#Shuihu zhuan

Note

I wanted to ask, is it quite likely that Sun Wukong killed heavenly soldiers or is it more pure speculation? I sent this ask before, but my old account is having problems with the messages and asks I send. If not, then I hope my question doesn't come across as me being impatient.

To my knowledge, the novel doesn't mention Monkey killing any gods, only demons, spirits, animals, and humans. Any divine figures, be they deities-turned-spirits or holy mounts, are usually reintegrated into the celestial hierarchy and not killed.

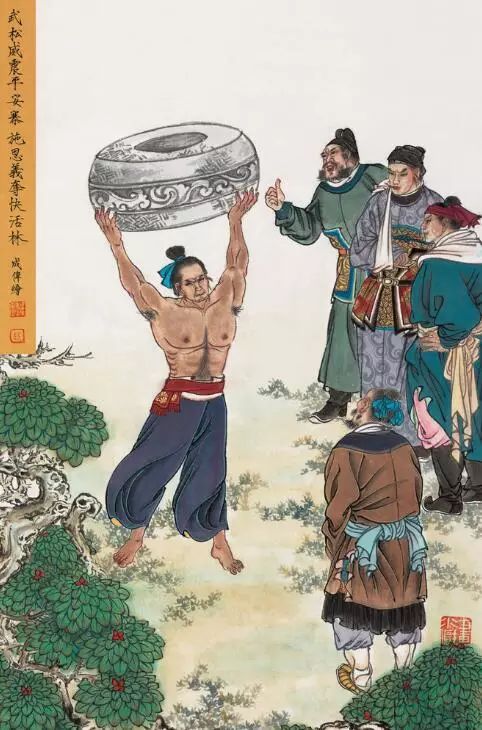

Also, I don't recall the novel describing Wukong fighting the regular rank-and-file soldiers. The 100,000 soldiers mainly man the heavenly nets creating the cordon around Flower-Fruit Mountain. Monkey only fights high-ranking officers. It's like that in a lot of Chinese fiction. A common trope in Romance of the Three Kingdoms (c. 14th-century) and the Water Margin (c. 1400) is that the appearance, scream, and/or fighting ability of a great warrior is enough to hold hundreds or even thousands of foot soldiers at bay while he battles an opposing officer.

But realistically speaking, the Great Sage would have mowed through the regular soldiers like a sith lord through younglings.

#Sun Wukong#Monkey King#Journey to the West#JTTW#warfare#heavenly combat#Romance of the Three Kingdoms#Water Margin#Shuihu zhuan#Sanguo yanyi#Xiyouji#Lego Monkie Kid#LMK

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Selections from Hongmei Sun’s “Transforming Monkey”

Here it is! My compilation of quotes that I particularly liked from Sun’s excellent overview of the figure of the Monkey King. I hope you all enjoy them and find that they give you a richer understanding of an amazing text and its amazing monkey

---

Sun, Hongmei. Transforming Monkey: Adaptation & Representation of a Chinese Epic. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018.

3: “Sun Wukong, known as the Monkey King in English, is the protagonist of the Ming dynasty novel Journey to the West (Xiyou ji). He is famous for his ability to shape-shift and ride the clouds, his size-changing magic rod, and his love of playing tricks. The longevity of his story reflects his popularity in Chinese culture: the ‘Journey to the West’ narrative is among the most malleable and long-lasting in Chinese literary history. With the repeated adaptations of the narrative over the centuries, the image of the protean monkey character has evolved into the Monkey King we know today.

Journey to the West is a one-hundred-chapter novel published in the sixteenth century during the late-Ming period. It is considered one of the four masterworks of the Ming novel, along with Water Margin (Shuihu zhuan), Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi), and The Plum in the Golden Vase (Jinping mei). Loosely based on the historical journey of the famous monk Xuanzang (602-664), who traveled in the Tang dynasty from China to India in search of Buddhist scriptures, the story experienced a series of adaptations over hundreds of years before it was developed into the full-length novel, which recounts a mythological pilgrimage of the monk Tripitaka (the fictional Xuanzang), accompanied by three disciples and protectors he converts along the way: Sun Wukong (aka the Monkey King, or Monkey), Zhu Bajie (aka Zhu Wuneng, Pigsy, or Pig), and Sha Wujing (aka Sha Seng, Sha Heshang, Friar Sand, or Sandy). These disciples, as well as a dragon prince who transforms into a white horse as Tripitaka’s steed, are demons or animal spirits who have sinned…”

4: “Along the way, the group encounters and overcomes eighty-one tests, most of which involve demons and spirits who want to capture Tripitaka and eat his flesh in order to gain immortality.

The history of Journey to the West represents a process of continuous adaptations of Xuanzang’s story. The historical trip becomes a mythological journey in a world full of demons, spirits, Taoist gods, and Buddhist celestials. At some point—the actual origin and provenance remain unclear—the monkey follower of Xuanxang was added to a retelling of the story. Once included, the monkey figure grew in popularity until he replaced the monk as the main character and protagonist. It is owing to the long process of adaptation that today the Monkey King remains popular globally.”

5: “Literary analyses of the text have taken diverse and heterogeneous approaches but have predominantly focused on the religious and allegorical meanings of the tales. Little has been written about the Monkey King image in contemporary settings from the approach of adaptation, despite the obvious importance of this approach for Journey to the West, which is the product of repeated adaptations and maintains its influence in popular culture through ongoing adaptation today. Journey to the West is an accretive text, shaped by many hands at many times, and through interactions with many audiences.”

6: “…for lack of new data and more convincing interpretation, the Shidetang edition printed in 1592 is generally considered the ‘original.’ Although it is now generally accepted that Wu Cheng’en (ca. 1500-ca. 1582) is the author of the Shidetang edition of Journey to the West, this position is supported only by the lack of better candidates and more convincing evidence. Furthermore, the origin of the Monkey King character remains unclear.”

-“Through hundreds of years the Monkey King figure has shown amazing adaptability. His story appears in various forms in all media, crossing borders of culture and time, and his image has been frequently used in racial and political representations with social and political impact. Sun Wukong’s changes throughout modern history, intertwined with the construction and representation of Chinese identity, require a thorough examination.”

9: “Tracing further back from “Journey to the West,” two major sources for the narrative have been found: the historical journey of Xuanzang and the mythical figure of the Monkey King. Although the historical event clearly refers to the journey to India that the monk Xuanzang undertook in the seventh century, and the historical figure Xuanzang is accepted almost unanimously by scholars as the source of the character Tripitaka in the novel, the source of the Monkey King is unclear. Multiple figures may have influenced the image of the Monkey King, including Hanuman in the Indian tradition and monkey lore in the Chinese tradition. Each of these two major narrative lines revolves around one protagonist, who together become the two major characters in Journey to the West. Although the Monkey King figure was adopted into the narrative of the journey to India as only a helper of the monk, in later versions of the story the monkey becomes the protagonist, as becomes evident in Journey to the West, and more obviously in contemporary adaptations in China, where the Monkey King becomes the central figure with whom the audience identifies, and Tripitaka is portrayed with more negative features.”

11: “If one were to narrow the rich meaning of the Monkey King image down to a trope, it would like in the tension between the monkey, the human, and the god that coexists in the Monkey King. Because the tension exists in something as important and personal as the body itself, the image of Sun Wukong is therefore being used in a varied situations representing the struggle in identity. What the Monkey King can contribute to the issue of Asian American identity is the metaphor of transformation, the freedom one can attain in one’s body, and by extension in aspects of one’s social life.”

13: “Because of the fundamental multivalence in this figure, various political and ethnic groups use him as a representative to tell their own stories…Historically speaking, ‘Journey to the West’ is a product of adaptation. When the image of the Monkey King is added to the narrative and gradually takes the shape of Sun Wukong in Journey to the West, the influence of antecedents and the interlacing traditions of popular and elite culture together shape what we know as the protagonist of the sixteenth-century novel. A major transformation takes place in the mid-twentieth century during the reign of Mao Zedong, when the trickster monkey is collectively recast as a revolutionary hero. This heroic image remains the mainstream view until a new change is initiated by a Stephen Chow film, A Chinese Odyssey (1995), after which the image of Monkey takes a postsocialist turn. While the new transformation of the Monkey King as a hero is ongoing in China, in American popular media the Monkey image is adapted in a different manner, representing a mythical and antiprogressive oriental. Asian American adaptations, on the other hand, use the image of the Monkey King to illustrate the struggles of ethnic minorities in the United States, racial stereotypes, and ethnic identity. Monkey continues to shape-shift in new places and times, and each new Monkey collectively enriches our understanding of his image.”

