#Pi-Ramesses

Photo

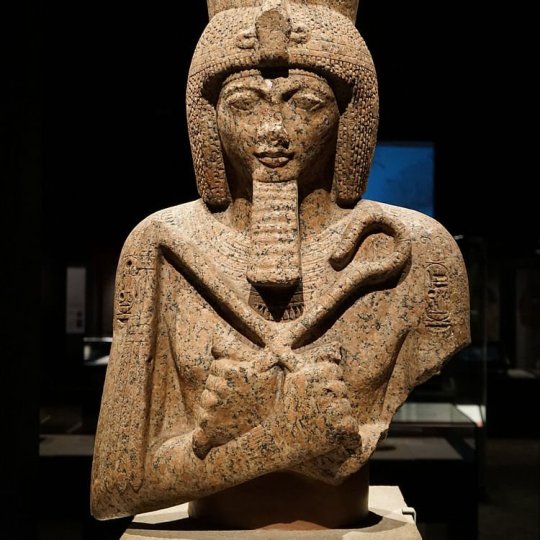

Qadech

Qadech (alias Qadesh ou Kedech) était une ville de la région de Syrie et un important centre de commerce dans le monde antique. Elle est probablement mieux connue comme le site de la célèbre bataille entre le pharaon Ramsès II (Le Grand, 1279-1213 av. J.-C.) d'Égypte et le roi Muwatalli II (1295-1272 av. J.-C.) de l'Empire hittite en 1274 avant notre ère.

Lire la suite...

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pi-Ramsés

Pi-Ramsés (también conocida como Per-Rameses, Piramese, Pr-Rameses, Pir-Ramaseu) fue una ciudad construida como una nueva capital en la región del Delta del antiguo Egipto, por Ramsés II (conocido como "el Grande", 1279-1213 a.C.). Estaba ubicada en el sitio del actual pueblo de Qantir en el Delta Oriental y en su tiempo fue considerada la ciudad más grande de Egipto, compitiendo incluso con Tebas, en el Sur. El nombre significa "La Casa de Ramsés" (también "Ciudad de Ramsés") y fue construida cerca de la antigua ciudad de Avaris.

Leer más...

0 notes

Text

In 1940 a famous French Egyptologist discovered a dozen royal tombs near the ancient city of Tanis. Was this evidence of Pi-Ramesses, Egypt’s legendary lost capital?

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Documentary about the third pharaoh of the Twenty-First Dynasty, Psusennes I, and the search for the city of Pi-Ramesses.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Egyptian Queen Nefertari (d. 1255 BC) catches the balmy rays of the African sun as it sets to the west of the delta city of Pi-Ramesses. In the ancient Egyptian language, Nefertari’s translates to “the most beautiful one”, with nefer– being the word for beauty.

#nefertari#ancient egypt#egyptian#kemet#african#queen#black woman#woman of color#woc#dark skin#digital art#art

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listening to an older talk my Manfred Bietak and the sentence "Pi-Ramesses was here" was spoke and I immediately got an image of a young Ramesses starting his monument theft career by hiding while writing "Ramesses was here" in the corners of various temples. Probably with a tongue stuck out of his mouth as he tries to remember how to actually write it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think Moses really expected to see Seti here (You've been gone for a decade and he was already a geriatric old man!)

Nefertari! How not relevant to this movie you are! What with being Ramesses great royal wife!

People have pointed out that this is a different palace complex than the one Seti inhabited, which, I mean, Ramesses II did move the capital of Egypt to the river delta; they're probably in Pi-Ramesses right now

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Through his eyes, you feel as if you’ve traveled across millenniums. Flying over the beautiful Nile to reunite with your beloved Amon.

Oaths engraved in stone monuments, lasting for thousands of years, yet the romance within remains unchanged.

His purple eyes quietly gaze upon you, making you feel as if you were in the great palace of Pi-Ramesses.

The king sits on the throne, silently conveying his overwhelming love for you through his passionate gaze.

Whether it be the past, present, or future: only one person can stand with him as an equal, forever cherished in his heart.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

King Ramses II: The Great Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt"

Ramses II, known as Ramses the Great, stands as one of the most celebrated and powerful pharaohs in the rich tapestry of ancient Egyptian history. His enduring significance in ancient Egypt is a testament to his exceptional 66-year reign during the 19th dynasty of the New Kingdom. Ramses II's remarkable legacy transcends the sands of time, marked by his military conquests, ambitious building projects, and an indomitable spirit that left an indelible mark on the pages of history. In this blog, we delve into the life, achievements, and enduring influence of the great ruler Ramses II, a name that resonates through millennia.

Early Life and Ascension

Ramses II's early life and his path to the throne are shrouded in the fascinating intrigues of ancient Egypt's royal lineage. Born around 1303 BC, Ramses II was the son of Seti I and Queen Tuya. His early years were spent amidst the grandeur of the Egyptian court, where he received a comprehensive education in the arts, literature, and the intricacies of statecraft.

