#R. Freeman Butts

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

happy anniversary garou: mark of the wolves!! it's been like 4 years now since i got into it :') i love this game sooo much it's very dear to me

^ they didn't know they were gonna be swimming..

#doodles#fatal fury#garou: mark of the wolves#terry bogard#rock howard#kim jae hoon#kim dong hwan#hokutomaru#gato#hotaru futaba#b. jenet#tizoc#freeman#kevin rian#marky#marco rodriguez#khushnood butt#abel cameron#grant#kain r. heinlein#wanted to do a drawing where they were swimming :3#summer fun time yay o)-<

78 notes

·

View notes

Note

Annon-Guy: With Fatal Fury: City of the Wolves coming up, I would like to know what you thought of each of the 14 characters that were playable in Garou: Mark of the Wolves?

Rock Howard

Terry Bogard

Hotaru Futaba

Gato

Kim Jae Hoon

Kim Dong Hwan

Hokutomaru

B. Jenet

Marco Rodrigues (formerly named "Khushnood Butt")

Tizoc/Griffon Mask

Kevin Rian

Freeman

Grant

Kain R. Heinlein

Grant was probably my favorite among the roster, but the game itself felt fluid when I played it on Kawaks emulator years ago.

Freeman was pretty interesting too.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

McCarthy accused of elbowing lawmaker, while fight nearly breaks out in Senate

Wa-Po Gift Article - the girls are fighting~~~~~

absurd excerpts below (I bolded some bits):

Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) declared during his weekly news conference Tuesday that the House “is a pressure cooker” after lawmakers have spent roughly a dozen grueling weeks together in the halls of Congress. That was evident minutes beforehand when Rep. Tim Burchett (R-Tenn.) came up behind Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) and began yelling in his ear, accusing him of elbowing him in the back as they passed each other in a crowded hallway. The Senate had fireworks of its own Tuesday as Sen. Markwayne Mullin (R-Okla.) brought a hearing about corporate greed to a standstill as he confronted one witness, stood up and challenged him to a fistfight.

[...]

Joanne B. Freeman, a history and American studies professor at Yale University who wrote a book detailing the history of violence in Congress, wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter: “Please stop providing fodder for Field of Blood volume two.”

[...]

The episode between Burchett and McCarthy was not captured on video but was witnessed by reporters. “Hey, Kevin. Why did you walk behind me and elbow me in the back?” Burchett asked as The Post interviewed McCarthy. “You have no guts.” “I didn’t do that,” McCarthy replied. As Burchett continued to yell, McCarthy laughed and said, “Oh my God.” Burchett was one of eight Republicans who voted to oust McCarthy as House speaker, a rebuke the California lawmaker has bitterly noted, publicly and privately. “You are so pathetic,” Burchett said before slowing his steps to avoid being directly behind McCarthy. “Thank you, Tim,” McCarthy said.

[...]

McCarthy denied intentionally assaulting Burchett but acknowledged he may have inadvertently bumped into him while they were in a crowded hallway. “I would not elbow. I would not hit him in the kidney,” McCarthy told reporters. They were in a hallway, and “I guess our shoulders hit.” McCarthy later added: “I guess our elbows hit as I walked by. … If I would hit somebody, they would know I hit them.” He also brushed aside a question about Gaetz filing a complaint to the Ethics Committee, telling reporters, “I think Ethics is a good place for Gaetz to be.”

[...]

Mullin, who says in his biography that he turned his family’s plumbing business into “the largest service company in the region,” began reading a June 21 social media post by O’Brien that questioned the lawmaker’s business acumen. The two had sparred previously over the senator’s claims of business success. “Greedy CEO who pretends like he’s self made,” Mullin read Tuesday, quoting O’Brien’s post. “In reality, just a clown & fraud. Always has been, always will be. Quit the tough guy act in these Senate hearings. You know where to find me. Anyplace, Anytime cowboy.” Mullin, then speaking to O’Brien, said, “Sir, this is a time and this is a place,” pointing his finger to the floor between the two men. “You want to run your mouth, we can be two consenting adults. We can finish it here.” After O’Brien said that would be “perfect,” Mullin asked, “You want to do it now?” “I’d love to do it right now,” O’Brien said as he sat at the table where witnesses and guests routinely speak to lawmakers. “Stand your butt up then,” Mullin shot back. “You stand your butt up,” O’Brien responded. After Mullin stood up, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), the committee’s chairman, could be heard on video saying, “Stop it” and “Sit down.” Amid the cross talk, O’Brien could be heard saying, “Is that your solution?” Sanders, imploring Mullin to sit down, said, “You’re a United States senator!”

stand. your butt. up. this is third grade shit.

absurd--all absurd.

#also a sign of the quality of sitting members of congress that the GOP dredges up from - well - the dregs#politics#us politics#GOP

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 4.13

Beer Birthdays

Joseph Bramah (1748)

Albert C. Houghton (1844)

George Gund II (1888)

Julie Bradford Johnson (1953)

Ray McCoy (1960)

Andreas Fält (1971)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Don Adams; actor (1923)

Peter Davison; actor, "Dr. Who" (1951)

James Ensor; Belgian artist (1860)

Al Green; R&B singer (1946)

Thomas Jefferson; 3rd U.S. President (1743)

Famous Birthdays

Lyle Alzado; Denver Broncos DE, actor (1949)

Samuel Beckett; Irish writer (1906)

Lou Bega; pop musician (1975)

Peabo Bryson; pop singer (1951)

Alfred Butts; Scrabble game creator (1899)

Jack Casady; rock bassist (1944)

Teddy Charles; jazz vibraphonist (1928)

Bill Conti; composer (1942)

Jana Cova; Czech porn actor, model (1980)

Erich von Daniken; writer (1935)

Stanley Donen; film director (1924)

Tony Dow; actor (1945)

William Henry Drummond; Canadian poet (1854)

Guy Fawkes; English conspirator (1570)

Edward Fox; actor (1937)

Bud Freeman; jazz saxophonist (1906)

Amy Goodman; journalist, writer (1957)

Dan Gurney; auto racer (1931)

Jeanne Guyon; French mystic, founder of Quietism (1648)

Seamus Heaney; poet (1939)

Garry Kasparov; chess player (1963)

Howard Keel; actor (1919)

Davis Love III; golfer (1964)

Ron Perlman; actor (1950)

Philippe de Rothschild; French winemaker (1902)

Rick Schroder; actor (1970)

Paul Sorvino; actor (1939)

Jon Stone; Sesame Street co-creator (1931)

Lyle Waggoner; actor (1935)

Max Weinberg; drummer (1951)

Eudora Welty; writer (1909)

F.W. Woolworth; merchant, 5&10 cent store creator (1852)

1 note

·

View note

Text

PRIME REASON

While the challenge of promoting civic knowledge, skills, and dispositions is an ever present one, there currently seems to be an increased need to address this challenge. For years, there has been an ongoing release of studies documenting the lack of these attributes or abilities that one associates with good citizenship among not only young people but citizens in general.

This has only magnified with the currently, often-cited polarization one finds in the American political landscape. Surely, this reflects less than stellar accomplishments by the nation’s civics education programs. And one can say, with the exception of recent reports in some segments of young people around the country, that things are not getting better.[1] Here is what the journalist, Rebecca Winthrop, wrote in 2020,

Americans’ participation in civic life is essential to sustaining our democratic form of government. Without it, a government of the people, by the people, and for the people will not last. Of increasing concern to many is the declining levels of civic engagement across the country, a trend that started several decades ago. Today, we see evidence of this in the limited civic knowledge of the American public, 1 in 4 whom, according to a 2016 survey led by Annenberg Public Policy Center, are unable to name the three branches of government. It is not only knowledge about how the government works that is lacking – confidence in our leadership is also extremely low. According to the Pew Research Center, which tracks public trust in government, as of March 2019, only an unnerving 17 percent trust the government in Washington to do the right thing. We also see this lack of engagement in civic behaviors, with Americans’ reduced participation in community organizations and lackluster participation in elections, especially among young voters.[2]

This sort of concern and findings by a variety of academic and journalistic sources have been often cited in this blog.

So, from less civic engagement in community efforts to acquiring political knowledge, both of the nation’s founding principles and of the civic challenges of the day, to voting and performing other civic activities, the level of engagement is wanting. Within this context of how civics education efforts should be conducted, this blogger’s task – as he sees it – is to argue for those in charge to institute various elements of a reform effort in civics education.

Naturally, besides what goes on in the classroom, that focus would include what the preparation of teachers should include to meet the challenges that civics education confronts today. To meet the aims of imparting civic knowledge and skills and encouraging a disposition prone toward civic engagement, how teachers should approach these educational aims, what they should be able to do, and how they should be prepared to do their jobs need to be considered.

In order to meet the above concerns, one is apt, in typical business style, to collectively find the components of the teacher preparation process, narrow one’s focus to those portions of the process dedicated to preparing teachers to handle relevant civic factors, identify what’s wrong, and go about devising plans and allocate resources to fix the problem(s). Sounds logical enough, but is it enough?