15: “At the beginning of the hundred-chapter novel Journey to the West, a monkey is born from a primeval stone egg. This uncommon birth makes it impossible to place him into a distinct taxonomic category. ‘Born of the essences of Heaven and Earth,’ he is nonetheless still one of ‘the creatures from the world below.’ While the Monkey King belongs to both heaven and earth, his legendary birthplace is not easily locatable in either. According to the Buddhist cosmology introduced to the reader at the beginning of the first chapter, the Flower-Fruit Mountain (Huaguo Shan) appears to be located on the East Purvavideha Continent (Dong Shengshen Zhou), one of the four continents of the world. However, its geographic location relative to heaven and earth, or to the other continents that the monkey traverses in his journey, is never accounted for. To some extent the ambiguous birth and birthplace of the monkey contribute to his multivalent character.

At home on the Flower-Fruit MMountain, the monkey soon declares himself the Monkey King after demonstrating his prowess by crossing a waterfall and discovering a new territory, the Water-Curtain Cave, on behalf of the entire monkey kingdom. It is the first breakthrough in his life and is accomplished through crossing boundaries. Soon thereafter, and having become dissatisfied with a mortality that, by necessity, would subject him to the border between life and death, the self-proclaimed king sets off on a raft in search of a teacher who might guide him toward immortality. This journey brings him from the East Purvavideha Continent to the West Aparagodaniya Continent (Xi Niuhe Zhou), where he finds a master in the Patriarch Subhuti (Xuputi Zushi) on Lingtai Mountain.”

16: “Of no small significance, the master, one of the ten disciples of the Buddha, is described here as one who finds harmony among Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism. By means of the physical and spiritual journey from east to west, the monkey has acquired a name, Sun Wukong (Awaking to Emptiness), together with esoteric techniques enabling him to wield magical powers.

After returning to the Flower-Fruit Mountain, Sun Wukong successfully defends the subjects of his monkey kingdom by defeating a demon foe and thereby creating a name for himself among the demon kings. In addition, he befriends a number of immortal beings who occupy neighboring lands, one of whom in the Bull Demon King (Niumo Wang), who later becomes an antagonist of the pilgrims. By becoming brothers with these demons on earth, Sun Wukong posits himself as one of them. He tests his power in the water realms and convinces the dragon kings there to present him with their treasured magic iron, which becomes hi famous iron rod. He also creatures turmoil in hell when he deletes the names of his monkey tribe from the Register of Life and Death, hence attaining immortality, although unofficially. The sphere in which he can be active is thus enlarged to include the earth, the sea, and the underworld.

Heaven, having learned of the monkey’s mischievous behavior, appoints him as Supervisor of the Imperial Stables (Bimawen), in an effort to co-opt him. His territory is thus further enlarged to include heaven. This is an important step in his life since he is now recognized as a deity within the heavenly hierarchical system rather than an outsider demon. When Sun Wukong recognizes his low position in the celestial hierarchy, he returns to his mountain and lays claim to the title ‘Great Sage, Equal to Heaven,’ essentially declaring himself the strongest demon in the world in possession of an outlaw power on par with heaven’s. Dissatisfied with marginalization within one system, he simply chooses to create a parallel system and names himself its head. And when heaven is unable to take him by force, it once again must reabsorb the monkey peacefully by reaccepting him into the heavenly fold. Despite being officially recognized as the Great Sage, the Monkey King still constantly breaks rules in heaven, and ultimately creates havoc when he learns he is not invited to the Peach Banquet. The disgruntled monkey breaks off yet again from heaven, this time demanding that he replace the Jade Emperor…”

17 + 18 (for list): “…himself. Significantly, the domains that Sun Wukong has so far tested and conquered include the earth, water, hell, and the Taoist heaven. Being active in all levels of the mythic cosmos enables him to enjoy immense growth in his realm—but more importantly, he becomes effectively limitless.”

Sun Wukong’s rebellion comes to an end when he meets the Buddha. He accepts the wager the Buddha has proposed, which is to jump out from the Buddha’s palm. Failing to do so, since the Buddha’s palm can grow as fast as Wukong can jump, he is subsequently imprisoned under the Five Phases Mountain for five hundred years, which functions as a turning point in Monkey’s life and an intermission in the narrative. What Monkey goes through during this period is completely omitted by the narrative, which simply switches to the story of Tripitaka and the beginning of the journey. When the Monkey King reappears in the story, his life starts anew on a very different track.

The monkey is in due course released by the traveling monk Tripitaka, who becomes his master and gives him the name Pilgrim (Xingzhe). At the beginning the master is shocked by Wukong’s demonic behavior and worried that the monkey might be out of control. The Bodhisattva Guanyin responds by setting a fillet on the monkey’s head. The tightening of this band—in response to Tripitaka’s recitation of the Tight-Fillet Spell (Jingu Zhou)—enables Tripitaka to control the monkey’s actions. Henceforth Sun Wukong serves as Tripitaka’s protector and as leader of the other disciples. He becomes the monk’s most reliable defense against demons and monsters on their way to the West. In the following eighty-seven chapters, which are primarily a long series of captures and releases of the pilgrims by monsters, demons, animal spirits, and gods in disguise, Sun Wukong either defeats the adversaries himself or finds a natural or sociopolitical conqueror of the enemy to ensure victory.

In Journey to the West, Monkey’s life can be summarized as composed of two parts, with the Five Phases Mountain as the watershed. Before his subjugation by the Buddha under the Five Phases Mountain, his life can also be divided into several phases, each phase with a different name and identity:

I: Before Subjugation:

a. The nameless stone monkey

b. The Handsome Monkey King (Mei Houwang)

c. Sun Wukong (name given by Subhuti)

d. The Supervisor of the Imperial Stables (Bimawen)

e. The Great Sage, Equal to Heaven (Qitian Dasheng)

Intermission: 500 years under the Five Phases Mountain

II: After Subjugation

Pilgrim (Xingzhe)

18: “The five phases of the monkey’s life before his subjugation by the Buddha demonstrate the innate drive of the monkey to test every limit that defines his sphere. With each step the monkey takes in his life, there is a transformation, a breakthrough, and his magic skills allow him to transgress limits. Step by step he broadens his sphere, challenging every authority, until he is facing the greatest cosmic power (who is, interestingly, the foreign Buddha from the West, invited by the indigenous god, the Jade Emperor). It is the spirit that challenges all limits that identifies him as a demon, one of those who dwell outside of the space of heavenly order. Since hierarchical control is about keeping boundaries and maintaining order, this kind of nonstop challenge cannot be accepted. Monkey therefore has to be either considered as a challenge from the outside (a demon) or changed and co-opted within the system.”

--“The five hundred years serve as a narrative gutter, before which Monkey strives to surpass all boundaries—the patriarch of all beings—while after it the monkey becomes a servant, a pilgrim following the orders of a monk, confined by the magic headband. Before the gutter, he was a demon himself; after the gutter, he becomes a demon-subjugator and a demon killer. When encountering and fighting antagonist demons, the pilgrim monkey continually boasts to them about his glorious past as a demon monkey but the kills or subjugates them by himself or with celestial help. In this sense, the journey of the pilgrims is at the same time a story of demon-conquering and an account of the subjugation of the monkey himself.”

19: “He is simultaneously the one and the other, dual contradictions within one body.

But this is not only a journey from China to India. The Monkey King’s journey, far from unidirectional, is also full of upward and downward movement—he bounces between the heavenly gods and the demons and monsters on earth both before and after his submission. The nature of these trips does, however, change after his imprisonment. In the early phases of his life, the journeys up and down are carried out via his free will, whereas the later ups and downs as a pilgrim are mostly arranged by Guanyin and the other gods, as part of the trials of the journey. Just as his somersault never enables him to jump out of the hand of Buddha, his somersaulting up and down during the pilgrimage never gets him out of the determined trajectory of his life. He is only fulfilling his task, the mission of a pilgrim who works as a mediator.

