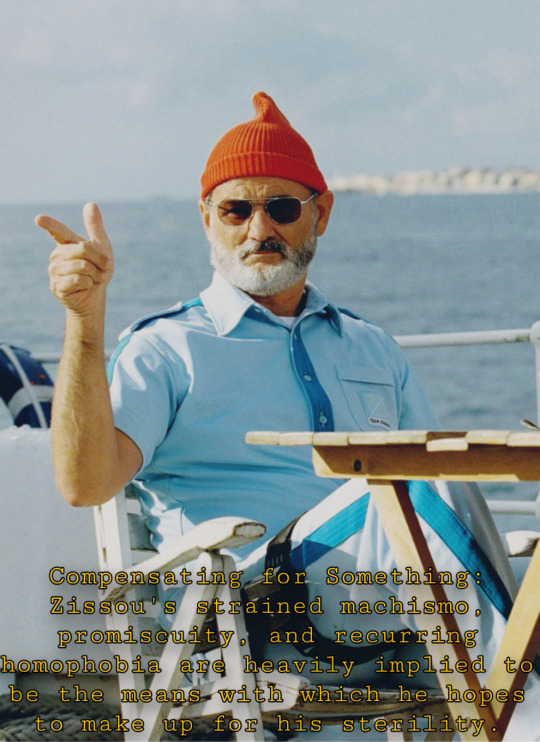

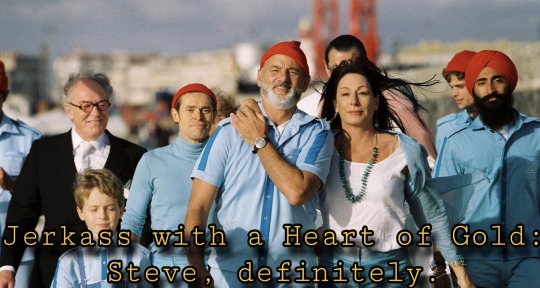

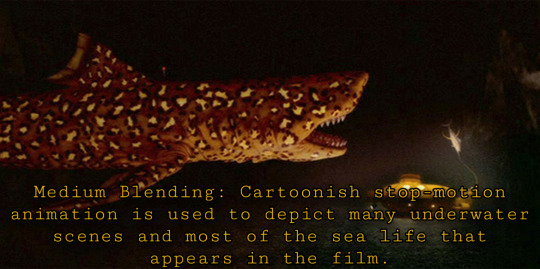

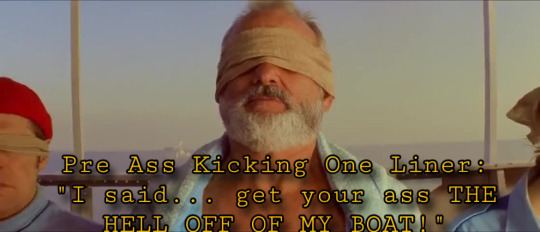

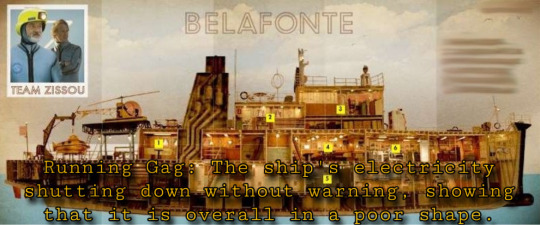

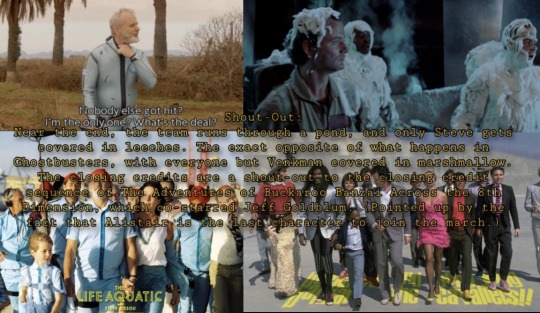

Wes Anderson Movies + textpost part 9/11 (or until I give up)

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou edition

#wes anderson#the life aquatic with steve zissou#steve zissou#bill murray#Ned Plimpton#owen wilson#Klaus Daimler#willem dafoe#Jane winslett-Richardson#cate blanchett#Eleanor Zissou#anjelica huston#Alistair Hennessey#jeff goldblum#Pelé dos Santos#seu jorge#shut up pretty boy

