#Silvia Mazzucchelli

Text

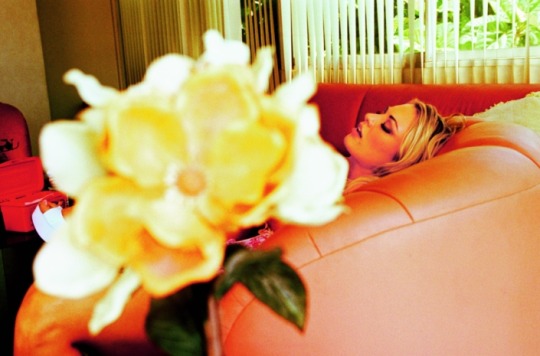

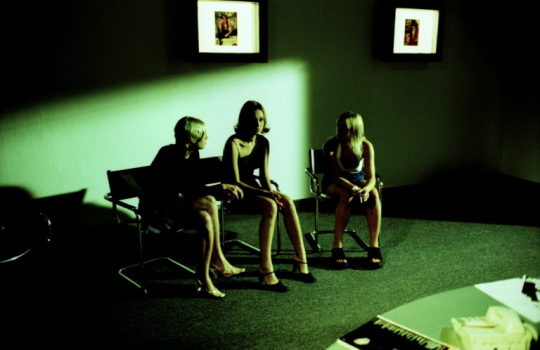

STEFANO DE LUIGI – PORNOLAND REDUX

Pornoland Redux è il racconto di un ritorno da una terra dove si svolgono battaglie campali e hanno luogo epiche imprese, un luogo di cui tutti parlano e che tutti vorrebbero visitare. I confini di Pornolandia sono larghi e labili: Berlino, Budapest, Praga, Tokyo, Los Angeles, Milano, ma la scena geografica non è resa da “fatti”, è essenzialmente rappresentazione di fantasie oniriche, allucinazioni ad occhi aperti, dettagli, ossessioni più reali della realtà stessa.

Stefano De Luigi, in punta di piedi, quasi un’ombra sul set cinematografico, riscrive le dinamiche di un immaginario ormai cristallizzato in una lunga ma definita serie di situazioni, contrapponendo la banalità del quotidiano al climax del momento erotico.

Le fotografie non descrivono e nemmeno raccontano, ma eludono, o più spesso alludono. Non vi sono corpi levigati che si muovono fra paradisi edenici o lussuose residenze californiane colme di specchi e piscine dalle acque blu. Non compare alcuna delle delizie di Bosch. Ciò che le immagini racchiudono e significano è volutamente rimandato a un dopo, quasi come se la funzione di queste foto fosse quella di proteggere nello spazio i corpi degli attori, e rimandare nel tempo le loro azioni.

Lo sguardo del fotografo si sofferma spesso su ciò che non appare, che non ci si aspetta di vedere.

Dal testo di Silvia Mazzucchelli che accompagna le fotografie.

© Stefano De Luigi 2004, edizioni Self 2021, con l’aggiunta di alcune foto inedite, del libro pubblicato da Contrasto nel 2004. Testo (c) Silvia Mazzucchelli 2004.

#stefano de luigi#pornoland redux#photography#photobook#photo project#silvia mazzucchelli#contrasto#2004#self#2021#ristampa#reissue

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Milano: Nuove cinque opere in città in occasione di Artweek 2023

Milano: Nuove cinque opere in città in occasione di Artweek 2023.

In occasione di ArtWeek 2023, la settimana dedicata all’arte moderna e contemporanea, Milano si arricchisce di cinque nuovi lavori di artisti contemporanei per lo spazio pubblico: Franco Mazzucchelli in Darsena e Triennale Milano, Flavio Favelli nel cortile del Mudec, Otobong Nkanga, Liliana Moro e Rossella Biscotti si aggiungono al percorso di Artline.