The character of the Monkey King is fundamentally self-contradictory. In the earlier stage of his life, his is a self-important heroic rebel, but later he transforms into a loyal disciple of the monk master and a pious believer in Buddhist thought. Monkey does go through some transitional periods during the journey, including a few incidents in which he is in disagreement with, yet has to obey, Tripitaka, but later in the journey the narrative demonstrates that his understanding of the Heart Sutra often even surpasses that of Tripitaka.”

20: “Reflected by his names and titles, Sun Wukong juggles his multiple identities, some of which are sharply opposed to each other.”

21: “Rather than mediating between two opposite states, the Monkey King denies and deletes dualism and brings multiple and otherwise incompatible possibilities together.”

24: “As a narrative rejecting dichotomy, Journey to the West clearly rejects a simple division of the story into shouxin (controlling the mind, retrieving of mind) and fangxin (letting the mind go, exile of the mind). Not only is the ‘mind monkey’ always fond of his mischievous ways when he remains a follower of Tripitaka, in the two episodes of the ‘exile’ of the ‘mind monkey,’ he is never totally let loose either. In both cases he asks Tripitaka or Bodhisattva to take his head fillet off, but neither of them is able to fulfill his request. Ironically, although Tripitaka ‘exiles’ the monkey from the pilgrim group, his power over the Tightening Fillet remains. Monkey, on the other hand, is also never totally happy when being released. In the case of the first release, Bajie (Pigsy) has to resort to a stratagem to persuade the monkey to return: he lies to the monkey that the monster who had beaten the pilgrims does not take seriously of the name of Sun Wukong and his deeds in heaven five hundred years ago. It is in defense of his reputation as the ‘number one monster’ that the monkey leaves his Flower-Fruit Mountain and returns to rejoin the band of pilgrims.

In the case of the second ‘exile,’ the episode of the ‘double-mind monkey’ (erxin yuan), a fake Wukong commits a series of monstrous crimes in his name. While one ‘mind monkey’ is staking with the Bodhisattva, the other ‘mind monkey’ goes to strike the master Tripitaka unconscious, takes his travel documents, returns to the Flower-Fruit Mountain, and sets up another pilgrim band, ready for his own journey to the West. The resemblance of the two ‘mind monkeys’ deceives everyone except the Buddha, who sees through the fake Wukong and recognizes him as a six-eared macaque (liuer mihou). The use of a double of Wukong enables the narrative to literally grant the monkey the facility to be self-contradictory, with one Monkey being a pious follower of Tripitaka, and the other a monster who is even capable of beating his master. At the culmination of this episode, Sun Wukong uses his rod to kill the six-eared macaque,…”

25: “…despite the fact that the macaque had already been captured by Buddha’s golden almsbowl—a constraining weapon—and submitted to Buddha’s control, which seems out of character for the ‘good’ Monkey. One feasible explanation would be that it is an action of eliminating the monster in him, indicating that he is getting closer to achieving Buddhahood at this point in the journey. However, this explanation does not negate another one: that he kills the six-eared macaque because the latter has copied him too closely, the best demon among the ones that Monkey has conquered. By killing his rival who resembles himself, he plays the norm of self-contradiction to an extreme.”

26: “At that very moment the actual smallness of the monkey’s bloated self is demonstrated in the shadow of the Buddha’s fingers, the overblown ‘mind monkey’ is reduced to finite proportions, and his rehabilitative imprisonment under Five Phases Mountain begins. The lesson demonstrates to him that, however far the ‘cloud-somersault’ can reach, it would also represent his own unbreakable boundary. The Buddha’s fingers serve as an index, revealing to the monkey that what beats him is how own self. Later this indexing role of Buddha’s hand is taken over by the Five Phases Mountain, and after that the headband. Whenever Tripitaka recites the spell, Monkey is reminded of his own limits and the impossibility of breaking them, even with his rod.

In the case of the six-eared macaque, one can reach an opposite explanation as to why Wukong chooses to kill him: to free himself. Just as in the submission of Wukong, Buddha beats the six-eared macaque at his forte. Although the fake Wukong is strong in taking forms of others and had succeeded in confusing everyone else, the Buddha is able to exactly identify this monkey’s original form: someone belonging to none of the ten categories in the universe, neither the five immortals (wu xian) nor the five creatures (wu chong). There are four kinds of monkeys who ‘are not classified in the ten species, nor are the contained in the names between Heaven and Earth,’ among which was the first, ‘the intelligent stone monkey (lingming shihou), who knows transformations, recognizes the seasons, discerns the advantages of earth, and is able to alter the course of planets and stars,’ and the fourth, ‘the six-eared macaque, who has a sensitive ear, discernment of fundamental principles, knowledge of past and future, and comprehension of all things.’ This recognition announces the six-eared macaque’s failure as one who has been trying to use his disguise to erase the boundary of his self while taking up the identity of Wukong. It also announces once again the failure of Wukong, who although not belonging to any of the ten species between heaven and earth, still falls into one of the in-between types that the Buddha names: the intelligent stone monkey, indeed a peer of the six-eared macaque. Therefore by killing the six-eared macaque, Wukong not only kills a monster who has tried to cross proper borders, but he also kills a self whose boundary has just been pinned down. This action of self-annihilation is in this sense an effort in defiance of any classification.”

27: “Readers may often find it hard to tell whether the monkey is a monster or a pilgrim during any one incident: just like the rod and headband, the monster and pilgrim are indispensable sides of the character of Sun Wukong.”

-“The narrative of Journey to the West itself also has a multivalent nature. Containing and allowing for contradictions is a central message of the book. Theses and rhetoric of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism all appear in every part of the work. For a story of Buddhist monks’ pilgrimage for Buddhist sutras, it also bears apparent characteristics of Taoist dual cultivation. While gods of Buddhist and Taoist traditions happily coexist, a Confucian emphasis on filial piety and loyalty is also prevalent. Owing to the coexistence of heterogenous factors, the text gives space for various interpretations of the metaphorical meaning of the book…In the narrative there are multiple parameters for the classification and ranking of cosmic beings, among them two basic categories—the earthly demons and the heavenly gods. At first glance the two are a pair of opposing powers, one always contradicting the other. However, a closer view of the relationship between the two reveals that the boundaries between the categories and kinds in the cosmic hierarchy are not firmly fixed. There are always possibilities of crossing the boundaries; the coexistence of all these distinctive beings is already an act of the abnegation of boundaries.”

28: “Historian of Chinese religion Robert Campany visualizes the positions of these demons in the hierarchy, within which boundaries can be crossed upward or downward by means of transformation (hua, the phenomenon of demons assuming bodies and forms not their own), reincarnation, cultivation, conversion, or subjugation. Hierarchical distinctions are thus relative, and typological divisions appear to be mere illusion, with the pilgrim and demons both functioning as antagonists and complementing one another. Although demons and the pilgrims are similar in that both strive for cultivation of self, ‘demons have not yet realized the necessity of submitting the self to a larger Self that is the entire cosmic order.’ This insight points to another duality that is undercut by the narrative.

This allegorical explanation—that the pilgrims, by battling against the demons, come to realize the truth of emptiness, while Wukong, as indicated by his name, has always been aware of it—however, is too neat, as the purpose of the journey allows to multiple interpretations. While the pilgrims are moving toward a destination, ironic tension is apparent between the exuberant ease with which Monkey travels between different sphere and Tripitaka’s extreme difficulty in moving forward on his journey on earth.”

29: Andrew Plaks argues that “the characteristic Chinese solution to the problem of duality ‘consists in the conception of a universe with neither beginning nor end, neither eschatological nor teleological purpose, within which all of the conceivable opposites of sensory and intellectual experience are contained, such that the poles of duality emerge as complementary within the intelligibility of the whole.’ This argument about the Chinese concept of complementary duality provides an interesting explanation for the coexistence of contradictions in the narrative. It may also count as one of the cultural situation ‘generative of ambivalence and contradiction’ that folklorist Laura Makarius discusses. The concept of complementary duality in Chinese culture certainly helps explain the fundamental ambiguity regarding the teachings in the journey, the most famous being the merging boundary between god and demon.”

-“Transformation is something practiced very commonly by heavenly immortals and demons alike in Journey to the West. Besides crossing the boundary between the deity and demon, it also illustrates that all ‘forms,’ no matter how different they might look, are the same because they are all manifestations, or illusions. Forms are not the true nature of a being, and an important technique for a creature to attain in becoming an immortal through cultivation is the ability to transform itself, as well as the ability to see through forms. The Monkey King is among the most adept at seeing through the false forms of demons and monsters. In short, transformation, and the understanding of transformation, seem to have a crucial connection with a nondualist (or multivalent) understanding of the universe.”