In addressing this topic, this posting does not count on its writer’s academic credentials but instead on his being a veteran classroom teacher of twenty-five years. While the years of his service are a bit dated (1972-2000 – with some of those years having him do some other things), he feels they still provide relevant insights as to what is happening today – the reader will be the judge as to whether he is right.

What he learned from that teaching experience – the constructed beliefs he developed – allows him to feel he can add to the discourse about what is ailing civics education. No doubt the challenges facing civics are daunting, not only due to a lack of resources, but also due to a multitude of factors affecting the general situation. With that in mind, what follows is his take on what should constitute an ideal teacher preparation program which emphasizes civics education.

That is, what should such a program include as its elements? Warning: transcending all of these factors and elements is a holistic aspect that defies systemic linear thinking and planning as just described. He hopes his presentation over several postings captures that sense and communicates it to the reader. His goal in describing and explaining his specific plan is to convey an element, provide a rationale for it, and then speculate and react to what the reader might respond to the given element.

This general order of presentation will be followed as the individual elements are addressed. When all of the elements are “covered,” he will then make some general comments as to the holistic nature of the concern. But before starting, the reader should also be advised that the elements will not be divided by postings. For example, this posting begins its comments on element one and will continue with element one in the next posting. How the whole presentation will appear or be divided is still being considered.

So, here is the first element,

Element One: A viable teacher preparation program needs to make clear that civic preparation is not only a foundation of civics education or even social studies, but of all public education and of responsible private educational programs as well.[3]

In terms of this element, it is helpful for one to step back a moment and ask why one supports public education. What serves as the ultimate or trump value justifying all the expense that public education represents? Different perspectives would probably elicit different answers to this question.

One way to address this question is to look at the origins of public education; that is, what was the original intent of having public education? According to the educational historian, R. Freeman Butts,[4] it was to support the development of a civic minded citizenry to meet the inherent needs of a functioning republic. And supporting this notion are the thoughts of the historians Allen Nevins and Henry Steele Commager.

They state: “The Founding Fathers knew that their experiment in self-government was without precedent, and they took it for granted that it could not succeed without an enlightened electorate.”[5] They go on to cite the efforts of Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Rush, Noah Webster, George and his son DeWitt Clinton to establish an accessible school system in their respective states.

And another historian, Samuel E. Morrison, more explicitly states the original purpose of public schools in the following way:

Opposition to free public education came from the people of property, who thought it intolerable that they should be taxed to support the common schools to which they would not dream of sending their children. To this argument the poor replied with votes, and reformers with the tempting argument that education was insurance against radicalism.[6]

All other reasons than that of preparing responsible, civic minded citizens (such as preparing an educated workforce, keeping youngsters from competing for jobs and off the streets, advancing the career ambitions of individual citizens, etc.), while not necessarily exclusive of the main goal, are at best secondary.

Yes, the expense of public schooling needed to be justified to others besides the rich and these practical and utilitarian reasons were advanced by the likes of Horace Mann[7] and others, but the main justification was the promotion of civic education. Butts further writes,

In re-examining the stated purposes used to justify the development and spread of the common public school in the mid-nineteenth century, I believe that the citizenship argument is still valid. The highest priority for a genuinely public school is to serve the public purposes of a democratic political community. Those in favor of “excellence” or “back to the basics” [cries one commonly heard at the time Butts wrote these words] should be reminded that citizenship is the basic purpose for universal literacy. If the fundamental purposes of schooling are to be confined to preparing for a job or developing individual talents, these might well be achieved in private schools that select students for particular destinies. But the faith of the common school reformers, as of the founders, that the civic tasks can best be performed by public schools that are characterized primarily by a public purpose, public control, public support, public access, and public commitment to civic unity was soundly based.[8]

So, the first element is for involved and interested parties to see the main function of public and even private education is to promote good citizenship – all else follows from this fundamental aim.

And with that general support for a civic foundation, this posting stops and gives the reader an opportunity to mull over this role of civics or for this central rationale for public schools. The next posting will pick up this first element, elaborate on it and, given the space remaining, continue with the others. In all there are five elements.

[1] There have been reports of an uptick in young people becoming more politically engaged. For example, see David Lauder, “Essential Politics: Young People’s Political Engagement Is Surging. That’s a Problem for Republicans,” The Los Angeles Times (April 23, 2021), accessed September 27, 2021, https://www.latimes.com/politics/newsletter/2021-04-23/surge-political-engagement-youth-problem-for-gop-essential-politics .

[2] Rebecca Winthrop, “The Need for Civic Education in the 21st – Century Schools,” 2020 Brookings Policy (June 4, 2020), accessed September 26, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/bigideas/the-need-for-civic-education-in-21st-century-schools/ .

[3] These comments will directly address public education, but a lot of what will be stated will also apply to private or sectarian educational efforts.

[4] R. Freeman Butts, The Civic Mission in Educational Reform: Perspectives for the Public and the Profession (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1989).

[5] Allen Nevins and Henry Steele Commager, A Pocket History of the United States (New York, NY: Washington Square Press, 1986).

[6] Samuel E. Morrison, The Oxford History of the American People (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1965).

[7] Allen C. Ornstein and Francis P. Hunkins, Curriculum: Foundations, Principles, and Issues (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2004).

[8] Butts, The Civic Mission in Educational Reform, 130.

0 notes

Note

FUCK YEA COUNT ME AS T H E R E!! BUTT MORPHINE TIEM!!

{ GORDON FREEMAN ASS MORPHINE MOMENTS.

still dont know how to crouch jump either u-u goddammit JHKJFKJDSF }

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 movies that really got science wrong

Science has been a dependable companion to Hollywood, giving the hereditary enchantment that breathed life into dinosaurs back, the errant medication that gave our planet to the gorillas, and the radiation that helped man become bug.

In any case, has Hollywood regarded science consequently?

In the tallness of summer blockbuster season, we asked everybody from George Church to Dr. Richard Besser to specialists went government officials to certainty check the big-screen science behind some paramount films and detail the scenes that made them squirm in the theater.

What's more, we'd prefer to give a cap tip to @TheSciBabe otherwise known as Yvette d'Entremont, a previous systematic scientific expert, for rousing this rundown. Her own pick is 2012's "The Avengers."

"Jurassic Park" (1993)

Featuring

Sam Neill, Jeff Goldblum, and Laura Dern

IMDB plot rundown

During a review visit, an amusement park endures a significant force breakdown that permits its cloned dinosaur displays to go crazy.

Master truth check

One of my preferred bloopers was "Jurassic Park" utilizing "Lysine Contingency" for biocontainment. [Editor's note: Lysine Contingency was a presented hereditary change that made the dinosaurs reliant on lysine supplements from the staff so they couldn't get by outside the recreation center, as indicated by Jurassic Wiki.] But lysine is available in all nourishments on the planet.

— George Church, geneticist and manufactured scientist who instructs at Harvard Medical School and helped found the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering. Among his many research activities, Church and his associates at Harvard effectively put wooly mammoth qualities into the genome of an Asian elephant.

I love the special visualizations. I went to see it with my then beau (presently spouse) on the big screen and it truly caught my creative mind. However, even in those days, I realized eradication isn't reversible!

— Dr. Reshma Kewalramani, official VP and boss medicinal official at Vertex Pharmaceuticals

"Star Trek: The Motion Picture" (1979)

Featuring

William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, and DeForest Kelley

IMDB plot outline

At the point when an outsider shuttle of tremendous force is spotted moving toward Earth, Admiral James T. Kirk resumes direction of the upgraded USS Enterprise so as to capture it.

Master reality check

In the old "Star Trek" motion pictures, it used to trouble me a great deal when a character was shot with a phaser. The individual was killed down to their shoes however it left the ground underneath totally immaculate.

— Rep. Bill Foster (D-Ill.), previous physicist

"Episode" (1995)

Featuring

Dustin Hoffman, Rene Russo, and Morgan Freeman

IMDB plot synopsis

Armed force specialists battle to discover a solution for a dangerous infection spreading all through a California town that was brought to America by an African monkey.

Master certainty check

"Episode" was dreadful. How on the planet did they get enough plasma from a solitary monkey to spare a great many individuals from a destructive Ebola-like infection? How is it conceivable the first flare-up in an African town slaughtered, obviously, 100 percent of the populace, but then there were survivors when it arrived at white people in the U.S.A.? … Some fear inspired notions asserting HIV was "made in a CIA lab" refer to that film. It has demonstrated unthinkable, on account of Hollywood, to get the world to comprehend that Richard Nixon shut down the U.S. hostile bioweapons program during the 1970s, and there is no CIA bioengineering mystery lab.

— Laurie Garrett, Pulitzer-prize-winning columnist, creator of "The Coming Plague," and specialist on Steven Soderbergh's 2011 film, "Infection"

The revealed motivation for Dustin Hoffman's character in the motion picture additionally had a few musings.