Dall’11 aprile, nel cortile del Mudec (via Tortona 56) si potrà ammirare un nuovo dipinto murale di Flavio Favelli, dal titolo “I Trenta”, un progetto a cura di Alice Cosmai e Alessandro Oldani realizzato con il supporto tecnico di Walter Contipelli – Orticanoodles e la collaborazione di BASE. L’opera si inserisce nella programmazione di arte urbana legata alla mostra “Rainbow. Colori e meraviglie tra miti, arti e scienza", visitabile al Mudec fino al 2 luglio 2023.

Il murale riproduce, tramite un segno pittorico molto essenziale, trenta passaporti di diversi paesi del mondo tratteggiati con un gradiente cromatico che ricorda l’iridescenza dell’arcobaleno.

Favelli si sofferma da tanti anni su francobolli, banconote, bandiere e documenti, in pratica il linguaggio visivo del potere, uno dei più interessanti – a volte tanto complesso quanto banale – sul quale ha prodotto molte opere fra assemblaggi, composizioni, collage, pitture e appunto murali. Nonostante siano oggetti comuni e importanti, i passaporti, proprio come le banconote, sono molto visti ma poco guardati e conosciuti. Il progetto consiste nel dipingere i soggetti delle copertine di vari passaporti, quelli per lui sono più interessanti, fra il desueto e il problematico, fra il lontano e l’esotico, fra il misterioso e il reietto, fra l’ambiguo e il complicato.

Il murale sarà inaugurato con una conversazione tra l’artista e il collettivo Claire Fontaine sul tema “Dentro/fuori. Dialoghi di arte pubblica” moderato da Silvia Bignami (11 Aprile, dalle 18.00).

Franco Mazzucchelli torna a Milano, la sua città, con "Aria, terra, acqua", un doppio intervento in cui le sue sculture di aria sono allestite su terra, nel Giardino Giancarlo De Carlo in Triennale Milano dal 13 al 26 aprile e sull’acqua, ovvero sulla Darsena dei Navigli dove dal 14 aprile sarà visibile la spettacolare opera “Elica”.

In Triennale, nel cui salone l’artista aveva realizzato la prima delle sue “Sostituzioni” (1973) Mazzucchelli interviene con una installazione dal titolo “Aperta parentesi”. Due grandi archi fissati al terreno alludono a una parentesi tonda, una pausa spaziale che delimita una selezione degli iconici gonfiabili di Mazzucchelli, esposti a rotazione per tutta la durata della mostra. I gonfiabili, elementi geometrici leggeri tipici del linguaggio di Mazzucchelli potranno infatti essere liberamente movimentati nel giardino uscendo dagli spazi dati come segni non monumentali, mutevoli e sorprendenti. L’architettura delle opere e la configurazione del giardino di Triennale cambia così volto durante la mostra grazie al pubblico chiamato a mescolare le carte e a invertire le formule date.

La seconda tappa della mostra e pezzo centrale dell'operazione verrà svelata venerdì 14 aprile: si tratta di “Elica”, un grande gonfiabile appositamente realizzato da Mazzucchelli e che ricorda una sua azione storica, ”Abbandono” del 1969, quando una scultura dalla simile forma a più curvature fu lasciata in libertà sulla spiaggia di Saintes Maries-de-la-Mer, in Camargue. “Elica” galleggerà sullo specchio d’acqua della Darsena dei Navigli, nel tratto verso piazza XXIV Maggio.

Tre nuove opere si aggiungono al percorso di ArtLine Milano: “Come fare?” di Rossella Biscotti; “Sundown” di Liliana Moro e "Where Strata Gather” di Otobong Nkanga. ArtLine è una collezione di opere di arte pubblica del Comune di Milano, che si completerà entro il 2023 con diciannove interventi permanenti di artisti internazionali nel parco di CityLife.

L’opera “Where Strata Gather” di Otobong Nkanga (1974, Kano, Nigeria; vive e lavora ad Anversa, Belgio), consiste di cinque sculture, realizzate con elementi naturali come pietra, marmo, argilla collegate tra loro da tubi in acciaio. L'opera fa riferimento agli strati invisibili e nascosti del sottosuolo, tramite materiali che caratterizzano la composizione geologica del territorio lombardo. Le sculture ci invitano a riflettere sulla relazione tra il materiale grezzo e le possibili trasformazioni a cui questi elementi possono dar vita.