35: “The multistable image of the Monkey King…serves as a hyper-icon. The seemingly simple factors of the image, a monkey in human clothes with a head ring and an iron rod, together encapsulate a whole bundle of meanings, an entire episteme. It can be used as a decoration, and it can also be used to speak to power, knowledge, and representation. It is fascinating that it continues over centuries to appeal to readers/audiences of various social orders and successfully transforms them into creators of new images.”

39: “Shihua [Full title Da Tang Sanzang qujing shihua] is the first fictional account of Xuanzang’s journey in which the monk acquires a monkey attendant who functions as his guide and protector. Following his introduction, the monkey figures enjoyed growing popularity in subsequent fictional retellings of the story, until in the hundred-chapter novel Journey to the West he becomes the protagonist of the story, overshadowing his master…Compared to Xuanzang’s historical journey, Shihua introduces two major changes to the nature of the journey that are carried through later adaptations of the story. In the first, the monk’s individual religious pursuit, a brave act that breaches the law of Tang and puts his own life at risk, is transformed into the performance of a decreed commission from the Tang emperor. Although the imperial decree seems to have given Tripitaka a more celebrated status, his choice to defy the legal order in order to undertake his religious pilgrimage is taken away from the monk. Second, realistic challenges the monk had to face are replaced by obstacles deployed by demons and deities, which Tripitaka relies on the monkey to conquer. These two changes set the stage for a transformation of the story about Tripitaka into a story about the monkey.

Buddhist themes and elements in the story are obvious, but there is no monopoly of Buddhist themes; instead, a variety of traditions and cults are present in the text, with popular tradition being blended into the orthodox religious material. In this sense, Shihua already begins to show what is masterfully realized in the hundred-chapter version Journey to the West: the encyclopedic coexistence of different and conflicting cultures and traditions. According to Shihua’s account, the monk is on his way to acquire scriptures because he has received an imperial commission. On his way he meets the monkey figure, Hou Xingzhe (Monkey Acolyte), who becomes his guide and assistant. This story is filled with praises of the religious pilgrimage, paying its respects to Buddha and Buddhist teaching and eulogizing the peaceful places near the Western Heaven. Unlike the later versions, it is clear in the story that the success of the pilgrimage is based on Tripitaka’s deep understanding of Buddhist texts and great strength in his belief. The Tripitaka in later versions will reply on the assistance of Sun Wukong and gods from all parts of the universe to complete his journey.”

40: “There is little evidence to show where the monkey figure originated, but scholars have discussed the possible connections between Hou Xingzhe and the carved monkey figures at the Kaiyuan Temple in Quanzhou Prefecture, Fujian; monkey stories in Buddhist texts; and Hanuman of the Ramayana. Discussion about Hanuman as the influence or origin of Sun Wukong can be traced to Hu Shih’s 1923 article ‘Textual Criticism of Journey to the West’ (Xiyou ji kaozheng), but at about the same time Lu Xun, in his Brief History of the Chinese Novel (Zhongguo xiaoshuo shilue), disagreed, connecting Sun Wukong with the ape-shaped Chinese mythical figure Wuzhiqi. The two scholars who built the foundation of modern Chinese literary study thus began a long-running argument in Journey to the West scholarship about the origination of Sun Wukong. Even today, the problem of the origin of the Chinese Monkey King is unresolved. For, in addition to these two sources, there are other possible origins or influences, such as the influence of Buddhist texts; the figure of Shi Pantuo, a disciple of Xuanzang at the beginning stages of his trip; the Monk Wukong of the Tang; tales about a white ape who abducts women; and the Fujian cult of Qitian Dasheng or Tongtian Dasheng….Regarding the origination of Hou Xingzhe, Zhang Chengjian’s findings generally support the notion of a greater influence from India than from indigenous myths, and in particular the influence of Hanuman or the ape-shaped guardian general in the Tantric tradition.”

41: However, “scholars who support this view have not been able to provide a convincing theory about the paths of transmission of the Hanuman story. It would seem that the Ramayana may have been transmitted to and spread in China via the Silk Road, the marine Silk Road, or the path via Schuan and Yunnan; however, these paths do not correspond with the appearance of Hou Zingzhe and the transmission of Hanuman to China in either time or place…a foruth path for the transmission of Hanuman could be the Musk Road via Tibet, , as the Tantric tradition reflected in Shihua and the spread of Tantric Buddhism at the time from India through Tibet to China demonstrates a connection between Hanuman and Hou Zingzhe. It is worth noting here, though, that the necessary link between the transmission of Tantric Buddhism and the story of Hanuman is yet to be found. Nonetheless, the image of Hou Xingzhe in Shihua reminds us more of Hanuman and the images of the monkey protector figures found in mural paintings in Dunhuang and the stone relief in Kaiyuan Temple—these serious and godlike images bear very little resemblance to the trickster that the monkey would become in later version.

The role that Hou Xingzhe plays is Tripitaka’s guide through the journey. Although Xingzhe calls Tripitaka ‘my master’ (wo shi), he is the one who gives advice, and Tripitaka always follows it.”

44: “…although Hou Xingzhe appears as a clearly synthesized figure in Shihua, bearing influences from both Indian and Chinese cultures, he is mostly an honorable and capable godlike figure. Negative features have yet to be developed in this character.”

-The six-part, twenty-four-act Zaju Xiyou ji is attributed to the fourteenth-century playwright Yang Jingxian, who lived during the late Yuan and early Ming periods. In the few hundred years between Shihua and Zaju, the story of ‘Journey to the West’ is not only more expanded, containing many of the stories that can be found later in Journey to the West, but the monkey figure in Zaju has grown into a character strikingly different from Hou Xingzhe. If Hou Xingzhe in Shihua is depicted as an advisor for Tripitaka, as respectable albeit mysterious deity, and a brave fighter, the monkey in Zaju is pictured as a rowdy clown, an untamed demon and ill-qualified Buddhist disciple.

The monkey’s name in Zaju now is almost the same as in the sixteenth-century fiction Journey to the West. He refers to himself as ‘Tongtian Dasheng’ (Great Sage Reaching Heaven), only one word’s difference from ‘Qitian Dasheng,’ the title Sun Wukong receives from the Taoist heaven in the sixteenth-century book. In some versions of the Monkey King story, including the Zaju, Qitian Dasheng and Tongtian Dasheng are brothers…”

45: “Although Tongtian Dasheng is the monkey’s title, in the drama everyone calls him ‘the monkey’ (husun), including Guanyin, even though she is the person who gave him the names Sun Wukong and Sun Xingzhe (Acolyte). When Guanyin presents Sun Xingzhe to Tripitaka as his disciple, she gives the monkey an iron fillet, a cassock, and a knife….Even with the headband’s control, Tongtian Dasheng’s behavior and language indicate that his mind remains that of an irreverent demon.

As in the zaju theater tradition, Sun Xingzhe introduces himself to the audience with a poem at his first appearance. Vaunting his celestial birth, his power, and the troubles he could create, in colloquial expression rather than elegant traditional terms as others’ opening poems, the monkey’s poem describes himself as a celebrated ape demon, referring to himself as the King of a Hundred Thousand Demons. In the following statement he introduces himself and his four siblings as his demon family: His elder brother Quitian Dasheng, a younger brother Shuashua Sanlang, and two sisters, Lishan Laomu and Wu Zhiqi Shengmu. This genealogy of the monkey shows that Sun Xingzhe in Zaju is already much more localized, settled into the local religious/cult culture. Unlike the monkey in other versions, this one has a wife, the abducted princess of the Country off the Golden Cauldron. He also proudly reports to the audience his famous misdeeds, which is also the reason that heaven is after him: he has stolen the Jade Emperor’s celestial wine, Laozi’s golden elixir, and the Queen of the West’s (Xichi Wangmu) peaches and fairy clothes. He also makes upfront ribald references about himself in this very first speech. The monkey’s demonic heart is indicated by his intention to eat Tripitaka immediately after Tripitaka rescues him from beneath the mountain. He never shows any seriousness about his business of pilgrimage, and his behavior does not improve during the journey. When the team arrives in India, he uses crude language in a conversation with an old lady about Buddhis ideas of the ‘heart.’”