In all the time I was in the Army or at CDC, we never "nuked" an African town to contain a flare-up. The monkey that carried the sickness from Africa to the U.S. was a capuchin or Cebus monkey, which is a South American animal categories. To spare a town passing on from the illness, they plasmapheresed [Editor's note: removed antibodies from the blood of] said monkey and this around 20-pound monkey yielded a unit of plasma for each inhabitant of the town — a serious accomplishment. The monkey more likely than not been drained a while later.

— Dr. C. J. Subsides, a virologist who took a shot at Ebola and other lethal pathogens at the U.S. Armed force Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases and at the CDC

"Frenzy" (2018)

Featuring

Dwayne Johnson, Naomie Harris, Malin Akerman

IMDB plot rundown

At the point when three unique creatures become contaminated with a perilous pathogen, a primatologist and a geneticist collaborate to prevent them from decimating Chicago.

Master certainty check

"Frenzy" messes around with CRISPR quality altering, however makes large, George-sized errors en route. CRISPR could speculatively be utilized to attempt to give animals new highlights like wings, however you'd almost certainly need to begin with one-cell undeveloped organisms. Additionally, even in some popular, weaponized structure making an infectious quality drive, CRISPR couldn't influence the genomes of a sufficiently high level of cells to cause changes in an entire existing creature and it'd to be too moderate a procedure for Hollywood. You'd presumably get a great deal of asymmetry, as well, with the end goal that that wolf beast in the film, for example, could simply have made them wing and flew around and around, or developed that wing out of its nose or butt. An animal growing up mixes of inconsequential attributes like wings and a porcupine tail from CRISPR is much harder to clarify. At long last, the possibility of a cure or on-off switch for quality alters is less absolutely outlandish and the last is really being investigated in the lab, however most likely couldn't influence only one characteristic like hostility and wouldn't take 10 minutes.

— Paul Knoepfler, immature microorganism researchers at the University of California, Davis

Two STAT correspondents additionally went out to see the films to check whether "Frenzy" got the study of CRISPR right. Peruse our audit.

"Skyfall" (2012)

Featuring

Daniel Craig, Javier Bardem, and Naomie Harris

IMDB plot rundown

Bond's dependability to M is tried when her past causes issues down the road for her. When MI6 goes under assault, 007 must find and pulverize the risk, regardless of how close to home the expense.

Master actuality check

The scoundrel in the James Bond motion picture "Skyfall" is a disenthralled previous government agent whose jaw was as far as anyone knows liquefied away by a hydrogen cyanide suicide pill turned sour. With the exception of … hydrogen cyanide is most popular as a toxic gas and hydrocyanic corrosive, from which it very well may be inferred, is less destructive than lemon juice. On the off chance that it was that destructive, it would have liquefied the container itself some time before. I was irritated to such an extent that my child later said he could never go with me to a decent government agent film again.

— Deborah Blum, chief of the Knight Science Journalism program at MIT, writer of "The Poisoner's Handbook" and the up and coming "The Poison Squad"

"Excursion to the Center of the Earth" (1959)

Featuring

James Mason, Pat Boone, Arlene Dahl

IMDB plot outline

An Edinburgh teacher and arranged partners follow an adventurer's path down a wiped out Icelandic fountain of liquid magma to the world's inside.

Master truth check

I still can't seem to experience any individual who has visited the focal point of the earth, cruised an underground ocean in a mushroom vessel, or wellbeing drifted on of magma — or all the more precisely, magma.

— Rep. Michael Burgess (R-Texas), previous specialist

"Disease" (2011)

Featuring

Matt Damon, Kate Winslet, and Jude Law

IMDB plot rundown

Medicinal services experts, government authorities, and ordinary individuals wind up amidst an overall plague as the CDC attempts to discover a fix.

Master Fact-check

From multiple points of view it gets the science right, yet I was struck by the speed by which they made another antibody and spared the world. That is deluding. As we've seen with HIV, Ebola, Zika, jungle fever … making immunizations that are protected and compelling can take quite a while and can be slippery. The quick making of an immunization in "Infection" can add to the bogus desire for what science can do during a general wellbeing emergency.

— Dr. Richard Besser, president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and previous acting chief (during the beginning of the H1N1 flu pandemic) of the CDC

"Prometheus" (2012)

Featuring

Noomi Rapace, Logan Marshall-Green, and Michael Fassbender

IMDB plot outline

Following hints to the starting point of humanity, a group finds a structure on a removed moon, yet they before long acknowledge they are not the only one.

Master truth check

I need to state the film that truly irritated me was "Prometheus." The cartographer gets lost promptly, and when the scholar sees an outsider creature he needs to snuggle with it. At that point the entire team just keeps on doing numbskull things to place everybody in harm's way.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

GAROU: mark of the wolves

#doodles#fatal fury#garou: mark of the wolves#rock howard#terry bogard#hotaru futaba#gato#kim dong hwan#kim jae hoon#tizoc#khushnood butt#marco rodriguez#bonne jenet#hokutomaru#kevin rian#marky#freeman#kain r. heinlein#grant#abel cameron#*kisses this drawing* i love you so much#i put all my love into this drawing bc i love mow so so so much#i even made the title have a cool gradient....i hope it shows o_o

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best movie I've seen so far, this year... Hitman's Wife's Bodyguard. Now Available to Own on 4K, Blu-Ray and DVD from Lionsgate

New Post has been published on https://is.gd/uyIWkN

Best movie I've seen so far, this year... Hitman's Wife's Bodyguard. Now Available to Own on 4K, Blu-Ray and DVD from Lionsgate

Hitman’s Wife’s Bodyguard

Street Date: August 17, 2021

Production Year: 2021

Genre: Action, Comedy

Rated: R for strong bloody violence throughout, pervasive language and some sexual content

Run Time: 99 Minutes

Hitman’s Wife’s Bodyguard is the best movie that I’ve seen so far this year. You can watch or now own it on DVD, Blu-Ray or 4K from Lionsgate.

For me any movie with Samuel L. Jackson and Morgan Freeman together is a must-see. Throw in Ryan Reynolds and I know that I’m going to laugh my butt off…lol

The world’s funniest and oddest, yet most lethal odd couple bodyguard Michael Bryce (Ryan Reynolds) and hit man Darius Kincaid (Samuel L. Jackson) are back and better than ever in Hitman’s Wife’s Bodyguard. Still not licensed, Bryce is forced into action by Darius’s wife, an international con artist Sonia Kincaid (Salma Hayek). As Bryce is driven over the edge by the volatile spouses, the trio get in over their heads in a global plot and soon find that they are all that stand between Europe and a vengeful and powerful madman (Antonio Banderas). As if the cast couldn’t be any more star-studded or hilarious, Morgan Freeman joins in on the deadly mayhem.

Own/Buy It Today on Amazon

DVD for $17.96

Blu-Ray for $19.96

4K for $24.96

Follow Hitman’s Wife’s Bodyguard #HitmansWife

Follow Lionsgate

0 notes

Text

Birthdays 4.13

Beer Birthdays

Joseph Bramah (1748)

Albert C. Houghton (1844)

George Gund II (1888)

Julie Bradford Johnson (1953)

Ray McCoy (1960)

Andreas Fält (1971)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Don Adams; actor (1923)

Peter Davison; actor, "Dr. Who" (1951)

James Ensor; Belgian artist (1860)

Al Green; R&B singer (1946)

Thomas Jefferson; 3rd U.S. President (1743)

Famous Birthdays

Lyle Alzado; Denver Broncos DE, actor (1949)

Samuel Beckett; Irish writer (1906)

Lou Bega; pop musician (1975)

Peabo Bryson; pop singer (1951)

Alfred Butts; Scrabble game creator (1899)

Jack Casady; rock bassist (1944)

Teddy Charles; jazz vibraphonist (1928)

Bill Conti; composer (1942)

Jana Cova; Czech porn actor, model (1980)

Erich von Daniken; writer (1935)

Stanley Donen; film director (1924)

Tony Dow; actor (1945)

William Henry Drummond; Canadian poet (1854)

Guy Fawkes; English conspirator (1570)

Edward Fox; actor (1937)

Bud Freeman; jazz saxophonist (1906)

Amy Goodman; journalist, writer (1957)

Dan Gurney; auto racer (1931)

Jeanne Guyon; French mystic, founder of Quietism (1648)

Seamus Heaney; poet (1939)

Garry Kasparov; chess player (1963)

Howard Keel; actor (1919)

Davis Love III; golfer (1964)

Ron Perlman; actor (1950)

Philippe de Rothschild; French winemaker (1902)

Rick Schroder; actor (1970)

Paul Sorvino; actor (1939)

Jon Stone; Sesame Street co-creator (1931)

Lyle Waggoner; actor (1935)

Max Weinberg; drummer (1951)

Eudora Welty; writer (1909)

F.W. Woolworth; merchant, 5&10 cent store creator (1852)

0 notes

Text

IT’S ALL IN THE PRESENTATION

This posting continues with this blogger’s ideas concerning an ideal civics teacher preparation program that directly addresses the current state of poor citizenry in the US. He argues that such a program should include five elements. The last posting started with element one and it is,

A viable teacher preparation program needs to make clear that civic preparation is not only a foundation of civics education or even social studies, but also of all public education and of responsible private educational programs as well.