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

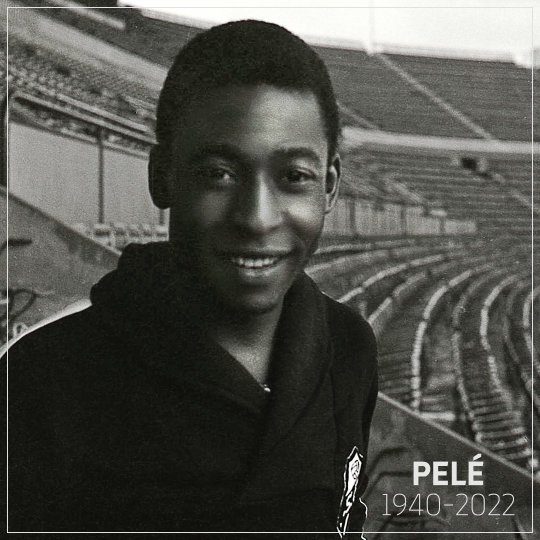

pelé

277 notes

·

View notes

Text

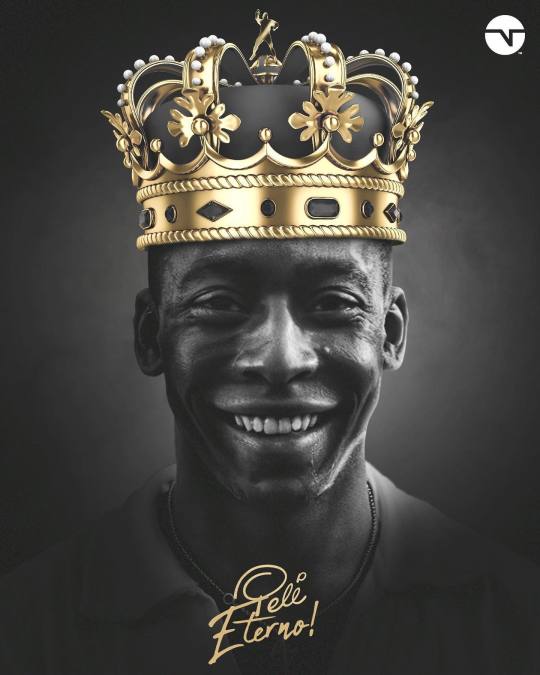

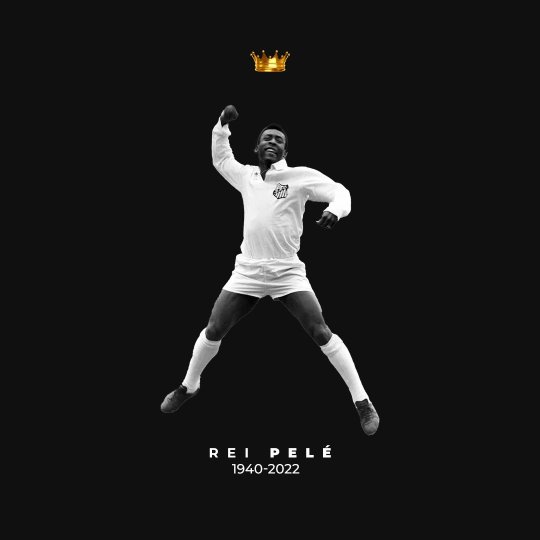

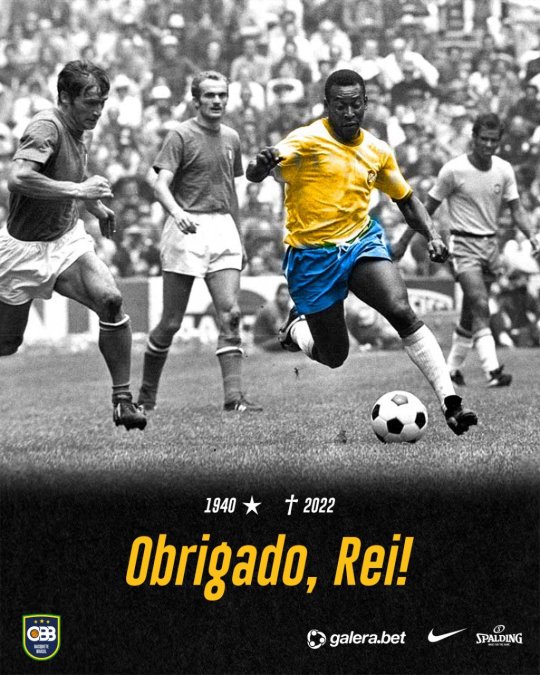

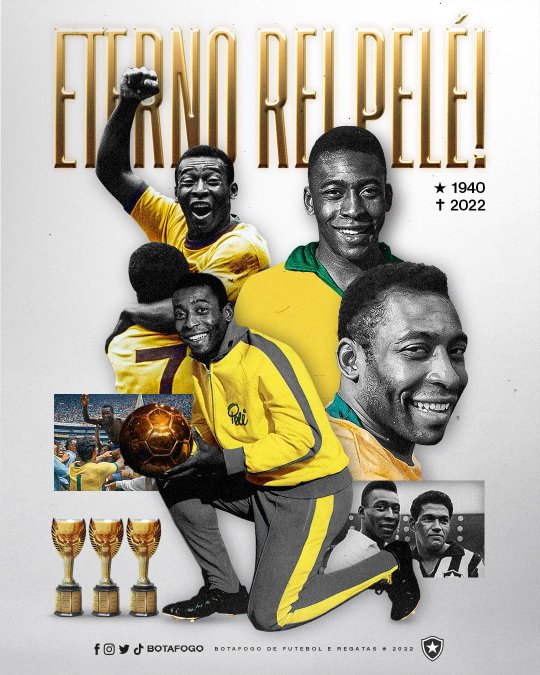

The King is dead. Long live the King!

#edson arantes do nascimento#Pelé#pele#Brazil NT#seleção brasileira#Santos FC#football#fußball#fussball#foot#fodbod#futbol#futebol#soccer#calcio

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you!

That's the only thing i can say to you, king.

Rest in piece! You were big in life, too big for this world, i'll love you forever.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

vasco headers

like se salvar

#headers#sem psd#vasco#vasco da gama#crvg#club de regatas vasco da gama#gabriel pec#andrey santos#manuel capasso#leo pelé#pedro raul garay#miranda#nenê#clássico dos milhões#jogadores#brasileirão#campeonato brasileiro#futebol#cbf

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ha muerto un mundo

Esa fue la frase que eligió una revista francesa para su portada luego de que se conociera la muerte de Edson Arantes do Nascimento. Cuando yo nací “o Rei” llevaba 6 años retirado del fútbol, ya era una figura totémica que se paseaba de terno y corbata por las canchas del orbe, la FIFA lo acompañaba y seguía ayudando en la promoción del fútbol a largo del mundo, para mí era una suerte de caballero del balompié, que contrastaba rotundamente con el irreverente Pelusa, por donde pasaba Pelé se notaba que dejaba una estela nobiliaria futbolística imposible de negar.

Gracias a la tecnología hemos tenido la posibilidad de ver partidos históricos, así desentrañé, con mi vista, la importancia del brasileño. Debemos contextualizar la época en que el joven Pelé debutó en un mundial con su selección; no existían las reglas arbitrales actuales, técnicamente los defensas podían salir al encuentro para matarte si eso significaba frenar el ataque de los jugadores habilidosos y no se les penalizaba con expulsión. De hecho en el mundial que se realizó en Chile el jugador recibió tantas patadas en los primeros partidos que, finalmente, acabó lesionado. Luego está el tema de la pelota, que era fabricada con cuero de cromo, por lo tanto era muchísimo más pesada que los actuales balones y cuando llovía aumentaba más su carga, puesto que absorbía agua. Finalmente hay que nombrar las condiciones del terreno de juego, en donde no existía el nivel de tecnología como para tener campos de pasto en un clima semidesértico o buenos drenajes. En las grabaciones en blanco y negro siempre se ve algo irregular la cancha a la hora de los pases rasantes.

Lo increíble es que a pesar de todas estas dificultades si observamos en los videos pareciera que Pelé juega con una pelota liviana, en un campo casi sin alteraciones y con defensas lentos que siempre logra pasarse, he ahí lo improbable de la vida de Edson, el chico pobre que nació en un pueblito a las afueras de Minas Gerais, siempre dijo que nació así, pero que él trabajó el don y claramente por la maestría que se ve en las imágenes queda ese esfuerzo demostrado. Cada vez que le preguntan a Menotti por el mejor del mundo, no lo duda ni medio segundo “el negro fue el mejor” es su frase, comentaba que era dotadísimo que tenía una fisonomía de boxeador, otros hablan que era como un pantera, en los videos se ve absolutamente atlético. La otra cosa es su nivel mágico de técnica; regates, corridas, saltos, cabezazos, toques imposibles, verdaderamente, como dijo una vez Garrincha cuando le preguntaron por su compañero “Pelé es el hombre gol”. Así se le ve de 17 años cuando hace uno de los cinco tantos a Suecia, un gol ficcional en el cual levanta la pelota por sobre el defensa y luego hace una bolea semi karateka para patear el balón o ese casi gol en contra a Uruguay donde realiza una carrera en velocidad, se pasa a todo el mundo, pero el esférico se va a fuera por centímetros.