His ascent to the throne came about in a manner that was not uncommon for ancient Egyptian royalty. Seti I, his father, had been a formidable pharaoh in his own right. Seti I ruled Egypt for around a decade and was known for his military campaigns and building projects. When he passed away, Ramses II, at a relatively young age, assumed the throne of the Egyptian kingdom.

This transition of power marked the beginning of Ramses II's impressive reign, one that would span over six decades. It is worth noting that while his succession to the throne was somewhat conventional, Ramses II's extraordinary leadership and enduring impact on Egypt and the ancient world would set him apart as one of the greatest pharaohs in history.

Achievements and Reign

During his remarkable reign of 66 years, Ramses II achieved a plethora of feats that left an indelible mark on ancient Egypt's history. His accomplishments spanned military conquests, monumental building projects, and shrewd diplomatic relations, solidifying his legacy as one of Egypt's greatest pharaohs.

1. Military Conquests:

The Battle of Kadesh: Ramses II's most famous military campaign was the Battle of Kadesh, fought against the Hittites in 1274 BC. Although it ended in a stalemate, Ramses II's accounts of the battle, inscribed on temple walls, provide valuable historical insights.

Expansion of Egypt: Ramses II conducted numerous military campaigns to expand the Egyptian empire, including campaigns in Nubia and the Levant. His reign was marked by efforts to secure Egypt's borders and protect its interests.

2. Building Projects:

Temple of Abu Simbel: One of his most iconic achievements was the construction of the Temple of Abu Simbel. Carved into the rock face, this massive temple complex was dedicated to the gods Amun, Ra-Horakhty, and Ptah and featured colossal statues of Ramses II himself.

The Ramesseum: Ramses II built the Ramesseum, a mortuary temple on the west bank of the Nile in Thebes, which served as a grand memorial for the pharaoh and his reign.

Pi-Ramesses: He founded a city, Pi-Ramesses, which would later become a prominent center during the reign of his successors.

3. Diplomatic Relations:

The First Recorded Peace Treaty: Ramses II is known for his diplomatic prowess, which led to the earliest recorded peace treaty in history, the Treaty of Kadesh, signed with the Hittites after the Battle of Kadesh.

Marriage Alliances: He solidified diplomatic ties by marrying several foreign princesses, including a Hittite princess, to foster alliances and strengthen international relations.

The Battle of Kadesh

The Battle of Kadesh, fought in 1274 BC, stands as one of the most famous and significant military encounters of Ramses II's reign. It took place in the vicinity of the ancient city of Kadesh, situated in modern-day Syria, and is notable for several reasons.

Context and Opponents: At the time of the Battle of Kadesh, the Hittite Empire and the Egyptian Empire, under Ramses II's rule, were competing for control of territories in the eastern Mediterranean region. The city of Kadesh was strategically important, and both powers sought to assert dominance in the area.

The Prelude: Ramses II, in pursuit of expanding Egypt's influence, led a massive campaign into the Levant. He divided his army into four divisions, with one under his direct command. However, the Hittite king, Muwatalli II, was well-informed about Ramses II's plans and had assembled his own forces near Kadesh.

The Ambush: The battle commenced with Ramses II leading his army, but he fell into a Hittite trap. Muwatalli II had concealed the majority of his troops, leading the Egyptians to believe they were facing a smaller force. In the ensuing battle, Ramses II's forces faced a sudden Hittite counterattack, resulting in chaos on the Egyptian side.

Ramses II's Heroic Stand: Despite the initial confusion and peril, Ramses II displayed remarkable valor. Accounts of the battle, notably inscribed on temple walls, describe how he fought fiercely to prevent a complete rout of his forces. His leadership and personal bravery inspired his troops.

Stalemate and Treaty: The Battle of Kadesh ultimately ended in a stalemate. Both sides suffered heavy losses, and neither could decisively claim victory. However, this military confrontation had a significant diplomatic outcome. It led to the signing of the Treaty of Kadesh, the first recorded peace treaty in history. The treaty reestablished diplomatic relations between Egypt and the Hittite Empire, securing peace in the region.

Historical Significance: The Battle of Kadesh, while not a clear-cut military triumph for Ramses II, became a cornerstone of his reign's historical documentation. The inscriptions on temple walls detailing the battle provide valuable insights into ancient Egyptian military tactics and the grandeur of Ramses II's reign. It also underscores the importance of diplomacy in maintaining geopolitical stability, as evidenced by the subsequent peace treaty.

The Battle of Kadesh, with its intricate dynamics and lasting impact, is a testament to Ramses II's resilience and influence on both the military and diplomatic fronts during his rule.

Ramses II was not only a formidable warrior but also a prolific builder, leaving an enduring legacy through monumental construction projects that showcased his grandeur and devotion to the gods. Two of his most iconic projects were the temples at Abu Simbel and the Ramesseum.