46: “Sun Xingzhe does not act seriously, nor does he ever speak seriously. The king of demons seems to be good only at stealing and running away.”

-“In scenes 13-16, in the episode of Tripitaka and Sun Xingzhe’s encounter with Zhu Bajie the pig demon, who is converted into Tripitaka’s second disciple, Xingzhe offers to help fight the pig demon, but he is more interested in the Pei girl (old man Pei’s daughter) who has been abducted by Zhu. He only offers to help after old Pei tells him that his daughter is a rare beauty, and his dealings with the pig only revolve around the girl: when he visits the pig’s mountain home, he sees only the Pei girl, so his first action is to take the girl back to Pei. He then waits fo Zhu Bajie in the bridal chamber in the Pei girl’s clothing and flirts with the pig when he arrives…His sustained interest in woman and sex is demonstrated in another encounter with a demon in the Flaming Mountain episode. In this story, he seeks to borrow the Iron Fan from Princess Iron Fan (Tieshan Gongzhu) to put out the fire,…”

47: “…but because he introduces himself using vulgar language, the princess refuses to lend him the fan and instead attacks him. Although eventually—with the help of Guanyin and other gods—the pilgrims pass the Flaming Mountains, the battle with Princess Iron Fain, which later becomes one of the most famous battles of Journey to the West, seems to be caused solely by Sun Xingzhe’s insolence.”

-“The vulgarity of Sun Xingzhe’s language persists throughout the drama. The zaju drama during the Yuan era is distinguished from most other earlier Chinese art forms by its use of informal, vernacual, and nonsensical language. The language that Xingzhe uses is the most vulgar of all, corresponding to his role as the clown. He amuses by making crude jokes and obscene references at most inappropriate occasions throughout the story. For instance, at a crucial moment of his life when Tripitaka meets him for the first time and tries to climb the mountain to have him released, the monkey starts a conversation about love and explains that Triitaka’s motivation to save him is his lust for the monkey’s thin waistline, which resembles that of a desirable beauty. The monkey makes a reference to Agilawood Pavilion (Chenxiang Ting), a place that is known through Li Bo’s poems about the love affair between Emperor Tang Xuanzong and his consort Yang Guifei.”

-“When asked about his heart, Xingzhe comments that he used to have a heart, but he ‘shit it out’ because his ‘asshole’ is too wide.”

48: “From Shihua to Zaju, the monkey is transformed from a god who acts properly to a demon who uses foul language and makes suggestive jokes. In the hundred-chapter Journey to the West, Sun Wukong is turned into a multivalent figure, funny but not crude. The vulgarity of Sun Wukong seems to be peculiar to the Zaju version.”

53: “If Hou Xingzhe is in general a god with positive qualities, Sun Xingzhe in Zaju shows the negative parts of his character coming into full bloom. He is much more associated with a buffoon and a demonic ape than with a celestial god. From Hou Xingzhe to Sun Xingzhe, the monkey figure is more localized, closely bound with popular culture. If we indeed can consider him as a figure on the way toward his Buddhist belief, he also remains the Taoist demon he claims to be and demonstrates his concern with keeping the order of Confucian values, as reflected in the Zhu Bajie sequence. Significantly, the monkey in Zaju receives the iron fillet from Guanyin, a device to control the demon in him, and which comes into use in the episode of the Land of Women. It is not until the hundred-chapter Journey to the West that the monkey also obtains his powerful weapon, the Golden-Hooped Rod, and hence completes the image of Sun Wukong that will become the most enduring version.”

-“When Wu Cheng’en performs his creative adaptation, the sources of the journey story have been quite fully fledged. For instance, the Pak t’ongsa onhae (Pak tongshi yanjie), a Korean reader in colloquial Chinese first printed in the mid-fifteenth century, contains a list of references to mythic places and demons and gods, and brief accounts of episodes such as Sun Wukong’s rebellion against heaven (chapters 5-7, 13 in the novel), and Tripitaka and Sun Wukong’s experience in…”

54: “…the Cart-Slow Kingdom (chapters 44-46 in the novel). One of the dialogues in this record presents a picture of ‘ordinary people going out to buy popular stories in book form,’ and Journey to the West is one of them. In the dialogue, a question arises about why people would buy popular tales instead of the Four Books or Six Classics, and the given answer is, ‘The Journey to the West is lively. It is good reading when you are feeling gloomy.’ This conversation shows that some version of Journey to the West is already circulating at the time and that for an ordinary reader this kind of popular story is preferable to Confucian classics. Wu Cheng’en’s taks is to pull together the source materials that are available for him and transform them into a fuller text, one that is reprinted, commented upon, and continued by a large number of writers who are scholars like him. Many of these later ‘adaptations’ take the story as a serious allegories of religious teachings, instead of assuming it is just for entertainment. Wu Cheng’en’s adaptation of the ‘Journey to the West’ story has accomplished its transformation from a popular-culture to an elite-culture work.

Compared to Zaju, Journey to the West has grown a great deal over time, both in terms of adding new episodes and through addition to the original narrative. It is the largest amalgamation of the pilgrimage sources, retold in a balanced style. Journey to the West brings the Buddhist and Taoist traditions into a new balance, despite the tensions that appear frequently in the story. Confucian principles such as the morals of loyalty and filial piety permeate the story, whether in the human world, the underworld, or the heavens. The peaceful coexistence of the three religions is pronounced repeatedly in the book and is also accepted as one of the major themes of the book by both scholars of the Ming and Quing eras and in contemporary analyses.”

-“Printed in the sixteenth century of the Ming period, a time when the printing industry grew rapidly through commercialization and many people could buy novels to read for pleasure, the concerns of this book should be different from those of earlier vernacular narratives. It is a transformational time for the writers, publishers, and readers: whereas the readership of the manuscript culture of the earliest vernacular narratives consisted of ‘circles of literati and admirers,’ for the print culture, the reading public was no longer restricted to the learned classes.”

55: “The idea of a general reader of the novel must have contributed to the writing. Interestingly, while earlier vernacular narratives are written to be copied and circulated among the literati, the new novels are written by the literati for a wider audience. Whatever other purposes the author might have, much attention must be paid to the readability of the book: that it tells a fun story, presents interesting characters, and uses language that is accessible and lively. During Pak t’ongsa onhae’s time, the book Journey to the West had been popular because of its liveliness, which provides a rationale for the printers’ interest in printing new adaptations, and both the publisher and the author must have made sure that these popular features would be included in order to ensure its continuing success in the market. The consideration of the reader and market thus supports the reading of the novel as a work for pleasure, an exemplary book of the low culture, even though it is written by a scholar.

In Journey to the West, Sun Wukong becomes a figure of more depth, someone who does not follow any prototype. He is still the guide and protector, resourceful for the journey, and knowledgeable about Buddhist teachings, but he is not the overly seriously Hou Xingzhe of Shihua. He is still funny and mischievous, creating trouble while pushing the narrative forward, but he is no longer the clown of Zaju. It seems that much of the vulgarity is redirected to the character of Zhu Bajie, which allows Sun Wukong to become a more introspective character who seeks to answer the question; Who am I?’ or, more accurately, engages the reader to ask the question.

Compared to the earlier versions, the most significant change of Journey to the West is the change of protagonist. In Zaju, Triitaka is still the main pilgrim on the journey and the main character in the entire play. Besides the incidents during the journey, the drama starts with Tripitaka’s legend and ends with Tripitaka’s accomplishment of the pilgrimage. In Journey to the West this structure is changed. The novel begins instead with a seven-chapter-long account of the monkey’s story, which is elaborated more than in any earlier account. It is here that Sun Wukong obtains his weapon, the Golden-Hooped Rod, which does not appear in the previous monkey stories.”