Cuando falleció Maradona fue una explosión de amores y odios, llantos y risas, todas la contradicciones posibles a flor de piel, creo también que con el deceso de Pelé se alimenta aún más el mito y sus paradojas, muere el hombre ordenado en público que igualmente tenía cierta vida alocada en privado, Xuxa como una de sus antiguas parejas sabe de aquello, el hijo exfutbolista en la cárcel por malversación de fondos también muestra su lado más fisurado. Una persona que era el ejemplo, por excelencia, de la meritocracia de los afrobrasileños en su país, doble valía, pero que nunca dio discursos muy incendiarios acerca de las desigualdades raciales, aunque al mismo tiempo fue amigo íntimo del rebelde Mohamed Alí y visitó a Mandela en Sudáfrica, gestos que retratan posiciones sin estridencias. Muere un mundo, perece el fútbol del siglo XX, fallece uno de los creadores del “jogo bonito”, el único tricampeón del planeta, de sonrisa fácil y humildad en cancha, con una vocación de bajo perfil y con la valentía para enfrentar de buen ánimo a esos defensas matadores como a un cáncer de colon. Un periodista brasileño aclara en una entrevista “el que murió fue Edson Arantes do Nascimento, Pelé es eterno.”

#futbol#futbol brasileño#Edson Arantes do Nascimento#Pelé#Santos Futbol Club#football#brazilian football#brazilian footballers#tricampeon mundial

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

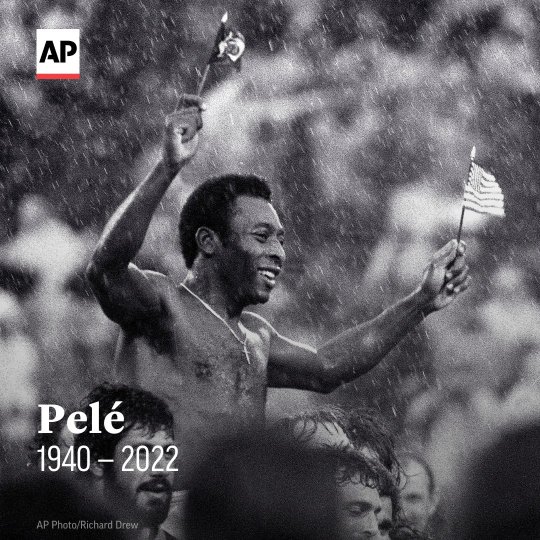

Pelé, the Global Face of Soccer, Dies at 82

Pelé, who was declared a national treasure in his native Brazil, achieved worldwide celebrity and helped popularize the sport in the United States.

Born Edson Arantes do Nascimento, Pelé was a formative 20th-century sports figure who was revered as a national treasure in his native Brazil. He was known for popularizing soccer in the United States, and citing it as a tool for connecting people worldwide.CreditCredit...Associated Press

By Lawrie Mifflin

Dec. 29, 2022

Pelé, one of soccer’s greatest players and a transformative figure in 20th-century sports who achieved a level of global celebrity few athletes have known, died on Thursday in São Paulo. He was 82.

His death was confirmed by his manager, Joe Fraga. The Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein in São Paulo said the cause was multiple organ failure, the result of the progression of colon cancer.

Pelé had been receiving treatment for cancer in recent years, and he entered the hospital several weeks ago for treatment of a variety of health issues, including a respiratory infection.

A national hero in his native Brazil, Pelé was beloved around the world — by the very poor, among whom he was raised; the very rich, in whose circles he traveled; and just about everyone who ever saw him play.

“Pelé is one of the few who contradicted my theory,” Andy Warhol once said. “Instead of 15 minutes of fame, he will have 15 centuries.”

Celebrated for his peerless talent and originality on the field, Pelé (pronounced peh-LAY) also endeared himself to fans with his sunny personality and his belief in the power of soccer — football to most of the world — to connect people across dividing lines of race, class and nationality.

He won three World Cup tournaments with Brazil and 10 league titles with Santos, his club team, as well as the 1977 North American Soccer League championship with the New York Cosmos. Having come out of retirement at 34, he spent three seasons with the Cosmos on a crusade to popularize soccer in the United States.

Before his final game, in October 1977 at Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J., Pelé took the microphone on a podium at the center of the field, his father and Muhammad Ali beside him, and exhorted a crowd of more than 75,000.

“Say with me three times now,” he declared, “for the kids: Love! Love! Love!”

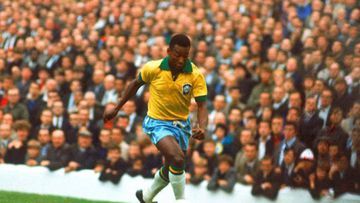

Pelé kicks a ball over his head in 1968 in an acrobatic move. Off-balance or not, he could lash the ball accurately with either foot.Credit...Associated Press

In his 21-year career, Pelé — born Edson Arantes do Nascimento — scored 1,283 goals in 1,367 professional matches, including 77 goals for the Brazilian national team.

Many of those goals became legendary, but Pelé’s influence on the sport went well beyond scoring. He helped create and promote what he later called “o jogo bonito” — the beautiful game — a style that valued clever ball control, inventive pinpoint passing and a voracious appetite for attacking. Pelé not only played it better than anyone; he also championed it around the world.

Among his athletic assets was a remarkable center of gravity; as he ran, swerved, sprinted or backpedaled, his midriff seemed never to move, while his hips and his upper body swiveled around it.

He could accelerate, decelerate or pivot in a flash. Off-balance or not, he could lash the ball accurately with either foot. Relatively small, at 5 feet 8 inches, he could nevertheless leap exceptionally high, often seeming to hang in the air to put power behind a header.

Like other sports, soccer has evolved. Today, many of its stars can execute acrobatic shots or rapid-fire passing sequences. But in his day, Pelé’s playmaking and scoring skills were stunning.