1. Temple of Abu Simbel:

Location: Located in the southern part of ancient Egypt, near the border with Nubia (modern-day Sudan), the Temple of Abu Simbel is perhaps the most famous of Ramses II's architectural marvels.

Dedication: The temple was dedicated to the gods Amun, Ra-Horakhty, and Ptah, as well as to Ramses II himself, who was deified during his lifetime.

Colossal Statues: The most striking feature of the Temple of Abu Simbel is its colossal statues. Four massive seated statues of Ramses II, each standing at approximately 66 feet tall, guard the entrance. These statues are a testament to his might and the might of Egypt.

Interior Chambers: The temple is adorned with intricately decorated interior chambers, including the Hypostyle Hall, which features stunning carvings and paintings that depict various aspects of Ramses II's reign and his divine status.

2. The Ramesseum:

Location: Situated on the west bank of the Nile in Thebes, the Ramesseum served as Ramses II's mortuary temple.

Purpose: The temple was constructed to honor Ramses II, preserve his memory, and provide a place for the pharaoh's cult worship and the offering of rituals to the gods.

Colossal Statue of Ramses II: The Ramesseum is known for a massive fallen statue of Ramses II, which is over 57 feet in length. It is made of red granite and, despite being toppled, it showcases the pharaoh's grandeur.

Reliefs and Inscriptions: The temple is richly decorated with inscriptions and reliefs that depict scenes from Ramses II's military campaigns and divine interactions.

These monumental building projects are not only a testament to Ramses II's architectural vision but also his immense ego and desire for eternal remembrance. They served not only as places of worship but also as symbols of his power and might, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape of ancient Egypt. Today, both the Temple of Abu Simbel and the Ramesseum continue to stand as magnificent monuments to a pharaoh whose legacy is etched in stone.

Family and Personal Life

Ramses II's family life was as expansive and intricate as his reign. As one of ancient Egypt's most prominent pharaohs, he maintained a complex network of marriages and family relationships that were both politically strategic and dynastically significant. Here's a glimpse into his family and personal life:

Wives and Consorts: Ramses II had several wives and consorts, reflecting the political alliances and diplomatic ties he sought to establish. Some of the most notable among them include:

Nefertari: Nefertari was one of Ramses II's most beloved queens. Their relationship was characterized by deep affection, and she held a special place in his heart. Nefertari is often depicted alongside Ramses II in various inscriptions and monuments.

Isetnofret: Isetnofret was another of Ramses II's principal wives. She bore him numerous children, including his firstborn son, Amun-her-khepeshef.

Maathorneferure: Maathorneferure was another queen of Ramses II, known for her distinctive name. She was the mother of several of his children.

Bintanath: Bintanath was one of Ramses II's daughters who held a significant role in the royal court and was married to high-ranking officials.

Children: Ramses II had a substantial number of offspring, many of whom played important roles in Egyptian society. Notable children of Ramses II include:

Amun-her-khepeshef: Ramses II's firstborn son, Amun-her-khepeshef, was intended to succeed him as pharaoh but predeceased his father.

Meritamen: Meritamen was one of Ramses II's daughters, often depicted alongside her parents in various inscriptions.

Meryatum: Meryatum, another of Ramses II's daughters, was married to her father during his lifetime, which was a common practice among Egyptian royalty to reinforce familial connections.

Khaemweset: Ramses II's fourth son, Khaemweset, was a prolific builder and the High Priest of Ptah. He played a crucial role in preserving Egypt's historical and architectural heritage.

Ramses II's family life was intricate, reflecting the complexities of ancient Egyptian royalty. Marriages were often strategic, cementing diplomatic relationships and securing dynastic succession. His devotion to certain queens, like Nefertari, was evident through inscriptions and monuments, while his children held significant positions in the court and priesthood. The family dynamics of Ramses II were intertwined with his leadership and enduring influence on ancient Egypt.

Art and Culture

Ramses II's impact on art and culture during ancient Egypt's New Kingdom period was profound. His reign saw a resurgence of artistic and architectural achievements, marked by the proliferation of statues, inscriptions, and monumental structures that celebrated his reign and divine status. Here's how Ramses II left an indelible mark on art and culture:

1. Colossal Statues:

Ramses II was renowned for the creation of colossal statues in his own image. Some of the most famous examples include the colossal statues at the entrance of the Temple of Abu Simbel, which are around 66 feet tall, and the enormous fallen statue at the Ramesseum, measuring over 57 feet in length. These statues served not only as symbols of his power but also as divine representations of the pharaoh himself.

2. Temple Inscriptions:

Ramses II's numerous construction projects, including the Temple of Abu Simbel and the Ramesseum, were adorned with intricately carved inscriptions and reliefs. These inscriptions not only chronicled his military victories and diplomatic achievements but also conveyed religious significance, emphasizing the pharaoh's divine connection.

