#Rorty

Text

They just got done invading EARTH🤡🥊

Itz been a bit since I've done any digital art so here's sumto feed U guyz :o)

Also ship name for these idiots is Sudy or Rorty

This song is them, actually most of alex g's music reminds me of these goofs..

#killer klowns#killer klowns from outer space#kkfos#killer klowns shorty#shorty#killer klowns from outer space fanart#kkfos shorty#rudy#klown#killer klowns rudy#kkfos fanart#kkfos rudy#killer klowns from outer space shorty#killer klowns from outer space rudy#rudy x shorty#shorty x rudy#sudy#rorty#Spotify#killer klowns fanart

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Pragmatism & Truth - Rorty, Putnam, & Conant (2002)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

#philosophy#quotes#Richard Rorty#Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature#Rorty#truth#debate#argument#society#humanity

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

«La concepción que estoy presentando sustenta que existe un progreso moral, y que ese progreso se orienta en realidad en dirección de una mayor solidaridad humana. Pero no considera que esa solidaridad consista en el reconocimiento de un yo nuclear —la esencia humana— en todos los seres humanos. En lugar de eso, se la concibe como la capacidad de percibir cada vez con mayor claridad que las diferencias tradicionales (de tribu, de religión, de raza, de costumbres, y las demás de la misma especie) carecen de importancia cuando se las compara con las similitudes referentes al dolor y la humillación; se la concibe, pues, como la capacidad de considerar a personas muy diferentes de nosotros incluidas en la categoría de “nosotros”. Esa es la razón por la que he dicho, en el capítulo cuarto, que las principales contribuciones del intelectual moderno al progreso moral son las descripciones detalladas de variedades particulares del dolor y la humillación (contenidas, por ejemplo, en novelas o en informes etnográficos), más que los tratados filosóficos o religiosos.»

Richard Rorty: Contingencia, ironía y solidaridad. Ediciones Paidos, pág. 210. Barcelona, 1991

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dies-irae-1

#richard rorty#rorty#contingencia#ironía y solidaridad#moral#progreso moral#ética#solidaridad#yo#yo nuclear#esencia humana#nosotros#diferencia#diferencias#“nosotros”#dolor#humillación#novela#novelas#literatura#etnografía#tratados etnográficos#concepciones universalistas#concepciones esencialistas#concepción historicista#teo gómez otero

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Desde Platón a Rorty y Vattimo, siempre se entendió que había un conflicto entre la democracia y la verdad, y el tema estaba en tomar partido por una u otra, pero el debilitamiento de la verdad está claramente relacionado con el debilitamiento de la democracia que vivimos hoy.

0 notes

Text

Hogyan jutottam ide?

Ez a poszt az elsőre része egy két részből álló írásnak, aminek az az összefogó címe: „Hogyan jutottam ide, és hogyan tovább?” A „Hogyan tovább?” lesz, a következő poszt.

A filozófia húszas éveim elején kezdett el érdekelni. Igazából teljesen sznob módon arra gondoltam, hogy kellene valami filozófiát olvasni, és találtam otthon egy Nietzsche válogatást magyarul. Ezt elolvastam és utána olvastam még Nietzschét, de szerintem akkoriban nem igazán értettem. Ahogy olvastam arra gondoltam, hogy igen, ez rendben van, de nekem, mint villamosmérnök hallgató, valami olyasmi kellene, ami filozófia, de közelebb áll a tudományokhoz. Találtam is ilyet, és eléggé össze-vissza kezdtem el olvasni például Quine-t, Russellt, Wittgensteint, talán pár Frege esszét. Továbbra sem hiszem, hogy igazán értettem is volna, amit olvasok. Russell szerintem érthető volt, legalább is a „A filozófia alapproblémáira” úgy emlékszem vissza, mint jó, érthető olvasmány, bár már részletesen nem emlékszem rá. Persze az „A Denotálásról” elég nehéz írása. Wittgenstein teljesen érthetetlen volt számomra. Quine máig nagyon érdekel, de akkor még nem volt elég háttértudásom, hogy megfelelően megértsem (most sem vagyok benne biztos, hogy ez megvan). Emlékszem például, hogy egy barátom, aki nyelvészhallgató volt mutatta nekem „Az empirizmus két dogmáját”, amit együtt olvastunk el. Valahogy szerintem volt bennünk bizalom, hogy ez fontos, bár nem tudtuk szerintem követni Quine gondolatmentét. Quine hitelességét az is növelte számomra, hogy a nevével a digitális technika tankönyvben is találkoztam, amiben benne volt a „Quine–McCluskey minimalizáció”. Frege esetében máig nem értem miért érdekes probléma a „hajnalcsillag = alkonycsillag”, pontosabban végső soron azt hiszem értem, de itt már kezdett jelentkezni számomra az analitikus filozófiával kapcsolatos bizonyos mértékű kételkedés. Természetesen Frege egy zseni, aki a legfontosabb logikus volt Arisztotelész óta, ehhez kétség sem férhet.