56: “His actions, from stealing peaches from heaven, to making advances toward Princess Iron Fan, are all actions of a mischievous demon that needs to be controlled by the fillet. In Journey to the West, Sun Wukong finds his rod, and his experience—from the learning of skills, the testing of territory, the freedom of doing what he wants, to the kind of fun he enjoys no matter what he does and where he is—seems to be associated with, or represented by, the rod. Indeed, the narrative particularly makes the point that the monkey is meant to be the owner of the rod. The narrative also notes in one episode that without the rod he is no longer the monkey. The pleasure and freedom that Sun Wukong enjoys with the rod, or the Compliant Golden-Hooped Rod (Ruyi Jingu Bang) is only to be met by the fillet from the Buddha, givne to him by Guanyin via the hands of Tripitaka. The fillet is not compliant to his will; instead, it controls him against his will. From the moment that Sun Wukong puts on the fillet, he is transformed from a free monkey—or a demon from the viewpoint of the Taoist and Buddhist deities—to a disciple of Tripitaka, a ‘compliant’ good pilgrim for the journey. In a sense, he becomes the ‘compliant rod’ for his master and Guanyin, since they can use the Tightening Fillet to force him to do what they want. However, the story is told mainly from the monkey’s point of view, as is established in the beginning chapters. Thus, the conflict between the rod of free will and the fillet that constrains the will becomes fundamental for the character Sun Wukong, providing the exigencies for his behavior. The narrative makes sure that the power of the fillet is exercised later, too, for instance in the episode where Sun Wukong fights against the White Bone Demon.

The conflict between the rod and fillet is also the conflict between a god and a demon. Sun Wukong represents both god and demon in one body. Unlike previous vernacular narratives where the monkey may have different titles, which are self-made titles that qualify him as a demon in the mythical hierarchy, in Journey to the West, Monkey is twice given official titles by the Jade Emperor: the Supervisor of the Imperial Stables (Bimawen) and Great Sage, Equal to Heaven (Qitian Dasheng). The reason that he creates the trouble in heaven is because he sees the contradiction between his two identities: the god and the monkey, in contrast to Sun Xingzhe in Zaju, who steals because he wants to enjoy the treasures at his demon home with his wife. Sun Wukong of Journey to the West wants to be treated as a Great Sage, but unfortunately when he is seen as a monkey, he cannot possibly be…”

57: “…treated like the other gods. When his rod is reaching so far that he creates turmoil in the Jade Emperor’s palace and even wants to create a new order, it is time for the fillet to let him know the boundary of his power.

The conflict of the rod and fillet provides a kind of interior conflict that resonates with reader who must balance freedom and responsibility in their own lives. This conflict earns readers’ sympathy for the monkey figure and possibly contributes to their identification with him…Journey to the West provides ‘liveliness’ of writing, encyclopedic content, and most importantly, it focuses on the monkey’s identity quest. Therefore, besides the lively incidents between the pilgrims and demons, it provides above all a story of a monkey who seeks to understand who he is and his position in the world, a monkey who refuses to accept his limits but in the end has to accept the tragic solution of his life—all of which can be wrapped in the contradictory bundle of the rod and the fillet. In other words, Wu Cheng’en’s work establishes the protagonist as a ‘self’ that can be identified by the reader. This concern with the self and the communication between the writer and the reader begins with the addition of the monkey’s story at the outset of the novel.

My discussion of the inward interest of the Monkey King image corresponds with the trend of the ‘inward turn’ in the Ming cultural milieu. This trend is manifested by the interest in the mind/heart (xin) by the three religions in the Ming and culminates in the xinxue (learning of the mind/heart).”

58: “Yu’s reading of Monkey as the heart/mind of the pilgrim team also relies heavily on the Neo-Confucian understanding of the mind. In fact, the term xinyuan (mind monkey) is generally accepted by analysis today as representing Sun Wukong’s crucial role for the journey.”

-Journey to the West becomes an example of how popular culture and elite culture merge in a literary vehicle. Having been rewritten within ‘low’ culture, the story is taken over by an elite scholar and made into a classic, a work that is recognized by elite literati and exceptionally well written. The novel has established itself as the ‘original’ for future adaptation, both by elite scholars and by popular culture. In late Ming and Qing periods, there appeared sequels (xushu) to Journey to the West, in which the journey either continues or episodes are added in the middle. According to literary scholar Qiancheng Li, these sequels demonstrate an increasingly ‘inward turn,’ in which the journey is internalized.”

60: “The contemporary images of Sun Wukong have been so overwhelmingly positive that to me—and to millions of other Chinese readers—the Monkey King is a hero, a role model, and one who is not only fearless and willing to challenge authorities but also loyal to his master Tripitaka and devoted to the goal of the band of pilgrims. Although he had been a trickster figure who embodied contradictory values as portrayed in Journey to the West, or a monkey who made funny moves and demonstrated opera skills in the late Qing dynasty, the Monkey King in the new China epitomizes positive and progressive values for the proletarian revolution and socialist construction.

The early twentieth century was a time of turmoil in Chinese history, particularly the years between the 1930s and 1950s. This period was marked by the Japanese invasion, and occupation of China (1931-45), the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45), and the Chinese Civil War (1945-48). During the transformation Communist Revolution, with 1949 as the watershed year, the connection of the Monkey King image with the idea of revolution was established.”

61: “The reshaping of the Monkey King image is so powerful that it changed the position of Sun Wukong in literary tradition and made him one of the most popular literary and cultural figures for both old and young readers. Sun Wukong was transformed from a trickster, a figure whose role in the play is more for humor and stunts than serious conversation, to a sublime and honorable protagonist. This trajectory sheds light on the power of the political discourse of the state, which remodels images not only of historical figures but also of popular folkloric and mythical figures such as Sun Wukong.”

63: “The trend of portraying the Monkey King positively as a hero continues in Mao’s era. One episode that receives special attention and is crucial in the Monkey King’s transformation into a hero is Havoc in Heaven (Da’nao tiangong; or Nao tiangong), which first stands out as an important title in Peking Opera and is later adapted as a milestone animated feature film in China. All of the adaptations that take place after Mao’s rise to power are under the direct influence of his 1942 speech at the Yan’an Forum of Literature and Art.”

64: “Mao emphasizes that literature and art should serve both the people (including the worker, the farmer, the soldier, the working class, and the intellectual) and the purposes of the Revolution. The legacy of literature and art from the past should be inherited but only when it serves the revolutionary end of the people after necessary reform in both form and content.

To meet the end of ‘serving the people,’ the dominant form of literature and art in post-Revolution China is socialist realism, a form and genre that does not leave room for most classical works…[but] creating uproar in the celestial palace is a revolution and…Sun Wukong represents the class of the farmer rising up against the ruling class.

65: “The discussions about the nature of the opera accompany the transformation of the Monkey King onstage from a naughty troublemaker into a brave, rebellious, and heroic figure representing the revolutionary classes of the new China. The 1950s see a major revision of the ending of the ‘Havoc in Heaven’ story. The subjugation of Sun Wukong is replaced by his victory, and his reasons for creating the uproar (nao) in heaven are also rendered more justifiable.”

68: “In the setting of an unjust and oppressive heavenly court, Sun Wukong is transformed into a soldier who is full of hatred for oppression. Even the little monkeys in his kingdom are also presented as highly aware of the political importance of their battle…In this light, Sun Wukong’s battle with heaven becomes the battle between the monkey class and the celestial lords, thereby allowing the Monkey King’s victory in the end to belong to all monkeys. After battling with the generals and then breaking free from Laozi’s furnace, the Monkey King reunites at the Flower-Fruit Mountain with the little monkeys. The story here ends with the monkeys’ celebration of their victory over the heavenly troops, singing in ensemble: ‘Paean all over the Flower-Fruit Mountain! Paean all over the Flower-Fruit Mountain!’ Aside from creating a victorious Monkey King image instead of a monkey loser as portrayed in earlier versions in popular culture, this note also offers a finishing touch for the new image of the Monkey King as a revolutionary: the hero does not fight alone and for himself. He is the leader and a representative of the entire monkey class, representing the oppressed, and his battle is the battle between the mountain and heaven.”

69: “In contrast to the previous plays, which are about the subjugation of the Monkey King, this new play is a very loud celebration of the voice of the monkeys.

In transforming the mischievous into the righteous, Sun Wukong’s drunken misconduct is repackaged as conscious rebellion…stealing the pills becomes a righteous actions against the oppressive privilege that the Jade Emperor enjoys…This version of the Monkey King is not indulging in the hedonism of mischief—rather, he is portrayed as a fearless and angry fighter, a strong-willed crusader against evil.”

-“Both a welcomed witness and a most prominent passenger, the Monkey King travels like an emissary, representing Chinese art and Chinese culture.”

81: “Havoc in Heaven celebrates the established glory of the Monkey King as an indomitable rebel and invincible warrior. In [this] film the Monkey King does not seem to have any human faults. Reminding us of Weng’s Peking Opera version, even the actions of stealing celestial wine and elixir here are presented as acts of rebellion, not as mischief or mistake.