In supporting such a bold claim, that posting utilized the ideas of prominent educator, R. Freeman Butts, and several prominent historians, Allen Nevins, Henry Steele Commager, and Samuel E. Morrison. They, in turn, cite the founding fathers and how they considered the need for public education.

The crux of the argument is that it is only the general need for a viable and engaged citizenry – one necessary to maintain a republic – that justifies taxpayers being called upon to foot the bill for such an expensive endeavor. For example, early on, there was the hesitancy among the rich to contribute to such funding since they would not be sending their children to such schools.

But even in the case of private schools, the promotion of good citizenship should play a central role, since even the rich or other segments using private schools are expected to play their role in maintaining and even promoting the common good – that’s in everyone’s best interest in the long run. Some might argue that a disregard for this imbedded relationship is a major cause of the nation’s current maladies.

There have been, through the years, attempts to delineate or identify what schools should offer and what their aims and goals should be. A review of these offerings will indicate the relative position that civics education has enjoyed through the years. Beginning with the Spencer Report in 1859, in which Herbert Spencer attempted to answer the question, “What Knowledge Is of Most Worth?” he listed five realms.

They are: (1) direct self-preservation, (2) indirect self-preservation (obtaining food and shelter), (3) parenthood, (4) citizenship, and (5) leisure.[1] Following this conceptual path, the National Education Association’s Commission on the Reorganization of Secondary Education issued in 1918 its famous Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education. These principles are (1) health, (2) command of fundamental processes, (3) worthy home membership, (4) vocational education, (5) civic education, (6) worthy use of leisure, and (7) ethical character.[2]

Through these publications, one starts to sense a slight shift in emphasis. While citizenship is still prominent, a more consumer orientation – one in which the student and his/her parents are seen as consumers of this public service – took hold. Then, in 1938, the National Education Association (NEA) issued a report entitled The Purpose of Education in American Democracy, which seemed to re-ignite an, albeit modest, awareness of civics education.

This NEA report’s list of aims is (1) self-realization, (2) human relationships, (3) economic efficiency, and (4) civic responsibility.[3] In this case, the historical context of that time seems to have played a role. One can speculate that the level of interdependence which the Depression imposed on people encouraged a more communal set of aims.

More recent efforts to list aims and goals for education have maintained a lukewarm level of importance attributed to civics. One can denote a more subordinate concern for the subject and a castigation of the field as being impractical and being sacrificed to the more utilitarian expectations of education – those of preparing students for the job market and other personal concerns.

That is, educational aims and goals express a greater concern for the welfare of the individual students than for the health of the society.[4] Education priorities have taken an even more consumer orientation, leaving the more civic concerns of the founding fathers far behind and mostly out of sight. This blogger submits that that change is at the center of the nation’s civic/political problem that is tearing apart the general health of the republic.

On a more specific level, in the very field of social studies, amid concern and debate about how central the teaching of the social sciences and history disciplines should be in pre-college curriculums, social studies began in 1916 with a strong emphasis on a civic focus. Social studies subjects were meant to assure that American children were amply prepared to take on the responsibilities of citizenship. This was seen as particularly important in the midst of the vast immigration that was taking place in the early twentieth century.

A bit later, the disciplines of history and of the social sciences were to be supporting components of such an effort.[5] This was, at that time, and is still controversial among both members of those organizations and those who nationally set the policies affecting social studies. The professional organizations representing those academic fields that, it so happens, supported the birth and growth of social studies, were and are still supportive of such an emphasis.

Many in these organizations, such as the American Historical Association, wanted and still argue for a discipline-centered approach for social studies, an argument they “won” without being aware of it. Most actual offerings in social studies are organized around textbooks that are often authored by experts in the fields of the social sciences and history but then go through the “neutering” process known as the textbook adoption process at state levels (a process that has garnered the critical attention of Diane Ravitch[6] among other commentators).

The sum total of this reaction by academics has been misplaced. What historians, for example, such as what the late Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. riled against, is basically inaccurate. Social studies, as it was first defined, is not what children and adolescents experience in America’s schools. What they experience is excessively structured material presented in textbooks written in horribly boring style and content, which has little to do with any preparation for citizenry in a meaningful way or enticement of students to pursue those subjects at higher levels.

These presentations are full of platitudes about the sacrifices of previous generations (which would be useful if couched in realistic settings with vivid, dramatic descriptions of how those sacrifices unfolded) or the abstract depictions of national institutions – such as the presidency. For example, American government is taught as if it were a mechanical engine with parts and certain processes, devoid of the human quality that might engender any interest on the part of the student.

The only substantive topic given emphasis in the typical government textbook is that of individual rights. Per se, that would be good if not for how exclusive that attention is and how clinical the language tends to be. A recent review of one of the popular textbooks revealed three chapters dedicated to rights and the only reference to community in the index referred to local community standards as they related to censorship.

With that bit of criticism, this posting will stop describing this element. The next posting will review the significance of the comments that this and the last posting conveyed relevant to the overall goal, the elements of a teacher preparation program. Again, this first element of teacher preparation program is to instill in teachers a sense of how central civics is to what should be the purposes of a public-school education.

[1] Herbert Spencer, Education: Intellectual, Moral, and Physical (New York, NY: Alden, 1885)

[2] Commission on the Reorganization of Secondary Education, Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education, Bulletin 35 (Washington, DC: U. S. Office of Education, 1918).

[3] Educational Policy Commission, The Purpose of Education in American Democracy (Washington, DC: National Education Association, 1938).

[4] See, for example, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Committee on Research and Theory, Measuring and Attaining the Goals of Education (Alexandria, VA: ASCD, 1980) AND U. S. Department of Education, National Goals for Education (Washington, DC: U. S. D. O. E., 1990).

[5] R. Freeman Butts, The Civic Mission in Educational Reform: Perspectives for the Public and the Profession (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1989).

[6] For a summary description of Ravitch’s critique see Jay Mathews, “Why Don’t We Fix Our Textbooks?”, The Washington Post (March 22, 2005), accessed September 30, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A56501-2005Mar22.html .

#teacher preparation#educational organizations#goals of education#aims of education#civics education#social studies

0 notes

Text

First, an apology for the title slug. I know you’re all sick and tired of plays on A Love in the Time of Cholera. Still. There’s a reason we’re doing it.

Second… but really first:

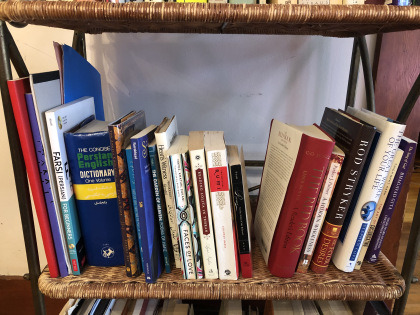

i. A catalogue

I recently moved, and as part of the uprooting, I culled my physical books to the essentials. (Ok, I moved like 500 metres away, but hey, packing and thus purging was definitely involved.) Stress on the physical: thank gods for my e-readers, a library of thousands always in my pocket.

Still. I was pretty ruthless. Totally ruthless, actually. Goodbye, university textbooks. Goodbye, books from the “I was a teenage Wiccan” phase. Goodbye, big thick books that look good on my shelf and make me feel smart because I own them—but let’s be honest, I’m never going to read Infinite Jest. I tried. It’s unreadable. I read Gravity’s Rainbow—goodbye—and, frankly, wish I hadn’t, don’t remember what it’s about, and I’ll never get that time back.

Goodbye, all of Jeanette Winterson’s not Sexing the Cherry books. Goodbye, gifted books that missed the mark—goodbye, self-bought books that I read, don’t remember, will never read again. Goodbye, books I once loved but don’t anymore—that cull was the hardest.

What’s left was still heavy to move and comprises about ten shelf equivalents. But each of these books is loved. Important.

Like The Letters of Sylvia Plath and this little known book of the poet’s drawings:

I don’t actually own Plath’s The Bell Jar or Ariel. How is this possible? Note to self: must buy. Response to self: this is how it beings, hoarding, pack-ratting expansion. Don’t do it. Response to response to self: Shut up. I want my Sylvia.

All of my Polish books:

Some of these have travelled the world with my parents and me for almost forty years. The Polish translation of A.S. Lindgren’s Children from Bullerbyn (which used to belong to my dad’s sister, actually—she got it and read it the year I was born) and of Winnie The Pooh—the first “chapter” books I ever read. And, of course, Sienkiewicz, Mickiewicz, Orzeszkowa, Rodziewiczówna. Kapuścinski. The more modern poets: Zagajewski, Anna Świrszczyńska and Wisława Szymborska, not in translation.

This cultural heritage of mine, I have a very… fraught, complex relationship with. So much beauty, so much passion, so much suffering—so much stupidity, so much pain.

Governments do not define a national, a culture, or a people, I suppose. But in a democracy, they reflect the will and the hearts of the majority of the people, and, if the current government of Poland reflects the majority of the will and the hearts of the (voting) Polish people, they are repugnant to me and I want nothing to do with them. I am ashamed of them, of where I come from.