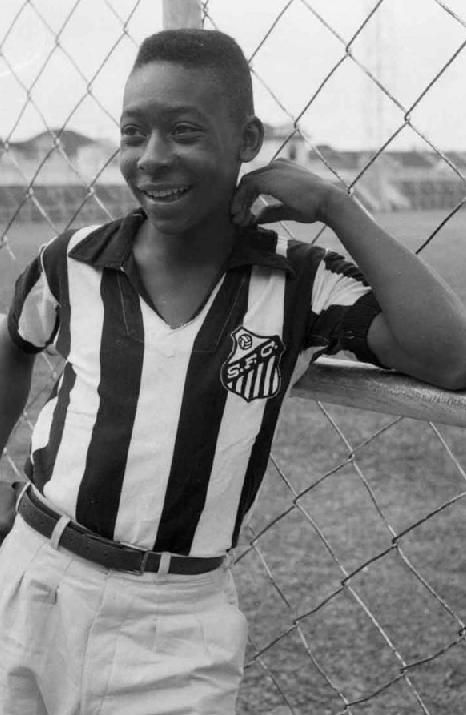

Early Success

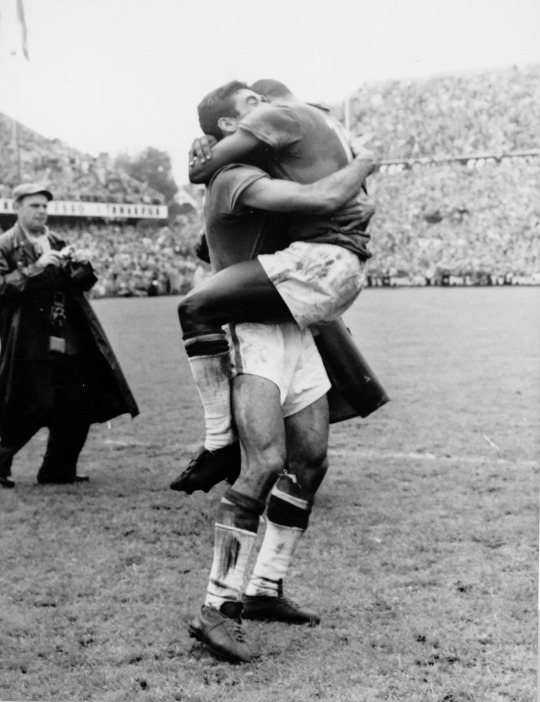

Pelé sprang into the international limelight at the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, a slight 17-year-old who as a boy had played soccer barefoot on the streets of his impoverished village using rolled-up rags for a ball. A star for Brazil, he scored six goals in the tournament, including three in a semifinal against France and two in the final, a 5-2 victory over Sweden. It was Brazil’s first of a record five World Cup trophies.

Pelé also played on the Brazilian teams that won in 1962 and 1970. In the 1966 tournament, in England, he was brutally kicked in the early games and was finally sidelined by a Portuguese player’s tackle that would have earned an expulsion nowadays but drew nothing then.

With Pelé essentially absent, Brazil was eliminated in the opening round. He was so disheartened that he announced he would retire from national team play.

But he reconsidered and played on Brazil’s World Cup team in Mexico in 1970. That team is widely hailed as the best ever; its captain, Carlos Alberto, later joined Pelé on the Cosmos.

“I wish he had gone on playing forever,” Clive Toye, a former president and general manager of the Cosmos, wrote in a 2006 memoir. “But then, so does everyone else who saw him play, and those football people who never saw him play are the unluckiest people in the world.”

Pelé, right, hugging a teammate in 1958 after Brazil defeated Sweden 5-2 to win the World Cup. Credit... Associated Press/Reportagebild

Edson Arantes do Nascimento was born on Oct. 23, 1940, in Três Corações, a tiny rural town in the state of Minas Gerais. His parents named him Edson in tribute to Thomas Edison. (Electricity had come to the town shortly before Pelé was born.) When he was about 7, he began shining shoes at the local railway station to supplement the family’s income.

His father, a professional player whose career was cut short by injury, was nicknamed Dondinho.

Brazilian soccer players often use a single name professionally, but even Pelé himself was unsure how he got his. He offered several possible derivations in “Pelé: The Autobiography” (2006, with Orlando Duarte and Alex Bellos).

Most probably, he wrote, the nickname was a reference to a player on his father’s team whom he had admired and wanted to emulate as a boy. The player was known as Bilé (bee-LAY). Other boys teased Edson, calling him Bilé until it stuck.

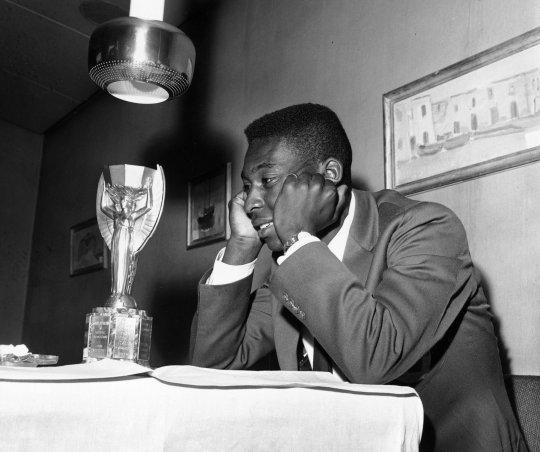

One of Pelé’s earliest memories was of seeing his father, while listening to the radio, cry when Brazil lost to Uruguay, 2-1, in the deciding match of the 1950 World Cup in Rio de Janeiro. The game is still remembered as a national calamity. Pelé recalled telling his father that he would one day grow up to win the World Cup for Brazil.

He signed his first contract, with a junior team, when he was 14 and transferred to Santos at 15. He scored four goals in his first professional game, which Santos won, 7-1. He was only 16 when he made his debut for the national team in July 1957.

A New Way to Play

When Brazil’s team went to the World Cup in Sweden the next summer, Pelé later said, he was so skinny that “quite a few people thought I was the mascot.”

Once they saw him play, it was a different story. Reports of this precocious Brazilian teenager’s prowess raced around the world. One account told of how, against Wales in the quarterfinals, with his back to the goal, he received the ball on his chest, let it drop to an ankle and instantly scooped it around behind him. As it bounced, he turned — so quickly that the ball was barely a foot off the ground — and struck it into the net. It was his first World Cup goal and the game’s only one, and it put Brazil into the semifinals.

“It boosted my confidence completely,” he wrote in his autobiography. “The world now knew about Pelé.”