The most conspicuous revision aimed at the glorification of the Monkey King image appears again at the ending of the film. As with the Peking Opera script and Liang and Chen’s picture book, the animated film ends with Sun Wukong’s victory over the celestial court. But in this version, animation as the medium enables a more striking visual depiction of the Monkey King breaking Lingxiao Hall into pieces.”

85: “Havoc in Heaven has travelled to many other countries and has been well-received ever since the release of the first part in 1961. In Wan’s own words, it served as an unofficial diplomatic envoy through its screenings. The establishment of a Chinese style was so closely tied to the political task—representing the Chinese people for both the Chinese and the international audience…”

96: “In the novel Journey to the West, themes of the body and sexuality are sublimated due to the nature of the story as a religious allegory. Sex is a formidable sin from which all of the pilgrims except Zhu Bajie abstain. The only one who shows weakness toward the temptation of sex, Bajie is repeatedly tested, warned, and punished. In contrast, Tripitaka has sustained his pure virgin body for ten reincarnations, and it is believed that because of this his flesh has magic power: eating one piece of it is sufficient to grant the consumer longevity.”

97: “If Tripitaka has to constantly work against the idea of sexuality and make an effort to abstain from it, for the Monkey King sex has never been an issue. In his own words, he was born without xing. When Patriarch Subhuti asks him about his xing (surname), he took it as a question about his xing (temperament/nature) and responded that he did not have any temper (xing), and had never lost his temper (yisheng wu xing). This statement also holds true if we take the liberty of relating the pun of xing to sexuality. When it was clarified that the question was about the surname that he would have received from his parents, Monkey responded that he did not have any parents, since he was born from a piece of stone on top of the Flower-Fruit Mountain. Subhuti was much delighted upon hearing this, saying that the monkey was born of heaven and earth. Although the narrative of Journey to the West never explains the ways in which Monkey’s birth from stone function as an asset, it is clear that his parentless birth (a birth that is not as a result of sexual activity) distinguishes him as a model for religious practice. Quite relatively, throughout the journey sex simply never constitutes a temptation for him, as if his mind cannot fathom the idea of sexuality.”

The correspondence of the five members of the pilgrimage group with the Five Phases of Chinese philosophy is widely accepted, with Monkey related to Metal (Jin) and Heart/Mind (Xin). Metaphorically Monkey functions as the mind/heart of the group, who is focused on defeating demons and directing the group toward the religious holy land. This is probably why the narrative of Journey to the West constantly refers to Sun Wukong as the ‘heart monkey’ (xinyuan). If the heart/mind of the pilgrims should be directed toward attaining Buddhist sutras for the world or attaining Buddahood for themselves, the body that is attached to the worldly pleasures constitutes obstacles for the heart. For Zhu Bajie, the obstacle of body is significantly greater than it is for Tripitaka. But for Sun Wukong, his body does not stand in the way—born from stone and smelt in Laozi’s elixir furnace, his body is built for battles and transformational magic, not for the sin of desire.”

102: “In the sixteenth-century text, Sun Wukong himself goes through the identity transformation from a demon (a king of monkeys who occupy a mountain and claim it as their territory without recognition from authorities), to a deity recognized by the Taoist authority (first as the imperial horse keeper, then as the Great Sage, Equal to Heaven), and finally a Buddhis pilgrim who eventually attains Buddhahood. This upward transformation from an outlaw to a recognized deity was deliberately overlooked by the socialist adaptations, who downplayed the importance of social recognition either from the Taoist or the Buddhist order but only emphasized the idea of rebel and the metaphor of the journey. Hence the Monkey King was simply represented as a heroic rebel of oppression or a devoted follower of the path of socialist construction.”

103: “Joker’s plan eventually has to yield to divine intervention. Before his story reaches a happy ending, his life is taken by the spider demon, and subsequently his spirit faces Guanyin’s master plan: the Monkey King’s golden headband and golden rod are waiting for him. Although taking on the mantle of the Monkey King is presented as a matter of choice, there really is no alternative, and the film portrays this transformation as the saddest moment. Solemnly and ceremonially, Joker raises up and puts on the headband, repeating the lines he once insincerely spoke to Zixia: ‘Once there was a genuine love devoted to me, but I took it lightly. When I have lost it, I know it is too late to regret.’ It is as if he uses the last moment as Joker to redeem the lines that he performed badly before, but this time with complete sincerity. This sincerity in his last words about love proves the tragic nature of the unwilling transformation into Sun Wukong. Among all the Journey to the West adaptations, A Chinese Odyssey is probably the one that most emphasizes the tragedy of being the Monkey King.”

108: “The term ‘postsocialism’ was coined by historian Arif Dirlik before the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 and since then has been adopted by academics in various disciplines and has been defined in several ways…The postsocialist nature of the image of Sun Wukong is evident from the relationship between the people and the system. If a socialist system means people have faith in the socialist discourse, it becomes postsocialist when this faith is lost, even though ideological control from the leadership is still strong and is currently getting stronger. There exists a discord and discrepancy between the expectation from above and grassroots-level practice. Instead of the kind of collective identification with common ideals established in the socialist period, the postsocialist hero is interested in his individual agenda, which often includes focusing on his personal struggle to challenge the authorities that want to control him.”

-“major adaptations of Journey to the West almost always present the Monkey King as a postsocialist hero”

111: “The division and confrontation between demon (yao) and deity (shen) becomes a major driving force of the narrative of Story of Wukong. The journey to fetch sutras in Journey to the West is turned into a scheme by Buddha and Guanyin to deal with their uncontrollable agents, Tripitaka and Sun Wukong. This again is a predestined deal that leaves no opportunity for Monkey to win. Instead of following a chronological order, the narrative presents the two fiercest disorders that Monkey creates side by side: the havoc he creates in the sequence of ‘Havoc in Heaven’ and the chaos raised by the true and fake Monkey in the sequence of the battle between Sun Wukong and the six-eared macaque. In Journey to the West, the six-eared macaque is another capable monkey demon that has transformed into an image of Wukong. His masquerade is so real that no one except Buddha can tell the real from the fake. Story of Wukong presents the six-eared macaque as another Wukong, the part of Wukong that is ‘evil,’ to fight with the Wukong that is recognized as ‘good’ while controlled by Buddha’s headband. This means that Wukogn the rebel has to defeat the deities as well as himself in order to win. This conflict appears to guarantee the victory of Buddha: after Wukong kills the other half of himself, he is left no choice by to succumb to Buddha, who announces htat Wukong is actually the six-eared macaque and extends to him the opportunity to become his student once he accepts this identity. However, at this point Wukong has already recovered his memory of who he is. With his last breath, he declares war against Buddha and proclaims his real identity as the invincible Sun Wukong. His actions surprises Buddha himself, who admits that it is Wukong who has won—he has done something out of Buddha’s expectation and therefore has jumped out of Buddha’s control. In claiming his rebel identity, Wukong dies, but he also wins.”

112: “Both of the Wukongs in A Chinese Odyssey and Story of Wukong fit the model for a postsocialist hero: on the one hand, the ‘post’ of postsocialism is reflected in the spirit of rebellion, the lack of belief in authoritarian control, and the challenge to authority; on the other hand, the ‘socialist’ ideology and the government that represents it still maintains a strong presence. In contrast to the socialist revolutionary Monkey King produced during the 1950s and 1960s, who celebrates his victory in the end, both of the postsocialist Monkeys are doomed to lose.”

113: “…deals with the trouble of life the only way [Sun Wukong] knows: to endure until reality becomes history.”

114: “…the major contradiction of Journey to the West: why would Monkey, once a brilliant rebel, become a model Buddhis pilgrim? It is the ways in which the readers approach this contradiction that determines to a large extent their understanding of Journey to the West.”

115: “Monkey’s failure and dejection at the beginning and his ultimate transformation into a rebellious hero earns the audience’s sympathy, and their identification with him ensures interest in the project of such revision.”