Elkezdtem filozófia témájú kurzusokat is felvenni az egyetemen, ami közül az egyik egy logika kurzus volt. A félév végén a házi feladat az volt, hogy egy filozófia cikkben található érvelést formalizáljunk. Természetesen Quine „Az empirizmus két dogmájához” fordultam, és újfent az analitikus filozófia iránti kételkedésem erőre kapott, amikor kín keservesen megpróbáltam az érveléseket formalizálni, de valahogy azt találtam, hogy pusztán a szigorúan vett formális logika az érveléseknek csak igen csekély részét képes jól megragadni. Szóval eléggé naiv dolognak tűnt számomra, hogy abban bízzunk, hogy a modern logika meg fogja oldani a filozófia problémáit, legalább is én így értelmeztem Russell-t, a korai Wittgensteint és Carnapot, hogy ilyesmiben bíztak.

Alapvetően az foglalkoztatott, hogy miért működnek a természettudományok? Különösen a matematika miért alkalmas a természet leírására? Lenyűgözőnek találtam, hogy a Fourier transzformáció, amivel egy jelet meg lehet jeleníteni frekvencia tartományban, működik, és lehetőséget ad például szűrők tervezésére. Ez az érdeklődésem végül is ahhoz vezetett, hogy egyfajta „végső igazság” birtokába akartam kerülni, amit a tudomány objektivitása fog nekem elhozni. Úgy gondoltam, hogy a fizikai törvényei lesznek ez a fajta végső igazságok és a fizika részecskéi az ontológia. Richard Rorty egészen más formában, de szerintem hasonló indíttatásról ír filozófiai érdeklődésének kezdeteiről a „Trockij és a vad orchideák” című esszéjében. Ő egy olyan látásmódot keresett, ami a személyes különcségeit (a vad orchideák szeretete), és a morális meggyőződéseit (amit Trockij képviselt) egybe foglalja. Ami közös bennünk, bár Rorty sokkal irodalmibb módon fejezi ki, az a menekülés az esetlegességtől, és a végességtől. Az a kvázi-vallásos igény, hogy valami végsőt megértsünk, ami mindennek értelmet ad, és rendet teremt. Végül mindketten csalódtunk: Rorty nem kapta meg a mindent egybefoglaló látásmódot, és én egyre inkább azt kellett, hogy belássam, hogy ha létezne is ez a mindent átfogó fizikai elmélet, az bizonyos szempontból nagyon „kevés” dolgot magyarázna meg. Ez alatt azt értem, hogy a materialista világszemlélet nagyon szegényes, nincsen benne hely sok mindennek, amit az emberiség fontosnak tart. Számomra azonban nem az a megoldás, hogy akkor bővítsük ki az ontológiánkat, értékekkel, számokkal és más absztrakt objektumokkal stb., hanem az, hogy a metafizika, mint kérdésfelvetés elkerülendő. Ez a lelkiállapot nagyon fogékonnyá tett Rorty-ra, és a pragmatizmusra általában is.