But I do come of them, from there, do I not?

Still. I keep the books. Including the one celebrating our first modern proto-fascist, Józef Piłsudski. History is complicated; ancestry not chosen.

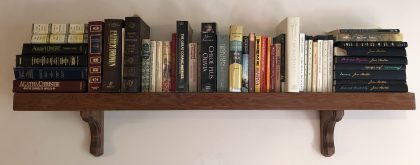

Next, a shelf of all of my favourites.

All of Jane Austen, of course. Most of Nabokov. Virginia Woolf, because, well, it’s complicated. Susan Sontag’s On The Suffering of Others, and E.M. Forester’s Maurice—I gave up Room With a View and the others. J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, not so much because I’ll ever read it again but because it was so important back then. Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, because nothing like it has been written before or since. Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas—I mean. I had to keep it, hero of my misspent university youth. I put him right next to Charles Bukowski’s Women, which isn’t great, but which… well. It taught me a lot about writing. Then, Jorge Luis Borges’ The Book of Imaginary Beings, which always makes me cry because a) it exists and b) I will never write that well.

Edward Said’s Orientalism, the only book to survive my “why the fuck did I keep all of these outdated anthropology and sociology and history textbooks for 25 years” purge. Margaret Mead’s New Lives for Old, which wasn’t one of them, but a later acquisition, kept in honour of the woman who dared live her life, do her thing. She wasn’t the smartest, the brightest, the most original—but fuck, she dared. Fraser’s The Golden Bough and Lilian Faderman’s Chloe Plus Olivia, both acquired in my teens—the first gave me religion for a while, while I freed myself of the Polish Catholicism in which I grew up (“freed” is an aspirational word; I suspect the religions we are indoctrinated into in childhood stay in our bones forever—the best that we can do is be aware when that early programming tries to sabotage our critical thinking and emotional well-being), and the second showed me I wasn’t a freak, an aberration, alone.

Next, The First Ms. Reader and the Sisterhood is Powerful anthology—original 1970s paperbacks bought in a used bookstore in the 1990s when I was discovering feminism. Monica Sjöö and Barbara Mor’s The Great Cosmic Mother—I suppose another Wicca-feminism vestige. I will never read it again, but way back when, that book changed my life, so. Here it is, with me, still.

And now, back to fiction: The Doorbell Rang, my only Rex Stout hardcover, although without the dust jacket, and a hardcover, old, maybe even worth something, with protected dust jacket intact, of P.G. Wodehouse’s Psmith, Journalist. Next to them, The Adventures of Romney Pringle and The Further Adventures by Romney Pringle, the single collaboration between R. Austin Freeman and John J. Pitcairn under the pseudonym of Clifford Ashdown. Written in 1902 or so, both volumes are the first American edition. In mint condition. Like the P.G. Wodehouse—and The Letters of Sylvia Plath, and the unique, autographed, bound in leather made from the butts of sacrificed small children or something, Orson Scott Card Maps in the Mirror short story collection, which is next-but-one to them on the bookshelf—they were a gift from Sean.

A lot of the books on my shelves, here with me now, are a gift from Sean.

Between them, a hard cover Georges Simeon found at a garage sale, and then G.K. Chesterton—Lepanto, the poem about the 1571 naval battle between Ottoman forces and the Holy (that’s what they called themselves) League of Catholic Europe, which I will never read again, but which is associated with a specific time and event in my personal history, so I keep it. Next to it, The Collected Stories of Father Brown, in battered hardcover, which I re-read intermittently, and which are—well. Perfect, really. Then, all of Dashiell Hammett in one volume. Then, almost all the best Agatha Christie’s in four “five complete novels” hardcover collections, topped with two multi-author murder mystery medleys from the 1950s.

Looking at this shelf makes me very, very happy.

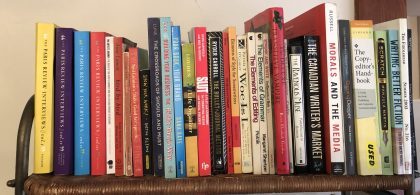

Next, the one fully preserved collection. Before the move, these books lived on a bookshelf perched on top of my desk. Now, they are here, their “natural” order slightly altered because of the uneven height of this case’ shelves. The top shelf is, I suppose, mostly reference and writing books:

The Paris Review Interviews, Anne Lammott’s Bird by Bird, Neil Gaiman’s Make Good Art, Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, and their ilk. At the end, a couple of publications in which I have a byline.

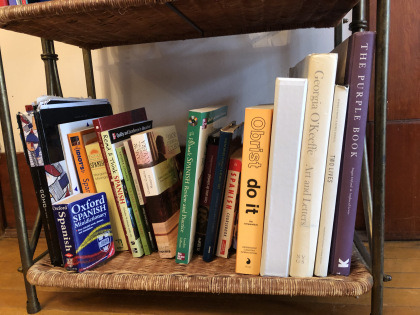

The next shelf, the smallest on the case, is a bit of a smorgasboard, but is very precious to me:

Do you see Frida and my Tarot cards? Also an Ariana Reines book that I really should give back to its owner…

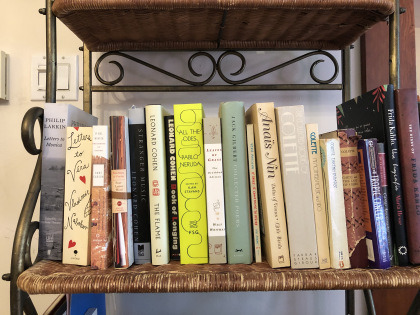

Next, my perhaps most precious books.

Philip Larkin’s Letters to Monica and Nabokov’s Letters to Vera. Anne Carson’s If Not Winter: Fragments of Sappho. Four Letter Word, a collection of “original love letters” (short stories, they mean, pretentious fucks) from an assortment of mega-stars, including Margaret Atwood, Leonard Cohen, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Neil Gaiman, Ursula K. LeGuin… a strange assortment, really. But some lovely pieces in there. Some lame ones too—and I like that too. Even superstars misfire, every one in a while.

Then, Leonard Cohen, Pablo Neruda, Walt Whitman, Jack Gilbert, Vera Pavlova. Finally, Anaïs Nin’s Delta of Venus and Little Birds, and a bunch of battered Colettes. Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer right next to Colette, of course. Then, my Frida books.

The next shelf is full of aspirational delusions.

Farsi textbooks next to Hafez, Rumi and Forough Farrokzad translations. I will never be able to read Hafez in the original Persian. But maybe? Life is long. Maybe, one day, I will have time. Then, Jung’s Red Book, Parker J. Palmer’s A Hidden Wholeness, Rod Stryker’s The Four Desires, Stephen Cope’s The Great Work of Your Life, Thich Nhat Hahn’s The Art of Communicating (I failed), The Bhagavad Gita (still trying).

As I said, the shelf of delusions.

The bottom shelf is aspirational/inspirational, and also, very tall.

And so, that’s why my Georgia O’Keefe books are there, as well as The Purple Book, and Obrist’s do it manifesto. Perhaps there is room there for my leather-bound Master’s thesis, currently tucked away in the closet, right there, next to a course binder from SAIT? Then, all of my Spanish books, including Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s El Amor en los Tiempos del Cólera… which, also, one day, I will read in Spanish and actually understand. Life is long, right?

Next, not really a book shelf as such, but the top shelf of my secretary desk, where the reference and project books of the moment live.

The Canadian Press Stylebook has a permanent home here, of course. And I’ve got two copies of Canadian Copyright: A Citizen’s Guide there, one for me (unread, but I’ll get to it, I promise myself, again), one for a colleague. Both snagged from a Little Free Library, by the way.

Almost done.

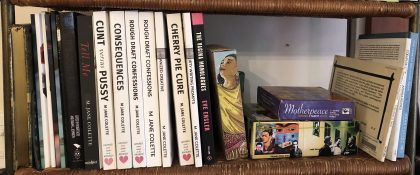

In the bedroom, the books of vice.

A shelf of battered Ngaio March paperbacks, tucked beside them some meditation and Kundalini yoga books that I’m not using right now, but, maybe, one day, I am not ready to give up on this part of myself yet. Below, a shelf of even more battered Rex Stout paperbacks.

I read and re-read these books—as did their original owners—until they fall to pieces. They are my crack, my vice—also, my methadone, my soother.

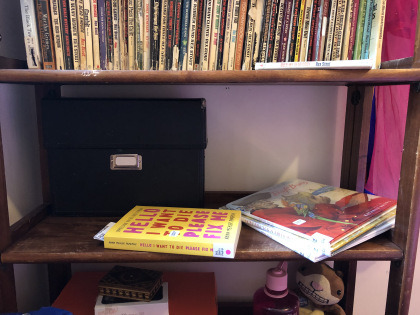

Below them, space for library books, mine and Ender’s:

I am finding Anna Mehler Paperny’s Hello I want to Die Please Fix Me unreadable, by the way. I pick it up, put it away. Repeat.