3. Personalization of Art:

Ramses II was known for personalizing art and inscriptions. He was depicted in various roles, from a powerful military leader to a pious worshiper of the gods. This personalization showcased his multifaceted identity and grandeur.

4. Poetic and Literary Works:

Ramses II's reign saw a revival of literature and poetry, with his time often referred to as the "Ramsesian Renaissance." His inscriptions include poetic accounts of his achievements, most notably the inscriptions on the walls of the Abu Simbel temple that describe his Battle of Kadesh.

5. Historical Legacy:

Ramses II's penchant for monumental art and inscriptions served not only as a celebration of his rule but also as a means to preserve his historical legacy. His monumental structures and texts allowed future generations to remember his remarkable reign and accomplishments.

Ramses II's influence on art and culture extended beyond his lifetime. The colossal statues and inscriptions dedicated to him became iconic symbols of Egyptian pharaonic power and magnificence. His impact on art and culture during the New Kingdom era remains a testament to his enduring legacy in the annals of Egyptian history.

Legacy

Ramses II, also known as Ramses the Great, left an enduring legacy that firmly established his place in the annals of Egyptian history as one of its most celebrated and influential pharaohs. His legacy can be examined from several key perspectives:

1. Longevity and Stability:

Ramses II's reign of 66 years is one of the longest in ancient Egyptian history. This stability allowed for significant achievements and long-lasting policies, which provided continuity in governance and culture.

2. Military Achievements:

While the Battle of Kadesh ended in a stalemate, Ramses II's military campaigns across the eastern Mediterranean secured Egypt's borders, defended its interests, and showcased his strength as a leader.

3. Diplomacy and Peace Treaty:

Ramses II's diplomatic skills were demonstrated through the signing of the Treaty of Kadesh with the Hittites, marking the first recorded peace treaty in history. This treaty ensured peace in the region for many years.

4. Architectural Marvels:

His grand construction projects, such as the temples at Abu Simbel and the Ramesseum, remain iconic symbols of ancient Egyptian architectural prowess. They continue to attract visitors from around the world.

5. Literary and Artistic Revival:

Ramses II's reign is often referred to as a literary and artistic renaissance, with a resurgence of inscriptions, poetry, and literature that celebrated his rule and achievements.

6. Family and Dynastic Succession:

Ramses II's family life, with numerous children and marital alliances, secured the continuation of the 19th dynasty, contributing to Egypt's dynastic stability.

7. Cultural Impact:

His impact on art, culture, and religion had a lasting influence on the course of Egyptian history. He was often depicted as a model of pharaonic power and piety in art and inscriptions.

8. Historical Documentation:

Ramses II's penchant for monumental inscriptions and records served as invaluable historical documentation, providing insights into his era, including the Battle of Kadesh and diplomatic affairs.

Ramses II's enduring legacy is not confined to the annals of Egypt alone. He remains a symbol of ancient Egypt's grandeur and strength, revered not only by his contemporaries but also by historians, archaeologists, and tourists who continue to be captivated by his monumental achievements. Ramses II's place in Egyptian history is that of a ruler who left an indelible mark through his remarkable reign, military prowess, diplomatic acumen, and profound cultural contributions.

Funerary Practices

Ramses II's funerary practices and tomb were befitting a pharaoh of his stature, emphasizing his divine status and the importance of the afterlife. His final resting place, like his life, was marked by grandeur and meticulous attention to detail.

1. Tomb Location:

Ramses II's tomb, known as the KV7 tomb, is located in the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of the Nile near Luxor. This valley served as the burial ground for many Egyptian pharaohs.

2. The Design:

The tomb is adorned with a long corridor leading to a series of chambers. This design reflects the traditional layout of pharaonic tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

3. Decorations and Inscriptions:

The tomb features richly decorated walls with inscriptions and reliefs that depict scenes from the pharaoh's life, including his military victories, religious rituals, and interactions with the gods. These inscriptions are meant to guide Ramses II in the afterlife.

4. Sarcophagus:

The innermost chamber of the tomb houses Ramses II's sarcophagus, where his mummy was laid to rest. The sarcophagus was typically made of stone, symbolizing the eternal nature of the pharaoh's soul.

5. Burial Treasures:

Like many pharaohs, Ramses II was buried with a wealth of funerary treasures, including jewelry, pottery, and other items believed to be useful in the afterlife.

6. Continuing Worship:

Ramses II was deified during his lifetime, and his tomb served as a place of continued worship by his descendants and devotees. Many tombs of later pharaohs contained references to and references from Ramses II, underlining his lasting influence.

7. Royal Mortuary Temples:

Near Ramses II's tomb, on the west bank of the Nile, there were associated mortuary temples, such as the Ramesseum, where offerings and rituals were performed to honor the pharaoh's spirit.