Rortytól tanultam azt, hogy elfogadjam a végességet és az esetlegességet, szóval már nem célom a „végső igazságok” kutatása, illetve ehhez kapcsolódóan egyetértek Rorty-val, hogy a filozófia nem tud megalapozni más tudományokat, értékeket (és nincs is erre szükség). Az a vágy, hogy „objektív” megalapozást találjunk, menekülés a végesség elől. („objektív” itt filozófiai értelemben értendő, hogy valami egy az egyben megfelel a valóságnak metafizikai értelemben, és egész biztos, hogy soha nem fog változni. Ha „objektivitás” alatt csak annyi értünk, hogy nagyon alaposan körüljártok a kérdést, és ez tűnik a legjobb megoldásnak jelenleg, akkor nincsen a kifejezéssel problémám.) A tudományok sikerei önmagukért beszélnek, érdekes lehet bizonyos kérdésekről „filozofikusabban” elgondolkodni, például Tim Maudlin két kötetes „Philosophy of Physics” című könyve szerintem nagyon érdekes olvasmány, ami segít megérteni a fizikai elméleteket. (Itt nyilván feltételezem, hogy a filozófus érti, amiről beszél, és nem csak ezoterikus hókuszpókuszra használja a fizikát, amit igazából nem ért.) De nincs szükség és nem is lehet a fizikát filozófiailag megalapozni, szerintem ez ma már nem egy vitatott állítás.

Morális, etikai vagy politikai eszmék tekintetében is egyetértek Rorty-val amikor azt mondja például, hogy a demokrácia az eddigi legjobb ötlet, egy állam működtetésére, de ez egy történelmi szerencse, hogy így alakult, és nem mondjuk, az emberi természet mélyebb megértéséből adódik. A demokrácia működik, a világot sokkal jobbá tette, én nem nagyon látom, ezt hogyan lehetne elvitatni, és ha ez nem elég érv mellette, akkor nem tudom, mi lenne jobb.

A másik kapcsoló vonal a személyes politikai meggyőződésem. Mindig is baloldalinak gondoltam magam, szóval ez megint egy pont, ami közös Rorty és köztem. De szintén húszon éves koromra rájöttem, hogy a politikai nézeteimet nem tudom igazán jól megvédeni, és ezért elkezdtem foglalkozni a politikával és a közgazdaságtannal. Ezen a területen Pogátsa Zoltán írásai segítettek nekem a legtöbbet eligazodni.

#philosophy#filozófia#Rorty#richard rorty#Pogátsa Zoltán#Analitikus Filozófia#pragmatism#pragmatizmus#john dewey

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Before Kant, an inquiry into "the nature and origin of knowledge" had been a search for privileged inner representations. With Kant, it became a search for the rules which the mind had set up for itself (the "Principles of the Pure Understanding"). This is one of the reasons why Kant was thought to have led us from nature to freedom. Instead of seeing ourselves as quasi-Newtonian machines, hoping to be compelled by the right inner entities and thus to function according to nature's design for us, Kant let us see ourselves as deciding (noumenally, and hence unconsciously) what nature was to be allowed to be like. Kant did not, however, free us from Locke's confusion between justification and causal explanation, the basic confusion contained in the idea of a "theory of knowledge."

Richard Rorty, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

#philosophy#quotes#Richard Rorty#Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature#Kant#belief#representation#justification#causality#knowledge#epistemology

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't think you need to have language prior to having concepts, in fact I struggle to find words that exist for emotions and thoughts I have all the time. You're taking the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis entirely too seriously.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

One time—it was the only time I ever taught Lolita!—I assigned a chapter from this book and used the cover, specifically Rorty's facial expression, to explain his philosophy. The tight smile on his face represents his amused resignation to the contingency and irony of the world as celebrated by such playful authors as Nietzsche, Derrida, and Proust, while the unmistakable sorrow in his eyes shows his knowledge of the suffering in the world and the consequent need for solidarity, as called for by such writers as Marx and Mill, Dickens and Orwell—a synthesis of smiling mouth and haunted eyes recapitulated in the subliminally mournful hijinks of Lolita itself. I don't remember if the students were persuaded. I didn't know it when I made the syllabus, but they were all PSEO students and therefore about 16 years old, so, between being assigned Lolita and hearing this kind of thing, I think they were just in a state of, "Whoa...college."