Pelé in his debut game in 1975 with the New York Cosmos at Randalls Island Stadium. Credit... Barton Silverman/The New York Times

The world now knew about Brazilian soccer, too. Pelé undoubtedly benefited from playing alongside other remarkably gifted ball-control artists — Garrincha, Didi and Vavá among them — as well as from Europe’s lack of familiarity with the Brazilian style.

Most European teams used static alignments; players seldom strayed from their designated areas.

Brazil, though, encouraged two of the four midfielders to behave like wingers when attacking. This forced opponents to cope quickly with four forwards, rather than two. Making things more difficult, the forwards often switched sides, right and left, and the outside fullbacks sometimes joined the attack. The effect dazzled onlookers, not to mention opponents.

After the semifinal against France, in which Pelé scored a hat trick in a 5-2 Brazil win, the French goalkeeper reportedly said, “I would rather play against 10 Germans than one Brazilian.”

The team went home to national acclaim, and Pelé resumed playing for Santos as well as for two Army teams as part of his mandatory military service. In 1959 alone, he endured a relentless schedule of 103 competitive matches; nine times, he played two games within 24 hours.

Santos began to capitalize on his fame with lucrative postseason tours. In 1960, en route to Egypt, the team’s plane stopped in Beirut, where a crowd gathered threatening to kidnap Pelé unless Santos agreed to play a Lebanese team.

“Fortunately, the police dealt with it firmly, and we flew on to Egypt,” Pelé wrote in his autobiography.

He had become such a hero that, in 1961, to ward off European teams eager to buy his contract rights, the Brazilian government passed a resolution declaring him a nonexportable national treasure.

Soccer Diplomacy

When Pelé was about to retire from Santos in the early 1970s, Henry A. Kissinger, the United States secretary of state at the time, wrote to the Brazilian government asking it to release Pelé to play in the United States as a way to help promote soccer, and Brazil, in America.

By then, two more World Cups, numerous international club competitions and tireless touring by Santos had made Pelé a global celebrity. So it was beyond quixotic when Toye, the Cosmos’ general manager, decided to try to persuade the player universally acclaimed as the world’s best, and highest paid, to join his team.

The Cosmos had been born only a month earlier, in one afternoon, when all the players had gathered in a hotel at Kennedy International Airport to sign an agreement to play for $75 a game in a country where soccer was a minor sport at best.

Toye first met with Pelé and Julio Mazzei, Pelé’s longtime friend and mentor, in February 1971 during a Santos tour in Jamaica. It took dozens more conversations over the next four years, as well as millions of dollars from Warner Communications, the team’s owner, for Pelé to join the Cosmos.

During that period, he became the top scorer in Brazil for the 11th time, Santos won the 10th league championship of his tenure, and Pelé took heavy criticism for retiring from the national team and refusing to play in the 1974 World Cup, in West Germany.

Toye made his last pitch in March 1975 in Brussels. Pelé had retired from Santos the previous October, and two major clubs, Real Madrid of Spain and Juventus of Italy, were each offering a deal worth $15 million, Pelé later recalled.

“Sign for them, and all you can win is a championship,” Toye said he told Pelé. “Sign for me, and you can win a country.”

To further entice him, Warner added a music deal, a marketing deal guaranteeing him 50 percent of any licensing revenue involving his name, and a guarantee to hire his friend Mazzei as an assistant coach. Pelé signed a three-year contract worth, according to various estimates, $2.8 million to $7 million (the latter equivalent to about $40 million today).

Clive Toye, the general manager of the Cosmos, with Pelé after the soccer star signed with the team in 1975. Credit... Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times

He was presented to the news media on June 11, 1975, at the “21” Club in New York. Pandemonium ensued: Fistfights broke out among photographers, and tables collapsed when people stood on them.

The hubbub continued when Pelé played his first North American Soccer League game, on June 15 at Downing Stadium on Randalls Island in the East River. It was a decrepit home; workers hastily painted its dirt patches green because CBS had come to televise the big debut. More than 18,000 fans, triple the previous largest crowd, shouldered their way in to watch.

At every road game during Pelé’s three North American seasons, the Cosmos attracted enormous crowds and a press contingent larger than that of any other New York team, with many journalists representing foreign networks, newspapers and news agencies. Movie and music stars — including Mick Jagger, Robert Redford and Rod Stewart — showed up for home games, lured by Warner executives’ enthusiasm for their hot new talent.

The Cosmos moved to Giants Stadium in Pelé’s final season, 1977, and there, in the Meadowlands, reached the pinnacle of their — and the league’s — popularity. For a home playoff game on Aug. 14, a crowd of 77,691 exceeded not only expectations but also capacity, squeezing into a stadium of 76,000 seats.

That season, the Cosmos had added two more global superstars, Franz Beckenbauer of West Germany and Carlos Alberto of Brazil. (Later, in 1979, the Los Angeles Aztecs lured a third, Johan Cruyff of the Netherlands, to the league.) Soccer seemed poised to enter the American mainstream.

But as it turned out, professional soccer was not yet ready to blossom in America, not even after the Cosmos won the 1977 league championship, in Seattle, or after Pelé’s festive farewell game in October, when he led the “Love!” chant and played one half for the Cosmos and the other half for the visiting team, his beloved Santos.

The league had expanded to 24 teams, from 18, and lacked the financial underpinnings to sustain that many games and that much travel. Nor could other teams match the Cosmos’ spending on top-quality players. The league went out of business after the 1984 season.

But at the grass-roots level, and in schools and colleges, soccer did take off. In 1991, the United States women’s national team won the first women’s World Cup. (The United States has won it three times since.) In 2002, the men’s national team made it to the quarterfinals of the World Cup. And Major League Soccer has established itself as a sturdy successor to the N.A.S.L. (In 2011, the inaugural season of a new minor league with the N.A.S.L. name included a New York Cosmos team, of which Pelé was named honorary president.)

In June 2014, the city of Santos opened a Pelé Museum just before the start of the World Cup, the first held in Brazil since 1950. In a video recorded for the occasion, Pelé said, “It’s a great joy to pass through this world and be able to leave, for future generations, some memories, and to leave a legacy for my country.”

Advocate for Education

Pelé met Rosemeri Cholbi when she was 14 and wooed her for almost eight years before they married early in 1966. They had three children — Kelly Cristina, Edson Cholbi and Jennifer — before divorcing in 1982.

After his divorce, Pelé often appeared in the gossip pages, partying with film stars, musicians and models. He acted in several movies, including John Huston’s “Victory” (1981), with Michael Caine and Sylvester Stallone.