Ramses II's funerary practices were in keeping with the rich tradition of ancient Egyptian beliefs regarding the afterlife. His tomb and the associated temples were constructed with care to ensure his continued existence in the world of the gods. While many tombs were looted over the centuries, the legacy of Ramses II and his contribution to Egyptian religious and funerary practices remain a significant part of the country's cultural heritage.

Rediscovery and Pop Culture

Ramses II's mummy, like his legacy, experienced an intriguing journey through history. His rediscovery in the 19th century and his continued influence on modern culture are noteworthy:

Rediscovery in the 19th Century: Ramses II's mummy was rediscovered in 1881 during an era of heightened interest in Egyptology. The mummy was found in a secret cache at Deir el-Bahri, near Luxor, by French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero. It had been moved there in antiquity to protect it from tomb robbers.

The rediscovery of Ramses II's mummy was a significant event in the history of Egyptology. It allowed researchers to study the remains of one of Egypt's greatest pharaohs and gain insights into his physical condition and life in ancient Egypt.

Modern Cultural Influence: Ramses II's influence on modern culture remains palpable in various ways:

Literature and Film: Ramses II has been a popular subject in literature and film. Authors like Christian Jacq and Wilbur Smith have written novels featuring Ramses II. Hollywood films like "The Ten Commandments" and animated features like "The Prince of Egypt" have brought his story to a global audience.

Art and Architecture: The grand temples and statues built by Ramses II continue to be symbols of Egyptian architectural and artistic prowess. His statues and inscriptions inspire artists, and their magnificence is featured in exhibitions and art galleries worldwide.

Tourism: The temples of Abu Simbel, built by Ramses II, are major tourist attractions, drawing visitors from around the world to witness the pharaoh's colossal statues and impressive temple complex.

Historical Significance: Ramses II's reign and the Battle of Kadesh have been subjects of extensive historical research and documentaries, contributing to our understanding of ancient Egypt's political and military history.

Continued Worship: In modern Egypt, there are festivals and rituals that continue to honor and celebrate the legacy of Ramses II. This illustrates his enduring presence in the cultural and religious landscape.

Ramses II's mummy's rediscovery and the enduring fascination with his life and reign demonstrate his significance and influence in modern culture. His name is synonymous with the grandeur of ancient Egypt and serves as a bridge between the past and the present, captivating the imaginations of people worldwide.

Ramses II, known as Ramses the Great, holds a place of profound significance in ancient Egypt and the annals of history. His enduring impact on both his own era and the centuries that followed is a testament to his extraordinary reign and remarkable achievements.

As one of Egypt's longest-reigning pharaohs, Ramses II provided a sense of stability and continuity in a time of great change. He solidified Egypt's borders, embarked on ambitious building projects, and demonstrated his prowess on the battlefield, most notably in the Battle of Kadesh. His diplomatic skills resulted in the signing of the first recorded peace treaty, emphasizing the importance of diplomacy in maintaining geopolitical stability.

Ramses II's architectural marvels, such as the Temple of Abu Simbel, continue to awe and inspire visitors, showcasing the grandeur of his rule. His artistic and literary revival during the Ramsesian Renaissance left an indelible mark on Egyptian culture, celebrating his life and achievements.

The legacy of Ramses II extends beyond ancient Egypt. His mummy's rediscovery in the 19th century rekindled interest in Egyptology, and his influence on modern culture remains palpable in literature, film, art, and tourism. His name is synonymous with the magnificence of pharaonic Egypt and continues to be celebrated in modern Egypt.

In sum, Ramses II is a paragon of ancient Egyptian power and prestige, leaving a lasting legacy that transcends the sands of time. His place in history is secure, and his name endures as a symbol of the grandeur and might of the pharaohs of ancient Egypt.

0 notes

Text

🌺TANIS🌺

☆Aprox 40 miles north of Cairo you can find the old city of Tanis, or Pi-Ramesse the northern city of the empire of Ramses II. ☆Discovered in the sixties by Pierre Montet who found the undisturbed tombs of faraos of the late period, Psusennes I, Osorkon II and Sheshonq III from the 21th and 22nd dynasty. ☆It was Ramses II who founded this new city, and most of the buildings were created from parts and statues taken from other areas. ☆After the collapse of the Egyptian empire in the 21st dynasty, it was Tanis which became the capital of the Northern part, while Thebes remained the residence for the south, so 4000 years after its unification the Two Lands separated again in the North and the South. Among the finds in the tombs were the beautiful Golden Mask of Psusennes I, which is now on display in the Cairo Museum. His third sarcophagus is made of solid silver and weighs almost a ton.

His remains and that of his wife Mutnetjmet are resting in the Cairo Museum.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Pi-Ramsès

Pi-Ramsès (également connue sous les noms de Per-Ramsès) était la ville construite en tant que nouvelle capitale dans la région du Delta de l'Égypte ancienne par Ramsès II (dit Le Grand, 1279-1213). Elle était située à l'emplacement de la ville moderne de Qantir dans le Delta oriental et, à son époque, elle était considérée comme la plus grande ville d'Égypte, rivalisant même avec Thèbes au sud. Son nom signifie "Maison de Ramsès" (également appelé "Ville de Ramsès") et elle fut construite à proximité de la ville plus ancienne d'Avaris.