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

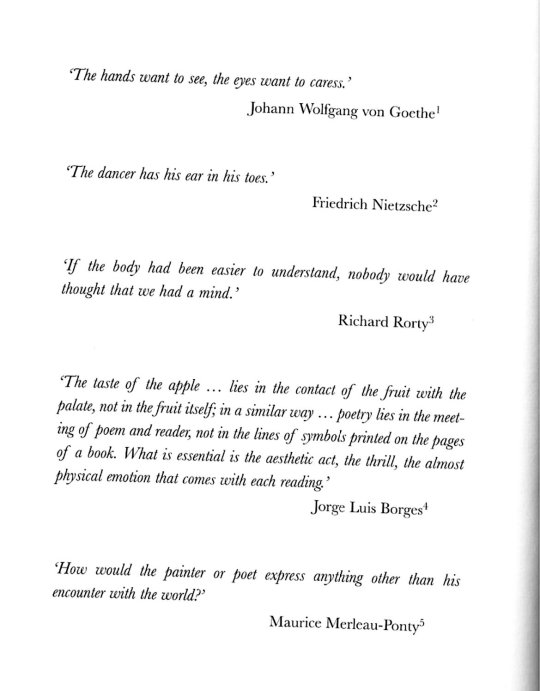

phenomenological epigraphy

Juhani Pallasmaa’s The Eyes of the Skin

also, Sartre’s ocularphobia

#Juhani Pallasmaa#The Eyes of the Skin#johann wolfgang von goethe#friedrich nietzsche#richard rorty#jorge luis borges#maurice merleau ponty#jean paul sartre

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rick and Morty intro

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

#philosophy#quotes#Richard Rorty#Truth and Progress#Rorty#progress#imagination#creativity#rigorousness#accuracy

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

rick and morty but they swapped outfits so now its mick and rorty. thanks for coming to my ted talk.

also i have never seen an arm before in my life. what even is that. an arm? never heard of it. hands? nope. never. also im back on my no background shit. takes too much brain power and i had a bad day today so 🤷♂️.

anyway enjoy!!

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

[5:55] Rorty: “I’ve never been very easy in my dealings with people ...”

[6:30] According to my parents I pretty much taught myself to read when I was four ... and spent most of the rest of my life reading books.

Interviewer: the world in those books. Was it more important to you?

Rorty: Yeah, much more important.The world outside never quite lived up to the books - except for a few scenes in nature. You know, animals, birds, flowers.

Interviewer: What kind of world we're creating by reading books and combining them what kind of picture...?

Rorty: Oh, fantasies of power. Control. Omnipotence. Sort of usual childhood fantasies. Turning out to be the unacknowledged son of the king that kind of thing.

Interviewer: Power through the control - the power you missed in the schoolyard.

Rorty: Yeah. And I think basically I was looking for some way to get back at the schoolyard bullies by turning into some kind of intellectual and acquiring some kind of intellectual power though. I wasn't quite clear how this was going to work.

Interviewer: Did you manage to come back to them as the intellectual?

Rorty: No, I just lost touch with them by living in a world of intellectuals.

---

[8:50]

Interviewer: How’d you become a philosopher?

Rorty: I think philosophy was somewhat accidental, I think that I could equally could’ve become an intellectual historian or literary critic. But it just happened that the course that I was most intrigued by when I was 16 was a philosophy course. So I sort of kept taking more and more philosophy courses and signing up for more and more degrees.

Interviewer: Why were you intrigued?

Rorty: I think because of the sense of mastery and control that you get out of philosophical ideas. You get the impression from reading philosophy that now you can place everything in an order or a neat arrangement. Or something like that. This gratifies one’s need for domination -

Interviewer: - and compensation of the shyness?

Rorty: Yeah.

Interviewer: I remember that there are many people participating in consolation. If I asked them, what is consolation ... they come up with the sense of order. The sense to have the whole chaotic world in your hand, to control it, to name it...

Rorty: I guess I don't associate that with beauty. I think of it as something much more like power ... I think of beauty as sensuous, and philosophical ideas in the usual cliched terms: cold, hard, abstract.

---

[10:52]

Interviewer: What were you critically discovering the time you went into philosophy? Because you had the illusion of having power,

Rorty: Well I was hoping to, anyway, by reading enough philosophy. When I was 16, I read through Plato thinking, you know, if I read everything in Plato, I would sort of get the, the essential Plato and be in command of this sprawling mess of dialogue. And of course, it didn't work out that way because Plato was too good an author to let himself be controlled, but it was a good try.

And then I just kept on going, reading, reading philosophy books, until it was too late to do anything else. When I was 20, I had a master's in philosophy and couldn't think of anything to do except take it to Oxford. And then once I got a doctorate in philosophy, there wasn't much to do except teach philosophy.

Interviewer: But you wanted to be in control. You were the shy boy from school, still...

Rorty: Yes.

---

[12:07]

Interviewer: When did you realize you shouldn’t have...?