Will likely return it to the library unread.

Currently not on display: books by friends. Some here with me, some on the shelves in the Co-op house. There are a lot of those. Can one be ruthless… with friends?

ii. A reflection

Books, for readers and writers, are the artifacts that define us. When I enter a reader’s home, I immediately gravitate to their bookshelves. What’s on them?

What’s not on them?

What I’ve chosen to let go of, to not bring with me here tells me… a lot.

What am I going to do with this information?

xoxo

“Jane”

Books in the Time of Corona: what’s on my shelves and what’s not, and the story it tells First, an apology for the title slug. I know you're all sick and tired of plays on…

0 notes

Text

187 #ClimateMayors adopt, honor and uphold #ParisAgreement goals

Badman Nishioka/3rd report /1st 62 Mayors, 2nd 88 Mayors, 3rd: The 187 US Mayor's commit to adopt, and uphold Paris Agreement!

HP: Climate Mayors

U.S. #Climate Mayors working together to advance local climate action, national emission reduction policies, & the Paris Climate Agreement www.climate-mayors.org. Jun 2

187 US Climate Mayors commit to adopt, honor and uphold Paris Climate Agreement goals

STATEMENT FROM THE CLIMATE MAYORS IN RESPONSE TO PRESIDENT TRUMP’S WITHDRAWAL FROM THE PARIS CLIMATE AGREEMENT June 1st 2017

The President’s denial of global warming is getting a cold reception from America’s cities.

As 187 US Mayors representing 52 million Americans, we will adopt, honor, and uphold the commitments to the goals enshrined in the Paris Agreement. We will intensify efforts to meet each of our cities’ current climate goals, push for new action to meet the 1.5 degrees Celsius target, and work together to create a 21st century clean energy economy.

We will continue to lead. We are increasing investments in renewable energy and energy efficiency. We will buy and create more demand for electric cars and trucks. We will increase our efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions, create a clean energy economy, and stand for environmental justice. And if the President wants to break the promises made to our allies enshrined in the historic Paris Agreement, we’ll build and strengthen relationships around the world to protect the planet from devastating climate risks.

The world cannot wait — and neither will we.