Lire la suite...

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Interview: Egyptian Mythology by Garry Shaw

World History Encyclopedia is joined by Egyptologist and author Garry Shaw to chat about his new book Egyptian Mythology: A Traveller's Guide from Aswan to Alexandria.

Continue reading...

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lost Cities of the Ancients episode 1: Pi-Ramesses

This episode looks at the legendary lost city of Piramesse. This magnificent ancient capital was built 3,000 years ago by the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses the Great #history #ancientegypt

Lost Cities of the Ancients episode 1: Pi-Ramesses – This episode looks at the legendary lost city of Piramesse. This magnificent ancient capital was built 3,000 years ago by the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses the Great, but long ago the whole city disappeared. When it was rediscovered by early archaeologists, it opened up a bizarre puzzle – when Piramesse was finally found it was in the wrong place,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

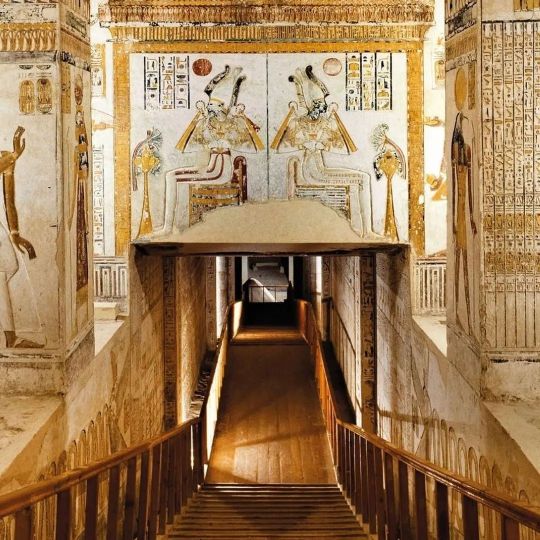

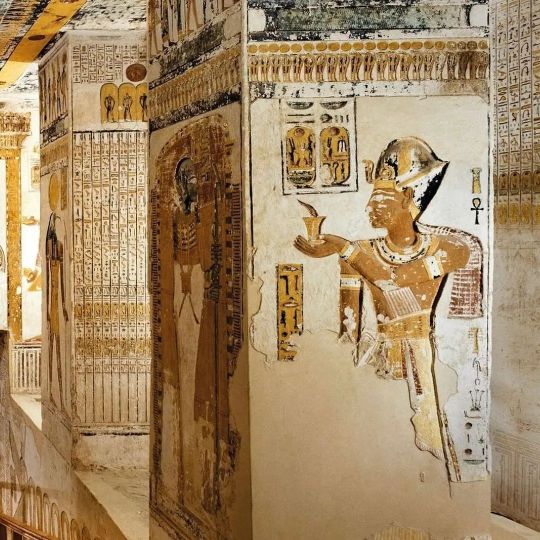

The Tomb of Ramessess VI

Ramesses VI Nebmaatre-Meryamun (sometimes written Ramses or Rameses, also known under his princely name of Amenherkhepshef C) was the fifth ruler of the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt. He reigned for about eight years in the mid-to-late 12th century BC and was a son of Ramesses III and queen Iset Ta-Hemdjert. As a prince, he was known as Ramesses Amunherkhepeshef and held the titles of royal scribe and cavalry general. He was succeeded by his son, Ramesses VII Itamun, whom he had fathered with queen Nubkhesbed.

After the death of the ruling pharaoh, Ramesses V, who was the son of Ramesses VI's older brother, Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI ascended the throne. In the first two years after his coronation, Ramesses VI stopped frequent raids by Libyan or Egyptian marauders in Upper Egypt and buried his predecessor in what is now an unknown tomb of the Theban necropolis. Ramesses VI usurped KV9, a tomb in the Valley of the Kings planned by and for Ramesses V, and had it enlarged and redecorated for himself. The craftsmen's huts near the entrance of KV9 covered up the entrance to Tutankhamun's tomb, saving it from a wave of tomb robberies that occurred within 20 years of Ramesses VI's death. Ramesses VI may have planned and made six more tombs in the Valley of the Queens, none which are known today.

Egypt lost control of its last strongholds in Canaan around the time of Ramesses VI's reign. Though Egyptian occupation in Nubia continued, the loss of the Asiatic territories strained Egypt's weakening economy and increased prices. With construction projects increasingly hard to fund, Ramesses VI usurped the monuments of his forefathers by engraving his cartouches over theirs. Yet he boasted of having "[covered] all the land with great monuments in my name [...] built in honour of my fathers the gods". He was fond of cult statues of himself; more are known to portray him than any Twentieth-Dynasty king after Ramesses III. The Egyptologist Amin Amer characterises Ramesses VI as "a king who wished to pose as a great pharaoh in an age of unrest and decline".