L’istallazione “Sundown” di Liliana Moro (1961, Milano) è composta da trenta sedie in bronzo, da un elemento scultoreo in metallo di colore giallo simile a una tenda e da un diffusore acustico che trasmette in tempo reale i programmi di Radio Rai 3. Al momento del tramonto, un segnale acustico, che si sovrappone alla radio abbassandone il volume, ci avverte che stiamo per assistere al giornaliero spettacolo naturale del passaggio dal giorno alla notte. L’ora del tramonto diventa dunque un dispositivo per condividere una trasformazione quotidiana e l’opera è il luogo in cui è possibile incontrarsi e fare questa esperienza.

“Come fare?” di Rossella Biscotti (1978, Molfetta, vive e lavora a Bruxelles, Belgio) è strutturata in cinque ‘isole’, realizzate con mattoni e cemento e messe in relazione tra loro. Una installazione che attraverso l’utilizzo di strutture modulari ispirate alla storia recente della sperimentazione architettonica, della pedagogia e del design radicale, ricompone un agglomerato urbano in miniatura che il visitatore può attraversare innescando un percorso esperienziale e percettivo. Inoltre l’opera di Serena Vestrucci, “Vedovelle e Draghi Verdi”, del 2017, che consiste nel redesign delle bocchette di alcune fontanelle dell’acqua pubblica, viene arricchita di un nuovo elemento.

Durante la settimana di Art Week, nel Parco delle Sculture ArtLine di CityLife si terranno alcune visite guidate con Roberto Pinto e Katia Anguelova. La prenotazione è obbligatoria tramite mail a: [email protected] - Appuntamento alle ore 18 del 14, 15, 16 aprile davanti alla fermata Tre Torri della Metropolitana 5.

...

#notizie #news #breakingnews #cronaca #politica #eventi #sport #moda

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

"Forse il ritratto ha il potere di anticipare, intuire, svelare un futuro prossimo a venire. Il segreto, come nella Lettera rubata di Edgar Allan Poe, è proprio davanti agli occhi di chi osserva. Di sicuro ha l’ambizione di un documento capace di narrare ai posteri una vicenda vissuta fino al momento dello scatto, è sintesi di un passato che si propone al futuro, è un attimo pieno di storia che aspetta domande e che generosamente fornisce, o illude di fornire, risposte".

Il ritratto fotografico. Corpi, maschere e selfie | Silvia Mazzucchelli

1 note

·

View note

Text

[Oltre lo specchio][Silvia Mazzucchelli]

Oltre lo specchio di Silvia Mazzucchelli introduce ai lettori italiani la figura di Claude Cahun e la sua tensione allo scardinamento dei riferimenti culturali e sociali.

Claude Cahun (1894-1954) è un’artista, fotografa e scrittrice vissuta nella Francia della prima metà del Novecento, in pieno fervore surrealista. Al centro della sua ricerca artistica e letteraria vi sono i temi dell’identità, del superamento dei confini di genere e delle proprie origini ebraiche in un contesto sociale fortemente antisemita. Nei suoi scatti radicali ed enigmatici ritrae se stessa…

View On WordPress

#2022#Claude Cahun#Italia#Johan & Levi#LGBT#LGBTQ#Marcel Moore#nonfiction#Oltre lo specchio#Oltre lo specchio Claude Cahun e la pulsione fotografica#Saggi#Saggistica#Silvia Mazzucchelli#Suzanne Malherbe

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Vedere e esserci: due libri sulla fotografia

Vedere e esserci: due libri sulla fotografia

di Silvia Mazzucchelli, doppiozero.com, 22 gennaio 2019

Una mano tiene fra due dita una fotografia. Si vede un albero molto grande, un prato su cui ognuno vorrebbe sdraiarsi e nuvole bianche nel cielo. La foto si sovrappone alla realtà. Il soggetto sta osservando l’immagine nel luogo dove l’ha scattata, anche se la realtà appare sfocata: le nuvole, il cielo e l’albero sono semplici macchie di…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

More than a year after American Apparel went bankrupt and shut down all 110 of its stores — a fleet that had bloomed to 281 locations during its heyday in the late aughts — the company is preparing to open a new shop. Just one, on Melrose in Los Angeles, the city where American Apparel made its name.