It also emerged that he had fathered two daughters out of wedlock. One, Sandra, whom he had refused to acknowledge, later sued for the right to use his surname. She wrote a book, “The Daughter the King Didn’t Want,” which he said greatly embarrassed him. She died of cancer in 2006.

His son, nicknamed Edinho, was a professional goalkeeper for five years before an injury ended his career. He later went to prison on a drug-trafficking conviction.

In 1994, Pelé married Assiria Seixas Lemos, a psychologist and Brazilian gospel singer; their twins, Joshua and Celeste, were born in 1996. They divorced in 2008. In his later years he dated a Brazilian businesswoman, Marcia Aoki, and he married her in 2016.

Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

His brother Jair Arantes do Nascimento, who was known as Zoca and also played for Santos, died in 2020.

Children always responded warmly to Pelé, and he to them. Neither big nor intimidating, he had a wide, easy smile and a deep, reassuring voice.

“I have never seen another human being who was so willing to take the extra second to embrace or encourage a child,” said Jim Trecker, a longtime soccer executive who was the Cosmos’ public relations director in the Pelé years.

Pelé greeting children during the inauguration of a soccer pitch in Rio de Janeiro in 2014. Credit... Silvia Izquierdo/AP

Pelé was sensitive about having dropped out of school (he later earned a high school diploma and a college degree while playing for Santos) and often lamented that so many young Brazilians remained poor and illiterate even as the country had begun to prosper.

Indeed, the day he scored his 1,000th goal, in November 1969 at Maracanã stadium in Rio before more than 200,000 fans, Pelé was mobbed by reporters on the field and used their microphones to dedicate the goal to “the children.” Crying, he made an impromptu speech about the difficulties of Brazil’s children and the need to give them better educational opportunities.

Many journalists interpreted the gesture as grandstanding, but for decades, as if to correct the record, he cited that speech and repeated the sentiment. In July 2007, at a promotional event in New York for a family literacy campaign, he said, “Today, the violence we see in Brazil, the corruption in Brazil, is causing big, big problems. Because, you see, for two generations, the children did not get enough education.”

(On the subject of correcting the record, research for his 2006 biography turned up additional games played, and the authors concluded that the famous 1,000th goal was actually his 1,002nd.)

In London during the 2012 Olympics, Pelé joined a so-called hunger summit meeting convened by the British prime minister at the time, David Cameron, whose stated goal was to reduce by 25 million the number of children stunted by malnutrition before the Rio Olympics in 2016.

Business and Music

Pelé’s own venture into government began in 1995, when he was appointed Brazil’s minister for sport by then-President Fernando Henrique Cardoso. Pelé began a crusade to bring accountability to the business operations of Brazil’s professional teams, which were still run largely as gentlemen’s clubs, and to reform rules governing players’ contracts.

In 1998, Pelé’s Law, as it was known, passed. It required clubs to incorporate as taxable for-profit corporations and to publish balance sheets. It required that players be 20 before signing a professional contract and gave them the right of free agency after two years (instead of after age 32).

Many of the provisions were later weakened, and corruption continued, but Pelé said he took pride that the free agency clause had survived.

Business deals gone awry plagued him throughout his life.

He himself said he was often gullible, trusting friends who were less competent than they appeared. In 2001, a company he had helped found a decade earlier, Pelé Sports and Marketing, was accused of taking enormous loans to stage a charity game for Unicef and then not repaying the money when the game failed to happen. Pelé shut down the company; Unicef said there had been no wrongdoing on his part.

While continuing to promote educational programs throughout his life, Pelé also pursued his musical avocation. He was never far from a guitar, and he carried a miniature tape recorder to capture tunes or lyrics as the mood struck him.

He composed dozens of songs that were recorded by Brazilian pop stars, usually without his taking credit.

Pelé relaxing during the World Cup in Mexico in 1970. Pursuing a musical avocation, he was never far from a guitar. Credit... Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos, via Getty Images

“I didn’t want the public to make the comparison between Pelé the composer and Pelé the football player,” he told the British newspaper The Guardian in 2006. “That would have been a huge injustice. In football, my talent was a gift from God. Music was just for fun.”

As he grew older, he often spoke of the difficulty of distinguishing between two personas: his real self, and the soccer superstar Pelé. He often referred to Pelé in the third person.

“One of the ways I try to keep perspective on things,” he wrote in his autobiography, “is to remind myself that what people are responding to isn’t me, necessarily; it’s this mythical figure that Pelé has become.”

His face remained familiar around the world long after his retirement from soccer. In 1994, when the World Cup was about to be played in the United States, Pelé sat in Central Park in New York waiting to be interviewed for ABC News. A teenager passed, did a double-take and then ran off; within minutes, people were streaming across the park to see him.

“There were hundreds of them,” Toye wrote in his own memoir. “Seventeen years after he last kicked a ball, this dark-skinned man is sitting in deep, dark shade under the trees — but he is still recognized, and once recognized, never alone in any country on earth.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Rei Pelé Gols e Dribles "The King"

#youtube#pelé#rei pelé#pelé 10#pelé santos#santos#pelé cosmos#seleção brasileira#copa 70#tricampeão do mundo#brasil#fifa 23#rei do futebol#the king pelé

0 notes

Text

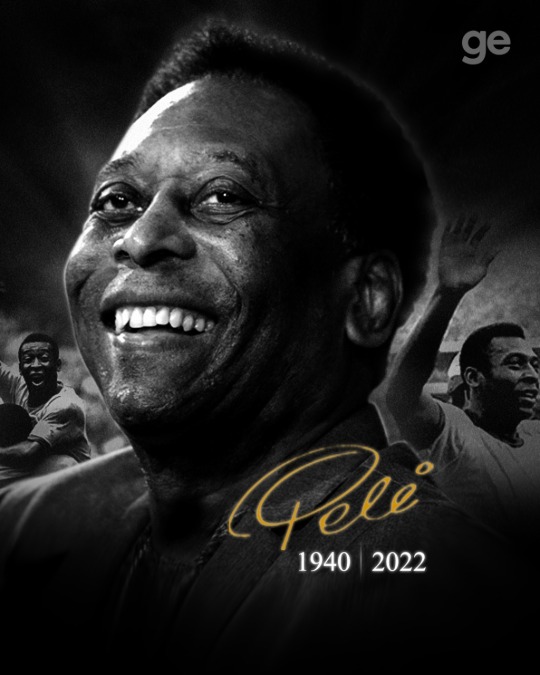

Obrigado Pelé

A imortalidade é um dom dos gênios e faltam palavras para descrever a grandeza de Pelé

O tal futebol se divide entre Antes de Pelé e Pós Pelé.