The pharaoh's power waned in Upper Egypt during Ramesses VI's rule. Though his daughter Iset was named God's Wife of Amun, the high-priest of Amun, Ramessesnakht, turned Thebes into Egypt's religious capital and a second center of power on par with Pi-Ramesses in Lower Egypt, where the pharaoh resided. In spite of these developments, there is no evidence that Ramessesnakht's dynasty worked against royal interests, which suggests that the Ramesside kings may have approved of these evolutions. Ramesses VI died in his forties, in his eighth or ninth year of rule. His mummy lay untouched in his tomb for fewer than 20 years before pillagers damaged it. The body was moved to KV35 during the reign of Pinedjem I, and was discovered in 1898 by victor Loret.

#The Tomb of Ramessess VI#Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt#Valley of the Kings#pharaoh#ruler#history#history news#ancient historuy#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#grave#ancient grave#art#artist#art work#afterlife#paintings#drawings#hieroglyphs#egyptian hieroglyphs

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some thoughts on a post of thatlittleegyptologist on sacred animals, animal worship etc

thatlittleegyptologist has posted this text replying to an anon ask submitted to @somecunttookmyurl (ttps://thatlittleegyptologist.tumblr.com/post/655071178034200576/the-ancient-egyptians-saw-their-kings-as-gods-and ) :

Oh Christ. Where to begin on this one? Let’s bullet point it shall we?

King as a god was only the Old Kingdom. After the trouble of the First Intermediate Period leading into the Middle Kingdom, the idea that the king was a god on earth fell wildly out of use. The king still had some divinity, but it was more akin to the “divine right to rule” fatefully championed by Charles I, than “I am a god and I will rule you”. Some kings were later deified, see Amenhotep I, but this was usually for very specific reasons and localised to one area.

Yes there are gods that express a duality of form in the animal head/human body variety. This is not their true form, but rather an aspect of Egyptian religion known as Duality (man/woman, animal/human, good/bad, chaos/balance etc). Duality was extremely important for Ma’at, the cosmic force said to keep the world in check. Everything has an opposing option. The gods with animal heads are merely expressing that aspect of their divinity. It does not mean that they *actually* had animal heads, in fact in inner sanctums of temples, like at Abydos, they’re depicted as fully human. Elsewhere they’re fully zoomorphic.

The Apis bull was not considered a god until the Ptolemaic period, though it was considered holy before this point. It's living bull form was considered an aspect of Ptah, and thus could answer for him. The Apis Bull is a pilgrimage site and a religio-legal functioning aspect of Egyptian society.

The Egyptians did not worship animals. This seemingly stems from an application of the practices of the late Late Period, and the Ptolemaic period, both of which are not culturally Egyptian. The practice of sacrificing animals and mummifying them for specific gods, is not practiced wholesale before the Late Period. It just doesn't happen. To say that they did worship animals throughout the Pharaonic period is a misunderstanding and perversion of the Duality aspect of divinity. The god is not an animal, it has an animal form that people believed the god worked though, like Anubis and the Golden Wolf guarding cemeteries, not that the god was literally an animal.

Asking statues or images of god/s questions in the hope that they may help is still practiced now, but saying 'very important questions' is rather a misnomer. Oracular questions were mostly legal disputes sought to be settled by common folk. Major decisions? Well I'm sure even today people have prayed to statues of gods before making major life decisions. Doesn't seem that odd.

'Magic', or to use the actual term Heka, is not 'magic'. It's a divine lifeforce that exists in everything the Egyptians did. To dismiss it as 'magic' is equivalent to dismissing what Christians believe is 'god's will', and that's a major failing in understanding how the Egyptians saw their world. Most Egyptians would not touch Heka, for it was not for them to use. Only those who were Priests, Medical practitioners, or the Royals could invoke it, and it was only invoked for specific reasons. Mutemhab making flatbreads and tending to the sheep on her roof is not going to be too bothered about Heka.