Rorty: Oh, sometime in my 20s when I began to think that philosophical ideas were, so to speak, ingenious artifacts rather than levers of power.

Interviewer: Was this a dramatic moment because I can imagine if you have your illusions about philosophy as a kind of ‘ordering the world’ and to lead your own chaotic world, to have any on hand to discover that you're just playing with toys and not -

Rorty: it's not exactly just - it wasn't the sense of just playing with toys. But having the feeling that philosophical systems were more like, writing sub systems was more like contributing to a literary genre than, like, assuming command of the universe. And no it wasn't anything very sudden. I mean, just somewhere between the age of 20 and the age of 35. I couldn't tell you where.

Interviewer: And what happened once you realized it didn't say ‘I quit.’

Rorty: No. I mean, it was my bread and butter.

Interviewer: But is it that simple?

Rorty: Sure, I mean. Teaching philosophy is a very agreeable occupation. You get a lot of spare time it pays well, you can do pretty much what you want, especially after you get tenure. It never occurred to me to totally change my life. But I began writing somewhat different kinds of stuff. And eventually it got more and more different as the years went by. I never found philosophy books consolatory - except in the sense of occasionally being overwhelmed by a surge of admiration for a particular philosophical work and thinking ‘what a what a brilliant imagine the creation. How nice to be in the same world where people can create something like this, and to be able to appreciate what they've done.’

Interviewer: But, this is not consolation ...?

Rorty: Yeah, it's not consolation for loss or despair or anything. It's just consolatory works tend to be poetic or fictional achievements more than philosophical works.

---

[21:09]

Idon't want to talk about the uncertainty inherent in the life of every human being I mean some human beings leadquite certain predictable lives you know people in traditional societies peoplein such miserable conditions that they have to work 14 hours a day and sleep the rest now there isn't muchuncertainty around and I think that uncertainty in the sense in whichphilosophers dramatize uncertainty is a luxury it's the kind of thing you candeliberately induce in yourself for the sheer thrill of it by reading lots ofdifferent books and being uncertain about which are them to believe

---

[22:37] Greek (Platonic philosophy) vs pragmatic philosophy

The Greek idea is that at a certain point in the process of inquiry you come to rest because you've reached the goal. And the pragmatists are saying we haven’t the slightest idea what it would be like to reach the goal. The idea that the aim of inquiry is correspondence to reality, or seeing the face of God, or substituting facts for interpretations, is one that we just can't make any use of. All we really know about is how to exchange justifications of our beliefs and desires with other human beings, and as far as we can see that will be what human life will be like forever. So pragmatists regard the Platonist attempt to get away from time into eternity or get away from conversation into certainty as a product of an age of human history where life on earth was so desperate and it seems so unlikely that life could ever be better that people took refuge in another world. Pragmatism comes along with things like the French Revolution Industrial Technology - all the things that made the 19th century believe in progress. When you think that the aim of life is to make things better for our descendants rather than to reach outside of history and time, it alters your sense of what philosophy is good for. In the Platonist and theistic epoch, the point of philosophy was to get you out of this mess into a better place - God, the realm of Platonic ideas the kind of the contemplatively something like that and the reaction against this Greek-Christian pursuit of blessedness through union with a natural order is to say there isn't any natural order but there is the possibility of a better life for your great-great-great-grandchildren. And that's enough to give you all the meaning or inspiration you need.

---

[24:58]

Hans Bloomberg had a remark that impressed me enormously. said at some point we stopped hoping for immortality and in place started hoping for our great-great-grandchildren. You know this was a sort of turn in the culture of the West, and you know, I really believe that. I think that it had to do with simple improvement of material conditions. When we got a comfortable bourgeois existence for large numbers of people the bourgeois was able to think not about escapefrom the world and pie-in-the-sky but about creating a future world for future mortals. That seems to me a great improvement.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

being a person whose first instinct is to categorize and analyse everything logically in a stereotypical sense of the word and at the same time being aware that the Truth "isn’t out there", somewhere in the world objectively, is truly a curse

#like i cannot explain to people how my brain works#like i can give a justification for something but it will never be enough#truth is only in sentences babey#richard rorty#friedrich nitzsche#philosophy#epistemology#philosopher problems lmao#3 am thoughts#insomnia ramblings#mine#philosophy textpost

3 notes

·

View notes