Este esporte doido e apaixonante, como disse Arrigo Sachi: A coisa mais importante entre todas as coisas não importantes, só é o que é devido a você.

Ninguém se compara a ti, mas todos querem se comparar a você.

Até seus erros, tornaram-se…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Um dos motivos, se não for um dos primeiros, a dar orgulho no esporte no Brasil. Independente de qualquer coisa, obrigada Pelé! Futebol é o nosso sobrenome graças a sua graça maravilhosa de jogar!! Culpado por todos quererem ser camisa 10. Tomara que muitos continue te imitando!

Brasil e mundo diz: Obrigada!

Vida longa ao rei do futebol! Pelé, Camisa 10!

Meus sentimentos. 🙏🏾

#gcik santana#jessica santana#jessica s#pelé#pele#futebol#in memoriam#futebol brasileiro#santos#seleção#seleção brasileira#frase do dia#luto#luto famosos#luto futebol#copa#rei#rei pele#rei pelé

0 notes

Photo

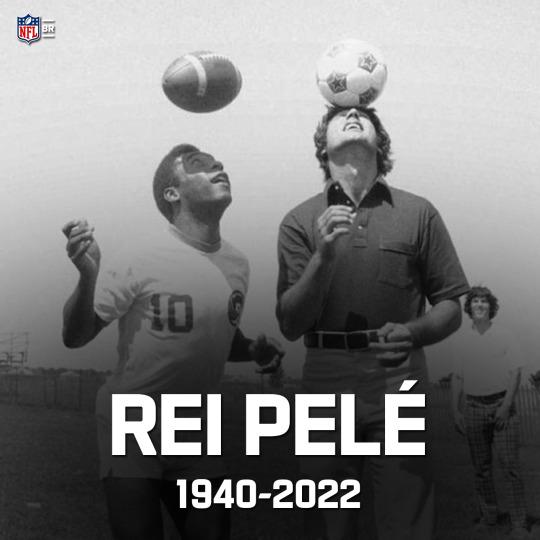

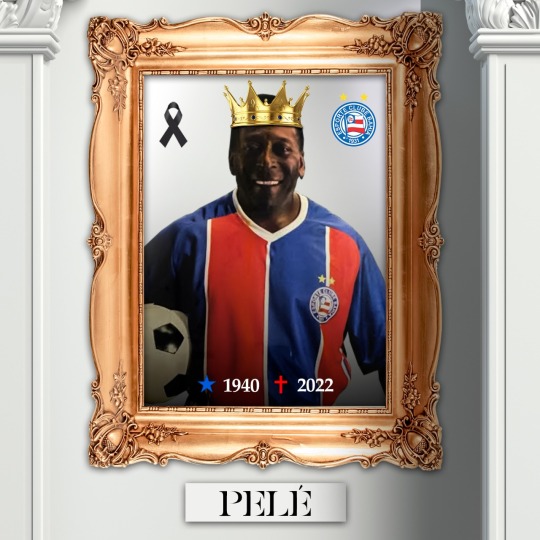

RIP Pelé (October 23, 1940 – December 29, 2022)

Pelé (born Edson Arantes do Nascimento), the Brazilian soccer legend who won three World Cups and became the sport’s first global icon, has died at the age of 82 from complications related to colon cancer.

For more than 60 years, the name Pelé has been synonymous with soccer. He played in four World Cups and is the only player in history to win three, but his legacy stretched far beyond his trophy haul and remarkable goal-scoring record.

“I was born to play football, just like Beethoven was born to write music and Michelangelo was born to paint,” He once said.

Averaging almost a goal per game throughout his career, Pelé was adept at striking the ball with either foot in addition to anticipating his opponents' movements on the field. His dribbling skills were on a higher level, and the best and most experienced defenses were rarely able to stop him. In all, Pele's pro career totaled 1,280 goals (a Guinness world record) and he scored 77 goals for Brasil in World Cup games, also a record.

He won many titles with his Brazilian club, Santos FC, and is their all-time goals leader. He also represented Brasil in four World Cups starting at the age of 17, winning in 1958, 1962, and 1970. FIFA then dubbed him simply, “The Greatest”; Brazilians called him O Rei (”The King”).

After retiring from Brazilian (and International World Cup Play) soccer in 1974, he signed on with the New York Cosmos and wowed American fans for three years. Pelé finished his official playing career by leading the Cosmos to their second championship in 1977. He then enjoyed his international celebrity status, including a starring role in the film “Victory”, shown above.

#football#legend#Pele#bicycle kick#goal#gif#1981#futbol#futsal#the beautiful game#Copa Libertadores#Intercontinental cup

429 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wes Anderson Movies + Tv tropes part 4/12

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou edition

#wes anderson#the life aquatic with steve zissou#bill murray#owen wilson#anjelica huston#cate blanchett#willem dafoe#jeff goldblum#seu jorge#steve zissou#ned plimpton#Eleanor Zissou#jane Winslett-Richardson#klaus daimler#Alistair hennessey#pelé dos santos#tv tropes#shut up pretty boy

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

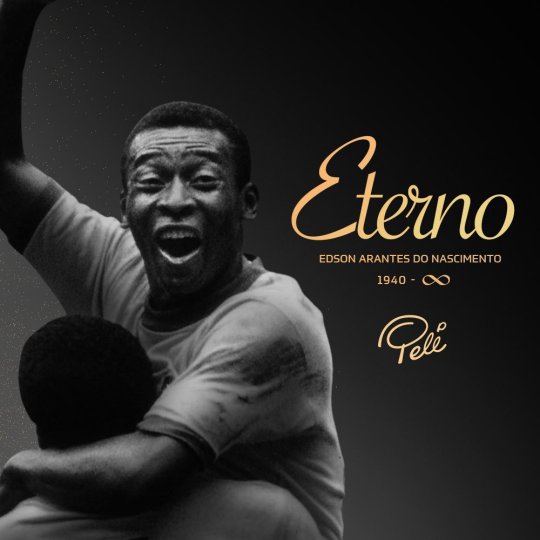

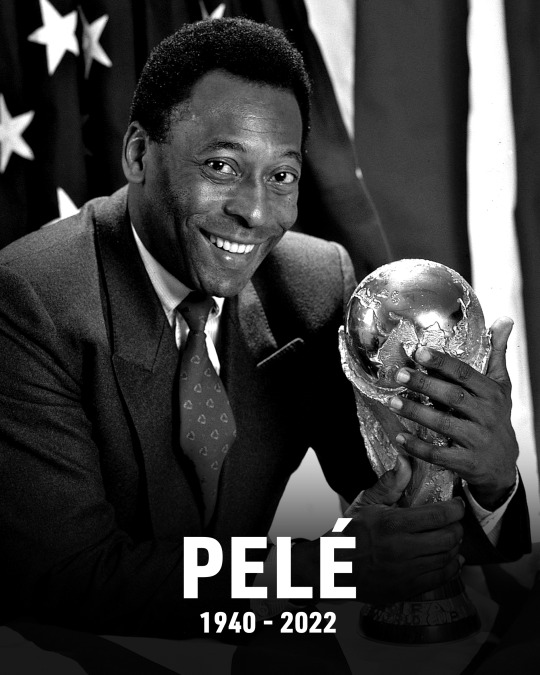

Brazilian soccer legend Pelé has passed away at age 82 due to complications from colon cancer.