The collapse of the Egyptian civilisation is multifaceted. It's nothhing to do with Priests exploiting superstition, I can tell you that much. The Late New Kingdom collapse, which is part of my specialism, starts all the way back in the Middle Kingdom with the change of chief deity from Osiris to Amun. With religion more centralised, and sat within the Theban seat of power, the High Priests of Amun became highly influential. This gathered pace over the centuries, and became firmly cemented when Ramesses II moved the capital from Thebes to Pi Ramesses. Left to their own devices, and now without the centralised government all in once place, the power of the High Priests grew until you reach the reign of Ramesses XI wherein they are in open rebellion against the King, and the King's power is weakened so much the Egyptian people don't even care. When Ramesses XI dies, his successor is a former High Priest of Amun. There was also widespread corruption in local governments throughout Egypt, as the King could no longer control what happened. This is extremely evident in the main powerbase outside of Pi Ramesses, Thebes, where officials took bribes and made themselves wealthy while infrastructure and the empire crumbled. Coupled with this, you have the famines and droughts that happened from the reign of Ramesses III onwards. This led to food and wage shortages repeatedly from this point onwards, hence the strikes recorded as happening during this time. With food scarce, people took to robbing tombs as a way to barter with higher priced goods for grain, cloth, and beer. The longer this went on, the less faith people had in their Pharaoh to maintain Ma'at, and with Egypt weakened, the Hyksos started making incursions into Egyptian territory. With the Priests disinclined to do anything about this, it in fact helped their cause, it further weakened the position of Pharaoh. With a lack of power and provisions, the territory gained for the Egyptian empire slowly melted away as they could no longer sustain it, further weakening Egypt's position. The end of the New Kingdom and into the Third Intermediate Period coincides with these incursions, and eventually the rule by Kushite and Saite Kings, as Egypt's power waned further.Culturally, from this point on, Egypt is no longer the same, but since this is one of the better documented periods in texts that are not in Hieroglyphs/Hieratic, the events and practices of these periods have become the generalised 'this is what Egypt is like' facts, rather than the broader 'Egypt was a 6000 year old civilisation that is not a cultural monolith, and there are a lot of differences depending on the period you're talking about”

I have the following brief remarks on this text :

From what I have understood from my readings, the ideology of the divine kingship (the Pharaoh seen as embodiment or manifestation of Horus and bridge between the divine and human worlds) is a standard characteristic of the Egyptian worldview, even in attenuated form after the Old Kingdom.

This is how distinguished Egyptologists describe this aspect of the Egyptian civilization.

Anyway, I don’t think that the comparison of the Egyptian conception of divine kingship with the pretensions of Charles I of England is fortunate, as Charles I claimed that he had a divine right to rule, but not that he was in any possible form an embodiment or manifestation of the divine.

“Duality’ or not, the Egyptians did not manage to disentangle in their cult and religious representations their gods from animal forms, and this is for me a sign of some arrest of the development of the religious consciousness in Egypt.

The same obtains and a fortiori in the case of the sacred animals, which were seen at least in some cases as manifestations or “aspects’ of gods and, accordingly, should be taken care of, fed, and honored or worshipped, and the whole more general thing of the animal cults, which were extremely widespread in the Egypt of the Late Period.

But the Third Intermediate and Late Periods are still Egyptian civilization, although they differ a lot from previous periods.

Despite important foreign influences, all Egyptologists agree that these periods express mostly indigenous developments of the Egyptian religion and culture, although these developments are often going to the wrong direction.

And to insinuate that the animal cults and the view of specific animals as manifestations of gods were not “culturally Egyptian” but something else is very inaccurate and problematic on many levels.

(Btw it is sure that the Apis Bull was worshipped as manifestation/incarnation of Ptah far before the Ptolemaic period, already under the 18th Dynasty)

The Egyptian practice of oracles through interpretation of the movements of specific status which prevailed after the New Kingdom is not of course comparable to the practice of saying a prayer to a statue of a god before taking some decision. In fact in the case of the Egyptian oracles it was the god himself who was taking the decision via the oracle, of course as the latter was manipulated by the priests.

Magic in ancient Egypt was magic, not “god’s will”. Through magic you try to manipulate things, something that you cannot do with god’s will. I don’t say that we should judge this by our contemporary standards, but magic -usually without negative connotations- was part of the Egyptian worldview and practice.

I don’t think that it is illegitimate, let alone “racist” (!), to ask what role the increase of the role of the statues of the gods and their oracles in the process of decision making and more generally in the political and social life and the multiplication of the cults of sacred animals after the New Kingdom may have played in the intellectual stagnation and decline of Egypt.

This, given also that both these developments were connected with the increase of the power and the influence of the priests, political, social, but also economic.

I don’t think either that it is illegitimate or “racist” to ask for what reasons (intellectual, cultural, social) there has been no appearance in Egypt of some criticism of such mentalities and practices or some criticism of the traditional view on magic, whereas the Greeks achieved to develop forms of criticism and of philosophical reinterpretation of their religion and traditional religious practices and to propose new forms of rationality.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think they're in the process of building Pi-Ramesses here

Speaking of which, the book does claim that they built it, and that's probably the reason why Ramesses II is usually cast as the pharaoh when adapting this story, but the timeline does not match up.

I've heard the theory (and I can't find a source) that what they actually built was the city later absorbed by Pi-Ramesses, with the name of the city being changed in the record of Exodus so people would understand the where, if not the what.

Also, the most likely pharaoh of Exodus (the one who suffered the plagues, anyways) is probably Tuthmose II (Hatshepsut's predecesor). What I've heard, anyways

0 notes