116: “The 2015 animation film Monkey King: Hero Is Back (Dashen guilai, hereafter Hero is Back), directed by Tian Xiaopeng, was a success both at the box office and in critics’ review. Audiences were excited by the prospect of a quality animation film after a long stagnant period for Chinese animation, and they also liked the image of Sun Wukong created by the film. The film focuses on the moment when Monkey has just been released from the mountain after five hundred years of imprisonment. A dejected Monkey who cannot find his power throughout the film, he is irritated, instigated, and finally inspired by a little boy named Jiangliu (Tripitaka’s boyhood name), who believes in the greatness of the Great Sage he knows from legend. At the very last moment, Monkey rediscovers his magic power and defeats the demon Hundun. The short moment of Monkey regaining his magic in the end, lasting for only two minutes, wins the audience’s heart. Many popular reviews note Monkey’s repeatedly yelling throughout the film, ‘I can’t do it, I can’t do it,’ a frustration that aligns his character with normal human beings, in contrast to the radiant hero he finally becomes. The most popular review on douban.com states: ‘Every Chinese will fall in love with Sun Wukong. Each generation has its own Sun Wukong. I think this film can serve as a good first Monkey King film for children of the new century.’

Why does the audience respond to the Wukong in this 2015 film Hero is Back so positively…the Great Sage in Hero is Back…does not just accept. He searches, he questions, and he fights against his limits…Significantly, although the animated Hero Is Back is adapted from the sequence when Sun Wukong meets Tripitaka, it is not about how Monkey pledges allegiance to his Buddhist master. What it highlights is Wukong’s struggle against the seal from Buddha that still controls him, preventing him from using any magic power.”

-“…the ‘spirit of Wukong’ (Wukong jingshen): rebelliousness, variability, optimism, and persistence…”

118: “These few lines represent the major theme of the postsocialist Monkeys: engaging with this major conflict, Sun Wukong tries to use his rod to break free from the limitations of the headband. This is a clear contrast to the socialist Wukong: the revolutionary who is invincible, and the loyal party supporter who does not complain about the golden band. After all his failures and frustrations, the postsocialist Monkey in the end manages to find something the celebrate, a sense of accomplishment for himself, as Dai Quan indicated in his statement: ‘In the end, every monkey can become Sun Wukong.’ The monkey becomes Sun Wukong when he finds his lost ability to use his rod again.

New adaptations of Journey to the West in recent years thus share several common features. The first is a clear individualist bent, as Wukong invariably goes through a personal struggle, the solution for which lies in himself, not in any external agency. Second, Monkey is no longer the filial protector of Tripitaka or true follower of Guanyin’s teaching. The once-suppressed rebellions spirit is back. And third, although Monkey still has to submit to heavenly authority, he is allowed to think, to search, and even to challenge. His signature headband, which is transformed into a bracelet in both Hero is Back and ‘Wukong,’ reflects this change.”

142: “A few points in this part of Journey to the West should be underscored for the purpose of comparison. When the Monkey King declared his battle against heaven, his purpose was no less than attaining the highest seat in the heavenly empire. Although the heavens did not want to give the Monkey King real power, they had been quite generous when assigning him titles, first ‘Supervisor of Imperial Stables’ and then ‘the Great Sage, Equal to Heaven.’ Though demanding to be no less than the Jade Emperor himself, Sun Wukong also admitted, in good humor, that he was an ‘old monkey.’ In other words, he was at the same time the Great Sage and a monkey. Although the Great Sage is a self-proclaimed ‘hero,’ the style of his speech is humorous and lighthearted, which is in agreement with the style in which the whole story is narrated.”

143: “The human-versus-monkey division and confrontation is much sharper in that in Journey to the West, where Monkey’s dissatisfaction in heaven is based on his social status rather than his monkey identity itself. In the Chinese classic, the upheaval that he produces in heaven is more an unintended mistake than a purposeful action, all beginning from the mischievous theft of the celestial wine and food from the banquet and then of Laozi’s elixir when he was drunk. Waking up from his intoxication and realizing the severity of his mistakes, he returns to his Flower-Fruit Mountain but nevertheless continues his drinking party there with his guests, apparently planning to continue as Monkey King in style while giving up the position of ‘Great Sage.’”

145: “In chapter 7 of Journey to the West, two short paragraphs state matter-of-factly how the Buddha put the monkey under the mountain of his palm, and how he put up a sign with the mantra ‘Om mani padme hum’ on the mountain to secure the monkey’s imprisonment.”

149: “As with other ethnic groups in the United States, such as Irish immigrants, the Chinese image was simianized and demonized in propaganda cartoons, fiction, and other popular media.”

159: “When speaking of Orientalism, a study of the semiotics of stereotypes, Said argues that orientalism is ‘a form of radical realism,’ in that anyone who is employing orientalism talks about the objects in ways as if what they are speaking and thinking about is the truth. Relevant to Said’s discussion of stereotypes, Bhabha observes that colonial discourse ‘employs a system of representation, a regime of truth, that is structurally similar to realism.”

160: “Although many aspects of society have gone through development and changes, the stereotype remains the same and the connection between the signified and the signifier has not been severed.”

161: “Transformation in the Journey to the West tradition is appreciated as an ability to shift freely between various forms, whereas in many other mythical traditions it can also mean a one-dimensional switch from one form to another, or the loss of the original form. Besides Sun Wukong, many other beings in Journey to the West are able to transform freely, without being locked into one form and losing avenues to others. In contrast, some transformation stories in Greek and Latin traditions focus on metamorphoses of a rigid kind, wherein a being after transformation is permanently locked in the adopted form, unable to return to the original. This form of transformation is seen as a loss, or a suffering.”

162: “When relating colonial discourse to fetishism, Bhabha describes the stereotype as ‘a form of splitting and multiple belief,’ and because it contains these contradictory elements, it requires being continually repeated and also ‘a continual and repetitive chain of other stereotypes’ for its significance to be successful.”

164: “Multivalence, then, is a crucial quality for maintaining transformability. A transformation with integrity is the one that remains fluid, in which an identity may transform itself back and forth freely. Instead of making a choice among different forms, it contains all. The multivalent and dynamic transformation is an answer to the split and contradiction of the stereotype.”

166: “The trickster image of the Monkey King is self-deconstructive, disallowing its own image to solidify, which results in fundamental multivalence and the capability for positive transformation.”

167: “The Monkey King image suggests that ‘identity’ does not have to negate plurality; it offers an option of enriching the meaning of ‘identity’ as an alternative to giving up on the concept or using concepts such as ‘unification’ instead.”

169: “Like all trickster characters and despite the best efforts of researchers like myself to analyze him, the Monkey King remains a footloose figure, and one who will leave his mark on cultural texts that reflect the ever-changing and flowing multiplicity of global cultural currents. Moreover, he serves as a mask for the performance of diverse politics, bodies, and identities, yet simultaneously remains a character that is distinctly and indelibly Chinese.”

-“The aim of this book has been to provide a renewed understanding of the Monkey King character as a trickster, as well as to demonstrate the link between the Monkey King character and the Chinese self-conception of national identity.”

170: “Other narratives of transformation—such as that of the butterfly lovers, Lady White Snake, Mulan, Avalokitesvara, and Guan Gong—reveal their own patterns as they travel across time and culture.”

-“The original plan for this work included a cross-cultural comparative study of the Monkey King from China and Hanuman from India. Although both originated as monkey figures in the traditional legends and beliefs, Sun Wukong turned into a trickster figure, whereas Hanuman remained a hero with serious and upright values. The difference between the two monkeys is especially interesting when the possible genealogical connection between them is considered as a transcultural experience of one monkey and its rewriting.”

-“Journey to the West has become ‘part of the rich background texture of Chinese thought, speech, and behavior; it is to the present day an inexhaustible archive for role modeling, argumentative wit, and political innuendo.’ Beyond that, it is also worth our attention that the ‘Journey to the West’ has increasingly become a trope for East-West relations.”

172: “In the retelling and rewriting history of the Monkey King, performance brings history and the mythical/fictional together. The historical journey of the monk Xuanzang is brought into the fictional realm through oral performances. Although how the Monkey King has joined the journey is never clearly explained, it is agreed that it is the result of the Indian and/or Chinese religious or legendary figure(s) joining the ‘Journey to the West’ narrative via performances.”

173: “The Monkey King is thus found in real life and written in history, such as in the records of the Boxer Rebellion. One can also argue that the popularity of the Monkey King in real life and the popularity of ‘Journey to the West’ have promoted each other. In our recent examples, when Sun Wukong is linked to real historical figures such as Mao Zedong and to national or social groups such as the Chinese or Asian Americans, the connection between history and myth is made evident. It is through this connection that this project of the Monkey King becomes a vehicle, its moving window enabling us to observe the history of various periods.”