The neighborhood where the new store will live is “good for emerging brands,” says Silvia Mazzucchelli, American Apparel’s vice president of direct-to-consumer sales. But an “emerging brand” isn’t what most would consider American Apparel.

After going bankrupt twice, the company was bought by Canadian retailer Gildan Activewear in early 2017. When Gildan relaunched American Apparel later that year, its name was the same, but key aspects of its identity were missing; its guts were different.

American Apparel’s journey is a prime example of what can happen when a failing brand is sold for parts and restarted by new owners. Its collapse just predated a tidal wave of retail bankruptcies and store closings that began in early 2017, hitting chains like Macy’s, The Limited, and Payless. Some brands never came back up (Toys ‘R’ Us), and some (Nasty Gal) were purchased out of bankruptcy like American Apparel.

American Apparel is a good case study for this phenomenon; the brand has changed under Gildan in very clear ways. On a surface level, it looks similar to what it was before: The brand still sells its most iconic styles, and its Instagram still features the high-flash photography for which the brand was known (though its newest photos lean more toward soft, natural light). But two of American Apparel’s most defining qualities have been altered.

Its tone, once cheeky and fairly smutty, has been transformed into a message of empowerment — the idea is that shoppers can still look sexy in a bodysuit or colorful, skintight pants, but on their own terms. And American Apparel, once a champion of domestic manufacturing, is no longer wholly made in America.

A model wears American Apparel’s fall 2018 collection. American Apparel

A model wears American Apparel’s fall 2018 collection. American Apparel

To explain why American Apparel has changed in these ways, it’s important first to understand its business, which is bifurcated into a collection of fashionable basics sold directly to shoppers and a range of “blanks,” styles like T-shirts and hoodies that are sold to screen printers. The latter is the core of Gildan’s $2 billion-plus business, too, and though it considered shutting down American Apparel’s direct-to-consumer wing, it kept it open because it gives the wholesale operation some extra shine.

“They were not going to bring back the consumer space. They were just going to keep printwear,” says Sabina Weber, American Apparel’s vice president of marketing. “But [Gildan] soon realized that without the brand, you have just a T-shirt. Everybody sells a T-shirt.”

Having a strong brand means you can sell a blank T-shirt as a premium product. That’s assuming, of course, that American Apparel hasn’t lost its touch with shoppers.

The company’s story starts with blanks. Dov Charney, a Canadian, founded American Apparel as a wholesale T-shirt business in 1989, but it wasn’t until the brand started growing its direct-to-consumer business in the hipster days of the early ’00s that it became a full-fledged cultural phenomenon. American Apparel was known for colorful wardrobe basics, a strict practice of manufacturing in the United States, and ultra-sexualized advertising imagery.

Under Charney’s direction, its sales rose from $80 million in 2003 to $250 million in 2005 and $634 million in 2013, though by that point it hadn’t turned a profit in years, the LA Times reported.

High energy and outspoken, Charney was an unconventional CEO in every way. For a long time, he managed to hang onto his business despite a reputation for inappropriate behavior. That reputation was magnified by a 2004 article in Jane magazine saying that he masturbated in front of reporter Claudine Ko, and it resulted in a string of sexual harassment lawsuits.

The exterior of an American Apparel store in West Hollywood in 2010. Mark Ralston/Getty Images

American Apparel’s series of rebirths began in 2014, when Charney was removed from his role as CEO after an investigation found that he had mismanaged funds and knowingly allowed an employee to post nude photos of a female staffer on the internet.

Charney stayed on as a consultant to American Apparel after his firing, and waged a legal battle for control of the company. In December 2014 he was fully terminated and replaced by Paula Schneider, a former executive at BCBG Max Azria.

So began one attempt to make over a company with a tarnished reputation and slumping sales. But in October 2015, American Apparel filed for bankruptcy, weighed down by debt, and a year later, Schneider too was heading out the door. (She is now CEO of the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation.) In November 2016, the company filed for a second bankruptcy. That year, Charney founded another basics brand called Los Angeles Apparel.