Sign

*Mayor Eric Garcetti, City of Los Angeles, CA/

*Mayor Martin J Walsh, City of Boston, MA/

*Mayor Bill de Blasio, New York City, NY/

*Mayor Sylvester Turne, City of Houston, TX/

*Mayor Madeline Rogero, City of Knoxville, TN/

*Mayor Rahm Emanuel, City of Chicago, IL/

*Mayor Ed Murray, City of Seattle, WA/

*Mayor Jim Kenney, City of Philadelphia, PA/

*Mayor Kasim Reed, City of Atlanta, GA/

*Mayor Lioneld Jordan, City of Fayetteville, AR/

*Mayor Trish Herrera Spencer, City of Alameda, CA/

*Mayor Kathy Sheehan, City of Albany, NY/

*Mayor Allison Silberberg, City of Alexandria, VA/

*Mayor Jeanne Sorg, City of Ambler, PA/

*Mayor Ethan Berkowitz, City of Anchorage, AK/

*Mayor Terence Roberts, City of Anderson, SC/

*Mayor Christopher Taylor, City of Ann Arbor, MI/

*Mayor Van W Johnson, City of Apalachicola, FL/

*Mayor Susan Ornelas, City of Arcata, CA/

*Mayor Esther Manheimer, City of Asheville, NC/

*Mayor Steve Skadron, City of Aspen, CO/

*Mayor Steve Adler, City of Austin, TX/

*Mayor Gordon Ringberg, City of Bayfield, WI/

*Mayor Jesse Arreguin, City of Berkeley, CA/

*Mayor William Bell, City of Birmingham, AL/

*Mayor Ron Rordam, City of Blacksburg, VA/

*Mayor John Hamilton, City of Bloomington, IN/

*Mayor Dave Bieter, City of Boise, ID/

*Mayor Suzanne Jones, City of Boulder, CO/

*Mayor Carson Taylor, City of Bozeman, MT/

*Mayor Eric Mamula, Town of Breckenridge, CO/

*Mayor Lori S. Liu, City of Brisbane, CA/

*Mayor Brenda Hess, City of Buchanan, MI/

*Mayor Byron W Brown, City of Buffalo, NY/

*Mayor Miro Weinberger, City of Burlington, VT/

*Mayor E Denise Simmons, City of Cambridge, MA/

*Mayor Lydia Lavelle, City of Carrboro, NC/

*Mayor Pam Hemminger, City of Chapel Hill, NC/

*Mayor John J Tecklenburg, City of Charleston, SC/

*Mayor Jennifer Roberts, City of Charlotte, NC/

*Mayor Andy Berke, City of Chattanooga, TN/

*Mayor Mary Casillas Salas, City of Chula Vista, CA/

*Mayor Brian Treece, City of Columbia, MO/

*Mayor Stephen K Benjamin, City of Columbia, SC/

*Mayor Brian Tobin, City of Cortland, NY/

*Mayor Biff Traber, City of Corvallis, OR/

*Mayor Jeffrey Cooper, Culver City, CA/

*Mayor Mike Rawlings, City of Dallas, TX/

*Mayor Robb Davis, City of Davis, CA/

*Mayor Cary Glickstein, City of Delray Beach, FL/

*Mayor Michael Hancock, City of Denver, CO/

*Mayor Frank Cownie, City of Des Moines, IA/

*Mayor Josh Maxwell, City of Downingtown, PA/

*Mayor Roy D Buol, City of Dubuque, IA/

*Mayor William V Bell, City of Durham, NC/

*Mayor Kris Teegardin, City of Edgewater, CO/

*Mayor David Kaptain, City of Elgin, IL/

*Mayor Lucy Vinis, City of Eugene, OR/

*Mayor Stephen H Hagerty, City of Evanston, IL/

*Mayor Coral J Evans, City of Flagstaff, AZ/

*Mayor Jack Seiler, City of Fort Lauderdale, FL/

*Mayor Tom Henry, City of Fort Wayne, IN/

*Mayor Karen Freeman-Wilson, City of Gary, IN/

*Mayor Rosalyn Bliss, City of Grand Rapids, MI/

*Mayor Nancy Vaughan, City of Greensboro, NC/

*Mayor Joy Cooper, City of Hallandale Beach, FL/

*Mayor Luke Bronin, City of Hartford, /

*Mayor Peter Swiderski, City of Hastings-on-Hudson, NY/

*Mayor Nancy R. Rotering, City of Highland Park, IL/

*Mayor Gayle Brill Mittler, City of Highland Park, NJ/

*Mayor Tom Stevens, Town of Hillsborough, NC/

*Mayor Dawn Zimmer, City of Hoboken, NJ/

*Mayor Josh Levy, City of Hollywood, FL/

*Mayor Alex B Morse, City of Holyoke, MA/

*Mayor Paul Blackburn, City of Hood River, OR/

*Mayor Josh Levy, City of Hollywood, FL/

*Mayor Candace B Hollingsworth, City of Hyattsville, MD/

*Mayor Svante Myrick, City of Ithaca, NY/

*Mayor Steven M Fulop, Jersey City, NJ/

*Mayor Sly James, Kansas City, MO/

*Mayor Nina Jonas, City of Ketchum, ID/

*Mayor Steve Noble, City of Kingston, NY/

*Mayor Adam Paul, City of Lakewood, CO/

*Mayor Michael Summers, City of Lakewood, OH/

*Mayor Christine Berg, City of Lafayette, CO/

*Mayor Richard J Kaplan, City of Lauderhill, FL/

*Mayor Mark Stodola, City of Little Rock, AR/

*Mayor Robert Garcia, City of Long Beach, CA/

*Mayor Dennis Coombs, City of Longmont, CO/

*Mayor Marico Sayoc, City of Los Gatos, CA/

*Mayor Paul R Soglin, City of Madison, WI/

*Mayor Kirsten Keith, City of Menlo Park, CA/

*Mayor Tomas Regalado, City of Miami, FL/

*Mayor Philip Levine, City of Miami Beach, FL/

*Mayor Gurdip Brar, City of Middleton, WI/

*Mayor Daniel Drew, City of Middletown, CT/

*Mayor Reuben D. Holober, City of Millbrae, CA/

*Mayor Jeff Silvestrini, City of Millcreek, UT/

*Mayor Tom Barrett, City of Milwaukee, WI/

*Mayor Mark Gamba, City of Milwaukie, OR/

*Mayor Betsy Hodges, City of Minneapolis, MN/

*Mayor Mary O’Connor, City of Monona, WI/

*Mayor John Hollar, City of Montpelier, VT/

*Mayor Timothy Dougherty, City of Morristown, NJ/

*Mayor Fred Courtright,City of Mount Pocono, PA/

*Mayor Ken Rosenberg, City of Mountain View, CA/

*Mayor Megan Barry, City of Nashville, TN/

*Mayor Ras Baraka, City of Newark, NJ/

*Mayor Jon Mitchell, City of New Bedford, MA/

*Mayor Toni N Harp, City of New Haven, CT/

*Mayor Mitch Landrieu, City of New Orleans, LA/

*Mayor Francis M. Womack, North Brunswick Township, NJ/

*Mayor Donna D Holaday, City of Newburyport, MA/

*Mayor Setti Warren, City of Newton, MA/

*Mayor David J. Narkewicz, City of Northampton, MA/

*Mayor Jennifer White, City of Nyack, NY/

*Mayor Libby Schaaf, City of Oakland, CA/

*Mayor Cheryl Selby, City of Olympia, WA/

*Mayor Buddy Dyer, City of Orlando, FL/

*Mayor Greg Scharff, City of Palo Alto, CA/

*Mayor Jack Thomas, Park City, UT/

*Mayor Greg Stanton, City of Phoenix, AZ/

*Mayor William Peduto, City of Pittsburgh, PA/

*Mayor Ted Wheeler, City of Portland, OR/

*Mayor Liz Lempert, City of Princeton, NJ/

*Mayor Jorge O Elorza, City of Providence, RI/

*Mayor Nancy McFarlane, City of Raleigh, NC/

*Mayor John Marchione, City of Redmond, WA/

*Mayor John Seybert, Redwood City, CA/

*Mayor Hillary Schieve, City of Reno, NV/

*Mayor Tom Butt, City of Richmond, CA/

*Mayor Levar Stoney, City of Richmond, VA/

*Mayor Daniel Guzzi, City of Rockwood, MI/

*Mayor Mike Fournier, City of Royal Oak, MI/

*Mayor Darrell Steinberg, City of Sacramento, CA/

*Mayor Christopher Coleman, City of Saint Paul, MN/

*Mayor Kim Driscoll, City of Salem, MA/

*Mayor Jackie Biskupski, Salt Lake City, UT/

*Mayor Kevin Faulconer, City of San Diego, CA/

*Mayor Ed Lee, City of San Francisco, CA/

*Mayor Sam Liccardo, City of San Jose, CA/

*Mayor Pauline Russo Cutter, City of San Leandro, CA/

*Mayor Heidi Harmon, City of San Luis Obispo, CA/

*Mayor Miguel Pulido, City of Santa Ana, CA/

*Mayor Helene Schneider, City of Santa Barbara, CA/

*Mayor Lisa M. Gillmor, City of Santa Clara, CA/

*Mayor Javier M Gonzales, City of Santa Fe, NM/

*Mayor Ted Winterer, City of Santa Monica, CA/

*Mayor Chris Lain, City of Savanna, IL/

*Mayor Scott A Saunders, City of Smithville, TX/

*Mayor Joe Curtatone, City of Somerville, MA/

*Mayor Pete Buttigieg, City of South Bend, IN/

*Mayor Philip K Stoddard,City of South Miami, FL/

*Mayor Domenic J Sarno, City of Springfield, MA/

*Mayor Lyda Krewson, City of St Louis, MO/

*Mayor Len Pagano, City of St Peters, MO/

*Mayor Rick Kriseman, City of St Petersburg, FL/

*Mayor Michael Tubbs, City of Stockton, CA/

*Mayor Glenn Hendricks, City of Sunnyvale, CA/

*Mayor Michael J Ryan, City of Sunrise, FL/

*Mayor Daniel E Dietch, City of Surfside, FL/

*Mayor Stephanie A Miner, City of Syracuse, NY/

*Mayor Marilyn Strickland, City of Tacoma, WA/

*Mayor Kate Stewart, City of Takoma Park, MD/

*Mayor Andrew Gillum, City of Tallahassee, FL/

*Mayor Bob Buckhorn, City of Tampa, FL/

*Mayor Jim Carruthers, Traverse City, MI/

*Mayor Eric E Jackson, City of Trenton, NJ/

*Mayor Jonathan Rothschild, City of Tucson, AZ/

*Mayor Shelley Welsch, University City, MO/

*Mayor Diane Marlin, City of Urbana, IL/

*Mayor Dave Chapin, City of Vail, CO/

*Mayor Muriel Bowser, City of Washington, D.C./

*Mayor Oscar Rios, City of Watsonville, CA/

*Mayor Edward O’Brien, City of West Haven, CT/

*Mayor John Heilman, City of West Hollywood, CA/

*Mayor Jeri Muoio, City of West Palm Beach, FL/

*Mayor Christopher Cabaldon, City of West Sacramento, CA/

*Mayor Daniel Corona,City of West Wendover, NV/

*Mayor Thomas M Roach, City of White Plains, NY/

*Mayor Debora Fudge, City of Windsor, CA/

*Mayor Allen Joines, City of Winston Salem, NC/

*Mayor Angel Barajas, City of Woodland, CA/

*Mayor Joseph M Petty, City of Worcester, MA/

*Mayor Mike Spano, City of Yonkers, NY/

*Mayor Amanda Maria Edmonds, City of Ypsilanti, MI

Updated signatories as of 8 AM PT on June 3, 2017

Climate Mayors (aka, Mayors National Climate Action Agenda, or MNCAA) is a network of 200 U.S. mayors — representing over 54 million Americans in red states and blue states — working together to strengthen local efforts for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and supporting efforts for binding federal and global-level policy making. Climate Mayors recently released an open letter to President Trump to oppose his actions thus far against action.

If you would like to sign this statement, or require further information about the Climate Mayors (MNCAA) and its activities please email [email protected] or visit our websitehttp://www.climate-mayors.org.

NOTE 2pm, 6/2: Please note that we are receiving a significant amount of interest from US cities in joining Climate Mayors and we may be delayed in responding to you. Climate ChangeTrumpParis AgreementCitiesGlobal Warming

Climate Mayors U.S. #ClimateMayors working together to advance local climate action, national emission reduction policies, & the Paris Climate Agreement

https://medium.com/@ClimateMayors/climate-mayors-commit-to-adopt-honor-and-uphold-paris-climate-agreement-goals-ba566e260097

1 note

·

View note

Text

Científicos sociales, escolarización y aculturación de inmigrantes en Estados Unidos en el siglo XIX, por Mises Hispano.

[Journal of Libertarian Studies 2, Nº1 (1978): 69-84]

I

Los últimos años han sido testigos de una notable difusión de críticas al sistema de educación pública estadounidense. Aunque los ataques habituales a la calidad de la formación, el carácter de las ofertas del programa y la eficiencia de costes de su funcionamiento continúan siendo la preocupación de muchos, varios críticos han empezado a discutir su mismo carácter y propósitos esenciales, la misma legitimidad de las escuelas tradicionales o comunes.[1] Considerando su monopolio casi total del uso de fondos públicos y su control sobre aproximadamente el 90% de los niños en edad escolar, algunos críticos ven a las escuelas públicas como un instrumento real o potencial del capitalismo corporativo, de la burocracia educativa, de un estado cada vez más manipulador; algunos las ven como instrumentos de homogeneización social, cultural y moral, pensados para debilitar e incluso destruir la diversidad racial, étnica, religiosa y cultural personal. Algunos creen que, aunque los ideólogos de la escuela pública han pretendido conscientemente usarla para promover nuevos valores y para el control social de las diversas masas, las escuelas no han sido capaces de hacerlo en la práctica. Otros creen que el sistema está tan corrompido que defienden la “desescolarización”: la abolición de las escuelas como instituciones sociales, o al menos su independencia del estado. Como protestaba el distinguido anciano estadista de la educación estadounidense, Robert Hutchins:

Nadie tiene palabras amables para la escuela pública, la institución que hace nada se consideraba como la base en nuestra libertad, la garantía de nuestro futuro, la causa de nuestra prosperidad y poder, el bastión de nuestra seguridad y la fuente de nuestra ilustración.[2]

Al disponerse a defender el sistema público escolar, Hutchins trataba de encontrar la justificación básica para la continuidad del monopolio público escolar y llegaba a la conclusión de que:

El propósito de las escuelas públicas no se logra haciéndolas gratuitas, universales y obligatorias. Las escuelas son públicas porque se dedican al mantenimiento y mejora de la república, la res publica: son las escuelas comunes de la comunidad, la comunidad política. Pueden hacer muchas cosas por los jóvenes: pueden divertirles, confortarles, atender su salud, mantenerlos fuera de las calles. Pero no son escuelas públicas salvo que inicien a sus pupilos en una comprensión de lo que significa ser un ciudadano autogobernado o una comunidad política autogobernada.