Pelé began playing for Santos at age 15 and the Brazil national team at 16. During his international career, he won three FIFA World Cups: 1958, 1962 and 1970, the only player to do so. With 77 goals in 92 official appearances, Pelé is the joint-top scorer of the Brazil national soccer team alongside Neymar. He became a global soccer ambassador after retiring in 1977.

366 notes

·

View notes

Text

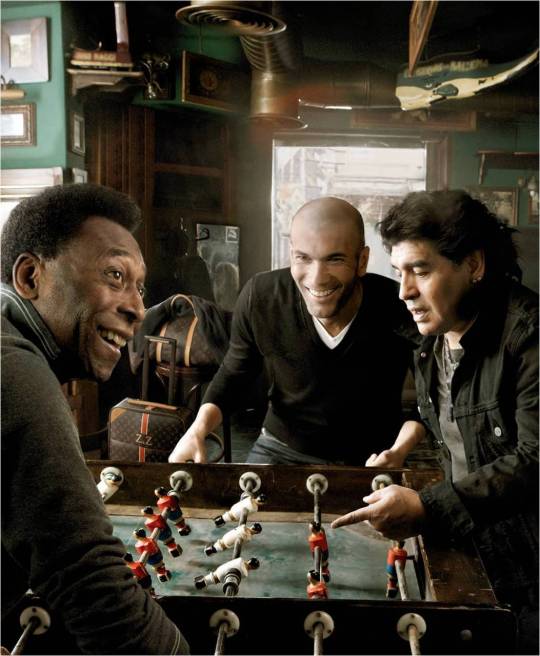

Louis Vuitton FC by Annie Leibovitz

#edson arantes do nascimento#Pelé#Diego Armando Maradona Franco#diego armando maradona#Diego Maradona#Maradona#Zinedine Yazid Zidane#zinedine zidane#Zidane#Zizou#Lionel Andrés Messi Cuccittini#Lionel Messi#Leo Messi#Messi#Cristiano Ronaldo dos Santos Aveiro#Cristiano Ronaldo#CR7#Louis Vuitton#Annie Leibovitz#football#fussball#fußball#foot#fodbod#futbol#futebol#soccer#calcio

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

NCT é de "tal" time...

Part.1

Jaehyun / Johnny são aqueles flamenguistas chatos. Em qualquer discussão sobre futebol da pra sentir aquele quê' de superioridade e joga a copa da libertadores de argumento pra tudo. Johnny rasga a camisa de emoção e perde a cabeça todo jogo, quase infarta. Além disso, é socio torcedor, faz coleção das camisas e quer obrigar todos da família serem flamenguistas. Já Jaehyun, sempre começava o papinho de "não sou muito ligado no futebol.." e dez minutos depois estaria falando sobre as devidas contratações do time citando um repertório longo e monótono sobre os principais treinadores e suas façanhas na história do clube.

Ten torce para São Paulo, sua mãe o levava sempre aos jogos desde pequeno e quando cresce acaba desenvolvendo o hábito como uma programação da família sagrado - tipo almoço de domingo -.

Haechan é Corintiano de coração. Toca na bateria da torcida organizada e tem uma tatuagem do brasão do Corinthians na panturrilha e uma da torcida jovem nas costas.

As vezes parece que Mark Lee e taeyong venderam a alma ao Vasco da gama. Mark vive passando mal a cada jogo e sempre jura a cada derrota de pé junto que nunca mais vai ver o vasco, só para na próxima partida quebrar a promessa e apostar uma baita grana no jogo, ir assistir no São Januario, perder e gritar "Porque Deus odeia o Vasco?!".

Taeyong, pelo contrário, só vê o resumo da partida e nem se tortura vendo o jogo. O máximo que faz é escrever o nome do técnico do Vasco no caderninho de oração da universal toda vez que tem chance.

Chenle torce para o fluminense por uma questão familiar, porque ele não assiste um jogo sequer e por isso, o pai dele lamenta por não ter criado um tricolor que se preze pois o filho acha os jogos uma coisa impertinente, perca de tempo e uma babaquice vergonhosa.

Yuta é Botafogo doente. Leva os sobrinho pra assistir o jogo, participa de todos os eventos do botafogo e sua casa parece um mini museo de experiências botafoguence.

Jaemin é tricolor maluco, inteiramente surtado pelo fluminense. Grita até em amistoso, tá ligado até no jogo do grupo sub. Torce o nariz todas vez que vê chenle "tricolor minha piroca, flamenguista sabe mais de fluminense que esse aí " Faz o L pra tudo e falta beijar tv quando o German cano faz gol.

Jisung é flamenguista contido, aqueles que a gente só descobre o time em dia de jogo importante quando ele posta alguma coisa.

Shotaro torce para o Santos. E sua justifica para tudo é a participação de Pelé e neymar em seu clube.

#nct brasil#ptbr#xuxu pensamentos#brazilian culture#fluminense#flamengo#vasco#vasco da gama#tricolor#corinthians#nctbr

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today In History

In 1940, in Tres Coracoes, in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, Edson Arantes do Nascimento, generally known as Pelé, is born October 23, 1940.

After Brazil lost the 1950 World Cup final to Uruguay, a 9 or 10-year-old Pelé, made a promise to his devastated father. “I remember jokingly saying to him: ‘Don’t cry, dad — I’ll win the World Cup for you,” Pelé recalled to FIFA.com in 2014. Eight years in 1958 later, however, his so-called joke became a reality when he won the first of his record-breaking three World Cup titles.

Thus began Pelé’s storied career, and by the time he played his final professional game in 1977, he’d netted over 1,280 career goals as part of Brazil’s Santos Football Club and the New York Cosmos. Although he’s now widely considered to be the greatest soccer player of all time.

CARTER™️ Magazine

#carter magazine#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#history#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#carter#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#pele

52 notes

·

View notes