The latest and current phase of American Apparel’s life began in January 2017, when Gildan Activewear acquired the brand’s intellectual property out of bankruptcy proceedings for $88 million. That purchase also included “certain manufacturing equipment,” but the real value was in American Apparel’s name.

One of the many American Apparel stores that closed, this one in 2016. Victoria Jones/Getty Images

After the acquisition, all of American Apparel’s stores shut down, but the brand wasn’t dead. It relaunched its website in August 2017, and though it looked very much like the old American Apparel, it was Gildan under the hood. The company’s first order of business was offering e-commerce customers the option to choose between products made in the US and cheaper, identical pieces manufactured abroad — a radical shift from American Apparel’s original manufacturing ethos.

When Boohoo acquired and rebooted the bankrupt Nasty Gal, it, too, looked fairly similar on an aesthetic level. But one thing made it abundantly clear that the brand had changed hands: Numerous people who had purchased items during the ownership transition found that their credit cards had been charged but no order had been shipped, and they went off on Nasty Gal on social media.

The company’s response, via Twitter: “The new owners are not liable for refunds. We do advise you contact your bank and request a chargeback.”

Today, American Apparel’s design, marketing, merchandising, sourcing, and production teams work out of a building in an industrial section of LA, not far from the company’s former factory and headquarters. The open-plan office on the upper floor is scattered with relics pulled from the brand’s old home: a sign capped by a silhouette of a woman’s legs, and neon lights arranged into the form of three women in various gymnastic poses.

Downstairs is a photo studio where, in mid-July, the house photographer was reshooting e-commerce photos. The models had looked too stiff in the first set of pictures, and since American Apparel has no stores right now, the team decided they needed to do them over to show more movement and angles. American Apparel has made no commitments yet to establish stores beyond the Melrose location, which opens in December, but even one storefront will give the company a much-needed chance to woo customers in real life.

Mazzucchelli envisions the Melrose space as having the same design DNA as American Apparel’s now-shuttered stores — it will likely use some kind of grid wall display system, a hallmark of the old brand — and she stresses the importance of it looking uncluttered. Negative space signals confidence; every minimally-stocked luxury store knows that.

Standing at the island in the American Apparel kitchen, Weber laid out images for a campaign for nude bodysuits that launched in early September. The pictures showed a diverse bunch of women wearing leotards in nine different shades of nude — eight more than American Apparel used to offer, Weber says. Following in the footsteps of brands that make lingerie for shoppers of all skin tones, American Apparel is trying to be more inclusive.

It’s also attempting to disassociate itself from what Claudine Ko called “kiddie-porn-like ads.” Weber says that when American Apparel puts out open casting calls, it’s looking for models over 21.

“I mean, we’ll still feature models that are 19 or 20. It’s not a hardcore rule,” she says. “But in general the brand previously showed girls that were quite young, and there was an uncomfortable component to that, and there’s no need for it.”

A model in American Apparel’s “Nudes” campaign from September 2018. American Apparel

Weber joined the brand more than two years ago, right before it headed into bankruptcy, and managed the messaging around the store shutdowns while looking for other work. She was hesitant when Gildan asked her to stay on through the acquisition, but, she says, she loved American Apparel.

“When I had the chance to bring it back, I was like, ‘Fuck it, I’m going to do it,’” Weber says.

Her vision for the new American Apparel is a tricky thing to pull off. It’s not over-sexualized, but it’s still sexy. It’s about empowerment and women owning their sexuality. It’s not about shooting models from angles that look overtly predatory. Throughout the summer, American Apparel still used the lo-fi, direct flash photography style that’s synonymous with the brand’s earlier, more controversial days.

“It’s very uncanny valley,” says Julie Robinson, a 29-year-old freelance fashion designer and former American Apparel obsessive (she hasn’t bought anything since the relaunch). “It’s the same, but it does feel a little different.”