El Profesor distinguido Russell de educación en la Escuela de Pedagogía de la Universidad de Columbia, Dr. R. Freeman Butts, coincide con Hutchins y es todavía más explícito con respecto al significado total de las escuelas públicas como instrumento del estado:

Lograr un sentido de comunidad es el objetivo esencial de la educación pública. Este trabajo no puede dejarse a los caprichos de los padres individuales ni a pequeños grupos de padres con mentalidad similar, ni a grupos de intereses particulares, ni a sectas religiosas, ni a empresarios privados, ni a especialidades culturales. (…) Creo que el fin principal de la educación pública estadounidense es la promoción de un nuevo civismo apropiado para los principios de una sociedad justa en Estados Unidos y en una comunidad mundial justa. (…) Necesitamos la renovación de un compromiso cívico que busque invertir y superar la tendencia hacia “alternativas” segmentadas y disyuntivas que sirven a intereses estrechos, provincianos o racistas.[3]

La subordinación de Hutchins y Butts del derecho individual a una libertad total en el contenido y medios de su educación parece burlarse de las tradiciones libertarias de la democracia estadounidense y de la realidad del carácter culturalmente plural de la sociedad estadounidense. Parece espiritualmente más cercana a la República de Platón o al totalitarismo moderno que al individualismo y la diversidad racial, religiosa y cultural que caracterizan la realidad de la vida diaria estadounidense. Aun así, el hecho es que Hutchins y Butts están más cercanos y son representativos de una ideología que puede remontarse a los primeros días de la república estadounidense, a algunos de los Padres Fundadores más importantes e influyentes, sobre todo a Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Rush y Thomas Jefferson, los tres firmantes de la Declaración de Independencia y padres de la república estadounidense y del sistema estadounidense de escuelas comunes.

II

La pasión por la homogeneidad en raza, religión y cultura era muy fuerte entre los colonos americanos: la historia del periodo colonial está repleta de conflictos étnicos y religiosos; el carácter multicultural de Nueva York y Pensilvania fue un accidente de la historia o se debió a la influencia de los fundadores cuáqueros de este último estado. Nueva Inglaterra era particularmente poco acogedora para los extranjeros, disidentes religiosos o cualquiera que no se adaptara a el sentimiento oficial de propiedad. Sin embargo, la preferencia por una sociedad homogénea adoptó una importancia mayor después de que la Revolución Americana hubiera unido las dispares sociedades coloniales en una nación con un gobierno y ciudadanía comunes. Aunque eran los hombres más cosmopolitas de su tiempo, Franklin, Rush y Jefferson, compartían el disgusto y temor de sus contemporáneos por una cultura heterogénea en América.

Benjamin Franklin fue el primer americano que ideó y propuso una unión voluntaria de las colonias británicas americanas. Su plan se exponía en una carta enviada a su socio comercial en 1751 y luego apareció de una manera más elaborada en 1755 como un panfleto que sería distribuido a los miembros de la American Philosophical Society, el principal grupo de científicos y filósofos políticos, sociales y naturales de América, que había fundado el propio Franklin y en el cual Jefferson y Rush serían posteriormente miembros activos. Es importante indicar que fue en este panfleto, explicando su visión de una unión americana, en el que Franklin elige argumentar en contra de cualquier inmigración adicional de pueblos no ingleses a las colonias americanas. Su objetivo concreto eran los colonos alemanes de Pennsylvania, que habían obstaculizado los esfuerzos de Franklin para crear defensas militares en la colonia, al unirse a los cuáqueros en rechazar votar a favor de una propuesta legal militar en la asamblea. Franklin reclamaba a sus lectores:

¿Por qué deberían sufrirse a los patanes del Palatinado entrando en nuestras colonias y, agrupándose, establecer su idioma y costumbres excluyendo los nuestros? ¿Por qué debería Pennsylvania, fundada por los ingleses, convertirse en una colonia de extranjeros, que serían tan numerosos como para germanizarnos, en lugar de anglificarse?[4]

Pero este exabrupto era más que un brote de rencor: era parte de una hostilidad consciente contra el carácter multiétnico de la sociedad de Pennsylvania, que la Nueva Inglaterra en la que nació y creció Franklin no podía aceptar del todo. Era asimismo un reflejo de su racismo anglosajón, que se expresaban muy claramente en ese mismo panfleto:

El número de personas blancas en el mundo es proporcionalmente muy pequeño. Toda áfrica es negra o leonada; Asia principalmente leonada; América (aparte de los recién llegados) casi igual de completamente. Y en Europa los españoles, italianos, franceses y rusos y suecos son generalmente de lo que llamamos una complexión atezada, igual que los alemanes, con solo la excepción de los sajones, que en Inglaterra constituyen el grupo principal de personas blancas sobre la faz de la tierra.

Franklin concluía preguntándose por qué los americanos deberían

como seres superiores oscurecer a su pueblo. ¿Por qué aumentar los hijos de África trasplantándolos a América cuando detenemos una oportunidad tan excelente, excluyendo a todos los negros y leonados, de aumentar los queridos rojos y blancos? Tal vez soy parcial con respecto a la composición de mi país, pero esa parcialidad es natural en la humanidad.[5]

Thomas Jefferson, escribiendo más de 30 años después, en medio de la Revolución, expresaba la misma preocupación por los efectos de una posible colonización europea a gran escala de la nueva república estadounidense. Hacia equivaler la unidad política a la homogeneidad cultural y dudaba de que los inmigrantes no ingleses fueran compatibles con el desarrollo con éxito o la supervivencia de una república estadounidense.

Es por la felicidad de aquellos unidos en la sociedad por lo que hay que armonizar, tanto como sea posible, los asuntos que necesariamente deben negociar. Al ser el gobierno civil el único objeto de las sociedades en formación, su administración debe llevarse a cabo por consentimiento común. Todos los tipos de gobierno tienen sus principios concretos. Los nuestros son tal vez más peculiares que los de cualquier otro en el universo. Son una combinación de los principios de la máxima libertad de la constitución inglesa, con otros deducidos del derecho natural y la razón natural. No puede haber nada más opuesto a estos que las máximas de las monarquías absolutas. Por eso tenemos que esperar el máximo número de emigrantes. Traerán con ellos los principios de los gobiernos que han abandonado, imbuidos desde su primera juventud; o, si son capaces de deshacerse de ellos, será a cambio de una licenciosidad sin límites, pasando, como es usual, de un extremo a otro. Sería un milagro que se detuvieran exactamente en el punto de una libertad templada. Estos principios, con su lenguaje, los trasmitirán a sus hijos. En proporción a sus números, compartirán con nosotros la legislación. Infundirán en ella su espíritu, deformarán y sesgarán su dirección y la convertirán en una masa heterogénea, incoherente y perturbada. (…) ¿No pueden nuestro gobierno ser más generoso, más pacífico, más duradero (sin esos emigrantes)?[6]

Las opiniones de Jefferson, tal y como están expuestas en la larga fila anterior de sus Notes on Virginia, resumen sucintamente los miedos y elementos analíticos que aparecerían una y otra vez a lo largo de los siglos XIX y XX siempre que se sometía a debate público la cuestión de la inmigración y la naturalización de extranjeros. El pluralismo étnico, religioso o cultural se veía como una amenaza para la comunidad política. La premonición de Jefferson se citaba frecuentemente. Las visiones contrarias a los extranjeros de Washington, Adams y otros padres fundadores también se usaban. La idea de que Europa era un albañal de vicio, corrupción, ignorancia y despotismo era un lugar común de la mitología estadounidense y los europeos que venían a Estados Unidos se veían como transportistas de estos males.[7]

Las opiniones de Jefferson sobre el lugar de los negros en la sociedad estadounidense también prefiguran el pensamiento de generaciones futuras. Franklin se oponía claramente a una mayor importación de esclavos negros por razones raciales y culturales y prefería personalmente tener sirvientes blancos en lugar de negros en su propiedad y hacia el final de su vida apoyó también la abolición de la esclavitud. Aun así, aparentemente estaba convencido de que los negros libres no podrían no tener alguna supervisión blanca, pues el programa que presentó como presidente de la Sociedad de Pennsylvania para la Abolición de la Esclavitud en 1789 incluía recomendaciones de que la sociedad asumiera la custodia legal de todos los aprendices negros libres, ejerciera la superintendencia de la formación escolar de los negros libres más jóvenes y formara un “comité de inspección que supervisara la moral, conducta general y situación ordinaria de los negros libres”.[8]

Mientras que Franklin apoyaba la supresión del comercio de esclavos y la abolición, Jefferson iba más allá y defendía la eliminación de todos los negros de la sociedad estadounidense. Creía que las “profundas divisiones” entre blancos y negros, si se mantenían en la misma sociedad, producirían convulsiones civiles que no acabarían “más que en el exterminio de una raza por la otra”. Esta violencia potencial se debía a “los prejuicios profundamente arraigados considerados por los bancos, los diez mil recuerdos de los negros de injurias soportadas” y esas “distinciones reales” que ha creado la naturaleza, es decir, color, figura, pelo, olor y características sexuales. Aunque Jefferson pensaba que los negros eran iguales a los blancos en su capacidad de recordar cosas, creía que eran inferiores a los bancos en poder de razonamiento y “aburridos, sin gusto y anómalos en imaginación”. Aunque Jefferson añadía cuidadosamente que la cuestión todavía requería un mayor examen científico, planteaba “la sospecha” de que los negros eran inferiores a los blancos en cuerpo y mente, una opinión que arraigaría cada vez más en la imaginación estadounidense a lo largo del siglo XIX.[9]