For its fall collection, however, American Apparel shot models in outdoors, against the backdrop of concrete buildings and misty lakeside docks. It’s a simple change, but one that signals a broader transition in the brand’s identity.

There is a lot of carryover from American Apparel’s old product lineup, because despite the company’s various scandals, people have strong attachments to their “Easy” jeans and zip-up hoodies. For the first year of its life under Gildan’s management, American Apparel focused on putting out its classics, which is just as well because the few new pieces it introduced, like a crinkly nylon jacket, didn’t sell at the same level.

Weber chalks that up to customers not being able to see and touch those products in stores. (She really can’t wait for American Apparel’s first location to open later this year.) Still, the fall collection brings a lot of what those in the retail business call “newness,” like a twill jumpsuit, a trendier bell-sleeve fisherman sweater, and a mixed modal turtleneck that the team told me would be the softest thing I’d ever touched. It was very, very soft.

Then there’s the decision to no longer manufacture entirely in America. That was “the most difficult of transitions, or the one we thought about the most,” says Mazzucchelli.

American Apparel’s test of shoppers’ desire for goods made in the US — giving them the option to buy a $22 tee made in America or a $18 “globally made” tee — resulted in the finding that most people would rather buy the cheaper option.

“We came to the conclusion that the ‘American’ in American Apparel is not necessarily a place,” says Mazzucchelli, who joined the company in January 2016. “Customers care that we are ethically made and sweatshop-free. They don’t really care if we are ethically made in China, in Mexico, in Honduras, in the US, or in France.”

A Guardian report from November 2017 paints a very different picture of how workers are treated in Gildan’s factories, citing complaints dating to 2004. Those included “mandatory work shifts longer than the legal maximum limit, illegal dismissals of employees involved in unions – including the dismissal of a pregnant woman, as well as consistent harassment and verbal abuse targeted at employees.”

American Apparel does still make some of its clothing in the US. Sometimes the best factory for a product category is located domestically; Vivi Tran Lynch, American Apparel’s former sourcing director, said in July that the brand uses a swim vendor in LA because it delivers the right combination of quality and price. (Lynch has since left the company for the clothing brand Self Esteem.)

But it’s also because screen printers like to be able to offer their customers — sports teams, fire departments, bands — a made-in-America option. If not for the everyday shoppers, American Apparel has to do it for its wholesale customers.

That’s the thing about brands that go under and return, zombie-like, in an altered state. Companies are mutating all the time, shutting down departments that aren’t financially viable and discontinuing products that don’t sell. But when a brand is bought out of bankruptcy, though, it becomes eminently clear what portions of its business still have value, because that’s all that’s allowed to live on.

Want more stories from The Goods by Vox? Sign up for our newsletter here.

Original Source -> American Apparel’s rebrand says a lot about life after bankruptcy

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

New Post has been published on Vintage Designer Handbags Online | Vintage Preowned Chanel Luxury Designer Brands Bags & Accessories

New Post has been published on http://vintagedesignerhandbagsonline.com/american-apparel-returns-with-a-focus-on-empowerment-and-diversity-business/

American Apparel returns – with a focus on empowerment and diversity | Business

American Apparel is back. The brand that spawned myriad copies of its hooded tops with contrasting pull cords in the 00s before exiting the high street after much fanfare and a high-profile bankruptcy in 2016, became available again online in the UK this week.

The US retailer has weathered a well publicised storm over the past three years, which included the departure of founder and CEO, Dov Charney, and mass redundancies, followed by large-scale protests by its former workers. Now, after a reboot by its new owners, Gildan Activewear Inc, the Canadian-American manufacturers that bought the company for $88m (£62.5m) in 2017, the company is aiming to reclaim its title as the go-to retailer for the best basics, says brand marketing director Sabina Weber.

“We didn’t take the approach of saying, ‘this is a new brand’, we took the approach of: ‘this is a brand that is deeply loved and made some mistakes and there are lessons to be learned’.”

The new team has brought back a lot of American Apparel’s signature products, including the same branding, street-cast campaigns and items such as bodysuits, disco pants and athleisure jersey basics. The highly sexualised image it cultivated in the latter Charney years, however, is not the epoch Weber and her team wants to resurrect.

“We went back through the archive and it’s very clear where the ads and images were working, and where they just become completely unacceptable. Especially as a woman, I look at those images and I cringe.”

It wants to revert to its early image of a cool and inclusive label. “What the brand stood for prior to it becoming overly sexualised and uncomfortable was actually at the forefront of what’s happening now,” says Weber. “Using real girls, showing diversity, fighting for immigration and standing for LGBTQs was being done by American Apparel long before anyone else figured out that there was a commercial value there.”

Its first campaign under Gildan still shows American Apparel as a “sexy brand”, says Weber, but an engaging and fun one too, featuring people of all groups and backgrounds. “It was challenging to come back as a sexy brand and say, ‘we’re staying sexy’, because there’s nothing wrong with being sexy – it’s just how you do sexy. It [now] comes from an empowered perspective and you’ll see that in our images and the stories that we tell about people we use. It doesn’t just apply to our women, it applies to our guys too.”

One big change is the Made in the USA tag. Its commitment to producing all of its collections in downtown LA factories – Charney refused to outsource from the US – defined its former incarnation. Now, the brand splits manufacturing between its own factories in Central America and Gilden-approved vendors governed by its Genuine Responsibility programme around the world, including Mexico and China.

“Our customer has never really cared about the ‘American’ in American Apparel because it was made in America. They’ve always cared about American Apparel because it stands for certain values of authenticity, diversity and ethical manufacturing and we keep all of those values now, even though we are not necessarily made in the US,” says Silvia Mazzucchelli, vice-president, direct to consumer.

American Apparel campaign. Photograph: American Apparel

On its website, its Made in USA Shop allows customers to choose between the “designed and sewn in the USA” version of eight popular styles and its “globally made twin”. The signage says, “Both are sweatshop free, identical in quality, different in price. We are… ethically made regardless of the location. You decide.” Its signature Flex Fleece Zip Hoodie is £44 and £34 respectively.

“The goal of this page was to be transparent about where our product was made and to give the customer a choice,” says Mazzucchelli.

The company is championing a digital-first approach. At one point, it had 260 shops in 19 countries around the world, including the UK. Now, it has an online-only presence, with its first new shop slated to open in LA at the end of 2018.

“Obviously there is plenty of competition out there,” adds Mazzucchelli, “but the unique thing about American Apparel is that it has always stood for timeless fashion basics.”

Source link

0 notes

Text

Gli Strumentisti

Le persone che con il loro entusiasmo e la loro dedizione sono linfa vitale di questa associazione.

Flauto traverso:

Martino Alberti, Silvia Guzza, Mattia Mignemi, Giovanna Povinelli, Giulia Salvetti

Oboe:

Beatrice Moraschetti, Noemi Moraschetti

Clarinetto piccolo Eb:

Arianna Bernardi

Clarinetto:

Lucia Bernardi, Michela Bernardi, Cinzia Bosio, Gian Franco Cominassi, Alessandra Gelmi, Lorenzo Mascherpa, Barbara Molinari, Francesca Nodari, Irene Pedretti, Ezio Perico

Clarinetto Basso:

Sergio Mascherpa

Sax Contralto:

Mattia Maffeis, Marco Mora, Davide Parolari

Sax Tenore:

Luca Bernardi, Diego Cominassi

Sax Baritono:

Ermes Bernardi

Tromba:

Giulio Alberti, Gian Antonio Bernardi, Matteo Bernardi, Walter Bosio, Mauro Giorgi, Dylan Gozzi, Nicola Nodari, Matteo Rivadossi

Trombone:

Natale Magarelli

Flicorno Baritono:

Cesare Bonomi, Antonio Mascherpa

Corno in Fa:

Luca Gazzoli

Basso Tuba:

Luigi Bernardi, Paolo Mazzucchelli

Percussioni:

Fabio Alberti, Martino Bernardi, Simone Bernardi, Gian Pietro Bosio, Battista Mora, Patrizio Piapi

Glockenspiel:

Silvia Matti

Alfiere:

Gigi Magnini

0 notes